PUBLISHED BY: Traveling Blender, LLC. 10036 Saxet Boerne, TX 78006

PUBLISHER: Louis Doucette louis@travelingblender.com

BUSINESS MANAGER: Vicki Schroder vicki@travelingblender.com

GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Jennifer Nelson jennifer@travelingblender.com

ADVERTISING SALES: AUSTIN: Sandy Weatherford sandy@travelingblender.com

SAN ANTONIO: Gerry Lair gerrylair@yahoo.com

For more information on advertising in San Antonio Medicine, Call Traveling Blender at 210.410.0014 in San Antonio and 512.385.4663 in Austin.

San Antonio Medicine is the official publication of Bexar County Medical Society (BCMS). All expressions of opinions and statements of supposed facts are published on the authority of the writer, and cannot be regarded as expressing the views of BCMS. Advertisements do not imply sponsorship of or endorsement by BCMS

EDITORIAL CORRESPONDENCE: Bexar County Medical Society 4334 N Loop 1604 W, Ste. 200 San Antonio, TX 78249

Email: editor@bcms.org

MAGAZINE ADDRESS CHANGES: Call (210) 301-4391 or Email: membership@bcms.org

SUBSCRIPTION RATES: $30 per year or $4 per individual issue

ADVERTISING CORRESPONDENCE: Louis Doucette, President Traveling Blender, LLC.

A Publication Management Firm 10036 Saxet, Boerne, TX 78006 www.travelingblender.com

For advertising rates and information Call (210) 410-0014

Email: louis@travelingblender.com

SAN ANTONIO MEDICINE is published by SmithPrint, Inc. (Publisher) on behalf of the Bexar County Medical Society (BCMS). Reproduction in any manner in whole or part is prohibited without the express written consent of Bexar County Medical Society. Material contained herein does not necessarily reflect the opinion of BCMS, its members, or its staff. SAN ANTONIO MEDICINE the Publisher and BCMS reserves the right to edit all material for clarity and space and assumes no responsibility for accuracy, errors or omissions. San Antonio Medicine does not knowingly accept false or misleading advertisements or editorial nor does the Publisher or BCMS assume responsibility should such advertising or editorial appear. Articles and photos are welcome and may be submitted to our office to be used subject to the discretion and review of the Publisher and BCMS. All real estate advertising is subject to the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1968, which makes it illegal to advertise “any preference limitation or discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status or national origin, or an intention to make such preference limitation or discrimination.

SmithPrint, Inc. is a family-owned and operated San Antonio-based printing and publishing company that has been in business since 1995. We are specialists in turn-key operations and offer our clients a wide variety of capabilities to ensure their projects are printed and delivered on schedule while consistently exceeding their quality expectations. We bring this work ethic and commitment to customers along with our personal service and attention to our clients’ printing and marketing needs to San Antonio Medicine magazine with each issue.

