26 minute read

References

Fig. 1 Red poppies - associated with death in Turkish and Persian literature, Taj Mahal

Taj Mahal Gardens, Agra, India

Advertisement

A memorial garden

1. History and significance of the Taj Mahal and its Garden 2. Understanding the Taj Mahal Garden as a place of memorial: (a) The Char Bagh layout (b) The waterways (c) The planting elements 3. Conclusion 4. References

One of the new Seven Wonders of the World, the 1 Taj Mahal is a beautiful mausoleum comissioned by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, in memory of his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, between 1632-43.2

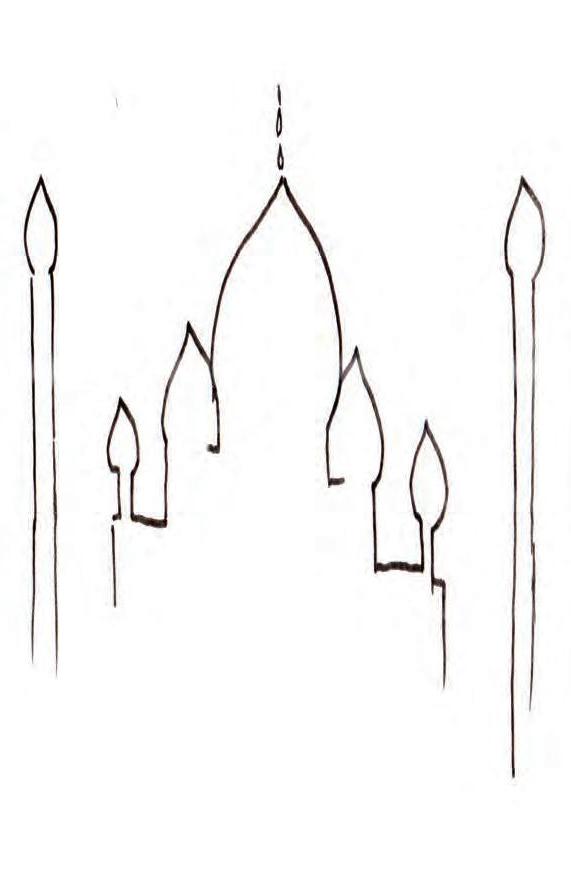

The grand mausoleum and its landscape, situated at the banks of River Yamuna (see fig. 2) serves also as a memorial to imperial Mughal power and architecture under Shah Jahan’s reign from 1628-58, its garden design style taking 3 inspiration from Persian ‘char bagh’ or four (part) gardens, Timurid building traditions and key elements of Shahjahani architecture: 4 paths - each flowerbed said

1. Geometry 2. Symmetry 3. Symbolism

While these architectural elements also worked to provide a lasting memorial to Shah Jahan’s fame as the emperor of Mughal India, this chapter will particularly analyse the form and features of the Taj Mahal gardens as a funerary memorial, a final resting place, for the Empress Mumtaz Mahal by indentifying key landscape elements

Riverfront terrace

Mausoleum

4 major divisions of the garden by the water channel

Subdivisions into 16 flowerbeds using stone-paved raised that contribute to a commemorative purpose.

to have contained 400 flowers

Central ornamental pond

Entrance Gate/darwaaza 1

3

Yamuna River

2.2. (a) The symbolism behind Char Bagh layout

The Taj Mahal’s Char Bagh (see fig. 2) alone covers an area of 90,000 sq. m out of the total 220,000 sq. m mausoleum complex. Its layout is derived from the Persian 5 concept of the Garden of Heaven, “describing paradise as a garden filled with abundant trees, flowers and plants”. 6

The layout follows the the concept of four, which is the holiest number in the Islamic religion and has been incorporated in their description of a Paradise: 7

“And for him, who fears to stand before his Lord, are two gardens. And beside them are two other gardens.” - Qur’an (Chapter 55, Verse 46 and 62)

Accordingly, the garden has been divided into four blocks with a central marble pond that serves as the focal point of the garden. Here, the style deviates from the 8 design pattern of predecessor tombs such as those of Humayun and Akbar, by placing the main pavilion not at the center, but at the end of the garden, overlooking the Yamuna river, taking advantage of the waterfront and its picturesque views. 9

Bazaar/market space

Together, these elements provide a cultural and visual reference to a beautiful Paradise for Mumtaz Mahal.

Fig. 2 Plan view of the Taj Mahal Gardens, Agra - Mughal waterfront garden

Flower beds

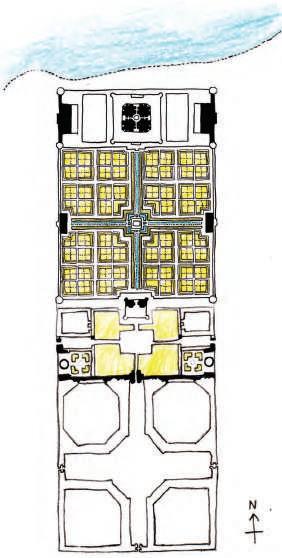

Fig. 3 Char Bagh Layout showing waterway network

Fruit-bearing trees lining the pedestrian pathways, its canopies, scent Raised marble basin studded with floral patterns - flowers a reference to the Paradise Garden

One of the four major water channels (see fig. and vivid colors providing a multi-sensorial experience

2 for reference)

Pedestrian pathway network dividing the Char Bagh garden beds

Within the engraved podium, the Central ornamental pond - The Pool of Paradise, referenced from the Qur’an This concept has attained physical form under the landscape design of the Taj Mahal Gardens, through the four water channels that divide the Char Bagh (see fig. 2 and 3). They meet at the center of 11 the channel axes at a beautiful marble ornamental pond studded with floral patterns, called ‘al-Hawd al Kawthar’, or the pool of Paradise. It reflects the Taj in its waters and accentuates the 12 holiness of the mausoleum as a resting place for the Empress.

