ISSUE

02

Phantasmagoria 15,50€

To animation and beyond www.marimomag.com Co-founder & Creative Director Adeline Marteil adeline@marimomag.com Co-founder Ingrid Mengdehl

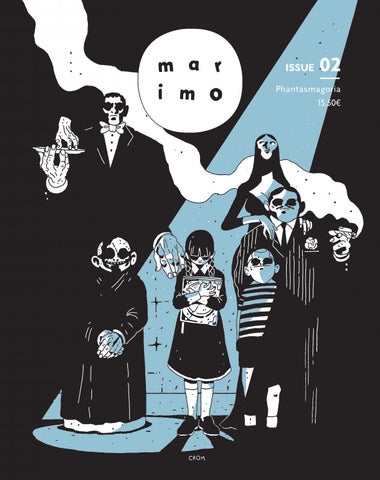

Fonts Arazatí family Cavita Rounded family Rogliano family Alacena family by TipoType Cover art CROM

Chief-editor Adeline Marteil

Marimo magazine Issue 002 - Phantasmagoria ISSN 2557-9223 Published in December 2018

Editors JoyNoël Elett Brice Fallon Ko Ricker

Marimo S.A.S 15, rue Vergniaud 92 300 Levallois-Perret France

Assistant editor Laura-Beth Cowley

©2018 Marimo magazine All right reserved All material in this publication may not be reproduced, transmitted or distributed in any form without the written permission of Marimo.

Translation Yasmeen Kharrat Printed in Czech Republic by PBtisk a.s. on FSC certified papers from the Munken range by Arctic Paper

With kind support of our generous Kickstarter backers: Sophie Arouet Assembly BrightCarbon Carl Samantha Bastien Barbara Carswell Laura-Beth Cowley Edward Culbreath @natallyillustrations Sara & Mickaël Donati Véronique William & JoyNoël Elett Jorge Orozco Fonseca Ronan Guilloux Viviane & Serge Guilloux David Hury L & L Hury Clémentine & Hervé Marteil James Mcfarlane Stephen Monger David Perlmutter

Welcome The Marimo’z are excited to present our spooky second issue. Throughout its short history, Marimo has faced ongoing challenges — whether it’s an economic hurdle or a fast approaching deadline, our growing team has had much to learn from every new experience. We come from a variety of fields, among them animation, academia, and journalism, and we are all determined to make use of our strengths in order to keep the adventure going, step by step. By continuing to refine the magazine’s format and content, we Marimo’z have set a high bar for the future. Just like with animation itself, it takes time and sweat to make the magic of Marimo happen, and we couldn’t have done it without the support of our wonderful Kickstarter backers. To everyone who contributed to our campaign: we thank you from the bottom of our hearts for helping make the production of our sophomore issue possible! Sorcery is at the core of the following pages. The art and industry of animation have always given rise to an extremely powerful form of storytelling, especially so when a work’s inspiration is founded in our deepest dreams and nightmares. Animation’s suitability as a medium of ghostly and necromantic tales is proven by the vast repertoire of phantasmagoric animated works. When it comes to dark matters such as death, demons, and other monsters that haunt our imagination, animation has the ability to embody grim storylines for both young and old, whether it means exposing small children to difficult subjects, or allowing mature viewers to face their most visceral feelings. Whoever the audience, the animators profiled in this issue have found the dreamscape to be a deep well of inspiration, and we doubt they will ever exhaust its potential. Who is behind these macabre creations? Who are the storytellers of “the other side”? Who envisions this other reality? Why have so many of them chosen this apparently “childish” medium to tell their most tremendous tales, and how do they go about it? Like you, we at Marimo are enchanted by the witchcraft of animation, and we’d love to explore some of the answers to these questions together. We hope you enjoy sinking your teeth into this haunted reading!

Adeline

Contributors

Zay Balami Writer @zazouzay zbalami.weebly.com

Cole Delaney Writer coledelaney.me

Guy Carnegie Poet @gcdesigndevelopment guycarnegie.co.uk

JoyNoël Elett Writer @thejoyfulnerd

Robbie Cathro Illustrator @robbiecathro robbiecathro.com Alessia Cecchet Writer @alessiacecchet alessiacecchet.com Lorenzo Cervantes Writer @LBCowley laura-bethcowley.co.uk Laura-Beth Cowley Writer @lorenzo.cvts @lolovantes CROM Illustrator @crom_cristianortiz Tom Deason Illustrator @_tom_deason

Ian Moore Illustrator @iam.ian.m

Any-Mation

Ian Failes Writer @vfxblog Brice Fallon Writer Ben Lewis Giles Illustrator benlewisgiles.format.com David Hury Writer davidhury.com Vanessa Lovegrove Illustrator vanessalovegrove.co.uk @vloveg

Timothy David Orme Writer timothydavidorme.com Ruth Richards Writer Ko Ricker Writer ko-ricker.com Eric Rittatore Writer @EricRittatore Sam Shaw Illustrator @samshawdraws Marta Zubieta Illustratorr @onirical_zubieta

Ben Mitchell Writer @benlmitchell ben-mitchell.co.uk Sophie Monks Kaufman Writer @sophiemonkskaufman @sopharsogood

Special thanks to: Clémentine & Hervé Marteil, Ronan Guilloux, the ace Alix Abanda, Axel Luzayadio (Le Blog de Cheeky), Les Éditions Issekinicho, and the wonderful editors who helped bring this issue into your hands.

10 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Contents 10

The walk from the gate

13

Lanterna magica

15

Robertson's Phantasmagoria

16

A brief history of macabre in animation

19

amela Pettler P Breathing new life into the Addams Family mausoleum

23

hantom Boy P Hovering between life and death

27

Into the realm of the Forgotten Forest The inspiration that led to creating a new animated series pilot with Cartoon Network

30

ropes and themes of folklore T in Japanese animation Case study: A Letter to Momo

33

Rosto Somewhere between waking and sleeping

34

roken screws and dusty puppet eyes B Mise-en-scène in the Quay Brothers

36

obert Morgan R An unceasing series of nightmare visions

38

he little factory of the great thrill T LAIKA Studios

48

things you need for a good feature 3 A good script, a good script, a good script

53

Harryhausen and his dinosaurs

54

ortfolio: Red Nose Studio P Bringing life to illustrations with stop-motion animation

Smoke & mirrors

66

FX: the ultimate illusion V Matte painter Yvonne Muinde on making the unreal, real

68

ow did they do that? H VFX pros love being fooled by illusions, too

70

Deep in the uncanny valley

74

Watchlist

76

Playlist

80

The Glassworker

86

ringing your ideas to light B A look at the challenges of the animation business and team building

89

omen who animate W Perceptions, prejudice and the fight for change

94

omen in animation W 12 personalities

11 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

62

Essay

THE WALK FROM THE GATE

12 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Guy Carnegie

Essay

The walk from the gate is a two-headed beast, By day there is nothing to fear in the least. Beautiful flowers and trees boast their wares, An orchard of apricots, lemons and pears. Gargantuan trees, thick with leaves reaching high, Almost so much that you search for the sky. Squirrels and pigeons, all manner of creatures, Nature euphoric, in all of it’s features. At night when the time comes to put out the bin, One makes out the streetlight that soothes one within. But then coming back in the other direction, Causes a moment of quiet reflection. The walk from the gate is around sixty seconds. The bin is put out and a comfy home beckons. The walk back now technically is just the same, Only now there’s a feeling I’m part of a game. The darkness is palpably clear in these fences, One’s eyes straining, coupled with such heightened senses. Tricks of the moonlight transforming a thicket, The pantomimes started, did I buy a ticket?

The walk from the gate is a two-headed beast, By day there is nothing to fear in the least. But night time has managed to hijack my thoughts, The walk from the gate is a walk of all sorts.

13 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

How can one minute now seem to be five? Why does this garden now seem so alive? I’m sure I just saw a dark figure dash by, But I know in the day I’d not batter an eye.

WithPhantasmagoria kind support

Since 1991, TVPaint DĂŠveloppement crew has been developing with heart and soul a versatile 2D animation software called TVPaint Animation, to bring efficient digital solutions to traditional animators all around the world.

