Lyceum

A Literary Science Magazine

Co-presidents

Meheret Ourgessa

Zach Baker

Treasurers

Derek Dean

Maria Peacock

Editing & Contributing Advisors

Gabby Rachman (Text Head)

Derek Dean (Text Head)

Gillian Doty (Visual Head)

Meheret Ourgessa

Yufan Lu

Editing Team

Gabby Rachman

Gillian Doty

Derek Dean

Design Team

Zach Baker

Frank Szaraz

Elise Minion

Podcast Team

Yufan Lu

Madeleine Campbell

Front Cover by Sofia Elizarraras

Back Cover by Ayman Wadud

Media Assistant

Yufan Lu

Audrey Gibson

Zach Baker

Meheret Ourgessa

Aidan Cullen

Editor’s Note

Greetings from the Lyceum Team,

My first Lyceum meeting was in September of 2019. At the time, I barely had an idea of what science writing meant, what Lyceum represented, and why the magazine was established in the first place just a year before. It’s now been five years since our first publication. In my time at Lyceum, I have been able to see it expand in directions and publish works we never imagined at that first meeting. From our website and podcast that are now jam-packed with content to our dedicated team of interviewers who continue working to deliver the stories of the many professors who inhabit our campus, Lyceum is bigger than ever and spreading out into exciting areas.

I am proud that I have been able to help Lyceum grow during my time at Kenyon. But I truly believe that Lyceum has done a lot more for me. My experience writing, editing, and designing for the magazine has shown me the importance of science communication. And, through writing for Lyceum, I have discovered that science communication doesn’t not have to be a chore to the scientist. It can be a great pleasure and a passion, full of opportunities for artistic expression. And that’s just one part of what Lyceum does. Though we call ourselves Kenyon’s science literary magazine, Lyceum represents those in our Kenyon community who are drawn to every intersection of science and art, whether that be nature writing, science fiction stories, art & comics or even poetry.

Our tenth issue was organized around the theme of renaissance/rebirth, a signifier that while Lyceum has thrived at Kenyon for five years now, our team looks forward and envisions an even brighter future for our magazine. I am proud of the issues we have compiled this year and proud of the Lyceum members and leaders that will come after me. I only hope that those who came before me feel the same as I do about where Lyceum is now.

Without further ado, we are excited to present our tenth issue. We hope that you enjoy reading this work as much as we have enjoyed crafting it!

Best,

Editor’s Note............................................................................................................................4

Corvus moneduloides by Elianajoy Volin.................................................................................6

Crow by Gillian Doty................................................................................................................8

The Half-Dead Forest by Gabby Rachman................................................................................9

Photograph by Linnea Parker..................................................................................................11

College Cocoon by Grace Thompson.......................................................................................13

Photograph by Linnea Parker..................................................................................................15

Super fun Superfunds a.k.a. My Plastic Lungs by Katya Naphtali.......................................16

Dorm Gore by Dawsen Mercer................................................................................................19

Waking Up by Margaret Anne Doran.....................................................................................21

Assorted Nature Photographs............................................................................................22-23

Mushrooms and Depression by Meheret Ourgessa..................................................................24

Trophic Cascade by Eleutheria McCune.................................................................................28

How is the three-toed sloth adapted to its environment? by Linnea Parker...........................29

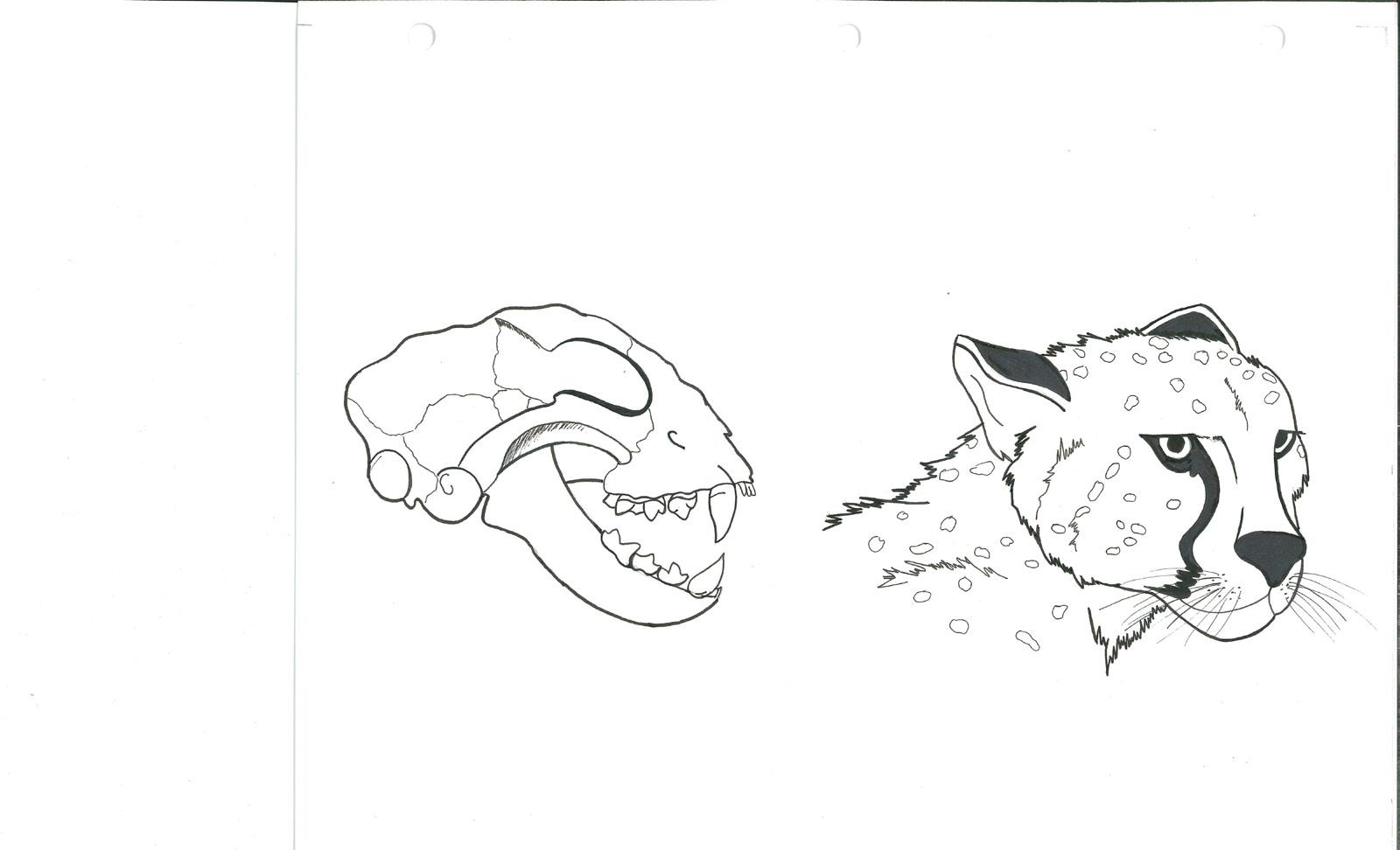

The Cheetah Coloring Book by Lara O’Callaghan and Grace Neugar..................................31

Curious Creatures by Lara O’Callaghan.................................................................................33

Grape Soda by Hannah Ehrlich...............................................................................................34

Unfinished by Delaney Marrs.................................................................................................38

Corvus moneduloides

Elianajoy VolinShe is always watching with bright open eyes. She eats popcorn peanuts berries. Boiled eggs and shrimp. Once she ate dog kibble crunchy

her parents scolded. She is mischievous she likes playing tricks. She waits for the light to turn red bracing against the whoosh of traffic rushing past she darts to the center once the cars have passed.

She wants to be big to lead but she doesn’t know how. Not yet. So she waits. She stays quiet. She learns the songs she ought to know.

They think she is ignorant, but she is not. She is not, she is not ignorant

It is important that you know this. Important that you know she is not a thief. She borrows, sometimes, quietly but only unneeded things. She likes pretty things. That is not a problem. It is not a problem to like pretty things She wants to look pretty. To look sleek and unruffled. She is unruffled you do not ruffle her

Bella StevensShe is learning. She is trying to reproduce what she has seen from memory, which is no easy task. It is no easy task She does not want to disappoint. She will be on her own soon in the big world scary. She has many tasks but she’d rather play, rather chatter.