The water network at the Taj Mahal Garden is meant to serve both, a functional and aesthetic purpose. The main source of water for the Garden is the River Yamuna (see fig. 2). Aware of the poor 13 aesthetic appearance of the grotesque pur-ramps and crude conduits, underground pipes and interconnected canals were used, with the fountain sprouts in the channels resembling the shape of the Taj minarets (see fig. 4). 14

Through these elements, the Taj Mahal Garden successfully recreates the vivid imagery of the Islamic Paradise as a beautiful Garden with pious rivers, contributing to a serene and tranquil atmosphere.

Armchair Travel Company, “Features of the Paradise Garden.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.taj-mahal.net/newtaj/textMM/GardenFeatures.html

Arunkrishnan, “Learn this not so well known fact about the Taj Mahal before your visit,” The Mughals of India, accessed October 2020, http://themughalsofindia.com/learn-this-not-so-well-known-fact-about-the-taj-mahal-befo re-your-visitlearn-this-not-so-well-known-fact-about-the-taj-mahal-before-your-visit/

Duraiswamy, Dayalan.“Taj Mahal and its unique Garden,” Archaeological Survey of India, accessed October 2020, https://www.academia.edu/13272060/Taj_Mahal_and_its_unique_Garden

Gardenvisit, “Taj Mahal.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.gardenvisit.com/history_theory/garden_landscape_design_articles/south_asi a/taj_mahal_tomb_garden#

Golombek, Lisa. “From Timur to Tivoli: Reflections on Il Giardino All’Italiana,” Muqarnas 25 (2008): 243-254. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/27811123.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ad1d02a7e1c1fa199 226d04a8afa9b26d

Google Arts and Culture, “Wander the Gardens of the Taj Mahal.” Accessed October 2020,https://artsandculture.google.com/story/wander-the-gardens-of-the-taj-mahal/EwVh iYc9WvQN3g?hl=en

Koch, Ebba. “Mughal Palace Gardens from Babur to Shah Jahan (1526-1648).” Muqarnas 14 (1997): 143-165. https://www.academia.edu/7437823/Mughal_Palace_Gardens_from_Babur_to_Shah_Jah an_1526_1648_

Koch, Ebba. “The Taj Mahal: Architecture, Symbolism and Urban Significance.” Muqarnas 22 (2005): 128-149. https://www.academia.edu/7437748/The_Taj_Mahal_Architecture_Symbolism_and_Urb an_Significance

2.2. (c) Commemorative gesture through flowers

The edges of the four water channels are lined with a row of cypress trees (see fig. 4), an ancient symbol of immortality and eternity in Persian culture. 15

The flowers like red poppies (see fig. 1) and red lilies may have also been planted in the garden beds as they were associated with death and sadness in Persian and Turkish literature. 16

Taj Minarets

Cypress tree signifying death

Perfect reflection of the Taj Mahal Framed view of the Taj Mahal using the symmetrical layout of

in the water cypress trees and water channel that are associated with death, but also with Paradise, signifying a peaceful afterlife for the Empress. Fruit-bearing trees lining pathways Flower bed

Similarly, roses, a symbol of love in Persian literature, have been planted along the pathways with other fruit-bearing Daisies in trees that signify life, providing a vivid multi-sensorial foreground experience when walking through the Gardens (see fig. 3). 17 symbolizing innocence and purityThese flowers have also been given architectural expression through engravings on the marble of the mausoleum and the podium that holds the ornamental pond (See fig. 3). Fig. 4 The Taj Mahal as seen from the Char Bagh pavilion - Paradise on Earth.

2.3. Conclusion

Fountain sprouts in the water channel - shape resembling the Taj Minarets - cohesion between architecture and landscape elements The garden was Europeanised with informal tree-planting during the nineteenth century. However, much of the original design is still retained. The harmony between 18 the Garden’s landscape design, waterways and plantations, their symbolic connotations to Islamic Paradise, combined with a rich sensorial experience, emanates peace and tranquility, and as the foreground to the Taj Mahal, paints a vivid image of Paradise on Earth (see fig. 4), thus commemorating the Empress Mumtaz Mahal’s memory at this mausoleum.

Kurian, Nimi. “Epitome of love,” The Hindu, updated October 18, 2016, https://www.thehindu.com/features/kids/Epitome-of-love/article14424002.ece

Parodi, Laura E. "'The Distilled Essence of the Timurid Spirit': Some Observations on the Taj Mahal." East and West 50, no. 1/4 (Dec 2000): 535-542. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29757466?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Private Taj Mahal Tours, “Taj Mahal Garden.” Accessed October 2020, http://privatetajmahaltours.com/about/taj-mahal-nearby-attractions/taj-mahal-garden.html

Taj Mahal, “Water devices at Taj Mahal.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.tajmahal.org.uk/water-devices.html

Wonders of the world, “Gardens of the Taj Mahal.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.wonders-of-the-world.net/Taj-Mahal/Gardens-of-the-Taj-Mahal.php

FIGURE REFERENCES

Fig. 1. Chopdekar, Manasi. Red poppies - associated with death in Turkish and Persian literature, Taj Mahal, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Nadejda Tchijova, “Vector three red poppies with stems isolated on a white background,” 123RF Limited 2020, accessed October 2020, https://www.123rf.com/photo_61538634_stock-vector-vector-three-red-poppies-with-ste ms-isolated-on-a-white-background-.html

Fig. 2. Chopdekar, Manasi. Plan view of the Taj Mahal Gardens, Agra - Mughal waterfront garden, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Pressbooks, “Taj Mahal, UNKNOWN DESIGNER, AGRA, India, 1632-54 AD.” Accessed October 2020, https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/exploringarchitectureandlandscape/chapter/taj-mahal/

Fig. 3. Chopdekar, Manasi. Char Bagh Layout showing waterway network, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Arunkrishnan, “Learn this not so well known fact about the Taj Mahal before your visit,” The Mughals of India, accessed October 2020, http://themughalsofindia.com/learn-this-not-so-well-known-fact-about-the-taj-mahal-befo re-your-visitlearn-this-not-so-well-known-fact-about-the-taj-mahal-before-your-visit/

