Ambient Flo, BackRoad Gee, Berwyn, Blue Bendy, Gary Indiana, Iglooghost, Julien Baker Karima Walker, Lucy Gooch, Viagra Boys, Virginia Wing, A Beginner’s Guide to MF DOOM

issue 145

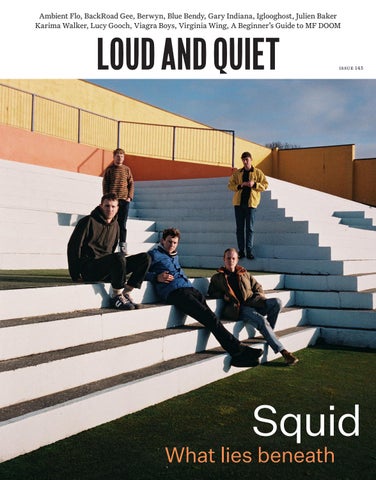

Squid

What lies beneath

BLACK COUNTRY, NEW ROAD FOR THE FIRST TIME

BICEP ISLES

LEON VYNEHALL RARE, FOREVER

TSHA FLOWERS

PVA TONER

ACTRESS KARMA & DESIRE

FRESIA MAGDALENA

BONOBO & TOTALLY ENORMOUS EXTINCT DINOSAURS

HEARTBREAK / 6000 FT

SOFIA KOURTESIS FRESIA MAGDALENA

Contents Contact info@loudandquiet.com advertise@loudandquiet.com

Loud And Quiet Ltd PO Box 67915 London NW1W 8TH

This edition goes out to our team who scrambled to make it happen. Christmas always gets in the way of our first issue of a new year but we’ve never known logistical nightmares like those created by the third national lockdown. With safety of course the priority, interviewing artists in the flesh has become increasingly difficult to arrange, although you’d never know it from our writers’ abilities to make conversations over Zoom feel unnaturally not awful. Photo shoots are now their own fresh hell, but from Bristol to Stockholm, everything here was put together safely with the commitment of our team. And it’s a pleasure to start 2021 with Squid. Stuart Stubbs

Founding Editor: Stuart Stubbs Deputy Editor: Luke Cartledge Art Direction: B.A.M. Digital Director: Greg Cochrane Contributing writers Abi Crawford, Al Mills, Alex Francis, Alexander Smail, Colin Groundwater, Dafydd Jenkins, Daniel Dylan-Wray, Dominic Haley, Esme Bennett, Fergal Kinney, Gemma Samways, Guia Cortassa, Isabelle Crabtree, Ian Roebuck, Jamie Haworth, Jess Wrigglesworth, Jemima Skala, Jenessa Williams, Jess Wrigglesworth, Jo Higgs, Joe Goggins, Katie Beswick, Katie Cutforth, Liam Konemann, Lisa Busby, Max Pilley, Megan Wallace, Ollie Rankine, Oskar Jeff, Robert Davidson, Reef Younis, Sam Reid, Sam Walton, Skye Butchard, Sophia Powell, Susan Darlington, Tara Joshi, Tom Critten, Tristan Gatward, Woody Delaney, Zara Hedderman.

Issue 145

Contributing photographers Andrew Mangum, Annie Forrest, Charlotte Patmore, Colin Medley, Dave Kasnic, David Cortes, Dan Kendall, Dustin Condren, Emily Malan, Gabriel Green, Gem Harris, Heather Mccutcheon, Jake Kenny, Jenna Foxton, Jody Evans, Jonangelo Molinari, Levi Mandel, Matilda Hill-Jenkins, Nathanael Turner, Nathaniel Wood, Oliver Halstead, Phil Sharp, Sonny McCartney, Sophie Barloc, Timothy Cochrane, Tom Porter. With special thanks to Andy and Barbara Thatcher at Portishead Open Air Pool, Ebi Sampson, Frankie Davidson, Jenna Jones, Jon Wilkinson, Lee Wakefield, Maddy O’keefe, Nathan Beazer, Nisa Kelly, Noam Klar, Sinead Mills, Tom Mehrtens. The views expressed in Loud And Quiet are those of the respective contributors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the magazine or its staff. All rights reserved 2021 Loud And Quiet Ltd.

ISSN 2049-9892 Printed by Gemini Print Distributed by Loud And Quiet Ltd. & Forte

Julien Baker . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 Berwyn . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 Lucy Gooch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16 BackRoad Gee . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 Blue Bendy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 Gary, Indiana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28 Karima Walker . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30 Squid . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52 A Beginner’s Guide to MF DOOM . . . . 60 Ambient Flo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64 Was Craig David robbed at the Brits? 66 Iglooghost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68 Virginia Wing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74 Viagra Boys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78 03

The Beginning: Previously

Since the last edition of Loud And Quiet

Hey Moon Following the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, Swedish musician Molly Nilsson has reclaimed her largely disowned – but most well known – song ‘Hey Moon’. The track originally featured on Nilsson’s 2008 CDR debut album but found wider success when it was covered by John Maus on his 2011 record We Must Become the Pitiless Censors of Ourselves. With Nilsson’s alt-pop talents forever underrated, many have always mistaken ‘Hey Moon’ as a Maus original, causing Nilsson to distance herself from it and abandon performing the track live. When an

04

Instagram post confirmed that Maus (a shock) and Ariel Pink (less so) had both attended the Capitol Hill protest in support of Trump, though, Nilsson announced her reclamation of the song, releasing it as a 7-inch single with all proceeds going to Black Lives Matter. As Nilsson told Fader last month: “I was very happy to just take [“Hey Moon”] that maybe people feel has been a bit destroyed by these events, and put it in the opposite context.” So far the single has raised £4500 for BLM and will remain in print indefinitely. Copies are available via Night School Records and Nilsson’s own label Dark Skies Association.

The Beginning: Previously RIP MF DOOM New Year’s Eve 2020 / 2021 was never going to be one for the ages, but the news that reached us a few lonely drinks deep into the ‘celebrations’ didn’t exactly help. Daniel Dumile, aka MF DOOM, aka one of the greatest rappers and lyricists of his generation, had passed away aged 49. He had actually died a couple of months earlier on October 31, but his family understandably took a little time to themselves before making the news public. Outpourings from across the alternative music universe followed – he really was a special talent; a king collaborator. For an in-depth study of why he mattered so much, check out Oskar Jeff’s tribute on page 60.

Get Buzzin’ with Bez In early January, Bez announced his plans to launch a new fitness channel called Get Buzzin’ with Bez. It didn’t sound right at all, unless you’ve never seen Bez try to do absolutely anything. On January 17, though, episode one dropped and a nation ate its hat. Key to Get Buzzin’ is that Bez isn’t leading the class at all – he’s lagging at the back to help you feel better about yourself. Capturing the true horror of exercise, Bez is close mic’d to make sure we don’t miss a single heavy breath, or the moment when he tells his PT, “I haven’t run since 1999”, or when he notes, “it’s like going to the toilet” as he’s shown how to do squats. He stops letting out an “ooooph” and giggling after the first three reps, once the pain sets in. Follow Bez’s quest to be less mashed on YouTube.

Sister Midnight Records In the couple of years prior to the pandemic, Deptford’s Sister Midnight Records became one of South London’s most cherished hubs of forward-thinking new music. This tiny basement venue (capacity 50ish, depending on how sweaty you’re willing to get) and the record shop-cum-cafe at street level was a focal point of this most celebrated scene, but coronavirus has forced the owners to rethink things. In January they announced that they’ll be closing the Deptford space but are hoping to reopen on the premises of an abandoned Lewisham pub, the Ravensbourne Arms, and open the venue up to democratic community ownership. In an age of closures and generalised anxiety, this is a beacon of hope. Get involved via sistermidnightrecords.co.uk.

The future of EU touring Now that Britain is no longer a member of the European Union, the arrangements British musicians had to allow EU-wide touring have expired. This has serious implications for the future of the music industry as we know it: 44% of UK-based musicians earn up to half of their income from work within the EU. To access those audiences, most will now have to pay prohibitive fees for visas and work permits; conversely, international artists coming to the UK will no longer be able to enter the country with the EU-wide arrangements they’ve made for the rest of the continent, which

illustration by kate prior

will have a knock-on effect on UK festivals and venues. Importantly, though, for many artists from around the world this is nothing new, and it goes without saying that already-marginalised groups, often from the global south, have always been hit hardest by such restrictive work and immigration policies. The campaign to restore working rights to UK and EU musicians must therefore also include solidarity with those artists as well. For more on this, do check out the extensive Quietus.com report ‘Solidarity Beyond Borders: Why Artist Visas Are More Than A Brexit Issue’. Sign the petition for British artists to be granted Europe-wide visa-free touring permits at petition.parliament.uk/ petitions/563294.

