Magazine spring 2024

LUM Art

n°07

Lum is a contemporary art magazine for California’s Central Coast

Editor-in-Chief

Debra Herrick, PhD

Art Director

Arturo Heredia Soto Writers

Ricky Barajas

Kit Boise-Cossart

Sarah Cunningham

Dalia Garcia

James Glisson

Madeleine Eve Ignon

Jane Handel

Julian Harake

Alex Lukas

Narsiso Martinez

Teddy Nava

Silvia Perea

Tom Pazderka

Sandy Rodriguez

Sarah Rosalena

Copy Editor

Spence Publishers

Heredia Soto

Herrick

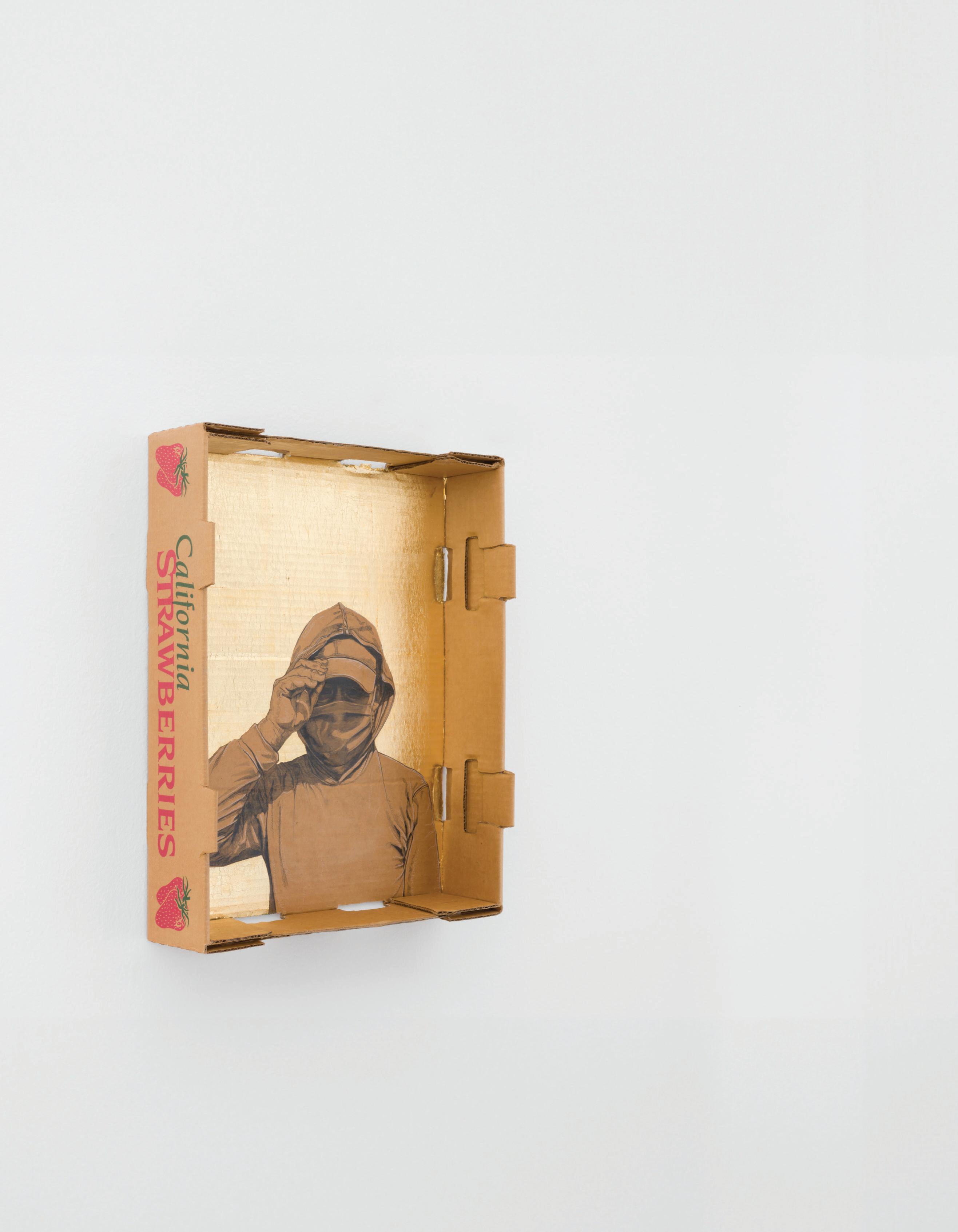

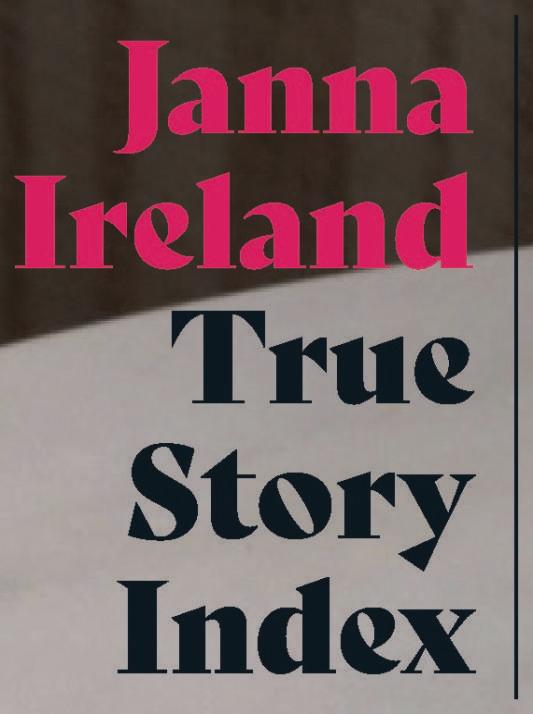

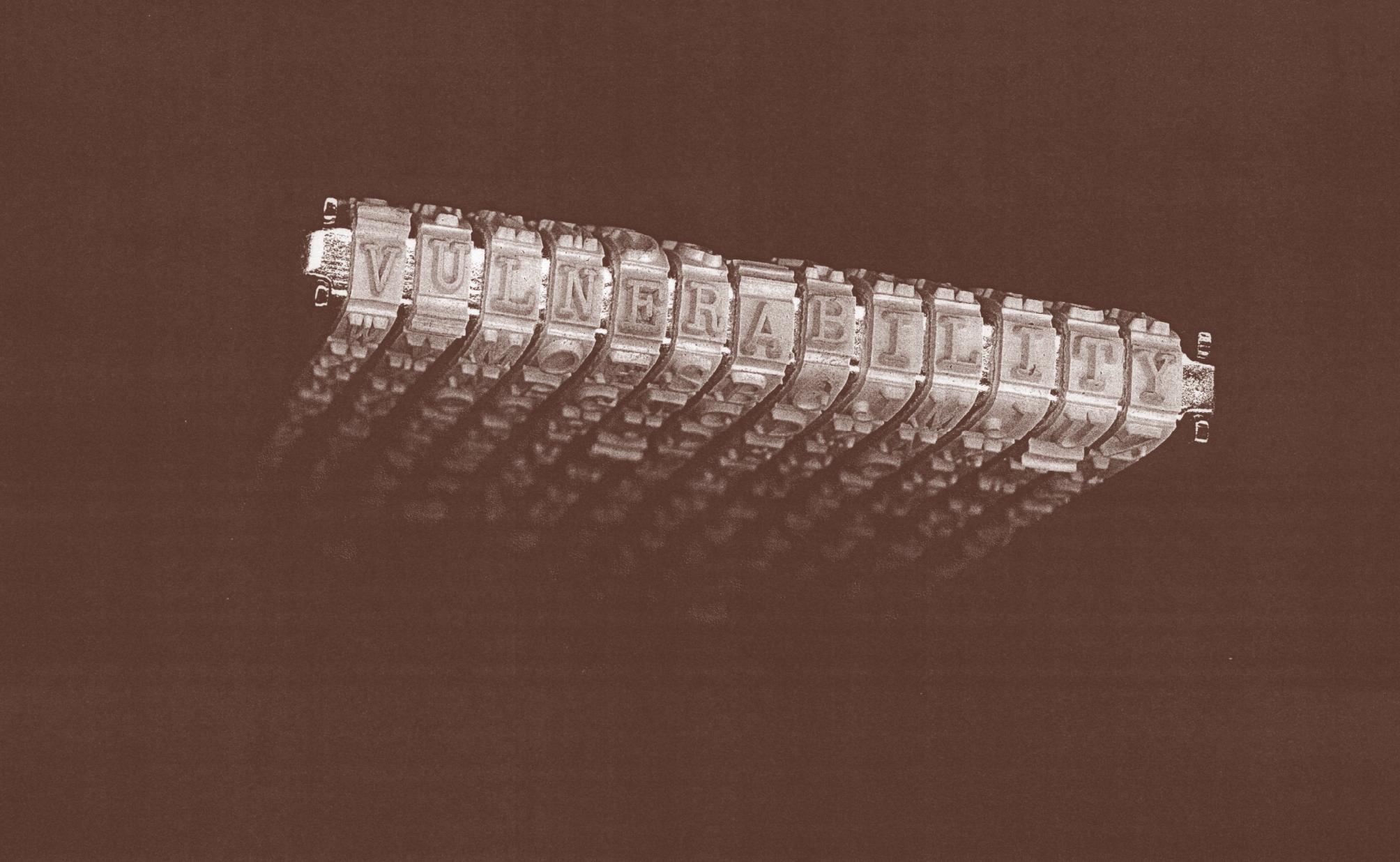

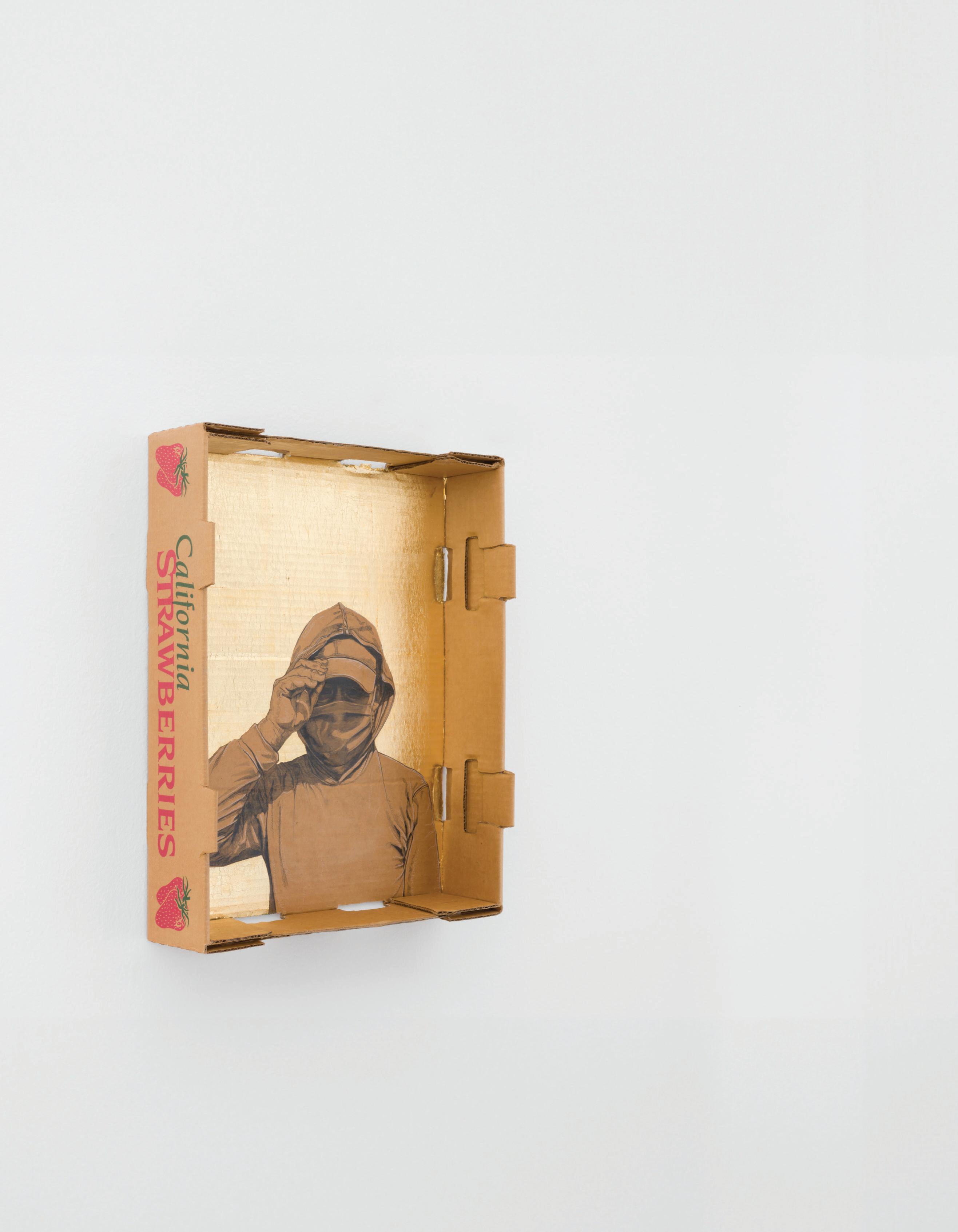

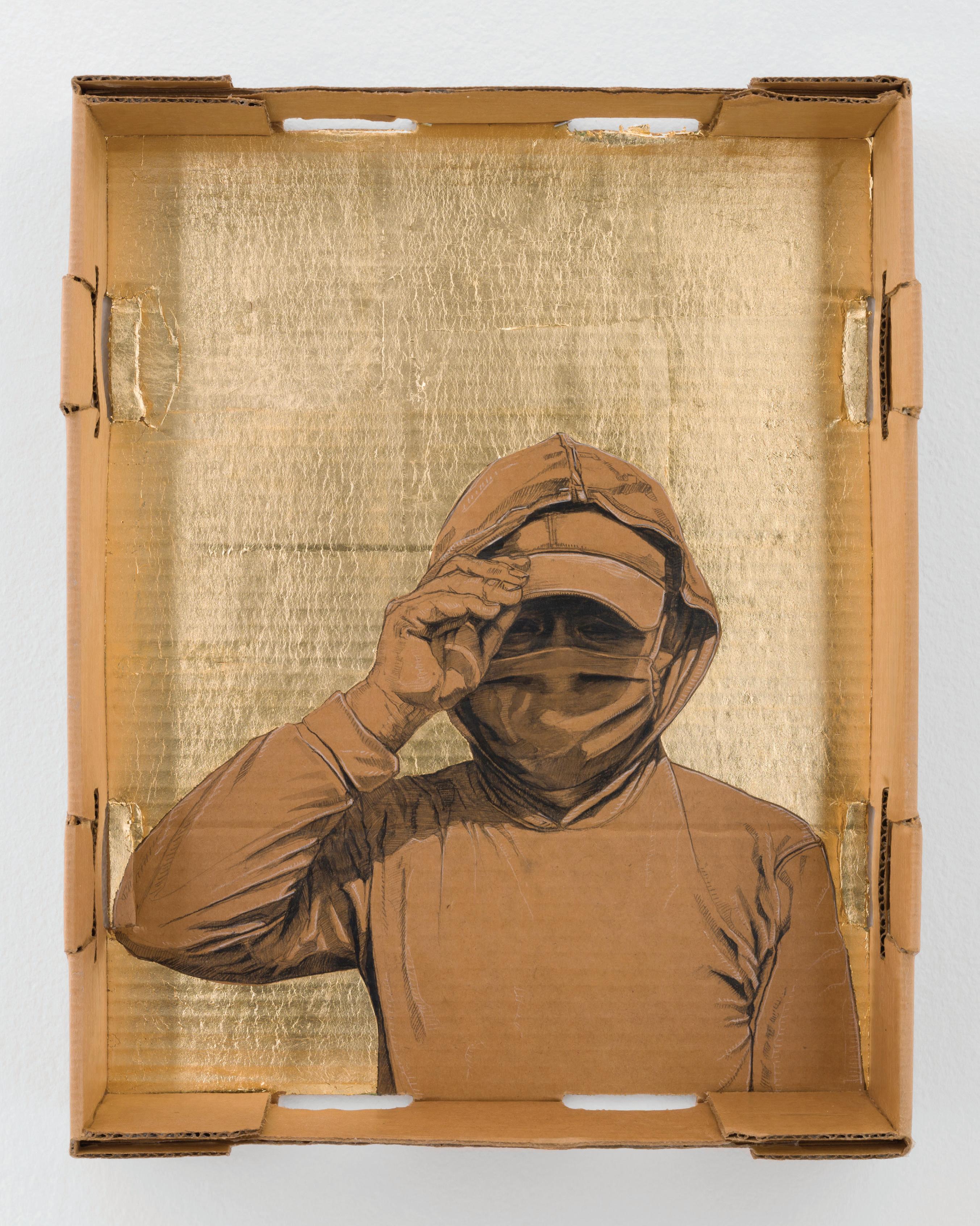

the Cover Narsiso Martinez, Fruit Catcher, ink, charcoal and gold leaf on produce cardboard box, courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles, photo by Yubo Dong Published by California Culture Press, Santa Barbara, printed in California, 2024 All content in this publication is the property of the publishers and may not be reused in any way without written permission from Lum Art Magazine Follow @lumartmag lumartzine.com LUM ART MAGAZINE n° 07 Funding support was provided by the City of Santa Barbara’s Community Arts Grant Program Arts & Culture Benefactor Norton Herrick Join the Friends! Visit lumartzine.com Advertising editor@lumartzine.com Tax-deductible donations Lum Art Magazine is fiscally sponsored by the nonprofit Santa Barbara Arts Collaborative. To make a tax-deductible donation, contact editor@lumartzine.com Give If you are in a position to support the vitality of your arts and writing community,

