10 minute read

Basawan

Mansur Active at Mughal courts in Delhi and Lahore in late 1580s, Allahabad 1600–1604, and Agra until ca. 1626

Ustad (master) Mansur received the highest accolade from emperor Jahangir, the title of Nadir al-Asr (the Wonder of the Age), for his ability to paint and preserve the likenesses of the animals and flowers that engaged the emperor’s attention. Jahangir devoted the longest passage given to any artist in Mughal history to Mansur, stating that “in painting, he is unique in his time.” 32 By studying the flora and fauna of India, Jahangir was continuing a tradition begun by his great-grandfather Babur, whose Baburnama has a section devoted to this subject. 33 Jahangir prided himself in being the first to direct artists to record these marvels of nature in natural history paintings. And in this, no one surpassed Mansur.

Advertisement

Mansur appeared as a named painter in the late Akbari period, first as one working for a senior master (notably Kanha, Miskin, and then Basawan), and later independently. He is accredited by the library scribes for his contributions to the first edition of the Akbarnama (1589–90), Baburnama (1589) and Chinghiznama. It is the Baburnama that reveals for the first time Mansur’s unique gift for animal studies, for which he was quickly rewarded with the title of Ustad (master), presumably by Akbar himself. Mansur was also recognized for his gold illuminated and calligraphed frontispieces (sarlawh) and owner-title pages (shamsa), which were as esteemed as much as painting, if not more, in some connoisseur circles (No. 34). In one extraordinary joint work, Mansur employed his unsurpassed skills in gold work to depict the throne-dais on which Prince Salim sits imperially, in exile in Allahabad (No. 35).

Under Jahangir, whom he served first as a prince-in-exile at Allahabad, Mansur increasingly came to work on independent paintings intended to be gathered into imperial albums (muraqqas) rather than contribute to integrated illustrated manuscripts, Akbar’s favored format. Mansur worked principally in fine line brushwork with thin washes of pigment, capturing the exotic nature of his subject, which he placed against a lightly sketched ground sparingly described with tufts of grass or wildflowers. What set Mansur apart from his contemporaries, and natural history painters in general, was his deep empathy for his subject matter, the creatures and plants of India. He routinely accompanied the emperor on his numerous travels, witnessing and recording his subjects firsthand. In spring 1620, Jahangir toured Kashmir to admire its natural beauty, and he recorded in his Memoirs, “The flowers seen in the summer pastures of Kashmir are beyond enumeration. Those drawn by the Master Nadir al-Asr Mansur number more than a hundred.” 34 Mansur was always at hand to capture these wonders for Jahangir’s curiosity and aesthetic pleasure.

