BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE THESIS

BY MIRIAM GITELMAN

PART 1: HISTORY

PART 2: RESEARCH

PART 3: APPLICATION

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART 1: HISTORY

As maritime-industry oriented communities in New England developed over the centuries, lighthouses have become an integral part of the regional identity and heritage due to the countless lives impacted by their existence. In addition to preventing a large number of shipwrecks along the shipping and fishing routes that pass the New England coast, lighthouses and their keepers are responsible for as many rescues in the centuries preceding radar and modern technologies. As a result, lighthouses have contributed significantly to the economic security of New Englanders and thus to the establishment of the United States. To this day, small-

TIMELINE OF KEY LIGHTHOUSE DEVELOPMENTS

TIMELINE of KEY LIGHTHOUSE

Portland Head Light and Ram Ledge Light are the first lighthoues to be automated 1958 | PORTLAND, ME

Boston Light is the last to be automated APRIL 16, 1998 | BOSTON, MA the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act allows for the U.S Coast Guard to o load decommissioned lighthouses 2000

many lighthouses along the Maine coast are severely damagaed due to a major storm that coincides with a king tide JANUARY 10 & 13, 2024 | MAINE

time fishermen from coastal towns prefer watching for these familiar lights for navigation rather than looking at their radar. Starting in 2000, the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act has allowed for the U.S. Coast Guard to off-load decommissioned lighthouses to local governments and non-profits, meanwhile auctioning off unwanted lighthouses to the general public.

EVENTS

“To

almost every man and woman there is something about a lighted beacon that suggests hope and trust and appeals to the better instincts of all mankind. Standing off by itself in the ocean, a lighthouse symbolizes the external vigilance of its keeper, who must be alert and watchful at all times— in sunshine or darkness, in fog or in stormy weather.”

Famous Lighthouses of New England, Edward Rowe Snow

PART 2: RESEARCH

Since the illumination of the first lighthouse in North America—the Boston Light on Little Brewster Island in 1716—lighthouses have become widespread sentinels along the New England coastline and beyond. Now, years after the invention of radar, lighthouses are mainly a symbol of New England regional identity. The photos on the right were taken throughout the New England Coast, from Northern Maine to Nantucket Island.

METHODOLOGY

The research methodology included a thorough site visit road trip along the New England coast, documentation, and several interviews with lighthouse keepers, historians, and filmmakers.

In conversation with Rob Apse, film director of the 2020 film The Last Lightkeepers, we discussed that New England communities are in a transitional moment where lighthouses are being lost to the public because they are not being supported by their communities. As a result of the Lighthouse Preservation Act, lighthouses that are not maintained properly or don’t receive visitors due to a lack of infrastructure

This trip was made over three days along the New England Coast.

ROB APSE

Film Director, The Last Lightkeepers (2020)

“My generation isn’t going to be as focused on history… I think [the lighthouses are] all going to end up in private ownership… it’s also a negative in the sense that it won’t be open to the public…”

“we’re in the heat of it right now and I think were going to look back maybe 40, 50, 60 years from now and say ‘wait a minute, what just happened?’”

FORD REICHE

Entrepreneur, Owner of Halfway Rock Lighthouse

“… the US Coast Guard is not a good owner [of lighthouses]…”

“… there are few structures that are as awed as lighthouses…”

“[In lighthouse preservation, there is] no expertise on [environmental] mitigation efforts, we’re making it up as we go along…”

JEREMY D’ENTREMONT

Preeminent Lighthouse

Historian

“In the 23 years I’ve been involved … the worst four floods I’ve seen have been in the last three years, and two of them were in the past year.”