Big Dada Since its launch in 1997, Big Dada has been at the forefront of UK rap and bass music, having released pioneering works by Roots Manuva, Speech Debelle, Jammer, Kae Tempest and many others. True to the origin of most of the music it releases, the label is now relaunching as an imprint run by Black, POC and minority ethnic people to work with artists from those same backgrounds. In a statement on January 25, the label announced: “Working to amplify Black and racialised artists’ voices, Big Dada looks to shift the narrative around this music, bypassing stereotypes to allow and encourage freedom to express oneself for who they are and want to be.”

Recent Peal January ended with Wesley Gonzalez launching a new podcast called Recent Peel. It’s available exclusively on Spotify to make use of their ability to play complete tracks within show, and will now drop on the final Tuesday of every month, where Gonzalez – an encyclopedia of underground and excellent music – will share his favourite recent discoveries, old and new, from every genre you know of, and more you don’t.

SMtv Nobody was expecting live shows to return to the UK anytime soon, but the third national lockdown has also seen the cancelling of streamed gigs performed to empty rooms. After Sleaford Mods were forced to pull their planned show, The Demise of Planet X, at London’s Village Underground on January 9, they put together a TV special for broadcast the following week. The hour-long SMtv aired at 8pm on January 16 and featured the band in conversation discussing new album Spare Ribs, live footage from their 2020 100 Club show, some repurposed Sky News graphics and guests including Iggy Pop and John Thomson as his Fast Show ‘Jazz Club’ character. A few weeks later, Arlo Parks premiered her own pre-record special via Amazon Music, although only one of them featured Robbie Williams calling in to ask, “What colour is Tuesday?” and Jason Williamson responding, “Feces.” The show is now available on the band’s YouTube channel.

05

Live from the Barbican Concerts streamed from our Hall to your home

Sun 17 Jan Moses Boyd Sat 23 Jan This Is The Kit Fri 6 Feb Paul Weller Mon 15 Feb Shirley Collins Sun 21 Feb GoGo Penguin Thu 25 Feb 12 Ensemble with Anna Meredith & Jonny Greenwood Tue 30 Mar Nadine Shah

The Beginning: Witness the Fitness

A brief history of our horrible workout goals

It used to be that we lived in caves. We feared our neighbours because they might eat our brains, so we killed them. We chased animals and killed those too. Life was hard. But boy, did we have great abs! Now we shelter in houses instead of caves, and fear our neighbours for their germ-spreading rather than brain-eating tendencies. But our abs? They are nowhere to be seen, destroyed by our love of all things baked, fermented and sucked out of animals. Luckily, a saviour was sent to help us recover those lost abs. A man with warm, chocolate eyes and soft, bouncy hair. A man who looked a bit like Russell Brand but was even more annoying. A man named Joe Wicks. Over the last few years Joe Wicks has become unavoidable. He’s in shops, staring at you from the front covers of books while brandishing root vegetables. He’s on breakfast television, sitting on the sofa like a well-trained poodle. He’s on your computer screen, jumping around and shouting in his unconvincing cockney accent. He’s inside your head, and he won’t leave until all of the crisps, cheese and grease are gone; until you are one giant, pulsating abdominal muscle. But Joe Wicks is more than just an annoying man. He mirrors our ambitions, our lusts and our vanities. Each time he holds a head of broccoli in his hand and says “Cor blimey!” it means something. To understand Joe Wicks is to understand ourselves. But before we can, we must first look back into the past, to the people that created our modern fitness messiah. Ever since our ancestors realised that horses weren’t just potential sex partners but could also be used as transport, humans have been growing fatter, and fitness coaches more popular. However, fitness gurus in the modern sense arrived with the advent of radio. Joe Murgatroyd launched his radio show in the UK in the 1930s. Laughing maniacally throughout – his programme was

words by andrew anderson. illustration by kate prior

called Laugh and Grow Fit – Murgatroyd presented fitness as a way of suppressing emotions and avoiding imminent death. Given that life expectancy at the time was about 55, and that crying was considered treason, Murgatroyd represented the repression and uncertainty of the age. The first TV fitness gurus arrived in the US in the ’50s. They had exciting names like Jack LaLanne and Debbie Drake, while their bodies bulged and curved like Googie sculptures. Meanwhile in the UK we had Eileen Fowler, who promised that women could “stay young forever” so long as they did plenty of bouncing. Fowler was symbolic of a country rediscovering its confidence after a decade of rationing and loss of international prestige. The next big thing in fitness came in the ’80s with the advent of the celebrity home workout video from people like Jane Fonda. They sweated power, money and confidence, and sold you a dream: that you too could be a rich, famous actress with a mansion. In the UK, we were more realistic in our choice of idols. Instead of Jane Fonda, we had Angela Lansbury – the voice of the teapot in Beauty and the Beast – whose video Positive Moves claimed that “there’s something to like in every body”. Clearly, Lansbury had not seen many British people with their clothes off, which is just as it should be. Then in the ’90s the UK finally got a fitness guru we could be proud of: Mr Motivator. Real name Derrick Evans, Mr Motivator wore colourful spandex onesies and shouted at us during breakfast television. Sure, we were too busy stuffing our faces with Frosties and Pop Tarts to actually exercise, but Mr Motivator made us feel like we were getting healthy. And, as the ’90s proved, feeling that something is good (Britpop, New Labour) is almost the same as it actually being good. The 2000s brought a darker aspect to fitness. Now it wasn’t enough to get healthy – you had to get really unhealthy first. So celebrities would eat and drink themselves to the brink of destruction, spend three months starving and exercising, and then release a fitness DVD in time for Christmas. This yo-yo approach was emblematic of a decade in which confidence and paranoia took equal turns at the helm. We are a world power! (So let’s invade Iraq) We’re total idiots! (Goodbye Northern Rock). Needless to say Jade Goody – who was on Big Brother in 2002, launched her own perfume in 2004, was kicked off Celebrity Big Brother for racist bullying in 2007, and died tragically of cancer in 2009 – had her own fitness DVD. Today we’ve reached the era of Instagram and Joe Wicks, where fitness isn’t about being fit anymore. Instead, your abs are an essential fashion accessory, part of your brand. We have “wellness goals” and exercise programmes with militaristic names like XTFMAX, P90X and FOCUS T25. Your body is a fleshy enemy that must be vanquished by the forces of vanity. As the world disintegrates around us we retreat into the security of knowing we have a really nice arse.

07

The Beginning: <1000 Club

The community outreach of Grimalkin Records

The <1000 club was formed to champion smaller artists who deserve better from streaming platforms, both in terms of play count and genuine industry support. Spotify, Apple, Bandcamp and Soundcloud all have a responsibility to the artists that keep their platforms afloat, and only one of those are currently meeting the moment in a meaningful way. This month’s entry highlights not just the duty that streaming platforms have to support artists, but the responsibility that labels have to support their communities. Grimalkin Records is a queer arts collective that centres mutual aid, community outreach and education as its core values. The label was founded on the idea of bringing greater inclusivity to the industry. It uses its releases to fund QTBIPOC civil rights organisations and grassroots social justice movements worldwide. It was founded by Nancy Grim Kells (AKA Spartan Jet-Plex), who was inspired while volunteering for mutual aid organisations like the Virginia anti-violence project. “There is a lot of overlap between community organising, mutual aid and music in Richmond,” they say during our chat. “Since we’ve grown, we’re releasing a lot of people that are outside of our circle. Music is a bridge to community support, mutual aid. That’s really where our centre is.” Grimalkin is non-traditional in its lack of a hierarchal structure. Its members are all involved in core decisions for the label. There’s an openness and transparency around finances that is rare. The decision to be so forthcoming with potentially sensitive information came from Grim’s own experiences as an artist. “I’ve worked with a label before and I was completely in the dark,” they say. “I didn’t know how much money my album made, and I didn’t get any money. That’s kind of the norm. “I had no idea what I was doing when I started. I’ve been using the skills I’ve got as a Special Ed teacher for fourteen years and a guidance councillor for seven years.” One of the recent decisions made as a collective has been to stream digitally as a label, with a view towards greater outreach, accessibility and exposure. Before, artists were given the funds by Grimalkin to stream on their own terms, rather than Grimalkin “taking a piece of nothing,” as Grim puts it. Since forming several years ago as a passion project, the collective has blossomed in the past two years into a full-time

