“Change happens when a single individual conceptualizes a new way of living and believes in the practice of that framework...

“Change happens when a single individual conceptualizes a new way of living and believes in the practice of that framework...

Communities are formed, ways of living are enhanced and theory becomes reality.“

Over the summer I was compiling historical research for The Great Leap, one of the shows in the 2022-23 season at the Lyric Stage Company of Boston where I work as a press and digital marketing assistant. In the midst of my research I stumbled upon Linsanity, and the representation that NBA icon Jeremy Lin provided for Asian Americans at a time where we weren’t really represented much in the media (at least in a positive light). The term “Linsanity” gave inspiration and pride for the Asian American community, and gave them something to celebrate and find community in. Jeremy Lin became a trailblazer, and this led me to think about all of wthe trailblazers in my life, in our community, and in our future. Four issues, one award, and many contributors and staff members later,

Photos by Hailey Bochette

Photos by Hailey Bochette

I am proud to say that Lunchbox is a trailblazer. With Lunchbox being the first Asian-run publication that amplifies Asian stories at Emerson, it is something that needs to be recognized and celebrated, and it is an honor to be a part of probably the most ambitious, yet gratifying project of my life.

I would like to thank our contributors and the Lunchbox team for their hard work, patience, dedication, and creativity, and for being the trailblazers behind the Trailblazer issue. Thank you to ASIA and its E-Board for its endless support - Lunchbox would not exist without you and the welcoming community you have provided and continue to provide.

Lastly, I send all of my love and gratitude to my other half, Jo - you are the definition of a trailblazer, and I’m so honored to have gotten to share the co-director title with you since the publication’s beginnings. Lunchbox will not be the same without you, and I’m really going to miss being by your side as we continue being trailblazers - as Lunchbox, and beyond.

Enjoy reading the stories of trailblazers in this issue. Here’s to the trailblazers in our lives, and those who have paved the way before us. Continue amplifying the stories of trailblazers, because the term does not stop with us.

- Marieska Luzada

- Marieska Luzada

I always thought I needed an excuse to take up space. And then I went to my first ASIA meeting.

ASIA is where I first learned to be. There were no expectations. I’d click on the EmConnect link, sip on my bubble tea picked up from the Cultural Center, and I’d awkwardly prop up my laptop to keep up with the Random Play Dance from my corner room in the W Hotel. I have to pay it to Marieska for inviting me to attend Karaoke Night that Spring 2021 semester.

ASIA was the community I needed. In times of mourning, we were swathed in each other’s Zoom presence, which felt so far away from our PWI’s pitying eyes. And day to day, we celebrated each other’s existence – I didn’t have to do anything to earn it. ASIA became my safety blanket, and I wanted to do everything I could to ensure other Asian students could find a space designated just for them to take up space. Enter: Lunchbox Magazine.

In the era of us being dedicated pen-pals during the fall of 2020, I texted Risky my fleeting thought of starting a magazine for Asian students on campus. I was inspired by Gidra, the publication dedicated to Asian students at UCLA, which first published in 1969. The magazine featured pieces by labor union organizers, activists, and academics who were gearing up to curate the first Asian American history textbooks. They were trailblazers.

letters from the co-directors

Marieska was all for it. Before we knew it, we had gotten a green-light from the ASIA E-Board, and had pieced together The Sampler all by ourselves. Then, we suddenly had a whole team of mega-talented creatives and three full issues published today. Well, four if you count this one.

It has been a true honor to work with everyone on our team, for you all have inspired and impressed me. I am so grateful to know that Lunchbox is in the best hands.

To jay, Vince, Katelyn, and Hannah: thank you for being my home away from home, and thank you for believing in me. ASIA E-Board og6 forever!

Marieska “Risky” Durano Luzada, we did the damn thing. Building this magazine with you has been my greatest joy throughout my time at Emerson. Thank you for being a best friend, dance instructor, opposite twin, and CoDirector all wrapped into one. I can’t wait to see the trail we’ve blazed continue to illuminate.

- J. Faith Malicdem

Photos by Hailey Bochette

Photos by Hailey Bochette

Although the Philippines’ international slogan is, “It’s more fun in the Philippines,” sharing the rich culture and history behind the Southeast Asian archipelago can be a bit of a challenge for Filipinos abroad. Iskwelahang Pilipino (IP), a nonprofit Filipino cultural school based in Bedford, Massachusetts, has been operating fully remotely since the start of the pandemic in March 2020. There is a different theme for each school year, and this year’s theme is “Balik2Bayan,” or “Back to the home country.”

“It's a play on the idea that we've been in quarantine for two years now, and so let's experience the Philippines together, let's go on a trip to the Philippines and explore on a trip together,” said Myra Liwanag, Executive Director of IP. “So each class has been a different visit, a different perspective on different parts of the Philippines.”

Founded in 1976 by Filipino immigrants who wanted to bridge the cultural gap between themselves and their American-raised children, IP

is a community organization aiming to bring families together through the exploration of Filipino culture. Organizations like IP have been instrumental in sharing the culture and history of the Philippines to both Filipinos and non-Filipinos alike, especially for Pinoys away from the homeland.

After the United States’ annexation of the Philippines in 1899, many Filipinos came to work in agriculture on fruit and vegetable farms on the U.S. West Coast and in sugarcane plantations in Hawaii.

While the West Coast comprises a large concentration of Filipinos, the population of Filipinos along the East Coast is significantly smaller. Specifically in Boston, there is little public information or history about Filipino immigration in the area. The University of Massachusetts Boston conducted a profile on Filipino Americans in Massachusetts, showing that there were at least 1,405 Filipinos in the city of Boston in 2000.

“One of the things that make the Filipino community in New England different than other parts of the country is that we don't have physical clusters where we live in neighborhoods near each other, not in the same way that you see some of

the other communities,” said Liwanag. “Immigrant communities have been able to come together in Chinatowns or other neighborhoods where there are large numbers living together. We're pretty scattered, we live all over.”

While the Filipino community in the Boston area is much smaller than other ethnic communities in the city such as Chinese, Haitian, and Dominican communities, they continue to make their presence known through establishing organizations, associations, and businesses for the diaspora and beyond.

IP’s primary program is their K-12 school program. When operating inperson, students would come every other Sunday to attend classes from 1:30 p.m. to 5:00 p.m., with merienda, or snack time, occurring in the middle of the day. There are typically four classes in one day, with topics in folk music, folk dance, language and culture, and arts and crafts. Additionally, IP has a music ensemble called Rondalla that performs in many places in Boston and beyond. Rondalla is how a lot of people discover IP.

At IP, there’s a volunteer expectation for every family that comes to the school. While children are learning in classrooms, parents and volunteers may fulfill duties such as wiring networks on

the floor above to prepare for students using Chromebooks, or helping out in the kitchen to set up merienda.

“It's through the participation,” Liwanag said. “We really believe that families will become stronger, and they'll be more affirming of Filipino identity if they work together to do that. Coming to IP, dropping your kid off, and then moving on isn't really what the experience is like for our families. You come to IP, you drop your kid off at assembly, and then you walk around and see who needs help with what, unless you've already got a volunteer assignment and you go do that.”

Moreover, community building for Filipinos abroad extends beyond education or programs catered for children or adolescents. The Philippine Medical Association of New England (PMANE) is a way for Filipino medical professionals to network and meet fellow Filipinos in the region. Dr. Maria Batilo is a practicing internist based in Cape Cod, and recently became the president of the association.

“Basically our main goal is to create socialization among doctors because of how busy we are,” said Dr. Batilo. “So it's a good thing to meet, have a party, you know how Filipinos are we love to party.”

One of PMANE’s most prominent programs is at Emmanuel Episcopal Church on Newbury Street in Boston, where every month they serve breakfast and lunch to homeless people in the area. PMANE also does community outreach and provides health education on issues such as blood pressure and diabetes.

“I want us to be committed to help the homeless community, not only in Boston, but eventually if we have more money or more support, I think it will be good to expand that program,” said Dr. Batilo.

Though the programs that PMANE hold are mainly centered around helping communities through scientific, educational, and philanthropic activities, the association also prioritizes the fostering of community among Filipino medical professionals and their own families. PMANE holds annual holiday parties where its members are welcome to invite their children and families for a night of music, gift exchange, and celebration.

“Being doctors and being in the healthcare field, we're always pulled in a lot of directions,” said Dr. Batilo. “We're really busy, and sometimes our social life really suffers. What I think is good about it is that we encourage the members and their families to attend.”

