Published annually by Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary, Cordova, Tennessee, Michael R. Spradlin, President.

Published annually by Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary, Cordova, Tennessee, Michael R. Spradlin, President.

Michael R. Spradlin, PhD

Terrence Neal Brown, MLS, Editor, Book Review Editor

Van McLain, PhD

Candi Finch, PhD

Elisabeth Gehman, Collin McAdams, Editorial Assistants

Cayman Blount, Joshua Weaver, Technical Assistants

The Journal of Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary is published each spring under the guidance of the Journal Committee of Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary.

Correspondence concerning articles, editorial policy and book reviews should be addressed to the editor, Terrence Brown (tbrown@mabts. edu). Manuscripts for consideration should be sent to the Editor. Writers are expected not to question or contradict the doctrinal statement of the Seminary.

The publication of comments, opinions, or advertising herein does not necessarily suggest agreement or endorsement by Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary, Journal Committee, or the Trustees of the Seminary.

The subscription rate for the print edition of The Journal is $10.00 per year. The rate is for mailing to domestic addresses. The Seminary does not mail The Journal internationally, but makes it available worldwide through its online edition. The online edition is available free of cost at www. midamericajournal.com. Address all subscription correspondence to: Journal Committee, Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary, P.O. Box 2350, Cordova, TN 38088.

© 2023 Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary

ISSN: 2334-5748

“Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary is a school whose primary purpose is to provide undergraduate and graduate theological training for effective service in church-related and missions vocations through its main campus and designated branch campuses. Other levels of training are also offered.”

Dedication

Dr. James Powell

Reflections: Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary

Michael Spradlin

Symposium Program

The Egyptian Background of the Exodus

Edwin Yamauchi

The Departure from Egypt and Egyptian Toponyms

James Hoffmeier

Raamses, Succoth and Pithom

Ken Kitchen

The Expulsion and Pursuit of the Hyksos

Gleason Archer

Exodus: The Ancient Egyptian Evidence

Hans Goedicke

The Amarna Letters and the "Habiru"

Ron Youngblood

1935-1991

Suddenly, on the morning of December 30, 1991, when most of the family of Mid-America Seminary was still enjoying the afterglow of Christmas and looking forward to the New Year, Dr. James Edwin Powell, Associate Professor in New Testament and Biblical Introduction at Mid-America, collapsed at his home and died of a heart attack.

Dr. Powell has taught at MABTS since 1978. In his years at the Seminary he earned his doctorate, served as Director of Library Services--overseeing, in a crucial period, the planning for the current Allison Library--and taught Greek and Biblical Introduction in the New Testament Department. He was a deacon, a Brotherhood Director, and taught adult men's Sunday School at the First Baptist Church, Collierville, TN, where he was a member. He served as president of the local chapter of the Near East Archaeological Society and as treasurer of the National Near East Archaeological Society. [in the office of Director of Library Services he had been a member of the Tennessee Theological Library Association and completed a two year term as President.]

The above are facts concerning the life of Dr. James E. Powell. They are, like flesh, part of the public view, the outside man. But James Powell was far more varied and complicated than a mere list of duties, memberships, accomplishments, and positions. Like everyone, he reflected more than what could be observed on the outside. The important aspect of James Powell came from within, that which came from his heart and his faith in the salvation of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Dr. T. V. Farris said at the funeral of Dr. Powell, "James Powell has written his own eulogy with his character." Dr. Farris noted that, above all else, James Powell was a man "dedicated to his Lord, to his family, to the Seminary where he served, and to his church." In this dedication to those causes which he held to be precious, dear, and paramount, James Powell demonstrated a "kind, gracious and gentle spirit" to all people and in all things.

When we read the obituaries and hear eulogies and praises, we look about us in this life and consider what James Powell left behind. We pray for Mrs. Powell and the beloved children, Alva and Jameson, and for his brothers and sisters. We remember what James Powell accomplished in his career: students educated; his planning and superintending of the splendid Exodus Symposium that delighted him and so many other scholars; chapel addresses filled with insight, holiness, and practicality;

pop tests; a gift of laughter in friendship and Christian love; the rapid and tender appraisal of new library books; an encouraging word for faltering students and tired colleagues; preaching and witnessing to the lost; dry humor that was never base or cruel; and the list goes on and on.

Dr. Farris observed that James Powell was "compassionate, gracious, generous almost to the point of flaw. He was a noble man. And in every sense of the term a genuine Christian gentleman." In his funeral sermon, Dr. Gray complimented James Powell with the highest praise that can be attributed to any christian: "He was not ashamed of Jesus. I've never known him to be ashamed of Jesus nor to act as if he were.”

In conclusion, for this earth, perhaps the sweetest words that can be written of Dr. James Edwin Powell, a sinner saved by grace, are words that Dr. Powell himself wrote for the Mid-America Theological Journal on the great Southern Baptist teacher, A. T. Robertson, in studies in honor of Dr. Roy Beaman. "He is one in whom genuine love for knowledge is evident without ostentation and who saw the real worth of his own life in the success of his students. . . My own life will count for much or little in proportion to how well these men and women do the work which God has placed in their hands. I love them with my whole heart." To paraphrase James Powell on A. T. Robertson, therein lies the key to the esteem with which Dr. Powell was regarded by his students. The servant has departed this realm; praise and all glory to God in the highest

Reprinted from Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary Messenger January 1992.

Michael R. Spradlin, PhD, President of Mid-America Baptist

Theological Seminary, received a BA from Ouachita Baptist University, and an MDIV and PhD from Mid-America Baptist

Theological Seminary. He has a versatile ministry background that includes preaching, teaching, church planting, military chaplaincy, and many international and North American mission trips. In addition to serving as the president, Dr. Spradlin is also professor of Old Testament and Hebrew, church history, practical theology, and missions and chairman of the evangelism department. He is the author of many scholarly articles and books, including The Sons of the 43rd: The Story of Delmar Dotson, Gray Allison, and The Men of the 43rd Bombardment Group in the Southwest Pacific. Dr. Spradlin served as editor of Studies in Genesis 1-11: A Creation Commentary, Beaman’s Commentary on the Gospel of John, Personal Evangelism and That One Face: The Doctrine of Christ in the First Six Centuries of Christianity. Dr. Spradlin and his wife Lee Ann live in Memphis and have three children (David, Thomas, and Laura) and two daughters-in-law (Laurel and Madelyn) and a son-in-law (Cody).

Before, they were just names on the front of books to me. I hardly thought of them as people but only as the purveyors of information that I must learn to get through the next hurdle of seminary. I did not see my time in seminary as an academic endeavor but as a time to learn the Bible. Leaving the Master of Divinity degree and headed into the Doctor of Philosophy degree, I had chosen Old Testament and Hebrew as my focus. This study encapsulated my passion for the Scriptures, love for languages, fascination with history, and curiosity of the obscure all in one package. Then came the conference. I first heard of the conference, “Who was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?“, from my Old Testament professors. Larry Walker was an expert in Semitic languages and a member of the translation committee of the New International Version of the Bible. T. V. Farris had a unique gift

for creative communication and made preaching from the Hebrew Old Testament an exegetical party (in a good way). David Skinner explained the nuances of Hebrew grammar on the one hand and instilled confidence in the inerrancy of the Scriptures on the other. Steve Miller was the first person I ever heard delineate liberal, neo-orthodox, and conservative theology in an understandable way and convince you that the conservative view was the only truthful way to read the Bible. Although he was not a part of the Old Testament department, James Powell explained the contributions of archaeology and how these insights could bolster the case for biblical inerrancy.

I never chose to go to the conference; I and my fellow students were told that we were required to attend. Motivation and leadership all in one. I was enrolled in several classes that led up to the conference, and one of the key discussion points was something called “bichrome ware pottery.” It had not occurred to me to think about what this phrase even meant until someone put up a color picture of pottery with two colored bands around the rim. So much for archaeological acumen on my part.

Among the many luminaries that spoke, several made a deep impression on me. The first was Hershel Shanks, the editor of Biblical Archaeology Review (BAR), who spoke at the kickoff dinner. The second was Cyrus Gordon who spoke “off the cuff” in one session and detailed things about the Bible that I had never realized. Finally, Kenneth Kitchen made the biggest impression. I ended up in a small group walking with him at the Ramses the Great exhibit (the conference was planned to coincide with the Memphis Wonders Exhibit, Ramses the Great, showing of the Ramesside artifacts). As we walked, he read the hieroglyphs and explained the meanings of each and told humorous anecdotes as well.

The conference ended and, as students, we moved on with our studies. Unknown to us, several challenges derailed the project to publish the papers presented during this event. It was a dream of MABTS professor James Powell, tremendous admirer of William F. Albright, to see the project to its completion, but he passed away before he could complete the work.

The papers languished in files for years until the intrepid work of Terrence Brown, Director of the Ora Byram Allison Memorial Library, brought them to my attention, and we decided to finish the dream of James Powell.

Because of the length of time involved, we have made several editorial decisions. We attempt to present papers exactly as presented, with little or no editing. I know that the format for transcribing ancient words has changed in the intervening decades, but we have striven to maintain the form used at the time of the conference. Also, further archaeological evidence has been published which may shed additional

light on the matters at hand. We have chosen to avoid updating the materials and to leave them as they were presented at the time of the conference.