08

venture, spurred on by incredible releases like Backxwash’s industrial hip-hop opus God has nothing to do with it leave him out of it, which earned international acclaim and amassed a large, unexpected fanbase. The label is now home to a varied roster of noise rock, twee electro-pop and club bangers. Upcoming releases include Òrfãs, a new hypnagogic punk album from the Brazilian duo A/C Repair School, and As a Motherfucker, a sleek and expansive collection of R&B songs from Quinton Barnes. The two also have plans to work together on a project, despite the different musical worlds they operate in, which underlines the collective’s focus on collaboration and communal support. As with the rest of Grimalkin, the thing that ties all of it together is a shared ethos of emphasising BIPOC and queer perspectives, as well as ethical distribution. “We all hope that Grimalkin will be an example for other labels,” Grim says. “Get to know what’s going on in your community. Find out who is involved in mutual aid. Build relationships beyond ‘this music is cool’. I think you need to get to know people and make sure your values align.” Right now, the collective is in the process of applying for a $2,500 business grant that will allow them to establish the educational resources that have long been part of their ambitions. Despite growing public exposure, the collective hardly makes enough to break even, in part because they refuse to take a large cut of streaming royalties. “I thought I was going to retire at the company I worked for,” Grim says, referring to their career as a councillor. “It was a huge blow to me when I got laid off. I went to a very dark place that I hadn’t gone to since I was probably in my twenties. I was devastated. But I had Grimalkin still, and after a few days I did what I normally do and picked myself up again. I just poured it all into Grimalkin. Now I think that’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me. I’m a work-horse kind of person.” Despite the stress and the financial struggle, Grimalkin has doubled their sales in a year. Their 2021 calendar is stacked with releases, without sacrificing their initial goal of community outreach. “Maybe this is not a pipedream,” Grim says.

words by skye butchard. illustration by kate prior

Out Now NILS FRAHM ‘Tripping With Nils Frahm’

HERE LIES MAN ‘Ritual Divination’

TALA VALA ‘Modern Hysteric’

A legendary artist at a legendary location: Tripping with Nils Frahm captures one of the world’s most sought-after live acts performing at one of Berlin’s most iconic buildings.

The guitars are heavier and more blues based than before, but the ancient rhythmic formula of the clave remains a constant.

Tala Vala combine experimental recording methods bridging marginalised genres, synths, brass and strings, jagged guitars and primal percussion. .

CASSANDRA JENKINS ‘An Overview On Phenomenal Nature’

GUIDED BY VOICES ‘Styles We Paid For’

Erased Tapes LP/CD

Ba Da Bing! LP/ LP Ltd /CD

If Phenomenal Nature has a unifying theme, it’s the power of presence, the joy of walking in a world in constant flux and opening oneself to change. (From Purple Mountains; Craig Finn; Lola Kirke collaborator)

Riding Easy LP/ LP Ltd / CD

GBV Inc LP/CD

Styles We Paid For stands as a testament to this Year In Isolation, reflecting these dark days through Robert Pollard’s prism, with the band sounding as confident and authoritative as ever.

Number Witch LP

KID CONGO & THE PINK MONKEY BIRDS ‘Swing From The Sean DeLear’ In The Red LP/CD

In such uncertain times, one thing is most certain—Kid Congo & The Pink Monkey Birds will always bring the party ...and the other world.

Dutchess Records LP/CD

The discovery and musical re-imagining of Mirabel Lomer – an artist’s unheard world which is emerging from the shadows into the light.

M.CAYE CASTAGNETTO ‘Leap Second’ Castle Face LP/CD

Peru-born artists debut album defies description but in parts feels like a forgotten incredible 70s folk album.

Coming Soon

BELL ORCHESTRE ‘House Music’ Erased Tapes LP/CD

THE FALL ‘Live at St. Helens Technical College ‘81’ Castle Face LP + 7”

MIRRY ‘Mirry’

PAINTED SHRINES ‘Heaven & Holy’

MICHAEL PRICE ‘Eternal Beauty OST’

WARRINGTON-RUNCORN NEW TOWN DEVELOPMENT PLAN ‘ Interim Report, March 1979’

RICHARD NORRIS ‘Music For Soundtracks Vol: 1’

Woodsist LP / CD

Dutchess LP

Inner Mind LP/CD

Castles In Space LP

info@fortedistribution.co.uk

The Beginning: Sweet 16

Julien Baker never wanted to be Homecoming Queen and the other kids knew it

It was such a wild time for me. There was a lot going on. I had just come out to my friends. I remember I had short hair before I came out to my parents and I was like, “how did you not know?” I had moved in with my dad, as well. My mom and I were in a fight about something non-related to my sexuality. I was being a vindictive, mean little kid. I was like, “Well, I’m gay,” and my mom immediately without skipping a beat retorts: “I know.” I thought I had been doing such a good job! I was playing in the band The Star Killers [later known as Forrister]. We played every show offered to us. We’d play two house shows a weekend for three or four straight weekends. I quit my part-time job at Country and Western Steakhouse because we were supposed to play a show with a band called Joyce Manor, who I was obsessed with. If you threw a dart at all the moments in that year of my life, there’s such a high probability that I’m just standing in some random person’s living room watching a band or playing a show. That’s where I felt most at home. All my friends were there. Instead of going to the mall, that’s where we congregated. When we weren’t playing music we’d be hanging out at Taco Bell or the Waffle House. I actually went to school out of town (Memphis). I would go out to this quasi-rural farming community to go to high school where the culture was a lot more hicky, but not in a derogatory

10

way. I didn’t like school. I felt like I was always in trouble, but looking back I guess I wasn’t in that bad of trouble. Around then I ended up in a weird situation of being Homecoming Queen of my high school – I had a bright red mohawk at the time. One of the people in my class nominated me to make fun of me. I didn’t know what to do. I guess I was like, “haha funny.” Like, I was actually kind of pissed and really self conscious about it. It’s just classic: queer girl doesn’t know how to assimilate into, like, straight feminine normalcy trope. But that’s what I felt like, you know? I mean, there’s a photo of me where everyone’s wearing the straight up ball gowns, like for a pageant. And I didn’t get the memo on it. So I’m just wearing a day dress, which is already wild for me. Shoes I got from Goodwill. I mean, it sucks, because I feel like that’s exactly the thing that gets made into the manic sexy dream girl trope – this ‘she’s quirky and weird’… but I was actually so uncomfortable. It was really uncomfortable to be around a lot of people who knew how to act in a certain environment that I was completely foreign to. It’s just so inconsistent with my personality, or the things that I value. The homecoming reception was on a weekend, and then my band was releasing a record we’d recorded in our friend’s attic the following day. So there was me, playing in this church basement venue screaming at a whole bunch of house show kids and wearing the homecoming queen sash. Ridiculous. I also got in a car crash around this time. I was driving this old school Honda Accord that got absolutely smashed to death. I was fiddling with the consoles where all my mix CDs were. Like my Manchester Orchestra, Colour Revolt and whatever Christian adjacent indie rock I was listening to. I just didn’t look at the road like an idiot 16-year-old and drove straight into one of those giant concrete street lamps, and it collapsed onto my car. The pictures are wild because the entire hood of the car is caved in. But I didn’t get hurt at all. Zero injuries – and the car was entirely crumbled. It was crazy. I was leaving evening church. The first person that got there was my dad and he just like sprinted up to the car. I was just sitting inside and shocked. Its weird to talk about for many reasons, but then everybody stopped church to have a prayer circle until an ambulance came and made sure I was okay. I was going through old memorabilia from this time and I’m looking at this heinously tacky belt buckle that says ‘music = life’. And it did. It was everything. It’s like a self fulfilling prophecy when you discover music as a child, and then you latch on to it being the only thing that matters. Earlier than this age, I wanted to learn every instrument so bad that I used to sit and arrange little towels on my desk in the spaces approximately where I thought a rack tom, floor tom, a snare, and a hi hat would go, and try to mine play along to Fall Out Boy or whatever. I just thought about music.

as told to greg cochrane

Final Third:

11

Berwyn

A young talent almost lost to immigration papers, by Tara Joshi. Photography by Frank Fieber 12

