AMONG PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES IN NORTHEAST OHIO

AMONG PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES IN NORTHEAST

AMONG PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES IN NORTHEAST OHIO

At The University of Akron, students become confident leaders, engaged community members and career-ready graduates. We provide the connections and support to make their time in college result in much more than earning a degree.

At The University of Akron, students become confident leaders, engaged community members and career-ready graduates. We provide the connections and support to make their time in college result in much more than earning a degree.

At The University of Akron, students become confident leaders, engaged community members and career-ready graduates. We provide the connections and support to make their time in college result in much more than earning a degree.

Our students bring their passion, and we provide the possibilities.

Our students bring their passion, and we provide the possibilities.

Our students bring their passion, and we provide the possibilities.

JACK, JOSEPH AND MORTON MANDEL CONCERT HALL AT SEVERANCE MUSIC CENTER

PAGE 5

Thursday, July 11, 2024, at 7 PM

Oksana Lyniv, conductor | Inon Barnatan, piano

JANÁ Č EK Suite from The Cunning Little Vixen (comp. Sir Charles Mackerras)

RACHMANINOFF Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43

LIATOSHYNSKY Grazhyna, Op. 58

STRAVINSKY Suite from The Firebird (1919 version)

PAGE 21

Thursday, July 25, 2024, at 7 PM

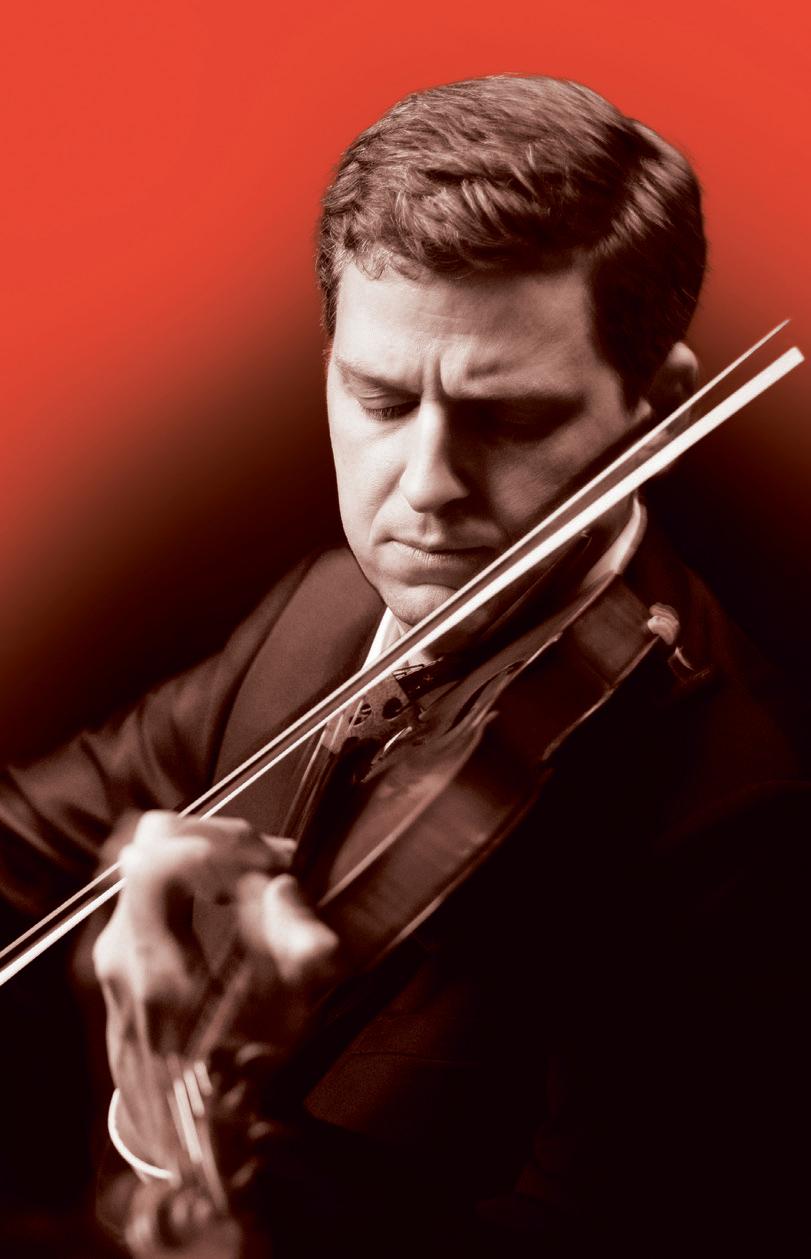

Petr Popelka, conductor | James Ehnes, violin

FRANCK Le Chasseur maudit (The Accursed Huntsman)

KORNGOLD Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

DVO Ř ÁK Symphony No. 6 in D major, Op. 60

PAGE 35

Thursday, August 15, 2024, at 7 PM

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

MOZART Symphony No. 35 in D major, K. 385, “Haffner”

BRUCKNER Symphony No. 4 in E-flat major, “Romantic” (1878/80 version, ed. Benjamin M. Korstvedt)

PAGE 47

ARTIST & CONDUCTOR BIOGRAPHIES

Whether escaping the bustle of daily life with a beloved classic or discovering new worlds with the less familiar, come share the extraordinary this season with The Cleveland Orchestra .

When you subscribe, you provide vital support to your Cleveland Orchestra and enjoy these exclusive benefits:

•The best seats at the best prices

• Free and easy ticket exchanges

• Purchase your parking in advance

• 20% off additional ticket purchases

• 10% off at The Cleveland Orchestra Store

• Money back guarantee

Thursday, July 11, 2024, at 7 PM

Leoš Janáček (1854–1928)

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943)

Borys Liatoshynsky (1895–1968)

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Suite from The Cunning Little Vixen 20 minutes (comp. Sir Charles Mackerras)

Rhapsody on a Theme 25 minutes of Paganini, Op. 43

Inon Barnatan, piano

INTERMISSION 20 minutes

Grazhyna, Op. 58 20 minutes

Suite from The Firebird 20 minutes (1919 version)

Introduction and Dance of the Firebird

Dance of the Princesses

Infernal Dance of King Kashchei Berceuse

Finale

Total approximate running time: 1 hour 45 minutes

Thank you for silencing your electronic devices.

Although Leoš Janáček, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Borys Liatoshynsky, and Igor Stravinsky all hail from places grouped under the banner of Eastern Europe, their music reveals as much difference as it does consensus. The sources of inspiration and circumstances of performance and reception of the works on tonight’s program featuring conductor Oksana Lyniv and pianist Inon Barnatan show a diversity of creative approaches and relay the range of living and working conditions that defined each composer’s life. While the divergences illustrated by four near-contemporaries are largely the result of centuries of Russian imperialism, these orchestral works are, nonetheless, bound together by their shared employment of poetic expressivity.

Written at his villa on the banks of Lake Lucerne, Rachmaninoff gave his concertante piece for piano and orchestra the title “rhapsody,” a term used in Ancient Greece for part or all of an epic poem meant to be recited before an audience. Although more contemporary usage of the word invokes merely an effusive expression of emotion and Rachmaninoff ’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini meets the brief the variations and development of the main theme cannot resist narrativizing, so much so that Michel Fokine, the original choreographer of Stravinsky’s The Firebird, also choreographed the piece as part of his ballet Paganini.

Flanking the Rhapsody are three programmatic pieces for orchestra by Janáček, Liatoshynsky, and Stravinsky, which draw on diverse sources to communicate vastly different messages. Composed during his time with the Ballets Russes in Paris, Stravinsky turned to old Russian folklore for a fantastical fairytale about good and evil, producing music meant to bring Parisian audiences under the spell of Russian culture through romantic leitmotifs and exotic orchestral colors.

Although Janáček’s source was much more contemporary a comic strip published in a Brno newspaper the Czech composer also turned to a mythical, animal subject, scoring the adventures of a crafty vixen. Janacek incorporated Moravian folk melodies and rhythms while creating a “comic” opera that reflects philosophically on liberation, love, aging, and death.

In contrast, Ukrainian composer Liatoshynsky turned to a much more serious and tragic source for his symphonic ballad Grazhyna. Based on the anti-imperial poetry of Polish national poet Adam Mickiewicz, the music depicts the self-sacrifice of a fictional Lithuanian heroine who dies in battle defending her homeland.

— Leah Batstone

by Leoš Janáček

BORN : July 3, 1854, in Hukvaldy, Moravia

DIED : August 12, 1928, in Ostrava, Czechoslovakia (now part of the Czech Republic)

▶ COMPOSED : opera, 1921–23; suite, 2006

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : The opera was first presented in Brno on November 6, 1924, conducted by František Neumann.

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE : Though this performance marks the first presentation of the Suite from The Cunning Little Vixen by The Cleveland Orchestra, the Orchestra has staged the full opera twice (in 2014 and 2017), both conducted by Music Director Franz Welser-Möst.

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 4 flutes (3rd and 4th doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (xylophone, side drum, bass drum), celesta, harp, and strings

▶ DURATION : about 20 minutes

AS LEO Š JANÁ Č EK APPROACHED his 68th birthday, the looming specter of mortality clouded a period of artistic productivity. He wrote in February 1922, “I am experiencing sad moments. …Why do bygone thoughts try to press forward to the light? I had no time for such thoughts before: that was life. Some violent change is hatching in the body, in the blood.”