Fig. 1 Entrance to Giardino Giusti’s Lower Gardens

Giardino Giusti Verona, Italy

The elite Lower Gardens

1. History and significance of the Giusti Garden 2. Understanding the Lower Gardens of the palace as a symbol of elite status: (a) Order and symmetry in garden layout (b) Impressive display of the belvedere 3. Conclusion 4. References

Goethe Cypress - admirable natural relic 2

Main courtyard and entrance to Giardino Giusti (as seen in fig. 1) Giusti Palace Lawn with simple edges

Vaseria Wooded area contrasting the ordered layout of the Lower Gardens - creating framed views to a wilder part of the garden(see fig. 4) - theatrical element of surprise in the 0verall layout

Giardino all’italiana style division of the garden into nine square sections. Prominent Italian rennaisance design features here include Parterre gardens with trimmed box hedges - emphasis on ‘man-made’ over naturalistic landscape design 3

Lower Gardens Marble statues of prominent Greek mythical figures like Apollo and Adonis placed at the center of each of the nine divisions 4(colored black)

Location of the Belvedere (see fig. 4 and 5).

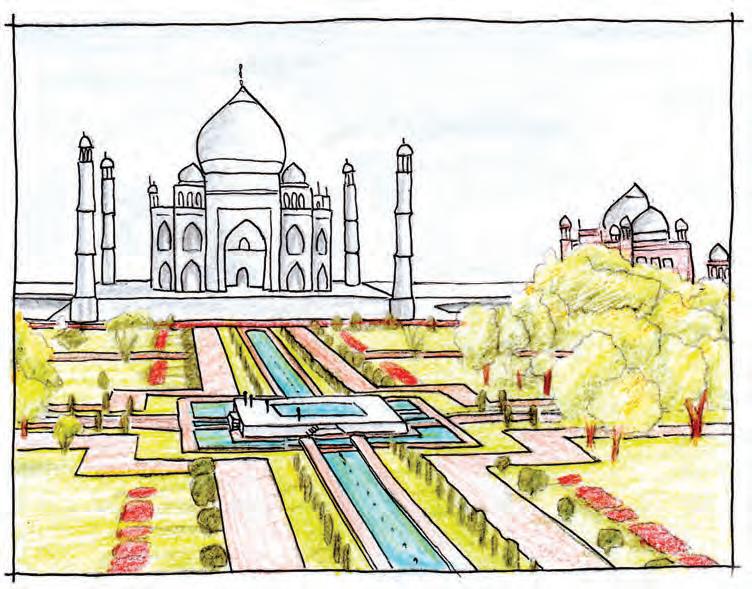

Fig. 2 Aerial drawing of Giardino Giusti, gardens in Giusti Palace, Verona, Italy

3.1. History and Significance

Considered to be one of the finest examples of Italian Renaissance gardens, Giardino Giusti (see fig. 2) was designed by Agostino Giusti, 5 knight of the Venetian Republic and gentleman-in-waiting of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, in 1570. Since then, there have been many 6 modifications to the Garden by other designers (see fig. 5), contributing to elevate the elite status of the Garden.

Designed for the wealthy Giusti family who moved from their home in Tuscany, to Verona in order to further their wool industry interests and wealth, Giardino Giusti brought the different functional spaces of the Giusti Palace under one roof. 7

As a knight of the Republic, Agostino Giusti also had connections with prominent ruling families of Europe, including the Medici and Habsburgs, making Giardino Giusti a key visitation spot for many elite and famous visitors, including Cosimo III De Medici (The penultimate Grand Duke of Tuscany) and Alessandro I (the Tsar of Russia).8

This chapter will analyse the different Renaissance garden elements of Giardino Giusti that served to reflect the Giusti family’s elite status in society.

