28 minute read

Introduction Shakeel Hossain

introduction

Shakeel Hossain

Advertisement

‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan (1556–1627) was the son of Bairam Khan-i-Khanan,

the regent of Mughal Emperor Akbar from 1556 to 1560. Upon his birth, Maulana

Fariduddin Dehlavi, the learned associate of Bairam Khan, composed the line (of

chronogram) yielding the year of his birth: “The pearl from the river of good fortune

has come forth.” 1

The Mughal annals record this “pearl” to have grown up to be the greatest of the all greats, the noble of

nobles, Khan-i-Khanan, of the courts of the Mughal Empire (1526–1857). However, the multifaceted shines

of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan’s genius and compassion faded within the changing times in the mosaic of Indian history. It was also the changing times of early 20th century “Indian” nationalism, which re-produced

Rahim to modern India through his Hindi literature. The Indic languages and imageries of the poetry of ‘Abdur

Rahim Khan-i-Khanan drew curious interests from writers and scholars with the discovery of his Hindi verses

and, later, with the finding of volumes (together, the three volumes run into 3,000 pages) of his biography in

Persian by ‘Abdul Baqi Nihavandi, Ma’āsir-i-Rahīmī. 2 Who was this larger-than-life Khan-i-Khanan of Emperor

Akbar (r 1556–1605) and Emperor Jahangir (r 1605–1628)? Later, a mentor of Prince Khurram (Emperor

Shah Jahan, son and successor of Jahangir), for whom he went to battle with the imperial Mughal army.

Who was he, the unmatched soldier and statesman, who wrote poems in Persian, Sanskrit and in dialects

of Hindavi, with metaphors ranging from Giridhar to Ganga, evoking basics of morals and human values in

precise and concise mātrās (metres) of dohās and barvais? His barvais supposedly inspired Tulsidas to write

his Barvai Rāmāyana. 3 He became so legendary for his generosity and patronage in his own time that great

poets composed uncounted verses in Sanskrit, Hindavi and Persian in praise of him. As a lover of books,

his library, unfortunately lost to the ravages of time, has been recorded in history as one of the grandest in the Mughal Empire. 4

This book, Celebrating Rahim, catalogues the festival of exhibition, concerts, plays and lectures, and sets out to capture all of the above to present ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan’s manifold attributes and genius.

The festival is curated to touch upon the many aspects of Rahim, as he his commonly known, so we can get

a glimpse of this larger-than-life Khan-i-Khanan and learn to appreciate the syncretic milieu of early Mughal Empire. One can argue whether it was intentionally syncretic or not, but there can be no doubt from the

readings of Rahim’s poems and his use of metaphors that one had the knowledge and appreciation of the other—a vital ingredient of plurality.

Further readings into the court culture of the early Mughal Empire 5 give evidence of the meetings of the

minds and arts between the Muslims and the Hindus under the secular patronage of Akbar. Here, the

classical Sanskrit scriptures and epics of the Indic traditions were discussed and translated into Persian. The translations were beautifully compiled with exquisite miniature paintings. One of the most intricately

illustrated manuscripts commissioned by Akbar was Valmiki’s Rāmāyana. It was copied with permission

in the kārkhāna (atelier) of Mirza Khan ‘Abdur Rahim. 6 Today, it is in the collection of the Freer Gallery,

Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C.

The festival also sets out to celebrate the secular canvas of Rahim’s verses and patronage. As mentioned

earlier, the “re-birth” of Rahim was part of the Hindu nationalistic revivalism after the end of the Mughal Empire. The British rule (1857–1947) brought the diverse communities of India on equal grounds. It gave

the Hindu intellectuals and populace a platform to propagate their traditions and expressions. The language culture that grew out of the interactions of the Persianate world, with its roots in Central Asia and Iran, and age-old Indic traditions began to be replaced by Sanskritized Hindi and local dialects. Writers and publishers

soon began to produce books in Hindi rather than Urdu, which was the popular language of literature towards the end of the Mughal era. In that process, compilations and revivals of poetry in Sanskrit and

Hindavi found new grounds and instigated new research in the field. In one such research, the Hindavi and Sanskrit verses of Rahim were produced. The first essay here, by T.C.A. Raghavan, walks us through the late

19th and early-20th century rise of Hindi literature. It traces the history of Hindi literature in modern India, in which lies the discovery of Rahim’s poems.

