24 minute read

The myth of Carrying Capacity for Tourism

The myth of Carrying Capacity for Tourism

Recreational carrying capacity, ecological carrying capacity, tourist carrying capacity, or just carrying capacity. According to Sayre (2008) in his Genesis, History, and Limits of Carrying Capacity, this concept can be understood in four distinct definitions:

Advertisement

1) As a mechanical or engineering attribute of manufactured objects or systems, dating from around 1840, in the context of international shipping which, to some extent, can be measured in fixed values and numbers relatively objectively; that is, how much cargo does a ship bear? For example.

2) As an attribute of living organisms and natural systems, dating from the 1870s and more fully developed in livestock management and hunting in the early twentieth century, which gave or governs the concept used for recreational activities in the national parks of the United States and which permeated other countries; as an example How many cows can feed a hectare of pasture?

3) Like K, the natural limit of population increase in organisms, used by population biologists since the mid-twentieth century, used to exemplify a system where the number of individuals is large enough to pressure existing natural resources and as the population grows, in a direct linear relationship, these resources are beginning to run out, slowing the growth rate. As an example, how much will a population of bacteria grow until they run out of space or food and begin to no longer grow or "decrease"? The maximum limit where that happens is known as K.

4) As the number of human beings that the earth can support, employed by neo-Malthusians, also since the middle of the last century. A theory that is rather a myth where it is said that the planet only has the capacity to sustain a limit number of human beings.

To understand how the concept of Load Capacity (CC) ended up being used to have a practically magical number of tourists who can visit a national park or protected natural area or boats in a body of water, with the aim of recreational use, we must review a little history. Leaving aside the first concept, for obvious reasons, an opportunistic hodgepodge was given to

combine the remaining three definitions to complete the discourse of carrying capacity so cheerfully handled by the triad.

In addition to the concept in engineering, which was the most widely used since ancient times, the concept of population or environmental carrying capacity was initially developed by livestock and wildlife managers in the United States around the 1880s. This methodology was created to try to determine the limits of the plant ecosystem where an animal population of herbivores could develop and survive, given the ranching conditions. This mode of carrying capacity comes from the idea that an organism can only exist within a limited range of physical conditions. In the case of herbivores, plants and animals require a minimal amount of energy and nutrients, and could only withstand certain concentrations of chemicals. The availability of adequate living conditions determined, according to several authors, the number of organisms that could exist in an environment. At the beginning of this stage of the evolution of carrying capacity for livestock and wild ranching, it was thought to be a simple matter to calculate, but the model began to get complicated as it became understood that there were many other factors that intervened in the ability to sustain a population of animals in a given area. Factors that were directly related to the species or species managed, biophysical conditions, nutritional requirements according to age or gender of the specimens, type of fencing, availability of other resources such as water, or nutrients other than grass or plant species found at the site, climatic conditions, intra or interspecific competition, among others. Reaching a point where, as they described, it was practically impossible to determine a single carrying capacity for a site (even talking about paddocks and livestock), given that the development of a population was subject to diverse environmental conditions, which could be caused by the specimens themselves, by external factors or by environmental factors or phenomena that did not depend directly on the resource-population interaction. Some researchers concluded that the carrying capacity could only be calculated for deterministic and slightly variable systems, and only for cases where the behavior and ecological relationships of the species changed slowly on the human time scale, and it was not at all advisable to use it for stochastic systems, those where there are many variations of the environmental system (most environmental systems are of this type), and due to the nonlinear nature of many cause-and-effect relationships

and lack of knowledge (data, information, understanding, experience), all of which introduced a great deal of uncertainty into the calculations. This severe limitation in the predictive character has earned the capacity of very severe critical load in the last three decades; Price (1999) exposes not only the failures of trying to bring a laboratory population growth model to the field, and the pernicious way in which scientists have ignored or taken assumptions for granted, forcing their results to test this model in a tendentious way, to expose "... We conclude that the concept of carrying capacity is seriously flawed. In fact, it may be nothing more than a self-validating belief…”. Other authors raised additional arguments questioning the practical usefulness of carrying capacity and its scientific foundations, raising questions about the validity to manage not only the management of herbivores from this perspective, but beyond, the uses that were subsequently given to it for economic activities where human activities and populations interact in natural sites.

Like many concepts and models of management and conservation that we use today, the carrying capacity came imported, in this case from the national parks of the United States. The fact that the origin of the use of the concept of carrying capacity to sustain animal populations in well-defined areas began to be used in protected areas and parks in the United States almost 100 years ago should be enough to give us an idea of how inapplicable the model is, in our context.

