Women of Spirit, Courage and Action

A collection of stories that celebrate women across generations who have worked for justice and acted for peace

Written and collected by the Loretto Feminist Network

A collection of stories that celebrate women across generations who have worked for justice and acted for peace

Written and collected by the Loretto Feminist Network

Just as frontier living shaped the lives of our early sisters, so a global society shapes ours. The need to broaden our vision and adjust our lifestyle and mission to a new millennium calls us to responsible change.

I am the Way, Loretto Constitutions, p. 3

Copyright ©2023 by Loretto Feminist NetworkAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below.

Loretto Community 515 Nerinx Rd. Nerinx, Kentucky 40049 www.lorettocommunity.org

Women of Spirit, Courage and Action—page 2

The Loretto Feminist Network is a voluntary association of feminists in the larger Loretto Community. The Community is composed of Sisters of Loretto and Loretto co-members. We are committed to act for the empowerment of women and all people. We agree to work toward transforming institutional, personal and structural relationships based on domination and subordination, both within the Loretto Community and beyond it.

The Loretto Feminist Network stands in solidarity with others working for the empowerment of all people both nationally and internationally. We act within Loretto and in the public forum. At times we work singly; at other times we work in small groups or geographic clusters. We also act as a network and in coalition with others. The intent of this collection of stories is to prompt interest, dialogue, learning and commitment among those who are the future of change and all of us who want to leave a legacy of working for justice. See lorettocommunity.org for more information on the Loretto Feminist Network

This booklet is a collection of profiles and stories of members of the Loretto Community, along with stories of women across the world who have made a difference by promoting change, working for justice and acting for peace. We hope that those of you reading these stories and responding to the questions and activities presented will be inspired to continue this work in the spirit of Loretto and in the context of the 21st century and all its challenges.

One of the earlier definitions of feminism, by bell hooks, is a “movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression” (hooks, 2000). Feminism works for the political, social, racial and economic equality for all women and all persons oppressed by societal structures. Political equity for women means having equitable laws and policies, holding political office and having rights, benefits and access to the political power that men have. Social equity means that women have rights in their families and communities. Racial equity means that people of color have all the respect, access and personhood as those who have white privilege. Economic equity means women have rights in jobs and the economy, like equal pay.

The definitions of feminism have evolved from the earliest years. More recently, Angela Davis defined feminism this way:

The definitions of feminism have evolved over time. In 2023 feminism is defined as more than gender equality. Feminism recognizes the intersectionality of people’s lives and includes a consciousness of how capitalism, racism and colonialism all have an impact on the experience of women and men in the world today.”

• What did you hear growing up about women and their role in society?

• What do you think of when you hear the word feminism?

• What do you know about the history of feminism?

• Who in your life is a feminist?

Stories are an important part of learning. They help us see how a life can be meaningful. They help us gain clarity on who we are and what is important to us. This book is a collection of stories you can explore. Notice justice in action!

Before you start exploring the stories in this book, think about your own story to this point in your life.

• What did you learn as a young child, 2 to 8 years old, that is important to you today?

• If your parents or caretakers were to describe you, what would they say?

• Tell about a time when you stood up for your beliefs.

The work for nonviolence has been the work of women throughout history. Nonviolence is a way of being, a philosophy and a response to acts of violence in the world. People who affirm nonviolence as a way of life choose nonviolent or peaceful actions to bring about change. Famous examples are Mahatma Gandhi of India and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. of the United States. Nelson Mandela is also an example of living nonviolence, both while imprisoned and when he became the leader of South Africa. Notice that when thinking of past examples, many immediately remember these men, yet a study of history would also note the women who were part of the movement. An early female suffragist, Alice Paul, exemplified a philosophy of nonviolence. Dorothy Day, the wellknown cofounder of the Catholic Worker movement, had a strong commitment to nonviolence. More recent examples are Mairead Maguire and Elizabeth Williams, activists in Northern Ireland who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1976 and cofounded the Community of Peace People.

Living nonviolence is a way of life, a call to the daily work of peacemaking, and it is a commitment of the Loretto Community.

at McCormick was born in 1935, and there were 11 children in the family, the first four each just a year apart. When asked about how she developed her sense of justice, she tells a story of when she and her one-year older sister were about six and seven — they were like twins and very close. Pat’s great uncle and aunt helped the family, as having four children so close in age was a lot of work. Her uncle favored Pat, and at Christmas, her sister got a doll, but Pat got twin dolls. Pat immediately felt that was not fair — she developed a sense of fairness from a young age.

Pat became a Sister of Loretto in 1964 and initially spent time in Bolivia, where several Loretto sisters went to establish and train teachers in Loretto’s elementary and high school. This opened her eyes to a different worldview and an acknowledgment that U.S. policies often hurt the poor, especially in what were, at the time, developing countries.

Pat has worked tirelessly against war and violence of any kind. In the 1970s this work included anti-war efforts because of the United States fighting in Vietnam and other locations around the world. She and other members of the Denver/Boulder, Colorado community are well known for their prayer and resistance on the once federal property located west of Denver known as Rocky Flats, a nuclear weapons facility that is now closed. She and two Dominican sisters also witnessed at a missile site in Wyoming.

Pat was asked to share her thoughts on nonviolence for this book. She describes nonviolence in an elegant way. Here are her words:

Nonviolence is a call, an urge to be present to people, situations and conflicts in an alert, well-informed and listening state of mind and heart. It takes practice and persistence, and it involves learning to know oneself. It includes outer and inner work, applicable to all life choices. By its nature, it lends itself to a prayerful presence. In my experience, the learning takes place by varying opportunities:

• Assumptions are challenged.

• Convictions are clarified by group discussions.

• Unexpected confrontations give us pause.

• Imagination and humor become valued assets.

• Convictions are deepened.

• Character is strengthened.

“Commitment to nonviolence becomes, with practice, a way of life. Such a commitment is strengthened by how I respond to daily local, national and global events, noting how such events, news or decision-making affects people, the environment, children or a family in a war-torn country.

“Personally, my commitment is rooted in Jesus’ teachings that every person is loved unconditionally by God, has a right to live and that no human being is superior to another. A nonviolent position is aware of and acts upon human rights violations. We women, as nurturers, have the soulforce to be leaders in future decades of becoming a unified, global people.

“One’s intent to practice nonviolence recognizes that snubbing another, bullying, lies and indifference are seeds planted to produce hate. A Buddhist teaching is that seeds of hate and love are planted daily; the result depends on which seeds are watered. Now and in future U.S. generations, we face ‘the last grasp of whiteness’ as citizens demand and work for justice and systemic changes in education, housing rights, safety in the streets, cultural recognition and presence for all at the decision-making tables whereby all citizens are affected.

“Nonviolence is the opposite of passivity. It is not to be left to those who march, protest and get arrested. At the time of George Floyd’s murder, it was clear that past silence and indifference by U.S. citizens meant complicity in the murder. Immediately, the majority awoke, spoke out, acted and some demonstrated. As a nation, we did not want to be complicit in the murder of one more Black man, woman or child. I am one of 12 persons committed to nonviolence who, since early June 2020, have been standing in vigil weekly in downtown Denver, holding banners and signs supporting Black Lives Matter, being non-racist and nonviolent.

“We live in a segregated U.S. society of “we” and “they.” We are eons away from Mahatma Gandhi’s statement that “there are many things I am willing to die for but none that I am willing to kill for.” Modern U.S. warfare requires an Air Force officer in Nevada to launch a drone by computer to target an enemy site, which may kill innocent family members in the Middle East or elsewhere. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. taught that we face the choice of nonviolence or nonexistence with the persistent threat of nuclear and chemical warfare. Greta Thunberg personifies the cry to stop the violence we are waging on our beautiful planet. Now is the time to be awake and act nonviolently.”