“We knew this kind of thing was already happening, but that last storm was really a wake-up call. This is not something to think about for the future, this is something that’s happening now. Damage from rising seas and more frequent severe storms… it’s obviously a major deal for lighthouses because lighthouses are right on the front line of this kind of thing.”

end up shuttered to the public for safety reasons. Many lighthouses, especially those further from shore are suffering from the detrimental effects of climate change because they do not have sufficient funds to be maintained and repaired. In fact, Jeremy D’Entremont, the top expert on New England lighthouses, says climate change’s acceleration can be marked by the destruction it causes to lighthouses. Ford Reiche, the owner of Halfway Rock Lighthouse in Maine, spoke about the lack of expertise on how to properly mitigate climate change impacts on lighthouses across the US. He even mentioned that the US Coast Guard is not a good owner of lighthouses and often leave them to the elements uncared for.

DOCUMENTATION

Seeing nearly 30 lighthouses in a span of a few days, I was able to observe a wide range of lighthouse construction types, and while many of these lighthouses seemed at first glance to be in good shape, most of them were in various states of disrepair, whether it was the towers themselves or their access structures. These photos were taken on 35mm Eastman Double-X black and white film.

Documentation throughout the road trip revealed that there are a wide distribution of ownership of lighthouses in the region. The map above shows the distribution of ownership of lighthouses along the coast since the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act. A majority of lighthouses are still owned by the Coast Guard but more and more are coming into private ownership.

Additionally, climate impact was also evident throughout the road trip. Two destructive storms occurred as recently as January 2024 in Maine, resulting in widespread damage along the coast. A majority of damage was taken by support buildings to lighthouse towers—boathouses, footbridges, and keeper’s houses—which are integral to facilitating access to the lighthouses they are situated next to.

This destruction is not just caused by occasional storms. Above is a flood prediction map showing the percentage rise of water levels in the next 30 years. The two key zones where this is of biggest concern (over 20% rise) is in the two darkest areas where many lighthouses are.

CLASSIFICATION

Different types of lighthouse architecture require a variety of approaches. In the diagram above are some of the most common types of lighthouses. The design strategy (at right) proposes variably adjusted methods for lighthouse rehabilitation that implement double or triple functionality in the space, addressing a mitigating climate response as well as facilitating public access to the site. Single functionality proposals are not covered within the scope of this project. In addition to lighthouse construction typologies, there are three important variables for proposing design solutions: accessibility, context, and threats.

LIGHTHOUSE TYPOLOGIES

There are 10 major lighthouse typologies observed along the New England coast.

On the following spread is a chart that implements those variables and reveals that there are 240 possible combinations of variables and thus 240 solutions, though not all 240 solutions are unique. The larger dots are projects are explored in more detail through the Postcard Sketches, and the small black dots represent additional lighthouses documented during the road trip. The Postcards are a few of the worked examples that begin to explore the potential designs for each type of site depending on the specific needs of the lighthouse and the parameters of their contexts.

GUIDEBOOK

This thesis takes the case study of New England lighthouses to propose methods of preservation and adaptive reuse of history in our society so future generations can continue to learn from such important cultural icons. Current owner agencies lack the creativity and resources for comprehensive analysis necessary, thus the thesis will propose a resource these agencies can implement on a case-by-case basis.

I propose the creation of a guidebook that could be used by lighthouse-owning individuals and agencies as a framework for instigating their own lighthouse rehabilitation programs. This guidebook would have double functionality examples and methodology on how to approach each lighthouse rehabilitation project with consideration for the construction type, accessibility, context, and threat. On the following spread are six worked examples of how each lighthouse site can be approached.

WHALEBACK

LIGHT, ME

A public fishing area that guides boats past the lighthouse upriver and monitors the local ecosystem.

GREAT POINT

LIGHT, MA

A formal hiking path that prevents coastal land erosion and preserves local residents’ privacy.

