Trifonov Plays Brahms

Experience The Cleveland Orchestra’s digital platform with new & improved features.

Experience on-demand concerts with exclusive interviews and behind-the-scenes features, starting with Mozart’s Requiem (available now) and Weilerstein Plays Barber (October 24).

NEW Live-Streamed Concerts

Enjoy six concerts broadcast live from Severance throughout the 2023 – 24 season.

By popular demand, stream exclusive recordings from The Cleveland Orchestra’s audio archives.

Access videos and learning resources for children, students, and teachers. Visit stream.adella.live/premium or scan the QR code to secure your subscription today!

Questions? Email adellahelp@clevelandorchestra.com

I’m delighted to welcome you to Severance Music Center for an exciting start to The Cleveland Orchestra’s 2023–24 season. This coming year’s programming is some of the most ambitious and diverse we’ve had in recent memory. Along with beloved works from the repertoire are premieres by today’s most influential composers, choral performances, family and education concerts, Hollywood films, and a recital series featuring the world’s most renowned musical stars. The season will culminate with the second Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Opera & Humanities Festival featuring a staged production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s The Magic Flute. There is truly something on the calendar for every music lover.

We began this wonderful year of music with the film Amadeus, a testament to the power and genius of Mozart. What a treat to see this Oscar-winning movie with one of the world’s greatest orchestras performing the all-Mozart score.

This weekend, Music Director Franz Welser-Möst leads the Orchestra and the brilliant pianist Daniil Trifonov, making his highly anticipated return to Cleveland, in Brahms’s First Piano Concerto. Daniil is just the first of many eminent musicians to join us this season — there are too many to list here — but I do hope that you’ll come to Severance often to hear these incredible artists.

In Amadeus, the fictional Salieri describes Mozart’s music as nothing less than “miraculous.” I truly believe that this word aptly describes each concert this season. We can find these miracles embedded in works of musical genius, displayed by the astounding talent on stage, or in the way more than a hundred musicians combine in unified harmony to produce a deeply profound experience.

The Cleveland Orchestra understands the unparalleled ability of music to create these everyday miracles — whether on stage, in a classroom, among loved ones, or in private introspection. As we inaugurate our 106th season, we are committed to fostering these experiences among our friends and neighbors in Northeast Ohio as well as around the world.

André GremilletThis coming year’s programming is some of the most ambitious and diverse we’ve had in recent memory.

Thursday, September 28, 2023, at 7:30 PM

Sunday, October 1, 2023, at 3 PM

Johannes Brahms (1833 –1897)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

Piano Concerto No. 1

45 minutes in D minor, Op. 15

I. Maestoso

II. Adagio

III. Rondo: Allegro non troppo

Daniil Trifonov, piano

INTERMISSION 20 minutes

Symphony No. 6 45 minutes in E-flat minor, Op. 111

I. Allegro moderato

II. Largo

III. Vivace

Total approximate running time: 1 hour 50 minutes

Sunday’s concert will be livestreamed on Adella.live in partnership with Deutsche Grammophon.

Thank you for silencing your electronic devices.

Daniil Trifonov’s performance is supported by a generous gift from the Gerhard Foundation.

Thursday evening’s performance is dedicated to Suzanne and Paul Westlake in recognition of their generous support of music.

LERNER GALLERY

Over the past 30 years, Cleveland-based photographer Roger Mastroianni has been documenting The Cleveland Orchestra, onstage and off, in Cleveland and on tour. This show presents selections from both the Orchestra’s and Mastroianni’s archives from 1993 to the present, including the Severance renovation, notable performances, and intimate, behind-the-scenes moments.

HUMPHREY GREEN ROOM

In 1924, the Orchestra made its first commercial recording: a brisk and truncated rendition of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. This exhibition traces Cleveland’s celebrated recording legacy, featuring milestones of previous music directors, as well as an extensive look at the output under Franz Welser-Möst’s leadership.

THE MAGICBOX , outside the Grand Foyer

Travel across the globe through the Orchestra’s extensive touring history. This interactive display showcases videos and fascinating artifacts from the Orchestra’s visits across five continents, such as a travel bag from Qantas made especially for the Orchestra’s Australian tour.

Franz Welser-Möst returns to Severance Music Center to lead The Cleveland Orchestra in two masterpieces by Johannes Brahms and Sergei Prokofiev: the first is a romantic fulfillment of youthful promise, and the second, a mature statement from a modern master.

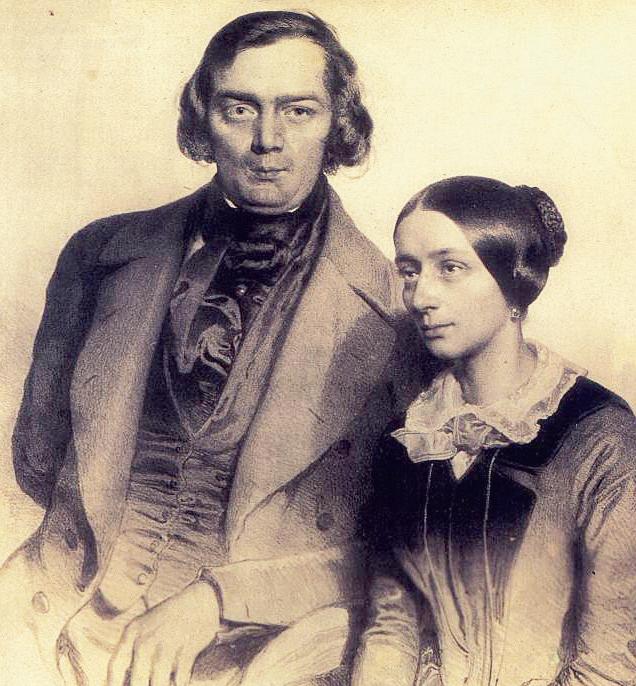

Brahms was 20 years old when he met the composers Robert and Clara Schumann and they quickly recognized his genius. Shortly after, Robert attempted suicide by jumping off a bridge into the Rhine. He was rescued from the river but admitted into an asylum, where he would die two years later.

