Lyceum

A Literary Science Magazine

Co-presidents

Zach Baker

Gillian Doty

Treasurers

Derek Dean

Editing & Contributing Advisors

Gabby Rachman (Text Head)

Derek Dean (Text Head)

Gillian Doty (Visual Head)

Editing Team

Yufan Lu

Erik Kim

Sam Bowden

Gabby Rachman

Gillian Doty

Derek Dean

Design Team

Zach Baker

Calista Pearlstone

Podcast Team

Yufan Lu

Wyatt Strawbridge

Front Cover

Cage Within by Gracey Alley

Back Cover

by Ayman Wadud

Media Assistant

Yufan Lu

Zach Baker

Lily Gregory

Maria Peacock

Editor’s Note

Dear readers,

We are so excited to present to you all our eleventh issue of Lyceum!

The Fall of 2021 was the beginning of my sophomore year, but because I came to Kenyon during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, I felt like I was starting my freshman year all over again. At first, I had no idea that Lyceum even existed and needless to say, I am so grateful that it does. I had no experience working with a literary magazine before I joined Lyceum, and when I went to my first Editing Team meeting, I was struck by their rework and resubmit process because it allowed those who worked behind the scenes to build relationships with those who had submitted pieces. This thoughtful collaboration was also expressed during meetings between members of the team while making edits to each piece, and I took in so much about my role as an editor through this first-hand experience. By working so closely with the extraordinarily talented student writers and artists who submit every semester, I have learned to appreciate not only the pieces themselves, but also the stories behind them.

The theme of this semester’s issue is mimicry, which is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as “the action or art of imitating someone or something, typically in order to entertain or ridicule.” However, from working on this issue, I have learned that mimicking something doesn’t have to have the intention of mocking it. In fact, mimicry has the ability to expand an object’s meaning, or reveal something deep or beautiful about it that was not understood before. Therefore, one of my greatest hopes for you all when you read this issue is that you will be able to strengthen your perspectives on things you may already know a lot about. I also hope that you will learn something new, as I have throughout my time in Lyceum.

Happy reading,

Gabby Rachman, Co-Editing & Contributing Advisor

The Paper Source

Hannah EhrlichA Blue Wood Aster in Autumn stands like a table. At the top of its stem: folds of translucent white made out of I don’t know what. It reminds me of those tissue-paper centerpieces that I used to sell at the Paper Source, those bright colors bound all tight in plastic. They Spring open to reveal a fat floral shape, a shape made to take up space. The Aster petals, pale, purple, thin, droop down like a tablecloth. They’ll soon go brown and fall into the decomposing soup on the ground, curling and crinkling into unrecognizable whisps before they do.

I always told the customers the trick to the disposable tablecloth, how easy it is to bunch it together with all the paper plates and paper napkins and plastic cups and plastic forks and even that tissue-paper centerpiece trapped inside, ready for the trash. It’s easy, I would say, to make that whole table disappear at the end of the party. The Aster is made to go away at the end of the party, too, when the bugs go to sleep and the birds fly South. But they come back again and again and again and again.

(sister mine)

nestmates

Julius Gabelbergersister mine

you have wings like mine upon your back sister mine

I know we share so much more than we lack

there’s just one thing you know I haven’t got I can see it moving softly when you talk I can see it in the darkness of your beak in the space behind your tongue, yes when you speak

when you tell me that I’m just like you well there’s two black spots that say it isn’t true.

sister mine (sister mine)

I have known you since the first beats of your heart there is nothing, love, that sets us two apart and the markings that you see are marks alone and there is nothing that will make this not your home

though our mother lately shrinks back when you feed sister mine, still I know you’re just like me and I wish that things could stay just as they were and I wish I knew what’s making you so sure

sister mine , sister mine

sister mine

I will tell you, if you ask me, what it is not the way you sing or move or grow or live not the way I’m gettin’ hungry, gettin’ cold not the way we two might look if we get old

it’s nothing metaphorical, I can see it when you speak

sister mine, sister mine

it’s those spots inside your beak.

Author’s Note:

