PAPER TRAILS

Modern Indian Works on Paper from the Gaur Collection

Edited by Tamara Sears

Edited by Tamara Sears

Edited by Tamara Sears

Edited by Tamara Sears

Modern Indian Works on Paper from the Gaur Collection

India is a nation of conflicting realities, where the old and the new, the traditional and modern regularly coexist. Visual narratives are vital resources in telling stories and facilitating communication. Here, the artists are concerned not solely with telling their own tales but also with exploring what it means to live in a nation steeped in tradition.

Within the context of modern and contemporary India, works on paper offered artists a way of cultivating transnational modernist expression while continuing to explore the potential of a medium that had deeper roots in older artistic traditions native to the subcontinent.

This volume features over 100 watercolors, drawings, etchings, sketches and lithographs by senior Indian modernists, born primarily before the 1950s and who came of age in the decades directly following Independence in 1947. These artists span the transition from colonial to post-colonial India, embracing both realism and abstraction, exploring complex metaphors, and making political statements that directly engage India’s past, present, and future.

With contributions by Tamara Sears, Michael Mackenzie, Paula Sengupta, Emma Oslé, Darielle Mason, Rebecca M. Brown, Jeffrey Wechsler, Kishore Singh and Swathi Gorle this book accompanies the exhibition at Grinnell College Museum of Art, drawn from the collection of Umesh and Sunanda Gaur and curated by Prof. Tamara Sears.

With 149 illustrations

from the Gaur Collection

EDITED BY

WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY

TAMARA SEARS MICHAEL MACKENZIE PAULA SENGUPTA EMMA OSLÉ DARIELLE MASON REBECCA M. BROWN JEFFREY WECHSLER KISHORE SINGH and SWATHI GORLE

First published in India in 2022 by

Grinnell College Museum of Art

1108 Park St, Grinnell, IA 50112, United States

in association with

Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati, Ellisbridge Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

T: +91 79 40 228 228

F: +91 79 40 228 201

E: mapin@mapinpub.com www.mapinpub.com

in conjunction with the exhibition ‘Paper Trails: Works on Paper from the Gaur Collection’ from September 27 to December 10, 2022, at the Grinnell College Museum of Art, Iowa (USA).

Text © Grinnell College Museum of Art Images © Umesh and Sunanda Gaur except those mentioned under Sources of Illustrations on p. 232.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral rights of Tamara Sears, Michael Mackenzie, Paula Sengupta, Emma Oslé, Darielle Mason, Rebecca M. Brown, Jeffrey Wechsler, Kishore Singh and Swathi Gorle as authors of this work are asserted.

North America

ACC Art Books

T: +1 800 252 5231

F: +1 212 989 3205

E: ussales@accartbooks.com www.accartbooks.com/us/

United Kingdom, Europe and Asia

John Rule Art Book Distribution 40 Voltaire Road, London SW4 6DH

T: +44 020 7498 0115

E: johnrule@johnrule.co.uk www.johnrule.co.uk

Rest of the World Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

ISBN: 978-93-94501-07-2

Copyediting: Mithila Rangarajan / Mapin Editorial

Proofreading: Marilyn Gore / Mapin Editorial Design: Deanna Luu

Production: Mapin Design Studio Printed in China

Anne Harris, President, Grinnell College Susan Baley, Director, Grinnell College Museum of Art Tamara Sears Michael Mackenzie Tamara Sears

Paula Sengupta Emma Oslé Darielle Mason

The gathering of artists and audiences in this exhibition creates community around crucial issues of human experience and society. Through the vision of Umesh and Sunanda Gaur, Grinnell College has now had the honor of twice hosting the conversations, excitement, realizations, and further research that their collection of Indian art fosters. Coming to a small town in Iowa to think globally is not as paradoxical as it may first appear, for it speaks to the dynamic of the expansiveness of the art featured in this exhibition: works on paper occupy a specific and most often physically small place but, through interactions, the exchange of ideas, and the enthusiasm of shared experience, they have an expansive reach into the human imagination.

The act of gathering in front of a work of art, or over the pages of this catalog, puts viewers in community with artists and with each other. In this sense—and in this exhibition—art simultaneously is and creates a site for a community of inquiry. Works on paper have their materiality in common with books, which they then manipulate in scale, intensity, color, and, of course, content. In the material commonality between works on paper and books, we find the idea of knowledge, as human societies have long used books to codify what is known, imagined, and desired. In the material manipulation that works on paper creatively engage, we find the element of wonder: that two dimensions could project and provoke such depth of emotion, so many perspectives, and reach out so far into human experience. Knowledge and wonder are at the dynamic center of a thriving community of inquiry, and this exhibition brings both at every turn.

In its work of gathering and creating community, and in that community being one of curiosity and connection, this exhibition is doing the crucial work that institutions like Grinnell College and other sites of inquiry engage: bringing people together in a shared experience to create knowledge and learn from it—ideally and practically for the betterment of the

human condition. In the brilliant work of curator Dr. Tamara Sears, this exhibition enacts the work of the humanities as well, engaging the human experience in terms of space and place, identity, critique, myth and religion, storytelling, and the open invitation of abstraction. It also engages the work of the humanities by asking questions of us through its content and curatorial arrangements. A viewer of this exhibition is a participant and can find all of the joys of discovery of being a student in the questions and issues the works of art bring forth.

Art creates community; it also creates time—welcome and necessary time to think, consider, and critique. In a fascinating simultaneity, art both takes and creates time: it takes time to make, to come into being, both intellectually and materially. Once the work of art exists, it creates time by being gathered in a marvelous exhibition such as this one and inviting viewers into contemplation, by stilling them to wonder, and engaging us in a different pace of thinking and feeling. We have to work, perhaps harder than ever, to find that time for critical thinking and we must, because it is in that time that our understanding of the human condition deepens, and it is in that time that our creativity in addressing the challenges to human thriving awakens.

I noted at the beginning of this foreword that this exhibition is the second one from the Gaur Collection that Grinnell College has had the honor to host. Active in this renewed partnership is the dynamic of relationships that I find important to acknowledge as we consider the works of art in this exhibition. Of the many experiences that art is and creates, that of being a repository of relationships is crucial to the fostering of a community of inquiry that is itself so important in institutions like colleges and human societies. Within the physical memory of these works on paper are the relational gestures of artists, gallery owners, collectors, and curators, atop of which are layered the gazes and words of viewers. Looking at the works of art in this exhibition will put you in relationships with its artists and its other viewers and the societies in which they all create and exist. In those relationships exist endless possibilities of connection, discovery, and realization as the emotional, intellectual, and social work of the work of art takes place. I warmly welcome you to Grinnell College and wish you deeply meaningful experiences and exchanges in your engagement with Paper Trails: Modern Indian Works on Paper from the Gaur Collection.

“Our motivation to collect modern and contemporary Indian art is the pure joy of collecting… We also feel that our enjoyment of collecting is greatly enhanced by sharing the collection with a wider community of art lovers. In particular, we greatly enjoy working with museums in promoting modern Indian art in America.”

The Grinnell College Museum of Art is grateful to Umesh and Sunanda Gaur for sharing their collection with our audiences in rural Iowa. The Gaurs’ generous spirit is reflected in their dedication to the educational impact of the collection when it is exhibited—especially in an area where there are few opportunities to view modern and contemporary art from India.

In 2017, the Museum hosted the exhibition Many Visions, Many Versions: Art from Indigenous Communities in India, organized by International Arts and Artists, from the Gaur Collection. The positive response to that exhibition led to Paper Trails: Modern Indian Works on Paper from the Gaur Collection, displayed in the Museum’s Faulconer Gallery from September 27 through December 10, 2022.

Paper Trails, featuring about a hundred paintings, drawings, and prints on paper, offered Grinnell College the opportunity to collaborate with faculty and students at Rutgers University. The exhibition was curated during a seminar on curatorial studies at Rutgers University’s Department of Art History. Professor Tamara Sears, a specialist in South Asian art and architecture, taught the doctoral level course, with student participation from Emma Oslé, Swathi Gorle, Margo Weitzman, Sopio Gagoshidze, William Green, and David Cohen.

During the Spring 2022 semester, Michael Mackenzie, Art History Professor at Grinnell College, taught an introductory course in Indian art and assigned his students to do research about works included in Paper Trails. The text written by his students will be used as wall text for the exhibition at Grinnell College. Dr. Mackenzie’s primary specialty is German

modernism between the World Wars, with additional academic interest in the art of India. His knowledge of modernism and Indian art reflects the origin story of the Gaur Collection, which began 25 years ago with works by members of the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group, a short-lived movement founded in 1947 to celebrate traditional Indian painting while acknowledging European and American Modernism.