Brahms returned to Düsseldorf to help support Clara. It’s at this time that he began work on the first large-scale composition of his career, pouring his emotion and ambition into what would become his Piano Concerto No. 1.

The concerto’s agitated opening alludes to Robert’s disquieting suicide attempt, the second-movement Adagio paints a tender portrait of Clara, and the finale fittingly borrows from Beethoven. It was Robert Schumann who marked Brahms as Beethoven’s natural successor, and this work, performed this weekend by the extraordinary soloist Daniil Trifonov, crackles with realized potential.

Nearly 90 years later, 56-year-old Sergei Prokofiev, an elder statesman of Soviet composers, finished his penultimate symphony, the Sixth, in 1947. Having witnessed both the mass devastation wrought by World War II and ensuing victory by the Allies, the composer struggled to reconcile tragedy with triumph in this work. Shades of melancholy explode into fury or melt into aching sweetness. Upon the symphony’s US premiere in 1949, Musical America called it the “most personal, the most accessible, and emotionally revealing work of [Prokofiev] that has yet been played in this country.”

Unlike the Fifth, which was widely lauded, Prokofiev’s Sixth was condemned as formalist music. Although that determination was later rescinded, the work never achieved the same popularity as its predecessor. However, Welser-Möst and the Orchestra have been revisiting Prokofiev’s contributions to the symphonic genre. This weekend, they make the case for the tour-de-force Sixth, often considered the most profound of Prokofiev’s seven symphonies.

— Amanda AngelBORN : May 7, 1833, in Hamburg, Germany

DIED : April 3, 1897, in Vienna, Austria

▶ COMPOSED: 1854 – 58

▶ WORLD PREMIERE: January 22, 1859, in Hanover, Germany, conducted by Joseph Joachim with the composer as soloist

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE: April 14, 1927, conducted by Nikolai Sokoloff with Harold Bauer as soloist

▶ ORCHESTRATION: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings, plus solo piano

▶ DURATION: about 45 minutes

THE STORY HAS BEEN TOLD for going on two centuries, and its significance is unavoidable. In September 1853, a 20year-old music student from Hamburg knocked on the door of Robert and Clara Schumann’s home in Düsseldorf. Johannes Brahms felt shy, nervous, and tired from a long journey. His new friend, the celebrated violinist Joseph Joachim, had insisted he must introduce himself to the Schumanns and play them his music. Robert was a composer of then ambiguous reputation, but a well-known music critic; Clara had been since her teens one of the most celebrated pianists alive. Brahms played the couple a few of his pieces. When he left, Schumann wrote in his journal, “Visit from Brahms

(a genius).” The next few months transformed Brahms’s life. One of the fruits of that wonderful and terrible period was the First Piano Concerto. Soon after the Schumanns met and virtually adopted Brahms, Robert wrote an article called “New Paths” in which he declared this young man not only a genius but the coming savior of German music. The subtext of the article was that Brahms was expected to save music from the depredations, as Schumann saw it, of Wagner and Liszt. Their “Music of the Future” movement turned away from the formal models of Haydn, Mozart,

and Beethoven and replaced them with work based on stories, literature, and the like. Brahms, said Schumann, is “a real Beethovener,” true to traditional forms and values.

From Robert’s article many things flowed. Suddenly the whole of musical Europe knew the name Brahms. But Brahms understood all too well what Schumann had unintentionally done — thrown him up on a pedestal before he had proved himself, laid the salvation of Western music on his shoulders, and supplied him at the beginning of his public career with an army of enemies (the devotees of Wagner and Liszt).

As Brahms was trying to cope with that dilemma, he received news of something far worse: Robert Schumann had jumped off a bridge into the Rhine in a suicide attempt. Robert was pulled out of the river, but at his own request was placed in an asylum, where he died two years later. In that period, the most tumultuous of Brahms’s life, he and Clara fell in love (more or less unspoken), and he began to try and cope with the burden Robert had laid on him. It took him years to get back on his feet creatively. It was during those years that he painfully and painstakingly composed the First Piano Concerto.

The piece appears to have begun with the nightmare of Robert’s collapse. Within a week of Robert’s suicide attempt, Brahms had drafted three movements of a two-piano sonata in D minor. In the next months, the sonata turned into a draft of a symphony. In doing this,

he was following his mentor’s

in “New Paths,” Robert had declared that Brahms must start right out composing symphonies and other large works.

But the symphony refused to take wing. Finally, Brahms began over again with just the first movement, refashioning it as a piano concerto — an idea that came to him in a dream. The movement was his first piece for orchestra and by far the most ambitious thing he had attempted. Immediately, he found himself in over his head, struggling with writing for orchestra and managing a gigantic, complex form. Yet he kept pounding away at the piece. After nearly five excruciating years of struggling with this material, he finished the three movements of the D-minor Concerto, Op. 15, in spring 1858.

Why did he refuse to let go of the piece, for all it cost him? The best explanation is that he simply knew the first movement was too good to give up, but it could not stand on its own. It needed the rest of a concerto for balance and resolution.

What Brahms created remains one of the longest, most powerful, most formidable of all concertos. It begins on a note of high drama, an ominous low D in basses and snarling horns, with chains of trills above — not delicate Mozartean trills, but wild chromatic shiverings. That opening was the most turbulent in the repertoire to that time, with an expressive urgency that Brahms rarely attempted again and never surpassed. Surely the impetus for this work came

from Brahms’s youthful turmoil. If the vertiginous opening is applied to the image of a desperate man leaping into the water, it is almost cinematically apt.