A main goal for many of these organizations is to show the Boston community that Filipinos exist and they have a rich history they would like to share beyond the diaspora, especially considering the long and entangled relationship between the Philippines and the United States. One way of showing this rich history and culture is through creative mediums such as literature. Founded by Boston-based artist Bren Bataclan, the Boston Filipino American Book Club (BFAB) meets once a month over Zoom to discuss books written by FilipinoAmerican authors. Pre-pandemic, they would meet in person and have the meeting be hosted at a member’s house.

“Since the pandemic, it's been virtual, when we thought it would die off,” Bataclan said. “Now it's stronger than ever because we meet via Zoom, and now we have lots of members beyond Massachusetts.”

Bataclan adds that it is fortunate that with almost all of the books that BFAB has discussed, its authors were able to attend and help facilitate these discussions. Meetings would typically last an hour; members would briefly share their thoughts about the book, followed by the author

discussing their book, and ending with a segment for questions and answers.

BFAB ensures to read a variety of genres for their repertoire, from Grace Talusan’s memoir titled The Body Papers, to Mia P. Manansala’s cozy murder mystery titled Arsenic and Adobo.

“One of the books we've read was Miguel Syjuco's book called Illustrado,” said Bataclan. “He talked about how Filipino literature needs to grow a bit it should have sci-fi and mysteries, instead of just talking about tragic stories about our Asian-American experience.”

Not only does the book club serve as a community for Filipino readers, but it also serves as a support system for those just looking to meet other Filipinos in the Greater Boston area. Most of BFAB’s members are post-college folks, some even going on to marry and have children after being a part of the club for 15 years. BFAB welcomes any individual to join, and Bataclan adds that they hope food can lure folks as a way of community building.

“That's a really fun part of it we typically cook Pinoy food, and then we'd have a potluck,” said Bataclan. food is used as a center for fostering community and inviting all to come together, whether they are Filipino or not.

“When we met in person, most folks read the book, but some folks hung out to just eat and meet other Filipinos.”

Something that ties all three organizations mentioned thus far is that in their activities of gathering folks,

For Trish Fontanilla, one of the founders of BOSFilipinos, food is how the organization started in the first place.

BOSFilipinos’ mission is to elevate Filipino culture in the Boston area through activities such as pop-up events and educational programming. After a few years of Fontanilla and a few of her friends holding Filipino food gatherings at their apartment, she had the idea of starting a few popups to get wider outreach from the community. BOSFilipinos’ first event was a pop-up facilitated by Fontanilla, as well as three other individuals who would serve as co-founders for the organization: Leila Amerling, Bianca Garcia, and Roland Calupe.

“It was a long time coming, but it was driven by food, which of course is the center of everything,” said Fontanilla. “I was kind of at the center of it, bringing in folks and organizing, but definitely have had lots of contributions by other Filipinos to make it happen.”

Aside from holding pop-up events at restaurants in the Greater Boston area, BOSFilipinos also has an online presence that has been holding the fort down for the duration of the pandemic, from highlighting Boston-based Filipino creatives and organizations on their podcast, to Instagram videos of Fontanilla’s mother teaching Tagalog vocabulary.

“Highlighting different people, working in different jobs has opened up the community to those different industries, which has been very cool,” Fontanilla said.

For Filipinos trying to find community in Boston, where the Filipino population is not as big compared to other U.S. metropolitan areas such as New York or Los Angeles, organizations like BOSFilipinos help Filipinos find other people in the diaspora they can call family, even if they are not related by blood.=

places, I

“I think working in different

“The growth has really been about content creation, because people see themselves in the content, and then want to participate or figure out what we’re about.“

always yearned for that community and having not grown up here in Boston,” said Fontanilla. “I grew up in New Jersey and being a transplant I found it a little bit hard to find my people.”

In a non-pandemic setting, the members of these organizations would laugh together, share a meal, and engage in physical banter, as Fontanilla elaborated on why BOSFilipinos does not do any events over Zoom. These organizations share one thing in common since their founding: despite existing for a while, their hope for visibility and recognition beyond the diaspora only grows stronger each day. Though the saying is “It’s more fun in the Philippines,” these organizations show folks the embodiment of the bayanihan spirit of the Philippines through the work they do and the communities they serve, even if they are physically away from the homeland. “I think beyond our community, we just try really hard to keep Filipino culture visible for nonFilipinos in New England,“ said Liwanag. “So that they know we are here, because we are.“

*This story was written in March 2022.

I came across a book by Kip Fulbeck titled 100% HAPA in my cousin’s house a few years ago. I picked up the book and for the first time in my life, I felt an internal connection to my racial background. For a majority of my life, my cousins were the only other people I knew that were also half white and half Chinese-Indonesian. But when I read 100% HAPA, I found an entire collection of people who look like me, who face the same racial issues I face.

Upon recent research, I found that “Hapa” was originally a Hawaiian term, but until then I had found a lot of solace in the word; I did not have to be a “full” anything in order to be a whole person. But there is a lot of discourse surrounding the term, too. Some experts believe that the word originated as a derogatory term, coined by Christian missionaries when they arrived in Hawaii in the 1800s, but others say that any of its uses with a negative connotation derive from outside of Hawaii. There is no hard evidence of the former nor the latter, but that does not take away from the fact that the word is from the Hawaiian language, and is used to describe someone with traces of Hawaiian ancestry—not Asian. So, Kip Fulbeck’s usage of the word to describe any person that is mixed with Asian ancestry is technically incorrect.

Since the debut of Fulbeck’s HAPA Project in 2001, many Native Hawaiians have spoken out about the misuse of the term Hapa. Taking back the term is part of a larger movement to repair the damages made to Hawaiian culture from colonization. After knowing this, how can I still use the term Hapa to describe myself when I’m not Hawaiian? Morally, it just feels wrong.

But is there another term that people of mixed-Asian descent can use that will resonate with them in the same way that Hapa does? I’m not saying that the HAPA Project was “bad” regarding ideas of widespread ethnic acceptance. It was a fantastic tool used to connect many people of various backgrounds. But what I am saying is that there needs to be another way to go about seeking communities as mixed-Asians.

The HAPA Project brought together thousands of people that all share one thing: a lack of ethnic identity. It allowed many people, including Fulbeck himself, to finally have a term with which to completely identify. So yes, it makes sense that many mixed-Asians do not want to unclaim the word that has finally brought them consolation, but it may be a necessary action moving forward. There are too many words in too many languages to find a word that will allow everyone of mixedAsian ancestry to completely identify with. “Mixed” and “multi-ethnic” seem more so descriptions than identities. Still, this does not mean that we should resort back to using the term Hapa. Perhaps there will be another movement in the future, similar to the HAPA Project, that will bring all of us together.

Although Hapa was a way for me to discover the fact that I am not alone in my complex identity, I have now learned the significance that the term holds and I do not want to take the word from the Hawaiian community to whom it truly belongs.

Who am I? I am not Hapa. I am the halves that make up my ethnic background. But I am not half of a person. I am whole. And I do not need a word to prove that.

So that thing about worms surviving as two bodies after being cut in half was a myth. And if I found a worm and cleaved it in half and chucked it across the garden I wasn’t making two, I was killing it. (A productive pastime for an eight-year-old.)

Maybe I killed a lot of worms, and I’m going to try it again. Yes, I plan to be the first. There is no white man a foot in front of me. I will not be described as the first ____ ____ to do it. I’m going to be the first person (ever) to cut myself in half and survive.

WATCH Sorry, that coming down Hurt at first did the job,

OUT was the knife in my brain but the blade bisected me

I would not survive being cut in half like a worm

Zoe Leonard

This side I’m reconstituting with rice, and I’m going to learn Chinese. When I was six I told my mom the right side of my body was the Asian side because it didn’t have my heart

This side I’ll reconstitute with Twinkies and teach white privilege. I hated Chinese school. I speak English. I’m dropping out of college. Or at least I’ll think about it, and that’s another myth.

reclaiming myself.

I know my name. I’ll grow my hair. I’ll finally be me.

This is exhausting. No matter which way you split me, the blood is fifty-fifty. This would be an exercise in futility if you weren’t looking at me (a poem is not quite a mirror; it’s also a window). I’m here to show my face, even if it’s all in pieces. (Aren’t you in pieces too?)

