Elgar and Walton

Completely engaged. That’s how Joe Coyle feels about his life at Judson Manor.

Completely engaged. That’s how Joe Coyle feels about his life at Judson Manor.

An award-winning journalist who has lived in Paris, Santa Fe, and New York City, he arrived in July 2020 via the suggestion of a fellow resident. He’s been delighted ever since. “As a writer, I enjoy spending time alone, and these surroundings are perfect: my apartment is quiet, and the views overlooking the Cleveland Museum of Art are lovely. But by far the best part of Judson is the people. Everyone is so knowledgeable about art and culture. I wanted to have stimulating company to spend my time with, and I’ve found that here. These are wonderful, interesting people,” says Joe. Read the full story at judsonsmartliving.org/blog

Learn more about how Judson can bring your retirement years to life! judsonsmartliving.org | 216.446.1579

Judson Park Cleveland Heights | Judson Manor University Circle | South Franklin Circle Chagrin Falls

Judson Park Cleveland Heights | Judson Manor University Circle | South Franklin Circle Chagrin Falls

it’s all about.”Joe Coyle

2022/2023 SEASON

JACK, JOSEPH AND MORTON MANDEL CONCERT HALL AT SEVERANCE MUSIC CENTER

Thursday, December 1, 2022, at 7:30 p.m.

Thursday, December 1, 2022, at 7:30 p.m. Friday, December 2, 2022, at 11:00 a.m.* Saturday, December 3, 2022, at 8:00 p.m.

Friday, December 2, 2022, at 11:00 a.m.* Saturday, December 3, 2022, at 8:00 p.m.

Vasily Petrenko, conductor

Vasily Petrenko, conductor

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

Edward Elgar (1857–1934)

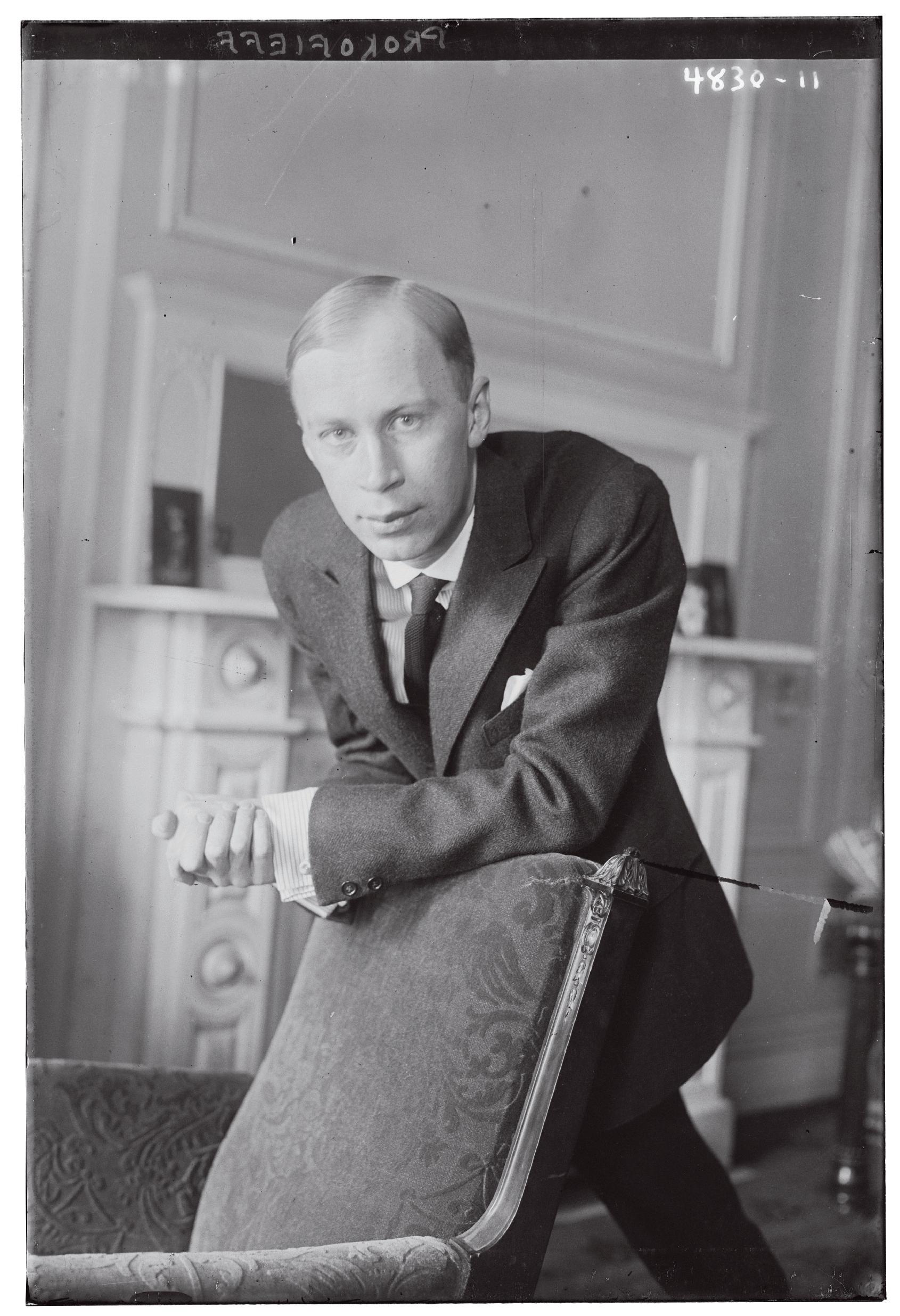

Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

Cockaigne (“In London Town”) 15 minutes Overture, Opus 40

Cockaigne (“In London Town”) 15 minutes Overture, Opus 40

Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Opus 16 * 30 minutes

William Walton (1902–1983)

William Walton (1902–1983)

2022/2023 Season Sponsor

2022/2023 Season Sponsor

clevelandorchestra.com

I. Andantino

Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Opus 16 * 30 minutes

II. Scherzo: Vivace III. Moderato

I. Andantino

II. Scherzo: Vivace III. Moderato

IV. Finale: Allegro tempestoso Behzod Abduraimov, piano

IV. Finale: Allegro tempestoso Behzod Abduraimov, piano

* Not included in Friday’s concert, which is performed without an intermission.

* Not included in Friday’s concert, which is performed without an intermission.