Professor Sears and Professor Mackenzie also wrote essays for the catalog. Additional contributions were made by Paula Sengupta, Emma Oslé, Darielle Mason, Rebecca Brown, and Jeffrey Wechsler. Jeffrey Wechsler also served as a curatorial consultant for the exhibition. The Museum is appreciative of each scholar’s role in this publication. We also wish to thank Deanna Luu who designed the catalog, generously funded through a grant from the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation.

Former Museum Director Lesley Wright, who retired in December 2021 after 22 years at Grinnell College, wrote the successful grant application to the Carpenter Foundation. Associate Director Daniel Strong has played a critical role in managing the details for the exhibition and its accompanying publication. I also want to acknowledge the other Grinnell College Museum of Art team members: Jodi Brandenburg, Museum Guard; Amanda Davenport, Administrative Assistant; Jocelyn Krueger, Collections Manager; Milton Severe, Director of Exhibition Design; and Tilly Woodward, Curator of Academic and Community Outreach.

We express gratitude to Shuchi Kapila, Professor of English at Grinnell College, for her enthusiasm in bringing both exhibitions from the Gaurs’ collection to Grinnell, through her leadership role in the College’s Institute for Global Engagement.

As always, the Museum is deeply appreciative of the support of President Anne Harris and the Grinnell College Board of Trustees. We are proud of the way this exhibition reflects the core values of the College: excellence in liberal arts education, a diverse community, and social responsibility.

Finally, we again extend thanks to Umesh and Sunanda Gaur for their dedication to collecting art connected to their cultural heritage and for sharing their collection with a wider community. This project would not have been possible without their passion for modern and contemporary art from India.

It gives me great pleasure to introduce the catalog to the exhibition Paper Trails: Modern Indian Works on Paper from the Gaur Collection, curated by Dr. Tamara Sears. This is the second exhibition of works from the Gaur Collection of modern and contemporary Indian art to be held at the Grinnell College Museum of Art, the first being Many Visions, Many Versions: Art from Indigenous Communities in India, in 2017. That earlier exhibition focused on what are sometimes called the “non-canonical” arts of various tribal peoples in India. In this case, the works in the exhibition are fully “canonical,” in the sense that they are part of the mainstream of modern and contemporary developments in India since Independence in 1947. The Gaurs have built up a collection of great depth and completeness, an almost encyclopedic overview of the complexity and diversity of art in India over the seven decades since Independence. The connoisseurship which they have developed in their collecting practice has enabled them to focus on the materiality of the art object, especially works on paper, and to be attentive to the skill of the printing, the freshness of the plate, the quality of the paper support, as well as the immediacy of the artist’s touch, whether with burin, etching needle, or brush. An exhibition of such works, with their rich materiality and intimacy of scale, offers an American audience the opportunity to experience up close the diversity of the work of modern and contemporary Indian artists.

Although I myself am a specialist in European art, specifically German modernism in the 20th century, I have also been privileged to teach an undergraduate course on the history of Indian art for many years, most recently at Grinnell College. I was first smitten by the sensuous and expressive beauty of Indian art at a major exhibition of an important private collection of ancient and medieval sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1997. After

I saw that exhibition, I rushed back to the classroom to share these aesthetic pleasures with my students, forgetting in the first flush of discovery that my scholarly discipline, and the theoretical positions of modern and contemporary art, had taught me to treat such subjective judgments with suspicion, and to avoid them as unprofessional. And, after

all, my appreciation of premodern Buddhist and Hindu art was predicated on a certain Eurocentric, Orientalizing conception of Indian art as essentially static, its greatness located in an unrecoverable past. It had nothing to do with my primary work as a historian of modern art, and could not, so I presumed, trouble the categories in which I thought about that work. I was as yet unaware that there even was modern art from India. It was only after the appearance of Partha Mitter’s history of Indian art, in 2001, which included several chapters at the end on modern and contemporary art, that I followed Indian art into the modern era.1 And even still I persisted in thinking of it as some sort of secondary or provincial reflection of European modernism, peripheral to the main line of development. It took longer yet to begin to decenter or “provincialize” Europe and European modernism, to borrow a phrase from the post-colonial theorist Dipesh Chakrabarty.2 Today, I try to think with my students about how the work of South Asian artists, those who work in Asia and those who work in Europe and America, is central to the story of modern and contemporary art, not peripheral to it.3 What makes the Gaur Collection so important in the US, and what makes exhibitions like this one so important, is the opportunity to see and think about how Indian art is part of the story of modernism, to see Indian art that is not only beautiful but also aesthetically rigorous, powerfully expressive, and contextually complex.

Let us take up the thread of that story for a moment, if not at the starting point—for the question of starting points inevitably prevents the story from beginning—then at a crucial juncture. In 1919, two innovative art schools were founded, each with the goal of reforming not only art education, but the whole student and, eventually, the nation. One school was Kala Bhavana, the art school of Santiniketan University, outside the city of Calcutta (then the capital of the British Raj in India and now called Kolkata), founded by the writer and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore. The other was the Bauhaus in Germany, founded by architect Walter Gropius. The two schools had similar objectives: to slough off an ossified academic system imposed by a spiritually inert imperial patronage, in order to allow a more authentic individual and national cultural expression to emerge. Tagore gathered what technical and industrial innovations he could from Europe and America to reform the practice of agriculture in rural Bengal, aiming at a unity of craft, farming, and village life that was, however, open to and benefitted from the wider world—a “cosmopolitan local” development not dependent on British imperial patronage.4 At the Bauhaus, meanwhile, the idea of India was everywhere, especially in the early years. Students practiced meditation and breathing exercises, vegetarianism, and studied their chakras, hoping to harmonize industrial technology with spiritual practice. In preparing for his inaugural speech of the school, Walter Gropius made a note to himself to cite the Gothic cathedral and “India!” in the same breath.5 Both European and Indian modernism looked to village, peasant life, and the spiritual life of the medieval past as a source of “authentic” cultural expression, freed from the vocabulary of realism and materialism imposed by the imperial rulers.6 Each of the two art and design schools was fascinated by, and aspired to, their imagined perception