Despite the recent premiere of his opera Káťa Kabanová in November 1921 which Janáček himself deemed “a decided success” it appeared that age was finally catching up with him. After an entire career’s worth of teaching, archiving folk songs, and composing

many unrecognized pieces, Janáček finally found acclaim when his opera Jenůfa premiered in 1904 as he was approaching 50.

Almost 20 years on, however, these overdue successes did little to ease the burdens of the sexagenarian. Janáček had become obsessed with Kamila Stösslová, a married woman 38 years his junior. They shared a close friendship, but Janáček’s love would remain unrequited Janáček was himself married and their respective status quos would remain intact. Nevertheless, Stösslová was the muse for many of Janáček’s late works, including Káťa Kabanová. Stösslová’s cool recep-

nately for him, while their friendship would continue, his unbalanced love for Stösslová would never equalize.

tion to the premiere of Káťa tormented Janáček. In many letters, he laments his age and unrequited infatuation with her, at one point bluntly asking, “Can’t you even say thank you for Káťa?” Unfortu-

Meanwhile, during this post-Káťa turmoil, Janáček turned to his next opera, an adaptation of a popular serial depicting the misadventures of a wry young vixen, which had amused Janáček upon its

release in 1920. As he worked on The Cunning Little Vixen (known in Czech as Příhody lišky Bystroušky), the dark thoughts that pervaded his February mood eased, and by the end of March 1922 he had finished a draft of Act I. Work proceeded quickly, and in September he wrote Stösslová that he was “[Writing] cheerfully, I’m now writing a merry opera.” By October, he had completed a full draft and continued to rework the piece for a full year. The vocal score was published in July 1924, and the premiere took place at the National Theater in Brno that November, the same theater that had premiered Jenůfa 20 years prior.

Reception to The Cunning Little Vixen was mixed. Janáček himself was pleased with the staging, laughing with glee at the animal performers and weeping at the finale during rehearsals. Brno audiences knew the serial on which the opera was based and were delighted by the libretto’s use of the Líšeň dialect, which had originated in Brno. Critics had a more complicated reaction, praising the music but criticizing the plot (and, by proxy, the source material). Nevertheless, The Cunning Little Vixen has endured, becoming a mainstay on global opera stages. Janáček continued to hold the work in high regard. The music from the finale that made him weep had a lasting impact; after a rehearsal, he told the opera’s producer, “You must play this for me when I die,” a desire that came true at Janáček’s funeral in 1928.

The music comprising this Suite from

The Cunning Little Vixen compiled by conductor Sir Charles Mackerras in 2006 is entirely from Act I, which depicts the youth of the eponymous protagonist. The Vixen is captured by a Forester and brought to his home, and grows to young adulthood amidst persistent cruelty from the animals and children that reside there. Tired of captivity, she rallies and then slaughters a group of hens as a distraction to escape to freedom. The music balances mischief and malice, and Janáček’s colorful harmonies and orchestration adorn melodies that are in part based on his transcriptions of actual animal calls.

While the opera as a whole can be tricky to pin down (is it optimistic and comic or pessimistic and tragic?), having animals as the primary characters certainly lends an air of whimsy to the work. Janáček had always been enamored with animals, and as a former maid attested, “He talked to the hens as to children, they looked at him, answered something, and he understood … he rapped on the table like a schoolmaster at school, [and] the hens came running at once.” And yet, in The Cunning Little Vixen the hens are slaughtered. Perhaps the elder Janáček saw himself as the Vixen, killing the hens to escape captivity. But rather than the fences of the Forester, the captivity Janáček was running from was the march of time.

— Tanner Cassidy

Tanner Cassidy is operations manager for the Four Seasons Chamber Music Festival. He is a PhD candidate in music theory at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and has written program notes for the Music Academy of the West.

by Sergei Rachmaninoff

BORN : April 1, 1873, in Semyonovo, Russia

DIED : March 28, 1943, in Beverly Hills, California

▶ COMPOSED : 1934

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : November 7, 1934, in Baltimore, with the composer as soloist and Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE : November 4, 1937, conducted by Music Director Artur Rodziński with the composer as soloist

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, glockenspiel), harp, and strings, plus solo piano

▶ DURATION : about 25 minutes

WHAT IS IT IN THE MELODY of the 24th violin caprice by Niccolò Paganini (1782–1840) that has made it so irresistible to composers as diverse as Robert Schumann, Liszt, Brahms, Lutosławski, and many more? The answer lies in the theme’s extreme simplicity, which seems to cry out for embellishment in the form of virtuoso variation. Of course, that had been Paganini’s original purpose, too, since he was the first one to create a bravura piece from the famous theme. At a time when Sergei Rachmaninoff had all but stopped composing (due to his emigration from Russia and his heavy schedule as a concert pianist), Paganini’s caprice provided him with the necessary

impulse to write what would become one of his most popular compositions, along with the Second Piano Concerto. (That work, too, had come at the end of a fallow period in Rachmaninoff ’s life, some 30 years earlier.) In the 1930s, Rachmaninoff built a villa on Lake Lucerne in Switzerland, which he named “Senar” (after the first letters of Sergei and Natalia, his wife). Happy to find a permanent home after years of incessant concertizing, he saw his creativity return: the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini was to be immediately followed by the Third Symphony.

The Rhapsody begins by stating the intervals of a fifth on which the Paganini

At the Rhapsody’s 1934 premiere, Rachmaninoff drank a shot of mint liqueur to calm his nerves before playing the tricky final variation. He continued the tradition in subsequent performances, dubbing it the “Crème de Menthe Variation.”

theme is built. Rachmaninoff ’s procedure is similar here to the one followed by Beethoven in the last movement of the “Eroica” Symphony, where the appearance of the theme is preceded by its “skeleton.” Rachmaninoff then introduces the Paganini theme in the orchestra, while the solo piano keeps on playing the “skeleton” of the melody.

Soon, however, the piano takes over the melody, and the ornamentation immediately begins.

In the first six variations (of 24 total), the vast harmonic potential of the theme is explored, with much pianistic brilliance and exquisite orchestral coloring. Then, a surprise awaits us in Variation 7: the “Dies irae” (Day of wrath) chant from the Requiem Mass suddenly appears. Rachmaninoff was positively obsessed with this melody, which he quoted in so many of his works. (Here,

the “Dies irae” can be heard in the piano while the orchestra plays the Paganini theme.) But what is this gloomy theme doing in this sparkling virtuoso composition? Quite simply, Rachmaninoff discovered that these two melodies “worked” together, that is, they could be combined with one another, and he wanted to elaborate on that fortunate discovery. The “Dies irae” theme dominates the next four variations, bringing into relief what one commentator has called the “sinister” aspects of the Paganini theme. (After all, wasn’t he called “the Devil’s violinist” in his own day?)

and intensely chromatic; program annotator Michael Steinberg wrote of this variation: “It is like making your way, hands along the wall, through a dark cave.” Ultimately, we do find our way out, emerging to the sunshine in Variation 18, which has one of Rachmaninoff ’s greatest melodies, derived from Paganini by simple inversion every rising interval in the theme is replaced by a falling one and vice versa and changing the mode from minor to major. This slow variation marks the emotional high point of the Rhapsody. What follows is a return to a more basic

Variation 18 ... has one of Rachmaninoff’s greatest melodies, derived from Paganini by simple inversion ... and changing the mode from minor to major.

A new section begins with Variation 11, a dreamlike cadenza that serves as a transition to Variation 12, an elegant Tempo di Minuetto. Until now, the music has been moving in duple meter (two beats per measure); as it changes to triple (three beats), Rachmaninoff gives the theme a new physiognomy, mixing elements of the minuet, the waltz, and the lyrical character piece. The tempo speeds up and the succeeding variations present a variety of moods and characters, from dramatic and agitated to light and nimble. Variation 17 is mysterious

form of the theme, one in which the original jumps of a fifth are again prominent. Having thus reconnected with Paganini, Rachmaninoff heads for the finish line, with a grandiose development in which the initial duple meter returns as a march. A final flourish ends the composition with a witty masterstroke, but not before the “Dies irae” theme is recalled one last time.

— Peter Laki

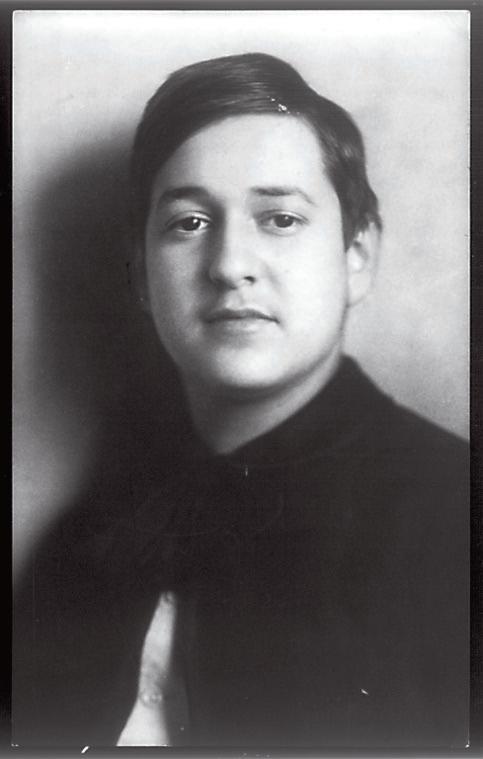

by Borys Liatoshynsky

BORN : January 3, 1895, in Zhytomyr, Russia (now Ukraine)

DIED : April 15, 1968, in Kyiv

▶ COMPOSED : 1955

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : November 11, 1955, in two simultaneous performances by the Ukrainian State Orchestra and Konstantin Simeonov in Kyiv, and by the Concert Orchestra of Soviet Radio and Television with Yuri Silantiev in Moscow

▶ This performance marks the first presentation of Liatoshynsky’s Grazhyna by The Cleveland Orchestra.

