W EDICAL W MAN

VOLUME 39: ISSUE 1

SPRING/SUMMER 2020

The Justice Issue www.medicalwomensfederation.org.uk

Editor’s Letter Justice: in health and on planet

T

he overarching theme of this issue is justice. Justice in the face of a climate crisis, and in the delivery of universal access to healthcare - regardless of race or geography. In this issue, we have articles covering climate change and its impact on health, racial disparities in women’s health, as well as Palestinian women’s access to medical care. This issue also houses an array of educational articles providing tips for training. In our Career Planning article, we hear from a consultant ophthalmologist about a career in managing diseases affecting the eye. Moving on to the Skills Toolkit section of this issue, we have some timely tips to help you along the way in your transition from medical student to doctor. Along the way, we also touch on a personal perspective covering return to work after a period of ill health, with practical advice on how to build back a return to clinical practice. A Scottish flavour permeates this issue from start to finish. I had the pleasure of being a panelist at the annual Edinburgh Medical School debate, ‘Is medicine still a patriarchy?’, at the end of last year - a reflection on the event can be found in our News and Events section. This issue wraps-up with another reflective piece on a panel session discussing the history of women in medicine in the context of a 1960’s medical novel written by a retired Scottish GP. I hope this issue provides you with a selection of intriguing articles with perspectives from around the country and the world. Do share Medical Woman with your family, friends, and colleagues. I look forward to hearing from you - my contact details are below - and to seeing you at our next meeting.

Fizzah Ali @DrFizzah Fizzahali.editoratmwf@gmail.com

Contents Medical Woman, membership magazine of the Medical Women’s Federation Editor-in-Chief: Dr Fizzah Ali fizzahali.editoratmwf@gmail.com Editorial Assistants: Miss Katie Aldridge Miss Danielle Nwadinobi Design & Production: Toni Barrington The Magazine Production Company www.magazineproduction.com

News and Events 2

Career Planning: Ophthalmology

4

Skills Toolkit: Student to Doctor 6

Climate and health: topical dilemma

4

8

Cover illustration: Pexels Articles published in Medical Woman reflect the opinions of the authors and not necessarily those represented by the Medical Women’s Federation. Medical Women’s Federation Tavistock House North, Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9HX Tel: 020 7387 7765 E-mail: admin@medicalwomensfederation.org.uk www.medicalwomensfederation.org.uk @medicalwomenuk www.facebook.com/MedWomen Registered charity: 261820 Patron: HRH The Duchess of Gloucester GCVO

The global health challenge of a lifetime

10

Returning to work

14

MWF Autumn Conference 2019 16

10 Spotlight on women’s health: racial disparities

18

Obituary: Dr Thelma M Phelps

21

President: Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones OBE President-Elect: Professor Neena Modi

6

Global health: Palestine a right to health 22

18

Vice-President: Professor Chloe Orkin Honorary Secretary: Dr Anthea Mowat Honorary Treasurer: Dr Heidi Mounsey

Medical Woman: © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Publisher. A reprint service is available. Great care is taken to ensure accuracy in the preparation of this publication, but Medical Woman cannot be held responsible for its content. The views expressed are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the Publisher.

Unwind: Creativity and healthcare

26

Book review 28

26

MWF NEWS & EVENTS

MWF Local Group Report Molly Parkinson MWF Student Representative for the University of Exeter

DATES FOR YOUR DIARY June 2020 MWF Junior Doctor Prize Opens October 2020 Three months free MWF membership promotion for new members November 5th 2020 MWF Council Meeting (London) November 6th 2020 MWF Autumn Conference (London) December 2020 Katherine Branson Student Essay Prize opens

On the 24th of February, we hosted our second “Women in Medicine� event on behalf of MWF. We invited speakers from General Surgery, Anaesthetics, Psychiatry, Obstetrics and Gynaecology to talk to students about their careers. Speakers were asked to consider the decisions that led to their career pathway, advantages and disadvantages of their chosen specialty and work-life balance. They also discussed any challenges they have faced throughout their career that they feel have been specifically related to being female. We had a really pleasing turnout of over 40 students and all feedback has been really positive. Our speakers discussed some note-worthy topics, such as, how gender equality in the medical workplace has developed between when they were training and now, achieving balance between work and family life, and the advantages and disadvantages of part time work. It was really interesting to hear the differing opinions of clinicians regarding whether they feel being female has impacted their career opportunities. Whilst there were some difficulties discussed, such as, feeling behind in relation to colleagues due to taking time out of training to have and raise a family, the overall consensus appeared to be positive, and that they have only ever been treated on their merits as women and never disadvantaged overtly because of their sex. Clinicians were also very positive about the future of equal opportunities in medical careers. Students were really engaged and prompted to ask some thought-provoking questions, and overall, this was a genuinely inspiring evening, providing students with food for thought regarding their future careers, and hopefully making a positive mark for the future of gender equality in medicine. 2 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

MWF NEWS AND EVENTS

Is Medicine Still a Patriarchy?

The Edinburgh Medical Debate 2019 Aya Riad

Each year the Edinburgh Medical Students’ Council hosts a debate on a topical subject, and on the 150th anniversary of the matriculation of the Edinburgh Seven, we thought it only fitting to use this platform to see how far we have come to reaching gender equality in medicine. These days, the majority of medical students are women and certainly when I was applying, it never crossed my mind my gender would be a disadvantage. But once you’re through the door, the patriarchy reveals itself, particularly when considering disparities between specialties, in leadership, or academia. We invited our esteemed panel to the stage of McEwan Hall, Edinburgh’s graduation hall, in front of an audience of 800 people and – much to my delight – opened a pandora’s box of factors that prevent us from reaching Jex-Blake’s dream of “a fair field and no favour”. In addition to gender, we discussed how race and socioeconomic disparities also create barriers to equality, and the importance of visible women in senior positions for as Professor Lorna Marson puts it, “you cannot be what you cannot see”. Perhaps most significantly, this debate extended beyond the night itself to a media campaign encouraging students to shine a light on ‘casual sexism’ in medical school and the entrenched stereotypes which might affect your career choice or teaching experience. To many, the answer to our motion might have been a resounding yes from the outset and not one that is up for debate. Our decision to move away from the traditional debate format to a panel, we hope exemplified the significance not of the conclusions but the conversation. For many reasons, we often shy away from speaking about the topics which impact us the most and yet, if there is one thing that the incredible reception to this event has demonstrated, it is that people are hungry for frank and candid discussion. I hope that in facilitating this, we have validated the silenced experiences of many, exhibited that it is possible to overcome these barriers, or at the very least, revealed what we are up against. Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 3

CAREER PLANNING: EYE SPY

Eye Spy: a day in the life of an Ophthalmologist Rashmi Mathew qualified with a distinction from Guy’s Kings and St Thomas’ school of Medicine in 2003. She completed her 2 year fellowship at Moorfields Eye Hospital in 2013 and joined the Glaucoma Consultant Faculty in 2013. She is also the Deputy Director for Undergraduate Education and Resident Leadership Training Lead at Moorfields Eye Hospital. She is an Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Medical Education, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself? I am a Consultant Ophthalmologist, with a subspecialty interest in glaucoma. I completed my ophthalmic training in 2011 and then did a double fellowship in glaucoma at Moorfields Eye Hospital. I have two young children, whom I had after becoming a Consultant. I enjoy running, cycling, as well as sketching.

Why did you decide to do ophthalmology? It was just at a point when I thought I might quit my degree in medicine, that I stumbled across Ophthalmology during my third year clinical placement. It instantly appealed to me, the finesse work, the technical challenge of doing microsurgery and every ophthalmologist I met seemed happy. I still remember watching cataract surgery on the TV screen, as I was observing in theatres and just couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I had never seen anything like it. It was at that moment – without even a shadow of a doubt, I knew I wanted to be an ophthalmologist. It was only later that I would discover that it was also intellectually challenging, rewarding and as a bonus – a very clean specialty (no vomit, pee or poo, unless you were very unlucky). It is also remarkably varied and there are nine subspecialties within ophthalmology, so there is generally something to suit everyone.