When one speaks of the establishment of the first American "modern" protected natural area in 1872, Yellowstone National Park, and in 1890 of Yosemite National Park, one tends to ignore the fact that the U.S. government violently expelled the Native Americans who lived and depended on natural resources in those areas (Burnham, 2000) Poirier & Ostrgren (2002), cite: “…These actions were influenced both by the views of the parks and pristine "wilderness areas", devoid of occupation and human use. And for the interests of powerful lobbies such as the railway industry, which wanted to develop parks for tourism; indigenous peoples were seen as incompatible with both interests…” The American model of parks was created with the expropriation, bordering on dispossession, of the lands and territories of indigenous peoples and local communities where lands, especially common lands, were claimed for the

state, without even considering the pre-existing historical, legal rights of ownership and use under traditional historical tenure, and with the purchase of private property through the Land and Water Conservation Fund. To date 84 million acres (approximately 34 million hectares) are owned by the state and only a little less than two million acres (809,371 hectares) remain under private (non-communal) ownership. That is, the system of protected natural areas of the United States is integrated into 97.6% of federal properties and 2.3% by private properties in the form of "inholdings" (private properties within national parks) waiting to be acquired by the Land and Conservation Fund. No communal properties. It is a very complex system that includes: 63 National Parks, 129 National Monuments (managed by the SPN and other agencies), 19 National Reserves (more similar to our reserves), 61 National Historic Parks, 87 National Historic Sites (76 managed by the SPN and 11 are affiliated areas), 2 Authorized National Historic Sites (still pending purchase of the property), 1 International Historic Site, 4 Battlefield National Parks, 11 National Military Parks, 21 National Battlefields, 34 National Memorials, 25 National Recreation Areas, 10 National Coasts, 4 National Lake Coasts, 15 National Rivers and Wild and Scenic Rivers, 3 Mixed National Reserves, 10 National Roads, 23 National Trails, 15 National Cemeteries, 55 National Heritage Areas and 16 National Park Service Units.

Management is under the supervision of the National Park Service, and other government agencies, but the local management of most services is in the form of concessions. There are currently more than 500 concessions (franchise type) to manage visitor services in national parks and charge access fees, coordinated by the Commercial Collection Services division of the National Park Service. The gross income is one trillion dollars. Dealerships employ more than 25,000 employees in peak seasons. Although the record is more than 575 contracts, only 60 contracts generate more than 85% of revenue ($850 million). The franchise is 5% of the contracts. The system receives more than 292 million recreational visitors who spend $15.7 billion in Gateway communities located an average of 60 miles (96.5 km) from parks (Josephson, 2021). There are no communities within the parks or within 96.5 kilometers away.

The Organic Act that gave rise to the National Park Service establishes the objective of its creation, which states: "the Service thus established will promote and regulate the use of federal areas known as national parks, monuments and reserves ... by means and measures consistent with the fundamental purpose of such parks, monuments and reserves, the purpose of which is to preserve the landscape and the natural and historical objects and wildlife in them and to provide for the enjoyment thereof in such a way and by the means that leave them intact for the enjoyment of future generations." (NPS, 2018). It was logical that they would look for a model to determine the maximum number of people making use of the areas, if it was one of their objectives to serve as "enjoyment" areas. In this sense, between 2008 and 2019 the U.S. park system received 3,584.7 million visitors, at an average of 298.725 million annual visitors (Statista, 2021). Another statistic estimates that from 1904 to 2020, the U.S. park system has received 14,891,410,480 visitors (nearly fifteen billion visitors in 116 years) (NPS, 2021) mostly local or domestic tourism. By the time the American model of parks permeated the rest of the world, around the 50s – with the boom of local visits to parks within the same North American territory, the overlap of those models of protection of sites that had among their objectives the recreational use, in federal territories, came into conflict with the reality of other countries, such as tropical developing countries, whose forests, jungles, wetlands and other ecosystems were part of the social communal property and in them coexisted indigenous populations and other traditional groups, which developed forms of communal appropriation of natural spaces and resources for their subsistence.