After the searing opening pages, the monumental first movement unfolds in an atmosphere of high drama, not in programmatic but in abstract terms. This is a version of the usual concerto first-movement form: exposition, development, recapitulation, and coda. Also like most concertos in those days, Brahms created it as a vehicle for himself as virtuoso. There are some half-dozen themes, from fervent to lyrical and rhapsodic. In this approach, Brahms followed Mozart, whose mature concertos sprout multiple themes (though not ones as kaleidoscopic as these), some of them introduced and owned by the

soloist. Here it is as if the piano has to portray all the contending characters in a drama. The keyboard writing has the massive, two-fisted style to which Brahms returned in his Second Piano Concerto. This remains one of the longest of concerto movements, and physically and mentally one of the most demanding on the soloist.

Brahms told Clara Schumann that the gentle and hymnlike slow movement was “a tender portrait” of her. That is the best description of the music, much of which is unforgettably beautiful. Here, pictured in sound, is the Clara the young Brahms fell in love with — and never stopped loving, even though he remained a bachelor to the end. Built in simple A–B–A form with a solo cadenza, the second movement perhaps cost him less trouble than the first.

Then he had to contend with the last movement, often the most difficult

challenge in any large work, especially one with a massive and searing first movement. After that kind of opening, what can one do in the finale? Brahms decided on a traditional conclusion — a racing, rhythmically dynamic rondo outlined as A–B–A–C–A–B–A. The last movements of Classical concertos were traditionally light and lively rather than ponderous. Desperate to get the piece done, Brahms cribbed from the finale of Beethoven’s Concerto (No. 3) in C minor. “The two finales,” Charles Rosen wrote, “may be described and analyzed to a great extent as if they were the same piece.” The sound is Brahms, though, not Beethoven. The tone is a non-tragic D minor — youthful high spirits with a driving, demonic, Hungarian cast. Whether in the end the finale resolves the questions the first movement raises is a subject of long debate, but there is no question that it is brilliant and vivacious — and that for Brahms it got the gorilla off his back.

The first performance, in Hanover with Brahms at the piano, was received politely but with quiet perplexity. In its dark tone, symphonic style, and epic scale, this was a new kind of concerto. Then came the disastrous second performance in conservative Leipzig. At the conclusion of the performance, Brahms heard three hands brought together, followed by a wave of hisses. In a letter to Joseph Joachim he lightheartedly reported his “brilliant and decisive — failure.” He continued, “I believe this is the best thing that

could happen to one; it forces one to concentrate one’s thoughts and increases one’s courage. After all, I’m only experimenting and feeling my way as yet. But the hissing was too much of a good thing, wasn’t it?” And there you have Brahms’s sense of humor, often most acute when he was speaking of the things that hurt him most. In the wake of the Leipzig fiasco, he broke off an engagement — the only one he ever had — with a young singer and began to give up his hopes of being a true composer-pianist.

With his First Piano Concerto, Brahms started his orchestral career with a work of the scope and tone — and key — of the work that ended Beethoven’s symphonic career, the Ninth. The results were powerful and original, and he knew it. But his inexperience left its mark on the piece, and he knew that, too. He vowed never again to take on something of that size and ambition until he knew he was ready. He would not feel ready for another 18 years, when he finally finished the First Symphony. Nor did he ever again write quite so close to his rawest feelings. With youthful heedlessness, Brahms had launched into his first piano concerto. He never sailed blind again. But by the 1870s, he had the satisfaction of hearing this impassioned product of his youth cheered in concert halls all over Europe.

— Jan Swafford

BORN : April 23, 1891, in what is now Sontsivka, Ukraine

DIED : March 5, 1953, Moscow

BORN : April 23, 1891, in what is now Sontsivka, Ukraine

DIED : March 5, 1953, Moscow

▶ COMPOSED: 1944–47

▶ COMPOSED: 1944–47

▶ WORLD PREMIERE: October 10, 1947, with Yevgeny Mravinsky leading the Leningrad Philharmonic

▶ WORLD PREMIERE: October 10, 1947, with Yevgeny Mravinsky leading the Leningrad Philharmonic

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE: March 17, 1977, led by guest conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky

▶ CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PREMIERE: March 17, 1977, led by guest conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky

▶ ORCHESTRATION: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (snare drum, bass drum, woodblock, tam-tam, tambourine, cymbals, triangle), piano, celesta, harp, and strings

▶ ORCHESTRATION: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (snare drum, bass drum, woodblock, tam-tam, tambourine, cymbals, triangle), piano, celesta, harp, and strings

▶ DURATION: about 45 minutes

▶ DURATION: about 45 minutes

ON JANUARY 13, 1945 , Sergei Prokofiev conducted the first performance of his Fifth Symphony in Moscow. The new work was well received and continues to be popular today, rivaled in frequency in the concert hall only by his First Symphony, which he had named the Classical Symphony.

Composed during World War II, the Fifth might also be termed “classical” in its conventional form and in its abstract, non-storytelling qualities. It was and is, many people argue, what a symphony ought to be — the exploration of purely musical elements and their combination and relationships. In a sense, such pure

ON JANUARY 13, 1945 , Sergei Prokofiev conducted the first performance of his Fifth Symphony in Moscow. The new work was well received and continues to be popular today, rivaled in frequency in the concert hall only by his First Symphony, which he had named the Classical Symphony.

music could even be said to provide escapism in times of trouble.

The Romantic age of the 19th century has taught us, however, that a symphony does not have to be confined purely to musical argument. It can also relate to human experience and directly reference our feelings and experiences. Beethoven’s Fifth is surely about something, even if no one can say for certain what that something is outside of its musical journey from darkness to triumph.

Composed during World War II, the Fifth might also be termed “classical” in its conventional form and in its abstract, non-storytelling qualities. It was and is, many people argue, what a symphony ought to be — the exploration of purely musical elements and their combination and relationships. In a sense, such pure

music could even be said to provide escapism in times of trouble. The Romantic age of the 19th has taught us, however, that a does not have to be confined to musical argument. It can also to human experience and directly reference our feelings and experiences.