Nonviolence is a call, an urge to be present to people, situations and conflicts in an alert, well-informed and listening state of mind and heart. It takes practice and persistence, and it involves learning to know oneself. It includes outer and inner work, applicable to all life choices.”

Pat McCormick SL

XGonzález was born on November 11, 1999 and grew up in Parkland, Florida. They* became well known after the school shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland on February 14, 2018. X was a senior in high school at the time and graduated that June. Their mother is an educator; she and X’s father immigrated from Cuba in 1968. In high school X was the president of the Gay-Straight Alliance. As of this writing X has graduated from college and continues the work for social justice issues, especially relating to gun violence. X asks young people to join the fight for reducing gun violence.

Three days after the shooting, on February 17, 2018, X gave an 11-minute speech that propelled them into the national spotlight. They emphatically stated, “We are going to be the last mass shooting.” X encouraged the community, and especially students, to act. School shootings were not new — as a country, we have been living through them publicly since the 2001 Columbine High School shooting in Colorado. While many parents of students at schools that have experienced shootings are anti-gun-violence advocates, what made X’s response unique was that X and other students were leading the effort. Their speech became emblematic of the “new strain of furious advocacy” that sprang up immediately after the shooting (Washington Post, Feb. 18, 2018).

In planning the speech, X called on the example of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. from the Black spiritual tradition: call and response. X wanted a four-syllable chant and decided on “We call B.S.” They didn’t want to say the actual curse words. On the national stage, X went on to speak out at the March for Our Lives on March 24, 2018. They spoke for six minutes, the length of time of the shooting at Parkland, and paid tribute to shooting victims by naming each one.

In the year following, X continued to make appearances, give interviews and speak out against gun violence. X is memorialized in the introduction of Madonna’s song “I Rise,” released in May 2019.

* X uses the pronouns they, them and theirs.

X has written about the importance of voting and how people sometimes say they aren’t going to vote because the system is corrupt. X encourages everyone to think about the many people who can’t vote — those, for example, who are undocumented or have been incarcerated — and reminds us to “remember all of the people who fought with everything they had just to get the right to vote” (Vogue Magazine, Oct. 19, 2020).

X has shared about an ongoing struggle with trauma reactions due to the shooting such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression. In January 2020, X was one of several former Parkland students calling for the removal of U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Colo) from committees after Green’s disparaging comments about Parkland survivors (A. Broga, Sun Sentinel Times, February 3, 2021). X encourages all young people to vote and to get involved.

X created a moment in history where a young person stood up in the face of tragedy and spoke out. Today X is a leader in the March for Our Lives movement and continues to work against gun violence. X is an inspiration, opening our eyes to the possibilities for youth activism and the future of American society.

Voting is powerful. A lot of people are saying things like, ‘I’m not voting because the whole system is corrupt/ broken’ — cool, but that helps no one. We have to think of everyone, about every single person affected by the system.”

X González

Pat and X represent the work for nonviolence across generations. The 20th century, during which many Loretto Community members grew up, including Pat, created a space to question war, weapons and how harm is created by sanctioned activities. The 21st century has created new challenges for our communities, and youth especially have experienced what was once unthinkable — shootings at schools. Together, the stories of Pat and X remind us that this work is ongoing and evolving, and that peace is needed in the world.

1. Research the history of nonviolence movements in the United States and prepare a presentation for your classmates or friends.

2. Read Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and find three quotes that inspire you to work for justice and act for peace.

3. Read the following article about X and her current thinking:

https://www.thecut.com/article/x-gonzalez-parkland-shooting-activist-essay.html

1. Watch X González’s March for Our Lives speech on YouTube. In groups of four, create human sculptures to depict the message X is giving.

2. Review the six opportunities for learning that Pat McCormick presents, and discuss in class how you might create these opportunities in your classrooms or at your school.

3. Explore information about the March for Our Lives organization and movement. Check out https://marchforourlives.com Think about whether you would join this organization. Why or why Not?

1. Go to the Loretto Community website and read articles about the Peace Committee: https://www.lorettocommunity.org/tag/loretto-peace-committee/. Now write about what you learned.

2. Check out the Corrymeela Community and Spirituality of Conflict websites and discuss them with a friend. https://www.corrymeela.org/about https://www.spiritualityofconflict.com

One of the ways that women throughout history have fought for change is through constitutional changes — first fighting for women’s right to vote and then for an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The first-wave feminists fought for the right of women to vote. As women in the early 20th century realized, without a say in the political process they would never be equal. By the middle of the 20th century, the second wave of feminism had taken hold and women wanted rights and privileges they felt they did not have access to, at home and in the workplace. This is when the idea of the ERA was conceived.

First proposed by the National Woman’s Party in 1923, the amendment was to provide for the legal equality of the sexes and prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex. The ERA was passed on March 22, 1972 by the U.S. Senate and sent to the states for ratification. Thirty-five states were needed to pass the amendment in order for it to be added to the U.S. Constitution. However, the amendment failed to pass in enough states to become law. Today the amendment, still not law, reads: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Here are the stories of two women who have fought for the Equal Rights Amendment over the span of years from 1972 to the present. The first is a Sister of Loretto, Maureen Fiedler SL, and the second is Jennifer Carroll Foy, an activist from Virginia.

aureen Fiedler was born in 1942, just after the United States entered World War II, at a time that we would consider the first wave of feminism. World War II created a shift in women’s roles as millions of women entered the workforce to make up for men who had gone to war. After the war, however, they found that not much had changed. Maureen tells the story of her feminist journey beginning at eight or nine years old.

I remember a moment of serious self-questioning one day. I watched my mother spend hours ironing clothes and curtains and just about anything in the house that could be ironed. I distinctly remember asking myself, ‘Is this the future?’ I was thinking of household roles, and I could not see myself doing these chores for a lifetime.”

Maureen Fiedler, Breaking through the Stained Glass Ceiling, 2010, p. xviii

By the time Maureen was a senior in high school, her sense of justice had progressed to action, and she carried out her first feminist act. The boys’ and the girls’ Catholic schools had merged just before Maureen became a senior, so there would be one graduation ceremony for male and female graduates. The priest/principal called Maureen into his office to explain that the custom of the student with the highest-grade point average delivering the valedictory address could not be followed that year. Maureen had achieved the highest grades, but since she was a girl, the next highest, a boy, would give the speech (https://www. lorettocommunity.org/maureen-fiedler-loretto-values-in-action).

The next morning, Maureen marched into the principal’s office and declared, “Father, this is unjust. It’s terribly wrong, and it will look simply dreadful on the front page of the city newspaper.” The school had its first female valedictorian that year!

Maureen joined the Sisters of Mercy in Erie, Pennsylvania in 1962. She formally transferred to the Sisters of Loretto in 1984.

The Loretto Feminist Network values of gender, racial, ethnic and sexual equality and peace and respect for Earth shine through Maureen’s life. In the early 1980s she traveled the country in her efforts to pass the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) for women. She worked to improve the conditions of those suffering injustice in Central America through her involvement in Loretto’s Latin America/Caribbean Committee. During the Ronald Reagan years and into the 1990s, she worked with the Quixote Center to end U.S. military involvement in Central America. She was a member of the Loretto Earth Network and is a committed environmentalist.

