25 TOP

BEST KOSHER REDS AND WHITES

By Kenny Friedman

By Elizabeth Kratz

By Yossie Horwitz

By Kenny Friedman

By Elizabeth Kratz

By Yossie Horwitz

25 TOP

BEST KOSHER REDS AND WHITES

By Kenny Friedman

By Elizabeth Kratz

By Yossie Horwitz

By Kenny Friedman

By Elizabeth Kratz

By Yossie Horwitz

By Moshe Kinderlehrer

By Moshe Kinderlehrer

It gives me much pride and pleasure to present our third annual Jewish Link Wine Guide. This year’s guide, once again, is a true labor of love and passion project for our senior editors and judges, and it gives me tremendous joy for our publication to play an important role in supporting the kosher wine industry and its most passionate innovators. The guide this year is jam-packed with information about the many amazing things going on in the kosher wine industry, with new wines, new wineries, new faces, new techniques and approaches to winemaking, all featured in these pages. This year also represents a return to travel for myself and for our writers.

Although I am not, yet, a fullfledged oenophile, nor will I likely

serve as a wine judge anytime soon, I will say that I have learned a tremendous amount about wine over the past few years, and certainly learned a lot about the business side of kosher wine. While I have met and spoken with many winery owners, vintners, viticulturists, distributors and a négociant or two, as well as many educated wine aficionados over the years attending Kosherfest, KFWE and other kosher food and wine events, I had never visited a winery for tachlis purposes as the publisher of The Jewish Link Wine Guide until this past January, in Israel over yeshiva break. While there, I joined our Editor Elizabeth Kratz on a full day of visiting three wineries: Teperberg, Domaine du Castel and Tzuba. Elizabeth writes about her visits to these wineries and many more within these pages, and it’s a great read.

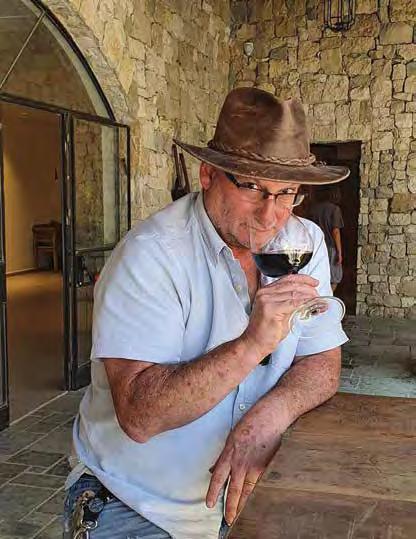

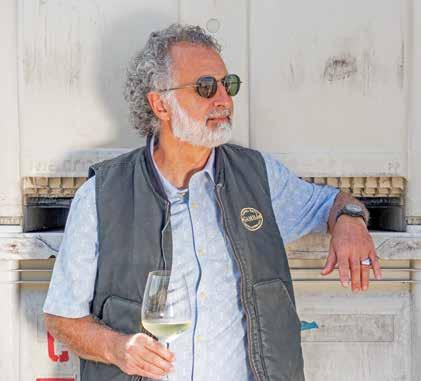

For me, my day trip was an incredible experience and each winery had its own charm and appeal. At Domaine du Castel, we met and spent time with its founder, Eli Ben-Zaken, who gave us a personal tour of all that he has built, and where I learned that he was the main owner of the famous Mama Mia’s dairy restaurant that anyone who visited Jerusalem in the 70s/80s/90s will remember. Small world. It was easy to hear the pride in his voice and see in how he carried himself as the founder while he gave us the winery tour and showed us his accomplishments of the past few

decades. Of course, we tasted many of his wines as well.

At Teperberg, one of Israel’s largest wineries, we had a chance to see their sophisticated and gleaming modern plant and the chance to be the first-ever guests of winemaker Dani Friedenberg in Teperberg’s brand-new visitor center. It was quite impressive and befitting for Israel’s third-largest winery. I was also deeply impressed by how seriously the mashgiach took his job in following us around to make sure that we weren’t getting too close to the barrels and pipes, or touching anything.

And at Tzuba, our final stop, we enjoyed the incredible views of this boutique winery on a Judean mountaintop and had a great conversation with the manager there. I tried paying attention to all of the discussions about taste, terroir, body and fragrance, and I believe I am on the way to finally beginning to understand what it is that I don’t know. And upon my return to the U.S., my wife made me promise that I would take her to some of these wineries, so it looks like winery visits will be part of any future travels in Israel.

With that said, we hope that you enjoy this year’s Wine Guide and that you will use it in good health to help guide your Pesach and seudat mitzvah shopping. And may this year continue to be one of goodness, prosperity and simcha.

Chag Kasher V’Sameach!

MANAGING

Michal

FOUNDING TASTING PANEL JUDGES

Yossie Horwitz

Jeff Katz

Greg Raykher

Daphna Roth

Yeruchum Rosenberg

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

Joshua London

COPY EDITOR

Cathy Fisher

ADVERTISING

Moshe Kinderlehrer

CONTRIBUTORS

Channa Fischer

Kenneth Friedman

Gamliel Kronemer

Yossie Horwitz

PHOTOGRAPHER

Bracha Schwartz

In Parshat Shelach, we learn of the sins of 10 of the 12 meraglim, spies, sent to scope out Eretz Yisrael after they had left Egypt. Ten came back with damaging lashon hara, spouting terrifying reports of a cruel land filled with giant, undefeatable enemies. Only Calev and Yehoshua, the last two spies, brought back a vastly different report, saying that not only was the land good, but it was “very, very good.”

(Bamidbar, 14:7)

During my visit to Israel this past winter, Ya’acov Ben-Dor, general manager of Yatir Winery in the Negev, explained that Israeli winemakers are not in competition with one another, but rather they stand together with a shared purpose. “Every time you drink wine or eat good fruit from Eretz Yisrael and you enjoy it, [when] you say, ‘Wow,’ your act atones for the sins of the meraglim, because they said lashon hara about Eretz Yisrael.

“And when you say the land is good, and the fruit is good, we reverse the sins of the meraglim; we are part of the evolution of those who came back home, and became am ha’aretz (people of the land) again. ‘Tova ha’aretz me’od me’od.' The land is not just good, it’s very, very good.’

In that sense, during my first trip to Israel in many years, this message helped ground me as I scouted out the goodness of the land. Traversing a

good portion of the country, I visited 15 wineries in virtually all of Israel’s wine regions. While I didn’t hit every one of the 15 regions as listed on the Israel Professional Enology Viticulture Organization (IPEVO)’s 2020 map, I got pretty close.

But one of my favorite wine memories of the trip was not at a winery at all, but at the tasting room adjacent to the Montefiore Windmill in Jerusalem’s Yemin Moshe neighborhood. Carmit Ehrenreich, who is VP and export director for Jerusalem Vineyard

Winery, took me through a tasting of the “Windmill Project” wines and Jerusalem Winery’s premium selections, my favorite of which was the Jerusalem Vineyard Winery Premium MRS 2018, a 100% marselan, redolent with a nose of fresh strawberries.

Ehrenreich, formerly of Yarden Winery, also works in a public relations capacity for several other small wineries, including one of our “wineries of the year,” Yaffo Winery. We spoke of the collaborative nature and shared expertise of Israel’s wine community. It’s interesting to note that virtually all of today’s most wellknown winemakers have worked at some point in their past at Yarden or Carmel; and that the message of the meraglim, Carmel Winery’s memorable logo image, continues to bring the world good wines from Israel, and therefore a good name. Another memorable moment of my trip was visiting Pierre Miodownick in his winery in Mitzpe Netofa in the Lower Galilee, where he brought me back to the basics as he quipped, “A good bottle of wine is an empty bottle of wine.” Miodownick, certainly the godfather of kosher French wine who made wine for Royal Wines in France from the late 1980s until 2015, considers himself one of the original

Israeli “Rhône Rangers,” who seeks to use the inspiration of the wines of France’s Rhône Valley in Israel’s warmer terroir.

The terroir not just in the Lower Galilee but in the Negev and elsewhere, certainly sets Israel apart in terms of experimentation. One thing that I learned at Yatir was that though they primarily make blends, they are passionate about pushing the limits of warm climate winemaking and have been experimenting with one single varietal wine since 2008: petit verdot. “We think we cracked the code of this wine as a single variety,” said Eran Goldwasser, Yatir’s winemaker. “We have four different plots of petit verdot and use a combination of them all.”

As petit verdot is often used as a component of the Bordeaux blend, it has only been in the last decade where we have seen it come to market from Israel as a single varietal, but now there’s a fair few. “It was not an easy thing to explain to the rest of the world, that it’s OK to enjoy a single varietal petit verdot, and that we make it,” said Etti Edri, Yatir and Carmel’s export director. “The different terroir and the topography here are different; what’s taboo in Europe is not the same in a warm country.”

“But this is not the terroir of Bordeaux, so [it follows that] we will not succeed with planting Bordeaux

blends here,” said Jacob Ner-David of the Lower Galilee’s Jezreel Valley Winery, noting that the original vineyards planted by Baron Edmond de Rothschild in the 1870s and 1880s are still relevant today. “Having said that, as you know, many wineries have managed to succeed in spite of the fact that Israel does not have classic Bordeaux terroir. But generally, his advice was to plant varieties that love the sun. Carignan was the one that Rothschild knew the best, so the carignan that we are drinking today are the grandchildren of what was planted back then.”