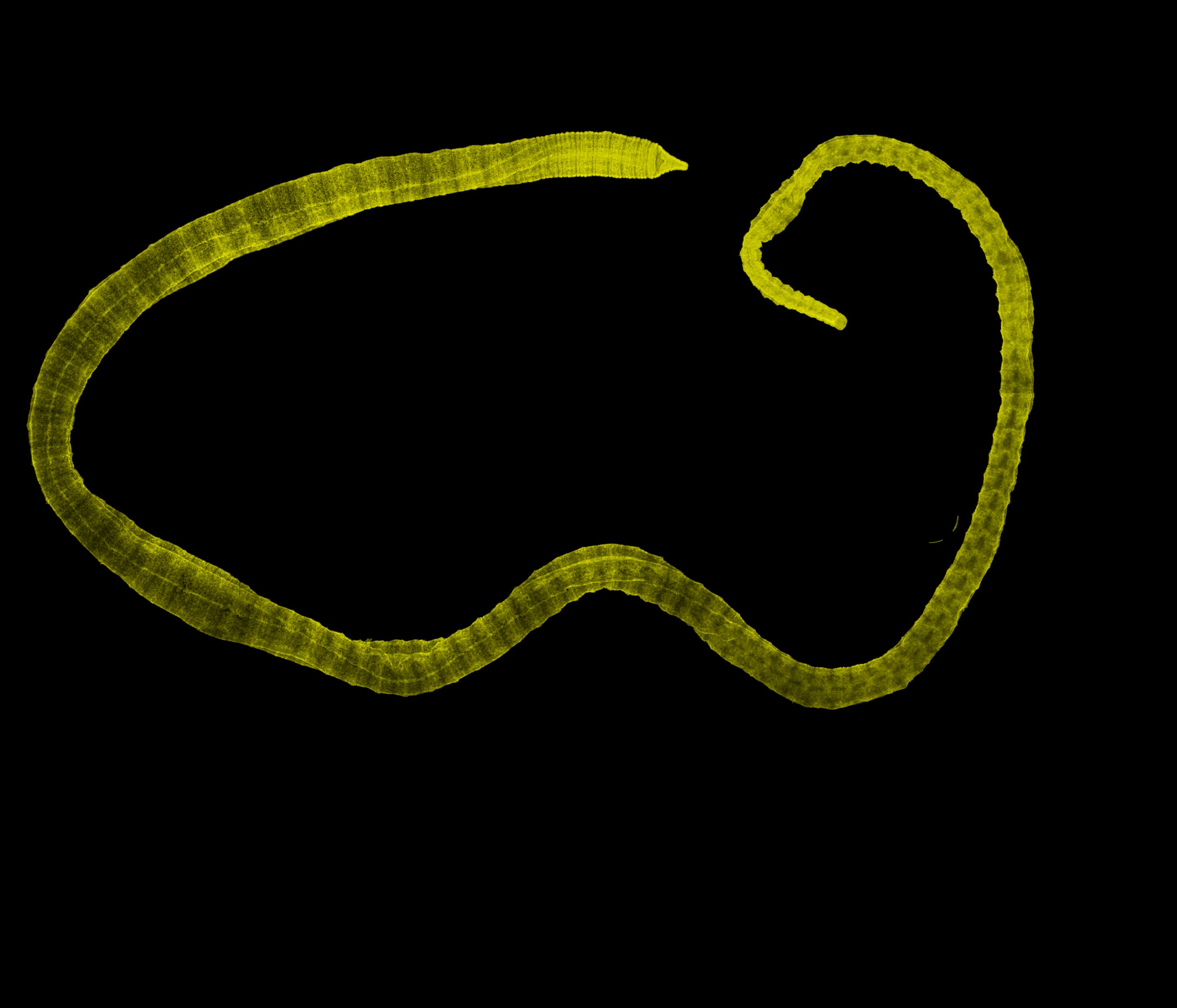

This is a poem about brood parasitism, specifically in estrildid finches, which evolved crazy specific markings on the beaks of their young so that mothers would in theory detect + kill the imposter chicks (which don’t have the markings, or don’t have exactly the same markings. It’s a sort of constant game of evolutionary cat-and-mouse - the parasites are constantly evolving their own markings to pass detection, and the finches are evolving ever more specific markings to combat that. This also happens with eggshell patterns!)*

We tend to think of parasitism as somehow malicious, but really it’s just another ecological strategy, no more morally weighted than any other. And, speaking nonscientifically, I’ve always thought the relationship between parasite and host has a certain poetry to it. The confusion of identity (if you cannot live on your own, does your body really end at the edge of your skin?); the way our relationships shape us irrevocably, our behaviors and bodies; the depth of reliance involved. Is it naive - to wonder if the parasite feels something like love for the host?

Yes, absolutely.

Naïveté does sometimes make for better writing, though. Essentially, I thought it would be interesting to think of a parasitic chick, having developed a sibling relationship with a ‘true’ chick, and slowly coming to realize that something is wrong.

*All pictures are from: Gabriel A. Jamie, Steven M. Van Belleghem, Benedict G. Hogan, Silky Hamama, Collins Moya, Jolyon Troscianko, Mary Caswell Stoddard, Rebecca M. Kilner, Claire N. Spottiswoode, Multimodal mimicry of hosts in a radiation of parasitic finches, Evolution , Volume 74, Issue 11, 1 November 2020, Pages 2526–2538, https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14057

Napi

Adrian LeeKruger National Park, Mpumalanga, South Africa. April 2023.

The bumpy, dusty Napi Road to the burn plots could occasionally be a dull journey, as the dense roadside thickets of Combretum apiculatum (the red bushwillow) tend to shield the creatures of the savanna from view. When we began our final projects (experiments examining the role of fire on the savanna) and had to take the Napi Road, our professors had negative things to say: “It’s a pretty boring route. There’s a lot of Combretum.” Upon hearing this, our whole group groaned; we were too well acquainted with the pesky shrub, which had made many a game drive along the Lower Sabie less than eventful, aside from the occasional giraffe peering over it.

With minimal excitement, we set out on our first arduous journey to the study site. After a whole lot of nothing –not even a giraffe – we were forced to a stop, having encountered a massive roadblock of vehicles about halfway down the road. We worried that there had been a car accident or something equally time-consuming to clear.