INTERMISSION 20 minutes

INTERMISSION 20 minutes

Symphony No. 1 in B-flat minor 45 minutes

I. Allegro assai

Symphony No. 1 in B-flat minor 45 minutes

I. Allegro assai

II. Presto, con malizia III. Andante con malincolia

II. Presto, con malizia

III. Andante con malincolia

IV. Maestoso — Brioso ed ardentemente — Vivacissimo — Maestoso

IV. Maestoso — Brioso ed ardentemente — Vivacissimo — Maestoso

Approximate running time: 1 hour 50 minutes

Approximate running time: 1 hour 50 minutes

Thank you for silencing your electronic devices.

Thank you for silencing your electronic devices.

Behzod Abduraimov’s performance is sponsored by The Hershey Foundation.

Behzod Abduraimov’s performance is sponsored by The Hershey Foundation.

Support from friends like you keeps the music playing — and it’s even more important as 2022 comes to an end. Year’s end is a crucial time for giving. Your donation before December 31 helps us close the books strong, ready to start the New Year with big plans for the music you love

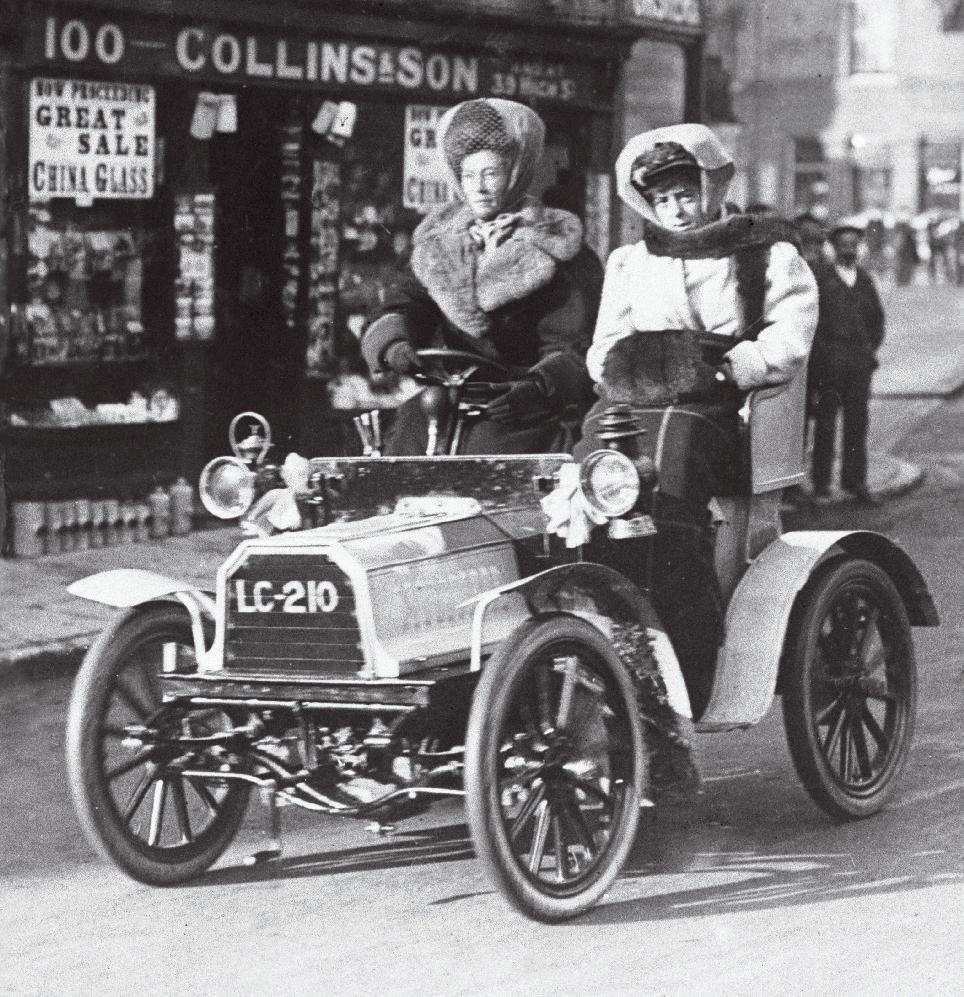

THE DAWN OF THE 20TH CENTURY ushered in a new modern age, filled with technological innovations and optimism. In England, the Central London Railway, which would become the Underground’s Central Line, opened with the system’s first fully electric-lit stations; in Russia, Ivan Pavlov’s Nobel Award–winning research on Classical Conditioning was gaining influence; and the women’s suffrage movement was gaining steam on both sides of the Atlantic.

During this era, British composer Edward Elgar delighted in visits to London, abuzz with these newfangled developments. He distilled the city’s charm, romance, and vigor into his Cockaigne Concert Overture, which opens this weekend’s programs led by Vasily Petrenko. A reference to the local Cockneys, known for their rowdy spirit, the 15-minute piece paints an aural depiction of a modernizing city, filled with young lovers, military bands, and pleasure-seeking inhabitants.

Just over a decade later, Sergei Prokofiev, influenced by a Russian Futurist movement advocating a radical break with tradition in pursuit of a Modernist vision, embarked on his Second Piano Concerto. Hisses and catcalls greeted the work at its first performance, featuring the composer at the keyboard. “But the concerto is also bursting with music for the machine age,” Prokofiev biographer Harlow Robinson later wrote, calling the second movement, “an episode of perpetual motion that moves with the relentless force and fluidity of a speeding

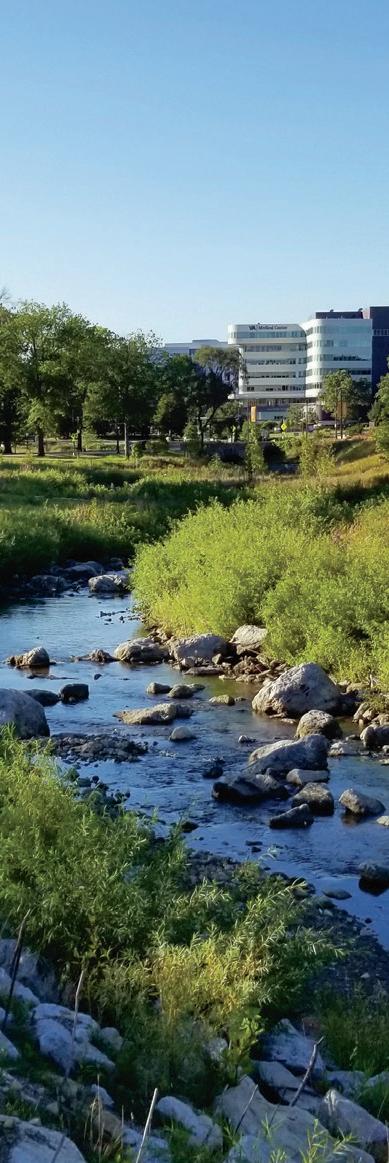

Women out for a drive on the streets of London in the first years of the 20th century. Edward Elgar captures the energy of this modernizing city in his Cockaigne Overture.

locomotive.” Pianist Behzod Abduraimov makes his Severance debut with this explosive concerto — surely to a more receptive audience than Prokofiev endured.