Copyright © 2025 SmithPrint, Inc. PRINTED IN THE USA

John Shepherd, MD, President

Lyssa Ochoa, MD, Vice President

Jennifer R. Rushton, MD, President-Elect

Lubna Naeem, MD, Treasurer

Lauren Tarbox, MD, Secretary

Ezequiel “Zeke” Silva, III, MD, Immediate Past President

Woodson “Scott” Jones, Member

John Lim, MD, Member

Sumeru “Sam” G. Mehta, MD, Member

M. “Hamed” Reza Mizani, MD, Member

Priti Mody-Bailey, MD, Member

Dan Powell, MD, Member

Saqib Z. Syed, MD, Member

Nancy Vacca, MD, Member

Col Joseph J. Hudak, MD, MMAS, Military Representative

Jayesh Shah, MD, TMA Board of Trustees Representative

John Pham, DO, UIW Medical School Representative

Robert Leverence, MD, UT Health Medical School Representative

Cynthia Cantu, DO, UT Health Medical School Representative

Lori Kels, MD, UIW Medical School Representative

Ronald Rodriguez, MD, UT Health Medical School Representative

Alice Gong, MD, Board of Ethics Representative

Melody Newsom, BCMS CEO/Executive Director

George F. “Rick” Evans, Jr., General Counsel

BCMS SENIOR STAFF

Melody Newsom, CEO/Executive Director

Yvonne Nino, Controller

Al Ortiz, Chief Information Officer

Brissa Vela, Chief Membership and Development Officer

Jacob Hernandez, Advocacy and Public Health

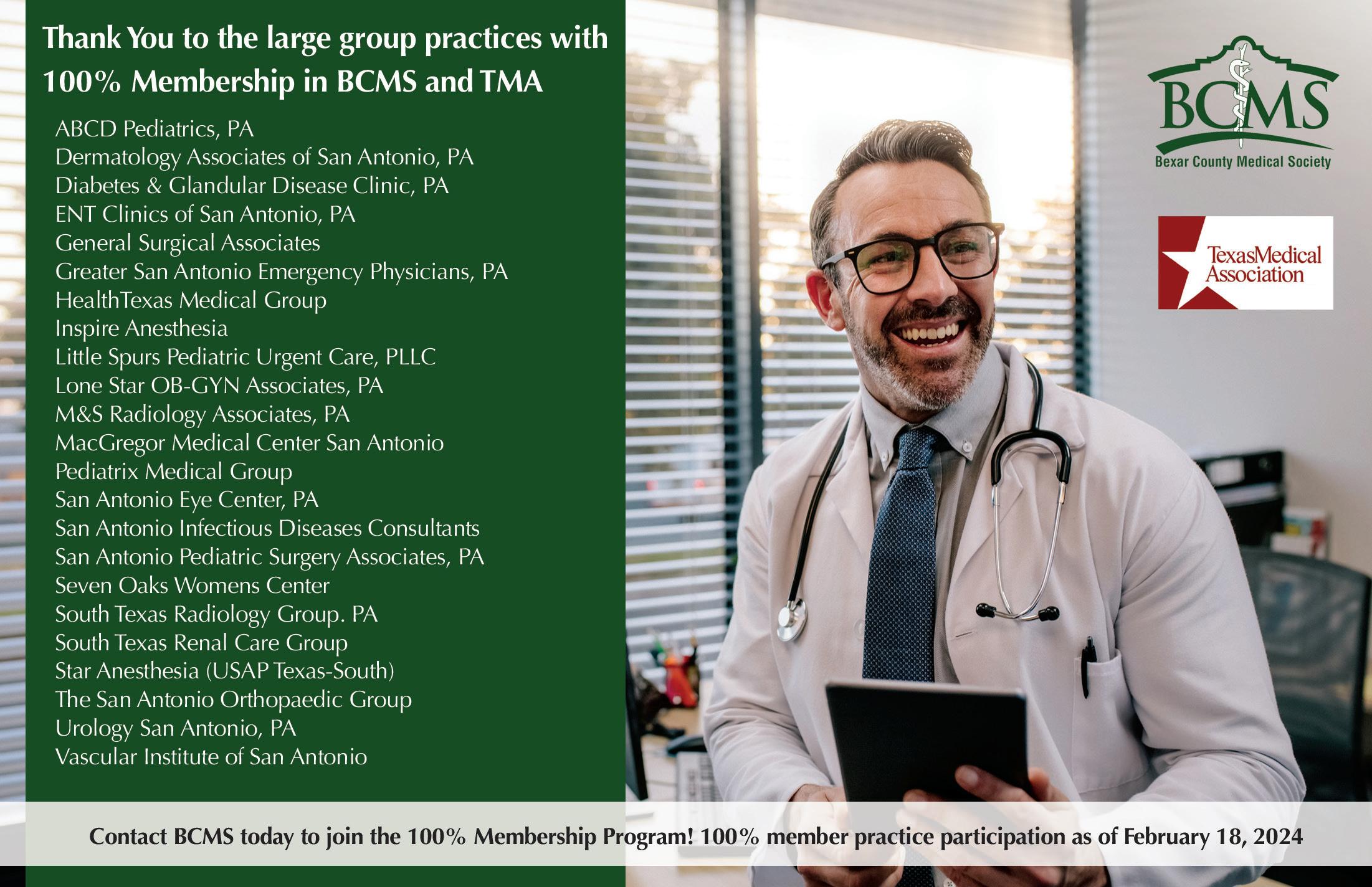

Phil Hornbeak, Auto Program Director

Betty Fernandez, BCVI Director

Jennifer C. Seger MD, Chair

Timothy C. Hlavinka, MD, Member

John Robert Holcomb, MD, Member

Soma S. S. Jyothula, MD, Member

George-Thomas Martin Pugh, MD, Member

Adam Ratner, MD, Member

John Joseph Seidenfeld, MD, Member

Amith Skandhan, MD, Member

Francis Vu Tran, MD, Member

Subhashini Valavalkar, MD, Member

Louis Doucette, Consultant

Brissa Vela, Staff Liaison

Gabriella Bradberry, Staff Liaison

Trisha Doucette, Editor

Ayomide Akinsooto, Student

Elizabeth Allen, Volunteer

Rita Espinoza, DrPH, Volunteer

David Schulz, Volunteer

Ramaswamy Sharma, MS, PhD, Volunteer

By John Shepherd, MD, President, Bexar County Medical Society

One of the things I really love about traveling is randomly wandering the streets of a new place, discovering what it has to offer. Durian fruit in the markets of Vietnam — rated zero stars — do not recommend. A beer made from the Calafate berries in South America — five stars — highly recommend. Giant bugs on a stick in Bangkok — can’t give you a recommendation because I just couldn’t do it. Then there are the people, the children, the performers. Have you ever seen the guy on the street corner with the tip jar along with a harmonica, drums, symbols and an accordion or guitar? He starts on one instrument, adds a little vocal lyric, attempts to blow the harmonica around his neck while using his foot to activate a pedal to bang the drum. It’s impressive, isn’t it, for all the things he tries to make work on his own … that one-man band.

As physicians we often pride ourselves on our individual skills and achievement, and rightly so. We’ve all dedicated years to education, training and honing our expertise to provide the best care possible. However, while being a “one-man band” may seem admirable, it also has its limitations. No matter how skilled a physician is in their specialty or how committed they are to advocacy, no single practitioner can address the multitude of needs within the practice of medicine. Just as the performance of a one-man band pales in comparison to the richness of a symphony, a single physician is far less effective advocating for the needs of our profession than the collective strength of the medical community, particularly when united through organizations like the Bexar County Medical Society and the Texas Medical Association.

For many of us, the simple practice of medicine isn’t quite as simple as it used to be. We now grapple with pre-authorization hassles, narrow insurance networks and a landscape of increasing regulations coupled with declining reimbursement rates. There are the constant challenges to scope of practice with everyone wanting to do what physicians do but without the education, training and certifications we have. Not to mention, attacks on established science and fundamental public health principles. It’s no surprise that these pressures add stress for all of us and contribute to high levels of physician burnout with close to 400 physicians choosing to take their lives each year … a rate significantly higher than the general population. How do we combat this? Together … We do it together.

As physicians, we hold the doctor-patient relationship sacred, working hard to maintain it, protecting it at all costs. To protect this and other facets of medicine, we need to worry about another relationship … the legislative relationship. Our elected officials control so much about medicine: Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates; graduate medical education funding; and maintaining boundaries on the scope of practice. It’s essential that we develop the type of relationships with them so that WE become the trusted voice when they have questions about how to best serve Texas patients and how to best serve

Texas medicine. Make no mistake about it, there are other groups in their offices telling them their truths and wants: independent practice and prescribing without physician oversight for nurse practitioners; direct access for physical therapists without any examination by an orthopedist or other physician; and test and treat for pharmacies. If they are not hearing OUR voices, they are listening to someone else’s.

I ask you to join me in amplifying medicine’s voice at the Capitol. Serve on the legislative committee, attend a fundraiser, volunteer for a campaign, thank a legislator for doing something in your community, and show up at First Tuesdays. Seeing the white coat invasion at the Capitol is a sight that makes you proud to be part of Texas Medicine. If you don’t do anything else, let your checkbook do the work by becoming a TEXPAC member. Electing candidates who have open ears and open minds to the needs of medicine is half the battle.

When I look at our membership, I see so many community leaders, physicians, Alliance members, medical students and mentors — each of you choosing to be engaged with the Bexar County Medical Society because you support organized medicine. I believe you want what I want … the best not only for physicians but the best for our patients and communities we serve. Our diverse specialties and perspectives strengthen us, creating a robust organization, but we have the potential to become even stronger and more influential. By inviting someone you know to join the Society or the Alliance, you amplify our impact. It may sound cliche, but there is undeniable truth in saying “strength in numbers.” A strong Society enables us to protect the integrity of the practice of medicine. A strong Alliance allows us to expand our reach as they put outreach programs in our community and work to make strong bonds with state, county and local leaders in the name of medicine. Think about it. How will you help us grow? Who will you ask to enhance our collective voice?

To all of you, thank you for being a member of the Bexar County Medical Society or the Alliance. I know you have a choice about where to spend your time, your efforts and your finances. I thank you for choosing medicine and I thank you for trusting in me to lead Bexar County medicine forward this year as your president.

John Shepherd, MD, 2025 President of the Bexar County Medical Society, has been an active lobbyist for the Family of Medicine at the Texas State Capital and has held several “Party of Medicine” events, introducing physicians on how to get involved with legislation that affects medical issues. He has been Chief of Surgery at Christus Santa Rosa Children’s Hospital, a past member of the Board of Directors of Tejas Anesthesia, and currently serves on the BCMS Legislative Committee. Dr. Shepherd served as Secretary on the BCMS Board of Directors for 2023.

Our Alliance welcomes members to an amazing opportunity to celebrate our special bond of medical family friendship, and highlight the value of our social and professional connections. We strike a balance between purposeful, mission-driven community service like our award-winning Period Poverty Project; legislative advocacy like our support of First Tuesdays at the State Capital; and fun, membership bonding events like our Pink Out! Fall Luncheon. Join us and BE THE FAMILY OF MEDICINE!

Victoria Kohler-Webb BCMSA Immediate Past President

Bexar County Medical Society Alliance 2025 Steering Committee

JENNY SHEPHERD Acting President

VICTORIA KOHLER-WEBB Immediate Past President

DANIELLE HENKES

KATRINA THEIS

NEHA SHAH

MARTHA VIJJESWARAPU

While the world, and medicine, may both look a bit different from our inception 108 years ago when we knitted, sewed, and made bandages for the WWI soldiers … we are still the same at heart. We are advocates, innovators, fundraisers, community ambassadors, relationship builders, support systems. We are difference makers.

Jenny

Shepherd

BCMSA Acting President, and TMAA President

For information on the Bexar County Medical Society Alliance, scan the code.

By Susan C. Mengden, PhD, CEDS-C, with Noel Ales, DO

Eating disorders are a group of mental illnesses resulting in significant medical comorbidities. The type of foods and how they are consumed by patients leads to physical consequences directly correlating with the patient’s mental health. The interdependency of physical and mental manifestations of these disorders has led to the American Psychiatric Association guidelines for a multidisciplinary treatment team. This mandated team includes physicians, dieticians and mental health specialists: both psychiatrists and eating disorder certified therapists.

Eating disorders are difficult to detect both medically and psychologically. Cultural norms, personal bias and lack of eating disorder training have led to these disorders being overlooked or misdiagnosed. The four main diagnoses for eating disorders are anorexia nervosa with subtypes - restricting type or binge-eating/purging type, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder (BED), and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Atypical anorexia is a person in a larger body who has the thoughts and behaviors of anorexia even though their body doesn’t represent emaciation. Clinically, these disorders overlap. They

each include restrictive intake behaviors, or excessive or obsessive movement or avoidance of movement. An eating disorder cannot be diagnosed based on appearance. Any of the eating disorders may present with any body size. It is important to note that these diagnoses are based on behaviors, not BMI or weight.

The prevalence of eating disorders has increased over the past decade and particularly during the COVID-19 quarantine. Diets, exercise, weight-loss regimes and medications became daily social media, wellness and healthcare discussions. The diet industry and messages to diet for “health” or “wellness” have normalized restrictive eating behaviors. “Eating in balance” is no longer recommended in health classes or physician offices. Society correlates a person’s weight status with their health status. Weight loss medications are often overprescribed or misused by patients with undisclosed eating disorders. Up to 30 percent of patients seeking weight loss medications have an underlying eating disorder. The recent overwhelming influx of new and more effective weight loss medications is resulting in the exacerbation of eating disorders.