Raghavan’s essay, “The Revival of Rahim in Modern India”, placed in the beginning of the book Celebrating Rahim, is essential, for it locates Rahim in the context of the present, which is the core intention of festival’s

curatorial concept. It connects the contemporary direction of Hindi literature with Rahim, the poet of dohās

heavily loaded with Hindu idioms, as he is popularly remembered today. For it can be argued that without

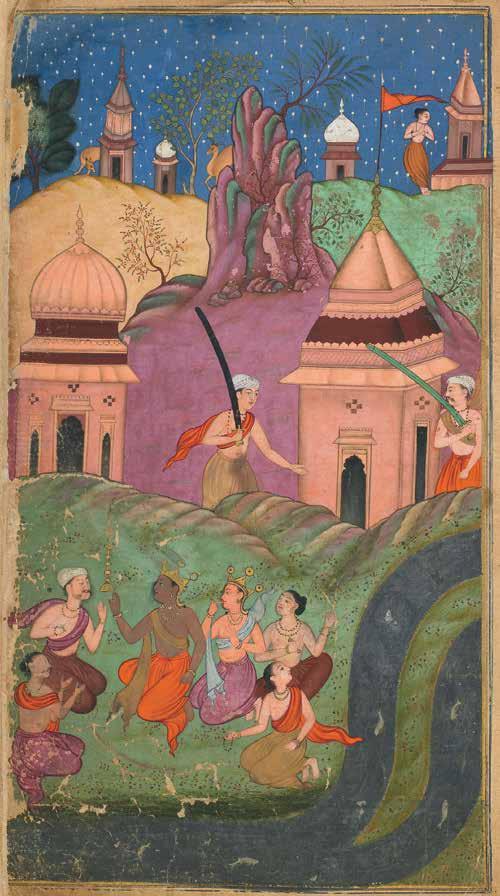

(Previous page) Muhammad Amin Diwan, a trusted aide, escorting the widow of Bairam Khan and her infant son ‘Abdur Rahim to Ahmedabad in 1561, following the assassination of Bairam Khan. This image is said to be from the first illustrated copy of the Akbarnāma. It drew upon the expertise of some of the best royal painters of the time, many of whom receive special mention by Abu’l Fazl in his ‘Āīn-i-Akbarī. Opaque watercolour and gold on paper; 32.1 cm x 19 cm; Artist: Mukund. c. 1586–89 (made). Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS. 2:5-1896. ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

the nationalistic urge to revive Hindi literature, beginning at the end of the Muslim rule and in the face of the prevailing Persian and Urdu literature, the study of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan may not have generated the momentum and popularity that one can see from the many studies and books (mainly in Hindi) on him.

As the second essay, by the author Harish Trivedi, clearly exemplifies, there is another argument for the growing popularity of the verses of Rahim—“the sheer simplicity and felicity of the verses, and the sweet

and-sour pragmatic wisdom which they express”—that they stay with the readers as precious pearls of worldly experience. Harish Trivedi calls him “one of the most widely popular poets in all Hindi literature”.

There are comparisons, in his essay, with other great poets of his times and later poets, substantiated with quotes and parallel references. There are several charming references, anecdotes and examples of Rahim

and his poetry in Trivedi’s work, such that one can comprehend the making of Rahim as a legend in the world of Hindi poetry. However, Rahim was not a poet like the bhakt (religious devotees) poets—Surdas, Tulsidas, Kabir—with whom he is equally compared. Rahim was a soldier most of his early life and spent years in

battlefields and military campaigns with Emperor Akbar, later to become governor (sūbadār) of Gujarat to follow with Sindh and the Deccan. 7 In all, he was “as prodigious with the pen as with the sword”, to quote

from Trivedi’s contribution in this book.

The other poet cited by Trivedi in this book is Kabir, who was brought up by a Muslim family but, like Rahim,

primarily wrote poems with Hindu idioms, with references to Muslim beliefs and rituals. He spoke of rising above their worldly practices, speaking of morals in the realm of nirgūna, one without human/worldly attributes. But unlike him, Rahim does not make many evocations of the two religions in the same breath,

nor does he render exclusively Islamic symbolisms. Though Allison Busch, later in this book, makes convincing analyses of Rahim’s verses being sufiānā, in the mystical dimensions of Islam, they are interpretations and

not direct renditions of Sufi canons.