Like Whitman said, you know, “I am large, I contain multitudes, but I would not survive being cut in half like a worm.” You and me, Walt. Me and you both.

I’m

I’m whitewashing myself. I’ll change my name. I’ll dye my hair. I’ll finally be me.

This summer, I was feeling ambitious. Possibly a little too ambitious. I took a trip to Delta, Canada to visit family that I hadn’t seen since before the pandemic, and while there, I decided that I wanted to learn how to do mehendi. Mehendi is a thick paste made from the henna plant that stains the skin a dark brown. It is funneled into tubes and piped onto the skin like frosting into ornate designs that many South Asian women wear for weddings, holidays, and many other celebrations.

When I came back to my cousin’s house after grabbing a pack of tubes from the Indian grocery store, I was ecstatic. I have always been the artist in the family, and mehendi was just another medium for me to experiment with. My older cousin had mild experience in the art form. He used to practice on his mom (my mumiji) when he was in early high school, though he stopped practicing after a single summer. Under his guidance, and the aid of YouTube tutorials, I was confident in my ability to create the designs that I had seen on many brides by the end of the summer.

I was immensely disappointed. Mehendi has a thick, oil-paint-like

consistency that I spent the first few days fighting with to just cleanly come out of the tube. I covered many sheets of notebook paper with uneven lines and blobby circles, frustrated that I could not get any shape to look the way

I wanted it to. It was unlike any medium I had ever experienced before, and my patience ran

A week into my trip, I was still in the midst of a tense debate with the tube in my hand. I had successfully made a few clean lines, but my circles and small attempted flowers remained grotesque and deformed.

I did eventually win my battle with mehendi, though it wasn’t in the way you’d think. I realized a week or two in that I had to stop fighting with it and instead work with the mehendi.

I needed to adjust my approach to the art form and not treat it like the Western art supplies that I have been accustomed to. I had to squeeze gently and rely on working in sections instead of trying to take on the entire design at once. I also had to accept failure and mistakes, since the medium is not very forgiving especially since the moment it touches the skin it begins to dry and stain.

I finally managed to make a design that I was proud of. I

had done it on myself, on the palm of my left hand. Looking at it now, it is not the most creative or visually interesting design that I could have done, but it was one I did quickly and with little adjustment with a paper towel. I snapped a photo and sent it in a group chat containing my closest friends and one of their significant others I didn’t know very well. My friends reacted excitedly with praise, happy for me that I finally managed to work out something that I liked. They eagerly asked questions about how I managed to finally work with the mehendi (as I had lamented my struggle with it to them many times before).

However, one person had something to say about it. Catherine, the significant other of one of my friends, had a word of warning for me. I could practically hear them gasp from the other side of the screen as they texted me to be careful and make sure I was using the right kind of henna. They warned me that I could be using black henna and that I am exposing myself to PPD (paraphenylenediamine, as they so helpfully specified for me) through my artwork. I told them there was nothing to fear from the foreign substance that I had known since childhood, that I knew like the back of my hand (literally). It is my culture, I grew up with it on my hands and in my veins.

Convincing them that I have the right to practice mehendi just made me want to strengthen

the friendship between mehendi and I.

From my eventful and ongoing journey with mehendi, I learned many things. I thought I’d share a few with you in case you ever decide to indulge in mehendi yourself.

1. It will fight with you. You have to let it win.

2. Be patient. It takes time but it will warm up to you, as you do to it.

3. You bought your tubes from your mumiji’s store. It’s made in house. Don’t believe everything you read online.

I was born here but...

I’ve spent 4 years in Japan

4 years in Germany

5 years in England 1 year in the Philippines and 4 years in the Netherlands

I was born from Filipino parents And raised mainly throughout Europe But in an American environment

I feel like I barely pass as Asian I’ve lost touch with my Asian side

My German friend explained it better than I ever could “You just look Asian, but you grew up American in Europe that’s the problem”

I hate the question “Where are you from?”

Are you asking me

Where I was born?

Where I lived the longest?

What ethnicity my parents are?

Which country I enjoyed living in the most?

Where is home for you?

Wherever work sends him

What are you? An outlier amongst most

“Menacing, mocking, inarticulate’’.

These are the words used by Monet’s modern biographer Mariana Alphant to describe Monet’s painting of his wife, Camille, in a room surrounded by fans posing in a bright red kimono.

When I was walking through Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts last year, this painting stood out to me immediately. Not only was the painting itself disturbing, but also the fact that I seemed to be the only one in the gallery who was made uncomfortable by it. This led me to think that I probably did not have enough contextual knowledge, leading me on a quest to find out why Monet created this painting. What purpose did it serve? How was it received by the public back when it was first painted? Why is it so...weird?

Coincidentally, I was also enrolled in a European Art history class, for which we had to write our last paper on an artwork of choice.

I decided to dedicate this opportunity to researching this piece, Monet’s La Japonaise.

During my research, I found that as recently as 2015, The MFA prompted outrage when it invited visitors to dress up in a kimono identical to the one depicted in La Japonaise in the gallery where the painting was on display.

Activists saw this as the museum inviting visitors to “flirt with the exotic”--essentially resurrecting all the problematic notions of the painting itself once again. The MFA’s defense was that they simply hoped visitors, “Come away with a better understanding of how Japanese art influenced Monet,” crediting the artist with “bold use of color, confident brushwork...”

start. At least, this is how I learned from several professors after coming to college on how to start your paper strong.

I thought that this incident would be a good way for me to begin my essay --establishing the relevance and gravity of the conversation from the

However, after turning in the first draft, my professor pushed back, suggesting that I should perhaps not start off my paper so...accusatory? Hostile? ...What?

Initially, I didn’t understand why I couldn’t be so critical, because I was. Also, we were always taught to think critically. “Write through a critical lens,” they said. Further conversation with the professor cleared this up for me a little. It wasn’t that I couldn’t or shouldn’t be critical, but more so that I should be less direct, and build up towards the criticism so that it would be

easier for the traditionally not only celebratory, but also androcentric and eurocentric art world to accept. Demonizing Monet, the painting, and the art institution from the start as facilitators of racism and cultural appropriation would, in a practical lens, set it up for failure, as those who have been traditionally trained would be less likely to take my paper as a serious academic evaluation worth their time.

This approach was beginning to sound all too familiar ---it was this idea that in order for marginalized voices to be taken seriously, one had no choice but to try to work within the system.

Carefully phrase criticism in a way that wouldn’t be too offensive to those whose careers had actively depended on taking part in the offense...

Therefore, rather than beginning the paper with the touchy controversy, I began by simply pointing out the Japanese elements in the painting --the fans scattered irregularly on the back wall below the model’s feet, the bright red kimono she wears and displays, the samurai figure stitched on to the kimono and the geisha on the red fan right next to the model’s face. Most art historians are familiar with the Japonaiserie/Japonisme crazes in 19th-century Europe. The general narrative in the art world seems to be that the Europeans were fascinated with and had a deep appreciation of Japanese art and culture because it was so different...delicate...fragile....

Through further research on Japonisme and Japonaiserie, I found that interest in Japanese aesthetics died down after the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. This violent battle broke down the foundation on which this peculiar interest (fetish, one might call it) stood: the illusion of Japan as an idyllic pastoral paradise. Japan proved itself to have a violent expansionist desire much too similar to the countries the artists who had conjured fanciful images of the Far East belonged to. Moreover, this expansionism is very closely related to power, which undermines the fragile qualities of Japan and the Japanese people fetishized within the minds of the Europeans.

But again, apparently pointing out historically celebrated artworks as oppressive, racist, and colonialist was too much of a direct attack on the art institution to be taken seriously.

Therefore, I decided to use the words of the European art critics themselves to demonstrate how La Japonaise couldn’t be categorized as simply an appreciation of Japanese aesthetics and culture. After all, the art institution cannot deny the words of their predecessors, can they?

Prominent critic and journalist Simon Boubée had written in Gazette de France: “(Monet) has shown a Chinoise (sic) in a red robe with two heads, one that is of a demimondaine placed on the shoulders, the other of a monster, placed we do not dare say where.”

The “monster” that Boubée is referring to is the samurai figure stitched onto the kimono. Through such description, he effectively dehumanizes the samurai. Moreover, Boubée clearly is alluding to something sexual when stating

that the “monster” is placed “we do not dare say where.” Notably, though, it is not only the samurai who was dehumanized but also the female subject. She is described as having “two heads”— the head of the “monster” is also hers. Moreover, she is also explicitly sexualized-literally labeled a sex worker. Taking all this into account, it is possible that Boubée is trying to make a sly allusion to sexual engagement.

