21 minute read

The Revival of Rahim in Modern India T. C. A. Raghavan

THE REVIVAL OF RAHIM IN MODERN INDIA

T. C. A. Raghavan

Advertisement

‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan (1556–1627), the only son of Akbar’s regent, Bairam Khan, is a prominent figure in Mughal political, military and intellectual history during the reigns of Akbar and Jahangir. Rahim’s political achievements include the re-establishment of Mughal control over Gujarat after a major rebellion (1584), the conquest of Sindh (1592), campaigns in Berar and Ahmednagar in the 1590s and a long tenure as Governor of the Deccan in the 1590s and in the first two decades of the 17th century. Like many prominent families at the heart of the imperial system, his family, too, faced annihilation on account of internecine conflicts within the royal family and the consequent civil wars. Rahim’s last days were spent as a prisoner of the very court he had served with distinction, and he was also to see the physical destruction of his family at the hands of feuding princes.

Rahim was at the centre of the court’s patronage of Persian literature. His translation of Emperor Babur’s

memoirs from Turkish into Persian in 1589 is a milestone in Mughal literary history. Many Persian poets

gravitated to Rahim, and his personal library was a centre of patronage for calligraphers, book binders and painters. However, he also stands out in areas outside the traditional parameters of intellectual and political

achievement of the Mughal nobility in India and has come down to us as a Hindi poet of distinction. Major works attributed to him range from mixed Sanskrit and Persian verses on astrology, as in Khet Kautukam;

eight verses in a traditional bhakti idiom on devotion and attraction to Krishna of the gopīs of Vrindavan,

as in Madanāshtaka; 1 sensuous and erotic verses in Nagarshobhā, 2 Shringār Sorthā; 3 and those in a nāyak

nāyikā bhed format, as in the Barvai Nāyikā Bhed. 4 The latter is an important work because it is the first to

use in Hindi the Sanskrit genre of nāyak-nāyikā bhed and also the first to use the barvai 5 couplet. Rahim is,

however, best known today for his collection of dohās, 6 pithy reflections on daily morality and ethics, which

remain a staple in school textbooks of Hindi for their simplicity of language and the down-to-earth quality

of the advice conveyed. 7

Despite the extensive documentation of Rahim’s life and career in contemporary Persian sources, there is scant detail in them of his Hindi poetry. His literary corpus, as we know it today is largely the result

of a wide-ranging research into his life and writings in the late 19th and early 20th century by scholars and protagonists of the Hindi movement. By the mid-20th century, Rahim was regarded as both a

secular exemplar as well as a philosopher general of Mughal India. Popularly regarded as one of Akbar’s

navaratnas, he is the Mughal noble representing Akbar’s India and the consummate product of the

Emperor’s bold experiment to forge a new communal and religious consensus in India.

This paper examines how Rahim, the historical figure and the poet, was engaged by Hindi litterateurs and historians. In the 19th century, as we shall see below, there were enigmatic failures to encounter Rahim’s poetry when most expected. From the early 20th century, however, we encounter a steady expansion of knowledge about him as a determined effort to reconstruct his literary personality as a social and national icon was undertaken.

The Historical Rahim

Of all the significant milestones in preserving Rahim’s history, the Ma’āsir-i-Rahīmī of Maulana ‘Abdul Baqi Nihavandi (1570–1637) occupies the foremost place. 8 It is a contemporary source on Rahim and on the Persian poets and scholars he patronized. Thereafter, Rahim features in a biographical dictionary called

Zakhīrat-ul-Khawānīn, which enlists Mughal nobles, written some 25 years after his death. Some of its descriptions were based on eyewitness accounts, and from these, we get a flavour of Khan-i-Khanan’s

personality. The Zakhīrat itself was a source for another biographical dictionary of Mughal nobles, Ma’āsir

ul-Umarā, dating to the 1740s. Numerous other Persian histories of the period beginning with Akbarnāma

by Abu’l Fazl (1551–1602) and Muntakhab-ut-Tawārīkh by ‘Abdul Qadir Badauni (c.1540–1615) also contain rich biographical details on Rahim. All these Persian sources mention his patronage of literature and that he composed poetry in Arabic, Persian and Hindi, although no examples are cited of his verses in Hindi. 9

