Completely engaged. That’s how Joe Coyle feels about his life at Judson Manor.

Completely engaged. That’s how Joe Coyle feels about his life at Judson Manor.

An award-winning journalist who has lived in Paris, Santa Fe, and New York City, he arrived in July 2020 via the suggestion of a fellow resident. He’s been delighted ever since. “As a writer, I enjoy spending time alone, and these surroundings are perfect: my apartment is quiet, and the views overlooking the Cleveland Museum of Art are lovely. But by far the best part of Judson is the people. Everyone is so knowledgeable about art and culture. I wanted to have stimulating company to spend my time with, and I’ve found that here. These are wonderful, interesting people,” says Joe. Read the full story at judsonsmartliving.org/blog

Learn more about how Judson can bring your retirement years to life! judsonsmartliving.org | 216.446.1579

Judson Park Cleveland Heights | Judson Manor University Circle | South Franklin Circle Chagrin Falls

Judson Park Cleveland Heights | Judson Manor University Circle | South Franklin Circle Chagrin Falls

it’s all about.”Joe Coyle

Thursday, January 5, 2023, at 7:30 p.m. Saturday, January 7, 2023, at 8:00 p.m.

James Oliverio (b. 1956)

Legacy Ascendant 20 minutes

Concerto for Timpani and Strings

I. Then II. Halcyon III. Once Again Paul Yancich, timpani World Premiere, commissioned by The Cleveland Orchestra

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809)

Symphony No. 90 in C major 25 minutes

I. Adagio — Allegro assai II. Andante III. Menuetto — Trio

IV. Finale: Allegro assai

INTERMISSION 20 minutes

Carl Nielsen (1865–1931)

Symphony No. 3 (“Sinfonia espansiva”) in D major, Opus 27 40 minutes

I. Allegro espansive II. Andante pastorale III. Allegretto un poco

IV. Finale: Allegro Liv Redpath, soprano Justin Austin, baritone

Approximate running time: 1 hour 45 minutes

2022/2023 Season Sponsor

Thank you for silencing your electronic devices. Thursday evening’s concert is dedicated to Rebecca F. Dunn in recognition of her extraordinary generosity in support of The Cleveland Orchestra.

WHAT BETTER WAY to start a new year than with a world premiere. This weekend opens with the first performances of James Oliverio’s Legacy Ascendant Concerto for Timpani and Strings, which The Cleveland Orchestra commissioned for principal timpanist Paul Yancich. The evocative title refers specifically to the five-decade relationship between Oliverio and Yancich during which they helped craft a new repertoire for solo timpani, adding three concertos and chamber works.

The concerto’s name also provides a fitting theme for this sweeping program encompassing four centuries of music history, reaching back to the foundations of the symphony while simultaneously spinning forward through the inventions of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The concert continues with Haydn’s Symphony No. 90, commissioned by the same French aristocrat who underwrote all six of the composer’s “Paris” symphonies (Nos. 82 to 87). With his prolific output, Haydn, nicknamed the “Father of the Symphony,” created a form that Danish composer Carl Nielsen would bend to his sensibilities more than 100 years later. Nielsen’s Third Symphony “Sinfonia espansiva,” which closes the program, drapes a colorful Scandinavian sound palette — Viking horn calls, Danish folksongs, and a Nordic landscape brought to vivid relief — over an essentially Classical structure.

Conductor Alan Gilbert, a longtime friend of the Orchestra, has championed Nielsen’s work throughout his career.

“To me there’s a palpable sense of humanity in his music,” Gilbert said. “He’s such an amazing composer who can capture in a very personal, unique way a kind of universal human experience. It’s the kind of music that speaks to people.”

Introducing these symphonies, Oliverio’s concerto stands as a fulcrum between past and future. Embedded in the score is inherited wisdom imparted by teachers and mentors, as well as the promise of passing on to a new generation of musicians. As Oliverio says, “To be able to see from a mountain peak in both directions — to me that’s very special and meaningful.”

— Amanda AngelBORN : April 11, 1956, in Cleveland, Ohio

COMPOSED : 2021–22

WORLD PREMIERE: This weekend’s concerts mark the world premiere performances of Legacy Ascendant.

ORCHESTRATION: string orchestra, harp, and solo timpani

DURATION: 20 minutes

Legacy Ascendant, the third in a trilogy of timpani concertos by James Oliverio, encompasses what the composer calls a mountaintop view on several fronts: a musical legacy, a passage across two centuries, and a personal history that began right here in Cleveland.

The world premiere of his Concerto for Timpani and Strings — performed by Paul Yancich, the Orchestra’s principal timpanist since 1981 — is the culmination of nearly five decades of collaboration and friendship that started during their student days at the Cleveland Institute of Music. For Oliverio, a prolific and versatile composer who has won five Emmys for his work in television, the artistic partnership has taken him from having to learn how timpani work to setting a new standard in solo repertoire for the instrument. For Yancich, it has

begotten a body of work that not only has deeply personal roots, but has expanded and advanced what’s possible for timpanists today and in the future. Mutual trust and respect have allowed Yancich and Oliverio to push each other over the years. As students in the 1970s, when Yancich first approached Oliverio to write a piece for his senior recital, there wasn’t much by way of suitable repertoire, and Oliverio didn’t know much about the instrument. So, with Yancich’s help, he set out to familiarize himself with its mechanics, even getting on the floor to study how the pedals and gears work to change the drum’s pitch.

From there a lifelong artistic dynamic developed, defined by exchanges of ideas, feedback, and always a willingness to try something new. “I believe the composer and the performer in collaboration spur

each other on to greater achievement,” says Oliverio. “To me that advances the art form.”