Fast forward to 1932, the year William Walton embarked on his First Symphony. One world war, a pandemic, a worldwide economic crisis, and a foreboding rise of fascism perhaps tempered the optimism from the beginning of the century but not its ceaseless innovation and experimentation, which burns through this work. As critic Tom Service describes in The Guardian: “This symphony is a volcanic eruption of dark, sensual passion which speaks with unmediated power from the very first bar.”

— Amanda Angel

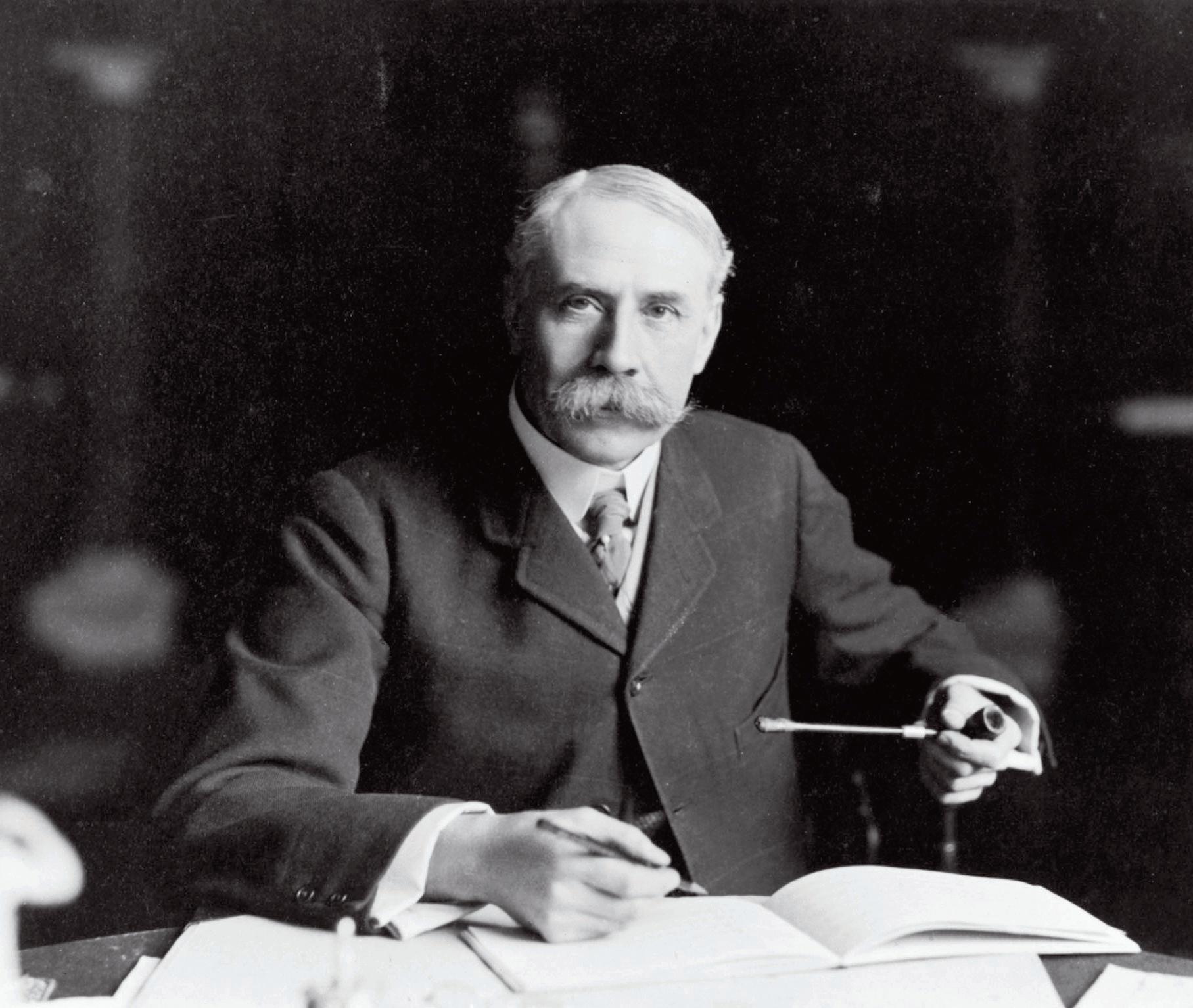

BORN : June 2, 1857, in Worcestershire, England

DIED: February 23, 1934, in Worcestershire, England Ω

COMPOSED : 1900–1901

Ω WORLD PREMIERE: Queen’s Hall, London, June 20, 1901, with the Philharmonic Society, conducted by the composer

Ω CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE: November 22, 1934, with Rudolf Ringwald conducting. The most recent performances by the Orchestra were in March 2004 under David Zinman.

Ω ORCHESTRATION: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 cornets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, military drum, orchestra bells), organ, and strings Ω

DURATION: 15 minutes

IN MEDIEVAL French poetry cockaigne is an imaginary country of idleness and delight, with an emphasis on good food. In the 17th century it had been used as a description of Paris. But for Elgar, the term was linked to London’s Cockneys, and the land of delight was London itself. As a young country boy from Worcester shire, Elgar knew that London was the place where musicians’ careers were made, and he spent his spare pennies on trips like this: “I lived 120 miles from London. I rose at 6, walked a mile to the railway station, the train left at 7; arrived at Paddington about 11, underground to

Victoria, on to the Crystal Palace arriving in time for the last three-quarters of an hour of the rehearsal. Lunch. Concert at 3. At 5 a rush to Victoria; then to Paddington, on to Worcester arriving at 10.30. A strenuous day indeed; but the new work had been heard and another treasure added to a life’s experience.”

In 1889, newly married, Elgar and his bride moved to London. Two years later, unable to make any impression as a composer, he moved back to the country. Success eluded him until 1899, when the Enigma Variations premiered and caused a sensation. Fame and honors came

quickly thereafter, and by 1904, he was Sir Edward, sought after at home and abroad, and mixing with the great and the good. He made three visits to the United States. A part of him relished the lifestyle, and in 1911, he bought a large house in London.

