3 minute read

the golden age of mughal painting 1575–1650

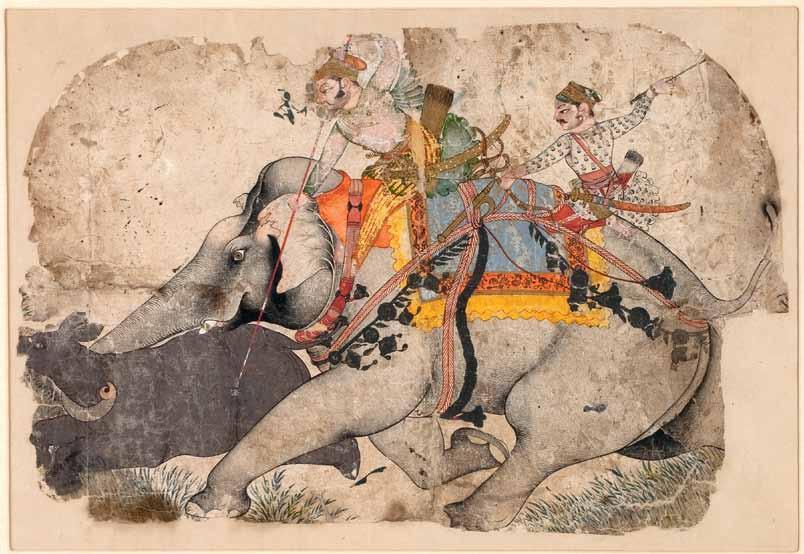

67 Ram Singh I of Kota hunting rhinoceros

Kota, Rajasthan, ca. 1700 Opaque watercolor on paper; page: 12 5 ⁄8 x 18 3 ⁄4 in. (32.1 x 47.6 cm) Private Collection Published: Lee and Montgomery, Rajput Painting (1960), no. 36; Beach, Rajput Painting at Bundi and Kota (1974), figs. 71–77; Welch, India: Art and Culture (1985), no. 242; Welch, Rajasthani Miniatures (1997), fig. 1

Advertisement

Although badly damaged, this hunting scene is one of the most dramatic known examples of the genre. The elephant as combatant was a favored subject in the court painting of Bundi, from which the Kota school evolved following the creation of that state by Shah Jahan in 1631. The subject of this painting, the elephant and two noble riders, are united as a single force, pitiless in pursuit of their prey. The Kota Master created one of the most powerful renderings of the hunt in Indian art, with skilled tonal modeling of the beasts and restrained use of color that is confined to the elephant’s harnessings and blankets. Stuart Cary Welch wrote of this work that such is its compelling energy that it makes us “feel the thud of feet and the lashing of ropes, and hear the clang of bells.” 22