At Jezreel I also had the opportunity to enjoy a few magnificent tastes of various wines only available at the winery, paired with a next-level cheese plate (and truffle butter!) created by Jezreel’s on-site chef. An exceedingly distinctive wine that Ner-David sent me home with was made in a solera style, a barrel-aged riesling that had, quite literally, been left to age in the sun for eight years. This white port-style wine was immensely complex and viscous, with a beautiful nose of dried fruits and nuts that followed through to a lingering and clean finish. My Shabbat hosts were mesmerized and had never tasted anything like it.

In addition to using techniques and climate to the advantage of winemaking, there are also those interested in adding “native varieties” to their portfolios, going much further back than the 1880s and Rothschild’s carignan. Two winemakers in Israel—Dr. Shivi Drori of Gvaot and Guy Eshel of Dalton—are experimenting with newly discovered varieties based on plant laboratory research. Drori, whose winery in Givat Harel is near ancient Shiloh, has made a Beaujolais-style wine with the Bittuni grape; and Eshel in northern

Israel has made a similar wine using Zuriman, using clay amphora rather than barrels or neutral vessels to store and age the wine. Both varieties were developed by Drori in his lab at Ariel University, essentially working to find native grapes that had been lost to history on disputed lands. (When Israeli lands were taken over by Arabs, invariably they would pull up all the vineyards and plant olive groves.)

Eshel, a native Israeli who spent a good portion of his childhood in the U.S., studied viticulture at UC Davis. He worked with Ernie Weir of California’s kosher Hagafen Winery before coming back to Israel to do his military service and settle. In addition to serving as the primary winemaker at Dalton’s powerhouse winery, which now makes 1 million bottles a year, Eshel makes approximately 10,000 bottles through Dalton’s Asufa label; these are experimental, playful Galil blends that have a lot of native character and elegant fruit notes, influenced as well by his experience in California. Dalton is the northernmost winery I visited, in an industrial complex that also houses Adir Kerem ben Zimra and Lueria. Dalton also has recently acquired property nearby and has begun building a distillery, and sent one of its new products— an aromatic vermouth that exploded

with juniper and blossom scents—for us to try.

Gvaot’s Drori said he was inspired by one of his professors, Oded Shoseyov, who introduced him to the idea that he could both study plant science on an academic level and also use its practical applications in a winery. “The winery started in 2000, began producing wines in 2005, and it was good wine; better than we expected,” he said. “My first vineyard that we started with was a cabernet sauvignon vineyard next to my house, and this is one of our best vineyards today. It’s not irrigated at all. Its base is a very spongy limestone, so the wines are really mineralic, really interesting. I succeeded in growing

it without any water or irrigation for the last 10 years, which gives its roots a lot of depth.” Drori added that while he has spent his career in academics, most of his real learning has been in the winery, where he mentors many young winemakers coming out of his university’s viticulture programs.

South African vintner Richard Davis, of Kishor Winery, uses the influence of history and local research as well in his winemaking. He has been making wines in a beautiful village designed for adults with special needs on the border of the Upper and Western Galilee for the past 15 years. He explained that he started off making Bordeaux varieties, and then expanded to Rhône-style, noting that all the research he has followed is based on the wines made from Christian monasteries in the region, which have been making wine here continuously since the Byzantine era. Drori had also noted that his first wine consultant was of a monastic background, because only workers from this population have an unbroken chain of vineyard experience in this region before the beginning of the 20th century.

“Israeli wines have come up a hell of a lot; I don’t think anyone can say they are inferior to anywhere in the world,” said Davis. While not as many of Kishor’s wines are exported to the U.S., the winery is selling out their wines, so more can be expected. “We plan to increase our production to meet demand, to produce upwards of 130,000 to 150,000 bottles of wine,” he said. Particularly memorable for me was tasting Davis’s snappy and aromatic viognier, as well as an elegant Bordeaux-style blend.

One of the things I noted during my visit to Israel was the openness of the winemakers I spoke with, and their interest in learning from everyone around them. “There’s a natural tendency when you think of Israelis; you think we will always say, ‘We know, we know, we know,’” said Psagot Winery’s Sam Soroka, a native

Canadian with global winemaking experience (who also worked at Carmel!) whose experience in the Israeli wine industry spans 22 years. “But when you dig a little deeper, you will realize we are all still exploring. This is something to be proud of; there’s something about Israelis that is so ambitious. They will taste a great

wine and say ‘Oh! We can do that,’ and that’s why there are so many small wineries cropping up so quickly.”

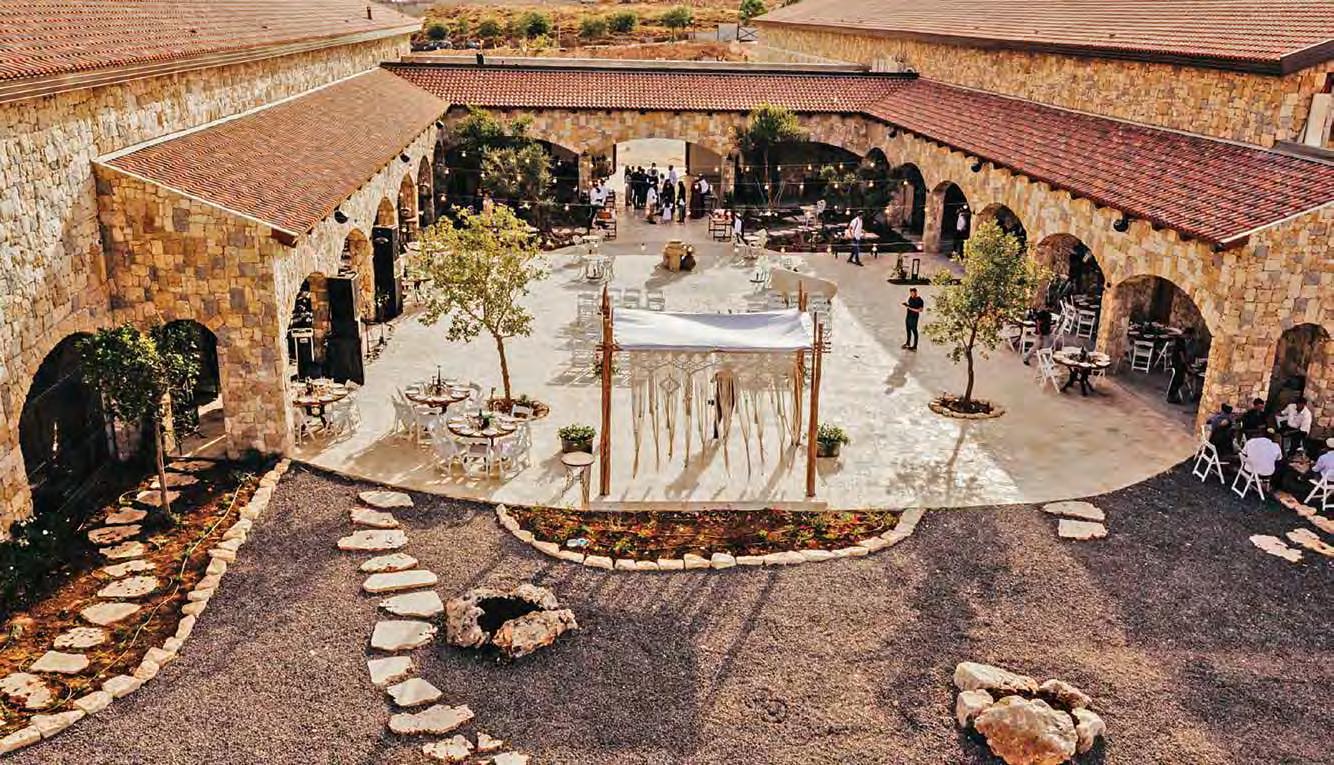

Psagot, which has a stunning new mountaintop tasting room (and enough room to dance at two weddings if they’re scheduled the same night!) overlooking vineyards in Sha'ar Binyamin, has spent this decade growing. It plans to produce over 700,000 bottles of wine in the coming year. Its wines are wellmade and polished, showing ontarget varietal aroma in its whites and rosés, and richness and elegant structure in each sip of red. Soroka’s experience as a winemaker in two hemispheres—with a diploma from Australia, vineyard experience in the Languedoc region of France, Western Australia, Napa and even in Canada, making ice wine north of the Finger Lakes—feeds his fascination with Israel's search for identity. “In some ways, Israel is still searching for its terroir,” he said.

In terms of growth, though, not all the winemakers I spoke with have the same instinct as Psagot to always be growing. “As demand increases, we have to be concerned with our quality staying the same. We are not trying to be bigger,” said Gilad Flam, of the Flam Winery in the Judean Hills, which produces 180,000

bottles annually. “We had this auspicious plan at the beginning, to make high-quality wines that reflect an understanding of the unique terroir we have here,” he said, referring to the winery’s highly individualized plots: in Givat Yeshayahu for chardonnay, the dry creeks of Ella Valley, and the Evan Sapir Vineyard at a higher 700-meter elevation, where the effects of the night last longer into the day and are very good for growing grapes.