What do you enjoy most about being an Ophthalmologist? Ophthalmology is a very rewarding specialty and particularly as glaucoma is a long-term condition, I build long-standing relationships with my patients and I am able to provide continuity of care. This is something very important to me and my patients. Many of my patients still remember when my children were born and always ask after them. Things are always changing in ophthalmology, surgical procedures, new technology, novel ways of working and so I enjoy the fact that I am always learning. For example, just before Christmas I had some wet-lab training to learn to how to insert a new surgical device into Schlemm’s canal in the drainage angle. One of the great things about my role, is that I have been able to combine it with my love of education. I had never thought of combining education with my clinical role as a consultant, but I was fortunate that those around me recognised this in me and I am able to do this as a Consultant, with formal education sessions in my timetable. My education role has allowed me to work closely with universities and meet lots of people outside of ophthalmology. I am enjoying it so much, I am even doing a Masters in Medical Education at present.

What are the challenges in your chosen career path? Describe a typical day as an Ophthalmologist? I am a glaucoma and cataract Surgeon and as Ophthalmologists we are outpatient based. A typical day might be split between clinic and the operating theatre. On the morning of my clinic, my team and I go through all the clinic notes and request necessary tests for patients, to help with clinic flow. We then do a brief with the entire team, so everyone understands the plan of action and we try and mitigate problems early. The clinic is fast-paced, and I shift between supervising my trainees and seeing patients. We do a lot of procedures for our post-op patients in the outpatient setting – these can be injections in and around the eye, removing stitches and even trying to free up scar tissue at the surgical site. In the afternoon for my operating list, I do a pre-operative ward round prior to operating. We again do a team brief with the entire team, prior to commencing the list. I always have trainees with me, and it is one of the joys of my job – surgical training. We video all the cases and I spend time debriefing with my trainees after the list.

Ophthalmology is notorious for being a competitive specialty and I think it helps if you know early on that you would like to do it, in order to be able to build your CV in time for the Specialty Training national recruitment process. As a surgical specialty, it is very female friendly, and we have a high proportion of women in ophthalmology – which is great. In terms of the actual specialty, you are dealing with the most precious of all senses and this is not something any of us take lightly. Patients can naturally be quite anxious, particularly if they have to undergo surgery. And, when something goes wrong, the result can be catastrophic.

What advice would you give medical students and trainees deciding on their future specialty? My advice is to of course do a specialty that you enjoy, but also have another string to your bow. I always advise trainees to think about combing your clinical specialty with education, research, management for example, to keep things fresh, varied and challenging. Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 5

SKILLS TOOLKIT: STUDENT TO DOCTOR

Medical Student to Doctor: A preparation guide for soon-to-be doctors Georgina Elliot is a junior doctor working in East London. She completed a Biomedical Science (BSc) degree at King’s College London prior to medical training at Barts and The London, graduating in 2017. She completed her Foundation Training in London, finishing in 2019. She is currently applying for a specialty training programme in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Georgina also enjoys teaching as well as clinical work.

Introduction

Responsibility

As you come to the end of medical school, you may be worrying about the challenge that lies ahead in August. Although the steep learning curve that faces you is generally considered to be one of the hardest to traverse, all around you there will be other doctors who are going through changes in their careers too. Foundation Year 1 (FY1) doctors will become senior house officers, senior house officers will become registrars, registrars will become consultants. Although having knowledge of this does little to make your transition easier, it is worth bearing in mind that you will almost certainly be working with people who are experiencing many of the same challenges you are; heightened responsibility, a feeling of under-confidence, and a desire to find your feet and excel in a new role. They will also almost certainly want to help make your transition from student to doctor as easy as possible. This article is intended to make you aware of the common difficulties that FY1 doctors experience, but also to give you advice on things that you can do now to help you ease the transition.

As a medical student, you have responsibility for only yourself; your learning, your exam results, your logbook. As an FY1 doctor, you will be making decisions, giving advice, signing your name to prescriptions and management plans. Although there is always a senior around to check plans with, you will often be the only doctor to see a patient and make an assessment. Coming to terms with the responsibility of your assessments and decisions making a real impact on the lives of others can be a challenge. A way to tackle this ahead of time, as with all big challenges, is to prepare. It can be easy to get caught up in revision for OSCEs and written exams, but you should keep in mind that what you’re really preparing for is August. The majority of actual decision making and responsibility lies in on-calls, and that is what new doctors generally find hardest to manage. Therefore, you can prepare by shadowing an FY1 on as many on-calls as you can prior to starting work. Ask to carry the bleep and respond to calls as you would if you were on your own. See patients with

6 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

SKILLS TOOLKIT: STUDENT TO DOCTOR

supervision, do the cannulas, blood cultures and arterial blood gases, look up the observations and bloods and come up with a management plan. This level of independent thinking and operating is often what people find most difficult, but if you can do it well with supervision that will give you confidence and experience going into your first shift. Another way to prepare is by practicing your practical skills as much as possible. If you have confidence in your practical skills, then that first call to insert a catheter or a cannula will be significantly smoother. And remember, if in doubt, call for senior support.

Rotas Moving from a life of self-directed learning and self-motivation to having your life governed by a rota will be a tough aspect of starting work. The majority of rotas include normal working days, long days, weekends and nights. These would be tough for anyone to adapt to and sleeping patterns can be erratic. Social lives can become difficult to negotiate. After five years of generally free weekends, many find it very hard to suddenly be missing out on events and occasions due to rota commitments. A way to tackle rota anxiety is to be well-informed. I would recommend reading the junior doctors Code of Practice1, and your contract2 prior to starting work, so you are aware of what to expect. As per the Code of Practice, you are entitled to your full duty rota at least six weeks prior to your start date. Don’t be afraid to email your rota-coordinator if you haven’t got it in good time. If you are aware of specific time that you need off, it may be possible for them to give you a specific slot that accommodates that, so email them with that information as soon as possible (even prior to receiving your rota). Nothing hurts morale more than missing out on something important because of work, and you will thank yourself for ensuring you have plenty of rest time as well. If you need to swap on-calls, arrange them nice and early, don’t be shy in asking. Swaps are almost always possible if you are reasonably flexible with the days you can offer in return. However, be wary with overloading yourself with too many on-calls through swaps. If you end up working four weekends in a row you are likely to be exhausted and miserable. Be realistic and be kind to yourself! Remember that as per your contract, you are entitled to annual leave for life-changing events (i.e. your own wedding) but you need to inform the rota coordinator at least six weeks in advance to let them know.

What if I don’t cope? Some doctors require more support than others through the foundation years, and that’s nothing to be ashamed of. It’s a difficult time for everyone, and there is plenty of support out there if you do begin to struggle. Being resilient isn’t the answer. Talking about it and seeking help if you need it is the best way to handle difficult times. If you find clinical duties hard to manage, your clinical and educational supervisors are there to help you keep on track, so they are your first port of call. You can also turn to your ward consultant, registrars and senior house officers for help if you feel more comfortable with them. They will often know exactly how it feels to go through foundation training and will have helpful advice. It is also important to remember your family and friends and make time for them. Finally, and most importantly, if you feel your mental health is suffering, make sure you see your GP, and discuss it with your clinical and educational supervisor as soon as you can if you need time away from work. Doctors are among the highest risk groups for developing a mental health condition, but we are some of the least likely to seek help. Looking after your own physical and mental wellbeing should be your top priority.