Physicians are often primary in the diagnosis of an eating disorder. It is imperative that all providers have a heightened awareness of the nuances of eating disorders to make a timely diagnosis. Open lines of communication between mental health providers and a patient’s primary care physician should become routine. This would enhance clinical outcomes in all patients with psychological and medical diagnoses as both providers could collaborate care and information leading to a unified diagnosis. In addition to the multitude of medical complications from eating disorders such as cardiac insufficiency, liver, kidney and bone disease, the mental health consequences of eating disorders are the most impactful and devastating. Common co-occurring disorders include obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder. Anorexic and bulimic patients are 7-18 times more likely to COMPLETE suicide. All eating disorder patients are 33 percent more likely to have suicidality. These patients are deeply suffering.

Each eating disorder has specific characteristics. Anorexic patients typically have underlying thoughts and emotions based on the irritational fear about becoming fat or unhealthy. In bulimia, the underlying thoughts and emotions are about maintaining one’s current body size with restricting behaviors, then bingeing followed by compensatory behaviors of purging. The person believes that purging behaviors maintain their body size. The abrupt cessation of purging without treatment results in undereating to avoid feeling full. Fullness is the trigger for purging behaviors. In BED, the underlying thoughts and emotions are striving for weight loss with restrictive behaviors. The consequential physical hunger leads to overconsumption and intense anxiety over what was ingested. They cope with this anxiety by binge-eating. ARFID patients have underlying thoughts and emotions about the textures, smells or taste of foods. They may present with a sudden onset of traumatic weight loss, often secondary to a choking experience or heightened anxiety from traumatic experiences such as a death or accident.

Physicians should note that the thoughts and emotions underlying eating disordered behaviors are illogical, reactive and impulsive. Eating disorders are progressive and the thoughts that might have been rational initially such as: “I want to get in shape” or “lower my cholesterol” often worsen and lead to physically unhealthy behaviors of eating and movement. Before telling the thin patient that they look “healthy,” complimenting their new exercise plan for 2025, or remarking that another’s hypertension would improve with weight loss, take a moment to ask everyone about their eating patterns. Most eating disorder patients are secretive or ashamed. They are not likely to disclose their eating disordered behaviors. They will take your advice and walk out the door to binge, purge, restrict and overeat until the only thing they think about is food and their reactions to it.

The thoughts and obsessions of an eating disorder are all consuming for these patients. They may present to the primary care clinic making comments about the scale “being off,” wanting to lose weight to “be healthy,” or concerned about being “too thin” in the case of the patient with ARFID. It is important to hear their cues and ask the right questions. Ask your patients how they are eating rather than assuming what their diet consists of based on their weight. Never suggest that someone restrict whole food groups for weight loss. Patients of all body types often present with their eating disorder stating that they have been informed by a physician to lose weight without further guidance. A clinical interview assessing the thoughts and emotions behind the food, eating and exercise habits is what is recommended. When interviewing patients, listen for eating disorder clues: are they making weight and diet comments? Is there a family history (eating disorders are highly heritable)? Is there early osteoporosis in their mother, grandmother and great aunts? Don’t forget a social history. An eating disorder brings control to a chaotic or traumatic life.

Changing one’s eating behaviors is NOT about willpower or intellectual ability. An eating disorder is NOT an addiction. An eating disorder is complex and all aspects must be addressed for a patient to recover. In addition to the multidisciplinary approach, the specific, third wave of Cognitive Behavioral Therapies (CBT) have been researched to be effective for eating disorders. These evidence-based CBT therapies are techniques to move eating disordered thoughts from being ego-syntonic to ego-dystonic. These therapies are used in conjunction with specific nutritional guidelines and therapies under the medical guidance of a physician to bring complete healing and recovery to this special population of patients. Treatment is successful when a person learns to use new coping skills and coping behaviors for emotions and thoughts that are more effective than coping with food and movement behaviors.

Susan C. Mengden, PhD, Certified Eating Disorder Specialistiaedp Approved Consultant, and the Founder and Executive Director of Esperanza Eating Disorders Center, has over 35 years of clinical experience specializing in eating disorder treatment.

By Chasley Fortune-Pittman, MDS, RD, LD, and Sara Hamilton, PsyD

Studies show that 28.8 million Americans will have an eating disorder in their lifetime.1 Eating disorders are a complex set of behaviors, cognitions, emotions and physical conditions affecting people of all sizes, ages, genders and ethnicities. They can develop from a combination of factors including genetics, access to food, physiological conditions, mental health conditions, physical attributes, malnutrition, eating patterns/behaviors, cultural norms, stressors and interpersonal relationships. Due to this complexity, it is necessary to incorporate a variety of health professionals to best treat eating disorders.

Diagnosing Eating Disorders

Due to their complexity, it can require multiple assessments and observations over time for a healthcare team to identify and diagnose eating disorders. Many assume that eating disorders are easy to identify based on weight or size, but only around 6 percent of people with an eating disorder are medically underweight.2 Many adolescents and adults at normal body weight engage in disordered eating. Contrary to stereotypes, many of those at low body weight binge eat and many of those at a high body weight undereat.

Medical providers and mental health professionals can diagnose eating disorders. Eating disorders generally involve distress and/or significant negative consequences related to the types, amounts, qualities or impact of food consumed. They can involve overeating, undereating, and/or eating only limited types of foods. Some eating disorders involve concerns about body weight, shape and/or size, but not all.

There is no definitive answer to how long it may take to treat eating disorders. Treatment of eating disorders should be individualized based on the status of health, nutrition, mental health, behaviors of concern and the specific cultural needs of the patient. Settings for eating disorder treatment include (in descending order of structure): inpatient, residential, partial hospitalization, intensive outpatient and outpatient levels of care. Treatment of eating disorders focuses on medical stabilization, psychotherapy (individual, group and/or family), nutritional stabilization and education. When medically stable, treatment focuses on helping the individual and their family to build up skills and routines to treat the disordered

thoughts and behaviors, address the factors contributing to the disordered behaviors, and to help reduce risk of relapse.

Communication and teamwork ensure both the safety and effectiveness of treatment. Below are some examples of how various health professionals collaborate in the treatment of eating disorders.

The multiple evaluations done by physicians are crucial in determining the appropriate treatment for those with eating disorders; those with more physiological consequences stemming from their behaviors will need higher levels of care. Eating disorders affect many of the body’s systems and patients may not be insightful into nor forthcoming about their habits and their effects. It is important to conduct a comprehensive review of medical history, observe changes to weight or growth charts, order laboratory and diagnostic testing, and complete a thorough physical examination.3 Though questions related to dietary status and behaviors may not be as in-depth as from a registered dietitian, physicians may also review overall eating habits, food intake frequency and compensatory behaviors such as laxative and diuretic use, medication abuse or misuse, questionable supplement use, excessive exercise or purging behaviors. Substance abuse can correlate with those who have eating disorders and should also be properly assessed.

Physicians may struggle to identify eating disorders in those who appear to be following their recommended plans or whose symptoms overlap with other medical conditions. They may unintentionally further someone’s restriction and overexercising by encouraging them to lose more weight or mistake purging behaviors as food sensitivities or a consequence of severe reflux. Physicians can screen for disordered eating using the following validated screening tools listed below under references.

Laboratory testing is helpful for determining a proper diagnosis, level of risk and priorities for effective treatment plans. Testing should involve an evaluation of blood sugar levels, electrolyte levels, a comprehensive metabolic panel to gauge liver and kidney function as well as nutritional and immunity status, urinalysis for hydration and signs of food restriction, and electrocardiogram to determine irregularities and risks to the heart.

Physicians should use their evaluations to ensure both medical stability and make proper recommendations for level of care. Early detection helps prevent chronic, severe disease as well as promote faster recoveries.

Registered Dietitians:

Registered Dietitians focus on the nutritional status of the individual. To do this they must look at related health findings (labs, weight history, medications, etc.), assess calorie and macronutrient intake, vitamin/mineral supplementation, inspect eating patterns, and observe attitudes and behaviors around food. In addition, dietitians also take care to assess dieting history and probe to find more about compensatory behaviors, such as abuse or use of weight loss medications, extreme diets, fasting, induced vomiting, over-exercising or food restriction. Due to the nature of chaotic eating patterns or even the patient’s choice to not be forthcoming with information, dietitians must ask multiple questions in order to get an idea of the “big picture” of the client’s nutritional health and habits.