to

California Culture Press LUM

M8M

Evelyn

Arturo

Debra

On

please consider giving

Lum. Contributions can be made at lumartzine.com/shop or via Venmo: @lum-art-mag

Art Magazine spring 2024

Contents

06. Imagemakers of the Americas

Sandy Rodriguez & Sarah Rosalena in conversation

edited by Debra Herrick

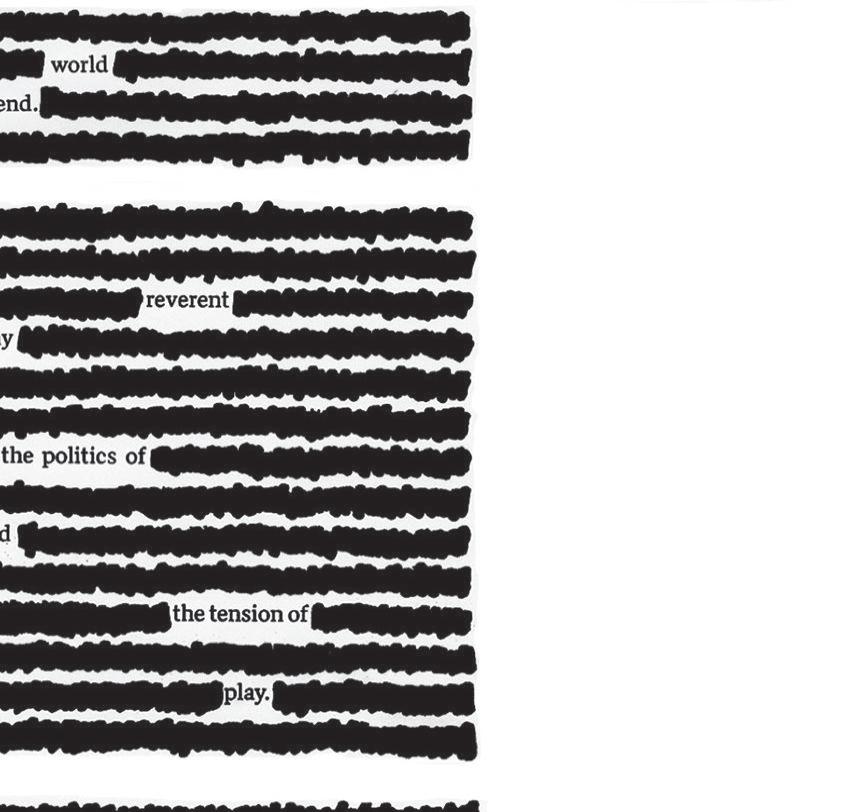

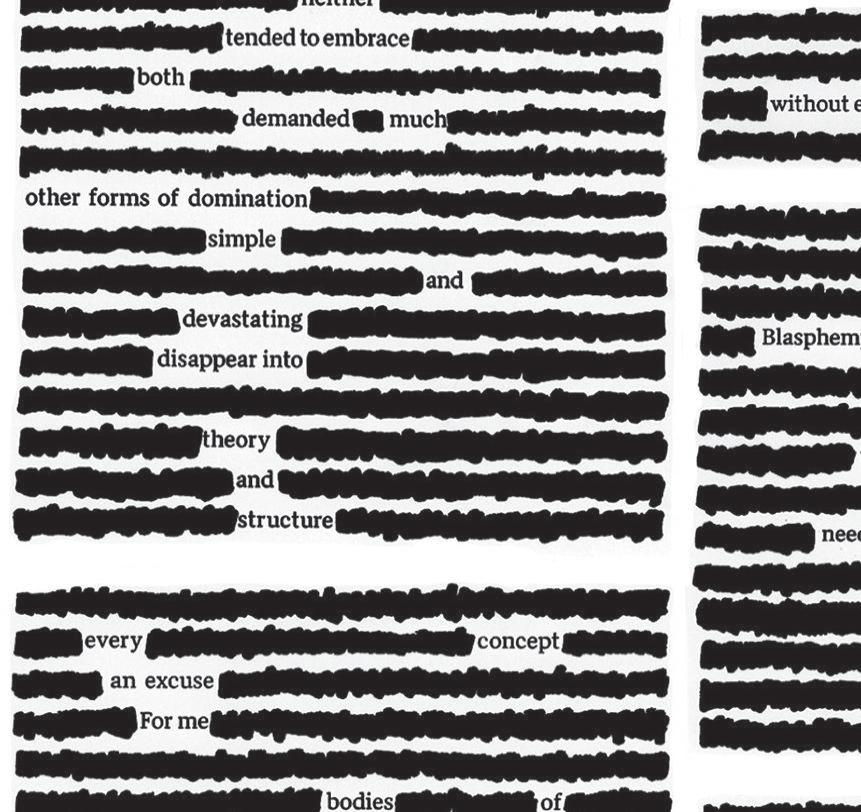

11. Beta Epochs intervention by Madeleine

Eve Ignon & Alex Lukas

15. Revolutionary nostalgia by Tom Pazderka

16. Dead Ambassadors

Kevin Clancy by Julian Harake

18. Fieldwork

Dalia Garcia & Narsiso Martinez in conversation

edited by Debra Herrick

23. Made by Hand/ Born Digital by James Glisson

26. Terremoto

Christina McPhee by Silvia Perea

29. Where does copper come from

Mayela Rodriguez by Ricky Barajas

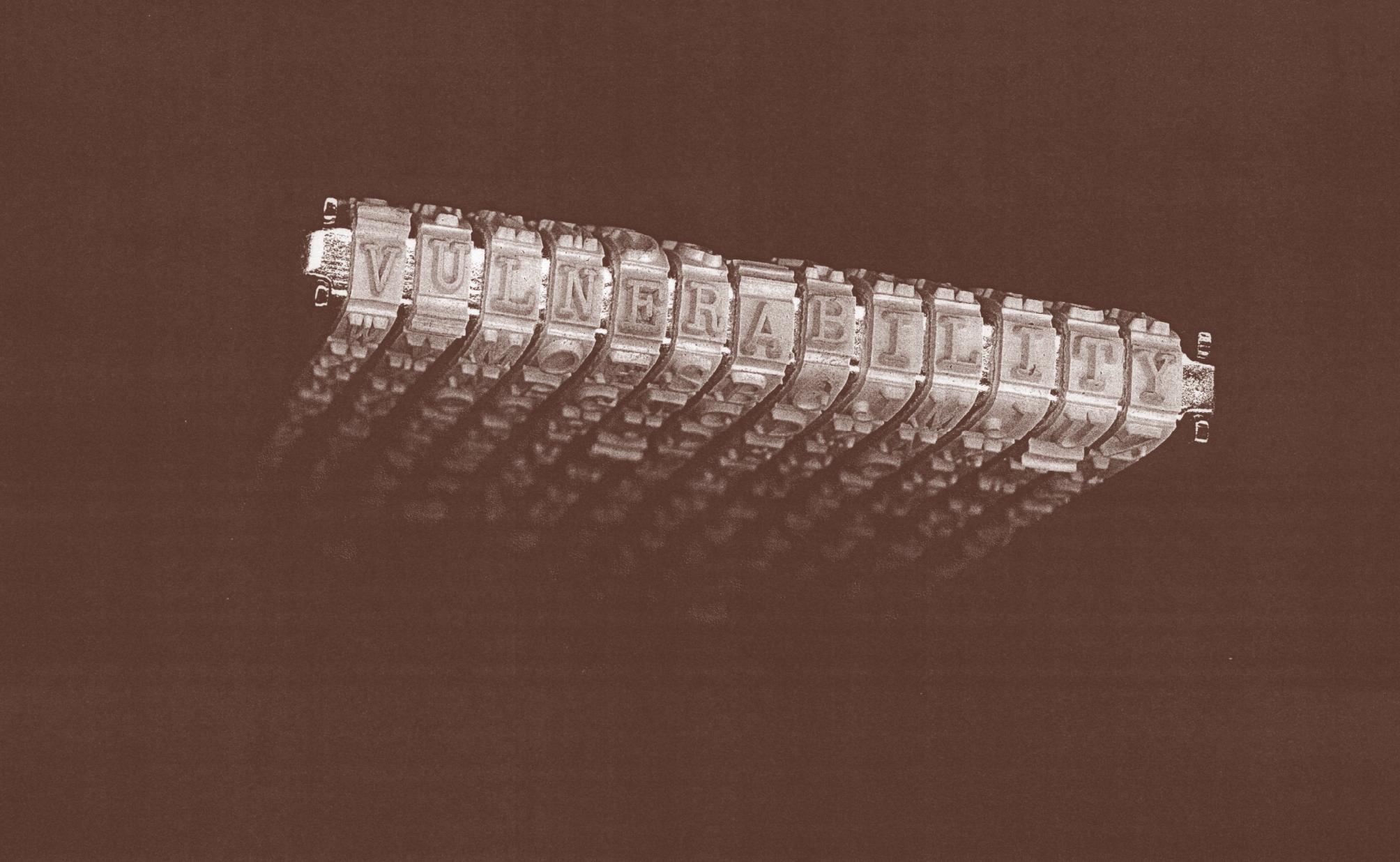

30. Glitches & glitter

Evelyn Contreras by Sarah Cunningham

32. Love me, love me not

Anna May Wong by Debra Herrick

35. Art is a puzzle

Ken Bortolazzo by Kit Boise-Cossart

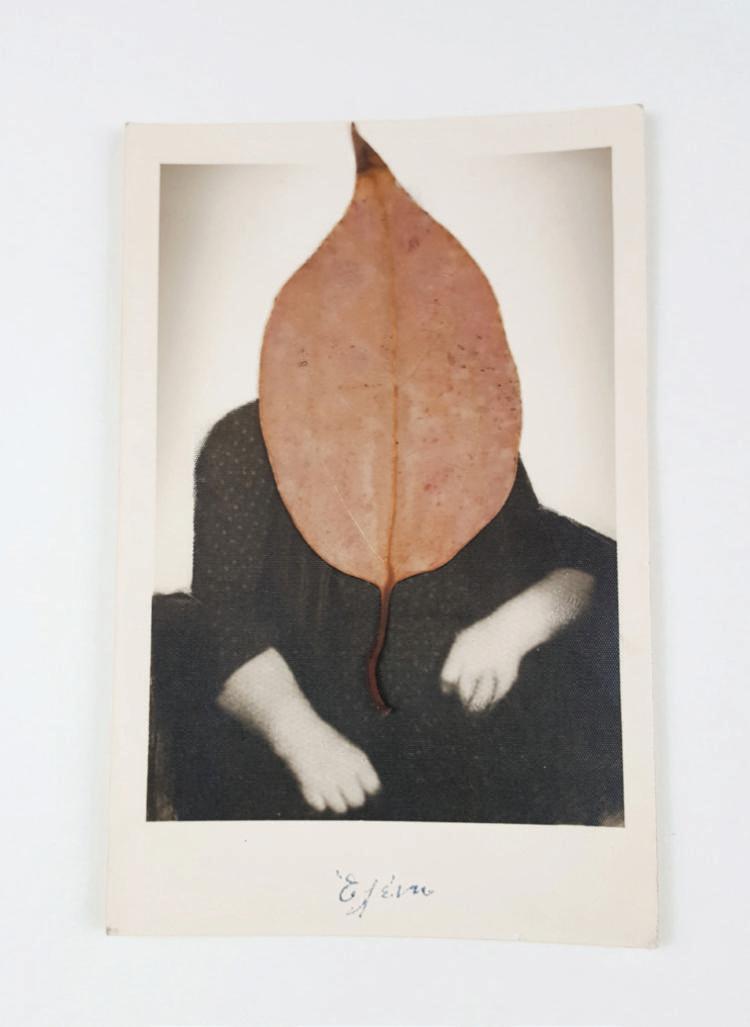

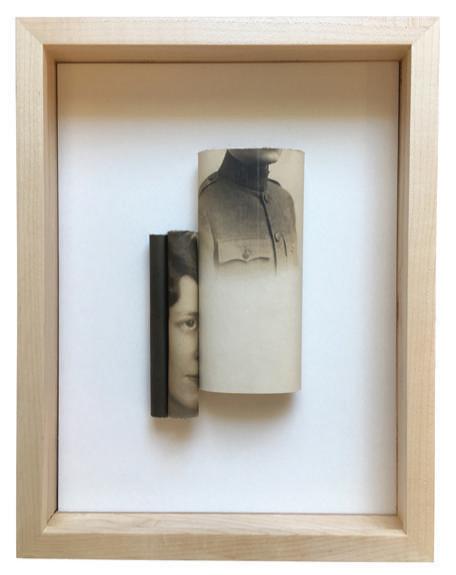

38. Lost, found & reimagined by Jane Handel

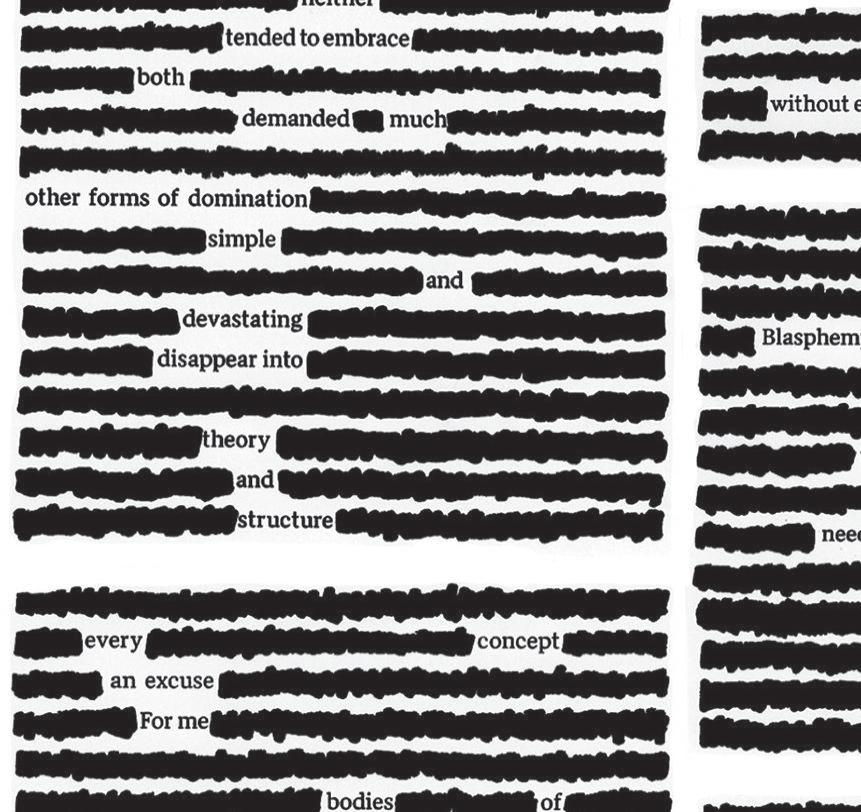

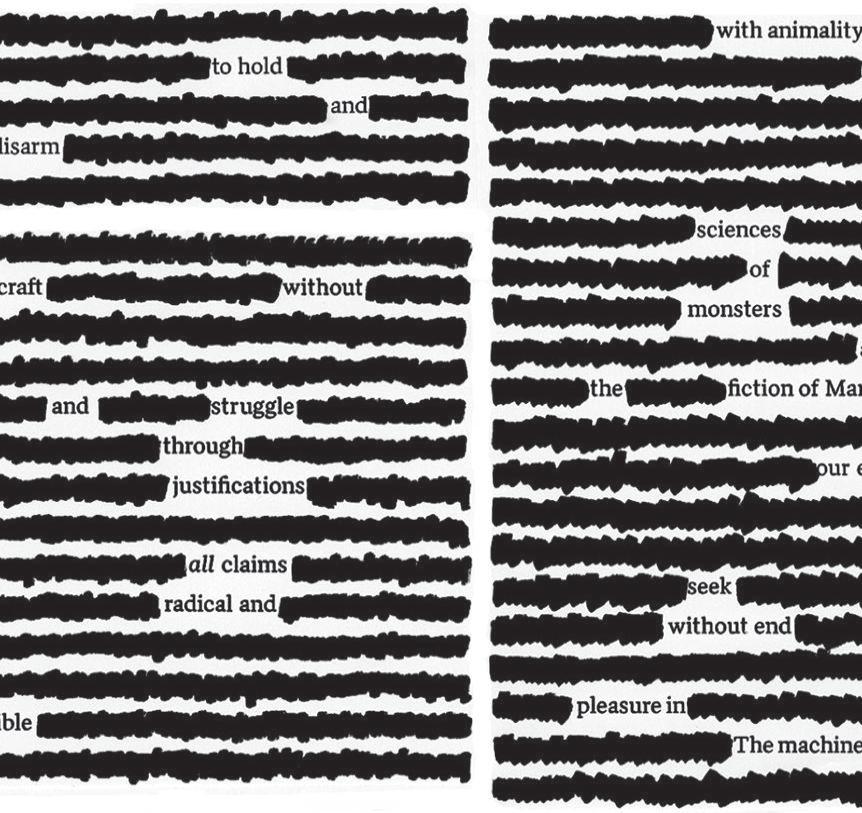

42. Every movement of my lips is an intentional aesthetic and political act intervention by Teddy Nava

SPRING 2024 3

Contributors

Ricky Barajas is a writer and graphic designer. He graduated from University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) with a degree in English and a specialization in creative writing. He was editor-in-chief of the literary arts magazine, The Catalyst, and is currently the media center specialist for UCSB’s Associated Students.

Kit Boise-Cossart graduated from UCSB’s College of Creative Studies with a degree in art. He is now an artist and a builder of green residential projects.

Sarah Cunningham is the founding director of the Pace University Art Gallery and an associate clinical professor in Pace’s Art Department. Her previous posts include director, Atkinson Gallery, Santa Barbara City College (SBCC); director, College of New Jersey Art Gallery; curator, Alice Austen House Museum; and executive director, Albany Center Galleries.

Dalia Garcia is a Mixteca Indigenous sociologist, artist, curator, community organizer and program director at the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara. She is also the co-curator of the upcoming exhibition científcas indígenas/ Indigenous Scientists for the Getty Foundation’s Pacifc Standard Time.

James Glisson is curator of contemporary art at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. His fve books, some co-authored and co-edited, have been recognized by the American Library Association, American Alliance of Museums and Choice Magazine, which gave him an Outstanding Academic Title award. Prior to Santa Barbara, he was Interim Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator and Mishler Associate Curator at The Huntington Library, where he contributed to the establishment of a regular program for contemporary art.

Jane Handel is a writer, artist and publisher of SpiderWoman Press. She is also an editor and art dealer specializing in vintage works on paper. Her essays and short stories have appeared in numerous publications and anthologies. Her 2023 collage art exhibition at Von Lintel Gallery, Santa Monica, Jane Handel: Neither Here Nor There, was called a “Must See” by Artforum’s Art Guide.

Julian Harake is an artist, registered architect, writer, educator and founder of Studio Harake, an art & design practice bridging architecture, printmaking, ceramics & digital fabrication. His creative contributions have exhibited internationally and his essays and criticism have appeared in Dispatches Magazine, The New York Review of Architecture, Pidgin, See/Saw & several published books. He is currently an artist in residence at SB Center for Art, Science & Technology.

Arturo Heredia Soto is a fne artist, co-founder and art director of Lum Art Magazine. He is also lead exhibition designer and graphic designer at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum (AD&A Museum), UCSB. He studied photography and painting at Mexico’s National School of Fine Art and image studies at the Graduate School of Art & Design, Mexico City. He is also on the board of directors for the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara.

Debra Herrick is co-founder and editor-in-chief of Lum Art Magazine. She is also associate editorial director at UCSB; a 2023 Individual Artist Fellow (Established) for the Central California region; and serves on the board of trustees for the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara. She received her PhD in Latin American literature from UCSB.

Madeleine Eve Ignon is a multimedia artist and graphic designer who works in a wide range of painting, sewing and collage techniques. She has been awarded residencies at Starry Night Program, New Mexico; Vermont Studio Center; and Drop Forge & Tool, Hudson, NY, and has exhibited internationally. She teaches art & design at SBCC and UCSB, where she earned her MFA. She is one-half of the experimental curatorial collaborative Beta Epochs, and is an artist-in-residence at Taft Gardens and Nature Preserve, Ojai.

Alex Lukas was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and raised in nearby Cambridge. His work focuses on the intersection of place, human activity, narrative and history through printed publications, sculpture, drawing, audio and experimental curatorial platforms. He is an assistant professor of print and publication in UCSB’s Department of Art.

Teddy Nava is a printer, noise-maker and reader from Ojai. In addition to his solo visual and textual work, he produces collaborative books and exhibitions as The Basic Premise and music as Jehanne.

Tom Pazderka is a painter, installation artist and writer. His work interrogates ideology, loss, belonging and nostalgia in a black & white palette of ash and oil. He is a founding contributor to Lum and his writings have appeared in The Philosophical Salon, Sublation Magazine and 3:AM Magazine His work has been reviewed and published in LA Weekly, New American Paintings, Dark Mountain, Santa Barbara Literary Journal and Daily Serving, among others. He publishes a semi-regular Substack art & theory newsletter A Secret Plot.

Silvia Perea is an architect and the curator of the Architecture and Design Collection at the AD&A Museum, UCSB. Perea holds a doctorate in architecture summa cum laude from the Polytechnic University of Madrid and has completed museum studies at Harvard. Throughout her career, she has combined teaching at international universities and publishing for online and printed media with the organization of exhibitions. As a curator, she has organized over 20 exhibitions for American and European museums, advocating for the integration of art and architecture to enrich their respective discourses.

Evelyn Spence is a UCSB graduate, a Santa Barbara Countybased reporter and managing editor of Coastal View News in Carpinteria. She has a bachelor’s degree in English literature and a minor in professional writing, journalism emphasis. She is going on her seventh year reporting and editing in the area, and is passionate about covering city government, breaking news and everything that makes Carpinteria, Carpinteria.

4 LUMARTMAGAZINE

THE ARCHITECTURAL FOUNDATION GALLERY

A dynamic space within a historic setting for curated exhibitions of contemporary art, photography and design

Saturdays 1-4 pm | Weekdays by appointment only

229 E. Victoria St. | Entrance on Garden St. | afsb.org

SPRING 2024 5

Imagemakers of the Americas

Sandy Rodriguez & Sarah Rosalena in conversation

edited by Debra Herrick

Late last summer, the stars aligned for a candid conversation between artists Sandy Rodriguez and Sarah Rosalena at a joint program for their concurrent exhibitions

Sarah Rosalena: Pointing Star (April 16–July 30, 2023) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara (MCASB) and Sandy Rodriguez— Unfolding Histories: 200 Years of Resistance (Feb. 25, 2023–March 3, 2024) at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum (AD&A Museum), University of California, Santa Barbara.

In their talk, co-hosted by Lum Art Magazine and held at MCASB, Rodriguez and Rosalena opened up about their intersecting art practices. They discuss how their researchbased work recovers knowledge from the past and present—and how by creating maps with materials and techniques of the Americas, such as weaving, beading and painting—they are able to portray distinct aspects of histories of resistance.

Sandy Rodriguez: Materials matter. As someone who works with handprocessed pigments and colorants of the Americas, I recognize the power and politics of materials to create potent visual narratives.

interested in how maps break down. How even within these histories, there are our bodies. Kin is there—as are plants, minerals and animals.

That’s something that I think is really powerful about your work. Our kin is

the physical process of handweaving, my manual handcraft. They overwrite and expand beyond their borders, pushing against their framework.

We employ materials and forms from past and present that express concepts and content that contribute to the history of imagemaking in the Americas. My work is as much about moments of resistance in our present moment as making visible our histories on a sacred ceremonial outlawed amate paper, with foraged hand-processed dyes and local pigments. I’ve had the opportunity to explore various shifts in my approach and now employ a digital and analog hybrid strategy to explore scale and compositions, layering hand-painted studies of plants and landscapes onto maps with my iPad before committing to a monumental composition.

Sarah Rosalena: Yes, the thread that moves through much of our work is mapmaking as resistance within the context of conquest. Both of us are

there. Our revolt is there. So much of the work is about the Chumash revolt; whereas being in Santa Barbara, you constantly see the residual efects of the Spanish mission system in its vision, style, architecture, naming and claiming.