An early reference to Rahim’s Hindi verse is in Kāvya Nirnaya (The Verdict on Poetry), a Braj Bhasha work

composed in 1746 by Bhikharidas. This work has some introductory verses classifying prominent poets and it “…distinguishes four (overlapping) categories of poets: those such as Tulsidas and Surdas, distinguished for

religious merit; those rewarded by patronage—Kesavdas, Bhusan, and Balbir; those seeking fame—Raskhan and Rahim; and the scholastic poets, Tos, Rasraj, Raslin and himself”. 10

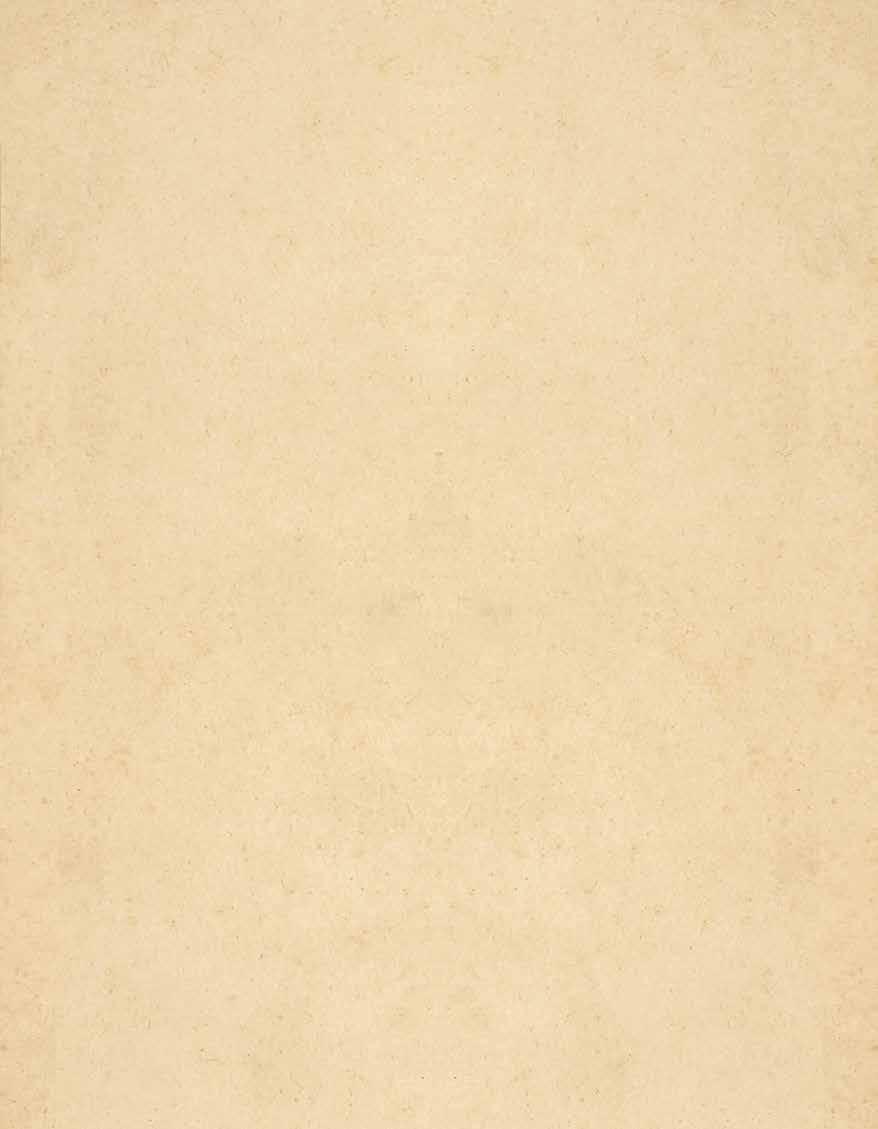

(Previous page) Bairam Khan, father of ‘Abdur Rahim and regent of Emperor Akbar, watching the latter learning how to shoot (1555). ‘Abdur Rahim also went on to tutor Emperor Akbar’s son, prince Salim. The illustration is contained within the first volume of Akbarnāma which describes Emperor Akbar’s Timurid ancestry and the history of his grandfather Babur (1483–1530) and father Humayun (1508–56). The margins of the opening have been decorated and illustrated in Jahangir’s reign. Opaque watercolour; 18.7 × 33.5 cm; 1603–04. British Library, Akbarnāma Vol.I, Or. 12988, f. 158a.©The British Library Board (Or. 12988, f. 158a).