Great things Remember, most people really enjoy their FY1 year! There are some aspects that you can really look forward to. After years of lingering on the periphery of ward rounds and getting in the way, being an essential member of the team and being important to your patients is a feeling like no other. You are suddenly surrounded by new opportunities - audits, projects and representative roles to get involved in among others. Being able to teach medical students of your own is also exciting. They will often feel much more comfortable with you than the senior house officer or the registrar, and you will likely deliver a large part of their bedside teaching. Having a regular salary after years of debt is also not to be underestimated! It’s worth remembering that this is what you have been working towards for five (or more) years, and that all exams, projects, dissertations have led to this point. Nearly three years after starting FY1, I still remind myself of the privileged position that I hold and how lucky I am to be one of the select few to call myself ‘doctor’, and you should too. Before you know it, you will be thinking about postgraduate exams, specialty applications and the next step up the medical ladder, which will bring new challenges along with it. So good luck, enjoy it and look out for each other. Welcome to the world of practicing medicine!

Moving After five plus years at medical school in one area, moving away can feel incredibly hard. You may be leaving family members, partners and friends behind. A good way of making this easier is to arrange accommodation as soon as you can. Starting work while sleeping on sofas and trying to find somewhere to live is going to make everything more stressful. You should also arrange as much time as possible with your family and friends when you get your rota. Whether that’s planning a trip home, ensuring you can make a birthday party or keeping an evening free for a friend you want to catch up with, your social support will be invaluable to you over the first few months of work. If you are generally a very sociable person, get involved in the Doctors’ Mess. The Mess Committee is usually run by Foundation Year 1 and 2 doctors, and it’s a great way to meet and socialise with other doctors in your hospital/trust.

Top 5 Tips for Making the Move: Shadow FY1 doctors as much as you can prior to starting work Get your rota and arrange your annual leave as soon as you can £ Find somewhere to live and settle in as soon as possible, don’t leave it until the last minute £ Look after your own physical and mental health £ Try and enjoy it! £ £

References 1

ode of Practice: Provision of Information for Postgraduate Medical Training. C NHS Employers, BMA, Health Education England 30/10/2017. Accessed on 12/1/20: http://bit.ly/3d99BiF

2

T erms and Conditions of Service for NHS Doctors and Dentists in Training (England) 2016: Version 8. NHS Employers December 2019. Accessed on 12/1/20: http://bit.ly/33sUlJ3

Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 7

FEATURE: CLIMATE AND HEALTH

Climate emergency, Health emergency From environmental activists to weather related natural disasters; discussions on climate change have dominated headlines over the past months. Sitting in an office above Trafalgar Square I have watched Extinction Rebellion march in protest, and amongst them noted staff, including doctors, from the National Health Service. Climate change has generated an ecological crisis with a global impact, generating devastating impacts widely, whether on marine life, or rainforests. Specific to healthcare, climate change has a direct impact on health, whether through extreme heat, flooding, and the potential spread of infectious diseases to the United Kingdom. Climate change also has an indirect impact through affecting the social and environmental determinants of health, and the availability of basic human requirements such as clean air and water, food and shelter.

8 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

FEATURE: CLIMATE AND HEALTH

Title: Title Farah Jameel is an international medical graduate and GP in London. She is a GP appraiser and a member of the GPC England executive team, through which she has been involved in contract negotiation and representing the views of GP’s on a variety of critical issues. Farah is also chair of Camden Local Medical Committee. She is absolutely petrified of horror movies.

I am a rare breed of clinical academic physiotherapist and took a circuitous route to what I do today. I was born in the UK of mixed heritage. My parents are nurses by profession, my father from Mauritius and my mother from Ireland. I spent a lot of my childhood around hospitals, so that environment plus a love of sport, pointed me towards physiotherapy. My pre-registration training was at the University of East London, National Health Service produces over 5%asofa carbon one The of the first universities to offer Physiotherapy four-year emissions, than1990s. the global average for healthcare. degree course inhigher the early After qualifying in 1995, I worked a of carbon reduction place, despite an I in a With number London teachingstrategy hospitals.inEarly on in my career, increase in clinical in activity the past a reduction in expected to specialise sportsover injuries, but I years, grew to love neurology carbon footprint has been neuroscience noted. Currently, the Government through working at excellent centres. My fascination towards net zero carbonwith by 2050. withstrives neurophysiology coincided a really important time in neuro-rehabilitation with evidence emerging on how therapists Climate change a wide of challenges; requiring could influence motorposes recovery and array neuro-plastic processes. the to waytheweNational consumeHospital and operate within theand In changes 2001 I to went for Neurology National Health Service. In this our feature on climate Neurosurgery, Queen Square, and issue, I’ve never quite left! I was a change helpsphysiotherapist inform your interest in environment and health, full time clinical and studied for my Masters at the directs to useful sameand time. I started to resources. encounter people with rare neurological conditions, and quickly realised that the evidence for rehabilitation and physical management was almost non-existent. At the same time, I began to collaborate with scientists at University College London (UCL) working in the human movement laboratory. I developed an interest in 3D kinetic and kinematic analysis of balance and gait, using these techniques for my MSc dissertation, assessing the effects of contoured insoles in people with multiple sclerosis. One of my colleagues in the lab was awarded a Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinician Scientist fellowship that included funding for a research physiotherapist plus PhD fees. I applied for the position and started my PhD in late 2004. My thesis explored gait impairments and potential interventions for people with inherited peripheral neuropathy, or Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT). Through the recruitment process, I developed a good relationship with the neuromuscular specialists and provided a physiotherapy service to one of the multidisciplinary clinics. I completed my thesis in 2007 and decided that returning to a clinical job would probably prove challenging for continued research. I took up a senior lecturer position at the joint faculty at St George’s University of London and Kingston University. My main work was undergraduate teaching, but I was also encouraged to apply for research grants. I kept my links with the Queen Square neuromuscular team and we were awarded a charity grant to undertake an exercise trial in CMT. Later I was awarded one of the newly launched National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Lectureships, a fellowship for Allied Health Professionals, nurses

and midwives. This allowed me to continue to develop clinically at the new MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases, set up a small motion analysis lab at the centre and still teach at St. George’s. Closer working with the centre led to an NIHR Research for Patient Benefit grant and other charity grants. I was becoming a principle investigator. I am now an Associate Professor and Director of Research at the School of Allied Health, Midwifery and Social Care at St. George’s/ Kingston University. My research is still primarily undertaken at Queen Square, and after my fellowship, I was able to negotiate an ongoing clinical day there. This diversity in my role now means I am a true clinical academic physiotherapist, a much rarer model than in other professions, such as medicine. Research was a draw for me early on as I was continually questioning the theoretical basis for physiotherapy interventions. The catalyst was working at Queen Square, where clinicians and academics work alongside each other, or are in split posts. The scientists were very interested in the clinical questions I had, and that was how the idea for my master’s research became a reality. The career pathway for Allied Health Professionals in the early noughties did not really include research, so I had to grab opportunities along the way. I was fuelled by intellectual curiosity and enthusiasm, so was determined to find ways get projects off the ground. The NIHR clinical academic training route is now more available and is a fantastic opportunity to develop future research leaders. The fellowship opened doors for me and I would encourage others to find out more about them and apply. Good mentorship is vital plus collaboration with colleagues with differing areas of expertise. Mentors who have worked in research can help you to plan your careers and prioritise opportunities. I have learned not to be precious about my ideas, as others can develop them with you. There is a lot of rejection in research, so developing a thick skin, and using feedback to improve papers and grants is an absolute must. The rejections make the successes so much sweeter!

Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 9

FEATURE: CLIMATE AND HEALTH

Climate change: the global health challenge of a lifetime Isobel Braithwaite graduated from Cambridge and UCL. She worked as an academic foundation doctor before starting public health training. She currently works in Public Health England’s Extreme Events team and as an Academic Clinical Fellow at University College London. She has been involved in projects on climate change and health since 2010. She has interests in healthcare sustainability, air pollution and climate adaptation for health.

