mutable

ceramic and clay art in india since 1947

This volume is the first major publication on the vast varieties of ceramic histories and practices in India. The result of the 2017 exhibition ‘Mutable’ at the Piramal Museum of Art, this book archives the work of hereditary potters, industrial ceramics, studio pottery and artists who use clay as a medium.

Situated within the larger context of the postIndependence craft revival, this volume pays keen attention to the transnational histories of practice through five sections. The section Shift explores the local and international lineages of Indian studio pottery. Object discusses the ways in which clay has been a unique medium of expression for many artists. Utility considers the development of Indian ceramic industries, through lenses of economics and class. Form takes as its subject hereditary potters who negotiate modern-day artistic spaces. Perception focuses on the low-fired water container and its web of connections with its makers and users. The very mutability of clay and its shaper and the resulting dynamism, that produces both tensions and opportunities, are at the centre of this book.

With 175 photographs.

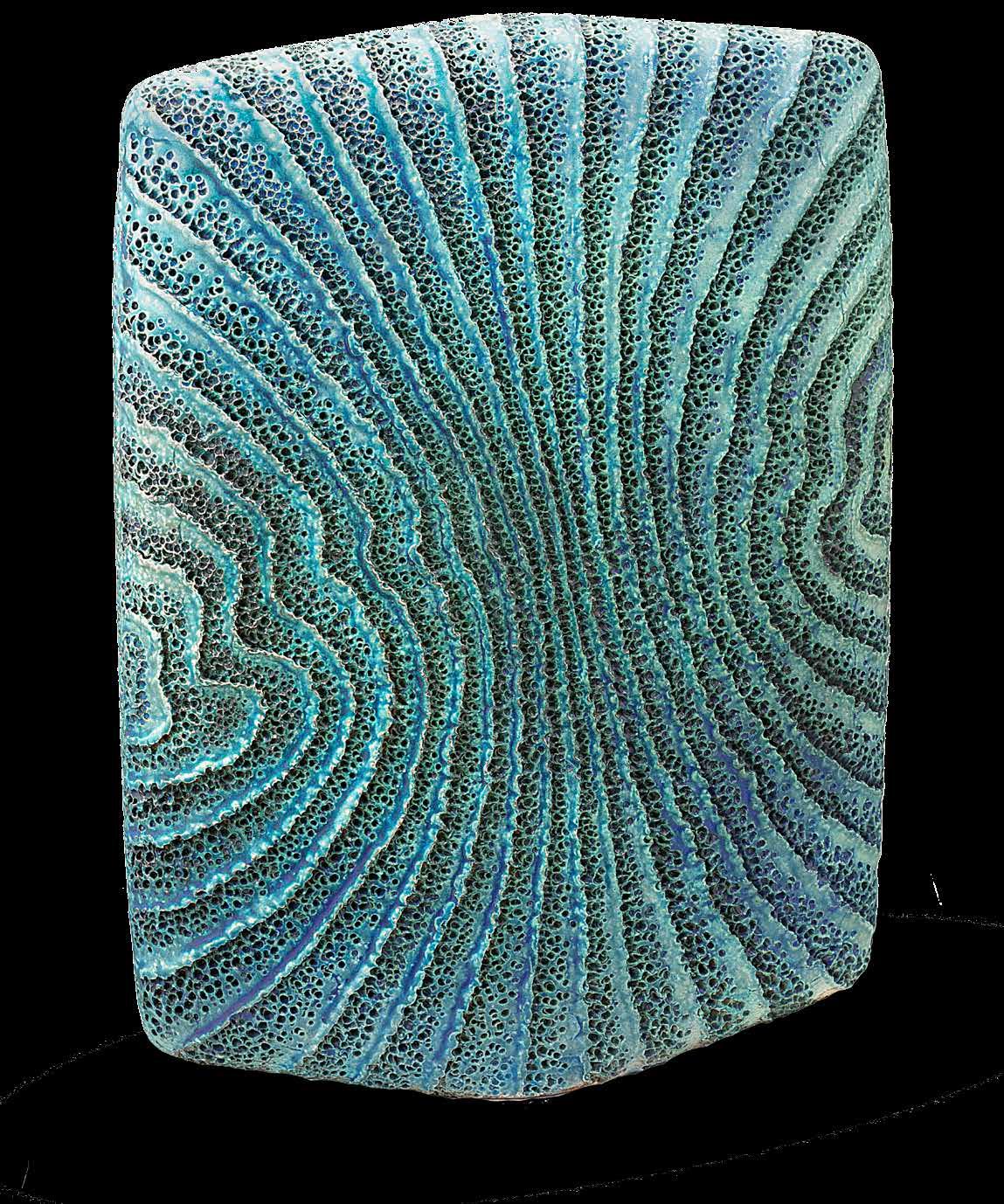

front cover Ira Chaudhuri, sgraffito on stoneware (See p.65) back cover Abhay Pandit, Tension of Lines (Seascape), stoneware (See p.88)ceramic and clay art in india since 1947

Sindhura D. M.

Sindhura D. M.

Introduction by Annapurna Garimella with an essay by Kristine Michael

First published in India in 2020 by Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

In association with Piramal Museum of Art

based on the exhibition ‘Mutable: Ceramics & Clay Art in India Since 1947’ curated by Sindhura D. M. and Annapurna Garimella, Jackfruit Research & Design, held in Mumbai from October 13, 2017 to January 15, 2018.

International Distribution

North America

ACC Art Books

T: +1 800 252 5231 • F: +1 212 989 3205

E: ussales@accartbooks.com • www.accartbooks.com/us/

United Kingdom, Europe and Asia

John Rule Art Book Distribution

40 Voltaire Road, London SW4 6DH

T: +44 020 7498 0115

E: johnrule@johnrule.co.uk • www.johnrule.co.uk

Rest of the World Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge

Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

T: +91 79 40 228 228 • F: +91 79 40 228 201

E: mapin@mapinpub.com • www.mapinpub.com

Text © Authors

Images © the respective owners and organizations as noted in the captions.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral rights of Sindhura D. M., Annapurna Garimella and Kristine Michael as the authors of this work are asserted.

ISBN: 978-93-85360-56-5

Photography: Arjun Dogra

Copyediting: Shernaz Tyabjee and Marilyn Gore / Mapin Editorial

Editorial Supervision: Neha Manke / Mapin Editorial

Design: Gopal Limbad / Mapin Design Studio

Production: Mapin Design Studio

Printed in China

page 2

Bhuvnesh Prasad, Untitled, 2017, terracotta (See p. 114)

page 5

Ange Peter, Dragon Teapot, “Emergence”, 2013, porcelain on stoneware (See p. 85)

page 6

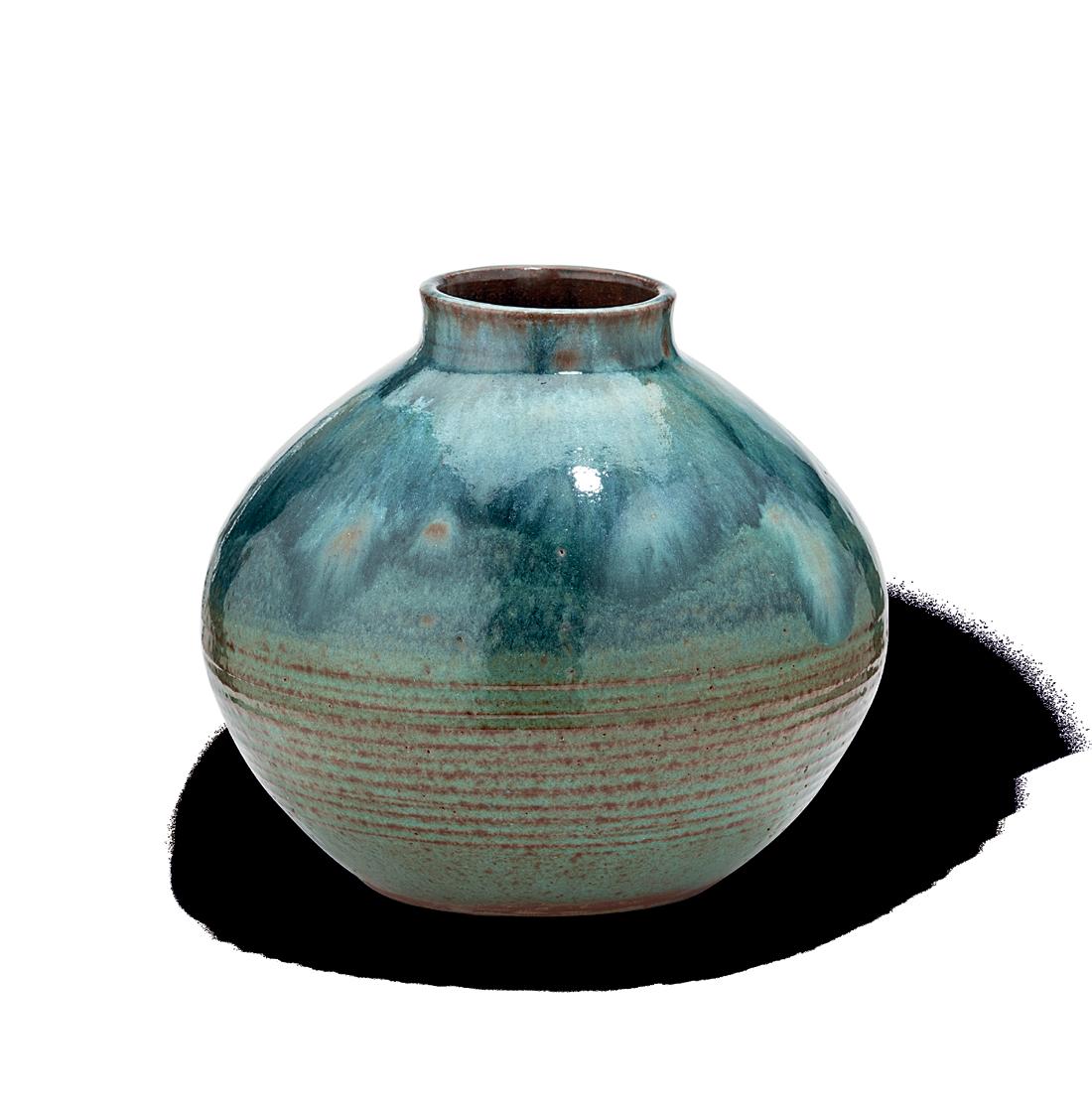

Mansimran Singh, 1990s, earthenware (See p. 39)