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, drums, cymbals, tam-tam, xylophone), harp, and strings

▶ DURATION : about 20 minutes

BORYS LIATOSHYNSKY WAS BORN and raised in Zhytomyr, 85 miles west of Kyiv. At age 18, he moved to the capital to study law at Kyiv University and to undertake private composition lessons with famed composer and pedagogue Reinhold Glière. When the Kyiv Conservatory opened its doors in 1913 under Glière’s direction, Liatoshynsky followed his professor to the institution. The opening of the conservatory allowed Ukrainian composers to pursue their art in Ukraine, rather than seeking education and employment in nearby capitals such as Vienna, Prague, or Moscow. While this made it harder for Ukrainian composers to be absorbed into the musical histories of other places, it also meant the

formation and recognition of a distinctly Ukrainian school of composition.

Liatoshynsky completed his studies and began teaching at the Kyiv Conservatory in 1919, where he would remain until his death in 1968. Widely considered to be the father of contemporary Ukrainian music, Liatoshynsky taught generations of Ukraine’s most important composers during his time at the Conservatory, including Ukraine’s most widely known living composer, Valentyn Sylvestrov. Each of these young musicians resisted the edicts of Socialist Realism in their own individual ways, and the diversity of their music is a testament to Liatoshynsky’s pedagogy.

From 1922–25, Liatoshynsky was head of the Ukrainian Association of Contemporary Music and president of the Ukrainian Composer’s Union from 1939–41. Unlike many of his predecessors, Liatoshynsky only worked outside of Ukraine for short periods, including when he was a professor of orchestration at the Moscow Conservatory from 1935–44. (In 1941, due to the threat of the German army, he was evacuated from Moscow with his colleagues to the Saratov Conservatory.)

Liatoshynsky’s musical output reflects the turbulence of the first half of the 20th century in which he lived and worked. His earliest pieces show the influence of symbolism and Impressionism, while in the 1920s, he entered his most free and distinctive creative period

in which he experimented with rejecting tonal harmony. Repressive policies under Stalin in the 1930s caused the composer to simplify his style, returning to more traditional genres and neoromantic tonalities. Over his career, Liatoshynsky wrote in nearly every genre, including chamber music, opera, lieder, film music, and perhaps most importantly, five symphonies, of which the third has begun to enter the canon.

In 1955, Liatoshynsky composed his symphonic ballad Grazhyna. Dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the death of Polish national poet Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855), it is inspired by the author’s 1823 narrative poem of the same name, which describes the exploits of the mythical Lithuanian chieftainess Grazhyna. The composer provided the following program note at the work’s premieres in Moscow and Kyiv:

… The ancient Neman river carries its waters calmly and majestically. On its shore, the ruins of an ancient castle are bathed in moonlight. A song about the feat of Princess Grazhyna wails from afar.

During the feudal wars, the ruler of the castle, Prince Lytavor, brings the Teutonic Knights to his country, intending to reach an agreement with their order for a joint campaign against another Lithuanian principality. Grazhyna regards this as a betrayal of the motherland.

Night. The castle is sleeping. Taking advantage of the prince’s absence, Grazhyna insults the envoys and the angry Teutonic knights attack the castle. The princess in

Lytavor’s armor leads the Lithuanian regiments against the enemy, but is mortally wounded in the battle. Lytavor realizes his guilt before his native land and leads the Lithuanians in a decisive offensive. The crusaders are defeated, but Grazhyna dies and her funeral processes to the castle. According to the old custom, her body is burned. Atoning for his guilt before his homeland, Lytavor enters the flames and burns together with Grazhyna, purifying himself from betrayal and shame by self-sacrifice.

… The ancient Neman carries its waters calmly and majestically. A song about the courageous and beautiful Grazhyna wails from afar.

The music mirrors this program with Liatoshynsky’s characteristic sensitivity. The work is framed by solemn and contemplative music that features chromatic runs in the violas and a slow, plaintive melody in the English horn. The introduction of Prince Lytavor can be heard in the first significant tempo change and the entry of an upwardly striving melody characterized by martial rhythms, brass, and ascending strings. Yet a restrained and lyrical melody in the strings interrupts his aspirations. Beginning from the registral heights of Lytavor’s theme, the music of Grazhyna slowly descends by sequence. Accompanied by harp, her music offers a counterweight to the impulsive ambition of the prince. Liatoshynsky recounts the ensuing drama with musical allusions to battle fanfares in the brass and heavy

use of percussion and to loss, with mournful, reflective melodies. In the depiction of Lytavor’s self-immolation on Grazhyna’s funeral pyre there are allusions to Brünnhilde’s redemptive sacrifice at the close of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. Liatoshynsky’s ballad closes as it began, the forlorn melody of the English horn singing the fate of the heroine.

Liatoshynsky’s choice of text is revealing. Mickiewicz’s Grazhyna, along with his Pan Tadeusz, Dziady (the German translation of which formed the inspiration for Mahler’s Todtenfeier) and Konrad Wallenrod, helped stimulate national uprisings against the imperial powers that had divided and destroyed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795. The poet himself was sentenced to five years in exile for championing independence from the Russian Empire in his home region. In 1955, Liatoshynsky had also recently suffered censorship at the hands of Soviet authorities in Moscow. Forced to withdraw his Third Symphony from performance in 1951, the composer only managed to produce an appropriate revision of the work with its title “Peace will defeat war” removed four years later.

Liatoshynsky’s musical rendering of Mickiewicz’s allusions to Russian imperialism allows the fictional Grazhyna to point a damning finger at cultural suppression that remains salient today.

— Leah Batstone

Leah Batstone is a musicologist and visiting scholar at the Jordan Center at New York University. She is also the founder and creative director of the Ukrainian Contemporary Music Festival, which takes place each spring in New York City.

by Igor Stravinsky

BORN : June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov), Russia

DIED : April 6, 1971, in New York City

▶ COMPOSED : ballet, 1909–10; suite, 1919

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : June 25, 1910, at the Paris Opera, with the Ballets Russes and Gabriel Pierné conducting the Colonne Orchestra

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE : The Orchestra first performed the 1919 suite on February 12, 1925, conducted by the composer.

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, xylophone), piano, celesta, harp, and strings

▶ DURATION : about 20 minutes

SERGEI DIAGHILEV ’S PARIS -BASED Ballets Russes was one of the greatest dance companies in history. Diaghilev, the director, combined the soul of a brilliant artist with the mind and skills of a shrewd businessman. He was committed to creating exciting and innovative productions and discovered or worked with many of the most creative artists in the city dancers, choreographers, painters, and composers. The scores created for him included works by Debussy, Ravel, Prokofiev, and Falla. Musically, however, Diaghilev never made a more sensational nor more fruitful discovery than when he engaged the 27-year-old Igor Stravinsky in 1909

to write music for Michel Fokine’s new ballet for the next season, The Firebird. It was the start of a long collaboration that was to give the world a series of groundbreaking scores Pétrouchka, The Rite of Spring, Les noces, Mavra, and Apollon musagète which ended only with Diaghilev’s death in 1929.

For many years, there had already been a great affinity between Russia and France. A political alliance between the two countries had brought Russia closer to France, while France had always been a strong presence in Russia (where French had long been the language of the educated classes). At the same time, the geographical distance and the difference

Firebird and the evil ogre Kashchei were combined in an ingenious plot, which scholar Eric Walter White summarized in his book on Stravinsky as follows:

in cultures meant that Russian things seemed to have an exotic flavor in the eyes (and ears) of the French. Both Debussy and Ravel admired and were influenced by the music of the 19thcentury Russian masters Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov (the latter of whom was Stravinsky’s teacher).

To create a story of an appropriately exotic flavor, Fokine used several Russian fairytales within the scenario of The Firebird. The stories of the beneficent

A young Prince, Ivan Tsarevich, wanders into Kashchei’s magic garden at night in pursuit of the Firebird, whom he finds fluttering round a tree bearing golden apples. He captures it and extracts a feather as forfeit before agreeing to let it go. He then meets a group of 13 maidens and falls in love with one of them, only to find that she and the other 12 maidens are princesses under the spell of Kashchei. When dawn comes and the princesses

have to return to Kashchei’s palace, Ivan breaks open the gates to follow them inside; but he is captured by Kashchei’s guardian monsters and is about to suffer the usual penalty of petrifaction, when he remembers the magic feather. He waves it; and at his summons the Firebird appears and reveals to him the secret of Kashchei’s immortality (his soul, in the form of an egg, is preserved in a casket). Opening the casket, Ivan smashes the vital egg, and the ogre immediately expires. His enchantments dissolve, all the captives are freed, and Ivan and his Tsarevna are betrothed with due solemnity.