Oliverio composed all three of his timpani concertos for Yancich. From the start, Oliverio intended to broaden the perception of the timpani beyond providing rhythmic support or accentuating dramatic moments in orchestral pieces. His first concerto, The Olympian (1990), shattered those boundaries for audiences and performers alike, introducing deep melodic lines and demanding that timpanists juggle eight drums, as opposed to the conventional orchestral setup of two to four. One section in the third movement earned the nicknames “Chaos,” “Spider,” or “Octopus,” as Mark Yancich, Paul’s brother and principal timpanist of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, calls it due to the athletic arm-wriggling needed to rapidly hit the eight drums encircling the timpanist. Since its premiere with The Cleveland Orchestra and Paul Yancich in May 1990, The Olympian has been performed by timpanists with several other major orchestras and even inspired a doctoral dissertation.

Oliverio’s second piece, DYNASTY Double Timpani Concerto (2011), was written for both Yancich brothers. The two hail from a musical family going back at least four generations, among them professional cornet and horn players, and a grandfather, Paul White, who conducted the Rochester Philharmonic for 30 years.

For the creation of Legacy Ascendant,

commissioned by The Cleveland Orchestra, Yancich had a few requests: strings only for the orchestra, and a composition that brought out qualities of tone in the timpani and engaged musical dialogue among all the instruments. Oliverio added a harp, which has played a strong supporting role in all his timpani concertos, to complement and contrast with the starring kettledrums.

Yancich likens the challenge of playing melodic lines on the timpani to playing a violin where “everything is a pizzicato and on an open string.” To create pitch, timpanists use pedals to adjust the tension of each drum head before it’s struck, a technical feat that’s often invisible at the back of the stage. Tone —

a quality of sound that mixes color, timbre, articulation, and pitch —is all about the player’s touch and technique, as well as the type of sticks and drums he uses. The new concerto, notes Yancich, is “less a technical display of virtuosity in terms of flying around the drums and more the beauty of sound.”

Yancich’s knowledge and mastery of the three concertos he helped bring to fruition will be part of the legacy he passes on to a new generation of performers. He carries the musical legacy he inherited from his family and teachers, and the one he developed as a performer and teacher himself.

Seeing the full arc of past, present, and future is very much embedded in Oliverio’s creative DNA. He is enchanted with the idea of living at the turn of a century, and readily acknowledges past influences in his compositions while embracing contemporary tools and sensibilities. (For 22 years, he has been executive director of the Digital Worlds Institute at the University of Florida, with professorships in Music and in Digital Arts & Sciences.) Accordingly, Legacy Ascendant has influences that include jazz and pop music, as well as 20th-century concert repertoire.

Oliverio says he sought to make Legacy Ascendant “both engaging and reflective” — a balance of the “go go go” excitement that’s common in youth and the more contemplative mood that deepens with the years. Even the three movement titles walk us down the path: Then, Halcyon, Once Again. The 20-minute

work closes with a long decrescendo — a soft, subtle fade unlike the “exclamation points” that mark the end of his previous timpani concertos. “It fades off into the distance like an echo across the valley from the mountains,” Oliverio says. “Then the silence returns, and that’s a chance to breathe again, and renew.”

That shift is fitting for a composer who set out several decades ago to show that the timpani is more than just “bravado and underscoring the orchestra in the loud parts,” as he once put it. “I wanted to add to the repertoire and hopefully help to do for timpani what Paganini and Chopin did for their instruments,” he says in reflection. “That’s part of the legacy that I hope will go on. And Paul as a performer has expanded what it means to be a virtuoso timpanist.”

In his score notes, Oliverio states that Legacy Ascendant is not only a showcase for Yancich’s artistry, but also a celebration of their lifelong friendship and artistic collaboration. One might also call it evolution.

“To return to our old stomping grounds in Cleveland and to have crossed into the 21st century and worked together in two centuries — it is just a poetic kind of development,” the composer says.

“To be able to see from a mountain peak in both directions — to me that’s very special and meaningful.”

— Luna Shyr

Luna Shyr is a freelance writer and editor. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, The Wall Street Journal, Atlas Obscura, and at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

Music, like life itself, is comprised of moments unfolding in time. Some are at once memorable; others may take decades to acquire meaning. I have been blessed with moments of both kinds in my relationship with virtuoso timpanist Paul Yancich. Our musical collaborations have resulted in the creation of a variety of new work, ranging from the seminal chamber piece composed for his senior recital at the Cleveland Institute of Music to full orchestral scores premiered by leading American orchestras. This oeuvre is now augmented by Legacy Ascendant, the third concerto in our shared timpanic trilogy.

The world premiere of Legacy Ascendant by The Cleveland Orchestra provides a bookend symmetry to the debut of my first timpani concerto, The Olympian, which received its initial performances in Cleveland in 1990. In the middle came the DYNASTY Double Timpani Concerto, composed for Paul and his timpanist brother Mark Yancich, premiered by their respective orchestras in Cleveland and Atlanta during the 2011–12 concert season. Symmetry has also played an important, albeit largely unnoticed, role in my compositional process. Typically, I create a palindromic framework of metric architecture (i.e., time signatures) and then weave thematic materials across this underlying structure much like vines growing organically over a foundational lattice.

Another consistent factor in the composition of my timpani concertos has been the prominence given to the

harp in each of the scores. Both the timpani and the harp are pedal-empowered, meaning that the performers must change their instrument’s pitches with foot pedals in real time even while the music is being played. Legacy Ascendant continues this tradition, featuring the harp in a variety of significant passages, oftentimes accompanying, or being accompanied by, the timpani.

The first movement, Then, is comprised of two primary sections sequenced into a tripart structure. After a brief introduction, the first section emerges with an irrepressible forward-moving energy, featuring melodic motifs introduced by the timpani and then embellished by the strings. This forward motion eventually subsides into a gentle nostalgia initially invoked by the solo harp, and then developed in melodic dialogue with the timpani. The strings join and begin to intertwine in simultaneous variations on

the thematic material, creating a rich texture of individual lines. Inevitably, the rambunctious energy of the opening section reawakens, and propels us toward a conclusion sealed with an emphatic exclamation from the timpani.