Do you like to play?

Do you like to chatter?

She has friends, a few. She would like to have more She wonders what it would be, to be understood.

Your sister killed her sister, buried her wearing black A service was held, hundreds in attendance.

You call the gathering the murder

s he is purple and green and blue and black all at once she flies several miles to get home for the night home is high in a tree she eats snails and grubs and roadkill and whatever you feed her she is 300 days old she sings qua qua qua

Do you understand qua?

She needs to be protected. She needs you to protect her. She is too proud to ask you herself. Too proud and too hopeful, still young.

So I am asking you for her: Will you tell them?

She is not ignorant. She likes pretty things she does not want to disappoint. She wants to be understood.

Gillian Doty

Gillian Doty

The Half-Dead Forest

Gabby RachmanThis is the story of a girl whose life was forever changed. A girl who dwells in the half-dead forest, who has dwelled there for more than half of her life. When she was six years old, the girl and her older sister decided to travel past the boundaries of their backyard.

“Let’s go into the forest!” The sister exclaimed with mischievous curiosity.

“But Mommy and Daddy said we can’t go there,” the girl whined to her sister, her eyebrows slanted in concern.

“Well, Mommy and Daddy aren’t here.”

“But-”

The girl started thinking. She, too, was curious about this forest, she always had been, just like her sister. But she never could go. It was unsafe in the forest, Mommy and Daddy always said. But no matter how many times it was said, the forest still itched her brain, and now was her only chance to soothe it.

“Okay fine,” she groaned, “But only for a little bit!”

“Okay okay fine, let’s go,” her sister responded with rushed excitement. And off they went.

“Alright this time you count,” the sister instructed.

“But I wanna hide again!” the girl cried, disappointed with how quickly her sister found her.

“Look, I’m gonna show you how a real hide-andseeker does it. Just start counting.”

And so she did…

“Nine, ten! Ready or not, here I come!”

And she started looking.

And looking. And looking, and looking, but her sister was nowhere to be found. The girl, now terrified out of her mind and not knowing what to do, wanted to scream, but there was so much fear in her throat that she couldn’t. So instead, she stood still and looked around. But no matter how long she looked, she still saw nothing. Even when the sun began to set, and when the sky turned to dark blue and the other stars began to shine, the girl still could not find her sister. She saw nothing but these great trees, many of them broken in half, their roots still stuck in the dirt but their trunks decapitated. The girl stared at them with frightened eyes. The trees that were still standing did not care about the death of their friends. There was no time for mourning; their moss-covered roots and spiky dark-green leaves had to stay alive, nourish themselves with the air around them. They continued to stand, faced the sun, made their own leaves reflect the light, lived their lives as well as they found

it possible. The fright in the girl’s eyes eventually turned to admiration: The trunks are so tall and strong, she thought, the leaves are so bright and pretty and green! And so, now at ease, the girl looked forward, took a breath, stuck her back straight up like the trees’ trunks, and walked deeper into the half-dead forest. ***

Seven birthdays had passed, and the girl woke up one day to the pitch black sky. It was much too early for her liking, but she could not go back to sleep; the violent chirping, hissing, and thumping all around her were especially prominent, and she could not see what was going on or where all the noises were coming from. She lay on the ground, curled up, stiff, shivering, and cooing.

That was until the sun began to rise. The girl relaxed her tensed body, calmly silenced herself, and rose from her anti-slumber. She yawned, arms extended, and mouth gaped wide enough to swallow back any energy that was lost the previous night. She then attempted to scratch her head, but the mats in her hair blocked her fingers, so she gave up trying. She saw the dust and soil all over her arms and legs and attempted to rub it off, but only ended up spreading it further along herself.

I must find water, she thought, seeing herself so dirty. So she began walking and looking around. She saw that the berry bushes were still not in bloom: all that was there were endless shrubberies of wooden spikes. There were no daytime creatures around either, no chipmunks or little squirrels or even a single grasshopper hopping or running across the ground, just the ones at night who loved the cold so much, and loved to yell and hiss at the girl while she tried to rest. And the trees were now completely barren, no sign of life that the girl often saw in the warmer months, not even the pointy leaves she first saw when she arrived, the leaves she loved so much.

Squawk!

The girl heard the noise coming from the white sky, but it quickly disappeared. She had never heard anything like it in this forest before. She wished to seek it, but realized she did not have wings to help her fly fast enough. So she kept searching for water.

The girl walked for hours, and the more she walked, the more she thought about the water. Her dream water. A vast, clear lake, where she could submerge herself, where she could splash its magical liquid onto her face while the sun shone against her body. Where she could scoop handfuls upon handfuls into her mouth, relieved of the many days her system had gone without a single drop. She swallowed her phlegm and continued searching.

Aha! A small stream. Nothing close to her fantasies, but her eyes widened, and she grunted loudly as she sprinted towards the little bit of water she was able to find. There seemed to be no clouds in the water since she could see the dirt at the bottom of the stream, a good sign. She stepped in, the water only just above her ankles. Its coolness shocked her but she laughed and splashed it all over herself. She then fell into the stream with purpose and lay there limp, letting the current push her forward.

She didn’t get very far, but decided her journey was over. Ready to take a sip of the stream, her palms went in to scoop up some water, and she discovered that she had gotten used to its icy temperature; it felt pleasant on her skin. But she gazed down to examine her scoop only to discover multiple specks of dirt inside. She drank it still, tasting the specks on her tongue and feeling them move down her throat. At this, she began to feel nauseous. But now she realized she had also been floating in this murky water for hours. Her stomach turned even more. She sank down to the ground, looked up to the sky and cried quietly. The forest had deceived her.

It grew darker, but not too dark to see yet. The girl had been wandering, the dry dirt always on the bottom of her feet, the same dead trees constantly filling her vision, an undying buzzing surrounding her ears.

Pitter-patter!

She turned around suddenly, but there was nothing there. That was my next meal, she thought to herself, defeated. But she kept walking. Her head low, her movements slow and subconscious, but determination flickering in the back of her skull.

A noise from the leaves! A quick rustle.

She must find out the source of this noise. She turned around, grabbed a sharp stick, and crouched, standing on her toes, her irises opened wide and her ears paying extra attention.

But the chipmunk rushed across her feet from her side, out of her field of vision. Its claws pierced her flesh, leaving four small red dots on one foot and five on the other. She screamed silently from the pain, which distracted herself from the task at hand. Once the hurting subsided she went to chase the creature, but which direction did it go? She couldn’t figure it out. It was too late. The chipmunk had probably returned to its warm tree home, where it had left its food, where its family was waiting. I lost it, she thought disappointedly, as she felt a sharp pain in her stomach, like

knives stabbing her from the inside. Her body was crying for her nourishment, but she couldn’t give it anything. She didn’t know how. ***

The girl ended the day hungry again. And so she did not sleep that night either, her eyes wide open until the sun rose again.

As she lay, she noticed a bright blue bird sitting next to her torso like a tiny ball, its twig legs hidden by the brown feathers of its chubby belly. She giggled and said hello, but the bird did not laugh with her like the ones back home; it just tilted its miniscule head. The girl sighed. They did not speak the same language, but the bird looked as tired as she, its eyes half open with gunk in the inner-corners, mud and fleas in its wings and some feathers missing from its tail. She did feel for the blue bird for a short while, but eventually she just stood up and left it sitting.

She went back to the stream from the day before and sat with her legs crossed. She noticed the sun shining on it from a new angle, and piles of water bugs swimming in separate patches. It was easier to see the dirt in the shadowy parts, she saw, now frustrated at the sunshine for tricking her. So she watched the stream move with squinted eyes and a grimace.

The blue bird!

“How did you find me?” she asked, but it gave no answer, not even a chirp. It curled up into its little ball next to her knee and watched the stream with her.

“It’s dirty,” she said. The winged creature shook its head, and she let out a small chuckle.

“You’re funny,” she said to the bird. It didn’t respond, but the girl still felt listened to.

She noticed the blue bird staring at one of the water strider swarms, the one that looked particularly big compared to the others. The bird then stood up, and upon further examination, she discovered it was quite skinny despite the ball shape it made lying down. Other birds she had encountered before, in her backyard, were not quite as sullen. So she knew exactly what she had to do.