There is no reason to cast the female figure as a prostitute other than the fact that she is wearing a symbol of Japanese culture --a kimono-with what Boubée sees as a Japanese monster stitched atop..it is clear that Boubée had not gazed at this painting appreciating Japanese culture.

In a different publication, Gazette des étrangers, a second critic Marius Chaumelin described the painting as depicting, “A head taken out of a Parisian coiffeurs window, turns back with a smile and appears to make fun of a Japanese grotesque making unsuccessful effort to free itself from under the parts of her robe.” Unlike Boubée, Chaumelin does not explicitly cast the female figure as sexual right off the bat. However, the latter portion of his description, the “Japanese grotesque” trying to “free itself from under the parts of her robe” is most likely a sexual innuendo. Moreover, attributing her smile to her making fun of this situation adds the illusion of frivolousness and harmlessness to the picture, functioning to mask the violence of both dehumanization and sexualization. Chaumelin absolves himself from the responsibility of seeing and casting the painting this way.

What can be gathered from this analysis is that not only did the European art critics disparage Japanese culture, they also closely related Japanese culture to the sexualized, objectified woman. The painting was viewed by critics from a position of dominance and with the weapon of oppression.

In the remainder of the paper, I built on this pretense set by European art critics of the past and delved into analysis on how the specific elements within the painting contribute to its disturbing quality. For example, Monet’s wife, the subject of the painting, has dark brown hair, yet Monet decided to modify her identity and turn her into a blonde woman.

She unquestionably becomes a white woman wearing Japanese garments. This is perhaps to create a contrast between her, the centerpiece of the work, and other elements that embellish her. The irrevocable Other serving as garnish to the dominant European.

I ended my paper with the MFA incident. Hopefully, my analysis and build-up would be enough to allow members of the art institution (my target audience) to have a better perspective on the incident--prompting further thought on why they should, perhaps, rethink their practice.

Rather than shying away from all the problematic aspects of the painting because they view these artworks from a celebratory standpoint, maybe there is something deeper and more sinister to the craft and the institution. Perhaps there is something inherently wrong with this celebratory perspective--could it be that it is more productive in our time today to demonstrate progress through knowledge and recognition of injustice, rather than stubbornly choosing to remain in a disillusioned, bigoted past dictated by constructs created by White males which disparage everyone else?

To the East came a lord who by chance spied Our Daimyo’s love who under moon did lie. This lord cast a spell, volition denied. Set upon Himari did in fact defy.

West practice clashed with East and tragedy Did result in mixed energy and mind. Summoned by the conflict, our Daimyo sped To save Himari and expel in kind.

But late did Mamoru arrive to see The way the human in victory fled. Fifteen years he’s sought to free Himari, And filled the human lands with dread. Yet now through players, freedom is in sight: Beware young lord, who you welcome this night.

“A most excellent play,” Christopher Sly said. It still surprised him how much he could enjoy the simple enchantments of theater. He had expected the finer things in life to lose their luster and all hold on his sensibilities once he’d found Himari. Sly thrived on the secret he held over others as they enacted the very myths he now knew to be true. Once, had been just as frustrated, able only to put to paper the idea of a life he could not seek. For years he had poured over stolen works; books that held mastered spells of energy, force, and will. Everything he craved but immortality. Those pages were as empty as his inhibitions, void of all but hollow, untested theories. Sly’s obsession had eventually taken him to Glastonbury Tor in search of the Chalice Well but that too had ended in failure. It was only during his return to London fourteen years ago, that he stumbled upon something inexplicably extraordinary.

The players bowed before their host, underwhelmed by their sudden accostment. As a traveling group, they were used to the incongruous commands of those who flaunted wealth and were unfazed by the demand that tonight they perform at The Bell, the only inn outside Warwick.

Sly laughed and put his arm around the person sitting beside him. Dressed in a fine scarlet gown, their expression was blank and distant. They did not react as Sly ran a heavy hand over their thigh.

“It

to entertain—”

A swift breeze rushed through the hall and snuffed out the lights in an instant.

“Players.” The voice of Tranio filled the dark, his light and cheerful tone gone. “Leave this human with me.”

There were bangs, soft curses, and small cries of pain as the players fled the inn.

Lord Sly stood and squinted into the gloom. “What’s going on?”

There was a rustle of cloth behind him and then a deep sigh. Sly’s skin prickled at the sudden feeling of animosity that filled the shadows. He turned back and reached out for the one who had sat beside him. “Himari. Give me your hand.” His own was slapped away.

“Do not touch me,” Himari said.

Sly frowned and groped in the dark again. He smiled when he found an arm and caught hold of the sleeve. A light flared and Sly raised a hand against the glare. He looked down and saw that the arm he held was not swathed in red, but a shade deeper

“We are honored that you have enjoyed it so, my lord.”

is our greatest pleasure to be able

than ebony. Sly let go and stepped back. “Who are you?”

‘Tranio’ stood a foot over him. Had the actor’s hair and eyes always been so black? “I’d advise you to let go, human.”

Lord Sly dropped the arm he had been gripping and stepped back a pace. He looked around the room and brightened when he saw his companion. Himari stood beside the window bathed in moonlight. The edges of his body and hair were touched with silver. Sly was enraptured by the sight, as he had been years ago when he had first seen Himari on the beach. It took him a moment to notice that the dress he had carefully selected and had specially fitted to Himari, lay shredded on the floor. Instead, Himari was draped in a simple yukata. He looked as if he wore a piece of the moonlit sky.

“Himari.” Sly pitched his voice lower and poured power into his command. “Come here.” He held out a hand but couldn’t bring himself to fully look at Himari’s reclaimed stature.

“I will not.” Himari’s voice was no longer the gentle whisper Sly demanded he use, but a rich and clear baritone.

“You shouldn’t—” Sly’s fingers trembled and reached for the flask he always wore on his hip. He uncapped it and took a sip to wet his dry mouth. “Talk to me like that.”

“Despite your wish, I am not a woman,”

Himari said.

The man who had played Tranio moved a step closer to Himari and crossed his arms over his chest.

Sly felt a shiver settle in his spine as he realized that the...thing, had not stopped staring at him once. “As I made you, you are—”

“Not,” Himari said. “I am not yours to use as you wish. You are not my lord, life, or sovereign. You have not kept me warm. I have lived in a frozen existence since our unfortunate meeting. I have a husband you have kept me from these years I have suffered with you.”

Christopher glanced at ‘Tranio’, who hadn’t moved, and realized that not only was he still staring but that there was something wrong with his eyes. When he smiled Sly felt his fear flop into his stomach. He felt sick. That thing definitely wasn’t human. But then, neither am I. I have my magic still. Sly gritted his teeth and groped for it. He was shocked to find that the deep pool he’d fled the East with, was nearly dry.

“How foolish to believe that power makes one less human,” ‘Tranio’ mocked.

You have maintained the spell so long, it has become a drain on you.

ou cannot face your desires. The truth of the love you seek. You cover it with the claim of wanting obedience though you coveted me.

Unable to bear the pressure of another mind, Sly bent over and was sick on the floor.

“You…” Sly wiped his mouth and glared at Himari. “Traitor.”

Himari smiled. “There is no greater betrayal than to discard yourself. I can face the desires I have and embrace them readily.” Himari held out a hand and Sly watched the other thing come over to take it. It disturbed Sly how much it looked like a human. When it knelt and kissed Himari’s wrist gently, Sly’s knuckles cracked as he clenched his fists.

“You wished me to serve, love, and obey? When you are incapable of those yourself,” Himari said. “There are consequences for forcing any being to act against their will.”

The one in the black robes turned to smile at Sly and for the first time, Christopher considered the possibility that he was outmatched.

“I do, however, owe you a debt,” Himari said. “I have lived beneath your command for nearly two decades of human time.”

Himari moved away from the window and Sly saw that he still glowed in the shadows

as though he stood beneath a full moon. Sly took a step back as the one beside Himari rose as well. He realized then that the inn was silent. Even the soft sounds of the night outside had vanished. As dread filled his belly, Sly yearned to hear the trill of a cricket or the wind and her sighs.

“I shall show you how we entertain our guests. Our plays are quite involved, Christopher Sly.” Himari stepped forward.