We hope that this project will fulfill the original intent of those MABTS professors who labored to bring the conference together. We further hope that these papers will continue to spark an interest into the field of Near Eastern Archaeology, especially as it pertains to the Bible and its rich history.

The Symposium WHO WAS THE PHARAOH OF THE EXODUS?

THURSDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 23

1:30 Registration

2:30 Introductions

3:00 The Egyptian Background of the Exodus

Edwin Yamauchi

3:45 The Departure from Egypt and Egyptian Toponyms

James Hoffmeier

THE EGYPTIAN EVIDENCE

4:30 Raamses, Succoth and Pithom

5:15 Break

THURSDAY EVENING, APRIL 23

Ken Kitchen

5:15 – 6:30 BANQUET Holiday Inn Crowne Plaza Dining Room

7:00 The Expulsion and Pursuit of the Hyksos

7:45 Exodus: The Ancient Egyptian Evidence

8:30 Tour of Ramesses Exhibit

FRIDAY MORNING, APRIL 24

8:00 The Amarna Letters and the “Habiru”

Gleason Archer

Hans Goedicke

Ron Youngblood

THE WILDERNESS EVIDENCE

8:45 Tracks in Sinai

9:30 Break

10:00 Another Look at Transjordan

10:45 Egypt to Canaan

11:30 Critique

12:00 Adjourn

Itzhaq Beit-Arieh

Gerald Mattingly

William Shea

THE CONQUEST EVIDENCE

FRIDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 24

1:30 A Survey of Theories

2:15 The Witness of Ai

Bruce Waltke

Maxwell Miller

3:00 Break

3:30 The Identity of Bethel and Ai

4:15 Critique

5:00 Adjourn

FRIDAY EVENING, APRIL 24

David Livingston

7:00 Jericho Revisited: The Archaeology and History of Jericho in the Late Bronze Age

7:45 Israelite Occupation of Canaan

Bryant Wood

Rivka Gonen

8:30 Hyksos Influence in Transjordan and Palestine-Canaan Adnan Hadidi

9:15 Adjourn

SATURDAY MORNING, APRIL 25

8:00 The Southern Campaign of Joshua 10

8:45 Canaan’s Middle Bronze Age Strongholds

Gordon Franz

John Bimson

9:30 Break

10:00 The Destruction of Canaanite Lachish and Hazor:The Archaeological Evidence

David Ussishkin

10:45 The Palestinian Evidence for a Thirteenth Century Conquest: An Archaeologist Appraisal

Bryant Wood

11:30 Critique

12:15 Adjourn

SATURDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 25

1:30 Egypt, Israel and the Mediterranean World

Cyrus H. Gordon

SUMMARY

2:15 Who Was the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

3:15 Critique

4:15 Conclusion

5:00 Adjourn

Hans Goedicke

J. Maxwell Miller

John Bimson

Edwin Yamauchi

Each of the following presentations—essays—from the Exodus Symposium carry biographical sketches for the presenters from 1987, the time of the Symposium. While we understand some of the speakers from 1987 have died, others retired, and a few remain teaching and writing, in keeping with the spirit of The Journal’s effort in reproduction of the 1987 gathering, we have retained the brief biographical identifications from that time.

Professor of History, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. Ph.D., Brandeis University, Research in Gnosticism; Ancient Magic: Old and New Testaments. Editor-at-large of Christianity Today Publications include: The Stones and the Scriptures and PreChristian Gnosticism.

Miami University Oxford, OH 45056

A. Introduction

It is my privilege to seek to establish the broad context in which our panel of distinguished scholars will address particular problems relating to Egypt, the Old Testament, and archaeology. As we are approaching rather complex issues with fragmentary evidences which may be interpreted in different ways, we shall probably not be able to reach any kind of consensus. But we should be able to clarify the problems, and to present the current status of research.

1. Geography

The significance of Palestine in the ancient world was in large measure its function as a land bridge between the two major areas of Egypt and Mesopotamia. I am reminded of the status of New Jersey, which functions as the highway between Philadelphia and New York. The Via Maris, or international highway, went east across the northern Sinai, along the Palestinian coast, then inland through the Megiddo Pass, and then east to Damascus.

Egypt itself was accurately described by Herodotus, the Father of History, who visited it in the 5th century B.C. He called it “The Gift of the Nile.” Then and even now over 90% of the population have been restricted to the fertile ribbon of green on either side of the Nile. The Nile, which is 4,000 miles long, is the only major river which flows from south to north. This explains why Egyptians considered the area upstream to the south Upper Egypt, and the region to the north by the delta Lower Egypt. The predictable annual floods helped replenish the

land. The height of the flood determined whether there would be plenty or famine in the land. Usually the Egyptians had an abundance of food, both in terms of grain and meat.

The Egyptians also were blessed with minerals and building materials. The pyramids were constructed from limestone blocks quarried from across the river. Obelisks were carved from granite monoliths quarried at Aswan. Supplies of gold from Nubia gave the impression to rulers abroad that gold was as plentiful in Egypt as sand on the ground.

On either side of the Nile are vast stretches of desert. On the west we have the extension of the Sahara Desert and on the east the Arabian Desert.1 These deserts together with the cataracts in the south protected Egypt on all sides except the north.

2. Writing

The Egyptians were the first after the Mesopotamians to develop writing about 3,000 B.C. There were several systems of writing which were employed. The most famous are the hieroglyphics, which are pictograms and ideograms, that is, signs of various objects. These signs represent consonants, syllables, and concepts. An early cursive or script form was hieratic. The later script, developed from about the 7th cent. B.C. was demotic. Some of the latter signs were incorporated into the largely Greek script of post-Christian Egyptian known as Coptic.

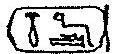

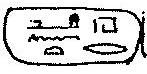

The hieroglyphs were deciphered by a young Frenchman, Champollion, in 1822 with the aid of the famous Rosetta Stone. This stone was discovered by one of Napoleon’s soldiers in 1799 at the Rosetta or western branch of the delta. As Napoleon was defeated by the British, the stone became the prized possession of the British Museum. It dates from the Ptolemaic era, and contains three panels: in hieroglyphic, in demotic and in Greek. Champollion guessed that the hieroglyphic signs in the oval cartouches were the royal names, Ptolemy and Cleopatra. Though we know the value of the consonantal signs, we are still not sure of the vowels. Hence, we often have a variety of English spellings, e.g. for the god of Thebes as Amen, Amon, Amun.

3. Language

The Egyptian language is known as a Hamito-Semitic dialect, with relations to such Semitic languages as Hebrew on the one hand, and to African languages as Hausa in Nigeria. A number of Egyptian words were borrowed by Hebrew. Some of these are objects such as puk for “eye paint” from the Egyptian word for turquoise or malachite, which was ground to form an eye shadow powder, and shesh for “linen.” The word Ye’or, which originally meant the Nile came into Hebrew as a general word for “river.” The word “pharaoh” comes into the English language through a Hebrew transliteration of the Egyptian parcoh, which literally meant “Great House,” and then the king. The proper name Susan

comes through Hebrew from an Egyptian word for “lily.” 2

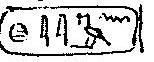

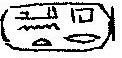

The Egyptians called their own land either kmt [or Kemet] “Black Land,” TAWY “The Two Lands” (i.e., Upper and Lower Egypt), or NFR TA “The Beloved Land.” The Hebrew name of Egypt was misrayim. The English name Egypt comes from the Greek, Aigyptos, which is a transliteration of the Egyptian Hust-ka-Ptah, “Mansion of the Ka of Ptah.” Ptah was the creator god of the city of Memphis; his Ka was his double. The Egyptian name of the city of Memphis was Mn-nfr “Established and Good,” which was later preserved in Coptic as Mempi, which gives us the name “Memphis.” The name of the city was transcribed as moph in Hebrew as in Hosea 9:6 or as noph in Isaiah 19:13.

The Egyptians kept very good records, which are the basis of ancient near eastern chronology. When a discrepancy was discovered between the Egyptian dates and radio-carbon dates, it was the latter which needed to be corrected.3 Most of our documentation comes from royal texts, which are, of course, propagandistic. They boast of victories and never mention defeats. Other texts are self-laudatory tomb inscriptions of officials. We have a number of literary texts such as the famous story of Sinuhe, wisdom sayings like the biblical Proverbs,4 and love songs like the Song of Solomon.5 More mundane documents have occasionally survived on papyri and ostraca, i.e. broken shards of pottery. Egyptian archaeology has concentrated its efforts on tombs and temples in Upper Egypt.5a With the exception of the short-lived site of Amarna, we have little evidence of dwellings.6 Most of the papyri and other perishable materials have been preserved in the dry climate of Upper Egypt; they perished in Lower Egypt. The Greeks obtained their papyri from Egypt through the Phoenician port of Byblos. They then called their scrolls or books “biblos,” which has given us the word “Bible.” Unfortunately no papyri have been recovered at Byblos. In another work I wrote:

Every temple in Egypt had papyri records describing its personnel and their tasks month by month. From a small temple at Abusir we know that it would have taken ten meters of papyri per month or 120 meters per year to list such records. If we were to estimate that there were only one hundred temples in Egypt, and were to multiply this times the 2,000 year period from 2500-500 B.C., we could calculate (120 x 100 x 2,000) that the Egyptians must have used a total of 24 million meters of papyri for their temple records. Of this grand total the only temple records that have been recovered are thirteen meters from Abusir and a similar length from Ilahun.7

In view of the fragmentary survival of the evidence and the accidental nature of its discovery, we must be extremely cautious about coming to negative conclusions from arguments from silence.