Mackenzie

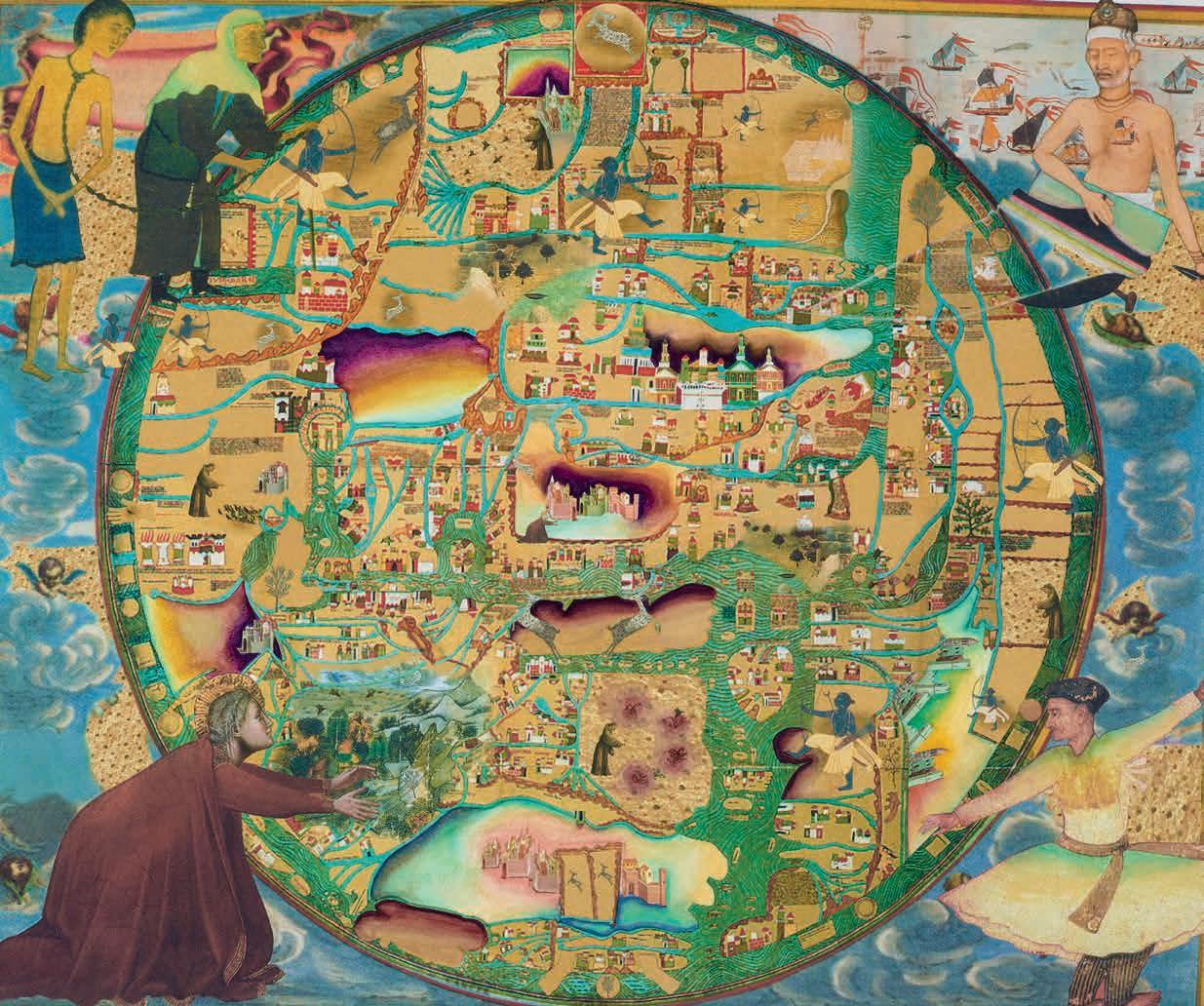

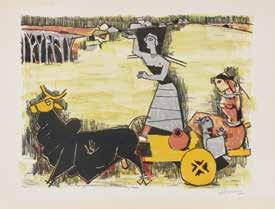

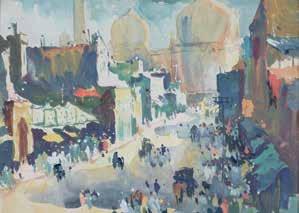

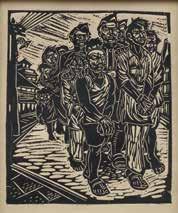

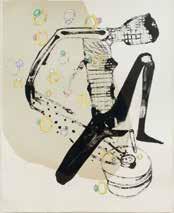

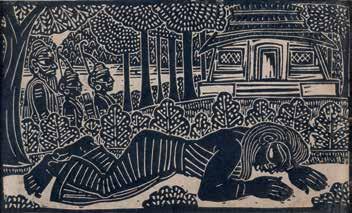

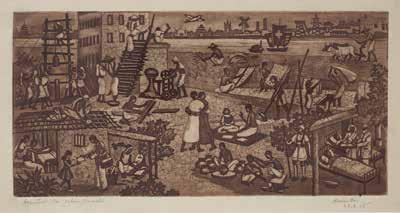

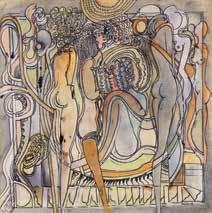

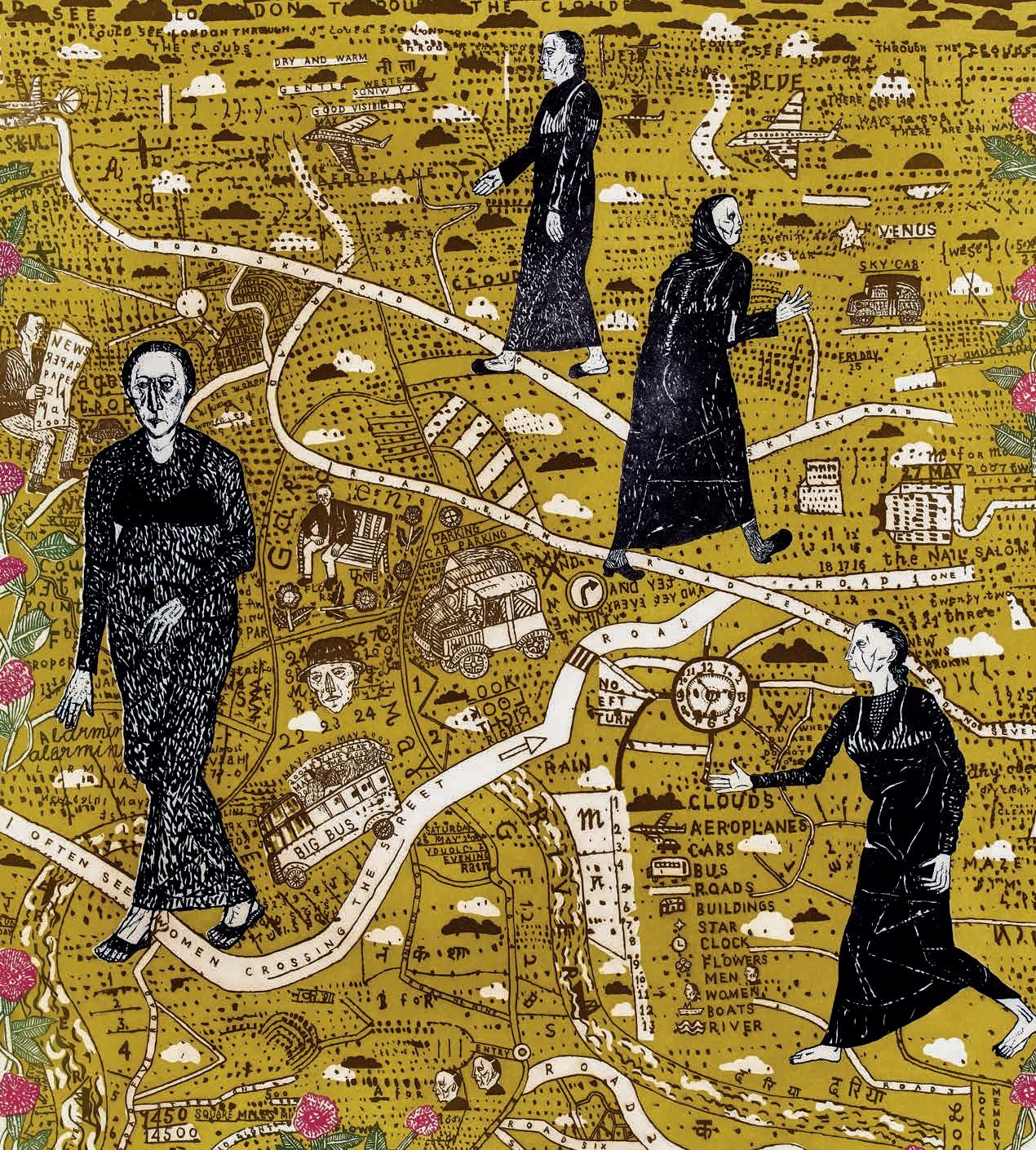

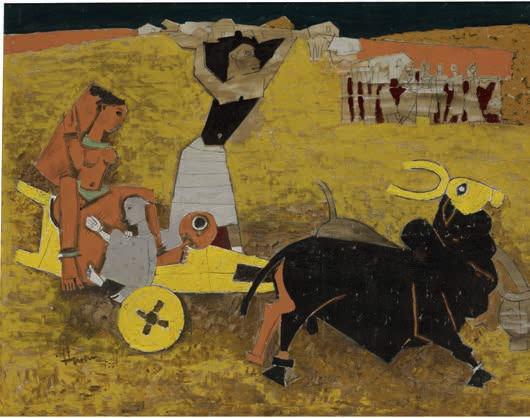

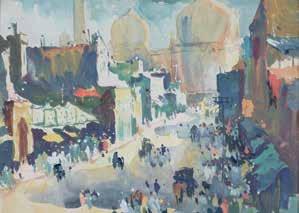

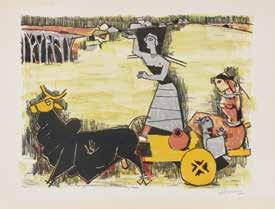

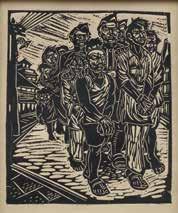

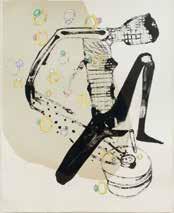

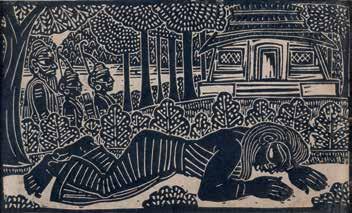

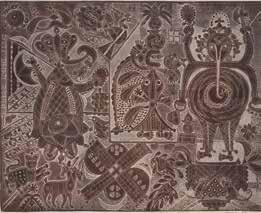

Maqbool Fida Husain (1915 2011)