Dietitians are also a key component in the creation of interventions and the monitoring and evaluation of the patient’s treatment. The interventions created involve decreasing pathological behaviors, restoring patient to a healthy weight, encourage adherence to medical recommendations, and improve nutritional intake. Dietary education as well as motivational interviewing and counseling are essential to not only encourage the patient’s adherence to recommendations but also build habit changes to sustain results and prevent relapse.

Psychotherapy for eating disorders typically includes the patient and their families to best address the multitude of factors that contribute to the development of an eating disorder and to support the patient in their recovery. Treatment of eating disorders often focuses on helping clients to improve their ability to identify, manage, and communicate their emotions, to improve their functioning in their relationships, and to change thought patterns that are contributing to their distress related to eating. By addressing these factors, clients are better able to manage their distress related to eating and can then implement the needed dietary interventions more effectively.

There are multiple therapists that can play roles in the treatment of eating disorders. Speech therapists address chewing and swallowing issues that can cause fear of eating, particularly after a choking incident. Occupational therapists help strengthen abilities to do daily activities. Physical therapists help encourage safe movement that takes into account the patient’s barriers.

Nurses:

Nurses play a pivotal role in the gathering of information used for diagnosing and therefore deciding on effective treatment. They also monitor improvement in symptoms and provide valuable coaching to

clients on how to understand the ways in which their behaviors are impacting their physical health. Nurses often obtain clients’ weight information, which can be a very stressful part of treatment for many clients; compassionate nursing care helps many to tolerate this part of treatment more effectively.

Psychiatrists:

Eating disorders are often co-occurring with other mental health issues like anxiety and mood disorders, substance use disorders and a history of trauma. Psychiatrists can play a crucial role in helping to address symptoms of other disorders that can present barriers to effective engagement in eating disorder treatment. Improving mood and reducing anxiety can also make people less likely to turn to disordered eating behaviors to regulate mood. Some medications also facilitate reduction of eating disorder symptoms in addition to mood and anxiety symptoms. Psychiatrists may also be more likely to identify disordered eating thoughts and behaviors in their interactions with their patients than other healthcare providers due to their training. Among mental health professionals, they can order necessary lab tests and initiate medical interventions that others cannot.

Administrative Staff:

It may take a significant amount of time for someone to seek and/or receive diagnosis and treatment for an eating disorder. Treatment for eating disorders may be long and uncomfortable, and patients are at risk of prematurely terminating treatment as a result. Administrative staff are often the main communicators in many facilities and often some of the first voices these patients hear as they get help. Treatment cannot work unless patients are willing to start and continue treatment. In addition to helping coordinate treatment and keeping patients coming to their appointments, administrators are also another point to gather important information about barriers to treatment, mental status, behavioral patterns or environmental clues.

The treatment of eating disorders can often be intimidating due to the lack of training most professions receive in how to best identify and help people struggling with these conditions. Collaborating with a multidisciplinary team can improve symptom identification and help clients to address the impact of their behaviors more quickly and effectively. Those who specialize in treating eating disorders can be a resource to those less familiar who suspect a patient or loved one may be suffering from an eating disorder. Local and national resources are available for patients and providers alike to better understand eating disorders and to take steps forward toward happiness and healing.

Citations:

1. Deloitte Access Economics. The Social and Economic Cost of Eating Disorders in the United States of America: A Report for the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders and the Academy for Eating Disorders. June 2020

2. Flament, M. F., Henderson, K., Buchholz, A., Obeid, N., Nguyen, H. N., Birmingham, M., & Goldfield, G. (2015). Weight Status and DSM-5 Diagnoses of Eating Disorders in Adolescents from the Community. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(5), 403–411.e2. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.020

3. Joy, E. A., Wilson, C., & Varechok, S. (2003). The multidisciplinary team approach to the outpatient treatment of disordered eating. Current sports medicine reports, 2(6), 331–336. https:// doi.org/10.1249/00149619-200312000-00009

References:

1. Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q). CORC Child Outcomes Research Consortium. (n.d.). https://www. corc.uk.net/outcome-experience-measures/eating-disorder-examination-questionnaire-ede-q/

2. Home. EAT. (2025, January 9). https://www.eat-26.com/

3. Neda. National Eating Disorders Association. (2025, January 8). https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/

4. Strickland, K. (2025, January 9). How long does eating disorder recovery take? Walden Eating Disorders. https://www.waldeneatingdisorders.com/blog/how-long-does-eating-disorder-recovery-take/

Sara Hamilton, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and the clinical director of the Bariatric Counseling Center.

Chasley Fortune-Pittman, MDS, RD, LD, is a registered dietitian and the dietary director at the Bariatric Counseling Center.

They share the belief that successful health interventions focus on helping people to make changes that are meaningful to them and are sustainable long-term. At the Bariatric Counseling Center, they lead a multidisciplinary team of providers that treat eating disorders, particularly those involving binge-eating behaviors, at the intensive outpatient level of care.

By Camille Irene Hulipas, Lydia Beera and Ramaswamy Sharma, MS, PhD

Eating disorders (EDs), such as anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder and others, are complex mental and behavioral conditions that arise from distorted beliefs regarding body image, lead to abnormal eating, and result in deterioration of physical, mental and social functions. While obesity is not considered to be a mental disorder, it is associated with binge-eating disorder and schizophrenia, and is a known risk factor for bulimia nervosa and depressive disorders. Given that (1) EDs rank second among psychiatric disorders with the highest mortality rates, next only to opiate addiction, (2) their prevalence in children and adults is increasing worldwide, and (3) estimated economic and well-being costs in 2024 were approximately $327 billion, it is important to identify and break their barriers to treatment. Stigmatization associated with EDs is one such critical barrier.

Stigma can involve a cognitive component when it is based on shared beliefs about a group of people and thereby leads to stereotyping — an emotional component manifested as prejudice towards such groups — and a behavioral component that results in discrimination and therefore, disadvantages to that group. Most commonly, EDs are

thought to be self-inflicted lifestyle choices caused by lack of self-discipline that could be overcome easily by assuming personal responsibility; it is also perceived that reasoning and communication with such individuals is challenging (cognitive components). Such perceptions may result in irritation, anger, pity or disgust (emotional component), with society tending to keep distance from such individuals (behavioral component). Each type of ED has its own specific stigma associated with it. For example, anorexia nervosa was considered a disease of affluence, and stereotyped as affecting “skinny, white, affluent girls” (SWAG). However, it is important to note that less than 6 percent of people with an ED are medically underweight. Individuals with a history of obesity have a more severe ED experience than those who have never been obese; weight stigma involving negative beliefs as well as discrimination against large-bodied individuals is also a known risk factor for disordered eating. Weight stigma correlates partially with stigma associated with EDs in terms of their surrounding attitudes, the populations they affect and biopsychosocial factors; the overtly negative stigma towards obesity can contribute to the onset, perpetuation and masking of EDs.

Race, culture and socioeconomic status also play into EDs-related stigmas. People of color are half as likely to be diagnosed with EDs as their Caucasian counterparts; when combined with other factors such as cultural stigma towards mental health, community mistrust of healthcare providers and weight stigma, people of color are severely disadvantaged in terms of diagnosis and positive health outcomes of ED treatment. African Americans and Hispanics are more reluctant to seek help for mental disorders as compared to Caucasians.

Stigma surrounding EDs has negative effects on an individual’s psychological well-being and contributes to self-stigmatization, low self-esteem, non-pursuit of life goals, social withdrawal and poor quality of life. Stigmatization is associated with barriers to disclosure, reluctance to seek treatment, and adherence to treatment protocols. For example, patients with AN wait for an average of eight to nine months before seeking medical consultation.

Nurses and clinicians are not immune to stigmatizing EDs. Some healthcare providers hold strong negative attitudes and stereotypes about people with ED. Inexperienced clinicians and trainees, such as medical students and first-year residents, exhibit cognitive (negative beliefs), emotional (frustration, anger, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, lack of motivation to care for these patients), and discriminatory (social distancing) components of stigma, stemming from patient resistance to change as well as perceived lack of competency in diagnosing and treating EDs. Only about 20 percent of ED-associated patients are correctly diagnosed and treated as compared to patients suffering from other mental health illnesses. Experienced clinicians find treating ED patients difficult because of the lack of systemic resources.

