THE TURNING POINT

During the twentieth century designed jewellery moved away from impersonal settings of gemstones to become innovative as a personalised medium of style. The period 1945-1961 saw several fresh approaches in continental jewellery aesthetics. For example, in Scandinavian Modernism, Nanna Ditzel and Henning Koppel designed for the artistically progressive Danish company, Georg Jensen and the Swiss watchmakers, Patek Phillippe, appointed the creative Gilbert Albert to design its new modern range. In Britain, however, this period revealed the poor state of its manufactured jewellery. The austere aftermath of the Second World War with its heavy purchase tax on the wholesale price of luxury goods, aimed at reducing raw material wastage, lingered on as a mantle in the jewellery trade in the 1950s.

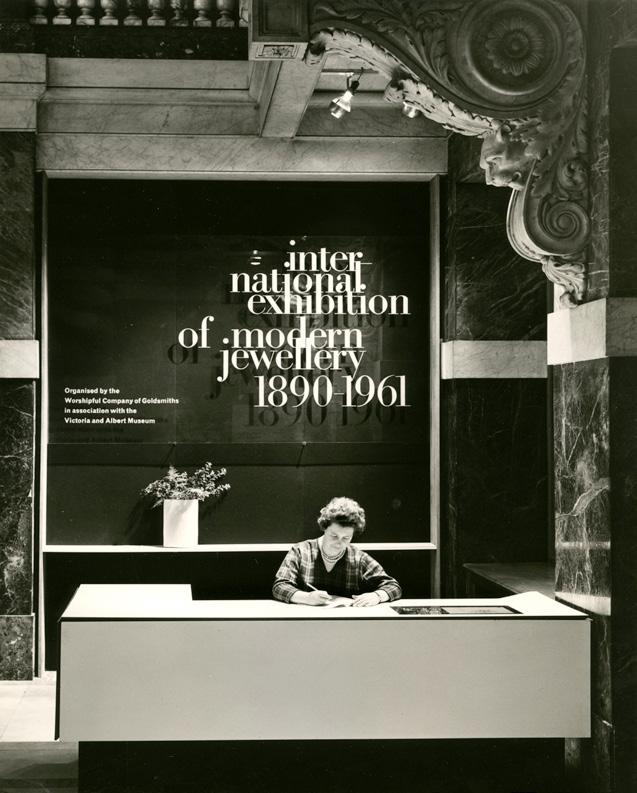

The turning point for British resurgent artist jewellers was the unique patronage of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths. In 1961, at Goldsmiths’ Hall, the Company held the landmark ‘International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery 1890-1961’, showing 901 exhibits that traced the evolution of modern jewellery design. The exhibition’s intention was ‘To raise the status of the artist jeweller and revitalise jewellery design.’ De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd. sponsored

Transitioning from the 50s to 60s

Introduction by Rosemary Ransome Wallis, Art Director and Curator, The Goldsmiths’ Company,1972-2017

a competition to seek out contemporary jewellery designs to exhibit that were ‘both experimental and beautiful, frankly belonging to 1961, as uninhibited as modern sculpture or fashion….’ This milestone exhibition showed the craft’s potentiality, particularly to the young pioneering artist jewellers, John Donald and David Thomas who opened their own London boutiques. Andrew Grima (19212007) opened his Mayfair gallery in 1966. He became internationally well-known as a jeweller with a client list of British Royalty, film stars and celebrities like Jacqueline Onassis.

By the end of the 1960s experimentation was an established trend in modern jewellery design. There was a baroque randomness of form and surface with the use of modern vacuum and centrifugal lost wax casting techniques allowing permutations of abstract textures in precious metals. There was an awareness of modern movements in architecture, sculpture and painting. Thus, the organic beauty of crystalline structures of uncut stones was rediscovered and stylishly expressed in creative jewels. Indeed, the 1960s notion that jewellery is a medium for expressing artistic individuality is its legacy today.