“Don’t touch me.” Sly’s mouth was dry, his heart a claw that raked through his lungs.

Himari stopped just out of Christopher’s reach and smiled. “I promise that unlike myself, you will return in better condition than when you left.”

Unable to suppress his cowardice any longer, Sly turned to run. His boot hit the floorboards only once before the inn around him vanished. Instead, a forest of murky greens and scattered light filled his vision. Driftless, Sly’s wail devolved into a stream of bubbles as his anchor held fast.

‘Tranio’ frowned at the kelp blades strewn on the floor. “You swapped them out? I’d prefer him as sea foam. It’s of the same mind.”

“I care for the ocean, Mamoru. I won’t do anything to cause it harm.”

“You finally said it.”

Himari turned to Mamoru with a frown.

“I

concern.” The cool expression on Mamoru’s face, which had terrified Christopher Sly, was finally banished by a smile. It vanished in an instant. “But I’d like to address mine.”

Himari struggled to form a reply and then sighed. “I need time.”

“As you wish.” Mamoru offered a hand and when Himari took it, he drew his husband close. “May I stay with you?”

Finally safe in Mamoru’s steadfast embrace, Himari nodded. Sly had been wise enough to stay inland, afraid the ocean would crave what he had stolen. Exhausted, Himari rested his forehead on Mamoru’s shoulder, comforted by the scent of salt. He breathed it in as he put his arms around Mamoru’s waist as the last of his strength left him. “Take me home, gege.”

Mamoru swept Himari up into his arms and left the inn. He walked to the nearest beach in silence, unsurprised when Himari fell asleep midway. Once they reached the shore, Mamoru stepped into the waves without hesitation. He stopped only when the water reached his waist. There on the foreshore, Mamoru’s legs shifted back to a powerful tail covered with bloodred scales. He smiled under the full moon’s light, then dove under the next wave with his reclaimed love.

“I did not wish to give him your name.”

appreciate your

When tempted to steal or cheat, keep in mind This tale of revenge, sweet. To take someone Not inclined, you very well may risk in kind The fate of the knave known today as Sly.

Below the ocean, he did work and stay ‘Til his debts to Himari were thrice repaid.

When to the shore, Sly did return one day He found his house and body all decayed.

For to Himari, human time is slight. Should you espy on moonlit beach a fin, Do not consider it with all delight: Go back or you may see our Daimyo grin.

If you insist and pursue, one promise We can make, from us there’ll be no solace.

Dear Dad, You have never once said the words, “I love you,” to me.

And because of this, I resented you.

Every movie I watched as a child depicted familial love in ways that I could not relate to as a Chinese American.

White storytellers convey love as words of affirmation and quality time and this led me to believe that these love languages are considered “normal” and “American.”

And because I had never received love from you this way, I assumed that you didn’t love me at all.

I envied my white peers who could relate to those movies whose fathers told them, “I love you,” and spent their precious time creating long-lasting memories with their children.

I’ve spent my whole childhood longing for these three words and could never shed the feeling of neglect.

Movies have created a void that I could not fill.

But when I watched Everything Everywhere all at Once for the first time, I felt whole. It was as though all of the times that I doubted your love for me had suddenly vanished. Instead of saying, “I love you” to her daughter, Evelyn says, “No matter what I will always, always want to be here with you.”

This was the moment when it all clicked for me.

“I will always want to be here with you,” holds a special meaning far beyond love, especially in our culture.

It means that love is the choice to stay.

You never told me that you love me because you never had to.

You show me through your actions, your sacrifices, and your presence.

Everything Everywhere All at Once depicts love in this way, and it makes sense to my identity and our culture. It taught me that love cannot be condensed into three

After watching this movie, I no longer desire the way white storytellers convey family love.

From now on, when you hand me random platters of cut fruits throughout the day, lecture me about eating healthier, or come home after long hours of working at the restaurant and Uber-ing, I will appreciate these acts of love and never take them for granted.

I’m so sorry that it took me so long to understand your love language.

I’m writing to you because I want to thank you for staying with me.

Even if our language barrier and cultural differences have divided us and caused us to fear being vulnerable with each other, I need you to know that out of all the places I could be,

“Whenever I travel and I find an Asian center or different Asian communities, it’s something that I naturally gravitate to.”

“It’s a lot easier than I thought. I feel like I’m really lucky that anywhere I travel I can find food that I’m missing. Japanese culture and food has been so internationalized so it has been easy for me. Other Asian cultures haven’t been as internationalized so it’s harder to find.”

How do you stay connected to your culture while being here?

“I live in a place where Asians are the majority so you definitely miss that sense of community and being around Asians. I’ve learned that to get the best food in European countries, go to ethnic places to eat (whether it be Asian or LatinAmerican and so on).”

What do you miss the most from home or Boston?

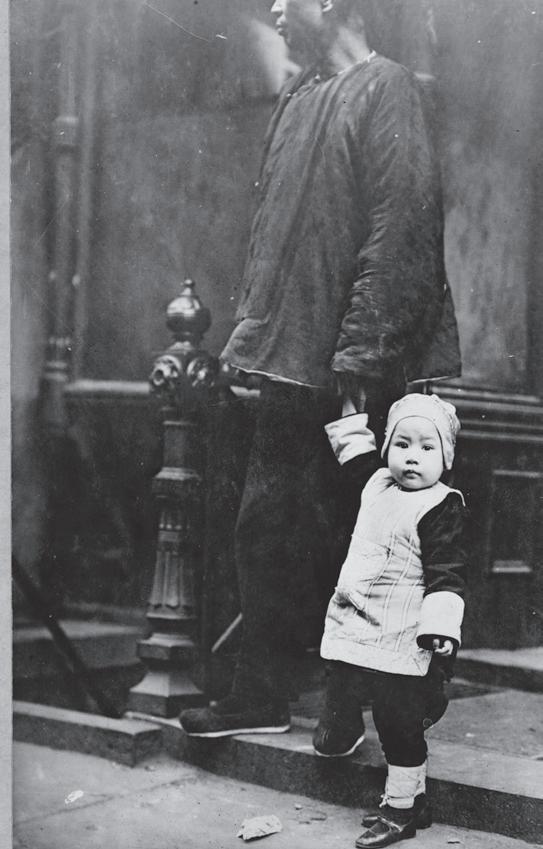

Summer was not any cooler because of the Sacramento River flowing past Locke, California. If it were the 1940’s, I could slip into the river and swim with salmon larger than a child as my grandfather did when he was a boy. Now it’s only good for boats and bird watching, not fishing. But that doesn’t stop me from coming to see the small town nestled against the river banks just shy of Walnut Grove.

I don’t remember the first time that I went to Locke because for as long as I can remember, my love for that town has been there. I’ve visited with friends and other relatives, but the town truly breathes whenever my grandfather is present. His stories always bring us back through time to the years before half the town emptied temporarily in 1942 during the Japanese American Internment.

My grandfather always tells me of the day when he was a boy and all the Japanese in Locke were suddenly gone. He says the Japanese left their land in the care of their Chinese neighbors until they could come back and reclaim it themselves. But when they did come back, none of them stayed. Slowly, they all left Locke, unwilling to live in what had become a painful place. Next, he talks about when he served in Japan. He tells us of their traditions and that he loved Japan and was welcomed there. Sometimes he speaks to us in Japanese. His stories are brief, but he always smiles when he remembers.

Today we are here to greet my GreatAunt Connie; the town’s appointed mayor. She welcomes us warmly as she always does and then leaves us to tour the town as a group until lunch. Each visit is always the same when my grandfather is here. We walk the same streets, visit the same spots, and he tells the same tales, but I never tire of hearing them. Each time there is something a little different that he shares and I can never turn away from listening to him. I know that I will hear something new and that my favorite story is coming.

Per tradition, we head to the end of Main Street. Still unpaved the street is packed; scuffed, and dusty just as it had been when the town was first founded in 1913. ‘The only town built by the Chinese for the Chinese’. We always stop first at the Chinese School where my grandfather attended lessons after going to the brick white school in Walnut Grove. The walls here are faded and yellow, worn and spent from their decades of bleaching in the sun. This time though, my grandfather walks down the first aisle and sits at the same wooden desk he used as a child. I’m shocked when he fits, but even more so when he laughs and smiles. I want to take a picture of him there, a piece of the present pasted onto an image of 1939. I know he won’t let me take one. I no longer ask, but instead treasure the memories he gives me. I feel this one slide down into the core that makes me Asian, Chinese, Cantonese, descendant, sixth generation.