Bhikharidas’s description, although brief, does shed light on contemporary evaluations of Rahim. “Seeking fame” is certainly a categorization with some value. Ma’āsir-i-Rahīmī is one of the few panegyrics inspired

by and devoted to a Mughal noble rather than a monarch. The work was obviously composed at Rahim’s

own instruction and evidently designed with an eye to both his contemporary and posthumous reputation. Similar purposes were also achieved by the large volume of verses composed in his praise by Persian,

Sanskrit and Hindi poets. In this context, striking also is the massive tomb he built for his wife in Nizamuddin, New Delhi. It is usually referred to as Khan-i-Khanan’s tomb, but he was buried in it only later. Amongst the

numerous structures that constitute Mughal heritage in India, this is one of the very few built in memory of a wife, perhaps rarer still if we ignore queens and princesses. In Burhanpur, a provincial capital in Mughal

India, numerous structures attributable to Rahim still dot the landscape—public baths, an underground water supply system, mosques and the tomb of his son, Shah Nawaz Khan.

A 19th-Century Enigma

Rahim’s Hindi poetry was noticed in Kāvya Nirnaya, a century and a quarter after his death. Yet, this cannot

be taken to imply that these verses were in any sense popular or even known outside a small fraternity of scholars. Certainly, we have little evidence of a widespread familiarity with Rahim’s verses in the early 19th

century. For example, Thomas Broughton, a British Army officer, who spent many years in India, compiled

a collection of poems and songs popular amongst the soldiers in his command. Selections from the Popular Poetry of the Hindus was published first in 1814. 11 It includes a large sample of verses from numerous poets.

We have samples from Surdas, Keshav, Bihari, Giridhar, Kaviray and Mandan, apart from verses of lesser known poets. However, there is no Rahim. On the other hand, other poets absent in the anthology include Tulsidas and Kabir. Broughton’s collection, therefore, is not fully representative, but this lack of reference is nevertheless significant, given Rahim’s absence elsewhere. Another influential collection was William Price’s

Hindee and Hindoostanee Selections (1827). The poets included are Kabir, Tulsidas, Gang, Kesavdas, Mira Bai,

Parmananddas and Haridas Swami. 12 The themes of the selections are such that some inclusion of Rahim’s

verses would have been expected, but once again, we do not encounter him.

We could look also at two early examples of Hindi as it emerged in the 19th century and at the beginning of its great divide with Urdu. Lalooji Lal (1747–1824) was described in later years as having “…practically newly invented modern Sanskritized Hindi by excising ‘alien’ words from the mixed Urdu language of Akbar’s camp

followers…” as also having a pioneering role in the crafting and identifying of Hindi as the “language of the

Hindus”. His collection of Hindi poetry, Sabhā Vilās (1817), has a dohā of Rahim. 13 This suggests that at least

some of his verses were still in circulation in the early 19th century, scattered across different manuscript

collections or oral traditions, which Lalooji Lal would have had access to. Yet, the presence of this single verse in Sabhā Vilās does not suggest any great familiarity with Rahim or his work. The fact that Sabhā Vilās

included a whole section entitled barvai would lead us to expect a larger representation from Rahim, since

this was unquestionably a verse form that he is well known for writing in. Yet, none of the barvais in the

Sabhā Vilās can be ascribed to Rahim.

From Lalooji Lal, let us move to 19th-century Raja Shiva Prasad, another seminal figure in the history of the emergence of modern Hindi literature. 14 Amongst Raja Shiva Prasad’s influential works is an anthology

who, following Saroj, says, “It is difficult to distinguish between the works of this poet and those of his illustrious namesake.” 18

The Misra Bandhu

We encounter Rahim in greater detail in another important anthology of poetry, Misra Bandhu Vinod

(1913). Vinod was composed by Ganesh Bihari, Shyam Bihari and Sukhdev Bihari, three brothers known collectively as the Misra Bandhu and distinguished for writing everything they did together. 19

Vinod has a detailed entry for Rahim and summarizes the extant knowledge of him in the early 20th

century. It also has an unambiguous assertion that “despite being a Muslim he was a complete devotee of Krishna and Ram”. However, in its knowledge of Rahim’s works, we find that the Misra Bandhu Vinod is

neither very comprehensive nor accurate. Nagarshobhā and the barvais, apart from those in the Barvai

Nāyikā Bhed, are prominent omissions in works attributed to Rahim. The Rāsapanchādhāyī is wrongly attributed to Rahim, as it was actually the work of the Krishna-bhakt poet Nanddas in the 1580s.