Flam explained that his father, Israel Flam, graduated from UC Davis in 1968 and was chief winemaker at Carmel for many years. When his sons Gilad and Golan went to Europe to study wine, they decided they wanted to move beyond commercial winemaking. “When we went to Europe, specifically Tuscany, we learned that wine is not just something to make; it’s a story of a people and a bigger idea to tell the story of your soil.”

Initially, Flam added, it was not Israel who was the first investor in his sons’ big idea, but their mother, Camellia. “In 2019, after 20 years of the winery, we gave a 70th birthday gift to our mother, the 2019 Flam Camellia,” a smooth, fruity and exceedingly memorable chardonnay.

There are a few Israeli winemakers who stand virtually alone in their cellars, without consultants or experts, but with just an idea to go on and a passion to make it happen. An upstart winemaker I met, Eli Shiran, has been making buoyant and balanced kosher wines in an Arabdominated warehouse district in Kiryat Arbeh since 2012. They have been imported to the U.S. by KosherWine.com since 2018. His poetic, ironic sensibility comes through when sharing his wines, noting that he got into wine as a post-retirement project and his main goal is to “not ruin God’s creation.”

The winemaker continued: “Basically I am using the best grapes I can get ahold of and to try to not interfere with them too much. The best part is getting to choose the blend, which comes down to my personal taste. I am happy if other people like what I like.” Shiran makes wines named after musical themes, with a nod to his roots as the son of a chazan. Considering that last year he produced only 10,000 bottles, it’s quite an impressive feat for Shiran to have had at least four of his wines rank in different top 25 lists in the Jewish Link Wine Guide, granting him status as a “winery of the year.”

AGUR WINERY LIES ADJACENT TO ELAH VALLEY, IN THE BEAUTIFUL JUDEAN HILLS.

THE WINERY’S VINEYARDS, IN MATA, GIVAT YESHAYAHU AND EIN KEREM, PRODUCE A LIMITED NUMBER OF WINES WHICH ARE THE CREATIVE WORK AND ART OF A GROWER, A WINEMAKER AND A VINEYARD. EACH WINE IS AN EXPRESSION OF A PERSON AND A PLACE.

Eli Shiran

Eli Shiran

Itay Lahat, a winemaker who just celebrated his 10th year making wines under his eponymous label, met with me in the Upper Western Galilee, in Kishor. Lahat’s wines are aromatically complex and on the low-alcohol side. They are earthy but also fresh and refreshing. He is expert at blending, and conveyed his intensely polished approach to using just the right percentages of each variety to create a well-rounded, exceedingly balanced mouthfeel. In Kishor Village he explained that there is just one location where one gets the benefit of both the sea breeze of the Mediterranean along with the view of the freshwater of the Sea of Galilee. He explained that the wines he makes are reflective of the terroir, that magical mixture of climate and topography, that characterizes the region.

Lahat, a veteran viticulturist trained in Australia, lectures on Israeli wines around the world, and is also in great demand in Israel as a consultant. His experience, specifically with Rhône varietals, is evident wherever he consults, resulting in wines replete with minerality and elegance. For example, tasting Lahat’s roussanne from an amphora helped me understand what he seeks to do when blending it with other varieties. There was an aromatic and acidic aspect of the roussanne that would round out a

blend that also includes whites like viognier and sauvignon blanc.

It would also be difficult to write an article about experimentation and excellence in Israeli wines without mentioning the name Yaacov Oryah. Unfortunately, I was not able to meet with him while on this trip in Israel. But he sent his regrets along with wines for the Wine Guide, asking that they sit for one month to recover from bottle shock. While this meant we could not open most of them in time for the tastings, I made a special effort to taste them, as they are now being imported by KosherWine.com, and I know their availability is of special interest to our readers.

While we tasted few of the wines for which Oryah is famous—his so-called “orange wines”—we found Ya’acov’s Playground Chardonnay, made with chardonnay grapes from 13 vineyards, as well as the Silent Hunter (a semillon made in the Australian Hunter Valley style), to be particularly lush, beautiful and complex, as are his reds. His Black Pinecone (pinot noir) and A Place by the Sea (merlot) both made it to our top 10 lists in single varietals. We are looking forward to seeing and tasting more from Oryah in the coming years.

Finally, one great standout memory of my trip this past year was visiting two very different winemakers—Eli Ben-Zaken and Dani Friedenberg— in the same morning. That day I was with my publisher, Moshe Kinderlehrer, and we met with Ben-Zaken, an elder statesman of Israeli wine who has built an empire in Razi’el and a famous name for French-style wines from Israel; and Friedenberg, of one of the largest wineries in Israel, Teperberg.

Seeing high-quality wines made to exacting standards in two extremely different locations within a half hour of one another in the Judean Hills region was yet another poetic example of the type of country Israel has become. We sat in Domaine du Castel, a boutique winery built virtually brick-by-brick by one man, Ben-Zaken, who spoke to us in an elegant tasting room, and later visited Teperberg, a huge commercial factory complex sufficient to house Israel’s fourthlargest winery.

The legendary, elegant, restrained Bordeaux blends that Ben-Zaken makes need no introduction to our readers; and his newer winery on the same site, Razi’el, will soon likely become as well known, with Rhône-style blends.

That following Shabbat, tasting a fruity, smooth Barbera from Friedenberg’s “by Teperberg” project, alongside a Teperberg Inspire blend of malbec and marselan, showed the variety of fine wines Israel offers, from the handmade to the commercially produced. From a $25 Teperberg Inspire to an essentially “priceless” wine that Friedenberg hasn’t yet begun exporting, tasting the wines of Israel is an experience that is truly tova ha’aretz me’od me’od. But did they measure up to Pierre Miodownick’s definition of a good bottle?

Yes, they were both empty.

Made of Sde Calev Vineyard's choice grapes, Ya'ar Levanon epitomises the restoration of an ancient winemaking heritage, blended with the finest French winemaking tradition. Ramat Hevron, the historic wine-growing region dotted with wine presses dating back to the Temple days, once again produces wines fit for a King. Savor them!

By Joshua E. London

By Joshua E. London

The secret to creating good wine, it is often said, is to start with good grapes. The trick, of course, is ensuring a stable supply of quality fruit. With increasingly undesirable weather patterns and events making life difficult for wine growers in much of Europe, wine-industry interest has been piqued as to how Israel works its magic. The ability Israel has developed, to make the desert bloom despite high temperatures and arid conditions, includes highly innovative approaches to viticulture.

“European wine producers are worried about climate change,” noted Enrico Peterlunger, professor of viticulture and vine biology at the University of Udine in Friuli, Italy. “They are looking at the way producers in Israel are dealing with harsh

conditions because due to climate change they are concerned that this is the future that awaits them.”

The term “climate change” is the common or popular catchall for the phenomenon of significant longterm shifts in temperatures and weather patterns. Viticulturalists and winemakers tend not to focus on the partisan politics that climate change sometimes engenders, but rather towards practical, constructive and localized approaches to coping with the very real environmental conditions they face each vintage. Simply put, they try to do the best they can with what they have, because the grapevine is a woody perennial with an annual growing cycle. Even minor changes in environmental conditions can lead to significant shifts in how grapes develop. Increasingly,

many in the wine world have become very receptive to, and nervous about, the dire predictions from climate change experts.

As Laurent Audeguin of the French Wine and Vine Institute told France24 news this past summer: “The 2022 vintage is complicated for the French wine industry … The heat causes the grapes to burn and ripen too early in most regions; the necessary aromas don’t have time to develop” while the rise in temperature also “lowers the acidity of the wine and increases the alcohol content … So the whole balance is disturbed … The quality is affected but so is the quantity of wine we can produce.”

Meanwhile, the widely celebrated agricultural developments in Israel seem to offer a hopeful counterpoint.

Developments in the Negev region have attracted particular outside interest.

The modern state of Israel, driven by necessity, had to cope with the harsh and extreme realities of its environment very creatively. Amazing agricultural technologies like drip irrigation were created, pioneered, and scaled in Israel, and soon thereafter exported around the world.

Israel is mostly arid land, after all, with the Negev making up more than 50% of the landmass of the country. Israel wine expert Adam Montefiore noted that although “only around 5% of Israel’s vineyards” are in the Negev, “there is immense interest worldwide in Israel’s desert wines.” His compelling hypothesis is that the Negev vineyards “symbolize the prowess of Israeli agriculture in ‘making the desert bloom,’” and “represent both advanced technology and Israeli creativity.”

Last winter, winemakers from Bordeaux took a trip to the Negev to look at the technology and vineyard strategies that winemakers have developed. One of the wineries they visited—one that has been pioneering its own trial-and-error path of ingenuity since its founding—was the Yatir Winery. Established in 2000 as a joint venture between the Carmel Winery

and local winegrowers, Yatir was built at the foot of the Tel Arad archeological site in the northeast Negev desert, about 10 minutes away from the vineyards of the Yatir Forest.

As Yatir winemaker Eran Goldwasser put it, the hot and dry conditions the Bordeaux region has been experiencing of late illustrate “why they need to learn and adapt.”

Goldwasser’s recollection of the French delegation’s visit to Yatir was that “they came to us very open [minded]; they didn't have a clear

agenda, they just wanted to listen and see and understand what we are doing to try and mitigate the facts they are facing of aridity and heat.”