Everything from his days in that small schoolhouse is still there. Portraits, parade pictures, and dozens of characters decorate

the walls. I can’t read them but I always try, unthwarted by the barrier between his education and mine. The strokes are beautiful and even if I cannot understand them, I can still feel the pride in my grandfather’s eyes as he stands beside me and reads them. Once I asked him, ‘What do they say?’ And he told me, ‘History.’ This time when I ask he says, ‘I cannot remember.’

Once we leave the school we walk past a mix of shops and personal residences. They look like sets borrowed from an old western with their false fronts, apartments upstairs, and front porches. There are boardwalks placed between the buildings to keep you out of the dust. My grandfather leads us down one. The shadows of plants and hung laundry on his back fill the gaps in his stories and for a moment, I can see him walking home this way to Aunt Connie’s house as a boy, then a young man. The greenery planted along the boardwalk makes it easy to forget what year it is and that we are not cut off from the sky. I don’t look up. Here it is easy to imagine that if I follow the boardwalk, I will arrive in the 1900s when Locke thrived. Past the shops, antique stores, scattered family houses, abandoned theatre, single bar, and only restaurant, lives my Great-Aunt Connie. Her house is small and tidy for its age, though all the floors creak. It sits between an orchard and her personal garden. There she still grows vegetables and fruits to cook. While my Aunt’s fruit trees and vegetables are beautiful and neat, it is her xeriscape that is the source of my favorite story.

On one side of her house, there is a garden favored by cactuses and desert plants settled comfortably in numerous old toilets. The first time I heard the reason why my Aunt is famous for this garden, my grandfather had to translate for me. Now when Connie and my grandfather tell it again, they both speak in a mix of Cantonese and English. It doesn’t matter now how I hear the story. I am a captive audience and they know I will listen to their every word and bind it to me.

Again Aunt Connie tells us how when white people moved into Locke they did not want to use the same toilets that the ‘yellow people’ had touched before them. So they threw them out and replaced them with new ones. My aunt took it upon herself to gather up the discarded toilets that had been dumped onto the land

she and her people could only rent, not own. She cultivated them all into a garden that has grown and flourished so well, it was featured in the newspaper. The garden is as beautiful as my Aunt’s will; her love and determination for Locke on display for those who know the story. I don’t have to understand her words to know that this is a piece of family history I will always treasure; a memory that will be forever linked to my Aunt Connie and Locke.

After the toilet garden, Connie gathers everyone and we all walk over to Locke’s restaurant for lunch. My Aunt knows the owners; like most of the residents left, she helped them settle here. We share tea, rice, vegetables, and my grandfather’s favorite, duck. Everyone insists I have at least five bites of everything and drink as much. I can barely eat as I sit in silence and listen to them chat and order in Cantonese and Mandarin. There is no English now and it reminds me of the reunions of my childhood before the family grew too large and too apart. I don’t look up, the familiar taste and sounds will be unbearable to part with tonight and I don’t want my ignorance to interrupt.

The sunset is the unwanted reminder to all of us that Locke is starting to shut down for the night and it’s time we all head home. It’s only an hour’s drive but the trip back always feels the longest. Leaving Locke is always hard but today it is excruciating. Or maybe it’s always this way, and I’m just good at forgetting the ache that’s seeping through me now. Every time I visit I want to stay longer. A part of me is always tempted to stay here in Locke, where I can feel my roots

the most. My grandfather told me stories of ancestors and it is only in Locke that it is easy to believe that they are present and soaked into the earth we walk on, the trees, air, sky.

How can a place I’ve never lived in have such a hold on me? I’ve tried to explain it but always fail. I love Locke more dearly than the town I grew up in, and the people I regularly meet. Every time I think or speak of Locke, or the generations, of my predecessors living there, it almost brings me to tears. My heart constantly heals and breaks in Locke. It’s a wound I crave as much as I wish it to heal and bring me peace.

Lately, I’ve begun to wonder what my children will feel when I bring them to visit. Anger? Pride? Hope? Desperation? When will I be able to bring myself to tell them the stories I’ve known all my life? Today, this town is shielded in layers. Its history has been covered by tourism and niceties in the narrative. There are secrets now that only I will feel when my family walks through these haunted backstreets chased by memories I wouldn’t know either if my grandfather and Great-Aunt Connie had not passed them on to me. My only solace now comes in knowing that Locke was a memory they were in favor of not forgetting.

You. Tell me that DREAM again.

The one with the lips on our faces in motion, silent. Apart.

The one where I swallow the ocean between us in a shot glass so I won’t feel a thing when I tell you that it’s over.

The one where I tell the truth and you’re crying, and the one where I don’t and I’m HAPPY.

The one with Paris in the rain.

But if I think about how the stars we see are so many more miles apart then it’s like we’re in my car again. Crash.

Wake up.

Before I smoked for the first time you told me not to open any doors or walk through any windows.

But look through that window. Tell me he isn’t therebeautiful.

Tell me that I’ll die if I JUMP through the frame because gravity already has my collar, unbuttoned.

And we’ll hose my body off the sidewalk, with Parisian rain. Fresh, from the catacombs. Dead water so dead it’s almost wine. It’s almost

ME.

But I could get drunk off milk and honey if he were mine.

So tell me that DREAM again.

The one when we kissed by the neon rack of super pretzels in that Seven Eleven off route 22 - but not after watching our tongues change color from the slushie machine.

It was midnight. It was Jersey. It was raining. It was Paris.

The one where we buy convenience store mangoes and eat them in the parking lot with a swiss army knife, the war fresh in the violence of slicing yellow cheeks into chess boards as I sucked the pit dry.

We passed the blade back and forth to pick the fibers from between our teeth. Then the knife slipped in my fingers and slashed my mouth into lips and I’m swallowing anger. I’m swallowing teeth. Liquid teeth.

In movies, the bigger BOYS always spit out a tooth or two because it makes them look so hard.

But has Don Juan ever looked under his pillow expecting dirty quarters from the tooth fairy? . No. So I swallowed hard. My teeth, the quarters, the knife. The pit. The ocean.

Does that make me a glutton? Because I know Don Juan wasn’t born with teeth. He was born with ivory bricks in his mouth.

And when the tooth fairy comes for him, they make LOVE. They make money from his body. But I swear, when he’s smoking the last cigarette, she warns him not to walk through any windows. So he throws his breath into the Parisian rain as if it’s caution into the wind and steals a glance through that frame thinking to himself.

He’s beautiful JUMP.

“Do you guys have any paprika?” With every visit home, I find myself struggling to cook with the contents of my family’s kitchen. Growing up, dinner at home looked like frozen chicken breast with rice and a veggie – either canned corn or peas. Lunch was a frozen pizza from Trader Joe’s. Breakfast was spam, rice, and eggs, which is actually a very popular Filipino dish. Realistically, my anxious belly could only keep down a pain au chocolat most mornings. My mom worked long hours and dealt with commutes that were seemingly more time consuming than her actual home health management job. My dad’s a big believer in the divine convenience of a frozen meal as a stay-at-home parent juggling driving me and my siblings around 24/7 with his bible studies and group phone prayers.

Other times, my parents would take us with them to indulge in the joys of authentic ethnic cuisines at family-owned restaurants all throughout LA county: El Atacor in Cypress Park, QQ Kopitiam and Heider Baba in Pasadena, and Benten Ramen in San Gabriel – it was the norm for us to go out to eat. It was easiest, and it was a rewarding experience for getting through the day.

Sometimes, my Lola would come over to take care of my siblings and I during the work week. She’d make us lugaw, chicken adobo, pancit, egg rolls, dinuguan, and sabaw with assorted veggies. One of my only core memories of me learning to cook is when Lola taught me to wrap egg rolls. We formed an assembly line of two, with me spooning filling onto thawed squares of wheat flour and her folding the top and bottom corners of the wrapper inwards toward each other, then tucking the right flap over to make an envelope, ready to seal with a roll into the left flap.

Every now and then, I’ll visit a friend who’s prepared dinner for us for the sake of protecting our hurting wallets. Other times, a friend will swing by my apartment to make use of the kitchen, which I claim to use rarely. They’ll make dishes that have been passed onto them – recipes done through muscle memory – with rice cakes, kimchi, soybean chili paste, and sinigang mix. It’s delicious, and I always rejoice in their talents, but then I wonder if I should have done a better job of begging my grandparents to show me Pinoy recipes as a teenager and still living in close proximity to them. “So… what does Jo eat?” my newest roommate, Sadie, asked Maddi, my roommate who’s lived with me for over a year now. “Mmm, pretty much whatever Gabe makes!” Maddi replied.