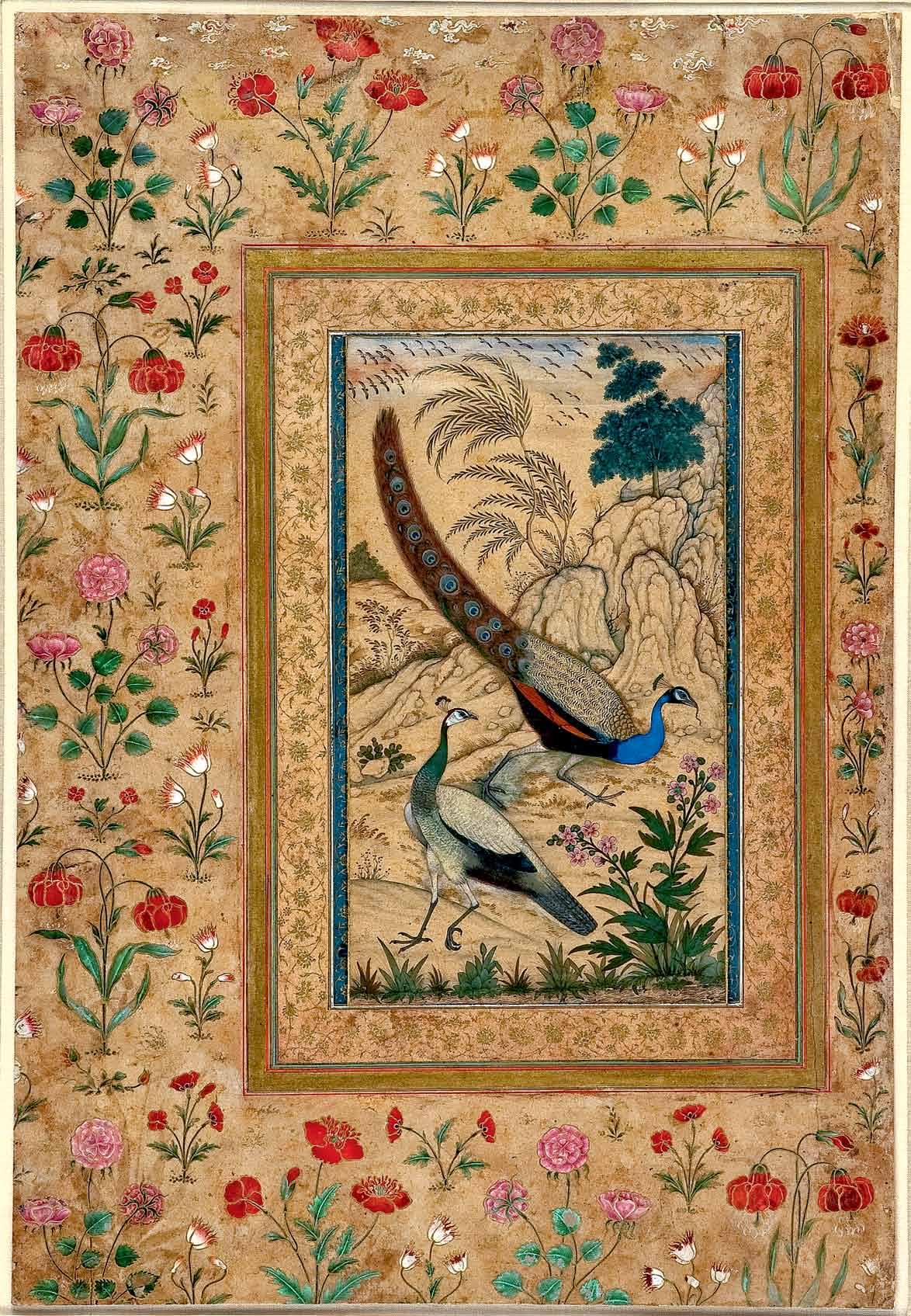

33 Peafowls

Mughal court at Agra, ca. 1610 Opaque watercolor on paper, 14 1 ⁄2 x 9 7 ⁄8 in. (36.8 x 25.1 cm) Private Collection Published: Beach et al., The Grand Mogul (1978), no. 47; Welch, Imperial Mughal Painting (1978), pl. 26; Beach, “The Mughal Painter Abu’l Hasan and Some English Sources for his Style” (1980), fig. 23; Welch, India: Art and Culture (1985), no. 144

Mansur’s ability to capture the essence of his subject is exemplified here. A male peafowl and hen display themselves in an unusually descriptive landscape, which echoes and mimics their deportment in a single vision of the unity of nature. The artist deployed Timuridstyle rock formations to add to the imperial tenor of his study of these majestic birds. The mauve markings of the male are echoed in the flowers in the foreground, his rich tail plumage in the tree beyond. An attribution to the Master (Ustad) Mansur seems secure.

Balchand Hindu artist active at the Mughal courts in Delhi, Lahore, Allahabad, and Agra, 1595–ca. 1650, brother of Payag

An Indian recruit who appears to have converted to Islam, Balchand entered the royal atelier in the last decade of Akbar’s reign and had a long career spanning the reigns of three emperors. He followed Prince Salam to his court-in-exile in Allahabad in 1600 and returned with him in 1605 to Agra, where he continued to serve at court under Shah Jahan into the early 1650s. As a junior member of the inner circle of painters at court, Balchand was entrusted in 1589 with a double spread in the Akbarnama (Victoria and Albert Museum, London) and in 1595 with painting the figures in the border decorations of a deluxe imperial edition of the Baharistan, rare privileges for his age. 35 Although his work of this period does not warrant the confidence placed in him, he matured into a master painter excelling in portraiture and was entrusted with the most important commissions of his age. The grisaille-rendered figures—termed nim qalam (half-colored) in Persian—in the border decorations of a folio devoted to Faqir Ali’s celebrated calligraphy of 1606, demonstrate Balchand’s new mastery of figure studies. The marginalia of another folio in the series depict the stages of making a calligraphic album, notably paper making, burnishing, and the act of writing (compare Fig. 16). 36