It has been customary to divide Egyptian history into epochs according to the dynasties recorded by an Egyptian priest, Manetho, who lived in the third century B.C. It is not always easy to match his Greek names with the Egyptian names.8 Herodotus, who is important for the later dynasties, did learn the correct names of the builders of the three pyramids at Giza: Cheops for Khufu, Chephren for Khafre, and Mycerinus for Menkaure. Complicating the process of identification was the fact that each pharaoh had at least two and often five royal names. Let me briefly sketch the course of Egyptian history, using approximate rather than precise dates, and then seek to relate the biblical events to their possible Egyptian contexts.

1. Archaic Period (Dynasties I-II, 3200-2700)

Egyptian history began with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by a king named Menes. He has been identified by some as the king whose hieroglyphic symbol is the cuttlefish--Narmer, by others as Horus or the Scorpion.9 The main monuments of this era are mastaba or “bench-like” tombs. Incised hieroglyphs of Narmer have been found in Palestine.10 Scholars do not agree as to whether the Egyptian objects in Palestine are evidences of political control or merely of trade. The latter seems to be the more correct inference.11

2. Old Kingdom (Dynasties III-VI, 2700-2200)

The capital of this period was the Lower Egyptian city of Memphis. The Old Kingdom is sometimes known as the “Pyramid Age,” as this is when the famous pyramids were built.12 The first pyramid which was built was the Step Pyramid of Djoser of the IIIrd Dynasty built at Saqqarah, near Giza. The first true pyramids were built by Sneferu of the IVth Dynasty, who was obviously experimenting as he built three pyramids.13 The most famous pyramids are the three at Giza, with the nearby Sphinx. The great pyramid of Cheops is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the World which has survived. Contrary to the views of the popular writer, E. von Daniken, the pyramids as marvelous as they are, were not built by ancient astronauts.14 And despite the public pronouncements of a certain Israeli prime minister, the pyramids were not built by his Hebrew ancestors.

3. The First Intermediate Period (Dynasties VII-X, 2200-2040)

The size and grandeur of the Old Kingdom pyramids were never duplicated. It has often been supposed that the vast expenditures of wealth and manpower necessary for their construction led to the succeeding era of chaos and decline, though an examination of the texts does not lend support to this thesis.15 The weakening of the pharaoh’s power is shown in the fact that there were four ephemeral dynasties within a century and a half. This era, however, and the next are regarded as the Golden Age of Egyptian literature.

4. The Middle Kingdom (Dynasties XI-XII, 2040-1790)

The center of power shifted south to the Upper Egyptian city of Thebes (called Luxor today) during the Middle and the New Kingdom eras.16 Although this was a time of prosperity, few of the monuments of this era have survived as the later pharaohs of the New Kingdom demolished the buildings and reused their materials. During the Middle Kingdom the Egyptians established their southern frontier at the second cataract. Excavations there at the fortress of Buhen uncovered a skeleton of a horse, demonstrating that horses were not introduced into Egypt by the Hyksos. Execration texts, which are magical curses upon Egypt’s enemies, give us invaluable information about Palestine during this period.17 Again whether Egyptian involvement in Palestine during this period implied political hegemony or trade is disputed.18

5. The Second Intermediate Period (Dynasties XIII-XVII, 17901570)

The security of Egypt was shattered in the 17th century by the successful invasion of the Hyksos, Semitic invaders from the east who were equipped with chariots.19 The unity of Egypt was also lost as several contemporary dynasties ruled over different parts of Egypt. The Hyksos gained control of Lower Egypt. Though they adopted Egyptian customs, they were resented and eventually expelled through the leadership of the Thebans (XVIIth Dynasty). The papers by Gleason Archer and Adnan Hadidi will focus on the Hyksos.

6. The New Kingdom (Dynasties XVIII-XX, 1560-1085 B.C.E.)

Rebounding from the humiliation of the Hyksos occupation, the Egyptians decided that their best defense would be an aggressive imperialism. The New Kingdom, also known as the Empire period, was the acme of Egyptian power and influence.20 Egyptian armies tramped across Palestine and reached the Euphrates River.21 This was the era of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs, including from the XVIIIth Dynasty: Hatshepsut (1479-1457), Tuthmosis III (1457-1425), Amenophis IV or Akhenaten (1356-1340) and Tutankhamun (1340-1331). From the XIXth Dynasty, the most famous pharaoh was Ramesses II (1279-1213), followed by his son Merenptah (1213-1204).22

Hatshepsut was a queen, who ruled as a regent for her stepson when her husband died. But she enjoyed power so much that she continued to rule on, even when Tuthmosis III came of age. She even arrogated to herself many of the titles of a pharaoh and was depicted with a beard. Hans Goedicke has recently proposed the novel view that the Exodus took place under her reign.23

Once he was free to exercise power, Tuthmosis III, who is sometimes called the “Napoleon” of Egypt, unleashed his energies in a series of campaigns in Palestine and Syria, including a memorable battle at the Megiddo pass.24

One of the most extraordinary figures in Egyptian history was Amenhotep IV, or as he was to call himself Akhenaten.25 His wife was the beautiful Nefertiti. Akhenaten’s promotion of the monotheistic worship of the sun disc, the Aton, has been compared with Mosaic monotheism.26 He built a new capital at Amarna, where exactly a century ago a peasant woman found a collection of tablets now known as the Amarna Letters.27 Though they were at first thought to be forgeries, they turned out to be an invaluable archive of correspondence between Amenhotep III and IV, and kings of Mitanni, Assyria, Babylonia, and Palestine. Cyrus Gordon will speak about this international era. 28

Of special interest are the pleas from the kings of such cities as Jerusalem, begging for Egyptian military aid against the marauding Habiru (cited as Apiru in Egyptian texts). The aid was not forthcoming evidently because of Akhenaten’s preoccupation with his religious reforms, and the Egyptian Empire came into danger of disintegration.29 Though earlier scholars sought to identify the Habiru with the biblical Hebrews (‘ibrim), the Habiru are attested over a larger area than the Hebrews and a simple equation is not possible.30 Ron Youngblood will be speaking on this subject.

The fabulous treasures discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 in the unlooted tomb of Tutankhamen, has made King “Tut” universally famous.31 As he was but a minor king who died in his teens, one wonders what the treasures of a truly great pharaoh might have been!

The new Ramesside XIXth Dynasty had its roots in the delta region, and so built its capital of Per-Ramesses there under the great Ramesses II. Ramesses II was an outstanding builder, who worked on a monumental scale, such as his colossal fourfold statues which were rescued from the waters of Lake Nasser at Abu Simbel near the border with Sudan, and his enormous hypostyle temple at Karnak (Thebes).32 He was also active in other ways, as he sired over 100 sons and daughters! In his fifth year Ramesses II fought a major battle at Qadesh in Syria against the Hittites and their allies. Both sides claimed victory. Eventually they realized the futility of further fighting and signed the world’s first international peace treaty.

In the reigns of two of the next kings, Merenptah (1213-1204) and Ramesses III (1185-54) Egypt was assaulted by waves of the so-called Sea Peoples from the Aegean, who included the Philistines. These years marked the decline of Egyptian imperial power.

C. EGYPT AND THE HEBREWS

1. The Patriarchs

Abraham and Jacob turned to Egypt in times of famine. This may have been during the Middle Kingdom. The succoring of eastern Semites by the Egyptians is confirmed by an illustration from the Vth Dynasty (2500 B.C.E.), which shows a group of starving bedouin.33 At the

end of the XVIIIth Dynasty Semites came to the border of Egypt and begged to be given food “after the manner of your father’s father since the beginning.” At Beni Hasan there is a colorful depiction of Asiatics (i.e. Semites) bearing gifts and products into Egypt.34

2. The Joseph Story

It is especially the story of Joseph (Gen. 37-50), which is filled with Egyptological data, such as the “embalming,” i.e. the mummification of Jacob (Gen. 50:1-3).35 Though many scholars would place Joseph in the Hyksos period, the biblical data suggests a Middle Kingdom date. Kitchen favors a date c. 1700 in the XIIIth Dynasty, just before the arrival of the Hyksos.

