Preface

O S L Triggs (CR, Philosophy and Religious Studies Department)

Look around, and you will find yourself completely immersed in games. Playing them has been a fundamental part of the human experience, and the emergence of games alongside the earliest civilisations only serves to underscore their importance. But their influence extends far beyond the recreational: established conventions (written and unwritten) inscribe norms and values that can be indicative of the people that maintain them; competition pushes people to ever-greater feats; and their appearance in various media or simple turns of phrase makes clear the way in which games are a universally-legible medium for self-expression. This makes them a wonderfully rich area of study, opening doors into the past with a fascinating diversity of disciplines and perspectives, while also casting a new light onto the games that make up our everyday experience and how they inform the way in which we choose to live our lives.

It was a conscious choice to explore the idea of Games in 2024. The Paris Olympics loom large, of course, but also there is application much closer to home. This year commemorates the 150th anniversary of the construction of the Marlborough Cricket Pavilion – designed by the great Victorian architect Alfred Waterhouse (of National History Museum fame) – and the publication encourages us to appreciate, as the title suggests, the limitless possibilities that studying and playing games can offer us.

Proudly following in the footsteps of publications like Marlborough Chalk, this project carries on a tradition of an expansive theme with multifarious applications. Over the course of the academic year, articles were released in small batches to highlight this – now, they can be found organised into loose groupings, each still fantastically diverse. Some have chosen to look at moments: the kick of a ball has been meticulously biomechanically analysed, or the result of a chess match has been seen as an inflection point for humanity and geopolitics. Others have taken a long view, trying to chart the history and evolution of games across time and space. Several authors sought to understand the impact that games have on us, from the harsh and palpable realities of brain injury to hypotheticals of what life would be like without games. Some highlight how games are an arena in which today’s contests – not only athletic, but political and social – are borne out, and others how they are a vehicle for alternative visions of (and sometimes warnings for) the world. Lastly, many contributions encourage us to think about the kinds of games that are less visible – whether they are found in language or in art that might question the nature of adult life.

This publication owes its existence first and foremost to Jackie Jordan, whose endless support has made possible the cohesive and accessible publication you see before you. There are also, of course, the contributions offered both by staff and pupils, who have taken full advantage of the almost infinite scope offered by the heading of “Games” and penned enthralling, nuanced articles that display a lively intellectual engagement across the Marlborough community. Thanks also to a host of Remove co-editors, but also Tali S and Ginny M for their work in compiling this publication. Finally, thanks are due to C A F Moule: his tireless commitment to enriching academic life at Marlborough has made projects like this possible, his encouragement and belief helping transform an idea mentioned in passing into the collection that follows.

We hope you enjoy a project which so many members of our community poured themselves into, and that it encourages you to look for the games that make up your life.

Ancient Egyptian Games

Daisy G (Re)

Games have been around for thousands of years and date back to ancient civilisation. They have always been an important part of cultures and one of the first forms of human interaction. They can include elements such as, sociability and bonding, education, competitiveness, escapism, and enjoyment. The human species is naturally equipped to play games because it requires and thrives from intellectual stimulation combined with a natural competitiveness which originates from the Darwinian theory of the ‘survival of the fittest.’

Whilst there is limited evidence of board games predating 3500 BC, it seems that the ancient Egyptians were undoubtedly early pioneers of game development. By the first dynasty, Ancient Egypt had become a settled agrarian society which inhabited the fertile Nile Valley and Delta. The conditions were perfect for various types of games to evolve. The society had long periods of stability, wealth (when crops were good) and there was an established hierarchy, including a sizeable standing army.

Senet was possibly the most popular game played during the Ancient Egyptian period. The earliest of these boards have been found dating from the Middle Kingdom (2000-1600 BC). We know the game was also known as ‘the game of passing through’ as it appears to have been based upon the important religious concept of achieving everlasting life by successfully journeying through the underworld. The most common boards were constructed of a pottery like material called faience, but, like with other aspects of Egyptian society, the richest classes obtained boards made of more expensive and rare materials such as ebony wood and ivory. Even though we have evidence of the boards (four were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb) we are not completely sure about the rules of the games. However, it would seem like it was a game based on chance, as are many games which were derived from the all-important religious beliefs, as this governed every aspect of Egyptian life in the Nile Delta.

Another popular board game found from Egypt around the Predynastic period around 3000 BC to the end of the Old Kingdom in 2300 BC was the board game called Mehen. Again, the rules are a mystery, however it would appear that the game is based around the snake god, Mehen. Whilst there is little evidence of it continuing to be played in the Middle Kingdom or beyond, later boards have been found in Cyprus therefore suggesting that the game was adopted by other cultures. Board games that we play today, for example backgammon and snakes and ladders, are not necessarily based upon religious beliefs and ideas, but still have elements of chance which makes the games enjoyable and competitive!

Throughout Egyptian paintings there are many scenes of boys and girls shown playing games outdoors as it was felt that it would lead to a healthy adult member of the community. Hieroglyphics have suggested that boys and girls did not typically play together, but boys were shown frequently wrestling, rowing, boxing, or playing competitive

team sports, for example field hockey. Girls were shown dancing and doing gymnastics. Both boys and girls were taught how to swim at an early age, which is hardly surprising given life revolved around the River Nile.

Similar to today’s children, young Ancient Egyptians enjoyed playing with toys, many of which were figures of women and men or animals made of clay or wood. These toys, represent many different aspects of Ancient Egyptian life and roles in society, ranging from soldiers with chariots, to women kneading dough. Playing with toys was a natural way of preparing these children for what was expected from them in later life. There were a number of toys excavated from the Tomb of Tutankhamun.

Physical pastimes were not only restricted to the young, but also played an important role in adult life. Much of the success of Ancient Egypt was dependent on the Pharoah maintaining a powerful standing army. Not only did the soldiers need to be fit and strong, but they also needed to be entertained and kept busy during long periods of peace.

Many of the activities reflected skills required in battle such as javelinthrowing, boxing, weightlifting, and running. Archery was also popular but was mostly associated with higher ranking officers and nobility, such as Amenhotep II (1425-1400 BCE), who was depicted being able to shoot through a solid copper target whilst mounted on a chariot. Sports were also popular with all levels of Egyptian civilian society, from the very top, the Pharoah, to the common people, who are seen in rowing competitions, playing handball and high jumping, which were performed in the same way they are today. The fitness of the Pharoah mirrored his ability to reign and reflected Egypt’s strength as the Pharoah was the gods’ representative on earth. His physical abilities were tested at the important Heb-Sed festival.

One team sport that we would probably recognise today, is the Egyptians’ version of field hockey which was played by two teams using palm branches cut with curved ends and with a ball made of a papyrus centre covered with cloth or animal hide. Many of these sports were enjoyed by spectators much as today when we watch sport on television or go to stadiums.

Egypt was undoubtedly an early and important contributor to a wide range of games, both sports and pastimes. Over 3000 years, it not only developed its own versions of games based upon its religion, social hierarchy, and its activities centred on the River Nile, but it also exported many on these ideas to other neighbouring ancient civilisations, such as the Assyrians, the Nubians, the Greeks and the Romans. We can see the everlasting popularity of many of these games today with many of these pastimes being multibillion pound industries in their own right, from the premier football league worth $13billion to the UK toy industry valued at £4.3billion in 2022. I wonder what the Ancient Egyptians would have thought of the latest AI games which are now being developed!

Games

Santiago F (Re)

Games have been played for thousands of years. Some played with friends, and others in front of thousands. In the ancient world, there were several games which were influential and valued greatly in societies, the most famous one being the Olympic Games. The other two games I will write about are the Gladiator games from Ancient Rome and Bullfights, originating in Spain. In this essay, we will explore how these games originated, influenced their society and still have influences today.

