Lauren Ishikawa*

Isabella Chiu*

Katsumi Sterling

Ryan Yau**

Seneca Schwartz

Maddi Chun*

Prerna Sharma

Ava Sparico

Ayesheh Jasdanwalla

Arushi Jacob**

Belle Tan*

Therese Labordo*

Thomas Lin

Lily Farr**

Marieska Luzada

Lauren Ishikawa

Editorial

Anna Brenner*

Meggy Grosfeld*

Lily Farr**

Arushi Jacob**

Ryan Yau**

Vince Kunawicz**

Naomi Ash*

Carys Hirawady*

Hailey Bochette

Jennifer Chan

Vince Kunawicz**

Kiyomi Casey

Atreyi Roy

* = manager ** = multiple depts.

Aiya

Gail Andersen

Jennifer Chan

Phoebe Chan

Ning Chen

Isabella Chiu

Lily Farr

Carys Hirawady

Sophia Lam

Zoe Leonard

Prerna Sharma

Ryn Yi

Thursdays were the days I was always looking forward to in my freshman year at Emerson. 8PM at the Cultural Center in 172 Tremont was always the weekly meeting time for ASIA (Asian Students in Alliance).

Going to predominantly-white institutions for most of my life, I had a hard time finding a community of folks who look like me and who shared similar experiences as me. When I went to my first ASIA meeting, the first meeting of the school year, I was flabbergasted with how many Asians there were in that one room. I’ve gotten to know and connect with so many folks through ASIA and the space it holds for Asians at Emerson, and I couldn’t be more grateful.

“Ties That Bind” celebrates the sentiments that people like me experience when entering safe spaces such as ASIA. We carry the strength and resilience of those that came before us, and the word “community” encompasses everything that we value. Not only do we hold these bonds close to us, but they also help shape our own identities. Being a part of spaces such as ASIA has allowed me to lean into discomfort, to develop my own relationship to my Filipino identity, and to take up space when Asians historically have been told “no” or “not now.”

at Emerson, and for your grace, kindness, and generosity. With that, I would like to extend a huge thank you to the ASIA E-Boards that have come before us for fostering a safe space for Asians at Emerson for the past thirty (yes, thirty!) years.

Thank you to the staff at Lunchbox for your continuous hard work and diligence, and for being a part of the biggest project of my life. Huge thank you to my co-director Lauren from the moment you joined us since the beginnings of Lunchbox, I’ve always been in such awe of your creativity, ambition, and drive. Thank you for keeping me grounded this semester and for standing alongside me you are going to be so incredible, and I can’t wait to see what the future of Lunchbox holds under your leadership.

To Jo, fellow Lunchbox co-founder, my eternal dance partner, and dear friend look at what we have built! Who knew that being pen pals and writing letters from opposite coasts would lead us here? Thank you for being with me as we hit the ground running with Emerson’s first and only publication dedicated to Asian stories none of this would have been possible without you.

Please enjoy the stories of “Ties That Bind.” And thank you for sharing this space with me.

- Marieska Luzada

- Marieska Luzada

Sincemoving away from my home in Hawai‘i, I’ve gained a much greater appreciation for the rich and intensely connected culture of the place in which I grew up. During these past two years I’ve been away from home, the ASIA and Lunchbox community have inspired me to revive a connection to my family’s culture. Through Lunchbox, I have also developed several ties with members of the Asian student community here at Emerson.

This issue’s theme is one that has felt especially resonant to me as “Ties That Bind” is all about immersing oneself with the traditions and stories of one’s culture. Moving away from home has reminded me of how important it is to remember one’s culture. It has always been something I’ve taken for granted, but now being in a place so different from my home, I’ve appreciated every opportunity I have to connect with the traditions and stories I grew up with. I am especially grateful for the opportunities I’ve had to connect with other Asian students here at Emerson. The ties I’ve made here have presented so many opportunities to learn about different cultures and more about my own.

I feel strongly that these ties are what makes our community at Emerson so special. It has been an honor to co-direct this issue alongside Marieska. I’ve been so fortunate to learn from and work with Marieska and Jo over the past couple of years and I feel so grateful to be able to continue this beautiful publication they have created.

It has been truly inspiring to work with the incredibly talented Lunchbox team, especially with my former design co-manager Hannah who has inspired me and taught me so much during our time working together for Lunchbox.

The stories in “Ties That Bind” are so incredibly beautiful and inspiring. I hope that you enjoy these artists’ work just as much as I have.

- Lauren Ishikawa

Sophia Lam

Yue. Lee. Chan.

Jennifer Chan

Gail Andersen

Isabella Chiu

Ryn Yi

Carys Hirawady

Aiya

Ning Chen

Prerna Sharma

Zoe Leonard

Lily Farr

Phoebe Chan

Vince Kunawicz, Katelyn Reddy, Hailey

Bochette, Grace Lee, Kiyomi Casey, Jennifer Chan, Naomi Ash

By Sophia Lam

By Sophia Lam

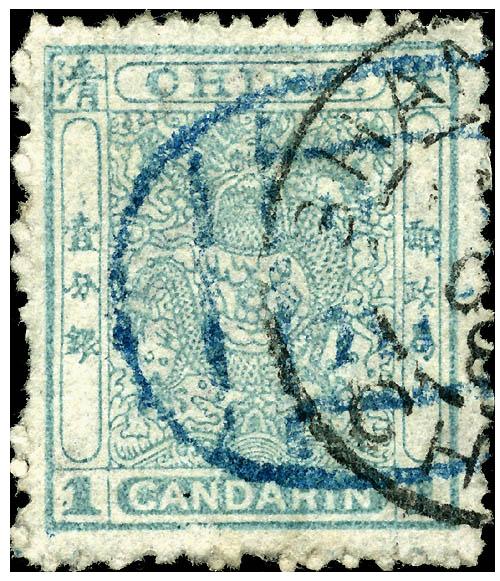

heritage? a legacy? a culture? boundaries of walls drawn to the unity of you a culture through colors of the future and past. through colors— the connections of being in tune with cultural harmony with floods that occur a dragon who flies is a dragon who controls and conquers red. the term that can hold power within someone the red envelopes that hold the wealth and good i cannot be lucky, i’m not wearing red, they said. the string that tightens those takeout bags getting strained to a point

it looks no longer in raw form it’s tied around the goods for the family the seeing of no evil or bad thoughts the seeing of only good within you need to wear red, for good luck she said. my dress was full of red and gold for the new yearsstrapping against my body but portraying the luck and fortune for the newcoming

i see him i see the tail and back of red and yellow only his body full of spikes he is flying away into the moon seeing me from below in the black he is holding the envelopes, he is holding the good news of the night the wealthiest dragon in sight having the highest power within the tightest of his grip green. to be healed or to not be healed

the luck of the jade has brought for me the sadness yet clarity it saw. the years of great freedom and healing.

i see him in the field, jumping up and down the earth’s surfaces of lush he flies away, he says he is going to come back later the necklace on his neck wrapping the healing he needs to get home

we don’t talk to them anymoreshe gave me that jade. it broke during a speech in class the fear that the healing i gained would flee like her.

the happiness in his eyes as he takes off away from the green white. the innocence is seen as this power that hides within the color that is so light dressed in white dresses and

white flowers as a young kid she tries on a dress for her family, its too white she says jokingly. im not pure enough. portraying a young innocent and pure soul within the cleanliness of the colors, the feeling of above rather than below oh, are you getting married? they ask. black. the authority of the pain of death why are you wearing black? they ask the evil within the colors that hidden aspect of one’s disappearance he flies away past the black to the yellow of the land in between he disappears

are you still pure? they ask you as you are wearing white and black the smell of incense- and foodand flowers the tones of blacks forming in lines as respect was taking as a family or alone if you came alone the black and white for power and royalty the angles of are you pure or not? will you ever be pure the constant strain of the family lines brings you further in the practices entering this colorful world that became a massive percentage of greys, blacks, and whitesit had brought clarity and balance to how i saw my race and culture the only black at funerals never more never lessthe dress coding never became

more prominent towards your personal lifestyle

the phrases of anyone being engrained in your head to learn or fight towards i remember first learning about the meanings of these how it all had these hidden symbolisms that showed deeper reasoning in terms of bringing more within the chinese cultural harmonythe colors of the clothes i wore during my years at chinese school being educated by the language but also the color coordination in terms of my conformity within my culture

the end had not been the end i was just the start of a new balance that you had to scale upon when you think the scale is equal a sickness that had bound the world had secluded you and who you are in a dark rain cloud of faults of this coloring book of a society