She noticed a decapitated tree a few steps away from the stream. She grabbed a big stick from the dusty ground, and approached the tree, whose bark stuck up higher than the top end of its stoop. Then, with what little strength she had, she dug the stick into the bark and ripped off a large piece. She went back to the shallow stream where the gathering pond skippers swam stagnantly, and used the bark to guide them towards the blue bird. Once the water bugs were close enough, the blue bird devoured them promptly, so quickly its beak made small clicking noises and its neck had worn out from moving back and forth. It looked at the girl with its black beady eyes, thankful for her care, appreciative of her kindness. She smiled back and said to it,

“You’re welcome.”

Linnea Parker

Linnea Parker

But then it flew away. It was gone for many hours, leaving the girl by the stream until the sun set. And then the sunset turned into complete darkness once again. She sat waiting for the bird so long that her glimmery and dreary eyes began to close while she was still sitting up straight. She felt like she was six again, waiting hopefully each night for her sister to return. Or that she would find her one day, or that they would find each other. But that never happened, and it never would. The girl forced herself to stop dwelling on it because she had no choice- her survival was more important. Too tired to feel sad, the girl laid down to sleep once again.

By the time she woke up, the sky was a dark blue, but not so dark that the trees couldn’t crowd her eyes. Half-asleep, the girl heard a faint squawk-tweet coming from the left of her head, but she did not have enough energy to pull herself up. So she turned around, only for her nostrils to get hit with the smell of day-old flesh. She sprang up, opened her eyes, and saw to her side a chipmunk’s carcass. And on the other side, the blue bird, its face pointed at hers. She was stunned that such a small, sweet creature could kill.

“How did you do this?” she asked it with concern. The bird shook its body, revealing black stripes on its tail and surrounding its face, neon blue and white spots on its wings, and slanted eyelids. The feathers on its head formed a spiky cone-shape and its beak grew longer and sharper. And then it grew, and grew, and grew until it became her size. And all of a sudden, the Jay screeched so loud that the sound shook and decapitated the trees around them.

The girl stood still and said nothing. Her eyes felt like they were bulging out of her sockets. How was she supposed to feel? Betrayed? Hurt? Sorrowful? She couldn’t figure it out. So much for a small, sweet creature, she thought, but didn’t say out loud because what if it heard her?

But the Jay knew what she was thinking anyway, it could tell by looking at her face. So it abruptly jerked its head to the side, which made the girl jump.

“Sorry,” she said timidly. But all of a sudden the timidness turned into rage.

“Wait, what even are you?” she said, “One day you’re this tiny, sweet little bird, and the next morning you’re a giant, scary, flying monster? Are you gonna eat me or something?” But the Jay tilted its head towards the chipmunk’s corpse next to them. So the girl did the same.

“Oh. That was for me?” she asked the Jay with guilt. It responded with squawking affirmation.

“You know, I’ve been trying to get food for awhile.” She said, “a chipmunk ran over my feet before I could catch it.” The girl showed The Jay her wounds, and it blinked with empathy. She felt it. But she was still weary when it beckoned her to follow it.

“And where exactly are you taking me?” she asked, but the Jay kept walking. Should I follow it? she asked herself. Her first instinct was to stay put, but she realized that if she did that, she would spend another sleepless night in the forest,

just like any other. So why not take the chance? She put her injured foot forward and they started their journey.

As the girl and the Jay traveled through the forest together, the girl was taken to places she had never seen before. The sky felt dimmer than usual. On some branches she noticed bundles of cobwebs, others were completely naked, not a leaf in sight. But she saw so many leafless trees standing up great and tall, more than any she had ever seen during the cold weather, the ground ahead of her was almost completely covered by their trunks! The girl kept walking with weary optimism.

And then the Jay stopped. So she stopped too. The tree they were standing next to had a large, gaping hole right above its root. The Jay gestured its feather towards the hole, letting the girl enter first. She stood still for some time with her eyes squinted, took a deep breath, and then tried to rush in, but not before she bumped her head against a branch hanging from the top of the hole. As she stepped back with slight pain in her head, she examined the branch and its intricacies. Protruding off that branch were several littler branches, and even littler branches off of those ones, growing in all different directions, some thick and some thin, some broken and weak, but some resiliently alive and together. Though the girl was at first startled at these branches upon branches, she eventually looked at them with awe in her eyes, just like when she first met the Jay. So she entered the tree with growing ease.

But upon walking in, it grew even darker. And as she walked further in, she saw countless skeletons of little creatures against the trunk walls. She grew nauseous again; she could not tell how old the bones were, but she still smelled the rotting flesh, like the chipmunk she smelled earlier that day, but ten of them, the scents of of their corpses slithering up her nostrils all at once. She asked herself with frightened regret, why did I do this?

And then she asked the Jay with that same frightened regret, “Why did you bring me here? I became friends with you, even though you scared me so much, and this is what I get?”

The Jay waited briefly before it squawked once more. And then it shrunk back to its tiny size, its cone-shaped head back to its completely round origins, its stripes gone and body plain blue, the belly feathers back to brown, the gunk in its eyes, the legs like twigs, the bald patches on its wings and tail, its tired disposition. It curled up into a little ball on the ground of its home, and the girl stood still for a while. She bent down to the Jay and said,

“I’m sorry I yelled. I know what it’s like out there. I am also tired and scared. But don’t you worry, we can get through this together.”

And before they got their restful sleep, the two of them sat quietly in each other’s company.

College Cocoon Grace Thompson

Why do I tear myself through my cocoon of equations with a sigh?

A. Is it because my hand aches from clutching my pencil in my white fist

B. Or is it because of my messy scrawled lines of nonsense

C. Or does the scene of a nearly empty classroom pull me from my tomb of worry

When I walk to the teacher’s desk I do not look into their eyes. For if I do my still-wet wings will crumple before their outstretched hand and I’ll collapse as a shell of despair.

True or False

Why did I wait until I was one of the only students left in the room to give up on my future?

A. My mind itched to write the most in-depth answers my sleep-deprived nerves could summon

B. The stubborn hope that I could suck the solution to the next question from the fluid of knowledge pooling in my abdomen

C. The vocabulary and symbols swirled around me in a vacuum of confusion so thick it turned into skin I had to eclose

D. The sound of the first genius striding up to give away their masterpiece and walking out into a future of security and well-earned relaxation inspired me to stay put

E. The sight of fellow devoted caterpillars chewing on words, devouring notes, and swallowing the bitter root of despair convinced me that this routine was normal

F. My egg was built up on a pedestal of academic validation so fragile a single letter is able to topple the nest of praise I’ve assembled my self-worth in

Construct a written response to your mountain of bullshit:

“Hello Professor [Insert name of brilliant adult whose lectures shine in front of their class like stars their gravitycursed students can never hope to catch],

I hope I am not imposing on this particular afternoon when the sun is shining so brightly and the weather is so balmy. I was perchance pondering if you have been able to review my [Insert the piece of stupidity so worthless author cringes while writing its name]. If so I was hoping my writhing unworthy larvae of a self could have a moment of your time to stare at the mesmerizing patterns of your wings. [Insert a moment of smiling and nodding at stars twinkling miles above your head.] Unfortunately, I couldn’t understand some of the keys of the universe you handed me and I think it reflected in my [insert sculpture of academia the artist slaved over for hours without sleep and food that shattered the moment starlight touched it]. Therefore, I would like to [insert jumbled screams and pleads intermixed with sobs] to you about my [insert the agonizing sensation of a blazing brand being burned into the fleshy worms of your memory].

Flightlessly yours.

[Insert name of future failure]

Translate the following sentences: Here is your grade for your last piece of work. I can tell you worked hard on it and I’d like to discuss it with you sometime during my office hours. Don’t hesitate to reach out if you need any help from me.

Here is the newest blemish on your academic record. I honestly hate to add it because you’re obviously so desperate for proof that you aren’t as stupid as you think. But truly when I looked over the piece of paper you handed to me yesterday I wanted to scream at your utter incompetence. It’s impressive you managed to fuck up some of the basics so thoroughly for a student who breaks themselves at the feet of pretentiousness. But I can tell by your bloodshot eyes, tapping fingers, and twitching wings that you are aching to fly and it sparked my sympathy. I want you to succeed. Every sluggish, wretched, miserable maggot that crawls in front of me I pity. How can you not pity creatures destined to be crushed under the boot of academia? It’s not their fault they’re idiots.