The other side of him was private, introverted, and melancholy, always longing to escape to his quiet home in the west country hills. The contrast between the two impulses is heard in nearly all his music. Even in Cockaigne, which he intended as a portrait of London, we hear splendid pomp and circumstance as well as a yearning for something more peaceful and more spiritual.

In a letter, Elgar said he wanted the overture to be “honest, healthy, humorous, and strong but not vulgar,” and he clearly achieved this. We hear whistling Cockneys, lovers in the parks, the city churches, a military procession, and the bustle of city life. At one point a hush descends as a band is heard in the distance. And the unforgettable moment at the end when the organ joins the full orchestra crowns a work full of joy and good fellowship.

— Hugh Macdonald

— Hugh Macdonald

BORN : April 23, 1891 in Sontsivka, Ukraine

DIED: March 5, 1953 in Moscow

Ω

COMPOSED : 1912–13, revised 1923

Ω WORLD PREMIERE: September 5, 1913, at Pavlovsk Park, near St. Petersburg, with the composer as soloist. The revised version was debuted in Paris on May 8, 1924, with Serge Koussevitzky conducting and Prokofiev, again, at the piano.

Ω CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE: April 5, 1962, under George Szell’s direction with soloist Malcolm Frager. It was most recently performed at Severance in March 2018 with Michael Tilson Thomas and soloist Daniil Trifonov. Ω

ORCHESTRATION: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, snare drum), strings, and solo piano Ω

DURATION: about 30 minutes

AROUND THE TIME that Prokofiev began work on his Second Piano Concerto, in December 1912, a group of iconoclastic poets, including the 19-year-old Vladimir Mayakovsky, issued the futurist manifesto “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste” in Moscow.

The manifesto declared, “Throw Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc. overboard from the ship of Modernity” and expressed an “insurmountable hatred for the language existing before their time.” The manifesto demanded

the abolition of all traditional art forms and a radical new start in poetry (including a call for the creation of new words). It proposed unbridled individualism in art and life.

Mayakovsky’s first volume of poetry, published in 1913, was titled simply I. The futurists tried their best, in everything, to shock their audiences, as Mayakovsky did with the title of his long poem A Cloud in Trousers (1914–15).

According to Prokofiev biographer Israel Nestyev, the composer was “an admirer of Mayakovsky’s poetic innovations.” Prokofiev even met the poet, two years his junior, and Mayakovsky gave Prokofiev a copy of his poem War and the World with the inscription: “To the World President of Music from the World President of Poetry.”

Unlike Mayakovsky, however, who had espoused the ideals of Bolshevism early on and become an ardent revolutionary, Prokofiev had little actual interest in politics. However, the young Prokofiev was, by inclination, an iconoclast, not unlike the futurist poets and painters. He, too, had little sympathy for the achievements of his predecessors. He

Prokofiev performed as soloist in the premieres of both versions of his Piano Concerto No. 2. He reconstructed it after the score was lost in a fire following the Russian Revolution.

rebelled against his teachers (Glazunov and Lyadov in particular), the Romanticism of Rachmaninoff, and the mysticism of Scriabin.

Prokofiev had a natural penchant for humor and satire, manifest since childhood, and soon perfected a musical technique to express it. This technique often involves the replacement of certain pitches in harmonies by other pitches, often only a half step away, giving the impression of being “out of tune” when it is really, of course, the harmony he intended. To increase the effect of this

harmonic procedure, Prokofiev contrast ed this new dissonance with marked traditionalism in other aspects of his style — his rhythms, for instance, often stay within the Classical framework and the basic building blocks of his melodies are inherited from Romantic music. This combination of old and new elements produces the piquancy — and unmistakable spirit — of Prokofiev’s early style.

The violence of the young Prokofiev’s quasi-futuristic “slap to the public’s taste” was not lost on the critics attending the first performance of his Second Piano Concerto, at which the composer played the solo part. One journalist called it: “a Babel of insane sounds heaped one upon another without any rhyme or reason.” Another reported: “Prokofiev seats himself at the piano and begins to strike the keyboard with a dry, sharp touch. The audience is bewildered. Some are indignant. One couple stands up and runs toward the exit. ‘Such music is enough to drive you crazy!’… The audience is scandalized. The majority hiss. Prokofiev bows defiantly and plays an encore. The audience rushes away. On all sides there are exclamations: ‘To the devil with all this futurist music! We came here to enjoy ourselves. The cats at home can make music like this!’”

Only one critic, Vyacheslav Karatygin, found praise for Prokofiev’s courage and artistic imagination, predicting a brilliant future for the 22-year-old composer: “The public hissed. This means nothing. Ten years from now it will atone for last

night’s catcalls by applauding unanimously a new composer with a European reputation.”

Karatygin’s words proved prophetic. In 1923, the composer, then living in Paris, received his first official invitation to return to Russia, where he was offered a series of concert engagements with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra. By that time, he had written the Classical Symphony (later known as Symphony No. 1 against the composer’s wishes), his Piano Concerto No. 3, the ballet Chout, and the opera The Love for Three Oranges. He also reconstructed from memory the score of his Second Piano Concerto, which had been lost in the civil war following the 1917 Russian Revolution. “I have so completely rewritten the Second Concerto,” he wrote to friends in Moscow, “that it might almost be considered the Fourth.”

The beginning of the Second Piano Concerto is a perfect example of Prokofiev’s “futurist” style. At the start of the first movement, a beautiful, eightbar melody, played by the solo piano to an accompaniment of almost Chopinesque figurations in the left hand, is spiced with many seemingly incongruous notes. The instructions given to the performer — narrante, caloroso, con gran espressione (narrating, with warmth and great expression) — reinforce this Romantic attitude, which coexists with completely un-Romantic sonorities. The movement’s second section adopts a faster tempo and a skipping, staccato melody, marked con eleganza. After a

virtuosic development of this theme, the initial melody returns, growing into an extended cadenza that is turbulent, highly dramatic, and fiendishly difficult to play. A return of the first theme closes the movement, which dies away pianissimo.

Throughout the Scherzo, the piano plays unbroken sixteenth notes in octave unisons, while the melody belongs to the orchestra. It is a movement of perpetual motion and energy, with a virtually uninterrupted rhythmic ostinato, shot through with occasional melodic fragments played by various solo instruments and combinations.

The third-movement Moderato is also based on a rhythmic ostinato, interrupted only once by a short, lyrical piano solo. This caricature of a march includes a middle section (marked “gently, somewhat humorously”) where the piano’s

arpeggios and glissando effects provide the background for a little tongue-incheek melody in the woodwinds. The march returns with a section for piano alone. The full orchestra gradually enters and builds up to a tremendous climax (the high harmonics, a special technique on the violins, are particularly striking), only to collapse in the lowest register in a sudden quiet that ends the movement the same way the first movement had closed.