14 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

tvpaint.com

Phantasmagoria

Lanterna magica According to Goethe, the world without love was "like a magic lantern without light". The magic lantern is a pre-cinema device where images are projected onto a wall or screen in a dark environment. It is a closed box containing a candle, and light filters through a hole on which a lens is applied. The earliest slides, support of the projected illustrations, were hand-painted on glass. Later, inventive mechanisms were devised to achieve basic moving pictures. Over the years many technical evolutions occurred, but the magic within remained intact.

In small villages, and in the squares, the real and the fantastic, romantic, legendary, and mythical lived together on the painted slides. The Count of Cagliostro used it to feed his own fame. Ingmar Bergman elected it as a symbol of human beings' primordial fantasy. For Francis Ford Coppola, the cinema, in its integrality, came from the first magicians and lantern shows. Ghosts, devils, gargoyles, dreams, and nightmares also took life, helped by old special effects and the talent of the lanternist, both operator and showman who was the real liaison and interpreter between “real” world and the “fantastic” one.

Invented by Dutch physicist and astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629 – 1695), the magic lantern spread rapidly in European Courts both as an attraction and didactic tool–functions that tend to merge and overlap in such suggestible periods in which science and imagination still went hand-in-hand.

Without knowing it, popular imagination was being shaped and recoded, later to be ready to welcome and celebrate Lumière Bros' Big Revolution. But the Lantern has survived, continuing to pulse its suggestions in the dark, to benefit some nostalgic loyals to that era of mystery, enchantment, and–perhaps–lost innocence.

15 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Text by Eric Rittatore

16 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Phantasmagoria

Phantasmagoria

Robertson's Phantasmagoria The illusion of afterlife Text by Cole Delaney Illustration by Vanessa Lovegrove

I

magine walking into Pavillon de l’Échequier in Paris one spring evening and sitting with several friends, hoping to experience a new theatrical event. As the candles are extinguished plunging the hall into darkness, the spectral drama unfolds. Smoke creeps across the room and people rush forward to the host asking to see phantoms of the past. Spectres hover above, winking in and out of existence, and people begin to flee the theatre in terror. Whispers or claps of thunder causes others to draw swords, or cry in panic. The host, Étienne-Gaspard Robert, or better known as “Robertson”, through his Fantoscope, conjures image after ghostly image, moving them closer to the petrified audience, keeping his promise and bringing the dead back to life. This is Phantasmagoria.

The most interesting part of Phantasmagoria is probably the crude indications of early animation. His Fantoscope was on wheels, so it could move forward or back, to create the illusion of the spirits growing larger. Also, the aperture could be adjusted to allow more light through the magic lantern, which made the ghost glow with more intensity as it rapidly approached. Robertson’s adjustment to the magic lantern also allowed him to use multiple slides in a single projector, which could create a crude semblance of movement. A face was given brighter eyes, and then that slide could be removed to create the illusion of life in the phantom. Phantasmagoria is central in the history of imagination. A mixture of dark, smoky, moving imagery as spectres crept in and out of existence around the audience, mixed with the eerie voices projected by a ventriloquist and accompanied by the unsettling tones of a glass harmonica; you can imagine the chilling effect it could still have today. Thankfully, through his Mémoires, he left detailed instructions on how each effect was created. This is close to 80 years before Eadweard Muybridge began his pioneering work on animal locomotion. Robertson’s adaptations on the magic lantern marked an important step toward the idea of successive images being played over each other, creating movement in order to animate, which of course means, to “bring to life”.

17 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

In 1797 France, as Robertson began his Phantasmagoria, there was a heavy interest in the macabre following the Reign of Terror (1792-1794). If executions weren’t enough, the public could now witness what they thought happened after life. Robertson had a similar dark interest since childhood and because he was a scientist, his equal interest in optics led him to early magic lantern shows. Following these, he developed many of his own techniques to make a new type of event: an immersive, horror spectacle. But also to help it stands out from the eventual copycats that emerged as his secrets were revealed.

Phantasmagoria

A brief history of macabre in animation Text by Cole Delaney Illustrations by Vanessa Lovegrove

L'Hôtel Hanté : fantasmagorie épouvantable In 1907 J. Stuart Blackton used stop-motion to show a dinner making itself in “The Haunted Hotel”. The relatively close up shot allowed animators to study the technique while the length of the sequence removed any doubt of previous visual tricks such as wires to move props. The short film was so successful in France, that over the next decade, the French term for animation was le mouvement américain and influenced many filmmakers including Émile Cohl.

American innovators

18 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Walt Disney’s Silly Symphony series began with the short “The Skeleton Dance” (1929), where skeletons dance and make music in a cemetery. A very literal example of the danse macabre. The gothic backdrops would carry a thread throughout Disney’s catalogue, like the landscape and themes of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937) and Pinocchio (1940), and the “Sleepy Hollow” section in The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949). Conversely, the Fleischer Brothers explored darker tones with Betty Boop shorts, highlights including “Minnie the Moocher” (1932) and Cab Calloway’s rotoscoped performance in Snow-White (1933). Other studios were dabbling in the otherworldly too, like Famous Studio’s The Friendly Ghost (1945) which introduced Casper.

Smaller screens and bigger audiences In 1953, UPA released their gothic short “The Tell Tale Heart” (1953) from Edgar Allen Poe’s catalogue and due to its dark subject matter, earned the first X rating for animation in the UK. As well as UPA, Hanna-Barbera also dominated the small screen and in 1969, released Scooby Doo, Where Are You! followed by The Funky Phantom (1971). They also brought back the Addams Family in Scooby Doo, marrying the macabre styles and granted them their own animated show in 1973. In Britain, Cosgrove-Hall released Count Duckula (1988), rooted in the European Gothic fiction of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, with an anatidaedian twist.

Phantasmagoria

Eastern perspectives With the advent of television, Gothic subculture in music, and global economies cross pollinating culture, the gothic influence crept into eastern animation, albeit with their own style. Kuri Yoji explores a surreal, macabre landscape in the darkly compelling “The Midnight Parasites” (1972). Though the biggest influence is in Goth-Loli, which is a cross between the Lolita style with a darker influence, exemplified in Amane Misa from Death Note (2006). Kawamoto Kihachiro’s “IbaraHime matawa Nemuri-Hime” (1990) model animation reimagined the story of Sleeping Beauty, rooted in European Gothic culture.

Don’t stop believing

Goth girls have more fun With the emergence of the Gothic subculture in music, goth identification became individual, rather than just a setting or tone. Married with the resurgence of animated cartoons through the 1990s, these individuals, primarily “Goth Girls” began to populate series. Examples include Lydia Deetz from Beetlejuice (1989), Andrea from Daria (1997) and in more recent animation, Mai from Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005), Marceline from Adventure Time (2010) and the Librarian from Hilda (2018). Moving back to re-establishing the gothic as an environmental presence rather than just character, Over the Garden Wall (2014), and the online GIF shorts of OivaviO Motion Stories (2014-18) set themselves apart by grounding in the macabre.

19 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Animating the macabre seems to go hand in hand with stop-motion. Even with the greatest care, movements still feel uncanny. In Prague, Jan Švankmayer’s output militantly stuck to the surreal, culminating in Alice (1988), known for its dark and uncompromising design. His work deeply influenced the gothic animation of Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993). Burton carried this style consistently through his stop-motion projects. Paul Berry’s “The Sandman” (1991) is an important short that continued the macabre style, similar to the work of the Brothers Quay. Henry Sellick directed Nightmare, and then adapted James and the Giant Peach (1996) before joining Laika Studios and settling their style in Coraline (2009). They carried this forward through Paranorman (2012), The Boxtrolls (2014), and Kubo and The Two Strings (2016).