Extra Credit:

Once you fail this class, what’s next?

Maybe it’s the moment when you answer a question wrong

And you don’t hate yourself for it.

Maybe it’s the moment when you get a bad grade and smile

Because you know a single letter doesn’t determine your worth.

Maybe it’s the moment when you realize that grades just lead to GPA and GPA is only one spot on your resume and resumes only work if you have a job to apply to and you only know about jobs you can apply to because of people and places you know and to know people and places you have to be social and to have social skills you have to have relationships and to have relationships you have to meet people and to meet people you can’t actually spend your whole life holed up in your room breaking down over one damn math problem that you probably will never see again in your whole life.

Maybe it’s the moment when you tear open the chrysalis

That first brilliant moment of fresh air

When you can look up and see the blue sky and feel so damn free

Not because you’ve been hoisted up by meaningless letters or comments

But because you’ve escaped the trappings of doubt inside your own head

Linnea Parker

Linnea Parker

Super fun Superfunds a.k.a. My Plastic Lungs

An Autobiographical Narrative by Katya NaphtaliThe air burned again today. It was not like this every morning, but when the smell came it was strong and hot. My mother woke up choking on the perfume of brand new shower curtains. She had hoped that Cheerios would soothe my cries , despite the smell being too strong even for her to eat. Carrying me on her hip, she shut our windows tight to keep out the scent. She now had her growing stomach to worry about. Peering out our front door stood the culprit: towering orange brick and metal stacks spewing gray infection into the plump clouds above. Tacked across the orange, the rusted metal letters read NuHart & Co.

NuHart & Company Inc. owned a handful of factories in Greenpoint, an industrialized neighborhood full of immigrant families red lined into living among the waste. Since the 1950s, NuHart Factory has produced vinyl and plastic items like cheap shower curtains, squeaky couch upholsteries, and the vinyl sidings for houses. These products all required the plastic they used to be soft and flexible. Unfortunately, these plastics could only be brought to this softened state with the help of chemicals called phthalates. For the most part these chemicals stayed hidden behind the orange brick, but on rare occasions they snuck out past the scrubbers and lifted up

the pungent smell of plastics with a tinge of sewage. With the smell came plumes of white ash that spread across the neighborhood. The students at the Catholic school down the street used to rush outside and enjoy the summertime snow, competing to catch factory flakes on their tongues. Back then, nobody knew what snow in the summer could do to you.

My mother had heard rumors that the plastic they all smelled was cancer-causing. When I asked her about it years later she told me, “... we read or heard that overheating [plastic] pellets releases dioxins which cause cancer. So we got very concerned, especially as we were all sleeping at the front of the house.” With a quick Google search she probably found the same warnings I did. Warnings from the World Health Organization that dioxins impair, impair, and impair. Immune systems, hormonal balances, reproduction, and developing nervous systems. More importantly her eyes probably skipped to the bolded section sensitive groups, and grew blank when she read that these impairments applied mostly to growing fetuses and newborn babies.

From then on, every time the air burned, she called 311 for the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to come smell it themselves. “We would call every time the air was getting all stinked up. The problem was that the DEP would not show up until the next day or so and by then, the smell was gone, so we got nowhere.” She had only moved to Greenpoint three years before, but with another child growing below her burning lungs she demanded that the health inspector come see the effects from himself. He was thirty minutes from arrival when he called her, “... they asked if we could smell it inside the house, and I told him, not really, but because we never kept the windows open because of the smell and fears about it. He said they have a stronger case if it smells in the house…”

She wasted no time tearing through the house, slamming open windows, blasting fans, and sucking in as much plastic smog as she could. When the health inspector finally arrived, she opened the door, one hand holding my small sobbing body, the other moved intentionally to rest on her obvious baby bump. The inspector took one step inside, and his eyes grew wide in horror. “Close the windows! Now!” he cried out. Shortly after, NuHart went bankrupt from state-issued safety compliance tickets. These parts of the story I am only told in bits and pieces by my mother, and the neighbors who have lived here as long as we have, if not much longer. Surrounded by industrial blight, they would share stories of unsafe work conditions, family-wide illness, or being coated and choked by what the wind picked up.

My memories of NuHart are much rosier. The pattern of square fish bowl-like windows cracked open, housing songbirds that called to me each morning as I rushed to school. The uneven sidewalk permanently filled with leaves and wintertime snow that my sister and I would hop around in until former Mayor Bloomberg decided our block was worth shov-

eling. The wall of the abandoned Nuhart factory that collected nightly graffiti from artists I never witnessed, covered up every few days with off-orange paint. This was the wall I walked along when coming home late at night because it had more overhead lights than my own side of the street. My mom always insisted that I check behind myself as I walked, despite the biting wind tunnel it created as you turned onto my block. The desertedness of the orange brick wall was a sign that I was almost reaching home.

All of these memories did not include fearing the wall itself. Little did we know that the toxic chemicals NuHart used still lay in wait beneath our feet. In 2010, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation declared my orange brick wall a Superfund site, a location containing so much hazardous waste that the state had to step in to clean it up. This designation led to a secret artist coining my favorite graffiti on the wall, Super Fun Superfund. Instead of pluming dioxins into our air, twelve abandoned storage vats dripped beneath NuHart. The content of these vats curled downwards into our soil and groundwater, but this time it was those phthalates once used to soften plastic shower curtains. Twenty feet down below, 5.5 feet of phthalates floated on the surface of our groundwater, a resting thick viscous sludge.

These phthalates are most common in their fluid form, able to leach into and out of materials with ease. They can enter our bodies from almost anywhere: seeping out of plastic packaging onto the food we eat, into our blood from hospital blood bags, and from plastic toys in the mouths of our children. Every day, the environment we have created rubs off on us. If we consume below 81.5 micrograms (or 80 millionths of a gram) of phthalates per pound of body weight we can digest them without repercussions. While most plastics containing phthalates have been recalled, we can still track the footprints of plastics in most of our bodies. This ubiquity of phthalates unfortunately makes it difficult to determine the impact they have on our health. The major type of phthalate found under NuHart is DEHP (or the scary chemical name Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate). DEHP has longer molecular legs than other types of phthalates. As a result, they take more time to degrade environmentally and to be metabolized inside of our bodies.

I wondered how my body would process these phthalates if the fistfuls of dirt I would taste before I knew any better contained chemicals as well. In one bite, my body would carry dirt and chemicals down into my stomach. Resting here amongst enzymes and bacteria, I would simply digest these phthalates. My digestive enzymes would begin by chopping off one of DEHP’s long molecular legs before breaking the rest of the molecule down into smaller and smaller parts. In its simplest form, I would be left only with carbon dioxide and water. While these levels may not immediately pose health risks, most studies have only tested phthalate exposure at higher levels in the short term, not looking at chronic ex -

posure experienced in neighborhoods like mine. There was a reason the neighbors had whispered: exposure to these phthalates not only could cause cancer, but they messed with our hormones as well. Beneath my feet as I played in snow drifts, the hormone blocking sludge rested. DEHP has the ability to block testosterone and other androgen hormones from binding within our bodies. In rats exposed to high concentrations of phthalates, sperm movement decreased in male rats, and female rats did not ovulate. Additionally, the metabolized version of DEHP functioned as a testicular toxin. Exposure impacts the fertility of adults, but with less of a lasting impact than it has on children. When male rat fetuses were exposed to phthalates, their testicles did not descend. They were missing a fundamental hormone for their development: testosterone. These harmful effects followed the rats as juveniles, even after no longer being exposed to the phthalates themselves. There is still so much we do not know about phthalates. Particularly, we do not know what happens when you are exposed to phthalates chronically. Research published this very year found DEHP reduced immunity in worms and sped up aging. Could they do the same to us?

State officials said these chemicals were safer under the ground. The real concern would come when the site gets developed some day, and these chemicals would be dug back up and possibly released back above ground. Almost ten years later, we are once again coated with dust. Before, it came

from the chimneys of NuHart. But now it blows over as the factory crumbles to the ground. When the factory sat still, filled with the chirping of birds, my nerves sat still too. No dust, no vapor, just a slow sludge itching beneath our feet. Why would we not keep these unknowns buried under soil and concrete out of mind and out of view?