These indigenous and rural communities had a close relationship with species and spaces, integrating them as part of their cultural heritage, their history and the traditional use of them, for which they had also developed models of protection and conservation and even improvement of biodiversity in their territories, for generations. The local cultural had been carrying out a respectful and integral management that allowed the persistence of spaces, ecosystems and bodies of water that, in the eyes of third parties who recently arrived at the sites, seemed to have remained untouched or virgin since always. This mistaken and simplistic idea that indigenous or rural territories managed by generations were "untouched"

spaces, motivated, without prior knowledge, promoting groups outside the communities, mainly academics and NGOs, to propose restrictive schemes to maintain these "wild areas" "pristine" to turn them into protected natural areas as if they were public goods, with their partial vision of the neomyth of "untouched wild nature" (Diegues, 2000) without taking into account that these historically community spaces had remained so because of their close relationship and the identity created with local populations. That is, because the locals had kept them. If we now make a comparison, an instance equivalent to the United States Park Service in Mexico would be a combination of the Commission of Protected Natural Areas (CONANP), the Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), the Secretary of Tourism (SECTUR), the Secretary of Commerce, the Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection (PROFEPA) and the Institute of Administration and Appraisals of National Assets (INDABIN) with a recreational approach, of conservation and surveillance, in depopulated areas of federal property and a few private areas. In contrast to how the adapted model of the United States has worked, in Mexico, for 2013 the PNA system had 25,394,779 hectares (CONANP, 2014), and continued to accumulate hectares, because in 7 years it made a huge leap, and by 2021, it had 90,830,963 hectares reported by CONANP under its administration (CONANP, 2021); less than one fifth was owned by the Nation, the rest being private or communal property; according to the 2010 Population and Housing Census, at that time there were 176 Natural Protected Areas of federal competence where 1,713,628 people lived (CONANP, 2014), most of them in indigenous and rural populations. CONANP has found itself practically since its decree and throughout its history in deplorable financial and operational conditions (Garcigalán, 2015), and the funds generated by the collection of fees for entry to the PNA, which they collect throughout the country are less than 70 million pesos per year (approximately 3.5 million dollars) (Quadri, 2014). Our NAPs have no recreational park targets and lack the franchise-like structure, infrastructure and resources or a system to actually allow them to function as recreational tourist receivers.

In contrast to the National Park Service, CONANP aims to

“…maintain the representativeness of Mexico's ecosystems and biodiversity, ensuring the provision of their environmental services through their conservation and sustainable management, promoting the development of productive activities, with criteria of inclusion and equity, that contribute to the generation of employment and the reduction of poverty in the communities that live within the NAPAs and their areas of influence. This Objective will be pursued through a series of Strategic Objectives related to the following areas: Integrated landscape management, Conservation and management of biodiversity,

Attention to the effects of climate change and reduction of GHG emissions,

Conservation economics, Strengthening of intra-sectoral strategic coordination (Integrality), Strengthening of intersectoral coordination (Transversality),

Legal framework for the conservation of natural heritage, Institutional strengthening and Communication, education, culture and social participation for conservation. (CONANP, 2021)…” It might be thought that the phrase "promoting the development of productive activities, with criteria of inclusion and equity, that contribute to the generation of employment and the reduction of poverty in the communities living within the NAPAs and their areas of influence ...", which is mentioned in the objective, could represent the basis for the promotion, administration and operation of tourism and recreation, as in the United States, but because the management unit of the NAPas belongs to the environmental sector its scope is limited to that sector and the "productive" vision is paternalistic. "Productive" funds are related to conservation activities or small grants for community groups. Due to the very characteristics and nature of the PNA system mentioned, the franchise model cannot be promoted to third parties for integral tourism management as the U.S. model, because in addition, in Mexico the territory in parks and reserves, for the most part, is communal or private property, or they are sites where economic activities of importance to the communities of the adjacent area or of influence are historically carried out, not related to tourism and that can compete for funds, spaces and recognition. So CONANP does not specify objectives for the development of recreational activities in the areas, although they try to establish strategies to promote and control tourism activities, among which it does promote the calculation of tourist load capacity.

Returning to how the concept of carrying capacity for tourism in the United States evolved, by the 1920s the concept had begun to be used to describe the relationship between livestock and their environment, then applied to wild herbivores (Leopold 1933). But, it wasn't until the 1950s that it began to be used to try to find a magic number of tourists that a reserve or national park could endure before the negative impacts, on ecosystem and wildlife, were irreversible.

To understand, how did the concept of livestock load capacity end up as the number of individuals (tourists) that an area (protected area or protected wild site) could support? one should be aware of the picture around the time when the carrying capacity of tourism in the United States began to permeate (which was later disseminated to other countries, including Mexico). This was because many of the early recreation managers in U.S. National Parks had been trained in the sciences of forestry, wildlife, and livestock management, not in recreational or tourist park management, concerns about people and their impacts were quickly described as a carrying capacity problem (referred to the use of grasslands by livestock or deer), seeking urgent solutions when facilities and resources simply could not accommodate increasing increases in demand due to design and management constraints. This decade (1950) also uncovered foundational struggles in the National Park Service. As the administration struggled to meet the growing demand for tourists, it had to deal with a philosophical question about the very nature of its lands. That question is still relevant today: do national parks exist to preserve nature, or to make that nature accessible to all? And if the service can only meet one of these two goals, which one does it choose? So researchers and managers of these areas, which came from decades of wildlife management and not directly from recreation, implicitly assumed that levels of use and impacts were interrelated as was the case with livestock or wildlife in a grassland, thus presupposing that the site possessed an inherent or specific carrying capacity.