10 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

FEATURE: CLIMATE AND HEALTH

Climate change is often thought of as an issue that affects polar bears or people far off in the future, but this past year has shown us that it is already here and that it is, perhaps first and foremost, a health emergency. It is bushfires in Australia and California, stopping people from being able to breathe and forcing them to jump into the sea to stay safe. It is record-breaking floods, taking lives and imposing a heavy toll on the mental health of the families and communities affected for the years to come.1 It is unprecedented heatwaves killing thousands of older people and stretching our health systems.2 Other impacts include increased infectious disease risks, food insecurity and indirect consequences such as exacerbation of poverty and increased risks of migration and civil unrest are also documented.3 It is for all of these reasons that the World Health Organisation has called it ‘the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century.’4 What’s more, these impacts disproportionately harm the health of those already affected by health inequities - unfair and avoidable differences in health outcomes because of their gender, race, disabilities, socioeconomic status and the other axes along which power and resources are unevenly distributed. Poor and marginalised groups are at greater risk from the indirect consequences of climate change, such as food price spikes due to crop failures, and often have fewer options when it comes to adapting. Yet they have contributed the least to the problem through their own emissions. Unfortunately, the National Health Services (NHS) also contributes to this health crisis, being

responsible for around 4% of the UK’s overall climate footprint - over half of which stems from procurement (including drugs, medical and surgical equipment). This means that decisions made in everyday clinical practice have a key role to play in reducing healthcare’s climate impact. Across the health system, a transition towards sustainable clinical practice is likely to require a major shift towards prevention, streamlining care pathways to make them more efficient, minimising waste in all its forms, and increased use of effective but low-resource management options such as social and nature-based prescribing (where appropriate). This also includes switching to more environmentally sustainable drugs and anaesthetics. The flipside of the threats climate change poses to our health is that many of the actions needed for climate change mitigation are very good news for public health in the here and now.5 For example, switching to clean energy, stepping away from cars towards bikes, walking and using public transport can clean up our air. This is important as air pollution kills around 30,000 people each year in the UK,6 these measures also increase levels of physical activity. Better insulated homes will reduce energy losses whilst addressing the thousands of deaths due to cold homes that we see every year, whilst a reduction in consumption of red and processed meat in favour of more plant-based options could prevent thousands of cases of cardiovascular disease, stroke and cancer each year. It is for these reasons that scientists have termed it ‘our greatest global health opportunity.’ Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 11

FEATURE: CLIMATE AND HEALTH

12 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

FEATURE: CLIMATE AND HEALTH

In the context of these global challenges, which can sometimes feel overwhelming, what can we as health professionals do? • Educate ourselves further about the problems and their solutions – there are many resources, including free online courses, available to help (see below). • Connect up with others who share your knowledge and concern that the climate crisis is a health crisis. Such communities of practice are great ways to share ideas and learning, to inspire, motivate and support one another. Networks such as those of the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare, Health Care Without Harm and Health Declares Climate Emergency are excellent places to start. • Take action within our workplaces to reduce healthcare’s environmental impacts. Some steps you could take in your own workplace include connecting up with your estates team’s sustainability lead (if you work in a hospital Trust), setting up a sustainability network, and calling on your organisation to declare a climate emergency (Health Declares Climate Emergency can help you in this). Additionally, consider participating in the national ‘For a Greener NHS’ campaign (link below). • Take action in calling for the transformative public policies we need to see. Doctors are trusted, have experience of communicating complex scientific concepts clearly and can understand how climate change relates to the health problems they see in their day-to-day practice. These are enormously valuable when it comes to making change and health feel more tangible and personal for our patients and communities, and in pushing for science-based policies to protect health. Why not consider getting involved with an advocacy organisation such as the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change, Doctors for XR or Health Declares Climate Emergency?

Further reading World Health Organisation - https://www.who.int/health-topics/climate-change Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change https://www.lancetcountdown.org/ Global Climate and Health Alliance - http://www.climateandhealthalliance.org/ Sustainable Development Unit - https://www.sduhealth.org.uk/ Centre for Sustainable Healthcare - https://sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/ Health Declares Climate Emergency - https://twitter.com/healthdeclares Doctors for Extinction Rebellion - https://www.doctorsforxr.com/ ‘For a Greener NHS’ campaign - https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/ Massively open online courses – • The Health Effects of Climate Change (Harvard) https://www.edx.org/course/the-health-effects-of-climate-change • Climate Change and Health: From Science to Action (Yale) https://www.coursera.org/specializations/climate-change-and-health References 1 Jermacane D, Waite TD, Beck CR, Bone A, Amlôt R, Reacher M, Kovats S, Armstrong B, Leonardi G, Rubin GJ, Oliver I. The English National Cohort Study of Flooding and Health: the change in the prevalence of psychological morbidity at year two. BMC public health. 2018 Dec 1;18(1):330. Arbuthnott KG, Hajat S. The health effects of hotter summers and heat waves in the population of the United Kingdom: a review of the evidence. Environmental health. 2017 Nov 1;16(1):119. 3 Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, Blackstock J, Byass P, Cai W, Chaytor S, Colbourn 2

T, Collins M, Cooper A, Cox PM. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. The Lancet. 2015 Nov 7;386(10006):1861-914. 4

World Health Organisation (2015) ‘WHO calls for urgent action to protect health from climate change’ https://www.who.int/globalchange/global-campaign/cop21/en/

5

Ganten D, Haines A, Souhami R. Health co-benefits of policies to tackle climate change. The Lancet. 2010 Nov 27;376(9755):1802-4.

6

COMEAP: Mortality effects of long-term exposure to particulate air pollution in the UK. A report by the Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants (COMEAP). http://bit.ly/2TYFXoJ

Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 13

14 Medical Woman | Autumn/Winter 2019

NEW BEGINNINGS: RETURNING TO WORK

Perspectives: returning to work after anxiety and depression Lucy Deacon is a Paediatrics trainee living in mid Wales with her springer spaniel Tinka. She is passionate about enabling teenagers to understand their physical and mental health care needs. When not busy on the wards she coaches and plays rugby, bakes lots of cakes and enjoys mindful walks in the fresh air whatever the weather!

My time out of training did not come in a planned fashion. Having worked hard to achieve my foundation competencies and having been accepted onto the Acute Care Common Stem (ACCS) training scheme, I went from being a doctor to a patient in a very short space of time. I was diagnosed with severe anxiety and depression which resulted in an acute admission to a psychiatric hospital towards the end of my Foundation Year 2 (FY2) year. After about a month it became apparent that I was going to be off work for some time, requiring intensive treatment. Returning to practice as a doctor was the last thing I was thinking about. My depression was severe - I thought I was a terrible person and felt like a fraud. I had turned my back on medicine. I had turned my back on life too. It was five years down the line in recovery and after much support that I started to think: “I miss medicine. I miss being a doctor… Maybe I could do it again…?” It was months of mulling this over before I voiced the thought and began to explore options. Because

“I went from being a doctor to a patient in a very short space of time. I was diagnosed with severe anxiety and depression which resulted in an acute admission to a psychiatric hospital.” I was so early on in my training when I took time out, I did not belong to a Royal College and because I had been out of training so long my old training deanery had no obligations to assist me. In theory and spoken out loud things sounded straight forward, but it was a terrifying prospect and I was uncertain whether returning to medicine would be possible as I contacted former supervisors. I started by meeting with my educational supervisor from my last post. I had done some reading and had established that my route to return would be to plan a Clinical Observership - the model designed for overseas doctors to gain an insight into working in the NHS. It was important for me to plan this in a familiar environment, because I would be returning to working life. My educational supervisor was encouraging and meeting him gave me the confidence to believe my return to work was possible, in turn pushing me over the next year to return to work. Having been unwell and previously relinquished my GMC registration I also had to reapply for registration; a lengthy but manageable task. My own care team was very supportive of my return to practice and provided all the necessary reports to enable this. It was, however, difficult writing about and accounting for my