I left home for nine months and returned to my block decimated by a construction site. Steel trucks raging, the walls of our old house ratting each morning until they cracked, and dust coating our window sills like it had when the factory was once active. “It’s like the Wild West,” my neighbor remarked on a community Zoom about the development. “Done in two weeks,” the developers promised, but we had heard this all before and they shifted in their seats when we asked for a guarantee they’d finish the project for us. All they could show were airlocked tents and power washed trucks. They knew as little as we did.

They risk the lives of us who live across the street to attract hundreds more. Accommodating new neighbors to peer down on my now cracking home, unaware of the unsolvable trauma buried beneath the layers of concrete poured beneath them. They don’t tell you this when you sign your lease. In the fine print, this comes with the territory. Maybe if they had not moved here, the plumes would have been left frozen beneath us and they would have never had to feel the dust that once coated my infant fingers.

Dorm Gore

Dawsen MercerIt’s so sad , she says hand on your knee

Seeing you do this to yourself

You don’t tell her

It’s a chrysalis

You don’t tell her you’re gonna be better soon

You don’t tell her you will just be smaller then you’ll be back

Sure,

But how do you wake up when you’ve been dead for so long? It has to be an undoing

There’s gotta be some blood drawn in the resurgence

You have to mutilate the caterpillar soma

And tear out of yourself

Rip the seams of your skin, pierce your fingers through it, slash it like latex

Fight for that first breath

Come back

Come back

Come back to life

It’s a nullified existence, let me tell you

Hollowing yourself out carves the brain away too you know

At least keep that in mind

You have to un-consume yourself

My god, you’re starving

Your body has been eating itself

Getting gory on a dorm mattress

Be proud , You’re the unstoppable force

Immovable wall

Damn near time you came unstuck from the belly of the boulder

You have to look at yourself for what you are

Pull back the skin from your temple to your toes and step outside of yourself

and come back

Waking Up Margaret

Anne DoranA boy and a girl decided they wanted to live together on top of a hill. Follow the gravel up, noticing the wet-weather pond, the weeping willow, and the jonquils first planted four generations ago, you will pass a whistle stop. The proud brick house.

Cows are crying in the distance, so are the ghosts of catalpa trees who once lined the fencerow. Spring peepers creak and crow, crickets hum a melody. It glistens. Broccoli and peas hum as they grow heavenward, the cleome chirps, nodding up, down. truffula trees, i always imagined them as Grass whistles, sh sh sh sh sh, soft and slow, the smell of manure weaves in and out, subtle and sweet. English Cockers snore.

Coyotes scream now and again.

A barn, home to decaying comic books, sweet-smelling tobacco sticks, a terrifyingly high number of inbred barn cats. A dent in a fencepost where a girl once collided with the unforgiving wood. Land dotted with manure and secret spots made for children with broken hearts. Bleached by sun, frozen alongside the bulls, submerged in the wettest of Aprils. 1,000 acres of heartland.

Avenues to violence and heroism, cunning and hurt feelings, the host to a three-person Olympics, the site to countless triple-dog-dares.

The sun falls over itself trying to reach every inch of sky. No leaf is left dark, no brick unfaded.

The creeks gurgle, their poorly-oxidized water falling over fossils and wish-leaves. God whispers to the girl reading on the rock, a soft secret she’ll never tell. her hair falls in a tangle: disregarded chestnut strands that cry for a comb

A heron soars on through, steals a woman of her breath, leaves the cows unfazed. Trees die, fall over, become dragons. Calves learn what life is. So do children. Weeds grow, horseflies bite, skunk barns sink.

The land is soft and forgiving, warm to the touch.

The doves don’t coo this morning, but there is another rhythm made by the droplets, an almost birdsong, under the hackberry trees.

The rain slows to a peter, then a trickle, then nothing. It never ends, precisely, it’s just no longer there.

The bulbs planted last fall begin to erupt through the soil that breathes around them. The farm changes, soft and slow, remembering what it’s like to once again live in the sun.

Mushrooms and Depression

Meheret Ourgessa

When Mara McGraw found out she had neuroendocrine cancer in 2017, she was given a terminal diagnosis with only 18 to 24 months to live. She was able to live longer than expected through the treatments she was receiving. But by late 2020, her chemotherapy had failed. She quickly felt hopeless and depressed about her condition. Mara did more than a year of talk therapy and tried antidepressants such as Prozac to combat the depression and anxiety surrounding the end of her life, but nothing helped. Then she heard about psilocybin therapy.

After lots of mental and even some physical preparation, Mara took three doses of psilocybin in an outdoors environment, in the presence of a facilitator who led the “therapy” session and administered the drug. During the session, Mara was mostly left to contemplate on her issues internally with little dialogue between her and the facilitator. Soon after the session ended, she started feeling uplifted and had a completely different outlook on her future. While being interviewed by a local news station, Mara said that, “the one psilocybin therapy session gave me more lasting effects than a whole year of talk therapy.” She said she smiled as she thought of the end of her life.

Mara was one subject of many in revolutionary clinical trials testing whether psilocybin therapy can be helpful for treating depression. Recent studies have highlighted more and more that psilocybin therapy can be very effective for the debilitating condition. But as more of these studies continue to come out, it is important to remember that we aren’t just

now discovering that psychedelics have therapeutic benefits. We’ve been here before, back when psilocybin was just starting to pop up in the cultural landscape of the United States. *****

Curiously enough, the story of psilocybin in American pop culture starts with a vice president of J.P. Morgan, a Robert G. Wasson. In 1957, Wasson published an article in LIFE magazine describing his experience with “divine mushrooms.” He had traveled to Oaxaca, Mexico where he participated in a religious ritual of natives in the region during which he consumed the mushrooms. He described the mushrooms as “divine” and able to make those who eat them “see visions.” Wasson wrote about these mushrooms in a very reverent way, describing his experience as astonishing and saying that it left him “awestruck.” At the time, nobody knew exactly what in these mushrooms was causing humans to experience hallucinations. It wasn’t until a year later that a chemist by the name of Albert Hoffman and his research team isolated the main psychoactive component of the mushrooms and named it psilocybin after the genus name for the mushrooms.

Scientists soon became intrigued by the therapeutic potential of the drug. By the early 1960s, Harvard researchers Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert had kickstarted the Harvard Psilocybin project, looking into the therapeutic and rehabilitative effects of the drug. Leary and Alpert administered the drug to undergraduates at Harvard who vol-

unteered as research subjects. They reported that 60 percent of their subjects from one study exhibited “a marked broadening of awareness” and 95 percent had said the drug session had “changed their lives for the better.” The team also gave psilocybin to informed prisoners in hopes of rehabilitating them and reported that these prisoners were less likely to commit new crimes after being paroled. Around the same time, other researchers were also finding that lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) can have similar therapeutic benefits, employing it successfully to treat alcohol addiction.

But when the 1960s counterculture movement was starting to take shape in the United States, psychedelics were quickly associated with it. Numerous key figures of the movement, such as John Lennon, Mick Jagger, and Bob Dylan, soon followed in the footsteps of Robert Wasson and traveled many miles to participate in the psilocybin ritual at Oaxaca. They set the stage for many more in the movement to follow suit. Soon enough, psychedelics became such a core part of the antiestablishment subculture in the 1960s that taking LSD was considered a rite of passage in the community.

Alpert and Leary would become icons in the movement themselves. The pair first started to get into trouble with the Harvard administration. There were concerns about how objective the researchers were in evaluating their data as both Alpert and Leary had also often taken psilocybin among other psychedelics even when they were carrying out their experiments. Further tensions arose as many undergraduates at Harvard started taking psychedelics outside of research endeavors. Concerns for the health of these undergraduates and around the reputation of Harvard as an institution grew. Alpert and Leary eventually lost their jobs by 1963 (Alpert for neglecting his teaching duties and Leary for allegedly distributing psilocybin to undergraduates) and their project was shut down. But the pair soon transformed into countercultual icons as they defiantly continued using, distributing, and learning more about psychedelics outside of Harvard.