Joseph’s sale as a slave into Egypt can be illustrated by the Wilbour Papyrus of the Brooklyn Museum (1740 B.C.), which lists about a hundred slaves, half of whom were “Asiatics.”36 His interpretation of dreams may be understood from an Egyptian manual of dream interpretation (Chester Beatty Papyrus I), which cites as an example: “if a man sees himself in a dream turning his face to the ground, bad (cf. Gen.40:9).”37 His exaltation by the grateful pharaoh can be paralleled from the numerous tomb inscriptions of high officials.38

Inasmuch as some of the Egyptian data, such as the proper names in the Joseph story, are not attested until relatively late, their value for authenticating the narratives has been disputed. On the one hand, D. Redford in his detailed study has opted for the latest possible dates (7th century and later).39

Much of Redford’s case, as he himself recognizes, is based on arguments from silence. Other Egyptologists, such as J. Vergote40 and K. Kitchen41 believe that the Egyptological data in the story can be reconciled with a Ramesside date.

The Hebrew Bible (Gen 15:13; Exod 12:40) indicates that Jacob and his descendants sojourned in Egypt for about four centuries. The Septuagint tradition (Exod 12:40) seems to suggest that they were in Canaan for two centuries, and only in Egypt for two. One would calculate backwards from the date of the Exodus to determine the descent of Jacob into Egypt.42 On the “long” chronology, this would have been in the 19th cent. according to the Early Date and the 17th cent. according to the Late Date of the Exodus. As our other speakers will explain, there are two possible dates for the Exodus:

a. The Early Date, c. 1450 either in the reign of Tuthmosis III or Amenophis II.

b. The late Date, c. 1270-60 in the reign of Ramses II. The only reference to Israel in Egyptian text comes from the 5th year of the reign of Merenptah.43

Notes

1. Kees (1961).

2. Gardiner (1936); Lambdin (1953); Williams (1969); Yahuda (1933).

3. Yamauchi (1975).

4. Bryce (1979); Fontaine (1981); Kitchen (1977); Ruffle (1977); Williams (1961) & (1981).

5. Carr (1982); Fox (1980) & (1983); Foster (1974); White (1978).

5a. Bietak (1979).

6. On the Amarna Palace see Yamauchi (1984).

7. Yamauchi (1981), p.157.

8. See Gardner’s Appendix (1961).

9. Emery (1961).

10. Amiran (1974) & (1976); Yeivin (1963).

11. Gophna (1976); Wright (1985).

12. Aldred (1965).

13. Edwards (1961).

14. Yamauchi (1974).

15. Kanawati (1980).

16. Riefstahl (1964); Kamil (1976).

17. Sethe (1926); Posener (1939) & (1966).

18. Weinstein (1975).

19. Van Seters (1966).

20. Steindorff and Seele (1957).

21. Weinstein (1981).

22. Kitchen (1982), pp. 238-39. Kitchen has ruled out the high chronology of (1304-1238) on the basis of new Babylonian dates, though he concedes that the lower chronology of 1290-1224 is still a possibility.

23. Oren (1981); Shanks (1981) & (1982).

24. Nelson (1913).

25. Aldred (1968); Redford (1984).

26. On the alleged influence of Akhenaten’s influence on Moses, see my paper, “Akhenaten, Moses, and Monotheism,” delivered at the Midwest AOS Arnarna Centennial.

27. Pfeiffer (1963).

28. Gordon (1965).

29. Several (1972).

30. See my article on the “Habiru,” in Blaiklock and Harrison (1983), pp. 223-24.

31. Hoving (1978).

32. MacQuitty (1978).

33. For general works relating the Bible to Egypt see: Aling (1981); Kitchen (1959-60); Montet (1968).

34. Shea (1981).

35. Davis (1986); Yamauchi (1986), p. 160, n. 125.

36. Hayes (1955).

37. Israelit-Groll (1985); Janssen (1955-56).

38. Ward (1960).

39. Redford (1970).

40. Vergote (1959), (1972) & (1985).

41. Kitchen (1961) & (1973).

42. Hoehner (1969); Ray (1986).

43. Engel (1979); Kitchen (1968).

Bibliography

Aldred, C.

1965 Egypt to the end of the Old Kingdom. New York: McGrawHill.

Aldred, C.

1968 Akhenaten, Pharaoh of Egypt. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Aling, C.

1981 Egypt and Bible History. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

Amiran, R.

1974 “An Egyptian Jar Fragment with the Name of Narmer from Arad.” IEJ 24:4-12.

Amiran, R.

1976 “The Narmer Jar Fragment from Arad: An Addendum.” IEJ 26:45-46.

Bietak, M.

1979 “The Present State of Egyptian Archaeology.” JEA 65:15660.

Blaiklock, E. M. and Harrison, R. K., ed.

1983 New International Dictionary of Biblical Archaeology Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Bryce, G. E.

1979. A Legacy of Wisdom: The Egyptian Contribution to Wisdom of Israel. Lewisburg: Bucknell University. Carr, L. G.

1982 “The Love Poetry Genre in the Old Testament and the

Ancient Near East.” JETS 25:489-98.

Davis, J.

1986 The Mummies of Egypt. Winona Lake: BMH Books.

Edwards, I. E. S.

1961 The Pyramids of Egypt. Baltimore: Penguin Books.

Emery, W. B.

1961 Archaic Egypt. Baltimore: Penguin Books.

Engel, H.

1979 “Die Siegstele de Merenptah.” Biblica 60:373-99.

Fontaine, C. E.

1981 “A Modern Look at Ancient Wisdom.” BA 44:155-60.

Foster, J.

1974 Love Songs of the New Kingdom. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Fox, M. V.

1980 “The Cairo Love Songs.” JAOS 100:101-10.

Fox, M. V.

1983 “Love, Passion, and Perception in Israelite and Egyptian Love Poetry.” JBL 102:219-28.

Gardiner, A.

1936 “The Egyptian Origin of Some English Personal Names.” JAOS 56:189-97.

Gardiner, A.

1961 Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gophna, R.

1976 “Egyptian Immigration into Canaan during the First Dynasty?” TA 3:33-37.

Gordon, C. H.

1965 The Ancient Near East. New York: W. W. Norton.

Hayes, W. C.

1955 A Papyrus of the Late Middle Kingdom in the Brooklyn Museum. New York: Brooklyn Museum.

Hoehner, H.

1969 “The Duration of the Egyptian Bondage.” BS 126:306-16.

Hoving, T.

1978 Tutankhamun: The Untold Story. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Israelit-Groll, S.

1985 “A Ramesside Grammar Book of a Technical Language of Dream Interpretation.” pp. 71-116 in S. Israelit-Groll, ed., Pharaonic Egypt: The Bible and Christianity. Jerusalem: Hebrew University.

Janssen, J.

1955-56 “Egyptological Remarks on The Story of Joseph in Genesis.” Ex Oriente Lux 14:63-72.

Kamil, J.

Luxor: A Guide to Ancient Thebes. New York: Longman.

Kanawati, N.

1980 Governmental Reforms in Old Kingdom Egypt. London: Aris & Phillips.

Kees, H.

1961 Ancient Egypt. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Kitchen, K. A.

1959-60 “Egypt and the Bible: Some Recent Advances.” Faith and Thought 91:177-97.

Kitchen, K. A.

1961 Review of J. Vergote, Joseph en Egypte in JEA 47:158-64

Kitchen, K. A.

1968 Ramesside Inscriptions IV.1. Liverpool: University of Liverpool.

Kitchen, K. A.

1973 Review of D. Redford, A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph in Oriens Antiquus 12:233-42.

Kitchen, K. A.

1977 “Proverbs and Wisdom Books of the Ancient Near East.” TB

28:69-114.

Kitchen, K. A.

1982 Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramses II. Mississauga: Benben Publications.

Lambdin, T. O.

1953 “Egyptian Loan Words in the Old Testament.” JAOS 73:14555.

MacQuitty, W

1978 Ramesses the Great. New York: Crown.

Montet, P.

1968 Egypt and the Bible. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Nelson, H. H.

1913 The Battle of Megiddo. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Oren, E. D.

1981 “How Not to Create a History of the Exodus--A Critique of Professor Goedicke’s Theories.” BAR 7.6:46-53.

Pfeiffer, C. F.

1963 Tell el Amarna and the Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

Posener, G. 1939 “Nouvelles listes de proscription… datant du moyen empire.” CE 14:39-46.

Posener, G.

1966 “Les textes d’envoutement…” Syria 43:277-87.

Ray, P. J.

1986 "The Duration of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt.” AUSS 24:231-48.

Redford, D.

1970 A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Redford, D.

1984 Akhenaten: The Heretic King. Princeton: Princeton University.

Riefstahl, E.

1964 Thebes in the Time of Amunhotep III. Norman: University of Oklahoma.

Ruffle, J

1977 “The Teaching of Amenemope and Its Connection with the Book of Proverbs.” TB 28:29-68.

Sethe, K.

1926 Die Achtung feindlicher Fursten, Volker, und Dinge auf altagyptischen Tongefasscherben des mittleren Reiches. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

Several, M. W.

1972 “Reconsidering the Egyptian Empire in Palestine during the Amarna Period.” BASOR 104:123-33.

Shanks, H.

1981 “The Exodus and the Crossing of the Sea according to Hans Goedicke.” BAR 7.5: 42-50.

Shanks, H.

1982 “In Defense of Hans Goedicke.” BAR 8.3:48-3.

Shea, W. H.

