Preface

Tombs have been in existence around the world since time immemorial: prehistoric burial mounds, usually built around a hut containing personal belongings of the deceased, tombs of pharaohs of Egypt, the pyramids, and more recently, Islamic tombs of India with which this volume is concerned. In Christianity (at least initially till Renaissance when the idea of tomb as a home died out in the Western world) and Islam, a tomb is a symbol of heavenly abode. It is perhaps for this reason that the pre-Mughal and Mughal rulers introduced paradisiacal imagery around their tombs by building gardens and flowing streams and fountains, which in the Koran are associated with paradise.

Many Mughal funerary tombs have disappeared, others are in advanced stage of decay or ruin, and still others are in a remarkable state of preservation. There are both royal and non-royal tombs of ordinary nobles and royal servants like barbers. In this volume we are concerned only with royal tombs in order to keep our study manageable as well as to present grand and palatial buildings. We have left out various non-royal tombs even though they were

located in the royal tomb complexes (as in the cases of Lodi tombs in the Lodi Gardens and Humayun’s tomb complex in Nizamuddin, both in Delhi).

Royal (Islamic) tombs of India are associated with three main themes:

1. Religion: Tombs provide a heavenly abode to the deceased. They are often (though not always) decorated with Koranic verses to add religious piety.

2. Political power: The Islamic rulers of India were in a hostile land of the so-called infidels following a different religion called Hinduism. Therefore, many royal tombs and mosques were built as a symbol of power and might, as some names suggest, e.g. Quwwat-ul-Islam (Might of Islam) mosque in the Qutb Minar complex. An expression of power through buildings and architecture was intended to inspire awe and subdue the enemy and the subjects. On the other hand, Muslim rulers of Central Asia and Persia did not face any hostile non-Muslim subjects: their subjects were also Muslim.

3. Love and passion: Some (e.g. the Taj Mahal) reflected the eternal love of an emperor for

6

his spouse. In others, passion for arts and architecture of such emperors as Akbar (and earlier Sultans of the Tughluq dynasty) led to the building of impressive palaces, tombs and mosques which combined the dual purpose of promoting art and propagating Islam.

This volume is concerned with Islamic architecture of the pre-Mughal and Mughal periods. The pre-Mughal period relates to the Slave and Tughluq dynasties: Slave kings were the first permanent Muslim rulers in the north of India. No doubt there were earlier invaders but they did not settle in India as their main interest was to loot and plunder (e.g. Mahmud Ghazni’s raids into the north of India between 1001 and 1027). The tombs of the Lodi sultans, the Qutb Shahi kings and the Mughal emperors are among the most magnificent examples of Islamic architecture and grandeur. No doubt there are other Islamic tombs in India but they do not match the beauty and imposing character of royal tombs.

This book is a pictorial, historical and architectural story of 25 royal tombs dating from the earliest Slave dynasty in the 13th century to the end of Aurangzeb’s reign at the beginning of the 18th century. The tombs are presented in a broader historical and architectural context of the reign of different emperors or queens for which they were built. Each chapter begins with a brief introduction of the kingdom or emperor whose tomb or palace is presented. The final chapter consists of photographs of different aspects (interior, exterior, garden layout) of the tomb or monument.

An introductory chapter is added on the history of royal tombs in different regions, countries and

cultures starting with the tombs of Egyptian Pharaoh kings dating back to nearly 3000 BC. A second chapter is devoted to the evolution from preMughal to Mughal architecture. Persian and Hindu influences on Indian Islamic architecture, a central theme of the volume, is discussed here in more detail. Chapters 3 to 6 discuss individual royal tombs of pre-Mughal and Mughal dynasties.

The study is focused mainly on tombs in the preMughal period, it also includes those of Babur, Humayun and Jahangir and discusses differences in the techniques of decoration in Hindu, pre-Mughal and Mughal architecture. Chapter 2 presents drawings of different types of arches, domes, kiosks, pavilions and decorative motifs contained in the tombs and historical monuments. The book also compares and contrasts different techniques of tomb architecture, their size, location etc. to determine unity or differences in different styles. In this context, the influence of Hindu architecture and decorative motifs on Islamic ones, is examined.

My interest in Indian history (especially that relating to Ashoka and Gupta periods and Islamic rule), photography and travelling explain the genesis of this volume. A few years ago, in December 2002, I travelled to pre-Mughal and Mughal locations in India to photograph and learn more about history associated with them. My journey took me to several places including the ancient cities of Delhi, Agra and Fatehpur Sikri in the north, Hyderabad and Golconda in the Deccan, and Aurangabad and Khauldabad in the south-west of India. In Delhi, I visited Lodi tombs in the Lodi Gardens, and Humayun’s tomb in Nizammuddin. In Agra I visited Fatehpur Sikri, Taj Mahal, the Fort and Akbar’s

7

tomb at Sikandra. In February 2005 I returned to India again, this time to do some research in connection with this volume and visit additional places and sites such as the tomb of Iltutmish in the Qutb Minar complex and the tomb of Ghiyas-udDin Tughluq in Tughluqabad.

In preparing this volume I have benefited from a number of friends and relatives. I owe a debt of gratitude to Naveed Riaz for providing, at short notice, valuable material and documents relating to Jahangir’s and Nur Jahan’s tombs at Shahdara near Lahore; Professor Satish Grover for lending me his valuable books on Islamic architecture of India and drawing my attention to the important Persian and Hindu influences on this architecture; Nirad Grover, for showing me around Delhi and educating me about its rich and varied ancient history. Nirad’s keen eye for composition, photography and sense of light, enabled me to take many good photographs of royal tombs in the Delhi area.

Hemani Bedi of Eindhoven, the Netherlands, a graduate in architecture from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, and an MS student in Architecture, Building and Planning at the Technical University of Eindhoven, contributed significantly to the preparation of the first two chapters besides

drawing illustrations of arches and domes for chapter 2 and a sketch of Babur’s chauburj tomb (Agra) for chapter 6. She read the entire manuscript and gave very useful comments. Wilayat Bhatty of Lahore, Pakistan (former Assistant Director of the Lahore Museum, and a former member of the Department of Archaeology of Peshawar University) kindly read sections on Jahangir’s tomb and Nur Jahan’s tomb in chapter 6. His valuable comments, suggestions and insights are much appreciated. Arunjot Bhalla, Associate Director, RSP Architects, Bangalore (India), and an MA in Architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), provided useful relevant material, moral support and encouragement throughout the preparation of the volume.