For all its Russian influences, Stravinsky’s first ballet also shows a remarkable degree of individuality. In fact, the orchestration reveals the hand of a true

For all its Russian influences, Stravinsky’s first ballet also shows a remarkable degree of individuality.

young master for Stravinsky knew how to draw the most spectacular effects from his enormous orchestra.

It is little wonder, then, that The Firebird remained Stravinsky’s most popular work throughout his long life. The ballet was a resounding success at the Paris premiere in 1910, and Stravinsky himself conducted more than a hundred performances mostly in the

form of three suites he drew from the complete score, one in 1911, another in 1919, and a third in 1945.

The 1919 suite heard in tonight’s performance is in five movements. The mysterious Introduction leads into the glittering Dance of the Firebird, followed by a slow and solemn Khorovod (round dance) of the captive princesses, based on a melancholy Russian folk song first played by the oboe.

The Infernal Dance of King Kashchei is next, started by a fast timpani roll and dominated by a syncopated motif that arises from the lower registers (bassoons, horn, tuba) and is gradually taken over by the entire orchestra. This is the longest movement in the suite, including a lyrical countersubject symbolizing the plight of Kashchei’s prisoners. The “infernal dance” music returns, concluding with a wild climax.

As a total contrast, the Firebird’s Berceuse (Lullaby) is a delicate song for solo bassoon. The lullaby leads directly into the Finale (the wedding of Ivan Tsarevich and the Princess), where the first horn introduces what is probably the most famous Russian folk song in the ballet. This beautiful melody grows in volume and orchestration, bringing the music to its final culmination point.

Although his style and artistic outlook changed considerably (and repeatedly) during the intervening decades, even at the end of his life, Stravinsky had every reason to like the work that had catapulted him to fame at the age of 28.

Peter Laki

Join us for a magical evening to benefit The Cleveland Orchestra’s summer home. You’ll enjoy a festive dinner party complete with seasonal summer cocktails and friends in Knight Grove. Then you’ll be treated to a concert by Leslie Odom, Jr., and your Cleveland Orchestra. Proud Presenting Sponsor of the Blossom Summer Soirée

OCTOBER 22 MICHAEL FEINSTEIN’S TRIBUTE TO TONY

Learn more and reserve your tickets at clevelandorchestra.com/soiree

NOVEMBER 19

DECEMBER 3

DIDONATO WITH KINGS RETURN

FEBRUARY 11

Thursday, July 25, 2024, at 7 PM

César Franck (1822–1890)

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957)

Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904)

Le Chasseur maudit 15 minutes (The Accursed Huntsman)

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 25 minutes

I. Moderato nobile

II. Romance: Andante

III. Finale: Allegro assai vivace

James Ehnes, violin

INTERMISSION 20 minutes

Symphony No. 6 in D major, Op. 60 40 minutes

I. Allegro non tanto

II. Adagio

III. Scherzo (Furiant): Presto

IV. Finale: Allegro con spirito

Total approximate running time: 1 hour 40 minutes

Thank you for silencing your electronic devices.

“My dear Mr. [Fritz] Simrock!” Antonín Dvořák wrote to his publisher in 1880. “In brief, I would like to inform you that I have written my new symphony and have completed its instrumentation. … I have made great efforts to produce this, a work capable of great things, and it has also given me much pleasure.” Still riding high after the success of his recent Czech-flavored symphonic works, the young composer was eager to present something new to the public. The Sixth Symphony originally published as his Symphony No. 1 soon met and exceeded Dvořák’s expectations; it was greeted with rapturous applause in Prague before receiving performances throughout Europe. Though perhaps less familiar today than his final three symphonies, the work shows Dvořák in his sunniest, most carefree mode and hints at the successes that were yet to come.

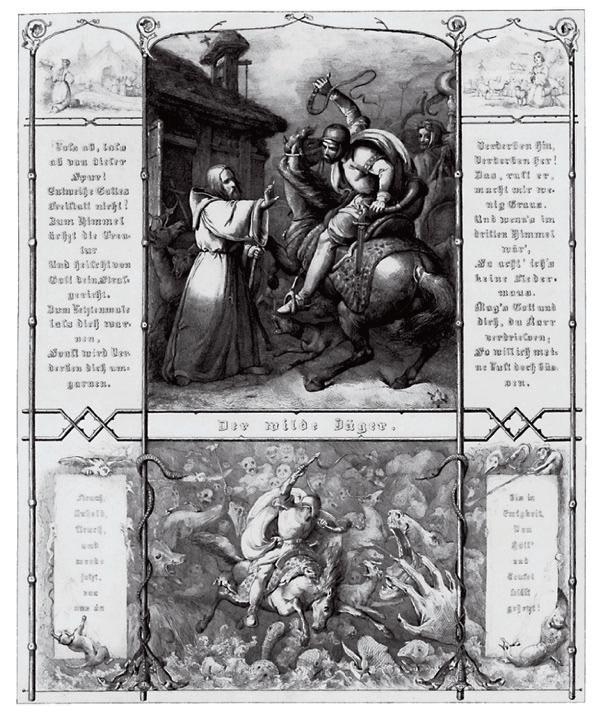

Tonight’s program led by Czech conductor Petr Popelka contrasts this youthful symphony with late-period works by César Franck and Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Composed seven years before his untimely death, Franck’s symphonic poem Le Chasseur maudit (The Accursed Huntsman) revels in the full palette of the Romantic orchestra and the era’s penchant for supernatural themes. Franck based the work off a ballad by Gottfried August Bürger, which spins the tale of a German count who tempts fate by hunting on a Sunday morning. Despite the warnings of pious passersby, the count ultimately faces the infernal consequences.

Five decades later, Korngold tapped a very different source of inspiration while composing a violin concerto his own work, in fact. Having fled a lucrative European career in 1938 after the Nazis invaded Austria, Korngold experienced renewed success in Los Angeles as a Hollywood film composer. His Violin Concerto played tonight by James Ehnes is a concerted effort to bridge the worlds of “high” and “low” art, embedding several musical themes from his film scores within the time-honored framework of the classical concerto. Though critics were mixed at its 1947 premiere one reviewer called it “more corn than gold” audiences responded immediately to the concerto’s lush orchestration and dazzling virtuosity, and the work has remained a beloved staple of the repertoire to this day.

— Kevin McBrien

by César Franck

BORN : December 10, 1822, in Liège, Belgium

DIED : November 8, 1890, in Paris

▶ COMPOSED : 1882

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : March 31, 1883, by the Société Nationale de Musique in Paris, conducted by Édouard Colonne

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE : December 18, 1924, with Music Director Nikolai Sokoloff conducting

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 cornets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (chimes, cymbals, triangle, bass drum), and strings

▶ DURATION : about 15 minutes

THE ACCURSED HUNTSMAN and the Flying Dutchman could have been brothers. Both were born of the imagination of German Romanticism, which was fascinated with ghosts and supernatural punishment.

The story of the Dutchman, the hero of Wagner’s first operatic masterpiece, was first told (albeit with an ironic twist) by Heinrich Heine in the 1830s. The Huntsman appears in a ballad by Gottfried August Bürger (1747–1794), who lived during the Classical era of Goethe and Schiller but must be counted among the precursors of the Romantic generation. Best known for his fantastic Adventures of Baron Münch-

hausen, Bürger also penned a number of ballads that were enormously popular during the 19th century first and foremost, Lenore, about a young woman who blasphemes against heaven when her fiancé does not return from war; his ghost finally appears in the middle of the night and takes her on a deadly ride. The ballad of the Huntsman (the German title is Der wilde Jäger, or “The Wild Hunter”) is another spooky story about a horseback ride from (and into) hell. Its evil protagonist is a Rheingraf, or a count from the Rhineland, who rides into the countryside one Sunday morning while the pious are in church. He sees two other riders on the road; one urges

the day of the Last Judgment, with no prospect of pardon (unlike the Dutchman, who is saved by the sacrifice of a loving woman).

him to follow the path of virtue, while the other incites him to crime. Without hesitation, the Count obeys the second rider, destroying the poor peasants’ crops and killing off their cattle. His punishment is to keep on riding, without respite, right up until

Wild rides lent themselves exceptionally well to musical treatment during the Romantic era: examples abound from Schubert’s Erlkönig to Wagner’s Die Walküre to Tchaikovsky’s orchestral ballad The Voyevoda. The diabolical element was also extremely popular,

with Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique and The Damnation of Faust, Liszt’s Totentanz and Mephisto Waltzes, and Saint-Saëns’s Danse macabre. César Franck, thus, was in excellent company when he wrote Le Chasseur maudit. He may have been turned on to Bürger’s ballads by his former pupil Henri Duparc, who had written an orchestral Lenore in 1875.

At age 60, Franck was best known for his sacred music, especially his oratorio

Les Béatitudes, a celebration of the divine, and as remote from anything hellish as possible. (His most famous works, the Symphony in D minor, the Violin Sonata,

which depends at least as strongly on its verbal music as it does on its plot. (Franck must have read the poem in the original language, as his family was of German origin, and according to biographer Léon Vallas, “the French musician-to-be spoke German with his mother.”)

