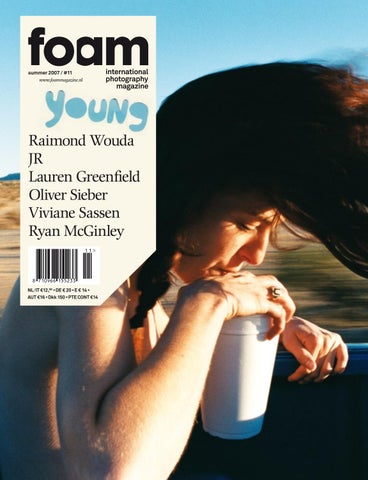

summer 2007 / #11

www.foammagazine.nl

Raimond Wouda JR Lauren Greenfield Oliver Sieber Viviane Sassen Ryan McGinley

NL/IT €12,50 • DE € 20 • E € 14 • AUT €16 • Dkk 150 • PTE CONT €14

summer 2007 / #11

www.foammagazine.nl

Raimond Wouda JR Lauren Greenfield Oliver Sieber Viviane Sassen Ryan McGinley

NL/IT €12,50 • DE € 20 • E € 14 • AUT €16 • Dkk 150 • PTE CONT €14