Not long after, publicization of Alpert and Leary’s questionable project and the association of psychedelics with the counterculture would become driving forces for the illegalization of psychedelics in the United States. The former raised the public’s concerns about the use of these drugs and the latter would become a political motivation for the Nixon administration to ban psychedelics altogether. By the early 1970s, the United States government caught on to an opportunity to persecute one of its biggest enemies: the antiwar & antigovernment left (who were mostly the youth of the counterculture movement). By having the public associate drugs such as marijuana and psychedelics with this group of the population and criminalizing these drugs heavily, Nixon’s government sought to disrupt and control the counterculture movement.

And so the United States enacted the Controlled Sub-

stances Act of 1971 ushering in the disastrous War on Drugs. Psilocybin and psilocybin-containing mushrooms were classified as Schedule I substances by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Schedule I is the most controlled and restrictive classification for drugs in the US and includes other substances such as heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine. The world quickly followed suit. The United Nations drafted an international treaty to prevent the production, consumption, and distribution of psychedelics including psilocybin, a treaty that would eventually be signed by more than 180 countries. Anti-drug campaigns, some, no doubt, bearing the political motivations and prejudices of the Nixon administration, quickly painted psychedelics as much more dangerous than they actually were. Very inaccurate claims were made such as LSD causing fetal malformations. Research into psilocybin and its potential therapeutic benefits ground to a complete halt as a result.

Research on psilocybin only restarted about four decades later. In the late 1990s, researchers in Germany and Switzerland carried out studies to better characterize the short-term psychological and physical effects of psilocybin. Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, the number of papers published on psychedelics gradually increased and eventually researchers started investigating the use of psilocybin to alleviate the anxiety and depression that comes with terminal medical diagnoses. Recent psilocybin research has built on findings from the 1960s and has indicated that the drug has great potential for treating depression.

Psilocybin therapy for depression is quite different from just taking antidepressants. It involves a lot of talk therapy both prior to and during the administration of the drug. The aim is to guide patients into developing helpful insights about their emotional and behavioral patterns. The patients are then encouraged to apply these insights to their life moving forward. Studies about this therapy point out that the psychological preparation and support during the drug administration session are very important for its effectiveness. This is reminiscent of many psychedelic rituals found in different cultures throughout history. From the ayahuasca ceremonies that have been carried out for thousands of years in parts of South America to the religious ritual that Robert Wasson experienced in Oaxaca, some form of healing verbal communication between those using the psychedelic and the ones conducting the ritual is a core part of these practices. In the same vein, talk therapy seems to be inextricably linked to psilocybin treatment — all the studies that show the potential of the drug to treat depression involve some form of talk therapy along with the administration of the drug.

Research around this novel treatment for depression has blown up in the last few years. Psilocybin therapy is promising for a number of reasons. Psilocybin has minimal side effects compared to most other antidepressants. Popular

antidepressants such as fluoxetine (Prozac) and sertraline (Zoloft) can have a range of debilitating side effects such as indigestion, nausea, reduced sex drive, and weight loss or gain. Some of these side effects can even be irreversible. Furthermore, many antidepressants currently on the market may not start taking effect until at least four to six weeks after the patient starts the medication. Psilocybin therapy, on the other hand, is reported to rapidly reduce depressive symptoms. Psilocybin therapy also seems to be quite effective for a lot of people suffering with depression who often find that their symptoms do not subside despite trying a variety of treatment options (a condition called treatment-resistant depression).

Despite what 1970s anti-drug campaigns would have you believe, psilocybin is now considered a relatively safe and nonaddictive drug. In the human body, drug addiction is mainly linked to dopamine, a neurotransmitter or an important chemical messenger that transmits signals in the nervous system. Dopamine release in the body is associated with reinforcing pleasurable or rewarding activities in our brain. Addictive drugs such as cocaine and heroin work by greatly elevating levels of dopamine in our brain. This, in turn, causes very strong associations between feelings of pleasure and taking these drugs. Psilocybin, in contrast, is associated with serotonin (another very important neurotransmitter) and the serotonergic system and is generally not considered addictive. Psilocybin’s effects also decrease significantly upon consecutive doses in a short timespan making it much more difficult to abuse. And while psilocybin can cause nausea, increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, and other short-term effects for several hours after its administration, it seems to have minimal long-term detrimental effects on users’ health.

We still don’t fully understand how psilocybin works

biologically to alleviate depression. Some researchers have claimed that psilocybin decreases the activity of specific parts of the brain, namely the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex. These parts of the brain seem to be more active in depressed patients. The amygdala specifically is very important in how we perceive the world around us and how we react to these perceptions emotionally. In depressed patients, the amygdala was found to be hyperactive when processing negative stimuli, which might explain why decreasing the activity of this part of the brain alleviates depression. Other research has also pointed to the interaction of psilocybin with serotonin receptors as a potential mechanism.

While there is no conclusive evidence as to exactly which or what combinations of these explanations are the reason for psilocybin’s effectiveness in treating depression, this should not mean that it can’t be utilized as a treatment option. Really, we don’t even know how antidepressants currently on the market work either. Historically, depression was linked to low levels of serotonin and common antidepressants such as Prozac were thought to work by reversing these low levels. But we now know that there is no strong evidence to support the conclusion that depression is caused by low serotonin levels. Yet antidepressants are still considered safe and effective. Right now, we are in a similar situation with psilocybin therapy — we are not sure how it works, but it can be safe and effective. *****

Today, the medical significance of psilocybin is slowly being recognized globally. At the start of 2023, more than five decades after the UN drafted the treaty to ban psychedelics worldwide, Australia became the first country to recognize psilocybin as a medicinal option for the treatment of depression. Though some regulatory roadblocks remain in the country preventing psilocybin therapy from being direct-

ly prescribed and administered by psychiatrists, this marks a huge step forward. In Canada, while psilocybin has not been approved as medicine, programs such as clinical trials and special exemptions allow a select few to undergo psilocybin therapy. Quebec has even approved health coverage for the treatment to those who qualify.

Back in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted “breakthrough therapy” status for psilocybin treatment, which has accelerated research and development. Mara McGraw, the cancer patient who underwent psilocybin therapy ended her interview by urging voters to pass a measure that would permit psilocybin therapy in Oregon. The measure passed in November 2020. And in January 2023, Oregon became the first state to fully legalize the drug for medicinal and personal use, shortly followed by Colorado. The governments of both states are quickly moving to implement the legalization measure. Many more cities and states in the US are now also either moving towards or

have already decriminalized psilocybin. On the federal level, the United States’ DEA still designates psilocybin as a Schedule I drug, a classification that claims psilocybin has “a high potential for abuse” and “no recognized medical uses.” Scientists are recommending the reassessment of this classification as it will continue to be a huge hurdle for psilocybin therapy in the US.

As the coming years will likely be a decisive time for psilocybin therapy, now is a more important time than ever to make informed decisions on the ways in which we view it. Approximately one in twenty adults in the United States suffer from depression and of them, as many as 30% are thought to have treatment-resistant depression. Psilocybin therapy can be an invaluable life-changer for these millions of people and perhaps millions more to come. And we would be doing all of the world a great disservice by denying all these people a way to heal just because of scientifically unfounded fear and prejudices.

*Complete piece with all references can be found on kenyonlyceum.wordpress.com

How is the three-toed sloth adapted to its environment?

Linnea ParkerEvolution and Background

The path to the modern sloth is not clear. Sloths have undergone dramatic changes over millions of years of evolution. Ancestral sloths occupied many different niches and habitats, including the ocean, underground, caves, cliffs, mountains, and trees. They were able to live in all of these habitats because their iconic claws and low metabolic rates allowed them to climb, swim, and dig! A complex digestive system is ancestral to sloths. In fact, they are suspected to have thrived in so many places without much competition because they could eat plants that were too hard for other species to digest. Giant ground sloths may have swallowed avocados whole! Researchers have found evidence of 80-90 different genera of sloths coexisting in different niches. Sloths are a part of the family Xenarthra, which also includes anteaters and armadillos. This family has adaptations suited for living underground: Their large claws aided them in digging, while their stiff lower back gives further movement to their forelimbs. All but two species of sloths became extinct due to climate changes that their ectothermic bodies could not handle. Modern three-toed and two-toed sloths are not as closely related as one would expect. Three-toed sloths likely branched off millions of years before the two-toed sloth. Researchers therefore hypothesize that their inverted suspensory locomotion (upside-down movement) evolved twice independently!