“…I bring so much back to my practice now that I did not have before. I am older, wiser and have lived through difficult times.” time out of medicine. I worried because I was still having out-patient treatment - which required both energy and effort committed to it. I was also presented with the prospect of self-funding my return to work; and will be forever grateful to the Royal Medical Benevolent Fund (RMBF), who made this possible. Asking for help was a challenge for me, but I could not have afforded to go back to work without their support - course, registration, insurance, memberships and book fees all add up. My final hurdle was Occupational Health clearance which frustrated me the most; a waiting game for an appointment with a clinician who could provide my clearance. I returned to work two days a week as an observer in paediatrics, fitting in my treatment around this. There was no commitment at this point which made returning easier. My consultant mentor suggested I “suck it and see” and this approach worked really well; with no pressure I was able to go at my own pace and it was a smoother transition than I had expected. After a few months a Locum Appointment for Service (LAS) post came up at the hospital and I went to my first interview in 6 years. I was able to negotiate the required day off each week to attend out-patient treatment and flourished from being back at work. Over the course of the year I completed my own treatment and applied for paediatric training, gaining a run-through training post in the area of my choice. Working in a small hospital with 24-hour consultant supervision provided both learning opportunities and the one-to-one feedback that I needed to progress in both competence and confidence. Seven years is a long time out of training, yet I bring so much back to my practice now that I did not have before. I am older, wiser and have lived through difficult times. I have regained my clinical skills with supervision and support from senior colleagues and my confidence as a doctor and as an individual has grown with every patient contact. Having lived outside of the ‘doctor bubble’, I have developed a better understanding of the lives and pressures on my patients. At times, I find myself attempting to justify my time out of clinical training, worrying that in some ways it makes me less worthy as a doctor. Yet, I realise that when I attempt to deny the past seven years, I also deny what they have taught me. Those years in my training have made me the sort of doctor that I would want looking after me. Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 15

MWF Autumn Conference Report

Working Together: Overcoming Gender Bias in Medicine BMA House, 1st November 2019 Anna Ryan The joint meeting between MWF and the British Medical Association (BMA) focusing on tackling gender bias in medicine was a sell-out. A packed room greeted MWF President Henrietta BowdenJones and Chair of the BMA Council Dr Chaand Nagpaul as they presented the collaboration between the two organisations and outlined their priorities for the coming years. Revelations from the Romney report regarding sexism in the BMA were in the press at the time of the meeting and Dr Nagpaul pledged to learn from MWF and take ‘any action necessary’ to end misogyny and sexism within the organisation. BMA Representative Body Chair Dr Helena McKeown seconded this commitment as she led a stimulating panel discussion focusing on the issues facing women doctors today. Other highlights were an inspirational keynote speech by Megan Reitz, Professor of Leadership at Ashridge Executive Education, TEDx speaker and author of ‘Speak up: say what needs to be said and hear what needs to be heard’; Dr Indra Joshi speaking on gender bias in artificial intelligence and the need for diversity and inclusivity in health tech – a subject which will surely evolve and grow over the coming years; and Prerana Issar, Chief People Officer for the NHS who has previously worked at the United Nations and brought an international perspective to the call for diversity and inclusion at all levels and in all jobs. MWF Vice President Professor Chloe Orkin chaired a vivid and varied abstract session, including sharing her own experience of ‘trolling’ on social media following an appearance on television discussing new HIV treatments. The sexist bullying

afforded women doctors in the public eye is a deterrent to achieving leadership positions and must be challenged or ‘called out’ wherever it is detected. MWF also welcomed the first honorary male members for the first time in the organisation’s one-hundred-year history. The role of male allies is crucial to tackling gender bias at the highest levels and it is anticipated that taking this step will help raise awareness amongst our male colleagues of the challenges faced by women. The selected honorary members were: Prof Peter Brocklehurst, Prof Dian Donnai, Dr Simon Fleming, Mr Tim Mitchell, Dr Rak Nandwani and Prof Sir Simon Wessley. Each has shown substantial personal commitment to advancing the careers of women in medicine. Not all of the action took place on the stage. This conference heralded the formation of the new MWF External Relations Committee, formed of a group of medical students and junior doctors passionate about spreading the messages of MWF and reaching a wider audience. A bustle of social media activity ensued and #GenderBiasConf trended on twitter. Finally, it was heartening to see a large and diverse group of junior members and medical students meeting at lunchtime to talk about how they could contribute to the campaigns of MWF and what they could achieve by working together. We look forward as an organisation to a new and exciting era for MWF as we extend our network, embrace the younger generations of doctors and bring together women throughout the country. There are changes that need to be made, and we are the ones to make them.

SPOTLIGHT ON WOMEN’S HEALTH: RACE

Tackling racial disparities in maternal health: addressing and overcoming the current zeitgeist to effect change Melanie Etti is a junior doctor with an interest in global health who is currently working on a study in Uganda focused on improving rates of maternal and neonatal sepsis. She hopes to pursue a career in Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology upon her return to the UK.

In November 2018, the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity between 2014-16 was published. Here it was reported that 545 women in the UK and Ireland died during or within a year of their pregnancy during this time frame. Black women were identified as being five times more likely to die than white women and Asian women carried a two times greater risk.1 More recently, a meta-analysis published in 2019 looking at risks associated with stillbirth in 15 million pregnancies of women across the United Kingdom (UK) and United States (US) found that black women are twice as likely than white women to deliver a stillborn baby at all gestational ages, independent of all other risk factors.2 While these statistics are shocking, they represent the continuation of a legacy of poorer healthcare outcomes for black and minority ethnic (BME) people in the UK, as was outlined in the Acheson enquiry into Inequalities in Health more than 20 years ago.3 But why does this remain the case? Despite the apparent simplicity of this question, the answer is difficult to unravel in its complexity, however it appears to be rooted in the unconscious bias and systemic racism that continues to permeate the culture of many Western healthcare systems to this day. Examples of such racism are not difficult to find and not as covert as many might think. In 2017, London-based textbook publisher, Pearson Education, issued a public apology after excerpts from their textbook ‘Nursing: A Concept-Based Approach to Learning’ began to circulate on social media.4 In a section describing cultural differences in responses to pain, a number of harmful stereotypes were listed relating to various racial and religious groups, among which were the statements “Blacks often report higher pain intensity than other cultures” and “Muslims must endure pain as a sign of faith in return for forgiveness and mercy”, with the understanding that one person can belong to both groups clearly lacking in this instance. Such baseless assertions as to the monolithic behaviour of people of different cultural backgrounds are at best, an inadvertent declaration of ignorance, and at worst, permission for the continued ‘othering’ of BME people in a way that allows practice to deviate from patientcentred care. This section was subsequently omitted in more recently published versions of the textbook, but it is disappointing that it took a public outcry for this course of action to be taken. Toxic beliefs such as those mentioned previously only act to further 18 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