How long ago the Ancient Olympic Games started is quite unclear however the traditional date is 776 BC. The games were an athletic and religious festival held in honour of Zeus. The main events of the Games were made up of running, combat sports and the long jump. The Games brought together the different cities of Greece, creating a sense of unity and community. Before the Games, which took place every 4 years, there would be temporary truces between cities, something which allowed peaceful competition. The Games also promoted art and culture as well as trade because a great number of people from all over the Mediterranean came to watch. This benefited the cities that hosted the Games and contributed to their economy and cultural richness. These Games celebrated athletic ability and were a place for athletes to show off their capabilities and promote a society that valued health and athletic ability. Finally, the Olympic Games were festivals of religion. Sacrifices, rituals and gifts for the Gods were regular and winning athletes were viewed as heroes. The Games’ main impact on Greece was the cultural aspect. They created unity between the states and made an event that would be carried on thousands of years later. The modern Olympic Games are the biggest stage in the world for several sports and show how great of an impact the Games made.

Closely related to the Olympics, Gladiator fights were fought in Ancient Rome. Despite a vast number of records, the origins are unknown but are speculated to be of Etruscan descent. The first recorded fight was in 264 BC during the funeral of politician Junius Brutus and gradually became a more common event. They started off as religious and formal contests, however, they turned into forms of entertainment. Gladiators fought each other as well as wild animals. Lions, tigers, bears and elephants were brought to these events. Naumachia were naval battles that took

place in stadia like the Colosseum. They would flood the stadium and put in boats. These would seldom happen and were very expensive. Gladiator fights were also used politically. By making the fights gory and bloody, Roman leaders could show their power of life and death to potential rebels or criminals. They could also be used to gain popularity and followers. If the show was of a high quality, the person who organised it would be praised. This means they could have more power. The fights have led to modern sports like boxing, UFC and MMA, which all have traces of Gladiator fights.

Bullfighting, as well as the origins of Gladiator Fights, was for important political people. The first recorded bullfight was for the Coronation of King Alfonso VIII in the year 711 AD. It is speculated that bullfighting originated in the Mediterranean region from bull sacrifices. Bullfighting has a very important role in Spanish culture. It was for the rich, and celebrated religious festivals and weddings between royals and other important figures. Bullfights are very traditional and are viewed by many as an art. The matador, the man who fights the bull, is skilful and elegant in the way he moves. “Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter’s honour.”, said Ernest Hemingway, a very knowledgeable person on bullfighting who wrote several books on the topic. Bullfighting has also inspired artists and poetry. Hemingway’s most famous novel is The Sun Also Rises. Bullfighting, although it is facing great amounts of controversy, still brings in lots of tourism and is famous around the world. The tradition is dying as it is being banned in several Spanish regions.

To conclude, the Olympic Games, Gladiator fights and Bullfights are greater than simple games. They are embedded in the country’s history and are very traditional. They unified cities, celebrated athletic excellence and religion and undoubtedly had a long-lasting effect on their societies. Ours too are impacted. Bullfights still take place in some places in Spain, combat sports have descended from gladiator fights and the Modern Olympic Games is the greatest sporting event there is.

Traditional Chinese Games

Ollie F (Re)

China has a large range of fascinating history, such as the construction of the magnificent Great Wall of China, or the many dynasties, the first of which was 2070 BC, ruled by Xia Chao. However, in this essay I will explore the world of traditional Chinese games. Traditional Chinese games have served a huge role in shaping China’s culture, and it also gives us an insight on how people from China lived their lives up to 4,000 years ago. These games stretch back thousands of years and get passed down many generations. From strategic board games like Go, to physical activities like Jianzi, these games not only entertained, but also brought communities together.

One of the first Chinese board games is called Go or Weiqi in China and it involves two players. The objective of the game is to surround a larger total area of the board with one’s stones than the opponent. It is thought to have originated in China around 4,000 years ago and according to some sources it dates back as early as 2,356 BC. Traditionally it is played with 181 black and 180 white goishi (flat, round pieces called stones) on a 19 x 19 square wooden board (goban). In 2015, Demis Hassabis, Shane Legg, and Mustafa Suleyman (the founders of Deep Mind) tried creating a software that could play Go. It was called Alpha Go and it initially learned by watching 150,000 games played by human experts, then they created lots of copies of Alpha Go and got it to play itself over and over. Then in March 2016 they organised Alpha Go to play in a tournament and was pitted against Lee Sedol, a World Champion, and Alpha Go ended up beating him 4-1. They have now developed the game even more. Later versions of the software like Alpha Zero are capable of learning more about the game than the entirety of human experience could teach it.

Another example of a Traditional Chinese Game is Tai Chi, which is a physical game and the earliest known references to it date from the T’ang Dynasty (618-960 AD), where movement patterns were practiced by recluses who had retired to the Chinese mountain regions. Tai Chi is an internal Chinese martial art practiced for self-defence and health. It is also still widely used in Eastern Asian countries. Most modern styles of Tai Chi trace their development to the five traditional schools: Chen, Yang, Wu (Hao), Wu and Sun.

Many Chinese traditional games are social, such as Mahjong which bring people together, creating opportunities for social interaction. Mahjong is a tilebased game that is usually played with three players. More recently, the game is now widely played online and it is considered a gambling game. Mahjong is currently illegal to play in any unlicensed establishment in China if you’re betting money, apart from during Chinese New Year.

In conclusion, despite the rise of digital entertainment and globalisation, traditional Chinese games continue to hold a special place in modern society. They provide a means of preserving cultural heritage, promoting physical activity, and connecting generations. It is also important to preserve these traditional games and make sure these games are not lost to history. Some examples of efforts to protect these games are many festivals and events which celebrate traditional games and try to attract local and international attention. Many of these games have transcended national boundaries and there are enthusiasts worldwide. As we can see, many of these games have become electronic and people can play against each other from other sides of the world, which encourage more and more people to play. However, it is still important to play these games how they were traditionally played so we can still remember how people 4,000 years ago felt when they played these games and so we can bond with one another in person. It is vital that we continue to celebrate and cherish these traditional games as they evolve and make sure they are never forgotten.

That Drop Goal in 2003: A Biomechanical Analysis

James F (L6)

On the 22nd November 2003, in front of just under 82,000 fans in the Stadium Australia in Sydney, as well as up to 30 million more on television, Jonny Wilkinson gave Rugby fans one of the most iconic moments in the history of the game. Deep into extra time in the final, with just 26 seconds left on the clock, Wilkinson, in the iconic words of Ian Robinson, ‘drops for world cup glory’, the ball bisects the posts and England claim the Web Ellis trophy for the first and only time in history as of yet. This is seen by many as the greatest single kick there has ever been in the sport, and therefore I have decided to choose it in particular to analyse, looking into the biomechanics of the movement and how this unforgettable moment came about.

Biomechanics is the science associated with internal forces and mechanical laws relating to the movement or structure of living organisms. In this case of a sporting movement, I will be analysing the movement around joints, the actions of muscles to produce force and more to determine how Wilkinson was able to kick the ball in such a way that he did.

To begin with, Wilkinson’s drop goal was a sequential motion, composed of several different body segments interacting in a ‘proximal-to-distal sequential pattern’, or otherwise known as the kinematic sequence. This

pattern refers to the movement and orientation of a segment relative to adjacent segments, which falls within the principles of force summation, where in order to achieve the greatest distal speed (in this case the speed of Wilkinson’s boot), the order of movement must be from the most proximal segment to the most distal. For example, when throwing a tennis ball, your trunk moves first, then your upper arm, followed by your forearm and finally your wrist. This creates a motion similar to the cracking of a whip, allowing your hand to achieve a maximal distal velocity, which translates to how far you can throw the ball. Returning to the movement of Wilkinson’s drop goal, this proximal-to-distal pattern begins with the internal rotation of his trunk, followed by the flexion of his hip to bring his upper leg forwards, and lastly the extension of the quadriceps to accelerate his lower leg and foot to strike the ball. This sequence of movements allows Wilkinson’s boot to have a sufficient velocity that when it connects with the ball, it has enough momentum to transfer the force required for the ball to go over the posts.

To further analyse the biomechanics of Jonny Wilkinson’s famous drop goal, I have split the movement into four phases: The preparation phase, the kicking phase, ball contact phase and the follow through phase, each of which I will be explaining subsequently.