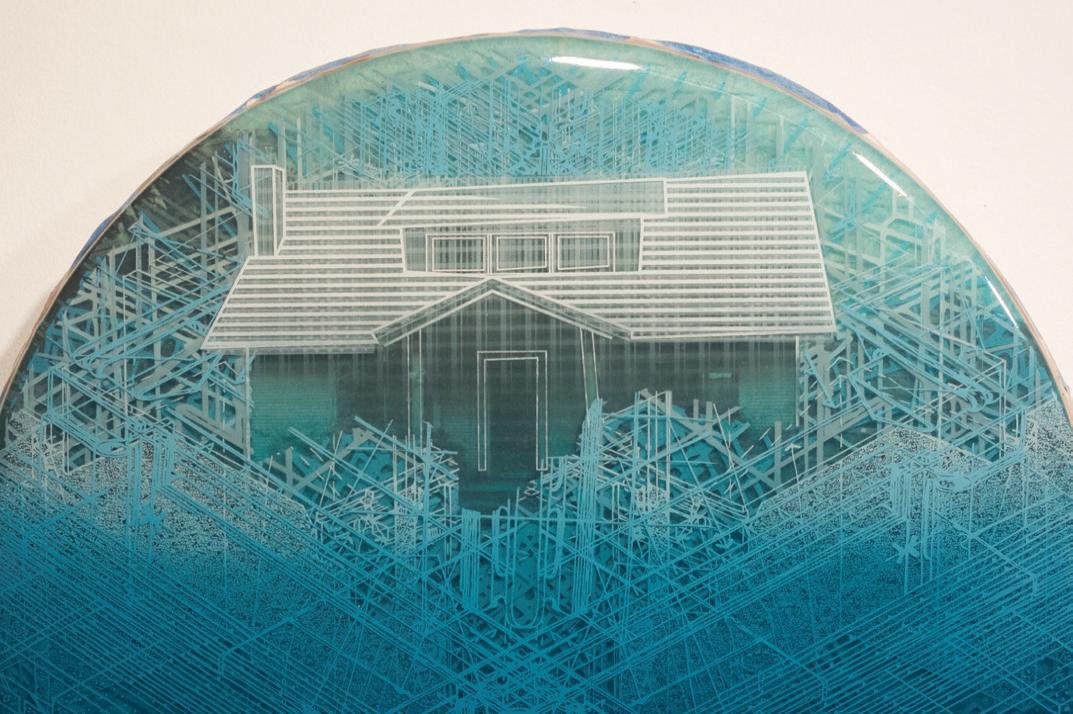

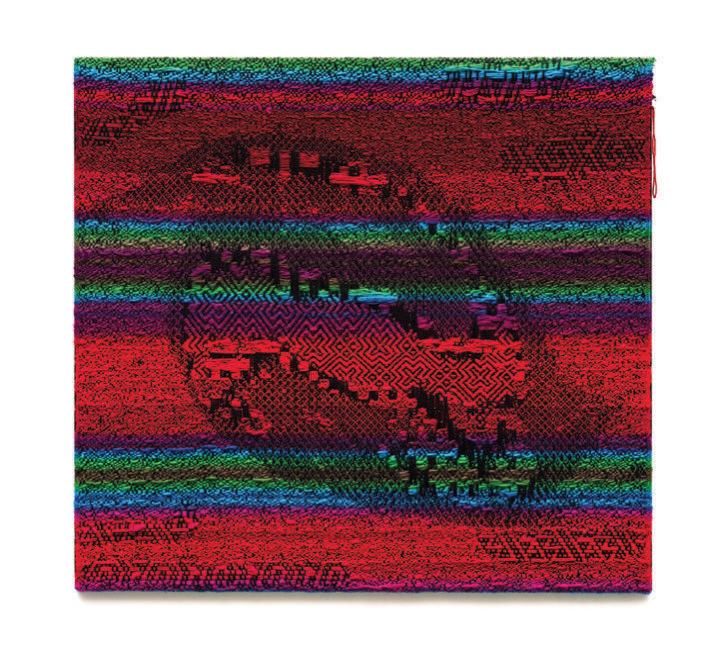

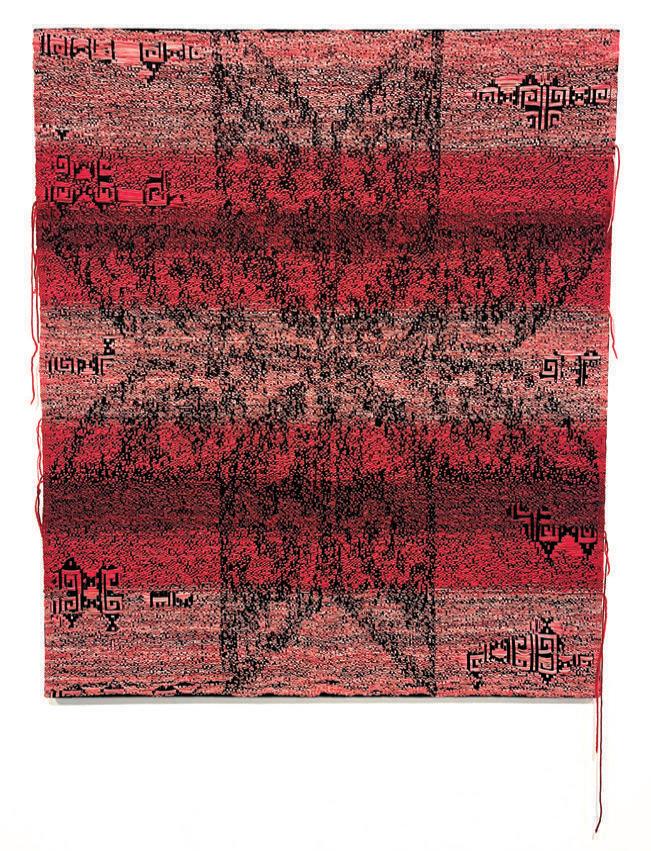

There’s power in the ability to render—to make things visible— through technology. It incorporates materials, patternmaking, craft, as well as digital making. For me, hybrid making is essential to reimagine the cartographic imaginary as resistance to mapmaking and legacies of colonialism in the Americas. It is important to understand how mapping leaves things unrendered, cropped and edited out. The work in the MCASB exhibition uses the idea of render and resolution, between digital and physical spaces, as a space to reimagine. Here the works generate meaning through combining and contrasting the cosmic and the earthly, and the artifcial and the natural, through my hand and machine.

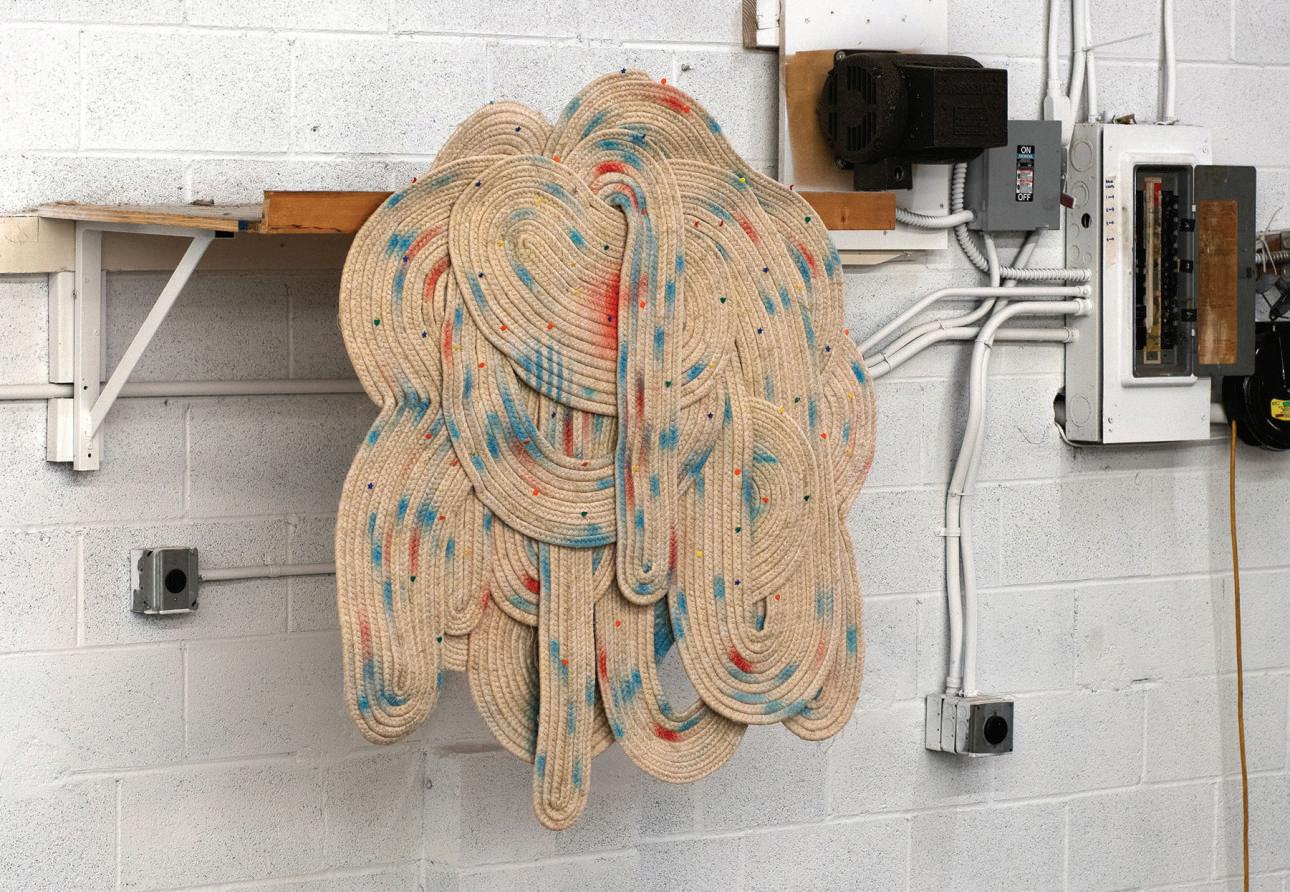

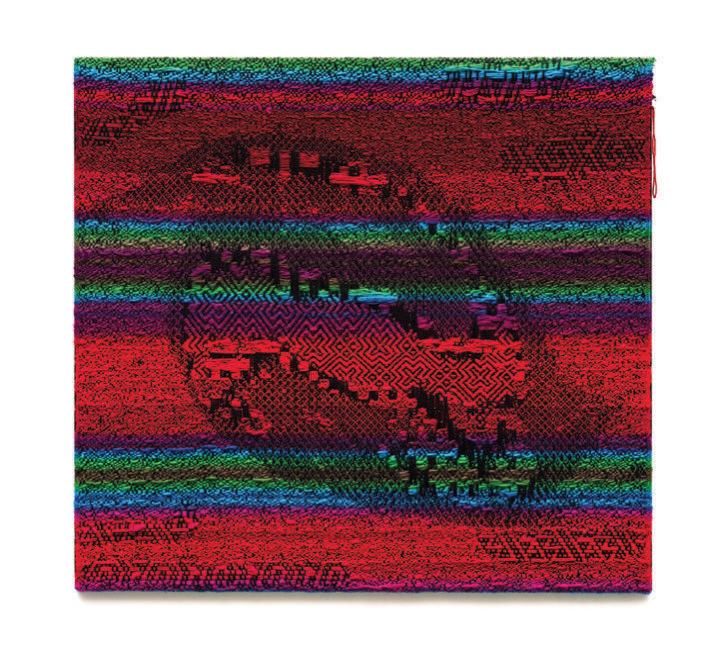

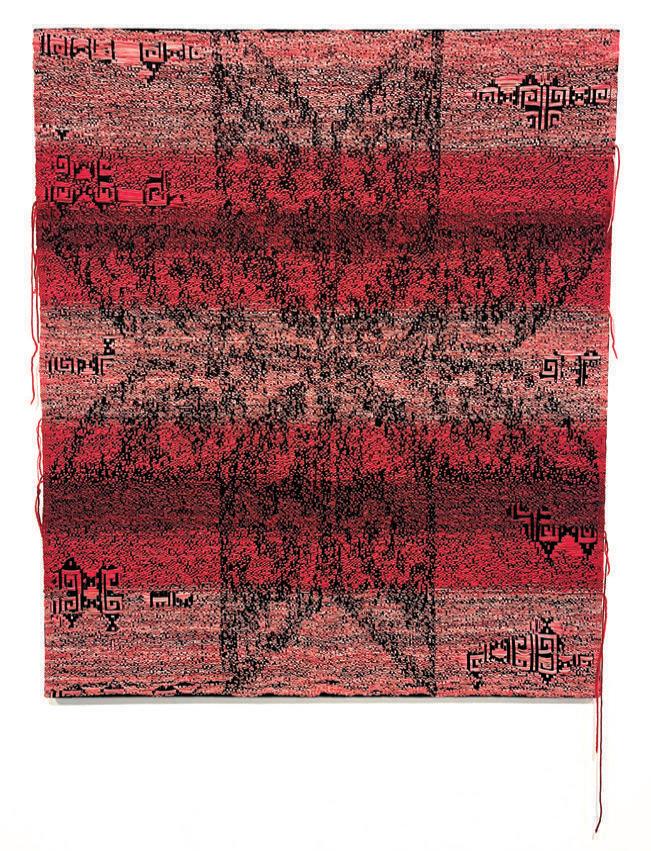

Though they were frst created digitally, the fnal work emphasizes

Textile edges are unfnished. Loose strands of yarn hang down from the sides of Eight Pointed Star and the Spiral Arm weavings. Long, black fringe remains at the bottom of one of the Dissolve textiles.

Much of the show talks about the politics of color, mainly about red, green and blue, the source of all digital color that generates a digital image. When you see something on a screen, it’s hard to know that it’s a micro mosaic of numbers, programmed with computer code between zero and 255, RGB (red, green, blue). I examine this pixelated palette within the digital imaginary through natural and synthetic dyes— both hand-dyed and processed—that change through each color across the woven terrain.

For example, I hand-dyed red yarn in separate cochineal dye baths so colors would oscillate through diferent shades of carmine: reds, oranges, pinks. The colors captured

or rendered from the dye bath are an important narrative for creating the work. They move, dissolve and transform rather than being a fxed color in place. In both Eight Pointed Star and Spiral Arm Red, shades of cochineal move past the boundary of each pattern and edges. They

SPRING 2024 7

Sandy Rodriguez, Mapa of Resistance & Revolt of Central Califas, 2023, hand-processed pigments, abalone, oil on panel (detail on opposite page)

Sandy Rodriguez, Pigment display & Materials case, whole & partiallyprocessed cochineal, red & yellow ochre, anterite, azurite, Maya blue, charcoal, gum Arabic, Phaeolus schweinitzii, walnut, acorns, mica, mussel shells, brush, dropper, mortar, pestle, glass muller

Sandy Rodriguez, Pronóstico No. 3, 2023, hand-processed watercolor on amate paper

ficker across and vibrate, trembling, expanding in and out of depth.

The power to render—to make something visible—is really important when talking about the question of how we break down borders and boundaries.

Rodriguez: While looking closely at Eight Pointed Star, I was really taken with the way you wove hand-dyed cochineal in wool and cotton. It is wonderful to observe the gradual shifts and saturation from intense deep reds to orange to pink. Not many organic colorants will yield this dramatic shift from purple and dark red to orange and pink through manipulating the pH.

Cochineal has a life force. This female scale insect has been cultivated for 10,000 years and feeds on the fesh of an Opuntia (prickly pear cactus) to produce the carminic acid. It takes more than 4,000 cochineal insects to

make each ounce of extract. It was one of the most coveted colors from the 16th to the 18th century—the most important red in the world in the early modern era and truly unmatched by any synthetic red. The politics of color, labor and trade are all part of the conversation when we talk about color produced in the Americas prior to the 19th century. This potent commodity was extracted from the Americas and monopolized by the Spanish. The legacy within economic power systems can be seen in collections of painting and textiles worldwide. It is a red that is of empire and Indigenous

knowledge. It becomes the color of power. And again, that is how color— how imagemaking—renders things visible.

Rosalena: I’ve been interested in stars since I was young. I would gaze at the skies and make fgures out of them. As a weaver, the star is not only something we think of in the sky, but it’s a symbol. Pointing Star, the show and the exhibition title, is about the symbol of the eight-pointed star, which is a symbol that represents the infnite because it’s made out of a certain amount of triangles that if you were to lay them within each other, could go on through infnity. The orientation of something expanding and boundless became a really important part of my work: how it could be used to map and visualize the cosmos and universe. How it signals the expansiveness of sky against cartographic tools used for mapping, knowing and control. How directions and coordinates dissolve.

I used the star symbol to reimagine digital imagery with weaving software, including digital images of stars. In some pieces, you can see a spiral which is based on an image of the Milky Way. The spiral arm of a galaxy disseminates, expands and breaks the pixel grid. In Spiral Arm Red, the star appears not as a singular fxed pattern, but as a conjoined, fractal pattern, enlarging outward from a single point. I like viewing it as an anti-compass or a compass rose for reorienting the

cosmos, grounded in earthly materials of clay, fber and plant dye. For me, the idea of cosmology can also be an Indigenous way of knowing because it is anchored on land.

Rodriguez: Some of my earliest memories of stargazing include sharing stories with family while camping. My interest in integrating nocturnal scenes is a way of engaging with pre-colonial elements as well as 19th-century American art history by inverting and layering these references. A range of historic and contemporary texts have helped expand my thinking around the cosmos.

For my show at the AD&A Museum, I painted one side of a monumental wood panel folding screen with a star-flled nighttime view from Limuw, also known as Santa Cruz Island, looking toward the coast of Santa Barbara, which includes a large comet. Throughout the Americas, the comet has been an omen and reference to cataclysmic events. You’ll fnd shooting stars, comets and constellations created with inlaid hand-chipped baby abalone shells, embedded against a sparkling charcoal-black night sky. I attempted a number of ways to inlay the abalone—including beach tar, pine pitch and beeswax—until I settled on one that was the most stable.

The research takes time: searching for references, reading journal articles and books, and having conversations with a range of people. Over the past few years, I have had the opportunity to spend a few months a year under the dark skies of Joshua Tree working at the Joshua Tree Highlands Artist

8 LUMARTMAGAZINE

Sarah Rosalena, Axis, 2023, smoked stoneware, 3D ceramic print

Sarah Rosalena, Dissolve, 2023, cotton, hand-dyed acrylic yarn, image source Andromeda Galaxy

Sarah Rosalena, Eight Pointed Star, 2023, hand-dyed cochineal wool yarn, cotton yarn

Sarah Rosalena, Spiral Arm Red, detail, 2023, hand-dyed cochineal wool yarn, black cotton yarn, image source Milky Way Galaxy

photos by Ian Byers-Gamber and Ruben Diaz

Sarah Rosalena, Spiral Arm Red, detail, 2023, hand-dyed cochineal wool yarn, black cotton yarn, image source Milky Way Galaxy

photos by Ian Byers-Gamber and Ruben Diaz

Residency. Gazing at the stars and meteor showers helps me recharge for the day’s work ahead. It’s something that we miss under the light pollution of Southern California. It’s something that we need as people. My time in nature grounds me and allows me to reconnect with place

Rosalena: So much of our knowledge and stories are embedded in the stars. How much has been lost with light pollution? We would never know looking out today. How we see things, how we interpret—that's the power of rendering—and stars are rendered through darkness. The idea of darkness inspired my use of a black warp on the textiles. The 3D printed ceramics in the show were pit-fred by smoke—creating a unique gray-black color—capturing the sense of earth, fre, water and air as abstract methods of mapping with carbon.

Darkness is this beautiful sacred space where we are able to see things. But how do we reclaim the sacred? It’s land, it’s kin, it’s bodies, it’s my blood. It’s complicated. It crosses many boundaries and borders. We are here on unceded Chumash land in a town—Santa Barbara—that is modeled around Spanish colonialization. I think it’s a perfect analogy for that system. That cycle is so embedded in this space. How do you reverse that?

Rodriguez: I don’t know, but we can try. Over the past seven years, I’ve been making maps and conducting research as part of my series Codex Rodriguez-Mondragón. I’m a border child of Mexican parents: Rodriguez from Zacatecas, and Mondragón from Tijuana. My earliest memories of reading paper maps are on family road trips across Mexico and the US Southwest in a green VW bus in the early ’80s. Mapping is a way of locating oneself and the history of a region.