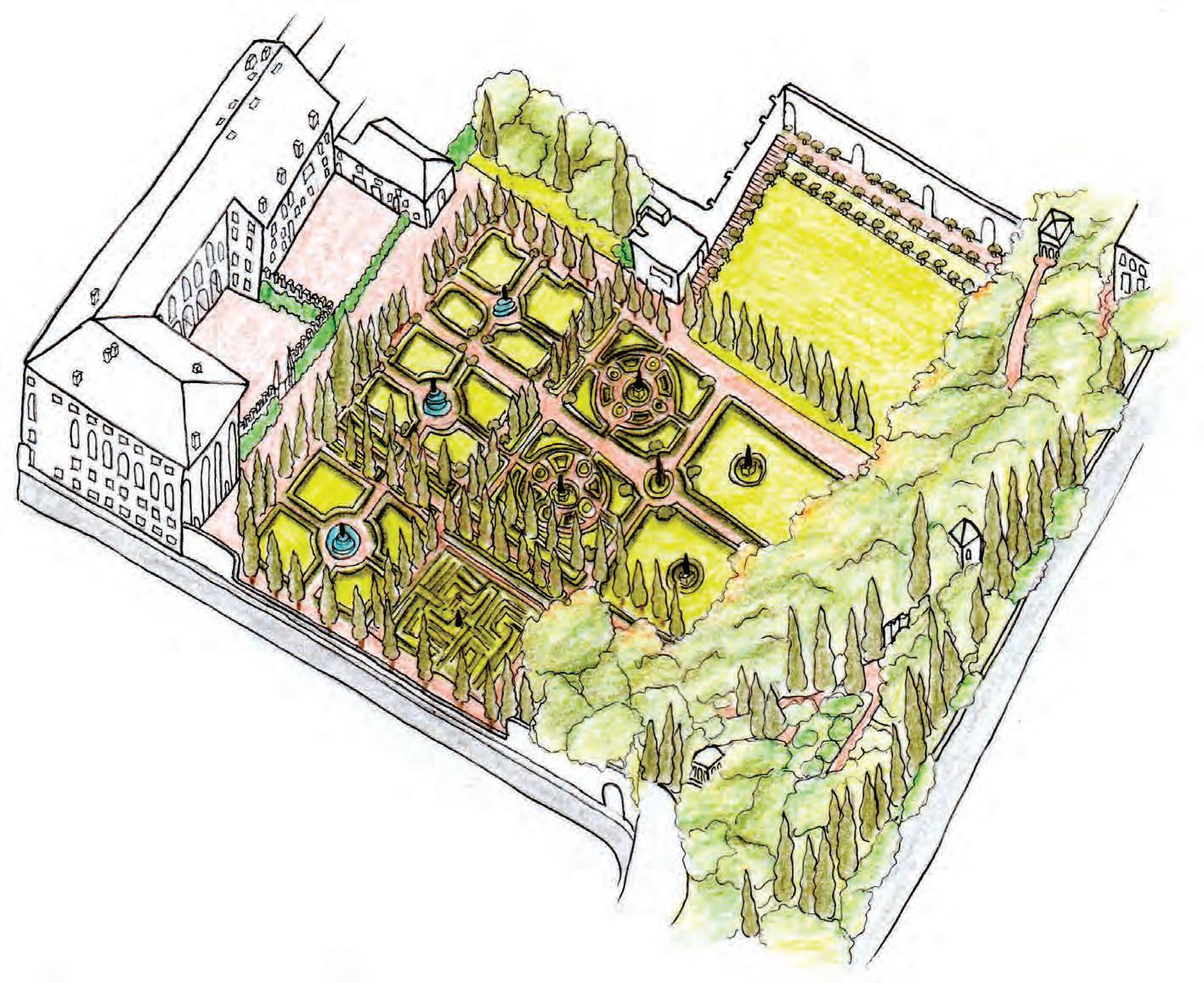

Walking through the entrance gate with high walled enclosure ornamented with “the distinctive swallowtail battlements of the Ghibelline faction” 9 (referencing to the Giusti family origins), visitors of the Garden would start to see the view in fig. 3 after strolling past long linear rows of tall cypress trees.

Parterres with trimmed box hedges arranged in geometric patterns, creating ‘outside rooms’ would 10 serve to impress the foreign elite scholars who visited the Gardens, through the calculated order in their layout and maintenance.

Combined with beautiful marble statues of Greek mythological figures associated with beauty, such as Adonis, Apollo and Venus (see fig. 3), it conveys 11 that the designer and owner of the garden had a sophisticated taste of design.

symmetry of the gardens reflecting the architecture of the palace - 12 expereince of strolling through space that is designed for the wealthy extending to the outdoors

wide sweeping green lawns - no wild outgrowth, expensive to maintain - shows the wealth of the Garden owner

Fig. 3 Parterre Alla Francese in Giardino Giusti’s Lower Gardens

3.2. (b) Theatrical Belvedere design

Fig. 5 Grotesque mask-belvedere designed by sculptor Bartolomeo Ridolfi

“The rocky precipice, the grotto, the play of light and shade and perspectives” are all important aspects of 13 the Italian Renaissance Garden that would evoke feelings of admiration, wonder and even a little intimidation towards the grandeur and class of the owner as the visitor would climb its steep and shady paths (see fig. 4).

The belvedere on top of the grotesque mask (see fig. 5) is at a high point from where beautiful views of Verona can be observed.14

The mouth designed to spew fire and smoke, the dramatics impressing and frightening visitors – a show of status and 15association with elite interest in theatre and performance associated with the Italian Renaissance gardens.

Fig. 4 Gate in fig. 1 leading to the Mascheron in Upper Gardens, right past the Lower Gardens

As the visitor would walk past the entrance gate, straight through the Lower Gardens (see fig. 1) they would arrive at almost a theatrical set-up complete with sweeping stairs and framed views to the Belvedere.

3.3. Conclusion

The idea of a garden being an expression of its civilization’s ideas and values is evident in the way 16 Italian Renaissance gardens were designed, with purpose and intellect, showcasing elite refined taste in art and culture through impressive landscape design. Alluding to Greek references and theatrical set-ups, with neat, ordered and maintained trees and plantings, Giardino Giusti resonates with the order and sophistication that is associated with the upper class Italian society of the time, bringing elite tourists from all over the world to marvel at its beauty.

Giannetto, Raffaella Fabiani. "Introduction," In Medici Gardens: From Making to Design. PHILADELPHIA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1n7qk42.4?refreqid=excelsior%3Acf6262d48080c23876 ab1ffd31121b5f&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Giardino Giusti, “Giardino Giusti: Nature, art and history.” Accessed October 2020, https://giardinogiusti.com/article/11305/il-giardino/?lan=en

Great Gardens of the World, “Giardino Giusti Italy.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.greatgardensoftheworld.com/gardens/giardino-giusti/

Hunt, John Dixon. "Garden and Theatre," In Garden and Grove: The Italian Renaissance Garden in the English Imagination, 1600-1750. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt19rmc47.11?refreqid=excelsior%3Ac9131cae731bd12fb dfeb088cf303b73&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Jellicoe, G. A. "Italian Renaissance Gardens: Historic design in the light of modern thinking," Landscape Architecture 44, no. 1 (1953): 11-21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44659184?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Saniga, Andrew. “Renaissance Ideas: Italy and France and the Baroque across Europe.” Lecture, University of Melbourne, Parkville VIC, August 25, 2020.