Halcyon opens with a solo passage for the harp, flowing directly into the first statement of the movement’s main theme by the timpanist. The motif is then offered again with a variation in 5/8 time, initially accompanied by the strings in pizzicato articulations, then taken up and developed in bowed lines by the violin and viola sections. A brief polyphonic passage emerges in which phrases from the main theme are referenced in dialogue amongst the various voices of the ensemble. The subsequent rhythmic interchange between pizzicato strings and timpani shifts the conversation into a dynamic call and response, which concludes with a timpani cadenza. In this solo passage, the melodic capabilities of the instrument are highlighted, including an example of two-voice timpani writing. When the orchestra reenters, the rich multi-voice conversation begins anew, culminating in a staccato transition that pits the main theme against a polyrhythmic backdrop. The solo harp returns to usher in a penultimate thematic statement from the timpani soloist. The Halcyon motif is then shared one last time in a simple duet between the harp and timpani.

The third movement, Once Again, begins with the subtle articulation of a single pitch, expanding into a cluster of tones that support the timpani’s initial melodic offering. Viola and cello soloists briefly invoke a theme heard previously in the concerto’s opening movement before gliding into the first of several rhythmic passages. The musical interval of the minor seventh is stated and expounded upon by the timpani soloist through a series of variations. Incorporating stylistic influences from both jazz and American popular music idioms, the collective texture of individual instrumental lines become increasingly more complex until the competing forces converge into a staccato tutti that leads to the second cadenza of the concerto, a “signature” passage of the soloist’s own devising.

At the conclusion of the “signature” cadenza, the harp and strings reenter to motivate a reprisal of thematic material originally introduced by viola and cello soloists near the beginning of the movement. This time, however, soloists from each of the individual string sections respond to the timpanist’s melodic offerings to weave a multicolored sonic tapestry across the closing moments of the concerto. Each of these brief solo statements were conceived to be reminiscent of those we have known, loved, and perhaps lost; moments, memories, and meanings that comprise our own personal legacy.

James OliverioBORN : March 31, 1732, in Rohrau, Austria

DIED: May 31, 1809, in Vienna Ω COMPOSED : 1788 Ω

WORLD PREMIERE: Paris, 1788 or 1789 Ω

CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE: This is only the second time The Cleveland Orchestra has presented this symphony at Severance, following a series of performances led by Louis Lane in December 1967. Ω

ORCHESTRATION: flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings Ω DURATION: 25 minutes

HAYDN WROTE SIX “Paris” symphonies (Nos. 82 through 87) and 12 “London” symphonies (Nos. 93 through 104). Between them came five symphonies which could perhaps be classed as further Paris symphonies since they had close connections with that city. The first two (Nos. 88 and 89) were commissioned in 1787 by an adventurer who played the violin in Haydn’s orchestra at Esterházy, Johann Tost. Tost set off for Paris to seek his fortune armed with two new Haydn symphonies and another by Gyrowetz, which he managed to pass off to a French publisher as also the work of Haydn.

The next three were commissioned by Claude-François-Marie Rigoley, Comte d’Ogny, a French aristocrat who was

born a few days before Mozart, and who died even younger, in 1790. He played an important part in Parisian music in the years before the Revolution, having founded in 1782 the Loge Olympique, whose purpose was to give regular concerts in the Tuileries Palace. He assembled a large music library and managed to retain his position as Postmaster-General even after the fall of the Bastille in 1789. The library was eventually dispersed, with the manuscript of Symphony No. 90 ending up in the Library of Congress.

Comte d’Ogny, who commissioned the “Paris” Symphonies, was so gratified by the six works Haydn wrote for him in 1785 that he commissioned three more in 1788 (Nos. 90, 91, and 92). At the same

time (while Mozart, as it happens, was composing his great three final symphonies, Nos. 39, 40, and 41, without any financial sponsor), Haydn received a commission for three symphonies from a German patron, the Prince of OettingenWallerstein, so he was conveniently able to double his money with the same merchandise.

Haydn was fond of beginning his symphonies with slow, often solemn, introductions. In the case of Symphony No. 90, he anticipates Romantic compos-

ers like Liszt in giving a foretaste of his Allegro in the Adagio that precedes it. Beethoven picked up on this idea in his “Pathétique” Sonata. The Allegro itself exhibits a variety of lively ideas, including a second subject given to the flute and answered by the oboe (their roles are reversed in the recapitulation), a torrent of scales for all the strings together, and the neat management of the main theme so that it is both an opening theme and a closing cadence.

The Andante is cast as a double set of variations, one of Haydn’s favorite forms. The first theme is in F major, made up of two repeated halves; the second is in F minor, again consisting of two repeated halves, and featuring some striking silences. The variations alternate, although there is space for only two variations of the major theme and one of the minor theme.

Trumpets and drums return for the Minuet, considered by some critics to suggest the stately style of the French court, although Haydn had no need to flatter his patron in this way. The Trio is a delicious solo for the oboe, and the Finale is playful and ingenious in Haydn’s typical manner. If he felt any need for stateliness, he provided it here when the full orchestra hammers out chords of C major as if to apologize for so much irresistible merriment.