Yatra, ca. 1950 Lithograph 17 3/4 × 22 1/8 in

One of India’s most internationally revered artists, Maqbool Fida Husain was frequently hailed as a global nomad. He was born in the remote pilgrimage town of Pandharpur in Maharashtra but was raised primarily in Indore (Madhya Pradesh), which at the time was a vibrant city under the suzerainty of the royal Holkars. Having displayed a distinct talent for calligraphy and poetry at an early age, while staying with an uncle in a madrasa in Baroda (now Vadodara), in Gujarat, he taught himself to paint and took great joy in cycling around, finding new ways to represent the lush, rural landscape. Driven by his desire to become an artist, Husain set off in 1937 for Bombay (now Mumbai) where he supported himself as a painter for hire, designing cinema billboards and commercial toys. After garnering acclaim at the annual exhibition of the Bombay Art Society, in 1947, he joined forces with F. N. Souza, S. H. Raza, K. H. Ara, H. A. Gade, and S. K. Bakre to establish the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG). By the 1950s, he was widely recognized as one of India’s leading artists. Although frequently heralded for his empathetic understanding and embrace of South Asia’s manifold religious traditions, his nude depictions of Hindu deities drew outrage in the early 2000s, and, in 2006, he was charged with promoting obscenities and “hurting sentiments of people.” Fearing prosecution, he lived in self-imposed exile and in 2010 officially became a citizen of Qatar.

Maqbool Fida Husain, Yatra, 1955, Oil on canvas, 33½ × 42 7/8 in

to 1955, reproduced in obverse, with which it shares all but a few select details. 5 The scene appears deceptively transparent: a village woman and her child are riding on a flatbed bullock cart, driven by a man standing in front and clad in a lungi, which is wrapped around his waist, forming a skirt around his legs. Just visible at the center of the vast and hilly landscape is a small town whose outskirts give way to a dense crop of forest. However, upon closer reflection the scene is anything but simple. Both the figures and the bullock cart draw upon Husain’s earlier life as a commercial artist by drawing upon the form of the stock toys massproduced, largely for urban audiences, by the company for which he worked in the 1940s. 6 At the same time, the title imbues the work with an aura of religiosity, noted more precisely by Ebrahim Alkazi in his 1978 monograph on Husain. He notes the strong resemblance of the driver, who stands at the center of the composition with one hand raised with the palm facing upward, to the Hindu god Hanuman, who, in his quest to procure healing herbs for Lakshmana, the brother of the god Rama, raised aloft an entire hilltop village. 7 This interweaving of rural and urban worlds—as well as present, historical, and mythic temporalities—is characteristic of Husain’s complex topographic engagements. [TS]

11

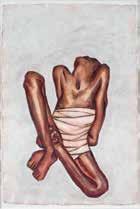

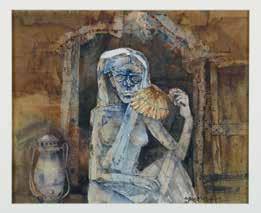

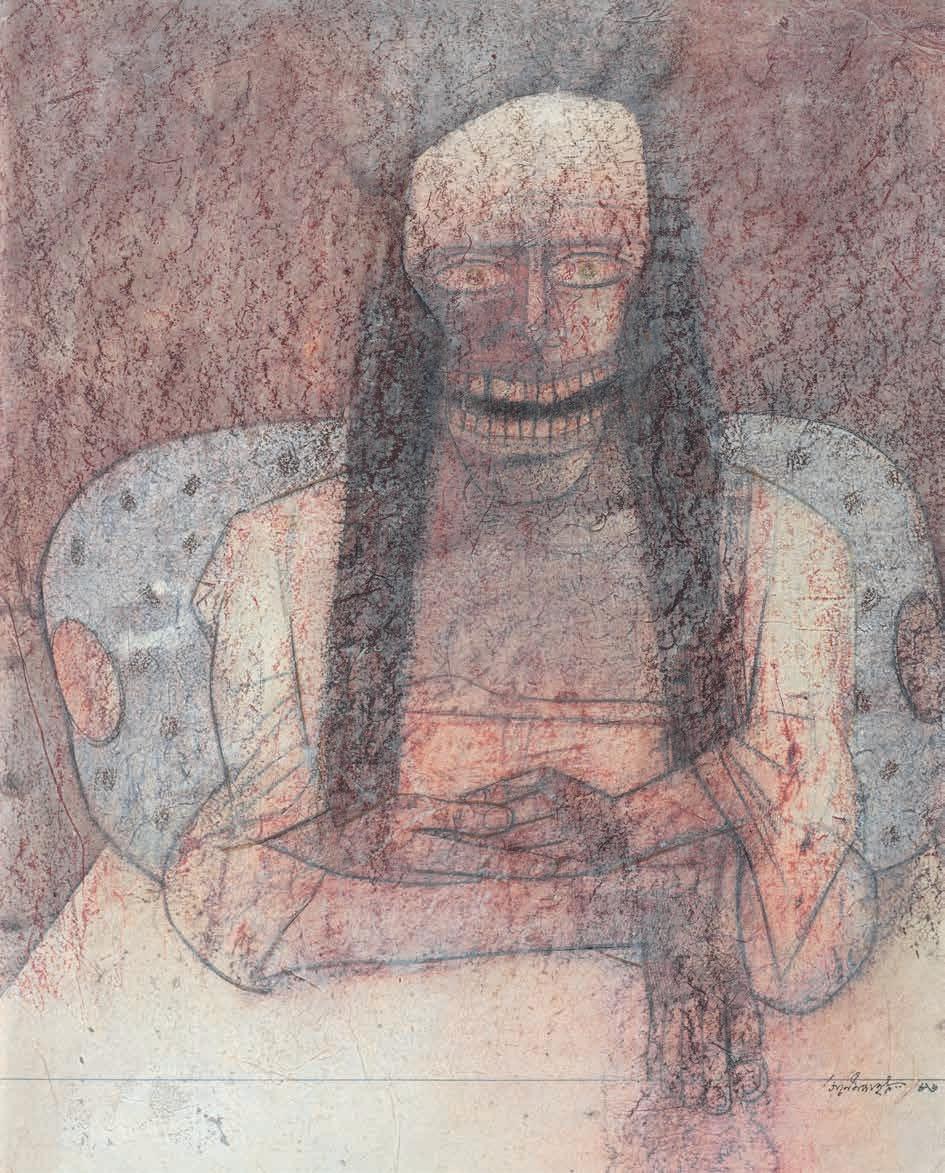

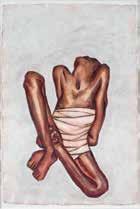

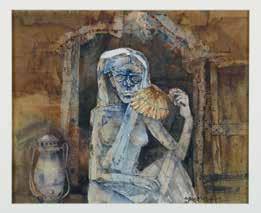

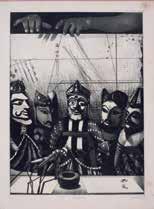

Untitled (The Dying Inayat Khan), 1983

Tempera over pen and ink on paper 17 × 13 3/4 in

A native of West Bengal, Ganesh Pyne began his career as an acolyte of the Bengal school of art, having trained at the Government College of Art and Craft in Calcutta (now Kolkata). He quickly developed a unique style of poetic surrealism that interwove characters inspired by Bengali folktales with a darkness rooted in the trauma of Partition that he experienced as a young child. Often small in scale, Pyne’s work is notably layered and labor-intensive, as can be seen in this work, depicting a well-known episode from the memoirs of the Mughal emperor Jahangir (the Jahangirnama), which has been widely available in translation since the 19th century. The episode in question describes the death of the emperor’s beloved servant Inayat Khan in extensive detail and as an extended process. The accompanying illustration, painted by the renowned artist Balchand, survives in the form of a preparatory drawing (Boston Museum of Fine Arts), as well as a completed folio (Bodleian Library, Oxford). It depicts Inayat Khan in profile, his body emaciated and slumped listlessly on his deathbed. The full text of the Jahangirnama, pertaining to this event, describes Inayat Khan having perished from the wasting away of his body due to chronic alcoholism and opium abuse, to the point at which he had become literally, in Jahangir’s words, “skin stretched over bone.”