The eight works in my exhibition, Unfolding Histories: 200 Years of Resistance, were created with locally sourced pigments including red and yellow ochres. My exhibition includes a

doublesided monumental wood folding screen, a large accordion book of local medicinal plants, a set of endemic botanical portraits, a large map on amate paper, a kinetic light sculpture and a display of my raw pigments. With this exhibition, I am mapping the Central Coast of California to make visible a history of resistance in the region over the past 200 years. The exhibition provides opportunities to reconsider a past and present while interrogating dominant narratives, reconsidering the largest organized resistance movement to occur during the Spanish and Mexican periods in California in 1824. In 2020, over 10,000 demonstrations and protests against police brutality took place across the country and protestors were assaulted with tear gas and chemical weapons by local and federal police in 100 cities, including San Luis Obispo.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a large 94.5 x 94.5-inch doublesided folding screen. The format and visual language (narrative history and mapping) of the painted folding screen was introduced to New Spain/ colonial Mexico by the Japanese. Both the narrative scenes and the nocturnal view of Santa Barbara from Limuw/ Santa Cruz Island are painted in handprocessed local pigments I collected or was gifted. The painting is made with a range of materials including hand-processed charcoal, mica, ochre and select modern pigments. The folding screen/biombo is contextualized by paintings depicting recent fres in the region, showcasing the violent imposition of European land perceptions and exploitations of Indigenous ways of relating to nature. I also include botanicas inspired by feld study that took place in 2021–2022 at Santa Barbara, Santa Ynez and Limuw/Santa Cruz Island for my fourth solo museum exhibition.

During 2021–2022 I consulted with artists, sociologists, ethnobotanists, anthropologists, art historians, conservators, as well as conducted feld study trips to Limuw, Santa Barbara and the surrounding region, as well as the missions at Santa Ynez,

Santa Barbara and Santa Purisima to investigate sites and materials that inspire these works. We produced a limited exhibition catalog with scholarly essays by Charlene Villaseñor Black, Ella Maria Diaz and Jonathan Cordero that is available on the AD&A Museum’s website.

Rosalena: Your research in these spaces and places is crucial and depends on constant, strategic eforts to refuse the endless repetition of the West’s cartographic imaginary of California. I am very much looking forward to your upcoming event with the AD&A Museum for the anniversary of the Chumash Revolt. Within this visibility, there is a now and a future There is an intimate relationship between the sky and the earth— beyond colonial hierarchies—that can reorient us.

There is a large Indigenous community in Santa Maria, Oxnard and Santa Barbara County. During my exhibition at MCASB, the museum held a youth circle for children of farmworkers with Zapotec master weaver Porfrio Gutierrez. The conversation was translated into Mixteco and some Zapotec, which created this incredible echo of Indigenous languages over colonial Spanish and English. It was powerful to listen and experience with youth. For many of them, it was their frst art exhibition and museum experience. Many had family members or knew people in their community who were traditional weavers. Having this exhibition shown in a contemporary art space using evolving techniques was very important for future generations. There is power to show and see us, and to uphold legacies of resistance.

In fall 2024, Sandy Rodriguez and Sarah Rosalena will have works on view in the same exhibitions as part of Getty’s PST ART: Art & Science Collide at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara.

10 LUMARTMAGAZINE

SPRING 2024 11

12 LUMARTMAGAZINE ********************** ********** ***************** *****

SPRING 2024 13 ******************** **********

14 LUMARTMAGAZINE

Revolutionary nostalgia

by Tom Pazderka

All revolutions have the (un)fortunate side efect of altering much more than what they’ve initially set out to change. Whether we’re talking about a political act or a scientifc breakthrough, a revolution begins with a magical act. What was previously seen as impossible, in a moment, is overcome. Spontaneous outbursts of mass movements (often accompanied by violence) cause major political upheavals, innovations in science and medicine cause humans to live longer or reach other planets, while artistic revolutions cause us to perceive and see in radically diferent ways. Revolutionary moments happen quickly. But their afterefects can be felt for many years.

The second magical act occurs within historical hindsight, when revolutions morph into predetermined events that were always about to happen. A strange phenomenon is thus produced. A revolution changes not just the present order of things and all future outcomes, but through the third and fnal magical act, the revolutionary moment also changes everything that led up to its moment of realization, including itself. History becomes liquid and phenomena fall prey to object impermanence. The past becomes nothing more than a projection screen for the neuroses and pathologies of the present. What is true today is usually false tomorrow. Nothing can stand upright in the quicksand of revolution.

Metaphysically, revolutions are a combination and product of calculated necessity and Faustian bargains, whose symptom takes the form of nostalgia. The profound anti-historicism of nostalgia acts as a countermeasure to the liquid conditions of volatile times. It’s also a coping mechanism for dealing with the aftermath of the failures of the cold (ir)rationality of revolutions. The permanent revolution of technological innovation collapses time into incoherent and countless instances, most of which do not align with one another and provide not only an inaccurate version of events, like a copy of a copy of a copy, but an entirely fabricated alternate reality.

“The past has never been so close to the future, to the point where we cannot help but doubt whether the modern age was nothing more than one long dream: the Promised Land, peaceful and skillfully governed by cybernetics, is turning into a cybergothic nightmare marred by confict, bigotry, and superstition. Indeed, across the globe, reactionary movements are calling for the end of modernity and a return to various prior confgurations.” — Revolutionary Demonology, p. 83

Mapping Failure

At the core of revolutionary nostalgia is the operative nature of failure. The fundamental ontological principle of revolution is always a referendum upon the existing order of which the

prior revolution was one of the major building blocks. Failure is thus the ontological event from which all revolution proceeds and expands. By extension, failure is thus always present and included as part of the new order. As a result revolution leaves the present, the future and the past ontologically incomplete, always subject to new reinterpretation and to the possibility of inclusion within a fundamentally new alternate reality, often running parallel to the actually existing reality.

The human condition is subject to the functioning of the revolutionary process as a necessary component of change. Without change, the human condition stagnates and worse, deteriorates. Political, social, scientifc and artistic revolutions inaugurate changes to the existing paradigm by solving problems that previous revolutions caused. In politics, the aim of revolution is to change and replace existing institutions, while in science and art, revolutions aim to assert a new paradigm to which prior revolutions have led the way. The failure of revolutions at crucial stages owes its existence to how revolutions aim to change the structures and paradigms of institutions in ways that those same institutions prohibit. This creates the space for inevitable failure. It is difcult to not fall into the metaphysical trap of predestination, but that is precisely what the advent of change and revolution signifes.

Nostalgia enters into this logically circular system as a symptom. It attempts to fll in the gaps left over from the moment before failure entered into the system. But because failure is an ontologically implicit part of the revolutionary system, the symptom of nostalgia cannot be efectively exorcised and so it remains one of the major building blocks of the symbolic order post revolution.

Among the many functions of nostalgia is the ideological restoration of the lost cause or prior state, in other words, a revolution in reverse, a move backward not just in time, but in memory. Failure is therefore rearticulated in many guises in the present as a kind referendum or shield against the fow of historical phenomena. Many well-known large scale rebellions and revolutionary failures exist as potential sources of reanimated agency and tend to be hot topics of debate decades, even centuries, after their original energy had been depleted.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the events of the revolutions of 1848 which revealed Marxism to be its preeminent symptom of revolutionary nostalgia. The Spanish Civil War did the same for Anarchism and 1989 did so for Communism. The same revolutionary nostalgia exists on the more conservative spectrum as well. What the American Revolutionary War did for nationalism, the Industrial Revolution did for capitalism, and in the minds of many Western nations, 1989 was seen as a referendum on the Cold War, inaugurating the nostalgic reanimation of neoliberal and neoconservative ideologies.

SPRING 2024 15

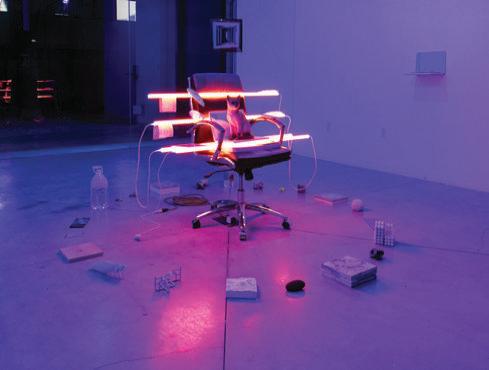

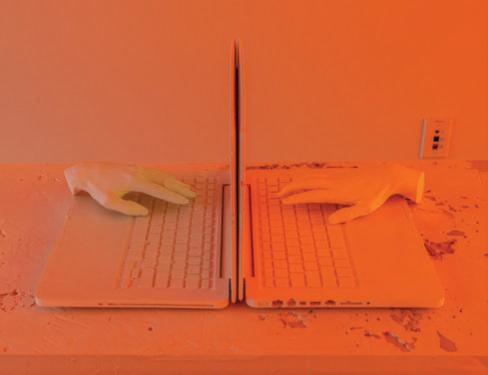

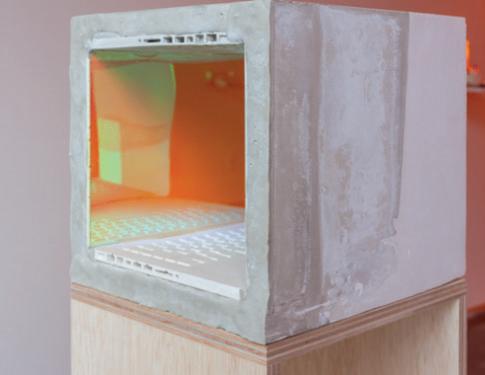

Dead Ambassadors Kevin Clancy

by Julian Harake

Acracked iPhone screen spells disaster for most people. For Kevin Clancy, it’s a moment of transformation.

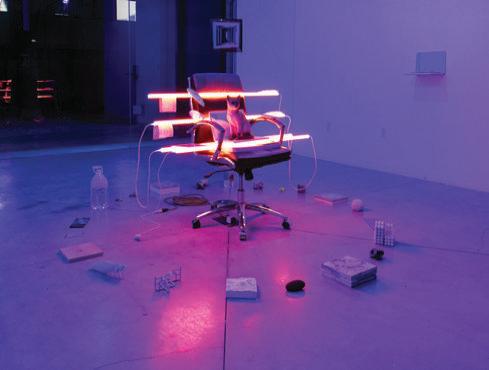

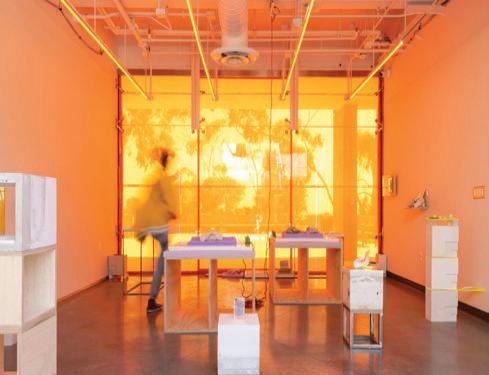

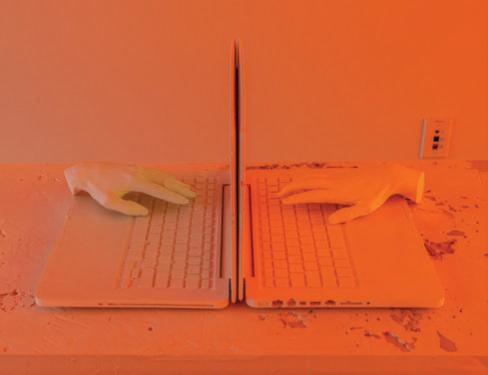

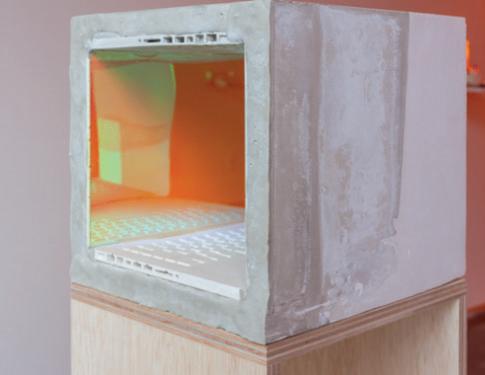

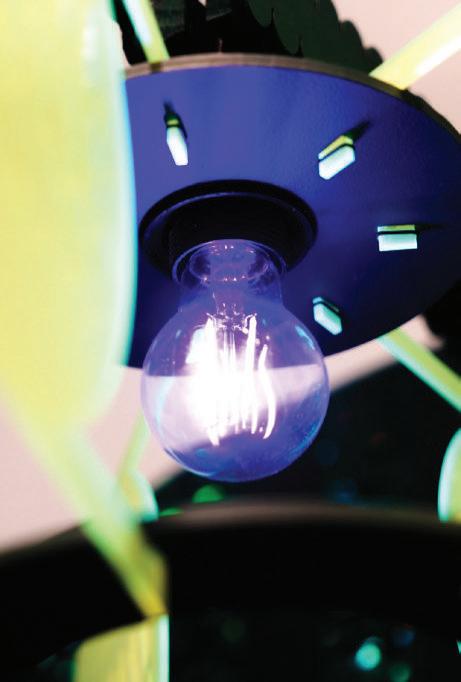

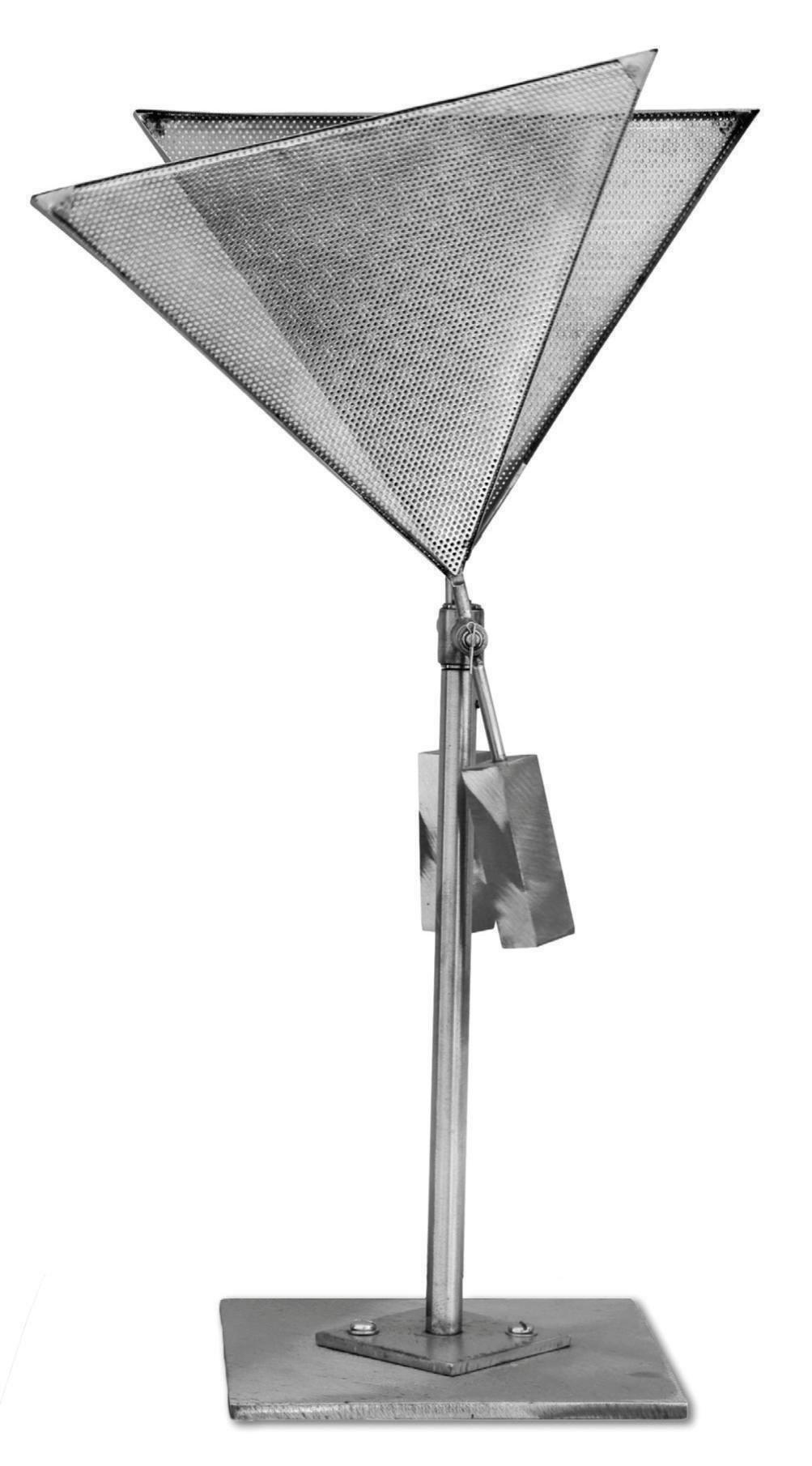

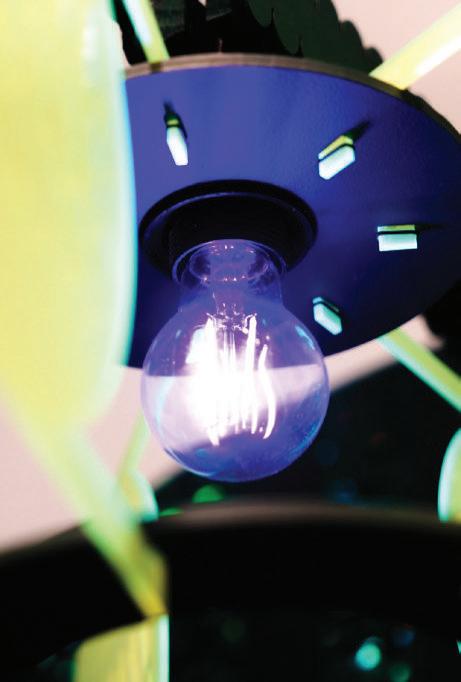

A cell phone fies from our hands, landing on the pavement; water spills on a keyboard; the internet is out; a cat jumps on a desk; a Zoom meeting is interrupted. These sudden perceptual shifts are rendered solid objects, made from plaster, resin, dichroic flm, latex, LED lights and other engineered materials.

Clancy—a sculptor, Pittsburgh native and teaching fellow at UCSB’s College of Creative Studies—explores how our attention and gadgets meet the entropic infuences of the real world. The resulting works are ethereal and foreboding. In The Ubiquity of Loneliness (2017), a cracked glass screen protector separates two nearly-touching plaster fngers: a contemporary redux of Michelangelo’s The

Creation of Adam. W3B5 (2022), a laser engraved acrylic spider’s web, is an object both intricate and crude, referencing the strength of design found in nature that humans fail to match. In Hollow Holo (2019), several plaster hands, holding dichroic screen protectors, foat against a gridded retail display structure, forming an LED illuminated altarpiece for a disembodied and commercially driven culture.

Regardless of scale or materials, Clancy's sculptures appeal to our haptic and visual senses; the multitudinous ways and degrees by which we meet the world— whether distractedly through our phones or more presently through our hands. Hand wrought plaster casts of iPhones, iPads and MacBooks—sometimes propped onto each other or turned into water fountains—attest to a culture too visually distracted to notice its degrading corporeality. Yet such undertones are not overbearing,

and his sculptures are open enough to project other things into them: plaster death masks, one’s own aging, the climate crisis, the loneliness epidemic or the artist himself.

The collective efect of these works is not unlike Borges’s The Secret Miracle, where time slows down as the protagonist faces execution by fring squad. As bullets hurl toward him, he is granted a full year— experienced by only him—by which to fnish his novel.

Whether fctional or real, the transcendental potential of one's own perception and revelations around the despair of ecological ruin, commercialism, neofascism and pandemic ofer artworks of unexpected possibility.

As Clancy laser etched on dichroic window flm, “Other worlds are possible.”