Balchand received his major imperial commissions under Shah Jahan, including a (retrospective) double-portrait of Jahangir and Akbar. As father and son are depicted in cordial and respectful attitudes, we can only assume that this was produced at Shah Jahan’s instruction to “re-write history.” Their relations were far from harmonious, the impatient Prince Salam having openly rebelled against his father. This and other works of the period demonstrate Balchand’s gift at psychologically penetrating portraiture, a talent he displayed to its fullest in the complex dardar scenes that Shah Jahan increasingly demanded. This reached its highest expression in the illustrations to the Padshahnama, prepared for the emperor under the direction of the historian Abdu’l Hamid Lahori (No. 38). Balchand’s paintings display a chromatic sophistication that enlivens and unifies his compositions.

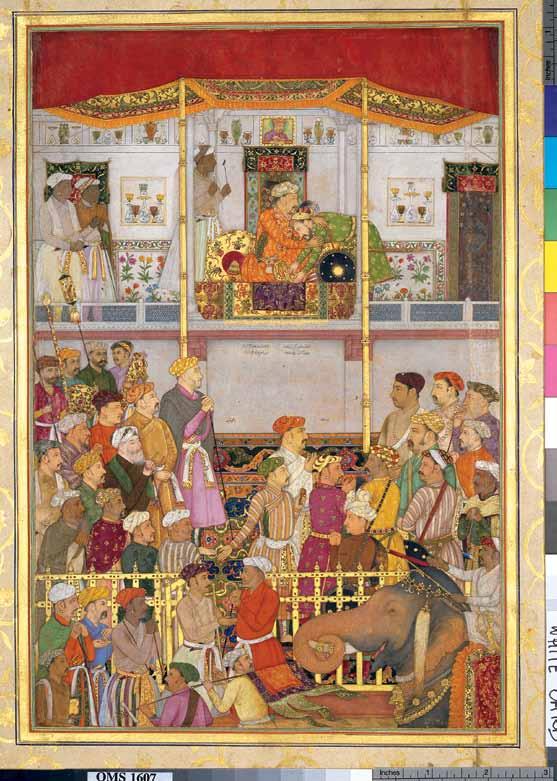

That Balchand had some standing at court beyond that of a respected painter is indicated by the inclusion of a prominently positioned self-portrait in an imperial dardar scene (No. 38); 37 to do so otherwise would have been a dangerous presumption. He displayed a picture portfolio, emblematic of his trade, upon which is inscribed “the likeness of Balchand.” This is an artist who was confident of his place in the court order.

Above: Self-portrait of Balchand, ca. 1635. Detail of No. 38

38 Jahangir receives Prince Khurram at Ajmer on his return from the Mewar campaign: page from the Windsor Padshahnama Mughal court at Lahore or Daulatabad, ca. 1635 Inscribed: signed below throne, “slave of the court, drawn by Balchand” and inscribed on portfolio held by figure at lower left, “likeness of Balchand” Opaque watercolor and gold on paper; painting: 11 15 ⁄16 x 7 15 ⁄16 in. (30.4 x 20.1 cm); page: 22 15 ⁄16 x 14 7 ⁄16 in. (58.2 x 36.7 cm) The Royal Collection, Royal Library, Windsor (RCIN 1005025, fol. 43b) Published: Beach et al., The Grand Mogul (1978), fig. 5; Losty, The Art of the Book in India (1982), no. 82; Smart, “Balchand” (1991), figs. 1–2; Beach and Koch, King of the World (1997), no. 5

Balchand was a master of composition, giv- ing subtle form and strength to potentially unruly and congested darbar scenes, creat- ing instead compact and ordered psychologi- cal dramas. In inferior hands, these scenes would become mere regimented formality, mechanical and routine. In Balchand’s, each participant has an individual presence, and the interactive dynamics among them creates an atmosphere of realism not encountered in darbars of lesser painters. His own portrait appears at lower left, with an artist’s portfolio under his arm.