Wickers, Kate. “Giardino Giusti Verona,” ITALY Magazine, published July 05, 2012, https://www.italymagazine.com/featured-story/giardino-giusti-verona

FIGURE REFERENCES

Fig. 1. Chopdekar, Manasi. Entrance to Giardino Giusti’s Lower Gardens, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Giardino Giusti, “Giardino Giusti: Nature, art and history.” Accessed October 2020, https://giardinogiusti.com/article/11305/il-giardino/?lan=en

Fig. 2. Chopdekar, Manasi. Aerial drawing of Giardino Giusti, gardens in Giusti Palace, Verona, Italy, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Giardino Giusti, “Giardino Giusti: Nature, art and history.” Accessed October 2020, https://giardinogiusti.com/article/11305/il-giardino/?lan=en

Fig. 3. Chopdekar, Manasi. Parterre Alla Francese in Giardino Giusti’s Lower Gardens, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Wickers, Kate. “Giardino Giusti Verona,” ITALY Magazine, published July 05, 2012, https://www.italymagazine.com/featured-story/giardino-giusti-verona

Fig. 4. Chopdekar, Manasi. Gate in fig. 1 leading to the Mascheron in Upper Gardens, right past the Lower Gardens, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Helenius, Pentti. “Verona, Giardino Giusti.” Accessed October 2020, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palazzo_Giusti_(Verona)#/media/File:Giardino_Giusti.JPG

Fig. 5. Chopdekar, Manasi. Grotesque mask-belvedere designed by sculptor Bartolomeo Ridolfi, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Great Gardens of the World, “Giardino Giusti Italy.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.greatgardensoftheworld.com/gardens/giardino-giusti/

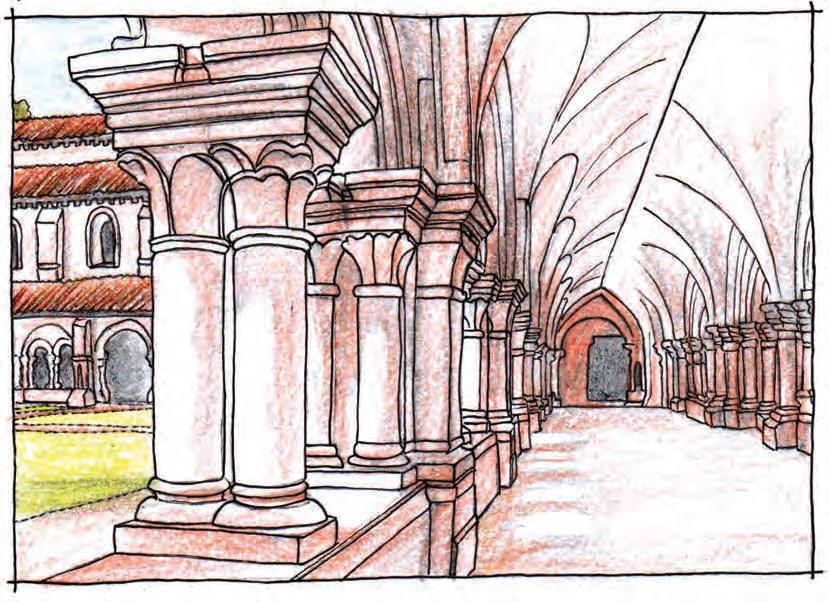

Fig. 1 Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay (France), aerial view

The Abbey of Fontenay Burgundy, France

Introspection in the cloister garden

1. History and significance of the Abbey 2. Understanding cloister garden as a place of introspection in Cistercian monastic life: (a) Sense of order in garden design (b) Importance of light and open space design 3. Conclusion 4. References

Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981, the Abbey of Fontenay is the “oldest preserved Cistercian abbey in the world”. It was designed and 1 constructed between 1139-47 by Abbot Guillaume in Romanesque style, with funding provided by Ebraud, Bishop of Norwich. 2

The Cistercian lifestyle values of self-sufficiency and simplicity can be clearly seen in its remote geographical location - isolated from cities and dense populations, but near a water source with agricultural lands, and the design style and specialised functions of its different spaces that are encompassed within the grounds of the Abbey (see fig. 1 and 2). 3

Cistercian architecture was, as per the Rule of St. Benedict, simple, scholarly and utilitarian, and this 4 is reflected not only in its built architecture elements but also in its landscape design.

This chapter will analyse the different features of the cloister at the Abbey of Fontenay that, in its simplicity and austerity, reflect the ideals of the contemplative and introspective Cistercian monastic life. Cloister garden - symmetrical form, geometric garden bed layout, with pathways leading to Church, Chapter house, dorms, kitchen, medicinal gardens and refectory at immediate surroundings through cloister corridor

Forest area surrounding the abbey at 5 km radius - design intent - isolation and self-sufficiency to allow complete focus on a religious and simplistic lifestyle Medicinal gardens

Dormitory Chapter house

Church

Abbot lodgings Monk’s room

Refectory

Kitchen Infirmary Ruisseau de Fontenay

Lake

Dovecote

Bakery

Kennel Library Guesthouse

Entrance

Car park

Fig. 2 Plan view of the Abbey of Fontenay with functional spaces

4.2. (a) Order in spatial design - order in lifestyle

The Rule of St. Benedict, followed by Cistercian monasteries, emphasized on order and silence, living removed from the rest of the world, much like a hermit, but with other monks in a self-sufficient community guided by spiritual values of the Church. These spiritual values 5 could be deeply contemplated upon in silence in cloister spaces adjacent to the Church.

“Paradise is among us here, in spiritual exercise, simple prayer and holy meditation.” - Matthew of Rievaulx 6

The lack of ornamentation and strict geometric layout with trimmed Cypress trees (see fig. 3) evoke feelings of serenity and provided little distractions in the surroundings, thereby creating a meditative environment - a key aspect of Cistercian monastic life. 7

Subject to strict rules pertaining silence, even though recreational talking was not allowed, the words from the Church readings were allowed to be read out loud slowly and contemplatively, in order to educate monks collectively in the communal space of the cloister. 8

The open cloister garden design with bare lawns provided spaces to rest and read. The sense of enclosure facilitated by the cloister when standing in the garden, evoked a feeling of disconnect with the outside world and its distractions, and allowed the monks to introspect and reflect on the Church teachings. 9

Surrounding walls and roofs enclosing the garden of minimal design ornamentation - directing public gaze skyward, towards the Heavens

However, being connected to different buildings in the abbey, and functioning as a movement zone, the cloister would have also been a busy space with active shuffling of monks about their daily activities, and echoes of the Church bells and prayers.