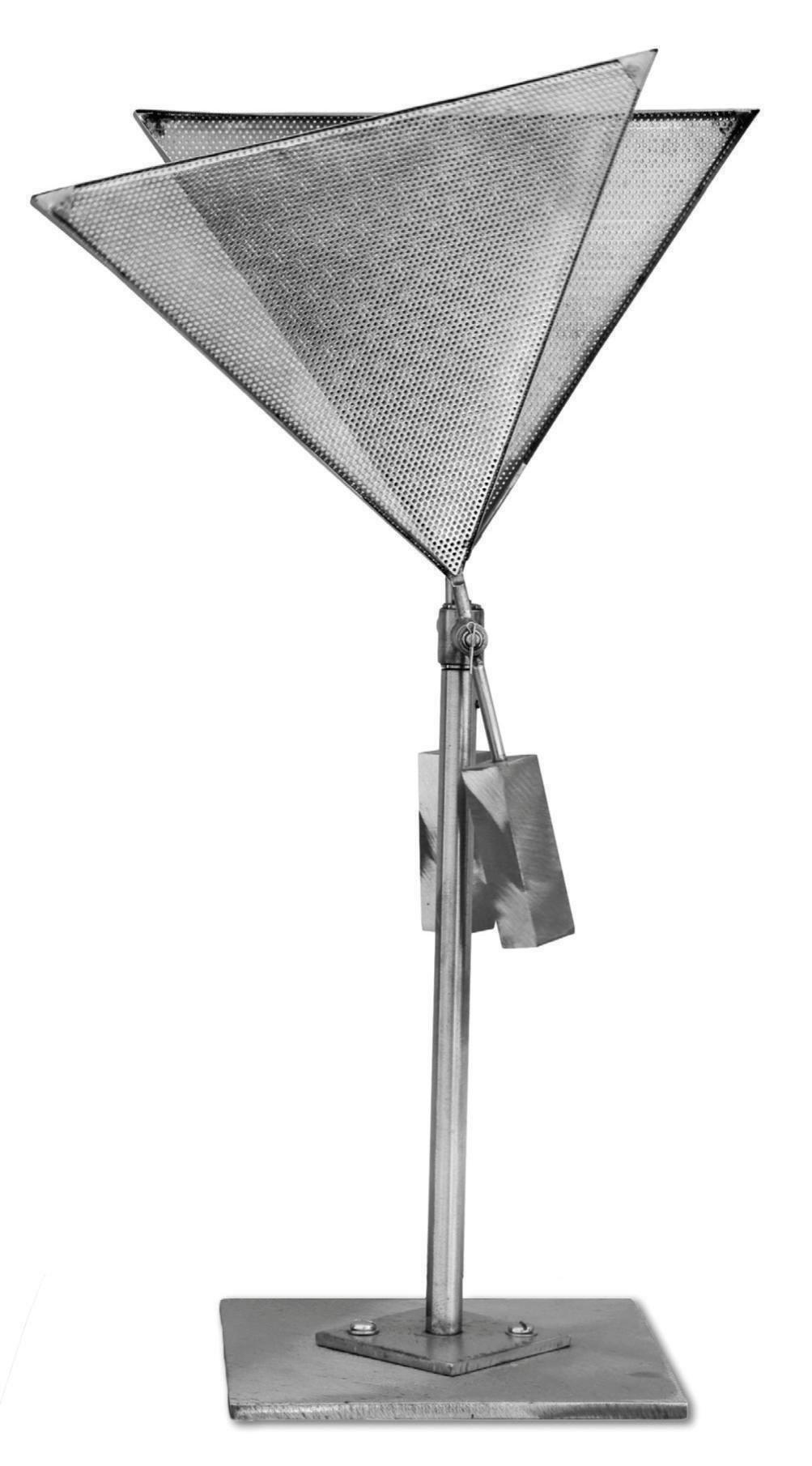

Kevin Clancy, portal, cast hydrocal, dichroic flm, steel

SPRING 2024 17

Works by Kevin Clancy from Screen Time Paradox, Weaving Three Rivers, aether net, IRIS_SIRI, No Internet, Cabinet

Fieldwork

Dalia Garcia & Narsiso Martinez in conversation

edited by Debra Herrick

Dalia Garcia: I’m an Indigenous Mixteca from San Juan Mixtepec, Oaxaca. I have lived in Santa Maria for almost 20 years; and I’m the program director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara.

Narsiso Martinez: I’m from Oaxaca, from the Zapotec region, and I'm also an immigrant, and I make art.

Garcia: As an Indigenous woman that used to work in the felds, I see your pieces as powerful but at the same time, I have questions about your intention and what it is that you are seeing.

Martinez: Since I was a kid, I have drawn people on pieces of paper with just pencil—farm workers—because I was working in the felds, and that was the subject matter at hand. Then, when I began going to art school, I started painting the felds and fruit and orchards that surrounded me too.

I was in the felds to earn the money to go to school but when I started painting portraits of farm workers, people started asking me questions about who these people were and

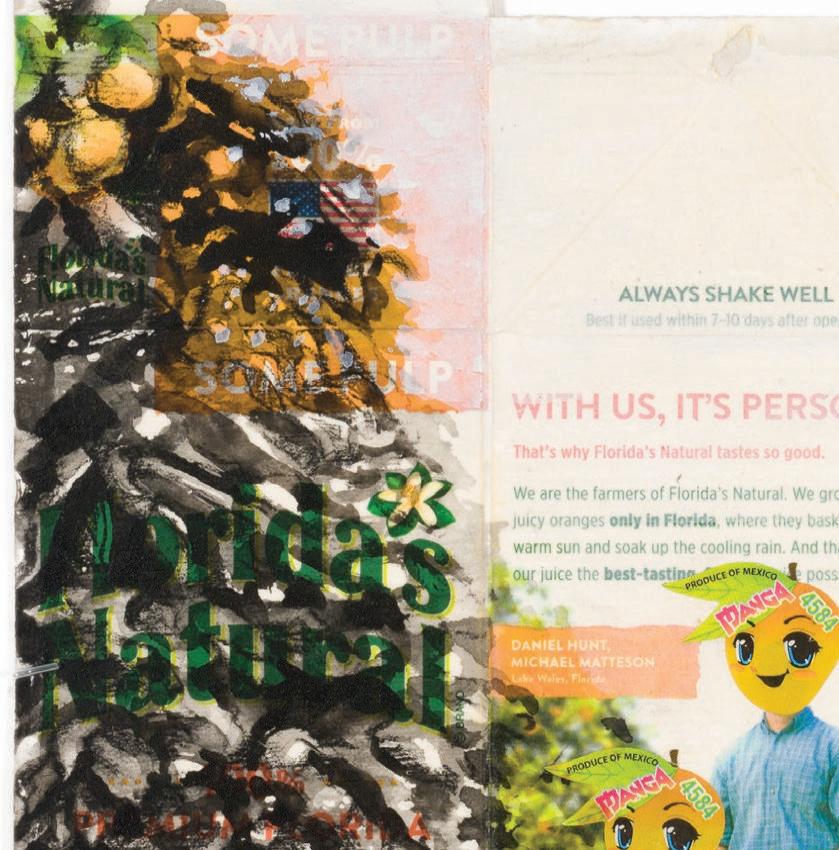

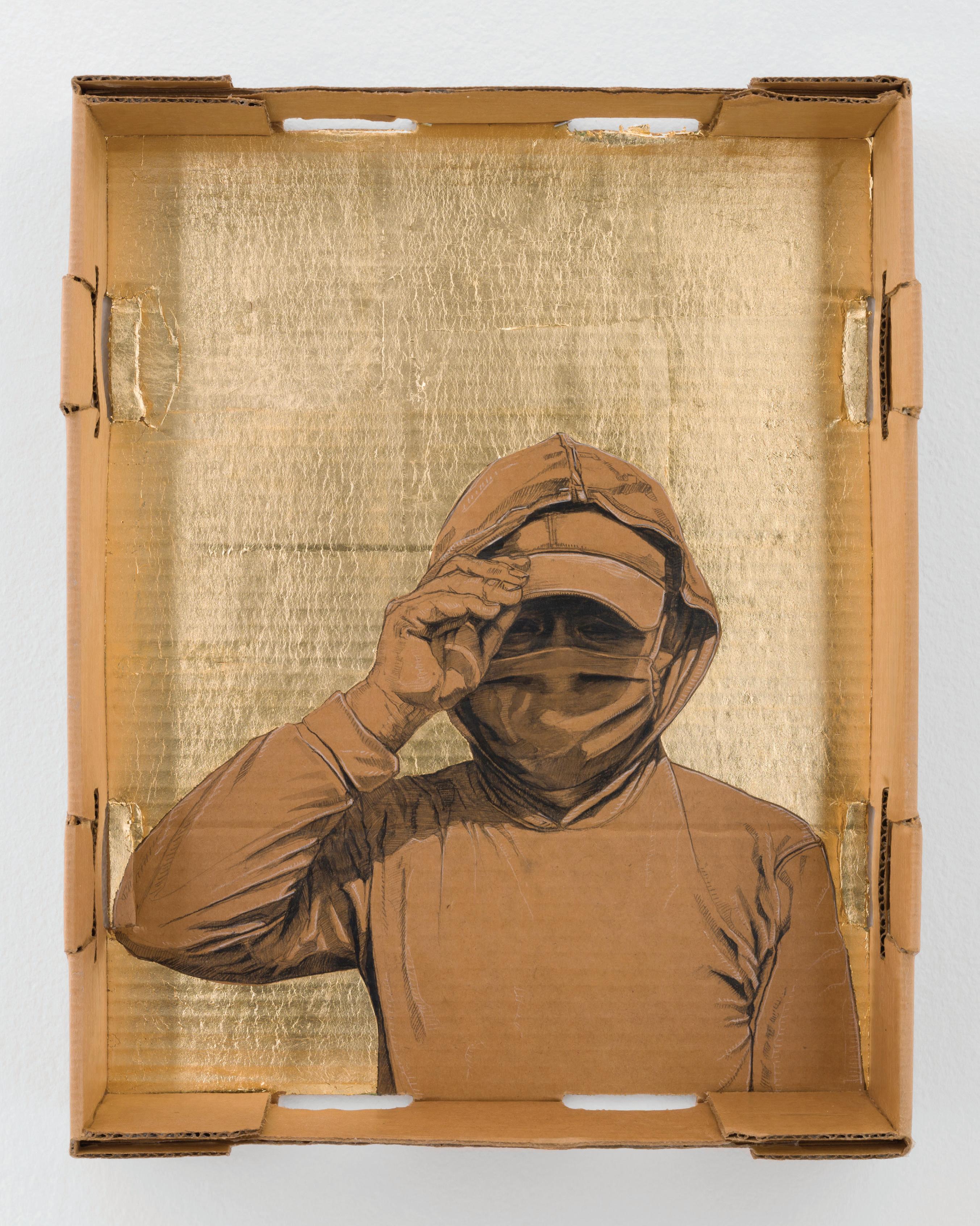

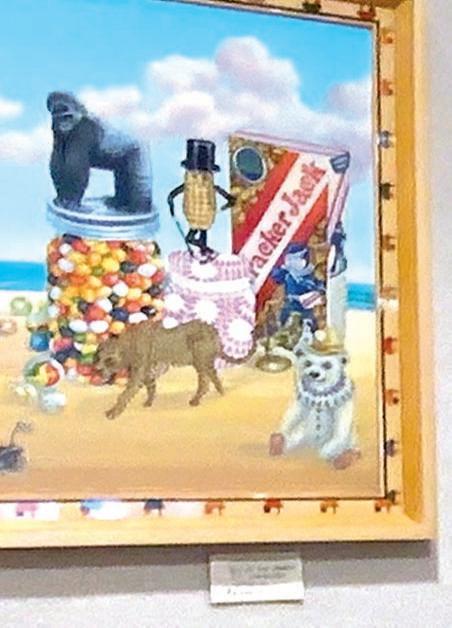

Narsiso Martinez, Fruit Catcher, 2021, ink, charcoal and gold leaf on produce cardboard box

why I was painting them. Later on, as I started working with farm workers from diferent countries like Honduras, Salvador and Guatemala, I realized that we all had something in common: We were immigrants. Some of us were undocumented, so we also couldn't speak up. Sometimes the foreman wouldn’t even know the owners of the orchards. So how could we complain about something? I realized that I was able to tell stories about these struggles during critiques of my work.

People who are not from the felds or who are not familiar with what happens there, were learning about feldwork through art; and I realized I could use art as an excuse to talk about issues from the felds.

I decided to create fgurative art because I wanted the audience to understand these people and I wanted these people to understand and see themselves in art. I considered creating abstract or conceptual art but then the farm workers, I felt, wouldn't understand the art. I think at the end of the day, I just want visibility and acknowledgement for them.

Garcia: I think that’s how I see it. Most of the time we are invisible because we are Indigenous. I think we normalize that because we’re undocumented immigrants and working in the felds is the main thing that we do as labor in the US.

I learned in the felds that there’s a lot of struggle. There are a lot of stories that people don’t tell. The

perspective of feld workers is that we are feld workers because we’re 'less than' because we come from impoverished communities. We don’t see the richness of who we are—the labor that we bring—and the culture that we ofer to the towns we live in.

So when I saw your pieces, I felt they portrayed the people that work in the felds through a diferent lens. In our communities, people ask: ‘Why are you studying art?’ ‘How are you going to make money with it?’ Going into the arts is unappreciated. By going into art, you’re challenging that. By portraying people in the felds, it feels again, like a diferent lens. I will say that we feel good about it and that it feels dignifed.

One of the things that is particularly

SPRING 2024 19

Narsiso Martinez, The One, 2023, ink, gouache, charcoal, and acrylic on banana box

unique is the material that you’re using, the boxes for the companies. Where did the idea to use boxes come from?

Martinez: Maybe two or three diferent situations led me to the boxes. I saw an exhibition of one of my professors who had at least one painting on cardboard and I liked that. But it didn’t occur to me to actually paint on cardboard until I was working in the felds after fnishing my undergraduate degree in 2012. I worked in the felds for three consecutive years after graduating, from 2012 to 2015. During that time, I had my studio in my sister’s garage. When she would go to Costco, she would bring all these boxes home. I would use them as canvases because I didn’t have enough money to buy

canvases. I would cut of all the labels and the edges of the boxes and use the bottom part of the box—the good part to draw on—or I would go outside and do plein air paintings.

When I went back to school for my MFA, I wanted to continue doing oil paintings but the critiques were a lot more technical. Was I a good painter? Was I not a good painter? Was the proportion right? Things like that. Nobody would talk about the issues that I wanted to talk about, which was the community of farm workers and the working class. At one point, I was so frustrated that I stopped painting. I wanted to do something that I was used to doing without anybody telling me whether it was good or bad. So I took a box that I had from Costco to my

studio and I drew a ‘banana man.’

I called it that because it was a box for bananas. I didn’t cut the labels of yet. I drew it on the center and it barely touched the labels.

When I showed this drawing, there were diferent kinds questions. They weren't asking about technique. It was more about who this person was and why I chose them. I would answer with my own experiences from working in the felds. Because I had already established that I wanted to paint the working class, not the wealthy, the connection and the theme evolved to be about agribusiness and farm workers.

One of my professors mentioned ‘seriousness.’ He was like, ‘Let’s see how serious Narsiso is with his boxes.’ But I was still doubting

20 LUMARTMAGAZINE

Narsiso Martinez, Good Morning, 2021, ink, gouache, sticker and charcoal on juice carton

what I was doing so the word ‘seriousness’ was key. I started collecting boxes and doing more complicated compositions on more boxes, and some sculptures too.

Garcia: When you work in the felds, at least if you do contract work, such as picking strawberries, the main thing you need is to fll up boxes because they pay you by the box. The boxes have a correlation to the struggle of working in the felds. Those boxes have that relationship between labor and the corporate world.

I know people that work in the felds can understand what a box in feldwork means. But at the same time, people that are outside of feldwork can also see that boxes are part of the corporate world that moves the product of our labor. The boxes can be just boxes for some people while for others, they can represent the exchange of labor. But it is not just labor, you can also see the political heaviness when we talk about exploitation or racism, well, at least for me, because I don’t want to suggest that people from Oaxaca are the only ones working in the felds.

Still, from my perspective, as an Indigenous Mixtec woman—whose family came from that history of immigrating from Oaxaca to the US for work—these boxes represent the corporate world and the people that you portray on them, they are the ones doing the labor.

Martinez: It’s difcult to somehow have the corporation and the people who work in the felds together. Sometimes we don’t even know who the owners are or who is the real manager. We would always hang out with the foremen who were also from our countries, who also didn’t speak English and who also sometimes didn’t know the rules or how to treat people.

Narsiso Martinez, USA Product, 2021, gouache, charcoal, collage and matte medium on cherry box, collection of the University of Arizona Museum of Art

Garcia: It’s not just a question of labor either. There are social aspects. For instance, it’s not one community. There is a lot of division and questions of identity. Who works in the felds? Who has a position of power? Who is paid what?

The felds speak to diferent things. Most of the time, it’s not good things, but I feel that your pieces show the beauty of the people. Even though people are struggling working in the felds, they still have positive attitudes.

Martinez: Throughout history, portraits have been reserved for the wealthy, and that’s another aspect of making portraits of farm workers. For example, Sergeant Singer, the American painter who made portraits of all these wealthy people—all these landowners—who were posing for these paintings. And

who cares about the people who work in the felds—the actual farm workers? Maybe they were here and there, but they were never the main subject. In contrast, in my work, farm workers are the main subject.

I tell my family, ‘This is you, but it’s not all you.’ It’s just a representation. Sometimes, somebody I painted in the felds as a high school student, goes on to college and graduates. I think it’s fair for the work to include farm workers who are not just in the felds. It’s important to highlight that we are capable of other things.

Garcia: I think that’s part of it, wondering who they are and where they are right now. Communities in the felds have diferent backgrounds. It’s people who recently got to the United States and need to work, but sometimes they’re doctors or they have some type of profession back in their

SPRING 2024 21

country. Or you can fnd high school students that are working just for the summer. And you also fnd people who work all their lives in the felds.

Martinez: I didn’t know anything about Mexican history until I studied Latin American art history, and I realized that it was not my fault. It’s not the fault of the people. The whole system is horrible and keeps us that way. But I’m happy that a lot of kids from my hometown are now getting college degrees and are more aware of their surroundings.

Garcia: I feel that more than ever because I got here when I was 16 in 2004, and I feel that more of that conversation is happening in our new generation, born and raised in the United States. Before we didn’t know to describe in terms of racism. But now we know that’s racism: being discriminated against because of who we are, how we look or our socioeconomic status. It’s part of that racist system that doesn’t just happen in the US. It also happens in Mexico and in our towns.

I’m also an artist but it took me a long time to feel comfortable saying that because even though I know techniques for textiles I didn’t see it as practicing art. I thought I needed permission from an institution or someone outside my community. You opened a pathway for others to understand that what we produce and what we do is art.

Narsiso Martinez, Pacifc Gold, ink, gouache, charcoal, collage, acrylics and small paintings on produce boxes

images courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery, LA

photos by Yubo Dong

22 LUMARTMAGAZINE

Made by Hand/ Born Digital

Alex Heilbron, Taha Heydari, Yassi Mazandi, Justin Mortimer, Analia Saban, Ena Swansea, Sarah Rosalena and Joey Watson Santa Barbara Museum of Art, March 3–Aug. 23, 2024

by James Glisson

Either/or oppositions are everywhere, and they have the virtue of compressing complexities into easy to remember pairs. Cats versus dogs; socialism versus capitalism; secular versus religious; coffee versus tea; pen versus pencil; or friend versus enemy. Their virtue is being a cognitive shortcut to keep attention focused. No better way to lose an audience than meandering through a thicket of facts. This virtue is also a vice, however, as it drains away color and subtleties, leaving us to deal with unreal stark binaries. Their simplifications can obscure entirely what is out there IRL, in real life, turn into accidental misrepresentations, or even lies with everything from minor miscommunications to horrific injustices following suit.