“I clung onto religious belief because otherwise who are you gonna believe in? Men? It was men that was letting me down, men that was making the decisions that had me in my position, so how could I put faith in that?” When Berwyn Du Bois picks up the phone, he skips over the hello part, launching straight into the warm joviality and loud belly laughs that brim over through most of the conversation. But in the midst of talking about things like the easiness of dancing alone to R&B in front of the mirror, every now and again he will offer something slow and plaintive that recalls the searing insight of his music. A multi-instrumentalist, rapper and singer-songwriter born on the Caribbean island of Trinidad before moving to Romford, east London, aged 9, much of Berwyn’s life in England has been marked by precarity. The “men making decisions” were the home office, with his mother being sent in and out of jail while he found himself in a recurring state of homelessness, all because they didn’t have the right immigration papers. But, against all odds, he came out of 2020 with an acclaimed mixtape under his belt, a Drake co-sign and a coveted spot on the BBC Sound of 2021 longlist. “None of what is happening [with my career] makes any sense,” he laughs with exuberance. “I don’t think I’m special, but this shit makes no fucking sense!” Contrary to what he might say, DEMOTAPE/VEGA is in fact a very special listen. The story goes that Berwyn made the project in his bedsit over the course of a fortnight – a final shot at seeing what he could make happen with his music in the UK (if it didn’t happen he would go back to Trinidad). It’s a significantly more accomplished tape than that hasty roll of the dice backstory might suggest, marrying hymnal sonics with the leftfield, echoey end of rap and soul, all while speaking candidly of his personal history, using gilded vocals that wax and wane between spoken word and song; intimate rasps and silken runs to convey romance and grief, relationships and the realities of how he and his peers were getting by (“don’t let them catch you with the knife, don’t let them catch you without it”).

“With my immigration situation, I felt much futility in school,” he says. “I didn’t want to stay there, it didn’t feel like there was much point in my being there. So I picked music GCSE because I figured at least I wouldn’t have to try for no reason in that one lesson.” And so, he had initially gone about his music lessons with the attitude that he could “not give a fuck”. His teacher was “the best guitarist in the world, but the worst teacher in the world – one of them ones,” he laughs. But then, after said teacher was fired for showing students The Human Centipede (obviously), teacher Di Russell joined and saw the potential in Berwyn. “Up until that point, the ‘options’ I thought I had [with my immigration status] were nothing to do with school,” he says, “But she put the time in and made me see I did have options.” Nurturing his talent, Russell would take Berwyn and his classmate James to a folk club every Wednesday night, thus keeping at least one evening a week free from the potential trouble from those “other options”. The three of them began

— Folking Young — Music, of course, had always been a big part of Berwyn’s life. In Trinidad much of the calendar year revolves around carnival and devotion to music and, at several points, Berwyn sings sweet soca and parang songs down the phone. His father, who had previously been a DJ, made him have steel pan lessons as a kid (“there are worse things to be forced to do!”), and it was through his parents that he also came to respect everything from Motown to soul to Mika. When he arrived in the UK, he quickly began to forge his own taste too, watching the music channels on his auntie’s TV, namechecking Mario, Ne-Yo and those golden era Ja Rule and Ashanti tracks as moments that led him to start writing his own songs.

13

“With my immigration situation, I felt much futility in school. It didn’t feel like there was much point in my being there”

performing under the band name “Folking Young”, with Du Bois singing, as well as playing guitar and cajón. On other evenings after school, he was allowed to stay behind playing around with the music department’s singular Mac computer, with the caretaker checking in on him every couple of hours. Although Berwyn still felt the underlying sense of futility about his future in the country, aware he wouldn’t be able to go into further education, he ended up studying music at college “for the love of it”. And while his friends disappeared to university, even self-releasing the tape he had put together in those two weeks was starting to seem impossible given his situation. But in the midst of it all, he managed to stay afloat. “You have to have hope, that’s so important in any situation in life,” he says. “I was raised in a very religious household, so that gave me the upper edge to look up at the stars. Nowadays it’s more things like affirmations that keep me going. Maybe it’s just psychological, but maybe it is angels or something? I do have faith in my dad – I don’t think he’ll ever let me down. But I also know the extent of his ability. So it’s nice to put faith in something else…” — Glory — It was as if by cosmic or divine intervention that everything suddenly fell into place. XL Recordings behemoth Richard Russell heard his music and brought him on board for the second album in his collaborative Everything Is Recorded project (“a beautiful community!”). Berwyn signed with Columbia and, in June, he gave a stunning performance from home for Later… with Jools Holland, adding a harrowing new verse to his track ‘Glory’ with lines like “Lately I’ve been thinking a lot / How come cos I’ve never been shot my pain doesn’t count?”. “It was a really weird space and time with my internal problems as well as everything that was going on externally,” he says of that performance, which came in the midst of the resurgence of global Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd. “I asked for two weeks to write something, because I wanted to let the dust settle – you can’t predict that level of entropy, you know? There’s nothing I can say on that. But there had been some miscommunication and I found out the show was actually in like a day or two. So then I just decided to speak from my own story. And writing it was painful, but if I had been trying to write something with everybody’s weight on my shoulders I would have just given up. So I just said, ‘I’m gonna do this for the weight on my shoulders – it’s heavy enough.’” In writing for himself, Berwyn’s work has still resonated with plenty of people. “There’s a girl who’s getting her cancer

14

scan today,” he says, “and she’s been in touch with me through the treatment, because my music helped her get through. You know, I made those songs in two weeks, I was in no way expecting them to get on radio or for them to have this amount of reach! It fills me with a great sense of responsibility because the world is crazy, but I really have a chance to be, like, a little superhero or something? It’s intimidating knowing that every step I make is so crucial in terms of the ripple effect it might have on the kids who feel influenced by me.” Though he is potentially interested in entering the more political sphere one day, for now he is dubious of the greater awareness and objection people seem to have of the hostile environment and government immigration. “I think I preferred it when people weren’t talking about it,” he says. “Out of sight, out of mind. In my music, I can talk about it on my own terms, because ultimately for all we might think things are changing because of what we see in our little Instagram bubbles, I know from experience that’s not what the majority believes. Otherwise Brexit wouldn’t have happened, and I wouldn’t get plenty of other indicators when I leave my house on a daily basis.” For now, then, the focus remains on his artistry. “I made VEGA a long time ago, when I was so far from knowing myself,” he says, before laughing. “I’m a much better producer now! The music I’m working on right now is a lot more ambitious, I’m working with a few different sounds – for example some R&B polish. But I like making things my own, I like being a little inventor making little rearrangements to try make a more advanced product.” He’s also hoping to put Trini sounds back on the map, he says, explaining that he is tired of the global assumption of Caribbean culture being solely wrapped up in Jamaican output. “There are such beautiful moments in soca,” he exclaims, “if I could just hone in on that. I would love to spend a year in Trinidad and build up an infrastructure with lawyers and labels and producers so that we could pave the way for the next global soca wave to take over. But that’s my little side job.” Berwyn Du Bois might not believe in men, but maybe that doesn’t matter. He has faith in something else that has kept him going through it all.

THE BEST NEW MUSIC

WHITNEY K TWO YEARS

Maple Death Records

Rolling through life, an open mind like an ocean, an infinite ride that comes furiously crashing to a halt. Whitney K’s ‘Two Years’, a deep dive into the Yukon songwriter’s journey where outsider folk becomes political poetry, life in motion delivered through a freeway ridden baritone voice that transforms the mundane into extraordinary.

ANNA B SAVAGE A COMMON TURN City Slang

The stunning debut album from Anna B Savage. “An outstanding first impression… A voyage of selfdiscovery and wanking” 8/10 - Loud and Quiet “Savage clears a groundbreaking path... the young songwriter reveals a bright future at the end of personal agony” - Uncut “Promises to be one of next year’s most impressive debuts” - GoldFlakePaint

V/A - SEX: TOO FAST TO LIVE TOO YOUNG TO DIE

V/A INDABA IS

’Distractions’ available on indie stores only limited blue vinyl and CD.

On their debut LP ‘Dream Harder’, Hello Cosmos want to shake humanity out of the comatose, fearful and isolated world it currently lives-in and dare to dream of a new and utopian one that awaits tomorrow. Fusing sound and vision, art and activism, multimedia and technology; ‘Dream Harder’ encourages people to use technology and not be used by it.