Clearly, over the 19th century, the complete Rahim was yet to emerge. But some knowledge about him was spreading and had advanced incrementally over the century. In the early decades of the 20th century,

three seminal contributions would fill in greater historical and literary detail. This part-historical, part-literary endeavour was prompted by and took place amidst a wider nationalist and linguistic ferment in north India, in the late 19th and early decades of the 20th century.

The Rise of Rahiman

The Nagari Pracharini Sabha, or the Society for the Propagation of the Nagari Script, was the crucible

of this ferment. The establishment of the Sabha in 1893 in Varanasi constitutes a milestone in the

promotion of Hindi and its literature as a whole and not just the movement to establish the primacy of the

Devanagari script, which was the society’s declared aim. The Sabha drew to it a body of committed and

gifted scholars and public personalities. It led the movement for the official recognition of Hindi and its use in government and legal proceedings. Simultaneously, it conducted searches for old Hindi manuscripts

and published numerous books on history and literature, including compilations of the great Braj Bhasha

and Avadhi poets of medieval India. The principal objective was to establish the antiquity of Hindi and, by subsuming within it older Braj Bhasha and Avadhi literary traditions, demonstrate the richness of its literature and the seamless continuity of its traditions from ancient times. The demand for the recognition

of Hindi as the principal official and literary language had, however, integral to it the parallel implication of the displacement of Urdu. The divide between the two grew over the second half of the 19th century

and progressively crystallized in the 20th century, as literary competitiveness was increasingly influenced by growing communal tensions.

The three protagonists I detail now, in the resurrection of the literary Rahim, were all intimately

associated with the Nagari Pracharini Sabha. Henceforth, the elevation of Rahim due to their efforts becomes indistinguishable from the larger Hindi movement, and indeed from the great divide between Hindi and Urdu.

Munshi Deviprasad

Munshi Deviprasad came from a family of Kāyasthas (a Hindu scribal

caste), a long-time resident of Delhi. In the service of the Mughal court,

their knowledge of Persian, accountancy and calligraphy defined their status. The decline of the Mughals witnessed the dispersal of the family to smaller princely states. Deviprasad was to join the service of Tonk State

but had to leave, apparently on account of his advocacy of Hindu causes.

The efforts of his family led to him receiving an offer for a post in Jodhpur in 1879, where he remained until his death in 1923. 20

The Jodhpur government employment did not wholly define Munshi’s activities or range of interests. Social reform, the advancement of the status of women and an abiding interest in historical research and antiquities broadly formed one side of his preoccupations. The pursuit of Hindi and its propagation formed the other. In the commingling of history and literature, we can see the full range of Munshi’s endeavours. He wrote some 50 books and almost a hundred essays in Hindi. His most important historical works include Shāh Jahānnāma, Aurangzebnāma, and the lives of Sher Shah and Akbar. Munshi Deviprasad was equally a prodigious writer in Urdu, with some 27 publications in it. These include several histories, writings on education and social reformist texts. His earlier works were principally in Urdu, before he moved to using both the Urdu and Devanagari scripts and, finally, only the latter. In some sense, then, the move from the “Muslim” princely state of Tonk to the “Hindu” Jodhpur was more than geographical. The advancement of Hindi and Devanagari, both locally and nationally through the Nagari Pracharini Sabha, was to become an inseparable part of the Munshi’s personality in Jodhpur.

