limits

Lucas Anghinoni FAUUSP Miguel Angel Carrasco FAUUFRJThe relation between the ancient and the contemporary city (the new) is clearly expressed by strong and well-defined boundaries. The issue about limits can be identified in different scales and contexts, either between archaeological areas and the urban fabric or between a monument and its surrounding space. No matter the structure or the context, the limits are there and they represent traces of conflicts that cannot be ignored. However, the assumption of the presence of limits does not simply indicate the acknowledgement of a conflict, but recognises the space as an ambivalent continuity, a whole. Understanding their importance and meaning washes away the idea that considers the dissolution of the boundaries a sine qua non to the integration of space. The design methodologies used to enhance the heritage and establish new urban events should not aspire to abolish the existence of the limits. Instead, it should stress them in order to redefine relations that can take place in the contemporary city. These considerations are taken into account to present a case study in the city of Rome with the attempt to illustrate the discussion and reimagine the relation between the contemporary city and its objects and events. Such factors are identified as components of the landscape, an element guided not as a reconstructor of the past, but as an amalgam of the latter with the present.

sic deinde, quicumque alius transiliet moenia mea “So perish whoever else shall leap over my walls!”

Romulus sentence, after slewing his brother Remus for jumping over the walls of his encampment in mockery.

Livy - Book I, sec.7

Cancelling limits is cancelling architecture altogether, for these limits are the strategic areas of architecture.

Bernard Tschumi - Architecture and Limits I1

In the area of architecture and urban planning, the issue of limits has been deeply explored throughout different periods of time. Recently in our era, between 1980 and 1981, Bernard Tschumi published a series of articles titled Architecture and Limits. Regarding his work, Nesbitt stressed that, “as Tschumi explains, ‘limits are the strategic areas of architecture,’ the base from which one can launch a critique of existing conditions”1. In fact, for Tschumi “the concept of limits is directly related to the very definition of architecture. What is meant by ‘to define?’ - ‘to determine the boundary or limits of,’ as well as ‘to set forth the essential nature of’”2

For the definition of architecture, it is worth turning back to classical antiquity in Greece, where the word ἀρχιτέκτων (architéktōn) meant the main builder, (ἀρχι - archi: to be the first, the commander; and τέκτων - tecton: mason). Later on, the term ἀρχή (arché), which pre-socratics used to refer to an element that would be present in everything and all moments of existence, was commonly translated to medieval Latin with the use of princepwords, with princeps meaning first man, chief leader; and principium meaning origin. From this perspective, architecture could be entirely related to the establishment of principles, the essence mentioned by Tschumi.

If truth be told, limits are one of the core facts that have always determined the architectural conception itself since immemorial times. It is not a coincidence that, by founding a whole city almost 28 centuries ago, Romulus circumscribed the projected area of his future city in a pomerium3 - a ploughed furrow surrounding the Palatine Hill. Later, this same “line” from the rite of Rome’s foundation was used by Romans to define the boundaries of their own land properties. On this line, they placed large stones referred to as Termini. Coulanges, for instance, mentions the fact that “the Terminus guarded the limit of the field, and watched over it”, and “according to the old Roman law, the man and the oxen who touched a Terminus were devoted - that is to say, both man and oxen were immolated in expiation”4, sentenced to death. The tension of this apparently drastic attitude may call attention to a conflict, but in fact, what is imperative here is to perceive the enormous degree of importance the Romans gave to limits, to the point that these limits were considered a deity.

Figure 1 - Design for a Stained Glass Window with Terminus, by Hans Holbein the Younger. Designed for the scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam.

3

In Kate Nesbitt, Theorizing a new agenda for architecture: An anthology of architectural theory, 1965-1995, New York: Princeton Architecture Press, 1996, p. 150.

2

In Kate Nesbitt, op. cit., p. 153.

From Latin, literally post (behind) + moerus (wall).

4 Fustel de Coulanges, The Ancient City, Kitchener: Batoche Books, 2001, p. 54.

The use of sacred limits - not simply considered a physical line - also seems to have been universal amongst the whole Indo-European race. It not only existed among the Hindus5 but, worth mentioning, all over Greece, where they were called ὅροι (horoi). Rykwert, when establishing an Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World, mentions that “one of the early surviving boundary marks, found fairly recently on the Athenian agora, did not proclaim: ‘This is the boundary of the agora’ but ‘I am the boundary of the agora, ὅρος εἰμι τῆς ἀγορᾶς“ - horos eimi tēs agorās)’”6. This stone can still be seen in its original position, with its inscriptions clearly visible.

