A Rhythm Surfaces in the Mind

Edited by

Natasha Ginwala and Jesal Thacker

Edited by

Natasha Ginwala and Jesal Thacker

Ganesh Haloi

A Rhythm Surfaces in the Mind

Ganesh Haloi, born in Jamalpur, Mymensingh (now in Bangladesh), moved to Calcutta after the Partition in 1950. Witness to India’s resilient culture, its freedom and struggle for its secular modernism, Haloi is among the artists of the generation who have played a significant role in the shaping of Indian modern art.

Ganesh Haloi has cultivated a singular vocabulary of abstraction and landscape. This painterly world is textured with knowledge references that the artist is attuned to over decades—from realms as diverse as archaeology, ancient architecture, art history, sacred philosophy and poetry. His works are exercises in bringing life to the genre of landscape painting through the assembly of disparate symbolic forms. Throughout Haloi’s oeuvre, as in his thinking, there is never a separation between the nature within and the nature without.

With extensive essays by eminent art critics and interspersed with previously unpublished illustrated folios and sketches of work from throughout his life, this monograph documents Haloi’s earth-toned abstract vocabulary that has drawn over time on a vast breadth of iconography, ideas, and movements. In his paintings, Haloi is an itinerant traveller and so is the viewer—within strangely unbound time, one takes passage across the vastness of landscape, a floating geometry, the seduction of lines.

With 245 illustrations and 15 photographs

Ganesh Haloi

Ganesh Haloi A Rhythm Surfaces in the Mind

Edited by Natasha Ginwala and Jesal Thacker

Akar Prakar in association with Mapin Publishing

Edited by Natasha Ginwala and Jesal Thacker

Akar Prakar in association with Mapin Publishing

First published in India in 2022 by Akar Prakar in association with Mapin Publishing

International Distribution

North America

ACC Art Books

T: +1 800 252 5231 • F: +1 212 989 3205

E: ussales@accartbooks.com • www.accartbooks.com/us/ United Kingdom, Europe and Asia

John Rule Art Book Distribution

40 Voltaire Road, London SW4 6DH

T: +44 020 7498 0115

E: johnrule@johnrule.co.uk • www.johnrule.co.uk

Rest of the World

Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd 706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

T: +91 79 40 228 228 • F: +91 79 40 228 201

E: mapin@mapinpub.com • www.mapinpub.com

Text © Akar Prakar

Images © Akar Prakar unless otherwise mentioned.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral rights of Iftikhar Dadi, Adam Szymczyk, Lawrence Rinder, Natasha Ginwala, Soumik Nandy Majumdar, Roobina Karode and Jesal Thacker as authors of this work are asserted.

ISBN: 978-93-85360-85-5

Copyediting: Ateendriya Gupta / Mapin Editorial

Editorial Management: Neha Manke / Mapin Editorial Design: Paulomi Shah / Mapin Design Studio

Photography Debanjan Das, Chandan Bhoumik Production: Mapin Design Studio

Printed at Archana Press, New Delhi

Captions

Front cover: Untitled (detail) 2016 (See p. 185)

Page 1: Untitled (detail) 1996 (See p 191)

Pages 2–3: Untitled (detail) 2007: (See p. 116)

Pages 4–5: Untitled (detail) 2008 (See pp. 158–159)

Pages 6–7: Untitled (detail) 1995 (See p. 27)

Back cover: Untitled (detail) 1991 (See p. 110)

Akar Prakar

P 238, Hindustan Park Kolkata 700029 T: +91 33 2464 2617 E: info@akarprakar.com www.akarprakar.com

Akar Prakar D 43, Defence Colony New Delhi 110024 T: +91 11 4131 534 E: info@akarprakar.com www.akarprakar.com

A Rhythm Surfaces in the Mind 8 Natasha Ginwala and Jesal Thacker

Infinite Abstraction 14 Iftikhar Dadi Ajanta studies 36

The Song, Not the Words 46 Adam Szymczyk Benaras sketchbook, c. 1990 71

Form and Play in the Art of Ganesh Haloi 80 Lawrence Rinder

Frogs and a Snake, 1995 (Children’s book) 98

Terrasonic Agency: Working the Earth 102 Natasha Ginwala

Cholte Cholte, 2001 (Children’s book) 124

A Rhythm Surfaces in the Mind

Natasha Ginwala and Jesal ThackerEditingthis monograph over months of pandemic-driven lockdowns, mounting social alienation and loss, we found solace returning to Ganesh Haloi’s gouaches, watercolours, sketches, and written deliberations. His “desire lines” map a meditative field of reflection while signalling to human landscaping amidst rhythms and textures of the natural world. At a time when proximity between human bodies and the atmosphere is treated as a source of risk, Haloi’s practice may be perceived in all of its vibrancy and promise, charting terrains through which the body-mind wanders and becomes sensorially immersed.