By JJ Chan

By JJ Chan

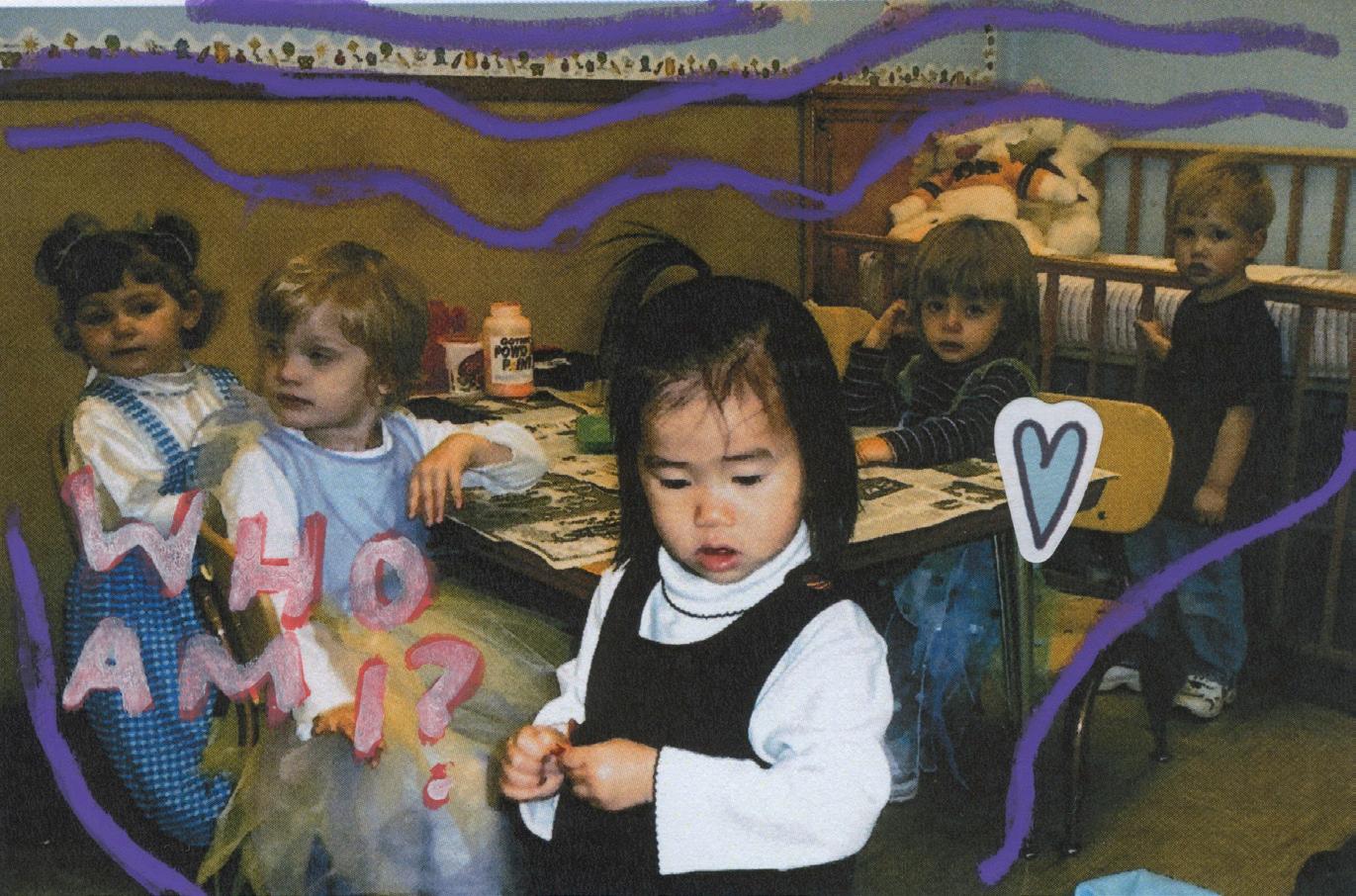

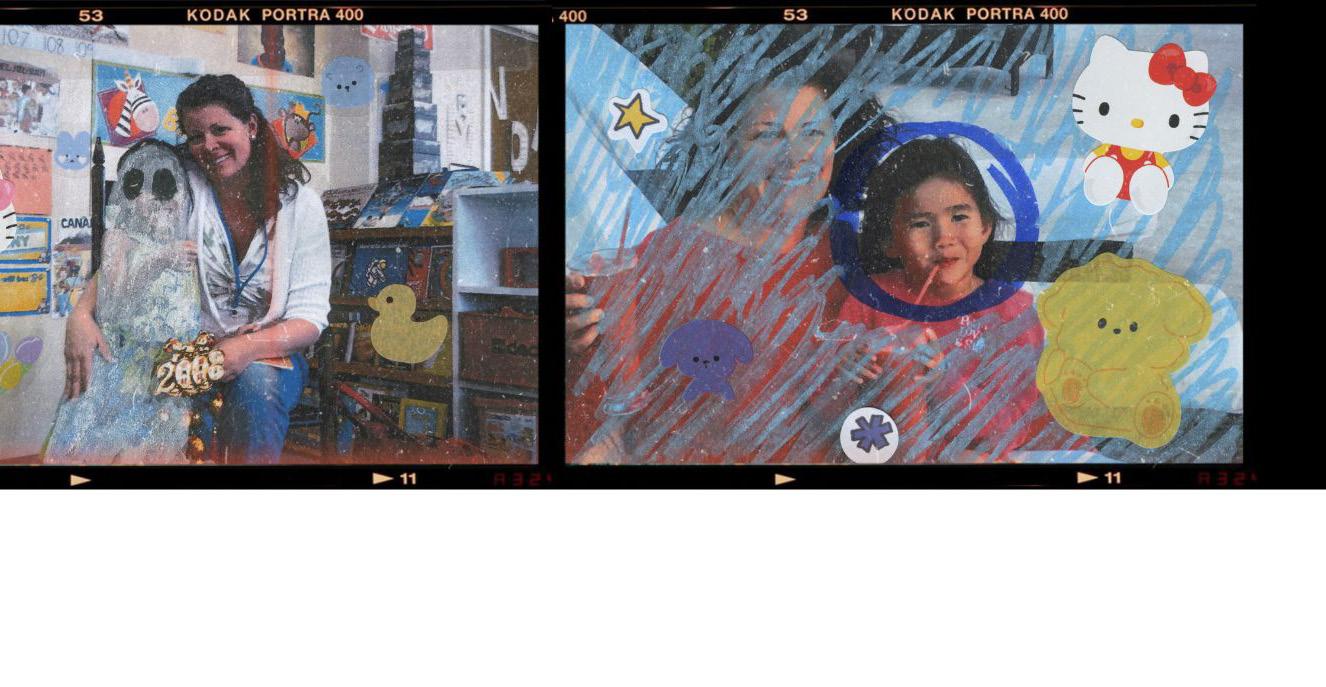

[Disclaimer]: Some of this content and information might be sensitive to some readers. Before I go into my experience as an Asian adoptee, I first want to say that everyone’s lives are dif erent. My life and my feelings on my adoption is entirely my own personal opinion and based on my particular background. And I acknowledge that all adoptees have dif erent points of view. This article is based on my experience and my perspective as well as a handful of anonymous interviewees that have agreed to share with me parts of their lives. When writing this article, I thought that it would be a valuable addition to my writing if I interviewed other adoptees and gathered quotes to back up my article. I was able to contact a few dif erent respondents on an online forum based specifically around Asian adoptees. I got a lot of great feedback and many respondents shared with me some of their adoption stories as well as their history with racism, white saviorism, and microaggressions. All contributors preferred to be credited as anonymous except for one of my cousins who I also interviewed, but they would prefer to be unnamed still.

“First gen or multi racial families it is a common thing to think youre not identiy enough. I think especially if you have a disconnect to how your family grew up. . . there is always going to be the sense of loss like you don’t get to experience things the same way that they did’.’

- Anonymous

As a queer, non-binary Asian adoptee, I have ties to both my personal heritage, as well as the family that adopted me. However, even when presented with two different ties, they go in two separate directions, thus I feel like I have none at all. I was adopted from Nanning, China at 14 months old. According to the orphanage, I was found

outside in a park at dawn, unsure about how long I was there. There was no information about me when I was found. There was no indication about who my parents could have been, their social status, or their reasoning for giving me up. I didn’t learn about this until later in life, but the orphanage that I was held in until I was adopted was lacking in a lot of places. There were not enough resources to go around, lack of food etc. I also was a child that was known for “behavioral problems” since I was extremely sensitive and cried a lot (even though that is very normal for babies). Those “behavioral problems” resulted in mistreatment and lack of consistent care like the other children received, including consistent meals.