Sloth Skeleton

The sloth skeleton is extremely important to their lifestyle but it is not well understood. Sloths are one of only two mammals to have “extra” cervical vertebrae, an exception to the generally accepted rule of seven cervical vertebrae for mammals. Threetoed sloths can have 8-10 cervical vertebrae, which means sloths have extra points of attachment in their necks! Researchers are unsure what these extra vertebrae mean for sloths. The hypothesis is that these extra vertebrae allow for increased rotational movement of the neck. In fact, sloths can turn their heads 270° around! This has been postulated to help sloths move through the trees while suspended upside down, allowing them to see their forelimbs

for branch placement. It may also help sloths keep an eye out for predators, though they are almost completely blind. Three-toed sloths’ pectoral girdle (where the arms attach to the inner body) is mobile, but their pelvic girdle (where the legs attach to the inner body) is immobile. The increased movement of the pectoral girdle is thought to help in forelimb placement and suspension for climbing trees. Sloths’ tendons in their hands are adapted to lock into place to help them hold onto trees. Their specialized dermal derivatives- claws and teeth- grow continuously, which gives them the ability to grasp and eat harder surfaces.

Sloth Muscles

A very important part of a sloth’s anatomy is their muscles that allow them to grip tree branches and suspend upside down. Sloth muscles are not well understood and continue to surprise researchers. For example, it was thought that sloths would have a large number of slow twitch muscles for stamina to hold themselves in trees. However, none of the muscles in the forelimbs are adapted for large amounts of strength. Sloths have a lot of fast twitch muscles that are dedicated to rotational movement. These fast twitch muscles help sloths maneuver and position themselves in the tree canopy. As a result, scientists are not sure how sloths can suspend themselves for such long periods. The best possible hypothesis is that sloth muscles become more pennate (symmetrical) the further they are in the body. This increased cross-sectional area gives sloths stamina and strength. Overall, sloths have an extremely reduced muscle mass for a mammal of their size: about 23.6% of their body mass compared to an average arboreal muscle mass of 33%! A substantial amount, 5%, of a sloth’s muscle mass is dedicated to their forelimbs. This is likely because sloths rely heavily on their forelimbs to move through trees.

Sloth Fur Ecosystem

A sloth’s fur is an ecosystem, and is home to a variety of organisms like bacteria, fungi, algae, and even moths! The moth Cryptoses choloepi exclusively lives and depends on sloth fur. In this

mutualistic relationship, the three-toed sloth makes the extremely dangerous journey from the treetops to the ground once a week to poop. When the sloth poops, the female moths lay their eggs in the poop. Then, new moths hatch and fly up to the tree canopy to live and mate in the sloth fur. Sloths with more moths living in their fur also have more nutrient-rich algae which they often snack on from their backs. It has been hypothesized that sloths rely on these moths to cultivate algae growth, which could provide an important supplement to the sloth’s poor leaf diet. This adaptational relationship benefits both the moth and the sloth. In particular, the sloth gains much-needed nitrogen and lipids from the algae that it cannot get from its strict leaf diet. In addition, the algae growth provides camouflage in the trees from predators, especially those that rely on eyesight.

Sloth Metabolism and Stomach

Sloths have a stomach consisting of four separate chambers. They have a strict leaf diet that consists of a variety of tropical trees. They have to be constantly eating and digesting leaves to survive. These leaves are very poor in nutrients, hard for

many species to digest, and can be toxic. To adapt to this, sloths are foregut fermenters, which means they continuously rechew and digest their food from the rumen (just like a cow chewing their cud). This allows them to fully break down their leaves and absorb as much nutrients as possible from them. It can take a sloth up to a month to digest a single leaf completely. As a result, they can famously starve to death on a full stomach. At any given time, about ⅓ of a sloth’s body weight is the leaves being digested in its stomach. Sloths have been found to have fibers that hold some of their internal organs to the body wall to keep this huge stomach mass from crushing their lungs when they are upside down. To compensate for all the energy they need for digestion, sloths have extremely low metabolic rates. Sloth metabolic rates are 40-60% of what is expected of their mass when compared to other mammals like cats and small primates. This is due to their extremely reduced skeletal muscle mass which, in turn, causes them to also have low and variable body temperatures that can fluctuate based on their envi ronment. Having such a low metabolic rate is a trade-off that allows sloths to put more energy into digesting their food.

Cheetahs have lots of special traits in their legs and paws to help them go as fast as possible. They have super long bones to give them a longer stride, which helps them move more quickly. Most of their leg muscles are close to the body, a phenomenon called proximal bunching, so that their legs are lighter and easier to swing. Their bones are very strong so they don’t break upon the impact of landing. On their paws, they have pads with grooves in them. These grooves give the cheetahs a better grip on the ground, so they don’t slip when running.

Cheetahs also have semi-retractable claws, which makes them unique from other cats. This is why cheetahs are so bad at climbing trees!

Cheetahs can run as fast as 29 meters per second, almost 65 miles per hour! This is faster than any other land animal. At their top speed, cheetahs gallop, but in a different way from other animals. All four of their legs are in the air at two different times each cycle, which means they have two suspension phases. In the first suspension phase, called the gathered phase, both the forelimbs and the hindlimbs are under the body, and the spine is flexed. The other suspension phase, called the extended phase, occurs just after the hindlimbs launch off the ground. In this phase, the spine is extended. The combination of these two spine movements increases the cheetah’s stride length and speed. The long tail acts as a rudder and helps the cheetah change direction in high-speed chases.

Cheetahs have small, well-adapted heads. It is streamlined so they can minimize drag and run easier. Their eyes are set high in their heads, perfect for giving them a wide-angle view of their surroundings. Cheetahs have great vision. They don’t hunt using smell or hearing like some other predators; they rely mostly on their great sense of sight. Cheetahs have black marks on their face that look like tears to help minimize the effect of the sun while hunting during the day. They also have a special version of photoreceptor cells in their eyes called S-cones, allowing them to see different colors especially well.

Cheetahs don’t want their food to be stolen by lions or other predators, so they eat very fast. Their teeth are highly specialized. Their canine teeth are for gripping prey to suffocate it, while their carnassial teeth are perfect for skinning carcasses. Cheetah tongues are covered in little spikes called papillae, which both help to groom their own fur and to strip meat off bones.

Cheetahs have a tan coat covered in black spots. In the environments that cheetahs live in, this pattern is a highly effective camouflaging device that helps them sneak up on prey. Days can get really hot where cheetahs live, so their coats can’t be too heavy. They have a light coat so they don’t overheat when sprinting.

Cheetahs live in grassland savannas. Usually, their habitat has tall grass, some bushes, and some trees. Cheetahs share their habitat with gazelles, warthogs, birds, lions, hyenas, and many more animals. Some of these animals are food, and some are competitors.

Grape Soda

Hannah Ehrlich

“Andrew! Andrew! Holy Mother of Mars, Andrew, why don’t you ever listen?” Professor Ooben hollered. She waved her six arms up and down while slime sputtered out from between her gummy lips. After studying human behavior for over fifty years, she could not believe she had to waste her expertise on hopeless students like Andrew.

Andrew’s eyes were still fixed on the window of the spaceship, watching the stars zoom past and the comets pummel towards nothing. He heard everything Professor Ooben was saying perfectly, though he did not put in the mental effort to process it. In fact, Andrew’s species, known as the OneEyed Gogs, has some of the best hearing capabilities in the galaxy, with a range of up to two human miles. Not only did he have the impeccable hearing of his species, but he inherited a power to control human minds that only two percent of his kind has. This makes him one of the most desirable aliens to become a spy for Home Planet’s mission on Earth. Despite his physical advantages, Andrew happened to be one of the worst, most disobedient pupils that Professor Ooben had ever had to teach. No matter how strong a rotten pupil’s hearing may be, nothing could get him to pay attention to his professor. Nothing except ...

“Andrew, we are landing on Earth in approximately fifteen human minutes. We are running low on time, and if you do not start paying attention, I will have to fail you again.”

“C’mon, Ooben! If I fail another one of these stupid evaluations, my parents are gonna send me to the moon mines!” Andrew whined.

The Moon Mines were just about the worst place Andrew could imagine himself being, worse than Earth, even. When a young alien is sent to the moon mines, they never come back. Their years are spent mining for gems that are used for energy on Home Planet, and other than that, there is not much else to do on the moon unless you enjoy taking naps in dusty craters. But if Andrew did not use his exceptional abilities to assist the most pressing mission Home Planet has, his parents would have no choice but to send him away to Phobos, one of Mars’s moons, so they could save themselves from the embarrassment of having a son that is nothing but a failure.