Beethoven’s Fifth is surely about something, even if no one can certain what that something is of its musical journey from darkness to triumph.

Shortly after composing his Sixth Symphony, Sergei Prokofiev was singled out by Soviet sensors for writing “formalist” music.

In Prokofiev’s case, his first foray in the Classical Symphony explored a modern take on a Haydn symphony. His Second presented the brutally mechanistic world of the 1920s, a world in which aircraft, motors, steam power, and general noise dictated the sonic environment. The Second was nonetheless still abstract in construction and conception.

The Third and Fourth had both been salvaged from — or at least borrowed music from — his operas, The Fiery Angel and The Prodigal Son, respectively. And the Fifth marked a return to a warmer, Romantic type of symphonic purity.

So what was to be expected from the Sixth? Prokofiev composed it soon after the Fifth and acknowledged that he was now reflecting on the devastation of World War II. That sentiment was powerfully clear at its first performance in 1947. (The parallels with British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams’s output is striking. His Fifth Symphony, premiered in 1943, refrained from any reference to the war, while his Sixth, from 1948, is deeply elegiac).

Barely months after the first performance of Prokofiev’s Sixth Symphony in the autumn of 1947, any euphoria the composer might have felt at the conclusion of the war and his new work’s warm reception was thrown to the wind when the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union issued a warning to musicians against “formulist and antipopular tendencies,” singling out Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturian, and several others for

writing music that was “anti-democratic and foreign to the Soviet people and its artistic tastes.” The music of Prokofiev’s Sixth Symphony in particular was said to be too obscure in meaning for the average Soviet citizen to comprehend.

Prokofiev left us few comments about this symphony. On one occasion, he offered a few sentences, mostly on its structure. To biographer Israel Nestyev, the composer said that, to some extent, the music tried to capture the feelings of the closing months of World War II — elation over the victory, but also deep realization “that each of us has wounds that cannot be healed. One has lost those dear to him, another has lost his health. These facts cannot be forgotten.”

For the rest of his life (which ended, fatefully, on the same day as Joseph Stalin’s), Prokofiev worked under the shadow of official disapproval, the hardship it caused, and his own failing health. He would produce a Seventh Symphony in 1952, full of nostalgia and melancholy, but lacking the personal conviction that propels both the Fifth and the Sixth.

Melody abounds in the Sixth Symphony, often in the form of long stretches scored with a tune that stands out clearly on violins and flutes in unison, for example, or violas and English horn, or cellos and horn. The colors are expertly blended.

In the first movement, after a few irreverent blasts designed to catch the audience’s attention, the violins and violas state the first of these melodies. When the tempo slows down, a pair of oboes and English horn present the

next new theme. A quicker tempo and a reminiscence of Haydn’s “Clock” Symphony introduce the third melody, now on English horn and violas. The shape of the movement is thus constructed around different tempos and through the interaction of these different themes. Some have likened this to a melancholy landscape, in which we witness a variety of scenes — a funeral march, a furious expression of angst or outrage, moments of happiness, and so forth.

The long slow movement is framed at the beginning and end by a passage of painful dissonance, as if to conceal or protect the richness and warmth of the movement itself. Another distraction from the stream of melody is a passage where a woodblock calls for our attention, just before the timpani join the

double basses and lower winds in a crazy burst of activity. Despite this, the middle movement is truly the soul of the Sixth Symphony, filled with ardor, solace, and conflicted rage.

The third-movement finale, in contrast, is positive and upbeat. It again reminds us of Haydn and also echoes the ballet music of which Prokofiev was such a master. Its lines are often filled with optimism, rarely questioned. But before the symphony can close, there comes a long descent on the bassoon, which ushers in a return of the theme from the first movement assigned to the oboes. Then there is a moment of questioning followed by a swift and noisy coda, leaving us uncertain but contemplating all we have heard.

Macdonald

Macdonald

FRANZ WELSER-MÖST is among today’s most distinguished conductors. The 2023–24 season marks his 22nd year as Music Director of The Cleveland Orchestra. With the future of their acclaimed partnership extended to 2027, he will be the longest-serving musical leader in the ensemble’s history. The New York Times has declared Cleveland under WelserMöst’s direction to be “America’s most brilliant orchestra,” praising its virtuosity, elegance of sound, variety of color, and chamber-like musical cohesion.

With Welser-Möst, The Cleveland Orchestra has been praised for its inventive programming, ongoing support of new music, and innovative work in presenting operas. To date, the Orchestra and Welser-Möst have been showcased around the world in 20 international tours together. In 2020, the ensemble launched its own recording label and new streaming broadcast platform to share its artistry globally.

In addition to his commitment to Cleveland, Welser-Möst enjoys a particularly close and productive relationship with the Vienna Philharmonic as a guest conductor. He has conducted its celebrated New Year’s Concert three times, and regularly leads the orchestra at home in Vienna, as well as on tours.

Welser-Möst is also a regular guest at the Salzburg Festival where he has led

a series of acclaimed opera productions, including Rusalka, Der Rosenkavalier, Fidelio, Die Liebe der Danae, Aribert Reimann’s opera Lear, and Richard Strauss’s Salome. In 2020, he conducted Strauss’s Elektra on the 100th anniversary of its premiere. He has since returned to Salzburg to conduct additional performances of Elektra in 2021 and Giacomo Puccini’s Il trittico in 2022.

In 2019, Welser-Möst was awarded the Gold Medal in the Arts by the Kennedy Center International Committee on the Arts. Other honors include The Cleveland Orchestra’s Distinguished Service Award, two Cleveland Arts Prize citations, the Vienna Philharmonic’s “Ring of Honor,” recognition from the Western Law Center for Disability Rights, honorary membership in the Vienna Singverein, appointment as an Academician of the European Academy of Yuste, and the Kilenyi Medal from the Bruckner Society of America.