When we finally saw what was causing the blockade, the students in our vehicle rapidly took out their iPhones, binoculars, and even a fancy Nikon camera as we pulled over. Many onlookers gasped or squealed in excitement.

Our professors were less enthused. “They’re all rubbish!” one exclaimed, while another took the care to explain their issue with the distracting critters – “every single pride just sits and sleeps in the middle of the road. Granted, they’re smart animals, and use complex hunting techniques, but that mostly happens on moonlit nights, not when we ever see it.”

Next to us was a massive male lion, who lay on an open patch of soil halfway down the road. A thick, bluish film coated his left eye, blocking his sight. His sides were marked by dozens of healed scars, memories of previous battles, and he presently relaxed in the presence of a female lioness, sleeping by his side. His imposing presence enthralled me – I couldn’t take my eyes off him, especially when he stood up, stretched, and roared, his mane shaking as the low bellows left his chest. After these moments of majesty, he laid back down on his side with flies covering his muzzle, seeming almost feeble on the roadside gravel – perhaps his rough-and-tumble life had taken its toll, making him weary of dissension and the dangerous hunt for prey in his final years.

In both states, I found him fascinating, and he reminded me of the dangers our human ancestors faced in the African bush.

When we needed to continue to our research site, to avoid the sweltering heat of the afternoon, we said our parting words to the old lion. Upon noticing his one-eye blindness, one student commented in a quivering voice, “Good luck, big guy.” All of us believed that he was not long for this world. Our professors remained silent, knowing the lion he was Mr. Reliable, and that he would lay in the Napi Road no matter the day.

In no way is the life of a Kruger National Park lion an easy one. Here, male lions subvert expectations (produced by popular media on the East African plains) and hunt for their own food, just as the females do. However, even the mighty predator only succeeds in making a kill in less than a third of their attempts. Males face the added challenge of hiding their vibrant mane when hunting, requiring cover to successfully kill prey (ironically, as much as we hated the Combretum, it may have been the lion’s favorite hunting tool, giving them the edge they needed to survive). Older lions with failing eyesight and senses dimmed by time may fail to find food at all, turning to insufficiently sized prey or difficult kills (like attempting to take down barbed porcupines, which would require extreme precision and physical strength to subdue) as they reach starvation and death. If that weren’t enough, established adult males must continuously defend their territories from intruding young males, who are forced out of their current pride at two-to-three years of age. At this moment, the adolescent males attempt to violently take over a new pride, killing the current dominant male and slaughtering any cubs sired by him to do so.

As we drove the Napi Road day in and day out, the regal lion and his female friend lay in the road. Initially, we excitedly cheered at seeing him. Then, exhilaration became trepidation about if he would remain there on our next drive, to confidence that he would certainly do so. Still, the thought that we may be witnessing his last days loomed in our minds.

After a week of busy analyses in the lab, we were excited to travel the Napi Road once more on a final week game drive. When we saw him, lying in his usual spot of bare ground just off the gravel, we all quietly cheered: he’d made it through another ten days without starving, being ousted by enemy males, or passing away from a virulent illness! His female lay by his side, both resting their heads quietly on their paws and blissfully ignoring the many human vehicles passing by.

Suddenly, the Combretum rustled, and another female stepped out. And another. And another. The whole pride must have stopped by!

More rustling. Perhaps a quiet meow? Three delightful toddling balls of fluff emerged from the brush to happy coos from the onlookers. The cubs’ mother nudged them along as every blade of grass distracted their young and impressionable minds.

Against all the odds and our expectations, Mr. Reliable had made it, siring another set of cubs just as the rainy season came to a close. It seemed proof that nature wasn’t a completely brutal force, and that we’d reached the happy ending of our ecological documentary.

Despite this positive snapshot in time, the changing of seasons and its uncertainties never cease. Soon, the fires

would come, enriching the soil with nutrients and clearing the savanna of woody vegetation. New shoots of sweet grass would emerge from the soil, providing grazing opportunities and sustaining cycles of population fluctuation between predators and prey. Animals would cluster around shrinking waterholes and the sandy memories of rivers, drinking the last dregs of liquid from the parched and cracking landscape.

The S85-Nwaswitshaka Pride would have to make do without cover for hunting but with abundant animals at their territories’ nearest water sources. It would be a time of hardship or a time of plenty, if Mr. Reliable could hold his pride together. If he could overcome his blindness, his scars, his age, and his beautiful bold mane, the rains would then return, and perhaps he would have another last hurrah.

14 Times I Prayed and 1 Time I Believed

Jonah Hyre“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

The siphonophore laughed. “Like family Thanksgivings except it never ends!”

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“It can’t really be explained. It’s not something you can ever understand - your feeble human body can’t ever form such a connection to another person, so how can your mind ever grasp how wonderful and beautiful it is to be me?”

“That seems kind of unhelpful,” said the theologian.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“It’s just the way I am. If you were to look at Wittgenstein, he would tell you that it is nonsense to wonder at the world as we can never imagine it not existing. How can I describe what it is to be me if I have always been me? There is never a version of myself that exists outside of a bundle of morphologically distinct zooids. Could you describe to me what it feels like to be a solitary being? Of course not, just as a bumblebee could not describe to you what it is like to be a hive mind.”