1

A GOLD AND GEM-SET BROOCH, BY

BEN ROSENFELD, 1962

modelled as a fish, its collar claw set with sapphires and with a cabochon turquoiseset eye, London hallmarks to reverse 4.5 cm. long

3

A GOLD AND GEM-SET PENDANT, BY

HANS GEORG MAUTNER,

1960 modelled as a scorpion, its body formed by an oval cabochon of lilac chalcedony, with ruby set eyes, London hallmarks to reverse 4.4 cm. long

2

A GOLD AND GEM-SET BROOCH, BY

HANS GEORG MAUTNER,

1962

modelled as a fish, its body set with a circular lilac chalcedony cabochon, with cabochon ruby-set eye, London hallmarks to reverse 3.5 cm. long

4

A GOLD, SAPPHIRE AND DIAMOND-SET BROOCH, BY ANDREW GRIMA FOR H J COMPANY, 1962

Two of the textured foliate sprays claw-set with round mixed cut sapphires, one claw-set with round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks to reverse 8.1 cm. long

A GOLD, SAPPHIRE, DIAMOND AND PEARL SET BROOCH, BY ANDREW GRIMA

FOR H J COMPANY, 1965

formed of three stylised, openwork textured leaves, two claw set with sapphires and one claw-set with diamonds, centred by three cultured pearls, London hallmarks to side 3.6 cm. diam.

5

5

A GOLD, RUBY AND DIAMOND-SET BROOCH, BY ANDREW GRIMA FOR H J COMPANY, 1962 of flower form, claw-set with cabochon rubies and round brilliant cut diamond stamen, London hallmarks to reverse 6.6 cm. long

6

A GOLD AND DIAMONDSET BROOCH, BY HANS GEORG MAUTNER, 1969 formed as a of interwoven rope-twise knot design, interspersed with claw-set round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks to reverse

7

8

A PAIR OF GOLD, CITRINE AND DIAMOND SET EARCLIPS, BY HANS GEORG MAUTNER, 1964

each formed as an openwork cushion centred by clusters of four round mixed cut citrines and four round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks on reverse and to clips each 1.8 cm. diam.

9

A GOLD, CITRINE AND DIAMOND-SET BROOCH, BY HANS GEORG MAUTNER, 1965

formed as a textured flower-head, the centre claw-set with round mixed cut citrines and round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks to reverse 3 cm. long

10

A GOLD, RUBY AND DIAMOND-SET BRACELET, BY BEN

ROSENFELD,

1965

formed as a series of bombé ropetwist links, each set with graduations of circular-cut rubies or brilliant-cut diamonds, London hallmarks to clasp 19.3 cm. long

11

A PAIR OF GOLD AND DIAMOND SET EARCLIPS, BY HANS GEORG MAUTNER, 1963

Of oval, multi rope-twist form, the centre of each claw set with three round brilliant cut diamonds, clip fittings, London hallmarks to reverse each 2.3 cm. long

12

A GOLD, RUBY AND DIAMOND-SET BROOCH AND PAIR OF EARRINGS, BY

BEN ROSENFELD, 1964

each formed as an openwork cluster of fluted curls, claw-set with ruby and diamond clusters, London hallmarks to reverse the brooch 3.5 cm. long; the earrings 2.2 cm. long

13

A GOLD, TURQUOISE AND DIAMOND BROOCH, BY

ALAN GARD, 1966

in the form of a flower centred by a turquoise cabochon and round brilliant cut diamond cluster, the textured undulating petals with scattered claw set turquoise cabochons, the curved stem with a round brilliant cut diamond, London hallmarks to reverse 5.8 cm. long