First time ever on vinyl, the legendary compilation taken from the infamous Kings Road SEX shop jukebox. Curated by Marco Pirroni of Adam & the Ants and SEX shop regular, a hand-selected treasure trove of underground/outsider classics – all of which were on heavy rotation throughout the mid-‘70s on Malcolm and Vivienne’s SEX boutique jukebox.

Brownswood are delighted to share this hotly anticipated “unofficial” follow up to ‘We Out Here’ and ‘Sunny Side Up’ which respectively showcased music from London and Melbourne. This time they turn their attention to the vital scene in South Africa, one of many effervescent movements erupting around the world. Specially created recordings featuring some of most exciting post rock, avant-garde and improvised music emerging from Johannesburg’s scene.

BRIJEAN FEELINGS

JOHN CARPENTER LOST THEMES III

BLANCK MASS IN FERNEAUX

TINDERSTICKS DISTRACTIONS

HELLO COSMOS DREAM HARDER

City Slang

Cosmic Glue

’Distractions’ is an album of subtle realignments and connections from a restless and intuitive band: where every detail earns its place. Upholding a career-long commitment to interior exploration - the sound of a band ever ready to stretch themselves.

Sacred Bones Records

Ghostly International

Influenced by Latin and Brazilian psych-pop and tropicalia, Oakland’s Brijean make rhythmic, dreamy dance music for the mind, body, and soul. ‘Feelings’ finds Brijean Murphy trusting in her strengths, collaborating with producer Doug Stuart and friends including Chaz Bear (Tory y Moi). The album cultivates a specific vibe, a softness Murphy has come to call “romancing the psyche.”

On legendary director and composer John Carpenter’s first solo album in five years, his “soundtrack for the movies in your mind” is more vivid than ever. Collaborating with son Cody Carpenter and godson Daniel Davies, the trio builds richly rendered worlds with guitar and synthesizer.

Stranger Than Paradise Records

Includes The Count Five, The Castaways, Flamin’ Groovies, The Troggs, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, The Sonics, The Creation, and many more.

Sacred Bones Records

Using an archive of field recordings from a decade of global travels, the new Blanck Mass record is divided into two long-form journeys that gather the memories of being with now-distant others through the composition of a nostalgic travelogue.

Support Your Local Independent Retailer www.republicofmusic.com

Brownswood

A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN INVISIBLE CITIES Artificial Pinearch Manufacturing

A Winged Victory For The Sullen, the collaboration between Stars of the Lid founder Adam Wiltzie and L.A. composer Dustin O’Halloran, are set to release new album ‘Invisible Cities’, the stunning score to the critically acclaimed theatre production directed by London Olympics ceremony video designer Leo Warner. The music was written for the MIF theatre production, which was loosely inspired by INVISIBLE CITIES by Italo Calvino.

Lucy Gooch An ambient musician takes it to the movies, by Ian Roebuck Photography by Richard Luxton

16

“I feel like I go from one place to another trying to shut the world out, even more so nowadays.” In a bid to shake off the all-toofamiliar Zoom fatigue, Lucy Gooch is explaining her curious double life. “Forgive me, I have cases of word vomit on calls like this and anxiety spirals but at the moment I work at night all the time and I need to get out of the habit.” It doesn’t take long for Lucy to realise that burning both ends of the candle is unavoidable right now. “Society tells us that we must be up at 8am and back to bed at 10pm,” she says, “but I have a day job and it’s a battle to avoid the two worlds clashing. I think a lot of people talk about this don’t they – the need to wait until the world shuts down before they can create.” She gesticulates as she throws speech marks around the word ‘create’. She’s expressive and more engaging in video calls than she lets on. The double life she refers to will be familiar to many other struggling musicians – artistry by night and a 9-to-5 to pay the bills. “It’s not a nice feeling, being duplicitous and not being authentic,” she says. “I don’t talk about what I do at work and it would be really nice to not have that feeling. My head’s always elsewhere and I think a lot of people have that struggle. You have to accept work where you can get it if you’re a musician.” Lucy’s frankness is refreshing as she balances an admin job at Bristol University with her light-footed, ambient music. Ever since her dreamlike EP Rushing came out over 12 months ago she’s been capturing imaginations with an evolving, multilayered approach to her moonlight-made music. Now signed to Fire Records, and with a new body of work set for imminent release, Lucy is ready to emerge from her night-time daze into the light once more. “This time I have moved away from loopbased tracks and it’s more about songwriting and twists and turns whilst keeping that ambient space. When someone like Fire Records gives you confidence in what you’re doing you’re able to lean into it more. I am really grateful that people are listening. It’s made me pursue what I want to do, which is be more of a songwriter.” — Powell and Pressburger — Surrounded by an ethereal fog, the new material is astonishing in its density. With echoes of Kate Bush and the Cocteau Twins, and driven by her remarkable, choral-like vocal, it’s somehow extremely dramatic but elegantly understated at once – not surprising when you consider her schooling. “I’m from a theatre background,” she tells me. “I studied theatre and visual arts but I never really went for it. I liked making puppets, painting and singing, and a lot of folk, but I never embraced making music until 2015. Then I bought an electric guitar and it changed everything. The next step was some loop pedals and that was the beginning of the songwriting journey for me.” This time around Lucy has looked to influences close to home. “All of the new songs are based on a series of films by Powell and Pressburger that have always stayed in my mind,” she says. “Black Narcissus and A Matter of Life & Death. There is so much passion in those films and they are very big and colourful. I saw them when I was a kid and I kept coming back to them through my teenage years. They really focus on women and repression and those themes

are important to my music, so I used them as a vehicle to write with and in turn have made a bigger sound.” Full of visual strangeness, you can identify Powell and Pressburger’s presence within Lucy’s music, but there’s something else that lingers long after consuming both, and that’s the impact of landscape. Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus is a Himalayan technicolour dream, just as the soaring sound of the fresh tracks from Lucy are influenced by her surroundings. “Yes,” she says. “I think this music feels full of colour. There are more neons and brighter colours. Rushing was more ambient and pastels with an earthy iciness to it. I have always been quite isolated and close to my environment. Growing up in North Norfolk, I really liked my space, although I wasn’t doing any whimsical traipsing around fields or anything! Or maybe there was a bit of that.” She laughs. “I guess it just gets into your music, doesn’t it. I was imagining aerial photography and even nature documentary programmes, plus the feeling of flying over an amazing landscape, that’s something that we all have as human beings. It’s pretty stereotypical for ambient music isn’t it.” She laughs again. — Orinoco Flow — The pastoral element of the music resonates more as you tune in to Lucy’s unique vocal. “From about the age of seven I was in a youth choir and it was run by a very scary woman that I was terrified of. She’d get mad and her eyes would go really wide so everyone would take a deep breath. She would make us sing religious songs but also more experimental music too, like maybe Native American music; it was a little bit ‘Orinoco Flow’ – she was inspiring but scary!” What’s interesting realising this is how Lucy has harnessed this memory and applied it to her work, layering vocal track over vocal track to re-create the church experience. “I think I just love the act of singing together and I always felt like I was free. A group of people singing is an amazingly powerful sound. I was never picked out as an individual, they didn’t know I existed and because music is so elitist and I am not classically trained it’s just a way of doing my own version of it, which I can be in control of.” Before we say our goodbyes, I ask Lucy about going back to performing once the pandemic is over and her feeling of duplicity returns. “It does scare me,” she admits, “because I care about it so much. When you see a gig and it sounds exactly like it does on the record, that can be underwhelming, but when someone tries to do their own version of a song, that can also be disappointing, so you can’t win! That is my anxiety – do I try and emulate the record mathematically and accurately or do I do something looser? My conclusion is I just need to be true to myself and it took me a long time to get there last year; the minute I try to be someone else it goes wrong. It got to the point at the end of 2019 where I had been hating my day job and I told myself you have to start enjoying gigs, this is your time now. I started to love it and it was a totally different experience. It was funny that just as I started to enjoy playing live everything shut down, so I am hoping that I will be able to hold on to that memory of being in the moment.”