The travel and adoption agencies did not prepare my family for an easy trip to China in 2003 during the SARS epidemic. But they were determined to adopt me and they made the risky trip and made it on one of the last planes leaving China. There was a lot of risk that went into their travel, and they barely were about to make it out of China back to the U.S in time. But that risk could have led to a lot of guilt that went into my upbringing. Sometimes I would find myself questioning if their work to get me and raise me was worth it. I feel as if everything I did was not enough to make up for what they did for me. Some might call that the result of white saviorism. Others might call it general adoption trauma, especially if they were adopted not by white people. But since I was adopted by two much older, very religious, and somewhat conservative parents, I felt as if there was nothing I could do to satisfy them, or to be what they wanted me to be. I feel like I could never live up to their expectations.

“Theadoptionprocessforanyonewhoispoc,experience white saviorism ‘oh my god you were so lucky’ ‘you have such a good life here’ seeing white people as saviors of things not associated with white things.”

- Anonymous

“My Adoptive Parents used their religion, Christianity, to tell me that I should be grateful I was ‘saved’ from a worse fateandthattheypaidalotofmoneyforbothmyadoption/ surgeries in America. That was the common story especially if I “complained” about any type of pain unrelated to my adoption. I experienced deprivation in regards to my physical and emotional needs.”

- Anonymous

Though I do not remember much of my childhood, I know for a fact that transitioning from Nanning, China to Los Angeles, California was not easy for me (physically or mentally). I have almost no memories of my childhood, only small glimpses of singular moments of time. My memory does not become consistent or steady until I was about 7. When I came to America, my family first had to quarantine in a hotel for a while because of SARS. I was later taken to a doctor to get all of my vaccinations done. I don’t know how I am able to remember, but I have a small memory of the nurse holding me and laying me down onto the table to give me multiple shots. I tried to fight (the orphanage said that I was very emotional and physical) and I remember multiple nurses trying to hold me down to give me

all of my shots. Later in life I learned that I was mistreated and malnourished in my orphanage. Due to their lack of resources I was not fed regularly. When I was brought to America, I was malnourished and my body had natural reactions to overstimulation, loud noises, quick movement, and overcrowding people (a lasting effect that I still have to this day).

“I was viewed by others in terms of what family meant. While I can understand the ‘chosen’ family concept, and it’s beautiful, I felt I wasn’t ‘chosen’ rather I was bought.”

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

As a child, I didn’t fully understand what “adoption” was. I knew that my parents didn’t really look like me, but I was so young when I was adopted that I still resonate with the definition of “mother” and “father” with my parents. I also noticed that when I would go to school and see other students, that their parents looked like them “for some reason.” I undertook a lot of bullying for it as well, but I never understood where it was coming from because “my mom was just my mom.” I didn’t understand that the other kids around me would see me and my family and think that we were “out of the ordinary” because we all looked so different. I thought that I would eventually look like my parents but soon I understood what everyone meant, and that I would never be blessed with their pale skin or their privilege that comes with it. Besides being

bullied about not looking like my parents, I got the usual Asian kid bullying of slanted eyes, fake accents, and making fun of our food. Even throughout high school I was numb to the bullying, microaggressions, and passive aggressive comments on my culture.

I don’t want my writing to feel like I am minimizing the impact that these hate crimes bring to people. I understand that others have similar and worse experiences. But my personalbackgroundisduetohowIwasraisedsurrounded bywhitepeople,thosemicroaggressionsbeinganormalpart of my everyday life.

I have a very complicated relationship with my family. I feel as if I am in a weird middle ground where I know that they love me and I love them. However we’re all still working on understanding each other’s perspectives. They don’t (and won’t ever) understand what it is like to be an Asian-American, an adopted one in particular. And as I grew up, knowing how they would manipulate me or guilt me, understanding that made it hard for me to sympathize with them and knowing what they “risked” to get me. And throughout my whole life I just could never feel like I was ever enough to meet their expectations for what they sacrificed and went through to get me.

However, throughout my life, I have taken a lot of time bonding with my cousins. My cousins are the children of my mom’s best friend. They are also adopted from China and raised by white people. So growing up we all were able to bond over it. As we all grew older and when I started college, we were able to discuss the feelings of white guilt and white saviorism where it was as if our parents were raising us due to the guilt of being white and the history of colonization, as well the concept of white saviorism where they felt as if they were “saving us” from a “disadvantaged” life back in China. Bonding with my cousins we were able to grow up learning

about the adoptee experience through everyone’s different perspectives.

“Discoveringyouridentityandfiguringoutwhoyoureally wanna be (vs what you are or aren’t) - creating your own niche and not like you’re all one and all the other, both exist equally and fully”

- Anonymous

What I learned when I started college and through talking to other adoptees and hearing about their lives, I learned a lot about not necessarily finding the ties that bind to me, but creating them yourself and finding who you are and discovering more about yourself through that. Culture, heritage, and ethnicity is important, but it can also be molded to be fit for you and how you want to view yourself, not necessarily only how others would view you. For example, I am not just adopted, I am also Asian, I am queer, I am nonbinary, I am an artist, etc. It is more about finding out how else you identify and see what other aspects of your life make up who you are. It’s more about discovering who you want to be versus focusing on what you “are” or “aren’t.”