One of the academics a previous French delegation met with was Aaron Fait, a researcher and professor of biochemistry with the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research at BenGurion University of the Negev. “The Negev desert can be used as a model system for climate change scenarios and desertification scenarios,” he explained. “We have different experimental plots in different areas which have average temperature differences mimicking the increase of the 2 degrees Celsius that has been predicted in global warming models.

“We can control a large number of variables like nowhere else” and certainly not like conditions “in any traditional vineyard,” Fait continued. Which means that one can “use the Negev agricultural system as a model to test the best strategies to adapt to common climate challenges.”

Furthermore, he said, in the Negev “we have very interdisciplinary collaboration on the same systems.” That is, the vineyard system they’ve developed at the Blaustein Institute is unique in that they “have agronomists, water scientists, biologists and biochemists join forces to study from

a holistic perspective the behavior of the plant under certain environmental conditions and challenges.”

So, what are some of the big Israeli lessons for wine producers outside of Israel?

According to Goldwasser, “The two immediate topics are irrigation and canopy management.” Irrigation because “they need to supplement what nature provides” and ensure sufficient watering of the vines, and canopy management “because increasing temperatures necessitates adaptation.”

The term “canopy management” refers to vineyard management techniques used to support and train the aboveground parts of a vine to better position the exposure of leaves and fruit to the sun and to allow for optimal air circulation to reduce the risk of fungal disease.

The most common management system in modern viticulture is a trellis or framework of wood or metal around which to train a vine’s growth. In its simplest form, a trellis is just a stake

driven into the ground beside a vine, to which the vine trunk or shoots are tied. Wires are also used to support the vines and leaves, with posts installed at intervals forming neat and tidy rows.

“You know, a vine is beautiful in the way that it has fruit and the leaves that are protecting the fruit from the sun,” Goldwasser explained. “If you have too much leaf shading, that’s not good because the fruit won’t ripen, so what they do in Europe usually when they don’t have enough sunshine is to position the shoots and the leaves in a very vertical way, so the [grape] bunches, the berries, are fully exposed to the sunshine.”

“The popular canopy concept in much of Israel, and elsewhere, is to use a VSP or Vertical Shoot Position [trellis system],” Fait said. This is where the vine shoots are trained upward in a vertical, narrow curtain with a fruiting zone positioned just below, “often doubled in a Y shape, or single like an upside-down J.” The VSP position is one of “the most popular because

you can grow the vines more densely, you can produce more [fruit], and the [grape] clusters are totally exposed to the farmer, but that’s also the problem. The clusters are really … totally exposed to the solar radiation [heat].”

The heat and sun exposure of the Negev desert can be punishing, not so dissimilar to the heat waves

that have been plaguing many wine producers in Europe. So, in the Negev, explained Fait, “even though the barometric temperature can be like 30 degrees Celsius [86 degrees Fahrenheit], the incident temperature, the surface temperature, can go up to 50 degrees Celsius [122 degrees Fahrenheit]. This is every day for two months—which is just too much.”

Too much sun exposure and too much heat tend to produce fruit that is overripe with “too much sugar content.” This in turn generally produces wines with “too much alcohol, and can lead to the oxidation of aroma, and baked fruit notes, and sunburn and fruit drying on the vine,” Fait said.

“In our conditions [in the Negev desert],” Goldwasser noted, “it’s much wiser to have the leaves spread out to provide good

protection [from the sun] but done judiciously so you don’t block the berries completely from the sun; you give them partial exposure to the sun and partial protection.”

“One treatment we applied was to open up the canopy so as to create a sort of natural shade on the clusters, “Fait said, “which was quite effective, although this created a greater need for water as the leaves soak up more of it. This increased the amount of irrigation needed by 40%.”

In Fait’s collaboration with the Teperberg Winery, this open-canopy application “led to real improvement in their gewürztraminer grapes”— improvements that were noted not only through professional and scientific evaluation, but also in the finished wine.

When it comes to the issue of irrigation, parts of Europe still

have some regulatory hurdles that allow irrigation only sporadically. In an important essay called “Bordeaux, Burgundy—it’s time to irrigate!,” published on the JancisRobinson.com website on August 2, 2022, Dr. Yishai Netzer, a plant physiologist specializing in irrigation studies at Ariel University’s Eastern R&D Centre, and Eran Pick MW, the winemaker and general manager of the Tzora Vineyards winery in Israel’s Judean Hills region, made a compelling argument for liberalizing the use of judicious irrigation in European viticulture.

“Winegrowers around the world know the changes in the vineyards all too well,” Netzer and Pick argued. “Climate change affects everyone, as witness the Po River drying up; major heat waves in France, Spain and Portugal; huge wildfires in California and Australia; and winters with almost no chill in eastern Mediterranean coastal areas.”

Arguing that water availability to the soil is a key component of a wine’s development, they noted: “As in humans, water is life for plants. Water is also essential for plants to transpire, photosynthesise and to produce secondary metabolites (flavour). Each stage of the growing season could in theory have an optimal water status for the plant and for fruit quality (not necessarily the same water status). Water availability has an effect on quality, quantity and character of the wines made.”

Drawing directly from their experience growing wine in Israel, Netzer and Pick observed that there are already appropriate scientific measures to “evaluate the level of water availability or stress of the plant” and that, of course, determining how much water is needed “depends on the soil type, climatic conditions and cultivar planted among other parameters.”

They further argued that thoughtful irrigation posed no significant hurdles to the expression of what the French refer to as a wine’s terroir—which loosely translates as “a sense of place.” Indeed, Netzer and Pick go so far as to assert, “Consistency of character can even be improved,” and “irrigation does not change terroir any more than composting, heating the vineyard to avoid frost, or even winter pruning and other standard vineyard operations.”

To Fait, refusal to deal with water shortages and adopt irrigation is a fundamentally unsound approach. “The only way to make viticulture and winemaking sustainable worldwide is by using drip irrigation systems, by stopping to use up freshwater from lakes, by reclaiming water through recycling and by desalination.”

One twist on the drip irrigation technology in use at Yatir, noted Goldwasser, is subsurface drip irrigation. “We are uniquely going one step further by putting the drip irrigation lines one foot underground, so we lose less water to evaporation, and it also forces the roots of the vines to dig deeper for the water, which is a good thing for the ecosystem of the vine and the root system, and it gives the vine more resilience; we think it also gives better fruit and better wines.”

“Usually, the farmers that we work with don’t use subsurface drippers, they use surface drippers,” said Fait, the Ben-Gurion biochemist. However, to improve efficiency, they use another Israeli innovation of plastic mulching— strips of plastic sheeting running through the vineyard that essentially hug the vine’s stems and cover the ground. So, “the surface irrigation drippers run just below the mulching, which helps further prevent water evaporation.”

There is plenty more to be learned from Israeli viticulture and winemaking, and not just in the Negev. It remains an open question, however, as to just how much and just how quickly the rest of the wine-producing world wishes to learn from Israel and adapt, using new methods and approaches.

Kosher wine education has taken a dramatic turn; a deepening knowledge base that was begun by many during the COVID lockdown has continued during the post-pandemic phase. Many non-kosher wine experts have found certificate programs to better their knowledge and depth of the subject, but for many years, the vast majority of kosher-keeping wine professionals have been privately or self-taught.