This artist plots zameen (land) as swelling and border defying, in the mustard tones of harvest and at least ninety-nine shades of green, clocking early spring to late monsoon. Chronicling for the first time a decades-long artistic and pedagogic practice, through extensive essays, illustrated folios, and biographical anecdotes recently translated from the original Bengali into English, this book situates Haloi’s lifework as a personal journey across divided Bengal and simultaneously as offerings that are deeply attentive to the unfolding present or, as he says, arising from the movements, lessons, and sounds that transform us into “what we are today”.

Rather than chronicling Haloi’s migratory passage from a childhood spent in rural eastern Bengal to Calcutta in 1950 as a straight path, the contributing writers trace the rock faces, backwaters and tides, condensation, marshes and harbours, shifting soil and muddy fields evidenced in his compositions. After all, Haloi himself traces how seasonal changes of the coursing Brahmaputra adjacent to his village home phenomenally carved his ability to interpret the torrid moods and free will of water. In his essay “The Song, Not the Words”, Adam Szymczyk notes: “I could not help but think about the way he painted, the difference between abstraction and concrete detail being only a matter of an always-shifting distance, angle, moment, and their superimposition. The map and the place became one through his words.” (p. 52)

We are trained to see landscapes as contiguous and the horizon as an undivided gentle curve. The artist writes of bhangan and pays tribute to the fragment—

processes of shattering, disintegration and renewal across his oeuvre. In this, there is an eco-political gesture as he surveys the units that constitute an environmental whole; within is the agitation of colonial and nationalistic partitions of geographic regions, mass displacement, ecological calamities, and famines: “At the beginning, there was breaking in Nature, just as breaking will be there at the end. It is a process of continuous creation. Time and Limit are intimately associated with this process of breaking and of recreation. Breaking apart and regenerating are constantly at work as decay and growth.” (p. 235)

Roobina Karode suggests, “[E]ach painting for Ganesh Haloi is both a discovery and a struggle.” In her essay, “Re-citing Land”, she reasons around his turn away from the “figural-narrative paradigm” and his committed walk towards a “non-representational mode”. Karode reminds the reader: “He chose instead to meander the paths of abstraction, where from his visual field, human figures were the first to recede, and then gradually diminished recognizable objects from the everyday world around him.” (p. 174)

Rarely does an artist so convincingly defy art historical categorization. In engaging Haloi’s colour fields, emblematic of miniature and gigantic realities, Iftikhar Dadi carries out a deft analysis around South Asian and global abstraction: “A postcolonial approach thus situates abstraction as an ensemble of multiple genealogies and flourishings, whose beginnings and trajectories are unequivocally global in scope.” (p. 23) Importantly, as part of this “ensemble”, he proposes affiliations across the partitioned subcontinent, shared refrains, and ways of “moving alongside” casting matrices of relationality between seminal artists and pedagogues such as Mohammad Kibria, Zahoor ul Akhlaq, Nasreen Mohamedi and Lala Rukh.

Haloi summons quietude masterfully only as a poet can—an observer scoring tranquillity and chaos of the earth, rather than surface-level resurgent dramas caused by humanity. He urges us to plunge into the core of structures, patterns and epic cycles. Soumik Nandy Majumdar ponders in his in-depth essay “Painter of the Twilight Zone”: “Truly, silence in his works transmutes itself into a living and palpable pictorial reality. Moreover, silence in his works keeps both the viewer and the viewed captivated in a timeless frame, intensely looking at each other, as it were. It is in this act of mutual looking that the mapping of the silence also takes place.” (p. 133)

The monograph includes a folio with Haloi’s sketches, journeying from Calcutta to Santiniketan and traversing the Birbhum landscape. Majumdar, who currently teaches at Kalabhavana, posits: “… Haloi disseminated the idea of a holistic sense of aesthetics, learnt primarily from his knowledge of Santiniketan, founded by Rabindranath Tagore, and its most influential pedagogue, Nandalal Bose. Although he could not study art in Santiniketan, he developed a lifelong attachment with the ideals of Kala Bhavana and considered the great artist-teachers of Santiniketan as his spiritual mentors. Haloi’s sensibilities and responsibilities as a teacher have an unmistakable connection with Santiniketan.” (p. 155)