At heart, he was likely a bhakt, drawing more from the Hindu religious narratives and customs of veneration,

as is apparent in his poetry, rather than the abstract mystical concepts of the Sufis in India. By the time of Emperor Akbar, definite orders (silsilās) of Sufis were well established in India. We know of the popular story of Akbar’s devotion to Shaikh Salim Chishti of Sikri; in the devotion of Chishti, Akbar built his new capital city

of Fatehpur Sikri. Akbar was a patron of the shrine of the Sufi Shaikh Hazrat Nizamuddin Awliyā’ (d 1325) of Delhi too. It is to be noted that, in the barkat (blessing) of this Sufi saint, ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan built the mausoleum for his wife; it is here that he himself is buried. Yet, rarely does he include Sufi evocations in his poetry. There are, however, poems of his in Persian, also poems with a mix of Persian and Hindavi

lines, similar to the poems of the 13th–14th-century Delhi poet Amir Khusrau. Trivedi draws comparisons between the two in his essay. Amir Khusrau is also legendary for his Hindavi poems, which continue to be

sung by the qawwāls across South Asia. On the other hand, his Persian poems, of which he has many dīvāns

(compilations of poems), are rarely sung and remembered today. Though they lived more than two centuries apart, the comparison between the two is intriguing and revealing in several layers, especially in reference to their Hindavi repertoire. Another discussion on this will be elaborated later.

For now, it is to be noted that the other reason for the continuing popularity of his verses written in 16th–17th-century Mughal India even in the modern times is that he wrote mainly in the sweet and rhythmic

dialects of vernacular Hindi language—Braj Bhasha and Avadhi. But why did he write in Braj and Avadhi,

especially laden with Hindu idioms and religious references, when he was a high-ranking Muslim noble in

Persianate Mughal courts? Though his mother was Indian-born, Raj Gusain, daughter of the Chief of Mewat,

and his mother tongue can be said to be Hindavi, ‘Abdur Rahim was a Turk who conventionally spoke Turki and Persian. By the time of Akbar, very few could speak Chaghatay Turki, the mother tongue of the Mughals,

but ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan could speak and read well enough to translate Babur’s autobiography,

Vaqī‘at-i-Bāburī into Persian. These translations were not very well done, however, as is demonstrated by

Wheeler M. Thackston in his essay in this book. Thackston points out that his translation to Persian sticks

so close to the original syntax of Chaghatay Turki that meanings are distorted and the Persian outcome is,

sometimes, incomprehensible without the knowledge of Chaghatay Turki. Fortunately for Rahim, Akbar may

have known the language of his grandfather, Babur.

‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan was gifted with languages; he was a polyglot like his father, Bairam Khan.

‘Abdur Rahim was blessed with all of the wonderful traits of his father, who was also bestowed with the

title of Khan-i-Khanan, given to him by Emperor Humayun. Bairam Khan was an intellectual, a poet and a

cultured man with great military and administrative skills. From the beginning of his service, he was a faithful companion of Emperor Humayun and because of his loyalty and bravery, he came to be the regent of Akbar. 8

The family of Bairam Khan came into the service of Babur sometime after A.D. 1505, and Bairam Khan, at the

age of 16, was associated with Prince Humayun. Later, the alliances grew between the families with several

intermarriages. The third essay in the book, by Iqtidar Husain Siddiqui, gives a detailed account of Bairam Khan and the life of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan and their associations with the family of the Mughals.

Siddiqui’s account is very important to the overall intention of this book, for it helps us place Rahim, his family and his ancestry in the context of Mughal history, even before Babur’s conquest

of India. The direct association over four generations—Babur to Shah Jahan—and previous associations with the Timurid princes locates ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan in the inner circle of the

Mughal royal family. However, it was not just that. Their loyalty and bravery, along with their well-groomed etiquettes and

highly educated background, made them perfect companions and tutors of the Mughal princes. As mentioned earlier, Bairam

became the regent of Akbar when he ascended the throne at the age of 13. Siddiqui, in this book, with references from

primary Persian sources, gives us intriguing details of early

Mughal history with Bairam Khan-i-Khanan and ‘Abdur Rahim

Khan-i-Khanan in the midst of it.