1981 “Artistic Balance among the Beni Hasan Asiatics.” BA 44:219-28.

Steindorff, G. and Seele, K.

1957. When Egypt Ruled the East. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Van Seters, J.

1966 The Hyksos. New Haven: Yale University.

Vergote, J.

1959 Joseph en Egypte. Louvain: Publications Universitaires.

Vergote, J.

1972 Rev. of D. Redford, A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph in BO 29:327-30.

Vergote, J. 1985 “‘Joseph en Egypte’ 25 ans apres.” pp. 289-306 in Israelit-

Groll.

Ward, W. A.

1960 “The Egyptian Office of Joseph.” JSS 5:144-50.

Weinstein, J.M.

1975 “Egyptian Relations with Palestine in the Middle Kingdom.” BASOR 217:1-16.

Weinstein, J.M.

1981 “The Egyptian Empire in Palestine: A Reassessment.” BASOR 241:1-28.

White, J.B.

1978 A Study of the Language of Love in the Song of Songs and Ancient Egyptian Poetry. Missoula: Scholars Press.

Williams, R.J.

1961 “The Alleged Semitic Original of the Wisdom of Amenemope.” JEA 47:100-06.

Williams, R.J.

1969 “Some Egyptianisms in the Old Testament.” pp. 93-98 in G. E. Kadish, ed., Studies in Honor of John A. Wilson. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Williams, R.J.

1981 “The Sages of Ancient Egypt in the Light of Recent Scholarship.” JAOS 101:1-20.

Wright, M.

1985 “Contacts Between Egypt and Syro-Palestine During the Protodynastic Period.” BA 48:240-53.

Yahuda, A. S.

1933 The Language of the Pentateuch in Its Relation to Egyptian London: Oxford University.

Yamauchi, E.

1974 “’Chariots’ Is Just So Much Humbug.” Eternity 25.1:34-35.

Yamauchi, E.

1975 “Problems of Radiocarbon Dating and of Cultural Diffusion in Pre-History.” JASA 27:25-31.

Yamauchi, E.

1981 The Stones and the Scriptures. Reprint ed.; Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

Yamauchi, E.

1984 “Palaces in the Biblical World.” NEASB 23:35-67.

Yamauchi, E.

1986 “Magic or Miracle?” pp. 89-183 in D. Wenham and C. Blomberg, ed., The Miracles of Jesus. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

Yeivin, S.

1963 “Further Evidence of Narmer at ‘Gat’.” Oriens Antiquus 2: 205-13.

Associate Professor, Wheaton College, Ph.D., In Egyptian Religion, University of Toronto. Articles include: "The Evolving Chariot Wheel in the 18th Dynasty," Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, "Tents in Egypt and the Ancient Near East,"

S.S.E.A. Newsletter, Book Review of The Bible in its World, "Moses." Mediterranean, in International Standard Bible Encyclopedia.

The Hebrew tradition of the sojourn and exodus from Egypt are considered historical events by most archaeologists, biblical scholars and historians. John Bright (1961, 120) in A History of Israel sums up this view when he says;

There can really be little doubt that ancestors of Israel had been slaves in Egypt and had escaped in some marvelous way. Almost no one today would question it.

Although there is little consensus concerning when the sojourn began and ended, the events described in the book of Exodus appear to fit within the New Kingdom (ca. 1550-1200 B.C). The purpose of this study is not to enter the dating debate directly, rather, we propose to make brief examination of the Egyptian toponyms that relate to the exodus event, beginning with Raamses, the starting point (Exodus 12:37 & Numbers 33:5) and concluding with the incident at the Re(e)d Sea (Ex. 14 & 15).

Considerable discussion will be given to the yam suf/Red Sea problem, especially in light of the recent suggestion by B. Batto (1983) in the

Journal of Biblical Literature that we abandon the notion that the sea of passage was “the sea of reeds.”

The biblical sources that trace the march from Egypt to freedom in Sinai are found in Ex. 12:37, 13:17-20, 14:2 and the itinerary in Numbers 33. The latter is a lengthy list which traces the movements of the Hebrews from their departure from Raamses to the arrival in Canaan at the end of the “wilderness period.” The relationship between the toponyms in the Exodus passages and the list in Num. 33 have been the subject of considerable discussion. Ex. 12:37 is usually assigned to the Jahwist (J) by source critics (Noth 1962, 96-99), while 13:20 and 14:2ff. are thought to derive from the Priestly (P) source (Noth 1962, 109-110; Childs 1974, 220), and Ex. 13:17-19 is attributed to the Elohist (E) (Childs 1974, 220; Noth 1962, 106-107). The toponym list in Num 33 is thought to be a late compilation, the product of P, that may have utilized earlier material (Noth 1966, 242; Sturdy 1976, 227-226; Budd 1984, 352).

Recent form critical study of Num. 33 has concluded that this chapter is an itinerary (Coats 1972, 135-152; Walsh 1977, 20-33 Davies 1974, 46-81 & 1979). The itinerary of Num. 33 cannot be regarded as simply a compilation of the toponyms from other biblical sources, for it contains nearly twenty entries not attested elsewhere in the Pentateuch. Source critics consider lists written in a laconic manner to be the trademark of the Priestly School. By default, then, Num. 33 is attributed to P. But it should be noted that itineraries from the ancient Near East, be they Egyptian, Assyrian or Roman, exhibit a rather terse, formulaic style (Davies 1974, 52-78; Redford 1982, 58-60). Therefore, the nature of itineraries as a literary genre not the style “the Priestly School” seems to be the reason Num. 33 is written as it is.

In a recent study of the toponym list of Thutmose Ill at Karnak, D.B. Redford (1982, 59-60) has concluded that this list is a “group of itineraries for Western Asia as far north as the Euphrates.” An itinerary would help Egyptian couriers as well as military expeditions. Redford (1982, 59-60) further observes that itineraries were not just a list of cities, but included such geographical features as mountains, valleys, streams, and springs that would assist the traveler in finding his way to a desired location. It is worth noting that the Pentateuchal records include such geographical features. Ex. 14:2-3 “the sea” (hayam) and “the wilderness” (hammidbar), while Num. 33:9 mentions the same features and later in the journey it mentions that “at Elim there were twelve springs and seventy palm trees.” And subsequently various mountains are cited. Therefore, the material in the Pentateuch has many of the marks of a New Kingdom Egyptian itinerary.

Some caution is needed, however. Since the Hebrews were not intending to repeat the journey or return to Egypt, it does not appear that the purpose of the lists in the Pentateuch was the same

as Egyptian itineraries. The itinerary of Num 33 is introduced by stating that Moses recorded the trek by stages or encampments from the departure in Egypt through the arrival in Moab. But no reason is given for why. G.I Davies (1974, 47) argues that the purpose of this itinerary was “to bind into a single unit the whole complex of narratives from the Exodus to the Conquest.” G. Wenham (1981; 216-217) notes that this itinerary omits names found elsewhere in Numbers while adding others. If the beginning (Raamses) and the concluding points be illuminated, 40 names are recorded which might correspond to the 40 years in the wilderness (Num. 14:34). This may be a nice literary device or an interesting coincidence and nothing more. Wenham (1981, 217- 218) further observes that the list of 42 toponyms can be divided into six groups of seven and that “similar events recur at the same point in the cycle,” and the names might be arranged in numerically significant patterns which correspond to special occurrences. There is merit to these considerations and if they are correct, it might be conceivable that the itinerary served as a mnemonic for later writing of the narrative material in Exodus and Numbers.

This is not dissimilar to the Egyptian scribal practice of recording an expedition in the “day book of the king’s house”, which contained rather terse entries on a daily basis, but later was used to create more detailed narratives, hymns and annals, like those of Thutmose III.1

Having discussed the nature of the toponymic materials related to the departure from Egypt, we can now tum to the geographical questions. Since Professor Kitchen will be dealing with “The of Location Pithom and Raamses” in his study, my task of dealing with the starting point of the exodus is lessened and I defer to his conclusions on the matter.

There is little doubt that either the city of Pi-Ramesses or its environs, i.e. the Qantir-Avaris (Tell e-Debac), was the starting point of the exodus (cf. Ex. 12:37 & Num 33:3). Both Ex. 12:37 and the Numbers itinerary (33:5-6) agree that the first stop was Succoth. Hebrew Succoth has been equated with Egyptian tkw (cf. Bleiberg 1983, 21-27 for the history of the discussion; Helck 1965, 35ff.). The Pithom Stela of the Roman period suggests that tkw and pr-itm (Pithom) were located near each other (Bleiberg 1983, 21). The sites are clearly located within the Wadi Tumilat and Tell el Maskhuta (west of modern lsmailia) is thought to be Succoth (Redford 1963, 405-406; Davies 1979, 79). About 18 kilometers west of Maskhuta is Tell er-Retabeh, which is tentatively identified with Pithom (Redford 1963, 404-405; Davies 1979, 79).