— Hugh MacdonaldBORN : June 9, 1865, in Sortelung, Denmark

DIED: October 3, 1931, in Copenhagen Ω COMPOSED : 1910–11 Ω

WORLD PREMIERE: February 28, 1912, with the Royal Orchestra in Copenhagen, Denmark, conducted by the composer Ω

CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE: February 1966, at a series of concerts led by Louis Lane Ω

ORCHESTRATION: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (3rd doubling english horn), 3 clarinets, 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings, plus soprano and bass soloists in the second movement only. Nielsen provided an alternate version of the score with clarinets playing the vocal lines. Ω DURATION: about 40 minutes

OVER THE CENTURIES , Western classical music has moved like a tidal wave from the Mediterranean, breaking in Italy and then sweeping across France, Austria, and Germany before lapping at the shores of the British Isles and Scandinavia. Each country changed the course of that wave as it passed, and, in the past century or so, it propelled England’s Edward Elgar, Norway’s Edvard Grieg, and Finland’s Jean Sibelius to permanent enshrinement in the concert hall.

After the mid-20th century, when the dominance of the Schoenberg 12-tone school over new music began to wane,

those northern countries kept contributing to the eclectic mix that followed. Britain, for example, gave rise to a new generation of highly original composers, the richest harvest from the area since the Elizabethan age. Meanwhile, the Mahler revival of the 1960s sent concert programmers back to the music library in search of other composers from the “recent past” who might have something to teach us about new uses for the old language of tonal harmony. Northerners with roots in folk music, such as the Englishman Ralph Vaughan Williams and the Dane Carl Nielsen, could speak in

their distinctive voices to audiences from Tokyo to Madrid.

Carl Nielsen was born into a large, poor family in the hamlet of Sortelung, on the Danish island of Funen. His father, who eked out a living as a house painter and village fiddler, gave him what little early musical training he had. Young Carl discovered on his own the keyboard and string works of Bach, Haydn, and Mozart, and taught himself to play them. After attending the Copenhagen Conservatory on scholarship, Nielsen spent much of his middle and late 20s traveling to European capitals, educating himself in art, languages, and literature, and of course imbibing the latest developments in music.

But Mozart remained his first love, and as the century turned, Nielsen was already composing in the forms and the cadences of the Classical era — with a distinctly contemporary accent. Stravinsky’s stripped-down, parodic “neoclassicism” was still 20 years off, and Nielsen never had much to do with it. If he was “neo” anything, it was neoBeethoven, and even that was more a matter of attitude than of actual themes and sounds. For the kind of profoundly meaningful, philosophical music Nielsen aspired to create, the symphony was a natural choice.

In 1916, Nielsen, the onetime country bumpkin and scholarship student, returned in triumph to the Copenhagen Conservatory as a governor, teacher, and examiner. (He would become its director in 1931.) By virtue of his energy,

intelligence, warmth, and example as a composer, Nielsen was a natural leader. Through public speaking, conducting his own works and those of others, and tirelessly serving on boards and committees, he revitalized and set high standards for music, not just in his immediate circle but across all of Scandinavia. Like Vaughan Williams, Nielsen composed hymn tunes that encouraged congregational singing in his country’s churches. Vaughan Williams preserved folksongs and used them in some of his concert works; Nielsen, in an activity entirely separate from his Classical-inspired symphonies and chamber music, wrote and published dozens of new, easy-tosing settings of Danish verse, achieving nothing less than the reinvention of Danish folksong.

Nielsen was never attracted to the Romantic-Nationalist style, the musical pigeonhole from which Grieg and Sibelius struggled mightily to escape. Rather, his Danishness — his ability to evoke the warm and friendly atmosphere of the country that is “the South” of Scandinavia — is at least as deeply sublimated in his symphonies as German folk music is in Beethoven’s.

But there was, at first, a certain youthful desire to explain what he was up to. Although his Symphony No. 1 (1891–92) bears no title, Nielsen called his Symphony No. 2 (1901–02) “The Four Temperaments,” and explained in a program note that the work was inspired by a gaudy allegorical picture he saw on the wall of a Danish tavern.

He pulled back to a more philosophical stance in the titles of Symphonies No. 3 (“Sinfonia espansiva,” 1910–11) and No. 4 (“The Inextinguishable,” 1915–16), hinting that his subjects were, respectively, the beneficial power of the life force and its ability to overcome the challenge of death.

Symphony No. 3 begins with a lengthy passage of loud, turbulent music for full orchestra, but in melodic terms Nielsen is a Classical minimalist à la Haydn or Beethoven, building his structures out of the smallest motivic building blocks. “One must show the sated,” he once wrote, “that the melodic interval of a third should be considered a gift from

God, the fourth an experience, and a fifth the supreme happiness.”

Nielsen’s Third Symphony is “expansive” in terms of showing how much can be accomplished with a few simple materials. It takes an expansive view of human nature, pure and simple, making its way between earth and heaven.

Nielsen combined his Northern personality with a modern quest for objectivity, and he saw the symphony as a rigorous medium. As befitted a disciple of Mozart, he sought out the clear and the colorful in his orchestrations.

Nielsen’s hopeful yet unsentimental stance can be a tonic for our troubled new century. He shares with Bruckner not only peasant origins, but a mode of expression that is lucid and direct, sincere and selfless — something of a miracle in the ironic, self-indulgent age of Mahler and Strauss during which he wrote. If his music occasionally has a hard, unyielding feeling, it may be because of his desire to create an indestructible gem of expression. In 1890, when Nielsen was 25 years old, he wrote in his diary: “I’ve come to the conclusion that [Carl Maria von] Weber will be forgotten in a hundred years’ time. There is something jelly like about a lot of his music. It is a fact

that he who brandishes the hardest fist will be remembered longest. Beethoven, Michelangelo, Bach, Berlioz, Rembrandt, Shakespeare, Goethe, Henrik Ibsen, and the like have all given their time a black eye.”

A century later, Weber is a resurgent star in concert halls, while this Northern symphonist, once lionized in his home country then neglected after his death, is finally standing before us as just himself, with his fist cocked.