Bahu Masters Active at the court of Bahu, Jammu region, ca. 1680–ca. 1720; possibly father and son or two brothers

The Ramayana, an extensive series that tells the story of Rama and Sita, serves as the first point of reference for the œuvre of these two masters at the court of Bahu, located near Jammu in the Pahari region. The manuscript, which originally consisted of more than 279 illustrated folios, exhibits stylistic variants suggesting that different painters worked on it at different times (and possibly even in different places). The pioneering scholar of Pahari painting William Archer was the first to distinguish four distinct styles in this vast work. 13 While the folios that illustrate the first part of the epic are rendered in Styles I and II, the last parts of the story were painted in two disparate styles, a feature not uncommon in larger picture series that, we can assume, were produced over an extended period of time.

The world evoked in the pictures in Styles I and II, attributed to the first and second Bahu masters, is self-contained. Stylized fields of color and delicately executed patterns dominate in these works, which are related to the earlier pictures by Kripal and Devidasa in their color aesthetic. Here, stylized colors combine with thickly applied shell-lime white alternating with pricked gold.

To enhance the effect of the monochrome ground, the first Bahu painter frequently omitted a horizon line. His architectural elements have a purely decorative quality, while all his figures are related directly to the action; they recite, listen attentively, place a hand on a neighbor’s shoulder, or gesticulate. The second Bahu master shares the same color sense, but his picture elements are arranged more carefully. Certain facial types borrow from the repertoire of the first Bahu master (although with more rounded eyes). The narrative’s immediacy is broken by the horizon line inserted high above the picture, as though the painter wished to set the story of the gods in a recognizably earthly realm.

On the basis of stylistic indicators, other works that are not from the Ramayana series discussed here can also be attributed to both painters, notably pictures for musical scores (ragamalas) as well as princely portraits. One can assume that both the first and second Bahu masters were working in the same atelier and in all probability were related, possibly father and son, or brothers.

Above: Portrait of a Bahu Master, detail from a folio of the Shangri II Ramayama series. Bahu, Jammu, ca. 1680–95. National Museum, New Delhi (62.2487)

60 King Dasaratha and his retinue proceed to Rama’s wedding: folio from the Shangri II Ramayana series Bahu, Jammu, ca. 1690–1710 Opaque watercolor and ink on paper; painting: 7 3 ⁄4 x 11 5 ⁄8 in. (19.7 x 29.5 cm); page: 8 3 ⁄4 x 12 1 ⁄2 in. (22.2 x 31.8 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Dillon Fund, Evelyn Kranes Kossak, and Anonymous Gifts, 1994 (1994.310)

Published: Czuma and Archer, Indian Art from the Bickford Collection (1975), no. 110; Kossak, Indian Court Painting (1997), no. 42

Rama’s marriage is the central event in the Ramayana. Here, King Dasaratha is seen on his way to the wedding, accompanied by an ostentatious retinue with standard bearers, trumpeters, and drummers. Similar compositions by the Second Bahu Master document the return of the wedding party after the ceremony. 14 A horizon line is included in those works, but it is missing in this one. The pictures of the Second Bahu Master also differ in other details, including the physiognomies of the figures. And, while here the wheels are spoked, they are solid in the pictures of the first masters.