In tourist use this would suggest that as the impacts slowly increased, due to tourist-recreational use they would reach a point where the conditions of the site would deteriorate rapidly. The point just before reaching the point of no return, they theorized, must be the carrying capacity for tourism and recreation.

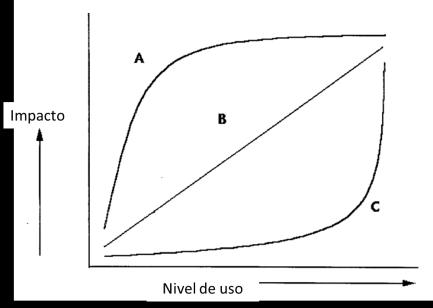

In the 1960s and early 1970s, it was the scientists and especially the natural resource managers of the U.S. Forest Service, some of whom had become managers of recreational areas, who promoted research to identify the carrying capacities for recreation in the parks and sites under their responsibility. At that point it was recognized that most of the standards for space occupancy had been developed from intuitive judgments and trial-anderror experiences, rather than quantitative evidence of controlled research. That is, the load capacity standards were built without scientific evidence. In order to understand the reasoning of Carrying Capacity, McCool & Lime (2001) exemplify three variants of the potential relationships between the level of use and the amount of biophysical and social impact resulting.

• Curve A represents a situation where impacts increase rapidly with small amounts of usage, and then as site usage increases, the level of impact decreases or stabilizes.

• Curve B represents a situation in which impacts are a linear function of the level of use. In this situation, as the use of the site increases, the impacts increase. This was the relationship that researchers of the time assumed existed in the territories of the parks that were used for recreational activities.

• The C Curve represents a situation where the level of impact increases gradually, as the level of use increases and then, after a certain point, begins to grow rapidly. This curve exemplified the intrinsic carrying capacity of the ecosystem..

Potential relationships between the level of use and the amount of biophysical and social impact resulting. Author Translation, Source: McCool, S. F. & David W. Lime (2001) Tourism Carrying Capacity: Tempting Fantasy or Useful Reality?, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 9:5, 372-388.

Lime and Stankey (1971) and even Odum himself (father of the concept of logistic population growth K – from which the third definition of carrying capacity emerged) made it clear that carrying capacity was not a space standard to define the number of units of use (people, vehicles) that could use recreational space at some point, to ensure a "satisfactory" experience by the visitor. The carrying capacity that was evaluated in national parks was the character or type of use that an area developed at a certain level can withstand over a specified time without causing excessive damage to either the physical environment or the visitor experience. It was not the ecological concept of carrying capacity. It was a multidimensional and dynamic concept, capable of being manipulated by the administration of the protected natural area, in accordance with the budgetary and resource administrative restrictions of the agency in charge. The carrying capacity defined at the time by park managers in the United States had three components that are applicable to date: 1) Management objectives, 2) Visitor attitude, and 3) Recreational impact on physical resources.

These were not independent considerations, of course, but they were interwoven and dependent on organization, planning, and operation; that is, the carrying capacity not only depended on the type of visitor and the ecosystem, but also on the objective of managing the area, the administrative

limitations, tasks and available economic resources. Now let's try to adjust this vision to the Mexican model.

Why was it important, first of all, to have a management objective for the area? Because it is necessary to know the purpose, fragility and complexity of the system in order to have an idea of the scope of the activities that may or may not be performed. It is not the same to determine the carrying capacity for a lagoon with a sport or recreational fishing objective, than for a lagoon where nautical activities of many other types are developed, and even swimming or biodiversity observation. Determining whether the site is going to be of low or high density does not only depend on the "preferences" of the tourist. "... Without defined objectives to establish trying to establish a management scheme based on the load capacity of a site is futile..." (Lime and Stanky, 1971), and more importantly, the carrying capacity is not generalizable "... you cannot assign a single capacity to an entire area…" It is tempting to use the carrying capacity politically to generate the public image that you have things under control, and obtain magic numbers as you tried to do with Bacalar and all the policies of Protected Natural Areas, tourism strategies and boat permits. In Mexico, the NAPAs do not have defined tourism objectives, and if the case uses terms such as sustainable use, which are too generalist to serve as a basis for planning a certain activity, because it leaves open the range for all sustainable use activities. As field experience grew, in the United States, the term came to be defined as the amount of recreational use allowed by the management objectives of an area. When you read this definition carefully, two things are noticed: (1) It is NOT an intrinsic or innate carrying capacity, that is: an ecosystem does not bring a labeled maximum load measure, as if it were a bucket with a maximum capacity to fill; and (2) Since it is based on use, an area can have multiple capabilities, depending on which objective or objectives are articulated in it.. The objectives of the tourist load capacity are based on the use of the site, not on any environmental concept, nor on the tastes or preferences of tourists. That is, a protected area can have a very low recreational or tourist carrying capacity if its objective (recreational or tourist) focuses on providing opportunities for solitude, for exclusivist enjoyment, of very low density, in a natural environment of pristine beauty; but it can also have a greater carrying capacity, if the objective is recreational or tourist activities that involve more