The Finale (marked Allegro tempestoso) contains a number of contrasting sections. It starts with a wild rush and irregular rhythmic figures with wide leaps in both the piano and the orchestral parts. This material then yields to a slower tempo and a simple tune that biographer Nestyev called a Russian lullaby. This lullaby, however, becomes extremely loud and agitated, and as the tempo speeds up again, the music reaches a fortissimo cadence that gives the impression that the piece has ended. It is too early to applaud, however, for the pianist attacks a second breakneck cadenza. The orchestra enters with the lullaby melody while the piano continues its virtuoso passages. Finally — after a short, meditative andante section set over mysterious tremolo — the first theme returns with its irregular rhythms and brings the work to an animated and boisterous close.

— Peter Laki

— Peter Laki

ClevelandArtsEvents .com connects you to the region’s vibrant arts and culture scene. With just a few clicks, discover hundreds of events made possible in part with public funding from Cuyahoga Arts & Culture.

BORN : March 29, 1902, in Oldham, England

DIED: March 8, 1983, on Ischia, Italy

COMPOSED : 1932–35 Ω

WORLD PREMIERE: Movements I–III were first performed at Queen’s Hall, London, on December 3, 1934, by the London Symphony Orchestra with conductor Sir Hamilton Harty. The complete work received its debut at Queen’s Hall on November 6, 1935, with Harty leading the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Ω

CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE: The Cleveland Orchestra championed William Walton as a composer, premiering his Violin Concerto in 1939 and giving the first American performances of his Symphony No. 2 in 1960. So it is surprising that the Orchestra’s first performance of his Symphony No. 1 came nearly 30 years after it was written, on April 22, 1972, with conductor André Previn.

ORCHESTRATION: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, 2 timpani, percussion (cymbals, field drum, tam-tam), and strings

DURATION: 45 minutes

SOME COMPOSERS have no difficulty writing music and produce it in an endless stream — Telemann and SaintSaëns come to mind. Others face an eternal battle, wrestling with their muse and often unhappy with the result. In his later years, William Walton fell clearly into that camp — in fear of being overtaken by the younger generation —

With his First Symphony, composer William Walton sought to make a lasting mark on British music of the 20th century.

and composed under stresses he would prefer to be spared. As a young composer, he had been brimful of confidence and vitality, and his rise to fame with the Viola Concerto in 1929 and the choral Belshazzar’s Feast in 1931 set him at the head of young British composers. The invitation to write a symphony for Manchester’s Hallé Orchestra in 1932 could only lead to expectations of a major work, and indeed such a thing did come into being, but only after hesitations and difficulties

The

that were to beset the composer more seriously in the years to come without ever diminishing the richness or brilliance of his writing.

The invitation came from Sir Hamilton Harty, the Hallé’s conductor, in January 1932. Yet, it would be nearly four years before the full work was heard, years in which Walton’s volatile attachment to the Baroness Imma Doernberg (to whom the symphony was eventually dedicated) was a constant destabilizing force, causing ups and downs in his emotional state and hence in his ability to string the notes together. Composing was

already proving, clearly, to be a troublesome pursuit for which he knew, as all his friends did, that he had a special gift.

Early in 1932, a friend reported: “Willie now is writing and varies between thinking he is getting going and feeling sure that all he has done must be torn up. This evening he says it is anaemic, sentimental, dull and worthless. Says he has never been inspired in his life and can’t think why he writes.” So much for self-confidence.

By the spring of 1933, however, the first two movements were drafted. A year later, there were three movements ready, but no finale. By this time Harty had moved from the Hallé Orchestra to the London Symphony Orchestra, whose management put pressure on Walton to finish the symphony. It was even ready to take the unprecedented step of giving the first performance without a finale. Walton, who had on his own confession destroyed three versions of the finale, agreed to the unveil the first threefourths, convinced that it was better to delay completion rather than serve up “a brilliant, out-of-the-place pointless and vacuous” finale.

So a three-movement-only premiere took place in London in December 1934 and was surprisingly well received. Not till April 1935 did the composer bring himself to look for a finale that satisfied him, aided by his friend, composer Constant Lambert, who suggested a fugue as a way out of his impasse. So, after some initial pages that recall the brassy brilliance of Belshazzar’s Feast,

the final movement sets off on a vigorous fugue whose energy takes the music into a strong, clamorous ending.

Completion was reported in August 1935, and the full premiere was given in November. It had been a long and complicated birth, but the child was a sturdy addition to Walton’s growing family of masterpieces, to be soon followed by the Violin Concerto and some fine film scores.

One of the most striking aspects of the music is its magnificent sense of distance, like a broad prairie beyond which faraway landmarks can be made out. A bass note is often sustained for a long period, creating a sense of stasis, while upper notes may be swift and intricate, restless

even, so that motion is both fast and slow at the same time. This feature has quite reasonably been attributed to the heritage of Sibelius, the master of tempo control, whose symphonies were much played in England at that time.

Both the first movement and the second one, a scherzo, are heavily scored, so that the winds are not much heard on their own until the slow third movement. This offers some elegant solos that build to a strong climax and then fade. The finale resumes the bustling, vigorous, noisy style of the opening two movements, a style critics of the time lauded as “virile.” While that label feels rather dated today, Walton’s music remains as potent as ever.

— Hugh Macdonald

VASILY PETRENKO is music director of the Royal Philharmonic, chief conductor of the European Union Youth Orchestra, and was artistic director of the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia through March 2022 (where he was principal guest conductor starting in 2016). He served as chief conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (2006–21) and the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra (2013–20), principal conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain (2009–13), and principal guest conductor of St. Petersburg’s Mikhailovsky Theatre, where he began his career as resident conductor (1994–97).

Mr. Petrenko was born in 1976 and started his music education at the St. Petersburg Capella Boys Music School — Russia’s oldest music school. He then studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he participated in masterclasses with figures such as Ilya Musin, Mariss Jansons, and Yuri Temirkanov.

He has worked with many of the world’s most prestigious orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio Symphony, Leipzig Gewandhaus, London Symphony, London Philharmonic, Philharmonia, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (Rome), St. Petersburg Philharmonic, Orchestre National de France, Czech Philharmonic, NHK Symphony, and Sydney Symphony Orchestra. In North America, he has led The Philadelphia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, The Cleveland Orchestra,

and the San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, and Montreal Symphony Orchestras. Festival appearances include Edinburgh, Grafenegg, and the BBC Proms.