Maureen is nationally known for her role as the host and founder of “Interfaith Voices,” a public radio show that she began in 2001 and hosted until 2018. The program fosters interfaith dialogue on issues and incidents of the day. Maureen interviewed voices of faith traditions including Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, Jews and other world religions. Her program received numerous awards and hosted well-known guests, including former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

When Maureen was in her early 30s, she completed her Ph.D. at Georgetown University. Her doctoral dissertation asked why more women were not political leaders, even though the second-wave feminist movement was in full gear. She realized that cultural norms, traditional roles and discrimination were all factors, examples of male privilege and priority. And so, between the late 1970s and early 1980s she became an activist for the Equal Rights Amendment.

She founded and directed Catholics Act for ERA and in 1982 was one of eight women who fasted for 37 days for ERA ratification in Springfield, Illinois. She describes it as “a profound experience.” The ERA amendment did not pass in the required number of states, but Maureen continued her fight for women’s rights, particularly for the voices of women in the Catholic church, but also in all religious traditions as mirrored in her program “Interfaith Voices.”

As of the writing, Maureen is retired and living in Kentucky at the home of the Sisters of Loretto Community.

I remember a moment of serious self-questioning one day. I watched my mother spend hours ironing clothes and curtains and just about anything in the house that could be ironed. I distinctly remember asking myself, ‘Is this the future?’

I was thinking of household roles, and I could not see myself doing these chores for a lifetime.”

Maureen Fiedler SL

Jennifer Carroll Foy says, “My passion is passing legislation.” Jennifer was born in Petersburg, Virginia on September 25, 1981. She describes Petersburg as a town where young Black girls were not given hope that they could succeed. After graduation from high school, she showed up on the campus of Virginia Military Institute (VMI). Her grandmother supported her, saying that she could do anything she wanted. After the Supreme Court case that required VMI to open its doors to women in 1996, Jennifer applied and was accepted. She wrote, “My grandmother taught me, if you have it, you have to give it, and VMI was certainly an institution where I could sharpen my ability to be of service to others” (https://www. glamour.com/story/jennifer-carroll-foy-virginia-military-institute-protest).

After VMI Jennifer went to Virginia State University for a master’s degree and then on to law school at the Thomas Jefferson School of Law. As a lawyer she worked in California, and later returned to Virginia. In 2017 she was elected to the 2nd House of Delegates in Virginia. Jennifer wrote, “I’ve learned one big lesson during my time in the General Assembly: listen. Those closest to the pain need to be closest to the decision-making.” She resigned her position in the Virginia House in December 2020 to run for governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia in 2021 but lost the Democratic primary. She continues to teach, serve as a magistrate and take important stands for women’s rights.

As a third-wave feminist who is now living in the fourth wave of feminism, Jennifer understands the intersection of issues. For example, she understands how economic disparity erodes the security of women. She reminds us that Latinas face the greatest wage gap between women and men, earning 53 cents to every dollar a man makes. In comparison, women working full-time year round on average earn 84 cents to a white man’s dollar. In addition, she addresses school push-out of Black students, the high maternal mortality rate of Black women and the racial disparities in our criminal justice system.

I’ve learned one big lesson during my time in the General Assembly: listen. Those closest to the pain need to be closest to the decision-making.”

Jennifer Carroll Foy

The stories of Sister Maureen Fiedler and Jennifer Carroll Foy demonstrate a commitment to social justice and equality for women. They grew up in different eras — Maureen at the start of the push to pass the ERA, and Jennifer is active in today’s social justice efforts. Sister Maureen demonstrated and fasted … Jennifer fights for changes in legislation. They both believe change is possible.

1. Research the Equal Rights Amendment from its beginnings to today. Why do you believe it did not become law in 1972, and what do you see happening today? Are the barriers the same or different?

2. Write a five-minute speech on why we should or should not pass the ERA.

3. As you think about stories about fighting for women’s rights, what do these two women’s stories have in common, and what does that say to you?

1. In two paragraphs, write your reactions and reflections on the stories you read and what you learned from the class discussions.

2. Given our increased understanding of the gender binary, what might you change in the ERA wording?

3. For class discussion: Jennifer Carroll Foy’s grandmother told her, “If you have it, you have to give it.” What makes this motto powerful? What is the “it” that you must give?

1. Sign up to receive the Alice Paul Institute emails about the progress of the ERA.

2. Interview an elder who has experienced the history of the ERA and ask about that person’s perspective.

3. Join the ERA Coalition and participate in local activities.

4. Listen to an episode at interfaithradio.org and discuss with your family.

• Get a credit card in her own name. In 1974 credit card companies were finally forced by law to allow a woman to obtain credit cards without her husband’s signature.

• Be guaranteed she would not be fired if she were pregnant. That changed in 1978.

• Take action against workplace sexual harassment — this right was first recognized in legal action in 1977.

• While it varied by state, it was not until 1973 that women could serve on juries in all 50 states.

No concern is more significant in the 21st century than climate change — the destruction of our planet in ways that threaten its future. The concern for climate change is not new, but the urgency for action has never been more important. While all are impacted by climate change, women, especially in developing countries, are particularly vulnerable. In these countries, women are the ones gathering food, carrying water and finding fuel for cooking. Climate change has made all these tasks more difficult. Women make up 70 percent of the world’s poor (https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/genderand-climate-change).

The good news is that women are also leading efforts to address and change the many components of the climate change story. This section highlights two eco-justice feminists, Jessie Rathburn, a Loretto co-member, and Chris Schimmoeller, a Kentucky activist. As we think about women dedicated to issues of the natural world and environment, we are reminded of Rachel Carson; when she had an opportunity to speak to 1,000 women journalists about her writing, she said:

of

to destroy much of that beauty that has immense power to bring us a healing release from tension. Women have intuitive understanding of such things. They want for their children not only physical health but mental and spiritual health as well. I bring these things to your attention because I think your awareness of them will help, whether you are practicing journalists or teachers or librarians or housewives and mothers.” (Silent Spring, 1962)

“I believe it is important for women to realize that the world

today threatens

Jessie Rathburn, a Loretto co-member, grew up in Canyon Lake, Texas in a trailer on the edge of a trailer park in the Texas Hill Country. Jessie recently visited her childhood home and describes her experience:

A confederate flag flew in the front yard. Trash was strewn across the weeds, my mother’s garden was unrecognizable and the trees I learned to climb on were chopped down. Filled with sorrow, anger and disgust, I turned and drove the mile down the road to my grandparents’ old ranch. There, I marveled. The ancient trees remained standing, native grasses flourished in the fields and flowers bloomed along the front walk. Children ran around the lawn as I quickly took in the much-needed repairs that had been made since I had last seen the house.

Life presents us with so many contradictions. My humble beginnings were defined by love and acceptance, with long walks in the woods, blackberry-picking excursions and adventures in creek beds, turning over rocks in the shallow water to see what creatures we could discover.

I hardly noticed when my dad’s building business went bankrupt, and we survived on the generosity of family members. We were taught to love each other and Earth, to work hard and never to complain because we could always go outside and play, the supreme luxury of life. Now, a confederate flag shadows that yard.

In my early teen years, we left our trailer park and moved into a family house my dad and grandfather had built together in the 1970s. Here, I learned how to hang sheetrock, paint, install closets, lay flooring and more. We continued spending all of our free time outside as a family — hiking, camping, working in the yard and caring for our five acres of woodlands. I found small pockets of silence under shrubs and in rocky crags, where I would sit for hours, discovering the veins on a leaf, the hair on a grasshopper’s leg, the patterns of the swallows flying above. In these moments, I felt fully known, fully embraced, never alone.

Throughout high school and college, as I juggled academics, relationships, piano lessons, sports and my earliest jobs, I found myself returning to physical wildernesses in order to return to my inner self. The Gulf Coast, the Texas Hill Country, the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge and the Quetzal

Education Research Center in Costa Rica — each presented a vastly different landscape that nourished me, took me deeper into contemplation and opened my eyes to my place in the universe. These places on Earth became my center, where I would turn for guidance and comfort.