Symphony No. 3 opens somewhat in the manner of another expansive third symphony, Beethoven’s “Eroica.” But here, instead of hammering on the movement’s home chord, Nielsen turns the repeated note A into a stuttering upbeat to a theme in D minor. The vigorous but wayward movement in 3/4 meter has been compared to waltz parodies composed around the same time, such as Ravel’s La Valse and Stravinsky’s Pétrouchka — but to call such swashbuckling music a waltz is a bit of a stretch.

The second movement, marked Andante pastorale, begins in an atmosphere as vague and static as the first movement was hard-edged and active. But soon the “pastoral” arrives in the form of a pretty flute tune that intertwines with itself, then alternates with a fervent theme for strings. The movement eventually winds down to a coda on the chord of E-flat major, as peaceful as the symphony’s opening was furious, and as harmonically distant from those loud opening As as it is possible to get. In a

strikingly original touch, two wordless human voices are heard wheeling around ecstatically in the glow of E-flat.

We are awakened from this heavenly vision by a rather sarcastic little thirdmovement scherzo, which often seems to anticipate Shostakovich in its mechanical gestures and sneering wind sounds. Nielsen said he thought of the theme while riding a train and wrote it on his shirt cuff. Perhaps that is what he meant when he called this movement “the heartbeat of the symphony,” because it clicks along at a steady pace.

Ever the lover of contrasts, the composer follows his acidic scherzo with a fourth-movement Finale that opens in a hearty, friendly mood with a forthright theme in the tradition of Beethoven’s

Ninth or Brahms’s First. The movement’s hopping second theme is derived from this main theme, as are all the colorful episodes, so that the overall effect is of a free-form theme and variations. Even at the two points where the theme seems to return in full, Nielsen changes its shape a little and reharmonizes it to reflect what has gone before — and also where he’s taking us, which is a coda firmly in A major. Thus, the symphony ends as it began, on a loud unison A, but this time it’s an arrival, not a departure.

David Wright is a contributor to New York Classical Review. He has written program notes for Lincoln Center, the New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, and many other organizations.

Adella, our streaming service and app, features on-demand portraits, music showcases, behind-the-scenes footage and our flagship In Focus premium concert series, available anytime & anywhere.

Visit Adella.live to start your free trial.

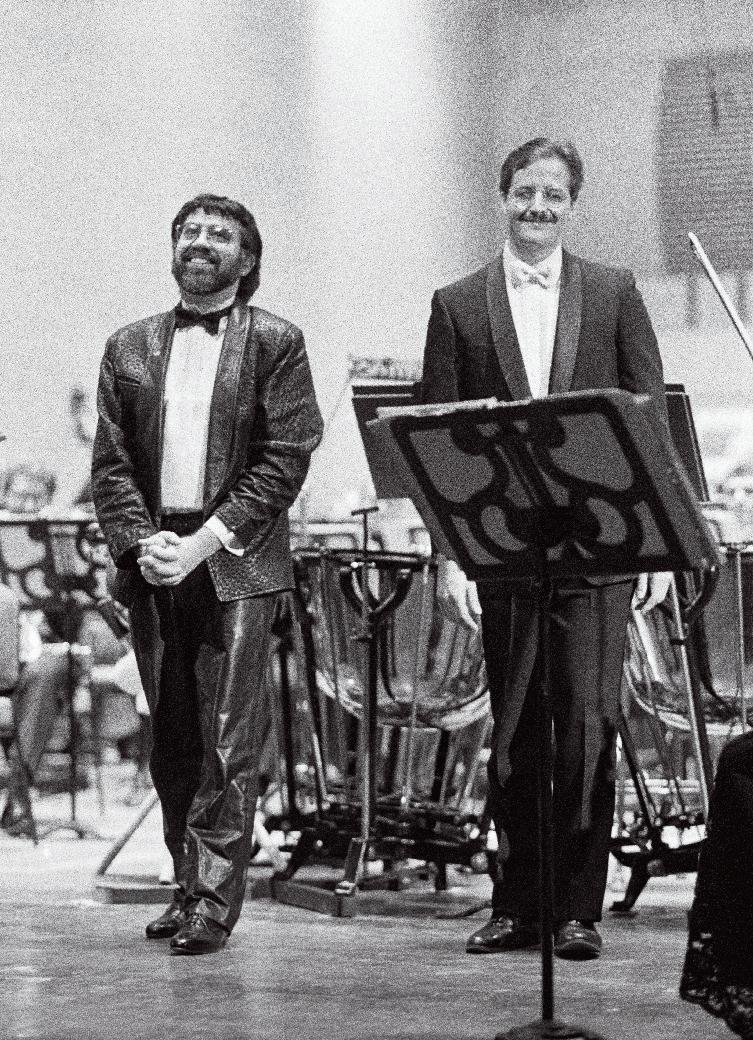

PHOTO BY PETER HUNDERT

Gilbert

PHOTO BY PETER HUNDERT

Gilbert

GRAMMY AWARD–WINNING conductor

Alan Gilbert has been chief conductor of Hamburg’s NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra since fall 2019 and music director of the Royal Swedish Opera since spring 2021. Having served for more than a decade as principal guest conductor of NDR Symphony Orchestra (as the German ensemble was formerly known), he is now taking the ensemble to new artistic heights through adventurous programming, thought-provoking festivals, and regular online streaming. He also holds positions as principal guest conductor of the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony and conductor laureate of the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra.

Previously, he served an eight-year tenure as music director of the New York Philharmonic. The first native New Yorker to hold the post, he succeeded not only in making “an indelible mark on the orchestra’s history and that of the city itself” (The New Yorker), but also in “building a legacy that matters and... helping to change the template for what an American orchestra can be” (The New York Times). He has led productions at LA Opera, the Metropolitan Opera, Santa Fe Opera (where he served as the first appointed music director), and Zurich Opera.