20 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Interview

Interview

Pamela Pettler

Breathing new life into the Addams Family mausoleum Interview by Laura-Beth Cowley Illustrations by Sam Shaw based on Charles Addams' characters

“Click, click...” When you were growing up what kind of stories did you gravitate towards? I loved reading books with dark humor, even as a small child. My father was a Professor at U.C. Berkeley, originally from Prague, and my mother grew up in London, so they both imbued me with a lifelong love of reading, as well as their shared mordant wit. I loved Roald Dahl (especially his adult short stories), Edgar Allan Poe, and the Gothic Romantic novels Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights. What is your favourite film? That’s a hard question to answer with just one film! I think I would say Edward Scissorhands. But I also like Kind Hearts and Coronets. How did you start screenwriting? I have always written, even as a little girl. I also loved music, and played piano and viola, and after a year at a conservatory in Geneva, decided to study music in college. I figured you don’t become a writer by “studying English”, but by living life! So I got a Ph.D. in musicology and taught college for a number of years before realizing I was truly meant to be a writer. I moved to

Los Angeles when I got married, and started over in my new career. I just wrote and wrote and wrote. I wrote lots of spec scripts, which got me an agent, and then I went to every possible pitch meeting, and eventually people started offering me jobs. My first assignment was writing a televised after-school special about a 12-year-old boy who turns into a werewolf for two minutes at a time. I think it is simply what I do. I gravitated towards the kind of writing I love best; dark, funny fantasy! What consideration do you have to make when changing quite macabre or dark subject matter into family films? I love writing dark movies with a streak of humor and sweetness, something the whole family can enjoy. I think if you write with sympathy and humanity and a wicked bit of wit, your movies can connect with everyone of every age. It’s a matter of tone, of being on a certain wavelength, and I get there completely intuitively. I check in with myself: does this feel right? Is it somehow too mean, too scary, too dark? I’ve been writing this way all my life, so I have an intuitive feeling for what is right. The real key is to know that you CAN go dark, you don’t have to be sappy or trite, even if you’re writing to include children. Children, too, have a complicated emotional life and a welldeveloped sense of dark humor! (Look at Wile E. Coyote if you doubt it.) What are your thoughts on horror or creepy stories that are initially intended for a child audience? At the end of the day, I write for myself and for other adults with a wicked sense of humor. I know that something with a dark streak can work for everyone because I spent every night making up stories for my son when he was growing up. I don’t really write straight horror, or even straight “creepy” stories, but stories that have what you might call a “wicked wit”; slightly twisted, but always emotionally real and always positive and sweet.

21 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

T

hey’re mysterious and spooky and altogether kooky and they’re coming back to the big screen in fully animated splendour in October 2019. The dark and comical wit of Charles Addams is once again being reinvented, this time in CG. We were fortunate enough to get some time with the delightful weaver of the macabre, screenwriter Pamela Pettler. Pettlers' previous writing credits included Tim Burton's Corpse Bride and Gil Kenan’s Monster House. No stranger to the gothic and the supernatural, she was a clear choice when revitalising the classic, unusual family we all secretly hoped to be a member of.

Interview

22 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

“ It’s about finding your tribe, your true, artistic, emotional self and allowing yourself to live your life.”

Interview

What can you tell us about the difference between writing for live action, CG animation, and stop-motion animation? That’s a very interesting question. There are absolutely some imperatives for every medium. In live-action, for example, writers and directors often depend on reaction shots, or the look on someone’s face, and you can’t do it as well with animation, or at all with stop-motion. So you have to take this into account when you’re writing a character’s reaction; they have to have a line or an action, you can’t just write “on Victor’s wistful face, we dissolve to.” You have to give Victor a line or an action (“Bending his head in sorrow, Victor looks down at the jasmine blossom”). When writing for stop-motion you have to take into account the limits of hand-moved maquettes; “She dissolves into a thousand little butterflies” becomes “She dissolves into a butterfly.” There’s another funny need in animation: on some intuitive level, the audience needs movement on-screen (if you will, animation). So you always have to have some kind of action happening on-screen. We as humans are always picking up tiny inflections of expression or the look in their eyes with live actors, but with animation, you can’t get that, so you need to replace it with something happening: the person is sketching, perhaps, or something is happening in the background.

When it comes to writing character and story, I have to say that I write all my scripts exactly the same way. I think about the character’s humanity, and who they are, and how they drive the story, and write it in a pure kind of way. I can always adjust for limitations or necessities later (much of production rewriting is exactly that, anyway!). What can we expect from the new story? I had so much fun working with the original material of Charles Addams’ original cartoons, in all their macabre glee and side-splitting wit and humor. I grew up with his cartoons in The New Yorker, and it was blissful to work with those unforgettable characters and to write their dry, wicked, but always relatable personalities. I think Uncle Fester was a particular favorite of mine to write dialog for. I wrote a script that is wonderfully dark, wonderfully touching, wonderfully human, and with a real sense that the Addams Family stands for all of us who are a “little bit different”. THEY’RE the normal people in the movie, everyone ELSE is weird! It’s dark, funny, and lots of fun for the whole family. Conrad Vernon is a wonderful director with a fantastic sense of animation that jumps off the screen at you, so I’m really looking forward to seeing how he brings it to life!

23 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Corpse Bride, for example, was about how the dead are less inhibited, and so they teach the living how to really live. It’s about finding your tribe, your true, artistic, emotional self and allowing yourself to live your life. With Tim Burton’s imagery, the “dead” were quirky and often funny, and always in some way appealing. We created what may seem at first blush to be a “horror” movie but in fact is a very sweet, touching story, in which some people happen to be living underground. Likewise, Monster House was about three kids that no one will listen to, and even the scares had a sense of humor.

Essay

24 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

©2015 - Folimage / Lunanime / France 3 Cinéma / Rhône-Alpes Cinéma

©2015 - Folimage / Lunanime / France 3 Cinéma / Rhône-Alpes Cinéma

Essay

Phantom Boy Hovering between life and death Text by Ruth Richards

2. a. A thing (usually with human form) that appears to the sight or other sense, but has no material substance; an apparition, a spectre, a ghost. Phantoms are associated with the illusory, with ghosts and spirits, with hauntings and with death. Some of the earliest experiments with moving images, magic-lantern shows, were popularised by phantasmagoria – ghost stories – in which spectral images, apparent to sight but not to touch, were projected on screens, used to frighten and amaze audiences. Rather than seeking to frighten its audience, the 2015 animated feature film Phantom Boy (dir. Jean-Loup Felicioli and Alain Gagnol) takes this traditional understanding of a phantom and incorporates within this ghostly apparition a childlike sense of wonder.

T

he film opens with Léo, 11, reading a detective story to his little sister, Titi. It’s his last night at home with his family before he goes into hospital for an extended stay, to receive treatment for a serious illness. Titi is too young to fully understand why Léo has to go for such a long time, but she is nevertheless worried, asking her brother if he’ll be gone a long time. Léo is honest with her; it’s a serious illness and he doesn’t know how long he’ll be gone, but he has a secret to share with her: “Something strange happened when I first got sick. Something absolutely incredible. Do you want to know my secret? You can’t tell anyone, okay? Okay, listen up. You’ll love this.” It isn’t long before we learn Léo’s secret, too. We next see him when he has been at the hospital for month, and has lost all his hair. The family are waiting for test results to determine whether the treatment is working. Léo’s mother, who visits every day, comforts him and promises to stay until he falls

asleep. As Léo lies down and closes his eyes, his phantom rises from his body, a ghostly double. We watch as Léo glides through hospital walls and visits his family at home. Even though Léo has told Titi his secret, she only imagines that she can see him, reading to him and talking to him as if playing a game. Léo can only silently observe. PHANTOM ENCOUNTERS Phantom Boy is the second film from Felicioli and Gagnol. Animated in the same distinctive style as A Cat in Paris (2010), it is part crime fiction, part noir, and part superhero story; the narrative is more than a little like the detective stories that Léo loves to read. The film sees Léo using his newfound phantom power to help police officer Lieutenant Alex Tanner and journalist Mary Delaney bring down the self-described criminal mastermind, “The Man with the Broken Face”, who is holding the city of New York to ransom, threatening to release a computer virus that will send the city “back to the Stone Age”. Léo first meets Alex in the hospital, after the officer has been found injured and left for dead at the docks. Alex wakes to find himself in the hospital waiting room, and instinctively tries to comfort a distraught Mary. He quickly realises that Mary has no idea he is there, as his hand passes right through her. It is here that Léo appears; he leads Alex back to his physical body, unconscious in a hospital bed. Still confused, Alex’s phantom begins to disappear, disintegrating into particles of glowing blue light; Léo quickly reunites phantom and body before Alex disappears completely. Léo saves many other patients whose phantoms have separated from their bodies – an elderly lady who fell down the stairs, a man whose phantom was waiting for the bus at midnight. People, like Alex, who do not realise what has happened to them. If these people are not returned to their bodies in time, they will fade away and disappear completely.