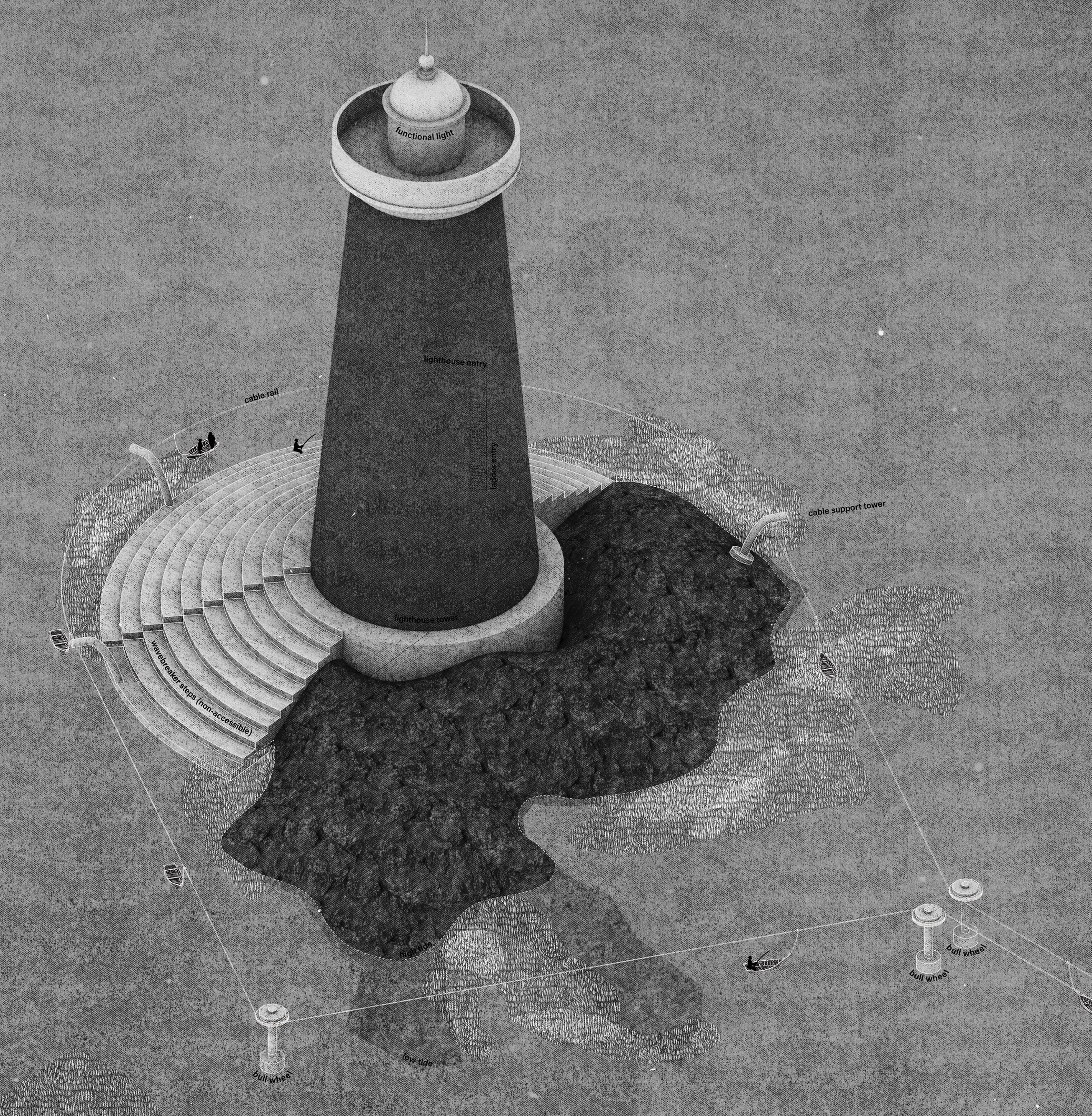

ROCKLAND BREAKWATER

LIGHT, ME

A wave breaker protection for a lighthouse while facilitating an accessible route for pedestrians.

PEMAQUID POINT

LIGHT, ME

A dynamic wavebreaker system with a research station.

SQUIRREL POINT

LIGHT, ME

A performance stage that serves as a protected fish habitat for endangered Atlantic Salmon and Sturgeon.

MARBLEHEAD

LIGHT, MA

A structural reinforcement for the lighthouse that can host public activities.