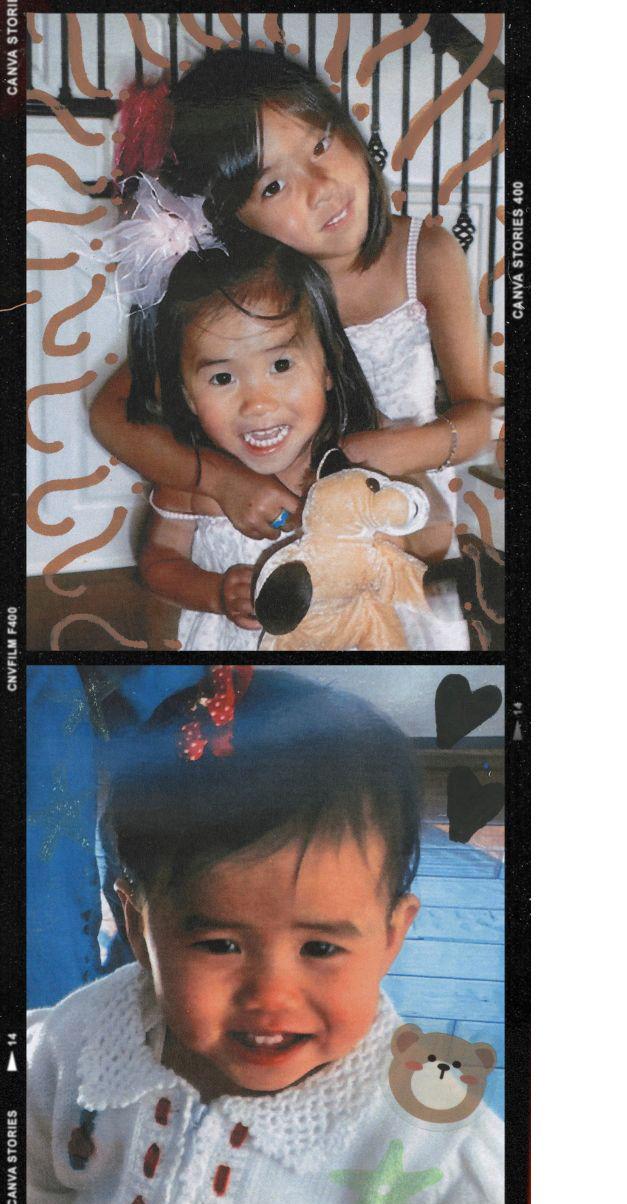

By Isabella Chiu

By Isabella Chiu

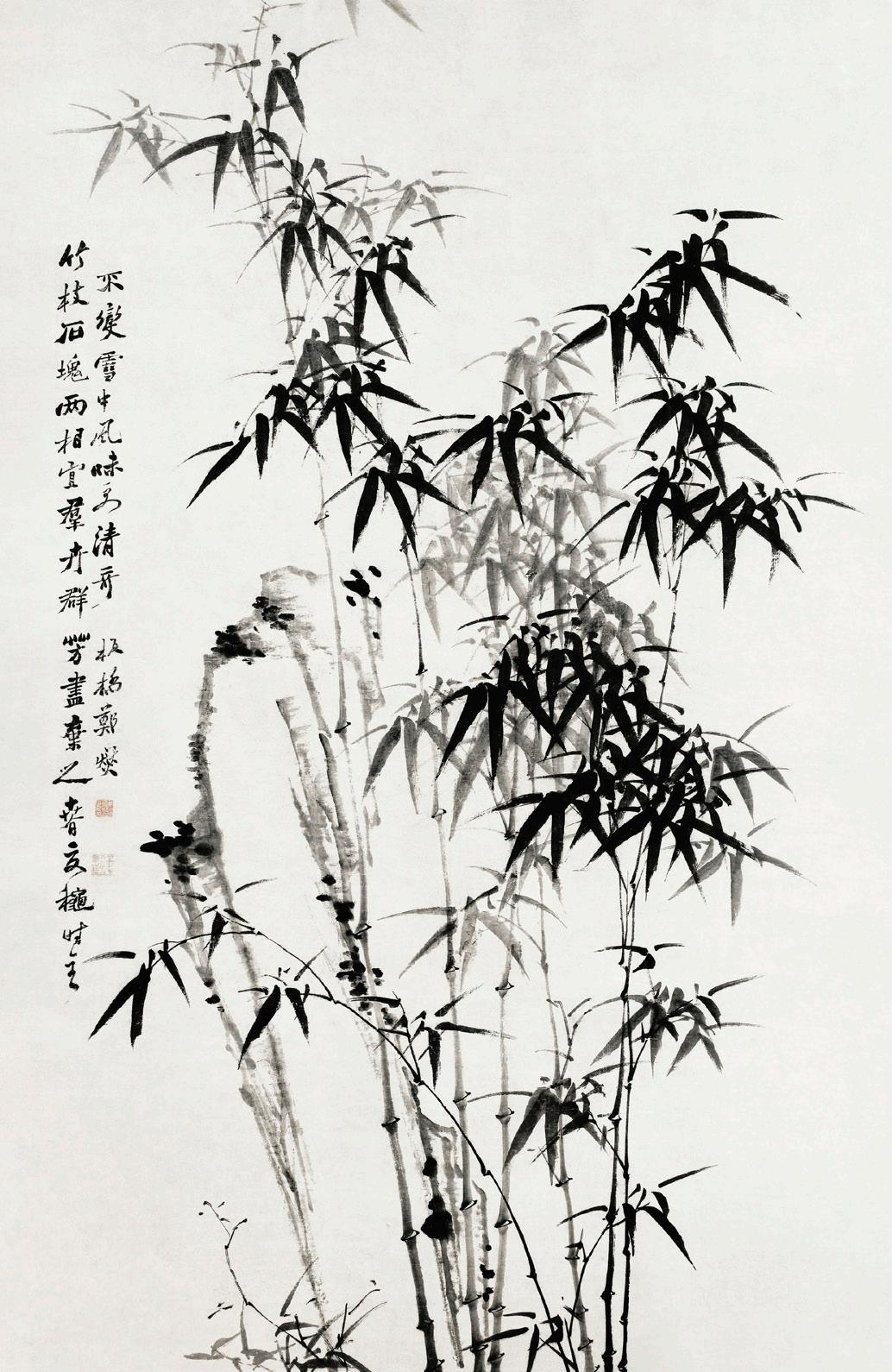

[A/N] My way of connecting to my culture is through stories. I love reading Chinese mythology and classics; however, I’m keenly interested in more modern Chinese stories—mainly Webnovels and light novels that have emerged in recent years. Therefore, I’d like to share a piece that references my love for Chinese mythology and the cycle of life and death in what I would consider a modern twist.

Hello, my lovely readers, and welcome to my blog: “Maddy

In my last blog post, we finally concluded our journey around the world and the greater parts of China. From the warm and beautiful southern regions of Guangdong and Fujian to the bright and vibrant cities of Shanghai and Beijing. I was pleasantly surprised and pleased to see some of my international fans and friends throughout my journey, and I wouldn’t have made it this far without you guys supporting and following me along the way!

So, as a thank-you treat for my loyal followers, I present my final journey and location: the legendary Yellow Springs!

Not to be confused with The Yellow River or Huang He in Henan, or even Yellow Springs, Ohio, The Yellow Springs is the mythical river that is said to be the connection between the mortal realm and the underworld.

I was convinced that this river was only accessible through one’s imagination, as even an intrepid traveler such as myself has yet to lay eyes upon it. Or hear of it other than just local customs and dusty scrolls. Thus, I had given up the thought of finding it at all.

However, much to my surprise and to perhaps many of you reading who have followed me this far, I have discovered that Yellow Springs isn’t a myth!

Thanks to a few friends who have connected me with a local guide to lead me there! And as many know, I am always willing to travel to a place at once, regardless of the danger.

Luckily (or maybe unluckily, depending on who’s asking), I have experienced my fair share of danger and have come out on top in the end, regardless.

Plus, I firmly believe that all places must be documented at least once before global warming seeks to erase these places forever.

Let me paint the scene for you all reading: Green and red trees framed the yellow rapids as silver and white fish jumped between each wave and ripple. The sky was a mysterious hue of light blues and lilac as a flock of red-crowned cranes flew overhead. The ground was soft and damp from the water, yet had an unusual firmness that let my shoes traverse with ease. My guide, Xiao Mei, was gracious as she led me down a pebble pathway fenced in by a sea of white and yellow chrysanthemums.

I’m glad I could see this hidden gem before the Instagram influencers, as I imagine those tall, proud flowers would be trampled underfoot and picked and discarded for a quick photo.

The journey was short as Xiao Mei led me down to the small port where a boatman was waiting. Like Xiao Mei, he also had an animal head and was dressed in traditional Chinese garments that seemed out of place with the setting. However, the difference between them was that the boatman had a more realistic ox head, while Xiao Mei had an almost Animal Crossing-esque cat head. She had said that it was corporate’s way of modernizing the experience for newer generations. However, if you ask me, I feel that the more realistic animal heads were easier on

the eyes.

Xiao Mei said that she would report my feedback back to HR. What a sweet girl.

Anyways, onto the boat ride.

Despite how vigorous the water had seemed, the ride was smooth and calm. For some reason, once I had stepped in, it felt like a weight had been lifted off my shoulders, and I was finally at peace.

Perhaps it was my years of travel or even the hike up here, but I felt oddly light once I sat in the boat.

The boatman, who introduced himself as Da Niu, was a quiet and sweet gentleman despite his appearance. He did his best to make the ride as smooth as possible and gave utterances of reassurance when it felt as if the boat would capsize under the pressure of the waves.

Nevertheless, the ride was short and sweet, and the view was impeccable. It would be one that I would remember for the rest of my life.

I wish I could attach a photo for you all to see; however, Xiao Mei mentioned that all cameras and phones must be left behind to preserve the place’s natural beauty.

As an avid traveler, I understand that rules must be followed, and I didn’t mind as long as I could take my notepad with me to jot down some notes. To which she said it was fine.

After my short boat ride, I was sure to tip Da Niu for his services generously and was finally back on land. However, unlike my entrance’s raw and practically untouched beauty, my destination was a beautiful ancient Buddhist temple.

High white stone walls, capped with red tiles, with its sole entrance being a high pillared gate. Ornately decorated with dragons climbing up the pillars and scenes of Buddhist

hells and rebirths carved along the crimson door. Even over the high walls, I could see an old Ginkgo tree tower above as bright yellow leaves drifted through the air like snow.

The monks that inhabit this temple must have a wealthy benefactor, as even their seemingly hundred-layer pagoda was heavily adorned with gold.

Another guide, also fitted with an animal head and ancient garb, was quick to come to my attendance. This time, the bunny-faced guide, Xiao Tu, led me to where the other guests were.

Imagine my surprise when I saw the variety of people already there! Young and old, all of varying ages and from different walks of life, gathered together in this massive line where I could see some vendors dishing out soup.

Xiao Tu mentioned to me that it was vital for guests to participate in this tradition before entering the temple.

Despite appearances, the line moved very quickly, and in a blink, I had a bowl of milky soup in my hands.

The appearance matches the Yellow Springs I have ridden on, but much more mellow. The soup was topped with a few pieces of tofu and spring onion, which gave it a resemblance to miso soup.

However, the taste was completely different from my expectations. It had a salty umami flavor and seemed more like fish soup than beans. And the white bits, which I had previously assumed were tofu, were pieces of chewy rice cakes that gave a nice sweetness to balance out the salty soup.

If I could best describe it, it reminded me heavily of the soup my grandmother had made me when I was younger. As she had a sweet tooth, she preferred to make the soup more sweet than salty.

Unfortunately, the soup was only a gulp full, so whatever flavors the soup had didn’t linger on.

Shame, it would’ve made a cozy winter recipe.