This placed the act of introspection at the heart of daily life, and made it an essential and regular part of Cistercian monastic lifestyle.

Cloister garden - geometric layout, bare lawns - minimal distractions with lack of flower ornamentation

Fig. 4 Cloister corridor at the Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay Fig. 3 Cloister garden at Abbey of Fontenay - simplicity characteristic of Cistercian architecture

Vaulted ceiling- opens up the interior

Simple columns (detailing in design varies between each column through the capital design) with rough texture and no external ornametation

Light streaming in wide openings

4.2. (b) Open space - spatial & spiritual awareness

The cloister corridor is connected to the garden through its open window arches and vaulted ceilings, thus facilitating an open flow of space between the garden and the cloister’s covered walkway (see fig. 4). This allows the natural and built 10 enviornment to work together to evoke a sense of inner peace.

The austere design of the arches and columns, forming a rectangle of 36 x 38 sq. m., as seen in fig. 1 and 4, reflected the values of simplicity of Cistercian architecture in its homogeneity, with wide openings to let the corridors and its users be bathed “at any time of the day and throughout the year”. This would have 11 through the

allowed the monks to feel a closer connection to God and heavenly light.

These corridors were also used to conduct processional liturgical rounds, and with barred entry to outsiders and the otherwise 12 silent atmosphere, allowed the monks to fully immerse themselves in the space and in their worship.

4.3. Conclusion

Wide corridors connected to the Garden - continued flow of open space

The Abbey of Fontenay has since undergone changes with new constructions (the 17th century Abbot’s Palace), and demolitions (refectory - 18th century - see fig. 2 for original location). However, its restoration from 1906 has ensured well-preservation of majority of the Abbey. Therefore, the Cistercian values of 13 14 simplicity and strict modesty, the defining traits of Cistercian way of living, that enabled introspective spaces in the abbey can still be observed today through their architectural and landscape design that serve to elevate awareness of oneself and their surroundings.

Surrounding greenery providing fresh air and openness in the enclosed garden space - connection to the natural outdoors while the enclosure acts as a potential barrier to earthly distractions

Cloister corridor with vaulted ceiling and sculptured arches

Cypress tree - being the only additional plantation in the cloister garden, it completes the space without overwhelming it through ornamentation

4.4. References

Abbaye de Fontenay, “Fontenay Abbey: 12th century - Burgundy - World Heritage: Cloister.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.abbayedefontenay.com/en/discover-fontenay/the-abbey-and-its-gardens/clois ter

Burton, Janet and Kerr, Julie. "Ora Et Labora: Daily Life in the Cloister." In The Cistercians in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer, 2011). Accessed October 21, 2020. doi:10.7722/j.ctt81g36.11.

C’est La Vie, “Abbey of Fontenay.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.charterbargefrance.com/places-to-visit/abbey-of-fontenay/

Dom Aelred, Sillem. "THE MONASTIC IDEAL." Life of the Spirit (1946-1964) 7, no. 79 (1953): 296-303, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43704174?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents

Meyvaert, Paul. "The Medieval Monastic Claustrum," Gesta 12, no. 1/2 (1973): 53-59, https://www.jstor.org/stable/766634?seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents

UNESCO World Heritage Centre 1992-2020, “Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay.” Accessed October 2020, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/165/

FIGURE REFERENCES

Fig. 1. Chopdekar, Manasi. Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay (France), aerial view, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Alamy Stock Photo, “FONTENAY ABBEY (aerial view). Montbard, Cote d'Or, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, France.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.alamy.com/fontenay-abbey-aerial-view-montbard-cote-dor-bourgogne-franc he-comt-france-image223811925.html

Fig. 2. Chopdekar, Manasi. Plan view of the Abbey of Fontenay with functional spaces, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Thomas Davies Clay , “CATHEDRAL QUEST.” Accessed October 2020, http://www.cathedralquest.com/France12Day4.htm

Fig. 3. Chopdekar, Manasi. Cloister garden at Abbey of Fontenay - simplicity characteristic of Cistercian architecture, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Abbaye de Fontenay, “Fontenay Abbey: 12th century - Burgundy - World Heritage: Cloister.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.abbayedefontenay.com/en/discover-fontenay/the-abbey-and-its-gardens/clois ter

Fig. 4. Chopdekar, Manasi. Cloister corridor at the Cistercian Abbey of Fontenay, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Abbaye de Fontenay, “Fontenay Abbey: 12th century - Burgundy - World Heritage: Cloister.” Accessed October 2020, https://www.abbayedefontenay.com/en/discover-fontenay/the-abbey-and-its-gardens/clois ter