25 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

The Oxford English Dictionary provides the following definition of the word “phantom”:

Essay

“ The phantoms can be understood as doppelgängers – uncanny doubles of living bodies, familiar and unfamiliar, omens or encounters with death.” When Alex next meets Léo, with phantom and body “united”, he remembers him only as a dream. Léo is ecstatic that Alex remembers him at all – normally, people don’t recall their phantom experiences. He tells Alex: “I helped you wake up. I often do that with people who are sick.” He soon proves to Alex that what happened was no dream, explaining that whilst no one can see or hear his phantom, he can still talk to and hear others through his physical body. Léo explains that whilst no one can see or hear his phantom, he can still communicate with others through his stationary physical body. As a phantom, Léo exhibits a freedom of movement that is impossible in his corporeal form. When he flies, his phantom stretches and elongates as he loops through the sky; he bends and distorts as he passes through solid objects. He is at times transparent, and sometimes forgets his own immateriality, getting frightened when a truck suddenly appears but passes through him harmlessly.

26 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

LIFE AND DEATH Léo’s adventures as “Phantom Boy” could be understood as the fantastical storytelling of an imaginative child with a love of superheroes and detective stories, an escape from a less than ideal reality. But Léo’s actions in his phantom form have material consequences. The more time he spends as a phantom,the more tired and sick he becomes. Significantly it was when Léo became sick that his phantom abilities emerged, and his phantom and his physical body are never totally disconnected. The phantoms Léo helps return to their bodies enter this state unexpectedly, due to accident or injury – they quickly lose the memory of their phantom wanderings when they are not in danger of dying. Léo, constantly hovering in a state of uncertainty, between life and death, not only retains memory of his phantom, but the ability to freely enter this state, between the corporeal and incorporeal. But like the phantoms he helps, Léo will also fade and disappear if he strays too far or too long from his physical body: “Well, my phantom can’t actually leave for too long. Otherwise, he’ll fade away and so will I.”

Near the end of the film, Léo nearly disappears for good after straying from his body for too long. Falling into a coma, his doctor remarks that although his blood tests should have signalled a hopeful recovery, it’s “as if he went beyond his limits.” The body and the “spirit” cannot exist fully independent of each other indefinitely. STRANGENESS AND WONDER In one sense, the phantoms can be understood as doppelgängers – uncanny doubles of living bodies, familiar and unfamiliar, omens or encounters with death. And yet Léo, occupying the space between death and life, does not exude a sense of the uncanny; as Hélène Cixous notes, that which we would find uncanny in real life, is not so in fiction: “Fiction (re) presents itself, first of all, as a reserve or suspension of the Unheimliche: for example, in the world of fairy tales the unbelievable is never disquieting because it has been cancelled out by the convention of the genre.” (546-547). Léo sometimes expresses a certain ambivalence about his phantom, telling Titi (of his “secret”) that it is both strange and incredible. He later says of his abilities to Alex, “It’s funny, isn’t it? Actually, it’s not that funny. It’s just weird.” That which allows him to escape the stresses and worries of the hospital, and to stay close to that which is comforting and familiar is also a reminder of his precarious existence. The excitement and freedom that Léo’s phantom affords him cannot but be tinged with a sense of sadness when we remember what makes possible its existence. Ultimately though, Léo takes pride in his “secret powers”, his phantom excursions as much about exploring this new access to his reality as they are about “escaping” day-to-day life in the hospital. In this way, Phantom Boy takes the traditional notion of the phantom and infuses it with a different sense of strangeness, melancholy and wonder. No longer that which is simply frightening, the film uses the notion of phantom as apparition to play with the boundaries between body and spirit, the embodied and the spectral, filtered through the eyes of an adventurous, imaginative child. “My name is Léo. I’m 11 years old, and I have a secret. I am a hero.”

Essay

©2015 - Folimage / Lunanime / France 3 Cinéma / Rhône-Alpes Cinéma

27 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

©2015 - Folimage / Lunanime / France 3 Cinéma / Rhône-Alpes Cinéma

28 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Work In Progress

Work In Progress

Into the realm of the Forgotten Forest The inspiration that led to creating a new animated series pilot with Cartoon Network Interview by JoyNoël Elett

M

adelein Treviño is a graphic designer and illustrator. She recently won the Girl Power: Pitch Me The Future award at Mexico’s Pixelatl Festival for her short “El Bosque Olvidado (Forgotten Forest)”, which is now becoming a pilot for Cartoon Network.

Tell us about the woman behind “Forgotten Forest”. I was born and currently live in Monterrey, Mexico. The first memory I have is of drawing; I feel it is the clearest way I can say something. My parents tell me that when I was in kindergarten I sold my drawings for 1 peso to buy tacos. I always put my heart and soul into the things that I do, no matter the project, just for the simple fact that I like to do what I do. What inspired the storyline of “Forgotten Forest”? My mom, Martha, is a very important part of this, even Marty's name is based on hers. She has more courage than anyone I know, and she has always encouraged me to live life fully and to enjoy it completely. I seek to create characters who are not afraid to explore and to be themselves, and I feel I identify with Marty. The different ways in which we see the world is what makes life wonderful; we can make any situation an adventure.

29 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

“Forgotten Forest” follows the adventures of Marty, a girl lost in a forest of strange creatures, as she searches for her grandmother. Along her journey she meets fantastic characters, such as King Raccoon and a jazz-loving wolf.

30 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Work In Progress

Work In Progress

“ Jazz can make me feel very melancholic or completely happy, two important sensations for the series.”

How did it feel to win Cartoon Network’s coveted award? When I arrived at the festival I felt like the new girl. In general I am a very quiet person, but I am not shy, so if you give me an opportunity to talk, I will happily take it. Winning was an enormous satisfaction, the simple fact that they heard me is something I appreciate.

Girl Power: Pitch Me The Future award was created in 2018 by Cartoon Network Latin America and Mexican animation festival Pixelatl as part of their ongoing award partnership. This year Cartoon Network looked for new and innovative voices, specifically in the under-represented female creatives community. Girl Power: Pitch Me the Future was an opportunity for female animators and creators in Latin America to bring their unique show ideas to Cartoon Network Latin America. To be considered for the award, the project must fit into Cartoon Network’s editorial values, must be an original idea, and communicate humour and authenticity.

31 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Marty is guided by a jazz-loving spirit. What emotions behind the music made you choose jazz in particular? Jazz can make me feel very melancholic or completely happy, two important sensations for the series. It serves to add personality and mystery to the character of a very solitary wolf. Some of the characters represent an internal part of Marty or speak of what surrounds her. For example, those little voices that follow her all the time and say no to everything, or the Raccoon King who can sniff out easily forgotten things that still retain great value. I think we all imagine our life with a soundtrack, so I would like to experience creating the Marty soundtrack. We may be listening to happy sounds and suddenly jump to something more melancholic, including complete songs (whether original or classic).

Project

Tropes and themes of folklore in Japanese animation Case study: A Letter to Momo Text by Sophie Monks Kaufman With thanks to anime expert Michael Leader for acting as consultant on this piece

A

nime is so popular that attempting to pin the form down to sweeping tropes is a bold undertaking that is well above this writer's pay-grade. Instead of macro, we're going micro by looking to this one 2011 title. A Letter To Momo, directed by Okiura Hiroyuki and made by studio Production I.G concerns an 11-year-old girl who moves to an island with her mother after her father dies. Colourful hijinks ensue after three havoc-causing yokai spirits, visible (almost) only to Momo, arrive. Despite this, the story remains anchored by the emotional undercurrent of a child learning how to grieve for an absent parent while relearning how to love the present one.