The wild ride becomes wilder and wilder, until it suddenly stops as the mysterious tremolos of the violas announce the divine judgment visited on the Count. He tries to blow his horn again, but he cannot produce a sound like before. (A note played by four muted

Wild rides lent themselves exceptionally well to musical treatment during the Romantic era. ... [Franck] embraced this arch-Romantic subject with great relish, indulging an aspect of his personality that he did not allow to come to the fore too often.

and the String Quartet, were all as yet unwritten.) The venerable organist and professor embraced this arch-Romantic subject with great relish, indulging an aspect of his personality that he did not allow to come to the fore too often. The contrasting sounds of hunting horns and church bells held great dramatic potential, which Franck exploited to great effect in his introduction.

The “riding rhythm,” a Valkyrie-like 9/8 time with a characteristic dotted pattern, is Franck’s response to the strong rhythmic drive in Bürger’s ballad,

horns fortissimo is followed by another one, played piano by a single instrument.)

A sinister slow section follows, with ominous brass chords and string tremolos. When the ride resumes, it takes on a positively diabolical character. At the climactic moment (the tempo has now accelerated to “Quasi presto”) the church bells start ringing again, and the Count disappears into the distance, forever pursued by the implacable demons.

— Peter Laki

Peter Laki is a musicologist and frequent lecturer on classical music. He is a visiting associate professor of music at Bard College.

by Erich Wolfgang Korngold

BORN : May 29, 1897, in Brno, Austria-Hungary (now the Czech Republic)

DIED : November 29, 1957, in Los Angeles

▶ COMPOSED : 1937–39, revised 1945

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : February 15, 1947, with soloist Jascha Heifetz and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Vladimir Golschmann

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE : January 11, 1990, with violinist

Daniel Majeske and conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons (2nd doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, trombone, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, vibraphone, xylophone, glockenspiel, gong, chimes), harp, celesta, and strings, plus solo violin

▶ DURATION : about 25 minutes

WHEN ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD was 9 years old, his father Julius Korngold, the most powerful music critic in Vienna showed the boy’s first compositions to Gustav Mahler, who exclaimed: “A genius!” Mahler’s reaction was understandable. The young Korngold was a unique composing prodigy who had an immediate and instinctive understanding of the most modern musical styles of the day. He grew up to be an extremely successful opera composer his most talked-about work, Die tote Stadt (The Dead City), was written when he was 20. Yet he was equally attracted to operetta, and his involvement with new productions

of Die Fledermaus and other operettas by Johann Strauss, Jr. brought him into contact with Max Reinhardt, the foremost German stage director of the time. It turned out to be an extremely fruitful collaboration, as it was because of Reinhardt that Korngold first went to Hollywood, where he soon became a star among film composers. After the Nazi occupation of Austria, Korngold lost his original home and settled permanently in Los Angeles.

Julius Korngold, who in his seventies was forced to flee Austria and join his son in Southern California, was deeply disappointed that his son had given up “serious” composition in favor of

the movies. To his last day, Julius kept exhorting Erich to return to concert music. His advice went unheeded for years, yet towards the end of Julius’s life, his son wrote a string quartet (his third) and after Julius’s death, he returned to a project started years earlier but never completed: a concerto for violin and orchestra.

The great violinist Bronisław Huberman an old friend of the Korngold

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

career in Hollywood set a new standard for movie music with lush orchestrations and themes for individual characters and had a lasting impact on the succeeding generation of film composers, including John Williams.

family since their Vienna days had long been asking Korngold for a violin concerto. When the work was finally completed, however, Huberman found himself unable to commit to a performance date. Korngold showed the concerto to Jascha Heifetz, who learned it within a few weeks and with Huberman’s blessing proceeded to give the world premiere in St. Louis in February 1947.

At this point in Korngold’s career, the two aspects of his creative world concert and film music had become completely intertwined. His movie scores (of which the most famous are Captain Blood and The Adventures of Robin Hood) were symphonic, even operatic, in their scope. The Violin Concerto, on the other hand, owes much to Korngold’s work in the film industry. Many of the major themes were taken from his film scores, and there are moments where the instrumentation and thematic development bring back Hollywood memories.

entity in the Violin Concerto, quite independent from the screen originals. In Korngold’s personal style, elements inherited from Mahler and Richard Strauss are treated with the light touch perfected at the Warner Brothers studios. This approach brought Romantic concerto-writing to new life at a time when most modern composers and critics were ready to bury it. Korngold himself never had any doubts about the vitality of this tradition. His rich melodic invention, “spicy” harmonies that nevertheless remain firmly anchored in

The Violin Concerto ... owes much to Korngold’s work in the film industry. Many of the major themes were taken from his film scores, and there are moments where the instrumentation and thematic development bring back Hollywood memories.

The opening theme of the concerto comes from the score for a film that failed and was quickly forgotten (Another Dawn, 1937), the second from the historical movie Juarez (1939). The beautiful melody of the second-movement Romance was based on the score for Anthony Adverse (1936), for which Korngold won his first Academy Award for Best Original Score. The folk-dance theme of the last movement originated in the film adaptation of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper (1937) and became the starting point for a set of brilliant variations. These different sources form a completely new

tonality, and perfect understanding of the virtuoso violin idiom enabled him to make an important contribution to the repertoire. Yet at first, the concerto found little favor with violinists, despite Heifetz’s strong advocacy. (Heifetz recorded the work twice: once with the New York Philharmonic and once with the Los Angeles Philharmonic.) Since the 1970s, though, the concerto has enjoyed a spectacular comeback, with many new recordings and increasingly frequent concert performances all over the world.

— Peter Laki

by Antonín Dvořák

BORN : September 8, 1841, in Nelahozeves, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic)

DIED : May 1, 1904, in Prague

▶ COMPOSED : 1880

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : March 25, 1881, in Prague, with Adolf Čech conducting the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE : January 31, 1946, conducted by Music Director Erich Leinsdorf

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings

▶ DURATION : about 40 minutes

AFTER CONDUCTING a highly successful performance of Dvořák’s Third Slavonic Rhapsody (Op. 45) in Vienna, Hans Richter asked the 38-year-old Dvořák late in 1879 to write a symphony for him and the Vienna Philharmonic. Dvořák began working on August 27 of the next year, and the composition was ready by October 15. After playing through the symphony (on the piano) for Richter, Dvořák was able to report to a friend on November 23: “Richter likes the Symphony immensely and embraced me after each movement, and the first performance will be on the 26th [of December].”

However, it soon turned out that there were unexpected difficulties in the way of the performance. Richter had to postpone the premiere several times,

citing illnesses in his family and other problems. Dvořák later found out that the real reason was the presence of strong anti-Czech feelings in Vienna. There were powerful voices at the Philharmonic Society that objected to a Czech composer’s works being performed in two successive seasons, and the symphony was turned down in spite of Richter’s enthusiastic advocacy. So Dvořák offered the new symphony to his good friend Adolf Čech, who conducted the first performance in Prague on March 25, 1881. Within the next two years, the symphony was heard in Leipzig, Graz, Budapest, New York, Frankfurt, Cologne, Amsterdam, and London. In London, Richter was at last able to conduct the symphony, leading an encore presentation just three

weeks after August Manns had given the London premiere. As for Vienna, the first performance there was conducted by Wilhelm Gericke on February 18, 1883 two seasons later than originally promised.

The Sixth Symphony is a milestone in Dvořák’s artistic development. The first of his symphonies to be published and to become an international success, it is one of his finest achievements.

Despite some striking reminiscences of Beethoven and Brahms, the symphony speaks a language that is truly Dvořák’s own from beginning to end.

Through the use of a specific device called “horn fifths,” the symphony’s opening motif evokes associations with nature, more specifically, the forest as seen by Romantic artists. All the melodic material of the first movement is in some way related to this opening. The movement is in regular sonata form, with distinct development and recapitulation sections, but instead of modulating to the dominant key of A major, the exposition chooses a softer-sounding tonality B minor as its goal. Throughout the movement, idyllic lyrical

characterized by an alternation of double and triple meter. Dvořák’s immediate model was probably from Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride, in which three groups of two beats each are followed by two groups of three beats each. Dvořák’s Furiant combines this rhythmic idea with highly chromatic harmonic writing; the symbiosis of these two disparate elements gives the movement its unique character. A central Trio section is much plainer in both harmony and rhythm; here the melody is given to the solo piccolo.

The Sixth Symphony is a milestone in Dvořák’s artistic development. The first of his symphonies to be published and to become an international success, it is one of his finest achievements.

sections alternate with more agitated and grandiose passages. Dvořák leads us to believe that he will close the movement in the lyrical mode in a quiet pianissimo when suddenly, four measures of noisy forte break in and provide a very different kind of ending.

The second-movement Adagio is based on a soulful theme, first played by the violins with counterpoint on the oboe. Time and again, the music becomes more dramatic, but the main theme never stays away very long and returns to close the movement with special instrumentation (wind instruments only).

The third-movement Scherzo has the subtitle “Furiant,” a Czech folk dance

Like the opening Allegro, the fourth-movement Finale is an example of how a long and complex movement can be built from a single melodic idea. Upon examination, the movement’s two main themes are closely related. The movement has an irresistible drive that never lets up.

There is a dazzling Presto section at the end. In it, the rushing eighth notes of the violins serve as a counterpoint to the main theme, whose notes, in a gesture almost like laughter, are separated by rests. Finally, the brass transforms the theme into a kind of hymn, and the symphony ends with a climax, radiant and grandiose.