In our year and four months of being together, Gabe has taken my kitchen (and my EBT card) by storm. Xe’ll come home from the Central Square farmer’s market each Monday performing a showcase of dancing purple carrots, eye-catching sweet potatoes, fluffy pumpkin bread, and enticing Zaatar focaccia bread, finishing off by sneaking a green bell pepper beneath my nose to sniff its strong fragrance, proving just how organic and full of personality it must be.

Homemade ramen, stir fry, vegetable medleys, and breakfast hashes all somehow find their way onto the dining table before me, plated artfully, all because of Gabe’s love for cooking. In a pan, midsauteé, they’ll carefully lift their turmeric-covered basmati rice in a spoon to my mouth, disproving my doubt in seasoning rice with anything other than butter or oil. “Right?” they say with a hint of I told you so to my surprised satisfaction.

Sometimes, the desire to eat out at my favorite restaurants, despite my college-student-hurtingwallet that would advise against it, takes over in times of stress. It’s a self-soothing mechanism. I had a hard day? I deserve a Felipe’s burrito, or maybe some Go Go Curry vegetable tempura. I don’t have time or energy to cook for myself.

And then Gabe will insist we stay in and put our groceries to good use, making up for my unsatisfied craving for All Star pizza by staging a five-star gourmet restaurant in my own kitchen and dining room.

“For tonight’s appetizer, we have two slices of toasted potato bread and goat cheese,” they recite in a French accent.

“For our main course, the chef has chosen a breakfast hash with sweet potato, egg, vegan apple sausage, spinach, gouda, and parmesan,” Gabe continues, with a towel slung over their folded forearm and chin tilted up.

Now when Gabe cooks, I’ll take note of the seasoning, technique, and order of operations xe applies in the once seemingly difficult meal that I thought I had no capacity to make. I always feel a little helpful in the process when I’m able to cook a pot of rice for us, and it helps me ease into feeling confident taking on a stir fry meal all by myself. Then, before I know it, I’m using the cutting board, and running back and forth between the counter and the stove, and if I’m feeling frisky, the oven.

I don’t shy away from trying new vegetables in my back-pocket recipes, or asking a restaurant server or friend how they prepared a dish for me. I’ll often text my Lola asking for the order of operations of the food she made for us growing up. I think my interest in her recipes have brought her a lot of joy – so much so, she made a family-sized serving of

pancit for my 21st birthday despite being across the country from me. She didn’t hesitate to send me the recipe for the pancit, either.

For the first time in my life, I’m able to fully enjoy the process of cooking. I understand that it’s an act of care and mindfulness. It is a love language. And even though I feel more comfortable in the kitchen, I will admit that Gabe still makes the majority of our meals. They’re a natural chef. Back home in Pasadena, I take time in the morning to prepare some egg toast for my family each time I visit.

“Wow, Faith. This one’s pretty good,” my dad admits. “How’d you make it again?”

Dhanyabad, Maiju, pugyo, pugyo. (Thank you, Auntie. No more, no more.)

My Maiju (my mother’s sister-in-law) smiled politely and hobbled away with her pot of steaming hot rice. These were the few words I could exchange with her as she attempted to fill my stomach to its breaking point with delicious, homemade Nepali food and tea. I swallowed hard, gripping the chair I sat in, anxiously peeking around the table at which my Nepali family sat. This familiar feeling had settled in my heart as soon as I stepped foot into that door earlier that morning. My mother and I had decided to travel to London in March of 2022 to stay with some of her family I had never met before. I was suddenly greeted with blessings, hugs, and noise. Noise I couldn’t understand. Noise I couldn’t speak.

was trying to speak more English to acclimate to the environment of our growing family business, and my white father, who could speak Nepali, often just spoke in English. This led me to speak English fluently, but only be able to respond in English to my parents when they spoke Nepali to me. Oftentimes family-friends would laugh when an argument ensued between myself and my parents when I was younger because they could only understand my stubborn, English retorts towards my parents’ Nepali warnings. This laughter has accompanied my articulation of words practically my entire life. Giggles from my peers when I would pronounce English words differently, confusing me as I heard my mother use the same 'incorrect’ pronunciation at home. Chortles from Nepali friends when I would knit my eyebrows in confusion at their questions, prompting them to slowly ask me if I knew 'hello’ or 'elephant’ in Nepali. Laughter would erupt from my Nepali family when I finally managed to piece together a sentence for them. It simply welcomed an, “Oh bhanji, you’re so funny. You’re so cute.”

This is what separated me from my own culture for most of my adolescence, simply because I felt as though I didn’t belong to it. I found myself begging my mother to let me stay home from Nepali celebrations

that were held in a small, nearby community space every once in a while.

Once I was brought there, I clung to my white father, feeling completely out of place and terrified of being asked to go out on the dance floor or be asked a question in Nepali. I would refuse to wear traditional Nepali garments because they were “too itchy,” and would opt for a white button-up shirt, some khakis, and my favorite pair of sneakers.

As the years went on, no matter how much I tried to submerge myself in American society and the expectations it still holds today, I found myself being met with the reality that I was and am different. “Jokes” were spat out at me in the hallways of my middle and high school.

“Please don’t eat my dog!”

“What’s it like seeing your life in widescreen?”

“Be careful, Khatima definitely knows karate.”

Being constantly mixed up with the other girl in my grade with a similar skin tone as mine and a name that also started with a 'K,’ despite her being Thai and me being Nepali. Watching my two other peers be deemed as brothers for similar reasons, despite one being Thai and one being Japanese. Seeing the transfer student from

China be bombarded by students asking for homework answers and denying his concerns for bad grades on assignments because he’s Asian, therefore he can’t possibly do poorly on schoolwork.

Yet, the five or six of us Asian students in our grade let it all slide, because we didn’t realize it was all blatantly racist. The Asian American students, like myself, had grown up barely knowing our parents’ native tongue, and had also grown up in a town where there wasn’t really any Asian representation or community present. The transfer student just assumed that this was regular American culture, and went on quietly in the back of the classroom every day. This lifestyle we all unknowingly suffered from definitely correlated to my rejection of my own culture, seeing as though that part of me drove people at my school, adults and students, to make assumptions or see me as different, when I just anxiously wanted to fit in seamlessly.

It honestly wasn’t until quarantine that I realized how horrendous this lifestyle I accepted was. My mother and I were the only ones in the house, which led us to spend a copious amount of time together. I was able to grow and mature with time to myself, truly realizing how my culture makes me different. I realized that my individuality was unique and beautiful. I hold a special connection to a nation of people, certain traditions and holidays, and certain beliefs as well. I am aware that I am currently residing in a country overflowing with systemic

racism within society, but there should be no excuses for such behavior and actions. I am tired of the normalized generalizations and racism Asian people in America, like myself, face everyday.

I sat back on the cushiony couch in my Maiju’s living room, exhaling a satisfied sigh as I rested my hand on my filled stomach. My eyes wearily fluttered as I sank into the warm embrace of the candle-lit room, the smell of incense and Nepali food wafting in and out of my nose. Laughter and conversation rang out around me as I picked up on Nepali words here and there, some with British accents and others fully Nepali. A hand rested on my shoulder, and I looked up to be greeted by Maiju’s wrinkled smile and her sparkling, aged eyes. With a heavy Nepali accent, she spoke: “Tired, bhanji? I love you, bhanji.” She showed me her toothy grin and hobbled back to the kitchen to finish dishes, and my heart glowed with content. This content I had never typically felt before surprised me, but I accepted it with warm embrace. I realized then and there that language barriers can cause struggle, but it doesn’t make me any less Nepali, and any less loved by my family. The initial anxiety I had felt when I first arrived in London eased away, as I was cared for in ways that exceeded audible words.

This experience only just happened earlier this year, which goes to show that

each day I am still learning and growing to love my Nepali culture, alongside my white background whilst living in a western society. I couldn’t be happier now to share two different cultures, but the balance between them is still being workshopped each day. Calling out the misrepresentation and racism in our society today, and standing with my community where I can find it is what drives me to keep learning and keep growing, and I hope to be able to share my experiences and hopes with others who may

CW: microaggressions,

At some point in your life, you’ve wanted to be a superhero. Maybe not the spidercrawling or cape-flowing comic book type, but somebody who displays leadership, exudes confidence and charisma, and inspires others. You’ve wished to create a path for others to follow–one that makes it easier for those after you, and paves the way for greater things: A true trailblazer.