In addition to these appointments, Mr. Gilbert maintains a major international presence, making guest appearances with orchestras including Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, Boston Symphony

Orchestra, Dresden Staatskapelle, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Philadelphia Orchestra, and The Cleveland Orchestra, where he was an assistant conductor from 1995 to 1997.

Highlights of his 2022–23 season include the inaugural edition of Elbphilharmonie Visions, a biennial 10-day celebration of 21st-century music that sees Mr. Gilbert and the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra premiere a new commission from Lisa Streich and perform works by Hans Abrahamsen, Brett Dean, and Anna Thorvaldsdóttir. The NDR season also features collaborations with Julia Bullock and Alisa Weilerstein. He leads three productions at the Royal Swedish Opera, opening with Katharina Jakhelln Semb’s staging of Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos, and conducts the Berlin Philharmonic with Joshua Bell at the orchestra’s 2023 Biennale.

Paul Yancich was appointed The Cleveland Orchestra’s principal timpanist by Lorin Maazel in 1981. He first appeared as soloist with the Orchestra in 1990, performing the world premiere of James Oliverio’s Timpani Concerto No. 1 (The Olympian). In 2011, he performed the world premiere of Oliverio’s DYNASTY Double Timpani Concerto with his brother, Mark Yancich, in Atlanta and Cleveland. His most recent appearances as soloist with the Orchestra were in 2013, in Johann Carl Christian Fischer’s Symphony with Eight Obbligato Timpani. In 2018, he performed Philip Glass’s Concerto Fantasy for Two Timpanists at Carnegie Hall with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra.

A native of Rochester, New York, and a student of the Rochester public school system, Mr. Yancich is in the fourthgeneration of a family of professional musicians. His teachers include Cloyd

Duff, Richard Weiner (both former principals of The Cleveland Orchestra), Saul Goodman, William Street, and Bill Cahn. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Case Western Reserve University and a Bachelor of Music degree from the Cleveland Institute of Music. Mr. Yancich has been co-chair of the percussion department at the Cleveland Institute of Music since 1981 and served as music director of the CIM Percussion Ensemble for 20 years. His timpani and percussion students perform in more than 40 orchestras in the United States and abroad.

Liv Redpath is a leading soprano leggero on opera and concert stages across the globe. She opened her 2022–23 season singing the title role in the new

Simon Stone production of Lucia di Lammermoor at LA Opera led by Lina González-Granados. She will make debuts at Komische Oper Berlin as Ophélie in a new production of Hamlet; at the Glyndebourne Festival in the role of Tytania in Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with director Peter Hall and Dalia Stasevska conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra; and at La Monnaie/De Munt in Brussels, where she returns to the role of Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier.

Concert appearances include Handel’s Messiah with the National Symphony Orchestra under Fabio Biondi; Orff’s Carmina Burana with Utah Symphony led by Fawzi Haimor; Nielsen’s Hymnus Amoris and Symphony No. 3 with the Danish National Symphony Orchestra led by Fabio Luisi; and Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis at Aix-en-Provence, with Balthasar Neumann Ensemble and Choir conducted by Thomas Hengelbrock. Ms. Redpath will also join the Orchestra of St. Luke’s to sing music of Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn with guest pianist David Fung.

also covering the lead role of Charles Blow in Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones. Other highlights include his debut at Washington National Opera as Thomas McKeller in the world premiere of American Apollo by Damien Geter and Lila Palmer; the starring role of George Armstrong in Lynn Nottage’s and Ricky Ian Gordon’s Intimate Apparel at Lincoln Center; and solo debuts at Carnegie Hall, the Glimmerglass Festival, and Strathmore Music Center. Mr. Austin is a graduate of the Choir Academy of Harlem, LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts, Heidelberg Lied Akademie, and the Manhattan School of Music. He strongly believes in utilizing his artistry to benefit music programs and community services around the world, and works with various organizations to create and perform benefit concerts.

Praised for his “mellifluous baritone” (The Wall Street Journal), Justin Austin performs a wide range of repertoire, from opera and oratorio to jazz, R&B, and musical theater. Last season, he made his house debut at the Metropolitan Opera as Marcellus in the company premiere of Brett Dean’s Hamlet, while

NOW IN ITS SECOND CENTURY , The Cleveland Orchestra, under the leadership of music director Franz WelserMöst since 2002, is one of the most sought-after performing ensembles in the world. Year after year, the ensemble exemplifies extraordinary artistic excellence, creative programming, and community engagement. The New York Times has called Cleveland “the best in America” for its virtuosity, elegance of sound, variety of color, and chamberlike musical cohesion.

Founded by Adella Prentiss Hughes, the Orchestra performed its inaugural concert in December 1918. By the middle of the century, decades of growth and sustained support had turned it into one of the most admired globally.

The past decade has seen an increasing number of young people attending concerts, bringing fresh attention to The Cleveland Orchestra’s legendary sound and committed programming. More recently, the Orchestra launched several bold digital projects, including the streaming broadcast series In Focus, the podcast On a Personal Note, and its own recording label, a new chapter in the Orchestra’s long and distinguished recording and broadcast history. Together, they have captured the Orchestra’s unique artistry and the musical achievements of the Welser-Möst and Cleveland Orchestra partnership.

The 2022/23 season marks Franz Welser-Möst’s 21st year as music director, a period in which The Cleveland Orchestra earned unprecedented acclaim around the world, including a series of residencies at the Musikverein in Vienna, the first of its kind by an American orchestra, and a number of acclaimed opera presentations.

Since 1918, seven music directors — Nikolai Sokoloff, Artur Rodziński, Erich Leinsdorf, George Szell, Lorin Maazel, Christoph von Dohnányi, and Franz Welser-Möst — have guided and shaped the ensemble’s growth and sound. Through concerts at home and on tour, broadcasts, and a catalog of acclaimed recordings, The Cleveland Orchestra is heard today by a growing group of fans around the world.