Numerous artists, filmmakers and writers from India and the world have depicted the ghats of Varanasi. It is one of those mystic locales that promises magic and deliverance amidst the grime and the cunning of holy men, and in its continual representation that is one of the paradoxes, instead of a clear reflection pool for spiritual absolution. In Haloi’s small-scale drawings tucked away in a sketchbook, which he

first showed curator Juan Gaitán and me (Ginwala) during a visit in 2013—and now appearing in this book—there is a purposeful stripping away of the visual density: there is no sacred iconography besides the hint of a flag and contours of architectural form. Instead of a city teeming with devotees, he focuses on diagonal lines—meticulously traced outlines of the riverfront steps and a monkey in motion.

“The sheets of paper are small—almost the scale of miniatures—yet the works can elicit a sensation of cosmic vastness. However, one can hardly call Haloi a strict formalist: his compositions are frequently home to imagery, from trees and leaves to hills and fields as well as architectural elements such as stairs, windows, and walls,” writes Lawrence Rinder. (p. 86) He continues: “The previously mentioned Benares ghats, for example, as well as linear and simply geometric renditions of the dwellings of Rajasthan, arches and tiles of the ancient Islamic city of Pandua in West Bengal, and the frequently appearing motif of a walled enclosure.”

In her essay “Processing a Line”, Jesal Thacker notes, “Tracing the axis of life as resha (line) that governs the unknown,” exploring the essence of line as rhythm (prana), resonance (dhvani) and energy (urja). Thacker provides a sweeping view of Haloi’s drawing practice, from his early botanical drawings and his life-altering visit to Bodhgaya, to his line studies and field notes that decode the murals of the Ajanta tradition, its indigenous trajectory through ancestral stakeholders who live in proximity to the archaeological grounds, and Haloi’s reading of Ajanta’s larger premise as far back as the 1950s— concurrently as a civilizational and spiritual contact zone.

In poetics, dhvani is identified as the sound between two words, as an anurananarupa (echo-resonance), or sometimes as the silence between the two words, perceived as anhatanad (primordial sound). The monograph resonates between these elements of words and images, with folios alternating with the essays as the improvised sounds in an orchestra. Haloi wrote a painterly language that we welcome you to peruse. Sensing our own lack as we grew to know him, we have borrowed heavily from his spirit of gentleness and rigour. Between essays, his dhavni fills the page.

“The sky looked dark blue, limitless. The reflections of the floating boats quivered in the water as light breeze made ripples on the still surface of the winter river. Waves made by the tail strokes of big fish slowly receded. But the rhythmic motion of water at the edge of the river continued. It was like the feeling you have when you put down your feet from a sailing boat into the water.” (p. 216)

Infinite Abstraction Iftikhar Dadi

Ajanta studies

It was 1956, when the 2500th anniversary of the Buddha’s birth was celebrated. Our journey began in early December. The Bihar government had organised a commemorative fair where we were supposed to do some work. The person inviting us was an artist himself. The fairground was close to the Buddha temple. Our temporary billets were tents nearby.

The winter chill of Gaya was factored in. A thick layer of straw served as mattress.

Every night at bedtime our artist host opened a fund of anecdotes. One night he told us about Nandalal Bose’s discovery of an Ajanta mural under the glowing light of a petromax lantern. It showed a lady making chili paste with a mortar and pestle and the lady sitting next to her rubbing her eyes which must have been burning from chili dust. The story sowed in my mind a strong wish to see Ajanta. I decided to go to Ajanta any which way I could. If necessary I would work as a tea shop boy and see Ajanta.

—Ganesh HaloiAjanta

Mixed media 48.9 x 42.5 cm (19.25 x 16.75 in.), c. 1950s

Courtesy: Artist Collection: Private

The

Song, Not

the

Words Notes on the Works and Writings of Ganesh Haloi Adam Szymczyk

Form and Play in the Art of Ganesh Haloi

Lawrence Rinder

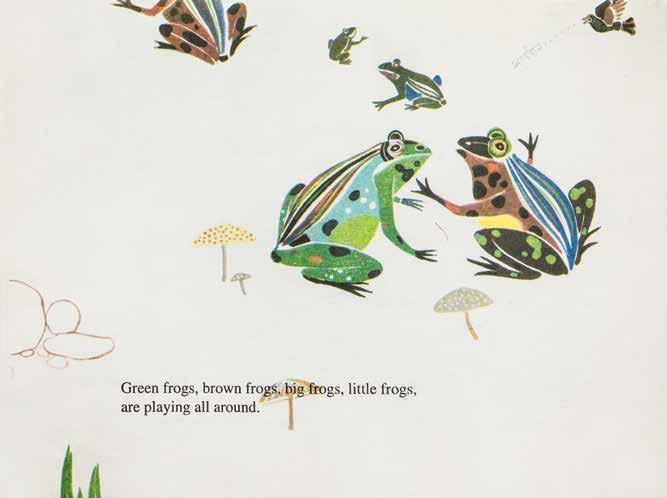

Frogs

and a

Snake, 1995 (Children’s book)