Peter Laki

Thursday, August 15, 2024, at 7 PM

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Symphony No. 35 in D major, 20 minutes K.385, “Haffner”

I. Allegro con spirito

II. Andante

III. Menuetto

IV. Presto

INTERMISSION

Anton Bruckner (1824–1896)

20 minutes

Symphony No. 4 in E-flat major, 70 minutes “Romantic” (1878/80 version, ed. Benjamin M. Korstvedt)

I. Bewegt, nicht zu schnell (With motion, not too fast)

II. Andante quasi Allegretto

III. Scherzo: Bewegt (With motion)

IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell (With motion, but not too fast)

Total approximate running time: 1 hour 50 minutes

Thank you for silencing your electronic devices.

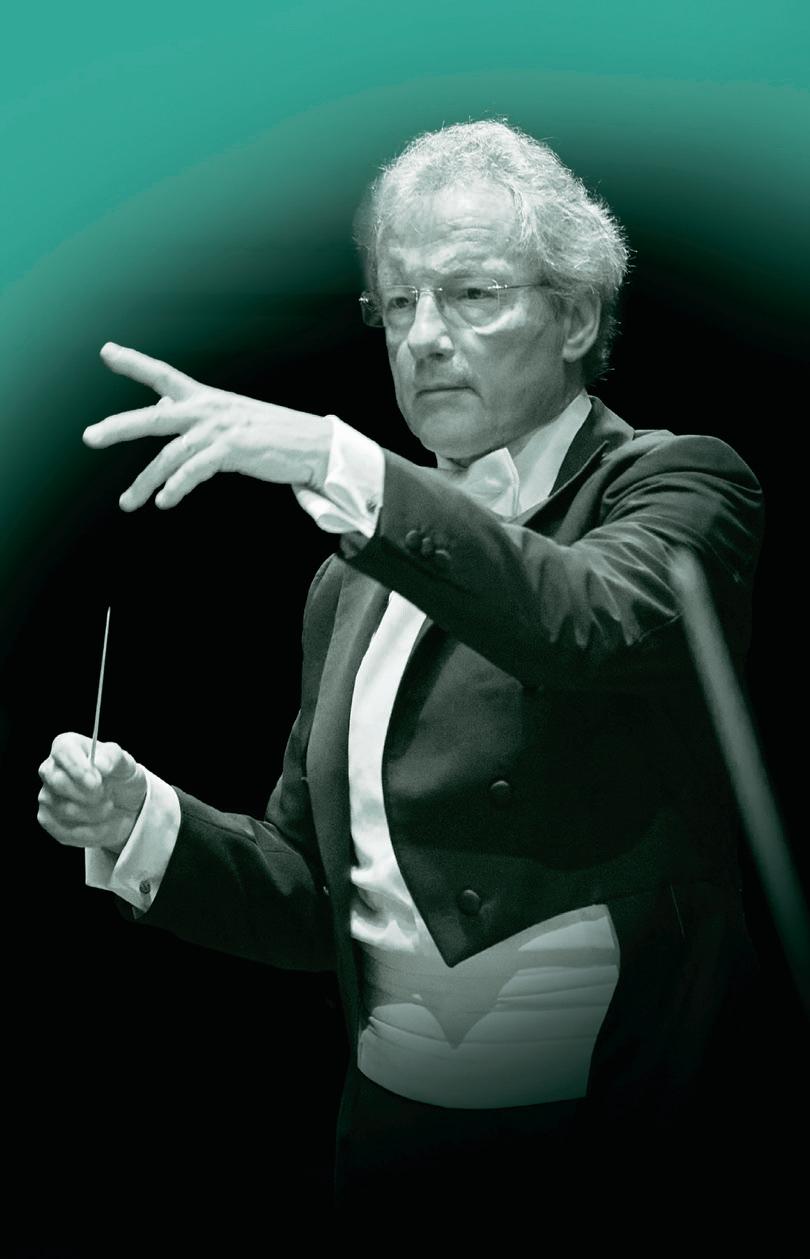

by Franz Welser-Möst

This year, orchestras all over the world are honoring the bicentennial of Anton Bruckner. As part of the celebration on September 4, 2024 what would have been Bruckner’s 200th birthday I will conduct The Cleveland Orchestra in his Symphony No. 4 just yards away from where he was born, in Ansfelden, Austria. In an early commemoration of the anniversary, we also present the Fourth Symphony, the “Romantic,” this evening.

While Bruckner’s music has become more popular over the past decades, he was misunderstood for much of his life. He was a simple man who was dedicated to the church, yet he was also a genius whose symphonies were so expansive and expressive they are often called “cathedrals in sound.” This term might give the false notion that his music is merely religious in nature, but there’s so much more. His works can be obsessive, extreme, sentimental, highly emotional, sad, or aggressive. Sometimes he seems to be screaming out from the pages of the score, and at others he anticipates 20th-century modernism.

Like Bruckner, I was also born in Upper Austria and came of age in the Catholic Church: He was a choir boy at St. Florian Monastery, and I was an altar boy for eight years. When you’re raised in that environment, you can’t escape Bruckner you might say that his music is in my blood!

I first tackled a Bruckner symphony, his Fifth, at age 24, and it raised for me this question: If he was so enamored with the Catholic Church, why did he decide to focus on composing symphonies and not masses or other liturgical music? I didn’t have an answer then, and I don’t have one now. Yet, visiting the Baroque Marble Hall and Basilica at St. Florian, where he spent much of his life and is interred beneath its organ, you can see how he kept one leg in the music of J.S. Bach and Palestrina. The other leg was in the intensely dramatic world of Richard Wagner. Perhaps the complexity of his approach, encompassing these contrasting, almost oppositional influences, could only be expressed through symphonic form.

by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

BORN : January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

DIED : December 5, 1791, in Vienna

▶ COMPOSED : 1782–83

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : March 23, 1783, in Vienna, with the composer conducting

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE : December 18, 1930, conducted by Music Director Nikolai Sokoloff

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

▶ DURATION : about 20 minutes

THE MEMBERS of the Haffner family were good friends of the Mozarts in Salzburg. Sigmund Haffner the Elder (1699–1772) had been a wealthy merchant and mayor of the city, in whose house a great deal of music was made, with both Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart frequently participating. The relations continued after the mayor’s death, and when his daughter Maria Elisabeth Haffner (1753–1784) was going to be married in 1776, Mozart was asked to write some festive music for the wedding. The “Haffner” Serenade (K. 250) was so successful that six years later, when another cause for celebration arose, the composer received another commission from the family. This time the occasion was Sigmund Haffner the Younger’s (1756–1787) elevation to nobility.

In the meantime, Mozart had left his native city and moved to Vienna, where his fame was rapidly advancing. When the request from Salzburg reached him in July 1782, his opera The Abduction from the Seraglio had just been premiered. He was busy arranging selections from it for wind ensemble (in those pre-copyright days, if he didn’t work fast, someone else could beat him to it and secure the profits!). In addition, the composer’s wedding with Constanze Weber was imminent (August 4) and he was preparing to move to new quarters. In these circumstances, the creation of the new symphony went slower than father Leopold anxious for the work to arrive in time for the festivities might have wished. Nevertheless, Mozart seems to have managed to send the score to Salzburg

before the end of August, since on the 24th of that month he wrote to his father: “I am delighted that the symphony is to your taste.”

We can tell from the music that the symphony had originally been intended as a second “Haffner” Serenade, to be performed outdoors. Its tone is bright and exuberant, without any dramatic outbursts or the slightest trace of sadness and gloom. The music sparkles with joy, and every bar brings new pleasures. The first movement’s opening

theme with its wide octave leaps in unison is quite an exceptional melody and is handled in a most original fashion. It is, in fact, the only significant melodic material in the movement and is reintroduced when we would expect a second theme, with the only difference being that it is now played softly and treated contrapuntally. Throughout the symphony, there is hardly a moment when we don’t hear at least the rhythm of this first theme. The opening movement’s development section invests the melody with yet another character, and then at the end of the recapitulation, a slight change from the original

exposition is featured, as a mock-tearful farewell gesture.

The second movement, marked Andante, is less slow than many second movements. Its tone, not surprisingly after what we know about the symphony’s genesis, is that of an easygoing,

woodwinds only. There is a brief coda, or musical “postscript,” which repeats the soft-loud scheme of the main melody a final time, before the jubilant ending played by the full orchestra.

The “Haffner” Symphony was an instant success in Vienna and else-

[The symphony’s] tone is bright and exuberant, without any dramatic outbursts or the slightest trace of sadness and gloom. The music sparkles with joy, and every bar brings new pleasures.

peaceful serenade. The exquisite melodies flow one after another, and each has a distinctive touch some detail of rhythm, harmony, or orchestration that no other composer could have invented.

The brief and concise third-movement Minuet is based on a fanfare motif in which the trumpets and timpani play an important part. The movement’s Trio section, whose melody is harmonized in the so-called “horn” style (using thirds, fifths, and sixths), seems to have been inspired by popular Ländler tunes.