From a healthcare provider’s perspective, lack of knowledge and implicit bias borne from a broader public stigma may negatively impact the time to treatment and, worse, overtly trigger or cause relapse of an ED. The average times from ED onset and treatment ranges from 10-15 years as compared to only 8.2 years for those with other psychiatric conditions such as mood or anxiety disorders. The absence of a timely and accurate diagnosis can potentially exacerbate, prolong, and complicate their illness, worsening the severity of the ED and leading to decreased treatment adherence, mistrust and poorer overall health outcomes. Providers may fail to recognize or even overlook disordered eating behaviors in overweight individuals. This is a worrisome practice as women who were classified as “obese” per body-mass-index (BMI) were significantly more likely to exhibit body image concerns, restrictive food practices, bulimic episodes and other alarming practices when compared to smaller-bodied women. Larger-bodied individuals, despite having the same clinical profile as someone with AN are diagnosed with atypical anorexia nervosa (AAN), which is perceived as less severe than AN, preventing access to adequate treatment. Although AAN appears more frequently, fewer patients with AAN are referred to and admitted for ED-specific care. Diagnostic standards for other specified food and eating disorders (OSFED), under which AAN is categorized, fail to capture the complexity and full clinical picture of a patient and may result in suboptimal treatment. Instead of helping a struggling patient, the stigma associated with EDs may reinforce and even worsen harmful behaviors. Therefore, how should healthcare providers address and screen for EDs in ways that minimize harm and prevent health disparities by including vul-

nerable populations? Destigmatizing EDs by increasing their public awareness is an important first step towards reducing barriers. However, it is critical to design well-thought-out interventions as studies show that using ED stereotypes in public service announcements may lead to increased contempt. Possible improvements could also include continuous enhancement of guidelines as we progress in our learning of EDs, and providing increased training for students, residents and clinicians to better recognize ED symptoms and help them understand that their attitude towards EDs is tantamount to the success of treatment and long-term outcomes.

References:

1. Brelet, L., Flaudias, V., Désert, M., Guillaume, S., Llorca, P. M., & Boirie, Y. (2021). Stigmatization toward People with Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge Eating Disorder: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 13(8), 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ nu13082834

2. Camacho-Barcia, L., Giel, K. E., Jiménez-Murcia, S., Álvarez Pitti, J., Micali, N., Lucas, I., Miranda-Olivos, R., Munguia, L., Tena-Sempere, M., Zipfel, S., & Fernández-Aranda, F. (2024). Eating disorders and obesity: bridging clinical, neurobiological, and therapeutic perspectives. Trends Mol. Med., 30(4), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2024.02.007

3. Cardel, M. I., Newsome, F. A., Pearl, R. L., Ross, K. M., Dillard, J. R., Miller, D. R., Hayes, J. F., Wilfley, D., Keel, P. K., Dhurandhar, E. J., & Balantekin, K. N. (2022). Patient-Centered Care for Obesity: How Health Care Providers Can Treat Obesity While Actively Addressing Weight Stigma and Eating Disorder Risk. J. Acad.Nutr.Diet., 122(6), 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jand.2022.01.004

4. Chen, C., & Gonzales, L. (2022). Understanding weight stigma in eating disorder treatment: Development and initial validation of a treatment-based stigma scale. J.Hlth.Psych, 27(13), 3028–3045. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053221079177

5. Coffino, J. A., Udo, T., & Grilo, C. M. (2019). Rates of Help-Seeking in US Adults With Lifetime DSM-5 Eating Disorders: Prevalence Across Diagnoses and Differences by Sex and Ethnicity/Race. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 94(8), 1415–1426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.02.030

6. Daugelat, M. C., Pruccoli, J., Schag, K., & Giel, K. E. (2023). Barriers and facilitators affecting treatment uptake behaviours for patients with eating disorders: A systematic review synthesising patient, caregiver and clinician perspectives. Euop.Eat.Disord. Rev., 31(6), 752–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2999

7. Field, A. E., Ziobrowski, H. N., Eddy, K. T., Sonneville, K. R., & Richmond, T. K. (2024). Who gets treated for an eating disorder? Implications for inference based on clinical populations. BMC Pub.Hlth., 24(1), 1758. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12889-024-19283-2

8. Flament, M. F., Henderson, K., Buchholz, A., Obeid, N., Nguyen, H. N., Birmingham, M., & Goldfield, G. (2015). Weight Status and DSM-5 Diagnoses of Eating Disorders in Adolescents From the Community. J.Amer.Acad.Child &Adol.Psych. 54(5), 403–411.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.01.020

9. Griffiths, S., Mond, J. M., Murray, S. B., & Touyz, S. (2015). The prevalence and adverse associations of stigmatization in people with eating disorders. Int.J.Eat.Disord., 48(6), 767–774. https:// doi.org/10.1002/eat.22353

10. Harrop, E. N., Mensinger, J. L., Moore, M., & Lindhorst, T. (2021). Restrictive eating disorders in higher weight persons: A systematic review of atypical anorexia nervosa prevalence and consecutive admission literature. Int.J.Eat.Disord., 54(8), 1328–1357. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23519

11. Huryk, K. M., Drury, C. R., & Loeb, K. L. (2021). Diseases of affluence? A systematic review of the literature on socioeconomic diversity in eating disorders. Eat.Behav., 43, 101548. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101548

12. Innes, N. T., Clough, B. A., & Casey, L. M. (2017). Assessing treatment barriers in eating disorders: A systematic review. Eat. Disord., 25(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2016. 1207455

13. Krug, I., Dang, A. B., & Hughes, E. K. (2024). There is nothing as inconsistent as the OSFED diagnostic criteria. Trends Mol.Med., 30(4), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. molmed.2024.01.006

14. McEntee, M. L., Philip, S. R., & Phelan, S. M. (2023). Dismantling weight stigma in eating disorder treatment: Next steps for the field. Front.Psych., 14, 1157594. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyt.2023.1157594

15. Mishra, K., & Harrop, E. (2023). Teaching How to Avoid Overreliance on BMI in Diagnosing and Caring for Patients With Eating Disorders. AMA J.Ethics, 25(7), E507–E513. https://doi. org/10.1001/amajethics.2023.507

16. Nawaz, F. A., Kurdak, H., Dakanalis, A., Argyrides, M., & Kashyap, R. (2024). Editorial: Break the mental health stigma: eating disorders. Front.Psych., 15, 1416250. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyt.2024.1416250

17. National Institute of Mental Health. (2024, January). Eating Disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved December 13, 2024, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders

18. Penwell, T. E., Bedard, S. P., Eyre, R., & Levinson, C. A. (2024). Eating Disorder Treatment Access in the United States: Perceived Inequities Among Treatment Seekers. Psychiatr.Serv. (Washington, D.C.), 75(10), 944–952. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi. ps.20230193

19. Phelan, S. M., Burgess, D. J., Yeazel, M. W., Hellerstedt, W. L., Griffin, J. M., & van Ryn, M. (2015). Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obesity Rev., 16(4), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/ obr.12266

20. Sonneville, K. R., & Lipson, S. K. (2018). Disparities in eating disorder diagnosis and treatment according to weight status, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and sex among college students. Int.J.Eat.Disord., 51(6), 518–526. https://doi. org/10.1002/eat.22846

21. Thompson-Brenner H, Satir DA, Franko DL, Herzog DB. Clinician reactions to patients with eating disorders: a review of the literature. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012 Jan;63(1):73-8. doi: 10.1176/ appi.ps.201100050. PMID: 22227763

Camille Irene Hulipas is a medical student at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine, Class of 2027.

Lydia Beera is a medical student at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine, Class of 2027.

Ramaswamy Sharma, MS, PhD, is a Professor of Histology and Pathology at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine. He is interested in delineating the multiple molecular and cellular roles of melatonin in maintaining our quality of life. Dr. Sharma is a member of the BCMS Publications Committee.

By Ramon S. Cancino, MD, MBA, MS, FAAFP, and Richard M. Peterson, MD, MPH, FACS, FASMBS, DABS-FPMBS

The American Medical Association declared obesity a disease in 2013, and its prevalence remains well above the Healthy People 2030 goal of 36.0 percent. In the United States, the obesity rate among adults is 40.3 percent, which means two in five adults are obese (Body Mass Index [BMI] 30 kg/m2 or greater).1

In Texas, the current rate of the disease of obesity is at 35 percent. Bexar County alone fares even worse with overweight (BMI 25-30 kg/ m2) and obesity rates as high as 72 percent, which is much higher than the national average.