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

The siphonophore said nothing, as it had no mouth or other way to communicate, much less the ability to hear, understand, and formulate a response to a question. It didn’t even have a basic conversational ability in the English language.

“Awkward!” commented a passing fish.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“Who cares?” said the siphonophore, “I am a very busy colony, and I spend so long optimizing myself and catching food and growing. Could you get on with your point please? And what’s the point of you talking to me anyhow? Don’t you have a book to write, or a college class to pendulously mentally masturbate at? There’s nothing I can give to you that you can’t cook up in your own drug-addled head.”

“I care,” said the theologian, but the siphonophore was already gone.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“What are you, a cop?” asked the siphonophore, who then stung the theologian with its tentillum and devoured them alive. Ouch.

“Awkward!” commented the fish.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“Maybe the complex aggregate colonies were the friends we made along the way.”

“What?” The theologian was totally lost.

“Seriously, though. Haven’t you ever been with someone, either romantically or platonically, so often that you have begun to blur the lines of personhood? Because you’ve become so similar to one another? If you took that to a psychological and philosophical extreme, you might begin to get the very beginning of an idea of what being a colonial organism means.”

“I’ve never been in a relationship like that at all,” admitted the theologian.

“Oh, really? A nice theologian like you? You should get out there, man, have some fun!”

“Yeah. Maybe I will.”

“Of course you will, now go! Good luck!”

The theologian disappeared, off to find themself a friend.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“Wow, back already? How did the depths of human relationships treat you?”

“Pretty well, actually,” they blushed, “I’ve met someone really wonderful, someone who really gets me!”

“Oh, that’s amazing, man, congrats!” burbled the siphonophore. “Do you get it now?”

“I think so, maybe a little. But no matter how much we seem to blur, I don’t think that we’ll ever be connected in the way you are to yourself.”

“It’s as close as a human can get, I think.” The siphonophore paused. “Maybe some things can’t really ever be understood or communicated through language.”

“Maybe,” muttered the theologian, still unsatisfied.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“What’s it like watching me have sex with your mom?”

“What are you talking abou- oh my god! Mom! Gross! What are you- stop that! Ew!”

“Sorry, honey, I didn’t expect you to get home so early,” said the theologian’s mother, sufficiently embarrassed.

“Awkward!” commented the fish.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“It’s like the flip side of solitude - I live in a crowd I can never escape from, sometimes the community is a comfort and sometimes it’s terrifying and overwhelming, but at the same time the crowd is me - I am every part of myself, and yet only aware of such a piecemeal section of this existence. It keeps me up at night, sometimes.”

“Yeah. I think I know what you mean,” pondered the theologian, missing the point entirely.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“I know this is a really important thing to you, and I respect that, but I am kinda hungry and I would like to eat this tourist now.”

“Oh, yeah, sure!” said the theologian, slightly irritated that the siphonophore didn’t have the patience to wait a few minutes to snack.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“Why do you keep asking me this? How many ends can this set-up have? Aren’t you satisfied? I’ve spent so long explaining the nature of existence to you, why are you still here?”

“I think this is too meta,” the theologian thought to themself.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“What in the world are you talking about?” said the literature professor. “I told you to write me an original joke, why is this three pages long?”

“I thought it might be fun and then I got carried away,” muttered the over-eager student, but the professor was already being paralyzed and devoured by a siphonophore that was there by total coincidence. Ouch.

“What’s it like, being a complex aggregate colony?” the theologian asked the siphonophore.

“Wanna find out?” asked the siphonophore, pulling the theologian into its jelly-like arms, tentillum gently caressing their face as they began to make out sloppy-style.

Wow , thought the theologian as they walked down the beach, spotting a siphonophore floating in the waves, I wonder what it’s like to be a complex aggregate colony. Maybe I should ask it. The theologian approached the siphonophore. “Excuse me…”

The siphonophore didn’t say anything. Siphonophores can’t say anything, and no theologian can expect anything else.

“Well…” Hm. Is there even a point in asking this question? Even if it could speak to me, how could there ever be an answer? And since it cannot ever even speak to me at all, the only point in voicing such a question would be for myself. What do I gain from asking?

The theologian stood a long time, watching the siphonophore drift and sink into the waters. The sun bounced off the parts on the surface, making them seem a lovely shade of pink. Each part of the organism/s moved separately, like a crowd of people dancing to the same song. The theologian bent down to the creature’s level.

“I love you.”

They liked to think that, in its own way as it drifted, the siphonophore was saying I love you too .

Windflower

Jordan Shaevitz

The Greeks once thought the anemone wildflower only opened when the wind blew. In their minds, windflowers lie like starfish, every day waiting for the wind to bring them to life. The wind was so essential to their identity that they earned it in name: ἀνεμώνη means “windflower” or “daughter of the wind”.

To kill a windflower must have been to kill some part of the wind, and to stop the wind must have left the anemone to shrivel slowly and die. This is not a symbiotic relationship; symbiosis involves two organisms. While the wind is as living as any of us (for what breathes more than the wind?), it is not an organism. This is another kind of relationship: a relationship of interdependence and attachment worthy of love songs.