14

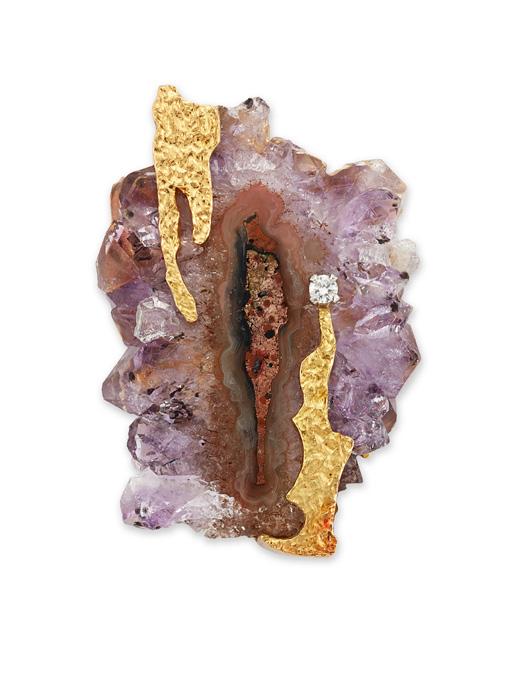

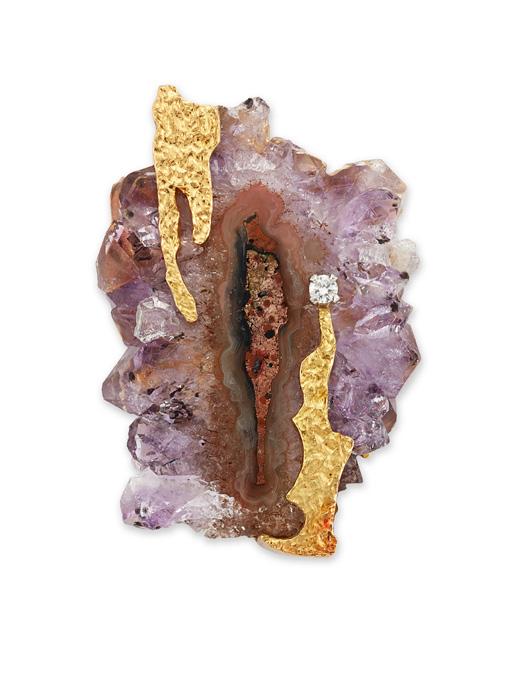

A GOLD, AMETHYST AND DIAMOND SET BROOCH, BY ANDREW GRIMA, 1969

the rough amethyst crystal applied with two abstract textured panels of gold, one claw-set with a round brilliant cut diamond, London hallmarks to reverse and signed ‘GRIMA’ 4 cm. long

DIAMONDS IN THE ROUGH:

Crystals and Rough Gem Materials in British 1960s Jewellery

by Kate Flitcroft, FGA

The visionary jewellery designers of the 1960s did for British jewellery what Christian Dior did for fashion in the previous decade. Dior’s designs flaunted full skirts of silks and luxurious fabric, challenging the austerity of post-war Paris, and ushering in a fresh style (his ‘New Look’). In post-war Britain, the door of creativity was firmly shut to the jewellery industry. Graham Hughes’ groundbreaking ‘International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery’ cracked open that door, allowing designers like Andrew Grima, John Donald and Gilian Packard to burst through with floods of flexibility and ingenuity, specifically in their use of materials and working techniques.

Jewellers used a range of gemstones in both rough and faceted forms, often subverting previous stones in their treatment of more ‘humble’ materials. For example, Andrew Grima’s amethyst and diamond set brooch (1969, no. 14) is led by the undulating banding at the centre of the amethyst crystal. The rough gem material is applied with textured, naturalistic gold panels of a similar form. The panels are set to frame the banding; their form is suggestive of a stalagtite and stalagmite, with the single claw-set round brilliant cut diamond as a drop of water glistening at the top of the mineral formation. The rough crystal is not just a stage for precious stones. It is used in a more characterful manner, reminiscent of the early 18th century baroque pearl figures by Johann Heinrich Köhler in Dresden’s Grünes Gewölbe, where the impression of the pearl dictates the character of the figure.

In John Donald’s gold, sapphire and diamond set bracelet (1968, no. 24), the crystal form is implied through metalwork. The bracelet is formed of a lattice of small textured gold cubes, scattered with square mixed cut sapphires and round brilliant cut diamonds. The six-sided cubic form and horizontal striations mimic the rough crystal form of pyrite (‘fool’s gold’). The overall design is led by the crystal form; but Donald goes one step further. His playful approach elevates ‘humble’ pyrite, subverting the nature of the ‘precious’ materials used for the bracelet. Donald’s starburst brooch (1963, no. 26) and spinel ring (1967, no. 23) continue his use of geometric crystal forms, albeit with the crystals present.