Both of these Tells have been explored in recent years. Tell elMaskhuta, which has been more thoroughly excavated, has revealed Syro-Palestinian material of the Middle Bronze age (Holladay 1982). The picture from Tell er-Retaba is not as clear, and we anxiously

await a preliminary report. However, in verbal communications with the excavators2 there appears to be Late Bronze and Middle Bronze materials. This information squares with material from recent excavations at Tell e-Debac (Bietak 1975 & 1984) and Tell Basta, as well as what had been known for decades at Tell el-Vehudiah (Petrie 1906). It is increasingly evident that there was a sizeable population of Semites in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, and before. By traversing the Wadi Tumilat, the Israelites were taking one of the main routes to leave Egypt. Another reason for taking this route is that there may have been fellow Hebrews in the area of Pithom from the building projects there (cf. Ex. 1:11). Up until this point in the journey there is little debate about the route. But the next portion of the journey continues to provoke discussion and disagreement among scholars. Num. 33:6 reports that the stop after Succoth was Etham “which is on the edge of the wilderness,” which agrees with Ex. 13:20. The meaning of the word is obscure, which makes the location problematic. The Hebrew etam has been associated with the Egyptian htm (Cazelles 1955, 356), but this poses a linguistic problem. A shift from Egyptian h to Hebrew aleph is improbable (Davies 1979,79-80). If Etham could be positively identified it would greatly assist with the next cluster of toponyms, Pi-hahiroth, Migdal and Baal-zephon.

Scholars have been divided as to which direction the Israelites turned once they reached the eastern limit of the Wadi Tumilat. The biblical record agrees that they encamped next “in front of Pi-hahiroth, between Migdal and the sea in front of Baal-zephon (Ex. 14:2). Num 33:7 states, “And they set out from Etham, and they turned back to Pi-hahiroth, which is east of Baal-zephon; and they encamped before Migdol.” Differences in interpreting these names has resulted in scholars positing a “northern” and “southern” route for the departure from Egypt. Eissfeldt’s (1932) influential work on the subject has convinced some that Baalzephon is to be identified with the shrine of Zeus Kasios, located on Ras Qasrun on the Mediterranean coast (cf. Herrmann 1973, 60- 62 & Simons 1959 235ff. for a review of Eissfeldt). Simons (249 n. 217) finds Ras Qasrun an unattractive identification for Baalzephon. Many years ago, Sir Alan Gardiner (1920, 106-107; 1947, 202) pointed out that the Egyptian border fortress, htm n t3rw, Sile of the Antonian Itinerary, was equated in Hebrew by Migdol which means defense “tower” (BDB 153). The suggested location for this fort is Tell el-Ahmar, near modern El-Kantarah (Gardiner 1947, 202). Tell el-Her, about 10 k. north east of El-Kantarah is another proposed location for Migdol (Cazelles 1955, 344; Davies 1979, 82). The identification of Pi-hahiroth is problematic for the northern route scheme. In any event, the northern location for these toponyms makes Lake Sirbonis the obvious choice for the sea mentioned in Ex. 14:2, and probably the same body of water through which the Israelites passed.

In support of Lake Sirbonis, Strabo and Diodorus report problems various travelers had with changing water levels and becoming mired in the swampy soil (cf. Herrmann 1973, 60-62). While there are certain merits to this position, there are a number of problems. The first problem is that the distance between the sites identified with Migdol and Ras-Kasrun is about 50 kilometers, but the biblical statements seem to place these in closer proximity. Davies (1979, 82) observes that from the end of the Wadi Tumilat to Lake Sirbonis is about 144 kilomoeters, and yet only Etham is mentioned in the itinerary between Succoth and this location. For such a long distance to have only one entry in the Numbers itinerary seems inconsistent with the distance between stages recorded in the itinerary. Then too, the location of the sea in the biblical records appears much closer to the Succoth than Lake Sirbonis.

In view of Ex. 13: 17, which states “God did not lead them by the way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near...”, seems to preclude a northern route. “The way of the land of the Philistines,” has been associated with the military road, “the ways of Horus” which would have passed by Sile which led to Palestine (Gardiner 1920, 99ff.). Egyptian troops would undoubtedly have been stationed at Sile. The Egyptian Story of Sinuhe, which dates to the 20th Century B.C., indicates that when Sinuhe fled Egypt, he had to hide out from the “walls of the ruler” because sentries were posted (cf. Blackman 1932, 11-12 ANET 19). Quite naturally, the Israelites did not want to come to near Egyptian troops and the reason given for not taking the route was that the Israelites might see fighting and turn back (Ex. 13:17b). (De Vaux 1978, 376) believes that the Israelites would have avoided Sile because of the Egyptian military presence.

Another point against this northern route is that the Israelite destination was not Canaan, but Mt. Sinai (cf. Ex. 3:12), which is most likely situated in southern Sinai.3 But there may have been some maneuvering to avoid contact with other Egyptian outposts which might have taken them in a northernly direction for a brief time. The arrival at Pi-hahiroth, Baal-zephon, Migdol and the sea was reached after the Israelites “turned back” after leaving Etham (Num. 33:7; Ex. 14:2). Unfortunately, the word rendered “turn back”, sub does not mean turn left or right, or north or south (since they had been travelling east through the Wadi Tumilat). Simons (1959, 418 & 422) believes that a northern direction was taken after leaving the Wadi Tumilat which was subsequently reversed, which would have taken them southward.

The three toponyms of 14:2 have also been located in the region of the Bitter Lakes. Migdol could well be associated with another fort, not just Sile. According to Pap. Anastasi VI, 51-61 (Gardiner 1937, 76.13-15; Caminos 1954, 293; ANET 259) from the end of the 19th Dynasty (ca. 1200

B.C.) a fort is located near Tjeku (i.e. Succoth). Thus Migdal could be this fort.

The etymology and the location of Pi-hahiroth remains problematic. The element pi is suggestive of the pronunciation of Egyptian pr in the New Kingdom,4 as seen in the name Pithom and PiRamesses. Consequently, several Egyptian etymologies have been proposed. Pi-h(w)t-hr, “House of (the goddess) Hathor” (cf. Lambdin IDB 3, 810-811) and pi-hrrt, “House of (the goddess) Herret” are possibilities. While there is a goddess named hrrt (Wb III, 150), it is doubtful that she had a cult center in the eastern Delta.

Another possibility is to identify this name with a body of water, p(3) hrw, located near Tjeku, which is mentioned in the Pithom Stela (Cazelles 1955, 353).

Alternatively, if the root hrr/hrt is Semitic and not Egyptian, an intriguing possibility presents itself. In Akkadian from Old Babylonian onwards, hararu means “to dig (with a hoe),” “to groove” and when nominalized is written as harurtu (Chicago Assyrian Dictionary 6, 91). Hrt occurs only once in Hebrew (Ex. 32:16) and means “engrave” (BDB 362). In Ugaritic hrt means “to pIow” (Aisleitner 1974, 108) and “to scrape, to chisel” in Phoenician and Punic (Tomback 1976, 113). Words derived from the same root in Arabic are rendered “to bore or drill a hole” (H. Wehr, Arabic-English Dictionary, 231). These meanings suggest that a feature which had been dug, like a trench or canal, might be what is in mind. Cazelles (1955, 351) had entertained the possibility that a canal was the feature in question, but did not offer much support for the idea.

The element ha would be the definite article in Hebrew, while pi would be construct form of Hebrew peh, “mouth” (BDB 804-805). There is some support for this latter identification. The Septuagint (LXX) of Num. 33:7 renders Pi-hahiroth as “the mouth of lroth.” Furthermore, the Palestinian Targum of Jonathan Ben Uzziel (Ethridge 1968, 485) renders the toponym in question “the mouths of Hirathata,” but wrongly equated it with Tanis. It is simply called Ha-hiroth in Num. 33:8.

In English we use the term mouth to describe the opening of a river or stream, especially where it pours into a larger body of water. The Hebrew pi is used in the same manner (BDB 805), cf. Isa. 19:7 where it is used for the mouth of the Nile.

Is there any evidence for a canal in the region of the Bitter Lakes before the canal excavated by Neco and Darius in the Third Intermediate Period (cf. Herodotus II, 158). W. Ward (1971, 30-35) has argued, based on a statement in the “Wisdom for Merikare” (ca. 2200 B.C.), that a canal was begun by Merikare’s predecessor. The king was instructed to “dig a canal...flood its half as far as Lake Timsah (km wr)” to serve as a defense against Asiatics. John Wilson (ANET 417) has similarly understood 1.99 of “Merikare”, rendering it “Dig a dyke flood it as far as the Bitter

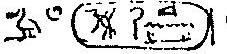

Lakes.” Other translators of this text have come to a different conclusion. Lichtheim (1975, 104) renders this critical line as “Medenyt has been restored to its nome, Its one side is irrigated as far as Kem-Wer (i.e. Bitter Lakes).”5 Helck (1977, 63) has interpreted this passage in like manner. The problem lies in whether the text should be read sd mdnit, or sd m(y) dnit. The former understands mdnit to be the Aphroditopolis or Atif, in the 22nd nome (Helck 1977, 63; Baines & Malek 1980, 14-15) just south of Memphis. Of the three manuscript witnesses of “Merikare” in Helck’s critical edition, only Papyrus Petersburg has all of this line completely preserved. The writing of the city determinative [?] after m dnit, suggests that the scribe who made this copy thought the city of Atif was meant. The exact reading of the text might be clarified if this line was extant in the other two manuscript witnesses.