Mr. Petrenko has conducted widely on the operatic stage, including at Glyndebourne Festival Opera, the Opéra National de Paris, Opernhaus Zürich, Bayerische Staatsoper, and the Metropolitan Opera (New York).

Vasily Petrenko has established a strongly defined profile as a recording artist. Notably, he has recorded Shostakovich, Rachmaninoff, and Elgar symphony cycles with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra that have garnered worldwide acclaim. With the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, he recently released cycles of Scriabin and Prokofiev symphonies and Richard Strauss tone poems.

BEHZOD ABDURAIMOV ’s performances combine an immense depth of musicality with phenomenal technique and breathtaking delicacy. He performs with renowned orchestras worldwide including Philharmonia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Deutsches SymphonieOrchester Berlin, San Francisco Symphony, The Cleveland Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, and Concertgebouworkest, as well as with prestigious conductors such as Juraj Valčuha, Vasily Petrenko, Lorenzo Viotti, James Gaffigan, Jakub Hrůša, SanttuMatias Rouvali, and Gustavo Dudamel. His 2022/23 European performances include concerts with Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Wiener Symphoniker, SWR Symphonieorchester, Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Philharmonia Orchestra, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, and as part of Belgian National Orchestra’s Rachmaninoff’s Festival. In North America, Mr. Abduraimov returns to The Cleveland Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. In summer 2022, he made his third appearance at the BBC Proms.

BEHZOD ABDURAIMOV ’s performances combine an immense depth of musicality with phenomenal technique and breathtaking delicacy. He performs with renowned orchestras worldwide including Philharmonia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Deutsches SymphonieOrchester Berlin, San Francisco Symphony, The Cleveland Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, and Concertgebouworkest, as well as with prestigious conductors such as Juraj Valčuha, Vasily Petrenko, Lorenzo Viotti, James Gaffigan, Jakub Hrůša, SanttuMatias Rouvali, and Gustavo Dudamel. His 2022/23 European performances include concerts with Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Wiener Symphoniker, SWR Symphonieorchester, Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Philharmonia Orchestra, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, and as part of Belgian National Orchestra’s Rachmaninoff’s Festival. In North America, Mr. Abduraimov returns to The Cleveland Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. In summer 2022, he made his third appearance at the BBC Proms.

In recital, he has appeared at Carnegie Hall’s Stern Auditorium, Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, and Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, and has recently been presented by Alte Oper, Frankfurt; Amare Hall, The Hague; Vancouver Recital Society; and The Conrad Center, La Jolla. This season, he performs at Meany Hall, Seattle;

In recital, he has appeared at Carnegie Hall’s Stern Auditorium, Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, and Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, and has recently been presented by Alte Oper, Frankfurt; Amare Hall, The Hague; Vancouver Recital Society; and The Conrad Center, La Jolla. This season, he performs at Meany Hall, Seattle;

Spivey Hall, Atlanta; and La Società dei Concerti di Milano. Regular festival appearances include Aspen, Verbier, Rheingau, La Roque Antheron, and Lucerne. In 2021, Mr. Abduraimov released the album Debussy — Chopin — Mussorgsky (Alpha Classics). Two of his 2020 recordings — Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with Lucerne Symphony Orchestra under James Gaffigan, recorded on Rachmaninoff’s piano from Villa Senar (Sony Classical) and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with Concertgebouworkest (RCO) — were nominated for Opus Klassik awards.

Spivey Hall, Atlanta; and La Società dei Concerti di Milano. Regular festival appearances include Aspen, Verbier, Rheingau, La Roque Antheron, and Lucerne.

Born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, in 1990, Behzod Abduraimov began the piano at age five as a pupil of Tamara Popovich at Uspensky State Central Lyceum in Tashkent. In 2009, he won First Prize at the London International Piano Competition. He studied with Stanislav Ioudenitch at the International Center for Music at Park University, Missouri, where he is artist-in-residence.

In 2021, Mr. Abduraimov released the album Debussy — Chopin — Mussorgsky (Alpha Classics). Two of his 2020 recordings — Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with Lucerne Symphony Orchestra under James Gaffigan, recorded on Rachmaninoff’s piano from Villa Senar (Sony Classical) and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with Concertgebouworkest (RCO) — were nominated for Opus Klassik awards. Born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, in 1990, Behzod Abduraimov began the piano at age five as a pupil of Tamara Popovich at Uspensky State Central Lyceum in Tashkent. In 2009, he won First Prize at the London International Piano Competition. He studied with Stanislav Ioudenitch at the International Center for Music at Park University, Missouri, where he is artist-in-residence.

NOW IN ITS SECOND CENTURY , The Cleveland Orchestra, under the leadership of music director Franz WelserMöst since 2002, is one of the most sought-after performing ensembles in the world. Year after year, the ensemble exemplifies extraordinary artistic excellence, creative programming, and community engagement. The New York Times has called Cleveland “the best in America” for its virtuosity, elegance of sound, variety of color, and chamberlike musical cohesion.

Founded by Adella Prentiss Hughes, the Orchestra performed its inaugural concert in December 1918. By the middle of the century, decades of growth and sustained support had turned it into one of the most admired globally.

The past decade has seen an increasing number of young people attending concerts, bringing fresh attention to The Cleveland Orchestra’s legendary sound and committed programming. More recently, the Orchestra launched several bold digital projects, including the streaming broadcast series In Focus, the podcast On a Personal Note, and its own recording label, a new chapter in the Orchestra’s long and distinguished recording and broadcast history. Together, they have captured the Orchestra’s unique artistry and the musical achievements of the Welser-Möst and Cleveland Orchestra partnership.

The 2022/23 season marks Franz Welser-Möst’s 21st year as music director, a period in which The Cleveland Orchestra earned unprecedented acclaim around the world, including a series of residencies at the Musikverein in Vienna, the first of its kind by an American orchestra, and a number of acclaimed opera presentations.

Since 1918, seven music directors — Nikolai Sokoloff, Artur Rodziński, Erich Leinsdorf, George Szell, Lorin Maazel, Christoph von Dohnányi, and Franz Welser-Möst — have guided and shaped the ensemble’s growth and sound. Through concerts at home and on tour, broadcasts, and a catalog of acclaimed recordings, The Cleveland Orchestra is heard today by a growing group of fans around the world.