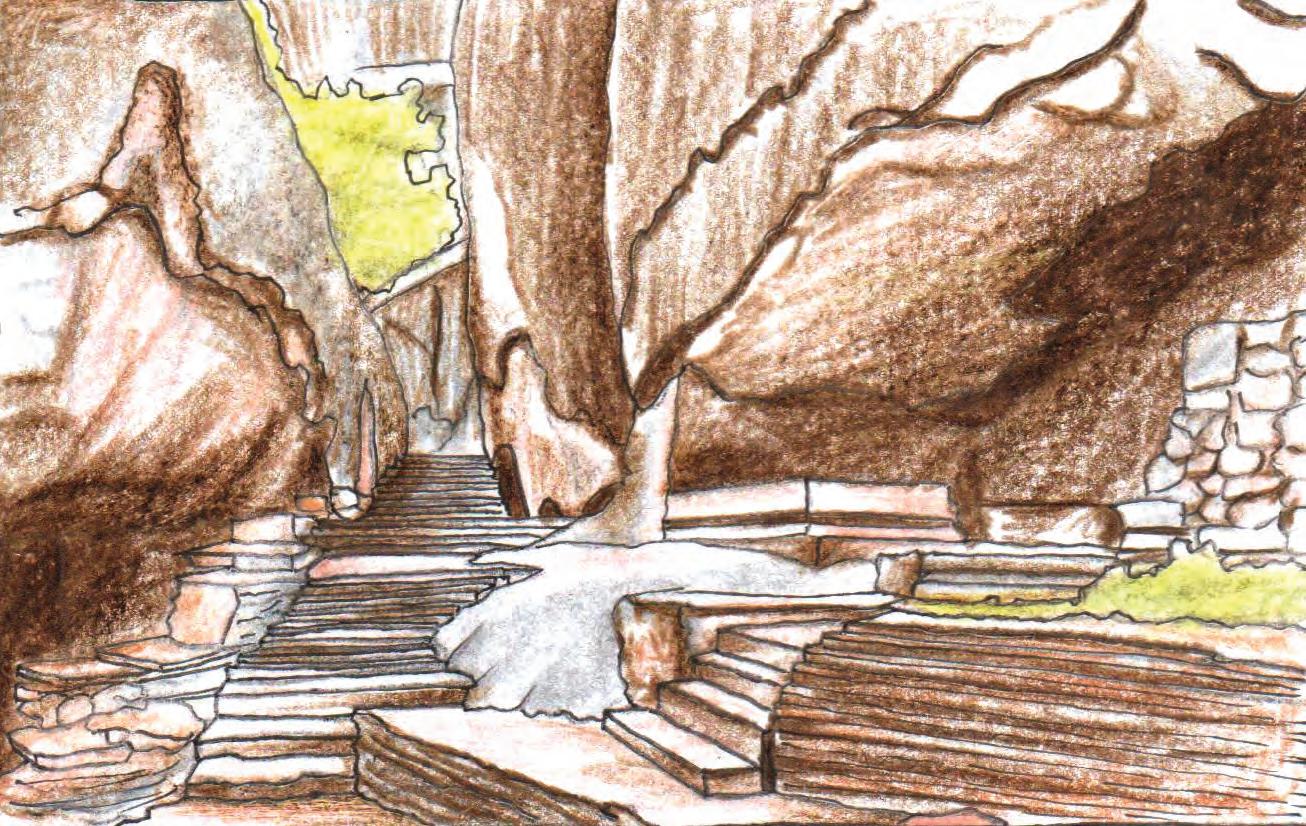

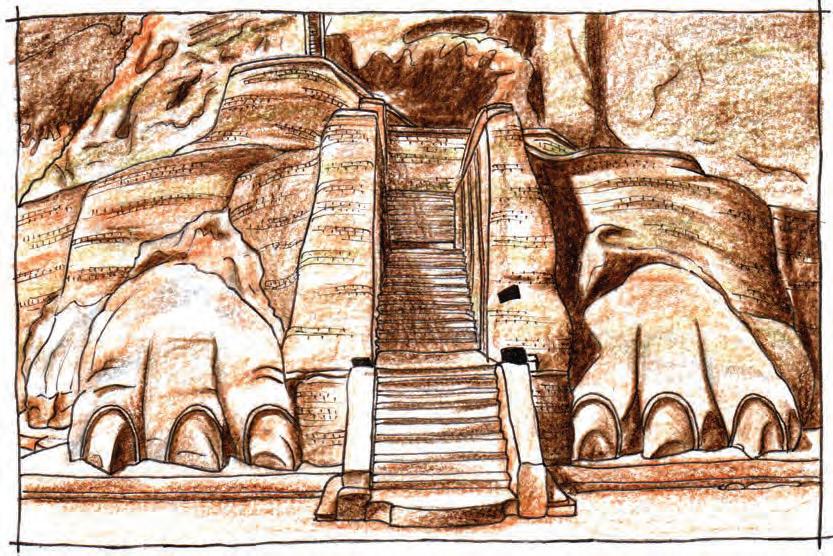

Fig. 1 Boulders over limestone-inlaid steps surrounding Sigiriya Rock Fortress (part of Boulder Gardens) - used by monks for habitation

Sigiriya Fortress Matale district, Sri Lanka

Defensive measures in Fortress Garden

1. History and significance of Sigiriya 2. Sri Lankan Landscape Traditions 3. Understanding the defense measures in different parts of the Fortress Gardens (a) Controlled water network (b) Intimidating Boulder design 4. Conclusion 5. References

Designated as one of the eight World Heritage Sites of Sri Lanka , Sigiriya Palace Fortress 1 and Gardens were commissioned between 477 A.D. – 495 A.D. by the then king Kashyapa I, who ruled the native Sinhalese dynasty, the Moriya.2

Kasyapa I (477-495), a son of King Dhatusena (459-477) was not the lawful heir to the throne and rose to power through a palace conspiracy, which ultimately led to his father’s execution. 3 Fearing the inevitable return of the true heir to the throne, he took refuge in the “inaccessible stronghold of Sigiriya”.4

Kasyapa built a palace on the summit of the gigantic rock of Sigiriya (see fig. 4) with natural defence measures on the ground level through elaborate architecture, engineering and landscape design planning (see fig. 2). This chapter analyses the functionality of some of these landscape elements as key defence measures.

Four quartered garden style similar to Taj Mahal’s Char Bagh layout

Boulder Gardens

Outer Moat

Outer Rampart Water Garden 1 Water Garden 2 Northern Entrance Boulders (in white)

Middle Rampart

Inner Moat

Inner Rampart

5.2. Local landscape design traditions

Similar to many South Asian civilizations, ancient Sri Lankans believed themselves to be an intrinsic part of nature, and therefore greatly respected nature. This belief was also incorporated 5 in their Buddhist teachings. 6

Emeritus Prof. Senake Bandaranayake identifies three major ‘landscape traditions’ at Sigiriya: 7 (1) Symmetrical water gardens (2) Organic boulder gardens (3) Stepped tiers or hanging gardens

According to him, these traditions have been a part of Sri Lankan landscape design and architecture from the late 10-1 century BCE.8

With a pleasant natural enviornment facilitating outdoor living, nature was regarded as a ‘guardian’, 9 and this is evident in the early monastic rock shelters on site (see fig. 1).