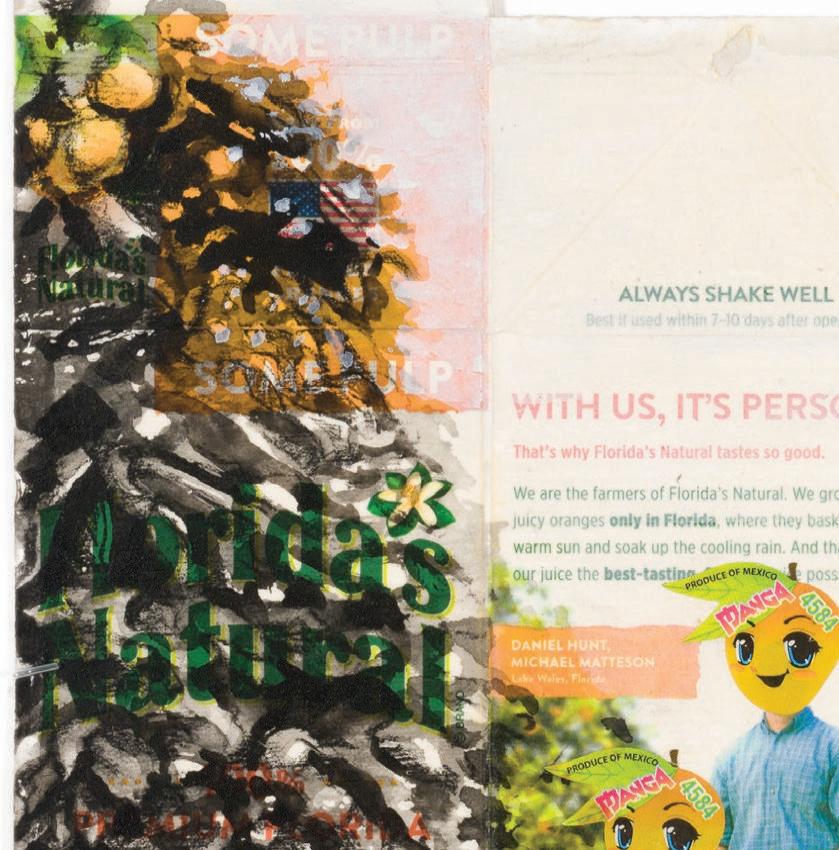

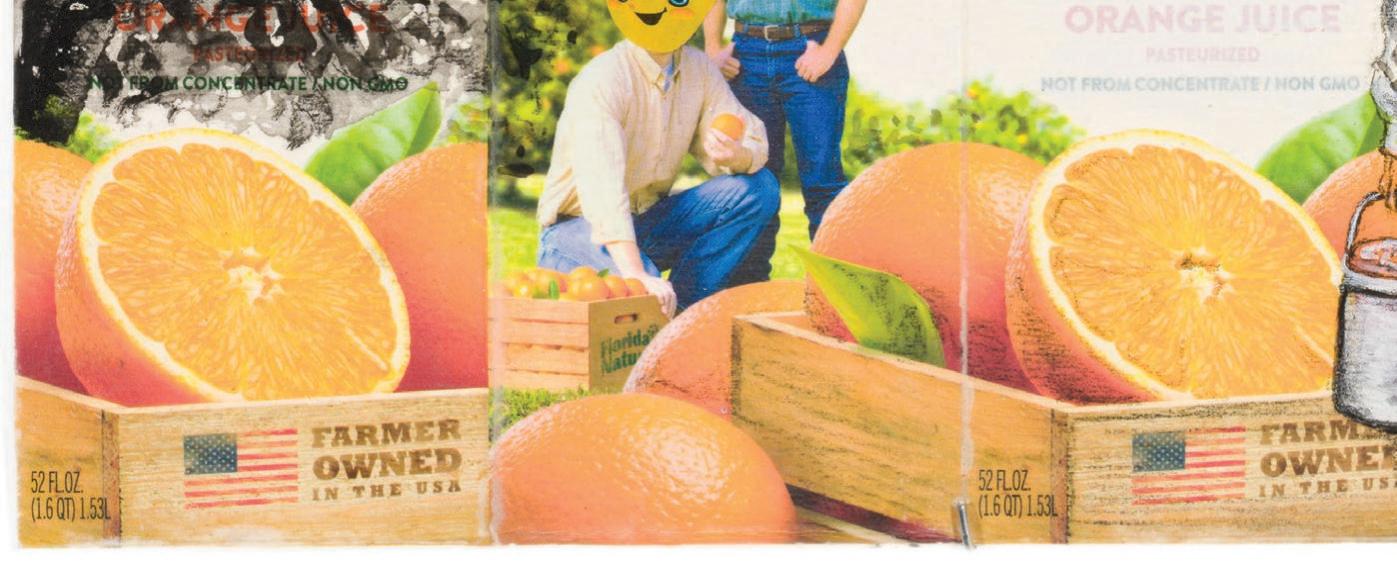

Over a series of studio visits over the past year, I saw that one such opposition—analog versus digital—did not hold up when it came to contemporary artists. I kept encountering artists who paint, throw clay on a wheel, or work with other mediums making objects by hand, yet they all turned to digital tools at stages in the process. The Santa Barbara Museum of Art exhibition Made by Hand/Born Digital (March 3–Aug. 25, 2024) features artists who use brushes, AI, paint, 3D printers, scissors, magazines printed on paper, digital looms, potter’s wheels, Photoshop and Apple Photo (formerly iPhoto), and who complicate a clean distinction between the hand made and digital. These artists are neither nostalgic for an analog past nor starry-eyed about a digital future, but they all do make a critical and important intervention, one both obvious but also in

Taha Heydari, Reterritorialization, 2023, acrylic on canvas, courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett, NY

SPRING 2024 23

need of reiteration: These machines are nothing without us to hold them, fill them with content, plug them in and fix them. (At least until the demonic entity of the AI singularity arises to punish humans like an angry Biblical prophet.) While infinitely more complicated and capable of something like human cognition and creativity, AI is a tool just as brushes, straight edges and kilns are tools—an instrument wielded by a person towards some end. This article explores a selection of the artists in the exhibition, Ena Swansea, Yassi Mazandi, Analia Saban and Taha Heydari, and it shows how their hybrid ways of working confound the distinction between working by hand and using digital tools.

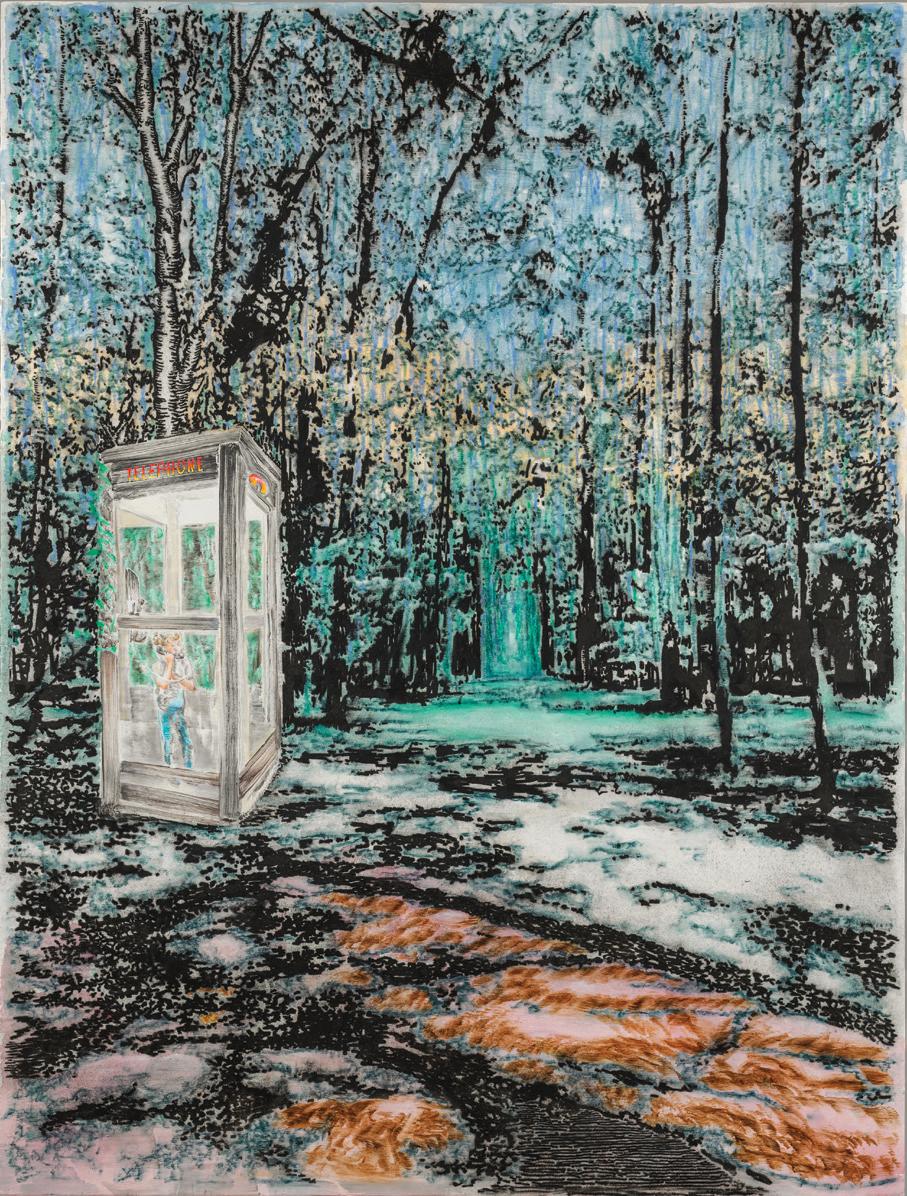

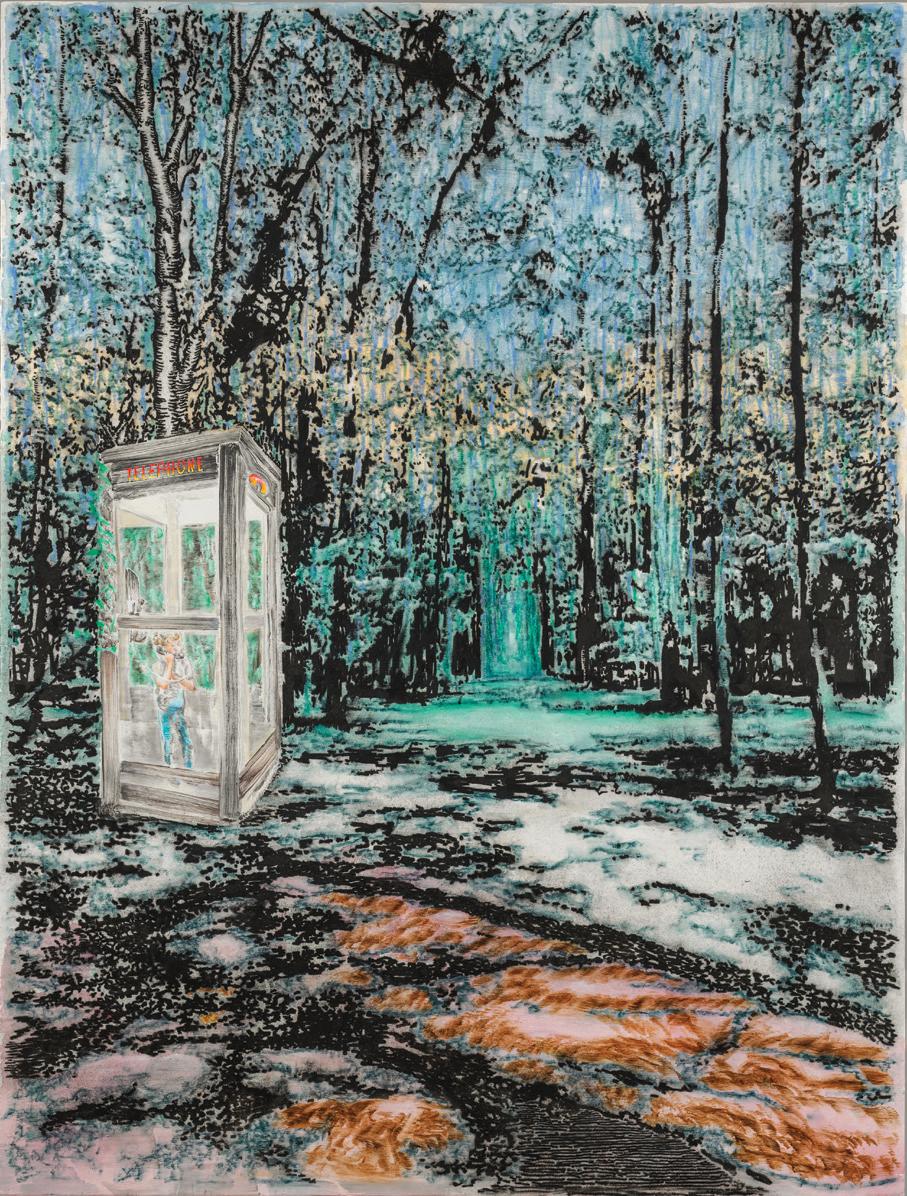

Swansea’s area code, 2019 shows a little boy alone inside a phone booth in a forest clearing. The phone booth is lit from inside, as if it were night time, while the blue sky suggests the sun is out. The time of day is ambiguous. The creeping black patterns on the forest floor indicate nighttime or late evening or melting patches of snow. This ambiguity about the time of day—one that you probably did not register—hints at disparate photographic sources that the artist loosely drew from to make this composition. Her process begins by perusing the more than 80,000 photographs she has taken and archived on her computer. She has been shooting with a digital camera since the late 1990s, though now mostly uses her iPhone. area code, 2019 mixes together a few of her photographic interests: the now antiquated but once ubiquitous phone booth, the dense deciduous forests of the eastern US, an abandoned NASCAR track in North Carolina, and her son, the child in the booth. As she shared recently, she starts by looking at photographs on the computer monitor and “stays in that world until it becomes clear to me what the image will be. Only then is it translated out

of the digital realm into the studio.” These photographs are not collaged together to make the painting. Instead, they are visual prompts that lead her to a rough composition in her head before she steps in front of the canvas.

Swansea starts digitally and ends working by hand. Others take the opposite route. Mazandi’s Nine began as clay thrown on a potter’s wheel that she then carved and fired. She calls them flowers, but they also resemble vertebrae, corals and the microscopic mineralized shells of diatoms. After firing, the ur-form of Nine was X-ray scanned. This digital file was enlarged. Then, an experimental machine that used pulverized stone bonded with a magnesium compound printed the file. As a final step, Mazandi brushed on a coating to heighten the nubby texture, as if Nine had been submerged in the ocean and coated with accretions barnacles. The sculpture is stone, albeit spit out from the nozzle of a printer, but resembles the mineral depositions of an arcane biological or geological process.

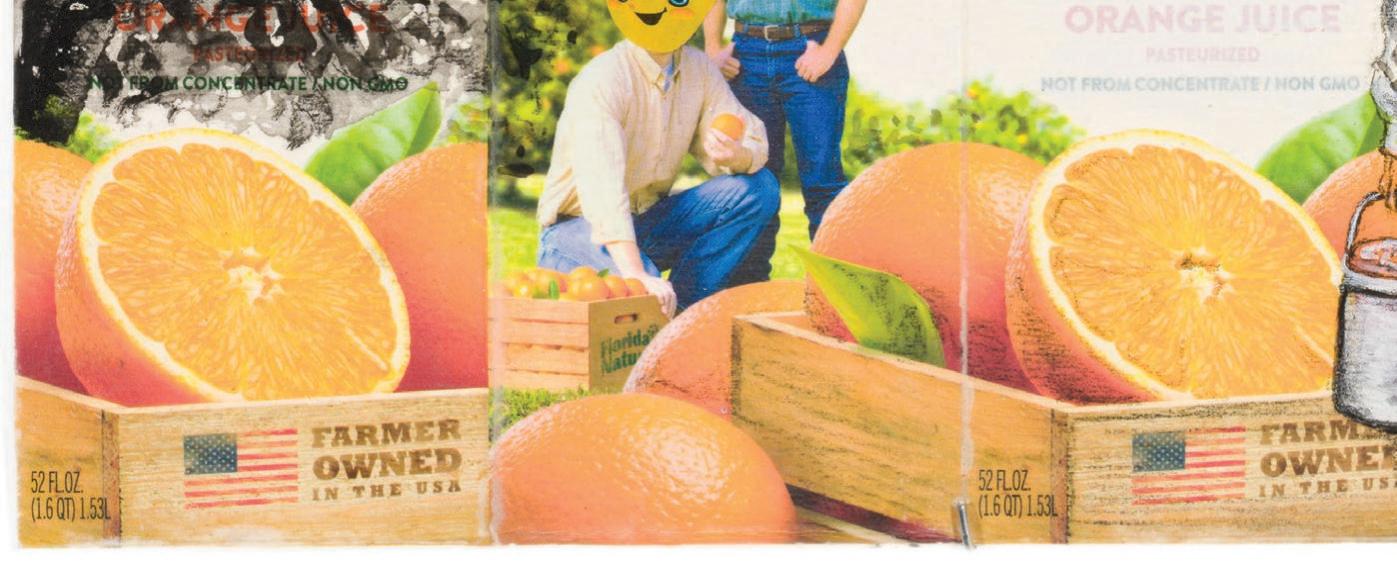

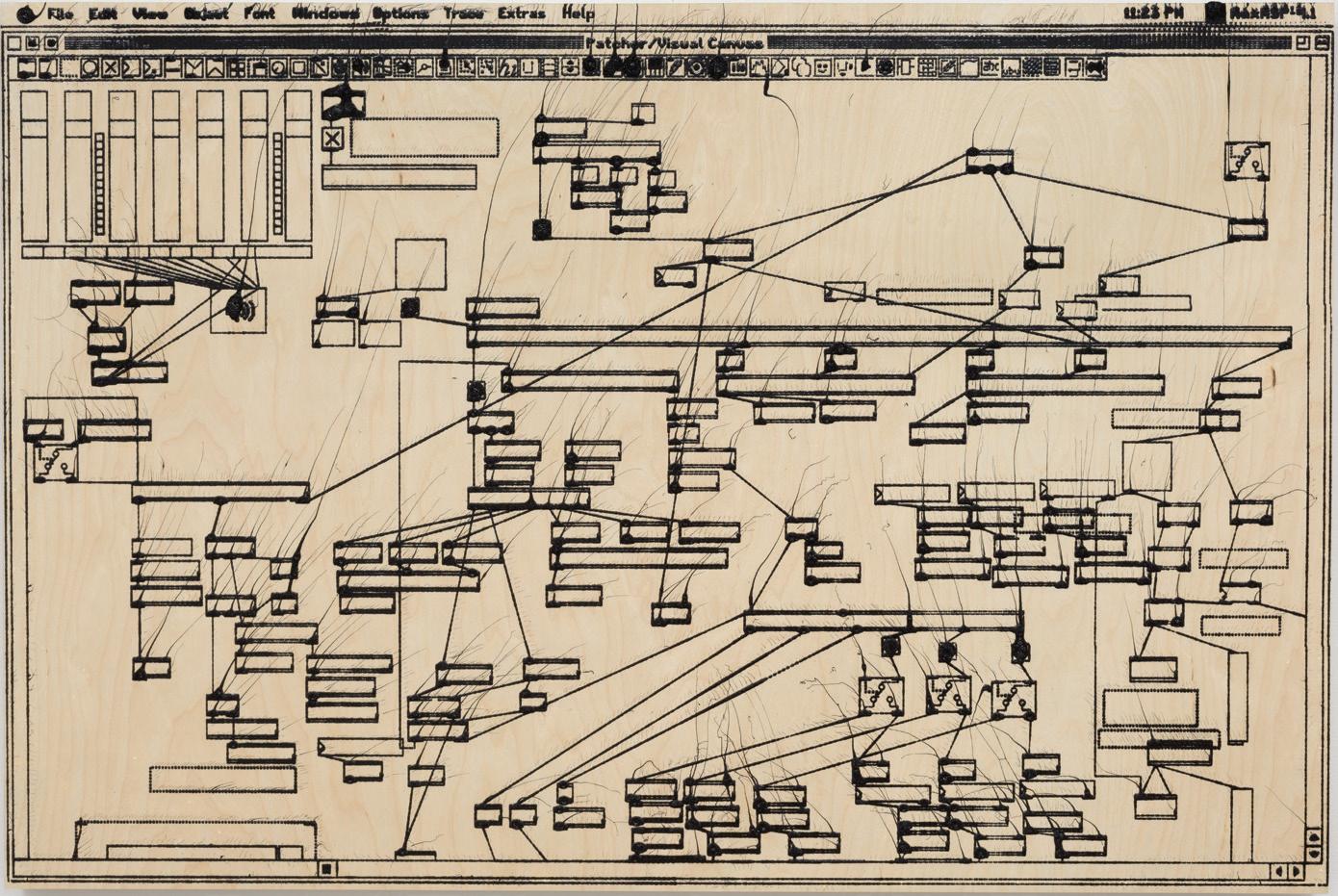

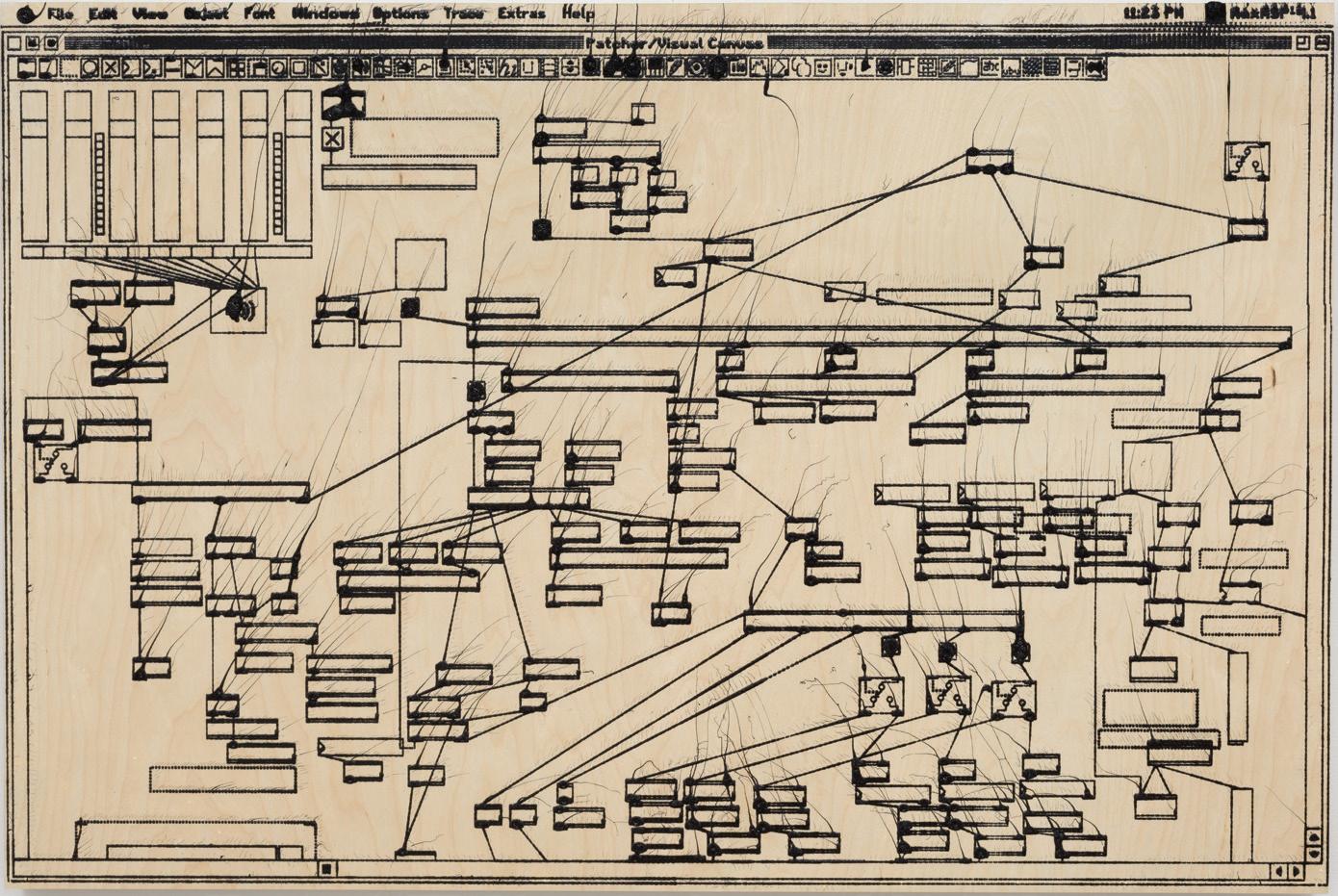

Saban’s concatenation of analog and digital in Pleated Ink (Music Synthesizer: Max/MSP, 1996) is not about the process of making an artwork, though she does sometimes mix approaches in her art marking by using laser cutters and digital printing. Instead, Pleated Ink is a picture of a computer screen running the music synthesizer program MAX/MSP (Mix signal processing). Released in 1996, the program used the innovative method of a Visual Programming Language, also called Block Coding. Rather than typing lines of commands, the user visually moved around blocks and connected parts together with lines to link together functions. This painting transforms the familiar experience of staring at a computer monitor with its bright clarity and crisp

Analia Saban, Pleated Ink (Music Synthesizer: Max/MSP, 1996), 2020, ink on panel, courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, NY/LA

24 LUMARTMAGAZINE

edges, a place beyond human touch and without dimensionality or texture, into a bumpy tactile surface. The wisps of ink are like pulls of taffy laying across the canvas. Their presence heightens the painting’s connection to a human person holding a tool to apply the ink and recalls the goopy unruliness of paints and inks.