The staff of the following libraries in India, Switzerland and the United Kingdom respectively, were most helpful in tracing old and rare books pertaining to the history and architecture of the pre-Mughal and Mughal royal tombs included in this volume: Archaeological Survey of India and the National Archives of India (New Delhi); History and History of Art Sections of the Library of the University of Geneva, and the Library of Art and Archaeology of the City of Geneva; India Office Section of the British Library (London) and the Cambridge University Library, UK.

~ A.S. Bhalla June 2006

Commugny, Switzerland

8

History ofRoyal Tombs

The word “tomb” derives from the Latin word “tumba”. According to the New Encyclopaedia Britannica (1985, 11:835), in the strict sense, a tomb is a home or house for the dead. The term “is applied loosely to all kinds of graves, funerary monuments, and memorials”. In primitive cultures, in the ancient times, the dead were buried in private houses. Thus, “prehistoric tomb barrows were usually built around an actual round hut,” in which a body was placed along with such other objects as tools and personal belongings for use in the next life as there was a belief in life after death. Historical records show that in the earliest times kings and queens were even provided with servants who were actually killed and buried along with them, to serve their master in the next life.1 Ancient Egyptians believed so strongly in the afterlife that the earthly dwelling was regarded as the temporary house, and the tomb as the permanent abode. This explains why they built such lasting, enduring tombs for their royalty.

The discovery in 1999 in Syria, by a German archaeological team, of the partial remains of two members of Qatna’s royal family and offerings, in an open sarcophagus provides an indication of a Near Eastern cult of the dead. There is evidence (in the form of pottery jugs, jars and bowls and some food and bones of animals), of a feast inside the royal tomb where King Idanda of Qatna invoked the spirits of his ancestors to gain blessings to defend his kingdom against invaders during the late third millennium BCE (Lange 2005). Different religions and cultures have different practices concerning burials. Some civilizations included the building of memorials to the dead in or next to such holy places as mosques or churches. Indeed, in the Christian

faith, many kings were buried in churches and cathedrals. Sometimes, even a church functioned as a tomb (e.g. Hagia Sophia in Istanbul served as the tomb of Justinian). The Buddhist stupas contained the remains and ashes of the dead.

Originally, these stupas were simple structures of mud, compacted earth and stone, which contained relics of the Buddha and his followers. They are a kind of a tomb defined as, “sepulchral sanctuary enshrining the charred bones or ashes from the funeral pyre of a deceased hero” (Barua 1926:17).

While a Christian or a Muslim tomb indicates a burial, a stupa pertains to cremation and ashes. Therefore, a stupa may contain a chamber (as in Egyptian pyramids) in which bodily remains may be deposited.2 The graves were either rectangular or in the form of domes, structures similar to the ones in Islamic architecture of royal tombs discussed in this volume. The later royal tombs, for example, of the sultans and kings mentioned in this volume, have retained this basic structural form of main chambers and smaller chambers. For example, in the tombs of Humayun and Akbar, graves are located in the central rooms, which are surrounded by smaller rooms.

An internet list of tombs3 contains references to 131 funerary tombs located in such countries as China, Egypt, India, Iran, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Iraq, Morocco, Syria, Turkey, Uzbekistan, and Yemen, dating from the 10th to the 20th century. However, tombs existed even before the Christian era. For example, the Buddhist stupas of Sanchi and elsewhere in India date back to 200 BCE.

Table 1.1 presents a list of selected royal tombs from the ancient Pharaohs (more than 3000 BCE) to the

12

more recent Islamic ones included in this volume, ranging from the 13th-century tomb of Iltutmish to the 18th-century tomb of Aurangzeb.4 The table is not exhaustive, but illustrative, and intended to show that royal tombs of immense size and grandeur were built in ancient Egypt, Hellenic Greece, ancient Rome, Renaissance Europe, China and the rest of Asia.

conical ones.6 A typical pyramid consists of a burial chamber in the centre to house the sarcophagus with the body of the king or queen, and other inner rooms to contain offerings in the form of jewellery and ornaments, pottery, textiles and other objects.

Egyptian Pyramids

As table 1.1 shows, a majority of the ancient Egyptian tombs and pyramids relate to the Pharaonic times spanning nearly three millennia. This covers three major periods: the Old Kingdom (lasting 500 years, from 2700 to 2200 BCE), the Middle Kingdom (lasting 200 years, from 2000 to 1800 BCE) and the New Kingdom (lasting 500 years, from 1600 to 1100 BCE).5 Early pyramids (like the mastabas) had no inscriptions or decorations. They were built above the ground. However, the later tombs built during the New Kingdom were constructed underground, in order to conceal them from robbers and thus prevent the loss of rich treasures buried along with the dead bodies. These later tombs were decorated with scenes of the kings’ and queens’ journeys from life to afterlife and showed the kings and queens in the midst of deities and offerings.

The step pyramid complex of Zoser (or Djoser) at Saqqara, in Egypt is known to be the oldest structure of its kind, dating back to 2500 BCE. In Egypt, royal tombs were originally built in the form of mastabas— consisting of an underground burial chamber with rooms above it to store offerings. Mastabas led to the building of step pyramids, which evolved into

The building of the pyramids commenced during the 3rd dynasty (2686 2575 BCE) as well as the 4th (2600 2480 BCE) when this architecture reached its apex, with smooth-sided pyramids taking the place of the earlier structures. The art of pyramid building is associated with the 3rd to 6th dynasties of Pharaoh kings of the Old Kingdom.7 The kings of the 5th dynasty (2480 2330 BCE) built smaller pyramids than those built under the 4th dynasty at Saqqara and Abu Sir. These pyramids are less well-preserved.