He was one of the Nine Gems of Emperor Akbar. Raised in the pluralistic environment of Emperor Akbar’s court, ‘Abdur Rahim

acquired proficiency in Persian, Arabic and Turki. Impressed by

his learning, sophisticated manners, and humanism, Akbar conferred upon him the title Mirza Khan and appointed him the teacher of the crown prince Salim. Akbar also married his foster sister and daughter of Shamsuddin Muhammad Atka 9 to

‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan.

Rahim developed a refined taste and sensibility for poetry in different languages. He eventually turned out to be a

versatile poet, prolific writer, consummate scholar and an able administrator. He was also interested in mathematics, astronomy

and scholasticism. Of the works by him, only Bāburnāma is

extant. Equally important was his role as a patron. His library

was a rich store of learning, open to scholars. Some precious books that once belonged to his collection are now found in prestigious collections across the world. Khan-i-Khanan is also credited with the

construction of beautiful buildings, canals, tanks and pleasure gardens in Agra, Lahore, Delhi and Burhanpur.

Sixteen-year-old ‘Abdur Rahim accompanied Emperor Akbar on the Gujarat campaign in 1572. The painting depicts the Emperor parading into the impressive Surat fort after his victory. Opaque watercolour and gold on paper; 31.9 x 19.1 cm (painted surface), 33 cm x 20.2 cm (painted surface and borders); Farrukh Beg (maker); Mughal, c. 1586–89 (made). Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS.2:117-1896. ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

(Facing page) Unlike bhakti poets Kabir and Ravidasji, Rahim’s poetry adapted devotional imagery within courtly settings. On the other hand, verses by the former were rooted in popular Bhakti traditions in the 15th–16th centuries, and are widely sung to this day. Mughal, Jahangir period; Paper; 18 x 25 cm; c. A.D. 1620–30. National Museum, New Delhi. Accession Number: 79.444.

The most important monument constructed by him is the tomb he built for his wife. The tomb, together with

Humayun’s Tomb, served as a source of inspiration for the architecture of the Taj Mahal at Agra.

Eva Orthmann’s contribution in this book goes on to explain the patronage system that existed in the sub

imperial courts of early Mughals typical “of a high-ranking Mughal office holder (mansabdār)” like ‘Abdur

Rahim Khan-i-Khanan, but, she continues to emphasize that “…he was nevertheless singular because of both the extent of his patronage and generosity”. Like Siddiqui, Orthmann draws from Ma’āsir-i-Rahīmī to

expound on the patronage process at his court and to call out the numerous great scholars and poets that

‘Abdur Rahim employed. Besides being very fond of books and the arts of book, he was patron to many artists of miniature painting and scribes. His court and kārkhānas were so desired—as he handsomely paid

the scholars, poets and artists—that some left the imperial court to benefit from his patronage. ‘Abdul Baqi

Nihavandi, the author of Ma’āsir-i-Rahīmī, left the administration of Shah Abbas (r 1588–1692) of Persia to seek the patronage of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan on the suggestion of Mughisuddin Asadabadi. 10

The next essay by Sunil Sharma translates an extract from the third volume of Nihavandi’s biography of Rahim,

Ma’āsir-i-Rahīmī. ‘Abdul Baqi Nihavandi’s voluminous work has not only been an important contribution

to the study of Rahim’s life and patronage, but it has also been a source book for the understanding of Rahim’s

court and the “biographies of 191 persons” who worked at his court, as cited by Orthmann. As Sharma states: “From the early Mughal period, the only equivalent of such an extended glowing tribute to a powerful

personage is Abu’l Fazl’s (d 1602) equally massive biography-history of the Emperor Akbar, Akbarnāma.”

The translation by Sharma in this book provides a glimpse into Rahim’s court. He points out that the biography concentrates mainly on the Persian personalities associated with Rahim’s court and Rahim’s

Persian poems, as to be expected of Nihavandi who had just come from Iran. However, it is important

to note here that he affirms Khan-i-Khanan’s natural gift with various languages “that he used in his daily communications with different communities of people, official correspondence to other courts, and in

composing his own poetry”.