Obesity has many health consequences affecting every organ system of the body. In South Texas, we see a disproportionately high number of individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which goes hand-in-hand with this ubiquitous disease.

The health consequences of obesity do not stop with T2DM. Other comorbidities that are commonly associated with this disease are hypertension, stroke, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver disease (now identified as metabolic associated steatohepatitis — MASH), and gastroesophageal reflux disease.2 Each of these listed comorbidities can come with dire consequences to individuals. Considered one of the most inflammatory diseases, obesity exacerbates all these comorbidities and more. In fact, obesity has been linked to several common cancers and also increases the risk of dying from cancer.3

The first step in understanding prevention and treatment is disease recognition. One of the easiest ways to help understand this disease is to think of the cancer treatment model. Cancer treatments can include medical and surgical options and, often, both. Most people perceive cancer as a process that affects the individual and do not necessarily assign fault to the individual for the disease. Unfortunately, obesity is

often seen as the fault of the individual, who may consume too many calories or live a sedentary lifestyle. This is far from the truth. While diet and exercise are a part of what an individual can often control with respect to their environmental exposure of their disease, an individual cannot control their genetics or their underlying metabolic state that leads to this disease. In addition, an individual may have little control over their environment or social status. Implicit weight bias can have detrimental effects on patients and, therefore, how we communicate can impact how we connect with patients about its treatments.4,5

Once we recognize obesity as a disease, we are then able to talk to our patients about treatment options. Both medical and surgical treatments are available and effective in the treatment of obesity. Obesity is a chronic disease and like cancer, can remain in remission for a lifetime after treatment, or may unfortunately recur, requiring further therapy.

Several FDA-approved medications have demonstrated efficacy in promoting weight loss when used in conjunction with lifestyle modifications. The most effective options include GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as semaglutide and liraglutide, which can lead to significant weight reductions of 10-20 percent of body weight. Tirzepatide, a dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, has shown even greater weight loss potential in clinical trials. Other options include combination therapies like phentermine-topiramate and naltrexone-bupropion, as well as orlistat, which work through different mechanisms to support weight management. Because these medications are more effective with lifestyle modification, patients should work closely with their primary care physicians or other medical specialists, like endocrinologists, before starting any medications. This will ensure a holistic plan is in place that includes recognition of patient goals, other medical

comorbidities, social and financial factors, and the appropriate medical team members, such as behavioral health practitioners or registered dietitians.

Today there are several surgical options that individuals with obesity can consider, and the type of surgery is tailored to the individual based on their level of obesity and the comorbidities from which they also may suffer. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) endorses the following procedures for the treatment of obesity: adjustable gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy, rouxen-y gastric bypass (RNYGP), biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch (BPD/DS), single anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy with sleeve (SADI-S), one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), intragastric balloons and reoperative procedures.

The first surgeries for obesity began in 1966 under the pioneer, Dr. Edward Mason. There have been many novel operations since that time, but the roux-en-y gastric bypass still stands as one of the gold standards of the surgical treatment of obesity. For over 50 years, surgery has remained the most effective and durable option in the fight of the disease of obesity. Today, surgery has the longest followed outcomes in the treatment of this disease. Over the last 20 years, the dedication of surgery to quality outcomes, led by the ASMBS and in partnership with the American College of Surgeons (ACS), formed the Metabolic Bariatric Surgery Accreditation Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) to track quality data in this area. With over one million patients being followed and 947 nationally accredited programs (90 of which are in Texas), improvements in care quality have been tracked. Improvements in surgery and technique with metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) are such that, today, an individual undergoing an MBS procedure, is safer than having their gallbladder or appendix removed.

In the United States, only 1 percent of eligible patients receive metabolic and bariatric surgery. The sleeve gastrectomy remains the most common operation performed with approximately 60 to 70 percent of the individual’s excess weight being lost after this treatment. The roux-en-y gastric bypass is the second most common surgery performed with 70 to 80 percent of excess weight loss. As mentioned earlier, these surgeries have been proven to be some of the safest surgeries performed, with death rates noted to be less than 0.05 percent. The efficacy of surgery is also seen in the comorbidity resolution with T2DM noting a resolution/remission rate of greater than 80 percent, hypertension improvement/resolution of 70 percent and obstructive sleep apnea resolution greater than 75 percent. In addition, cancer risk reduction of 60 percent is seen with MBS.

In 2022, the ASMBS and the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity (IFSO) released and updated the 1991 NIH Consensus Statement on bariatric surgery. The current guidelines6 recommend MBS:

• For individuals with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35 kg/m2, regardless of presence, absence or severity of comorbidities.

• MBS should be considered for individuals with metabolic disease and BMI of 30-34.9 kg/m2.

• BMI thresholds should be adjusted in the Asian population such that a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 suggests clinical obesity, and individuals with BMI ≥ 27.5 kg/m2 should be offered MBS.

• Appropriately selected children and adolescents should be considered for MBS.

The recognition of obesity as a complex, multifaceted disease is critical for improving patient outcomes and advancing treatment approaches. Physicians play a pivotal role in reframing the narrative around obesity, emphasizing its biological, environmental and social determinants rather than perpetuating stigma. By adopting evidence-based medical and surgical treatments, alongside lifestyle and behavioral interventions, we can offer patients effective and sustainable options for weight management and comorbidity resolution. Collaboration across specialties, combined with advancements in pharmacological and surgical therapies, has the potential to transform the landscape of obesity care. Ultimately, it is our collective responsibility as physicians to advocate for our patients, challenge implicit biases, and implement comprehensive care models that address this pervasive and life-altering disease.

References:

1. Emmerich, S., Fryar, C., Stierman, B., Ogden, C. Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in Adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2024. doi:10.15620/cdc/159281

2. Health Risks of Overweight & Obesity - NIDDK. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/ health-information/weight-management/adult-overweight-obesity/health-risks

3. Pati, S., Irfan, W., Jameel, A., Ahmed, S., Shahid, R. K. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers. 2023;15(2):485. doi:10.3390/cancers15020485

4. Abbott, S., Shuttlewood, E., Flint, S. W., Chesworth, P., Parretti, H. M. “Is it time to throw out the weighing scales?” Implicit weight bias among healthcare professionals working in bariatric surgery services and their attitude towards non-weight focused approaches. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;55. doi:10.1016/j. eclinm.2022.101770

5. Puhl, R., Suh, Y. Health Consequences of Weight Stigma: Implications for Obesity Prevention and Treatment. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(2):182-190. doi:10.1007/s13679-015-0153-z

6. Eisenberg, D., Shikora, S. A., Aarts, E., Aminian, A., Angrisani, L., Cohen, R. V., De Luca, M., Faria, S. L., Goodpaster, K. P. S., Haddad, A., Himpens, J. M., Kow, L., Kurian, M., Loi, K., Mahawar, K., Nimeri, A., O’Kane, M., Papasavas, P. K., Ponce, J., Pratt, J. S. A., Rogers, A. M., Steele, K. E., Suter, M., Kothari, S. N. 2022 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis Off J Am Soc Bariatr Surg. 2022;18(12):1345-1356. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2022.08.013

Ramon S. Cancino, MD, MBA, MS, FAAFP, is Executive Director of the UT Health San Antonio Primary Care Center and co-Chair of the Joint UT Health San Antonio/MD Anderson Mays Cancer Center Cancer Prevention and Steering Committee. Dr. Cancino is a member of the Bexar County Medical Society.

Richard M. Peterson, MD, MPH, FACS, FASMBS, DABSFPMBS, is Professor and Chief of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery at the UT Health San Antonio. He is a past president of the Texas State Chapter of the ASMBS and current PresidentElect of the ASMBS.