David Radzynski

CONCERTMASTER Blossom-Lee Chair

Peter Otto

FIRST ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER Virginia M. Lindseth, PhD, Chair

Jung-Min Amy Lee ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER Gretchen D. and Ward Smith Chair Jessica Lee

ASSISTANT CONCERTMASTER

Clara G. and George P. Bickford Chair

Stephen Tavani ASSISTANT CONCERTMASTER Wei-Fang Gu Drs. Paul M. and Renate H. Duchesneau Chair Kim Gomez Elizabeth and Leslie Kondorossy Chair Chul-In Park

Harriet T. and David L. Simon Chair

Miho Hashizume

Theodore Rautenberg Chair

Jeanne Preucil Rose Larry J.B. and Barbara S. Robinson Chair Alicia Koelz

Oswald and Phyllis Lerner Gilroy Chair

Yu Yuan

Patty and John Collinson Chair

Isabel Trautwein

Trevor and Jennie Jones Chair

Katherine Bormann

Analisé Denise Kukelhan Gladys B. Goetz Chair Zhan Shu

Stephen Rose*

Alfred M. and Clara T. Rankin Chair Eli Matthews1 Patricia M. Kozerefski and Richard J. Bogomolny Chair

Sonja Braaten Molloy Carolyn Gadiel Warner Elayna Duitman

Ioana Missits

Jeffrey Zehngut

Sae Shiragami Kathleen Collins Beth Woodside

Emma Shook Dr. Jeanette Grasselli Brown and Dr. Glenn R. Brown Chair Yun-Ting Lee Jiah Chung Chapdelaine

Wesley Collins* Chaillé H. and Richard B. Tullis Chair

Lynne Ramsey1 Charles M. and Janet G. Kimball Chair

Stanley Konopka2 Mark Jackobs Jean Wall Bennett Chair

Lisa Boyko Richard and Nancy Sneed Chair Richard Waugh Lembi Veskimets

The Morgan Sisters Chair Eliesha Nelson Joanna Patterson Zakany William Bender Gareth Zehngut

Mark Kosower* Louis D. Beaumont Chair

Richard Weiss1

The GAR Foundation Chair

Charles Bernard2 Helen Weil Ross Chair

Bryan Dumm Muriel and Noah Butkin Chair

Tanya Ell Thomas J. and Judith Fay Gruber Chair

Ralph Curry Brian Thornton William P. Blair III Chair

David Alan Harrell Martha Baldwin Dane Johansen Paul Kushious

Maximilian Dimoff* Clarence T. Reinberger Chair

Derek Zadinsky2 Mark Atherton

Thomas Sperl Henry Peyrebrune Charles Barr Memorial Chair

Charles Carleton Scott Dixon Charles Paul HARP

Trina Struble* Alice Chalifoux Chair

Joshua Smith* Elizabeth M. and William C. Treuhaft Chair Saeran St. Christopher Jessica Sindell2 Austin B. and Ellen W. Chinn Chair Mary Kay Fink

PICCOLO Mary Kay Fink Anne M. and M. Roger Clapp Chair

Frank Rosenwein* Edith S. Taplin Chair Corbin Stair Sharon and Yoash Wiener Chair

Jeffrey Rathbun2 Everett D. and Eugenia S. McCurdy Chair Robert Walters

Robert Walters Samuel C. and Bernette K. Jaffe Chair

Afendi Yusuf* Robert Marcellus Chair Robert Woolfrey Victoire G. and Alfred M. Rankin, Jr. Chair

Daniel McKelway2 Robert R. and Vilma L. Kohn Chair Amy Zoloto

E-FLAT CLARINET

Daniel McKelway Stanley L. and Eloise M. Morgan Chair

BASS CLARINET

Amy Zoloto Myrna and James Spira Chair

John Clouser* Louise Harkness Ingalls Chair

Gareth Thomas Barrick Stees2 Sandra L. Haslinger Chair Jonathan Sherwin

CONTRABASSOON Jonathan Sherwin

Nathaniel Silberschlag* George Szell Memorial Chair

Michael Mayhew§

Knight Foundation Chair

Jesse McCormick

Robert B. Benyo Chair

Hans Clebsch

Richard King

TRUMPETS

Michael Sachs* Robert and Eunice Podis Weiskopf Chair

Jack Sutte

Lyle Steelman2 James P. and Dolores D. Storer Chair

Michael Miller

CORNETS

Michael Sachs* Mary Elizabeth and G. Robert Klein Chair Michael Miller

TROMBONES

Brian Wendel*

W. and Louise I. Humphrey Chair

Richard Stout Alexander and Marianna C. McAfee Chair

Shachar Israel2

EUPHONIUM & BASS TRUMPET

Richard Stout

TUBA

Yasuhito Sugiyama* Nathalie C. Spence and Nathalie S. Boswell Chair

Paul Yancich* Otto G. and Corinne T. Voss Chair

Marc Damoulakis*

Margaret Allen Ireland Chair

Donald Miller

Thomas Sherwood

Carolyn Gadiel Warner Marjory and Marc L. Swartzbaugh Chair

LIBRARIANS

Michael Ferraguto

Joe and Marlene Toot Chair

Donald Miller

ENDOWED CHAIRS

CURRENTLY UNOCCUPIED

Elizabeth Ring and William Gwinn Mather Chair

Paul and Lucille Jones Chair

James and Donna Reid Chair

Mary E. and F. Joseph Callahan Chair

Sunshine Chair

Mr. and Mrs. Richard K. Smucker Chair Rudolf Serkin Chair

This roster lists full-time members of The Cleveland Orchestra. The number and seating of musicians onstage varies depending on the piece being performed. Seating within the string sections rotates on a periodic basis.