Rahim, being a poet and a lover of books, employed many scholars and poets with whom he personally

interacted. Several worked in his grand library. As Orthmann points out, Rahim personally oversaw the collection and the preservation of his books. The essay by Chander Shekhar, “From the Pen of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan”, tells us about his personal involvement with the books from his collection.

Shekhar’s essay catalogues and analyses a few of his notes on the flyleaf of the manuscripts. The importance and value of the books in his library is reinstated by the endorsements of imperial owners such as Jahangir and Shah Jahan.

His love for books also came from his love for poetry. Mehr Farooqi and Richard Cohen in their essay titled “Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan and his Worlds of Poetry” compile an overview of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i

Khanan’s literature in Persian and Hindavi, which, according to them, seem as if they are by two different

personalities. Like all the authors in this collection, they too question the lack of his Hindavi poems in Nihavandi’s voluminous biography—the most essential resource record—of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan,

which was commissioned by Khan-i-Khanan himself. When, especially, it even includes Persian works of

poets only remotely connected with his court. The bigger question they raise is why Khan-i-Khanan himself did not have his Hindavi works included. Was it considered lesser than the Persian works in the cultured

courts of the Mughal and, thus, not worthwhile?

Here again we see a similar situation with Amir Khusrau’s Hindavi verses. Khusrau himself mentions in the autobiographical preface of his dīvān that he wrote as many verses in Hindavi and Persian, but never

compiled a dīvān of his Hindavi verses. He was very careful and particular about documenting all his

works. So much so that he recorded the number of words in his manuscripts to ensure there was no room

for the careless scribes to make errors. The question again is this: did he consider his Hindavi works not worthy literature in the glory of the Persianate cultures of the Sultanate courts of 13th–14th century? It is

understood that Persian, and the patronage of anything originating from the Persianate world of Medieval Islam, was cherished more than the vernacular and the indigenous.

Amir Khusrau, who was born of an Indian mother with Hindavi as one of his mother tongues, wrote

extensively, glorifying the facets of India over that of Khurasan and other grand centres of the Islamic world to counter the Sultans’ perceptions, and thus their patronages, of the foreign Persianate over the Indo

Persianate. An attempt, perhaps, to reinstate himself in the world of Persianate literature. The other reason,

which is apparent in Khusrau’s case, Rahim did not include his Hindavi verses coloured with Hindu divinities and imageries was to avoid the obvious confrontations with the Islamic vigilante who were on an extra watch due to the shift in the religious sentiments of Akbar.

These may have been the reasons for not finding any traces of Rahim’s Hindavi verses in Mughal records.

However, fortunately, the rich flavours of the Indic traditions, language, music, and the other creative and religious expressions continued to co-exist, not only among the populace, as commonly mentioned in the

khānaqāhs of the Sufis, but in the courts of the nobles and emperors, of both Sultanate and Mughal eras of the Muslim rule. In the 700 years or so of the Muslim rule, the Indic traditions flourished independently and with the freshness of syncretism between the two cultures. The polity and the culture of Mughal Emperor

Akbar’s court and his nobles, here referring specially to ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan, became the crucible

of that interaction. The recent work of Audrey Truschke expounds on the exchange between the Sanskrit works of the pandits with that of the ‘ālims of the Persian and Arabic. 11 Here, in the process of translating

the scriptures and epics, discussions were happening not just in the worlds of literature and arts but in the world of religions. Akbar initiated his own sect, Dīn-i-Ilāhī, where he intended to put the best of India’s

beliefs and practices together. Major scriptures of the Hindus were translated into Persian, accompanied by exquisite miniature paintings. As mentioned earlier, ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan was given the privilege to make a copy of the imperial manuscript of Persian Rāmāyana commissioned by Akbar. John Seyller, a

scholar of Mughal paintings, beautifully documents the manuscript expanding on Khan-i-Khanan’s grand patronage of visual arts.

To summarize, ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan wrote verses in Turki, Persian, Hindavi and Sanskrit. Nihavandi

does not include Rahim’s Hindavi poems, but he refers to them in his biography. Sharma explains that he

mainly wrote about his “countrymen” and their biographies and poetry. Farooqi and Cohen further infer

that he began working on the biography soon after coming from Iran and that he did not know Hindavi and was unaware of the significance of Rahim’s Hindavi poems. Yet, it was Rahim’s Hindavi poems that gave him his legend.