Moreover, the limits were not only the definition of an end, but they were at the same time a recognition that something existed beyond that line. This becomes clear by recognising the relationship between the Terminus and the Mundus rites. Romans inherited the Mundus from the Etruscans. This was the name of the circular ditch intended to receive offerings to underground divinities and located according to the rite of cities foundation7. Being a perpendicular axis to the horizon, this ditch balanced the cardo and the decumanus, the horizontal and orthogonal axes of the roman city and the world, constituting an image of the sky and centring the city in the whole universe.

In fact, Romans did not consider the roman urbe a polis, a city-state, but the universe itself. In this sense, at a certain time during the Roman empire, no matter whether one was born in Londinium (London), Barcino (Barcelona) or Olisipo, the city of Ulysses (Lisbon), this person could first and foremost hold the civita, that is to say, be a citizen of Rome8 Therefore, the civitas romana and the civitas mundi cannot be more than a tautology.

Not by chance, the term Urbi et Orbi, now denoting a catholic blessing given by the Pope to Rome and to the World, evolved from this consciousness of the Roman empire. And even though Greek was still a language of cultivation in the empire, the genitive Urbis et Orbis lingua also stresses how Romans considered Latin a language of Rome and of the world, hence, a universal language.

Figures 2 and 3 - The stone that marked the limits of the athenian Agora.

5 Fustel de Coulanges, op. cit., p. 53.

6 Joseph Rykwert, The Idea of a Town: The anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World, London: Faber and Faber, 1976.

7 In Rome, the mundus was dug during the foundation of Rome by Romulus near the Comitium, and would correspond to the site occupied by the Umbilicus Urbis Romae and the Lapis Niger, known as “Tomb of Romulus”.

8 Roman citizenship was acquired by birth if both parents were Roman citizens (cives). After a sequence of expansions on citizenship granting, in 212 AD the Edict of Caracalla granted citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire.

Between these periods it is also worth noting examples of how the architectural drawing itself already expresses a will to trespass the limits between imagination and reality. The carceri of Giovanni Battista Piranesi are clear examples of how this imagination may astoundingly come to light. Representing the classical remains and the contemporary architecture of his time, the engravings circulated Europe as souvenirs from the famous routes of the Grand Tour of the 18th century, spreading glorified representations of the landscape of ancient Rome.

Physically speaking “landscapes do not have edges, they are seamless webs which extend out in all directions, constrained only by the conceptual horizons of the people for whom such spaces mean something”9. But it is precisely the meaning applied by its inhabitants to these horizons that turn the landscape into a cultural element - as it is so much discussed in the fields of geography, architecture and urban planning - and for the same reason, characterized (holder a specific characteristic) and, thus, also delimitating. Not as something restrictive, but as a mediator of limits that make up the dynamics of space.

What Darvill says is that the modern landscape that we see represents reality, while the ancient landscape is the same as the myths. However, it is known that myths, despite being distant and not necessarily accessible (a myth may have several parallel narratives), represented an effort to explain reality. Rykwert10 states more specifically that myth and ritual configure - or even originate - the human environment. It is the recognition of the modern landscape as an aggregator of spatial temporalities, just as one can understand the myth as the foundations of our identity (as mentioned, there are reasons for the narrative of the foundation of Rome to delimitate the city into a pomerium). Inserted in the contemporaneity, the archaeological monuments are a fundamental dimension of the modern landscape and influence the way landscape is perceived and experienced in the present, since they carry in the course of time, just like the myths, pieces of intelligible information of a past accessible only through these testimonies.

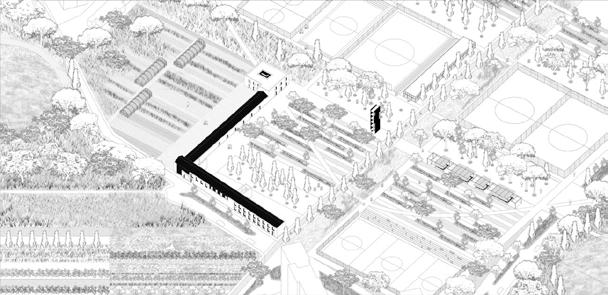

Taking this all into consideration, this article presents a design project developed during the ALA Master Workshop 2021 at La Sapienza University as a study case to better illustrate the discussion about limits and their potentialities in the field of architecture and urban planning: The GRAB Tour - An Essay About Limits11 is an urban proposal for the area of Casilino, located in the seventh quartiere of the city of Rome, Prenestino-Labicano (Q.VII).

Belonging to the suburban area of the city, Casilino is a neighbourhood with great potential for the enhancement of public activities linked to cultural heritage. This urbanized region now occupies part of an area formerly known as the Roman Campagna, a major subject of landscape representations from the 18th century inserted in the context of the Grand Tour, since it had important archaeological monuments from ancient Rome. The work was developed in the context of a two-week workshop, with the aim of synthesizing

⁹ Timothy Darwill, Landscapes: myth or reality?, in: Landscapes: Perception, Recognition and Management. Reconciling the Impossible?, 1997.