Finally, Heydari’s Reterritorializaiton (2023) might be a decrepit greenhouse filled with trees and overgrown plants. The roof resembles a dropped ceiling found in bland corporate offices everywhere. This ceiling might or might not be glass. Water pours down in streams and puddles everywhere. Sheets of water obscure the background. A greenhouse, a gathering of people, lawn furniture, a paneled ceiling, overgrown plants, and maybe someone nude reclining next to a pond. These elements have the horrific quality of a nightmare in which only the dreamer knows something is amiss.

In an interview in ArteEast, Heydari said that his paintings’ illogic and disorientation—its blurs, perplexing subjects, ambiguous shapes—come from a need to pull apart the totalizing ideology of contemporary Iran, where he grew up before coming to the US to pursue an MFA.

As a member of the generation that emerged following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, I incorporate different modes of mark-making to reveal and deconstruct the binaries that have shaped my identity: East and West, body and soul, past and future.

The way that Reterritorializaiton holds together initially but ultimately crumbles offers a visual parable for how anyone might move away from the binaries of ideologies—and not just those from Heydari’s experience—to all the leaky and creaky and unsatisfactory confusion of the world in which we actually live. In an exchange with this author, Heydari called his paintings “autopsies of found images.” He said that “objects in the painting are stretched between two states, decaying material and unraveling gridlike systems.” The immediate object of the autopsy is the AI-generated image, which he manipulated and changed as he put brush to canvas. While this painting is proof that there is not a firm boundary between being made by hand and born digital, there is also a much bigger lesson to take away from this painting about being a critical thinker, about keeping your eyes open. Do the pieces support the edifice they are shoring up? Question. Look carefully. IRL is messy, confusing and full of real possibilities, if you stay open.

above: Ena Swansea, area code, 2019, (2019), oil and acrylic on linen, SBMA, museum purchase with funds provided by Kandy Budgor, Luria/Budgor Family Foundation

below: Yassi Mazandi, Nine, 2013, a unique Born-Porcelain TM work, geo-polymer bound Dolomitic stone, caseinbased coating, SBMA, gift of Beth Rudin Dewoody

SPRING 2024 25

Terremoto Christina McPhee

by Silvia Perea

“Shut up and look out the window!” Christina McPhee’s parents would urge their children while driving them around the US in the family’s car. Mile after mile of staring at the sierras and plains stretching across the country through the rear glass prompted McPhee’s avid imagination to picture them as an unexplored territory, flled with dormant truths yearning to be unearthed. Emphasizing this childhood fantasy were the lavish depictions of the American West by 19th-century such as Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Cole that McPhee recalls admiring at the Sheldon Museum of Art at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, not far from the village where she spent her formative years. Similarly infuential in shaping her childhood perception of the country’s hinterlands as a land of wonders was her foray into prairie habitats during solitary bike rides around her home.

Over time though, McPhee’s explorations of the plains, including burial sites and tipi rings, led her to grasp that the magnifcent images of the American landscape that she cherished did not align with the truths that such vast territory enfolded. This realization was also at odds with the beliefs prevalent in the conservative milieu of her upbringing, an environment that included several close relatives engaged in the evangelization of Indigenous people in the upper Midwest. McPhee recognized that the certainties presented by her elders were actually ambiguous and somewhat impervious. Conversations around the dinner table justifying the irrelevance of native communities based on their presumed low demographics, for example, didn’t make sense to her.

“As a teenager, I could not understand that a culture that had been there for thousands of years could be erased so simply, or that one could pretend that it had never existed.” Discussing topics like these at home was of-limits, just as the possibility of expressing feelings or thoughts as one’s own, so McPhee grew accustomed

to sharing her concerns obliquely. As she matured, the need to come to terms with her own thinking regarding the intricate liaison between the American landscape as a settler domain and its subjective realities became a pressing call, and McPhee ventured into the realm of the visual arts to respond to it. Yet, instead of adopting an explicit artistic language to voice her thoughts, McPhee continued—and continues to this day—to express herself indirectly, using a personal non-fgurative lexicon that expands the aesthetic and semantic dimensions of abstraction.

Together with greater expressive freedom, abstraction provides McPhee with a path to escape convention, a goal the artist pursues through the multiple media she masters: drawing, photography, collage, video art, performance and especially oil painting, for which she is best known. From this standpoint, abstraction also allows her to approach the subversive, yet elusive power of beauty. “Beauty is a tremendous deduction. It’s subversive because it’s constantly trying to move outside of normative standards. It’s always a little bit in drag. This wildness is the power of the beautiful,” she afrms. Furthermore, abstraction suits McPhee’s resistance to the paternalistic and sugarcoated undertones her now adult eye discerns in the settler colonial depictions of the American landscape. In this regard, abstraction stands, for her, as a tool for unrestricted engagement, comparable to the “informality” that Umberto Eco describes in Opera aperta (The Open Work): “a confguration of stimuli whose substantial indeterminacy allows for a number of possible readings.”

Perhaps more importantly, abstraction is a ftting way for McPhee to address diverse “resonance felds” across the sundry media she uses. These ‘felds’ encapsulate the motivations that drive her artistically, and usually symbolize a strained, or even traumatic, relationship

26 LUMARTMAGAZINE

SPRING 2024 27

Christina McPhee, Telluric Dreamtime, 2023, oil, oil stick, collage of ink on washi and printed text, and dye on canvas

Christina McPhee, Palm at the End of the Mind (Storm Surge) (after Wallace Stevens), 2023, oil, oil stick, ink, marker, and dye on canvas

between a natural site and its inhabitants. Such is the case, for example, of Red Springs, in Wisconsin, where her great-grandfather and grandfather taught Mohican children at a mission school during the frst years of the 20th century. In her recent painting, titled precisely with the name of the Shawano County town, McPhee ponders on the ethical implications of descending from a lineage deeply rooted in the assimilation of Indigenous peoples into Western cultural paradigms. Ripped fragments of photographs taken by her grandfather in 1906 featuring Mohican individuals, speckle the canvas, some buried under layers of paint, others crossed out with ink and colored pencil. Preserving the identity of those stripped of their original ethos from any exposure that might be perceived as lucrative is an ethical imperative as crucial for McPhee as safeguarding their story from oblivion. But what is this story? What does Red Springs mean? Can one truly comprehend the depth of what happened there or anywhere else with a similar human context? Along with representing the subject matters that drive her work, the concept of ‘resonance feld’ evokes a fickering, trembling surface that conceals such profound realities—an image the artist borrows from Brazilian psychoanalyst Suely Rolnik. Indeed, the resonance between the fathomable and unfathomable efects of colonialism on sectors of society and the environment centers McPhee’s intellectual approach to her artistic

output. “My work,” she acknowledges, “refects what it is like to be in the world today from an epistemological perspective. It operates at the edge of what we know and areas that we don’t fully understand.”

Visually speaking, McPhee’s felds of resonance transcend any evocative association with a geomorphological feature, embodying the reciprocal infuence between a tectonic substrate and its atmospheric canopy, to suit a comparison with a seismological event of signifcant proportions. In her paintings, in particular, energetic brushstrokes, scratches and doodles coalesce amid storms of color suggesting scenes in the process of disintegration. Juxtaposed and overlapped, layers of paint imbue her compositions with a topographic quality that evinces the inspiration they draw from natural landscapes. Rugged and shattered, these strata appear galvanized by telluric forces.

Beyond illustrating the crises of contemporary life, especially fueled by economic liberalism, the reigning chaos in McPhee’s canvases admits, at least, two interpretations. One, related to chaos’s turbulent appearance, hints at the artist’s yearning for the collapse of the system of values within which she was raised, a system that largely persists to this day. The jagged scribbles that populate her paintings mimic gestures of erasure, possibly refecting the artist’s rejection of colonial and canonical stipulations. From this standpoint, her work aligns with the concept of the right to opacity—the non-Western world’s right to resist the Western’s imposition of a hierarchical relationship with it, allowing the former to subvert such system of domination—advocated by the French writer from Martinique, Édouard Glissant. The other interpretation of chaos contemplates the word’s etymological origin: khaos, from Ancient Greek, vast chasm, void. In this sense, the turmoil pervading McPhee’s paintings alludes to the ongoing cultural depletion that ensues neocolonial and globalizing processes worldwide. Along the same lines, it evokes the contemporary widening of ideological schisms regarding the other and the environment.

Even though all of McPhee’s artistic practice “is about a place,” as she admits, these considerations elevate its signifcance to a global level. Indeed, places and their critical realities intermingle in her work, but the ripples created by the latter extend beyond any particular geographical context. Emphasizing that truths are relative, uncertain, and endure in non-fxed scenarios, McPhee’s art concretizes what Glissant calls “trembling thinking”: “The world trembles physiologically, the world trembles in its becoming, the world trembles in its pains, in its oppositions, in its massacres, in its genocides (...). The world trembles and our thinking must adapt to this trembling. We must try to follow these tremors and perhaps we will discover more truths than we do today.”

28 LUMARTMAGAZINE

Christina McPhee, Red Springs Orange Shirt Day, 2023, oil, oil stick, collage of watercolor drawing, collage of digitized photographs, and dye on canvas, all images courtesy of the artist

Where does copper come from Mayela Rodriguez

by Ricky Barajas

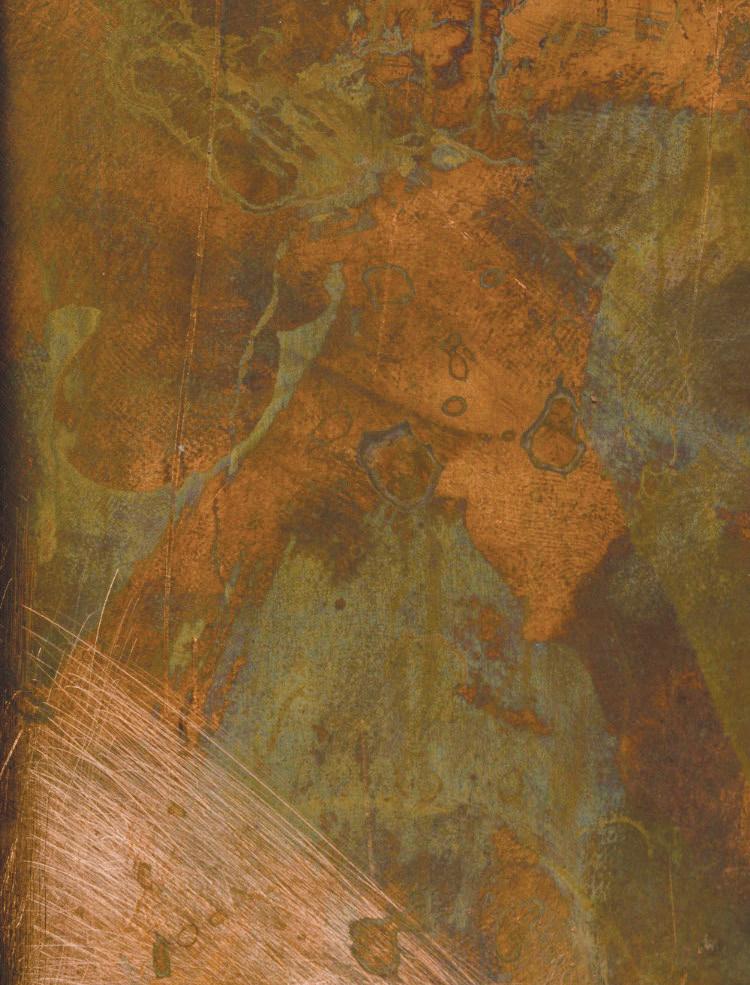

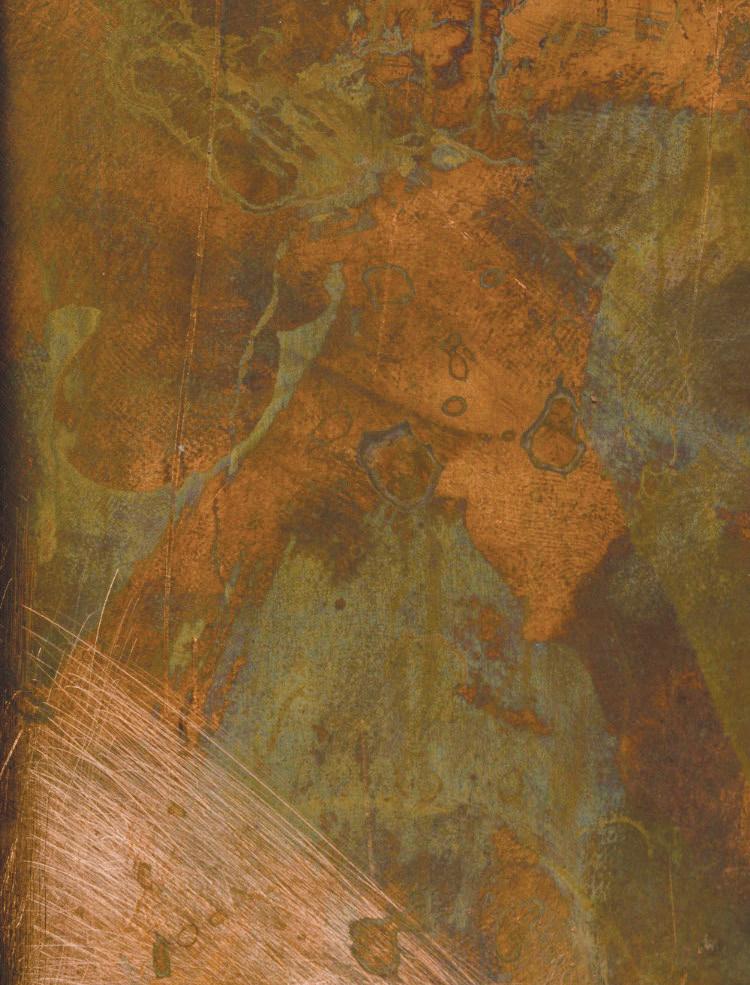

Something as rigid and heavy as copper does not often appear as the cornerstone of a conversation about movement, immigration and assimilation. But the connections that Mayela Rodriguez draws between the metal and her family show pieces of history lying just beneath the surface, ready to be excavated.

Presented by the Architectural Foundation of Santa Barbara, Rodriguez’s recent exhibition Veins: Mining Family History Through Copper explores her family’s mythology and history around the metal.

“I chose the name Veins because like veins of copper in a mine, we have veins with blood. These are channels of trying to fnd or understand my history,” Rodriguez says. Growing up, she heard stories about her grandfather and his brother pitching rocks into the open quarry at Buenavista del Cobre copper mine in Cananea, Sonora, Mexico. Her great-uncle, Aurelio Rodriguez, went from a childhood of throwing rocks to a professional career in baseball playing for the Detroit Tigers.

While she was a graduate student at the University of Michigan, through extensive correspondence with the mine manager, Rodriguez received a 13 x 18 inch copper slab for free. Initially, she planned to explore her family narrative by recreating her uncle’s baseball cards in metal. But when she held the copper in her

hands, the political implications of the material resonated with her, and her ideas began to shift. “I had to wonder why this mine is even considering me in this request,” Rodriguez says.

Copper holds a vital place in American infrastructure and culture. Electrical, telephone and plumbing systems need copper to function efciently, using it for their paths, connections and routes. Copper also comprises the Statue of Liberty, a declaration to the world that all are welcome in this land, and pennies, featuring the depiction of President Abraham Lincoln, best known for ending chattel slavery in the US. Unfortunately, what symbols represent and the practices that people adopt in their name often deviate in ways that hold them in contention with each other. While the Statue of Liberty welcomes immigrants from the European continent, her torch does not light the same path for people from Mexico and South and Central America. This led Rodriguez to consider the symbolism of the copper and the concept of a “good” or a “useful” immigrant.

“I wanted a literal transformation,” she says. “This slab was profoundly boring at frst, but then I began to consider the time and labor that went into mining, melting, molding, and shipping this slab. I thought, ‘I can’t change this copper. It’s already been pulled from the earth and formed into an unnatural shape, and then sent across the border. It had to become something good enough to cross the border.'”

Inspired by the performance of existing with the slab, Rodriguez began to travel with it to diferent locations which her family once considered home. She was interested in how these actions change it and how handling the copper causes new colors and patterns to form on it from factors such as the oils on her fngers to exposure to the air. She even took the copper slab with her

to a therapy appointment. “How do these actions change it?” Rodriguez asks. Though it holds the focal point of the exhibition, the copper slab was not exhibited. Instead, she displays scans and other images, including photos taken during all of Rodriguez and the copper’s travels.

“My viewers never get to see the copper, and in that way it becomes a myth. Just like my family members, it will be present in other ways,” she says. “I want viewers to take into consideration the myths and stories that have passed along. A lot of families have things like heirlooms and other objects that have these stories attached to them. I also want viewers to witness what I’m going through.”

In one version of these scans, the copper will be presented in a series of four foot curtains. The curtains are able to move and fow in ways that rigid metal cannot, and with each layer they create a looming, haunting efect that emphasizes the weight of family history.