Alan Gilbert, conductor

Paul Yancich, timpani

Liv Redpath, soprano Justin Austin, baritone

OLIVERIO Legacy Ascendant HAYDN Symphony No. 90 NIELSEN Symphony No. 3 (“Sinfonia espansiva”)

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Joélle Harvey, soprano

Daryl Freedman, mezzo-soprano

Julian Prégardien, tenor

Martin Mitterrutzner, tenor

Dashon Burton, bass-baritone

Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

BERG Lyric Suite*

SCHUBERT Symphony No. 8* (“Unfinished”)

SCHUBERT Mass No. 6

* The movements of the Lyric Suite will be performed in rotation with Symphony No. 8

Klaus Mäkelä, conductor

NORMAN Sustain DEBUSSY Images

RAVEL Boléro

Klaus Mäkelä, conductor

CHIN SPIRA—Concerto for Orchestra

MAHLER Symphony No. 5

FEB 16, 17, 18

Herbert Blomstedt, conductor

Emanuel Ax, piano

MOZART Piano Concerto No. 18 (“Paradis”)

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7

23, 24,

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

MOZART Divertimento No. 2*

SCHOENBERG Variations for Orchestra

STRAUSS Ein Heldenleben

* not part of Friday Matinee concert

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Víkingur Ólafsson, piano

FARRENC Symphony No. 3

RAVEL Piano Concerto in G major MUSSORGSKY/RAVEL Pictures at an Exhibition

9, 10, 11, 12

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Christoph Sietzen, percussion

Siobhan Stagg, soprano

Avery Amereau, alto

Ben Bliss, tenor

Anthony Schneider, bass

Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

STAUD Concerto for Percussion

MOZART Requiem

Thomas Adès, conductor

Pekka Kuusisto, violin

ADÈS The Tempest Symphony ADÈS Märchentänze

SIBELIUS Six Humoresques* SIBELIUS Prelude and Suite No. 1 from The Tempest* * Certain selections will not be part of the Friday Matinee concert

Rafael Payare, conductor Jean-Yves Thibaudet, piano BERNSTEIN Symphony No. 2 (“The Age of Anxiety”) SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No. 5

Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor Leif Ove Andsnes, piano DEBUSSY Jeux, poème dansé DEBUSSY Fantaisie for Piano and Orchestra

MAHLER Symphony No. 1 (“Titan”)

Bernard Labadie, conductor Lucy Crowe, soprano

MOZART Overture to La clemenza di Tito MOZART “Giunse al fin il momento... Al desio di chi t’adora” MOZART Ruhe Zanft from Zaide MOZART Masonic Funeral Music MOZART “Venga la morte... Non temer, amato bene” MOZART Symphony No. 41 (“Jupiter”)

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor Michael Sachs, trumpet MARTINŮ Symphony No. 2 MARSALIS Trumpet Concerto DVOŘÁK Symphony No. 9 (“From the New World”)

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor Alisa Weilerstein, cello LOGGINS-HULL Can You See? BARBER Cello Concerto PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 4

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor Tamara Wilson, soprano (Minnie) Eric Owens, bass (Jack Rance) Limmie Pulliam, tenor (Dick Johnson)

Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

PUCCINI La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West) * Opera presentation, sung in Italian with projected supertitles

The Cleveland Orchestra is committed to creating a comfortable, enjoyable, and safe environment for all guests at Severance Music Center. While mask and COVID-19 vaccination are recommended they are not required. Protocols are reviewed regularly with the assistance of our Cleveland Clinic partners; for up-to-date information, visit: clevelandorchestra. com/attend/health-safety

As a courtesy to the audience members and musicians in the hall, late-arriving patrons are asked to wait quietly until the first convenient break in the program. These seating breaks are at the discretion of the House Manager in consultation with the performing artists.

As a courtesy to others, please silence all devices prior to the start of the concert.

Audio recording, photography, and videography are prohibited during performances at Severance. Photographs can only be taken when the performance is not in progress.

For the comfort of those around you, please reduce the volume on hearing aids and other devices that may produce a noise that would detract from the program. For Infrared Assistive-Listening Devices, please see the House Manager or Head Usher for more details.

Contact an usher or a member of house staff if you require medical assistance. Emergency exits are clearly marked throughout the building. Ushers and house staff will provide instructions in the event of an emergency.

Regardless of age, each person must have a ticket and be able to sit quietly in a seat throughout the performance. Classical season subscription concerts are not recommended for children under the age of 8. However, there are several age-appropriate series designed specifically for children and youth, including Music Explorers (for 3 to 6 years old) and Family Concerts (for ages 7 and older).

The Cleveland Orchestra is grateful to the following organizations for their ongoing generous support of The Cleveland Orchestra: the State of Ohio and Ohio Arts Council and to the residents of Cuyahoga County through Cuyahoga Arts and Culture.

The Cleveland Orchestra is proud of its long-term partnership with Kent State University, made possible in part through generous funding from the State of Ohio. The Cleveland Orchestra is proud to have its home, Severance Music Center, located on the campus of Case Western Reserve University, with whom it has a long history of collaboration and partnership.

© 2022 The Cleveland Orchestra and the Musical Arts Association Program books for Cleveland Orchestra concerts are produced by The Cleveland Orchestra and are distributed free to attending audience members.

EDITOR Amanda Angel Managing Editor of Content aangel@clevelandorchestra.com

DESIGN Elizabeth Eddins, eddinsdesign.com

ADVERTISING Live Publishing Company, 216-721-1800

We believe that all Cleveland youth should have access to high-quality arts education. Through the generosity of our donors, we are investing to scale up neighborhoodbased programs that now serve 3,000 youth year-round in music, dance, theater, photography, literary arts and curatorial mastery. That’s a symphony of success. Find your passion, and partner with the Cleveland Foundation to make your greatest charitable impact.

(877) 554-5054 www.ClevelandFoundation.org