Afterward, I was led through the gates of the temple, and unfortunately, this is where my memory started to fail me in all of my sixty-five years of living because the next thing I knew, I was in line to cross a bridge!

The bridge was stunning, made of fine lacquered wood and a bright red hue. I wish I could make out the finer details, but with the surrounding fog, it wasn’t easy to see the more delicate wood carvings on the side.

I attempted to converse with others in line; however, they all seemed a little too depressed to speak. All of their focus was solely on the back of the heads of the person in front.

I wouldn’t have known this was a common phenomenon if the person behind me would stop glaring holes into my head.

But I soon realized they couldn’t see me, as their glaze didn’t waver even when I moved.

Talk about tunnel vision.

Luckily, I found a better conversational partner in the line manager, Xiao Niao. She was a sweet bird-headed girl, if not a bit overworked. (Shown by the messy placement of feathers upon her bright-colored head.)

The poor girl!

Nonetheless, she seemed relieved that have someone to vent to. She’s been working this entry-level job for nearly a hundred years! All without paid vacation or sick leave!

I told her that she ought to tell her manager about her work rights and that it was cruel to make a minor (in her lifespan, at least) work a full-time job with part-time pay.

She lamented that it was not without trying but said she would attempt again soon.

Before I knew it, it was my turn to cross the bridge. But before I did, I saw the tall and large rock beside the bridge’s entrance. On it, names written in different languages littered the entire surface. Some seemed newer than others, and some ever overlapped others.

Xiao Niao suggested that I look for my name. It was the most exciting attraction in this place aside from the bridge. She said I was on the right track to destiny if I had a tally beside my name.

But, I was skeptical, given the sheer number of names and numbers that littered the strange stone’s surface.

However, you’ll find yourself surprised by this rock as if it were magic. My name soon appeared with a tally marking ‘two.’ And with a blink of an eye, it quickly changed to three! This means that this would be my third time crossing the bridge, but I find myself a bit skeptical, as perhaps many share the names’ Madison’ and ‘Huang.’ But who knows, perhaps in a previous life, another version of myself has also been a travel writer.

Nevertheless, dear readers, this is where I must end my blog post, as it is now my turn to cross the bridge and see what’s on the other side. I wish I could tell you what’s there, but alas, that is for you to find and discover.

Madison “Maddy” Huang <3

By Ryn Yi

By Ryn Yi

Growing up, I was so sure of my Korean Identity. I loved getting to see my Halmoni and Hadabolgi once a year, they would sit with me and feed me, speaking to me in words I could barely comprehend. “Meogeu, meogeu, meogeu,” were the only words I needed to hear to understand my Halmoni and that each bite of kimbap she shoved in my mouth was a piece of her love. Knowing the handful of phrases I did made me feel a sensation that I could never experience with my white side of the family. I would feel so much confusing emotion well up in my face and chest, simultaneously feeling the need to cry and laugh and hold on to my father and his parents. The feeling made all the loneliness I had ever experienced vanish away, as though the members of my family that had long been at rest were somehow watching. That sensation is something that has been a constant in my life and I have yet to be able to put it into words clearly, but when I speak to other Asian Americans about this so-dubbed “Asian Tingle.” When I was young, I could feel that sensation when wearing hanbok with my siblings, stealing food from my Gomo’s countertop, or watching Girls Generation music videos with my sister. The feeling filled me with bliss and a sense of familial grounding that used to and still perplexes me so much.

After moving across the country and away from my Dad’s family, this sensation became so rare for me. I was eleven years old, in a completely new neighborhood that lacked the smells of curry and stew which seemed to always be present in the air of my childhood street. The period of my life and my relationship with my Koreanness was filled with friends who loved how “cute” and “exotic” my culture was. In middle school, I started to see more Koreans in the media who were not the butt of a joke, but instead the fantasy of red–haired girls who dreamed of Jungkook, and how one day they would fall in love with him. I was so excited that people knew about my culture and wanted to learn more about it, that I never questioned why those girls magically became my friends after discovering I was Korean. I clung so tightly to these girls who seemed to be so much like my Korean family across the country, as they began to speak the same language I grew up around. To my surprise, I could never feel that tingling sensation with them that I had felt with my family. Instead, I felt nauseated and confused hearing such familiar and sacred words being butchered from their cherry lipstick-stained mouths. Those girls wanted nothing more than to come to my house and eat “weird” food with me so they could run home and tell their parents about their lucky friend who had such an exotic culture, and how one day they would move to Korea and be just like me. But I had never even been to Korea. The girls would start writing me notes in hangul while correcting my pronunciation of Korean words, and were surprised at how little I knew about what it took to be a Korean girl like they would be one day. I began to feel a different kind of sensation that acted as the darker twin to my Asian tingle, the

two feelings being so hard to distinguish as an elevenyear-old who just wanted to feel community.

Soon after I realized this feeling was not the same one that I yearned for so deeply, I decided to take a break from seeking it. I had Asian friends who also seemed to never want to talk about our most basic commonality and our relationship with it. Instead, we would make fun of our parents’ accents and joke to our white friends that we would eat their dog after getting the best score on our math test. The Asian tingle was no longer something that I even thought of.

In high school, I had a close friend whose mother was from Laos and whose father was Filipino. We rarely spoke to each other about how much the other’s company meant in terms of being familiar and comfy, but spending time in each other’s houses without having to teach the other about how things were done was so refreshing that I clung to it and tried desperately to not let go. Our group of friends was made up of white faces who gawked at how delicious our seaweed snacks were and claimed that more people needed to know about this amazing snack. My friend and I would send each other looks as they went on, joking about their fascination as a way to get through the endless comments. Those tiny moments would make me cry uncontrollably as that sensation I had given up looking for crept back into my life in a way I was not ready for. It wasn’t until a girl who we were both friends with confronted us about our Asianness that I accepted the Asian tingle was something I could not simply avoid, and that I would have to try to understand it one day. She was a white girl with an Asian boyfriend and two Asian friends,

and she felt left out. She screamed at us and was so flabbergasted that we couldn’t just shut up about Asian things because she knew she couldn’t laugh along. Shortly after that incident, most of my friendships fizzled out as we entered the COVID-19 quarantine.

Being in my house for so long allowed me to redefine how I connected with my heritage and other AsianAmericans in my community. My sister moved back home and perfected all the recipes of the foods our Halmoni used to feed us. We would make kimbap around our square table, eating the scraps while my dad would tell us about how his Eomma used to make them for their adventures when he was a kid in Korea. My sister would make kimchi fried rice for me after days when eating anything was hard. My siblings and I would make overly sweet Melona drinks that would make my dad pucker his lips. And when that feeling would well up as I knew it would, I actually let the tears roll, not caring that I didn’t always understand why they were there, and I found that I was not the only one who was able to feel this sensation. Seeing my community speak up for themselves during the lockdown, and seeing the faces of people who looked like family on the screen letting their anger free was something I truly thought I would never experience. I no longer felt hopeless that I would spend the rest of my life chasing after a feeling of assurance in my identity and decided to fully plug back into the wavelength I had spent so long avoiding. I saw the Asian-American community come together like I had never seen before, and the little kid who would spend hours watching Wong-Fu Productions and Michelle Phan just to see a face like theirs was so excited to feel a part of something.

Coming into college, I have had to completely redefine how I connect with my Koreanness. I no longer had the familiarity of my family and I grew so mad at myself for not finishing my Korean lessons as a little kid, or learning how to cook with my sister. I felt alone and lost and confused and frustrated that my Dad didn’t unpack his baggage soon enough so that my siblings and I wouldn’t have to do so much of it for ourselves. Although, a benefit of being in Boston for school is that with half a day of travel, I can be with my Dad’s family in Philadelphia again. I’ve been able to see them more this first year of college than I have for the last ten years. That experience has overwhelmed me with thoughts and feelings that have made me redefine how I interact with my culture and those who share it. I may never fully be able to understand what that Asian tingle is or why it makes me cry in the car on the way back from Zion market, but I am letting myself dive into that confusing pool of emotion the more time I spend on my own. Being able to go to ASIA meetings and reading others’ works has allowed me to connect with people who are navigating the same confusing world as me--the world of defining how you connect to your culture--and has given me the assurance to take my time with it. Maybe this journey will lead me to do what my Father never could and stay in Korea for a while, or maybe it will be something that becomes a tiny bit clearer every day. However, knowing that there is a huge mass of people out there who are on the same journey as I am has made the Asian tingle much less daunting to me, and I hope to one day join the beautiful community of Asian American artists who are determined to have our stories told.