David Radzynski

CONCERTMASTER Blossom-Lee Chair

Peter Otto

FIRST ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER

Virginia M. Lindseth, PhD, Chair

Jung-Min Amy Lee ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER Gretchen D. and Ward Smith Chair Jessica Lee

ASSISTANT CONCERTMASTER

Clara G. and George P. Bickford Chair

Stephen Tavani ASSISTANT CONCERTMASTER Wei-Fang Gu Drs. Paul M. and Renate H. Duchesneau Chair Kim Gomez Elizabeth and Leslie Kondorossy Chair Chul-In Park

Harriet T. and David L. Simon Chair

Miho Hashizume Theodore Rautenberg Chair

Jeanne Preucil Rose

Larry J.B. and Barbara S. Robinson Chair

Alicia Koelz

Oswald and Phyllis Lerner Gilroy Chair

Yu Yuan

Patty and John Collinson Chair

Isabel Trautwein

Trevor and Jennie Jones Chair

Katherine Bormann

Analisé Denise Kukelhan Gladys B. Goetz Chair Zhan Shu

Stephen Rose*

Alfred M. and Clara T. Rankin Chair Eli Matthews1 Patricia M. Kozerefski and Richard J. Bogomolny Chair

Sonja Braaten Molloy Carolyn Gadiel Warner

Elayna Duitman

Ioana Missits

Jeffrey Zehngut

Vladimir Deninzon

Sae Shiragami

Kathleen Collins Beth Woodside

Emma Shook Dr. Jeanette Grasselli Brown and Dr. Glenn R. Brown Chair

Yun-Ting Lee Jiah Chung Chapdelaine

Wesley Collins*

Chaillé H. and Richard B. Tullis Chair

Lynne Ramsey1

Charles M. and Janet G. Kimball Chair

Stanley Konopka2 Mark Jackobs Jean Wall Bennett Chair

Lisa Boyko Richard and Nancy Sneed Chair

Richard Waugh

Lembi Veskimets

The Morgan Sisters Chair Eliesha Nelson Joanna Patterson Zakany William Bender Gareth Zehngut

Mark Kosower* Louis D. Beaumont Chair

Richard Weiss1

The GAR Foundation Chair

Charles Bernard2 Helen Weil Ross Chair

Bryan Dumm Muriel and Noah Butkin Chair

Tanya Ell Thomas J. and Judith Fay Gruber Chair

Ralph Curry Brian Thornton William P. Blair III Chair

David Alan Harrell Martha Baldwin Dane Johansen Paul Kushious

Maximilian Dimoff* Clarence T. Reinberger Chair

Derek Zadinsky2 Mark Atherton

Thomas Sperl Henry Peyrebrune Charles Barr Memorial Chair

Charles Carleton Scott Dixon Charles Paul HARP

Trina Struble* Alice Chalifoux Chair

Joshua Smith*

Elizabeth M. and William C. Treuhaft Chair Saeran St. Christopher Jessica Sindell2 Austin B. and Ellen W. Chinn Chair Mary Kay Fink

PICCOLO Mary Kay Fink Anne M. and M. Roger Clapp Chair

Frank Rosenwein* Edith S. Taplin Chair Corbin Stair Sharon and Yoash Wiener Chair

Jeffrey Rathbun2 Everett D. and Eugenia S. McCurdy Chair Robert Walters

Robert Walters Samuel C. and Bernette K. Jaffe Chair

Afendi Yusuf* Robert Marcellus Chair Robert Woolfrey Victoire G. and Alfred M. Rankin, Jr. Chair

Daniel McKelway2 Robert R. and Vilma L. Kohn Chair Amy Zoloto

E-FLAT CLARINET

Daniel McKelway Stanley L. and Eloise M. Morgan Chair

BASS CLARINET

Amy Zoloto Myrna and James Spira Chair

BASSOONS

John Clouser* Louise Harkness Ingalls Chair

Gareth Thomas Barrick Stees2 Sandra L. Haslinger Chair Jonathan Sherwin

CONTRABASSOON

Jonathan Sherwin

HORNS

Nathaniel Silberschlag* George Szell Memorial Chair

Michael Mayhew§ Knight Foundation Chair

Jesse McCormick

Robert B. Benyo Chair Hans Clebsch

Richard King

TRUMPETS

Michael Sachs* Robert and Eunice Podis Weiskopf Chair

Jack Sutte

Lyle Steelman2 James P. and Dolores D. Storer Chair

Michael Miller

CORNETS

Michael Sachs* Mary Elizabeth and G. Robert Klein Chair Michael Miller

TROMBONES

Brian Wendel*

Gilbert W. and Louise I. Humphrey Chair

Richard Stout Alexander and Marianna C. McAfee Chair

Shachar Israel2

EUPHONIUM & BASS TRUMPET

Richard Stout

TUBA

Yasuhito Sugiyama* Nathalie C. Spence and Nathalie S. Boswell Chair

Paul Yancich* Otto G. and Corinne T. Voss Chair

Marc Damoulakis*

Margaret Allen Ireland Chair

Donald Miller

Thomas Sherwood

Carolyn Gadiel Warner Marjory and Marc L. Swartzbaugh Chair

LIBRARIANS

Michael Ferraguto

Joe and Marlene Toot Chair

Donald Miller

ENDOWED CHAIRS

CURRENTLY UNOCCUPIED

Elizabeth Ring and William Gwinn Mather Chair

Paul and Lucille Jones Chair

James and Donna Reid Chair

Mary E. and F. Joseph Callahan Chair

Sunshine Chair

Mr. and Mrs. Richard K. Smucker Chair Rudolf Serkin Chair

This roster lists full-time members of The Cleveland Orchestra. The number and seating of musicians onstage varies depending on the piece being performed. Seating within the string sections rotates on a periodic basis.