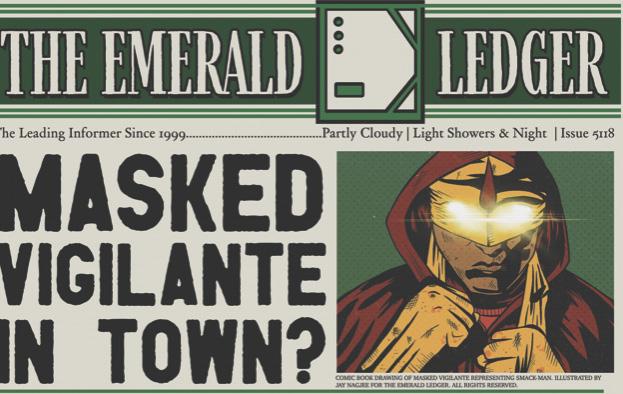

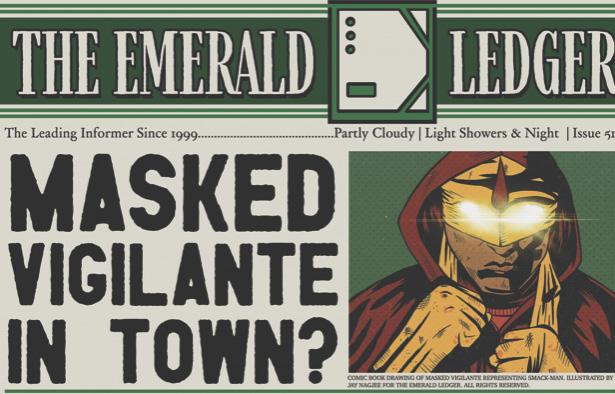

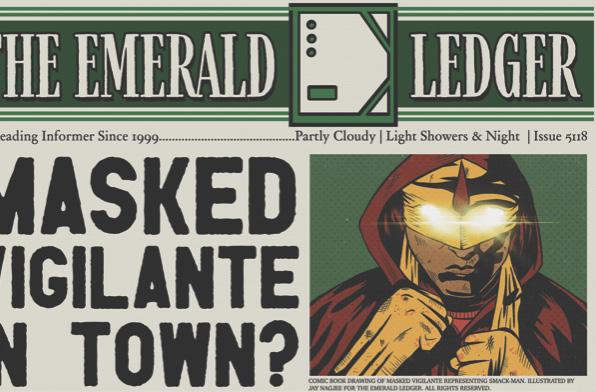

In the BFA thesis film Smack-Man: Resurrected (2022), the protagonist, an Indian man named Roy Rao (played by Bhanu Gopal), takes on the identity of his favorite comic book superhero, Smack-Man, to stop the violent acts of the Dotbusters, a racist hate group. While is a symbol of such exemplary traits and ideals, the creator/writer and director, Jay Nagjee, is that stupendous superhero in real life. Nagjee graduates from Emerson College this semester, but he has left a trail that will blaze for long after, inspiring those around him. The following are excerpts from our two-hour discussion/interview on Zoom.

Was there something specific that made you want to start filmmaking?

NAGJEE: There were a couple of things. The biggest catalyst was theater. One day, I was casted as this farmer and somehow I didn’t feel like a farmer – [maybe] because I was too

young, but I thought, I’ll make a mustache. So I got a haircut and I collected my hair. Even though it sounds kind of gross – but whatever, you’re a kid – I cut a piece of doublesided tape and super-glued the hair into the shape of a mustache. That’s the first time I remember creating a story in my head and trying to play a character… I love stories; my father would tell me stories so I could go to sleep! I also loved action figures, wrestling, Spider-Man, and other superheroes; I used to come home, dress up as something, and then just play around the house. This idea of becoming some character has always been part of me, since I was a kid… and all these things built up leading me into always choosing the side of the arts in school.

How has your time at Emerson helped you as a filmmaker?

NAGJEE: I think the biggest misconception of film school, in my opinion, is that film school teaches you how to make movies. Film school is something that’s like balance: you can’t learn how to ride a bike by reading a book, you need to ride the bike itself. With that being said, I think the biggest thing about Emerson College that differentiates it from other schools is its culture: how much people push themselves to make films outside of classes… I think getting into that culture has taught me the most about film. I was very lucky to be in a dorm full of people [who were] so passionate about film. Film school allows you to practice them and fall in love with them. I think it’s more of a hub and a “network area” to do that: to take advantage of that situation.

Absolutely, it’s really what you make of it. NAGJEE: Yeah, 100%.

What would you say is the project, or projects, you’re most proud of making during your time at Emerson?

NAGJEE: So, COVID hit and [Emerson College] said everyone’s got to move out… everything [became] remote. I didn’t want to work in film school so I took a gap year. I watched a movie a day in quarantine, and then I wrote and directed two short films as things loosened up and the restrictions lifted. I wrote and directed a Spaghetti Western short called They Call Him… Charlie Sombrero (2020), and I co-wrote and directed a crime drama called The Wolf Pack (2021). Those two shaped my entire ideology of directing–of working with actors and putting a film together because I produced, edited, did the production design, and it was the biggest learning experience that I ever had. Apart from working on those two films, I came back to film school after the gap year and applied the idea of Smack-Man: Resurrected for [the Bachelor of Fine Arts degree program]. It’s a 30-min superhero short film and it’s my third proper short that I’ve written and directed, and honestly if I hadn’t done The Wolf Pack and They Call Him… Charlie Sombrero in my gap year, I don’t think Smack-Man would be the way it is. I think each film has improved me more and more as a writer, director, and creative!

Could you talk a little more about SmackMan: Resurrected? Can you share the creative/development process and how it’s based on true events?

NAGJEE: So Smack-Man came to me when I was in a sociology class that I had to take because of the liberal arts requirement. I was trying to think of movies that I like and wanted to talk about. Well, I also wanted to pitch to [Emerson Independent Video]... something about me, as an Indian, coming to the U.S. and experiencing racism. I was thinking of a time when I was younger: I moved from a predominantly South Asian school in Dubai to an international school when I was around 10 years old. I had a very thick accent and there was this kid that came out of a class one day. He sniffed around and he said, “Smells like shit – must have been the Indians.” Then he just walks out… ever since then, I made sure that I didn’t have Indian food in my lunch box because of the pungent smell that people made fun of. I imagined being a superhero in my head and punching that guy, but I didn’t want to do that, I’m pretty much a pacifist. So I was thinking, why don’t I make a film that reasons with that pain, that I still have inside, to resolve that feeling? “Racism against Indians in the United States” is what I searched up in that [sociology] class, and I found out that there’s this group called the Dotbusters. They’re named the Dotbusters because bindis are religious symbols South Asian women wear on their heads, and I realized, there’s barely any research on them! I was thinking, what if I take these ideas that I had of me as a kid facing some form of prejudice and turn it into

a film about this person, who represents me, taking the Dotbusters down?

I wanted my protagonist to be inspired by his favorite superhero, instead of him being the original superhero itself. I was attracted to the idea of him being a fan of a comic and trying to be a vigilante. So I made a comic book called ‘Smack-Man,’ translated from Hindi, which is Thapadmaan. The superhero is my own character, based off of a very famous and very campy Indian superhero TV show called Shaktimaan, meaning ‘strength’ or ‘strong man.’ We were actually filming this in 2019 but COVID happened and Smack-Man ended up being shelved until I thoroughly redrafted, edited, and brought it back to life –“resurrected” it – for the BFA. And now here we are with a film that’s been in development for three years!

On Smack-Man, I was an associate producer and the script supervisor, so I’ve been able to witness your directorial approach throughout various stages of production. What does it take to be a director? In your opinion, what’s good directing and bad directing?

NAGJEE: Oh, God! I don’t – Hmmm… I’m trying to be a good director every day. I don’t think I’m fully there yet because every time I do something I notice, like “I could have done that better” or “I could have done this better.” Honestly, the biggest and best gift that I have received is being allowed to create a space where people feel comfortable to talk to me. I always want to know what people think; I want to talk to everyone and I want to know the thoughts of someone who wasn’t even in the room and just heard the