people, and where there are fewer limitations in the impacts caused by visitors. For the same area there may be multiple load capacities. But this concept does not involve the environmental unless it affects the quality of the landscape, which is the product that the tourist buys. And even more, it should not be lost sight of the fact that the development and choice of management objectives in a protected natural area is a human, social process, it is not physical, nor ecological, nor biological. That is, determining how much burden a site will bear, or how much change is acceptable, if it is subjected to a series of determined human activities (direct and indirect), is ALWAYS a human, social, informed or uninformed judgment, and supposedly based on science, but it is created, determined and sustained in the environment of political discourse and in many cases by particular interests, institutional or group. Even if there are scientists involved, who can give us information so that locally, in theory, we can assess How Much Is Too Much?, and local experts can answer that question, in the end carrying capacity is always going to be a political decision. Several authors insist that tourism carrying capacity should be seen as a comprehensive planning process, as a strategic policy instrument for the development of local models of sustainable tourism and not as a scientific measure, a unique number or a magic number. O'Reilly (1986) states that carrying capacity should be used as an indicator, as a baseline to identify critical thresholds that require attention, not as a fixed numerical limit, but as an indicator when making decisions and applying controls or regulations, at the time that is required. In the case of Bacalar, a central aspect for a definition of recreational carrying capacity would depend on the needs, values and concerns of visitors and those in charge of managing the Lagoon, reconciling the load capacity determined by APIQROO, as a concessionaire for nautical use, or that established by SEMAR as responsible for the integral management of the body of water, of CONAGUA as in charge of the sustainability and water quality of inland water bodies, but also of the Mexican Geological Survey, which knows about the geohydrological processes of the system, of the users and historical inhabitants of the lagoon who know very well what meta image they have of the body of water that generationally has been part of their life, of service providers who know how many boats can interact and why, and thus each estimates a load capacity according to their approach and vision. In this way,

carrying capacity could only be established in terms of specific management objectives, which vary widely on a case-by-case basis. Taking these options into account shifts the focus of recreational carrying capacity from asking how many vessels are too many to defining a joint vision, enriched with everyone's vision.

Now, the other issue is to implement carrying capacity policies, which is said more simply than it is in reality. It implies that an administrator or person in charge of an area must make restrictive decisions when the load capacity is about to be exceeded and this, as has been seen for the cases of the PNA of Holbox and Tulum, has not happened, with which the PNA far exceeded their tourist cargo capacity (the number of boats or authorized tourist service providers). Since when it is necessary to restrict the use or access, it will create problems of equity, because it implies that the administration or the person in charge must decide who can make use of or enter the area. This has led to the exclusion of actors, preferential treatment and corruption. Another key aspect is that, since the criteria were based on the "preferences" of tourists, it was learned over time, that visitors have multiple expectations for tourist experiences, only some of which are related to the density of use. Because the expectations of a visitor are as broad as can be the individual preferences of each one and their motivations (Maslow's pyramid). Emotions and valuation according to preferences and affections are an inseparable part of visitors' decision-making and that varies infinitely. Based on this point of view, there would be no such thing as the "average" visitor, therefore the conditions of an ideal standard experience do not exist either. This applies not only to tourists; it also applies to residents of Bacalar. A resident's perception of what the optimal ecosystem conditions should be varies depending on, for example, whether their economic activities are linked to tourism or not. It can also vary according to how much the body of water knows or not, what scale of values the body of water has in its life (which feels so affected). So how do you choose which perceptions are valid and which are not, when setting limits? If as we have already seen, the ecosystem does not have a specific tourist limit, for example. It should also be added that the impacts depend on existing policies of all kinds, existing instruments of ordering and regulation, the level of compliance of the authorities, which requires a real and efficient articulation. In