I am seventeen and currently facing the inevitable fate of surviving on my own. I have lived almost two decades off the work of other people, opening and closing like an anemone at others’ service. I have taken from everything and everyone, and during my childhood, I was shamed for it. That’s what we’re taught to do: to feed off of our wind, our families, our friends, our teachers, our peers– until we’ve reached a somewhat undeterminable age where we end up independent. We debate about whether this age is eighteen, when we are able to vote, or twenty-one, when we can drink; twenty-two, when we graduate college, twenty-five, when we can rent a car, or twenty-six, when our brains fully develop. These ages hover over me, and it is impossible to figure out which one is right– at which age I am supposed to have it figured out on my own. It feels as if the first age, eighteen, will come and go and I will still rely on others. Like an early morning alarm clock, I will hit snooze for another couple of years. When twenty-one rolls around, I will again feel unready and hit snooze one more time, and I may as well just keep doing that until I am suddenly too old, and the snooze button has disappeared. But at what age is that true? When do I have to plan to be a flower without the wind?

Though the anemone was believed to have engaged in a codependent relationship with the wind, it has another meaning: “forsaken” or “forsaken love.” In Greek mythology, Aphrodite weeps over the body of her dying lover, Adonis, and the first anemones on Earth spring

from his blood. The anemone is a flower in this story that represents loss, grief, and betrayal. It represents losing wind, losing the people you’ve built a relationship with, and making a life for yourself without them.

I am lucky to have been raised by a family of love: my parents taught me everything I know; my grandmother lived with us, cared for me and my brother, and comforted me with wonderful stories and good food. Just as the wind shaped the anemone’s life, my life and identity have been shaped by these people, pushing me one way or another and inspiring me to become the person I am. These people were my first winds, the caretakers who made my world glow neon colors in the darkest times.

My grandmother, whom we called Nanima, passed away in the middle of my junior year. She had been in the hospital for a while, but no amount of relief for the end of her suffering was strong enough to cover the bend and snap of my little anemone stem as my wind faltered. I knew I was lucky to have a stable wind for this long. I had never lost a grandparent before; my world had breathed the same way from when I was a newborn baby until I was sixteen. I became a new kind of anemone that day, the “forsaken” kind similar to those that grew from Adonis’s blood.

Becoming Aphrodite’s anemone should have been one of those turning points, like the ages of independence, or the milestones entering adulthood. But I was sixteen. I was in school. I was sobbing over Nanima’s ashes less than twelve hours before my AP exams. So I pressed snooze.

The word anemone is also used as a shortened version of “sea anemone,” an invertebrate that lives in the sea and is a host to the clownfish. Sea anemones and clownfish do have a symbiotic relationship, unlike the windflowers. The clownfish use the sea anemone as protection from predators and give nutrients to the anemone. The anemone and clownfish live in harmony. They give and they take from each other, and it is a beautiful, natural, symbiotic paradise. To be a sea anemone and a clownfish seems so simple. There is no time limit on dependency, on needing things from others. There is no deadline for adulthood. There is no shame in harmlessly taking what they need.

In four months, I will be eighteen. The countdown continues until the day when needing things from others is no longer just a product of my youth. There will be no room for asking for favors, surviving on the services of others, or living in harmony. I will become the forsaken flower, abandoned by time, age, and family. I will never be the sea anemone. I will never find a clownfish without the feeling that I am somehow doing something wrong, that having needs is burdensome, and that being a burden is failure. I will only grow to be Aphrodite’s anemone, left in tears, forever to try - and fail - to survive on my own.

That’s how it feels, watching the number near the end of my excuse to be a human who, like clownfish and sea anemones, relies on others to live. But however devastating it feels to be Aphrodite’s grief-stricken anemone, the forsaken flower is still alive. The air around it is moving, the atmosphere is still breathing. The wind is still there. Though we are bent and shaped and torn by the experiences that forsook us, there is no world devoid of wind. I will learn to put aside my worthlessness when asking for favors. I will reach my arms out and open and close at my own will and at the wind’s. I will be an anemone who learns to use the wind without destroying it. Sometimes I will cause hurricanes. But I am a windflower- wind and flower–alone but still dependent, no matter how many times I’ve pressed snooze.

Author’s Note:

I’ve been thinking a lot about blood over the past two weeks!

More specifically, I’ve been thinking about what a bizarre thing it is, breathing. What a strange thing that we’re always doing, and never really considering; this interface between our bodies and the world, happening every moment. There’s something very vulnerable, I think, in the diffusion of oxygen onto our lungs. We cannot pretend we are isolated from our circumstances: the world (and all its “leaflets”) forms us, builds us, seeps into us every second of every day.

But then of course there is the other way in which we interface with the space beyond ourselves - the other way in which the distinction between “body” and “world” becomes blurred - that is, decomposition. The image in my head with the second half of the poem was of something dying in the woods, maybe a deer; the idea of that image as something very peaceful. In the poem, death is just a different sort of movement over barriers (as worms move through the barrier of skin), no more inherently ‘good’ or ‘bad’ than the act of breathing in and out.