What I have labelled as the preparation phase is the time and movements from Wilkinson catching the ball to when his foot is at the top of his backswing. His shoulders are at an angle of approximately 45° to the posts, and as his hands close around the ball, Wilkinson simultaneously brings it down to about halfway up his femur, and transfers his body weight from his right foot to his left. He then takes one step forward to gather momentum, his left foot just now off the ground. From this point, Wilkinson pushes off his right foot and takes a relatively large step with his left, his quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior all bracing to absorb the impact with the ground. This step is larger than the ones before, as this generates more momentum for the kick, however, for this drop goal in particular, Wilkinson actually takes a smaller step than when he is place kicking, which can be seen in the comparison below between the angles of his leg in this particular drop goal, and a place kick for his club of Toulouse (the image on the left has been rotated so as to show the difference in angle better).

As can be seen in the two images above, Wilkinson took a smaller in-step to his drop goal than he would for a regular place kick resulting in a greater angle between the ground and his plant leg. This is because for the drop goal, he had to prioritise accuracy over distance to make the kick, and research conducted by Lees and Nolan (2002) showed that when an accuracy constraint is added into a kicker’s consideration, the length of the final step becomes shorter, resulting in a less acute angle with the ground. As he takes this final step, his anterior and medial deltoids contract, raising his arm. Then, his gluteus maximus contract as the agonist of the movement and the psoas and iliacus muscles relax as the antagonists of the movement, leading to hip extension, which brings back Wilkinson’s right leg to the top of his backswing and hence the end of the preparation phase.

As he raises his right leg, it gains gravitational potential energy, and this, along with force produced by muscles and the kinematic sequence allow Wilkinson’s boot to gain velocity as it descends. With his leg as high as possible, his Rectus abdominis and External oblique muscles would contract, resulting in trunk rotation in the

transverse plane, causing the angle between the line of his shoulders and the posts to decrease. Then, the psoas and iliacus muscles contract and his gluteus maximus relax, causing flexion at the ball and socket joint between his pelvis and his femur. As the velocity of his upper leg maximises, the antagonistic pair of the hamstrings and the quadriceps relax and contract respectively, resulting in extension about the knee joint. Finally, the muscles in his lower leg would contract isometrically, in order to brace for contact with the ball, where the kicking phase ends.

This initiates the ball contact phase, which happens over a timespan of milliseconds. During the kicking phase, Wilkinson’s boot has gained a significant amount of momentum, due to both the mass of it and predominantly the velocity with which it is moving. As it hits the ball, every muscle is braced, so that the time of contact is as small as possible because as the ball is struck, it will have a significant change in momentum. The equation Force = Change in momentum/Change in time explains that for the ball to be hit with maximal force, the time of the contact must be as short as possible, hence the muscles bracing to create as hard a surface as possible. As the boot and ball come into contact with each other, kinetic energy is transferred from the former to the latter, in the exact right spot for so that the direction to ball travels in is good, and it flies through the posts.

Finally, the kick finishes with the follow-through phase. As he kicks the ball, not all of the momentum in Wilkinson’s leg is transferred to the ball, and so it keeps swinging upwards, as in the photograph below. During this, the muscles in his left leg remain isometrically contracted, providing a strong base and preventing the momentum from causing him to fall over.

Jonny Wilkinson’s iconic drop goal in 2003 is a moment that won’t be forgotten for as long as the game goes on. It demonstrated a supreme blend of biomechanically precise movement and mental composure, all within the space of less than a second, and exhibits the combination of raw talent and meticulous preparation that is required for somebody to pull something like this off in such a high-pressured situation, especially when you consider that it was off his weak foot. This was the highest point in Wilkinson’s career and perhaps even in the history of English rugby, second only possibly to when William Webb Ellis himself picked up the football and ran with it, and the game itself was born.

The Origins of Hockey

Bella M (L6)

The roots of hockey are somewhat foggy, simply based on the fact that there are multiple historical records which detail games similar to that of modern hockey occurring in almost all ancient civilisations.

In Ancient Egypt, there is an image of two people playing with sticks and a ball in the Beni Hasan tomb of Khety, who was an administrator of Dynasty XI. Whereas in Ancient Greece there is a similar depiction (shown on the right) from 510BC, outlining figures playing an ancestral form of hockey or ground billiards. However, the contents of this ancient image are under controversy as researchers disagree over whether the characters are taking part in a team contest or a one-on-one activity.

Before 300BC in East Asia and Inner Mongolia, China, the Daur people had been playing beikou, a game using a carved wooden stick and ball. They had been playing this game for an estimated thousand years. In the same region, during the Ming Dynasty a field hockey variant called suigan was played from 1368-1644.

In Punjab state in India, an ancient form of field hockey was played throughout the 17th century. Around the same time period, palin/chueca was played by the indigenous Mapuche people in South America, more specifically in Chile. The Spanish Conquistadors, upon arrival in Chile, named the activity chueca as it resembled a Spanish game of that same name. It was once widely regarded that the Conquistadors introduced the game of chueca to the Mapuche tribe when they first conquered the region, however more recent studies outline that the Mapuche people had been playing palin for many years - due to the fact that it was often played for ritual purposes or in preparation for battle. During the 17th and 18th centuries, palin was banned by the Spanish colonial government of Chile, due to its tribal origins and connections. Once Chile gained independence in the 1800s, the game was revived. Palin/chueca is the only pre-Columbian Mapuche game which has survived into the present day.

In Northern Europe, mainly Iceland, since the early Middle Ages, the games of hurling and knattleikr (both stick and ball games) have been played. One of the earliest and most common recordings where hockey was recognised was under the proclamation by Edward III “Moreover we ordain that you prohibit under penalty of imprisonment all and sundry from such stone, wood and iron throwing: handball, football or hockey”

Modern hockey was formulated during the 19th century in public schools in England. It is now played internationally, taking the name field hockey - although mainly in Canada where they also have ice hockey. Similarly, in Sweden and Norway, the term land hockey is used.

The science behind swing, curl and other ball movements in the air

Archie D (Sh)

Pretty much everyone will have thrown or kicked a ball before, but why don’t they just fly straight? Within this article, I will discuss the differences between different sports and how it all works on a scientific level.

Cricket

Whilst there are many types of movement in cricket, such as wobble and drift, there is one main type in cricket, swing. Swing occurs when one side is rough and the other is “shiny’ (smooth). On the shiny side there is more of a smooth (laminar) flow as opposed to the rough side that has more of a chaotic (turbulent) flow of air. This means that the air on the smooth side has an earlier separation from the ball than that of the rough side, pushing the ball towards the rough side figure 1

Football

To understand how footballs curl we must first understand how power and energy is transferred from the foot to the ball. When we kick a ball, energy is transferred to the ball as velocity and spin. This means that the more you want to curl a ball, the less speed the ball will generate. The reason that balls curl has a name: the Magnus Effect. This describes how the ball spinning generates different pressures. It effectively states that the air flowing with the rotating side stays on the ball for longer than that flowing against it because of gravity. That then creates an area of high pressure and one of low, these pretty much push and pull respectively on the ball, making it curl. This is shown by the diagram figure 2.

Area of low pressure

Air that the ball is travelling into

The opposite happens on this side and this pushes the ball in the opposite direction

Friction causes the air to stick to the ball for longer

Movement of the ball This would mean that the ball would end up curling in this direction

Area of high pressure

Another movement in football is called “knuckle”. This is when the ball dips and moves unpredictably due to the ball not having any rotation. This is because when the air from the smooth surfaces between the seams hits the stitching it makes it a turbulent flow, causing unpredictable changes of movement in the ball’s trajectory.

Rugby

Whilst a rugby ball does not usually swing, there is some physics behind why we spin it the way we do. This is down to the law of conservation of angular momentum, which states that because the ball is spinning in one axis, it will resist spinning in any others. For example, a spinning top works because whilst it is spinning, it has angular momentum and because this is conserved, it will not move in any other direction (ie. it will not fall over). The same happens to a rugby ball, meaning that it will stay straight in the most predictable and aerodynamic way.

A History of Cricket at Marlborough

Mr M P L Bush (CR, History Department)

Marlborough College was founded in 1843 and for the first few years there was no expectation that any extracurricular activities would be provided by the staff. However, a few of the pupils were interested in cricket. They organised some internal games for their own interest, clubbing together to provide bats, balls, stumps etc. By 1849, the boys had begun levelling a ground and had formed a Cricket Club.