There are 65 known tombs in the Valley of Kings, which is situated between Karnak and Luxor, along the river Nile. Unlike the pyramids, these tombs were built by cutting deep into rock and with tunnels leading to the tombs. However, of the 23 tombs discovered in the Valley the treasure was found intact only in one (the tomb of Tutankhamun). Other treasures must have been looted.

Historical evidence suggests that the pyramids were built as tombs for kings and queens. Several reasons are given for this view: the pyramid was the beginning of a long evolution of design for a royal tomb; the pyramid texts found (appearing for the first time in the pyramid of Onas), indicate the funerary function of these structures; bones and limbs were discovered in some pyramids. Smith (1998) discusses the pyramid texts, which were intended, inter alia, to aid the king in the transition between his earthly functions and the position he was to assume amongst

13

A “Way of Souls” (shendao) generally led to the complex of Chinese royal tombs. This way was lined on either side by the impressive stone or terracotta statues of human figures, presumably of guardians who were there to protect emperors from demons and to prevent their souls from leaving. The shendao leading to the tomb of emperor Gaozong is still well-preserved. Although many statues are damaged and disfigured, they are still in place. “They stand in pairs comprising columns, winged horses, slabs with reliefs showing birds, saddled horses with their grooms as well as 20 statues of officials, stelae crowned with dragons, and two brick pillars” (Fahr-Becker 1998:135). While the 13 tombs of the Ming dynasty (1368 1644) near Beijing retain the shendao leading to the tomb complex, they do not follow the straight line of the Tang dynasty. Instead, the Ming shendao is full of bends and curves.

The subsequent dynasties following Tang, namely, the five dynasties of the Wudai period (906 960) and Song dynasty (960 1126/1279) retained the cultural and architectural heritage of the Tang in the design of royal tombs and their furnishings. A peculiar feature of the tombs of these dynasties is the discovery of human bodies with the heads of cows and monkeys and bodies of doves, fish and snakes with human heads. These figures seem to belong to Chinese mythology.

The later Ming tombs near Beijing have the Way of Souls leading to the tomb complexes, but as we noted earlier, the path is curved. At the beginning of the path is a gate of honour (paifang), followed by two interconnected buildings: the Great Red Gate and the Hall of Stelae (the alleyway of stone figures).

Many Chinese royal tombs are located near Nanjing, capital of the southern dynasties (the first Ming ruler is buried in Nanjing), and near Changaan (modern X’ian). For example, the Tang dynasty tombs like those of Tang Qianling, Tang Gaozong (618 626) and empress Wu Zetian (690 704) are located near X’ian. The tombs of Ming rulers (except the one noted above) are located in Beijing, and those of Qing emperors are found in Zunhua City of the Hebei province. The tomb of Qin Shihuangdi, the first Chinese emperor, is a huge burial mound near Xianyang in the Shaanxi province. He built a large terracotta army consisting of thousands of officers and soldiers to protect him in his afterlife. The army is buried near the emperor’s mound.

Islamic Royal Tombs

Islam dates back to the end of the 6th century when Prophet Mohammed, the founder of Islam, was still young. The basic framework of this religion was established at the time of his death, in 632. An explosive expansion of Islam followed – from Mesopotamia to Egypt and beyond, to the Mediterranean.10 In fact, in modern times, the following countries have been influenced by Islam at some point in history: Asian and European Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece, Sicily, Cyprus, North Africa, Southern and Central Spain, Syria, Palestine, the Gulf States, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, South and Central Russia, India, East Africa and Indonesia.

Islam promoted a way of life and an attitude amongst its followers that had a significant influence on architecture, resulting in what is referred to as “Islamic architecture”. In this architecture, there is

18

no major difference in building techniques between religious and non-religious structures. Decorations tend towards the abstract, using geometric, calligraphic and plant motifs, with a preference for a uniform field rather than a focal element. Decorated surfaces are controlled by framing, and an inherent conservatism discourages innovations and favours established forms (Fletcher 1996:569).

Islam forbade any formal commemoration of the dead through monuments.11 Shariat, the orthodox Islamic law, prohibits even masonry graves. Therefore, it is paradoxical that Central Asia, India and Pakistan are replete with tombs and royal mausoleums. Tombs were sometimes given a semblance of a mosque. As the kings were considered divine, they could afford to ignore religious injunctions (Nath 2003). The growing strength of Islam and the Muslim conquerors’ ambitions to leave their legacy behind, led to the celebration of victories in the form of royal mausoleums for the dead kings. Non-royal tombs grew with the believers’ desire to honour saints and Sufis.

The long history of tombs originates with the first known Islamic mausoleum of Qubbat-i-Sulaibiya (863) in Samarra, Iraq. It is a domed structure, square in plan, surrounded by an octagonal ambulatory. This building marks the beginnings of Islamic domed mausoleums in Egypt, Persia, southern Central Asia and India. Before this period, emphasis was on the construction of religious buildings as mosques, ribats and madrasas. Such was the importance of a mosque that its form was echoed in other structures as well. Some earlier tombs were, in fact, attached to another building, for example, the mosque and tomb of Imam Dur, Samarra (1085). Attached to the madrasa,

Al-Nuriya al-Kubra in Damascus, is the tomb of its patron, Nur al-din.

It was only in Bukhara (Uzbekistan) that powerful forms of royal tombs attained greater significance. Bukhara flourished under the Samanid dynasty in the 9th and 10th centuries. The tomb of Ismael the Samanid,12 Bukhara (905), is a fairly small mausoleum built in elaborately decorated brickwork (fig. 1.2). This building is an almost perfect cube, with a hemispherical dome superimposed on it, a style of architecture which has largely disappeared due to Mongol attacks and the impermanence of mud brick. The Samanid tomb was built when firebrick was just coming into use. It is the precursor of monumental tomb building in south-west Asia.

A series of powerful forms of tomb towers were built in the early 11th century in northern Persia, the most impressive being Gunbad-i-Qabus, Gurgan (1006 7). It is a cone-topped tapering cylinder constructed of brick, with ribs in a stellar form. These powerful forms are to be found in Seljuk architecture. The Seljuks made incursions into India around this time, when Mahmood’s General, Qutb-ud-din Aibak, built Qutub Minar in Delhi (see chapter 2).