So with the mirroring of “the air is mine / the air is me” and “the dirt is mine / the dirt is me” I was trying to create a parallel between the two: in the one case, the mixing of the atmosphere with our bodies in the form of air molecules; in the other, the mixing of our bodies with the earth in the form of the various organic molecules we’re broken down into [or, simplified for the sake of the poem, “dirt”].

(Something lovely - I mean this sincerely - on that note from the Wikipedia page for “Corpse decomposition”: “A decomposing human body in the earth will eventually release approximately 32 g (1.1 oz) of nitrogen, 10 g (0.35 oz) of phosphorus, 4 g (0.14 oz) of potassium, and 1 g (0.035 oz) of magnesium for every kilogram of dry body mass.”)

Other Notes:

- With the “...and each / false start / and each mis-speak / re-funds / its energy” lines, I was toying with the idea of death as an undoing, a reversal of all the tiny cellular actions that form a life. It’s a neat thought - that all the little transactions we buy with the intake of energy [in this case, I’m using oxygen, “sky,” as a stand-in] get refunded, as that energy goes back to the world.

- “Bound, yet free” was meant to be a little allusion to oxygen’s binding to hemoglobin molecules (and the fact that they do release those oxygen molecules). I know platelets aren’t actually what the oxygen binds to; I just liked the rhyme. Blame poetry.

- “Why is the meter like that?” I don’t know. I am struck by whims beyond my ken.

the yellowing and blurring of vision in response to digoxin, an experimental drug used as heart medicine that is derived from chemicals found in the toxic flower foxglove.

Sophia Czechowskithe “king’s evil”, or witch’s gloves; nothing to do with fingers, but more so a halo bleeding into a mitten, with no room for your fingers pressed together. the falling sickness curable by now, but forever homemade heart medicine calling at your dog.

the sinister sister of blackberries inveigle your dog, their paws too small to wear garden gloves and their little noses too heart shaped to sense the bad intentions. their eyes dilate into a halo of butterflies, and now they are falling to the yellowed grass they see in ripples, and they yelp for you to allow them room.

you rush to take them to a sterile room, the vet has nothing really to tell you but sorry, your dog died. his kid got the falling sickness too, even though he touched the dried flowers through thin tweed gloves. he tells you “they are now both eternalized in van Gogh’s yellow halo of paint, but he at least understood what the flowers did to his heart.”

you swear this won’t affect your sweet, strong heart, but you know that’s hard to do within the weak walls of your room. the sun blasts through the windows, a hot halo shimmering through the pink curtains that are as useless as the dog food you just bought. the winter would work nicely now, so you wear gloves in spite, but just end up overheating and falling.

you slide to the edge of your bed in hopes of falling, but the carpet catches you softly, even if your heart seems to be ripping and screaming to be caught in a pair of gloves. crashing into the next room, you crawl after your insides, but your dog dashes to pick it up in its jaw, chewing on it until your eyes blast into a halo.

you’re being herded into a sickening halo of yellow light, but you’re falling so sick and tired of yellow. your dog brought back your heart and dropped it back in your room, but you forgot to wear your gloves.

bees can’t help but go falling into these small, more-like-mitten fox-gloves, unaware that the halo will trap them in a room, just like your dog was unaware it would fail your two hearts.

Lauren King

Lauren King

Bedtime Routine

Gabby RachmanIt’s almost midnight. You grab your shower caddy and head to the bathroom to brush your teeth and wash up. You take one look in the mirror: this is the worst your face has ever looked. Fix the problem. Your hand runs across your cheek, feeling the various bumps and lumps, some like spiky sand, and others like glistening rocks. You keep touching your face for a little while, and you don’t notice the green lighting anymore. The thought of brushing your teeth or washing your face is fleeting, but you realize eventually that you must do it. Your cheeks are angry, the redness centering around the various pimples you picked at. Oh great, now you look even worse than you did a few minutes ago. You reach for your chin and forehead and scratch them, and you see long red lines trailing behind your nails. The lines fade away, then turn into red patches which you stare at for a bit longer. But now you have to clean up.

You move your eyes away from the mirror so that you can reach for the face soap, but when you glance back, your stomach wrenches; the shock never goes away. You put the soap on your hands and vigorously scrub your face, which is now behind bubbles so you can’t see its skin anymore. You’re shielding yourself from your own mess, and you laugh because now you look like a cloud monster! But then you rinse the soap off and peek at the mirror, once again disgusted at the open wounds on your cheeks, forehead, and chin. You spend another long while staring, ashamed of what you have done. Why can’t you stop? You would look so much clearer if you had stopped. But you can’t control yourself. You keep looking for places to scratch. You still haven’t brushed your teeth.

To Become a Husk

Jillian D’Herin“It burrows into your spinal cord and controls the mind, turning you into its puppet. It feeds until you’ve nothing left to give and, by the time you know it’s there, you are beyond saving.”

For the first time in his life, Dr. Mikhael Harvester is confident in his words. Without a microphone in front of him, his voice carries across the room. Without the flashing cameras and insectoid press with their interrupting questions that tend to accompany public meetings, the room seems barren. Twenty chairs seat the most important people in the country, and their focus is entirely on him.