17

BackRoad Gee

18

We’ve gotta go through the struggle with a smiley face, by Joe Goggins. Photography by Sophie Barloc

Beyond repeating the same, single word, BackRoad Gee is cagey on what’s in his diary for 2021. It’s perhaps understandable: with the pandemic having upended the music world, he finds himself in a position different to that faced by artists who had major ambitions for last year, many of whom were stuck in a kind of purgatory, best-laid plans put on hold, and then torn up. Gee, on the other hand, went ahead and released his latest EP – the explosive, seven-track Mukta vs Mukta – and watched it meet with rave reviews, as some critics suggested that he seemed to be rearranging the very fabric of grime. He then went on to work with a real hero of his, Burna Boy, after the Nigerian reached out to him personally, something he still sounds as if he’s having trouble believing (the proof is in the pudding, though, in a thumping rework of WizKid’s ‘Ginger’ that the pair put together). As the year has turned, he’s watched as his close friend and collaborator Pa Salieu come out on top of the BBC’s Sound of 2021 poll. And yet, in a country still ravaged by coronavirus, it’s hard to see too far ahead. Which is why he keeps his forecast brief. “Greatness, man,” is the verdict as he lights his second joint of our Zoom call. “Greatness.” That’s precisely what he’s had in mind for himself ever since he began to take the prospect of a career in music seriously; he’s cleaved closely to a vision that places artistic success higher in importance than its commercial counterpart. “From the beginning, the whole time I’ve been coming up, I’ve always said we had a plan. I’ve stuck to it, and I’m executing it. I just feel like I’m ticking things off as I go.” To begin with, though, Gee had to be talked into thinking big. Growing up across London – moving between Tottenham, East Finchley, Stratford and more besides – his early musical aspirations were not something he readily shared: incidentally, the same is true of his real name. He was born to Congolese parents and exposed to the music of their homeland in his early years; before rap was even on his radar, he had aspirations of becoming a drummer in order to recreate the rhythms that floated through his childhood homes. By the time he discovered hip hop – the same way any British teenager of his generation would have, through records like 50 Cent’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’ and DMX’s Year of the Dog… Again – it was only one of a number of stylistic doors that were open to him. UK garage was speaking to him, too, as was afrobeat, and when he started to experiment with making music of his own – throwing together these disparate ideas and cooking up something genuinely new – he kept it to himself. “It was my friends who saw the potential in me,” he recalls. “I was just doing it for my own enjoyment until other people told me I could do something with it. They got me together with my manager and it’s just skyrocketed from there. And now, here I am, with you.”

19

Gee’s stage name is taken, as he tells it, from a dislike of “operating on the main road”, something you could take any number of different ways. Musically speaking, it fits with the sonic blueprint he’s mapped out over the course of a still-fledgling career that’s taken in Mukta Wit Reason, an 18-track compilation that he insists is not a mixtape, as well as Mukta vs Mukta. If the main road would have been to pursue grime – and it could easily have been, he says, as he reels off a list of genre royalty that his uncles exposed him to, including D Double E, Ghetts, Giggs and Dot Rotten – then the back road is the route Gee has taken. Mukta Wit Reason marked him out as a drill rapper, although the indelible impression of early grime was palpable, particularly in the way he flowed: his bars were a kind of East London staccato, with a pace and bite that laid the groundwork for him to crossover into collaborating with the likes of JME and Lethal Bizzle on last November’s ‘Enough Is Enough’. It’s tracks like that that have really had aficionados sitting up and taking notice; it’s not often somebody comes along and breaks grime’s mould to fit his own purpose, which is precisely what Gee seems to be doing in blending it with drill so effortlessly. “The thing I keep stressing to people is that I can’t be boxed in,” he explains. “You’re never going to get one type of sound from me; you’re probably going to get every type of genre. It’ll always have the same soul, but anything else about the sound could change.” Despite this, though, he agrees with

20

the view that he has subverted grime for his own musical ends. “They were right about that: that’s what man did. I fabricated my own thing. That was the goal when I sat down with the producer; combine everything. Let’s make it garagey, let’s make it afrobeat-ish, let’s make it…” He pauses. “Backroad-ish, you know? And people picked up on that, and I’m very appreciative of it. It’s a good reflection on the work.” — Sonic bloodletting — One thing Gee knows for sure about 2021 is that he’ll drop his debut mixtape proper, tentatively titled Summer ina Da Winter. It will, he promises, be a departure from the highenergy chaos of Mukta vs Mukta. That EP was born out of his desire to knuckle down and take his career seriously after a stint in prison towards the end of 2019; the specifics are not something he’ll readily go into, but they seem to have initiated a change in mindset that is likely to manifest itself on the mixtape, with Mukta vs Mukta representing a kind of sonic bloodletting. “Those are some very personal songs. I was in a dark place when that was coming out, but it was a good place for the music. A lot of people doubted the kid, and didn’t think I could do this, and get to where we are. But we did it, man. There was definitely a split personality thing going on. The songs were hectic; it was like they were all fighting against each other. I don’t know if it was a reflection of my mindset at the time. It might just be down

“From the beginning, the whole time I’ve been coming up, I’ve always said we had a plan. I’ve stuck to it, and I’m executing it” 21

to the fact that they were all bangers, crazy tracks – they make you want to jump, or dance, or whatever.” When it does arrive, Summer ina Da Winter will represent a shifting of gears (he dislikes the term ‘change of pace’), both in terms of the medium and the message. Details are still thin on the ground, and Gee’s manager interjects to keep him from providing a rundown of the record’s producers and features; he’ll only say that it’ll involve “a lot of different people from different sides.” There is an obvious restlessness in him when it comes to exploring different avenues, though, and possibly even a nagging sense that he’s already over the comparisons with contemporaries in the grime scene. “That’ll always be there,” he says, “but I’m not just going to stay with that sound. I have an idea of what people expect from me now, and I’m still catering to my people, but I want to open their minds to other things, too. It’s a whole different approach now.” That could be down, in part, to the importance of his work with both Burna Boy – who he confirms will appear on Summer ina Da Winter – and Pa Salieu. In closely meshing his own music with collaborators both alike and apart in terms of style, he’s both flirting with the mainstream and making good on his talk of the mixtape representing the next stage of his creative journey. He remains stunned that Burna Boy sought him out; the significance of working with such a figurehead of what might prove to be a golden age of afrobeat and dancehall hasn’t been lost on Gee. “He came to London, reached out to my people, and then I was talking to him, and quickly we were in the studio. I didn’t know what to expect – usually, when I go into the booth, I know myself, and I know how I want things to sound: I know what I’m doing. And I can’t lie, bro: it was very, very organic. We just went in and came out with some crazy stuff. God works in mysterious ways.” That particular pairing might have seemed like an unlikely hook-up; Gee’s relationship with Pa Salieu, on the other hand, seems like an obvious confluence. The two men are cut from the same cloth; Brits in their mid-twenties who retain strong connections to their African heritage, both of whom seem hellbent on reinventing this country’s rap language. Salieu’s signing to Warner, constant rotation on 1xtra and his Sound of 2021

22

triumph will open him up – and by turn Gee too – to a whole new audience, but the latter talks only of their deep kinship, sounding almost choked up in the process. “Some things are not explainable. That’s my guy, man. I think, in life, everybody has somebody that their energy just bounces off, and that’s who he is to me. He’s my brother, you know? I love that boy with my heart.” With Gee featuring so prominently on ‘My Family’, one of Salieu’s biggest hits, and with Salieu having made a telling contribution to Gee’s own breakthrough, the incendiary ‘Party Popper’, we can expect the pair to play a crucial part in each other’s stories as the year unfolds, even as Gee strives to lay down his own marker with Summer ina Da Winter. There will be more unknowns to face down the road – the road itself being one of them, with the pandemic having seen to it that Gee’s experience of performing live remains limited. “It’s a weird feeling,” he says. “It’s not as if I’ve missed it, because I haven’t really done that on a big stage yet. I would love to get on that, but obviously corona has mashed it all up for now.” When the prospect is raised of what the energy might be like when he finally does find himself up in front of packed rooms, he grins. “Outrageous! It’s gonna be outrageous.” Until COVID-19 eases and lockdowns are consigned to history, though, the central theme of Summer ina Da Winter will remain a timely one; a far cry from the manner in which Mukta vs. Mukta pitted him so relentlessly against himself and his own demons, the core message from the mixtape is one of positivity, and standing tall in the face of adversity. “Light out of darkness – that’s the feel. Rising above the hardship, and still having a good time. We’ve gotta go through the struggle with a smiley face, bro.”