Gilian Packard’s use of rough rhodochrosite in her 1967 pendant (no. 28) and cometshaped brooch (1968, no. 37) demonstrate the continued use of crystals and rough in the period, as do Grima’s druzy agate pendant/brooch (1965, no. 21) and fluorite brooch (1967, no. 25). Jewellers of the period were fully engaging with the crystal form, often in subversive and playful ways. Their designs broke away from the traditional use of gem materials, contributing to the fresh ‘new look’ of British jewellery in the 1960s.

15

A GOLD, DIAMOND AND EMERALD SET PENDANT/BROOCH, BY

ANDREW GRIMA

FOR H J COMPANY, 1964

Formed of loosely woven, tapering textured openwork ribbons, three claw-set with emeralds, and four set with diamonds, with detachable carved emerald drop, London hallmarks to rib and emerald drop 6.9 cm. long

A GOLD BROOCH, BY ANDREW GRIMA, 1968

of abstract form with textured bark finish, London hallmarks on reverse and signed ‘GRIMA’ 8 cm. long

16

17

A GOLD AND GEM-SET BROOCH, BY HANS GEORG MAUTNER, 1968 of textured openwork teardrop form, claw set with rubies, sapphires, emeralds and diamonds, to a hinged pin fastening, London hallmarks on reverse 3.8 cm. long

18

A GOLD AND DIAMONDSET RING, BY GEORG WEIL, PURCHASED 1967 cast and textured bombé abstract form claw-set with seven round brilliant cut diamonds, to a polished hoop

19

A GOLD, EMERALD AND DIAMOND-SET RING, BY ANDREW GRIMA, 1964

bombé with granulation, collet set with a rectangular shaped cabochon, and clawset with a round brilliant cut diamond, London hallmarks inside hoop

20

A GOLD, EMERALD AND DIAMOND-SET PENDANT/BROOCH, BY ANDREW GRIMA, 1968

Of abstract, grandulated, openwork form, set with ten carved oval cabochon emeralds, and claws-set with nine round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks to side, the reverse signed ‘GRIMA’ 6.4 cm. wide

21

A GOLD AND GEM-SET PENDANT/BROOCH,

BY ANDREW GRIMA FOR H J COMPANY, 1965

the druzy agate set with carved and cabochon rubies and emeralds, highlighted by round brilliant cut diamonds, with a textured cast foliate mount, London hallmarks on reverse 6.2 cm. long

In 1966, Andrew Grima won the Queen’s Award for Export and the Duke of Edinburgh Prize for Elegant Design. His winning collection included a brooch set with carved rubies from an Indian jewel and was purchased by HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (b. 1921) for HM Queen Elizabeth II (b. 1926).

It was most recently worn for their Platinum wedding anniversary portrait, November 2017. The present pendant/brooch (cat. 21) is set with rubies carved in a similar manner to those present on the Queen’s brooch, suggesting they come from the same source.

22

A

GOLD, TOURMALINE AND DIAMOND SET BROOCH,

BY

ALAN GARD, 1968

of textured, openwork, abstract form, claw-set with four rectangular cut tourmalines and round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks to reverse 7 cm. long

A GOLD, SPINEL AND DIAMOND

RING, BY JOHN DONALD, 1967 of openwork textured form, the centre set with a spinel crystal and three eight-cut diamonds, London hallmarks inside hoop

23

24

A GOLD, SAPPHIRE AND DIAMOND SET BRACELET, BY

JOHN DONALD,

1968 each panel applied with scattered, textured gold cubes and set with squarecut sapphires and round mixed cut diamonds, London hallmarks to clasp 16.3 cm. long

A GOLD, FLUORITE AND DIAMOND SET BROOCH,

BY ANDREW GRIMA, 1967 the druzy fluorite crystal within an openwork gold mount designed as scattered matted and polished triangles, claw set with four round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks on reverse and signed ‘GRIMA’ 4.5 cm. long

25

AN AMETHYST SET BROOCH, BY JOHN DONALD, 1963

Of starburst form, the radiating square section rods with granulation and centred by an amethyst crystal, reverse with pin and revolving clasp fitting, London hallmarks to reverse 5.5 cm. long

In his book, Precious Statements: John Donald, Designer Jeweller Donald explains the process of granulation. He ‘was trying to use the ancient method, dating back at least two thousand years, of copper plating both the plain surface and the gold filings’ (Precious Statements, p. 74).