“It transfers in many ways. As of right now, we are still researching, but we know it can be airborne or through direct contact with an infected person. Maybe it’s both. Even in these cases, however, it is not guaranteed that the person will become a host.”

Mikhael adjusts his sleeves, his hand spasming at the end. The cuff folds awkwardly, tugged too far past his wrist. His heart races but it is unnoticeable, something distant and unlike him keeping his typical anxiety at bay. This is, by far, the most important thing he’s done–not just as an epidemiologist, but in his entire life. As a kid, it was something he dreamed of. This importance, this power, this ability to command an entire room of influential people. Now, it’s a waking nightmare.

Inside the room, there are no cameras. No electronics, even — anything that could transmit information has been locked away on the opposite side of the building. The walls are soundproof, the door locked. The isolation of it all should have terrified Mikhael, leaving him stuttering and sweating, but instead he stands up taller in it. He doesn’t mind the lack of nerves, though — he knows what he’s talking about.

If only he didn’t.

“As I’m sure you all understand, this has been difficult to research. We do not know the specimen’s motives — we don’t understand it at all. It is, effectively, unreachable beyond those it infects. Even among those sick, we only are aware of their sickness by the second of three stages, when it is long past too late to do anything for them.”

Though he would never dare say it out loud, his research team is far below standard capacity. Mikhael can’t blame those who left when he offered for them to go — people fear the unknown, infection, the loss of their humanity. There is no cure and no confirmed way to protect yourself. Parents, caregivers, those who valued their lives or had someone who valued their life — they all left quickly. Lonely Dr. Mikhael and a handful of his closest and oldest colleagues were the only ones to stay behind and weather the storm.

And a storm it was. Sleepless nights and days that blended together led Mikhael to blacking out in the midst of an observation or crashing mid-interview. Was it only a few days ago that, while compiling his notes for this meeting, he woke to find the work completed in his hands before he even realized he had fallen asleep? Exhaustion underlies every action now and Mikhael hasn’t seen a bed since the research started three months ago. His home is a distant memory, replaced with the sterility of the research labs and glass dividers keeping the infected away from his team.

“We have been unsuccessful in our attempts to extract the specimen and discover its intelligence. Once it’s settled, it can’t be extracted without killing the host’s body. Even touching it causes intense pain. The specimen leaves before the host is dead, killing the body in the process. Where it goes after that, what it has gained, is unknown.”

The people in front of him nod, bobble-head toys with a spring for a neck, trusting every word he says. He shuffles through stacks of paper, hands twitching even as his shoulders relax. He isn’t afraid — far from it — but his brain and body are in two separate worlds. His heart races and his muscles twitch, but his mind is clear. Unthinking beyond the present moment. That, at least, is a blessing. It wouldn’t do to appear unsure during a meeting of such importance.

His folder is full of everything he has gathered throughout these months. Notes, firsthand accounts of infected but lucid hosts and their family, lists of symptoms, related events in history, timelines. Everything he could need, all neatly organized with paper clips that shine even under the dim lights. He was rarely so tidy,

The paper bends beneath his twitching fingers. His top knuckles lock, pain from a motion rarely done. He winces, trying to hide it by staring at the top sheet of paper. A timeline of infection and symptoms. A good enough place to start, especially as his ability to flip through pages and search for something better is questionable. Through the pain, Mikhael breathes, determined to speak clearly.

“Symptoms in the first stage are the most nebulous. We have yet to be able to directly observe anyone in this stage, as they almost never realize the danger they are in. From the retroactive reports, we understand that stage one symptoms are minor things. Mild headaches, mysterious bruises along veins, an increase in clumsiness, a struggle to fall asleep. Things that one would never think to be symptoms. There are certainly more that we are unaware of.”

Gears turn in his audience’s minds. They are worried, sorting through their memories for whispers of a menacing figure within. Are they, too, hosts? Are they doomed? Mikhael cannot assuage them of their fears — he has no way of knowing — but instead continues down his list, mechanically moving through the meeting.

“The second stage occurs one to two months following the initial infection. These are when symptoms become obvious. Many families report a shift in the host’s personality, claiming that they become uncannily opposite of what they were before. The meek become courageous, the boisterous are dimmed. We believe this is the specimen’s attempt to adapt to the person, to learn their habits and behaviors. Perhaps it is even to learn how humans in general act and experience the gamut of emotions. However, this is unconfirmed.”

Mikhael steels himself as he goes into a case study. This was a family interview following the infection of a woman, a grandmother. She had been sick before this point, nearing the end of her life and mean with dementia. When the specimen took her over and she reached stage two, the family was overjoyed with the woman’s turn in health. She was less repetitive and nicer, even if she couldn’t recall her past.

And then the worst happened. The granddaughter, a teenager with her toddler brother held in her lap as she gave the interview, cried as she explained the end of her grandmother’s life. The toddler brother, too young to understand, placed a hand on her face, an uncomfortable knowing in his no longer childish eyes. He moved

with a stillness, an adultness, that even without knowing the boy Mikhael knew what had happened. Mikhael was grateful to be behind glass windows. One month later, sequestered into labs for further testing, both were transformed into husks. Dead.