Ward (1971, 30 n. 125) considers the m following sd to be the particle m(y) which is occasionally written after imperatives (cf. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar § 250). Dnit would mean canal, dyke or ditch (Wb V, 465). Since “Merikare” continues by indicating that this structure was meant for defensive purposes (cf. ll. 100-101) and included walls (inbw), Helck’s and Lichtheim’s interpretation does not fit the context as well.

An ancient canal was discovered in the eastern part of the Delta by the Geological Survey of Israel in the early 1970s (Sneh, et. al.). With the aid of aerial photography and ground surveying, the canal was determined to be man made because of the embankment dump and it measures a constant width of 70 meters at the top and 20 meters at the bottom and probably was 2-3 meters deep (Sneh, et. al. 1975, 543). The canal runs in a line south from Tell el-Farama, passing Tell Abu Sefeh (Sile) to the marshy El-Ballah region where it disappears. Sneh’s team concluded that this could well have served as a shipping canal connecting the Mediterranean, through the Wadi Tumilat, to the southern part of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile and may have run north from the Gulf of Suez where it would have joined the norther branch at the Wadi Tumilat. However, due to its size (the Suez canal cut by de Lessep is only 54 meters wide at the top), the Israeli team believes that its primary purpose was defensive, although irrigation would have been a secondary benefit. Sneh and his associates, for geological and historical reasons believe that this was not the Neco-Darius canal, although these later kings may have reused portions of the earlier one (1975, 544-546).

Long before the discovery of this canal, Gardiner (1920, 104 & plate XI) had interpreted a scene of Seti I’s as evidence for a canal connected with the border fortress of Sile. The victorious monarch is shown returning with prisoners from Palestine about to cross a narrow, crocodile infested body of water where he is greeted by loyal troops stationed there. The body of water is called t3 dnit, and dnit is what

Merikare is told to dig.

Sneh’s team believe that the canal they discovered is body of water on Seti’s relief from Karnak. They further argue that this body of water might be what is referred to in the Sinuhe story as the “Ways of Horus” which is mentioned in connection with the Sinuhe’s boat trip back to Egypt (cf. Sinuhe 11. 245-247; Blackman 1932, 35-36).

W. Shea (1977, 35-37) has reviewed the textual evidence and concurs with the Israeli geologists that the canal they discovered is the one depicted in Seti’s relief. Further, Shea (1977, 37-38) thinks that it was a part of the “Walls of the Ruler” which the “Prophecy of Neferty” announced would be built by Ameny (i.e. Amenemhet I, c.a. 1991-1961 B.C.) and encountered by Sinuhe on his flight from Egypt (Blackman 1932, 11). The Sinuhe Story calls the structure “the Walls of the Ruler which were made to repulse Asiatics and to trample the bedouin.” Sinuhe further reports that this structure, complete with sentries, was in the Bitter Lakes region which seems to rule out the Sile region. The walls could have been constructed from the embankment with guard houses placed on it at regular intervals.

Shea (1977, 35-37) argues that the canal Ward thought Merikare was instructed to dig to protect the Delta from further Asiatic incursion, was begun by Khety III, but doubts that Merikare continued the project. The reference to the “Walls of the Ruler” in the Sinuhe story from ca. 1960 B.C. suggests to Shea that the canal was extended and perhaps completed by Amenemhet I and was still functioning at the beginning of the 19th Dynasty.

T3 dnit, “the canal” might be equated with Hebrew Ha-hirot. The mouth of the canal, apparently would have been where the canal led into one of the lakes in the region. Lake Timsah was the terminus of the canal Merikare was instructed to make (1.99; Helck 1977, 61). Although Sneh’s team (1975, 546) believe that the section of canal between Timsah and El-Ballah, usually thought to be the Neco-Darius canal, could be traced back to an earlier date because its dimensions match the newly discovered northern canal. Apparently the Neco-Darius canal did not extend north of the Wadi Tumilat.

If indeed Pi-Hahiroth was this canal, dug to keep Asiatics out, it would have been an imposing barrier for the Israelites when leaving Egypt. This may explain why Pharaoh in Ex. 14:3 says of the escaping Hebrews “They are entangled in the land.”

The identification of Baal-Zephon remains problematic. Since the expression literally means “lord of the north” and is a deity in the Ugaritic pantheon and associated with Mount Casius just north of Ugarit (Albright 1968, 125; IDB I, 332-333), the origin of the expression is clearly Canaanite. Mention has been made above to Eissfeldt’s (1932) theory that Baal-Zephon be identified with Mount Casius, modern Ras Kasrun,

or Herodotus II, 6, 156 & III, 5. But Baal-Zephon need not exclusively be associated with mountains, since cult centers for this deity were located in Memphis and Tell Defneh (ISBE I, 381). Baal-Zephon is included in a list of gods in the “house of Ptah” in Memphis in the late Ramesside era (P. Sallier IV, verso 1,6; Gardiner 1937, 89:6-7). There is nothing in the biblical records to suggest that a mountain was associated with Baal-Zephon. But since Baal-Zephon is near “the sea” (Ex. 14:2 & 9; Num. 33:7-8) and this deity is associated with the sea and mariners (Albright 1968, 125), a shrine devoted to this god may be behind the toponym and not a mountain. The targums understand Baal-Zephon to be an idol (Etheridge 1968, 465). Therefore, a shrine of Baal-Zephon could have been located in the southern part of the isthmus of Suez, near the lakes and sea, just as one could have been in the Lake Sirbonis - Mediterranean region in the north.

The foregoing toponyms make up the route taken by the Israelites as they fled from Raamses to the sea of passage. Now let us look at the thorny problem of the identification of the sea.

In many of the passages the body of water through which the Israelites passed is simply called “the sea” (e.g. Ex. 14:2, 9, 16, 21, 23 etc.; 15:1 & 4; Num. 33:8). Elsewhere it is called yam suf in Hebrew (Ex. 13:18; 15:4 & 22). Varn suf, in recent decades, has been widely accepted as meaning “reed sea” and referring to one of the lakes between the Mediterranean and the Gulf of Suez, i.e. Red Sea (Bright 1961, 121; Herrmann 1973, 56-64; de Vaux 1978, 377).

Hebrew suf means reeds, rushes or some type of water plant (BDB 693; cf. Ex. 2:3 & 5; Isa. 19:6). In some cases the Septuagint (LXX) translates yam suf as “red sea” (Liddell-Scott, Greek-English Lexicon, 693). In classical sources this name applied to the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean (Liddell-Scott 693). Therefore, the association with the Red Sea, the northern segment of which is presently called the Gulf of Suez, is also thought to be a possible location for the crossing. Source critics contend that the problem lies in the conflation of multiple traditions present in the Pentateuch. Batto (1963, 35) maintains that P (the preiestly source, JEDP) in the 5th century B.C. was attempting to historicize and localize the rather ambiguous toponym “the sea” from earlier sources. For Batto, the body of water unquestionably is the Red Sea. He further observes that the Numbers itinerary makes it impossible for “the sea” and yam suf to be one and the same body of water. Num. 33:8 indicates that the Israelites passed through the sea near Migdol, Pihahiroth and Baal-Zephon, and then two stops later, after several days of travel, they reached yam suf (Num. 33:10). The problem posed by the Numbers itinerary has long been recognized. Jerome wrestled with this over 1500 years ago. We shall return to his solution to the problem later. Batto’s treatment of the source critical questions is fraught with

problems. If indeed yam suf is the Red Sea and P’s attempt to localize the event, how is it that Ex. 13:18, assigned usually to E (Noth 1974, 106107; Childs 1974, 220) mentions yam suf while 14:2ff thought to be P’s account (Noth 109-111; Childs 1974, 220) does not site this name. If P was responsible for localizing the event and giving us the name yam suf, then surely we would expect to find this name in Ex. 14.

In the “Song of the Sea” (Ex. 15:4) yam and yam suf occur in parallelism, and the “Song” is overwhelmingly thought to be one of the earliest pieces of Hebrew poetry, dating to the 13th Century.6 Batto (1983, 30 n. 13) accepts the early date of the “Song” but believes that at the latest stage of the tradition, P’s influence came to bear on the hymn. Why would Priestly redactors insert yam suf in Ex. 15, but not in Ex. 14 which is supposed to be P’s version of the exodus?

In Joshua 24:6 yam and yam suf are employed in parallelism and the judge Jepthah mentions yam suf (Ju. 11:16) and these occur in the so called “Deuteronomic History” which pre-dates P (Gray 1967, 7-8; Butler 1983, xxvii-xxix). Boling (1982, 533) considers Josh. 24:1-25 to be “pre-Deuteronomic.” Clearly source critical analysis has not aided our understanding of the events or route of the exodus. Some years ago, L.S. Hay (1964, 399), writing in JBL concerning the literary criticism of the exodus story said,

The literary critics, despite the air of assurance with which they individually proceed, have been unable to convince one another of the precise, or even approximate limits of the major constituent strata of the narrative.