There was a shift in focus in the development of Islamic architecture, from Syria (Damascus, Aleppo) in the 8th century and Mesopotamia, in the 9th–12th centuries, to Asia Minor and Persia during the Seljuk rule, and then to south-central Asia during the Timurid rule, in the 14th and 15th centuries. Southcentral Asia was always prone to barbarian attacks, as the invaders tried to settle in the oasis towns. By the 14th century, Timur (Tamerlane) had captured central Asia right up to the Nile in Egypt and the

19

20 FIG. 1.2

Bosphorus in Turkey. He proclaimed Islam across his territories and made Samarkand (Uzbekistan) his capital. Samarkand became the centre of architectural development, power and influence. Here was perfected the paradise garden concept (Hasht Behisht), which was to become an important feature of Mughal architecture (see chapter 6).

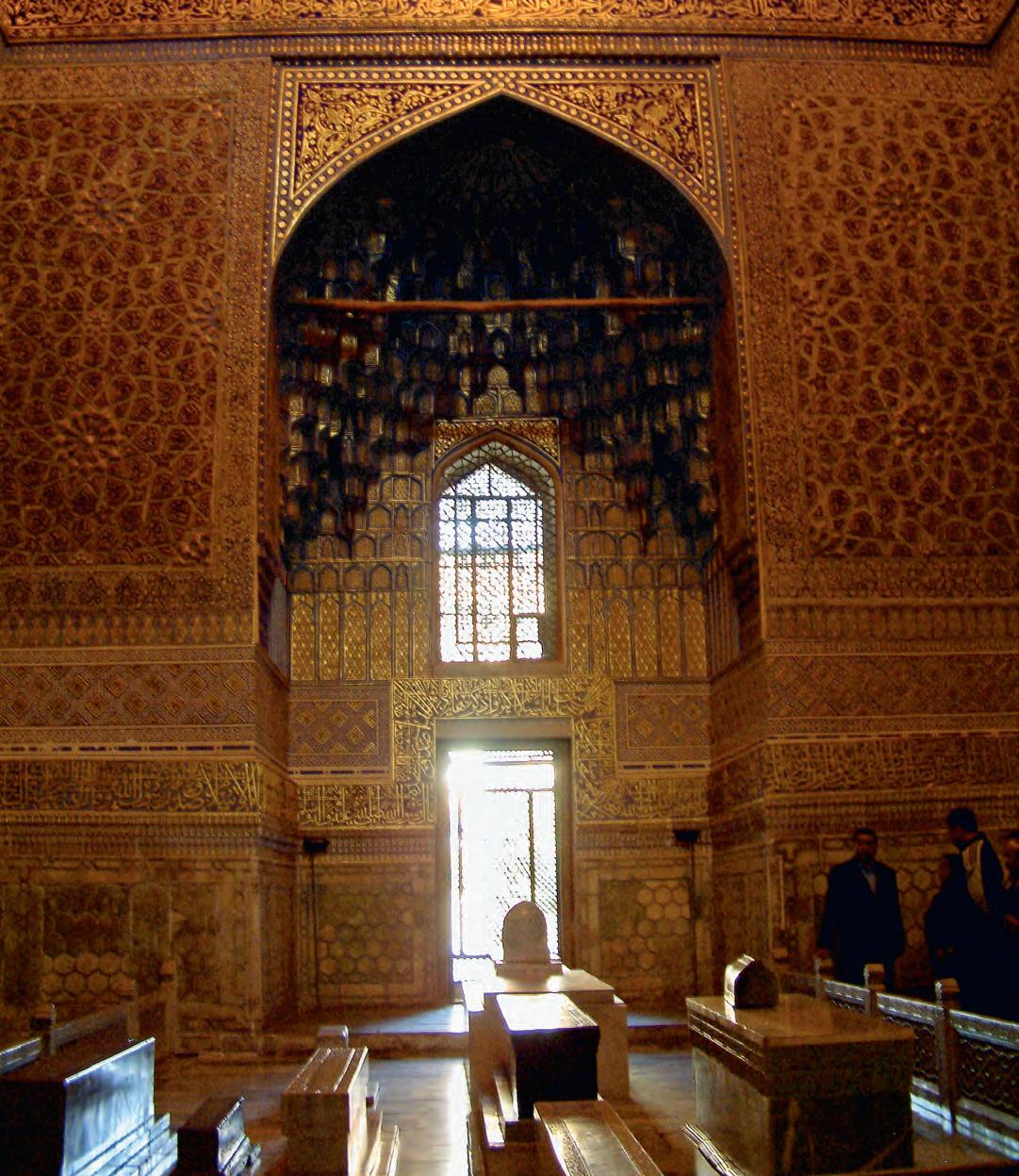

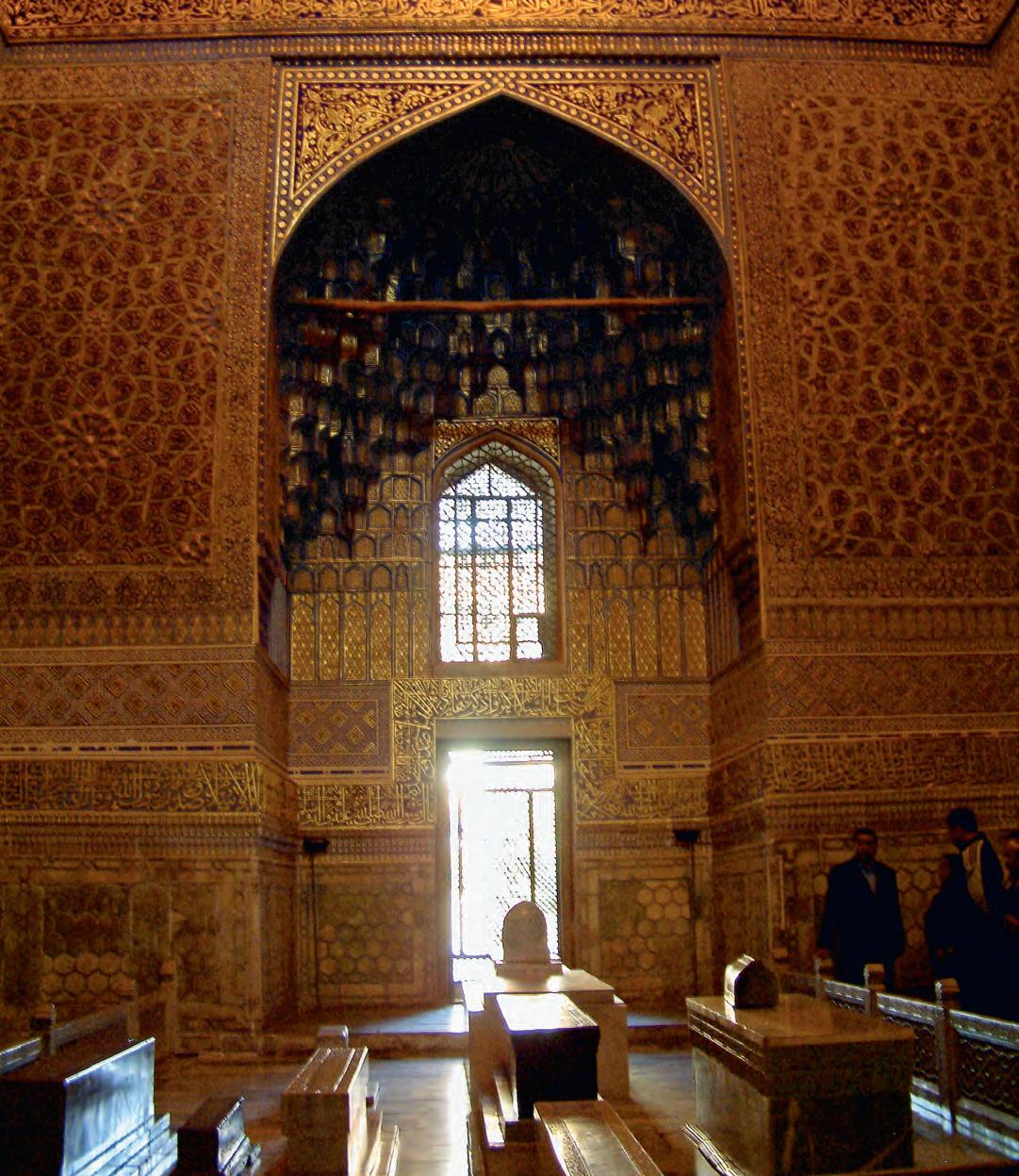

Timur is buried in Gur-i-Amir (The Great Prince) in Samarkand (1404) (figs. 1.3 to 1.5). This was originally designed for his favourite grandson, Muhammad Sultan (1375 1403), who was killed in one of Timur’s campaigns, but it later became a complex of mausoleums where Timur and his family members were buried (Golombek and Wilber 1988). Apart from the tombs of Timur’s two grandsons, Muhammad Sultan and Ulugh Beg, there are also the tombs of Shah Rukh (Timur’s son and Ulugh Beg’s father) and Mir Saed Belki Sheikh, Timur’s religious teacher (fig. 1.4). The complex includes a tomb, a madrasa and a caravanserai. The mausoleum’s architect was a Persian, Muhammed al-Isfahani, which may partly explain the Persian features such as a double dome, glazed tiles, arched recesses and geometric patterns. The tomb has an abnormally high drum surmounted by a high, rising, bulbous dome built by an emperor with a passion for heights. It is octagonal in plan: the interior is square with a projecting bay on each side.

By the 16th and 17th centuries, the Muslim empires had attained great heights. The three great powers of Islamic rule—Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal— rose and flourished in different parts of the world almost at the same time. The Ottomans captured Constantinople in 1453, and within a century they had extended their power from the gates of Vienna

FIG. 1.2 tomb of Ismael the Samanid, Bukhara, uzbekistan

FIG. 1.3 General view of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum, Samarkand, uzbekistan