As I moved closer to Earth, I moved further away from my evangelical Christian upbringing, and several important women became central to a new spirituality I was discovering. In “Summer Day,” Mary Oliver first helped me name the limitations of what I understood and offered credibility to this deep connection I had with nature.

Mary Oliver first helped me name the limitations of what I understood and offered credibility to this deep connection I had with nature. She wrote about the small things in nature, like how to fall down in the grass; she asks the question, what will you do with your precious life?

I remember one day in particular. While taking GPS readings to help create a map of the San Gerardo de Dota Valley in the Talamanca Mountains in Costa Rica, I was distracted by a flock of quetzals. Jettisoning my equipment, I spent hours following the magnificent birds through the cloud forest, completely unaware of time, property boundaries and assignments. When I finally returned to campus and explained my lack of results, my professor’s response surprised me. “Why do you think you have to explain yourself? What else could you possibly have done? You’ve probably just had one of the most profound spiritual experiences of your life. Don’t forget it.”

Following college, my work centered around social justice and my heart centered on Earth. I worked with immigrant families in Texas, volunteered and taught English in a small village in Russia and finally moved to Denver, where I found a place to call home. In the mountains, I learned of ancient time, which now ran through me, connected by the rocks under my feet. I studied ornithology, quickly becoming obsessed with the hundreds of species passing overhead on their migratory routes. While volunteering with the Audubon Society, I found the writings of Terry Tempest Williams, another woman who added depth to my sense of spirituality. Alone in the mountains, unknown by humans for days on end, I prayed to the birds and found peace.

Over time, I found that I was in relationship with Earth. No longer was nature simply recreational. I found myself both a part of Earth and loving and being loved by Earth.

I remember one day in particular: While taking GPS readings to help create a map of the San Gerardo de Dota Valley ... in Costa Rica, I was distracted by a flock of quetzals. Jettisoning my equipment, I spent hours following the magnificent birds through the cloud forest, completely unaware of time, property boundaries and assignments. When I finally returned to campus and explained my lack of results, my professor’s response surprised me. ‘Why do you think you have to explain yourself? What else could you possibly have done?

You’ve probably just had one of the most profound spiritual experiences of your life. Don’t forget it.’”

Jessie RathburnSuddenly, my work had to catch up with the rest of me. For years, I had been on a path to a lifetime in academia: completing graduate school, teaching at a community college and finally, being a founding senior instructor at the Colorado University ESL Academy. My work was enjoyable; teaching international students at a university, and experiencing the complexities of multiple cultures, traditions and languages coming together was important and challenging. However, I felt off center, and I finally faced the crossroads I had been avoiding. Leaving my burgeoning career in academia, I started to manage a small urban farm on the edge of downtown Denver. Growing food and growing community — this is where I found a new path. On our roughly half-acre farm, we cleared a way for life to flourish. Beehives, worm bins, compost piles, a small fruit orchard, an aquaponics greenhouse and rows and rows of vegetables — I found new joy in each of these. Within a few years, after growing thousands of vegetable starts for school gardens and providing fresh produce to the local community, the city of Denver took back the land for development, bulldozing our orchard, burying our strawberry plants and crushing our dreams for the land. My heart broke as I witnessed firsthand this sanctioned ecological destruction. Where was justice for Earth?

Looking back at the many places I’ve called home, in each I have witnessed ecological and environmental injustice. When living in Russia, I witnessed illegal foresting connected to the furniture business. In Texas, Colorado and Kentucky, I have witnessed rampant development leading to environmental degradation, loss of habitat and further marginalization of already-marginalized human communities. In Louisville, Kentucky we witness environmental injustice and environmental racism in the shortened life expectancy in so many low-income communities and communities of color surrounding Rubbertown, a neighborhood of Louisville, Kentucky that has housed industrial plants that expose individuals to toxic chemicals.

Witnessing is not just an act of seeing; it compels one to testify, to stand and name what is seen and perhaps to advocate for an alternative. Witnessing is now becoming an act of living into my faith and spirituality. “Faith defies logic and propels us beyond hope because it is not attached to our desires. Faith is the centerpiece of a connected life. It allows us to live by the grace of invisible strands. It is a belief in a wisdom superior to our own” (Terry Tempest Williams, Refuge). Understanding my place in the universe,

my connectedness with all other forms of life, is an act of faith that compels me to testify. People of faith have long had a prophetic role. In this time when the climate crisis is amplifying all forms of environmental injustice, we are facing an ethical crisis in which humanity must re-understand our relationship with the planet. In this moment, faith communities are called anew to help society remember who we are and what values we hold.

As Earth continues along her evolutionary path, so do we as humans. What role do we want to play in this moment of human history? Our story as a species is not complete, and we stand at a pivotal point, presented with another contradiction: We are the species that has caused massive destruction to the rest of Earth. We are also integral to Earth’s ecology and can play a crucial role in offering healing and restoration, in re-membering our place in the universe.

Chris Schimmoeller lives in Franklin, Kentucky with her husband and two daughters. Growing up, Chris was a talented and award-winning athlete. She played volleyball and received many athletic honors, including being named a National Scholar Athlete twice. After high school she attended Georgetown University, graduating in 1991. The next year she was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to study in India.

Chris has dedicated her life to environmental issues. She states, “I remember when I was a kid walking through a field of tall grass … I realized my skin was not a barrier to the grass — we were one.” (Interchange, 2014). She talks about the influence of her family upbringing. Her mother was a Volunteers in Service to America volunteer at age 18 and was adopted by a Navajo family. This experience had quite an influence on her mother’s life, and as a consequence, on her own life.

Chris was part of the founding of Kentucky Heartwood in 1992, a grassroots organization focused on public lands protection. Its mission is, “To protect and restore the integrity, stability and beauty of Kentucky’s native forests and biotic communities through research, education, advocacy and community engagement.” Kentucky Heartwood helped reduce logging in the Daniel Boone National Forest by 97 percent. See: https://Kyheartwood.org.

Chris was crucial to the development of Woods and Water Land Trust that focuses on the protection of forestland in three Kentucky counties. She was the founding board chair from 2007 to 2019 and continues to volunteer for the organization. See: https://www.woodsandwaterstrust.org/. Chris also serves as president of Envision Franklin County, a body of volunteers with one goal in mind: improve Franklin County, Kentucky. They are, “promoting a healthy, beautiful and thriving community and encouraging development that results in good relationships among people, the land and future generations.”

The Loretto Community met Chris, an eco-justice feminist, during a Celebrating Rural Kentucky Women event when the Loretto Earth Network honored Chris and her work.

Chris’s words speak to her passion: This, my friends, is the time when we must use all that we have on behalf of all that we hope for. Whether you are 20 or 40 or 60 or 80 years old, this is your generation, for what we do in this generation will define our legacy as a species and determine the fate of countless other species.

“I call on the turtle and the bear to give us strength. I call on the wolf and the owl to give us wisdom. I call on the butterfly and the snake to give us endurance. I call on the coyote and the crow to give us creativity. I call on the fish and the bat to give us joy.

“We are the lucky gene pool, the lucky few, and now’s our time to gather up our blessings and bravely lead the way into a new world where we see beauty as in the Navajo blessing: ‘Beauty before me, beauty behind me, beauty below me. I walk in beauty.’”