Mozart wrote that the fourth-movement Presto finale should go “as fast as possible.” It is an extremely lively piece based on a simple tune, developed and varied in a most ingenious way. It starts softly on the strings, but the entire orchestra with trumpets and timpani soon joins in. The second theme, by contrast, is scored for strings and

where. As Mozart wrote to his father after the Viennese premiere (which, according to the custom of the day, opened with the first three movements of the symphony and closed with the Finale with piano music, improvisations, and vocal selections in between):

The theater could not have been more crowded and ... every box was full. But what pleased me most of all was that His Majesty the Emperor [Joseph II] was present and, goodness! how delighted he was and how he applauded me! It is his custom to send money to the box office before going to the theater; otherwise I should have been fully justified in counting on a larger sum, for really his delight was beyond all bounds. He sent 25 ducats.

— Peter Laki

Peter Laki is a musicologist and frequent lecturer on classical music. He is a visiting associate professor of music at Bard College.

by Anton Bruckner

BORN : September 4, 1824, in Ansfelden, Upper Austria

DIED : October 11, 1896, in Vienna

▶ COMPOSED : 1874–80, revised 1886–88

▶ WORLD PREMIERE : February 20, 1881, with Hans Richter conducting the Vienna Philharmonic

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE : April 12, 1945, led by Music Director Erich Leinsdorf

▶ ORCHESTRATION : 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings

▶ DURATION : about 70 minutes

TWO CENTURIES have now passed since the birth of Anton Bruckner September 4 marks his 200th anniversary but posterity is still coming to terms with the significance of his legacy as one of the great symphonists. Bruckner had to wait until the public premiere of his Fourth Symphony in 1881 to enjoy his first real taste of success, following years of bitter rejection in his adopted city of Vienna. Possibly to enhance its chances of being accepted, the composer allowed the Fourth to be published with the official subtitle “Romantic,” and listeners have as a result been introduced to the work as the epitome of Romanticism in symphonic music. Even more, Bruckner,

in an uncharacteristic move, supplied brief programmatic descriptions of the music. These conjure images of medieval knights riding forth from a city, spurned love, a hunt complete with a picnic interlude, “woodland magic,” and the like.

Yet these “explanations” for his musical thoughts are misleading if they encourage us to expect a program symphony along the lines of other late Romantic composers. They in fact postdate his composition of the music. Such postscripts, with their romanticizing glosses on an abstract concert score had become trendy at the time. It’s safer to speculate that they represent the composer’s understandable attempt to

sell a kind of music that was undeniably out of sync with his era.

Bruckner’s symphonies create a sense of sonic spaciousness and awe that is unique to him. Robert Simpson, one of the most perceptive English commentators on Bruckner, argues that the “flight from reality” and “emotional egotism” characteristic of 19th-century Romanticism actually held little attraction for Bruckner that his music is indeed profoundly anti-Romantic insofar

as it envisions a musical process that differs from the patterns of tension and release so crucial to “dramatic” music.

Much has been made of Bruckner’s idolization of Richard Wagner. Yet the dramatic side of the equation in Wagnerian opera seems barely to have registered for Bruckner. What left its mark on him

was, above all, Wagner’s expanded sense of musical time. (After seeing Wagner’s Ring cycle in the theater, Bruckner famously expressed puzzlement as to why the heroine had been set on fire at the end entirely missing the dramatic significance Wagner had so painstakingly developed over the course of four operas.)

The Brucknerian aesthetic contrasts sharply with Romantic drama, instinctively tending toward a more spiritual contemplation. As Simpson writes, Bruckner’s symphonies illustrate a quest

score that should be performed is a matter of ongoing debate for many of his symphonies nowhere more so than with the Fourth, whose finale alone exists in three separate versions.

A brief summary of the issue might be helpful. Although Bruckner initially composed the Fourth in 1874, he kept this version from being performed in part due to the humiliation he experienced with the disastrous premiere of his Third Symphony in 1877. This initial version remained unheard during his

With the opening of the first movement, instead of the Romantic imagery of a knight ... setting out at dawn on noble quests in this “heroic” key of E-flat major, Bruckner’s music intimates an epic that is far more elemental — even cosmic — in its pared-down majesty. —

toward an “essence crystallized, the sky through which the earth moves.”

The Fourth Symphony marks a major milestone in the composer’s attempt to establish a symphonic design capable of sustaining his innovative musical thought. As Bruckner groped his way through uncharted terrain, the Fourth naturally underwent extensive revisions. In fact, it represents the most convoluted revision history of all his symphonies and this for a composer for whom variant editions of a work, often involving substantial changes, became the norm. The result is that identification of the “authentic” final

lifetime and was not published until 1975. Then, from 1878 to 1880, he reworked the material of the first two movements and rewrote both the Scherzo and the Finale (including a substantially different rewrite of the latter that he then decided to reject). With this, he arrived at the version that was successfully premiered, under Hans Richter’s baton, in February 1881. This, more or less, with some subsequent tinkering, provides the basis for the most frequently performed version of the work nowadays.

Yet after a series of rejections from publishers, Bruckner desperate to have his much-misunderstood music officially

in print finally entered into a contract for publication of the Fourth in the late 1880s and embarked on yet another series of revisions he began in 1886 or 1887. At this point, to prepare the first printed edition, he collaborated with his students Ferdinand Löwe, Franz Schalk, and Joseph Schalk all of whom became key participants in the history of Bruckner’s symphonic revisions.

This “1888 edition” became the standard for performances until 1936, when the controversial Bruckner scholar Robert Haas published his edition based on the 1880 version. The source of controversy here concerns the extent to which changes later introduced by Bruckner’s collaborators may have distorted the composer’s original ideas in an effort to make his music more palatable to their contemporaries for example, by introducing more seamlessly “Wagnerian” orchestrations.

The American musicologist Benjamin M.Korstvedt has published critical editions of various stages of the Fourth Symphony’s revisions. For this concert, Music Director Franz Welser-Möst has chosen to program the second version of the Fourth Symphony (from 1878/80) in the critical edition Korstvedt prepared for the New Anton Bruckner Complete Edition published in 2018 by the International Bruckner Society. Welser-Möst believes this version presents a compelling (and perhaps clearer) snapshot of the composer’s original vision.

Through its combination of readily

attractive elements and impressive architecture, the Fourth has maintained its status at the forefront of Bruckner’s most popular works. Curiously, up to this point all of Bruckner’s major scores sacred choral compositions and five symphonies (including two not listed or numbered within his canon of nine) had been anchored in minor keys. The Fourth Symphony inaugurates a series of major-key symphonies that would extend through No. 7.

Yet Bruckner’s treatment of tonality, in which he lays out enormous spans of time and majestic blocks of sound, transcends the classical polarity of major-minor. Indeed, the Fourth Symphony’s much-admired opening acquires something of its mysterious power by incorporating a minor-key inflection into the horn call’s otherwise simple harmonic palette, all set against a pregnant backdrop of trembling strings.

With the opening of the first movement, instead of the Romantic imagery of a knight (such as Wagner’s Lohengrin) setting out at dawn on noble quests in this “heroic” key of E-flat major, Bruckner’s music intimates an epic that is far more elemental even cosmic in its pared-down majesty. The prominence of the horn is a hallmark of the rest of the symphony the instrument appears almost as a protagonist in its own right. At the same time, the massive summoning of the ensemble for the second part of the opening theme group is shaped by a duplet-followed-by-triplet pattern that also functions as a unifying device across

the symphony’s span. This so-called “Bruckner rhythm,” whose origins are likely related to his fascination with numerology and his obsessive counting of prayers and objects, recurs as a rhythmic signature throughout the composer’s career.

With the second, rustically flavored theme group comes a counter to the epic, setting up a contrast between nature viewed from an enormous, cosmic distance and from close-up, down in the valley, as it were. This sense of perspective, in fact, applies to the Fourth as a whole. Bruckner expands the dimensions of Classical sonata form, particularly in the resonant sounding of a chorale-like passage in the movement’s development section. New perspectives accompany the recapitulation, signaled by the flute’s counter-commentary against the opening horn call. And Brucknerian proportions reign supreme in the movement’s superbly paced coda.

The rest of the Fourth continues to carry out the implications of this vast opening design. Bruckner establishes a solemnly measured gait in the marchlike Andante, developing this C-minor slow movement from three interconnected sections of material presented in succession. Its reprise extends into another enormous coda, in which the motion becomes more flowing, reaching a powerful climax and then subsiding. Characteristically, Bruckner’s use of pauses is meditative, not dramatic.

After this, the third-movement “hunting” Scherzo, with its overlapping

“Bruckner rhythms” in horns and brass, instills a rush of energy to complement the slow motion of the preceding march. Yet the Scherzo itself, in its secondary themes, as well as the innocent piping of the Trio section, juxtaposes the epic and the rustic that are twin poles of this symphony at large.

No part of the Fourth posed more difficulty for the composer than the Finale. The result, most commentators agree, is marred by uncertainties of direction that reflect his struggle to lay out a design adequate to his spacious concept a design that had to go beyond the conventions of sonata form. Yet the Finale’s titanic opening shows Bruckner at his most confident, evoking a sense of mystery similar to what we encountered at the beginning of the work. The main theme coalesces against thundering timpani, while the fundamental contrast of epic against relaxed nature returns once more in the second theme group. All of these ideas reintroduce material from the previous movements in new guises. By the time Bruckner arrives at the stunning final coda, writes Simpson, the effect is altogether different from that of “the accumulated energy of a vividly muscular process (as in the Classical symphony)” or of “the warring of emotive elements (as in the purely Romantic work)” but instead reveals “the final intensification of an essence.”