This book focuses on clay and ceramic art made in India since 1947. It is the outcome of the year-long research we did for the exhibition titled Mutable: Ceramic and Clay Art in India Since 1947, sponsored by and held at the Piramal Museum of Art in Mumbai from October 2017 to January 2018 As the planning and work for this publication progressed, we immediately recognized that the exhibition was an extraordinary archive of the field, its numerous and diverse practitioners and the associated histories of their practices—something which did not previously exist. By consolidating and framing this archive with an interpretive structure, we have placed the medium and the practices within the discourse of art history with connections to colonial, post-Independence and contemporary histories of materials, manufacturing and taste.

The exhibition and this publication map 70 years of ceramic and clay art made during the creation of a modern and decolonizing India. Structured in five sections—Shift, Form, Utility, Object, Form and Perception— they address the myriad practices and showcase the work of potters (studio and hereditary), ceramicists and artists. Since 1947, the various programmes to revive India’s crafts on the one hand, and rapid

industrialization and new technologies on the other, have impacted three generations of village and hereditary potters, studio practitioners, artists and organizations. The book also discusses, following the exhibition, works made outside of any specific ideological or institutional framework. Of special interest are objects produced by collaborations between potters and artists, artists and industry, studio practitioners and hereditary potters, and between organizations and potters. This book discusses all these practices while marking and documenting the historical transformations and conceptual shifts which have impacted various ways of making ceramics in India.

Clay as a medium for utilitarian and decorative ware or the art object has taken a new turn since the arts and crafts movement, which flourished in various countries between 1880 and the 1920s. Since then, ceramics as a mode of expression has been seen primarily as a craft and critical engagement with it has come from this understanding. From art historian and critic Garth Clark’s point of view:

The entire paradigm of what ceramics is in our culture is today shifting at unprecedented speed. Ceramics in art is almost unrecognizable from two years ago. Overall contemporary ceramics is going through a change of guard, more radically than anything the field has experienced in 150 years.

It has moved from marginalization to mainstream. It is not a move in progress that might happen as so many articles argue. It is done. Over. Complete. The art vs craft debate is officially dead. Just about every major international art dealer has embraced ceramics. And the design field has absorbed it with gusto, producing hand made as well as industrial. Ceramics populates every art fair and does well on action. True, its heightened presence during this honeymoon period may calm down in a while, but it is not going away.1

In the Indian context, too, ceramics has undergone and surely is going through radical changes, a point that is stressed throughout this book. In order for us to write this art history, we must move, like the medium itself, between transnational and global, as well as national, institutional and local narratives.

Clay has been used by many types of makers in diverse ways; it can move between the workshop and the studio; and it can shift conceptually between craft and art. Historically, ceramics have been identified with their function in serving, storing, decoration and ritual. In the modern era, these historic purposes were further consolidated as industrialization and middle-class urban life became more elaborate and specialized. Various regional arts and crafts movements responded to these transformations and, in the case of ceramics, the response from Japan—in the context of the Mingei movement—was particularly strong, articulate and influential for India. One of Mingei’s most important ideologues, Yanagi Soetsu wrote that craft is “things made to be used by people in daily life, such as clothes and furniture. Something different from fine arts, such as pictures [that are] made to [be looked] at.”2 As we show in the Shift chapter, these ideas came directly

to India when people such as Sardar Gurcharan Singh travelled to Japan and brought back not only the ideology of the local and utilitarian but also Japanese ceramic techniques and technologies. Japan, and particularly Mingei, indirectly shaped studio practice more widely through other important figures such as Bernard Leach, Mansimran Singh, Deborah Smith and Nirmala Patwardhan.

In the 1950s, especially in the US, the idea of clay as a material for functional ware was manipulated by many artists, including Peter Voulkos, to make hand-built sculpture specifically to be exhibited in white cube gallery spaces. The romantic idea of studio pottery previously associated with craft slowly started to fade. As these experiments gained wider currency, clay’s materiality and capacity to be manoeuvred into desired shapes, textures and designs led to several conceptual and critical works from the 1960s and the 1970s in the US and Europe.

By the 1950s, the idea of the studio potter working individually and producing functional ware had started to change, and many art-college programmes began to incorporate ceramics into their pedagogy. For example, in 1954, Voulkos was invited to set up the ceramics department at the Los Angeles County Art Institute, which was later renamed the Otis Art Institute.3 Since it was a new department, Voulkos had no programme to follow, with little equipment and few students. Because there was no separate studio for him, he made works in the classroom, blurring the formal relationship between the teacher and the student.4 Potters who turned into sculptors began to see the production of functional ware, especially wheel-thrown vessels crafted as “conceptual limit activity.”5 For these modern ceramicist-artists, craft became a useful tool to understand and manoeuvre ceramic materials to further their artistic visions. While rejecting conventional functional forms, they adopted traditional tools and techniques and adapted them to new ideas and forms. This is why ceramic practice, both in India and elsewhere, moves between art and craft to this day.

These transformations have been mapped by several writer-practitioners such as Edmund de Waal and Emmanuel Cooper, and their books have become seminal volumes on how the practice and field of modern ceramics operates internationally. Unlike disciplines such as painting and sculpture, ceramicists themselves have been the most important writers and theoreticians of their practice—right from Shoji Hamada and Soetsu in Japan, and Leach, de Waal and Cooper in England, to Gurcharan Singh, Patwardhan and Ray Meeker in India. Perhaps because ceramics are loosely associated with decorative arts and crafts and because the medium needs to be understood and analysed as a material and not just as an outcome, practitioners have been the most helpful in creating a discourse for the discipline. It is only recently that art historians and curators have begun to create a conceptual framework for this immense and fascinating legacy by reading the writings of these ceramicists while also connecting their ideas and production to larger artistic movements, institutions and wider transformations in the field of culture and politics.

One 20th-century institution that is crucial to any history of ceramics is the Bauhaus—founded in 1919 at Weimar, Germany—where radical experiments in pedagogy and practice sought to demolish the boundaries between the artist and the artisan.6 The ideas formulated at this short-lived institution came to India in 1922, when an exhibition at the Indian Society of Oriental Art showcased Bauhaus art and the work of Indian artists who were conducting their own radical experiments in arts pedagogy at Calcutta and Santiniketan, as a “process of shared visions rather than transmission.”7 The main basis of the Bauhaus was to include handicrafts in their teaching. These were taught by artists and master craftsmen. A similar approach was adopted later by the American designers Charles and Ray Eames while writing a report (“The India Report of 1958”) to build a design institute in India. Institutions such as the National Institute of Design (NID) were founded on the understanding that the way to build the future was to acknowledge and recognize the past. Educational institutions such as these became the base

for a new kind of making, which inevitably impacted clay and ceramic art.

Arts and crafts movements and art and design institutions produced different kinds of makers, including ceramic artists, designers and studio potters. After World War II and after India’s Independence, the educational institution and the site of work became more important for the kinds of objects that practitioners made. For example, clay vessels made by a studio potter were similar to the Mingei style and were made in a setting that was similar to Hamada’s own studio in Mashiko, Japan. Even today, Indian studio pottery is usually managed by an individual who has a few employees and apprentices. Until recently, their market has been small, and functional-ware objects are usually sold directly through their own studios or at craft fairs and shops.

The situation in a modern artist’s studio is quite different. Here, all kinds of art objects are made. In the case of ceramics, it is sculpture. Craft as a skill is fundamental to ensure that work is well executed; however, it is not important for artists to make these works by themselves. Instead, they take technical help from seasoned clay practitioners while retaining control of the making processes.8 Ultimately, as Glenn Adamson has discussed eloquently, craft becomes submerged so that art can shine.9 This is starting to change as ceramicists are beginning to assert their agency in making concepts and artists too have begun to approach craft as a concept.

Clay in India has been used for various purposes and, like in many other places, it has a long history here. Even today, red clay is used in rituals, to make cooking ware, and to make bricks. Metaphorically, it is considered to be Mother Earth in certain contexts. The ritual and functional ware made by hereditary potters have been widely discussed by various writers such as Pupul Jayakar, Stephen Huyler and Jane Perryman. In fact, this is probably the most widely visible aspect of Indian clay art.10 There is also a vibrant history of Islamic ceramic art in India, which began nearly a thousand

years ago as much-coveted Central Asian and Chinese glazed figurative ceramic objects were first imported and then made in the subcontinent. These developed into the distinctive regional ceramics of Delhi, Khurja, Jaipur, Bidar, Lahore, etc. The Albert Hall Museum, established by the maharaja of Jaipur and opened in 1887, holds an extraordinary collection of the subcontinent’s historical ceramics made by Scottish physician Alexander Hunter. It was recently re-curated by art historian and ceramicist Kristine Michael, who has contributed an essay to this book.11 All of these objects stand in collections that emphasize lineages of pre-colonial and colonial ceramics. The Mutable exhibition and this book’s contribution to this landscape form the making of a large archive of post-Independence practices and objects in which we offer interpretive frameworks as well as documentation.