“Well, then. If you’d rather be a proper spy that saves Earth from its doom instead of being a dirty miner, I suggest you look alive, because your evaluation starts now,” Professor Ooben said, eyes on the clipboard.

Andrew scoffed and rolled his eye. “Okay. I’m ready.”

“Wonderful. Question 1: What is your name?” Professor Ooben said as she clicked her pen.

“Easy, it’s Wexx. Next question.”

Professor Ooben shook her head and her pink face got pinker with frustration. She ticked an aggressive “X” on her clipboard.

“That’s my name! How is that wrong?”

“Your human name is what I’m looking for. We’ve been through this! At home, you’re Wexx. On Earth and in my class, you’re Andrew.”

“That is such junk! Those billionaire idiots on Earth give their kids names with freakin’ numbers nowadays. Wexx is a fine name.”

“I suggest you don’t argue with me during this process. It would only make this worse for you. You should know that when we come to a human planet, we need to assimilate as much as possible. Humans are intimidated when people stand out, and Andrew is a non-threatening name for the nice young man you will pose to be.”

“Humans are idiots. They’re the ones turning their planet into a flaming ball of garbage and we gotta fix it as if it’s our problem.”

“It is our problem, because when that planet becomes too hot for their weak bodies to handle, they will come and settle here. We all know they would rather develop the technology to flee their planet before they would fix the climate problem they started. So, if you could one day become a spy, you could build up your ranks in the human political world and use your mind-control powers to sway populations into, as they say: ‘going green.’ Then, the humans will stay away from our perfect society and continue to live on their own.”

“I’ve heard this lecture a million times! I know that I am one of the only people who can save our planet from the infiltration of a useless species, I really do. But I still think it’s wrong that a species totally unknown to the humans has to fix their problems.”

“You may have your powers, but if you’re unwilling to use them, the moon mines are waiting for you drew.”

“Fine. Just keep going,” Andrew said and crossed his sticky green arms.

“Very well. Question 2: Why do you only have one eye?”

“I know this. I know this…” Andrew hesitated for a few seconds, realizing he did not know it at all. “It’s because my dog ate it?” he said with a grin of fake confidence.

“Excuse me?” Professor Ooben said as she ticked another “X” on her clipboard.

“What? How is that wrong? Dogs eat stuff all the time on Earth!”

“Dogs eat homework, Andrew. They do not eat eyes out of their human’s sockets. If a human asks about your form you will simply say, ‘I was in a terrible accident. I’d rather not

talk about it.’ Their discomfort levels will become so high that they will not ask any more questions.”

“Could it be an accident involving a dog?”

Professor Ooben tensed up for a few moments, her eyes starting to glow red. Once she found a shred of peace within herself, she moved on. “Your next exercise will be to choose your clothing for the Occasion. Today, your Occasion is to purchase a beverage at an old-timey American soda shop in a popular tourist town. You will be a tourist trying to cool off from the summer heat.”

Each of Professor Ooben’s pupils must have a simple interaction with humans, which she calls an Occasion, to pass her introductory class, Earth Assimilation 101. This can be anything from buying a clothing item to asking for directions, and it can take place anywhere in the world since most aliens know all human languages by age five. Professor Ooben decided to save one of the more insufferable places for her least favorite pupil, and she was pleased with his reaction.

“Ew! Tourists are the worst kind of humans! Can we go anywhere else?” Andrew pleaded.

“No,” Professor Ooben said as she scribbled critiques with a sly smirk on her face.

Andrew shuffled over to the wardrobe, disappointed. “Well, if I have to be a stupid tourist, then I am going to wear stupid clothes.” Andrew sifted through a closet full of suits, swimwear, winter attire, and other miscellaneous clothes until he picked out a pair of tan cargo shorts, a neon green T-Shirt with neon green sneakers to match, and a baseball cap that read ‘I’d Rather Be Fishing.’

Professor Ooben nodded in approval and ticked a check on the clipboard. “That is actually quite accurate tourist attire.”

“Ha ha! I knew it!”

“Don’t get too confident, young one. We land in sixty seconds, so put on your clothing and get ready to order your beverage without anyone suspecting that you are not one of their kind. I will be watching from a booth at the restaurant. Do not mess this up. This is your last chance to pass my class.”

Professor Ooben stepped over to the spaceship’s controls, and landed it into a parking spot on the street in front of the soda shop. The humans on the sidewalk stopped walking, mouth agape, in complete shock. Professor Ooben had anticipated this reaction, so she knew just what to do. She rolled down the window and shouted from the inside, “Just picked up this new Tesla last week! It’s self-flying. Pretty cool, huh?”

The people on the street admired the vehicle and shared “oohs and ahs” for a while until going back to their ice cream eating and mindless shopping.

“Nice save, Ooben,” Andrew said as he stepped out of the vehicle.

“That is Professor Ooben to you. Get ready. Your Occasion starts the minute you walk through that door.”

Andrew stood in front of the wooden door of the soda shop. Truthfully, in the deepest depths of his four hearts, he knew he did not have a great chance of passing this exam. He had not paid any bit of attention to Professor Ooben for the entire year, and this was his second year taking Earth Assimilation 101. However, he knew that he needed to try his best, because there was nothing he wanted less than a life covered in moon dust while mining for gems.

He took a deep breath to relax his nerves, and immediately coughed. “Why is Earth’s air so putrid?”

“It’s the pollution. Now get in there and do your best. I believe in you,” Professor Ooben said, patting him on the shoulder.

“Really? You believe in me?” Andrew asked.

“No. But why not give it a try anyway?” Professor Ooben said.

Andrew looked back at Professor Ooben with a squinted eye, and pushed his way through the door. Professor Ooben hid four of her arms under her extra-large sundress and discretely made her way to a booth in the back corner of the soda shop. She made sure to exaggerate her movements as she settled onto the bench, pretending that her pink skin was just an extremely intense sunburn. As she pretended to examine the menu, Andrew stood in line.

The soda shop was full of rambunctious children and clueless adults that stumbled around with little purpose. The wooden floorboards felt sticky, and there were flashing neon signs that lined up along the walls. Professor Ooben was used to tacky American establishments, but Andrew had never experienced such strange and disgusting sensations.

Andrew listened to how the human customers ordered their drinks to prepare for ordering his own. A lot of the customers asked for things unfamiliar to Andrew, such as “Coke,” “Fanta,” and “Root Beer.” After they asked for their drinks, the pimply teenage boy at the front would fill clear plastic cups with brown or orange liquid that fizzled and popped. Andrew could smell how sickly sweet the drinks were from where he stood, causing him to gag. He held in his vomit though, knowing that the acid content in his alien stomach would burn a hole in the floor. On Home Planet, they enjoyed a thick, dark purple beverage that was rather tasteless, yet full of nutrition. He figured that a shop specifically made to sell all types of beverages would carry something similar, so he decided to order that rather than those gag-worthy sugar drinks.

After the woman in front of Andrew ordered and obtained her “cream soda,” Andrew stepped up to the front.

The teenager at the counter looked at Andrew with wide eyes. Out of politeness, he said nothing, but Andrew knew enough about humans to know that he would not be able to continue this interaction without explaining his strange form. Andrew had already forgotten what Professor Ooben told him to say when somebody was curious about his eye, but he did remember what not to say. “Well, my spotty-faced

friend, it seems you want to know what happened to my eye. A dog didn’t eat it. That’s what happened!”

“Uhh… okay?” the teenager said as his astonishment turned into confusion and then indifference, not even craving an explanation for his green skin.

Professor Ooben shook her head and added yet another “X” to the clipboard.

“Well, what can I get for you today?” the teenager asked.

“This store has lots of drinks, yes?” Andrew asked nervously.

“Yes. It does.”

“Wonderful, wonderful. Because I was wondering, do you have any purple beverages?”

“You mean grape soda?”

“Is it purple?”

“Yeah, it’s purple.”

“How purple?”

“Dark purple, I guess. You can sample it if you’d like.”

“No, dark purple is perfect. I will not need a sample.”

“Are you sure? We have these little sampling cups,” the teenager said, showing Andrew a stack of tiny white paper cups.