Here, Pyne reframes “death” as an ongoing process, rather than as a final moment, and transforms the objectified courtier into a postmodern, post-colonial subject who remains fully aware of his viewer. Inayat Khan is positioned frontally, staring unflinchingly forward, his gaping mouth displaying an impossibly full set of teeth. As in the Mughal work, he rests against an embroidered cushion, but he sits

Dying Inayat Khan, Attributed to Balchand, Indian, active ca. 1600-1640, Ink and light wash on paper, 4 1/16 × 5 1/4 in

cross-legged, his knees bent and lower body folded almost completely into his torso. His face is skeletal, the flesh and skin already disintegrated. He has lost his hat, and his hair appears as unkempt columnar masses, extending down past his shoulders, as if they continued to grow even after his passing. The Inayat Khan that Pyne reimagines hovers in a liminal process between living and dying.

In its engagement with a Mughal past, Pyne’s work also translates its subject for a contemporary audience. Although Inayat Khan ostensibly died of dissipation, purportedly due to alcoholism and opium overuse, “his countenance,” as Ellen Smart has suggested, “is so close to that of a person dying from cancer or AIDS that it shocks the viewer at the close of the twentieth century.”20 At the same time, the clear emaciation of the body in contrast to the prominence of the skull calls to mind the tragic effects of famine in his native Bengal, as featured in the work of Somnath Hore, who was also based in Calcutta. An ardent member of the Communist Party, Hore became well known for his painstaking, and often graphic, documentation of the effects of war on marginalized communities. His experience during the Great Bengal Famine of 1943 spurred his life-long investment in portraying human suffering in emotionally arresting ways, as can be seen elsewhere in the exhibition through a series of etchings and prints dating similarly between 1975 and 1983. [TS]

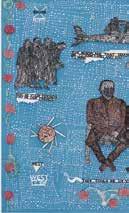

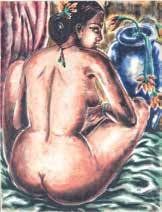

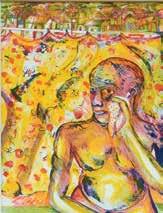

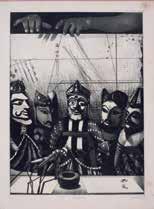

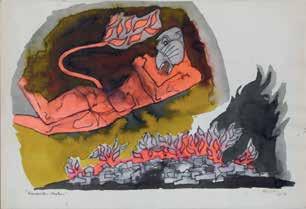

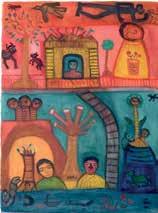

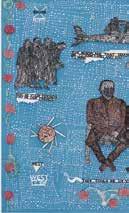

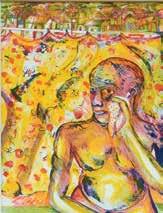

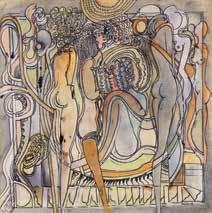

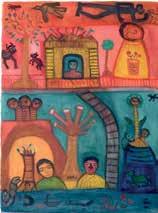

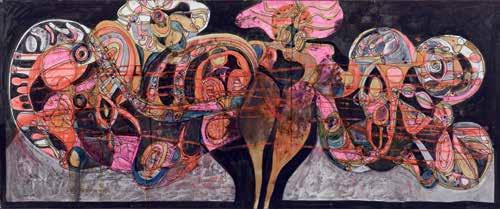

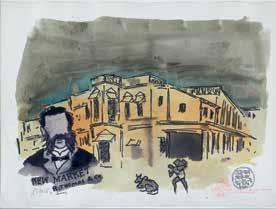

Best Bakery, 2004 Gouache on handmade paper 30 × 22 in

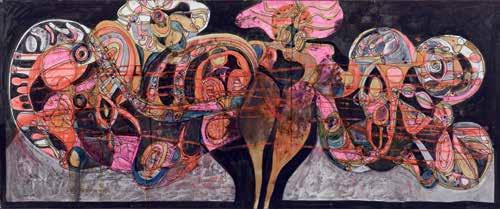

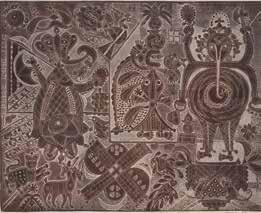

Born into a family of Tamil Brahmins in Kerala, K. G. Subramanyan began his education in economics before discovering his passion for art and enrolling at Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan, where his vision was shaped by pioneers such as Nandalal Bose and Ramkinkar Baij. In 1951, he joined the faculty of Fine Arts at M.S. University, Baroda (now Vadodara), where he served as an inspirational presence in shaping the distinctive and influential curriculum of that program, before returning to his alma mater in 1980, where he taught for nearly a decade before retiring. Often considered one of India’s most important modernist pioneers, Subramanyan is well known for his irreverence, and for his deep investment in Indian mythology and folk traditions. Subramanyan fused his extensive knowledge of craft traditions with international modernism into a masterful integration of the classical, popular, and modern visual languages. Many of his works were politically engaged, addressing specific moments of conflict through sculpture and painting. He approached tragedies with a sense of irony, emphasizing the corruptness of political, social, and religious affairs throughout India.

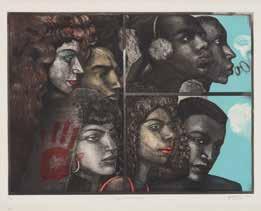

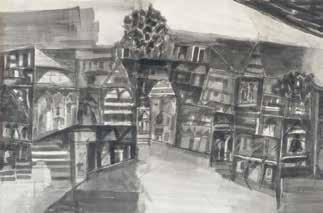

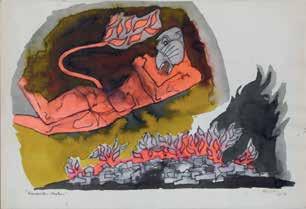

Best Bakery directly references a significant moment of Hindu-Muslim conflict, known as the Best Bakery incident, during the 2002 riots in Gujarat, India. On March 1 of that year, a Muslim-owned bakery was ransacked, attacked, and set ablaze by a mob, resulting in the deaths of 14 people: 11 Muslims and 3 Hindu employees. Subramanyan’s use of color and compositional techniques emphasize the violent nature of this event. His use of yellow, orange, and terracotta call to mind the burning fires, and his organization of space, following the style of Bengali pattachitras, forces the figures in this painting into occupying a small rectangular area, heightening the sense of entrapment. Subramanyan’s figures suggest a deep discomfort. Their bodies are contorted, warped, and twisted, and their faces seem to wail out in agony. A broken sign that reads “BAKERY” is shown to the right of the painting, underlining its connection to the highly publicized event. As the first case connected to the Godhra riots that was tried in court, it remains a symbol of the brutality and carnage during and following the riots. In rendering the scene in this manner, Subramanyan’s concern is not to be didactic, but rather to produce a distressingly accurate and sobering representation of the pain and anguish still evoked by this horrific event. [SG]

28a

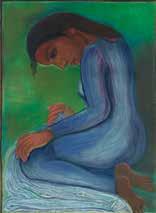

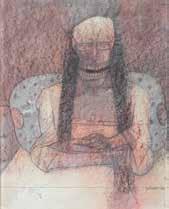

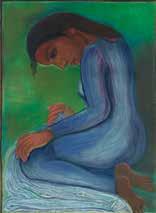

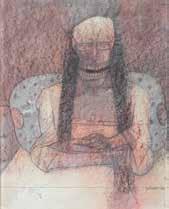

Mother (Mother Teresa), 1982 Crayon and pastel on paper 22 × 15 in

In addition to his scenes of rustic landscapes and his reflections on social policy and colonial histories, as seen earlier in catalog entries 3 and 23, Husain is well known for his engagements with India’s diverse religious traditions. In these works, M. F. Husain translates India’s composite culture and creates a new social space where diverse identities and ideas can be negotiated. The works seen here grapple with events and people that shaped history not only politically but also socially and spiritually.

Husain’s works portraying Mother Teresa reside on the hinge of myth, religion, and narrative. While there is no denying that Mother Teresa is a religious figure, Husain’s attempt at capturing visions of Mother Teresa was also driven by profoundly personal concerns. For Husain, Mother Teresa served as a symbolic surrogate for his own mother, Zaineb, who passed away when he was just two years old. While growing up, Husain was haunted by a story, told to him repeatedly, of his mother holding him tight one time when he was ill and pleading with God to take her instead of him.

Having lost his own mother at such a young age, Husain was left unable to recall her face. His decision to replace Mother Teresa’s face with a void in Mother thus speaks to this loss of memory. At the same time, it also enables her to transcend the specificity of a single woman to embody the idea of motherhood more broadly. This effort to universalize Mother Teresa is reinforced by the abstraction of the body and the dematerialization of location and context. In initially conceptualizing this series, Husain attempted realistic portraits. However, he quickly abandoned that endeavor in favor of subtle abstraction as a more potent way of revealing Mother Teresa’s spiritual dimension and maternal aura.