George Cotton, who arrived from Rugby School as Master in 1852, had worked under Dr Arnold while he famously reformed the school. Cotton introduced all of Arnold’s reforms to Marlborough, especially stressing the importance of sport. He insisted that to be eligible to play for a College team, boys had to practise at least three times a week. By 1855, when the first match between the two schools took place at Lord’s, the main cricket square at Marlborough had been completed. By 1860, the XI plateau had been fully leveled and a rustic pavilion had been built. This was replaced by the present pavilion in 1874 which was designed by Victorian architect Alfred Waterhouse, famous for designing the Natural History Museum and Manchester Town Hall.

For 117 years, the Marlborough/Rugby match was a regular fixture at Lord’s. Marlborough were thrashed by 10 wickets in the inaugural fixture and it was not until 1862 that they secured their first victory, winning by an innings and 17 runs. The last match at Lord’s against Rugby took place in 1972, with Marlborough winning by 6 wickets. Since then, the match has been played as a two-day fixture at both schools in alternate years. In August 2017, the two schools were invited back to Lord’s for Rugby’s 450th anniversary with Marlborough winning a thrilling contest by 25 runs. The fixture has been played 163 times. Of these Rugby have won 51 and Marlborough 46, including most recently in 2023.

Arguably the most famous old Marlburian cricketer is A.G. Steel. He captained England and played in the first ever Test Match in 1880, and his name features on the inscription upon the Ashes Urn. Other notable names include former President of the MCC Mike Griffith, who captained Sussex in the 1960s & 1970s and also played Hockey for England, and former BBC Test Match Special commentator and Times correspondent Christopher Martin-Jenkins, famously nicknamed ‘the voice of cricket.’ In addition, Leslie Gay (Somerset, Hampshire &

England), Arthur Hill (Hampshire & England) Frank Druce (Surrey & England), John Hartley (Sussex & England), Reggie Spooner (Lancashire & England), who also represented England at Rugby, Jake Seamer (Somerset), Richard Savage (Warwickshire), Ed Cunningham (Gloucestershire), Robbie Williams (Middlesex & Leicestershire) and Billy Mead (Kent) are among other OMs who have gone on to play first class cricket.

Girls Cricket was introduced in 2016 and soon afterwards the inaugural match against Bradfield was hosted. Marlborough won the first Girls fixture against Rugby by 8 wickets in 2018 and there was a mixed tour to South Africa in 2020. It has evolved rapidly and there are now 4 teams with a full set of fixtures. Cricket tours are a relatively recent phenomenon, with the first overseas tour to Zimbabwe taking place in 1999, followed by trips to South Africa in 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012 and 2020, and Barbados in 2017 and 2024.

Netball Carolina R (L6)

Netball. A sport which is enjoyed by only 20 million people around the world. That is 400 times less than the world’s population and just under 200 times less supported than football.

Netball is the sport that first comes to mind when I am asked what my favourite sport is. And on numerous occasions have people responded “Netball? What’s that?”. I try and explain to them that “it is like basketball, but you cannot run with the ball” and almost every time they look confused and by the sound of that one sentence, they assume it is a very boring, dull and ‘dead’ sport. I’m not going to explain the rules and regulations of the sport as that is, in fact, very dull, and I’m sure you can find a 5-minute video in just a couple of seconds which will summarise it perfectly. Instead, I want to explore the history and evolution of this sport.

When I reply with my now more or less automated sentence “it is like basketball, but you cannot run with the ball”, I do partially speak the truth. In 1895, a year after basketball was invented, a sports teacher, Clara Baer, in New Orleans wrote to James Naismith, the inventor of basketball, and asked for a copy of the rules of basketball. He sent over a package which included a drawing of the court with lines drawn in pencil all over it. These lines were there as a prompt to where various players should best be situated. However, Baer misinterpreted these lines and instead believed they signified where players were fixed and highlighted zones that some players could not enter. From then on, this idea was then implemented and classified as ‘women’s basketball’. This consisted of the court being divided into three zones and played by five players. When this reached Britain, in the end, the threebounce dribbling idea simply ceased to exist. Further, when this was first taught in England in 1897, an American teacher decided to replace the basketball hoops with basic netted rings without backboards. This equipment and slight change in rules gave the sport a new name of netball. The court is still divided into three parts however is now played by seven people, not five.

As many of you will know, Australia’s most common girls’ sport is indeed netball. It was introduced to Australian women in the late 1980s and was first played in schools around Melbourne. It was initially played indoors, but soon after outdoor matches were also played. The games early growth was mainly due to the reason of easy construction of the courts, which were also not costly to maintain. From the start, netball was developed and progressed without male association: men were denied participation not only as players, but also as coaches and umpires. No one knows exactly why men were not allowed to take part in this game initially, however, some argue this has actually benefited its success. It was separated from any similarities that other men’s sport shared, making a name for itself and it did not pose any threats to men’s sporting domains or was never heavily overlooked.

Overall, netball is now a very popular sport across New Zealand, Australia, England and Jamaica and is now fortunately open to both male and female participation. Even though, I will most definitely still have to explain the sport when I do get asked that question sometime in the near future, it is certainly on the rise, with an encouraging 15% increase in memberships in just the past year.

Kasparov vs. the World

Imp P (Sh)

10120: The magnitude of this number surpasses the number of atoms in the observable universe. This number represents the staggering number of possible games in chess. It is calculated by Claude Shannon, an American Mathematician. Through these calculations, it was determined that a typical game would run roughly 40 moves and include an average of 103 possible moves for a pair of games that consisted of a move for White and a move for Black. Therefore, it was concluded that there are approximately 10120 possible games of chess. To put this into perspective after only just 4 moves there are already over 288 billion different possible positions, nearly triple the number of stars in the Milky Way galaxy. Within one of these endless options, a legendary game was played between Gary Kasparov and the World.

Gary Kasparov was a dominant chess player in the 1980s and 1990s. He was the World Chess Champion and regarded by many as the greatest chess player of all time. His aggressive playing style and strategic thinking made him a unique player. In this special match, instead of facing against a single Grand Master, he was up against more than 50,000 people from over 75 countries.

The game was played in 1999 over the internet. It was a consultation game, in which the World Team, consisting of thousands of chess players, including several Grand Masters, deciding the move of the black piece operating by plurality vote, while the white piece was only controlled by Gary Kasparov. This made it a truly global event, with chess enthusiasts across the globe sharing ideas and strategies against Kasparov.

The game proceeded move by move, with the world community discussing and deciding the best move possible against the unstoppable Gary Kasparov. The pace of the game was set to 12 hours for Kasparov to analyse and move, 12 hours for the analysts to see the move and write recommendations, 18 hours for the World Team to vote and discuss, and 6 hours to validate voting.

Despite the collective effort of the whole world, Gary Kasparov won on move 62 after what was a long and harsh 4 months of battle. Due to his deep understanding of and strategic thinking for the game, he was able to defeat the World. However, he commended them as a formidable opponent. Kasparov wrote that he had never expended as much effort on any other game in his life and later said, ‘It is the greatest game in the history of chess’.

Finally, through the immense and vast amount of information gathered through this single game of chess, it revolutionised and played a substantial role in advancing the popularity and the accessibility of chess. The match helped popularise online chess as a serious platform for competitive play. It demonstrated that high-level games could be played over the internet, paving the way for the growth of online chess communities and platform. Most importantly, the match is remembered as a landmark in the history of chess.

Monopoly

Lily I (Re)

Monopoly is todays third most bought and used board game with over 275 million sold. This has been done because of all the different themes and languages it has been adapted for to appeal to people’s different tastes. At the moment one can buy monopoly in over 100 countries.

Monopoly is known as a game of capitalism. It is known as the illustrated example because of the players competing to gather wealth and property. It continues and reaches extreme measures and exaggerates this as there is a large juxtaposition between the wealthy player and the player who is barely surviving with no money. At the same time, there are some aspects of Monopoly not being based on capitalism. For example, how the bank owns everything, everyone is given the same amount of money to start off with and the dice determines where one goes which doesn’t apply for us as we determine where we go.