For all these efforts and more, Chris was awarded a Kentucky Governor’s Service Award in 2017. She was also honored as a CREDO Climate Hero for being an exceptional activist who is taking bold and confrontational action on climate. For more on CREDO Climate Heroes visit: https://medium.com/@CREDOMobile/meet-the-credoclimate-heroes-daf4601fa972. Chris organizes against fracked gas pipelines in Kentucky. When receiving the award, she shared the following: “I am a homeschooling mom who homesteads with my family in rural Franklin County. I joined other Kentuckians in the amazing successful grassroots effort to stop the Bluegrass Hazardous Liquids Pipeline, which would have run through my county.”

As of this writing, Chris and her family have made a conscious decision to live free of the power grid in the woods of northern Franklin County. She and her family do not use electricity and have been cooking using solar energy for over 20 years. Her siblings have joined her on the land, and all are raising their children in an alternative lifestyle. When asked about her work in stopping the Bluegrass Pipeline, Chris answered, ‘To me it’s an issue of justice.”

We are the lucky gene pool, the lucky few, and now’s our time to gather up our blessings and bravely lead the way into a new world where we see beauty as in the Navajo blessing: ‘Beauty before me, beauty behind me, beauty below me. I walk in beauty.’”

Chris Schimmoeller

Two women, Jessie and Chris, who both live in Kentucky at the time of this writing, are dedicating their lives to work and action that demonstrate environmental justice and their love of earth. As you can see from their stories, each has a special reverence for nature, its beauty and lessons. This reverence has translated into action, personal life choices and career paths that require a commitment to our planet home, Earth, and to social justice work that addresses the causes of our Earth’s destruction.

Individual Student Response:

• Research to see if your community is doing anything to combat climate change. What are they doing at the city or county level?

• Ask your parents about climate change and their worries about how it might affect your life.

Read the following words of Terry Tempest Williams, whom Jessie mentions in her story.

Faith defies logic and propels us beyond hope because it is not attached to our desires. Faith is the centerpiece of a connected life. It allows us to live by the grace of invisible strands. It is a belief in a wisdom superior to our own.” Terry Tempest Williams, Refuge

Look up the book Refuge by Terry Tempest Williams. Reflect on where you find wisdom and faith.

Does nature connect to your faith, as it has for Jessie?

1. Find out what your school is doing to make a difference, big or small, on the impact of climate change. Prepare a report and present it to the principal.

2. Calculate the food miles of all you ate yesterday. A food mile is the distance from the source of the food (generally found on the label), divided by the number of ounces the food weighs. The idea of food miles was created to raise awareness that transporting food adds to carbon emissions globally. For more information see: https://www.bbcgoodfood.com/howto/guide/facts-about-food-miles

Kubasak, T., Interchange, a publication of the Loretto Community, February 24, 2018

Schimmoeller, C. Earth First!, September, October 2003

Williams, T.T. Refuge: An unnatural history of family and place. New York: Vintage Books, 1991

In 2023, and likely beyond, you cannot go a week without hearing about the environmental and climate crises that face our planet. All parts of life are affected — from unusual heat across the globe, to wildfires, to scarcity of water in many areas, to changing tides. We see it, and we feel it.

According to the United Nations:

Climate change refers to long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns. These shifts may be natural, such as through variations in the solar cycle. But since the 1800s, human activities have been the main driver of climate change, primarily due to burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas.

“Burning fossil fuels generates greenhouse gas emissions that act like a blanket wrapped around the Earth, trapping the sun’s heat and raising temperatures” (https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change).

Understanding climate change causes and consequences is a significant part of creating change. However, it is not enough. Learning Loretto values, working for justice and acting for peace — this means taking action, personally and in community, to create the changes needed in how we live our lives and how we push for change.

The United Nations notes, “Young people’s unprecedented mobilization around the world shows the massive power they possess to hold decision-makers accountable. Their message is clear: the older generation has failed, and it is the young who will pay in full — with their very futures” (https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/youthin-action).

You can be part of the change in many ways: as a student learning about climate change, as an advocate working with others, as a professional in the field, as a future parent securing the future for those not yet born.

Two women with unique stories help us see how to think about and address climate change. The first is Sister Mary Ann Coyle who used her gift of writing to express the meaning of being in relationship with our Earth. The second is Greta Thunberg, a youth activist who became a worldwide champion in 2016 by challenging those in power about the need for a response to the climate crisis.

The Loretto Earth Network exists to educate and alert its members and all who would join them in the mystery and the miracle of creation and the crisis that threatens our universe.

Mary Ann Coyle was born on November 1, 1925 in Des Moines, Iowa. She attended Loretto Heights College in Denver and in 1948 earned a bachelor’s in chemistry with minors in biology, history and philosophy. She entered the Loretto Community in 1952 and went on to earn a master’s in chemistry from Catholic University in Washington, D.C. in 1958 and a doctorate in organic chemistry from the University of Colorado in 1964. Mary Ann spent many years as a teacher and administrator at St. Mary’s Academy in Colorado, setting the stage for the school’s success for many years to come.

Mary Ann demonstrated leadership throughout her life in Loretto. She was president of the Loretto Community from 1994 to 2001 and used her strong leadership skills to lead the Community forward. One of Mary Ann’s major commitments was educating and acting for the protection of Earth. She was committed to the health and future of our planet and was active in the Loretto Earth Network, a

mission project of the Loretto Community that promotes practices and education for sustainability.

For many years, Mary Ann acted as editor of the Loretto Earth Network publication. These three quotes are Mary Ann’s, from the Loretto Earth Network publication that paid tribute to her following her death:

We care passionately for this Earth of magnificent, vibrant diversity. When we are faced with apparently divergent values, let us delight in our bioregion and savor the wisdom Nature brings us.”

“Rest for a bit, pick up your journal and list for yourself the efforts you are making on a regular basis to let GREEN be primary in your life and thinking. As the mystic and poet Rumi writes, ‘There is a fountain inside you — don’t walk around with an empty bucket.’”

“Today we find young people, midlife folks, wise elders and ancient ones united in their thoughts about the changes we must make if life on this planet is to persist for future generations.”

The Loretto Earth Network lived on in part because of the passion and commitment of Mary Ann Coyle. Her words and spirit can live on in all of us, especially those who embrace Loretto values. We are challenged to move out into all corners of our world, to breathe life into the future of our environments and our precious Earth.

In a tribute to Mary Ann in a 1993 edition of Loretto Magazine, Thomas Berry challenged Loretto to be aware of and reflect on the single sacred community of the entire universe. He wrote, “Throughout the natural world there is an intimacy of things with each other. The intimacy of the wind and the soaring raptors, the rain and the vegetation, the sea and the shore. So too the intimacy of the bee with the flower, the intimacy of the bluebird parents with the newly hatched young.” Berry indicated that we would see a renewal of existing religious communities and the rise of new ones as soon as “we recognize and dedicate ourselves to the great work before us, the renewal of Earth as the presence of the Divine.”

We must do everything we can imagine to create right relationships so that our planet Earth will remain vital for human and nonhuman life.

Today we find young people, midlife folks, wise elders and ancient ones united in their thoughts about the changes we must make if life on this planet is to persist for future generations.”

Mary Ann Coyle

So often, we hear of another disaster related to the climate crisis and think, “What can I do?” Greta Thunberg thought that too, and this is the story of what she did. Greta was born in Stockholm, Sweden on January 3, 2003. At age 15 she began her quest to become a world advocate for the climate crisis. First, Greta skipped school on a Friday and took off for the parliament building with a sign indicating that she was beginning a strike. She called it School Strike for Climate. On each subsequent Friday, she showed up with the same sign.