After 1947, India began the task of building a new nation with its own identity and with a sense of the future. Both Nehruvian and Gandhian philosophies of development—one machine-oriented and focused on the large-scale, while the other human-oriented and local— were adopted; the Utility and Form chapters discuss these two world views and their impact on ceramics practice. The concept of swadeshi (“made in one’s own country”) echoed through the work of several artists and craftsmen as they looked at existing Indian art and crafts in order to create something new.

Nehruvian and Gandhian ideas also led to the foundation of new institutions and organizations such as the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) and the National Institute of Design (NID). More than half a century later, Indian craft as the mother of Indian industry and design (as taught at NID) and craft as a form of development (as viewed by KVIC) remain foundational yet shifting concepts for these and many other institutions. These concepts are just beginning to be analysed by historians of modern India—a process to which this book seeks to contribute.

decades after Independence, including the work of India’s large demographic of hereditary potters. New museums—such as New Delhi’s National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum (also called Crafts Museum) that was initiated by Chattopadhyay in 1956—and, later, growing regional collections—such as the one at Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal—housed various handicrafts, including everyday and ritual pottery. In the 1980s, the Festival of India exhibitions showcased the country to the world and gained huge recognition for its craftspeople among others.

Anthropologist, art historian and curator Jyotindra Jain is another seminal figure in the history of postIndependence cultural institutions. He has worked with various practitioners and built collections for New Delhi’s Crafts Museum and Sanskriti Foundation, and has helped make these spaces available for important creative and market transactions in ceramics. He, along with other curators, suggested new themes to craftspeople in order to stimulate their potential and attract a new market for their work, and also alerted collectors to turn towards India’s diverse vernacular art forms. This started with Jain’s exhibition, Other Masters: Five Contemporary Folk and Tribal Artists of India. All these events cumulatively opened the doors for a much-needed rethinking, and provided opportunities for national and international exposure, intellectual stimulation, networking and sales, all of which encouraged many hereditary potters to relocate to or establish a base in New Delhi. This move to an urban space, an issue this book addresses consistently as an important historical experience, had tremendous impact on their work.

Several craft revivalists such as Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay began to document crafts in the initial

Along with these national transformations, the 20thcentury Pan-Asian movement and European and American interests in Eastern philosophies are also implicated in the growth of a new kind of ceramic practice in India.12 The concept of studio practice slowly began to enter the country with the arrival of functional glazed stoneware. This type of ceramic allowed for handmade products to be modern and futuristic with a long shelf life and became a way of countering the thrust toward industrialization, something which is

discussed in the Shift chapter. Gurcharan Singh’s 1954 exhibition in Mumbai was perhaps the first to showcase glazed stoneware pottery in independent India. Galleries such as Art Heritage in New Delhi, and Cymroza Art Gallery and Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai began to showcase ceramic works by Singh, B. R. Pandit, P. R. Daroz and many other potters, represented in the Mutable exhibition and in this book. The Ceramic Circle Group exhibition in 1981 at the Jehangir Art Gallery was successful in placing ceramicists on the same platform as other practitioners of the fine arts.13

Although exhibitions were in progress, documentation, archiving and art historical scholarship of ceramics began much later, in 1996–97, when Kristine Michael received a fellowship from the Eicher Gallery, New Delhi, to research the work of 12 studio potters in India.14 Michael’s interest in research and art history has led to two decades of writing, publishing and curation. She curated the ceramic gallery at the Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur, and has done extensive research on Jaipur Blue Pottery (JBP); recently, she curated an exhibition for the first Indian Ceramics Triennale (2018) on Kripal Singh Shekhawat, the artist who, along with Chattopadhyay, revived JBP. Michael has also brought an art-historical perspective to what is generally designated as “craft” and placed ceramics within the frame of contemporary

craft practice. She often writes about her ceramicist peers, creating a dialogue between practitioners, collectors and art historians.

Apart from the work of public institution builders and individual art historians, independent organizations such as Jackfruit Research and Design (JRD, founded 2005) have been working on various vernacular art forms. JRD’s 2010–11 exhibition, Vernacular, in the Contemporary, curated for the Devi Art Foundation, and several others of its curatorial projects have continued the work of reframing art and craft forms, some produced for the community and some for the market, into larger conceptual frameworks that allow for critical engagement and productive reimagining of the relationship between the ideas of tradition and the contemporary. Jackfruit has also worked with various contemporary and studio artists—all of whom have been or are engaged in historic and new craft forms that come from India’s myriad vernacular visual cultures and geographies. The Mutable exhibition and now this book expand upon JRD’s decade of work—in art, craft and design—by engaging with industrial objects, pedagogical institutions and the complex histories of a medium which has been in a hierarchically lower position in relation to painting and sculpture, while also seeking to question the hierarchies within the field of clay and ceramic art.

Ceramics today are showcased in galleries and art fairs (Figure 1) and museum exhibitions, as well as at the Indian Ceramics Triennale: Breaking Ground (Figure 2), which was held for the first time in 2018 at Jaipur Many of these initiatives, while showcasing dynamic practitioners and ambitious work, have not made a commitment to fostering art-historical and critical discourse. They showcase and create linear narratives of contemporary ceramic practices and imagine their origins as lying solely within the ceramicist’s studio. Whereas museums often exhibit archaeological findings and historic decorative ceramics, the Triennale showcased only the works of contemporary ceramicists from across the world through a wide range of sculptures, installations and performances. In the effort to position ceramics as a form of contemporary studio art, the Triennale chose only makers who move between studio pottery and artmaking. With the notable exception of Kristine Michael’s exhibition on Kripal Singh Shekhawat, mentioned above, it did not focus on the diverse ceramic practices that happen in other realms as well as the modern art history of studio ceramics and revival pottery.

In general, ceramics exists in a complex scenario where a diverse range of making is practised. Even

though some makers move away from traditional boundaries, they still hold on to their root practice. For example, the hereditary potter B. R. Pandit, who makes glazed stoneware pottery in Mumbai, is now in his seventies and is positioned as an artist-potter; but he maintains his studio’s work within the family and his caste structure in a way similar to a hereditary potter, a fact which is analysed further in the Form chapter. On the other side, studio potters, artists and designers who have formal training move between making conventional and non-conventional forms in order to have a sustainable livelihood while making art. While all these practices coexist, each of these practitioners— whether they acknowledge it or not—have their roots in some tradition or are inspired by it. A designer makes stoneware containers which look like bharanis (pickle jars); a studio potter such as Puneet Brar uses red clay to make sculptural work based on hereditary pottery; and artists like K. G. Subramanyan—who used terracotta to work with a vernacular material—all have a profound involvement with the rich ceramic traditions of India.

To position complex histories of making and interpret objects and data, Mutable turned to Glenn Adamson’s book Thinking through Craft and several other publications of his students and colleagues at the Royal College of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum. This body of work

left

fig. 2 Juree Kim, Evanescent Landscape: Svarglok, Jaipur, 2018, raw clay, water, video installed at Breaking Ground Triennale 2018, Jaipur (Image © Sindhura D. M., Jackfruit Research & Design, Bengaluru)

right

fig. 3 Panoramic view of the exhibition (Image © Piramal Museum of Art, Mumbai)

has been immensely helpful in teasing out the specific complexities of the Indian ceramics field, especially in its relation to the idea of craft. Throughout this book, the word “craft” is used in two important ways: the first as it has been understood historically in modern India to represent tradition, function and skill and, secondly, borrowing from Adamson, as a conceptual tool for artists. Further, we also turned to studio potter and writer Emmanuel Cooper’s idea of various kinds of pots from his book Contemporary Ceramics. He surveys teapots and tableware as well as installations and video works from various makers who use clay as an artistic medium. The exhibition also loosely followed Cooper’s approach to exhibiting studio pottery, industrial ceramics, hereditary pottery and artists who make works using clay as separate but connected to practices and objects. Along with Adamson and Cooper, the historian and critic Howard Risatti’s A Theory of Craft was helpful in thinking through various ceramic objects and how they are made, for what purpose, and how they function, which further helped in considering what is “craft” and “art” within the field of ceramics.

Jackfruit found Cooper’s framework for contemporary ceramics immensely helpful in deconstructing the boundaries between hereditary pottery, industrial ceramics, artists’ work and studio pottery, and to reconceptualize existing practices. Mutable is a watershed curatorial project because it showcased all kinds of clay work on a single platform and sought to think through their coexistence and their differences without reinforcing or imposing existing hierarchical positions in the research, curation or exhibition design. It was possible to do this because the exhibition was held in a “disobedient” space and not a permanent structure with its well-established museological commitments and agendas. Held at the Piramal Museum of Art, Peninsula Corporate Park, Lower Parel, Mumbai, Mutable was installed in the central courtyard on the ground floor of an office building. Because the Museum is situated within a temporary space with impermanent architecture in a transition zone and because it is a

young organization, it allowed us to reimagine and build a new, open space without many walls in which three-dimensional objects could literally see and talk to each other while viewers watched, and promoted the conversation while making connections between the five sections, which also form the basis of the chapters in this book. Freed from these boundaries and walls, the various pieces arrayed themselves into a landscape of ceramics, allowing the viewer to look from all sides (Figure 3).15 A similar approach has been adopted in writing the book; each chapter can be read on its own as a standalone chapter with its own beginning and end, or it can be read in sequence to build connections. Providing the reader with the freedom to choose a point of entry supports the curatorial goal of a nonhierarchical space in which differences between objects and makers are permitted, and which are made available for contemplation and discussion. Similarly, the exhibition and this book consistently use the word “maker” while describing various potters without rejecting the terms of their preferred creative identity. “Maker” allows us to accept heterogeneity and introduce commonality across sections as well as within each category.