Monopoly wasn’t sold in every country. Back then, the Soviet Union believed it promoted capitalist values. It also wasn’t being sold there back then. China also didn’t allow it as they believed it was going in the other direction to the communist ideals China wanted. Although today there are some available to buy and play today. Cuba also had the same views as these countries despite being small and not very powerful.

Monopoly was created in 1903 by an American woman called Lizzie Magie. She was anti-monopoly. Monopoly in economics is when a market structure is made up by one seller. It creates a wall for new sellers not allowing them to even compete making it unfair to them. She believed that the game would show exactly why people should support her belief. Back then Magie created two sets of rules one anti-monopolist (all were rewarded when money was made) and one monopolist (to create monopolies to crush opponents). This was also created in order for people to compare and figure out the differences and the negative impacts. There were many versions but each involved the process of buying land. Houses were added later on to create the cost of rent and increase the damage for the players who did not own as much land. Magie named the game The Landlord’s game.

In 1932, a man named Charles Darrow came to visit and play Magie’s game. He decided to distribute the game calling it by himself Monopoly instead of The Landlord’s game. The Parker Brothers bought it off Charles not knowing it was still under possession of Magie. As soon as they found out they paid her for what she owned. The Parker Brothers started distributing the game across the globe. In fact, the British had a Monopoly customised for World War II which contained maps and compasses that distracted many as it looked like it was part of the game. In the 1970’s, there was a case of a professor trying to copy Monopoly whilst the parent company of the Parker Brothers, Hasbro, still continued to hold ownership for the game. Hasbro today still owns Monopoly starting out with two versions to now having multiple different themes and versions for many Monopolies which is a reason why it is so popular today.

In conclusion, Monopoly is not just a board game that was created for entertainment. It is in the top 3 most played board games after chess and checkers. It is a way to educate people and also show them aspects of different problems.

The Power of Crosswords

Milly G (L6)

The crossword is a cognitively challenging word game where you are given clues and must write your answers in blank white squares both vertically and horizontally. It was originally invented on the 21st of December in 1913 by Arthur Wynne and was published in The New York World. Today it is played by many worldwide whether on a day-to-day basis or at major national crossword competitions. However, the power of crosswords is more than just a form of mediocre entertainment seen in the back of newspapers. Beyond its reputation as a game for the elderly, it wields fantastic cognitive benefits, enhances your learning, and provides a source of mental stability. The power of the crossword is not to be underestimated.

Firstly, crosswords challenge the brain. When given a set of clues your brain attempts to bring the information forward by making new connections. This increases your mental flexibility and mental agility. It requires astute thinking to complete a crossword and therefore the use of your brain. Ultimately the adage ‘practice makes perfect’ demonstrates what crosswords can do. The more you do them the more you will further develop your cognitive abilities. Cognitive abilities such as visual-spatial reasoning skills. These skills are essential for processing visual information and understanding the space the information takes up in our world. For instance, without basic or good visual-spatial reasoning skills, you wouldn’t be able to make your bed or tie shoelaces. Doing crosswords strengthens these fine skills. Another cognitive ability such as your memory can also benefit from doing the crossword. A study done by Columbia University showed that participants who played the crossword daily compared to participants who played video games daily had a far stronger memory and healthier brain scans. Essentially, puzzle-solving will lead to increased IQ, better thinking skills and increased mental agility.

Crosswords are also a fun way of learning. Teachers often use crosswords to strengthen their students’ learning of topics or concepts in lessons. They are easily customisable and encourage engagement in the classroom which encourages further learning. However, beyond lessons, crosswords provide other means of learning.

When doing a crossword, you are likely to be exposed to new or different words which increases your vocabulary. Learning more words means that you can improve your understanding of language, hence leading to much better communication skills with the people around you, allowing deeper connections to form. Crosswords can also encourage curiosity and curiosity is the road to growth and lifelong learning.

Aside from improving mental capabilities, learning crosswords can also provide a source of relief. It is a way of unwinding after a long day and relaxing. The focus you put into your crosswords means you stop focusing on your daily worries, so crosswords therefore promote relaxation and rest. In addition, crosswords can improve social bonds. The opportunity to compete, discuss or work together with friends and family strengthens those relationships. This in turn also provides mental relief as you focus on having fun. Crosswords are an impressive way of taking a muchneeded break in your day whilst simultaneously building your cognitive abilities.

In conclusion, crosswords may often be underestimated and seen as just a mere game but the reality is much more. Its influence stretches across all ages, all the while promoting a lifelong enthusiasm for learning. Crosswords hold almost as much power to your brain as an FDA-approved drug for increasing your memory does. The power of crosswords should not be underestimated as we move into the modern day of fast-paced technology. The crossword will always have a significant place amongst the games in our world.

The Maths of Monopoly

Ben A (L6)

In The Indisputable Existence of Santa Claus1 (2016), Hannah Fry and Thomas Oléran Evans discuss the mathematics behind how to win at Monopoly. They explain that “The key to success in Monopoly is noticing that not all properties are created equal”, and that, more specifically, knowing which sets give you a better return than others is the “ticket to board-game glory”. Fry goes further in her discussion with Matt Parker in Stand-up Maths2 where she compares her mathematically calculated values with Parker’s computer-generated statistics. She explains that by working from first principles and by modelling a matrix of the possible dice rolls and their respective movements, she could construct a Markov Chain to calculate the probability of being on any space on the board at any point in the game. Parker, by contrast, used Python to code a model and generated the results from a million games of play to formulate his probabilities. Although entirely different methods, the two discuss the similarities in their data, along with the pros and cons of each method. Whilst Parker’s coding method was more time-efficient, Fry responds by claiming that “it’s just nice to get your hands dirty with a bit of matrix multiplication”. Keen to develop a better understanding of matrices, to support my study of Further Maths, I explored Fry’s method, researching matrices and Markov Chains.

The author of Exploring Maths 3 defines a Markov Chain as a “system where [one can] move randomly between states and where [they] go next depends only on where [they] are now and not on where [they] have been”. He goes further to highlight the phenomenon that “Markov chains gradually forget where [one] started and converge to a Stationary Distribution”.

This can be explained with a simple example, see figure 1. There are two states (A and B), where there are different probabilities of transitioning from one state to another; A to B, A back to A, B to A and B to B. These can then be represented by a Transition Matrix (M) which shows the probabilities of going from one state to another:

If one starts at space A then in the first state, S0, there is a 100% probability of being at space A (1) and a 0% chance of being at space B (0).

This can be represented by what is known as a Row Vector: S0 = [1 0]

To calculate the probability of being at either space in the second state, S1, it is necessary to multiply the row vector, S0 , by the transition matrix, M, in order to find S1.

1 = S0 x M

1 = [1 0] x [ 0.4 0.6 ] = [0.4 0.6] 0.7 0.3

It is possible to then repeat this process to find S2, S3, etc. S2 = S1 x M

2 = [0.4 0.6] x [ 0.4 0.6 ] =[0.58 0.2] 0.7 0.3

Which can lead to formulating the equation:

+1 = Sn x M

Reading further, the Markov Chain above is described as Ergodic, meaning that because the system is irreducible, aperiodic and finite 4, it will eventually reach a stationary distribution of probabilities after enough transitions. This means that once this process is repeated, of multiplying the row vector by the transition matrix, one will end up reproducing the same or almost the same row vector.

For the example above, the point at which the stationary distribution is achieved is S19, and therefore after 19, 20, 21 or 22 transitions, the probability of being on A is always 7/13 (0.53846154) and the probability of being on B is 6/13 (0.46153846). These calculations can be done very quickly using the Matrix Multiplication tool or MMULT function in Microsoft Excel, see figure 2.

2

The graph also reinforces the construct of a stationary distribution.

S x M = S and moreover Sn+1 = Sn

While it is tempting here to suggest that M = 1, one should instead draw similarity to the Eigenvalue Equation as seen below:

Where I is a transition matrix, ω is a vector and λ is the eigenvalue.