A monthly record club from Loud And Quiet and Totnes record store DRIFT 12 new LPs with 10% off for L&Q Members in February’s collection

Find this month's collection at driftrecords.com/loud-and-quiet

Committee meeting, by Jess Wrigglesworth Photography by Tom Porter

Blue Bendy A couple of weeks before Christmas Blue Bendy did something which has become rather unusual these days: they played an actual, real life show, to a real life audience, albeit one seated in a socially-distanced formation. “It felt a bit like a school recital, but in quite a nice way,” says synth player Olivia Morgan of the gig at Brixton’s Windmill. I recall the first time I saw Blue Bendy, a performance which felt like anything but – frontman Arthur Nolan meandering around his five bandmates as they vied for space on a makeshift stage, playing to a very rowdy crowd at New Cross’ now defunct Five Bells. A seated audience must have been quite a contrast. “I mean, we felt quite nervous about it for a couple of reasons,” Nolan admits. “I was thinking about how it would translate, if it was going to be awkward, but it was actually alright. Something about it kind of suited us, I think.” It seems that the band has come a long way since those early show. Formed in 2017 by Nolan and guitarist/synth player Joe Nash shortly after both had moved to London from Scunthorpe (“I was just sort of making some music on my own and Joe had heard them. He approached me and said, ‘You’re amazing, can I start a band with you?’ and I said, ‘Yeah fine.’”), the band was initially completed by bassist Sam Wilson, Harrison Charles on guitar, and Oscar Tebbit on drums. “We asked [Oscar] to join because he could ride a motorbike and we thought that’d be a good idea. It’s good for posing with,” Nolan deadpans. It wasn’t until they’d been gigging for almost a year that Morgan joined the group, bringing with her another synthesiser and softlyuttered vocals that serve as the perfect counterpart to Nolan’s Lincolnshire drawl – think Laetitia Sadier meeting Mark E. Smith. “Since Olivia joined, it feels like we’ve been trying to make something weirder, and poppier,” says Nash. Their first show as a six-piece was in June 2018, although Morgan was yet to learn all the parts. “I’d only been playing for a week or something, so I was kind of fake playing on stage,” she laughs. “No one knew.” More gigs followed, including coveted support slots with Squid, The Magic Gang, Scalping and Omni, which won them plenty of new fans, including Franz Ferdinand frontman Alex Kapranos, who approached them backstage after the Omni show. “We came offstage and he was just there talking

24

to us,” says Nolan. Do they keep in touch? “I think we sent him a meme,” quips Morgan. “We have a bit of back and forth with him on Instagram,” says Nash, “he’s a part-time commenter on our posts.” Surely enough, when a picture of the band crops up on my feed that evening, Kapranos has commented: “Great photo!”. The band are planning on sending him their new music once it’s done, and they share a collaborator – the producer Margo Broom, who has worked with Goat Girl and Fat White Family, and at whose Hermitage Studios Blue Bendy have been spending increasing amounts of time. Broom comes up a lot over the course of our chat, and it’s clear that access to her and her studios has had a major impact in developing the band’s sound. “She heard ‘Suspension’ and wanted to get us in,” Nolan recalls. “I guess she liked it to some degree and thought she could do a better job, basically.” Broom seems to be a kind of mentor and, at times, a seventh member. “I don’t think [she] would like me saying this, but we’re often sort of all over the shoulder, keeping an eye on what she’s doing. They say not to make certain things part of a committee, but it’s quite a lot of give and take, I think.” — Slay your darlings —

Making things happen genuinely by committee, in a band of six, is no mean feat, but it is clear that each member has a real say in every aspect of Blue Bendy. “It’s democratic, isn’t it?” Charles says, as the others appropriately nod. “I think when there’s six of you, you’ve gotta realise – and it’s taken a while – that sometimes less is more. And you’ve just got to strip everything back.” “I mean, we all have the same end goal,” says Nash, adding that having Hermitage Studios at their disposal has helped the group dynamic. “Before, you’d be in like a pressure cooker of a three-hour studio that you’re renting for £15 an hour. And everybody wants their part at the end of the day, and you’re trying to argue for it but also trying to think about it fitting into the song. We’re much better at it now, but in the past there have been times where you had to either stand your ground and stake your claim, or just think, ‘This isn’t worth it’ and accept the change.” “There’s a lot of slaying of darlings isn’t there?” posits Nolan. “There’s a lot of slaying of dreadful songs as well,” replies Charles, much to the others’ amusement. Even watching them interact over Zoom, it’s obvious how well and how easily they get along. It must help that they all have a similar taste in music, although when I ask about their shared reference points they seem reluctant to name names. “I suppose we’re all Aphex Twin fans, or Radiohead fans,” Nolan offers. “If you can make the argument of something having any sort of musical merit, then I think that’s probably something that we’re all into,” adds Nash. A press release lists Arthur Russell, Boards of Canada, Tindersticks and Broadcast among their influences, but

25

ultimately, Charles says, their musical references don’t feed into their output in a literal sense. “I guess it doesn’t really come into the creative process, does it? I mean, maybe there’s a couple of touchstones but mainly it’s about serving the general idea of whatever Arthur brings in. I think we’re all just kind of trying individually with our own instrument to serve that song as best we can.” So far it seems to have worked as a tactic. While there are certainly echoes of those other bands in the four tracks Blue Bendy have currently released, they’ve established a sound all of their own – a hypnotic mesh of grungey guitars and whimsical Stereolab-esque pop brought down to earth by Nolan’s impassioned vocals, his delivery oscillating between curt spoken word and a melancholic croon undeniably indebted to Morrissey. Recent singles ‘International’ and ‘Glosso Babel’, the first products of their work with Broom, suggest they’re only getting better. “Those are probably the most collaborative songs we’ve done,” Nolan says of the tracks, which came together in Broom’s studios early last year, and which they self-released on Nash’s label Simonie Records. “The label was something I’ve wanted to do for a while,” he says. “We had these tracks finished and we wanted to get them out there, we just didn’t have anyone to put them out because everybody sort of went cold with coronavirus – that’s a strange choice of words, but everybody that we were speaking to sort of dropped off.” Aside from being ghosted by record labels, the tumult of the pandemic hasn’t had too detrimental an impact on

26

“I wanted to basically come out of lockdown a new band – to feel like we’re taking it up a notch”

their music. “I was kind of worried, you know, especially around sort of April time, thinking maybe it’s gonna go off the boil,” Nolan admits, “but from July onwards, it kind of feels like everyone – I mean, I don’t wanna speak for everyone, but it feels like everyone’s a lot more up for it at the minute, weirdly more than even before, I think.” Not having the time constraints and pressures of continually playing shows, Nash says it’s been liberating. “You think, ‘Well there’s nothing else to do. And we have this space available to us. Let’s get it all done. Let’s write loads more, and let’s record loads more than we’d normally have the time to do.’” “I wanted to basically come out of it a new band,” says Nolan. “Lots more things recorded, nearly a completely different setlist – to feel like we’re taking it up a notch. And I think that’s kind of what we’re achieving, I think we are much tighter, I think we’re better musically than we were before. We’ve never felt more cohesive. I certainly haven’t felt as happy with everything as a whole as I do now.”

Post-industrial malaise and French-language sprechgesang, by Luke Cartledge. Photography by Will Shields

Gary, Indiana Between 1960 and 2010, the population of Gary, Indiana shrank by half. Today, despite the housing crisis 40km away in Chicago, it’s strewn with abandoned buildings, unwanted, untouched. Few groups are capturing the sound of such deterioration and malaise quite like a band from Manchester called Gary, Indiana. At the time of writing, they’ve only got three singles out (the self-released ‘Berlin’ and ‘Pashto’, and ‘Nike of Samothrace’, with which they announced their signing to Brooklyn’s Fire Talk Records) but they’ve made an impact. Combining caustic noise with thunderous percussion and flickering sprechgesang vocals, the trio’s music doesn’t simply capture the surface aesthetics of post-industrial decay but expresses how it feels to live in a society that feeds, vulture-like, on that decay. This stuff is pressurised, disorientated, battered, occasionally beautiful, often gruelling. And really good. We speak just before Christmas 2020, the UK still deep in its Covid-19 crisis. Gary, Indiana’s Parisian singer Valentine Caulfield is facing up to spending the holidays in Manchester. “I’m not going home for Christmas for the first time in my