to the Barbary Coast, and from Egypt and the Hejaz to the Crimea. By the early 16th century, they had reached Mesopotamia and Baghdad in the east.

21 Steepled minarets, leaded domes and ashlar walls are typical of the Ottoman architecture. Although Egypt, the Balkans, Turkey and Syria have Ottoman architecture of impeccable quality, it was in Europe that the typical Ottoman style of architecture developed. From the 13th to the 18th century, this style stabilized and persisted into the modern era.

FIG. 1.3

FIG.

Though many buildings survive to exhibit this style, there are not many tombs among them. The Shezade Mosque (1544 48) in Constantinople (Istanbul) built for Sultan Suleyman, exhibits to perfection the relationship between the component parts of the Ottoman mosque. Beyond the prayer chamber, almost in the centre of the garden, stands the tomb of Prince Shezade. It is an octagonal tower adorned with decorative stone inlay and capped by a ribbed dome, which reflects Central-Asian traditions (Fletcher 1996:616).

In Persia, the Safavids united the country and extended its borders into southern Russia. By the late 16th century, Persian intellectual and artistic activity focused on the Safavid capital of Isfahan, where a new town was established to the south of the medieval city. The Safavids developed bridge structures that not only carried traffic across rivers, but also served as dams. The shrine of Imam Reza Meshed includes caravanserais, oratories, libraries, hostels, madrasas, mosques and other buildings, but not many royal tombs. Competition between shrines produced local variations, some examples of which can be seen in Qum, Najaf, Kerbala and Samarra (Iraq). Despite these variations, however, a significant unifying character grew, that further became symbolic of Persian architecture.

By the end of the 16th century, much of northern and north-western India was under the Mughals, starting with Babur. However, the period of Mughal architecture in general, and tombs in particular, started only when Babur’s grandson, Akbar, built Humayun’s tomb in Delhi (1556 66). Mughals further developed their architecture in Delhi, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri and Lahore.

FIG.

Portal of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum, Samarkand, uzbekistan

FIG.

Main hall of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum with the graves of timur, his son, grandsons and teacher, Samarkand, uzbekistan

FIG.

Portal of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum, Samarkand, uzbekistan

FIG.