Through a process of experimentation, Donald learned how to ‘melt small areas of gold or other metals in a reasonably controlled way’, ultimately perfecting the granulation technique.

Literature:

John Donald and Russell Cassleton Eliott,

Precious Statements: John Donald, 2015, p. 74.

Illustrated:

John Donald and Russell Cassleton Eliott,

Precious Statements: John Donald, 2015, fronticepiece and p. 74.

On loan from the collection of John and Cynthia Donald

26

In his book, ‘Precious Statements: John Donald, Designer Jeweller’ Donald explains the process of granulation. He ‘was trying to use the ancient method, dating back at least two thousand years, of copper plating both the plain surface and the gold filings’ (Precious Statements, p. 74). Through a process of experimentation, Donald learned how to ‘melt small areas of gold or other metals in a reasonably controlled way’, ultimately perfecting the granulation technique.

THE EXPERIMENTAL AGE

“When I started in the mid-to-late 1950s, there were very few new things being made in jewellery… Innovation just hadn’t happened for 20 years, partly because of the war, so in design terms one could do anything at all. It was a completely open book” - John Donald

In a decade of revolution, from the Civil Rights Movement to the first man to step on the moon, to the hippie movement, fashion followed suitnotably Pierre Cardin’s 1964 Space Age collection and Paco Rabanne’s science-fiction trends. Cosmic themes were more literal in high street fashion (shooting stars, planets and rocket motifs) - reflecting the new glamour of figures such as Jackie Kennedy, psychedelic fashion and the new Atomic space age.

Essay by Philip Smith Associate Director Modern Art & Design, Lyon & Turnbull

The cultural revolution in British taste did not escape the young budding makers of the 1960s: a whole generation of new jewellers, most living on hand-to-mouth existences in small studios cum living spaces, all epitomes of the counterculture revolution and reactionaries to the status quo. These ‘artist jewellers’ were imbued with a freedom to pursue themes through diverse new forms in design not influenced by the past, dispensing with tradition motifs for abstract often asymmetrical and geometric designs, using unusual colours. The flaming star (John Donald’s brooch, no. 26) and comet (Gilian Packard pendant, no. 37) were appropriately popular motifs during this ‘Space Race’ period and perfectly fitted the notions of how these jewellers were trying to represent a Modern Age. Most importantly the work of this period showed what could be done with jewellery, and how it could be visionary - transcending from commerce into an art form relevant to contemporary society, that allowed it to be exhibited alongside work of the most avant-garde artists of their day.

27

A GOLD AND DIAMOND-SET BROOCH, BY

ANDREW GRIMA,

1969

of abstract openwork geometric form, pavé set with eight-cut diamonds, London hallmarks to reverse and signed ‘GRIMA’ 4.2 cm. wide

The pierced abstract form of this brooch reflects the influence of Grima’s friend and client, Barbara Hepworth. In 1931 Hepworth pierced a hole in a small carving, allowing more flow to the form. Later in her life she reflected, ‘when I first pierced a shape, I thought it was a miracle...A new vision was opened.’ Hepworth was one of the artists invited to sculpt a piece of jewellery from wax for the International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery 1890-1961.

28

A TWO- COLOUR GOLD AND RHODOCHROSITE PENDANT, BY GILIAN PACKARD, 1967

the rough crystal set within a two tone gold polished and textured bar and nugget style setting, suspended from a similarly designed fancy link chain necklace with gold nugget style spacers between, London hallmarks to side of pendant the pendant 6.5cm long; the necklace 65.7 cm. long

A SILVER AND TOURMALINESET PENDANT/BROOCH, BY ROD EDWARDS, 1965 of oval concave form, collet set on raised arched supports with an oval green tourmaline cabochon, with detachable tapering bale and fancy link chain, London hallmarks to reverse of pendant, further stamped ‘Rod Edwards’ to pendant, bale and chain the pendant/brooch 6.6 cm. long; the neckchain 58 cm. long