10 1975, p. LX)

10Anghinoni, L. G., Carrasco, M. A. P., Kostantiou, A., Serjani, E. The GRAB Tour: An Essay About Limits, Rome, 2021.

Figure 6 - proposed masterplan for the area of Casilino

issues related to the conflict between the development of the contemporary city and the enhancement of urban landscapes that carry a complex system of occupation and hold a peripherical built heritage not related to consolidated touristic areas. The central theme of the ALA Master Workshop 2021 was the connection of the archaeological heritage with the contemporary city through a system of interconnected green spaces known as GRAB (the Grande Raccordo Anulare delle Bici - or Great Cycling Ring), a proposal that integrates urban space through a bicycle mobility system. Via the combination of these two ideals, surges the ArcheoGRAB.

In the area, one can recognise the presence of strong limits between the built urban fabric, in this case mostly represented by a private environment, and a series of green voids, mostly inhabited, with great potential for public uses. The greenery spaces share common features and create an archipelago of territories that still stands against the pressures of modern urban expansion in Rome - a process that began in the post-Risorgimento and the subsequent selection of the city as the capital of unified Italy at the end of the 19th century. This growth phenomenon in Italian urbanization reaches its highest level a century later, and only in 1981 Rome starts to experience a population decrease. This is a radical break from the previous situation: from a small town with a strong rural character Rome becomes a city that expands towards the Roman Campagna, giving rise to a peculiar urban occupation such as the one of the Casilino area (figure x).

This is the image presented by the ArchaeoGRAB: A landscape once essentially rural, surrounded by physical witnesses of Ancient Rome, now with its remains surrounded by the modern city, with scattered uninhabited spaces. Upon this, a new landscape organization is configured, which refers to aqueducts and mausoleums of Ancient Rome, medieval towers, also presents the landscape paradigm of Rome for the future.

The potential of the area to become an archaeological park must be enhanced through the recognition of these voids as potential political spaces (of public nature) embedded in the sea of private nature urbanity. It is in the imminent conflict, inherent to the existence of the limit, that the city is able to reconnect itself with the history that shaped it. Not by chance, Burke (2003), while talking about territorial borders, does not present them as a place of disconnection, but of cultural encounter12. The relationship between such spaces must be one of interconnected opposition, in which boundaries naturally play their role,

and so that voids are no longer empty in the urban sense of the term - uninhabited spaces - but only in the physical sense - open spaces. The limit may sometimes be a space between spaces: the borders they delimit, instead of being dissolved, are tensioned and redefined.

Thus, the territorial organization proposed by the project presents new green corridors and new circulation axes that take into account the mesh of the surrounding urban fabric (figure 5) and the pre-existing moderate pattern of urban agriculture. The strips of land aim to increase the permeability of the area and facilitate the integration of the historical and natural landscape (figure 6).

The highlight of clear preexisting axes recalls the Roman form of land organization called centuriation (figure 8). The agricultural character of the area, once part of the Campagna Romana, is taken into consideration with the aim of enhancing the historical agricultural landscape inserted in contemporaneity and integrating urban functions, such as sports facilities, multifunctional spaces such as open-air cinema projections and temporary markets, and community centres to support the production and commercialization of local products (figure 10).

The limits also play an important role in a smaller-scale of intervention. In order to bring to light the full dimension of the buried Villa dei Gordiani and correlate it with its existing remains that are above the ground, a landscape intervention aims to remodel the area that covers the remains. The creation of sloping cliffs on the edges of the villa’s plan is the tool used to highlight the limits of the private space of the villa and, at the same time, enrich the spontaneous public use within a delimited space. This tool operates through contrast, as it inserts the artificial forms of the villa’s orthogonality into the curvilinear design of the current park. The soil is placed in the form of a slope towards the interior of the plan, contained by a light metal structure that supports it and forms a plateau paved with gravel. (figure 9)

This topographic operation enhances the memory of the ancient limits highlighting the presence of the villa and the still-standing octagonal tower. In this case, the ancient limits are stressed - they are not completely and literally rebuilt, but their presence can be experienced and understood. The ruins become a stage for new urban events (figure 9). As stressed by Tschumi, the problem is not the space itself, but its programmatic organisation in the sense of function and not of event.

The recognition of the differences is a fundamental step in order to develop a project capable of joining the urban functions and archaeological needs. At the Basilica, a new access is proposed to create an opportunity of getting to know and appreciate the complex.