Interest in history with a commitment to the establishment of Devanagari Hindi as the national language of India is common between Deviprasad and many other historians of the time, notably, Gauri Shankar Ojha, Visvambar Nath Reu and Kasi Prasad Jaiswal. The establishment of Hindi in the Devanagari script was, in the eyes of its protagonists, equally an act of historical research and discovery as one of political and public advocacy. The search for old manuscripts, establishing the identity and biographical details of poets, tracing

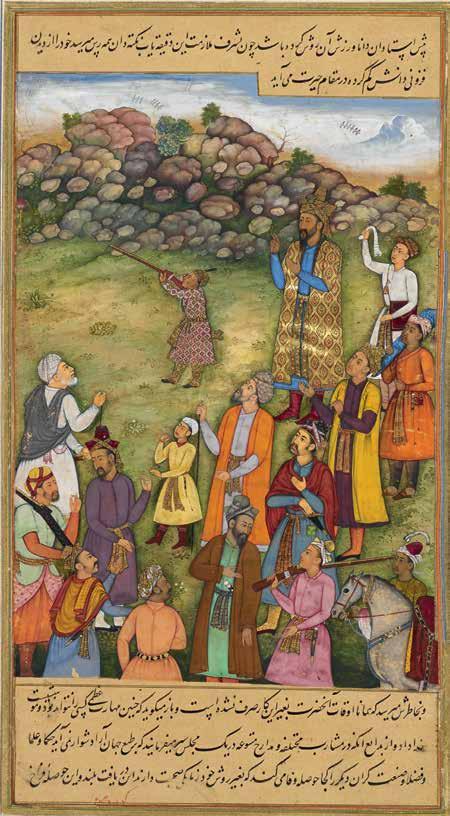

‘Abdur Rahim’s interest in literature, his patronage of poets and translation activities was influenced by the vibrant culture at the Mughal court. An illustration from the imperial Razmnāma depicts the Mughal Emperor’s translation bureau where Hindu and Muslim scholars collaborated to translate Mahābhārata from Sanskrit to Persian. Opaque watercolour, ink and gold on paper; 30 x 17 cm; Artist: Dhanu; 1598–99. Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department, mcom00181, Call Number: Lewis M18; Philadelphia, PA.

(Previous pages) Akbar, Todar Mal, Tansen, Abu’l Fazl, Faizi and ‘Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan in a court scene (16th century A.D.). Panel No. 45, Outer Gallery of Parliament House, New Delhi; Artist: M. K. Sharma, Jaipur; Artist Supervisor: O. P. Sharma, New Delhi; Image courtesy: HarperCollins Publishers (India).

that he did not do for any other language… Rahim did not see Hindi as being lesser than Arabic, Persian,

Turkish…”. There is then a logical extension to “From the name of incarnations, the glory of Mahadeva and Ganga…etc., it becomes clear that ‘Abdur Rahim’s sentiments towards Hindus were not one of dislike. There was great respect for the Hindu religion and he was a follower of Vaishnavism and a devotee of Krishna…”. 26

Language devotion thus fused with religious identity, in much the same way as we saw with Brajratna Das.

The Decade of Rahim and Later

Brajratna Das’s Rahiman Vilās and Mayashankar Yajnik’s Rahim Ratnāvali are only the most prominent and

comprehensive of the many works that have led to the 1920s being described as the “decade of Rahim”. Through the 1920s, we have an explosion of titles on Rahim. Rahīm (Allahabad, 1921) by Ramnaresh Tripathi,

Rahiman Chandrikā (Benaras, 1924) by Ramanath Lal “Suman”, Rahiman Shatak (Mathura, 1924) by Navanita

Chaturvedi, Rahīm Kavitāvali (Lucknow, 1926) by Surendranath Tiwari, Rahiman Shatak (Benaras, 1926)

by Lala Bhagvandin, Rahiman Shatak (Allahabad, 1927) by Siva Sankara Misra, Rahiman Vinod (Allahabad,

1928) by Pandit Ayodhya Prasad Sharma, Rahiman Lālitya (Calcutta, 1928) by Anantsharan Ojha “Lalit”,

Rahiman Sudhā (Patna, Allahabad, 1928) by Anup Lal Mandal, and so on. This plethora of titles had many impulses, apart from the general nationalist mood sweeping the country—the expansion of Devanagari

publishing houses, the commercial demands of a growing market for books to be used as texts in schools and colleges and the requirements of academic curricula for which Rahim’s dohās, with their moral aphorisms

in Hindi, were eminently suited. Not surprisingly, many of these publications concentrate almost entirely

on Rahim’s dohās.