Daniil Trifonov has made a spectacular ascent of the classical music world, as a solo artist, champion of the concerto repertoire, chamber and vocal collaborator, and composer. Combining consummate technique with rare sensitivity and depth, his performances are a perpetual source of awe. With Transcendental, the Liszt collection that marked his third title as an exclusive Deutsche Grammophon artist, Trifonov won the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Solo Album of 2018. Named Gramophone’s 2016 Artist of the Year and Musical America’s 2019 Artist of the Year, he was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government in 2021. As The Times of London notes, he is “without question the most astounding pianist of our age.”

Trifonov undertakes major engagements on three continents in the 2023 – 24 season. In concert, he performs with The Cleveland Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Toronto Symphony, Israel Philharmonic, and Orchestre de Paris, among others. In recital, he plays sonatas by Prokofiev and Debussy on a high-profile European tour with cellist Gautier Capuçon and tours a new solo program to musical hotspots including Vienna, Madrid, Venice, and New York. Other recent highlights include headlining the season-opening

gala of Carnegie Hall, season-long artistic residencies with the Rotterdam Philharmonic and Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, and the release of Bach: The Art of Life, which scored Trifonov his sixth Grammy nomination.

During the 2010 –11 season, Trifonov won medals at three of the music world’s most prestigious competitions, taking Third Prize in Warsaw’s Chopin Competition, First Prize in Tel Aviv’s Rubinstein Competition, and both First Prize and Grand Prix in Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Competition.

Born in Nizhny Novgorod in 1991, Trifonov began his musical training at age 5 and went on to attend Moscow’s Gnessin Academy of Music as a student of Tatiana Zelikman, before pursuing his piano studies with Sergei Babayan at the Cleveland Institute of Music. He has also studied composition, and continues to write for piano, chamber ensemble, and orchestra.

2023-24

SERAPHBRASS

Friday,October13

Performingcoreclassics, originaltranscriptions,and newlycommissionedworks.

“SeraphBrassdeliversmusic bothbrightandwarm, consistentlyplayingwith satisfyingtonequalitiesthat makesbrassmusicendearing.”

—KnoxTNToday

JEREMYDENK

Thursday,November30

Solopianorecitalofworksby femalecomposersfromthe19th centurytotoday.

“Denkisamongthemost entertainingofconcertpianists... insightfulinhisinterpretations, entertainingtowatch,and engaginginhisstagebanter.”

—StarTribune

TICKETS: $10.00–$35.00

www.oberlin.edu/ars

Bothconcertswillbeginat7:30pmatFinneyChapelinOberlin.

NOW IN ITS SECOND CENTURY , The Cleveland Orchestra, under the leadership of music director Franz Welser-Möst since 2002, is one of the most sought-after performing ensembles in the world. Year after year, the ensemble exemplifies extraordinary artistic excellence, creative programming, and community engagement. The New York Times has called Cleveland “the best in America” for its virtuosity, elegance of sound, variety of color, and chamber-like musical cohesion.

Founded by Adella Prentiss Hughes, the Orchestra performed its inaugural concert in December 1918. By the middle of the century, decades of growth and sustained support had turned it into one of the most admired globally.

The past decade has seen an increasing number of young people attending concerts, bringing fresh attention to The Cleveland Orchestra’s legendary sound and committed programming. More recently, the Orchestra launched several bold digital projects, including the streaming platform Adella, the podcast On a Personal Note, and its own recording label, a new chapter in the Orchestra’s long and distinguished recording and broadcast history. Together, they have captured the Orchestra’s unique artistry and the musical achievements of the Welser-Möst and Cleveland Orchestra partnership.

The 2023 – 24 season marks Franz Welser-Möst’s 22nd year as music director, a period in which The Cleveland Orchestra earned unprecedented acclaim around the world, including a series of residencies at the Musikverein in Vienna, the first of its kind by an American orchestra, and a number of acclaimed opera presentations.

Since 1918, seven music directors — Nikolai Sokoloff, Artur Rodziński, Erich Leinsdorf, George Szell, Lorin Maazel, Christoph von Dohnányi, and Franz Welser-Möst — have guided and shaped the ensemble’s growth and sound. Through concerts at home and on tour, broadcasts, and a catalog of acclaimed recordings, The Cleveland Orchestra is heard today by a growing group of fans around the world.