Connecting these two equations, one can assume I is similar to M (both transition matrices) and ω is similar to S (both vectors). This simply leaves the eigenvalue λ, and since our equation has no equivalent, it is stated that the eigenvalue for the example is 1 or λ=1. This is, in fact, a characteristic of all Ergodic Markov chains, that they have an eigenvalue of 15.

1 www.youtube.com. (n.d.). The Mathematics of Winning Monopoly - YouTube. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubQXz5RBBtU [Accessed 24 Oct. 2023].

2 www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Which Monopoly Properties are the Best? | Understanding Markov Chains. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z9IS9ffadC8&list=PLGK1PxSwNR7W9PJGRx1w5CyCXRBSTXbPX&index=5 [Accessed 24 Oct. 2023].

3 www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Monopoly: The Mathematical Secret Behind Winning. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8FP8Owdt2WY&list=PLGK1PxSwNR7W9PJGRx1w5CyCXRBSTXbPX&index=3 [Accessed 25 Oct. 2023].

4 www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Eigenvectors and eigenvalues | Chapter 14, Essence of linear algebra. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PFDu9oVAE-g&list=PLGK1PxSwNR7W9PJGRx1w5CyCXRBSTXbPX&index=8 [Accessed 25 Oct. 2023].

Knowing all of this is important as it is useful in calculating the different probabilities of landing on particular properties on the Monopoly board. Recognising that a Monopoly board can also be modelled as an Ergodic Markov Chain, we can expand the simple example that consists of just two spaces, A and B, to a 40-spaceMonopoly board where all players begin at space 0 – Go. This means that the transition matrix goes from being 2 by 2 (having 4 values) to being 40 by 40 (having 1600 values).

If this game were simple, where a player could only move by rolling two six-sided dice and there were no other factors, then over time there would be an equal chance of landing on every square on the board, a probability of 1/40. When two six-sided dice are rolled, it is possible to obtain any number between 2 and 12 inclusive. However, the probability of rolling any of these 11 integers is not equal, due to the different possible ways to make each number. The most likely sum to roll is 7, as there are 6 different ways of making it with our given dice, and the least likely to roll are 2 and 12, as they only have one possible combination with our given dice. This is shown in figure 3.

So, the chances of rolling each sum are as follows:

figure 3

With that, and exploring the first roll of the game, this would suggest that the probabilities of landing on spaces between Go and the Electric Company are shown in figure 4.

figure 4

However, Monopoly is not quite that straightforward because there are two additional ways that a player can move around the board. These include moves through the Chance and Community Chest cards, cards drawn when a player lands on one of the three squares assigned to each category, and through the GO TO JAIL square, which sends players directly to Jail. I will consider each of these transitions and their respective probabilities in turn.

Chance and Community Chest cards

Both decks contain 16 cards each, meaning that if a player draws a Chance card, they have a 1/16 chance of drawing a specific card. There are 7 Chance cards out of the 16 that alter a player’s position on the board but only 3 Community Chest cards out of the 16 - the remaining cards simply contain monetary fines or benefits, exchanges or such as a fine or a birthday. These movements are summarised in figure 5

5

This means that if a player lands on a Chance space, they have a 7/16 chance of moving from that space and a 9/16 chance of staying on the space. Likewise, if a player lands on a Community Chest space, they have a 3/16 of moving and a 13/16 of staying on that space. Now the probabilities of ending a player’s roll onto all the Chance spaces in the transition matrix can be altered by multiplying each of our existing probabilities by 9/16. The same can be done for the Community Chest spaces by multiplying the existing probabilities by 13/16.

If a player is leaving a Chance or Community Chest space, this means that they have a 1/16 chance of going to any of the possible spaces that the cards can tell the player to move to. If a player lands on a Chance space, they have a 9/16 chance of staying on that space, a 1/16 chance of going to Marylebone Station, Trafalgar Square, Pall Mall, Mayfair, Go, GO TO JAIL, or another 1/16 chance of going back 3 spaces. The same case applies to Old Kent Road, Go and GO TO JAIL for the Community Chest cards. Therefore, the probabilities of going to these locations are altered. Taking this into account, figure 6 illustrates the actual statistical distribution of landing on the various possible spaces on a player’s first turn.

6

Go to Jail

When a player lands on the space GO TO JAIL, they are instantly transported to Jail. For example, if a player is on Fenchurch Street Station, they have a 1/9 chance of rolling a 5 to land on GO TO JAIL, but instead of ending their roll on the space GO TO JAIL, they end their space in Jail, so they have a 1/9 chance of going from Fenchurch Street Station to Jail. Since a player cannot end their roll on the GO TO JAIL space, all the probabilities of ending their roll there are 0, similarly, one therefore cannot begin a roll on GO TO JAIL either, meaning that all the probabilities of going to any space from GO TO JAIL are 0. However, as the total probability of leaving any space must equal 1 as a player must always move, I have chosen to show this as when one begins their roll on GO TO JAIL, they have a 100% chance (a chance of 1) of going to Jail.

Factoring these considerations into the transition matrix, π, it is possible to calculate the probability of being on any space, on any turn, throughout the game. As every player always begins the game on Go, the first row vector is a one followed by 39 zeros as there is a 100% chance of beginning every players’ first roll at space 1, Go

n0 = [1 0 0 0…0 0]

(This is one ‘1’ entry followed by 39 ‘0’ entries)

Taking the formula derived earlier and applying it to this Monopoly situation, one can produce this formula:

Using this expression, it is possible to calculate the stationary distribution by, once again, using the MMULT function on Microsoft Excel. This data is highlighted below, in figure 7

From this data, one can see that once the stationary distribution converges, the most likely space for a player to end their roll on is Jail, with approximately a 5.9% chance, so this is ranked #1. GO TO JAIL is the least likely space for a player to end up, with a 0% chance, so it is ranked #40. figure 7

This data can also be represented graphically, as in figure 8

Using the probabilities from the table on the left, figure 9, the average probability of landing on each colour set can be calculated. This is important as to build houses and increase rent levels, a player must own the entire set.

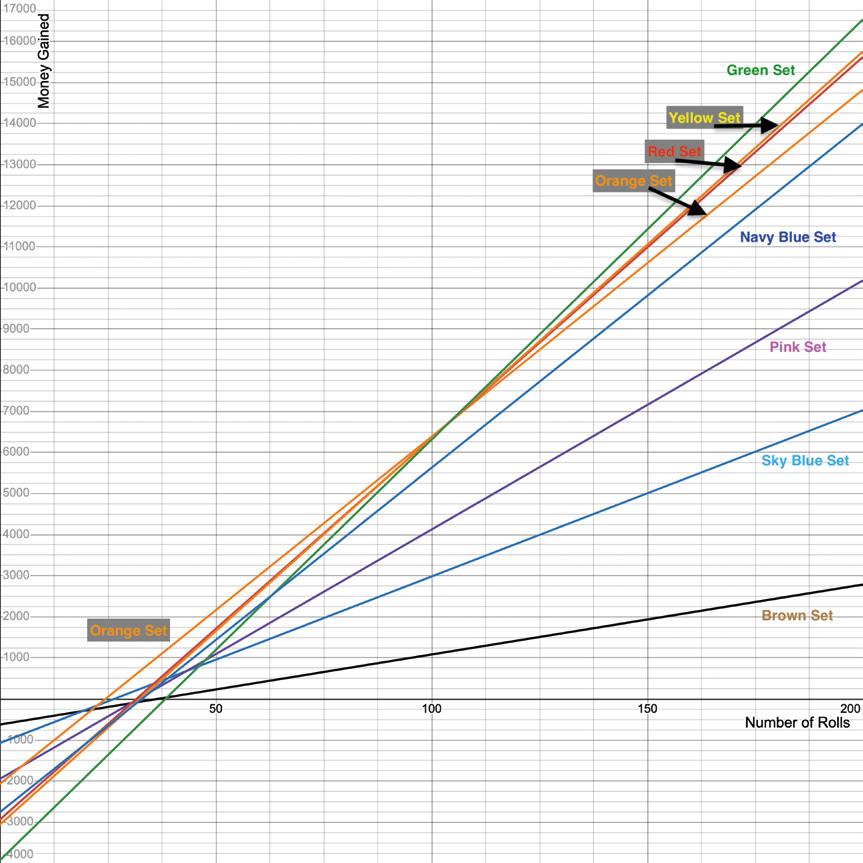

Figure 10, below, illustrates that the podium of property sets on which a player is most likely to land are the Orange set in first place, the Red set, second, and then the Yellow set. As the most landed on space is Jail, logically when a player rolls the dice to leave Jail, they will usually end up on the spaces 6, 7 or 8 spaces after Jail, as these are the most likely sums of rolling two six-sided dice. This suggests that the set on which any player is most likely to land is the Orange set.