Figure 9 - interventions at Villa dei Gordiani

Figure 10 - the contra-axis

Figure 11 - interventions at the Mausoleum of Sant’Elena

A wooden platform is placed in the central nave of the Basilica, which guides the visitors’ view towards the Mausoleum, perceived as a focal point. In the ancient urban space, there were some specific limits defined by the buildings, façades, and entries. Once again, the ancient limits of the space are highlighted. The platform is located on the axis of the space, forcing the visitor to enter the space through the original entry of the building (figures 8 and 12)13. The entrance is not random, there is no confusion between the aimed urban integration and full permeability. One is not necessarily linked to the other.

The design proposal creates a new circulation axis in the central area of the masterplan, perpendicular to the north-south axis of the GRAB, connecting the metro C stations Malatesta and Gardenie. The presence of the new metro line C highlights the lack of connectivity between the neighbourhoods surrounding the area, both towards east (Pingeto) and west (Prenestino-Centocelle). The stations Malatesta, Teano and Gardenie indicate centralities for the new circulation axis, referred to as the counter-axis. To the south of Teano station, a central square adds different uses and events, becoming a polarity for the neighbourhoods that border the area (figure 12).

In addition, the central area of the masterplan has a diverse agricultural character: the absence of examples of ancient Rome gives way to the strong presence of the Casali, remains of rural residences from the 19th century. The presence of such constructionsconnected to a rural production not far from the present day - reveals the resistance of a rural context within the consolidated city. They are testimonies of a use of land that still survives nowadays, given the presence of small urban agricultural areas, and glimpses of the Roman Campagna within the urban fabric.

However, most of these buildings are in a poor state of conservation. New functions are given to buildings such as Villa del Drago and the Villa Sudrié Complex, capable of hosting community activities for commercialization and promotion of local production (figures 10 and 12).

Figure 12 - Reuse of Villa del Drago for community activities

The fences surrounding the monuments (a purely protective action) are another important issue while dealing with the relationship between the ancient and the contemporary as a whole. They are used as a response to an imminent conflict between the preservation of the monument and the development of the contemporary city, where different groups and activities politically coexist. In the proposed project, the physical limit

13 Anghinoni, L. G., Carrasco, M. A. P., Kostantiou, A., Serjani, E. The GRAB Tour: An Essay About Limits, Rome, 2021.

Figure 13 - exploded isometric of Villa dei Gordiani

Figure 14 - exploded isometric of the basilica at Villa dei Gordiani

Figure 15 - exploded isometric of the intervention at the Catacombs of SS Marcellino and Pietro

imposed by the fences in the Mausoleum of Sant’Elena is replaced by an intermediate space for leisure and contemplation. Taking advantage of the topography of the area, the project proposes a natural grandstand that increases the visual and spatial connection between the park and the monument (figure 11).

Finally, the area of the Catacombs of SS. Marcellino and Pietro is reimagined with the proposition of new exits and entrances to the underground complex. Nowadays, the catacombs have only one entrance near the Mausoleum of Sant’Elena, but previously pilgrims used to get into the narrow corridors (ambulacra) through different passages. The proposed space on the opposite side of the contemporary entrance is an open-air museum settled in a carved space on the ground (figure 13). The access to the bottom level is made by a narrowing ramp that resembles the corridors of the catacombs, which either straitens in thin passageways with loculi14 or enlarges into a whole cryptae15, like the venerated burial place of Marcellinus and Pietro. The modern limits imposed by the present-time entrance - in contrast with the previous permeability of the underground space - is rearranged by this intervention, making the visitor aware of the real dimensions of the catacomb.

These operations illustrate a design experience focused on the relationship between the development of the contemporary city and the preservation of the historic landscape, aiming to integrate them into urban life. It must be understood more as possible scenarios for the city of Rome than as an absolute solution to a specific issue. The meaning applied by those who inhabit the landscape is what makes it something characterized, cultural, more than a mere physical element. In the present, the landscape delimits and also aggregates different historical strata, and the architectural design has the capacity to act upon these characteristics in the space.

In this sense, a physical witness of the past that is only surrounded by a protective fence (unresolved limits as a failed attempt to highlight the presence of the ruin in space) can only be an element with no identity. It becomes a remain dissociated from its history and uncharacterized, which belongs to nothing more than the present itself.

Therefore, the intention of these illustrations is to affirm that the old and the new must coexist in an integrated space, but this objective does not represent the erasure of the differences between the past and the present. Instead, the recognition of the importance of the limits is taken as an opportunity for a design proposal, building a stage where new urban relationships are possible. In addition to existing, they must coexist.

14 Horizontal burrial niches dug on the catacomb walls. A group of loculi deditacted to only one family is normally found inside a cubicula.

15 Catacomb chapels decorated with frescoes.