32 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Here are four elements of this beautiful and entertaining movie which speak to the wider phenomenon of folklore-driven Japanese animated works: 1. The mischievous yokai Yokai are supernatural beings that flourished within folktales during the Edo period (1603-1868), but originated much earlier — references date back to the first century. They are often shape-shifting spirits who manifest in the human realm via seemingly inexplicable happenings. Momo is spooked by strange sights and sounds — a shadowy figure boarding a busboat with her mother, distant voices, missing food — until the divinely weird-looking figures of Iwa, Kawa and Mame reveal themselves to the young girl. While incurably mischievous, this trio are well-intentioned guardians sent from “Above” by her father to watch over Momo and her mother. The fact that these creepy cuties are an elusive blend of vice and virtue makes them beguiling, especially when they dress up and dance! 2. A child dealing with adult tragedy Big weights on small shoulders are a common motif in similarly folklore-inspired anime films such as Spirited Away (2001), in which Chihiro has to save her parents after they are turned into pigs, as well as the tearjerker Grave of the Fireflies (1988),

which features young Seita’s attempts to keep his little sister alive as American fire bombs fall. Momo’s burdens, on the other hand, are more emotional rather than practical, but real and trying all the same. She is haunted by regret that she argued with her father before he died and swings between embodying a passionate, problem-solving nature and a grief that cannot be fixed. Initially she misses the signs that her workaholic mother, too, is consumed by sorrow. Momo's dealings with the yokai provide her with company as she works through volatile feelings and comes to see what she still has in the form of her mother. 3. Art that portends the supernatural Often, a spirit's arrival is foreshadowed by its depiction in a work of art that the young hero stumbles across. Early on in A Letter to Momo, Momo finds an illustrated storybook from the Edo period that contains black and white drawings of the grotesque figures who, little does she know, will imminently become her companions! Once they arrive in full garish colour, acting more like clowns that mythological deities, this historical anchor helps to lend their presence a sense of ancient gravitas. 4. The magical possibilities of nature A dichotomy between metropolis and countryside runs through Japanese culture. A Letter To Momo begins with Momo and her mother relocating from Tokyo to the quiet island of Shio via boat, retreating in grief to a natural haven where they can lick their wounds. Instantly, the magical possibilities of this new world are evidenced as the yokai descend from the sky in the form of drops of water. Water as an elemental home for yokai is also seen in Yuasa Masaaki’s Lu Over The Wall (2017), which features an exuberant mermaid-like yokai who drastically changes the life of an unhappy boy. In Momo’s case, supernatural elements entertain as they complement the realistic subject of a bereaved girl trying to settle into a new location, with new people and a new ambience. The island is a site for both spirits and spiritual regeneration.

Project

Š 2012 "A Letter to Momo" Film Partners

33 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Š 2012 "A Letter to Momo" Film Partners

34 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Interview

Reruns ŠAutour de Minuit

Interview

Rosto

Somewhere between waking and sleeping Interview by Ben Mitchell

What prompted the branching off of the Thee Wreckers Tetralogy from the original Mind My Gap series? I was wondering how I could introduce my music to an audience so I decided to make my own Fantasia where, instead of animating classical pieces, I'd visualise my own songs. That was the start of the tetralogy in 2008 and now I've finished it with “Reruns”. Do you have a specific process to capture that dreamlike quality when you're developing the look of the films? Originally I planned to shoot it with underwater puppets in an aquarium while still working with things like digital facial replacement. To keep a very sad and long story short, the tests were disappointing, so we had three weeks to come up with a new plan. That's how “Reruns”, the way it is now, was born — out of necessity. Of course I loved to see these different techniques come together and create an even more “lucid dream” effect. We did shoot some live-action — three characters are shot completely dry-for-wet, shooting three times as fast, using wires or moving on a ramp, to achieve watery movements. Actually I wanted it to seem like very thick air, exactly the way how it is in my dreams.

How do you go about achieving the digital facial animation we often see in your work? I've been working with head replacements for as long as I can remember, but it always returns in my films slightly differently to how it's been done before. In “Splintertime” we worked with projection techniques where the actors were wearing these prosthetic masks that were tracked and traced and flattened again, digitally, then given to animators who would put facial expressions onto them. So you keep all the real, live qualities of the masks — reflections, specular light, shadows — but at the same time the shape in a 3D space is being animated. For “Reruns” we had silicone heads made of the characters, scale models that were again tracked and replaced with digital, animated faces. This was a little easier to do because the silicone heads were cast from 3D prints of the digital models, so the match was perfect. In the past that was always a bit of a problem. Your subject matter in general has always been hypnagogic, sort of between being awake and being asleep. For me “Reruns” particularly resonated because of my own recurring dreams of being back in school. In a way “Reruns” is my most autobiographical film because all these dreams are true. I had to make a selection of dreams — especially ones that are connected to memory, because most of our dreams are, but some in such an oblique way that they aren't recognisable. The interesting thing is that as I get older they become more mundane and based on anxiety — exam anxiety, performance anxiety. It's strange, because I don't consider myself an anxious person — apparently I have some deeper angst going on!

35 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

D

utch artist Rosto has spent the past twenty years spinning his music and art into the elaborate online mixed-media graphic novel project Mind My Gap, culminating in the Thee Wreckers Tetralogy (“No Place Like Home”, “Lonely Bones”, “Splintertime” and this year's “Reruns”, which won the VFX Prize at Clermont-Ferrand), four films centred around a supernatural band that occupy a dreamlike, limbo space.

Essay

Broken screws and dusty puppet eyes Mise-en-scène in the Quay Brothers Text by Timothy David Orme

W

hen one sees a Wes Anderson composition or a sweeping Goddard sequence of jump cuts, they are expecting a certain style. This feeling goes beyond directorship and into authorship when we experience something from the Quay Brothers. This largely happens because the Quay Brothers are able to grow the mise-enscène of the film into something that simultaneously is itself and something larger than itself. They are able to expand the frame beyond its edges, and expand its sensations beyond that of sight and sound. To put it simply, when one sees and hears a Quay Brothers film, they know it because they feel as though they can taste, touch, and even smell it.

36 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

The Quay Brothers are, perhaps to an extreme few other animators parallel, austere auteurs. The images in their films aren’t traditionally beautiful. They are desaturated and drenched in dust. They stink of mothballs. And let’s be honest, even if we can taste the images in these frames, they’re not delicious. Beauty here lies in imperfection, and everything in the films points the viewers towards that understanding of beauty. The clean and colourful stop-motion set is replaced with a precise barrenness: aged metallic tools are covered in dust to such a degree that while animating “Streets of Crocodiles” (1986), the animators had to animate the movement and then pause for the dust to settle before capturing the image. A Quay Brothers image is not only seen but also inhaled. Characters in these films are often unfinished and move with imperfect, jerky movements, which is all their bodies are capable of. These asymmetrical bodies remind viewers of their own aching knees and sloping shoulders. A character moving across the screen is a dusty, visceral pain for the viewer. A grinding of textures like a grinding of bone.

Some of the characters themselves are not human, but instead the detritus of the film’s environment. It seems any object on the screen might be a discarded portion of a deceased character, might at any point either move as a character itself, or might morph into a portion of another character. Existence in these films is precarious and ever-evolving.

Watching the film, we come to realize anything could shift below us or around us at any point. We see space, but feel time. Camera movements themselves are almost too fast — re-enacting the struggle to comprehend space and the objects in the space as living or not. Sometimes the movement is so fast a viewer may realize they’ve moved, but not what land they traveled over in the moving. As in “The Epic of Gilgamesh”, or “This Unnamable Little Broom” (1985), some sets themselves aren’t finished. The horizon line is the abyss itself. Perhaps the characters are stranded. Perhaps this is their entire world. Either way, the unknown is hidden, but its view is in plain sight. A viewer could touch it if they could just find its edge. This unsettled sense of feeling that one cannot feel (or touch) is what exhilarates the viewer of these short, enigmatic films.

Essay

37 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Street of Crocodiles ©1986 Brothers Quay

Street of Crocodiles ©1986 Brothers Quay

Interview

Robert Morgan

An unceasing series of nightmare visions Interview by Ben Mitchell

S

top-motion nightmare-weaver Robert Morgan's macabre filmography includes the animated shorts “The Cat With Hands”, the BAFTA Cymru-winning “The Separation” and the BAFTA-nominated “Bobby Yeah”. More recently, he has been bringing his distinct style to feature films, animating segments for horror movies, and crafting the commissioned short “Belial's Dream”, an animated homage for the recently re-released cult classic Basket Case.