This abundance of books in the 1920s gave certain completeness to characterizations of Rahim as a symbol

of Indianness. Rahim as a literary or historical figure is thus overtaken by Rahim as national icon, and this

status was derived in considerable measure due to his ethical and devotional verses. An illustration of this

is found in a work of Seth Govind Das, a prominent political and literary figure in central India between the

1920s and the 1970s. Govind Das combined an active political career in the Indian National Congress with an equally strong commitment to the cause of Hindi as India’s national language. Amongst his many works

of literary criticism, drama, historical fiction and poetry is a play entitled Rahīm. First published in 1955, the play presents an assessment of Rahim’s life as one pulled by contradictory impulses—a desire for political

and military power befitting an important courtier, but also the yearning for the life of a recluse who finds

fulfilment in religious devotion and literature, in brief emulating the life of Tulsidas. For Govind Das: “Despite being a true Muslim, Rahim was a devotee of Ram and Krishna and the spirit of this devotion suffuses his

entire poetry… Although a Muslim, Rahim was a real follower and practitioner of Indian culture (Bhāratiya

Sanskriti). Because of this, his heart had tolerance, and for this reason he viewed Hinduism and Islam, Hindus and Muslims equally.” 27

In all these works, Rahim’s devotional poetry is viewed as an indisputable evidence of his Indianness. As communalism, separatism and Partition took their toll on the national psyche, the synthesis believed to have