KELVIN SMITH FAMILY CHAIR

David Radzynski

CONCERTMASTER

Blossom-Lee Chair

Jung-Min Amy Lee

ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER

Gretchen D. and Ward Smith Chair

Jessica Lee

ASSISTANT CONCERTMASTER

Clara G. and George P. Bickford Chair

Stephen Tavani

ASSISTANT CONCERTMASTER

Dr. Ronald H. Krasney Chair

Wei-Fang Gu

Drs. Paul M. and Renate H. Duchesneau Chair

Kim Gomez

Elizabeth and Leslie

Kondorossy Chair

Chul-In Park

Harriet T. and David L. Simon Chair

Miho Hashizume

Theodore Rautenberg Chair

Jeanne Preucil Rose

Larry J.B. and Barbara S. Robinson Chair

Alicia Koelz

Oswald and Phyllis Lerner

Gilroy Chair

Yu Yuan

Patty and John Collinson

Chair

Isabel Trautwein

Trevor and Jennie Jones Chair

Katherine Bormann

Analisé Denise Kukelhan

Gladys B. Goetz Chair

Zhan Shu

Youngji Kim

Genevieve Smelser

Stephen Rose*

Alfred M. and Clara T. Rankin Chair

Eli Matthews1

Patricia M. Kozerefski and Richard J. Bogomolny Chair

Sonja Braaten Molloy

Carolyn Gadiel Warner

Elayna Duitman

Ioana Missits

Jeffrey Zehngut

Sae Shiragami

Kathleen Collins

Beth Woodside

Emma Shook

Dr. Jeanette Grasselli Brown and Dr. Glenn R. Brown Chair

Yun-Ting Lee

Jiah Chung Chapdelaine

Liyuan Xie

VIOLAS

Wesley Collins*

Chaillé H. and Richard B. Tullis Chair

Lynne Ramsey1

Charles M. and Janet G. Kimball Chair

Stanley Konopka2

Mark Jackobs

Jean Wall Bennett Chair

Lisa Boyko

Richard and Nancy

Sneed Chair

Richard Waugh

Lembi Veskimets

The Morgan Sisters Chair

Eliesha Nelson

Anthony and Diane

Wynshaw-Boris Chair

Joanna Patterson Zakany

William Bender

Gareth Zehngut

Mark Kosower*

Louis D. Beaumont Chair

Richard Weiss1

The GAR Foundation Chair

Charles Bernard2

Helen Weil Ross Chair

Bryan Dumm

Muriel and Noah Butkin

Chair

Tanya Ell

Thomas J. and Judith Fay

Gruber Chair

Ralph Curry

Brian Thornton

William P. Blair III Chair

David Alan Harrell

Martha Baldwin

Dane Johansen

Paul Kushious

BASSES

Maximilian Dimoff*

Clarence T. Reinberger Chair

Derek Zadinsky2

Charles Paul1

Mary E. and F. Joseph Callahan Chair

Mark Atherton

Thomas Sperl

Henry Peyrebrune

Charles Barr Memorial Chair

Charles Carleton

Scott Dixon

HARP

Trina Struble*

Alice Chalifoux Chair

FLUTES

Joshua Smith*

Elizabeth M. and William C. Treuhaft Chair

Saeran St. Christopher

Jessica Sindell2

Austin B. and Ellen W. Chinn Chair

Mary Kay Fink

PICCOLO

Mary Kay Fink

Anne M. and M. Roger Clapp Chair

OBOES

Frank Rosenwein*

Edith S. Taplin Chair

Corbin Stair

Sharon and Yoash Wiener Chair

Jeffrey Rathbun2

Everett D. and Eugenia S. McCurdy Chair

Robert Walters

ENGLISH HORN

Robert Walters

Samuel C. and Bernette K. Jaffe Chair

CLARINETS

Afendi Yusuf*

Robert Marcellus Chair

Robert Woolfrey

Victoire G. and Alfred M. Rankin, Jr. Chair

Daniel McKelway2

Robert R. and Vilma L. Kohn Chair

Amy Zoloto

E-FLAT CLARINET

Daniel McKelway

Stanley L. and Eloise M.

Morgan Chair

BASS CLARINET

Amy Zoloto

Myrna and James Spira Chair

BASSOONS

John Clouser*

Louise Harkness Ingalls Chair

Gareth Thomas

Barrick Stees2

Sandra L. Haslinger Chair

Jonathan Sherwin

CONTRABASSOON

Jonathan Sherwin

HORNS

Nathaniel Silberschlag*

George Szell Memorial Chair

Michael Mayhew§

Knight Foundation Chair

Jesse McCormick

Robert B. Benyo Chair

Hans Clebsch

Richard King

Meghan Guegold Hege

TRUMPETS

Michael Sachs*

Robert and Eunice Podis

Weiskopf Chair

Jack Sutte

Lyle Steelman2

James P. and Dolores D. Storer Chair

Michael Miller

CORNETS

Michael Sachs*

Mary Elizabeth and G. Robert Klein Chair

Michael Miller

TROMBONES

Brian Wendel*

Gilbert W. and Louise I. Humphrey Chair

Richard Stout

Alexander and Marianna C. McAfee Chair

Shachar Israel2

EUPHONIUM & BASS TRUMPET

Richard Stout

TUBA

Yasuhito Sugiyama*

Nathalie C. Spence and Nathalie S. Boswell Chair

TIMPANI vacant

PERCUSSION

Marc Damoulakis*

Margaret Allen Ireland Chair

Thomas Sherwood

Tanner Tanyeri

KEYBOARD INSTRUMENTS

Carolyn Gadiel Warner

Marjory and Marc L. Swartzbaugh Chair

LIBRARIANS

Michael Ferraguto

Joe and Marlene Toot Chair

Donald Miller

ENDOWED CHAIRS CURRENTLY UNOCCUPIED

Elizabeth Ring and William

Gwinn Mather Chair

Virginia M. Linsdseth, PhD, Chair

Paul and Lucille Jones Chair

James and Donna Reid Chair

Sunshine Chair

Otto G. and Corinne T. Voss Chair

Mr. and Mrs. Richard K.

Smucker Chair

Rudolf Serkin Chair

CONDUCTORS

Christoph von Dohnányi

MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE

Daniel Reith

ASSISTANT CONDUCTOR

Sidney and Doris Dworkin Chair

Lisa Wong

DIRECTOR OF CHORUSES

Frances P. and Chester C. Bolton Chair

* Principal

§ Associate Principal

1 First Assistant Principal

2 Assistant Principal

This roster lists full-time members of The Cleveland Orchestra. The number and seating of musicians onstage varies depending on the piece being performed. Seating within the string sections rotates on a periodic basis.

Pre-concert lectures are held in Reinberger Chamber Hall one hour prior to the performance.