38 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

How did you get involved with The ABCs of Death 2? I was approached by [co-producer] Mitch Davis, who programs for Fantasia [International Film Festival in Montréal] where they show my stuff a lot. Each director is assigned a separate letter of the alphabet for their title, originally they gave me “L” and I came up with “L is for Louse”. After they compiled the films together alphabetically the running order didn't work, so they reshuffled it. They wanted my short to come nearer [to] the beginning, so I changed it to “D is for Deloused”. Although people associate me with horror, that film is probably the first film I've made so far where I explicitly set out to make a horror film. Now that you mention it, “Deloused” is more explicitly a kind of nightmare from beginning to end than your other work. I don't even start with any particular genre when I'm thinking of an idea, I just go with it — usually for me I'm laughing at them rather than feeling creeped out by them! To be honest, “Deloused” ended up being very funny to me as well. Do you know why your film is banned from the German release? I think there were three “letters” that were removed from the alphabet, which meant they couldn't call the film The ABCs of Death, because it didn't even have a letter “C“ in it! I think they ended up changing the title to 23 Ways to Die. It's always baffling to me when something gets banned,

I didn't think it was that bad. Because it's animation, it has a complete absurdity to it, a dream logic that is so removed from reality. I assume you were familiar with Basket Case before you made “Belial's Dream”? Oh yeah, I mean it happened because I was a fan of Basket Case. I had proclaimed my love of Belial many times and Ewan [Cant] from Arrow Films sent me a message asking if I wanted to do an animated homage that they could include with the re-release. It's probably the fastest film I've ever made, but that sort of spontaneity kind of goes with the grotty, low-budget aesthetic of Basket Case, to make something quick and be opportunistic about it. I didn't want to make a spoof or parody, I wanted to do something that felt like a proper Basket Case film, so the idea I had was to set the film inside of Belial's head — then animation sort of works for that purpose. Do you have stuff that's on the boil at the moment that is able to be talked about? I did some sequences for an American feature film called To Dust, where the main character is having a series of waking nightmares, visions. The film premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, it's a live-action drama and is very original. Now I'm in post-production for a little five-minute “pilot” for my own feature which I'm getting funding for.

39 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Interview

D is for Deloused ŠRobert Morgan

Studio

Text by David Hury

40 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

At LAIKA Studios, visuals are at the service of the story. LAIKA’s technicians and artists have mastered stop-motion and CGI integration, the sole mantra remaining: “The look is the rule.”

41 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Studio

ParaNorman ©2012 Courtesy, LAIKA

Studio

Kubo And The Two Strings ©2016 Courtesy, LAIKA

A

42 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

s black as the night sky. As dark as the bottom of the ocean. As thunderous as the rumbling of a Hells Angels horde. The wave in the opening scene of Kubo and the Two Strings is insuperable and unsparing. As he drifts in the middle of the night in a canoe, with his mother as his sole guardian angel, Kubo has a brush with death and drowning. The viewer is then directed from the danger of this tidal wave that is ready to swallow up these two characters to another danger – one even more terrible. The story takes a turn in a split second to Kubo's face. We meet Kubo as a baby with a missing eye and the narrator tell us that his own grandfather, the Moon King, has already stolen one eye and would like to snatch the other. It’s right there in the chilling category. The spectacular scene is short and impactful. One that called for a treasure trove of imagination from several technical teams working in parallel to introduce Kubo, a character conceived by Shannon Tindle. Travis Knight, LAIKA's CEO, asked Shannon to develop the protagonist in the genre of “epic fantasy drawing on Japanese culture”. For each of their films, LAIKA Studios commit to use, or even invent, new processes and to respect the story’s culture of origin. In this case, these are medieval Japan, the samurai Bushido, and the indispensable ukiyo-e, Japanese woodblocks, for the scenery. The opening scene of Kubo finds its visual roots in one of the most famous Japanese works: the famous The Great Wave Off Kanagawa by the painter Katsushika Hokusai (1830). LAIKA’s technicians transposed it to night-time using glass debris, paper, and fabrics to create the glistening water effect. The animators, led by Ollie Jones, worked long to find the right formula for the water’s movement, shape, and texture. Artistic director Alice Bird explains the process, which consists

of a mix of different animation techniques, both traditional and digital. “Ollie made a machine with ripped paper pieces that moved in a wave formation and showed off the shifting pattern of the torn edges, mimicking how water behaves but with real tactile material. That was an early inspiration. The final product, spearheaded by production designer Nelson Lowry, was created by embedding some of the woodblock textures that had come from the concept art into a digital model, with a huge amount of back and forth between the design team and CG water team to get it tuned to perfection. It’s definitely an example of how successful the blend of practical and digital art can be.” It is precisely this “blend” that LAIKA obsessively pursues. When leaving the screening, journalists made the common mistake of noting that Kubo was made entirely using CGI. This was not the case. Every second of the film in fact consists of 24 actual photographs. In an article in The Verge, Dan Pascall, Kubo's production manager, wondered why go through all this trouble, while expressing amusement at his own masochism: “God knows, there are easier ways to make movies, but we challenge ourselves to take ultra-detailed, time-intensive routes instead.” And oh, how long the route traveled since Coraline, LAIKA’s first feature film in 2009.

MASTERS OF HYBRID IMAGERY COMBINING STOP-MOTION AND CGI The impetus comes from the top. LAIKA’s chief insists on freedom for his artists so that they express themselves as much as possible. The CEO, Travis Knight, always repeats this in his interviews, as he did in 2016 in his interview with The Verge at the time of Kubo’s release. "The ethos of this whole place is that we are artists first and foremost.

Studio

˜ With the rapid prototyping, people are so interested in the technology, and sure, it’s really is. But, what is also really interesting is how we have adapted it to make it work for us creatively.˝

This passion for novelty and freedom begins, of course, with 3D printing, as ParaNorman director Chris Butler explains: “I think technical innovations (like 3D printing) have enabled the quality of what we put on screen to increase exponentially from movie to movie. I’m of the opinion that the final frame I see in the movie should be the best version of that frame, and I’ll use everything at my disposal to make it that way.” Whereas Coraline was the first feature film to industrialize the use of 3D printers, ParaNorman pushed it further. For the latter, LAIKA’s technical team conducted many tests, sometimes crossing their fingers not knowing what their programming results would look like for sure. But the results lived up to expectations. It was “like we were building the plane as we are flying it”, recalls the co-producer Arianne Sutner, quoted in an article in Animation World Network. “Part of stop-motion is the perfection in its beauty as well as the imperfections too”, Arianne explains, “so not everything in this movie is absolutely perfect in terms of the use of technology. But, that’s what I love about it.” Critics note that there is really a pre- and a post-ParaNorman when it comes to the use of technology. Alongside the 3D printer running at full capacity, more than 300 artists worked on details that are barely perceptible on the screen, but that are at the heart of the richness of ParaNorman. Yet, production costs did not

exceed the planned budget (60 million USD, just like Coraline three years earlier and The Boxtrolls two years later). Arianne remembers ParaNorman's creation process, and the team learning to use the new machines. “With the rapid prototyping, people are so interested in the technology, and sure, it’s really interesting. But, what is also really interesting is how we have adapted it to make it work for us creatively.” This need for technical skill in all departments and at each production stage rises to the challenges of animations “Made in LAIKA”. The impossible never stopped LAIKA. That said, there is no point in claiming victory too early. Each film brings new challenges. Kubo and the Two Strings, which was in production between 2013 and 2016, seemed particularly complicated to make into a film, especially for the transition from 2D to 3D. “The biggest challenge is translating the look of two-dimensional artwork into three-dimensional reality”, says Alice Bird, Kubo’s artistic director. “Because there’s so much interpretation involved, the art director has to get inside the designer and director’s heads, really develop an instinct for what they are imagining when they discuss a given set or scene. Sometimes the vision can be ambiguous even to the director, which can be a fun opportunity for the art director to input their own interpretation and show the way forward.” This “three-dimensional reality”, which is visually impressive in Kubo, marks the convergence of traditional stop-motion, frame-by-frame techniques, and computer-generated imagery. An often-tortuous convergence, as Alice explains. “We’ve actually developed a really good system for sharing the look across practical and digital assets. The art department will often build physical samples for the VFX team to keep and reference when they are texturing an asset. Even things like water

43 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

When we started LAIKA ten years ago, we could see the writing on the wall. Stop-motion animation was basically taking its last, dying breath. We had to come up with a way, if we wanted to continue to make a living in this medium that we loved, to bring it into a new era, to invigorate it." In the 13 years since its creation, LAIKA has always tried to push the boundaries of its own mode of expression, stop-motion, without ever renouncing it.