28b

Mother Teresa Series, ca. 1990s Screen print 26 ½ × 38 ½ in 28a | Mother (Mother Teresa)

Husain’s Mother Teresa series also engages a longer iconographic tradition associated with Christianity. It references and reimagines the Pietà, replacing the Madonna with three images of Mother Teresa: the modern Madonna, depicted as a faceless figure draped with her iconic lightblue-bordered white sari. While discussing his work, Husain stated: “I have tried to capture in my paintings what her presence meant to the destitute and the dying…That is why I try it again and again, after a gap of time, in a different medium.” 53 [SG]

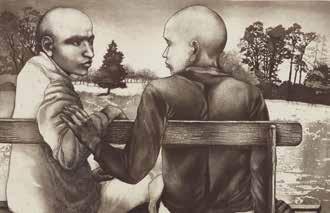

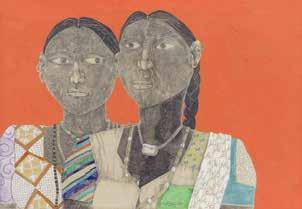

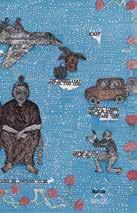

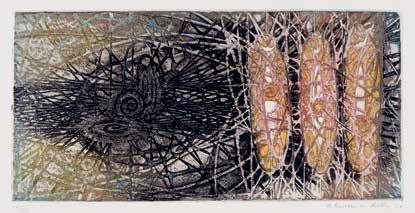

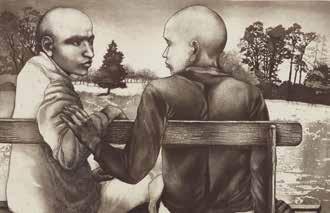

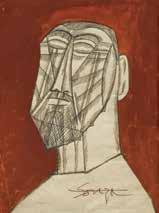

Jogen Chowdhury (b.1939)

33a

Untitled (Head), 1977 Pastel and ink on paper 15 × 14 7/8 in

33b

Man with Piece of Paper, 1986 Pastel and ink on paper 15 × 11 in

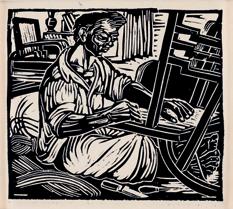

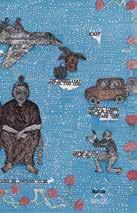

Born in a small village in present-day Bangladesh, Jogen Chowdhury’s family relocated to a refugee camp in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1947 following the Partition of Bengal. After graduating from the Government College of Art and Craft in 1960, he began work as a teacher in a secondary school in Howrah Zilla. A gifted writer and poet, as well as a visual artist, he spent his free time painting and organizing a literary and cultural group that published its first journal in 1961. In 1967, he went to Paris and studied at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and in Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17. When he returned to India, in 1968, he relocated to Madras (now Chennai) to work as a textile designer in the Handloom Board, where he remained until 1972, when he shifted to Delhi to take on the position of curator of the art collection at Rashtrapati Bhavan. In 1987, he returned permanently to West Bengal to take on the post of professor of painting at Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan.

Deliberately individual in his approach to art making, Chowdhury defied shifting artistic trends towards abstraction in the 1960s and 1970 to hone and perfect instead a unique vocabulary for figural representation. In a recent interview with Nawaid Anjum, he noted, “I believe that abstraction exists also in ‘real’ forms, in the human figures or any other object.” 58 A close observer of people, he was drawn particularly to the facial expressions and bodily gestures associated with elevated emotive states of joy and agony, which he captured through his mastery of texture and emotionally charged line, and also through the intentional distortion of heads and bodies. He has described these intentionally distorted figures as metaphors for the social and economic imbalances that have characterized Indian society since Independence. The gaze of Chowdhury’s

frequently introverted figures is often focused inward, at an angle, or away from the viewer. He is best known for his portrayals of single figures, closely cropped within the composition, and set against a dark and seemingly empty background that focuses the viewer’s attention on the main subject, while also eliding a specificity of place.

The two works in the Gaur Collection are outstanding examples of Chowdhury’s technical prowess and discerning eye. Man with Piece of Paper features exactly that: a middleaged man, likely an intellectual, with a receding hairline, stares off into the distance, while holding a sheet of paper closely against his chest in an elongated, almost Mannerist, hand. His head is tilted upward and his eyes are slightly crossed, as if his thoughts were turned inward in a state of deep contemplation, an impression that is reinforced also through his furrowed brow and the taut contours of his face. His state of dishevelment suggests that he remains oblivious to the world around him: half of his shirt buttons have come undone, and his collar crookedly frames his neck. The subject of his contemplation remains unknown, as the paper that he grasps is elusively blank.

The untitled work from 1977 portrays a man in profile, with an almost impossibly large and lumpy head resting upon strangely misshapen shoulders. The figure is stripped of any identifying markers save a pair of thin wire spectacles tucked behind a disproportionately tiny ear. Like the paper in the 1986 work, the spectacles suggest that the man being represented is an intellectual. Here, Chowdhury’s mastery of the line is evident in both the delicate definition of key facial features: the eyes, the nostrils, the ear, the chin and the upper lip, as well as in the use of dense cross-hatching to