By Alison Bartak and Ramaswamy Sharma, MS, PhD

Feeding and eating disorders, characterized by severe and persistent disturbances in eating that negatively affect physical, psychological and social functions, include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, pica, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorders (ARFID) and ruminant disorder. Around 29 million (9 percent) U.S. adults suffer from these disorders, with a mortality rate of 10,200 deaths per year. Among these, the mortality rate of young individuals with anorexia is 12 times higher as compared to similar-aged individuals without anorexia. Therefore, it is important to diagnose this potentially fatal disorder as early as possible.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5-TR; 2022) lists three important features for diagnosis: decreased energy intake relative to the body’s requirements in the context of age, developmental stage and sex, extreme fear of weight-gain or becoming fat even if underweight, and either excessive consideration of body weight and/or shape when evaluating oneself or inability to

understand the consequences of their low body weight, termed anosognosia. Patients with anorexia nervosa may have decreased levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, differences in activation of the corticolimbic system, and decreased executive functions mediated by the frontostriatal circuits, resulting in multiple behavioral changes and psychiatric disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder. Prolonged exercise, restrictive eating or starving as well as excessive purging behaviors via vomiting, use of laxatives or enemas can lead to serious medical consequences. Seriously underweight individuals may show signs of depression.

Body mass index (BMI) has been used over many years to diagnose anorexia. Adults with a BMI less than or equal to 17, 16-16.99, 15-15.99, or less than 15 kg/m2 are considered to be suffering from mild, moderate, severe or extreme anorexia respectively; children and adolescents below the 5th percentile when evaluated using an appropriate age-based BMI calculator (www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/bmi/

calculator.html) are significantly underweight. However, BMI is no longer used as a diagnostic tool and its use has been restricted for assessing disease severity.

Other nuanced physical signs of anorexia nervosa can be found in the beginning stages (one to three months), intermediate stages (three to six months) and in more advanced stages (more than six months); identifying these changes could potentially lead to early diagnosis and treatment before irreversible damage occurs.

Within the first one to three months, an individual with anorexia nervosa may experience thermoregulatory changes as well as hair, skin and nail changes. Decreased thermoregulation occurs as a consequence of reduction in weight, which includes loss of insulating subcutaneous fat, decreased metabolism for conservation of energy, and vasoconstriction of peripheral capillaries for conserve core body temperature. Malnutrition can also lead to dysfunction of the hypothalamus, which acts as the body’s thermostat. The overall decrease in heat production results in the patient experiencing cold sensitivity and cold extremities. To compensate for the heat loss and protect the body, lanugo hair, which is thin, downy, pigmented hair that appears on the back, abdomen, forearms, along the spine, sometimes the sides of the face, and on the neck and legs, may develop. Malnutrition, specifically protein and micronutrient deficiency, also affects skin and nails. Protein deficiency and dehydration impair skin cell turnover as well as its barrier function, leading to pale, dry, paper-like skin that bruises easily and repairs poorly. Micronutrient deficiencies, especially deficiencies in Zinc and Vitamin B, impact nail matrix formation, manifested as brittle nails.

As the disease progresses, within a three-to-six-month period, the body begins to experience systematic changes that include changes in reproductive, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal functions. Endocrinopathies associated with disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, altered growth hormone secretion and activity, and decreased leptin and increased ghrelin levels begin to manifest. Decreased gonadotropin releasing hormone from the pituitary lowers estrogen levels and ultimately results in secondary amenorrhea in adult females; menarche is delayed in prepubertal females. Decreased sperm count and quality is observed in males. Hypothyroidism reduces metabolic rates and is associated with dry skin, hypothermia, hypotension and bradycardia, observed as dizziness when standing and syncope. Within the GI tract, digestive processes begin to slow due to reduced nutritional intake. Patients can experience delayed gastric emptying, decreased intestinal mobility, reduced enzyme production, and altered gut microbiome composition. This could be reflected physically in the individual as constipation and abdominal pain.

While most of these symptoms are reversible, long term and potentially irreversible consequences may occur. In addition to the physical symptoms previously described, loss of bone density, muscle wasting and increased consequences to electrolyte imbalance become apparent. More than 90 percent of women with anorexia exhibit reduced bone density, 38 percent of whom are diagnosed with osteoporosis and hence, an increased risk for fractures. Females with binging and then purging subtype of anorexia nervosa have a higher risk for developing osteoporosis as compared to the restricting subtype. Reduced estrogen, calcium and Vitamin D levels ultimately contribute to impaired bone formation, while elevations in stress-induced catecholamine and cor-

tisol increase bone resorption. To balance its energy needs, protein is catabolized for gluconeogenesis, protein synthesis required for muscle maintenance is decreased and exercise capacity is reduced, leading to disuse atrophy and muscle-wasting. Continued electrolyte imbalances involving sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium and phosphate can lead to impacts on membrane potential and cellular function and induce muscle weakness, confusions/altered mental state, seizures, tetany, numbness and tingling, and in some severe cases, heart and respiratory failure. Other long-term complications include infertility, short stature, dilated cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, mitral valve prolapse, brain atrophy, pre-renal renal failure and others.

The tell-tale signs of anorexia nervosa are often classified at much later stages. Understanding the potential warning signs is crucial for early identification and treatment/management before the onset of irreversible damage.

References:

1. Aldridge, D. (2023, November 20). Lanugo: Anorexia hair growth explained. Eating Recovery Center. https://www.eatingrecoverycenter.com/resources/lanugo-anorexia#how-is-lanugo

2. American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi. books.9780890425787

3. Bunnell, D. (2024, April 30). Eating Disorder Statistics. National Eating Disorders Association. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics/

4. Guarda, A. (2023) What are Eating Disorders? American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders

5. Ramaswamy, N., & Ramaswamy, N. (2023). Overreliance on BMI and delayed care for patients with higher BMI and disordered eating. The AMA Journal of Ethic, 25(7), E540-544. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2023.540

6. Moore, C. A., & Bokor, B. R. (2023, August 28). Anorexia nervosa. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/books/NBK459148/

7. Pike, E. Eating Disorder Statistics 2024 | Anorexia, bulimia, Binge Eating & ARFID. (2024, February 14). Eating Recovery Center. https://www.eatingrecoverycenter.com/resources/eating-disorder-statistics

8. The Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness. (2024, August 16). Eating Disorder Statistics: An updated view for 2024. National Alliance for Eating Disorders. https://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/eating-disorder-statistics-an-updated-view-for-2024/

9. Usdan, L.S., Khaodhiar, L., & Apovian, C.M. (2008). The endocrinopathies of anorexia nervosa. Endocrine Practice, 14(8), 1055–1063. https://doi.org/10.4158/ep.14.8.1055

Alison Bartak is a medical student at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine, Class of 2027. Her current interests include Preventative Medicine and Surgery.

Ramaswamy Sharma, MS, PhD, is a Professor of Histology and Pathology at the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine. He is interested in delineating the multiple molecular and cellular roles of melatonin in maintaining our quality of life. Dr. Sharma is a member of the BCMS Publications Committee.

By Victoria (Tori) Vargas

Social media has become a cornerstone of modern society, shaping how we connect, communicate, and share our lives. Popular platforms like Twitter, Instagram and TikTok spread trends and promote lifestyles tailored to each user. While these platforms offer a sense of connection and entertainment, they also present distorted views of health, fitness and beauty, often promoting inaccurate or misleading habits. Together, these factors can significantly impact users’ mental and physical well-being, contributing to the development of eating disorders such as anorexia, bulimia and binge-eating disorder.

Social media’s effectiveness in spreading information lies in its vast reach, algorithm-driven content delivery and diverse user base. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok cater to millions worldwide, offering personalized content based on user interests and behaviors. Once a user searches for specific topics, their feed becomes filled with related content. This tailored approach makes social media an incredibly powerful tool for sharing trends, advice and lifestyle tips. However, the sources of this information vary widely — from certified health professionals to influencers with little expertise. Misinformation is

prevalent on these platforms, and the algorithm helps spread content at an alarming rate, often regardless of the quality of the information.

Although people of all ages engage with social media, teenagers and young adults make up the largest group of users and are especially vulnerable to its influence. In 2023, 78 percent of U.S. Gen Z (born between 1997 and 2013) used TikTok, making them particularly impressionable. This demographic tends to internalize advice and adopt behaviors without questioning the credibility of the source. Social media’s combination of engaging visuals, relatable creators and peer validation is effective in shaping perceptions and habits — whether those habits are beneficial or harmful. Adolescence and young adulthood are critical periods for habit formation, making this age group particularly susceptible to adopting unhealthy behaviors.

While social media platforms were initially designed for communication and entertainment, they have evolved into sources of education, particularly in health and fitness. Many influencers, often showcasing desirable physiques, create content that others seek to emulate. As people turn to influencers for advice on nutrition, workouts and wellness,

they may adopt unsustainable or unhealthy behaviors. Many influencers, who are not qualified health professionals, promote diets, supplements and exercise regimens that lack scientific support or medical safety.