Even though this book refers to the works that were exhibited in the Mutable exhibition, ultimately it performs another task. The exhibition was a space for creative output for public pleasure and reflection, and it was a moment of consolidation in the larger arthistorical project that this book represents. In order to write about ceramics in India since 1947, about which there is very little published historical work, we began by archiving and contacted Kristine Michael, who provided enormous support in gathering resources and contacts to build up the documentation. With her initial guidance, the research and the writing of the book took on the task of building an archive of Indian modern ceramics through study and fieldwork. Apart from looking at Japanese, European, Australian, British and American writings on ceramics, we turned to the syllabi of various art schools to understand the role that clay plays in pedagogical institutions such as the Faculty of Fine Arts at Vadodara’s Maharaja Sayajirao University.

The archive was populated with interviews, especially conversations with ceramicists and important collectors such as Anuradha Ravindranath and Raj Kubba, primary materials on art and craft, popular press art, writings from blogs, contemporary travel accounts and other such online resources.

All these sources furthered our analysis of modern and contemporary ceramics practices. As a result, this book talks about a variety of practices that traverse hierarchies of materials, economies and art spaces. For example, hierarchy can be seen in the way the workshop, the studio and labour are organized; all this also affects the forms, techniques and conceptual orientation that produce ceramic objects. While, for many makers, the idea of being conceptual is an aspirational idea, we chose to see that the “making” itself is a profoundly conceptual experience as is writing a history of it. The way in which practitioners

of industrial, hereditary, studio and artistic ceramics understand the medium and the field is generally quite fluid and, if they have any identity, it is momentarily embodied in specific works at specific moments. The book does not emphasize either material or conceptual purity. Instead, it focuses on crossovers, confusions and the hybridity within various kinds of making as extremely productive processes.

While Shift, Form, Utility, Objects and Perception discuss the works which came out of plural ways of making, Michael’s essay on the transnational history of Indian studio pottery through the works of Gurcharan Singh, Kripal Singh Shekhawat and Ray Meeker foregrounds how new techniques, glazes and kilns came to India through their work. From the exhibition and the book, it is clear that the ceramic object in India emerges in the space between the local and the transnational.

1. Garth Clark, “Pen and Kiln: A Brief Overview of Modern Ceramics and Critical Writing,” in The Ceramics Reader, ed. Andrew Livingstone and Kevin Petrie (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 3.

2. Yanagi Soetsu was a Japanese philosopher and founder of the Mingei movement. Yanagi Soetsu, The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty (USA: Kodansha, 2013), 197.

3. Edmund de Waal, 20th Century Ceramics (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), 157.

4. Ibid.

5. Glenn Adamson, Thinking Through Craft, (Oxford: Berg, 2007), 2.

6. de Waal, 20th Century Ceramics, 68.

7. Regina Bitter and Kathrin Rhomberg, eds., The Bauhaus in Calcutta: An Encounter of the Cosmopolitan Avant-Garde (Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2013).

8. Jeffrey Jones, “Studio Ceramics: The End of the Story?” in The Ceramics Reader, 183. (DOC) interpretingceramics.com/ downloads/studioceramics.doc

9. Adamson, Thinking Through Craft, 1–7.

10. Pupul Jayakar’s book, The Earthen Drum, documents the ritual arts of India. In Gifts of Earth, Stephen Huyler surveys the various kinds of hereditary potters and their works from across India. He documents the potters’ techniques and productions in this book. Jane Perryman in her book Traditional Pottery of India studies the potter’s community, philosophies and techniques.

11. Apart from Albert Hall Museum, Bhau Daji Lad Museum in Mumbai houses late 19th-century pottery made at the Sir JJ School of Art. Pottery works that came out of the JJ School were popularly known as the Bombay School of Pottery.

12. The Pan-Asian movement was developed to bring Asian people under one umbrella. The main aim of the movement was to reject Western imperialism and colonialism and to consider strengthening existing networks within Asian countries. Sven Saaler and Christopher W. A. Szpilman,

“Pan-Asianism as an Ideal of Asian Identity and Solidarity, 1850–Present,” in The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol 9, no 11 (April 2011), https://apjjf.org/2011/9/17/Christopher-W.-A.Szpilman/3519/article.html

13. Kristine Michael, “The Ceramic Circles: Pioneer Potters of the 20th Century,” in Marg, vol. 69, no. 2 (December 2017), 63.

14. Discussion between Kristine Michael and Sindhura D. M., August 2018. During the 1990s, Pooja Sood curated several exhibitions of studio potters at Eicher Gallery. One among them was a solo exhibition of Ray Meeker in 1992.

15. Refer to Annapurna Garimella’s essay “Designing a Disobedient Show for an Unruly Space,” Domus India, Vol.7, No.2 (December 2017), 30–43 to know more about the exhibition’s design.

Just as clay is in a continuous state of flux between the unfired and fired state, so also is the eventful chronology of its aesthetic and technological history. Throughout the colonial period, pottery was able to maintain its economic and local market base due to the simple production processes and sustainable technology which enabled it to pave the way towards its regeneration as a distinct modern art form in the 20th century. A critical part of the nationalist discourse, along with weaving, pottery played a singular role in the development of Mahatma Gandhi’s and Rabindranath Tagore’s new educational strategies for an independent India through their vision of integrating crafts with skills for life. The craftsman’s place in culture, however, was fractured in the post-Independence spurt of industrialization, new technologies and modern materials which enabled the displacement of the potters’ traditional functional role in rural society. The marginalization of potters in urban areas to the outskirts of the city, shrinking urban and rural markets, and restricted access to clay sites and fuel due to property development and changing land usage are some of the issues that they have faced and continue to face.

The building of links or bridges between the tropes of vernacular and modern art-cum-design is the pivotal point of the Mutable exhibition, which explored the enormous range of cultural practices that deal with aesthetics, function and sustainability. The aim was to show the fluid and relative categories of the craft, rather than reinforce limiting and preservationist approaches. The reformist, idealist and spiritualist voices of pottery’s exponents are largely consonant with the arts and crafts movements of the 19th century, leading to a persistence of the craft through Oriental or Western aesthetics in the search to create a national identity. The development of the schools of art and their teaching of ceramic design, form, function and its ornamented surface, often inspired by regional artistic treatment of surface as in Jaipur Blue Pottery, architectural reliefs or Ajanta Cave paintings, leads one to understand that, eventually, pottery need not be seen as a sub-genre of fine art or only rooted in traditional forms and concepts. Rather, it has developed into a form of contemporary personal expression which engages its audience on its own terms with a characteristic language. As curator Apinan Poshyananda has written, “Tradition should not be

interpreted as the opposite of contemporaneity.” Rather than being perceived as a binary divide, the two have been continuously assimilated, adapted and engaged in an ongoing process of negotiation.1 This holds true for India as well as for some other non-Western countries.

The articulation of this negotiation in aesthetic language has largely revolved around the contribution of a number of individuals on whom this essay will focus. The transnational context of Japan and India involves the contributions of Gurcharan Singh of Delhi Blue Pottery, Kripal Singh Shekhawat of Jaipur, and Deborah Smith and Ray Meeker of Golden Bridge Pottery in Pondicherry (now Puducherry). The ties that link these pioneer potters deal with the long shadow cast by the combined influence of Japanese Mingei craft theory and Western arts and crafts writings on the idealized notion of the craftsman on the formation of the Modernist studio pottery movement in India.

Mingei theory, according to Yuko Kikuchi, 2 was Yanagi Soetsu’s cultural hybridization of craft created by the “negotiating of the borders of Orient and Occident… where Yanagi selected, absorbed, translated and appropriated” arts and crafts theories into the shared common ground of Japanese indigenous context in an original manner. These dealt with the principles of beauty, aesthetic theories and modernist ideas which enthusiastically looked to Japonisme as its inspiration.3 Yanagi explained to a largely Western audience about the canon of beauty for all Japanese people.

He and Okakura Kakuzo (aka Tenshin) were some of the most important theorists in the Mingei movement who also had a great impact on English, Japanese and Indian views of pottery as “the beautiful truthfulness of the domestic handmade crafts.” Yanagi was first a pupil and then friend of D. T. Suzuki, who made a form of Buddhism known to the West. His aesthetic was that of “the seeing eye,” an epithet that Bernard Leach also used for him as he was never a craftsman but an aesthete. Yanagi’s position in Japan is comparable to that of England’s John Ruskin and William Morris.4 Through his book The Unknown Craftsman, he proposed a theory

regarding artistic work and its qualification by beauty against a background of rapid industrialization that was an expression of the spirit of man.