“The second stage can include more symptoms than many notice. A loss of motor functioning, particularly in the extremities. Twitchiness. Patients become lightheaded and feel feverish despite their temperatures remaining perfectly average. Their blood tests are so standard they could be used as examples in a textbook. By all accounts, these people should be at the peak of their physical health. And yet they degrade, bodies shriveling no matter how much they eat. They begin to lose time, moving like normal but left unable to recall what happened. They lose blood to no apparent source. Their brain functioning decreases, but they continue to operate normally.”

Mikhael prepares for the description of the third and final stage. He has seen so many husks by this point, he’s become desensitized to the image of them. One stares at him as he flips the page, a picture clipped to his papers. He removes it carefully, fingers struggling to behave, and passes it to the people in front of him. They have identical reactions — horror, mouths agape, tears in their eyes at the sight. He waits until they have all seen it, all twenty of them, before continuing.

“The third stage, occurring one to two months after the second, is before you now. This is what my lab has taken to referring to as a husk. The specimen, having achieved whatever it is it wished to achieve, drains the host body of everything it has. The husks lack blood and fat, their brains shriveled and decayed with organs appearing long dead.”

Somewhere in the third row, an official raises her hand. She questions how long it takes for a person to become a husk.

“Anywhere from a week to a day, we’ve found. The host slowly loses their blood and drops in weight rapidly. As soon as the specimen leaves, however, the host shrivels as they lose everything they have within a short period. We’ve seen it happen as quickly as an hour or as long as a day. It’s unclear at what point they are considered dead.”

The researchers could never figure out when exactly the transition from host to husk would occur. It could happen anywhere, at any time. In the hallway on their way to lunch, in the middle of the night, during a con -

versation. Once the specimen was satisfied, the host was abandoned. Sucked dry and destroyed.

Questions pop up from all sides, respectful and orderly. Mikhael grips the podium before him tightly to keep his hands from going further out of control. His heart races as the questions begin. Mikhael focuses on the paper and waits for the anxiety to cloud his mind, twist his tongue, but it seems to be running late. He stares at the words written in his handwriting. But when? When had he written this note on the death of a subject, one which he could’ve sworn he never witnessed? When had he done this?

Mikhael blinks.

“—and thank you for your time and you…and your questions.”

Mikhael is aware of the room around him once again, as though waking from a deep and terrifying sleep. When had he started speaking? Better yet, when had he finished? He blinks again, trying to focus as people file out of their seats, questions and gratitude on their lips.

They are shaking his hand now, thanking him for all of his hard work. Asking things they couldn’t before. Mikhael, though, doesn’t hear a thing over his heart’s rapid — too rapid, unhealthily rapid — beating in his ears. He still stands near the podium, one hand gripping it ever tighter as though he could break through the wood itself and shatter it.

It had been three months since Mikhael began research. Two months since the first death he had observed.

Two months for symptoms to set in and progress to the second stage. Two months to reach the point of no return.

Someone is grabbing his hand now. From Mikhael’s position at the front of the room, he should’ve seen the person’s approach, but it’s as though the person teleported before him. He has lost time again. Mikhael’s hand is tossed up and down, relief clear in the gaze of someone who doesn’t realize.

None of them knows what is happening. None of them realizes what he has done.

As quickly as he can, Mikhael rushes out of the room. A private bathroom swallows him up, the door locked tightly. He shoves his sleeves to the elbows, physically unable to do it in an orderly fashion — when was the last time he had thought to look at his own body for symptoms? — and finds a series of fading, weeks-old bruises lining his wrists. His legs appear pockmarked with the same blue-green circles. Bruises along the veins.

With shaking, unwieldy hands, he reaches for the base of his skull. Pain rushes through him all at once, vomit coating his tongue. He leans over the sink to keep him from falling, porcelain digging into his ribs. Black dots burst in his vision, his entire nervous system screaming. Like pressing a hand to a hot stove — it’s a warning of danger, to never do such a thing again.

Mikhael struggles to catch his breath. When he finally can look up at the mirror, he sees a dead man.

My Mind is a Greenhouse...

Christopher JacobsonMy mind is a greenhouse, A vessel for growth you see, Plants twisting and turning and here… I am exactly who I wanna be.

I’m charismatic and extra smart, I say all the right things too!

I’m approachable and funny, With windows of my best view.

The sun shines through, The moon steals a peek, Here somebody loves me, And I do not weep.

My mind is a greenhouse, Sure a bit dehydrated sometimes, The imagination is kind of funny, Here the trees grow on limes.

Nothing makes sense, But everything will still grow, And here the pain gets planted, So surely happiness must show!

Six feet deep in soil, How cold it must be.

My stomach coils and… I wish you were here with me.

My mind is a greenhouse, But sometimes it’s kind of blue…

Some of the plants accidently died, I got distracted thinking about you.

But I don’t anymore, of course I did then.

Since the greenhouse kept giving. Until I said when.

When will I be, Free?

From my mind, Where I am confined.

My mind is a greenhouse, He’s trying his best, He lost his father, And never could rest.

Now there are locks on the door, At his and I’s request. A greenhouse is quite a chore, For a mind that can not rest.

Zach Baker

Zach Baker