For example, diet trends like extreme calorie restriction or intermittent fasting are often popularized by influencers claiming dramatic health benefits. While these approaches may yield short-term results, they are typically unsustainable and can encourage harmful eating behaviors. Influencers may also label certain foods or food groups as “bad,” complicating people’s relationship with food and nutrition. As a result, users relying on social media for fitness advice may unknowingly adopt habits that increase their risk of developing an eating disorder.

At the heart of many eating disorders lies dissatisfaction with one’s body image, often fueled by external influences. Social media exacerbates this issue by portraying unrealistic standards of beauty and fitness. Platforms encourage sharing personal photos, many of which reflect an idealized physique. Instagram and TikTok are filled with influencers showcasing “perfect” bodies — slim, toned and symmetrical — often achieved through intense workouts and extreme dieting. While these photos may not appear deceptive, they often overlook factors such as genetics, lighting and the use of filters or editing software that alter appearances.

Some fitness influencers promote healthy methods and share unedited, authentic photos, but their approach to promoting fitness varies. For some, the primary goal is engagement or sponsorship, rather than authenticity or education. These influencers may use tactics that prioritize hooking viewers or gaining interactions, sometimes at the expense of providing accurate or responsible advice. The constant exposure to such “perfection” can lead to body dissatisfaction, and individuals may adopt extreme dieting, over-exercising, or purging in an attempt to conform to these idealized physiques.

While social media may not directly cause eating disorders, its influence is undeniable. Research shows that increased time spent on these platforms is linked to greater body dissatisfaction and a higher likelihood of adopting unhealthy eating habits. Social media fosters an environment of constant comparison, fueling insecurities. Furthermore, the flood of advice shared online is often inaccurate, failing to consider an individual’s unique health needs or goals. Both the images and the information encountered on social media should be approached critically, with users conducting their own research to verify what they see.

The focus on physical appearance in online spaces also leaves little room for discussions about mental health, self-care or body positivity. As eating disorders are often stigmatized and difficult to discuss, this lack of representation can further isolate individuals who are struggling, making it harder for them to seek help or even recognize their behaviors as problematic.

While the potential harms of social media on eating behaviors are clear, there are ways to mitigate its negative effects. Promoting body positivity, encouraging diverse representations of beauty and health, and teaching realistic portrayals of fitness and nutrition are steps in combating the rise of eating disorders. Some users have already begun challenging these trends by posting both edited and unedited versions of their fitness pictures, showing how lighting, posing and editing create the “perfect” form.

Education may be the most important step. Empowering individuals to critically engage with the content they encounter online — understanding that not everything they see reflects reality — can help reduce the likelihood of adopting unhealthy behaviors. Encouraging users to follow qualified professionals in nutrition and fitness, rather than unverified influencers, can provide more accurate and helpful information. It is important to recognize that short videos cannot properly guide a person’s health, and patient health should be discussed with healthcare professionals. While many physicians may not directly engage with media to counter misinformation, initiating conversations during appointments and providing proper education is key to combating the spread of misleading content.

Social media undoubtedly plays a significant role in shaping modern culture, particularly in health and fitness. However, its role in perpetuating unrealistic body ideals and promoting harmful behaviors cannot be ignored. By recognizing its potential harms, especially among vulnerable users, we can better understand patients with eating disorders. This approach will help create a more supportive online environment, combat the prevalence of eating disorders, and encourage healthier physical and mental well-being.

References:

1. Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2020). Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 104949. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104949

2. 2. Hunter, A., Stiles, C. E., & Fullwood, C. (2022). Social media and eating disorders: A rapid review of the evidence and applications for prevention and treatment. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(11), e0001091. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pgph.0001091

3. 3. Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2023). Eating disorders prevalence by age. Our World in Data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/eating-disorders-prevalence-by-age

4. 4. Sharif, S. P., Waseem, M., Rana, S., & Razak, N. A. (2021). Social media addiction and psychological wellbeing: A systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e17187. https://doi.org/10.2196/17187

5. 5. Sprout Social. (2023). Social media demographics to inform your brand’s strategy in 2023. Retrieved from https://sproutsocial.com/insights/new-social-media-demographics/#instagram

Victoria (Tori) Vargas is a medical student at the Long School of Medicine, Class of 2026.

By Rosa I. Vizcarra, MD, FAAFP

The aging population in the United States has changed significantly over time. Average life expectancy increased from 47 years in 1900 to about 79 years in 2014. By 2030, individuals over the age of 65 will exceed 20 percent of the U.S. population; by 2050, they will constitute over 20 percent of the world’s population. Aging is characterized by weakened homeostasis and diminished organ system reserves. Data in older adults hospitalized for acute medical conditions stated that up to 71 percent of them are at nutritional risk or malnourished, which is associated with higher mortality risk. More people are surviving to an older age and eating well is vital for everyone.

Aging is associated with common physiological changes like decrease in bone mass, lean mass and water content. However, fat mass mainly increases to expand intra-abdominal fat storage. These changes prompt a reduction in basal metabolic rate for the elderly, meaning a standardized nutrition requirement for younger or middle-aged adults cannot be generalized to elderly adults.

Daily food choices are extremely important as they directly impact energy levels on many diseases such as cardiovascular (coronary artery disease, myocardial infarct), neurological (stroke) and endocrinological (diabetes) conditions. Elderly nutritional needs are dictated by

multiple variables including organ compromise, activity levels, food accessibility, ability to prepare and ingest food, as well as personal food preferences.

Older adults should be encouraged to adopt a healthy lifestyle as this lowers their risk of developing a disability. In one cohort of 65 years and older without disability at baseline and followed for 12 years, the risk of developing moderate to severe disability was greater for individuals who had only low or intermediate levels of physical activity, ate less than one serving of fruit or vegetable daily, or were current or recent smokers.

Guidelines from The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies recommend a diet including 20 to 35 percent of energy as fat, with reduced intake of cholesterol, saturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids. They also suggest 45 to 65 percent of energy as carbohydrates, preferably complex carbohydrates in the form of fiber. Daily fiber intake for a 60-year-old consists of 30 grams for males and 21 grams for females. Protein intake is recommended as 10 to 35 percent of total energy.

Recommended dietary allowance (RDA) is the average daily micronutrient intake level estimated to meet the requirement of nearly all (97 to 98 percent) healthy individuals.

of

Selenium

Sodium 2,300 mg (1 teaspoon)* 2,300 mg (1 teaspoon)*

*Sodium if HTN 1,500 mg per day (⅔ teaspoon)

Nutritional status in this population can be influenced by several other factors. It is important to keep these in mind as many can be modifiable.

Risk Factors for Poor Nutritional Status

Alcohol or substance abuse

Cognitive deficiencies

Decreased physical activity

Depression-Mood disorders

Functional limitations

Financial hazard

Limited education

Limited mobility-transportation

Chronic disease process

Poor dentition

Medications

Restricted diet-poor dietary habits

Social Isolation

Obesity is most prevalent in older adults in their 60s and 70s. Excess body weight and modest weight gain (>5kg) in middle age can be associated with medical comorbidities later in life, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea and osteoarthritis. Data has also shown that higher BMI in older populations may have a protective effect against mortality rates, with the lowest rates for those with BMI between 27 and 29. The theory is that fat mass stores energy that can be used during negative energy balance states like acute illness. BMI gain or loss was associated with increased mortality whereas BMI stability was not.

It is easier to prevent undernutrition than to treat malnutrition. One recommendation to enhance food intake is to cater to food preferences as much as possible. Patients should receive appropriate hand and mouth care when preparing for meals and be in a comfortable position; assistance should also be provided to those who need help. Increased sociability increases food intake. Food should be of appropriate consistency with attention to color, texture, temperature and arrangement; the use of herbs, spices and temperature could compensate for loss of taste and smell. Hard to open packages are not recommended and adequate time should be given for leisurely meals. Although supplementing protein produces a small but consistent weight gain in older adults, evidence does not support routine supplementation for older adults who are well nourished.

Nutrition is a definite concern for older adults, as there are various factors that have to be accounted for, including significant age-related changes, metabolic diseases, medication interactions and side effects, as well as social and functional components. It is essential to continue to address these factors to ensure the health of the aging population. A healthy diet leads to healthy aging!