Main hall of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum with the graves of timur, his son, grandsons and teacher, Samarkand, uzbekistan

22

1.4

1.5

1.4

23 FIG. 1.5

FromPre-Mughal to MughalArchitecture

In chapter 1 we noted the three major phases of Islamic architecture—Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal. However, other Indian Islamic rulers (e.g. Afghans, Turks and Persians) had some distinctive architecture of their own before the Mughals conquered India. The Slave and Khalji architecture in India (the Qutb Minar complex in New Delhi) had the imprint of Ilkhan Iran (Persian Mongols). Later, the Tughluqs brought into India the following important architectural innovations: an octagonal ground plan for the tombs; a long niche at the centre of the facades of mosques; a pyramidal roof; glazed-tile decoration; and a combination of a pointed arch with an underlying corbel architrave. This was the beginning of the four-centred arch employed later by the Mughals (Bussagli and Sivaramamurti 1978:279).

This chapter provides an introduction to pre-Mughal (Tughluq and Lodi) and Mughal architecture, and to the influences of Persian and Indian architecture on it. A short description of the evolution, from the Slaves to Lodis and Mughals is also presented, since the architecture of earlier dynasties influenced that of the successive ones.

(8th century), which contained rules governing every phase of a builder’s work. Firstly, being a comparatively young religion, Islam promoted and encouraged scientific research, experimentation and the use of new techniques and materials. Secondly, Hindu architects did not use arches, which were the key elements of later Islamic architecture. Hindu buildings are characterized by wooden structural forms (including some masonry). This may have prevented the use of arches. Thirdly, while Hindu architecture was almost exclusively religious (temples), Islamic architecture included buildings for public use, such as mosques and madrasas. The former have small and dim cells for individual worship, in contrast to the open public spaces for community worship in mosques (Terry 1955:3). Fourthly, Hindu architecture includes designs of deities (animals and birds, for example) whose worship is forbidden in Islam. Despite these differences, Akbar made a conscious effort to blend foreign influences with local tradition, in order to achieve reconciliation between the Hindu and Islamic perspectives (Alfieri 2000:19). Examples of this mixture are to be seen in palaces and tombs built during Akbar’s reign (e.g. Fatehpur Sikri and Akbar’s tomb), which contain several types of Hindu decorations.

Hindu vs Islamic Architecture

The evolution of Indo-Islamic architecture, spanning 600 years, is traced in table 2.1. Islamic architecture differed from the indigenous Hindu architecture of the time in several respects. The early Muslim rulers relied on Hindu craftsmen, although the subsequent rulers imported craftsmen from abroad, especially from Persia. The Hindu building trade was hereditary and strictly codified according to the Silpa Shastras

1. The Hindu Influence

The Muslim conquest of northern India, in the 11th century (Qutb-ud-din Aibak, first of the Slave, or Turkish dynasty of Sultans, conquered the Rajput Chauhans who ruled Delhi) marked the clash of two religions and two styles of architecture. In the initial stages, when the clash was fierce, the fanatic Muslim invaders destroyed most of the Indian temples and other monuments. This destruction may have been motivated by two main objectives: firstly, to impose

26

the supremacy of Islam; and secondly, to provide construction materials for Islamic architectural works such as tombs, forts and palaces. For example, pillars from destroyed Hindu temples were used in the construction of mosques and other monuments in the Qutb Minar complex. The Khalji and Tughluq styles of architecture were the precursors of the later architecture of the Lodi Sultans and Mughal emperors.1 The architecture of the Lodi sultans of Delhi (1440 1520) continued with the trend of the Tughluq architecture from Turkey. Their successors, Babur and Humayun, favoured the octagonal groundplan pavilions and gardens typical of the Timurid architectural patterns of Central Asia.

Religious symbols of both decorative and spiritual value (e.g. purnakalasa or purnakumbha, padma, lotus, gavaksa, chain and bell, chakra and swastika) are an important legacy of Hindu art and culture. For example, purnakalasa is associated with Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth), and includes a foliage consisting of lotus buds and flowers. The symbol of a lotus flower represents the creation, and is very important in Hindu cosmology. The Mughal conquest of India brought new elements into Indian art, by introducing more colourful techniques of decoration (whereas the ancient Indian art relied mainly on sculpture and carving for the ornamentation of buildings).

The Mughal period can be divided into three distinct phases. During the first phase, the rulers did not pay much attention to the non-Islamic Indian architectural heritage and traditions, even though their subjects were mostly non-Muslim Hindus.

In the second phase, starting with Akbar’s reign, the indigenous influences of both Muslim and Hindu

origins were accepted. This is clearly visible in Akbar’s patronage of Hindu art and architecture. During this period, the Mughal buildings reflected a combination of the Indian, Timurid, Persian and even European architectural styles. Akbar allowed the use of Hindu motifs depicting birds and animals (e.g. elephants, lions, peacocks). For example, the purnakalasa symbol is found in such Mughal monuments (associated with Akbar) as Jodha Bai palace and Jami Masjid in Fatehpur Sikri, and Khas Mahal at the Agra Fort. The lotus symbol appears in Akbar’s tomb (Sikandra), on the spandrels of arches, and on the Taj Mahal, around the graves. As a symbol of decoration, the swastika appears on Akbar’s tomb and in Fatehpur Sikri (Birbal’s palace and the House of the Sultana).

However, Shah Jahan prevented local artisans from using animate objects, which were replaced by floral and geometrical patterns and designs. He banned the construction of temples during his reign, being less tolerant than his grandfather Akbar. Despite these vicissitudes, the Hindu influence on Mughal architecture remained strong. Havell (1912:143) notes: “…it is entirely wrong to assume, as European writers have done, that the Indian builders were wholly tutored and artistically directed by the genius of their Mughal masters.” It is true that Jahangir and Shah Jahan imported architects, designers and skilled workers from Persia and Western Asia. But many had learnt their skills in India and, “some of them might even have been the descendants of Indian captives taken by the armies of Islam”. Alberuni, the Arabian historian who visited India in the 11th century, admired Hindu building skills reflected in the Mughal architecture, notably, “making the contours of a

27

FIG. 2.2

about 10 years), and the Agra Fort—the seat of several Mughal emperors including Akbar—in order to study the Hindu architectural influence on Islamic monuments in India. We present several images on each of these, in order to concretize the above discussion on architectural designs and decorative patterns. Before we do this, however, it is important to briefly describe each of the above buildings and the Hindu influence and architectural elements found in them.