reinforce the shortcomings in healthcare provision for pregnant BME women and new mothers, for whom such inadequacies can have a catastrophic outcome. One notable figure who spoke out about her poor experience following the delivery of her daughter just over two years ago was tennis player, Serena Williams. Shortly after the birth of her child via caesarean section, Williams, who had been diagnosed a pulmonary embolism 15 years prior, developed sudden onset shortness of breath.5 She describes relaying her symptoms to her nurse, only to be told that her pain medication was likely making her confused. Only when she challenged this were further investigations arranged. A subsequent CT pulmonary angiogram revealed multiple pulmonary emboli. This account is a stark reminder that this is an issue that transcends socio-economic status, affecting women of colour at both ends of the wealth gap. Unfortunately, we know that those who view themselves to be in a position of less power have greater difficulty asserting themselves in similar circumstances, making such dismissals all the more dangerous. Research conducted by the Nuffield Department of Population Health at the University of Oxford between 2010 and 2018 led to the outlining of a number of key themes relating to BME women’s experiences of maternity care in the UK.6 Amongst the key experiential themes identified were ‘please believe me’ and ‘choices denied’, with ‘stereotyping’ also emerging as a major theme within this research. Of the women surveyed, fewer BME women reported feeling that they were treated with kindness, nor felt sufficiently involved in decisions relating to their care. In addition to identifying these differences in self-reported patient experience, a number of key differences in access to maternal healthcare between racial groups were also identified; BME women were found to have had fewer antenatal scans and less screening than white pregnant women and had fewer home visits from health visitors in the postnatal period. There were also significant disparities in the birthing experience between racial groups. BME women were less likely to be offered pain relief during labour and Black African women in particular were more likely to deliver via emergency caesarean section than any other racial group surveyed, a statistic that cannot be explained by varying physiology alone. In the face of these chilling facts, it is evident that little has changed since the Acheson enquiry. While confidential enquiry provides

SPOTLIGHT ON WOMEN’S HEALTH: RACE

Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 19

SPOTLIGHT ON WOMEN’S HEALTH: RACE

the first vital steps to identifying where things are going wrong, further work is required to establish how and why. This need is both essential and urgent, as only then can we begin to enact policies and change practice in a way that has a material effect on healthcare outcomes for BME women. One important aspect of this work should be the continued engagement of BME women in order to truly understand their lived experiences, re-enfranchising women who may have felt ignored and suffered as a consequence. Further work should also be done to understand and examine the feelings and attitudes of healthcare professionals to determine what bearing this has on why the provision of maternal healthcare for BME women continues to fall short. The outcome of this work may be uncomfortable, and may reveal complicity throughout the NHS, but change cannot occur without acknowledgement and acceptance. The desired outcome is change that results in equitable treatment strategies that improve the chance of survival for all women throughout and after their pregnancies, with the additional difficulties that befall BME women being appropriately accounted and adjusted for along the way. 20 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

References Bunch, K. and Knight, M. 2018. ‘Maternal Mortality in the UK 2014-16: Surveillance and Epidemiology’, in Knight M, Bunch, K., Tuffnell, D., Jayakody, H., Shakespeare, J., Kotnis, R., Kenyon, S., Kurinczuk, J.J. (Eds.) on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2014-16. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford: p5-22 2 Muglu, J., Rather, H, Arroyo-Manzano D. et al. 2019. ‘Risks of stillbirth and neonatal death with advancing gestation at term: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies of 15 million pregnancies’, PLOS Medicine. 16(7): e1002838 1

3

Acheson, D. 1998. Independent Inquiries into Inequalities in Health. The Stationery Office, London

4

Sini, R. 2017. ‘Publisher apologises for ‘racist’ text in medical book’. BBC News. 20th October [accessed 1st March 2020] Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-41692593

5

Haskell, R. 2018. ‘Serena Williams on Motherhood, Marriage and Making Her Comeback’. Vogue. 10th January [accessed on 1st March 2020] Available from: http://bit.ly/3d9Vx8U

6

National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit. c2018. ‘Policy Research Unit in Maternal Health & Care (2010-2018) - Women’s outcomes and experiences of care’ [accessed 2nd March 2020]. Available from: http://bit.ly/2ISM87A

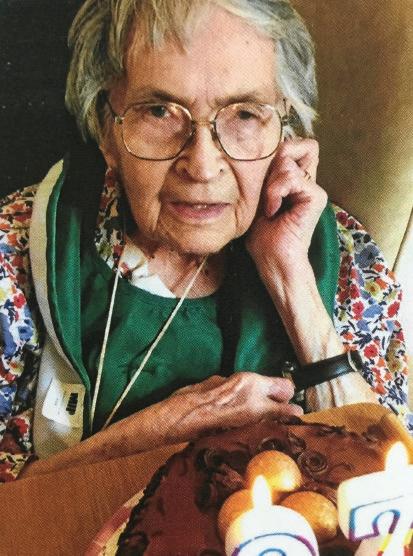

OBITUARY

Dr Thelma M Phelps MFCM Thelma was born in 1922 in south London. She attended the Mary Datchelor School and The Royal Free Hospital medical school for women. Her father believed that money spent on education was never wasted. Shortly after the start of the first year of the course the second world war broke out and the students were evacuated to St Andrews. In the second year, they were sent to Exeter and the clinical years were spent in and around London. Thelma qualified with LRCP MRCS in 1944 and MB BS in 1945. After house jobs in East London she married and moved to Nottingham. While her children were small, she worked as a dental Anaesthetist for 17 years. Thelma then made a move to public health and studied full time for the Diploma in Public Health in Bristol in 1969/70. She worked as a Specialist in Community Medicine in Nottinghamshire until she retired in 1987. Thelma was a member of the Medical Women’s Federation for 65 years and was enthusiastic in her support of women in medicine. Thelma died of a stroke on 26th October 2019 aged 97. She is survived by a son and a daughter who is a consultant Geriatrician, two grandsons and two granddaughters one of whom is a GP and the other a medical student, and five great grandchildren. Dr Rachel Angus, daughter

I met Thelma when we became neighbours over thirty years ago, and she was approaching retirement. We struck up a friendship when she discovered I was a young married woman doctor, and quite soon after, she started to invite me to local MWF meetings. Thelma was very strong-minded and fiercely independent and very encouraging and supportive of young women doctors. She was an enthusiastic and committed supporter of the MWF and was once the local secretary of the East Midlands Association as it was then, for 14 years, so she told me. In her retirement Thelma had many hobbies (doll making, upholstery, woodwork and entertaining her friends, to name but a few). For several years after she retired, Thelma was an independent visitor for children in care (she had been a medical adviser for adoption), and she always was interested in children and young people. Thelma enjoyed lots of social activities until well into her 80s, including attending MWF Spring meetings wherever they were held, as well as supporting local MWF activities and me in my first few years as local secretary. Several years ago, Thelma wrote about her wartime medical student experiences for Medical Woman. In her last few years, she lost her sight because of macular degeneration which was a great frustration. However, she continued to attend local group meetings until the last 2-3 years and remained interested in news of the MWF. She was pleased to be given life membership of MWF in 2017. To me personally, Thelma was a very kind, generous and supportive friend and neighbour. I learnt quite a lot from her about managing retirement and later on, the vicissitudes of old age, as she would put it. I shall miss her. Dr Yin Ng

Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 21

A GLOBAL STAGE: PALESTINE

Physicians for Human Rights Israel (PHRI): a right to health Dana Moss is PHRI’s International Advocacy Coordinator. With over 15 years working in think tanks and policy change organisations, Dana believes in multilayered advocacy strategies and the combination of storytelling, medical ethics and international law as effective tools in engendering change. Dana graduated from the University of Oxford, with an LLM in Law and M.Phil in Middle Eastern studies.

22 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

A GLOBAL STAGE: PALESTINE Physicians for Human Rights Israel (PHRI), one of Israel’s leading human rights organisations, advocates for the right to health of the most vulnerable communities in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory. Hand-in-hand with over 3,000 volunteers, PHRI carries out both humanitarian and policy change work to ensure a future where the right to health is applied equally to all those living under Israel’s responsibility.