Terrasonic Agency: Working the Earth Natasha

Ginwala

Cholte Cholte, 2001

(Children’s book)

Chalte chalte, we see many things, everyone sees, why don’t you also see—the trees, sky, river, birds and animals. All are but images/ paintings. There are all kinds of images all around; it’s a matter of seeing.

First Edition 2001, Papu Memorial Trust

Cover page: Cholte Cholte by Ganesh Haloi

First Edition 2001, Papu Memorial Trust

Cover page: Cholte Cholte by Ganesh Haloi

Pintoo and Parul, brother and sister, study at local school in their village. On the way to the school, they see many things. One day, on the return journey, Parul says, “See brother how tall that tree is, like a huge straight line.” Pintoo replies, “Correct, trees also stand straight like humans, but they can’t walk.” Parul says, “Oh! it’s like that boy doing exercises. The tree is also like the boy standing, isn’t it?” Pintoo responds, “True. You are very intelligent, Parul”.

Now it’s Pintoo’s turn. “See, Parul, how that tree is lying on the ground, like a minus sign in a mathematics book. That boy exercising is also as if he is teaching subtraction.” Parul nods and says, “Yes.”

Far left

A bird squealing nearby says, “That tree was my home.” Upon hearing this, both Parul and Pintoo feel sad. “Should anyone cut a tree in this manner?”

Left “Brother, brother,” says Parul. “See how the branch from the tree has beautifully extended out diagonally from the tree.”

Painter of the Twilight Zone Soumik Nandy Majumdar

Re-citing Land

Roobina Karode

Form and Play sketchbook, 2018

Breaking as Creating: ‘Bhangan’

“In painting, the nature of breaking or distortion depends solely on the state of mind of the creator.”

When I walk, I break the path. I can move ahead because I break the path. The kind of breaking I do depends upon the rhythm of my walk. At the beginning, there was breaking in Nature, just as breaking will be there at the end. It is a process of continuous creation. Time and Limit are intimately associated with this process of breaking and of recreation. Breaking apart and regenerating are constantly at work as decay and growth. The glass tumbler slips from my hand and breaks; the flowing river breaks its banks. There is no visual similarity between these two kinds of breaking, yet all breakings have the tendency of keeping the essential nature of the material intact. The character of my childhood growth is quite different from the decay of my youth and old age. I break, but retain my essential “I”. Sometimes, the character of a breaking is loud, but many a breakings happen quietly. When the river bank breaks or the glass tumbler breaks, we can visualize the breakings through the sound they make. But whatever breaks in silence is not easily seen. When a person breaks from within and cries out, the crumpling can be seen and heard, but when the soul is shattered, nobody sees or hears anything. A loud heartbreaking cry is clearly heard, but a silent breakdown is deeper: it is a split in the inner self.

Breakdowns and breakings are a universal phenomenon. Breakings release a storehouse of energy. Whatever is visible, we do not always see. When we see something visible, the visible breaks itself down in concurrence with the state of our mind; it takes on a different look.

A powerful folk-poet describing the scorched, rainless landscape cries out: “Everywhere, even the sky broke into pieces Just as the parched, fractured land”

Natasha Ginwala, Associate Curator at Large at Martin-Gropius-Bau, is a curator, researcher and writer based in Colombo and Berlin.

Jesal Thacker is an artist by training and founder of Bodhana Arts and Research Foundation.

Iftikhar Dadi is John H. Burris Professor and Chair of the Department of History of Art at Cornell University.

Adam Szymczyk, presently Curator-at-Large at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, is a curator and author based in Zurich, Switzerland.

Lawrence Rinder is a curator and Director Emeritus of the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

Soumik Nandy Majumdar is presently a faculty member of the Department of History of Art at Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan.

Roobina Karode has been the Director and Chief Curator at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi since it opened in 2010. other Titles of interest Ganesh Haloi: Sense and