Studio

44 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Kubo and the Two Strings ©2016 Courtesy, LAIKA

Coraline ©2009 Courtesy, LAIKA

Studio

˜ ˜ w what hat is is out out of of the the frame frame is is as as important important as as what what we we see see on on the the screen: screen: the the viewer viewer must must be be part part of of the the show show and and feel feel that that he he could could go go anywhere anywhere in in the the picture.˝ picture.˝

KUBO: USING DÉCOR TO CREATE THE ATMOSPHERE In order to bring their stories and characters to life, LAIKA’s creative teams set for themselves the goal of creating never before seen sets. And this part of the process is thrilling and is also how LAIKA stands out from the competition. Whether it is in the thousand details of the city in The Boxtrolls, or in ParaNorman, the tones and the atmosphere are always painstakingly researched. For example, while Kubo was not the studio’s biggest box office success, it is nevertheless remarkable in its finish and in its wide-angle sets. The team relied on the Japanese identity of the story, for both small details and wider shots, while employing the woodblock effect of the renowned Japanese prints as the visual basis for the entire film design. In her book The Art of Kubo and the Two Strings (LAIKA Ed., 2016), Emily Haynes tells us about the influence of Japanese painter and printmaker Saito Kiyoshi’s work on the film’s mood and feel, light and translucence. Travis Knight, director of Kubo and the Two Strings and co-producer of ParaNorman, The Boxtrolls, and Kubo, captures it best: “Saito’s work is really bold. He uses simple colors and shapes. But within those shapes, he uses the texture of the wood to give dimension and nuance. This use of texture became a focal point for the film. There is something really interesting about him that is relevant to what we do here, beyond his artistic inspiration. At LAIKA, we have a fusion of old

and new, a sense of tradition and history mixed with innovation and modernity. We work on a medium that’s over one hundred years old, but we also bring a passion for cutting-edge technology and modern creative approaches. Saito did much the same thing. He was part of the ancient practice of Japanese woodblock printing, but he was very progressive. He synthesized and infused these divergent ideas into his own work. On every film we try to push beyond the edges of the form.” Production designer Nelson Lowry agrees and remembers the magical moment when the visual identity of the film was born: “We did a model of one of our sets and we painted a Saito texture on the top of it. It looked just like you would expect a traditional Japanese woodblock print. Everyone totally freaked out, and from that day on it’s been the look of the film.” At LAIKA, there’s a commitment to the look of films.

THE LOOK IS THE RULE During a tour of the studios reported by the site io9, Anthony Stacchi, co-director of The Boxtrolls, asserted this versatility that is so characteristic of LAIKA, halfway between different techniques, stop-motion, 3D printing, and CGI. “We are not purists”, Anthony Stacchi said, “the medium was less important that whatever delivers the look. The look is the rule.” LAIKA only relies on CGI to enhance scenes shot in stop-motion, and never the other way around. So much so that even an effect or an element is sometimes first made with physical materials to be later created digitally. For example, in The Boxtrolls, the mist and the clouds were initially designed in fabric to be later realized in VFX in post-production. LAIKA wanted to raise the bar even higher by staging complex group movements, like the ballroom scene. Stacchi explains the created effect that serves the viewer’s experience like in the open world of video games: “Some stop-motion movies, you feel like you’re trapped on the set. You can feel the edge of the set all the way through.” For Stacchi and his co-director Graham Annable’s camera, the hors-champs is as important as what we see on the screen: the viewer must be part of the show and feel that he could go anywhere in the picture. This was also the case for Kubo, for which LAIKA keenly worked on textures and elements with infinite patterns so that the viewer feels comfortable. “You don’t want the audience to really notice it”, art director Alice Bird explains. “You want it to be something that they sense. The same patterns that we used on the road surface in the village might appear

45 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

or smoke will usually go through a physical material exploration so that the VFX team have a starting point that isn’t just mimicking reality. Of course, that doesn’t mean it’s easy! One of the hardest things is probably dealing with really big landscapes – when we design a set and make a small-scale model, we will try to show the contours of the surrounding landscape for VFX, but it always needs more refining when we see it in shots. So there’s a whole stage of working with the digital team to dial in the shapes and textures, with the director of photography and production designer helping guide lighting to get the set extension to feel as real as the physical set.” The teams’ sole objective is for the images to dazzle, for the look to be perfect and for the animation of the characters to be up to the mark. As Alice put it, “to be sure that animation is supporting the story.” It’s always the story that dictates the rhythm, with the visual elements only there in a supporting role. At the little factory of the great thrill, the sets too are particularly important to the visual identity of the projects and to the success of the final shots.

Studio

The Boxtrolls ©2014 Courtesy, LAIKA

embedded on the surface of the water in the Long Lake. This design is not something that folks will look at, and say ‘Aha! I’ve seen that before!’ But hopefully it will unify the film in a subliminal way, give it all the same voice.”

46 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

But everything might not be so easy once the graphic identity is coherent and correct. “We spend months working on look development – experimenting with materials, surfaces, color, texture and shapes to capture the feel of the concept art”, Alice continues. “Then it was my job to figure out how to incorporate that in to each of the sets we produce, and guide all the artists in understanding it so well that they forget how to work any other way. At LAIKA, the art department is responsible designing and building all the sets, props, and graphics based on concept art from the production designer and their team. The production designer works with the director and director of photography to figure out ambience and lighting, then when a set lands on the shooting floor we continue to collaborate with lighting to achieve the look and feel, tweaking paint and lighting as needed until we get it just right.” What worked for the first four films will probably apply to the next feature, Missing Link, due to be released in the spring of 2019. Chris Butler, screenwriter and director of this fifth LAIKA production, insists on the unique and central nature of the stop-motion technique. “All mediums have their own challenges. No animation is easy”, Chris affirms. “Having said that, I think one of the unique aspects of stop-motion is also one of its biggest challenges. A shot is essentially a one-of-a-kind performance. It’s much harder to tweak or change stop-motion animation after the fact, because it is a person manipulating a real object under real light on a real set. It’s almost performance art. Of course, you can go back and augment, or doctor the animation digitally, but for the most part it’s a singular performance. You have to know exactly what you want when you launch a shot, because a lot of the time, you get one chance.” It’s

out of the question to mess up during shooting, as corrections in post-productions are only minimal.

GIVING A SCARE Fright is constructed like a firework; you need powder, a wick, and a spark. The powder is the story. The better it is, the more spectacular the explosion will be. But for that, you need a spark and the wick. The spark is the created world, the first shudder that gets the viewer into a story. “It can be sound, lighting, or animation”, says Alice Bird, assistant art director for ParaNorman and The Boxtrolls, and art director for Kubo and the Two Strings. “When you add in lighting, animation and sound design you have all these other tools which can bring the audience in to our world without even noticing that the characters have crazy proportions or the trees are made of popcorn. So I think each department strives to balance fantasy with realism in different ways, and the magic of seeing it all come together in the final product tells you if we succeeded in striking that balance.” What do LAIKA Studios have in store for us now with Missing Link? At the time of going to print, LAIKA had only released one sibylline image of Mr. Link looking out from behind a tree and appearing to say “shhh” with his finger on his lips. Basically, we know nothing. And don’t count on Chris Butler to spill the beans. “As director, I wanted to make a different movie than my first (ParaNorman). I had played out my horror/zombie/John Hughes phase… now I wanted to touch on some of my other early influences… like Indiana Jones and Sherlock Holmes, and classic adventure movies, and big hairy stop-motion monsters, obviously. To that end I tried to do something aesthetically different. This is a bright, colorful, bold movie. A vibrant, kaleidoscopic travelogue. It’s more ambitious in its scope and scale than anything we’ve attempted before!” So we have to wait till next April to find out if the new production – an Indiana-Jones-style adventure – is a winning recipe.