By Carys Hirawady

By Carys Hirawady

TheRed Thread of Fate is an East Asian myth that an invisible red string connects two people who are destined to meet each other. The thread may get tangled or stretched, but it will never break. Regardless of time, place, and circumstance, people connected by the thread will inevitably intertwine in each other’s lives. The thread is not limited to romantic connection but can extend toward anyone who holds a place in your life.

By Aiya

By Aiya

before your mother died she said, come closer and because I wanted to know you I went to her and learned love came in blue cookie tins filled with only my favorite handstitched rosebuds and wreaths of smoky silence

when I was a child they said we were alike so I sought your stories off their shelf of biographies but their refusal to share more showed me quickly that though an echo is empty it can bear thorns

I am a haunting your last whisper a wraith trying to pass for a speck of funeral ash I am a ruined unread subscription on a grave stone

but grandmother

If unfinished business is not for the living why have they made me a mausoleum?

I am an omen when I was young I used to believe that stillness could be kindness as your mother showed but I know now that their answers will always be empty and their silence is deathly quiet

I used to wonder if different meant You living but grandmother I’ve starved on waiting became an embodiment of apathy frost on a cracked mirror handed down and so for our last rites I want to thank you now that I am older I understand that time does not change It only moves

By Ning Chen

By Ning Chen

Despite the clear skies and the cool sea breeze, the sky had never felt heavier. Atlas heaved under the weight.

“Do not fret, my friend!” A voice, loud as a cheery drunk, called out to him.

Atlas, from his place on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, looked across the plains and steppes of the Eurasian landmass toward his friend—a towering being with thick, silky hair and two golden horns adorning either side of his head. Beneath his feet lay the murky soil of the Earth, and upon his shoulders and hands sat the swirling, glittering skies of the Heavens. He looked at Atlas with a wide smile and a glint in his eyes.

“Pangu,” Atlas called to his friend. “How could I not?”

“You are young!” Pangu said. “Your burden is a momentary one! You will be free thereafter.”

“If I could shake my head I would. My punishment has been fated for eternity. The gods have judged me for my criminal acts and for that I must carry this weight forever.”

Pangu’s laughter was an earthquake across the land, nearly shaking Atlas’ footing.

“Nothing is eternal, my friend! Nothing!”

Pangu’s laughter rang like wondrous thunder in the air. The sound, like the heavy beating of a drum, reverberated through Atlas’ body. For a second the sky seemed lighter, until Pangu’s laughter trailed off into a chuckle, then silence. Atlas looked over and saw Pangu smiling to himself.

“How do you do it?” Atlas asked. “How do you stay so happy, standing there for so long? Does the burden of the Heavens not weigh upon your shoulders?”

Pangu laughed once again. “The Heavens are no burden of mine! Let me tell you, boy, I owe as much to the Heavens and the Earth as the Heavens and the Earth do to me.”

“Is that so?”

“It is! Without me, the Heavens and the Earth would be nothing more than murky chaos, and without the Heavens and the Earth—well, I’d not be born! From their balance I was hatched, and for the whole of my life I must uphold that balance.”

“What a cruel fate!”

“Fate or duty? Call it the same, if you so desire, but since you name it fate then fate it will be named. I’ve long accepted this fate given to me by this land of my birth. It is the whole of who I am, and I am the whole of who it is.”

Atlas gazed at the Heavens upon Pangu’s shoulders. Oh, how they embraced him so lovingly…

“I long to be like you,” Atlas said, “I have no stake in this place I was put. The land I had called home has become a prison I must toil under. How I wish to know myself as I know the land of my birth, but I fear I know neither.”

“You underestimate yourself, boy! I thought the same when I was your age.”

“Did you really?”

Pangu nodded. “It is difficult to understand why the universe weighs so heavy on your back, or why the Earth won’t soften itself for just a moment to allow your feet some rest, but the Heavens and the Earth are my parents, and it is an honor to carry them with me.”

“I fear I do not share the same sentiment. The Heavens and the Earth are no parents of mine. I

would love to honor them as you do, for doing so would relieve my burden, but I feel no love for these weights I bear.”

Pangu grinned. “Who said you had to love them?”

Pangu burst into another fit of laughter. That warm, drum-like sound was so captivating that even in his weariness, Atlas could not help but join in on the laughter. Their voices sang through the steppes and the plains, over the mountains and across the oceans that lay beyond the two of them. For once it seemed that the sky had no bearing on Atlas’ mind; his only duty in this universe was to laugh alongside his friend.

Pangu’s laughter skipped a beat. It caught in his throat and lost its breath, descending into a series of sharp, heaving coughs that sounded less like drums and more like spears. Atlas looked upon his friend and saw that he had ducked his head down low.

“Pangu.” Tinges of fear creeped into Atlas’ voice. “Are you alright?”

Pangu’s smile was weak.

“Nothing is eternal, my friend. Nothing…”

There was a long silence between the two of them. The sky was heavy.

“I was born,” Pangu started slowly, “18,000 years ago. A child of the cosmic egg, I grew alongside the Heavens and the Earth, bearing witness to the universe’s divine beginnings. I have seen the world unfold from the divine principles that underlay its soil, and I am certain that it will continue to unfold as beautifully as it did in my life as in my death.”

“Pangu…” Atlas’ voice was a broken whisper,

too pained to say anything more.

“Please don’t look at me with those guilty eyes, my friend. I urge you not to add the burden of shame onto your shoulders as well. I am glad to have known you as my friend, and I wish that in your years hereafter, you may find solace in the land upon which you stand. Thank you, Atlas, for your kindness. I must go lie down now.”

Pangu sat down into the soft soil of the Earth and laid his head upon the shore, the ocean brushing the top of his head like a mother petting her child to sleep. His arms and legs, stretched out across the fertile plains, melted into the Earth and hardened into mountainous stone. Flesh released itself from bone and separated into flowing streams of water that permeated the land like veins. The silky hair that had adorned his body found refuge in the Earth, growing into leafy vegetation that pointed towards the Heavens. His eyes fixed their final gaze upwards, shining like the sun and the moon. He breathed outwards one last time. A soft wind stroked Atlas’ cheek.

The sky grew heavier.

Atlas grieved for centuries thereafter. Despite his best efforts, he could only look at the Heavens with resentment, the Earth with hate, and that mountainous landmass across the Mediterranean with longing— longing for his friend, and longing to be like his friend, welcomed by the arms of the home that had birthed him. But that burden of the skies that had once been shared by his friend rested solely on Atlas’ shoulders now, and he heaved under that weight.

Bearer of the Heavens and sole witness to Pangu’s death, Atlas thought himself nothing more than a stranger to the land he stood upon. His grief seemed

eternal, but what Atlas did not know was that one day the dirt under his feet would become like a soft cushion that held him, and the clouds would blow playful kisses towards his cheek. And the skies, though burdensome, would rest their heads upon his shoulders and whisper apologies for the circumstances of his existence. And that landmass across the Mediterranean, though transformed into something unrecognizable, would flow with bounty and life, and Atlas will look upon it with love. And one day Atlas will find his place upon this Earth as well, transformed into sturdy mountains at the edge of the Mediterranean. With one final breath, he will blow a loving breeze eastward, and it will reach the ocean shore where those old mountains meet the water. And moments later, a soft wind will brush Atlas’ cheek in return.

InIndia—and almost everywhere else—people believe that names hold a guiding power over their owners. The name you gift your child represents who you hope they’ll become, or the type of life you want them to lead. My brother’s name roughly translates to “sharp as a blade of grass,” which certainly rings true for him, one of the smartest people I know. Mine translates to “inspiration.” Growing up, I dreamed of living up to that meaning.

Aside from the hopefully prophetic translation, there was another reason for why my parents chose my name. After watching my brother’s longer and less phonetic one be mispronounced at every turn, they wanted to call me something that wouldn’t make my life so difficult. So, they chose “Prerna.” Still, people couldn’t quite grasp it. It was unfamiliar, foreign, and exotic.

There was the seventh grade teacher who insisted on calling me “piranha,” and when my friends told her it was actually “Prerna,” she said she liked piranha better than my real name.

There was every substitute teacher who got to my name on the roll-call list and said, “Wow, I’m not even gonna try with this one”—my cue to raise my hand and say, “Here!”

There were the kids in my grade who would confuse me for my friend whose name also started with a P, even though she was half a foot shorter than me, and I was Indian and she was Persian.

There were all the people I’ve introduced myself to, who

instantly—without even trying to say “Prerna”—asked if they could call me something else. Something more manageable or shorter than my two-syllable, said-exactly-as-it’s-spelled name.