None of Rahim’s Hindavi poems in original survive from his time, though several later tazkiras mentioning

that he composed in Hindavi. 12 This brings us back to the beginning of this book: the revival of Rahim through his Hindavi poems. It needs to be noted here that, as Raghavan alludes to in his conclusion, while

there was this ardent drive in earlier 1900s to re-produce Rahim’s Hindavi verses highlighting their Indic

idioms as opposed to Persian metaphors in order to link him to the soil of the nation rather than that of the conquerors, there was a similar push to expose his Persian works to “enigmatically… [pass] over Rahim’s

Hindi poetry, or to… [contest] the provenance of his [Hindu] devotional verses”. However, with the flow

of time and the directives of modern India, Khan-i-Khanan’s Persian verses did not “stick to the soil” and

remained in the libraries and books of the scholars. Farooqi and Cohen show in their essay that there were

studies that projected Rahim’s Persian works as comparable to the masters of Persian poetry. They also note that Shibli Nomani wrote in Sher’ul Ajam “…if he [Khan-i-Khanan] had taken to write [Persian] poetry as a profession he would be no less than Urfi or Naziri”.

Thus, the first part of the book ends with two essays on Rahim’s Hindavi poems in the metres of barvai

and dohā to present the substance of them through translations with annotations of a few selected verses. The sources of the authors are different due to the fact that none of Rahim’s Hindavi works survive in

their original forms. Most of the ones we know came about in prints in the 1920s. Raghavan’s essay in the

beginning of the book presents a clear chronology of Rahim’s Hindavi poems. He records that over a short

span of time, there was a steep rise in the Hindavi verses that were published. In Khānkhānanāma by Munshi Deviprasad, there are only 40 dohās of Rahim with the mention that there are about a hundred more. Later,

Brajratna Das, in his Rahiman Vilās, reproduced 289 dohās. After these, there have been an abundance of publications in Hindi, which build on them. Most of the Hindi verses in this book have been taken from the later publications. Different authors have different books as their sources and, thus, there are variations in the verses. Attempts have been made to call out the sources of the verses where used.

Rupert Snell introduces Rahim’s barvai verses explaining its structure and use. In doing so, he makes the

comparison with the other barvai poet of Rahim’s time, Tulsidas, who wrote the BarvaiRāmāyana. Snell tags

the style as “intimate miniature verses in a rare and tiny metre”. His analyses “rest on their aesthetic function

rather than their hereditary history or subsequent influence”. He introduces Rahim’s two barvai poems,

Barvai Nāyikā Bhed and Barvai. The former is the tradition of codifying typical physical manifestations of the

heroine’s emotions and acts in given situations and roles—a lover, a wife, a mistress. The latter is laden with Krishna bhakti references. He ends the essay with the translations of selections from both compositions.

(Facing page) Illustrated folio from the Persian translation of Valmiki’s Rāmāyana commissioned by ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan. The image depicts Ram, Lakshman and Vishvamitr rest at the hermitage of Kama at the confluence of the Sarayu and the Ganges. The translation followed that of an imperial copy. Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on paper, in modern bindings; 27.5 x 15.2 cm; Artist: Ghulam ‘Ali. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1907.271.1-172 vol-I: folio 34 recto.

The next chapter by Allison Busch, in the given structure, presents a set of Rahim’s compositions—dohās

and barvais with annotations and translations. Busch beautifully provides insights into the reading of the

verses of Rahim from his Nagarshobhā and Nāyikā Bhed to get a deeper understanding of them. Although,

as she mentions, the appreciation comes with the pre-knowledge of the literary tradition, with Busch’s help

one can get to enjoy the nuances of Rahim’s metaphors and imageries. Busch unpacks the brief yet richly

loaded verses and guides the reader to the emotional and physical states of various heroines. Explaining the

usage of languages, metaphors and imagery, the essay provides an accessible entry-point into the pleasing world of medieval Hindi poetic traditions.