In 2018, at age 16, she decided to take a sabbatical year from school so she could travel the world and advocate for action on the climate crisis. She spoke to leaders of the world at the UN Climate Change COP24 Conference in Poland and told them in no uncertain terms that they COULD do something about the climate crisis. Following that momentous occasion, she got on a boat with her father and sailed to the United States. She sailed because she was unwilling to incur the carbon footprint of flying. She spoke to groups of young people in the U.S. and encouraged them to walk out in support of school strikes for climate action and change.

In addition to her trip to the United States, Greta traveled around Europe, met with world leaders and pressed for change. She criticized older generations for not doing more and stated dramatically wherever she could, “The world is on fire.”

When some raised questions about Greta’s Asperger’s syndrome, she let them know in no uncertain terms that it helps her to focus on the climate crisis; this is manifested in how clearly she has been able to articulate her beliefs while speaking to worldwide leaders and crowds of supporters. She became a hero at age 16.

In 2019 Greta and five other young people filed a lawsuit with the UN Commission on the Rights of Children. The suit was against five counties — Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany and Turkey—and stated that these countries were breaching their obligations under the International Convention on the Rights of the Child by promoting fossil

fuels and failing to curb greenhouse gas emissions for decades. On this occasion Greta said,

You have stolen my childhood with your empty words.”

Greta’s life shows what one can do when faced with a crisis. She is courageous and creative and will continue to act through her foundation and personal appearances. After winning the Gulbenkian Prize for Humanity in 2020, Thunberg made a video in which she said, “The prize money, which is €1 million — that is more money than what I can even begin to imagine — but all the prize money will be donated through my foundation to different organizations and projects who are working to help people in the front lines affected by the climate crisis and ecological crisis especially in the Global South.” The video was published by the Guardian.

What

can I do?

Mary Ann and Greta, two powerful women, have given their spirits and talents to further our understanding and motivitate us to take action to change the impacts of the climate crisis. They speak truth to power so we all can hear.

1. Read one of Greta Thunberg’s speeches or books. Identify the values named or implied and the positions taken on the climate crisis. Her books are: No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference (2019), Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis (2020), The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions (2023).

2. Write a letter to your parents or grandparents/elders and let them know of your concern about what you will inherit and how they can support you in making a difference in the care of our Earth.

1. Watch one of the videos at this site: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/youth-in-action, and discuss as a class how you can make a difference in your home and school communities.

2. In small groups, research the organizations that are working for change in relation to the climate crisis. Debate about the different strategies for change that you find (e.g. acting in the streets, researching, working on legislation locally or nationally, working in developing countries or other ideas you discover).

3. Small group discussion questions:

What are the barriers to our connection with the Earth? How can you remove some of these barriers? Watch a video clip of Greta’s “blah blah blah” speech at the Youth 4 Climate conference in fall 2021. What does she achieve by mocking those in power? Why does she insist that change will not come from those in power?

1. Have a discussion within your family or with those who care for you about what you would like to do as a group to address the climate crisis.

2. Find local organizations in your city or state that are taking action to address the climate crisis. Find out if youth are involved and if you can attend a meeting.

3. Write a letter to your state or national legislators about your concern as a young person for the future of our world.

Ideas about leadership have shifted considerably since the 1990s. The old hierarchical model with the notion of “the buck stops here,” with one leader at the top of an organization, has given way to a newer collaborative model in which leadership happens more in a circle, drawing on the many skills of all who are participating. The term “leaderful” has come into being, named by Black Lives Matter and others as a new way to think about leadership (JA Raelin, 2003).

In this new leadership model, power does not belong to one person but to a team of people working together. Power dynamics are minimized as the team works together maximizing their varied skills. Individuals come to the table with a commitment to bring their authentic selves, an openness to change and a spirit of support for the other team members.

The following two stories span many generations of the 20th century and move into the 21st. The first story is of Sister Mary Luke Tobin, an internationally known Sister of Loretto who represents the changing times of the 20th century in the lives of women religious and the Catholic Church. The second story is about Malala Yousafzai, the young Pakistani woman who is world renowned for her commitment to change by advocating for education for all. They are leaders of their time and serve as an inspiration to all who hope for new leadership models in the world.

Reference: JA Raelin, Creating Leaderful Organizations: How to Bring Out Leadership in Everyone, Berrett-Koehler, 2003

uth Marie Tobin was born in 1908 in Denver. She attended Loretto Heights College and joined the Sisters of Loretto in 1927, taking the name Mary Luke; she was often known as just Luke. In her early career she taught in the Loretto schools, and in 1958 she became the president of the Loretto Community and served for 12 years, until 1970.

The years of Mary Luke’s presidency were very important because they happened during the Roman Catholic Church’s Vatican II Council which ushered in significant changes for the Church and women’s religious communities. Mary Luke wasted no time in implementing changes, such as trading traditional habits for the dress of the day and allowing sisters to move into communities of their choice in housing within neighborhoods. There were also changes regarding work choices which meant that many sisters found new ways to serve. Mary Luke helped make the transition of turning over the schools run by Sisters of Loretto to boards that included those outside of the Loretto Community.

Sisters were becoming social workers, lawyers and doctors, as well as other professionals. It was a tumultuous time and demanded extraordinary skills to keep the Community together while transitioning into new ways of living religious life. Mary Luke was the woman for the job.

Many remember how Mary Luke had the custom of walking with the upper half of her body tilted forward. Was it because, as a young woman she was a ballet dancer, or was it an indication that she was a woman moving things ever forward? Even in her 90s at the end of Mass, she would step away from the pew and treat the Community to a lovely dance to bring things to a close.

One of Mary Luke’s dear friends was the Trappist monk and writer Thomas Merton. They became acquainted because the monastery where he lived was down the road from the Loretto Motherhouse in Kentucky. Mary Luke called on him to give talks to the novices or young nuns, and this was an opportunity for them to become good friends. Mary Luke referred to this coming to know one another as “the door to prophetic friendship.” They exchanged opinions on what was developing in the Church

and in the world, each having a kind of prophetic vision around how things might evolve. It was a privilege for Loretto to have this familiarity with another deeply insightful and wise person. Along with Dorothy Day, Merton was acknowledged as one of the most important persons in American Catholicism by Pope Francis when he spoke to Congress during a visit to the United States in 2015. After Merton’s death, Mary Luke co-founded the International Thomas Merton Society.

Mary Luke was a feminist who did not cower before men, even when they were members of the Church hierarchy. She had many male friends who respected and honored her courage as she spoke of the equality of all people. She displayed a sense of inner authority when she spoke, and people often were inspired by her words. She contributed with a prophetic voice to the growth of feminism among religious women. While she was president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, she was asked to go to Rome as the Vatican II Council was being held. She was on a ship to Italy when she was told that she was invited to attend the Council as an official observer. Despite her observer role, there is no doubt that she took the opportunity to speak truth to the powerful people in attendance.

Activism was no stranger to Mary Luke. She engaged with many issues of social justice and would often be seen at protests against war, nuclear weapons and for women’s rights, farm workers’ rights and rights of the poor and homeless. She went to Vietnam in the 1970s with a group of religious leaders who were arrested for protesting there. She was arrested protesting the Vietnam war in Washington, D.C. and at a Colorado Air Force base. She was a fearless and welcome companion at many of these events.

Mary Luke delighted in the Community’s changes as well as the seismic changes within the Church. She was a lifelong learner and was generous about sharing her insights. How blessed the Loretto Community was to have such a leader at just the right time.

Resource: Obituary in The National Catholic Reporter, August 25, 2006

Some leaders rise out of tragic circumstances to help others who suffer from abuse and oppression. They create nonprofits and social movements dedicated to overcoming oppression.