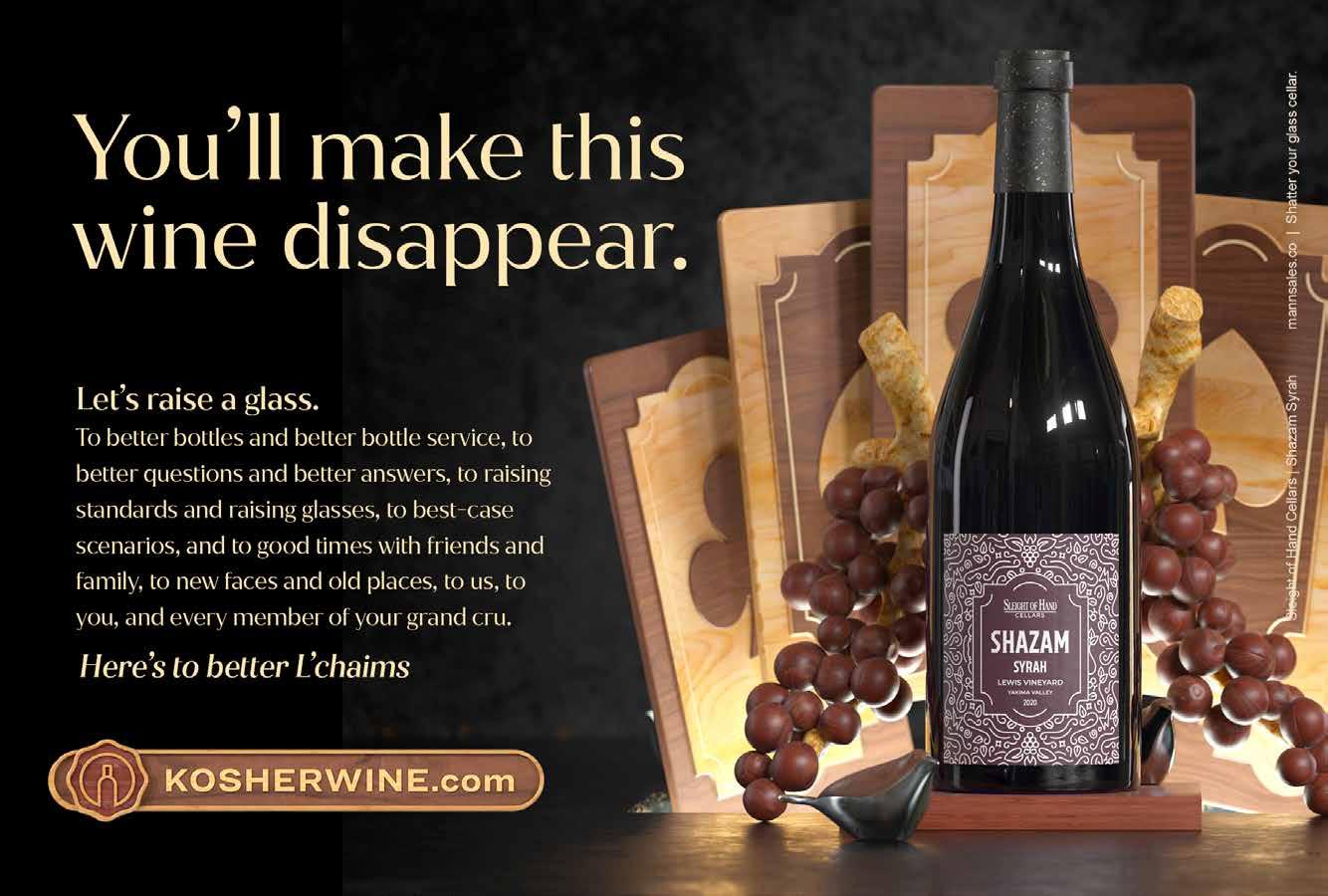

In 2021, kosher-keeping wine enthusiasts saw the introduction of a Wine & Spirit Education Trust (WSET) Level 2 course, and this past year, a kosher WSET Level 3 course was offered for the first time ever in America; both courses were offered through KosherWine.com. Pulling together these high-level courses was no easy feat, but the passion and drive of KosherWine.com CEO Dovid Riven and Lead Wine Consultant Brad du Plessis, along with a dedicated instructor and an enthusiastic cohort, could lead to major professional advancements in the kosher wine world.

Both Riven and du Plessis are no strangers to advanced wine education; they both are currently in pursuit of a

wine diploma (WSET Level 4) from Capital Wine School in Washington, D.C. Riven, based in D.C. himself, began toying with the idea of offering a kosher WSET Level 3 course— something which he thought could catch on for industry professionals and aficionados alike. But how would he pull it off?

Riven explained that unlike Level 2, which does not have any tasting component in the exam, WSET Level 3 can be complicated for kosher-keeping students who must participate in a tasting examination. “Anyone who registers for a Level 3 course has no way of ensuring that the wines being tasted will be kosher,” he said. “It ultimately boiled down to finding a wine school that would be able to work with us on putting this course together and help us match the

requirements with kosher wines that are available.”

Riven approached the owner of Capital Wine School, Master of Wine (MW) Jay Youmans, for help on building out the kosher WSET Level 3. “We discussed what would be involved and what the hurdles are; and he ultimately told me that we can make it work. So we got to work on making it work,” said Riven.

“[Riven] really had the sense that we would be able to pull this off,” said Youmans. “We did not have any expectations other than the fact that I know the bare minimum about kosher wine, but it was a fast study. We really pulled it off.”

Youmans was curious about how different a kosher Level 3 course would be, and checked with one of his students who works for WSET. “She told me

that as long as you taste the required wines, there are no issues with it. So we covered every category … we had all of the bases covered,” he said.

Rivens and Youmans worked together to match the certification requirements with kosher wines, and were mostly successful, with a few exceptions. “We were able to maneuver around some of those exceptions. For example, oloroso sherry just doesn’t exist in the kosher world, and we dropped it; it ended up not being on the exam at all, so it wasn’t an issue,” explained Riven. In total, the kosher WSET Level 3 course managed to taste a total of 28 wines, coordinated with help from du Plessis, who managed the operational side of the course.

“There may not be a ‘need’ for highlevel certification in the kosher wine world, but there is certainly a ‘need’ for offerings that are available to the non-kosher world that we can do, too,” Riven said of the pursuit to put together the Level 3 course. “If we can do it, why shouldn’t we? There’s an interest in the kosher market for exploring and taking things to the next level, and seeing how much enrollment we have in our Academy courses, I

knew this is something we should do as the leading kosher wine retailer in the U.S.”

Riven is referring to the Kosher Wine Academy, an online set of courses offered by KosherWine.com for enthusiasts who want to learn a little more about the kosher wine world. He described these courses as casual compared to the WSET courses, but did not discount their value, noting that a handful of the Level 3 students came from the Academy 202 course. “Our Academy 200-level courses are comparable in a lot of ways to the WSET Level 2, in the sense that they both explore regions, styles of wine and the like. There are people who took the 200-level courses who were ready to take on the WSET Level 3 with a solid foundation,” Riven explained.

Du Plessis, who called the Kosher Wine Academy “his baby,” noted the same growth from Academy students and a need for a higher level course offering like the WSET Level 2 and Level 3. “The academy is very approachable and consumable. So when we offered WSET Level 2, a bunch of people reached out and said, ‘We

loved your class, we want to learn more, is this the avenue to go?’ and I always told them that the WSET is absolutely the way to go,” he shared. “There were a handful of people who went through the Academy and all the way up to WSET Level 3, which is pretty amazing. I feel like a proud parent.”

Riven and du Plessis pulled together a cohort of about 30 students, which exceeded their expectations. As with other wine courses offered by KosherWine.com, the classes were given online—but this time, they were led by Youmans himself, who had never really tasted kosher wine before.

“In a blind tasting, you would never know these wines were kosher,” said Youmans of his newfound kosher wine experience. “There are a lot of really high-quality kosher wines available on the market. You can’t tell the difference.”

Jewish Link Wine Guide Editor Elizabeth Kratz, one of the students in this first-ever WSET Level 3 course, observed Youmans’ statements that

quality kosher wine don’t differ in any measurable way from non-kosher wines. She said that one of the major benefits of this course was “having a teacher who was not from the kosher wine world, and listening to him taste the wines as we were tasting them … he indicated that these wines, which he had never tasted before, were on par with the wines that he has in his other classes.”

Kratz overall found the course to be “very valuable,” and an exciting way to expand on the knowledge she gained from passing the previous year’s WSET Level 2 course, also offered through KosherWine.com. “I feel like Level 3 gave me a lot of skills in terms of understanding the wine processes, as well as the different kinds of wines of the world, geographically speaking; as well as how they are made and how careful winemaking affects the product that ends up in our glasses,” she said.

Kosherwine.com’s Level 3 course ran for a duration of 10 weeks, with students tasting three to four kosher

wines per class in preparation for the exam. “Level 3 is not about guessing the wines,” explained Youmans about his approach to teaching the course. “It’s about calibrating your calls on a list of things like color, appearance, taste, acidity and tannins. During those weeks, we just went through the wines and broke them down.”

“Level 3 covers a lot,” said Riven. “It ends up being about 50 hours of reading and coursework, whereas our top-level Academy courses are somewhere in the 12-hour range.” And, after 50-odd hours of studying and tasting the wines with Youmans, the WSET Level 3 cohorts took their exams, complete with an entirely kosher tasting component.

The exam is a total of two and a half hours long. “It’s really to see how well you can calibrate and assess those different things in the wine,” said Youmans. “There’s a theory section that’s multiple-choice and four shortanswer questions. You have to know the material very deeply.”

“Once you’ve reached Level 3, you’re pretty confident in your tasting, at least to the extent that you can describe the characteristics of the wine in your glass,” explained Kratz. “Describing the wine according to the Systematic Approach to Tasting (SAT) is definitely not the most difficult part of the exam.”

So what was the most difficult part of the Level 3 exam? “The essay questions ask you to apply information you learned from studying certain winemaking regions and to other regions of the world, or questions about climate and how winemakers deal with things like topography and weather patterns. These are really intensive, in-the-weeds questions,” said Kratz.

The timing of the most recent exam was planned in synchronization with the 2023 Kosher Food & Wine Experience (KFWE), an annual event hosted by Royal Wine Corp. Youmans and the students who traveled to the New York area for the WSET Level 3 exam were able to attend KFWE with the new wine

knowledge now top of mind. A second Level 3 exam with kosher wines for the tasting component was scheduled to take place at the Capital Wine School in April.

At this current moment of writing, the first cohort has not received the final results of their exam, and are still considered Level 3 candidates. But to Kratz, the certification isn’t as important as the knowledge gained throughout the course.

“As the editor of a wine publication like this one, it’s important for me to understand the wines of the world and have as much understanding as possible as the wine professionals who send us their wine,” she reflected. “This course gave me a strong base in that. And there is an incredible value in people of the kosher wine world deepening their understanding; the more knowledge we have in the kosher wine world, the more impetus there will be for winemakers to continue improving their selections and reaching ever higher. The finest kiddush Hashem we can make in winemaking is ensuring that kosher wine continues to thrive from generation to generation.”

For now, WSET Level 3 may be the highest level a strictly kosher-keeping wine enthusiast can reach. Riven explained that WSET Level 4, which is the diploma level, brings on its own set of complications when it comes to keeping kosher.