The Muslim rule in India began at the end of the 12th century, when Qutb-ud-din Aibek established the Mamluk or Slave dynasty. As the first Sultan of India, he built the Quwwat-ul-Islam (Might of Islam) mosque (the oldest in India) and the Qutb Minar. The Khaljis, who took over from the Slaves, built the famous Alai Darwaza as an extension of the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, the city wall of Siri (in Delhi) and the tomb of Ala-ud-din Khalji. Ala-ud-din Khalji was the most prominent of all the Khalji sultans (he chased the Mongols out of India) who wanted to build such grandiose monuments as the Alai Minar, near the Qutb Minar, which was never built. Nevertheless, the

FIG. 2.2

FIG. 2.3

FIG. 2.4

FIG. 2.3

Persian muqarnas in Asaf Khan’s tomb, Lahore, Pakistan

Persian decorations on an exterior wall of Asaf Khan’s tomb complex, Lahore, Pakistan

the Alai Darwaza, new Delhi

34

Khalji rule witnessed architectural progress after a lull in building.7

The Tughluq rulers (who succeeded the Khaljis), were fond of architecture, especially under Firoz Shah Tughluq who built mosques, religious schools and public works (e.g. roads and bridges). The Persian influence on Indian architecture declined during the reign of the Tughluqs. This may be explained by the occupation of Persia by the heathen Mongols who did not believe in Islam: they cut off relations with India (Alfieri 2000:37). The heaviness and bulky nature of the buildings and the speed at which they were

elaborate decoration. However, this does not suggest a total lack of decoration of Tughluq buildings. Some decoration was achieved “with polychrome techniques through alternating slabs in different colours of stone, and with “carved and moulded stucco”.

The Qutb Minar Complex (Mehrauli, New Delhi) This complex contains the first monuments of Muslim India, which date back to the 12th and 13th centuries (that is, well before the Mughal period). Work on the Qutb Minar started in 1199, with Qutb-ud-din Aibak’s victory tower, 73 metres high, celebrating the victory of Mohammad Ghuri and Qutb-ud-din over

35

FIG.

FIG.

hindu

FIG.

Minar is five-storeyed: only the first storey was built by Qutb-ud-din Aibak (a Turkish slave and Chief General of Ghuri, hence the name, Slave dynasty), on Ghuri’s behalf, during his short reign of four years; the remaining four storeys were built by his successor and son-in-law, Iltutmish (1210 36), a Turkish slave. The top two storeys collapsed during an earthquake but were restored in 1369 by Firoz Shah Tughluq (1351 88), the then ruler. Next to the Minar is the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque built on the foundations of a temple destroyed by Qutb-ud-din. This explains why Hindu motifs decorate the interior of a Muslim mosque. Other monuments in the complex include: the Alai Darwaza, a mausoleum-like gateway with lattice screens added by Ala-ud-din Khalji (1296 1316) with inlaid marble embellishments (fig. 2. 4); the tombs of Iltutmish and Ala-ud-din Khalji (see chapter 3); and a madrasa (theological college) in an L-shaped structure.

The Alai Darwaza [Gateway of Ala-ud-din (1305)] is a significant structure, which influenced later buildings such as the tomb of Ghiyas-ud-din Tughluq (fig. 3.6). Its architectural style, decoration, shape of arches and the dome conception break with the earlier simpler architecture and suggest an external influence, possibly of the Seljuk Turkish dynasty of Asia Minor. The Mongol invasions which broke up the Seljuk empire may have forced architects and skilled craftsmen to move to the Indian capital, Delhi, and work for the Khalji sultans. Pointed “horseshoe” arches are an important architectural feature of the Khalji Darwaza, not repeated in any of the subsequent buildings (Brown 1956:14 15).

The Islamic buildings in the Qutb complex are located on the site of the earlier Rajput buildings.

36

2.5

2.5

carvings on temple pillars

2.6 hindu bells and chains

The site had the foundations of Lal Kot first laid by the Tomara Rajputs, and later developed by the Chauhan Rajputs in the 12th century. The Hindu and Jain temples on the site were destroyed. Apparently, the material recovered from over 20 Hindu and Jain temples was used in the construction of the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque. Noteworthy are the various pillars of the Hindu temples used in the mosque courtyard. These pillars contain the original Indian carvings and intricate floral and other designs on sandstone, such as the chain and bells (figs. 2.5 and 2.6). There are alternate, round and square sections carved with various Hindu motifs. All the faces of the decorative figures in the pillars and columns used in the mosques have been removed. This may be explained by the lack of religious tolerance on the part of the early Muslim rulers of India, whose subjects were largely non-Muslim. The Muslim invaders regarded the Hindus as infidels.

Some Hindu motifs are visible in other buildings. For example, the typical chain and bell motif of the Hindu architecture is found on the Qutb Minar. The chain and bell motif, which suggests the sounding of the bell to invoke a Hindu deity, is found in almost all Hindu temples. In fact, the Hindu mode of prayers is, inter alia, to ring a bell to draw the attention of the gods. The Qutb Minar uses other Hindu ornamental motifs and designs, such as the wheel, lotus and tassel-like tops of plants that were developed by the local Indian craftsmen. They also appear on the tomb of Iltutmish (see chapter 3).

Corbelled arches in the Qutb complex are of indigenous Indian design. This method of building arches was not used by the Islamic builders who had inherited the true arch from the Romans.8

37

FIG. 2.6

animals (fig. 2.9). Aurangzeb is believed to have mutilated the animal figures. The Houses of the Sultana and of Birbal are considered “the richest, most beautiful as well as the most characteristic of all Akbar’s buildings.”12

Fatehpur Sikri bears the marks of Hindu architectural tradition.13 As we shall note in chapter 6, Aldous Huxley preferred the ornamentation of red stone buildings to the inlay work on marble in the Taj in Agra.