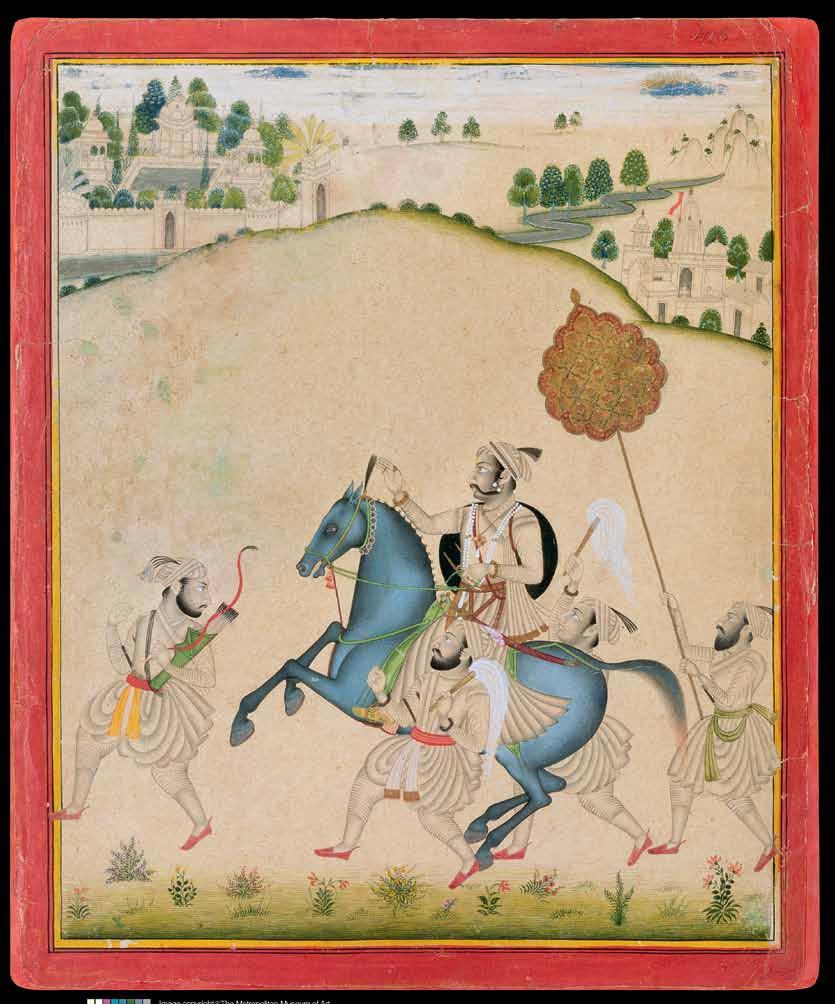

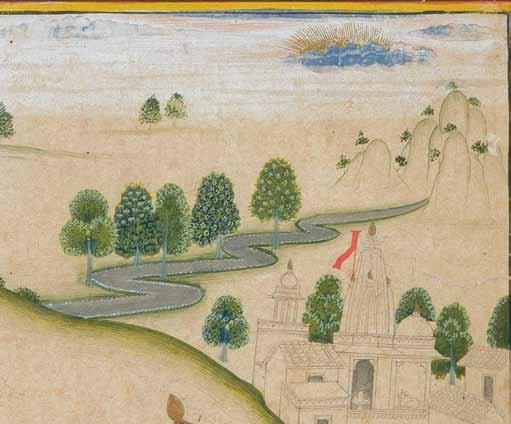

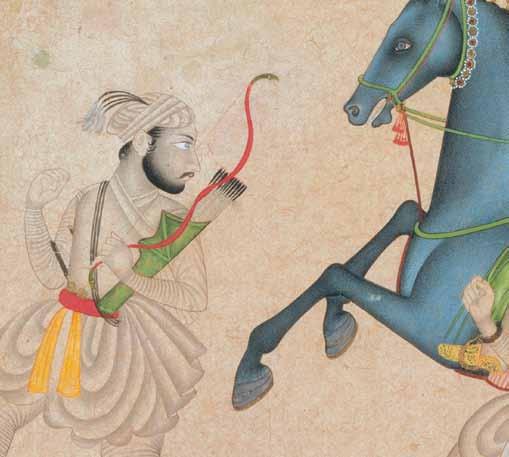

65 Maharana Amar Singh II riding a Jodhpur horse Udaipur, Rajasthan, ca. 1700–1710 Inscribed: on reverse in devanagari script, “it is from Jodhpur” Opaque watercolor and ink on paper; painting: 13 3 ⁄16 x 10 3 ⁄4 in. (33.5 x 27.3 cm); page: 14 11 ⁄16 x 12 1 ⁄8 in. (37.3 x 30.8 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B. Polsky Fund, 2002 (2002.177) Published: Sotheby’s New York, December 10, 1982, lot 91, and March 22, 2002, lot 20

Numerous pictures exist that depict Amar Singh on horseback with attendants, clearly one of the Stipple Master’s favorite subjects. In such works, the focus is on the main subject, the horse, painted a radiant blue. The foreground is marked by only a few tufts of grass, and in the background, beyond the lightly shaded crest of the hill, there are a temple and a palace pleasure garden. The understated technique displayed by this artist has echoes of the Persian–Mughal painting technique of nim qalam, half-tone painting, a variant of European grisaille techniques of tonal painting.