“The Systematic Approach to Tasting (SAT) is about calibrating your process of tasting wine to your instructor,” said Riven. “There’s a very consistent method there which we can’t replace when it comes to the tasting.” He continued that while this was relatively easy to navigate for the Level 3 course, it would be an enormous challenge in a hypothetical kosher WSET Level 4 course.

“We’ve thought about having the individual wine schools commit to hosting a kosher exam at least once per year, to take the pressure off of gathering a large enough cohort for a Level 4 course. We could even coordinate having kosher wines tasted during the course, but logistically speaking, it’s a lot,” he explained.

“Schools send out samples of wines to the students, which presents issues with non-mevushal wines and makes the selection restrictive,” Riven said of the course structure, which he added has become more prominent since the onset of the pandemic. “While it’s relatively simple for us to choose kosher wines for the exam— since those wines follow general parameters and don’t need to be a specific brand—it’s complicated to regulate the wines that are being tasted during the course itself. It’s really important to calibrate your palate with the instructor, and that makes it difficult to choose your own assortment of wines to taste. How can you study for the same exam without tasting the same wines and having the same instructor?”

Logistical nightmares aside, Riven pointed out that there is an entire section of WSET Level 4 that presents a kashrut problem:

fortified wines. “Only two or three styles of fortified wine are actually kosher. For example, a huge chunk of that section is on Madeira, but not a single kosher Madeira has ever been produced. These types of wines make it impossible to do a Level 4 course for kosher-keeping students.”

But the good news is that high-level certifications may not be the ultimate goal for those interested in deepening their wine knowledge. “I don’t believe that any sort of formal wine education is important for the vast majority of people,” said du Plessis. As an alternative, he encourages more informal presentations on the “deep concepts of the wine industry,” which he said is forthcoming from KosherWine.com.

“I’d love to do a ‘deep dive’ into a specific varietal or region, or a specific category, and really get into the nittygritty details,” du Plessis shared. “I just want people to leave feeling like they know a lot more about that specific topic, but not necessarily having to be experts on it.”

Riven confirmed this rollout, explaining that it will require a minimal commitment from enrollees—just one or two nights as opposed to a six-week course, which is the standard in the Kosher Wine Academy.

“My ultimate goal is not to make someone an overall expert … it’s to make someone more confident when they go to

KosherWine.com and look at the 1,200 different SKUs,” said du Plessis of the Kosher Wine Academy offerings. “It’s to help someone know what they’re looking for and ensure they’re not intimidated by it.”

“I’m very grateful to KosherWine. com for introducing these professionallevel courses and making them available to us,” said Kratz. “I do not think that we would have been able to do this without them. I think that not only my magazine, but my wine store, my table and kosher winemakers worldwide will benefit from these kinds of educational advancements.”

The rapid expansion of kosher wine education is a welcome benefit of the growth of the kosher wine market, with

myriad new wines for consumers to try and appreciate. “It’s a great time to be a kosher wine consumer,” said Riven. “There are fantastic wines out there, and there are also a lot of new wines emerging from various regions, and in different styles that have never been made kosher.”

Even without the extensive kosher wine background, Youmans had a similar prediction. “My sense is that you’ll see more and more kosher wines within categories that aren’t available now,” he said. “You’ll see them soon—it’s a pretty vibrant, thriving market. Of course, it’s small, but my sense is that kosher consumers don’t mind paying more money for these wines, especially the good ones.”

Du Plessis shared an anecdote that reflected both Riven’s and Youmans’ prediction. “At the end of our Academy 202 class, I had someone thank me for introducing them to a $100 bottle of Champagne. He told me that despite the fact that he is now spending more on wine than he used to, I had given him the chance to really appreciate and understand what’s so great about it. I’m not saying you really need to spend that much … but for someone who can feel confident about spending a bit more on a product they really love and enjoy, that’s an amazing thing.”

The creation of our third annual Jewish Link Wine Guide has solidified a number of goals we set for ourselves when we launched during the pandemic in 2021. That first year our magazine was a scant 56 pages and many of our tastings were done outside in “socially distant” conditions. While this memory is thankfully beginning to fade, we are now thrilled that the 80-page magazine we created last year has been matched in page numbers again this year, with more advertisers, more wines, more articles augmented by the benefit of travel and ever-more complexity and depth in all we present.

This year, we were met with 660+ bottles as entries in our ranked tastings, and we made special efforts this year to highlight wines that are unique in the kosher world, both for those who wish to move beyond a basic cab or refreshing chardonnay and to thank those who make niche wines available for the kosher marketplace. While these may not be wines from far-flung corners of the world, they are few and far between in the kosher world; even if there are 1500 Gavi di Gavis made in Italy, there’s only one available kosher. We’ve continued to engineer our rankings

and sought to improve our top 10 varietal lists, including “best worldwide lists” for cabernet, merlot, chardonnay, sauvignon blanc, “Israeli blends” and others. We hope you enjoy these lists and find them useful as you shop for Pesach and throughout the year.

As always, our process of wine tastings was blind; meaning every bottle we ranked was covered and numbered so its label was not visible to the judges. The goal of blind tastings is for our judges to not be swayed in any way by their personal views on brands they have tried previously, or on any other factor other than the liquid in the glass.

We consider it an advantage that our judges' different palates and ranges of expertise reflect what the customer will experience when they pop and pour a bottle of wine.

We would also note that our lists cannot be fully considered exhaustive because we simply do not receive all wines available, for a variety of reasons. We also are unable to decant or allow wines significant time to "open" before tasting, so that should be taken into consideration.

The judges ranked their wines on a personally calibrated 100 point scale,

which they initially developed together before the tastings for the first magazine. We are exceedingly grateful and fortunate to have had all five of our founding judges return to taste for us for the third year in a row. Yossie Horwitz, Jeff Katz, Greg Raykher, Daphna Roth and Yeruchum Rosenberg share a passion for supporting the kosher wine industry as a whole. We continue to grow and learn about how to improve our blind tastings. We are grateful our efforts in previous years have been well-received and as we conclude our preparations this year, it is with a strong sense that we continue to toil toward something important. As we celebrate the brands which grace our Shabbat tables every week, we continue to see the importance of supporting the innovators and hard workers behind these brands. Every bottle of kosher wine represents an incredible amount of work on behalf of the consumer, and we could not be more grateful to celebrate and recommend so many within this beautiful community.

With best wishes for a Chag

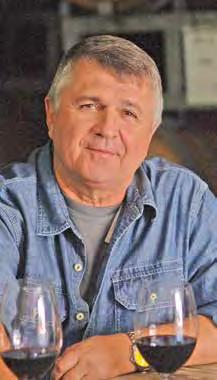

Kasher V’Sameach, Elizabeth KratzGrowing up in a tee-totaling household in Jerusalem, Yossie Horwitz didn’t have much early exposure to wine. By the time he was 30 and living in New York City, he was sharing his wine recommendations in his “Yossie’s Corkboard” blog, which goes out to more than 11,000 subscribers around the world. Tasting more than 4,000 different kosher wines each year keeps this deal-making attorney-by day quite busy. Sign up at yossiescorkboard.com and follow on instagram @yossies_corkboard.

In addition to serving as a founding judge and contributor for The Jewish Link Wine Guide, Yossie is the founder of the Rosh Chodesh Club concept.

Greg Raykher has been interested in tasting, collecting and learning about wine for over 20 years. He met some of his closest friends through the old Daniel Rogov chat group. Greg loves following the Israeli wine industry, and still remembers how excited he was when Castel went kosher in 2002, Bazelet Hagolan in 2004, Flam and Tulip in 2010, and Pelter opened Matar in 2012. When not learning about wine, Greg works in finance, with a focus on zero-carbon renewable energy projects. He lives in Teaneck with his children, and shares his love of wine exploration with his wife Daphna, a fellow judge on The Jewish Link panel. Last year, Greg received the Wine Spirits and Education Trust (WSET) Level 2 Award in Wines, passing the exam with distinction. He is a WSET Level 3 candidate.

Jeff Katz has been collecting, tasting and sharing alcohol with friends for 20 years. With an original interest in mixology and spirits, Jeff’s appreciation for wine evolved 10 years ago when his wife handed him a glass of Russian River Chardonnay. Since then, Jeff has become a member of multiple kosher wine clubs and has made good friends with many oenophiles. Jeff enjoys speaking with winemakers and hearing about their journeys which led them to where they are today. When not entertaining friends and family, Jeff works in global supply chain and customs management and lives in New Jersey with his amazing wife Eva and two beautiful daughters.

Daphna Roth has been tasting and enjoying wine for over 30 years. She first introduced her husband, Greg, to wine with a gift of the “Wine For Dummies” book. They have been exploring exciting kosher wines together ever since. Little did she know that their wine journey would include being a judge for The Jewish Link. Daphna works as an adult neuropsychologist, specializing in evaluations, in private practice in Teaneck.

Yeruchum Rosenberg is a wine enthusiast who spends his days in the world of technology and finance. He has been involved in the kosher wine scene for over 20 years. He loves family, friends, food and wine—preferably together. He enjoys cooking and frequenting Rosh Chodesh clubs. He lives in Teaneck with his wife, Michal, and their four kids.

Elizabeth Kratz is associate publisher and editor of The Jewish Link, and founding editor of The Jewish Link Wine Guide. Last year, Elizabeth received the Wine Spirits and Education Trust (WSET) Level 2 Award in Wines, passing with merit. She is a WSET Level 3 candidate.