The Agra Fort

The Fort’s architecture is influenced by the Hindu (especially in the case of Jahangir’s palace), Persian and Mughal styles.14 Polygonal pillars of white marble in the Khas palace date back to the preMughal period. The Hindu influence in Jahangir’s palace includes the use of purnakalasa and padma symbols (flowing foliage composed of lotus buds, flowers and leaves) which became more popular during Shah Jahan’s reign. Other buildings in the Agra Fort15 using these Hindu symbols include the inner hall of Khas Mahal, the Shish Mahal (use of glass mosaics), and the Diwan-i-Khas (carved marble on the square bases of pillars). Hindu elements also appear on Akbar’s tomb in Sikandra (see chapter 6).

FIG. 2.7

Architectural Styles and Decorations

FIG. 2.7

Birbal’s palace, Fatehpur Sikri

FIG. 2.8

The Astrologer’s pavilion, Jain influence

FIG. 2.9 the house of the turkish Sultana, bird and animal motifs

Islamic art is an art of lines and two-dimensional forms, which were lacking in the pre-Islamic art. Mughal art is characterized by the following major techniques of decoration: Geometrical designs patterns including squares, rectangles, hexagons and octagons; Arabesques—decoration with intertwining of ornamental elements such as curved lines and foliage; Stalactites—honeycomb motifs (muqarnas) seen on the ceiling of the Taj dome; Calligraphy artistic style of handwriting; Inlay work—combination of multicoloured small pieces of glass, stone and marble; Glazed tiling—a Persian technique in which colours obtained from metallic oxides and chemicals are fused in excessive heat and poured on tiles.

40

Among the architectural decorations and techniques used in the royal tombs included in this volume, several reached their climax during the Mughal period. We describe some of these decorations below:

1. Geometrical designs. These designs date back to the 8th- or 9th-century Islamic period, when they were found, for example, in the Great Mosque of Damascus (705 15) the mosque of Ibn Tulun (876 79) of Cairo, and the mausoleum of Gur-i-Amir of Samarkand. They can take many forms: triangle, trigon, square, rectangle, pentagon, hexagon, octagon or other polygons (figs. 2.10 and 1.4). They also include stars (especially on Humayun’s tomb) and motifs with straight or curved lines. In India, the geometrical patterns were first introduced

41

FIG. 2.9

during the Delhi Sultanate, to replace animals and birds in ornamental decoration. The square and octagonal tombs of the Sayyid and Lodi dynasties at the beginning of the 15th century (e.g. Bara Gumbad in the Lodi Gardens) have some geometrical forms, which became most popular during the Mughal period. For example, these forms are to be found on white marble and sandstone, with or without jalis, in Mughal structures such as Humayun’s tomb in Delhi, the Agra Fort (especially the Jahangiri Mahal), Fatehpur Sikri (the Sultana’s House, Birbal’s palace, the tomb of Salim Chishti and Buland Darwaza), and Akbar’s tomb in Sikandra.16 Geometrical designs became less fashionable during the Shah Jahan period. One does not find many such designs in the Taj Mahal, for example. What could be the explanation for the change in trend, from Akbar to Shah Jahan, in such a short period of time? Does it reflect the whims of the designers or is it something more fundamental?

2. Arabesques. The New Oxford Dictionary of English defines an arabesque as, “an ornamental design consisting of intertwined flowing lines, originally found in ancient and especially Islamic decoration.” The flowing and curved lines usually consist of shoots or bifurcated leaves on tendrils, often representing geometrical interlacing work.

An arabesque is formed in one of the two ways: it may be formed with a geometrical design; or it may be formed by stylizing a vegetational pattern (Nath 1995). The leaves may be flat, round or pointed, but they are always attached to a stalk. Sometimes the stalk may nearly disappear under the foliage, whereas on other occasions it may dominate the ornamentation.

The earliest Muslim arabesques (e.g. in the mosaics of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem) (688) take the image of the vineyard with its interlacing leaf-scrolls and winding branches.

FIG. 2.10

Geometrical designs in the interior of Gur-i-Amir mausoleum, Samarkand, uzbekistan

The Muslims introduced the arabesque decoration in India in the beginning of the 13th century. The tomb of Iltutmish, the screen at the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque and the Qutb Minar are some examples of the use of arabesques in early Islamic buildings in India. They were later used by the Mughals during Akbar’s reign, particularly in the Agra Fort

FIG. 2.10

FIG. 2.10

42

“Informative tables containing the list of selected royal tombs, evolution of Indian architecture, and chronological lists of various dynasties add value to this book.”

ISBN: 978-81-89995-10-2

ISBN: 978-0-944142-89-9 (Grantha

|

• World

A.S. Bhalla is a Visiting Professor at the School of Contemporary Chinese Studies, University of Nottingham (UK). Formerly he was a Fellow of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge (UK) and Special Adviser to the President of International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Canada. He had a long and distinguished career in the United National Civil Service, Geneva, Switzerland. He has held academic positions at Cambridge, Oxford, Yale and Manchester. He is the author and editor of 18 books. His recent publications include: In Search of Roots; Globalization, Growth and Marginalization (also in French); Uneven Development in the Third World: A Study of China and India; and Poverty and Exclusion in a Global World (also in Japanese).

Other titles of interest: Delight in Design Indian Silver for the Raj Vidya Dehejia et al

Painted Photographs Coloured Portraiture in India Foreword by Ebrahim Alkazi with contributions by Rahaab Allana and Pramod Kumar K. G.

www.mapinpub.com

in India

Mapin Publishing

Printed

ARCHITECTURE Royal Tombs of India 13th to 18th Century A S Bhalla 152 pages, 87 colour photographs 10 colour drawings 8.5 x 11” (216 x 280 mm), hc

(Mapin)

) ₹1850

$65 | £42 2009

rights

The Tribune

FIG.

Portal of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum, Samarkand, uzbekistan

FIG.

Main hall of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum with the graves of timur, his son, grandsons and teacher, Samarkand, uzbekistan

FIG.

Portal of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum, Samarkand, uzbekistan

FIG.

Main hall of the Gur-i-Amir Mausoleum with the graves of timur, his son, grandsons and teacher, Samarkand, uzbekistan

FIG. 2.10

FIG. 2.10