Ghada Majadli is PHRI’s Director of the occupied Palestinian Territory department. Ghada conducts policy change work within Israel and advocates for the right to health and access to proper medical care for Palestinians. Ghada holds an MA in Human Rights and Transitional Justice from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a bachelor’s degree in Social Work.

It is a story of a small success in the face of an on-going, sisyphean human rights struggle. When Mariam, age 35, from the Gaza Strip, went for a regular check-up at her doctors, breast cancer was suspected. She was referred outside of the Gaza Strip to get a proper diagnosis. She received a medical exit permit from the Israeli authorities – without which she couldn’t access hospitals in East Jerusalem and the West Bank – and attended appointments and examinations, first in Hebron, then in East Jerusalem, where the initial suspicions were confirmed. As appropriate medical treatment for this type of cancer is unavailable in Gaza, she was referred for chemotherapy outside of the Strip in a Palestinian hospital in East Jerusalem. Yet suddenly, the Israeli authorities refused to give her a medical exit permit, leaving her with cancer, but without treatment. Mariam appealed to Physicians for Human Rights Israel (PHRI) – an Israeli human rights organisation in which the authors work – for assistance. Once PHRI wrote to the Israeli authorities, it was revealed that Mariam would receive a medical exit permit only on condition that she attend a security interrogation by the Israeli security forces, a practice which often serves as a means of basic information-gathering by the Israeli authorities and which renders patients as suspect of collaboration in the eyes of Hamas. Haneen Kinani, the staff member at PHRI who worked with Mariam to try and overturn the decision of the Israeli authorities, sees many such cases and notes “it’s frustrating to see how health permits are conditional for Palestinians, and not given as a right. For cancer patients every moment is critical – we hear their anxiety and worry in their voice when they call us – and the military neglects their situation.” In 2018, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), 9,644 patients from Gaza applied to the Israeli authorities for medical exit permit in order to receive appropriate care in the West Bank, East Jerusalem or in Israel, of which roughly a quarter were oncology patients. Roughly a quarter of those needing to leave Gaza for medical treatment elsewhere need to exit for cancer treatment, as nuclear medicine scanning, radiotherapy, and various surgeries are unavailable locally, as are many chemotherapy drugs. Although Israeli troops are not normally present in Gaza, Israel controls entry and exit from Gaza to other parts of the occupied Palestinian territory, namely the West Bank and East Jerusalem. East Jerusalem specifically is a primary location for many Palestinian patients from Gaza, as it is where most of the specialist Palestinian hospitals are based. From these 9,644 patients, 61% received a medical exit permit in time for their appointments: an approval rate which was, as per the local WHO office, ‘the second lowest recorded by WHO’.

PHRI is only able to help roughly 250 patients each year and each time patients do not receive a medical exit permit in time for their appointment, they must re-apply and the process of requesting appointments, submitting documents etc, recommences. As a result, thousands of patients either wait in Gaza and keep applying for a medical exit permit, try and cross through Rafah to receive medical care in Egypt, that entails a lengthy journey and considerable expenses to cover their stay there, or they give up, resigned to remaining in the Strip with ineffective and inappropriate medical care. The need for patients to exit the Gaza Strip to receive appropriate care has grown in recent years. The over decade-long blockade imposed on Gaza by the Israeli authorities has restricted the flow of people and goods, including medical professionals and medical equipment. This has resulted in the ongoing deterioration of the medical system, compounded by Israel’s numerous military operations, and the conflict between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority. Patients are directly impacted, with growing restrictions by Israel placed on their exit from Gaza. In 2012, according to the WHO, 92% of patients needing to exit the strip for medical care elsewhere received a medical exit permit in time for their hospital appointment. In 2017, this number plummeted to 54% and has only slightly risen in 2018. As restrictions have grown, an increasing number of women with cancer began appealing to an PHRI. From 2017 until 2019, PHRI helped 348 women who needed to leave the Strip, including 174 cancer patients. International resolutions, such as UN Resolution 1325, recognise that violent conflicts affect women and men differently and call on States and civil society organisations to assess the unique needs of women in conflict and post-conflict areas, as a precondition of policy change that accounts for women’s needs. Meanwhile, the World Medical Association has urged constituent members to ‘insist on the rights of women and children to full and adequate medical care’. To ensure that female cancer patients received their medical exit permits, PHRI launched a campaign. From 2017-2018, we worked together with Israeli civil society groups, including feminist groups and other Israeli organisations who then lobbied the Coordinator of the Government Activities in the Territories – the Israeli body in charge of issuing permits – on behalf of these patients. Simultaneously, over 30 top oncologists wrote to the Israeli authorities of the need to enable these women to access treatment. The international community also confirmed the stance of PHRI and the other organisations, with the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Health issuing a communique to Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 23

A GLOBAL STAGE: PALESTINE

the Israeli government on the impact of these medical exit permit denials. PHRI’s efforts culminated in a victory at the Supreme Court in mid-2018, which argued that the refusal of medical exit permits, and therefore access to treatment, to specific cancer patients on the basis of what the Israeli army termed ‘family proximity to Hamas’, was unjustified, disproportionate and illegal. By the end of 2018, the combination of these actions were enough to reverse the decisions in each of the patients’ cases that PHRI had received until then – namely, each of the 129 women who reached out to us received a medical permit, exposing arbitrariness of medical exit permit denials. We at PHRI cautiously celebrated, but since this success, and since PHRI paused its intensive campaign at the end of 2018, the numbers of female cancer patients who have requested our assistance has grown. In 2019, 26 women with cancer turned to PHRI, and it looks like these numbers are set to grow. In Mariam’s case, she finally received a medical exit permit after PHRI appealed to the Court. By then, she had already missed 2 hospital appointments – and she is one of the luckier ones.

24 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

A GLOBAL STAGE: PALESTINE

Unless established medical voices speak out, the likelihood is that this trend will continue. The UN Committee on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights – which reviews the Covenant in which the right to health is enshrined – called on Israel to ‘review the medical exit permit system with a view to facilitating timely access to all medically recommended health care services by residents of Gaza’. This is far more likely to happen if the Israeli medical community takes a stand that is aligned with medical ethics, as well as with human rights, and places internal pressure on the Israeli authorities to ensure that women – whatever their point of origin – access healthcare that is waiting for them only a few kilometers away.

Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 25

UNWIND: CREATIVITY AND MEDICINE

Empower the spirit: creativity and healthcare Jo Bowen is a Psychiatrist now working in private practice specialising in stress and trauma management for doctors. Jo has published research in the field of stress and illness causation. In 2019 she co-founded cRxeate. This is an online forum which aims to inspire all doctors in the empowerment of their creativity.