Yanagi’s theory of the “Beauty of Irregularity,” a chapter from an unpublished manuscript titled The Book of Pots, caused a ripple effect in the world of pottery, beginning with Bernard Leach and Hamada Shoji. Here Yanagi is at his rhetorical best, linking spiritualism and craftsmanship. He also discusses Okakura’s Book of Tea (1906), in which the Oriental recognition of the beauty of irregularity and the imperfect is a product of Zen thinking and describes an aesthetic based upon simple naturalness and reverence, which are then equated to freedom. “Beauty must be associated with freedom— freedom is beauty,” he declared, “as the love of the irregular is a sign of the basic quest for freedom.” It is this beauty with inner implications that is referred to as shibui, which can be translated as a combination of adjectives such as austere, subdued, restrained, simple and pure. While explaining the importance of objects in the tea ceremony, Yanagi explains that tea taught people to look at and handle utilitarian objects more carefully than they had before, and this inspired in them a deeper interest and greater respect for those objects. Tea formulated criteria for recognizing beauty through form, colour and design. In the early tea bowls, the masters perceived the virtue of poverty in the world of beauty called shibusa, the humility that may be described as subdued, austere and restrained. Most tea masters preferred the incomplete; they looked for slight scars or irregularities of form. The Oriental, he grandly declared, sought the natural, the irregular and the free—where the Occidental sees only disharmony, the Orient sees harmony. He also quoted Kabir, the Indian mystic poet, in his chapter on the Buddhist idea of beauty.

Okakura Kakuzo’s grand narrative in the Ideals of the East (1903) begins with his statement “Asia is One,” but his discourse rests on the triangulation of three mighty Asian civilizations—India, China and Japan. His trip to India in 1901–02 was facilitated by Sister Nivedita, Swami Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore.5 His

artistic pedagogy also rests on a triangle—tradition, nature and originality; these interact interestingly in his Asian triangle in which Japan is positioned at the apex embodying its artistic heritage, India is represented by the synthesis of the Vedas, and China by Confucius and communist ethics. At a lecture delivered at the World Trade Fair in St Louis in 1904, Okakura affirmed that “we feel ourselves to be the sole guardians of the art inheritance of Asia.” And then again, “Japanese art stands alone in the world” and reveals its tensions of solitude and exclusivity from the rest of Asia which had a colonial history. Okakura was deeply impressed by the revivalist national movement for culture and arts, going on with the Tagores in 1902. On returning to Japan, he sent two distinguished artists of the Nihonga style— Yokoyama Taikan and Hishida Shunso to Calcutta (now Kolkata)—where they met and exchanged opinions and artistic views with Rabindranath and Abanindranath Tagore. The relationship was enhanced further by Rabindranath’s five visits (1916, 1917, 1924, and twice in 1929) to Japan. These encounters brought into contact a remarkable group of intellectuals and artists of Japan and Bengal. They not only influenced Indian modern left

artists but also, in turn, were influenced by the new “wash style” initiated in Bengal; this exchange gave contemporary Japanese art an Indian touch.6 Kampo Arai, a painter of the Nihon Bijutsuin, came to Calcutta in 1916 on Rabindranath Tagore’s invitation. He visited Calcutta and Santiniketan and travelled around India from 1916 to 1918.

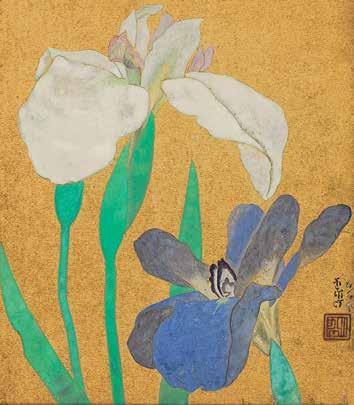

fig.

Shekhawat, Flower study, watercolour on paper made during study in Tokyo Japan, c. 1920s, mixed media on cardboard, h 10.2 x w 9.0 inches (approx. 26 x 23 cm). Collection: Delhi Art Gallery, New Delhi (Image © Delhi Art Gallery, New Delhi)

facing page

left

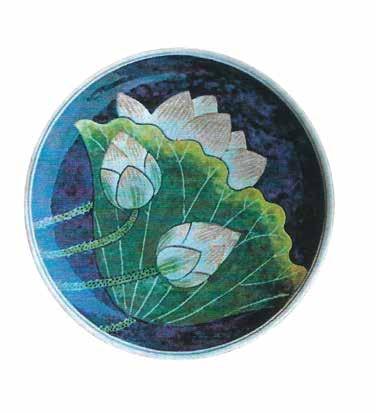

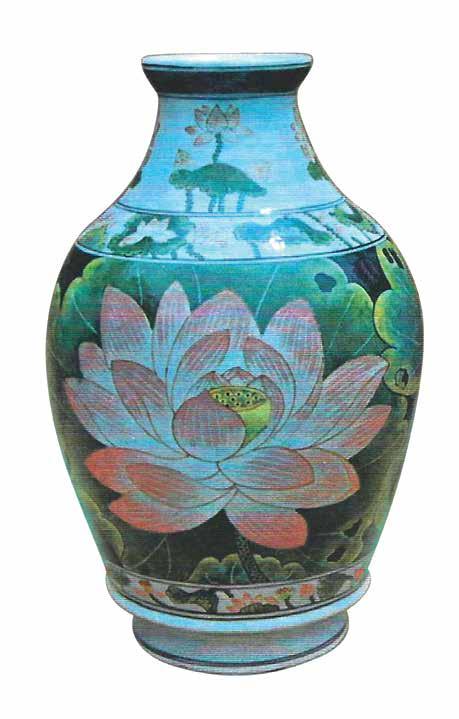

fig. 1.2 Kripal Singh

Shekhawat, Lotus painted tall vase, ceramic, h 14 inches (approx. 36 cm). Collection of the maker (Image © Kristine Michael, New Delhi)

right

fig. 1.3 Kripal Singh

Shekhawat, Lotus design on large plate, ceramic, approximately dia. 12 inches (approx.30 cm). Collection of the maker (Image © Kristine Michael, New Delhi)

Yokoyama Taikan was a student of Okakura and was greatly influenced by his thoughts. He was an important leader in the Nihonga, or “Japanese traditional,” school of modern Japanese art. He was extremely influential in the evolution of the Nihonga technique, having departed from the tradition of line drawing. His style was called “Mourou-tai” (blurred style). His trip to India, made jointly with Hishida, inspired some of Yokoyama’s most important work and also was immensely important for the evolution of Indian Modernism. The visits to Calcutta by a series of Japanese artists from 1902 onwards resulted in a pivotal exchange both of techniques and motifs and influenced important early Bengal Modernists such as Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose, who shared a pan-Asian approach in their quest to establish an indigenous style of art free of Western influence by exploring Japanese ink-wash techniques.7

At the turn of the 20th century, the critical debate on Indian art and craft revolved around the perception of the “traditional.” For Ananda Coomaraswamy, the first Indian art historian who reworked the Western parameters of understanding Indian art, the word “tradition” was a description of cultures founded on an understanding of the spiritual nature of man and his world as a microcosm. For him, “traditional” and “modern” were two polarities. In his writings, India was the epitome of a traditional civilization and his tone is characterized by a nostalgia for the nearly-lost traditional life of India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), which were undergoing radical change because of colonialism, modernity, technology, industrialism and the adoption of the Western lifestyle. He developed his politics through his aesthetics and helped apply the ideas of William Morris’s powerful critique of anti-Victorian industrialization with his other mentor,

Rabindranath Tagore. However, while making use of Morris’s terms, Coomaraswamy departed from him as he considered colonialism a far more important factor in artistic production than class relations.

However, in a country with a strong artisanal base, dealing with revivalism in traditional forms was what Kripal Singh Shekhawat achieved with his teaching and practice of Jaipur Blue Pottery in a systematic gurukul system in both his personal home studio and at the School of Art in Jaipur’s Kishanpol Bazaar.8 His own training—first at the Lucknow School of Art and

later with Nandalal Bose at Santiniketan, from where he graduated as a painter in 1947, and his subsequent exposure in Japan to Oriental painting techniques—led him to develop a new reference point in aesthetics and in creating a market for the local craft. Kripal Singh used the pottery surface as his canvas, mingling all his sensitivity from Santiniketan, the Ajanta and Bagh Caves and his Japanese Nihonga techniques to create a new hybrid canon of decorative underglaze painting. Under the instruction of Nandalal Bose, Kripal Singh and the artist Beohar Rammanohar Sinha worked on the handcrafted and painted Preamble to the Constitution of India in 1949. The illustrations and the decorative borders are quintessentially of the Santiniketan or Kala Bhavana style, and were greatly inspired by the cave paintings of Ajanta and Bagh. At the beginning of each part of the Constitution, Nandalal Bose depicted a phase or scene from India’s national experience and history. The artwork and illustrations (22 in all), rendered largely in the miniature style, represent vignettes from the different periods of Indian history, including Mohenjo Daro in the Indus Valley, the Vedic period, the Maurya and Gupta empires, the Mughal era to the fight for Independence and national freedom. Ajanta was to remain one of Singh’s favourite sources of inspiration for his pottery paintings.

In 1951, he was awarded a fellowship for a three-year diploma to study traditional Oriental painting and decoration at the University of Fine Art, Tokyo. On his way to Japan, he travelled through Burma (now Myanmar), Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong where he did many sketches of daily life. His years in Japan left him with an insight into the works and techniques of Japanese Nihonga artists such as Tanaka Saiho (noted for his flower and bird paintings), Maeda Seison (a member of the Kojikai artistic group), and Kawabata Ryushi (who specialized in large-scale public murals).