My parents love to tell the story of how a young me, when asked her name by a real estate agent, introduced herself as “Jasmine.” Of course I was a fan of the Disney princess, but I was also starting to be exhausted by my name and the struggle that came with it. I thought a name like “Jasmine,” straightforward and familiar to the people around me, would make my life that much easier.

My name has been torn and twisted in every which way, to the point where it’s sometimes hard for me to even recognize it. So when I landed in Mumbai last Spring—my first time in India in seven years—handed my passport to the immigration worker, and was met with “ ” instead of “Prerna,” followed by “ ” (that’s a good name), I teared up a little bit. My name was finally being said by someone who knew how. It was finally being said in a way that I, only half-fluent (if we’re feeling generous) in my mother tongue, never could.

Now I’m beginning to see my name for what it is: something magical, larger than me, always there to connect me to my roots, standing strong and immovable even after everything it’s been through. It’s been my anchor of sorts: so many things, people, and experiences have come and gone, but my name has always been, and will always be, mine to keep and to be inspired by.

by Zoe Leonard

by Zoe Leonard

Jewelry is something that my grandmother and I connect over. She has always passed down her jewelry to me, and wearing it is how I carry around a part of her and a part of my Taiwanese identity every day. As someone who struggles with gender dysphoria, my grandmother’s jewelry helps me feel at home in my body, no matter how I choose to express myself. I’m always proud when someone compliments a piece I’m wearing and I can say, “Thank you, my grandmother gave it to me.” Her sense of style is timeless.

Iam sick to my stomach for how I have yearned. Sickened by how much I wished I wasn’t myself.

I grew up alongside two other adopted Chinese children who I’ve come to call my siblings in a predominantly white city. I also grew up with white parents, who raised a pair of biological children bookending myself and two other Chinese adoptees. But in those joyful years of childhood and growing up, I have slowly discovered a discomfort deep within myself. It’s one that is unsatisfied with my lack of connection to Asian heritage, one that creeps into my mind whenever

I think about how I’ll never have access to its cultural richness. It’s as if all my life I’ve been staring at a doorknob, but have been unable to open it, to invite all of its awaiting possibilities.

I’ll specify that it takes many different forms, like that of an expression of shock coming across my face whenever my Asian friends jokingly tell me “You’re not a real Asian” after not knowing a popular cultural motif or dish, or that of tears when I watched Turning Red , wishing I could relate to Meilin’s familial problems. It’s the jealousy felt when

I see other Asian families so proud of their kin and ethnic background. It’s the sensation my taste buds experience after I’ve tried a snack from H Mart for the first time and I grimace instead of smile out of delight. Most often though, it takes the form of resentment; a deep, bitter feeling of unhappiness with myself for never knowing what might lie on the other side of that door.

One of the earliest and most prominent examples of this remains my experiences with my first childhood friend Abby. Whether we befriended each other because we actually liked one another or we simply lived in the same, closeknit neighborhood, I’ll never know. However, what I can clearly recall were these

awkward moments where Abby would remark on my physical differences that constantly made me aware of race. Be it my hair, nose shape, or skin tone, I have always been very aware of my dissimilarity from the rest of the white population that Abby and most Americans hail from.

I don’t bear any grudges with Abby or her family that often followed up with statements of their own. She was simply observing the world around her. Safe to say, though, these routine comments instilled a hesitation within me that is always alert when meeting new people. This is evidently an experience that most Asian Americans are also bitterly familiar with.

It’s easiest to blame others for my unease, whether that be my adoptive parents or real birth mother. This way, there is an explicit cause for my dissatisfaction

within myself, someone I can direct all of my anger toward, and to give me answers to all the questions I have about myself. Why won’t this feeling go away? Why do I have to question every aspect of my identity? Why can’t I just be grateful for the life that I’ve been given? However, more often than not, I know the finger should be pointed at myself for letting it linger, stay, permeate, and infect my worldview.

I am sick to my stomach for how I have yearned. Sickened for how often I wished I was a different person. Not only because it has made me displeased with the people already around me, but because I know it’s an awful feeling that will never pass.

1:

When the plane lands, and the first wave of hot, humid air sweeps over your body, do not smile. Feel exhausted from the sixteen-hour flight that carried you from your home in California to this airport stinking of asphalt and engine exhaust. Wonder why you’re here. Wonder what brought you to this place, to a country where you barely speak the language, to meet a family that you barely know. When your aunt picks you, your mother, and your younger sibling up from the airport in Taipei and runs two red lights on the way to your grandparents’ house, do not feel exhilarated or happy to be there. Sit in your tongue-tied misery and wallow in obedient silence.

2:

When you arrive, bow to your grandparents before giving them each a hug. This is not a conscious decision—you have been bowing to your elders for all thirteen years of your life, and greeting them always brings about this movement.

Run your hands over the plastic table covering as you walk to your room. Notice the tiny kitchen counter and the plastic chopstick container, decorated with orange, cartoon flowers. You remember this container—it used to live at your grandparents’ old house in California, back when they were still driving distance from you. Now the container lives with your grandparents here, in the suburbs of Taiwan. You will wonder if it originated here as they did, or if it is more like you.

Set your suitcase beside your tiny, twin-sized bed and admire the window view from this 11th-floor condo. Buildings here are strange. It’s a small country, so even as metropolitan skylines melt into greenery and tropical forests, the buildings stay tall, towering up into doubledigit stories. You are trying not to love it, but heights have always pleased you.

When it rains, try not to admire the bone-deep drum of the droplets against the windowpane. Try not to fall in love with the sound. You will fail.

3:

When you go to the nightmarket, inhale the air. Feel how it fills your lungs with the thick smoke of grilled meats, the humidity of Taiwanese summer, the scent of grease and stinky tofu. Watch as crowds of strangers congregate around the one God they may all worship in unison—food.

Get lost in the crowd. Surround yourself with strangers until they press into you from either side, pushing you along this human river of lights, sounds, smells. Let it sink into your skin: the glowing LEDs of bright children’s toys intermingling with the sounds of cheap stereos and human voices shouting order numbers, food names, “fresh cane juice!” “fried chicken cutlet!” “oyster omelettes!” “tsou dou fu!” “gan ze bing!”

Feel the sugar coating shatter as you bite into a candied grape. Let the chili paste and hot oil of fermented tofu sink into your tastebuds. Lean back into your plastic chair and close your eyes. Years from now, you will try to explain this

flavor to a friend, this tangy, spicy, heady sensation, and they will not understand. But right now, you are beginning to. You are beginning to understand this place, and your place in it.

Try not to feel exhilarated. Try not to feel like a tiny red blood cell in this country’s arteries, like a particle in this beating heart, this living, breathing, wonderful creature. (Fail, as you so often will). Enjoy some shaved ice while you can. You will miss it soon.

4: When you take a trip to the city to meet your great aunt, the family’s matriarch and elder sister to your grandmother, you will call her Ee-ma. Bow, lower than you did when you greeted your grandparents, lower than you do for anyone back home. See the way your family orbits around her, encircles her existence, the gravity of filial piety holding together this disparate group of individuals from different corners of the world.

Float into her house on the memories of previous summers spent sitting at the piano bench, crouched by the low-sitting sofas, tucked into the back seat of the dining room table as you fought jetlag to watch kid’s cartoons in Mandarin. You were ashamed then, to admit you could not understand them. You will be ashamed now to admit you probably still can’t.

Brush off your shame for long enough to go to the roof for lunch. The family gathers in a dining room

past the laundry lines and the greenhouse, and you are served rice and bamboo shoots, and sliced pork with oyster sauce. Remember that once, Ee-ma got upset when there was no soup with the meal. Notice the soup now, and wonder if they ever made that mistake again. Marvel at what it is to be a woman with so much power, after eight children and decades of time spent aging as the world spun itself into floods and typhoons and thunderstorms. You have always known that to be a woman is to sit on the throne of subservience. See how wrong you were, and remember. You will need this to survive.

5:

When you wake up, follow the smell of fresh soymilk and fried yóu tiăo into a breakfast shop. Do not wonder why you’ve awoken so early. Feel the morning coolness as it presses into you from either side, making way for thick humidity as the sun begins to heat dew off leaves and blades of grass. Forget for a moment that you’ve spent your entire life growing up in a desert, surrounded by the Hollywood beaches and leaning palm trees of California. Forget that the humidity didn’t always sink into you like hello, “zhao,” “gao zha, gao zha.”

Later, you will take a bus out into the hills and forests. You will climb stone steps up toward a temple, hidden behind thick green trees and winding paths. There will be an old lady at the threshold, hands dipped in a plastic bowl of snap peas as she pulls away their stringy fibers. She will ask you where your father is, if he’s working. Open your mouth, try to answer. You will be interrupted by your mother, who sweeps in to answer the questions for you, mouth forming those bubbling syllables and percussive consonants of Taiwanese.