PART 3: APPLICATION

Whaleback Lighthouse has unique conditions and restraints because of it’s context. Not only is it remote (which already makes it difficult to access) but it is also home to a valued ecosystem anchored on eelgrass, which is the food that ensures the continued survival of the many fish that this area is known for. Perched at the mouth of the Piscataqua River in Portsmouth Harbor, the water currents can be as fast as 12 knots and the shipping lanes use the light of the lighthouse to guide them past the mouth of the river to the port further inland. This location is also a favorite spot for local fishermen due to the abundance of fish in the area.

ISOMETRICS

The three stations of the proposal are pictured here in isometric view.

WHALEBACK LIGHT SITE DOCUMENTATION

Visitors approach the lighthouse through a wooded road. And at the end of the road is a wooden boardwalk that was destroyed in the January storms and is blocked off completely. In between the viewpoint and the lighthouse is the Wood Island Life saving station, a building that served at the base for “surfmen” or rescuers that worked in tandem with the lighthouse keepers to rescue people from shipwrecks. Now the station is vacant but for a museum inside the building to which access is also limited. The current footbridge that is falling apart once served as a good viewpoint of the lighthouse by bringing visitors closer to it over the water. In the bottom right corner image is a closer look at the wooden structures filled with rock and concrete in the water in front of the station. These are the remnants of the World War II anti-submarine net that was strung between them and prevented enemy submarines from traveling inland during the war.

In order to test the concept of the thesis and experiment with the parameters of a difficult site, I selected one lighthouse to develop further. The challenge of Whaleback Light is the fact that the lighthouse, though close enough to see, wasn’t visible or accessible in any reliable manner, while also not obstructing the lighthouse in any way to take away from it’s poignancy. A method of over water transportation that emerged in Europe is the cable ferry, a back and forth barge that moves on cables between two points and does not require much energy to propel the boat. For this lighthouse, and other lighthouses that are similarly close to shore but still not readily accessible by land, I propose a cable ferry system that first moves between the mainland and the life saving station, and then from the lightsaving station to the lighthouse.

MAINLAND: The journey starts at the boathouse on the mainland where the approach to the space echoes the forms of the wooden structures in the water. On stormier days when the weather makes the waters too unsafe to use the boats, visitors can still experience a directed view of the lighthouse by engaging with the stepped seating on the roof of the building that slowly merges into the water. Inside, there is a floating dock that adjusts with the tide, a mechanism for propelling the boats, and a system for boat storage while not in use.

ISLAND: At Wood Island, visitors can choose to disembark to explore the island and museum on the walking paths. The dock has a concrete anchor that serves as seating and the dock is attached to it so it can float with the tides.

IN BETWEEN: After boarding a boat, fishermen can choose to fish from the vessel or stop off at the structures that once supported an anti-submarine net, but are now repurposed as small off-shore docks for fishing. For environmental restorers, the cable system allows them to have a reliable method of reseeding eelgrass by throwing it off of the side of a ferry boat in

minimal force required to propel ferry

SITE PLAN

On stormier days when the weather makes the waters too unsafe to use the boats, visitors can still experience a directed view of the lighthouse

motion as the water current will propel the seedlings down the length of the river, which will also help replenish the fishing population as the fishermen deplete their populations.

NO LAND: Visitors can choose to proceed around the lighthouse and the route will take them around the lighthouse to view it from all sides. Because this lighthouse is most at risk of damage from storms and strong waves, a series of wavebreaker steps that are not accessible to the public will be built behind the lighthouse. These steps can also be used by maintenance workers who do need to have access to the lighthouse.

With this project, I hope to bring the conversation of lighthouses back to the table and show lighthouses carers that lighthouses can become important aspects of society again through architectural analysis and out of the box proposals that will bring visitors back in larger numbers.

ADVISORS

Caitlin Blanchfield

Timur Dogan

ERIN PELLEGRINO

For her passionate knowledge of lighthouses.

JEREMY D’ENTREMONT

For sharing his expertise with such care.

SPECIAL THANKS TO

David Ni, for film development and road trip support

Ford Reiche, for repairing what others cannot

Rob Apse, for moving me to act And to my mom, for nurturing this project since I was born.