28

entire life,” she says, sadly. “It’s been really stressful and quite weird. But [lockdown] has been quite productive for us.” Caulfield first met her bandmate Scott Fair in 2016, when they were both playing in other bands. They were impressed with one another; slowly, what would become Gary, Indiana began to formulate. “It started out just as me and Val writing together,” says Fair. “And we were lying in wait, until we were happy that we’d arrived at a place musically that we were excited to share with people. A lot of the early stuff was just figuring out a way to get to that place. We met at a gig in a place called Aatma, just off Stevenson Square in the Northern Quarter.” “We kept in touch,” says Caulfield, “and when Scott was starting what is now Gary, Indiana he messaged me saying that he wanted a female vocalist who could speak French. I happen to be a female vocalist, and I speak French. We then spent quite a while refining what our songs actually are. It’s been a slow, interesting sonic journey.” It sometimes feels like Manchester itself has been on a slow, interesting sonic journey in recent years. For many of the

city’s rock bands at least, the shadow of Oasis, Stone Roses and Factory Records seems inescapable; for every innovator plugging away at something new in a Fallowfield basement, there are countless revivalist outfits. But there has been progress. “Yeah, I don’t think the Oasis-worshipping sort of indie rock band in Manchester is ever gonna go away,” says Fair. “But now I think it’s much easier for people to engage with stuff that isn’t that. I’m really pleased with the way that people have started to embrace live music more, because of the collapse of the record industry. It’s great to see that people are willing to come out to smaller shows, buy a record, buy a t-shirt, whatever. It did feel like that went away for a while. Covid couldn’t have come at a worse time really. “Up until the pandemic, the scene was very healthy,” he expands. “There’s a lot of people putting on their own shows, a lot of really good small promoters, and in the surrounding boroughs and towns there’s a lot of good stuff happening.” Fair’s words are spoken tentatively and anxiously, with reason. As the pandemic continues to suspend the music industry in limbo, the infrastructure that underpins DIY culture has never looked more vulnerable. In July, two of Manchester’s iconic small venues, the Deaf Institute and Gorilla, announced their permanent closure. To widespread relief, they were bought by new owners soon afterwards, securing their futures (for now). As ever with city-centre property developments though, there’s more to this story than meets the eye, as Caulfield is keen to point out. “The thing is, they’ve been trying to sell it for ages. I’m not gonna go into a whole rant about them, but the people who run it own half of Manchester. They were clever to announce it just as lockdown was being lifted as being a consequence of Covid and everything, but they had been trying to unload Deaf Institute and Gorilla for ages.” — Absolute filth — They’re an interesting pair in conversation. Fair is friendly and forthcoming, but chooses his words very carefully; Caulfield speaks less, but when she does, she’s a little sharper, happier to cut through the niceties with a pointed observation. That’s not unlike the role she plays on record – her vocals are used sparingly, with an unusual regard for timbre and rhythm taking precedent over clarity or catchiness. She’s not pushed to the front of the mix like a conventional pop frontperson; somehow, that commands one’s attention more acutely. “I’ve done many different things,” she tells me of her vocal style. “I started with classical music, music school for 15 years, then I played in rock and punk bands. And I think the sound that we have at the moment takes from different sides of all of the things that I’ve done before. What I enjoy the most about playing in this band is that I get to do all of the things that I really enjoy. But yeah, it’s in-between singing and spoken word, some of it’s full-on shouting; I do a lot of heavy breathing. It’s quite exciting.” Fair agrees. “I was really drawn to Val’s voice when I saw her perform. Certainly, from a Brit’s perspective, French language sounds very musical and poetic, and there’s something

about juxtaposing the prettiness of that with very challenging noise music.” He’s not wrong: recent single ‘Nike of Samothrace’ sounds like Big Black wrestling with Einstürzende Neubaten, until Caulfield’s voice, artfully deadpan and distant, provides a completely unexpected focal point. “I’d love to sing or perform in another language,” Fair continues, “because then for an English-speaking person, it’s less about lyrics and more about the sound of the voice and the sound of syllables and pronunciation. One thing that I really love that Val does is playing a lot with the rhythm of her voice, in parts where you might not have so much dynamism with pitch.” Caulfield laughs. “I always really like people telling me that the French makes everything sound so nice – it allows me to speak absolute filth.” — Ten-foot film nerds — As the project began to take shape pre-pandemic, record releases and live shows beckoned, and the pair decided they needed a drummer. “I started talking to this guy at a party,” says Fair. “We were talking about music all night; we liked a lot of the same obscure bands. I was like, ‘You seem like a well-connected guy. Do you know any good drummers?’” He did, and introduced them to Liam Stewart, Lonelady’s touring drummer. He’s not able to join us today, so Fair takes the opportunity to sing his praises. “Liam wasn’t the first. There were others. But we played Liam the demo, and the first time that we met him, at the end of that session, I was just like, ‘Oh, man, we need to play with this guy’. Because he’s really good.” Their lineup thus complete, Gary, Indiana have big plans for their live show, whenever we’ll be allowed to see it. Selfconfessed film nerd Fair lights up when describing the visual ideas they’ve been working with. “It’s all self-produced – the videos, the artwork, the music. And there’s this VR set: Liam was like, ‘Right, I can get a 360-degree camera, let’s set it up with some lights in the rehearsal space and see how it looks.’ It’s all in black and white, and then it’s like you’re in the middle of our circle of play. We noticed after we’d filmed it that we were all very close to the camera, and we look like giants. I remember showing it to my friend and he’s just like, ‘As intimidating as the music is, the fact that you guys are probably ten feet tall makes it even more intense.’” “Visual media has a big influence on us,” affirms Caulfield. “I did a lot of opera when I was young – I like the theatrical element of it.” We wrap up soon, and return to our respective lockdown Christmases. For the next few days I have ‘Nike of Samothrace’ on repeat. The way it channels the claustrophobia and unknowability of life at the moment seems appropriate. It increasingly feels like this band, named after a city whose time has long passed, may have arrived perfectly at theirs.

29

Karima Walker

Between sleep and wake, folk and drone, by Sam Walton Photography by Holly Hall

30

Karima Walker is not a morning person. She admits this to me at 9am Arizona time, squinting into a webcam with breakfast coffee steaming at her side and early light streaming into the room behind her. Dusk, meanwhile, encroaches around me, seven hours and five thousand miles east. “I love it when I’m up early,” she starts to explain from her Tucson studio space, before correcting herself: “Actually, I love it when it’s early and I’m already awake. But I do not like waking – waking is a regular struggle for me. I could probably sleep for days if I didn’t have anything I needed to do. My natural rhythm is to stay up late and wake up late, even though I really wish I could be there for morning.” Perhaps, then, crack of dawn isn’t the ideal time to be talking to Walker, whose own comfort zone – not to mention that of her new album of delicate folk songs intertwined with fragile, burbling tape loops – seems far more rooted in the small hours. Then again, maybe it is: after all, said new record evokes that woozy period of coming round after deep sleep, not yet fully alert but nonetheless hazily aware of one’s surroundings, with its title, Waking The Dreaming Body, signposting that evocation directly. Across its 40 minutes, it addresses that headspace both head on (in its quietly pastoral title track, Walker, breathy and quiet as if only just stirring, sings that “it seems like every morning starts the same way”) and also more obliquely: across large swathes of drone and field recordings, the strange internal logic of the hypnagogic brain is transferred into peaceful abstract sounds that, when assembled, feel like the aural equivalent of huge Rothko canvases: simultaneously edgeless and depthless and still, their meticulously-planned giant form residing beyond the realms of waking intelligibility, but only just. At their most impressive, as on a 13-minute album centrepiece that swoops elegantly from beatific synth surges into dense thickets of reed sounds and out into distant piano and environmental recordings of howling wind, the pieces are restorative and calming, sedate but teeming with life. However, it’s when Walker combines these two forms – swaddling the warm orthodoxy of American folk music in noise and ambient texture, or using non-standard production techniques to subvert otherwise standard songs – that her music is at its most compelling. It’s an approach she first acknowledged while at college in the Midwest around the time of that region’s mid-noughties boom in what was initially called “alt-country”, essentially a retooling of traditional folk and country music with post-rock and experimental approaches. Walker recalls the excitement she felt after hearing Wilco’s A Ghost Is Born while in school, (in)famous for its penultimate migraine-mimicking epic drone piece ‘Less Than You Think’, and talks admiringly of the skewed attitudes adopted by records from around the same time like Master And Everyone by Bonnie “Prince” Billy and Jolie Holland’s Catalpa. “They were the people reinterpreting that tradition, but their trajectory away from it made a lot of sense to me,” she recalls. It’s a trajectory that Walker has followed too. Where some musicians rely on strict compartmentalising of multiple styles, Walker’s preference is for the combinatorial approach. “The model of artists who will put all the lyrical songs on one side and then the instrumental pieces separate is something I like,” she