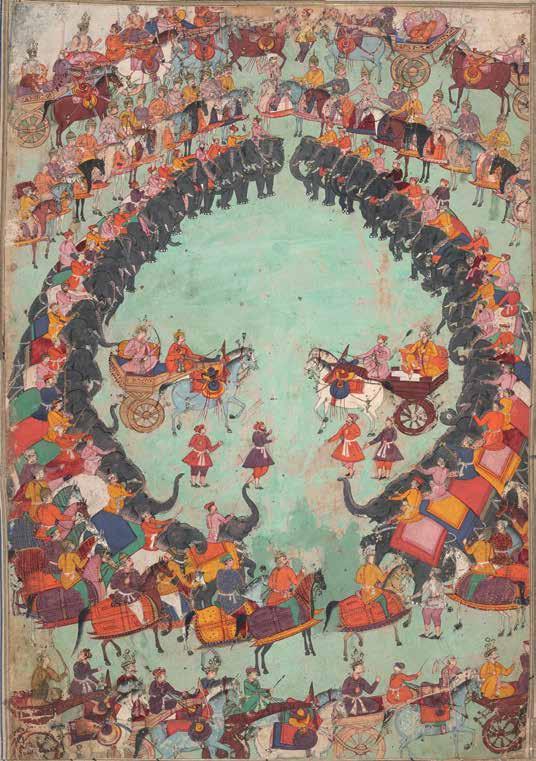

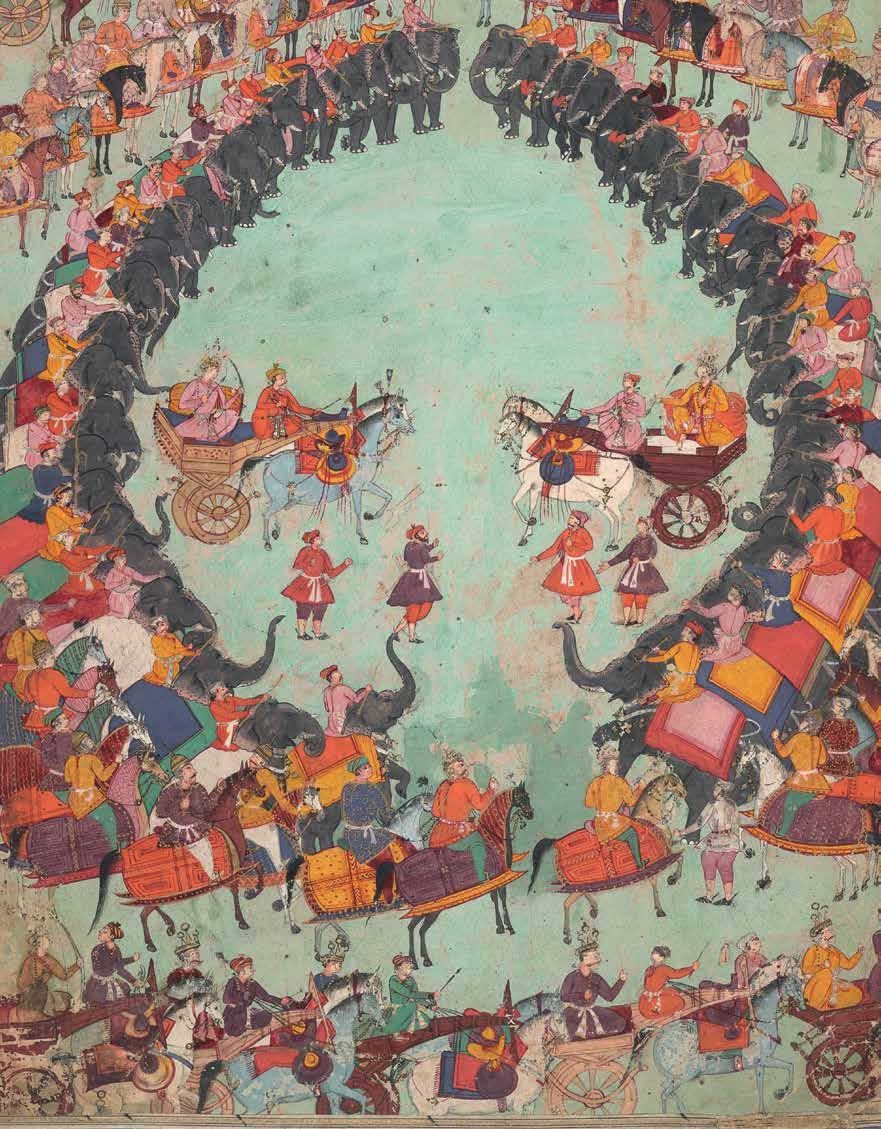

(Facing page) Battle scene from Razmnāma or the Persian translation of Mahābhārata commissioned by ‘Abdur Rahim. Gouache on paper; 34 x 22.6 cm (inside margins); c.1616–17. British Museum, Museum number: 1981.7-3.01. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

been achieved in Akbar’s court became a roadmap for India’s future, and in this, Rahim became a national

icon. For instance, a large mural adorns the walls of India’s Parliament illustrating a scene from Akbar’s court, where Todar Mal, Tansen, Abu’l Fazl, Faizi and Rahim loom large with Akbar in the foreground. 28

The story of the 19th–20th century engagement with Rahim would, however, be incomplete if it is limited

to the endeavours of litterateurs participating in the movement for the elevation of Devanagari Hindi as the

national language of India. There is a divergent and often opposing trajectory in Urdu. Figures of eminence in Urdu literary and historical writings, such as Muhammad Hussain Azad, Shibli Nomani and Syed Sabahuddin

‘Abdur Rahman of the Dar-ul-Musanafeen in Azamgarh, too, engaged with Rahim from the late 19th century onwards, either by enigmatically passing over Rahim’s Hindi poetry or by contesting the provenance of his devotional verse. For reasons of space, it is not possible to trace out here this parallel but largely opposite

process. 29 However, in both these trajectories, we see the influence of forces far removed from Mughal

history and derived from 19th and 20th centuries’ inter-communal relations and literary contestations.

Neither set of protagonists in this divide appears willing to explore the possibility that poetic form or literary

convention in themselves need not amount to either devotion or apostasy. Revisiting this contest, the reality

remains that the lack of convergence between these epistemic communities has resulted in the rich contours

of Rahim’s life suffering from neglect, as the totalizing requirements of each has created an afterlife that has overshadowed his life story and biography.

1. 2. 3.

4. 5.

6. 7.