Having calculated which sets are most landed on, one must now factor in respective Rent Levels and costs in order to determine the best set to own. What constitutes the best set is determined by how quickly a player can recoup their costs and begin to make a profit.

Figure 11 shows the Purchase Price of an entire set and an equal number of houses on each property. For example, it costs £2,150 to own all three Yellow properties and to buy three houses on each property. The utilities and the stations are in a separate table as their amount of rent increases with the more properties owned. No houses or hotels can be purchased on any of these 6 properties.

Figure 12 illustrates the Total Return given from each set when a player receives one share of rent from each property in that set. For example, if a player receives rent payment from Pall Mall with two houses, Whitehall with two houses and Northumberland Avenue with two houses, they will have collected £480.

Since the rent on the utilities relies on the roll produced to get there, this table shows the monetary values received on the basis that a 7 is rolled as this is the most likely dice roll.

By multiplying the Total Return values by the average probabilities of landing on these sets, one can see the average monetary Return per Roll. Obviously, a player won’t collect this money every turn, as that is not how the game works, but this data is useful as one can see which properties generate the most income over the course of the game. With that, figure 13., below, creates a picture of which sets will generate the greatest income. The most income per roll is generated by the Green set but this is also the most expensive set to purchase and raise hotels on.

From these data points, one can calculate the number of rolls required for a player to raise their money back so that they can begin to profit from their investment. This is calculated by dividing the Purchase Price by the Return per Roll. This is illustrated in figure 14.

These values clearly show that the properties with the Orange set will break even first and so should be a great investment, especially in a shorter game with fewer players. A short game constitutes fewer than 100 turns per player.

Going further, it is possible to plot the expected return from each set on a graph. This is shown below in figure 15.

Looking at this graph, one can see that the Orange set breaks even in the fewest number of rolls, crossing the x-axis at the lowest x-value. The Orange set remains the strongest investment for the first 103 rolls. However, from the 103rd rolls to the 105th rolls, the Yellow set takes the lead very briefly, before being surpassed by the Green set, which soars into the winning position of the most profitable set per roll beyond 106 rolls.

In conclusion, this graph indicates that the best strategy to win at Monopoly is to;

■ When playing against one opponent, secure and build up the Orange and Sky Blue sets, preferably both, and attempt to end the game in fewer than 40 rolls.

■ When playing against two or three opponents, secure and build up the Orange and Red sets, preferably both, and attempt to end the game in fewer than 100 rolls.

■ When playing against four or more opponents, secure and build up the Green and Yellow sets, preferably both. Here you should attempt to maintain liquidity beyond 105 rolls.

■ Remember also that the number of houses is limited, so when building your monopoly try to secure three houses as quickly as possible. This serves not only to increase the speed of your return but will also prevent the progress of your opponents.

■ Avoid the Utilities, they are completely pointless.

Bibliography

Hannah Fry. (n.d.). The Indisputable Existence of Santa Claus. [online] Available at: https://hannahfry.co.uk/book/the-indisputable-existence-of-santa-claus/ [Accessed 18 Oct. 2023].

www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Markov Chains Clearly Explained! Part - 1. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i3AkTO9HLXo&list=PLGK1PxSwNR7W9PJGRx1w5CyCXRBSTXbPX&index=3 [Accessed 25 Oct. 2023].

www.youtube.com. (n.d.). What’s the best way to win at Monopoly? [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BvuYH7ldfkg&list=PLGK1PxSwNR7W9PJGRx1w5CyCXRBSTXbPX&index=5 [Accessed 25 Oct. 2023].

www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Markov Chains & Transition Matrices. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1GKtfgwf3ig&list=PLGK1PxSwNR7W9PJGRx1w5CyCXRBSTXbPX&index=6 [Accessed 25 Oct. 2023].

www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Dominating Monopoly Using Markov Chains. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mh5r0a23TO4&list=PLGK1PxSwNR7W9PJGRx1w5CyCXRBSTXbPX&index=10 [Accessed 26 Oct. 2023].

www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Monte Carlo Simulation. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ESK5SaP-bc&list=PLGK1PxSwNR7W9PJGRx1w5CyCXRBSTXbPX&index=7 [Accessed 27 Oct. 2023].

The Applause

Elliot R (L6)

In 1917, Russia saw great change. Russia had abolished the monarchy and taken up a socialist government after two revolutions and a bloody civil war. After the revolution in February, Tsar Nicholas III agreed to step down to ease the tension and the Provisional Government was put in place. In October, the height of the Russian Revolution was reached with Vladimir Lenin’s far-left Bolshevik Party overthrowing the Provisional Government. They established their own government: the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). The revolutionary period continued up until 1923 with the Bolsheviks facing resistance from their enemies known as the White Army. Eventually, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was formed, and the Bolshevik Party would remain in power until 1991 when the Soviet Union was dissolved.

Communism is a far-left ideology in which all property is owned by the community, and everything is distributed “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”, which is a slogan made popular by Karl Marx in his 1875 Critique of the Gotha Programme. Critics of communism argue that communism has often led to totalitarian regimes such as the Soviet Union and various other dictatorships such as in China. They also claim that the system itself, even if it were successfully reached without totalitarianism, would go against our very human nature. Some would argue that due to the lack of material incentive, innovation may diminish, and society may collapse. Of course, communism has its responses to these criticisms, but I won’t discuss them here.

After World War II, the victorious sides emerged with contrasting ideologies; Great Britain and the US were capitalist whilst the USSR was communist. In 1947, the Truman Doctrine was created in order to stop the spread of communism worldwide as the US viewed it as a dangerous ideology and didn’t want the USSR’s power over Europe growing further. The conflicting ideologies led to major tensions between the world’s great powers and was one of the most significant factors in causing the Cold War.

During the Cold War in 1972, the World Chess Championship was played between Boris Spassky and Robert James Fischer in Reykjavík, Iceland. This match was a major event in the context of the Cold War, as the Soviets were particularly strong in chess. In fact, the Soviets dominated the chess world so much that the last 10 World Chess Championships had been won by Soviet players. This game was a metaphor for the tensions between the East and the West. This symbolism is reflected in the way Bobby Fischer describes chess: “Chess is a war over the board. The object is to crush the opponent’s mind”.

In the sixth game, Fischer opened with 1.c4 (instead of his usual 1.e4) for only the third time in a serious game. This led to a position that Fischer himself had criticised and described as an inferior position for white, so we can only speculate as to why he played this opening move. For many players, it may have been an attempt to gain a psychological advantage by throwing off the opponent, but this seems unlikely in Fischer’s case. He famously said, “I don’t believe in psychology, I believe in good moves”. The game then proceeded in a Queen’s Gambit Declined, Tartakower Defence where Bobby played a slower style of chess to how he normally played. Ironically, it was more in the spirit of a ‘Soviet’ player than Fischer. Spassky, on the other hand, made many mistakes until, what was a drawn position, ended up being a win for Fischer. And after this win, which put Fischer ahead in the match for the first time, Spassky stood up and joined in with the audience in giving Fischer a round of applause.

This game of chess is now one of the most famous in history. Why I find this so interesting, is because you can almost sense the historical tensions going on at the time by simply studying the moves of the chess game. From the very first move, it doesn’t feel like Bobby Fischer playing with the white pieces and Spassky as black isn’t playing with the precision which was typical of a ‘Soviet’ player. This demonstrates the impact of war on individuals. Whilst I am only speculating, I think it is sensible to assume that the cause of Fischer’s timidness and Spassky’s mistakes was the global politics interfering with the “war over the board”.