Western Entrance

Miniature Water Garden

Southern Entrance Summer Palace

Sigiriya Rock and Palace Complex - palace located at a height of 180 m 10above the surrounding plains and on top of Sigiriya Rock.

Fig. 2 Plan of landscape design around Sigiriya Palace complex

Underground water conduits shown through blue arrow aesthetic as well as functional

Summer Palace isolated due to Water Garden 3 /moat

Inner moat

Fig. 3 Plan drawing of Sigiriya’s Water Gardens (see from fig. 1) Main axial path Its water tanks are interconnected with ingenious underground conduits and while they act as water storage facilities, they also work as pressure chambers for the fountains through a gravity feed system.12

Intentional release of water from the tanks could lead to steady flooding of the plains through the fountains - a potential defense mechanism.

The rigid geometry of the structural elements contrast to the wild greenery of the surrounding the Sigiriya Rock. 13

Marshy area created by moats

Once the site of an elaborate pavilion - Water Garden 1 (see from fig. 2) was once part of a large pleasure garden complex 14 Water Fountains shown in black dots - fully functioning today and can be observed during the rainy season 15 Water Gardens framing the view to Sigiriya Palace Complex atop the Rock -

plains and the paths become narrower closer to

Fig. 4 View of Sigiriya rock and palace complex from the main axial path

Water tanks with fountains - regulated through underground conduits

5.3. (b) Psychological security through boulder design

Entrance gates to the palace complex and gardens are very narrow (see fig. 2), thereby limiting the number of people who could enter at a time - increasing defense against army attacks.

Further defensive tactics were implemented through intimidation using large boulder designs, such as the Lion Paws Gate which acts as a psychological and physical barrier (narrow entrance and stairs, limiting access to few people at a time - also seen in fig. 1).16

Together with the palace complex itself being atop a rock rising 180m above the surroundings, Kasyapa I built on psychological and physical defense measures using the surrounding landscape through ingenious design

Narrow staircase with high walls surrounding it

According to Sinhalese tradition, the lion is considered as the mythical ancestor of kings and a symbol of royal authority 17 techniques that made the complex a palace and a fortress.

- additional layer of defense through intimidation using cultural references

Fig. 5 Lion Paws Gate at Sigiriya - entrance to the main palace on top of the Sigiriya Rock

5.4. Conclusion

While these defence measures were not as effective in protecting Kasyapa I from being killed by his half-brother and true heir to the throne, it is an interesting 18 case study to understand how landscape design can be used in a combination of organic and artificial ways to boost physical and psychological security measures, while functioning as a regular palace garden.

Bandaranayake, Senake. “Amongst Asia's earliest surviving gardens: the Royal and Monastic gardens at Sigiriya and Anuradhapura,” in Historic Gardens and Sites. Sri Lanka: ICOMOS 10th General Assembly, 1993. https://www.icomos.org/publications/93garden2.pdf

Cooray, Nilan. “The Sigiriya Royal Gardens. Analysis of the Landscape Architectonic Composition,” A+BE Architecture and the Built Envrionment 6 (November 2012). doi: 10.7480/abe.2012.6

Tracyanddale, “The Water Gardens of Sigiriya.” Accessed October 2020, http://www.tracyanddale.50megs.com/Sri%20Lanka/HTML%20Page/wgarden.html

Udalamatta, SS. “The use of water and hydraulics in the landscape design of Sigiriya.” PhD diss., University of Moratuwa, 2003. http://dl.lib.mrt.ac.lk/handle/123/1329

UNESCO World Heritage Centre 1992-2020, “Ancient City of Sigiriya.” Accessed October 2020, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/202

Walker, Veronica. “The 'Lion Fortress' of Sri Lanka was swallowed by the jungle,” National Geographic, published Sept 3, 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2019/09-10/sri-lanka-sigiriya-fort ress/

FIGURE REFERENCES

Fig. 1. Chopdekar, Manasi. Boulders over limestone-inlaid steps surrounding Sigiriya Rock Fortress (part of Boulder Gardens), 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Tracyanddale, “The Boulder Gardens of Sigiriya.” Accessed October 2020, http://www.tracyanddale.50megs.com/Sri%20Lanka/HTML%20Page/bgarden.html

Fig. 2. Chopdekar, Manasi. Plan of landscape design around Sigiriya Palace complex, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Cooray, Nilan. “The Sigiriya Royal Gardens. Analysis of the Landscape Architectonic Composition,” A+BE Architecture and the Built Envrionment 6 (November 2012): 67. doi: 10.7480/abe.2012.6, from Tracyanddale, “The Water Gardens of Sigiriya.” Accessed October 2020, http://www.tracyanddale.50megs.com/Sri%20Lanka/HTML%20Page/wgarden.html, from Tracyanddale, “The Boulder Gardens of Sigiriya.” Accessed October 2020, http://www.tracyanddale.50megs.com/Sri%20Lanka/HTML%20Page/bgarden.html

Fig. 3. Chopdekar, Manasi. Plan drawing of Sigiriya’s Water Gardens, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Bandaranayake, Senake. “Amongst Asia's earliest surviving gardens: the Royal and Monastic gardens at Sigiriya and Anuradhapura,” in Historic Gardens and Sites. Sri Lanka: ICOMOS 10th General Assembly, 1993, pg. 11. https://www.icomos.org/publications/93garden2.pdf

Fig. 4. Chopdekar, Manasi. View of Sigiriya rock and palace complex from the main axial path, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Drivers In Sri Lanka, “SIGIRIYA ONE DAY.” Accessed October 2020, https://driversinsrilanka.com/destination/sigiriya/

Fig. 5. Chopdekar, Manasi. Lion Paws Gate at Sigiriya - entrance to the main palace on top of the Sigiriya Rock, 2020, color pencils on paper, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria. Image reference from Walker, Veronica. “The 'Lion Fortress' of Sri Lanka was swallowed by the jungle,” National Geographic, published Sept 3, 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2019/09-10/sri-lanka-sigiriya-fort ress/