He returned to Jaipur in 1954, and under the patronage of Maharani Gayatri Devi of the Jaipur royal family and Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, chose to work on the revival of Jaipur Blue Pottery by heading an art school financed by the All India Handicrafts Board, a government

organization, for the development of crafts.9 He spent a few months with Gurcharan Singh in New Delhi and forged his own techniques based on the old Persian style of blue-and-white painted kashi ware or faience. He learnt all the secrets of the nearly extinct art as it had been perfected in Jaipur in the 19th century, made many changes to make it a modern practice and thereby reestablished an entire tradition. He painted in the Ajanta fresco and miniature painting style on his pottery. Motifs such as the lotus or iris flower and stem in delicate copper blue with cobalt outlines and shades of pink became vibrant stylistic statements (Figures 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3)— showcasing different facets of Indian visual culture.10

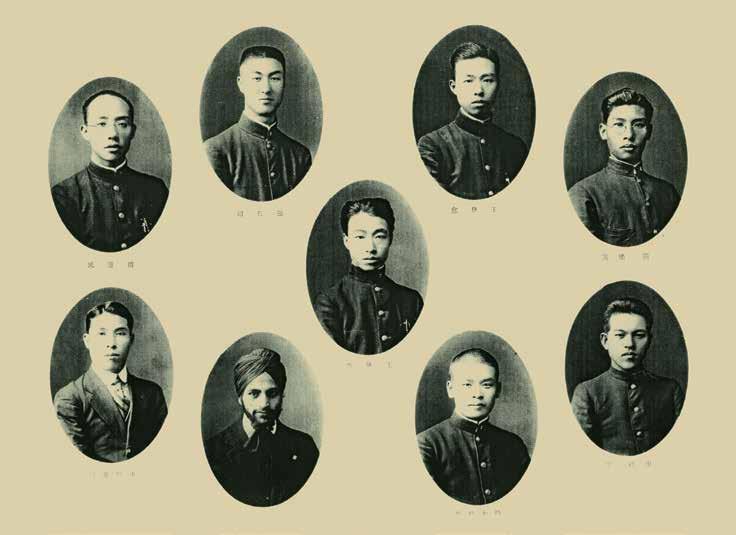

Gurcharan Singh was the first Indian in the Mingei, Euro-American and Theosophist circles in Tokyo (Figure 1.4). He absorbed their ideas and, on his return

to India in the early 20th century, set out on a lifelong mission to realize them in his practice through the Delhi Blue Pottery Trust. He was supported in this by his friendship with Bernard Leach, who formulated the idealized standard of a spiritual and holistic approach to pottery and expounded what was meant by the beauty of naturalness, simplicity and Oriental style through his workshop philosophy (Figure 1.5).11

The seat of the British imperial government was moved from Calcutta to New Delhi after World War I, and a new capital was quickly built. E. B. Havell and Coomaraswamy led a verbal attack on the English planners of New Delhi urging them to use Indian architects and masons in the construction of the government buildings for reasons of economy, excellence and suitability and as a muchneeded example of state patronage of indigenous industry.12 Two important figures were Delhi Potteries owner Ram Singh Kabli and the contractor Sobha Singh. The young Gurcharan Singh joined Kabli as an apprentice and trainee in 1919. Later that year, he was sponsored to visit Japan to attend a two-year diploma course at the Higher Technical Institute in Tokyo, where he would learn the industrial and commercial side of pottery and tile-making. Here, he met the men who were to be the most formative influences in his life—

Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, Yanagi Soetsu, Kawai Kanjiro and Tomimoto Kenkichi (with whom he kept up a lively correspondence). It was during the visits to Abiko that Gurcharan was drawn into the aesthetics of Japanese pottery, raku, and the growing Mingei and Theosophist movements. He was a member of the Garakutashu—a club involving Japanese intellectuals, art collectors, international artists and architects such as Antonin Raymond, who later came to design the Golconde Guest House at Pondicherry’s Sri Aurobindo Ashram, and Kenkichi, who had visited India in 1909–10 on his way to England to meet Leach. Kenkichi would have another Indian apprentice in 1930—Pi Hariharan, who worked at his studio at Ando-mura, Nara.13

Gurcharan visited Korea and China to study and understand their aesthetics and started a pottery collection to take back with him to India, based on

Yanagi and Leach’s advice. In a letter to Bernard Leach in 1920 from Korea, Gurcharan says: I came here to stay for a week, three weeks have already passed and yet I don’t want to leave this place.... How shall I tear myself from these? Coreans resemble so much Indians in dress, customs and act that I have begun to love it next to my motherland. I have made some collections of the old pottery and other old things which I would very much like you to see. I wish to tell you so many things just as a child would tell his adventures to his older brother.14

The following year, in another letter, Gurcharan thanks Leach:

You would be glad to know that I have begun to work under Mr Kenzan, your and Tomi’s teacher, the old raku master... I am glad you received my letters one from Korea and the other from Japan. Please do write me as often as you have time, you know it gives me a great pleasure and comfort. Just now I have received Yanagi’s express letter to

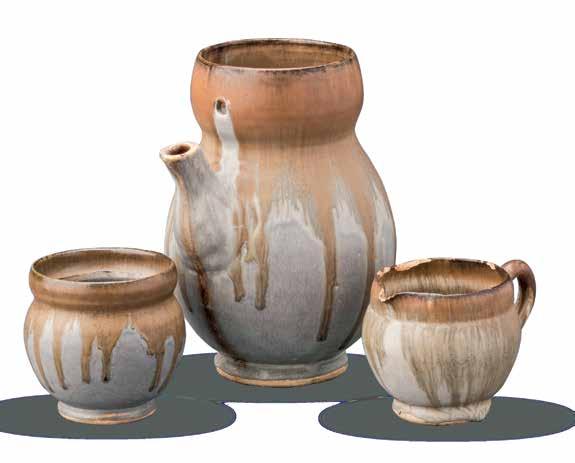

Gurcharan Singh, Blue cups,

fig.

saucers, sugar pot and milk jug, 1970s, stoneware, sugar pot: h 4.5 x d 4.5 inches (approx. 11 x 11 cm), saucers: dia. 5 inches (approx. 13 cm), milk jug: h 5 x d 4 inches (approx. 13 x 10 cm), cups: h 4 x d 2.5 x dia. 3 inches (approx.10 x 6 x 8 cm). Collection: Anuradha Ravindranath, New Delhi (Image © Piramal Museum of Art, Mumbai)

see him at the station as he is going to Korea on a short visit.… I write all this because I know it will give you pleasure, moreover when this is all due to your kindness and contacts.15

After his return to India, he communicated with Leach his unsettled feelings in a moving letter in 1921: To me, my country is a revelation now. Japan educated me to see my own country, feel it and read the inner meanings of its past. It was a pleasant shock to see how my vision had changed…. I shall wish you to come some day and put up in that hut and live with me thinking of the days—in Japan…. I have heard from Yanagi, who sent the beautiful handbook of Korean art a few days ago, I have seen its photographs over and over again, at least hundred and fifty times.16

For the next 16 years after his return from Japan, Gurcharan was determined to establish studio pottery in India. From this time on, he marked his pots with his signature in Urdu. In 1926, the pottery moved to its well-known location on what is now Ring Road in Delhi. It was Leach and Hamada’s adherence to look at the simplicity of forms and glazes in traditional pottery that inspired Gurcharan to take on the copper blue glaze (Figure 1.6) of Islamic ceramics—evidence of which was all around him on tombs such as Jamali Kamali and Chini Ka Rauza in New Delhi and Agra. The Persian blue copper glazed tiles caught the eye of Sir Edward Lutyens and Herbert Baker who ordered hand-pressed, handpainted tiles for Parliament House, Tis Hazari Courts and Kerala House. In 1954, the first exhibition was held in New Delhi of glazed stoneware including urns, vases, plates and bowls in muted shades of grey, green and blue glazes. Gurcharan visited Leach in England for the first time in 1958; he would later visit again, in 1977.

The following year, Gurcharan was able to purchase land at the Artists Community at Andretta in Himachal Pradesh, where his friends—eminent painters Sobha Singh and B. C. Sanyal, and theatre personality Norah Richards—had created a haven for artists at the foothills of the Himalayas. The pottery made

from this time was often inspired by the local Kangra pottery forms as he encouraged the use of the local terracotta clay. Gurcharan moved to Andretta with his son Mansimran and daughter-in-law Mary in 1984 and started the Andretta Pottery and Craft Society— an artist colony and community where local potters were trained in modern shapes and slipware and established it as a regional centre for textile crafts and natural dyes (Figure 1.7).

In 1979, Gurcharan published Pottery in India, the first Indian text for studio potters in the country. This book provided an invaluable reference guide to the practising

potter, collector and student. He had a penchant for basing his shapes on traditional Indian metal and terracotta vessels like the mendicant’s water jug, or the lota, the hookah and the sadhu’s begging bowl. From the mid1970s, his engraved lotus on plates and dinner services with a simple celadon glaze was the hallmark of their pottery. As Leach said, “The pot is the man, his virtues and vices are shown therein—no disguise is possible.”

Gurcharan Singh as well as Deborah Smith and Ray Meeker based their studio teaching practice on this pedagogical side of the Leach tradition, combined with the immersion in philosophical ideas, for all of their students and apprentices at New Delhi and Pondicherry, respectively. This provided the foundation for the 20th-century Indian studio pottery movement and was a part of the counterculture and green movement which sought alternative ideas and lifestyles based upon the “small is beautiful” idea, Zen Buddhism, environmental conservation and viewing spiritual alternatives to cosmopolitan, urban living.