29

30

A GOLD, RUBY AND DIAMOND-SET RING, BY CHARLES DE TEMPLE, 1966 of tapering, textured bombé form, pavé set with a panel of round brilliant-cut diamonds and roundcut rubies, further claw-set with round brilliant cut diamond accents, London hallmarks inside hoop

31

A GOLD AND DIAMOND-SET RING, BY ANDREW GRIMA, FOR H J COMPANY 1964 cast with textured ridges and claw-set in-between with three rows of round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks inside hoop

32

A GOLD AND PEARL-SET BROOCH, BY DAVID THOMAS, 1965 formed as a cluster of hemispherical gold cups, some centred by a cultured pearl, London hallmarks to reverse 5.3 cm. long

33

A GOLD, CORAL AND EMERALD-SET RING, BY ANDREW GRIMA, 1969 set with four marquise shaped coral cabochons and centred by two claw-set round mixed cut emeralds, London hallmarks inside hoop and signed ‘GRIMA’

A GOLD AND DIAMOND SET RING, BY ANDREW GRIMA, 1968

of textured, openwork abstract design, set with eight-cut diamonds, London hallmarks inside hoop and signed ‘GRIMA’

34

35

A TWO-COLOUR GOLD AND BERYL SET RING, BY CHARLES DE TEMPLE, 1969 of broad tapering form with textured wire-work, claw set with a round mixed cut pale yellowish green beryl, London hallmarks inside hoop and signed ‘CdeT’

36

A GOLD AND AMETHYSTSET RING, BY ALAN GARD, 1968

cast and textured, claw set with a cushion cut amethyst and five round brilliant cut diamonds, London hallmarks inside hoop

AND DIAMOND SET

PENDANT, BY GILIAN PACKARD, 1968

the rose quartz crystal set within tapering gold batons, claw-set with five marquisecut diamonds, London hallmarks to reverse 4.5 cm. long

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am most grateful to the anonymous private collector who generously lent pieces and enthusiastically committed time to this project. In addition, I’d like to thank John Donald for the loan of his brooch, allowing us to see his granulation technique first-hand.

It is an honour to have Louisa Guinness contribute the introduction. Her expertise on jewellery by artists dovetails very well with this exhibition and her book ‘Art as Jewellery’ is a wonderful reference. The rise of ‘artist jewellers’ in the British jewellery trade was largely brought about by the 1961 International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery at Goldsmiths’ Hall, and it is marvellous to have the perspective of Rosemary Ransome Wallis on the turning point between the 1950s and 1960s.

I would also like to thank Harriet Scott at Goldsmiths’ Hall, Sandy Stanley and Jon Stokes Photography. I am grateful to the Directors of Lyon & Turnbull for supporting this project; to Philip Smith for contributing his essay, but also his time, ideas and creativity in the planning stages; and finally, my colleagues Matt McKenzie, Alex Dove, Jess Curnow and Matthew Yates for their help with the catalogue, marketing and logistical support.

This exhibition is a window into an exciting decade of jewellery design and a glimpse of a much larger collection. I hope that jewellery from this period continues to be available for us to see and learn from.

Kate Flitcroft

October 2019

Donald, John Edwards, Rod Gard, Alan Grima, Andrew

Hans Georg Packard, Gilian

Scott, Tom de Temple, Charles Thomas, David Weil, Georg

INDEX BY MAKER

MAKER

Mautner,

Rosenfeld, Ben

No. 23 24 26 29 13 22 36 4 5 6 14 15 16 19 20 21 25 27 31 33 34 2 3 7 8 9 11 17 28 37 1 10 12 38 30 35 32 18 INDEX BY YEAR YEAR 1960 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 No. 3 1 2 4 6 11 26 8 12 15 20 31 5 9 10 21 29 32 13 30 18 23 25 28 16 17 19 22 24 34 36 37 7 14 27 33 35 38

LYONANDTURNBULL.COM

| EDINBURGH | GLASGOW

LONDON

© Edgar Hyman 1961

© Edgar Hyman 1961

5

5