Batto (1983, 27), while recognizing that the Hebrew word suf in Ex. 2:3 and Isa. 19:6 means reeds or rushes, declares that “The principal stay to this theory is the contention that yam sup should be translated as “Sea of Papyrus.” or “Sea of Reeds” because etymologically sup is a loanword from Egyptian twf(y) papyrus (reeds).”7 This statement is misleading at best and reflects ignorance of the exegetical history of the expression yam suf.

It was in this century that the association between the Egyptian and Hebrew words were made (cf. Gardiner 1947, 11 202*). The translation “Sea of Reeds” is not the result of Egyptological influence. Some of the Targums, which did not rely on the LXX, render yam suf as “sea of suph” in Ex. 15:4 and Num. 33:10 (cf. Targum of Onkelos & Targum of Jonathan, Etheridge 1968, 379, 331, 461).8 When Rashi wrote his commentary on Exodus at the end of the 11th Century A.D., he consulted the Targums and concluded that yam suf signified “a marshy tract in which reeds grow” (Rashi Exodus. 67). Writing over a century ago, Keil and Delitzsch (1869-70, 497) explained the reason for the name suf was “on account of the quantity of seaweed which floats upon the water and lies upon the shore.”

Another translation of yam suf which was completely ignored by Batto (1983) is the Coptic (Bohairic) translation of the Old Testament. While the Sahidic version follows the LXX and reads Red Sea, the Bohairic reads pyom n sa(i)ri. It has been suggested (Tower 1959, 152-153; Copisarow 1962, 4-5) that this means “sea of reeds or rushes,” deriving from Old Egyptian s i3r(w). Indeed Egyptian s means lake (Wb IV, 397) and i3rw means “reeds” or “rushes” (Wb I, 32). S i3r(w), “lake of reeds”, is well known from the Pyramid Texts (§§ 519 & 1421), along with sht i3r(w) “field of reeds” (PT §§ 275, 525-530, 981-989, 1132-1137, 1408-1415) as the place where the deceased king was purified in the celestial sea (cf. Hoffmeier 1981).

Other etymologies have been suggested for Coptic pyom n sa(i)ri because the expression “lake of reeds” apparently is not attested later than the Pyramid Texts. Cerny in his Coptic Etymological Dictionary (251) suggests that sa(i)ri derives from Egyptian h3rw, “Syrian.” But this meaning makes little sense at all in the Exodus passages for Syrian Sea, as in the Tale of Wen Amun (Gardiner 1937, 66.5), refers to the Mediterranean. Hcr is the root proffered by Westendorf in Koptisches Handworterbuch (324), which would mean “the sea of the storm.”9 This possibility is intriguing in light of the account in 14:21 which reports that a strong east wind caused the parting of the waters.

The Coptic (B) may support the “reed sea” hypothesis, it certainly does not support the name “Red” which is found in the LXX.

These sources, spanning from the beginning of the Christian era to Medieval times and down to the last century, all associate suf with some sort of swamp plant and none of these translators and commentators knew the meaning of Egyptian twf(y), except possibly the Coptic (B) translators. If anything, the association with the Egyptian word supports a Hebrew exegetical tradition.

The problem appears not to lie with the Hebrew suf but the LXX’s understanding of this term. Clearly the LXX has not translated the Hebrew word (Davies 1979, 70), if indeed it means reeds or rushes.

G.R.H. Wright (1979, 57) observes,

In short the Septuagint translators could have used eruthra because they knew (or thought they knew) that the Jews passed across these waters (whatever yam suf might stand for) or because they knew (or thought they knew) that yam suf in Hebrew designated the Red Sea (whatever waters the Jews passed through).

Put simply, the LXX translators may have thought that the body of water in question was the northern limits of the Red Sea. The LXX translators engaged in considerable speculation about Hebrew words that were obscure to them. Tradition has it that it was during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus the LXX was translated. Ptolemy II is well

remembered for his interest in geography and undoubtedly some of the geographical understanding of the age made its way into the LXX. It is true that yam suf refers not only to the miraculous sea of the exodus from Egypt, but also to the Gulf of Aqaba. The LXX of I Ki. 9:26 renders yam suf as “the extremity of the sea in the land of Edom.” In 1938, J.A. Montgomery (1938, 131-132) thought the LXX of I Ki. 9:26 might be the clue to understanding the meaning of sof. He suggested that the Greek (“the end”) was a translation of Hebrew sof which meant “end”. The Latin for the Indian Ocean is Ultimum Mare. Since the Red Sea is an extension of the Indian Ocean, the connection is obvious. A full reading of the LXX of I Ki. 9:12 reveals that Solomon’s fleet was located at Eloth “on the shore of the extremity of the sea in the land of Edom.”10 The Greek word for “red” is not used. Why in this case does the LXX scribes depart from the usual translation of suf?

Montgomery (1928, 131-132) and Snaith (1965, 395-398) suggested that they were translating the meaning of sof. But why they did it in this case while ignoring other references to the Gulf of Aqaba, is not explained. Interestingly enough, had they translated Hebrew Edom into Greek, it would have been purrhos, for red is what Edom means (cf. Gen. 25: 30; BDB 10). There still is no convincing explanation for the origins of the name “Red Sea” although a number of proposals have been made (Wright 1979, 55-57). But since through much of Israel’s history the area around the Gulf of Aqaba was controlled by the Edomites, it might locally have been called “the Edomite Sea.” Given the long rivalry between Israel and Edom, the Hebrews may have had a difficult time calling the Gulf of Aqaba by the name of their hated relatives. To remedy the problem, perhaps the Hebrews attached the name of the body of water on the other side of the Sinai peninsula to the Gulf of Aqaba.

Following Montgomery’s theory a step further, Snaith (1965, 395-398) suggested that the Greek term was a vague word for distant, remote locations. Snaith (1965, 397-398) then posited the presence of Canaanite mythic language in the “Song of the Sea.” These points greatly contributed to Batto’s conclusion.

It should be noted, that while the Greeks may have understood that the Red Sea connected to the Indian Ocean, the ultimate sea, there is nothing to suggested from the word used, which clearly means “red”, that it had anything to do with “the end” (Liddell Scott, Greek-English Lexicon 693). Therefore, it seems to be imprudent to rely on the LXX to provide the meaning of the name of the sea of passage or its location. Yam suf is used in Hebrew for the sea through which the Israelites passed (Ex. 13:18; 15:4; Josh. 24:6), the Gulf of Suez (Num. 33:10 & 11) and the Gulf of Aqaba (Ex. 23:31; Deut. 1:40, 2:1; I Ki. 9:26).

The LXX is not consistent in translating all occurrences of yam suf by

Erythra Thalassa. This has already been observed for 1 Ki. 9:26. Another interesting case is Ju. 11:16. Jephtah’s retrospective on the exodus, wilderness period to the conquest of the Trans-Jordan is very brief and one cannot be positive if he is referring to the sea of passage or the Gulf of Aqaba. Apparently due to this ambiguity, the LXX simply transliterated the name of the sea as Thalassa Sif (Towers 1959,150).

The LXX handling of I Ki. 9:26 and Ju. 11:16 ought to caution us in our use of the LXX to settle the geographical location of the sea of passage. Having said this, we still have not resolved the problem raised by Num. 33:8-10 which refers to the sea of passage as “the sea” and a location several days south as yam suf.

As mentioned above, Jerome (ca. late 4th Century A.D.) recognized the geographical problem this posed. Jerome speculated that suf, while meaning red might also mean reed (Cf. Davies 1979, 70). Thus yam suf was a lake where reeds grew as well as the Red Sea. It is well known that Jerome worked closely with Jewish Rabbis at his time and studied earlier Jewish writings, for he believed that in order to truly interpret the Hebrew Scriptures, one should work with the Hebrew text (Hailperin 1963, 5-7). In short, Jerome thought that yam suf could apply both to the Red Sea and the Reed Sea through which the Israelites passed.

In recent years there has been some speculation that the Gulf of Aqaba had been connected to the chain of lakes north of Suez. Simons (1959, 248) cautiously makes this suggestion, recognizing that concrete evidence was lacking. N. Glueck (1970, 107) has reported that the Gulf of Aqaba may have retreated from its ancient shoreline by 500 meters since Solomon’s time (970-931 B.C.). Thus the water level in the 2nd Millennium was somewhat higher than at the present time, thus making the connection between the Gulf and the Bitter Lakes closer than today.

A remark by Herodotus concerning the Gulf of Suez indicates that the ebb and flow of the tide was considerable (Herodotus II, 9.11). In recent history it has been reported that when the tide comes in, the land between the Gulf and the southern most of the Bitter Lakes becomes saturated and water oozes to the surface (Cassuto 1967, 167). Napoleon, when campaigning in this area, experienced the sudden appearance of this water which had not been there when he had passed by earlier. Others have been forced to use boats to traverse this area during high tide (Cassuto 1967, 167).

Whether or not this phenomenon is behind the deliverance of the Hebrews from the Egyptian army is impossible to say. But it illustrates how there may have been at least a periodic connection between the Gulf of Suez and the Bitter Lakes and why the biblical writers could have used yam suf for both bodies of water.

A logical question presents itself if this scenario is correct.