Deborah Smith majored in Japanese language and culture at Stanford University in the US in 1967. The following year, she travelled to Japan and spent a year as an apprentice to Toshu Yamamoto in Imbe in the Bizen region, where traditional pottery is fired unglazed for many days in a wood-burning kiln. It gains a natural glaze from the fly-ash vapours in the kiln. She also studied pottery with Araki Takako in Nishinomiya. On

her return to the University of Southern California in 1969, she worked with Susan Peterson, a ceramic artist and professor who was planning to visit Japan in 1970 to write a book on Hamada. In Mashiko with Susan Peterson, Deborah absorbed the environment and teachings of Hamada. Around this time, she was also introduced to Deborah and Bob Lawlor, one of the first settlers at Auroville, and the teachings of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother at the East West Centre in Los Angeles. When she visited Pondicherry in 1970, she (and later Ray Meeker) was offered space on land leased by the Ashram to set up a pottery studio with the permission of the Mother. The name “Golden Bridge” (Figure 1.8) was taken from a quotation of Sri Aurobindo’s poem, Savitri (“She is the golden bridge—the wonderful fire….”).

Ray had earlier been an architecture student at the University of Southern California and a student of Susan Peterson, which is where the two had met. He joined Deborah in 1971. It took them several years before they were able to get the kiln, clays and glazes tested. Their first pots looked like Japanese country pottery with reduction-fired stoneware with glazes that used natural materials like wood ash. Students were welcomed from the onset and, slowly, a community of potters began to grow.17 The pottery workers were from other building crafts such as masonry and carpentry and were trained as they were on site to help with the building of the pottery sheds. They, in turn, left and started their own small workshops in the region. Although similar to Japanese pottery, the pots themselves slowly began to reflect the influence of Indian form and culture, becoming a true mingling of a transnational, homogenous aesthetic and establishing what is now distinctly known as “Pondicherry” pottery.18

Today, the many studio-pottery exhibitions held all over the country are evidence of its huge popularity and demonstrate the diverse creative potential of the crossovers of the fields of craft, design, sculpture and architecture, thereby opening up new fields of creation in the visual culture of India.

1. Apinan Poshyananda, Modern Art in Thailand: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

2. Yuko Kikuchi and Yunah Lee, “Transnational Modern Design Histories in East Asia: An Introduction,” Journal of Design History, Vol. 27, No. 4 (2014), 323.

3. Japonisme is a term coined by the French critic Philippe Burty in the early 1870s. It describes the craze for Japanese art and design that swept France and Europe after trade with Japan resumed in the 1850s, after it had been closed to the West since about 1600. The Japonisme aesthetic encouraged elongated pictorial formats, asymmetrical compositions, an aerial perspective, spaces emptied of all but abstract elements of colour and line, and a focus on singularly decorative motifs. “Japonisme,” Tate, online, accessed September 18, 2018, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/j/japonisme

4. In late 19th-century Britain, theorist and critic John Ruskin and the designer, writer and activist William Morris began pioneering new approaches to design and the decorative arts. They shared a belief in the superiority of medieval crafts and that a nation can be judged by its aesthetic productions; that an immoral nation is incapable of creating great art; and that only non-mechanical, freely creative crafts could produce genuine beauty. “The Ruskin–Morris Connection,” Anthem Press, blog, http://www.anthempressblog.com/2014/09/25/ the-ruskin-morris-connection/

5. Sister Nivedita was an Irish-born schoolteacher who was a follower of the Indian spiritual leader Swami Vivekananda and became an influential spokesperson promoting Indian national consciousness, unity, and freedom. Following Vivekananda’s death in 1902, Nivedita turned her attention more toward India’s political emancipation. She objected strongly to the partition of Bengal in 1905 and, as part of her deep involvement in the revival of Indian art, supported the Swadeshi movement that called for the boycott of imported British goods in favour of domestically produced handmade goods. She continued to give lectures in India and overseas, promoting Indian arts and the education of Indian women.

6. In his rejection of the colonial aesthetic, Abanindranath Tagore turned to Asia, most notably Japan, in an effort to imbibe and propose a pan-Asian aesthetic that stood independent of the Western, academic one. Japanese scholars like Okakura Kakuzo left a lasting impression, as the Bengal school artists learnt tempera and wash techniques—in which a thin layer of colour is applied—from them, innovating and modifying it to better suit their own needs. “Visual Galleries: Bengal School,” NGMA, online, accessed September 18, 2018, http://ngmaindia.gov.in/sh-bengal.asp

7. Moving away from oil painting and subjects that were popular with both the British and Indian intelligentsia, Abanindranath Tagore looked to ancient murals and medieval Indian miniatures for inspiration both for subject matter as well as indigenous material such as tempera. The philosophy of a pan-Indian art that he developed found many enthusiastic followers and this came to be known as the Bengal school. The style developed by him was taken up by many of his students, and others who formed the nationalist art movement often were called the Bengal school, even though the style and philosophy spread well beyond the borders of Bengal. They sought to develop an indigenous yet modern style in art as a response to the call for “swadeshi” to express Indian themes in a pictorial language that deliberately turned away from Western styles. Ibid.

8. A gurukul was a type of residential education system in ancient India with shishya, or students, living near or with the guru, in the same house. The guru-shishya tradition is a sacred one in Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism in India.

9. Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (1903–1988) played an important role in the struggle for Indian Independence and was a key figure in the international socialist feminist movement. She also revived Indian handicrafts and became the country’s most well-known expert on thousands of craft and performing arts traditions. The Form chapter discusses Chattopadhyay’s legacy further.

10. Kripal Singh’s visionary combination of miniature painting themes on pottery surfaces showed complex shading with mineral compounds under a transparent glaze using

traditional Rajasthani squirrel-hair brushes.

11. Bernard Leach was a British studio potter and art teacher regarded as the “Father of British studio pottery.” The Shift chapter has an expansive discussion on Leach and studio pottery.

12. E. B. Havell, as principal of Calcutta Art School (1896–1906), introduced certain curricular reforms making Indian art the basis of teaching. He wrote a series of books on Indian art history from what he considered the Indian point of view, inspiring an art movement which took Indian artists back to their own ancient traditions. Osman Jamal. “E. B. Havell and Rabindranath Tagore.” Third Text 14, No. 53 (2000), 19–30. Architexturez South Asia, https://architexturez.net/doc/azcf-182814.

13. Meghen Jones, Tomimoto Kenkichi and the Discourse of Modern Japanese Ceramics, Boston University Thesis, 2014. A letter from Tomimoto to Leach dated August 10, 1930, states: “We are working hard these days and from June we have begun our work making the hundred exhibits for London. At present, we are three working. Mr Koshiro is with us...and also one Mr Hariharan from India, a friend of Mr Hasegawa. He has come to learn pottery.” In Atorie, Vol. 8, No. 5, May 1931, Ishimaru Juji critiques Hariharan’s ceramics, “Pi Hariharan’s small jar and other works are, more than anything, copies of Tomimoto.”

14. Letter from Tento Ryokan Shoro, dated August 25, 1920, Keijo, Korea.

15. Letter from Gurcharan Singh to Bernard Leach dated January 9, 1921, from Higher Technical School, Asakusa, Tokyo.

16. Letter from Gurcharan Singh to Bernard Leach dated January 9, 1921, from Higher Technical School, Asakusa, Tokyo (Acc. No 2350 Craft Study Centre, Holborn, Bath).

17. Deborah Smith and Ray Meeker in discussion with the author, 1997.

18. Golden Bridge Pottery’s classic Oriental feldspathic glazes over tenmoku and chun, fired in a wood-burning threechamber climbing kiln, are the trademark stoneware of the Pondicherry style.

Indian Ceramics

This chapter analyses the cultural and artistic movements that have contributed to the forms, materiality, techniques, design, making, ideologies and philosophies that have shaped ceramic and clay art in India. It charts the development of Pan-Asian movements and the continuation of a Gandhian vision of an ideal society, and how these came to inhabit specific practices. Many of the ceramicists discussed here have embraced or been impacted by the “philosophy of the East,” the practices of British ceramicist Bernard Leach, and Japanese potters Soetsu Yanagi, Kenkichi Tomimoto and Shoji Hamada, who were prominent members of the Mingei folk-art movement.1 Collectively, these movements and the ideas that held them together led to the beginning of the studio-pottery practice in India.

Industrialization and art and craft movements, in England, Europe and the United States and in Asia in the early 20th century, laid the foundation for studio-pottery practice across the globe. In India, after Independence, many modernist makers looked to Japan as well as Europe to redefine the idea of nationhood and thereby “Indian” art and craft. In the Object chapter of this book, I discuss Visva-Bharati University at Santiniketan which

was conceptualized and founded by Rabindranath Tagore in undivided Bengal. Tagore used a holistic approach in the teaching of fine arts and Visva-Bharati became a school of modernist approaches in pedagogy and practice, which not only looked at the West and the East, but also took inspiration from local art forms and the surrounding natural environment. It was probably the first place where a studio-based practice (as opposed to a practice emanating from a workshop or a factory) was established in India.