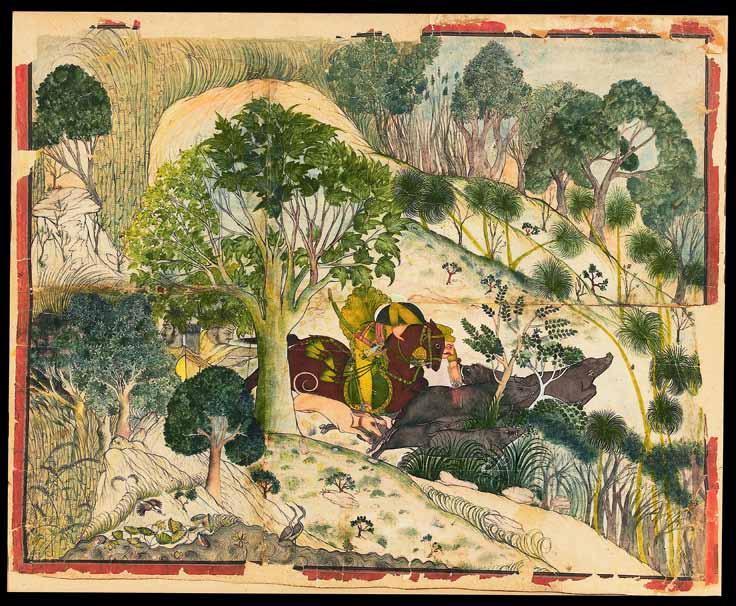

68 Rao Madho Singh of Kota hunting wild boar Kota, Rajasthan, ca. 1720 Opaque watercolor on paper; page: 19 11 ⁄16 x 24 1 ⁄2 in. (50 x 62.2 cm) The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, lent by Howard Hodgkin (LI.118.79) Published: Topsfield and Beach, Indian Paintings and Drawings from the Collection of Howard Hodgkin (1991), no. 35; Bautze, “Portraitmalerei unter Maharao Ram Singh von Kota” (1988–89), fig. 14

The drama of the forest hunt depicted could hardly be surpassed. Madho Singh lunges forward, clutching the neck of his mount, to deal the deathblow to one of the boars with his punch-dagger (katara). The hunting dog and the rider’s tassels flying out behind underscore the dramatic movement as they dash through the wooded landscape. Despite the apparent spontaneity of this work, with its confident application of light brushwork, the composition is in fact directly modeled on an earlier mural painting preserved at the neighboring state of Bundi. 23 This relationship between wall paintings and works on paper underscores a wider phenonemon in Indian painting that, however, can be securely documented only rarely.

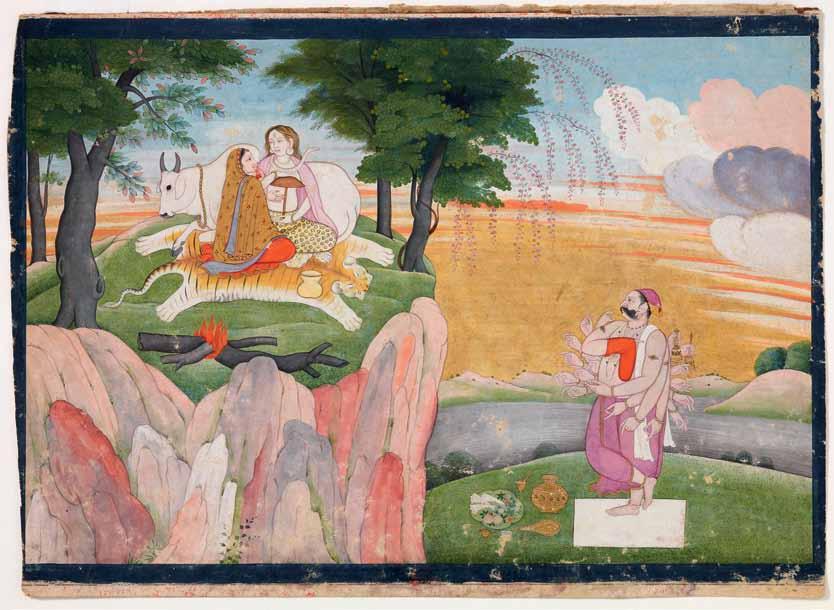

88 Banasura’s penance, his vision of Shiva and Parvati: folio from an Usha-Aniruddha series Probably Chamba, Himachal Pradesh, ca. 1775 Opaque watercolor on paper; painting: 8 1 ⁄16 x 11 15 ⁄16 in. (20.5 x 30.4 cm); page: 8 15 ⁄16 x 12 3 ⁄8 in. (22.7 x 31.4 cm) Museum Rietberg, Zurich, Collection Eva and Konrad Seitz (B 41)

The subject of this series, the story of Usha and Aniruddha, is found in the tenth book of the Bhagavata Purana. One night, Banasura’s daughter Usha dreams of the handsome prince Aniruddha and surrenders her virginity to him. Banasura goes to war against Krishna over this stain on his family honor. But his life is saved thanks to the intervention of Shiva, and in the present painting, Banasura is seen worshipping Shiva and Pavati enthroned on Mount Kailash. This work is attributed to Nikka (ca. 1745–1833), third son of Nainsukh, who enjoyed the patronage of Raja Raj Singh of Chamba and was granted land there, which his descendants still occupy to this day.