Malala Yousafzai is just such a woman. Malala was born in 1997 in the beautiful Swat Valley in Pakistan. Her father was a teacher, and a man who fought for the rights of girls to receive an education. Malala, greatly influenced by her father, began early in her life to embrace her father’s commitment. At the age of 11, she began writing a blog supporting the rights of girls to be educated. She published the blog under a false name. The Taliban in her area did everything to discourage girls from getting an education including destroying many of the schools in the region. Malala and her father were not deterred in their efforts to keep girls in schools.

When she was 15 she was riding home on a school bus when the bus was stopped and a man from the Taliban entered. He demanded to know who was Malala. Though no one pointed her out, he could tell because students were looking at her. He shot her in the head.

Within a week Malala was flown to the United Kingdom to receive medical care. In the course of the following year, Malala recovered and was invited to speak to the United Nations. There she said,

Today is the day of every woman, boy and girl who has raised their voice for their rights. Let us wage a global struggle against illiteracy, poverty and terrorism. Let us pick up our books and pens, they are our most powerful weapons. Education is the only solution. Education first.”

Malala has said, “I don’t want to be famous for being the girl who was shot by the Taliban. I want to be the girl who fights for education.” In 2014 Malala, at age 17, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. On receiving the prize, she said, “Why is it that countries which we call strong are so powerful in creating wars but are so weak in bringing peace? Why is it that giving guns is so easy but giving books is so hard? Why is it that making tanks is so easy and building schools is so hard?”

In 2020 Malala graduated from the Lady Margaret Hall of Oxford. She studied philosophy, politics and economics. She had already cofounded the Malala Fund which carries on the work of supporting educational opportunities for girls globally. This is where Malala works as of this writing.

In an interview with Emma Watson, Malala was asked whether or not she is a feminist. Malala’s response was, “I hesitated in calling myself a feminist … then after hearing your speech I decided … there is nothing wrong by calling yourself a feminist. So, I am a feminist and we all should be a feminist because feminism is another word for equality.”

How fortunate we are to come to know about the life of Malala — her courage in speaking truth to power and her tenacity in remaining dedicated to struggling for the rights of girls to be educated. Surely her commitment will be a force for change and more and more people will know the name Malala.

Mary Luke Tobin and Malala Yousafzai, many years apart in their work, have a common spirit, standing out among many to seize a moment and create new responses to world events. They are prophets of their times and yet humble to the core — servant leaders embracing the spirit of guiding and enabling others to act.

1. Write a short essay about how the Catholic Church has changed its practices from the 1950s to today. Why do you think these changes occurred? What is the difference between changes made from the top and changes made on the ground?

2. Research the status of women in Pakistan today. What has changed since 2012 when Malala was shot, and what has stayed the same?

1. In-class writing: In two paragraphs write your ideas about the kind of leadership that is willing to take a stand and create conditions for change. Is it brave? Is it hard? Why or why not?

2. Watch the Ted Talk by Ziauddin Yousafzai, Malala’s father.

3. Think about the current changing times. What changes have you noticed from your years in elementary school to now? If you want to be a leaderful leader in college or after college, what skills do you think you will need? Meet in teams of four, come up with a list and share with the class.

1. Prepare a statement for the board of directors or the principal of your school on why girl’s education is important and how your school can speak up publicly.

2. With a friend, analyze the leadership styles of two people you admire. What are their strengths? Why do people take them seriously to the point that they too take action? Are you a leader? What would it take for you to take initiative to make a change that matters deeply to you?

Books to Read: Half the Sky by Sheryl Wu Dunn and Nicholas Kristof is full of stories about women who have turned around their lives and made contributions to their communities. Half the Sky, Knopf, 2009

The Book of Gutsy Women by Hillary Clinton and Chelsea Clinton, Simon & Schuster, 2019

Resources: The Malala Fund; Wikipedia; Malala’s Speech to the UN; Malala’s acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize

Reference: Raelin, J.A.. Creating Leaderful Organizations: How to Bring Leadership Out in Everyone, San Francisco, Berrett-Koehler, 2003

Women of Spirit, Courage and Action—page 40

When a wise woman leads, she calls a circle and makes a space for stories to be shared, hopes to be uttered, revelation to unfold.

When a wise woman leads, she leads from stillness — where she gathers herself, mines her experience, and turns her wisdom into story.

When a wise woman leads, she dares to be vulnerable, dares to be real, dares to speak from a place of unknowing.

When a wise woman leads, the experience of the journey is as important as arriving.

When a wise woman leads, she thinks with her head, ponders with her heart, decides with her soul.

When a wise woman leads, she knows when to leave, when to let go and when to push on.

When a wisewoman leads, she speaks with the intensity of fire, the freshness of air, the groundedness of earth, the depth of the sea.

When a wise woman leads, she bears witness to our oneness and chooses what is best for the common good.

She is a tempest against injustice, a torrent of hopefulness, a wellspring of wisdom.

She leads for the benefit of all beings, that life will be sustained, that well-being will prevail, that goodness will shine over all our days.

Jan Phillips janphillips.com/ Loving Kind FoundationUsed by permission

What are borders? Are they something we have made official to divide people and countries? Are they real? What do they mean to those who cross them … and how are we defined by the borders we create?

Stepping into new roles and showing up in places most people would not even consider takes courage, questioning, hope, tenacity and a willingness to let it evolve. Beyond the borders of the United States to our south are our neighbors who have suffered greatly over the past decades and want what all of us want — a life of safety for themselves and their children, health, the ability to work and respect. Often these are hard to come by.

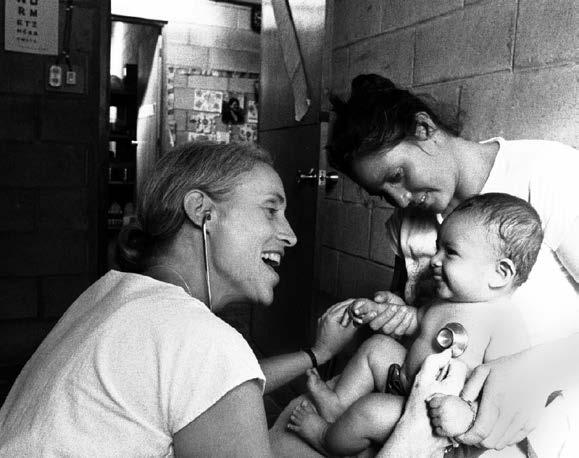

These two stories demonstrate commitment to those who suffer because of war, violence and poverty. The first story is about being present in the Central American country of El Salvador. The second story is about being present in Colorado to those who have escaped war, violence, poverty and climate disaster to seek asylum in the safety of the United States. In both stories, healing has been fostered.

As background to the work of Sister Ann Manganaro, it is important to understand the context of El Salvador in the early 1980s. The murder of Monsignor Oscar Romero in San Salvador in March of 1980, followed by the murders of four U.S. church women (Ita Ford, Jean Donovan, Maura Clark and Dorothy Kazel) in December of that year were propelling, disturbing events for U.S. women religious.

Loretto and other communities were proponents of justice, peacemaking and liberation theology in communities in Central America. The poor became our teachers and their plight our mission. We were increasingly aware of the involvement of the U.S. government in the perpetuation of unspeakable oppression and in orchestrating violence toward those who were educating or empowering the people. Teachers, priests, nuns, health care workers and community organizers were disappearing daily.

Ita, Jean, Maura and Dorothy had been working for some years with the poor of El Salvador where two percent of the population owned 100 percent of the fertile land. The unemployment rate was over 45 percent, and 50 percent of children died before the age of five. Thousands of Salvadorans had been disappeared, murdered and left destitute by the brutality of the government and military. In addition, 4,000-5,000 people had fled the country or been forced into refugee camps.