The 11 essays in the first part of the book essentially expose the core intention of the festival, the multifaceted legacy of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan elaborating the many characters of Rahim as called out in the sub-headings of the book’s title: Statesman, Courtier, Soldier, Poet, Linguist, Humanitarian, Patron. His compassion, his patronage and his poems, as put by Farooqi and Cohen, find their expressions

“within the hybrid cultural environment of his time, an environment which facilitated interaction between

[religions, cultures, languages, arts, intellectuals] poets and circulation of their [traditions and] texts, regardless of their religious identity or association”. As mentioned above, and emphasized by Eva Orthmann

in her essay, these attributes were underpinned and made possible by the career of Khan-i-Khanan as a

prominent statesman.

In the chapter by Iqtidar Husain Siddiqui, the history of Rahim’s life beginning with Bairam Khan, his father, is

presented with references from Persian primary sources ranging from Akbar’s court historians to chronicles

commissioned by Shah Jahan and Mughal political biographies. His work refers to important sources such

as the Akbarnāma, Tuzuk-i-Jahāngīrī, Shāh Jahānnāma, Ma’āsir-ul-Umarā, Zakhīrat-ul-Khwanīn and Ma’āsir

i-Rahīmī. The essay throws light on the side that largely gets ignored under the weight of Rahim’s literary contributions: Rahim as an able courtier and a key Mughal general.

The chapters on history and patronage paint the pluralistic canvas of Akbar’s darbār within which the talent

and mentality of Rahim flourished. It highlights the factors that enabled Rahim to commission and produce

Sanskrit and Hindi masterpieces in a Persianate court and further outlines the canvas of their revival and

popularity. They flesh out the process through which the Mughal court developed a multifaceted intellectual and imperial framework, rooted in political pragmatism as well as courtly aesthetics, and then locate Rahim within it.

Siddiqui along with Orthmann gives a glimpse into ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan’s generosity and patronage, which went beyond the conventional norms of the Mughal imperial and sub-imperial courts. His generosity spurred many legendary anecdotes and his patronage left many wonderful remnants; unfortunately, some in ruins and lost to the ravages of time. Shekhar presents Rahim as a patron of arts, and some of the manuscripts from his library that can be found in museums across the world. The essay refers to him as

connoisseur and collector of important literary and artistic masterpieces. Sharma’s translation of an extract

from Nihavandi’s biography of Rahim gives us an opportunity to get a first-hand view of the functioning of his court and those who were employed by him.

The chapters on his poetry summarize the literary works of Rahim from Persian to Hindi. They comment on

the subjects and kinds of his literature as they continue into present times. This section of the book includes

some of his popular dohās along with some scarcely known barvais to present a cross-section of the subjects

of his Hindavi compositions. The verses are presented with transliterations, translations and annotations with references to subjects, symbolisms and metaphors.

The first essay of the part two of the book by Ratish Nanda provides historical and architectural narratives

to several buildings built by ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan. It focuses on the tomb of his wife that he built

and where he was buried. He died an old man, as Khan-i-Khanan, in the beginning of the reign of Emperor

Shah Jahan. The architecture of Khan-i-Khanan’s tomb, as it is commonly known, is a fine example of Mughal architecture and is seen as a precursor to the Taj Mahal at Agra. It is the conservation of this building that

led to Celebrating Rahim—the book and the festival.

On the one hand, Celebrating Rahim presents ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan as a statesman, courtier and soldier. On the other hand, it illustrates his contribution as a poet and a patron. The festival, in all,

demonstrates his humanitarian and pluralistic approach to art, life and governance, integral elements of the Mughal Era. No doubt, in the span between ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan of Akbar’s and Jahangir’s eras and the Rahim of the 1920s—300 years and more—there have been creations and re-creations of him and

his attributions, and his contributions. The Mughal annals presented him more as a soldier and governor than as a patron and a poet. It is mainly in the Persian and Sanskrit writings of those employed by him

that his patronage and generosity received mention. It is stated that there are more qasīdas dedicated to

him than Akbar, and his biography in volume equals that of Akbar’s. ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan begins

to be unravelled with a drive again in modern India after centuries of there being minimal records of him.