Studio

4 questions to

Alice Bird

What fears affect you? I was always fascinated by traditional fairy tales and the darkness that is at the heart of them. They contain so much horror: being eaten, being abandoned, physical transformations, ghoulish apparitions, magic, the cruelties of fate, ideas of justice and retribution. The way that, as a culture, we have historically used these kinds of stories to teach children about life and being human is equally awful and attractive to me. Even as an adult I have had visceral nightmares about the supernatural that seem to spring from childhood memories of these types of stories. So while I was definitely fearful of them, I also love how you can subvert the ideas in them to challenge conventions of say gender roles or what a happy ending means. That stuff has real power for me. What graphic influence were there for Kubo and the Two Strings? Woodblock printing techniques were probably the key theme in terms of what the Kubo look was. Where on other movies we had a heavy focus on the line quality as a way to inform our style, on Kubo, line was pretty much absent. It was all about texture. We wound up isolating a handful of textures from the concept art that we used as templates for paint and texture on both practical sets and digital assets, rescaled and repeated across everything from skies to tea cups. It meant every surface of every frame contained a tactile sense of the textured patterns you find in woodblock prints, and really gave a strong cohesive look across the show. How do you see LAIKA's future? I would say there are no companies such as LAIKA! Each animation studio is unique – LAIKA maybe especially so because we work in the niche world of stop-frame and because we are completely independent. As for the future, I hope we’re able to continue making unique films. Ultimately a movie is only as impactful as the story it tells, so I think our future success depends on finding exciting scripts that can speak to a range of audiences. I also harbor a secret wish for LAIKA to create short films, perhaps to screen ahead of our features. I think it would be a great way to start teasing out interesting concepts, as well as help develop studio talent. And that of animation cinema? I’m going to leave out the glaring answer of video games and VR because those aren’t of interest to me, although I realize that makes up the bulk of work going on in the field! As for other formats, I’m encouraged by a crop of bold and beautiful animated series that I’ve seen in recent years. Gorgeous, inventive kids TV-shows like Puffin Rock, Sarah & Duck, and Tumble Leaf are so refreshing in avoiding the usual goodies & baddies stuff that kids have been inundated with for years (and in my opinion are vaguely damaging in how they portray humanity and the world). And there are weird, hilarious shows like Big Mouth and BoJack Horseman that do things no other medium could. My hope for animated films is that we throw away the boring old Hollywood rule book about three act stories and predictable character arcs, and really embrace the weird and wonderful things you can do in animation.

47 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

©Courtesy, LAIKA

• Art Director for Kubo and the Two Strings (2016) • Assistant Art Director for ParaNorman (2012) and The Boxtrolls (2014) • Started her career as Assistant Art Director for Corpse Bride (2005)

(SOME)

AMAZING FACTS Studio

? a ik a L u o y e r a o h W

394 Employees (2015)

1.5

O t and CE Presiden t h ig n K is Trav creation place of Date and n, USA go 2005, Ore

million possible combinations, just for Norman's face

48 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

4.88m

high

+180kg For Kubo's skeleton model LAIKA's team had first bought an animated machine on eBay before building its own mechanism animated by a software worthy of the best flight simulators.

Coraline's shooting was done in a warehouse of 140,000m2 divided into

50 sets

The character of Hanzo's protégé (the beetle) is inspired by the actor Mifune Toshiroōwho often lent his features to Kurosawa Akira's films.

BUDGET / BOX OFFICE (USD) Studio

60 million

60 million

60 million

60 million

124.6 million

107.1 million

109.3 million

77.5 million

Coraline (2009)

ParaNorman (2012) Co-directed by Sam Fell, Chris Butler

The Boxtrolls (2014) Co-directed by Graham Annable, Anthony Stacchi

Kubo and the Two Strings (2016)

Directed by Henry Selick

For The Boxtrolls

Directed by Travis Knight

ANNIE AWARDS CORALINE - 2009 Bruno Coulais Music in an Animated Feature Production cameras (Canon 5D Mark II) were permanently mobilized for ParaNorman's production.

3D printing

is Used for the first time on a feature film for Coraline. On ParaNorman the use of the Polyjet 3D printer is Generalized and coupled with another printer, ZPrinter 650 (3D Systems), for colors.

4 sec.

of film is what 30 animators, on a team of 300 people, were each responsible per week for The Boxtrolls.

Shane Prigmore & Shannon Tindle Character Design in a Feature Production Christopher Appelhans & Uesugi Tadahiro Production Design in a Feature Production

PARANORMAN - 2012 Travis Knight Character Animation in a Feature Production Heidi Smith Character Design in an Animated Feature Production

THE BOXTROLLS - 2014 Ben Kingsley Voice Acting in a Feature Production

KUBO AND THE TWO STRINGS - 2016 Jan Maas Character Animation in a Feature Production Nelson Lowry, Trevor Dalmer, August Hall & Ean McNamara Production Design in an Animated Feature Production

49 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

were introduced in all the plans, for the characters or for the textures like the mist, the sparks.

Christopher Murrie Editorial in an Animated Feature Production

Studio

3 Things You Need For A

Good Feature: A Good Script A Good Script A Good Script 50 Marimo issue 002 - Phantasmagoria

Text by David Hury

Before creating beautiful imagery, you need, first and foremost, a good story. And a scary one at that. At LAIKA, storytelling is the cornerstone of each film. It dictates the technique used and often pushes it to its limits. LAIKA’s brainpower is its gold mine.

Studio

“How could you do this to us" cried out my eldest daughter, describing Coraline's alternative mother the way she appeared first on screen in her kitchen when she briskly turns around. “She has buttons where her eyes should be! You’re out of your mind, it's too horrifying!” The damage was done. I switched off the TV. I did not watch the movie. They both had nightmares that night. That's how I was introduced to LAIKA. Through vicarious fright.

A GOOD STORY: BETWEEN SCARY FAIRY AND SCOOBY-DOO For several years, Chris Butler has been the strongman of scary stories. It’s in his blood. He came into the world of animation by creating storyboards for Tarzan 2 (2005), Corpse Bride (2005), The Tale of Despereaux (2008), and Coraline (2009). His work in Burton's Corpse Bride was the spark. That’s when he decided he would do this for the rest of his life. Chris was 31. He then went on to write ParaNorman (2012), Kubo and the Two Strings (2012), and now Missing Link (2019). Chris knows how to build a story and dip into the fears of children, as he did in ParaNorman, where the characters of all the horror films from our childhoods (the glorious eighties) are gathered under green and pink lighting worthy of a good giallo movie. Butler talks

you still have to remember you’re making a film that will be primarily seen by kids. You’re not just trying to scare them. You’re trying to entertain them, and make them think and feel, and scares are just part of the mix.” In ParaNorman, Chris Butler wore two hats, that of screenwriter and co-director. Throughout the film, he worked with several co-producers, including Arianne Sutner. From the start, Arianne was certain that she had in her hands a solid story. In an interview with AWN.com, Arianne recalled: “I think it had a great script. The pacing was all there. We had a third act that worked, almost from the beginning, which is fairly unusual. We had a great hook, a really fun contemporary film, a nice fit to follow Coraline. I think also it just jived with Travis’ taste, kind of a contemporary Scooby-Doo movie. It could push the animation boundaries a little bit more.

˜ You’re trying to entertain kids, and make them think and feel, and scares are just part of the mix.˝

It’s July 2018. Nine years have passed. I live in Paris now. My youngest daughter, who’s now 15, brings up Coraline out of the blue. "Let's watch it!" I said. And right there and then, nine years after that November evening on my terrace and the scare of my two blondies, I realized what a bad father I had been then. How could I have done that? From the opening credits, Coraline was horror, pure and simple. Forsaken children, adults who are out-there, or, at best, lost in their own world. And then there is this parallel world, where everything is out of control. Where the great villain is much darker and terrifying than initially feared. But it's Coraline's story that strikes me.