Michal Rosenberg is associate editor at The Jewish Link and managing and production editor of The Jewish Link Wine Guide. Her husband Yeruchum first introduced her to wine 20 years ago and she’s joined him on his wine journey ever since. She’s learned a lot over the years, but still lets him pick out the bottles they drink.

Joshua E. London has been drinking, writing, consulting and speaking professionally about kosher wines and spirits for well over 20 years. For over a dozen years Josh wrote a popular weekly column on kosher wines and spirits that appeared in several Jewish publications, and his writing has appeared in a wide variety of both Jewish and non-Jewish print and online media. In addition to writing for the Jewish Link Wine Guide, Josh has once again joined us as a consulting editor. When not focused on wine and spirits, Josh is the CEO of the Anglo-Israel Association which is focused on advancing the UK-Israel relationship, and promoting education about Israel.

Dr. Kenneth Friedman is a Baltimore-based kosher wine aficionado/connoisseur. He produces and consults on unique food and wine tastings, utilizing his years of experience to create memorable, exciting events. He maintains a column on kosher wine, food and spirits and leads educational wine tastings on Instagram @kosherwinetastings. Last year, Kenny received the Wine Spirits and Education Trust (WSET) Level 2 Award in Wines, passing with merit. He is a WSET Level 3 candidate.

Gamliel Kronemer has been writing for more than 15 years about kosher wine, spirits, cocktails and food in a number of Jewish newspapers and magazines, including The Jewish Link. In 2005, when Gamliel started writing regularly on the subject, he recalled that “back then, most newspapers wrote about kosher wine at most twice a year, with headlines like ‘Kosher Wine: It’s Not Your Mama’s Manischewitz Anymore.’ Watching the kosher wine world blossom has been utterly amazing, and I feel fortunate to have had a front row seat.” Gamliel lives with his wife, Jessica, in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Delight in these easy drinking, food friendly wines that don't break the bank.

Cabernet Sauvignon

Jermak Cabernet Sauvignon

Ya'ar Levanon Cabernet

Editor's note: Since there will be few roses available in 2023 from Israel due to shemitah, we wanted to highlight the rose wines from chutz l'aretz for you to consider for this upcoming chag.

Here are our favorites.

By Jewish Link Wine Guide Staff

By Jewish Link Wine Guide Staff

During our tasting of hundreds of bottles of wine in the course of the making of The Jewish Link Wine Guide, some wineries consistently appeared throughout our rankings, pleasing our palates and delivering a superior experience in the glass, in multiple categories. The designation of five Wineries of the Year honors the passion of the owners, winemakers and staff behind these consistent

winners, as well as their consistency in placement in multiple rankings categories. We asked each winemaker what their focus is, what they see as their winery’s unique vision or contribution, and what we can expect from them going forward. This year, we identified each establishment’s wines as featured in our lists, so that you can find them easily at your local wine store or online.

Yaffo Winery is located in the famed Ella Valley, sometimes referred to as the “Israeli Tuscany” region, recognized for its quality vines. For Moshe and Anne Marie Celniker, the boutique winery is their dream come true. They focus on the quality of the grape throughout the growing process and produce a variety of wines from cabernet sauvignon to merlot, shiraz and cabernet franc.

When they first started making wine out of their home, the Celnikers produced 5,000 bottles. Today, with the addition of their son Stephan as chief winemaker, production is up to 70,000 bottles a year. The winery has a “new world” outlook, leaning toward friendly, approachable wines. Avremi Burstein, the manager and kosher supervisor, works alongside Stephan and is a key piece of the winemaking team.

Psagot Winery, located in Sha’ar Binyamin in the Jerusalem mountains, includes a wine production plant and an impressive visitors center. Since its first harvest in 2003, which produced 3,000 bottles, the winery has grown tremendously, estimating a production of 500,000 bottles from the last harvest in 2022, and 700,000 bottles from the haul in 2023.

The “combination of a family winery with qualities of a boutique” creates a unique appreciation for these less commercialized wines. Anne’s passion, Moshe’s practicality and Stephan’s education—along with a hyper-focus on quality—are the foundation for each Yaffo wine in their portfolio.

Looking to the future, Moshe plans to move to a bigger facility, “where we can double our production yet continue creating top-quality wines,” while adhering to their family foundations.

This is the second year that Yaffo has attained the distinction of Winery of the Year, because of their solid rankings across multiple Jewish Link Wine Guide categories. The Yaffo Image Red 2019 ranked in the Top 25 Red Wines between $25 and $50. The Yaffo Cabernet Sauvignon 2019 and Yaffo Carignan 2020 both ranked in the Top 25 Red Wines under $25. The Yaffo Image White Chardonnay 2020 also ranked in the Top 25 White Wines between $25 and $50, and Yaffo White 2021 ranked in the top 25 White Wines under $25.

Psagot’s chief winemaker Sam Saroka emphasized the team effort required to create the finished product. The winemaker brings experience, vision and technical expertise and is supported by the operations manager, who provides the manpower required to carry the vision through. And of course, “none of this could happen without the support of the owners of the company, Yaakov and Naama Berg,” Soroka said.

Psagot is well known for its historical presence, its vineyards home to where wine was made during the second Temple period in Jerusalem. That history is carried through in the labeling, as most Psagot wines bear a replica of an ancient coin dated back to the Great Revolt 66-73 CE that was found with the inscription “For Freedom of Zion” in an excavated cave near the vineyards. “The terroir of the region highlights the quality and consistency of our wines,” Saroka said.

The team at Psagot is committed to continuing its tradition of “connecting and maximizing extraction of high-quality terroir fruit, professional work, traditional methods and advanced equipment in order to create wines that reflect an experience that will be deeply remembered as our story from the biblical land of Israel.”

Psagot’s consistency of performance between our widest possible range of categories (both above $50 and below $25) is what led to its distinction as Winery of the Year. Psagot Homeland 2020 was the No. 2 wine in the Top 25 Red Wines above $50. Psagot Peak 2020 also ranked in the same category. Psagot Chardonnay 2021 ranked in the Top 25 Whites between $25 and $50, and the Psagot Sinai (White) 2021 ranked in the Top 25 White Wines under $25.

Lueria Winery is a family winery borne from storied vineyards in Upper Galilee, near Mount Meron planted by Yosef Sayada. Recognizing the unique quality of these vines, Yosef’s son, Gidi, started the winery in 2008, producing 5,000 bottles. The winery now produces 150,000 bottles annually.

Lueria Winery is very much a family business, with the family living about a mile from the vineyards, which enables them to control every detail in the fields and be very hands-on.

Eli Shiran, founder of Shiran Winery, works mostly by himself out of a warehouse in Kiryat Arbeh. His retirement hobby morphed into a successful microwinery that has grown consistently since its inception. “I produce around 10,000 bottles a year. We began with 600 bottles. In the coming season, we will be producing around 12-14,000 bottles.” said Shiran.

Shiran approaches winemaking as a partnership, and his task is to realize the potential of God’s creation: “I believe that a winemaker's primary task is to maximize the potential God gives us in the vines, so the most industrious role is that of the vintner as the extended arm of God’s work. The vintner ensures we have the best possible grapes. Once the grapes arrive at the winery, our task is to best realize the potential. I’m mainly a one-man show, with some help from temporary workers.”

Shiran Winery is “well known for its unique and special blends that are not found in any other winery,” the winemaker said. “We combine varietals that originate from different parts of the world. I would say that our white wines have put us on the map of high-quality wines.”

As for the future, Shiran looks to keep making high-quality, unique wines that appeal to the consumer. “Our vision is to continue creating imaginative, creative and unique blends that express different parts of my personality. I believe that my way of communicating with my clientele is through the wine they drink!”

As the vintner, Yosef ensures that the winery has the best grapes year after year. Gidi, the winemaker, actually produces the wine and works hand-in-hand with his father. Yosef’s sister, Malka, also works at the winery, along with more family members.

“The whole system works like a machine, where every screw is important and every worker in the system is significant to the winery,” shared Gidi. Lueria is best known as being “a winery that grows its own grapes, controls the production process from growing the grapes and until bottling,” he said.

Luria is “currently in the midst of implementing a new vision: building a new winery [in the Dalton industrial zone] which will include an event complex, accommodation for individuals and groups, along with tours of the vineyard. God willing, by this summer we will finish the construction,” Gidi said.

The Jewish Link Wine Guide has never had a single winery achieve four rankings in a single list, but the Lueria Roussanne 2020 was the No. 2 wine in the Top 25 White Wines under $25, followed closely by the Lueria Unoaked Chardonnay 2021 at No. 3. The Lueria Gewürztraminer 2020 also ranked in the same list, as did the Lueria Pinot Grigio 2021. Congrats to Lueria on its stellar performance and its distinction as Winery of the Year.

The relative size of Shiran made its rankings in four Jewish Link Wine Guide Top 25 lists all the more impressive. Shiran’s Riesling 2021 and Unoaked Chardonnay 2021 both ranked in the top 25 lists for mid-priced white wines. Shiran’s The Conductor 2019 ranked No. 2 of the top 25 mid-priced reds, one of the most competitive categories in our rankings. Shiran’s The Trio 2019 also ranked in the same category.