He’s at home, working, she says.

Stand still in your confusion. You do not speak Taiwanese. You have never spoken Taiwanese.

Remember this moment, years later. Remember it so vividly that you write about it, over and over and over again. Remember this magic, this strange and inexplicable miracle. Remember the moment your mind filtered past unfamiliar phonemes and sentence structure to connect you to this language, this person, this place.

Try to recreate it in text. Fail. Fail over and over and over again.

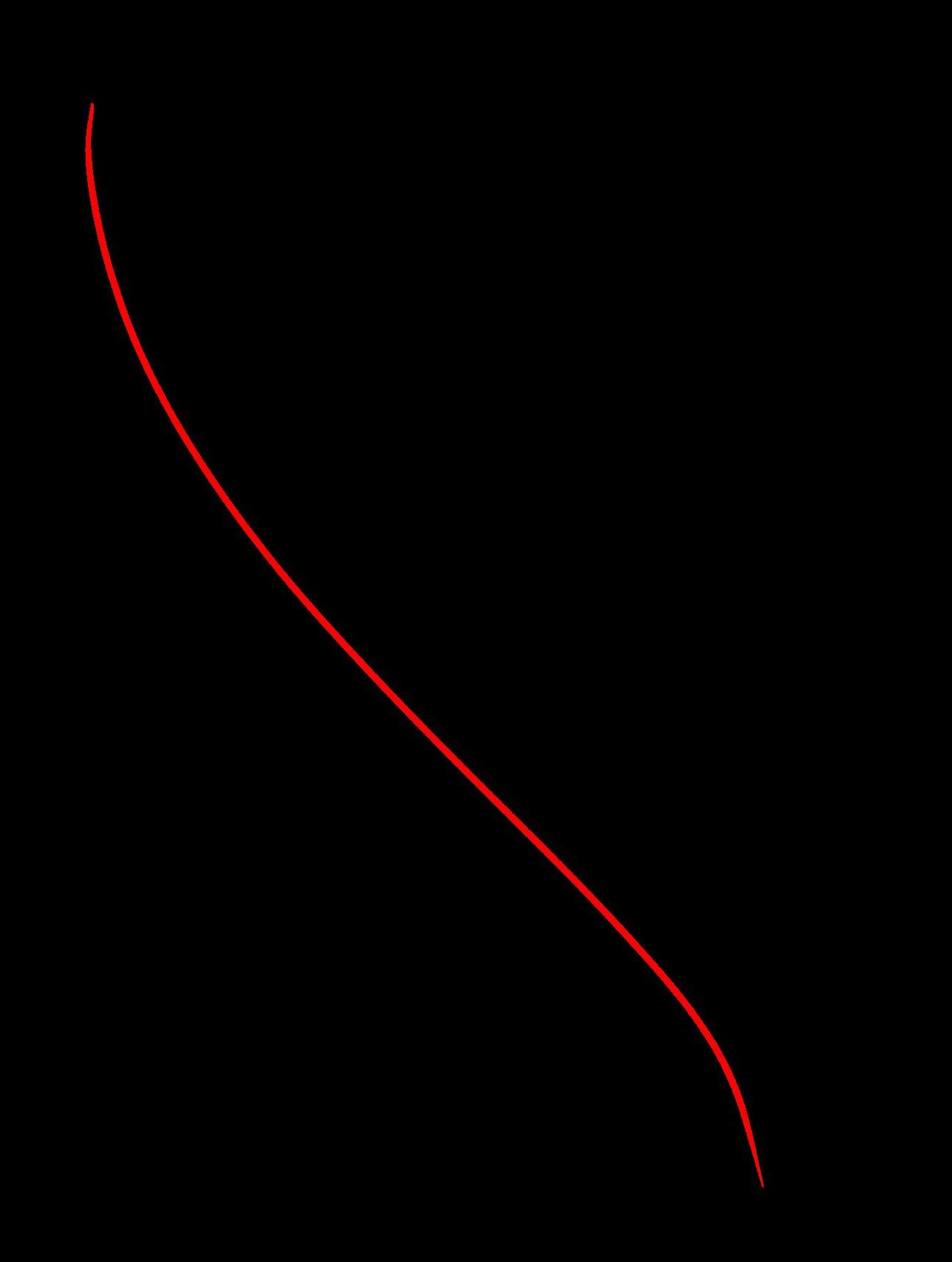

6: When you get on the plane to return home, feel the stem of your identity splitting into opposing branches. Feel the way your roots spread out beneath you and do not touch. Tie a string around your pinky and watch it stretch over the ocean.

It will pull taut. It will dig into the flesh of your finger. It will draw blood.

It’s okay. Sit down. Close your eyes. Remember. Write.

Thank you Jay, Marieska, Jo, and Hannah for your guidance and your friendship. You made ASIA my refuge and provided me with a space where I felt welcome. I am so grateful for everything I’ve learned and continue to learn from you.

Thank you Naomi, JJ, Kiyomi, Grace, and Hailey for all the work you’ve put into ASIA this year. The enthusiasm and ambition you have brought to the E-Board has been so wonderful to see. I’m so proud of all of you and what you have been able to accomplish together.

Thank you to all of our Lunchbox team members and contributors for continuing to share your stories. I am amazed by your dedication to amplifying the voices of Asian students and the incredible work you create every semester.

Thank you to all of our attendees for sharing spaces with us and building a community here. It’s so beautiful to see people celebrate together and lift each other up like you have. I hope, after all the time you’ve spent with your peers, that perhaps you’ve also learned a thing or two from them.

Finally, of course, thank you Katelyn for your leadership. The generosity and kindness with which you lead is so inspiring to me. I could talk forever about your devotion to the ASIA community, but I’ve already written more for this piece than I intended to and I will try to save Marieska some space on this page. Thus, for now, I will just say that I am beyond grateful for everything that you do for us. There is no one else who can do what you can.

Maraming

salamat sa inyong lahat! :) - Vince KunawiczI’ve truly been forever changed by ASIA. Serving on the E-Board has been nothing less than a life experience. Since my first year, during the pandemic, ASIA was my lighthouse: a virtual sanctuary where I could be comfortable with my identity and be surrounded by warmth.

To the Lunchbox team members and contributors, it’s been so special to watch your growth. All your art is beautiful and I’m moved and inspired by each issue; please keep creating because the world deserves to see it. To the co-founders, Jo and Marieska, I’m so proud of you. Thank you for creating a community for creatives to thrive and for art to be alive.

To the 21/22 E-Board, even if we can’t meet as often as before, you know that we’ve got a lifelong friendship. I’ve learned so much from you all; it’s because of you that I’m able to do what I can now for the 22/23 E-Board and org members. Thank you always, and I sincerely love you all.

To the 22/23 E-Board, it’s been wonderful to work together. ou all work so hard; I’m inspired by your passionate aspirations and commendable contributions. I’m so proud of you all, I know you’ll go far. I love you all so much and I’ll always be supporting each of you. Thank you for taking up space with Vince and I.

To Vince, your leadership is exemplary. This community finds comfort through you; you remind everyone the importance of taking care of themselves and that it’s okay to be silly, to laugh and be yourself. You’re so sincere and genuine when seeking the best for ASIA, thank you for your patience and tenderness. You are a dear friend and you are my rock...with googly eyes of course. Thank you for being in my life.

Celebrating ASIA’s 30th anniversary makes me reflect on what ASIA’s legacy means. I thank those who came before me, especially the E-Board of 1993 who registered ASIA as an official org, because 30 years later their work affects students like me and encourages us to take up space. They’ve made ties that bind us together forever. Thank you ASIA.

- Katelyn Reddy

Vince Kunawicz Co-Executive Chair

Vince Kunawicz Co-Executive Chair

“Well I moved on, so keep your two cents, sympathy subtraction.”

- Vernon of SEVENTEEN

“What matters isn’t if people are good or bad. What matters is if they’re trying to be better today than they were yesterday.”

- Michael, The Good Place

- Michael, The Good Place

“The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.”

Jennifer Chan Co-Operations Chair

Kiyomi Casey Co-Treasury Chair

Grace Lee Co-Treasury Chair

Naomi Ash Communications Chair

“Grace Nation > Haileymocracy /j”

Jennifer Chan Co-Operations Chair

Kiyomi Casey Co-Treasury Chair

Grace Lee Co-Treasury Chair

Naomi Ash Communications Chair

“Grace Nation > Haileymocracy /j”

“The thread may get tangled or stretched,