8. 9. These are eight verses of love (madan) based poetry. Literally “beauties of a city”, this composition describes the characteristics of different city-women. A couplet that has the inverted format of a dohā (the mātrā construction being 11, 13 for each pāda of a line, which is the reverse in the dohā). The Shringār Sorthā is based on shringār or love themes. For a detailed treatment, see Rupert Snell, A Braj Bhāṣā Reader (London: SOAS, 1991), 20–21. The Nāyikā Bhed refers to a rhetorical description of different kinds of heroines. See Rupert Snell, A Braj Bhāṣā Reader, 41. Barvai is a more compact couplet than the dohā containing 12, 7 mātrās in each line. However, this tiny and rhyming couplet is composed to deliver complex messages. ibid., 21, 41. Dohās are couplets with 13, 11 mātrās in each line. Snell, 21. The standard biography of ‘Abdur Rahim’s life, political and literary career is C.R.Naik, ‘Abdur Rahīm Khān-i-Khānān and his Literary Circle (Ahmedabad: Gujarat University, 1966). For a more recent treatment of Rahim as a collector and patron of books and paintings, see John Seyller, Workshop and Patron in Mughal India: The Freer Ramayana and Other Illustrated Manuscripts of ‘Abd al-Rahim (Washington: Artibus Asiae, 1999). For Rahim’s poetical works in Hindi, see, Balkrishan Ankichan, Bhartiya Nīti Kāvya Paramparā aur Rahīm (Delhi: Alankar Prakashan, 1974); Samar Bahadur Singh, Abdur Rahīm Khānkhānān (Jhansi: Sahitya Sadan, 2018, V.S.[A.D. 1961]) For the Nāyak-Nāyikā Bhed tradition, see Rakesh Gupta, Studies in Nayak Nayika Bhed (Aligarh, 1967), 397–98, 257 etc. For barvai, see Rupert Snell, “Barvai metre in Tulsīdās and Rahīm,” in Studies in South Asian Devotional Literature: Research papers 1988-91, ed. Entwistle Alan and Francoise Mallison (New Delhi: Manohar, 1994), 373–405. Mulla ‘Abdul Baqi Nihavandi, Ma’āsir-i-Rahīmī, Vols. I–III (Bibliotheca India Series; Vol. I, 1924; Vol. II, 1925; and Vol. III, 1927). Farid Bhakkari, The Dhakhirat-ul-Khawanin of Shaikh Farid Bhakkari, trans. Ziyauddin A. Desai (New Delhi: Idara-i-Adabiyat, 2003); Shah Nawaz Khan, Ma’āthir-ul-Umarā, trans. H. Beveridge (New Delhi: Low Price Publications, 1999 [reprint]).

10 augmented reality

• audios on • a f r e e a p p a v a i l a b l e f o r i O S a n d A n d r o i d d e v i c e s Powered by ignitesol.com

ART

Celebrating Rahim Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan Edited by Shakeel Hossain Co-editor & Research Manager Deeti Ray

258 pages, 93 illustrations and a music CD 8.66 x 11” (220 x 280 mm), hc ISBN: 978-93-85360-27-5 ₹2950 | $60 | £40 Septemeber 2017 • World rights

InterGlobe Foundation sees equality in all and aspires to touch lives by dedicating itself to building partnerships and supporting sustainable programmes that bring together resources, expertise and vision in critical areas such as environmental change, job creation and the preservation of Delhi’s heritage.

InterGlobe Foundation, with a vision to promote India’s heritage and culture, sees a great opportunity in undertaking efforts in promoting India’s tangible and intangible heritage and culture. At InterGlobe Foundation there is a belief that heritage conservation not only seeds a sense of identity in communities inhabiting historic districts but also fulfills our responsibility of passing on India’s rich heritage into the hands of generations to come. With these objectives in mind, InterGlobe Foundation joined hands with Aga Khan Trust for Culture for conservation of Rahim’s tomb and revival of his literary works through publications, exhibitions and films. The conservation initiative at Rahim’s tomb is an endeavour to revive the art and artistry of a person of such magnified stature and to ensure a new lease of life for the grand mausoleum that inspired the Taj Mahal.

Aga Khan Trust for Culture is the cultural agency of the Aga Khan Development Network. Founded and guided by His Highness the Aga Khan, AKDN focuses on health, education, culture, rural development, institution-building and the promotion of economic development. It is dedicated to improving the living conditions and opportunities for the poor, without regard to their faith, origin or gender. AKDN works in over thirty countries around the world, employing 80,000 people.

Across urban conservation projects worldwide, AKTC aims to leverage the unique transformational power of culture to bring development and improve the quality of life for communities that often have a rich cultural heritage yet live in poverty.

Since 2007, AKTC has been implementing the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative as a non-profit public–private partnership between Archaeological Survey of India, South Delhi Municipal Corporation, Central Public Works Department and a host of private agencies such as the InterGlobe Foundation. The effort has three broad components: heritage conservation, improving the quality of life and environment development of historic urban landscapes.