A version of this story was originally published in VOICE Magazine

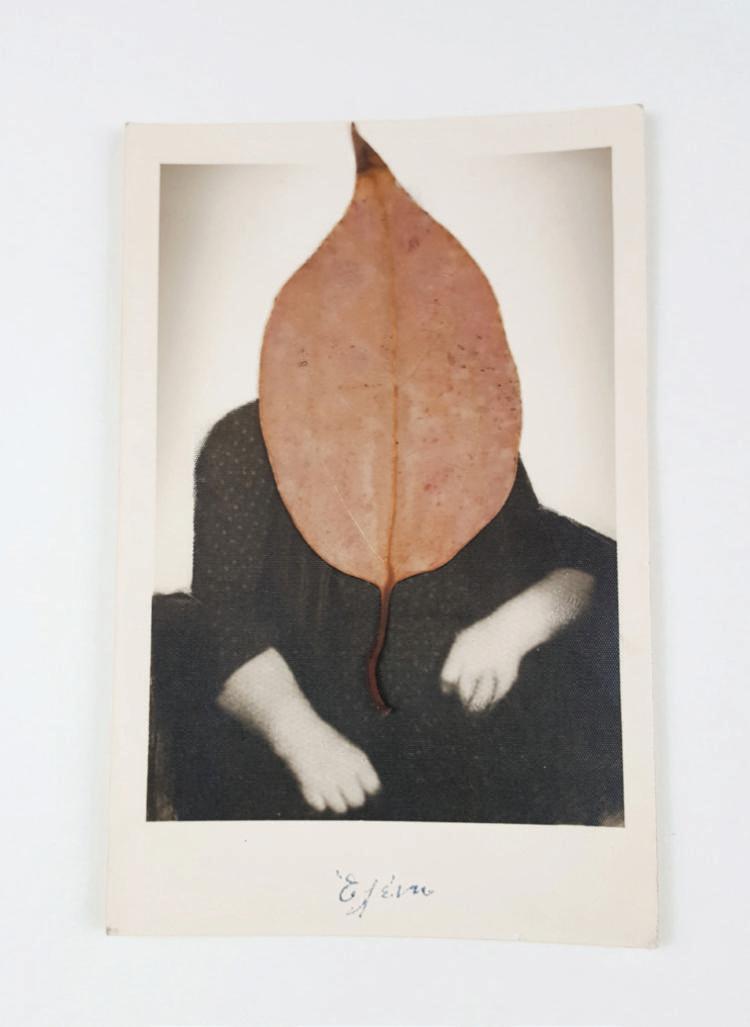

Mayela Rodriguez, Copper, detail; Metaled Ghosts (inset)

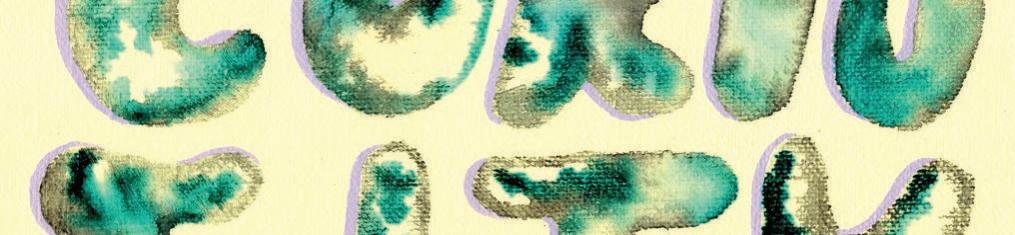

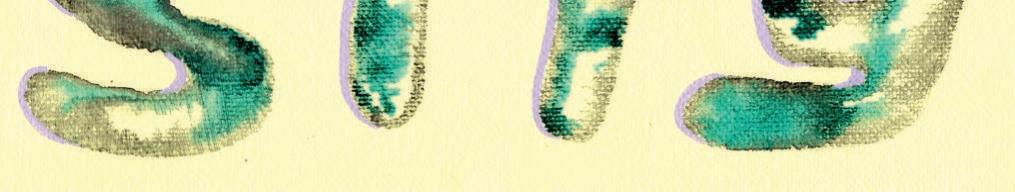

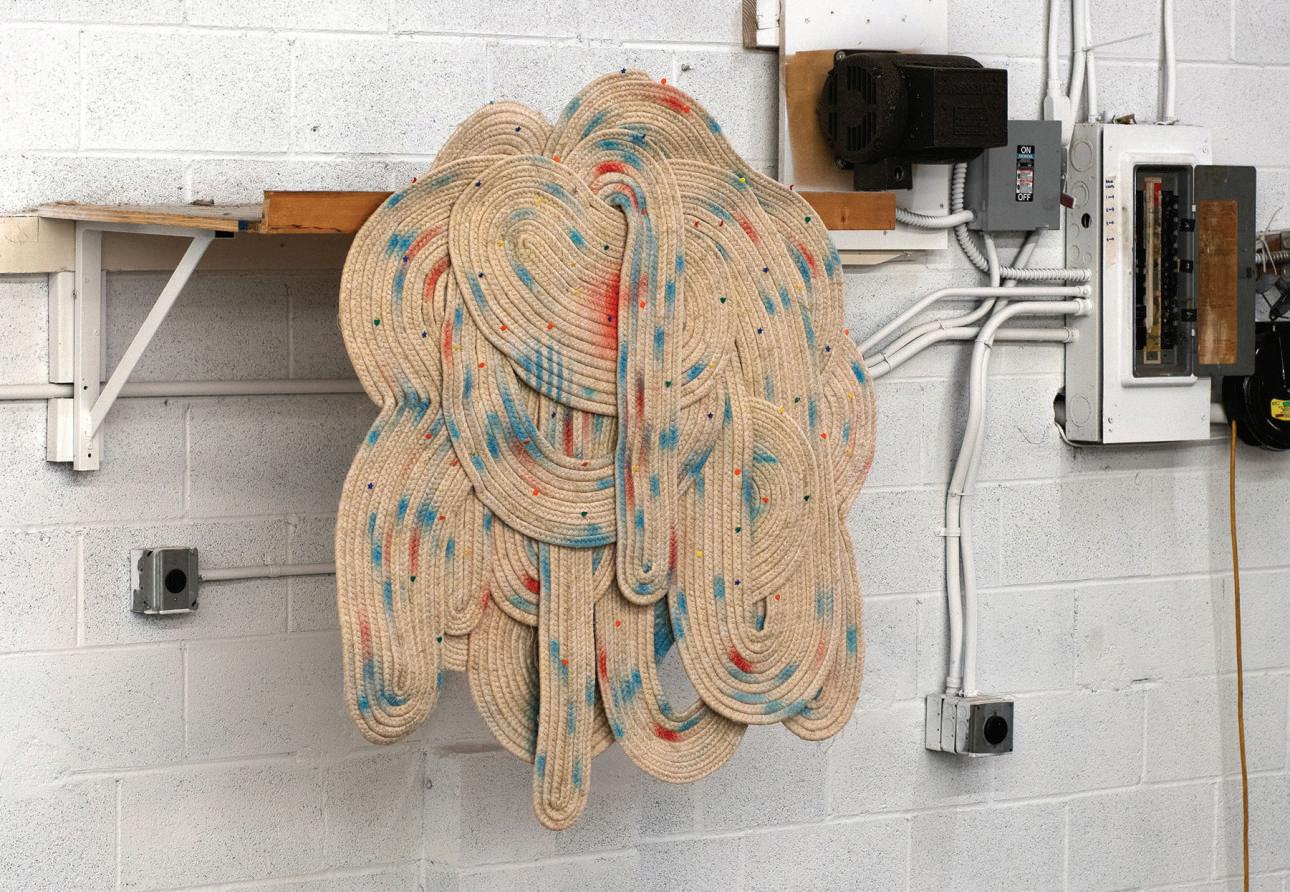

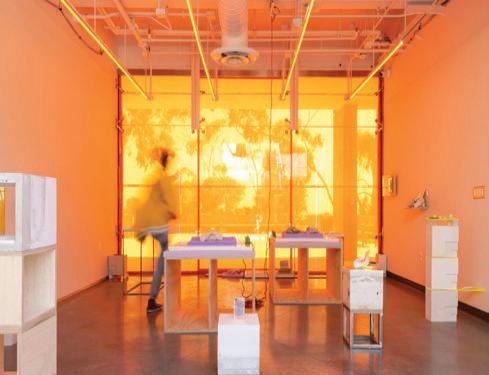

Glitches & glitter

Evelyn Contreras

by Sarah Cunningham

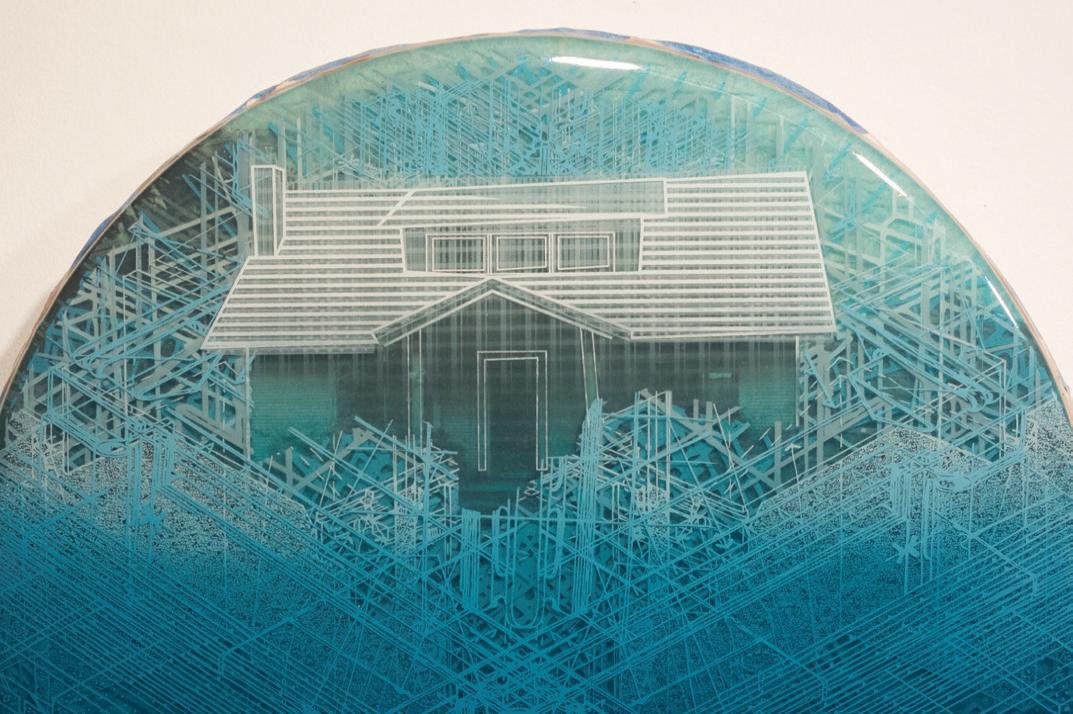

While in graduate school in Texas, Californiaborn artist Evelyn Contreras studied the human-made landscape of her home state via the lens of the Internet. Then, when the COVID-19 pandemic limited her ability to travel back to Texas for a residency at the Rockport Center for the Arts, she reversed the direction of her digital gaze to Rockport’s post-Hurricane Harvey streetscapes from her desk in Santa Barbara. This virtual sojourn culminated in works featured at the Atkinson Gallery, Santa Barbara City College in 2022.

Rockport Case Study .03 is an acidic orange gif made from an image of a mid-century home destroyed by the hurricane. In it, the fractured house glitches in and out of solid form, resembling a fnal transmission from our post-apocalyptic Earth. The vibrating monochromatic still of the vacant home cleaved down the middle is haunting, reminiscent of Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting (1974), which depicts the human-made landscape, now post-human, with similar despair. Still, rather than document a poetic spatial intervention exposing the

failure of societal constructions as Matta-Clark did, Contreras uses found digital imagery to explore the inherently cannibalistic devastation of the Anthropocene while critiquing the contradiction of her own obsessive doom scrolling for so-called “ruin porn” from the safety of her chair. As Legacy Russell wrote in her Glitch Feminist Manifesto, “This glitch is a correction to the ‘machine,’ and, in turn, a positive departure.”

Contreras’ Rockport Case Study gifs are an extension of her printmaking, infnitely replicated and looped. On the other hand, her fipbooks, made of cyclical snippets, shift from 80-frames in digital format to the 24-frames of the analog object, creating fdelity and information loss. Here, in these illusory toys, printmaking devolves from exact copy to weak simulacrum. The box holding the book and the glowing backlight both reference the elusive display screen. But then again, to fully view each fipbook, the viewer must actively participate by rotating a knob.

Flipbook series contains vibrantly colored, graphically patterned environments with shimmering surfaces and interactive objects. They simultaneously read as glossy retail shelves and carnival sideshows, each with a potentially false, yet seductive, secret within. For Contreras, her meticulously designed and machined pieces made of wood, mirror, vinyl and auto paint are an homage to her Chicano culture, especially the carefully crafted shapes and lustrous veneers of lowrider cars. As they are replicable CAD-designed wood, acrylic and vinyl pieces, she also views her full installations as prints. She embraces reproducible art, in part, because it is easily accessible like other widely available vernacular art forms. Like her lowrider counterparts, Contreras is a technician whose work can astonish and distract viewers from the dystopian landscape of their own creation.

Yet, while her work is skillfully machined and spraypainted to glimmer like the work of her forebears,

30 LUMARTMAGAZINE

Evelyn Contreras, Through the Looking Glass, detail

she eschews Chicano art’s established iconography in favor of disjointed buildings in unpopulated humanmade landscapes. While often depicting the exterior of houses, her work cannot be understood as a celebratory illustration of the domestic sphere. It is especially interesting to view her work via artist and critic Amalia Mesa-Bains’ feminist reinterpretation of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto’s concept of rasquachismo (a working class make-do sensibility) in Chicano art. In Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquache, Mesa-Bains says, “Critical to the strategy of domesticana is the quality of paradox. Moving past the fxation of a domineering patriarchal language, our domesticana is an emancipatory gesture of representational space and personal pose.” While Mesa-Bains employs a distinctly Chicana visual lexicon in her artwork, Contreras adapts her concepts of paradox to the literal representation of architectural space, examining the outer structure of our (societal) house.

Her Viewfnder series incorporates rhinestones, another refective surface often used in Chicano artmaking, but also associated with feminine representations. Resisting an art school admonishment that, “glitter

does not belong in art,” Contreras thoroughly bedazzled the faces of fve classic view-fnding toys with gleaming aquamarine stones. Inside, gifs of the crumbling human landscape ficker in and out on a loop. Her interest in paradox manifests between what is seen and not seen.

In another paradox, Contreras jokingly describes herself as “a stunted sculptor working planarly.” The tension between fat prints and three-dimensional objects is most evident in Suspension, a mash-up of shiny silver dodecahedron and a Rorschach test. It is a metaphor for the way viewers attempt to construct meaning from images they cannot decipher. At the center, is a gif, an obfuscated, kaleidoscope of refracting images of hurricane-destroyed homes from Rockport.

As in the work of other speculative futurists, Contreras depicts a prismatic gap of potential opened by the technological glitch of our present dystopian world. Through this crack, we get just a glimpse of a more physically present and more resplendently beautiful future.

SPRING 2024 31

Evelyn Contreras, installation photos, Atkinson Gallery, SBCC

32 LUMARTMAGAZINE

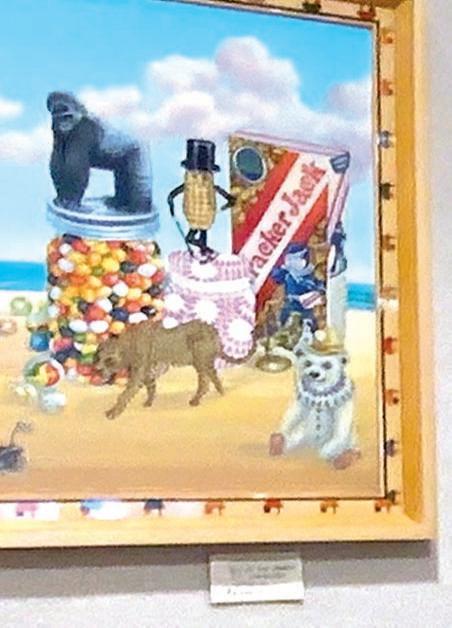

Anna May Wong, Daughter of Shanghai, 1937, flm still

Love me, love me not Anna May Wong

by Debra Herrick

When the US Mint in 2022 released its Anna May Wong quarter, the ffth coin in the American Women Quarters Program, female Asian American representation got a boost. The following year, it had a pop culture moment when Mattel released the Anna May Wong Barbie, wearing a red dragon dress, in its Inspiring Women series. But who is Anna May Wong and what made her an icon?

Born in a Chinese laundry in turn-of-the-century Los Angeles, Wong rose to become Old Hollywood’s most famous Chinese American actor. Her performances captivated global audiences, but Wong faced serious challenges in an industry plagued by racism and sexism.

“America falls in love with Anna May Wong, but that romance is taboo and there are real costs that come from Anna May wanting to have and hold onto this love,” says Yunte Huang, whose biography on Wong draws from hundreds of her letters and other records. His portrait ofers new insight into her rare talent and ambition as well as the historical milieu in which she lived. “After all, she lived at a time when a Chinese actor would be deemed ‘too Chinese’ to play such a role—a cultural absurdity plaguing both Hollywood and Main Street USA,” Huang writes.

Her signature bangs, almond eyes and “willowy fgure wrapped in a silky qipao (cheongsam),” as Huang writes, are mainstays of her iconic image. In 1938, she was immortalized on the cover of Look magazine with the headline, “The World’s Most Beautiful Chinese Girl.”

But Wong’s story is not just about glamor and fame. Huang, a poet, Guggenheim Fellow and a distinguished professor of English at UC Santa Barbara, traces her journey from Weimar Berlin to decadent, pre-war Shanghai, and captures American flm in its infancy. Along the way, Wong encounters other remarkable people, including the philosopher Walter Benjamin and the actor Marlene Dietrich.

Daughter of the Dragon: Anna May Wong’s Rendezvous with American History (Liveright, 2023) is Huang’s third book in a trilogy of Asian American icons, including books on Siamese twins Chang and Eng and on Charlie Chan, both of which were National Book Critics Circle Award fnalists. It has taken Huang 15 years to complete this series, telling what he describes as the epic journey of Asian Americans in the nation’s tumultuous history.

“There was so much in that context that we can’t understand, but what we do see is that her iconicity survived decades,” says flmmaker Celine Parreñas Shimizu,

SPRING 2024 33

distinguished professor of flm and digital media at UC Santa Cruz, during a conversation with Huang at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Iconicity, she goes on to explain, is a term of reverence, used for a person who achieves so much in their lifetime that they attain “a kind of godlike status where we worship them because of what they were able to achieve.”

In her lifetime (1905–1961), Wong performed in 60 flms, including the very frst movie made in Technicolor. But in the decades since her death, she has been the topic of biographies, novels, flms, TV series, magazine articles, videos and publications from flm, media, literature, feminist and Asian American studies.

Today, we would call her a maximalist. She was known for having the longest nails in Hollywood, author Anne Anlin Cheng writes in Ornamentalism. “This was not fake. She cultivated these nails. Every time she took on a job, she was like, ‘Do I have to cut my nails?’” says Parreñas Shimizu. But, at the same time, she notes, Wong also had risque costumes and other accoutrements of racial femininity, “deploying her heritage in this way.”

In her letters, Huang fnds evidence that Wong knew what she was doing, sometimes telling friends, for instance, that she had to sacrifce her nails for a character, such as for Daughter of Shanghai, in which the director made her cut her nails for the part of a doctor. Huang relates the control over Wong’s body to what he’s learned from the Chinese community about sufering. “Speaking of female beauty and pain, nothing is more torturous and painful than having your feet bound for the pleasure of the male gaze,” says Huang, whose grandmother had bound feet. “I came to Anna May Wong’s story through these personal, historical and cultural understandings and experiences.” Despite everything, Wong achieved “a glamorous splendor.” But she set her bar higher than most. She defed fashion conventions and set new trends. But she faced real material constraints in what she could and couldn’t do — cultural, political, even legal barriers. The motion picture industry’s Hays Code, laws and policies from the Chinese Exclusion Act and additional laws prohibiting interracial relationships stifed her career (she couldn’t play a romantic lead with a white counterpart) and love life (she could be arrested!). She was most likely queer (also considered deviant and illegal at the time) and Dietrich and actor Dolores del Río were rumored among her lovers. “I have very little social life — am very lonely,” she sighs in a 1924 interview with the South China Morning Post

She signed her headshots, “Orientally yours.” Was she being demure or defant? Or was she saying, “I’m bound by this racial feminization so I’m going to put it in your face,” as Parreñas Shimizu suggests. “And she also was so skilled at critiquing the parts she had to play. In the book by Cheng, she basically says, ‘The injury of Anna May Wong is aestheticized into such beauty.’

“Isn’t that crazy?” Parreñas Shimizu says to Huang and everyone listening. “Your injury is aestheticized? Your harm is represented as a pleasure for viewers? How painful that people enjoy inficting your dehumanization on screen.”

But the humiliation wasn’t just on screen. Wong traveled the world—Berlin, Paris, London, China, the Philippines— and ushered in a new brand of global cosmopolitanism. But she wielded an uncommon status because of her celebrity, one that couldn’t protect her from being pulled away from her travel companions at a train stop on the Canada border. There, she was made to travel hundreds of miles alone to cross the border at a designated Chinese entry point.

“I think it’s one thing people don’t understand,” Huang says. “When you struggle to cross borders, the trauma—the haunting nightmare—that fear haunts you throughout your life. No matter what paper you carry, the wall is always there.”

Originally from China, Huang speaks here with insight from his own experience, which he does in all his biographies. “He has written a quartet of Asian American biographies if we include his own peripatetic life story, exquisitely and often humorously woven into the histories of these iconic Asian Americans,” suggests Constance Penley, professor of flm and media studies at UCSB. It’s a “contemplative mode” of writing, says Huang in an interview for this article. He frst learned it in the Poetics Program at SUNYBufalo, where he completed his doctorate, from an anthropologist trained in Zuni narrative. “Every story comes with a telling,” he says. “You have the content but there needs to be a storyteller. There’s a scene of telling: Who told that story? So it’s not just the information like, ‘Anna May Wong was denied entry at a club in Shanghai.’ Yes, fne. But how do we know that? How did we get to this?”

Still there’s at least one more layer. Huang became a writer because he had a brother. His father wanted to be a writer but couldn’t be one. Instead he became a doctor, like his father, and his father before him. As a father himself, he obligated one son to become a doctor and encouraged the other, Huang, to study English. History matters, too. Growing up in China, where the Chinese government controlled all media, infuenced Huang’s understanding of narrative truth. English, he says, he learned from Voice of America.