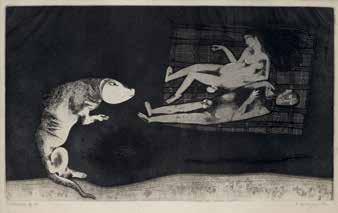

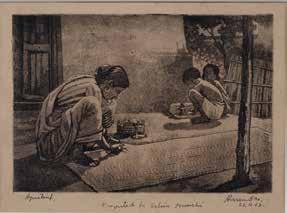

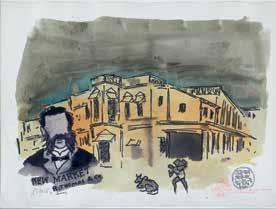

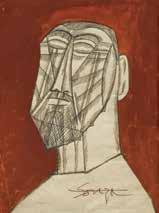

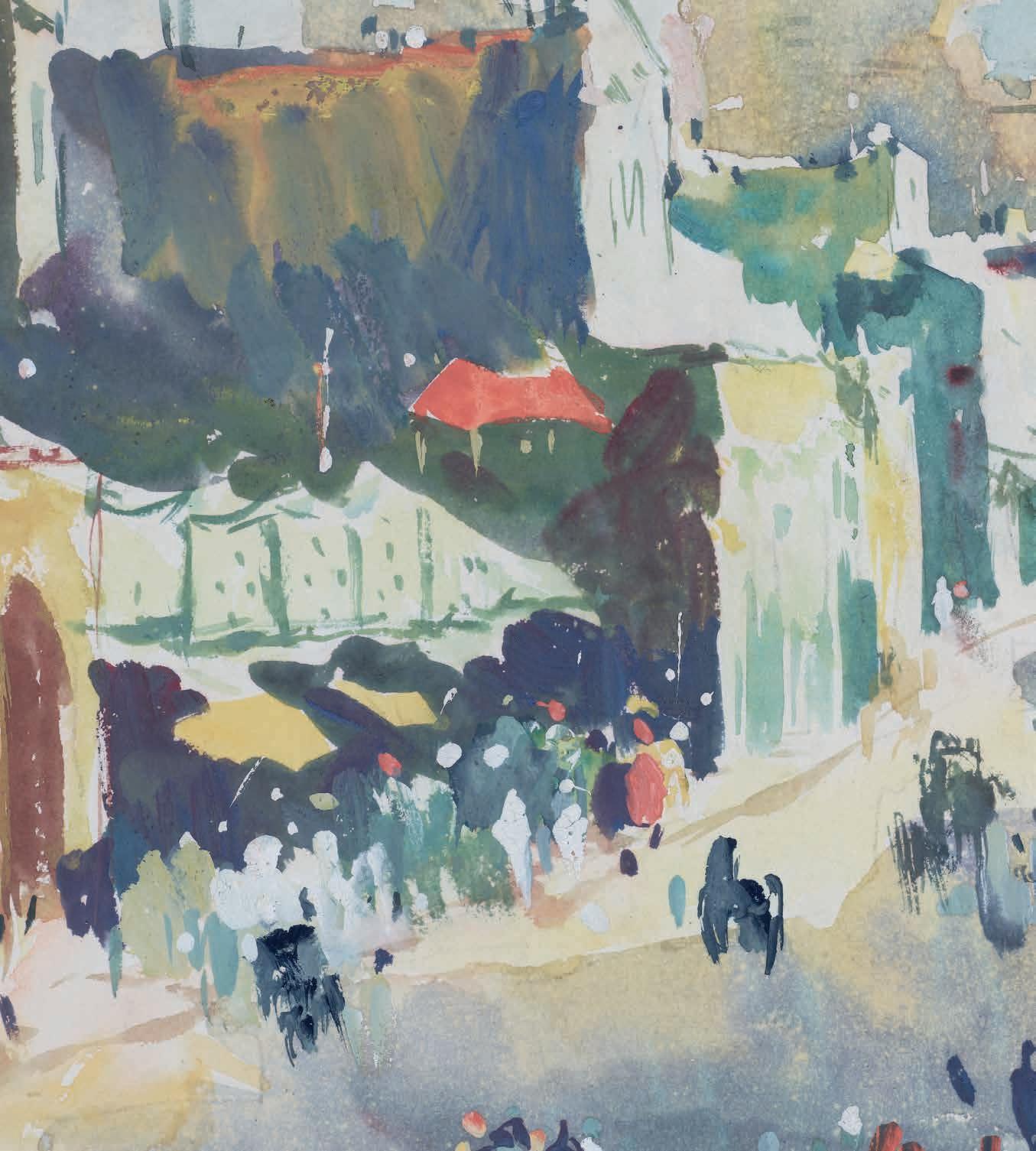

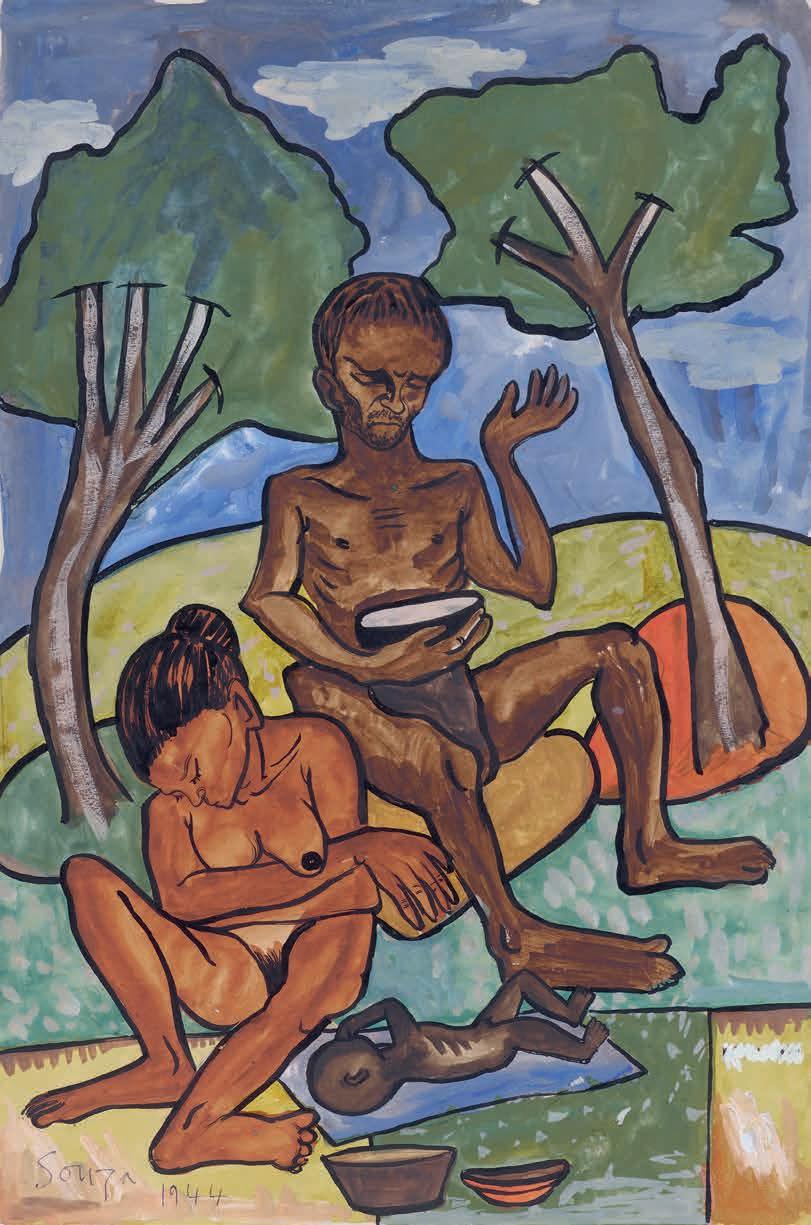

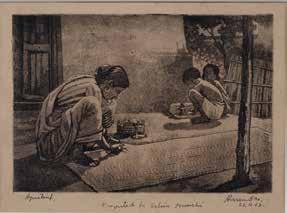

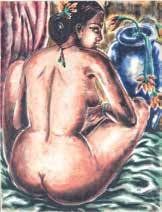

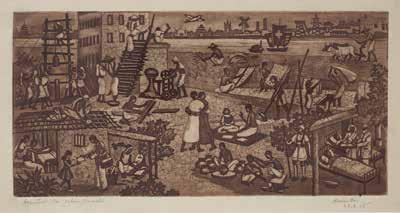

Bombay Beggars, 1944 Watercolor on paper 22 × 15 in

A rebel and an iconoclast, Francis Newton Souza had the kind of charisma that both attracted and repelled those around him, and a way with words as well as the paintbrush, both of which he wielded like a scimitar. Born in Portuguese Goa, where he spent his early years, he was raised in British India’s Bombay (now Mumbai). He was scarred by the loss of his father while an infant; by smallpox as a teenager; and by his rustication from Sir J. J. School of Art in his final year for having dared to join the Communist Party of India. He had famously also been thrown out of St Xavier’s School earlier on the charge of drawing obscene paintings in the lavatory—which he denied for their lack of quality.

His run-ins with the hidebound Bombay Art Society, with its strict criterion of rules and regulations, was the reason that he felt the need for a more dynamic and progressive art platform. The Progressive Artists’ Group was borne of that idea, co-founded by him along with five other artists (and, later, seven associates); Souza’s manifesto was an excoriating document that indicted what passed for “modern” at the time. An exhibition in which a nude self-portrait was exhibited won him opprobrium, and the continuing moral outrage was one of the reasons he chose to leave Bombay in 1949, settling in London where, after a period of initial struggle, his talent won him tremendous success. His departure, in 1967, for New York, for reasons

more personal than professional, failed to further advance his career.

Bombay Beggars was painted while Souza was still an art student and likely the result of his then Marxist ideology that drew his painterly attention to the condition of the poor in the city. One of the pioneers of subaltern modernism in India, Souza’s figurative muse in those formative years were the city’s poor and disenfranchised. During those formative years of his career, the marginalized often formed the subject of his paintings and consisted of family groups located within the milieu of their woebegone homes. His palette tended to the somber to reflect the hardworking bronzed skins and hardened features.

Bombay Beggars stands out because the figures are shown outdoors, a space they were more likely to be found than in any tenements. The group is shown unclothed—possibly the first among such paintings in which he dispensed with the need for apparel altogether. His later paintings would feature nudes as well as landscapes but in circumstances vastly different from this. Note must also be made of the signature. Souza was then known by his middle name Newton and signed his paintings as such; the Souza attestation here points to the signature being added to the painting at a later date. [KS]

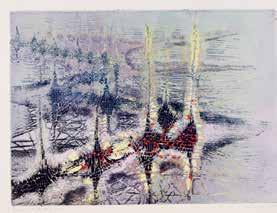

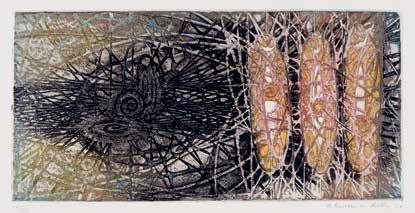

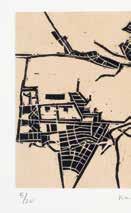

Ram Kumar (1924 2018)