The four U.S. women were a threat to the powerful because they were not only serving the poor, they were empowering them to see and respond to the injustices perpetrated by rich landowners, the right-wing government and the U.S.backed military. They were teaching the principles of liberation theology — the kingdom of God is here and now, not a reward after this life. They were helping people to know that the oppression and violence they were living with was contrary to the Gospel mandate of justice, equality and peacemaking. These women were dangerous. Each was well aware

of this. They were friends of Archbishop Oscar Romero who was shot and killed in March 1980 while saying Mass.

By the time the women were murdered in December 1980, a peasant armed-resistance group had formed in response to the widespread brutal repression of human rights. These people who had suffered for so long were demanding land reform, democracy and justice. They felt they had no choice but to take up arms. They were the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, and a guerrilla uprising was underway in El Salvador.

In the fall of 1984 a group of women in El Salvador, the Mothers of the Disappeared, contacted Church Women United, an interdenominational group of women of faith in the U.S. The mothers invited the group to bring U.S. women on a delegation to El Salvador for the fourth anniversary of the murder of the U.S. women. The Mothers of the Disappeared and other justice groups in El Salvador were looking for ways to awaken the international community of faith and justice to the reality in El Salvador. It was especially critical that U.S. citizens realize what was being supported by U.S. tax dollars. Three women from the Loretto Community participated in that delegation of 30 U.S. church women.

For several years during the 1980s numerous Loretto Community members participated in fact-finding delegations, Witness for Peace and accompaniment of the people of Central America, including in Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and El Salvador. Teaching of the injustice and violence, informing U.S. citizens about the extensive use of tax dollars to support repressive regimes, and advocating for the U.S. to withdraw support to these governments was the task upon returning home. Ann Manganaro was called to respond.

In 1946 Ann Manganaro and her twin sister, Mary, were the first born into a Catholic family in St. Louis, Missouri that would grow to eight. She attended Loretto schools, Nerinx Hall High School and Webster University. She entered the Sisters of Loretto in 1964 at age 18. She helped establish an innovative preschool in a racially diverse neighborhood where she taught until she began medical school at St. Louis University in 1978.

As a pediatrician, Ann served on the faculty of Cardinal Glennon Hospital for Children in St. Louis, Missouri until she left for El Salvador in 1988. She practiced rural “barefoot doctor” medicine, teaching those who promot-

ed and provided healthcare; she bound the wounds of revolution for five years. In 1993, after deciding her next venture would be working in Mozambique, she returned to St. Louis for health reasons. She was diagnosed with metastatic bone cancer after having recovered from breast cancer eight years earlier. On June 6, 1993 Ann died in her family home, surrounded by many who loved her.

Ann’s friendship is a treasured gift to me. We were friends in the Loretto Community for many years, and I lived with her in Guarjila, El Salvador for four months in 1989. I was able to spend the last four weeks of her life with her in her family home in St. Louis.

It is never entirely complete for one person to describe or try to profile the life of another, even if they know each other well. We come from only a single perspective which is, of course, one of many. My time with Ann in El Salvador offers a unique perspective. Though Ann was admired and deeply respected by many, she was not a saint, a hero or a perfect person. She was a woman who was ever faithful to her awareness that the Gospel mandate is to be with and serve those who are poor and struggling. This was where she had to stay. Ann described herself as “ordinary.”

She was not motivated, in her own life, by self-sacrifice or strict discipline, though she was able to manage both when needed. Ann seemed to me to be motivated by love. She loved her work, her family, her friends, her community, her students, her patients and her ability to serve. There is a story about her holding a premature infant in the neonatal intensive care unit at the children’s hospital. The infant lived for a very brief time, just several hours. Someone asked Ann, after the infant died, how she dealt with such a sad and seemingly meaningless extinguishing of life. Her response was that the infant she held had the amazing power to draw love from those present. The value of that tenderness and love somehow had meaning and, to Ann’s way of seeing, that small, brief life that evoked love was not wasted. When asked by someone about what drew her to do the work that she did she replied, “Love is the whole thing. Love appropriately. Love truly.” She did her best to live faithfully by that mantra.

By Ann’s arrival in 1988 the war in El Salvador was fully escalated. She did not find it easy to deal with the chaos and tumult of war. However, she did all she could to tend to the myriad of medical needs around her. The people she grew to know and love were the resistance fighters, their

families and communities. And, as the months and years went by, the people grew to trust and love Ann deeply. They called her Hermana Ana.

Though her specialty was pediatrics, her work required every skill she could muster: amputation of limbs, midwifery, emergency attention to someone who attempted suicide by ingesting fertilizer, as well as helping those who suffered with grief and depression — they had lost so much. And the war was all around. Ann gave herself entirely to participating in the lives of the people in Guarjila, the resettlement village where she lived. It was one of the most heavily-conflicted areas of the country. More important than practicing medicine, Ann was a teacher. She shared her knowledge in simple and creative ways. By the time she left El Salvador she had trained more than 200 health workers; she had established a clinic, La Clinica Hermana Ana, that is operating today in Guarjila. Some of the youth trained in “barefoot doctor” techniques by Ann have gone on to obtain medical degrees and continue to practice in Guarjila and surrounding areas.

Ann Manganaro will never be forgotten by the people of Guarjila, El Salvador. When a large ship stops, the motion carries on in the sea. This is called the soliton wave. The motion of Ann’s gift carries on in each one of us who loved her. She is like the soliton wave.

The following biographical information about Jennifer Piper is from her nomination by Loretto Community members for the Mary Rhodes award in 2018. Jennifer was one of four women to receive that award.

Jennifer Piper first became conscious about immigrant rights during her time in the Peace Corps in Paraguay. In 2003, upon her return to the U.S. from South America, she became a member of Coloradans for Immigrant Rights, a project of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) in Colorado. She received her master’s in public policy and management and joined the AFSC staff as their interfaith organizing director for immigrant rights. Her work focused on fostering faith-based dialogue and actions supporting immigrants and immigration reform.

Jennifer lives and teaches accompaniment and the importance of lifting up the voices and leadership of immigrant communities. She asks, “How can we as immigrants and allies support the immigrant rights movement and co-create the beloved community?”

Her focus now is Sanctuary Everywhere, which works on ways to resist intimidation, police brutality, anti-immigrant sentiment, Islamophobia and other forms of oppression on the streets and beyond. Sanctuary Everywhere is the simple idea that everyday people can work together to keep each other safe. It’s about the community uniting to protect targeted communities from state violence — including immigrants, people of color, affected religious groups and LGBTQ folks. This movement will equip thousands of people with tools and training to stop hateful acts and to encourage policies and practices that promote safety and inclusion.

Jennifer teaches us how to work hard, have fun, listen, laugh, shoulder responsibility, strategize, engage politically, resist, heal, take care of each other and remain hopeful.

The profile that follows is by Martha Crawley from conversations with Jennifer.

Jennifer was raised in a Catholic family. Her mother was a nurse. Her father was a union member. Jennifer recalls learning about Catholic social teachings on principles of equality, the death penalty, the value of human life and caring for all people. She knew that retribution is not justice and participated in a youth program that deepened her learning about justice and inequalities. She realized early that, in order to know what to do, one has to listen, ask questions, be grounded and open. Jennifer describes her parents not as activists, but as thoughtful and well informed. She recalls watching the news with her dad, having conversations about global issues and asking questions. Her family valued strong communities, storytelling, traditions and responding to others in need. Her grandmother taught her that there were people who did not have enough to meet their basic needs. Her grandparents were foster parents, and she heard stories of lives not like her own, of struggling people, hurt people.