At Tabor Winery, located in the Upper Galilee, the focus is on the vineyard and maintaining its natural and ecological resources. Established in 1999, Tabor winemaking team’s creativity and meticulousness combined to spur its growth as one of Israel’s well-known wineries. With access to vines in multiple regions in Israel, the winery produces many different varieties in its state-of-the-art wine portfolio. Its first harvest in 2000 produced 250,000 bottles, and these days the winery produces 1.8 million bottles.

Herzog Wine Cellars is a family-owned winery going back nine generations. Beginning in Europe and continuing today in the Napa Valley and other regions of Northern, central and Southern California, the winery’s state-of-the-art facility was carefully designed to house both boutique and commercial winemaking projects. Known for its premium-quality California winemaking, Herzog Wine Cellars prides itself in creating unforgettable experiences for customers, which includes an elaborate tasting room and high-end restaurant in Oxnard.

When the winery opened in 1985, it had four labels and produced 20 barrels of wine. Today, Herzog Wine Cellars offers over 50 different labels, with some of their reserve wines at 5,000 cases. Boutique wine cases run as low as 200 cases.

“The Tabor Winery is keen on team spirit, therefore all of our people are crucial players for the success of the winery: wine growers, winemakers, viticulture, production, operation, marketing, finance and visitor center,” Tabor winemaker Arie Nesher shared. “Of course the most important people are our consumers. Without them the job could not get done.”

The team at Tabor listens to the land and makes the most of what it has to offer, explained Nesher: “The Tabor Winery is best known for excelling in rosé and white wines, which are very compelling to the Mediterranean climate, culture and food … We are also very proud of our ecological revolution in the vineyards.”

Looking ahead, Tabor Winery will continue its path at the forefront of the new era of Israeli wine revolution, “creating wines that are unique and outstanding, combining tradition and innovation; elegant and complex, yet very approachable.” Nesher said.

Tabor’s ability to produce ranked wines both at an aspirational level and also at an affordable price point is what brings it the distinction of winery of the year. Tabor’s affordable Mount Tabor Chardonnay 2021 and Adama Sauvignon Blanc 2021 both ranked in the Top 25 list for white wines under $25. Tabor Adama Cabernet Sauvignon ranked No. 2 in the Top 25 list of red wines under $25. Finally, elegant Tabor Malkiya 2018 ($70) also ranked in the Top 25 list for red wines above $50.

The winery runs as a team, with each member a key part of the process, explained Joseph Herzog, VP of operations. “From our winemakers to our cellar crew to our operations teams—we see each crew member as vital to the success of the winery. Many have been a part of our winery family for over 20 harvests. That time has taught the team what it takes to make great wine, and illustrates their commitment to quality winemaking.”

Herzog’s vision for the future is simple: "Let the grapes speak for themselves.’ Great grapes make great wine. Each grape has a story to tell, and we believe truly great winemaking gives language to that story.”

While Herzog is certainly a household name among kosher wine lovers, it attained the distinction of Winery of the Year by virtue of having a fascinating mix of four of its wines solidly ranked in top 25 lists. The Herzog Special Reserve Quartet 2020 ranked in the Top 25 of Red Wines between $25 and $50. The Herzog Lineage Cabernet Sauvignon ranked in the Top 25 Red Wines under $25. The Herzog Lineage Chardonnay 2020 ranked in the Top 25 White Wines Under $25, and the Baron Herzog Chardonnay 2021 (at $12) also ranked in the same list. The Herzog Lineage

Over the past three months, during our tasting of 660plus wines and the editorial work of researching, interviewing and writing about the winemakers and professionals who make the kosher wine in our bottles, many of them stood out to our team in a particular way. While it was a prerequisite that all of the wineries or wines they represent performed well in our tastings, it was the passion and thirst for innovation of these five individuals that brought

additional merit and strength to the kosher wine industry over the past year, and in fact have changed it for the better.

Whether it is in research and development of native Israeli varieties and teaching through learning (Dr. Shivi Drori of Gvaot Winery), a Renaissance perspective (Jeff Morgan of Covenant Winery and Covenant Israel), a historic and Torah-inspired approach to working the land of Israel (Ya’acov Ben-Dor of Yatir Winery), a passion to bring local wines from the

mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. to the kosher market (Kevin Danna of Binah Winery), a 30-year advocate to make Israeli wines and spirits equal to every other country’s on the world stage (Alex Haruni of Dalton Winery) or a team working to find and distribute the best Israeli, American and Italian kosher wines of the world to major markets (Larissa and Ami Nahari of The River Wine), we were simply blown away by their drive, innovation and expertise. Mazel tov!

Dalton Winery, Upper Galilee

Bringing Israeli Wine to the World Stage CEO Alex Haruni started Dalton Winery in 1995 with his father Mat to explore the potential of the Upper Galilee region and highlight its natural gifts. Dalton’s initial production in the 1990s was around 20,000 bottles. Over the years the winery grew and became synonymous with quality and consistency. “When we began exporting to the U.S. we were a much smaller winery [than we are now], producing about 200,000 bottles a year,” remembered Haruni. Since then the winery has grown to over a million bottles and their sales to the U.S. have grown commensurately. “Managing a winery of this size and looking after its export sales takes up all the time I have,” said Haruni.

The Dalton brand is known for its consistency and quality, and more

recently, innovation. You can pick up a bottle of Dalton wine at any price point and it will be of consistent quality throughout the vintage. But their consistency doesn’t get in the way of new ideas. “We are constantly innovating in the cellar, looking to bring new wines and new winemaking techniques to the market, be they varietals such as zuriman, storage innovations such as clay amphorae, new styles like the pét-nat or innovative blends that move away

U.S. to Israel, Europe, Asia, Canada, Mexico and even in Tokyo and Taiwan.

from the traditional cabernet-based blends,” Haruni shared. Dalton has also recently begun building a distillery and as one of its first products, has released an aromatic vermouth, one of only a few available in the kosher marketplace.

The overarching goal at Dalton is not to be thought of as a kosher wine. Though they make wine in the land of Israel, combining its natural resources of the soil, the sun and the fruit into their finished product, kashrut does not necessarily define them as winemakers, as important as it is. “What I truly want,” said Haruni, “is for Israeli wines to find their own voice on the international wine scene and not to be derailed by the kosher discussion.”

Dalton is mindful of the next generation of wine consumers and wants to create products that will appeal to that demographic. Haruni stressed that the winemaking team at Dalton is “always looking for new methods, tastes and ideas that will pique the curiosity of, and resonate with, new wine drinkers.”

Covenant Winery, California and Israel

The Renaissance Winemaker

In 2003, Jeff Morgan founded Covenant Winery in California’s Napa Valley, where he and his late business partner, Leslie Rudd, sought to create a new high-quality paradigm for kosher wine.

A visit to Israel in 2011 prompted Morgan to make his first wine in Israel—a syrah—in 2013. Covenant’s wines are now sold worldwide, from the

A writer and musician as well as a winemaker, saxophonist Morgan was the West Coast editor of Wine Spectator magazine from 1992 to 2000. He has also written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Food & Wine, Wine Enthusiast, Elle and—with his wife, Jodie—has penned 10 books on food and wine; the latest is “The Covenant Kitchen: Food and Wine for the New Jewish Table” (Schocken Books).

Morgan looks back to Covenant’s beginnings: “My first vintage of Covenant was produced in 2003—only 500 cases of Napa Valley cabernet sauvignon, which we released in 2005. Today we produce some 8,000 cases of 20 different wines at our Berkeley, California winery.”

Starting in 2013, Morgan began to make wine in Israel. Prior to COVID (and shemitah) the winery produced

up to roughly 2,000 cases—five different wines—annually in Israel, with two thirds of that production exported.

He explains Covenant’s unique situation in the kosher wine scene. “Covenant is among those wineries at the forefront of kosher wine’s quality renaissance,” he said. His experience as a wine reviewer for Wine Spectator gave him “a broad-based perspective, and with the assistance of many fine winemakers worldwide, I have learned techniques that continue to make Covenant a serious contender in the quality wine world.”

Morgan’s goal at Covenant is to make kosher wines that are as good as his favorite wines from around the world. He feels that if kosher winemakers ever hope to be taken seriously by the secular wine world, they need to make sure that their fine wines are also available, enjoyed and recognized outside the Jewish market. According to Morgan, “This may be our greatest challenge.”

The Mid-Atlantic Kosher Winemaker

Kevin Danna established Pennsylvania’s first kosher winery during 2019 at a small vineyard in Easton, Pennsylvania, before relocating a year later to Allentown, Pennsylvania, where he resides with his family.

Danna’s prior career in architectural lighting design gave him an elite design philosophy, which continues to shape his approach to winemaking as an art and a science.

Binah Winery is a micro-winery, producing around 1,000 cases per year. Danna began with 10 types of wine and has already expanded to 16. He focuses on excellence and superiority in white wine, producing wines from grapes in the cool-climate region of the mid-Atlantic, whose quality is consistent year-to-year.

“I think Binah is getting a reputation for being a hidden gem. But yeah, ask

The River Wine

The Industry Disruptors

Larissa and Ami charged into the world of kosher wine 13 years ago looking to shake things up when they started The River Wine. Fast forward to 2023: The business, and life, partners have succeeded in that mission of innovation, making creative choices and expanding their enterprise on the way.