SEP 28 & OCT 1

TRIFONOV PLAYS

BRAHMS

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Daniil Trifonov, piano

BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 1

PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 6

Pre-concert talk with Orchestra

President & CEO André Gremillet and Music Director Franz Welser-Möst

OCT 5 – 7

TCHAIKOVSKY’S

SECOND SYMPHONY

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Christoph Sietzen, percussion

MOZART Symphony No. 29

JOHANNES MARIA STAUD

Whereas the reality trembles

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Pre-concert lecture by James Wilding

OCT 12 & 13

MAHLER’S SONG OF THE NIGHT

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Simon Keenlyside, baritone

MAHLER Selected Songs

MAHLER Symphony No. 7

Pre-concert lecture by James O’Leary

OCT 15

SPECIAL EVENT

Renée Fleming & Friends

Renée Fleming, soprano

Emerson String Quartet

Simone Dinnerstein, piano

Merle Dandridge, narrator

PHILIP GLASS Etude No. 6

BEETHOVEN String Quartet No. 14

PREVIN Penelope

OCT 20

SPECIAL EVENT

Eric Whitacre Conducts

The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

Eric Whitacre, conductor

Lisa Wong, conductor

Mingyao Zhao, cello

Daniel Overly, piano

REENA ESMAIL When the Violin

ERIC WHITACRE The Sacred Veil

NOV 9 – 11

HANNIGAN CONDUCTS STRAUSS

Barbara Hannigan, conductor

Aphrodite Patoulidou, soprano

HAYDN Symphony No. 44, “Trauersinfonie”

VIVIER Lonely Child *

LIGETI Lontano *

R. STRAUSS Death and Transfiguration

Pre-concert lecture by Rabbi Roger Klein

NOV 19

RECITAL Schumann & Ravel

Marc-André Hamelin, piano

IVES Piano Sonata No. 2

R. SCHUMANN Forest Scenes

RAVEL Gaspard de la nuit

NOV 24 – 26

TCHAIKOVSKY’S VIOLIN CONCERTO

Pietari Inkinen, conductor

Augustin Hadelich, violin

DVOŘÁK Othello Overture

TCHAIKOVSKY Violin Concerto

DVOŘÁK Symphony No. 8

Pre-concert lecture by James Wilding

NOV 30 – DEC 2

MAHLER’S FOURTH SYMPHONY

Daniel Harding, conductor

Lauren Snouffer, soprano

BETSY JOLAS Ces belles années…

MAHLER Symphony No. 4

Pre-concert lecture by Michael Strasser

DEC 7 & 9

TCHAIKOVSKY’S

ROMEO & JULIET

Semyon Bychkov, conductor

Katia Labèque, piano

Marielle Labèque, piano

JULIAN ANDERSON Symphony No. 2, “Prague Panoramas”

MARTINŮ Concerto for Two Pianos

TCHAIKOVSKY Romeo and Juliet

Fantasy Overture

Pre-concert lecture by Caroline Oltmanns

JAN 11 – 13

THE MIRACULOUS MANDARIN

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

KŘENEK Kleine Symphonie

MAHLER/KŘENEK Adagio from Symphony No. 10

BARTÓK String Quartet No. 3 (arr. for string orchestra)

BARTÓK Suite from The Miraculous Mandarin

Pre-concert lecture by Kevin McBrien

JAN 17 & 18

MODERN CLASSICIST: WELSER-MÖST

CONDUCTS

PROKOFIEV 2 & 5

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 2

WEBERN Symphony

PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 5

Pre-concert lecture by Eric Charnofsky

FEB 1

RECITAL

Beethoven for Three

Leonidas Kavakos, violin

Yo-Yo Ma, cello

Emanuel Ax, piano

BEETHOVEN Piano Trio, Op. 70, No. 1, “Ghost”

BEETHOVEN/WOSNER Symphony No. 1

BEETHOVEN Piano Trio, Op. 70, No. 2

FEB 9 – 11

BEETHOVEN’S

FATEFUL FIFTH

Herbert Blomstedt, conductor

SCHUBERT Symphony No. 6

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 5

Pre-concert lecture by James O’Leary

* Not performed on the Friday matinee concert

FEB 15 & 17

RAVEL’S MOTHER GOOSE

George Benjamin, conductor

Tim Mead, countertenor

Women of The Cleveland Orchestra

Chorus

DIETER AMMANN glut

GEORGE BENJAMIN Dream of the Song

KNUSSEN The Way to Castle Yonder

RAVEL Ma mère l’Oye (complete ballet)

Pre-concert lecture by James Wilding

FEB 22 – 25

BEETHOVEN’S PASTORAL

Philippe Herreweghe, conductor

Jean-Guihen Queyras, cello

BEETHOVEN Overture to Egmont

HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 6, “Pastoral”

Pre-concert lecture by David Rothenberg

FEB 29 – MAR 2

KANNEH-MASON PLAYS

SCHUMANN

Susanna Mälkki, conductor

Isata Kanneh-Mason, piano

J.S. BACH/WEBERN Ricercare from Musical Offering *

C. SCHUMANN Piano Concerto

HINDEMITH Mathis der Maler Symphony

Pre-concert lecture by Eric Charnofsky

MAR 7 – 9

BRAHMS’S FOURTH SYMPHONY

Fabio Luisi, conductor

Mary Kay Fink, piccolo

WEBER Overture to Oberon

ODED ZEHAVI Aurora

BRAHMS Symphony No. 4

Pre-concert lecture by Francesca Brittan

MAR 10

RECITAL Chopin & Schubert

Yefim Bronfman, piano

SCHUBERT Piano Sonata No. 14

R. SCHUMANN Carnival Scenes from Vienna

ESA-PEKKA SALONEN Sisar

CHOPIN Piano Sonata No. 3

MAR 14, 16 & 17

LEVIT PLAYS MOZART

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Igor Levit, piano

MOZART Piano Concerto No. 27

BRUCKNER Symphony No. 4, “Romantic”