To further define studio-based practice, I look to art historian Caroline A. Jones who has written extensively on the subject in the context of the US. In her book Machine in the Studio, she argues that a maker in a studio participates in the complete creation in terms of labour and concept in the production of works and also retains authorship of the works.2 This studio space, which is comparatively small in size, allows for a form of artistic production where a maker shifts between the roles of an artist, designer, labourer and manager.3 As a space, it also becomes a gallery for the display and sale of works. In India, such studios often become pedagogical spaces for training younger practitioners.4

In the context of pottery in India, the concept of the studio is different from the workshop of a hereditary potter, which is usually established within the boundaries of the home and in which family members are involved in the production.5 However, many pottery studios employ hereditary potters as labourers or as skilled master craftspeople. A studio-based practice produces works for exhibitions (galleries, art fairs, and biennales) on commission (public and private), and makes products in batches for sale in lifestyle boutiques and online.6

The modernization approach of many institutions such as the National Institute of Design (NID), Sevagram, and the Khadi and Village Industries Commission looked at traditional forms and proceeded to combine them with new materials and techniques to create products for the new urban market. In contrast, studio pottery drew most of its motivation from Japan and Britain as well as India. Unlike Japan’s studio potters, who participated in the Mingei movement using techniques and forms that were part of a familiar legacy which they sought to revive, people who became studio potters in India based their practices initially on imported or new forms and techniques. They travelled to East Asia, and—when back in India—experimented with pottery, setting up studios for the first time. Some began to make pots in colleges or through various apprenticeships, learning pottery because of their passion for clay as a material.

The practice of studio pottery in India is situated in a complex framework wherein there is a widespread interest among studio potters in indigenous potters and pottery, to either utilize their craftsmanship or to preserve the craft. Hereditary and studio potters differ from each other in many ways. The former make utilitarian vessels using low-fired clay for local markets as well as votive objects and idols of deities. Their making is always linked with functionality and buyers’ interests. Studio potters make functional ware as well as sculptural works which are exhibited in art galleries and bought by collectors. Such makers use glazes, stoneware clay and diverse kilns such as the anagama to fire their objects. Unlike most traditional potters, studio potters

also hold sole authorship for their creations, often branding them and the functional vessels they make to fit sophisticated urban lifestyles.

Ceramics within the discourse of studio-based practice tends to move between the domain of “art” and “craft.” The idea of art is usually associated with painting, sculpture, printmaking and installation. These media appear to offer certain formal and aesthetic experiences which allow viewers to think beyond the material. Craft, on the other hand, is generally understood as utilitarian or decorative, is made from materials such as fibre and clay, and serves a purpose. Unlike craft objects which have a dual orientation as objects which are usable and which are meant for display, art objects have no “usability” except as objects to be viewed and contemplated.7 Some ceramic objects break this binary and make the distinction between function and contemplation ambiguous. Such works become successful when a potter is able to create a productive dialogue between an object meant to be used and one meant for display. This is exemplified by two examples: Ray Meeker’s 71 Running (2014), in which the teacups are not for drinking tea but are meant to be exhibited in galleries, and Ange Peter’s Dragon Teapot “Emergence”, which is discussed further in this chapter.8

Along with artistic experimentation, Indian studio potters also structure their practice around the issue of livelihood. Many makers produce tableware in order to sustain themselves. These functional pots are made on a kick or an electric wheel. They are fired in wood or gas kilns by trained employees, especially in the studios of Auroville.9 Most of these employees come from the surrounding villages and some of them also belong to the hereditary potter community. Since its inception, Golden Bridge Pottery (GBP) has become a major historical and pedagogical presence in Indian ceramics—which is discussed further in the chapter. Many studio workers who trained at GBP learnt to use stoneware clay and fire in different kilns. Over a period of 40 years, several such studio-trained potters have migrated to other Auroville studios and some have started their own production units.10

Utilitarian ware is planned much before it is made. In order to produce the numbers that are needed to meet MoQs (minimum order quantities) at a price that sustains the practice and provides a livelihood, a studio potter has to plan the entire process and make use of simple forms, good glazes and readily available clay. While making the entire run of vessels, a skilled potter

has to execute the work rather than plan the object; that is why it is possible for a trained assistant to take the pre-planned designs and produce them in multiples. There is no need for a great deal of primary or first-order design consciousness at the production stage of making; the assistant’s labour is used prior to the final throwing. In throwing, the skill becomes important in order to control materials and tools for optimal results.11

Studio potters make their sculptural works in the same space where they make functional ware. But these are built by hand and are made in various sizes, usually much larger than any functional ware—differentiating sculpture as an art form from “useful” craft. The wheel allows potters to create forms within the limits imposed by the size of wheel and the energy required to turn it. It forces the body, the mind and the hand to follow in a synchronized rhythm to achieve the desired form. The hand becomes a device to mould a certain shape. For example, maker Sabrina Srinivas throws a pot on a wheel before starting a sculptural work. While “playing” with clay in this manner, she focuses on the idea of creating a future sculpture—much in the way a painter might make an initial sketch before actually working on the painting.12

Auroville-based Michel Hutin provides another perspective on the limitations that wheel-throwing poses for some ceramicists because they feel it demands less conceptual labour. Hutin, after years of working on a wheel, began to feel that throwing a pot was a “twodimensional” process.13 By this, he means that a potter throwing clay on a wheel has to work to make the pot look similar from all sides and that this can detract from the experience of working creatively with clay.

Ceramicists desire to engage with the user or viewer through their work. The user is seen as someone who participates in the life of a utilitarian pot by living with it; in the process an appreciation of its functionality, its materiality and its presence develops. However, a lack of awareness for the object also grows as it gradually becomes an everyday object. Its transition from being a “prized” purchase to a much-used product is assisted

by the uniformity of design which is present in most functional ware. These products often look the same from all sides and do not call attention to themselves by looking different when viewed from various angles. Therefore, the process of making pots on the wheel can then become unsatisfactory to someone like Hutin, as the making involves repetitiveness in form and in method. Hence, he may move towards creating handbuilt, sculptural objects. The historical divide between the anonymous maker of mass-produced vessels and the singular, authored maker and his or her objects remains firm—a divide which the Mingei movement and many others have attempted to address.

Hand-built clay objects support a wide range of forms wherein the hand is the main tool to manipulate the clay. Such works allow potters to become individual sculptors; a hand-built ceramic object allows its maker— within the spatiality, materiality and temporality created by the object—to transition into an artist. Art historian Andrew Perchuk has written about the process which California sculptor Peter Voulkos (1924–2002) followed in order to make his large-scale ceramic works. He made non-functional objects with step-by-step joining, creating shapes, painting, moulding, firing and sometimes refiring. Perchuk described Voulkos’s process of making as an “assembly line” because each technical act was performed sequentially in order to maintain the stability of the growing form.14

For makers who throw clay on the wheel and practise hand-building with equal deliberation and passion, the two processes provide different creative experiences. It is important to view these two orientations as being a part of a continuum rather than as polarities. Wheelthrown works allow makers to hold firm to their foundational training and display a subjectivity which is grounded in a tradition of collective knowledge and tacit skill. If a sculpture breaks the mould, so to speak, and allows for a type of authorship premised on the idea of the modern artist, functional ware allows for livelihood, for easier forms of community and for the discipline that comes from reinventing something familiar on a daily basis. To further explain these two distinct practices

from the perspective of a modern potter, the words of Japanese philosopher and Mingei movement founder Soetsu Yanagi are useful. He wrote, “…things that are highly individualistic are unsuitable for daily use. The assertion of one individuality is almost sure to produce a clash with another individuality.”15

Contemporary studio potters work within such ideas and make useful pots along with non-functional objects. Adil Writer, Sabrina Srinivas, Ange Peter and Michel Hutin carry forward two approaches to clay. One is the Japanese—more specifically the Mingei—way of making useful pots; another is to make sculptural works. In India, ceramic sculpture within a studio practice was first put forward by the Pondicherry-based Ray Meeker who taught many other ceramicists who can collectively be referred to as the students of the “Ray Meeker School.” His work and that of his students will be discussed later in this chapter. For example, Ange Peter—who makes forms such as the teapot—breaks with its recognized usability by assembling refined irregular shapes and forms (Figure 2.1). In such a work, clay becomes the material to create an idea or concept, and utilitarian ware loses its fundamental function and becomes an object for collecting, as noted by art historian Scott Watson. It is thus sold for a far greater price than functional ware.16 Similarly, many artists of the late 20th and early 21st century have used readymade functional objects in their works in the context of making an installation in which the concept of the work and the ideas that buttress it are more prominent than skill and material.17

Using a low-fired clay vessel to cook and store food is nothing new in India. However, clay ritual vessels are considered impure once they are used and are discarded; daily cookware is used for a longer period of time, but, eventually, such terracotta pots too are discarded to ensure hygiene because low-fired pots are porous and thus can be colonized by bacteria. British colonization and a new kind of urbanization changed the domestic ceramics in the country.

fig. 2.2 Gurcharan Singh,

Coffee pot with sugar pot, cups and saucers, 1970s, stoneware, coffee pot: h 7 x d 6.5 x dia. 6 inches (approx. 18 x 17 x 15 cm), cup: h 4 x d 2.5 x dia. 3 inches (approx. 10 x 6 x 8 cm), sugar pot: h 4 x d 4 x dia. 4 inches (approx. 10 x 10 x 10 cm), plates: dia. 5 inches (approx. 13 cm).

Collection: Anuradha Ravindranath, New Delhi (Image © Piramal Museum of Art, Mumbai)

During the British Raj, many aristocratic and elite families used imported bone china tableware to serve their European guests and, later, themselves.18 In the 1930s, luxury crockery for the Indian upper classes began to be made by recently established companies such as Gwalior and Bengal Potteries.