More importantly, Spassky’s applause at the end of the game was almost like the destruction of a barrier between the two nations. The beautiful game of chess allowed Spassky to see past the political tensions and congratulate his opponent on his good play. Fischer received this well and complemented Spassky on his sportsmanship. So, in times of political tension like today, remember this game of chess. See past the wars and hate and appreciate the beauty of the world, just as Spassky could appreciate the beauty of the game of chess, even in the face of defeat.

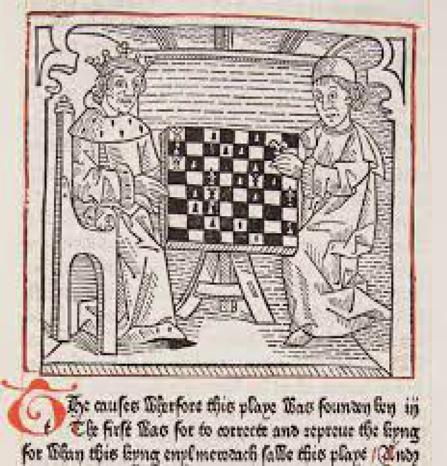

The Universality of Medieval Chess

Mr O S L Triggs (CR, Philosophy and Religious Studies Department)

In only the span of a few centuries, the game of chess grew out of its predecessor chaturanga in Northern India and was soon in the far reaches of northern Scotland, travelling along various circuits of exchange through the Middle East and Europe from roughly 600 C.E. to 1000 C.E.

Covering such vast distances during this period, known to some as the Global Middle Ages, is a feat unto itself, inviting us to imagine the veritable cultural sensation that chess must have been in the medieval world. Over the next five hundred years (up until, effectively, the Renaissance), the game of chess became a cultural touchstone across the medieval world. For some, it was a game of wits, for others, a game of kings, and for others still, a metaphor for society and its proper order. Learning the game was instrumental to a knight’s education, and it was one of the few pursuits available to women in the aristocratic court. Marital disputes over chess – namely, the husband spending too much of his time playing the game – survive in Genoese court documents, as do church edicts that lambast the game as an impious activity. Constantly reappearing in literary and material cultures of the past, chess becomes something of a chameleon: a vehicle through which contemporary people sought to make sense of the world and render it for others, and in so doing making it a fascinating source of study for scholars searching for a window onto the past. Exploring, too, the ways in which the game evolved as it encountered new cultural contexts illuminates the nature of exchange and assimilation in the premodern period.

Growing the Game and Crossing Cultures

It is important to highlight that during the time of chess’s intense spread across the world, there was no standardised ruleset – regional variations took hold, both materially (in the design of the pieces) and in the rules of the game, which highlights chess’s role as something of a newcomer: once introduced, it was adapted into more legible local forms.

Early historians of chess set out to chart these variations that resulted in the eventual ruleset with which we play today. They focus, most notably, on the evolution of what we now call the Queen. In the original game of chaturanga, the piece was called firz, meaning counsellor, just as what we call “Queen” is still called “wazïr” (or vizier) in Arabic. In the early versions of the game, then, there was no feminine piece: it was more of a king’s advisor or assistant. The differences do not end there – only (relatively) recently has the piece gained the immense power it now has. Originally, it could still move in any direction, but just one space, as the King does now. Scholars have speculated about the reasons for these changes, both in the name and the ability of the piece, and the prevailing argument suggests that the game originally was analogous to the battlefield, a wargame. As the game was assimilated into European monarchical traditions, it shed some of its warring connotations and became a representation for the European state (and, as we will see later, its proper hierarchy).

As mentioned previously, chess offers a fascinating window onto earlier cross-cultural contact and exchange, visible through one of Britain’s great national artifacts. The Lewis Chessmen, the majority of which are housed in the British Museum, are a collection of 93 chess pieces found on the Isle of Lewis, each carved with a unique individuality. What is particularly compelling about the Chessmen, though, is the way in which they recall Scandinavian iconography and style of pieces from the earlier Viking game of tafl. The elaborate ivory carvings enact a level of detail that is specific to the time and place of their creation

– the rook, pictured here on the far right, is thought to recall the Norse “berserker,” their teeth chomping at the bit to enter battle.

A 13th century Castilian illuminated manuscript offers further insight into the nature of assimilation and exchange, albeit in a very different context. The Libro del ajedrez was a spectacularly decorated book made for Alfonso X’s court in Castile, but what makes it particularly interesting is that its illustrations are chess puzzles, each of which are accompanied by drawings and commentary. The scenes are narrativised and portray a wide variety of people playing – men and women, Muslims, Christians, and Jews, children are all featured, sometimes asymmetrically, meaning that men might play women, Christians might play Muslims, and so on. Olivia Constable, who studies the Libro in her 2007 work, argues that the manuscript illustrates a new Iberian aesthetic. In the image here, the background will immediately be familiar to anyone who has visited the Iberian Peninsula and its characteristic arches. Constable writes that even the chess puzzles themselves are both Muslim and Christian in nature, as the two communities had identifiably different styles of play. Furthermore, some of the artistic elements throughout the book are highly suggestive of a strong Muslim influence if not creation, which is illustrative of a strong degree of interreligious interaction.

In these two examples – the Lewis Chessmen and the Libro del ajedrez – we can see not only chess’s universal appeal in the medieval world, but also how chess was incorporated into already-existing cultures of creation as well as being a vessel for new, cross-cultural aesthetics.

How to Live Your Life According to Chess

As chess spread throughout the medieval world and became entrenched in contemporary culture, it became a powerful literary device. Certain examples are not particularly subtle: the Stanzaic Guy of Warwick (c. 1300) features a tale in which a sultan visits the land of a prince, and challenges him to a friendly game of chess. Shortly thereafter, the game gets out of hand, and the Sultan uses a piece from the board to attack the prince, and the prince, angered, bludgeons the Sultan to death with the chessboard. An extreme example, but the ensuing division between the polities featured in the story (and their eventual reconciliation through, again, a game of chess) underlines how chess was “the game of kings” and in the foreground of political struggles. Jacques de Cessoles, and his De ludo saccorum, emphasise the proper ordering of society as it is seen on the chessboard: the king, of course, being of the utmost importance, and the other pieces taking on specific roles that reflects a) its duty to the king and b) its subordinate position and c) its importance to the smooth functioning of society. Taking this into account, certain chess moves, like “pinning,” where a piece cannot move for fear of leaving its King exposed to check, gain new symbolic value, and start sending us messages about how we (and society) should operate.

Finally, we have an example that is explicitly didactic, that is, intended to instruct us in some moral way. Le je des esches de la dame moralisée, coming from the late fifteenth century, recounts a game of chess being played between A Lady and The Devil. The story recounts move-by-move (!) the evolution of the game and each piece on the board (save one) is named, giving each of its movements a moral resonance. As you can see, the pieces are named with virtues and sins in mind – the Lady playing with pieces like Honesty and Loyalty, and the Devil using Ambition and Blasphemy. The game ends with the Lady checking the Devil’s King (Pride) with her Queen (Humility) and eventually check-mating with her pawn (Love of God). For readers, the message of how to live as a good Christian could not be clearer – the author is furnishing them with specific instructions on how to live well and avoid sin.

Conclusion

The medieval world of chess makes clear just how much is at stake when we play games, and their prevalence in our society. These objects – be they exquisitely carved ivory chess pieces made from walrus tusks or a beautifullyilluminated manuscript that harkens a new cross-cultural aesthetic – tell us a great deal about the people and societies that created them. We are invited to marvel at how longstanding aesthetic traditions incorporate a game that captured the imaginations of so many in the medieval world, or indeed how the game itself could be a chance for exchange and assimilation.

The stories that people told, using chess as a literary device to broadcast their beliefs or highlight some element of human nature, encourage us to think about the very same in our contemporary moment. How do games today help bring us together, sometimes bridging previously fractious divides? How can the games we play, or stories we tell about them – for instance, Squid Game or The Hunger Games that others have chosen to highlight in this publication – shed light on what our society values, or indeed what it does not?