In case of Amir Khusrau, his verses and anecdotes remained alive and continued to be sung with all the variations included throughout within the lineage of Qawwāl Bachche, who claim him as their master. In case of Khan-i-Khanan, his verses remained in the pages and never got sung or recited. Thus, they remained

mostly unknown. The insights and beauty of his Hindavi poems guaranteed their popularity, but only within

the realms of books and conversational quotes. When compared to the poetry of Kabir, Surdas and Tulsidas, in whose genre and style Rahim sets his poems, there are no traditions of his dohās being part of any

recitation or singing traditions. Neither do they lend themselves naturally to the rhythm of music since, it seems, they were not written to be recited. They needed modification and adaption to be included among

recitable verses.

The second part catalogues the performances, with translations and audio links, performed during the festival. The concerts—classical and folk—give life to his popular verses, with rāgas and vernacular

compositions exemplifying the depths of his poetry and his understanding of life; the musical narrative tells the story of his life and his humanity; and the dance performance demonstrates his treatise on nāyikā

(heroine) and shringār (love). The events were composed and choreographed for the first time for the festival. The selected artists were especially commissioned to develop musical compositions, plays and

dance performances based on Rahim’s poetry and his biography.

Project Note:

Conservation of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan’s tomb and his legacy, supported by InterGlobe Foundation,

is one of the key objectives of the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative implemented by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC). The Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative is a unique urban renewal programme where conservation objectives are coupled with environmental development, socio-economic development

and cultural revival. It is a not-for-profit public-private partnership model aimed at tangible and intangible heritage conservation with subsequent improvement of quality of life for the local communities.

1. Chhotubhai Ranchhodji Naik, ‘Abdur Rahīm Khan-i-Khānān and his Literary Circle (Ahmedabad: Gujarat University, 1966), 29, fn1.

2. Annemarie Schimmel, “A Dervish in the Guise of a Prince: Khan-i-Khanan Abdur Rahim as a Patron,” in The Powers of Art: Patronage in Indian Culture, ed. Barbara Stoler Miller (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1992), 203.

3. The completion of half a couplet of Tulsidas by Rahim and their close friendship is a widely popular lore; the Manas Mandir at Varanasi has the couplet inscribed on its walls adding another layer to this belief.

4. A thorough study of the library holdings and book-production in the sub-imperial atelier of ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan has been made by John Seyller, Workshop and Patron: The Freer Rāmāyaṇa and Other Illustrated Manuscripts of ‘Abd al-Rahim (Zurich: Artibus Asiae Publishers, 1999), 50–63.

5. Audrey Truschke, Culture of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

6. Seyller, Workshop and Patron, 81–249.

7. Gujarat (1583); Sindh (1592); Deccan (1593).

8. Abu’l Fazl, Akbarnāma, Vol. I tr. H. Beveridge (Delhi: Low Price Publications, 2002), 657–58.

9. Shah Nawaz Khan Shamsamuddaula, Ma’āthir-ul-Umarā, Vol. II (Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1952), 156–60.

10. Naik, op. cit., 375–78.

11. Truschke, 104–05.

12. The political biographies from the 17th and 18th century: Zakhīrat-ul-Khwānīn by Shaikh Farid Bhakkari, Ma’āthir-ul-Umarā by Shah Nawaz Khan, and poetic biographies like Kalimāt-us-Shu‘arā mention Khan-i-Khanan briefly.

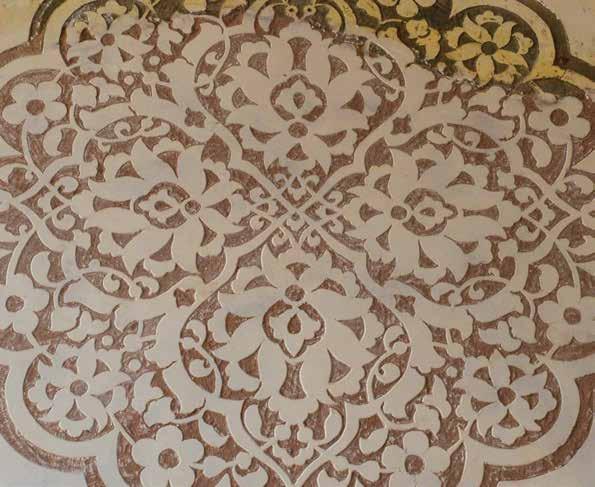

(Facing page) Traditional craftsmanship forms an integral part of the conservation process. The image shows the transfer process of the pattern on the wall for incised plasterwork, ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan’s tomb, New Delhi.