26 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

UNWIND: CREATIVITY AND MEDICINE In this article I will explain how I think the concept of creativity might be understood and applied to our everyday lives as women doctors. Along the way I will ask you some questions. I also want to introduce cRxeate, a project we have developed to empower creativity in all doctors and medical students. When I was working as an NHS Psychiatrist in the nineties I grew to realise that the word creativity was hardly ever mentioned by those delivering healthcare. The Chelsea and Westminster Hospital was one of the first to pioneer programs of arts in hospital settings and I recall how energised patients and my medical peers felt on setting eyes on some rather big colourful mobiles hanging off the foyer ceilings. They added spritzers of joy to signify that what happened there was worthy of an art installation. Nowadays, it’s hoped that creativity in healthcare is very much on the up! Arts for health organisations are taken seriously and the famous Wellcome Trust is a powerhouse in the field of medical humanities; #MedHum on Twitter. We see interest evolving in what is termed ‘social’ prescribing: exercise, hobbies, being in nature are all increasingly evidence based and valued in primary care. However, when it comes to the explicit valuation of creativity for doctors themselves there are still plenty of personal and professional barriers to overcome. One comment sums up a tendency to see creativity as an optional extra: as doctors we do a ‘relatively earthbound job’1. How can we doctors now argue against such creativity antagonists and why is it important to do so? Creativity like ‘stress’ is a nebulous concept. The term has to be carefully defined to be able to argue for it even if we begin by agreeing it involves a mental process we do not yet fully understand. TED talks on the subject feature a range of definitions implicating diverse ways of thinking and imagining. In our lives, where we must be inventive in order to find change that we want, it is therefore possible to see that creativity may be understood to be an essential part of being human. On this take, the creativity process is instrumental in allowing us to adapt and survive. Our ability to solve complex problems, to tolerate uncertainty and to direct our lives may be directly proportional to the quality and quantity of creativity we can muster. The heavy demands of our multitasking lives as individual women doctors come to mind here. Creativity is therefore most definitely not only for the likes of a creative genius - a Frida Kahlo or an Ada Lovelace. Nor is it an optional extra if we want to determine how well we live. So if we accept that creativity is about what we all do naturally, we can admit its vital role in our self-enrichment. Yes, it can lead to excellence in our learning and performance, even original outputs, yet it is also a part of our good enough functioning in our everyday life. There is a growing evidence base that our perception of our surrounding spaces benefits our functioning. Social aesthetics research and creative space projects focusing on how we can set up creative thought2 have also begun to demonstrate the added value of creativity. All sorts of arts and hobbies are increasingly recognised to help ‘flow’, a core concept in creativity theory3. Arts and hobbies, as shown by large population surveys, are understood to help with numerous angles of wellbeing: self-expression, joy, new learning, sociability, relaxation and ‘headspace’ feature strongly there. So the question I ask any doctor thinking about their own creativity is: how does your clinic or office space appeal to your most frequently used senses? Are you working optimally there as a doctor? Do those workspaces where you spend so much of your time feel in any way

beautiful to you or your patients? Do they suit your femininity or masculinity and how might that matter to you? Then also: how do you find immersion in ‘flow’ when you need it? Next, I turn to the business of sleep, something we should be prioritising for a third of our day, if current research is to be reflected in our practice. Research interest is increasing in emotional signalling, traumatic experience processing, and memory banking during different sleep phases and intriguing default brain systems. The physiological methodology, Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR), is well evidenced to treat psychological trauma and is hypothesised to be emulating REM activity. Furthermore, mental rehearsal is shown to be effective as virtual exposure within clinical hypnotherapy and creative visualisation. MRI brain scans are beginning to show us some awesome potentials of our imagination and thinking modes away from verbal activity. So, the questions about creativity I ask here concern how you are seeing, learning from and remembering your everyday experiences at work and home? In particular, are you getting good enough sleep, despite on calls or shifts, and hormonal fluxes, anxieties, conflicts and other caring responsibilities in your life? Do you daydream? Do you prioritise switching off? When medical trainees attend their 6 sessions of counselling, I have noticed a common trend. After a while, many would say to me something like “I want my heart to sing again” – they reflect that their passion for medicine had dulled. Although such a feeling of loss involves multiple causes, I have found that attention to modes of creativity can help much. As women doctors, we can make the most of our thinking and imagination as we listen and respond to what new we need for ourselves. A feeling of self-erosion and moral distress is a problem for us when we are so often achieving care for all except ourselves. How we look and feel in a world which might not reflect our values or sensory needs, how we get tired and isolated, even ostracised, how we take emotional risks, empathise, teach and support others and as seniors, bring in change we care about – that’s all where our creativity can come in to help us thrive. In an article about wellness and our potential, it is important to remind all readers of the signposts to currently available care for doctors4. With a further important reminder that many in our profession are working to reduce the stigma of getting care for doctors themselves5. We cannot use our creativity fully if we don’t feel well enough or in a good enough space to connect with it in the first place. Lastly, I want to mention a new creativity resource called cRxeate which we have developed for doctors, now that creativity in medicine is getting more recognition6. Do look in and join us all there if you would like. Together we hope to promote the everyday value of creativity to all in healthcare for an empowered future. I imagine many more initiatives to come. Let your creativity flow and flow. References 1 Jackson N., Creativity in Medicine, The Higher Education Academy, October 2005. 2

The Health Design lab, Jefferson University, USA, ongoing.

3

How to enter the ‘flow state’ for effortless creativity. Davis M, 2018. https://bigthink.com/personal-growth/what-is-the-flow-state Accessed December 19, 2019.

4 Wellbeing support services. BMA, http://bit.ly/33DKhNL Accessed December 19, 2019 5 Doctors

6

Support Network, Anti Stigma Campaign https://www.dsn.org.uk/ANDME_anti_stigma_campaign Accessed December 19, 2019 cRxeate. https://www.crxeate.com Accessed December 19, 2019

Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020 27

BOOK REVIEW

Fact and fiction:

the history of women in medicine Anne Pettigrew was a Glasgow-born, Scottish GP for 31 years. She is a medical graduate of Glasgow (Marion Gilchrist Prize, 1974) and Oxford (Med Anthropology MSc, 2004). Anne also worked in psychiatry, women’s health and journalism. On retiring, she took Glasgow University creative writing classes to pen novels about ordinary women doctors’ experiences.

Book Week Scotland Events spark interest in many quarters. At the historic Victorian Arlington Baths in Glasgow on 23rd November it was time to put Women in Medicine under the spotlight, triggered by sixties medical novel Not The Life Imagined written by Glasgow graduate and retired GP Dr Anne Pettigrew. A panel chaired by Glasgow Sexual/Reproductive Health Consultant Dr Pauline McGough (Medical Women’s Federation) led discussions on issues raised in the book: sexism, harassment and discrimination affecting women in medicine, then and now. Sadly, with the recently published Romney report showing sexism is still rife even in the British Medical Association (BMA) itself, there was plenty to talk about. A full house heard Anne talk about writing the novel with professional help from university classes, and her motivation as zero books record women’s experience in medicine except as pathologists or pioneers. She purposely wrote it as fiction, aiming for a wider audience, but admitted much of it was true (though not the burning of an incriminating body!). The history of women in medicine was touched on, from Crimean surgeon Dr James Barry (found to be a woman on his death) to Glasgow’s first graduate, Marion Gilchrist (1898), and the Edinburgh Seven, only awarded their 1896 degrees this year. Laughter greeted the ludicrous Lancet reasons given for refusing women entry to medicine e.g. having ‘loose tongues’ and ‘not knowing they were wrong unless they asked a man!’ Starting in 1967, the Summer of Love, Not The Life Imagined shows the gulf between then and now: no mobiles, no internet (library index cards needed for research), no pill if unmarried, termination of pregnancy legal but locally difficult, plus women in pubs and pre-marital sex were frowned on. Only 30% of medical school intake was female, becoming equal only in 1973. The book shows little overt discrimination until after graduation, but Anne read passages from the book demonstrating how girls were patronised, propositioned or passed over for promotion. The book highlights why people study medicine, ethics and many female topics: lack of role models, discrimination, harassment in the workplace. During discussions with the audience, it was noted women could also bully junior staff and that men suffered on grounds of ethnicity, sexual orientation or endemic bullying culture. Panel member Dr Sue Robertson (Associate Specialist in Renal Medicine, BMA Scottish Council Deputy Chair) pointed out that the bullying culture with ritual humiliation, seen as necessary for advancement in many specialities, has prevailed for decades and must be changed. Dame Daphne Romney in her report on the culture of sexism within the BMA made many recommendations they accept e.g. education on equality, diversity and inclusion and a helpline for staff facing sexism or discrimination. Someone pointed 28 Medical Woman | Spring/Summer 2020

From left Marina Politis (Chair, Glasgow University MWF), Dr Anne Pettigrew (author), Pauline McGough (Scottish MWF) and Dr Susan Roberston (Deputy Chair, BMA Scottish Council) at Women in Medicine