Pre-concert lecture by Cicilia Yudha

MAR 21 – 23

SIBELIUS’S SECOND SYMPHONY

Dalia Stasevska, conductor

Josefina Maldonado, mezzo-soprano

RAUTAVAARA Cantus Arcticus

PERRY Stabat Mater

SIBELIUS Symphony No. 2

Pre-concert lecture by Kevin McBrien

APR 4 & 6

CITY NOIR

John Adams, conductor

James McVinnie, organ

Timothy McAllister, saxophone

GABRIELLA SMITH Breathing Forests

DEBUSSY Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun

JOHN ADAMS City Noir

Pre-concert lecture by Eric Charnofsky

APR 11 – 13

ELGAR’S CELLO

CONCERTO

Klaus Mäkelä, conductor

Sol Gabetta, cello

Thomas Hampson, baritone *

The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus *

JIMMY LÓPEZ BELLIDO Perú negro

ELGAR Cello Concerto

WALTON Belshazzar’s Feast *

Pre-concert lecture by James Wilding

APR 14

RECITAL

Schumann & Brahms

Evgeny Kissin, piano

Matthias Goerne, baritone

R. SCHUMANN Dichterliebe

BRAHMS Four Ballades, Op. 10

BRAHMS Selected Songs

For tickets & more information visit:

clevelandorchestra.com

APR 18 – 20

RAVEL & STRAVINSKY

Klaus Mäkelä, conductor

Yuja Wang, piano

RAVEL Concerto for the Left Hand

STRAVINSKY Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments

STRAVINSKY The Rite of Spring

Pre-concert lecture by Caroline Oltmanns

APR 26 – 28

RACHMANINOFF’S

SECOND PIANO

CONCERTO

Lahav Shani, conductor

Beatrice Rana, piano

UNSUK CHIN subito con forza

RACHMANINOFF Piano Concerto No. 2

BARTÓK Concerto for Orchestra

Pre-concert lecture by James O’Leary

MAY 2 – 4

LANG LANG PLAYS

SAINT-SAËNS

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Lang Lang, piano *

SAINT-SAËNS Piano Concerto No. 2 *

BERLIOZ Symphonie fantastique

Pre-concert lecture by Caroline Oltmanns

MAY 16, 18, 24 & 26

MOZART’S MAGIC FLUTE

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Nikolaus Habjan, director

Julian Prégardien, tenor

Ludwig Mittelhammer, baritone

Christina Landshamer, soprano

The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus

MOZART The Magic Flute

Staged production sung in German with projected supertitles

MAY 23 & 25

MOZART’S GRAN

PARTITA

Franz Welser-Möst, conductor

Leila Josefowicz, violin

Trina Struble, harp

WAGNER Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde

JÜRI REINVERE Concerto for Violin and Harp

MOZART Serenade No. 10, “Gran

Partita”

Pre-concert lecture by Michael Strasser

The Cleveland Orchestra is committed to creating a comfortable, enjoyable, and safe environment for all guests at Severance Music Center. While mask and COVID-19 vaccination are recommended they are not required. Protocols are reviewed regularly with the assistance of our Cleveland Clinic partners; for up-to-date information, visit: clevelandorchestra. com/attend/health-safety

As a courtesy to the audience members and musicians in the hall, late-arriving patrons are asked to wait quietly until the first convenient break in the program. These seating breaks are at the discretion of the House Manager in consultation with the performing artists.

As a courtesy to others, please silence all devices prior to the start of the concert.

Audio recording, photography, and videography are prohibited during performances at Severance. Photographs can only be taken when the performance is not in progress.

For the comfort of those around you, please reduce the volume on hearing aids and other devices that may produce a noise that would detract from the program. For Infrared Assistive-Listening Devices, please see the House Manager or Head Usher for more details.

Download

your concert tickets.

For more information and direct links to download, visit clevelandorchestra.com/ticketwallet or scan the code with your smartphone camera to download the app for iPhone or Android.

Available for iOS and Android on Google Play and at the Apple App Store.

Cleveland Orchestra performances are broadcast as part of regular programming on ideastream/WCLV Classical 90.3 FM, Saturdays at 8 PM and Sundays at 4 PM.

Contact an usher or a member of house staff if you require medical assistance. Emergency exits are clearly marked throughout the building. Ushers and house staff will provide instructions in the event of an emergency.

Regardless of age, each person must have a ticket and be able to sit quietly in a seat throughout the performance. Classical Season subscription concerts are not recommended for children under the age of 8. However, there are several age-appropriate series designed specifically for children and youth, including Music Explorers (for 3 to 6 years old) and Family Concerts (for ages 7 and older).

The Cleveland Orchestra is grateful to the following organizations for their ongoing generous support of The Cleveland Orchestra: the State of Ohio and Ohio Arts Council and to the residents of Cuyahoga County through Cuyahoga Arts and Culture.

The Cleveland Orchestra is proud of its long-term partnership with Kent State University, made possible in part through generous funding from the State of Ohio. The Cleveland Orchestra is proud to have its home, Severance Music Center, located on the campus of Case Western Reserve University, with whom it has a long history of collaboration and partnership.

© 2023 The Cleveland Orchestra and the Musical Arts Association

Program books for Cleveland Orchestra concerts are produced by The Cleveland Orchestra and are distributed free to attending audience members.

EDITORIAL

Amanda Angel, Program Editor, Managing Editor of Content

aangel@clevelandorchestra.com

Kevin McBrien, Editorial Assistant

DESIGN

Elizabeth Eddins, eddinsdesign.com

ADVERTISING

Live Publishing Company, 216-721-1800

Pauline has always been passionate about educating and giving people the tools needed to succeed. As a professor, analyst, Certified Financial Planner and recent Crain’s Eight Over 80 honoree, she has impacted many and continues to inspire and inform as a volunteer and philanthropist.

At Judson, independent living is all about enjoying the comforts of home in a vibrant, maintenance-free retirement community. Residents take advantage of diverse, enriching programs that cultivate new friendships, maintain wellness, fuel creativity and ignite new interests. Seniors define an inspirational way of living with peace of mind that comes with access to staff members 24 hours a day should help be needed. Visit us to see how we bring independent living to life.

We believe that all Cleveland youth should have access to high-quality arts education. Through the generosity of our donors, we have invested more than $12.6 million since 2016 to scale up neighborhood-based programs that serve thousands of youth year-round in music, dance, theater, photography, literary arts and curatorial mastery. That’s setting the stage for success. Find your passion, and partner with the Cleveland Foundation to make your greatest charitable impact.

(877) 554-5054

www.ClevelandFoundation.org/Success

Tri-C Creative Arts Dance Academy

Tri-C Creative Arts Dance Academy