Vasily Petrenko, conductor Behzod Abduraimov, piano*

ELGAR Cockaigne (“In London Town”)

PROKOFIEV Piano Concerto No. 2* WALTON Symphony No. 1 * not part of Friday Matinee concert

Alan Gilbert, conductor Paul Yancich, timpani

Liv Redpath, soprano Justin Austin, baritone

OLIVERIO Legacy Ascendant HAYDN Symphony No. 90 NIELSEN Symphony No. 3 (“Sinfonia espansiva”)

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Joélle Harvey, soprano

Daryl Freedman, mezzo-soprano Julian Prégardien, tenor Martin Mitterrutzner, tenor

Dashon Burton, bass-baritone Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

BERG Lyric Suite*

SCHUBERT Symphony No. 8* (“Unfinished”)

SCHUBERT Mass No. 6

* The movements of the Lyric Suite will be performed in rotation with Symphony No. 8

Klaus Mäkelä, conductor

Truls Mørk, cello

SALONEN Cello Concerto DEBUSSY Images RAVEL Boléro

Klaus Mäkelä, conductor

CHIN SPIRA—Concerto for Orchestra

MAHLER Symphony No. 5

Herbert Blomstedt, conductor

Emanuel Ax, piano

MOZART Piano Concerto No. 18 (“Paradis”)

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

MOZART Divertimento No. 2*

SCHOENBERG Variations for Orchestra

STRAUSS Ein Heldenleben

* not part of Friday Matinee concert

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Víkingur Ólafsson, piano

FARRENC Symphony No. 3

RAVEL Piano Concerto in G major MUSSORGSKY/RAVEL Pictures at an Exhibition

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Christoph Sietzen, percussion

Siobhan Stagg, soprano

Avery Amereau, alto

Ben Bliss, tenor

Anthony Schneider, bass

Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

STAUD Concerto for Percussion

MOZART Requiem

Thomas Adès, conductor

Pekka Kuusisto, violin

ADÈS The Tempest Symphony ADÈS Märchentänze

SIBELIUS Six Humoresques* SIBELIUS Prelude and Suite No. 1 from The Tempest* * Certain selections will not be part of the Friday Matinee concert

Rafael Payare, conductor Jean-Yves Thibaudet, piano BERNSTEIN Symphony No. 2 (“The Age of Anxiety”) SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No. 5

Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor Leif Ove Andsnes, piano DEBUSSY Jeux, poème dansé DEBUSSY Fantaisie for Piano and Orchestra

MAHLER Symphony No. 1 (“Titan”)

Bernard Labadie, conductor Lucy Crowe, soprano

MOZART Overture to La clemenza di Tito MOZART “Giunse al fin il momento... Al desio di chi t’adora” MOZART Ruhe Zanft from Zaide MOZART Masonic Funeral Music MOZART “Venga la morte... Non temer, amato bene” MOZART Symphony No. 41 (“Jupiter”)

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor Michael Sachs, trumpet MARTINŮ Symphony No. 2 MARSALIS Trumpet Concerto DVOŘÁK Symphony No. 9 (“From the New World”)

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor Alisa Weilerstein, cello LOGGINS-HULL Can You See? BARBER Cello Concerto PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 4

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor Tamara Wilson, soprano (Minnie) Eric Owens, bass (Jack Rance) Limmie Pulliam, tenor (Dick Johnson)

Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

PUCCINI La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West) * Opera presentation, sung in Italian with projected supertitles

The Cleveland Orchestra is committed to creating a comfortable, enjoyable, and safe environment for all guests at Severance Music Center. While mask and COVID-19 vaccination are recommended they are not required. Protocols are reviewed regularly with the assistance of our Cleveland Clinic partners; for up-to-date information, visit: clevelandorchestra. com/attend/health-safety

As a courtesy to the audience members and musicians in the hall, late-arriving patrons are asked to wait quietly until the first convenient break in the program. These seating breaks are at the discretion of the House Manager in consultation with the performing artists.

As a courtesy to others, please silence all devices prior to the start of the concert.

Audio recording, photography, and videography are prohibited during performances at Severance. Photographs can only be taken when the performance is not in progress.

For the comfort of those around you, please reduce the volume on hearing aids and other devices that may produce a noise that would detract from the program. For Infrared Assistive-Listening Devices, please see the House Manager or Head Usher for more details.

Contact an usher or a member of house staff if you require medical assistance. Emergency exits are clearly marked throughout the building. Ushers and house staff will provide instructions in the event of an emergency.

Regardless of age, each person must have a ticket and be able to sit quietly in a seat throughout the performance. Classical season subscription concerts are not recommended for children under the age of 8. However, there are several age-appropriate series designed specifically for children and youth, including Music Explorers (for 3 to 6 years old) and Family Concerts (for ages 7 and older).

The Cleveland Orchestra is grateful to the following organizations for their ongoing generous support of The Cleveland Orchestra: the State of Ohio and Ohio Arts Council and to the residents of Cuyahoga County through Cuyahoga Arts and Culture.

The Cleveland Orchestra is proud of its long-term partnership with Kent State University, made possible in part through generous funding from the State of Ohio. The Cleveland Orchestra is proud to have its home, Severance Music Center, located on the campus of Case Western Reserve University, with whom it has a long history of collaboration and partnership.

© 2022 The Cleveland Orchestra and the Musical Arts Association Program books for Cleveland Orchestra concerts are produced by The Cleveland Orchestra and are distributed free to attending audience members.

EDITOR Amanda Angel Managing Editor of Content aangel@clevelandorchestra.com

DESIGN Elizabeth Eddins, eddinsdesign.com

ADVERTISING Live Publishing Company, 216-721-1800

See this extraordinary collection of more than 100 masterworks—the largest gift of art to the museum in more than 60 years—together for the first and only time.

Open Now | Tickets at cma.org | CMA Members FREE

The Cleveland Museum of Art is funded in part by residents of Cuyahoga County through a public grant from Cuyahoga Arts & Culture. This exhibition was supported in part by the Ohio Arts Council, which receives support from the State of Ohio and the National Endowment for the Arts.

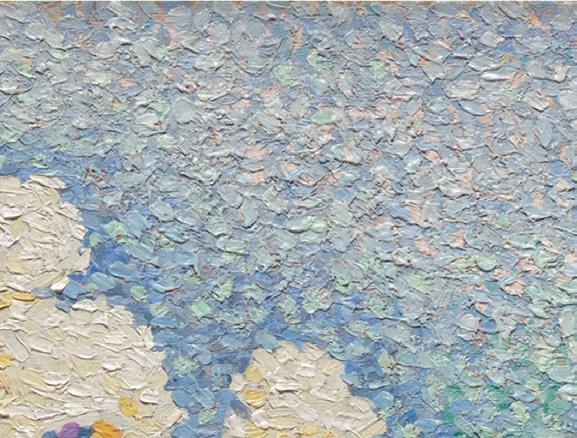

Henri-Edmond Cross (French, 1856–1910). The Pink Cloud, c. 1896. Oil on canvas; 54.6 x 61 cm. Nancy F. and Joseph P. Keithley Collection Gift, 2020.106

We believe that all Cleveland youth should have access to high-quality arts education. Through the generosity of our donors, we are investing to scale up neighborhoodbased programs that now serve 3,000 youth year-round in music, dance, theater, photography, literary arts and curatorial mastery. That’s a symphony of success. Find your passion, and partner with the Cleveland Foundation to make your greatest charitable impact. (877)554-5054 w ww.ClevelandFoundation.org