— Thomas May

Thomas May is a writer, critic, educator, and translator. A regular contributor to The New York Times, The Seattle Times, Gramophone, and Strings magazine, he is the English-language editor for the Lucerne Festival.

Director

KELVIN SMITH FAMILY CHAIR

Franz Welser-Möst is among today’s most distinguished conductors. The 2024–25 season marks his 23rd year as Music Director of The Cleveland Orchestra. With the future of their acclaimed partnership extended to 2027, he will be the longest-serving musical leader in the ensemble’s history. The New York Times has declared Cleveland under WelserMöst’s direction to be “America’s most brilliant orchestra,” praising its virtuosity, elegance of sound, variety of color, and chamber-like musical cohesion.

With Welser-Möst, The Cleveland Orchestra has been praised for its inventive programming, ongoing support of new music, and innovative work in presenting operas. To date, the Orchestra and Welser-Möst have been showcased around the world in 20 international tours together.

In the 2023–24 season, Welser-Möst was a featured Perspectives Artist at Carnegie Hall, where he lead The Cleveland Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic as part of the series, Fall of the Weimar Republic: Dancing on the Precipice.

In addition to his commitment to Cleveland, Welser-Möst enjoys a particularly close and productive relationship with the Vienna Philharmonic as a guest conductor. He has conducted its celebrated New Year’s Concert three times, and regularly leads the orchestra

at home in Vienna, as well as on tours.

Welser-Möst is also a regular guest at the Salzburg Festival where he has led a series of acclaimed opera productions, including Rusalka, Der Rosenkavalier, Fidelio, Die Liebe der Danae, Reimann’s opera Lear, and Richard Strauss’s Salome. In 2020, he conducted Strauss’s Elektra on the 100th anniversary of its premiere. He has since returned to Salzburg to conduct additional performances of Elektra in 2021 and Puccini’s Il trittico in 2022.

In 2019, Welser-Möst was awarded the Gold Medal in the Arts by the Kennedy Center International Committee on the Arts. Other honors include The Cleveland Orchestra’s Distinguished Service Award, two Cleveland Arts Prize citations, the Vienna Philharmonic’s “Ring of Honor,” recognition from the Western Law Center for Disability Rights, honorary membership in the Vienna Singverein, appointment as an Academician of the European Academy of Yuste, and the Kilenyi Medal from the Bruckner Society of America.

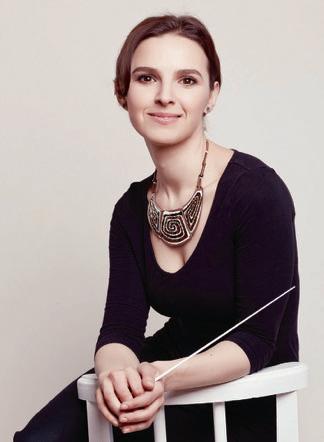

Known for her exceptional combination of precision and artistic temperament in conducting, Oksana Lyniv is a prominent figure on the international stage and ranks among the leading conductors of the younger generation.

Lyniv has been music director of the Teatro Comunale di Bologna since 2022, making her the first female chief conductor of an Italian opera house, and made history in 2021 as the first female conductor in the Bayreuth Festival’s history with her production of Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman. Following its sensational success, she committed to Bayreuth until 2024.

As a guest conductor, Lyniv collaborates with leading orchestras and opera companies worldwide, including the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, Korean National Orchestra, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Metropolitan Opera, Berlin State Opera, Royal Opera House, and Opéra National de Paris, among many others. She previously served as deputy chief conductor at the National Opera in Odesa and chief conductor of the Graz Opera and Graz Philharmonic.

Lyniv first gained international attention as a finalist in the Gustav Mahler International Conducting Competition, winning the third prize. She has been awarded several titles and prizes, including the Festival Prize of the Bavarian State Opera in 2015. In 2021,

she was honored with the Ukrainian Order of Princess Olga, and in 2022, became the laureate of the Helena Vaz da Silva European Award for raising public awareness about her cultural heritage.

Lyniv is dedicated to nurturing young musical talents. She is the founder and chief conductor of the Youth Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine (YsOU), the first and only nationwide youth orchestra in Ukraine. She also co-founded the LvivMozArt Festival in Lviv, Ukraine in 2016.

In 2022, after the outbreak of war in Ukraine, Lyniv was a co-initiator of the Music for the Future project, an evacuation music camp for young Ukrainian musicians in Ljubljana, Slovenia. She is a dedicated cultural ambassador for her country and passionately advocates for the performance of Ukrainian composers on international stages.

“One of the most admired pianists of his generation” (The New York Times), Inon Barnatan has established a unique and varied career, equally celebrated as a soloist, curator, and collaborator.

As a soloist, Barnatan is a regular performer with many of the world’s foremost orchestras, including The Cleveland Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, and Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, among others. He was the inaugural artist-in-association of the New York Philharmonic from 2014–17.

Barnatan’s 2023–24 season highlights included concerto performances with the Colorado Symphony, Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, and London Philharmonic Orchestra. Barnatan also presented solo recitals at The Phillips Collection, Wigmore Hall, and 92nd Street Y.

Equally at home as a curator and chamber musician, Barnatan is music director of the La Jolla Music Society SummerFest, where he regularly collaborates with world-class partners such as Renée Fleming and Alisa Weilerstein. His passion for contemporary music has resulted in commissions and performances of new works by Thomas Adès, Andrew Norman, and Matthias Pintscher.

In November 2023, Barnatan released

his album, Rachmaninoff Reflections, offering some of the composer’s most cherished works, including Barnatan’s breathtaking new piano arrangement of the Symphonic Dances. Barnatan’s acclaimed discography also includes a two-volume set of Beethoven’s complete piano concertos, recorded with Alan Gilbert and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, and Time-Traveler’s Suite, which merges Baroque works with music by Ravel, Ligeti, Barber, and others.

Born in Tel Aviv, Barnatan started playing piano at age 3 and made his orchestral debut at 11. He studied with Victor Derevianko, a student of Heinrich Neuhaus, before moving to London to study at the Royal Academy of Music with Christopher Elton and Maria Curcio, a student of the legendary Artur Schnabel. The late Leon Fleisher was also an influential teacher and mentor. Barnatan is a recipient of an Avery Fisher Career Grant and Lincoln Center’s Martin E. Segal Award, and is an alum of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center’s Bowers Program.

Petr Popelka has established himself as one of the most beloved and in-demand conductors of his generation. He will become chief conductor of the Wiener Symphoniker in the 2024–25 season and is currently chief conductor and artistic director of the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra. He previously held the position of chief conductor of the Norwegian Radio Orchestra.

During the 2023–24 season, he led the Wiener Symphoniker, as chief conductor designate, in a new production of Weinberger’s opera Schwanda the Bagpiper at the Theater an der Wien, followed by concerts in Vienna and two European tours. He also made debuts with the Gewandhausorchester, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, and Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse, as well as at the Zurich Opera House (conducting Mozart’s Don Giovanni). In addition, Popelka returned to the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg, Danish National Symphony Orchestra, and Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, among others.

Previous debuts have seen him appear with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden, Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, SWR Symphony Orchestra, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, Frankfurt Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Radio Philharmonie, Mozarteumorchester Salzburg, Orchestra

Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI, and Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also led the annual ORF TV concert Spring in Vienna and the ZDF Advent concert in Dresden. His new productions of Shostakovich’s opera The Nose at the Semperoper and Richard Strauss’s Elektra at Oslo Opera were acclaimed by the press and audiences alike.

In the 2019–20 season, Popelka became the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra’s first conductor fellow. He received his musical education in his hometown of Prague as well as in Freiburg. Between 2010 and 2019, he was deputy principal double bass of the Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden. Aside from conducting, composition plays an important role in his artistic activities.

James Ehnes has established himself as one of the most sought-after musicians on the international stage. Gifted with a rare combination of stunning virtuosity, serene lyricism, and unfaltering musicality, Ehnes is a favorite guest at the world’s most celebrated concert halls.

Recent orchestral highlights include performances with the MET Orchestra, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, San Francisco Symphony, London Symphony Orchestra, NHK Symphony, and Munich Philharmonic. Throughout the 2023–24 season, Ehnes continued as artist-inresidence with the National Arts Centre of Canada and as artistic partner with Artis–Naples. He also made debuts with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, and Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

Alongside his concerto work, Ehnes maintains a busy recital schedule. He performs regularly at Wigmore Hall, Carnegie Hall, the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Verbier Festival, and Festival de Pâques. A devoted chamber musician, he is the leader of the Ehnes Quartet and artistic director of the Seattle Chamber Music Society.

Ehnes has an extensive discography and has won many awards for his recordings, including two Grammys, three Gramophone Awards, and 11 Juno Awards. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Ehnes recorded J.S. Bach’s six sonatas and partitas and the six sonatas of Ysaÿe

from his home with state-of-the-art recording equipment, releasing six episodes over two months. These recordings were met with critical acclaim by audiences worldwide and Ehnes was described by Le Devoir as being “at the absolute forefront of the streaming evolution.”

Ehnes began violin studies at age 5, became a protégé of the noted Canadian violinist Francis Chaplin at age 9, and made his orchestra debut with the Orchestre symphonique de Montréal at age 13.