42a

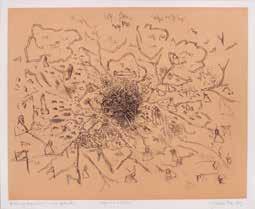

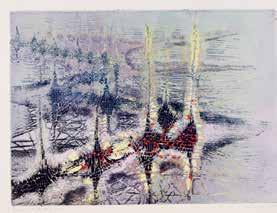

Untitled, 1982 Acrylic on paper 22 × 29 in

42b

Untitled, 1986 Acrylic on paper 11 × 16 in

Between 1949 and 1952 Ram Kumar studied in Paris with André Lhote, of the first generation of “Salon” Cubists, and with Fernand Léger. Like Léger, Ram Kumar joined the Communist Party of France, which supported the cause of the liberation of Europe’s colonies. In Paris, Ram Kumar, who also wrote novels and short stories, befriended the writer Louis Aragon, likewise a member of the Communist Party, and one of the founders of Surrealism, who had by the time Ram Kumar met him turned away from that movement and embraced Socialist Realism. Perhaps it was under the influence of Aragon that, in the early 1950s, Ram Kumar painted works like Unemployed Graduates (1953), which depicts four young South Asian men, in suits and ties, idle and disconsolate. Ram Kumar modeled his alienated figures starkly, in the fashion of French Socialist Realists, especially André Fougeron, another leftist. But, after 1953, the discipline exerted by the Party on painters to work in a narrow Socialist Realist style loosened, and Ram Kumar shifted permanently away from figure groups towards cityscapes, influenced by his visits to Greece, Venice, and, most importantly, the sacred city of Varanasi in 1960. Varanasi (or Benares), on the banks of the Ganges, is where Hindus prefer to be cremated after their death, their ashes set to drift off on the holy river’s currents, an act that promises salvation.

In 1970 Ram Kumar was awarded a John D. Rockefeller III scholarship to spend a year in New York City. It was during this sojourn that the artist began to explore fully abstract, gestural painting. The mark-making in the three works in this exhibition demonstrate an immediate, gestural

42c

Untitled, 1986 Acrylic on paper 11 × 16 in

expressiveness in the manner of the New York school. The two works from 1986, each painted in acrylic on sheets of 11x16 inch paper, although fully abstract, are nonetheless reminiscent of Ram Kumar’s paintings of river towns. Both have jutting tongues of watery indigo flowing laterally through them or pushing forward into the center, like the canals and embankments of Ram Kumar’s riverside cityscapes. They flow between and through the passages of black strokes, the only other pigment in these austere paintings. In the earlier, larger work, from 1982, the same two colors are more completely mixed together. All three works reveal something of the underlying structure of Ram Kumar’s cityscapes: a quilt of knife strokes in blocks and patches, mingling the grimy blacks and grays of urban housing blocks along narrow alleys and the murky blues of city waterways. Significantly though, they lack the outlines of doorways, balconies, windows, and gabled rooftops that are the sign of cityscapes in his earlier work. There is no rectilinearity, only fluidity. These abstract paintings are, simply, awash.

And yet the fluidly spontaneous structure of these works is not simply the product of happenstance. Ram Kumar routinely produced, as part of his practice, abstract line drawings in which improvised but carefully controlled parallel and cross-hatched lines define faceted, canted and overlapping planes, and the shallow spaces underlying them. These three paintings on paper relate to those line drawings but replace the intersecting blocks of crosshatching with individual strokes of the palette knife. Yet they also loosen the density of the drawings. Compared with the other abstract works in this exhibition, by Kapoor,

Reddy, and Kolte, these three pictures stand out for their spare simplicity, eschewing the complexities of process and careful compositional balance of those others. Interestingly, this unbinding of process contrasts quite a bit with Ram Kumar’s own cityscapes (such as Townscape, in the present exhibition), which insistently explored the tension between a picturesque, irregular built environment and the plumb and level lines of the picture’s edges. The poet Ranjit Hoskote has suggested that, late in his career, Ram Kumar, in keeping with the Hindu teaching of the individual’s changing priorities through life’s different stages, or ashramas—the

progression from householder to hermit to, finally, ascetic— “turned from the cacophony of civil life to meditate on the ceremonials of decay and dissolution … he stands upon that threshold where the anguish of the self is sublimated into the universal rhythm of creation and destruction.” In these three paintings the artist seems to turn his back on the windows, doors, and façades of the city and, from the vantage point of the steps leading down into the sacred, swirling waters of the Ganges, gaze into its endless flow as it swirls the ashes of this mortal existence away in its eddies, downstream towards eternity. [MM]

Figs 5, 7: Reproduced with permission of DACS; © Estate of F. N. Souza; All Rights Reserved, DACS, London/ ARS, NY 2022.

Fig. 6: Courtesy of the Google Art Project.

Figs 1, 2: Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Fig. 4: Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

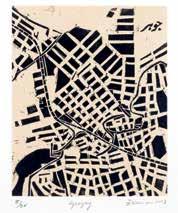

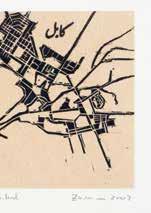

Figs 2, 3: Reproduced with permission of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York; © Zarina.

Fig. 4: Courtesy of Julio César Morales, the artist, and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

Fig. 5: Reproduced with permission of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York; © Zarina. Image courtesy of Lamay Photo.

Fig. 6: Courtesy of Nyugen Smith, the artist.

Fig. 7: Courtesy of Nyugen Smith, the artist, and the Solomon Collection.

Fig. 8: Courtesy of Alexander and Bonin, New York; © Emily Jacir.

Ancient Narratives of Devotion: Continuity, Transformation, Rejection

Figs 1, 2: Reproduced with permission; © the M. F. Husain Estate.

Fig. 3: Courtesy of the National Museum, New Delhi.

Fig. 5: Courtesy of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi.

Fig. 6: Courtesy of DAG, New Delhi.

Fig. 7: Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Fig. 8: Reproduced with permission from the Bhupen Khakhar estate; courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Fig. 9: Reproduced with permission from the Bhupen Khakhar estate; courtesy of Artforum.

Fig. 10: Courtesy of Atul Dodiya, the artist.

Fig. 11: Courtesy of STPI - Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

Fig. 12: Reproduced with permission of the Cy Twombly Foundation; © Cy Twombly Foundation; courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Cacophonies and Silence: Hearing Abstraction

Fig. 1: Reproduced with permission of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York; © Zarina.

Fig. 5: Courtesy of Navjot Altaf, the artist.

Fig. 6: Reprinted from Hanning dadi (Frozen Land) (Changsha: Hu’nan Meishu, 2000).

Fig. 8: Courtesy of the Reading Public Museum, Reading, Pennsylvania.

Figs 9, 10, 11: Reproduced with permission of DACS; © Anish Kapoor. All Rights Reserved, DACS, London/ARS, NY 2022.

Figs 10, 11: Courtesy of Ken Lee.

Entries 3, 23, 28–29: Reproduced with permission; © the M. F. Husain Estate; Image on p. 74 courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Entry 5: Image on p. 78 courtesy of the Wikimedia Foundation.

Entries 8–9: Reproduced with permission of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York; © Zarina.

Entry 11: Image on p. 100 courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Entry 17: Image on p. 122 courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Image on p. 124 courtesy of Tamara Sears.

Entry 27: Image 27a courtesy of DAG, New Delhi.

Entry 31: Image on p. 171 courtesy of the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi.

Entries 37–39: Reproduced with permission of DACS; © Estate of F. N. Souza; All Rights Reserved, DACS, London / ARS, NY 2022.

Entry 40: Image on p. 200 courtesy of Tamara Sears.

Entry 43: Reproduced with permission of DACS; © Anish Kapoor. All Rights Reserved, DACS, London/ ARS, NY 2022.

Entry 45: Image 45e courtesy of DAG, New Delhi.

Dr. Tamara Sears is Associate Professor of Art History at Rutgers University in New Brunswick.

Dr. Michael Mackenzie is Professor of Art History at Grinnell College.

Dr. Paula Sengupta is Professor at the Department of Graphics-Printmaking at the Faculty of Visual Arts, Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata, and an artist, academic, curator, and art writer.

Emma Oslé is an advanced Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Art History at Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey.

Dr. Darielle Mason is the Stella Kramrisch Curator and Head of the Department of South Asian Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and adjunct professor of the History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Rebecca M. Brown, Professor and Chair of the Department of the History of Art at Johns Hopkins University, is a scholar of colonial and post-1947 South Asian visual culture and politics.

Jeffrey Wechsler has been Senior Curator at the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, retiring in 2013 after 36 years of service, and has authored numerous publications on art. He has acted as curator and consultant to the Gaur Collection since 2002.

Kishore Singh is a former journalist and editor. In 2010 he joined DAG to head its exhibitions and publications program and continues to be associated with its content department.

Swathi Gorle is an advanced Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Art History at Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey.