Students

Wanrongmiao Zhang

Chuyi Yin

Ifeoluwa Titilope Owolabi

Jiayao Chen

Yaqiao Liao

Madeeha Ayub

Yinan Fang

Shihua Chen

Yu-Cheng Lin

Chia-Wei Chan

Amelia Rose Linde

Yunsong Liu

Yuli Wang

Territory

Iceland

Ruhr Valley

Southern Nigeria

Bohai Economic Rim

Sichuan

Kashmir

Ganges Basin

Singapore

Indonesian Archipelago

Metropolis Los Angeles

Lake St Clair Watershed

Medellin Metropolitan Area

South American

Infrastructural Integration

Urbanism

Anthropocene / Hinterland / Planetary

Crisis / Emergency

Critical

Ecological / Landscape

Everyday / Emperical

Ephemeral

Informal / Insurgent

Infrastructure / Network

Lean / New / Tactical

Post-Colonial

Post-Industrial

Smart City / Digital

Social

Utopian / Visionary

Global

Conflict Resilient

University of Michigan

Maria Arquero de Alarcon TAMUD

Post-extraction

......

2020

034 Ruhr Valley

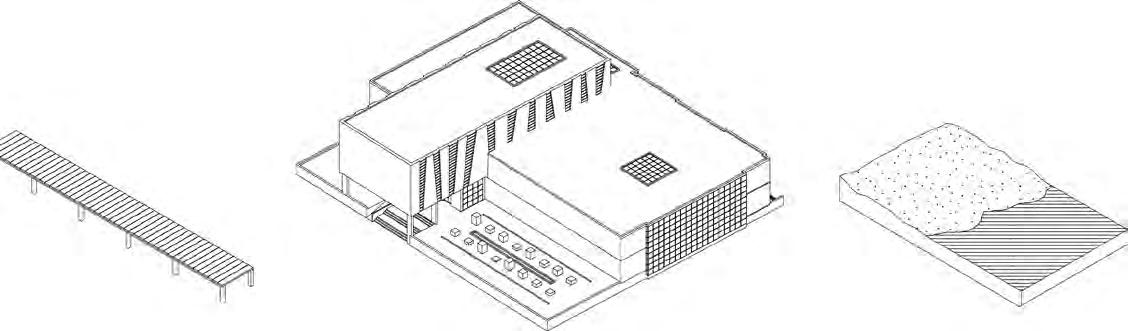

Zollverein Park Lake Phoenix Averdung Plaza

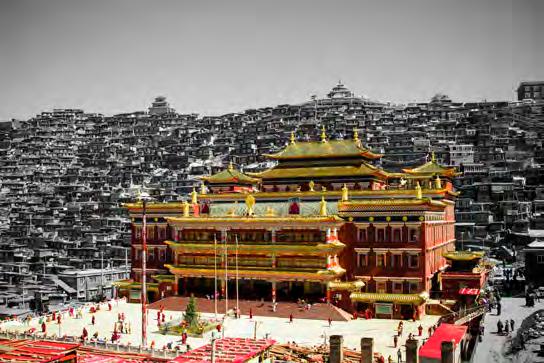

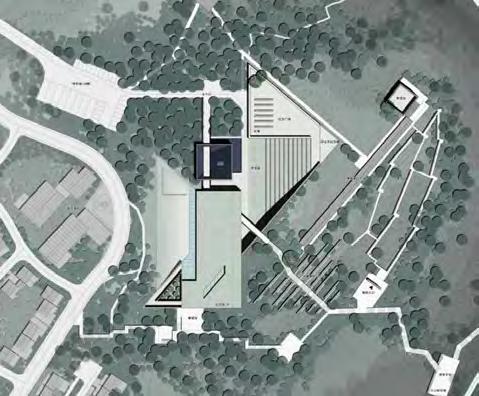

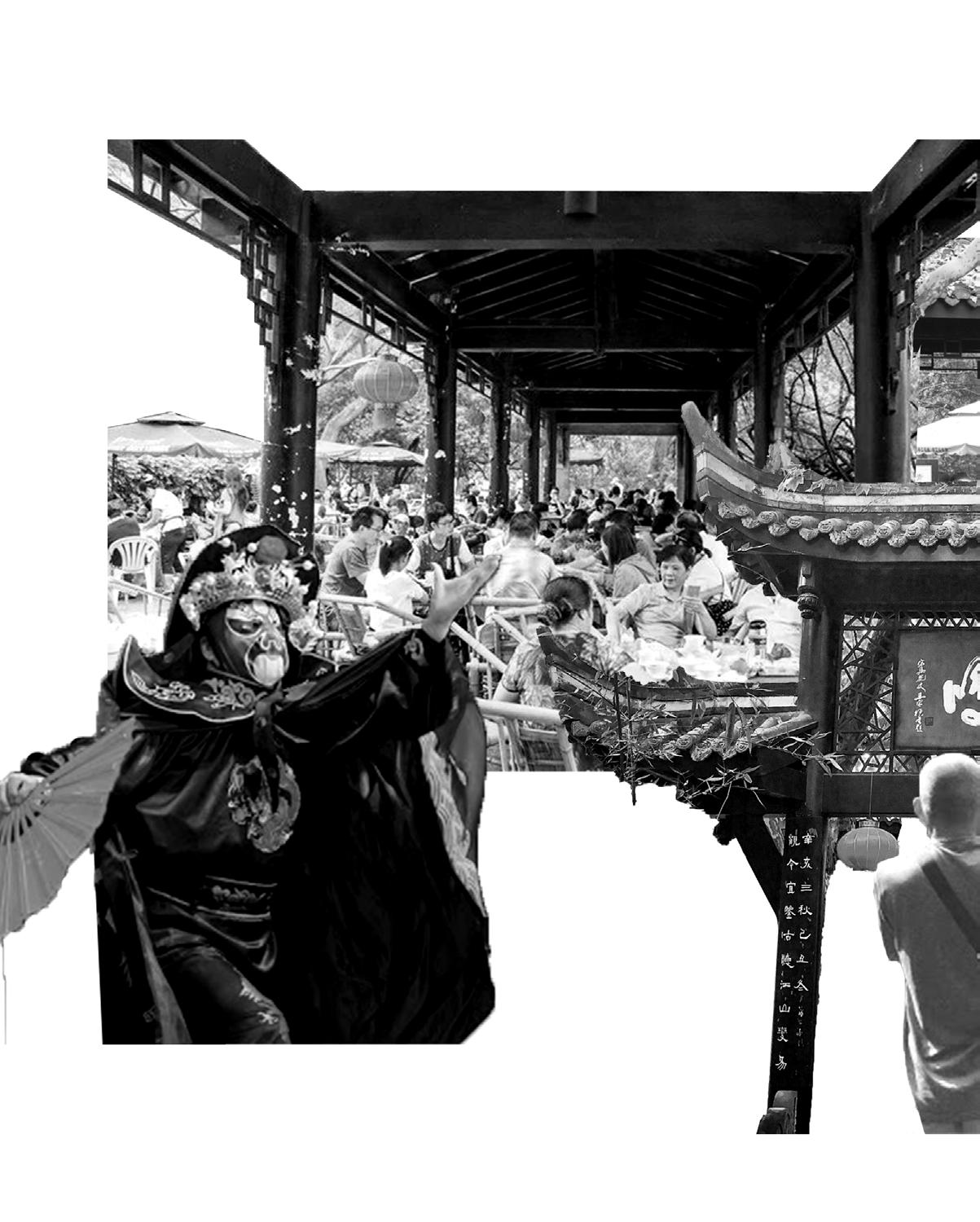

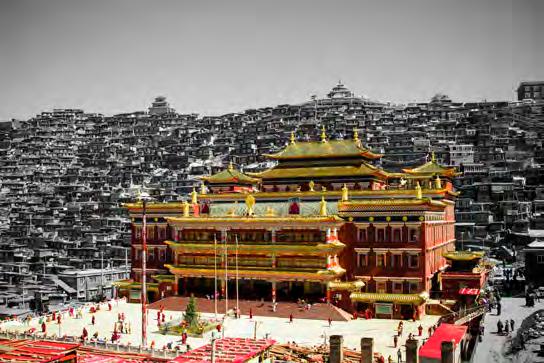

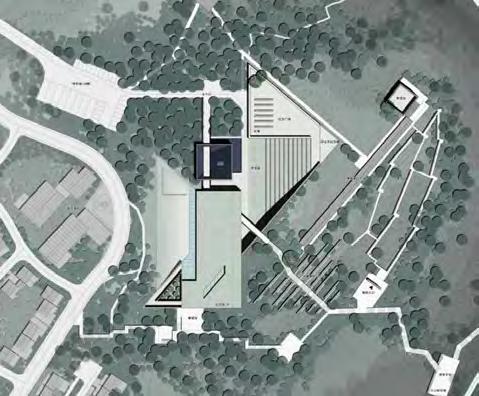

120 Sichuan

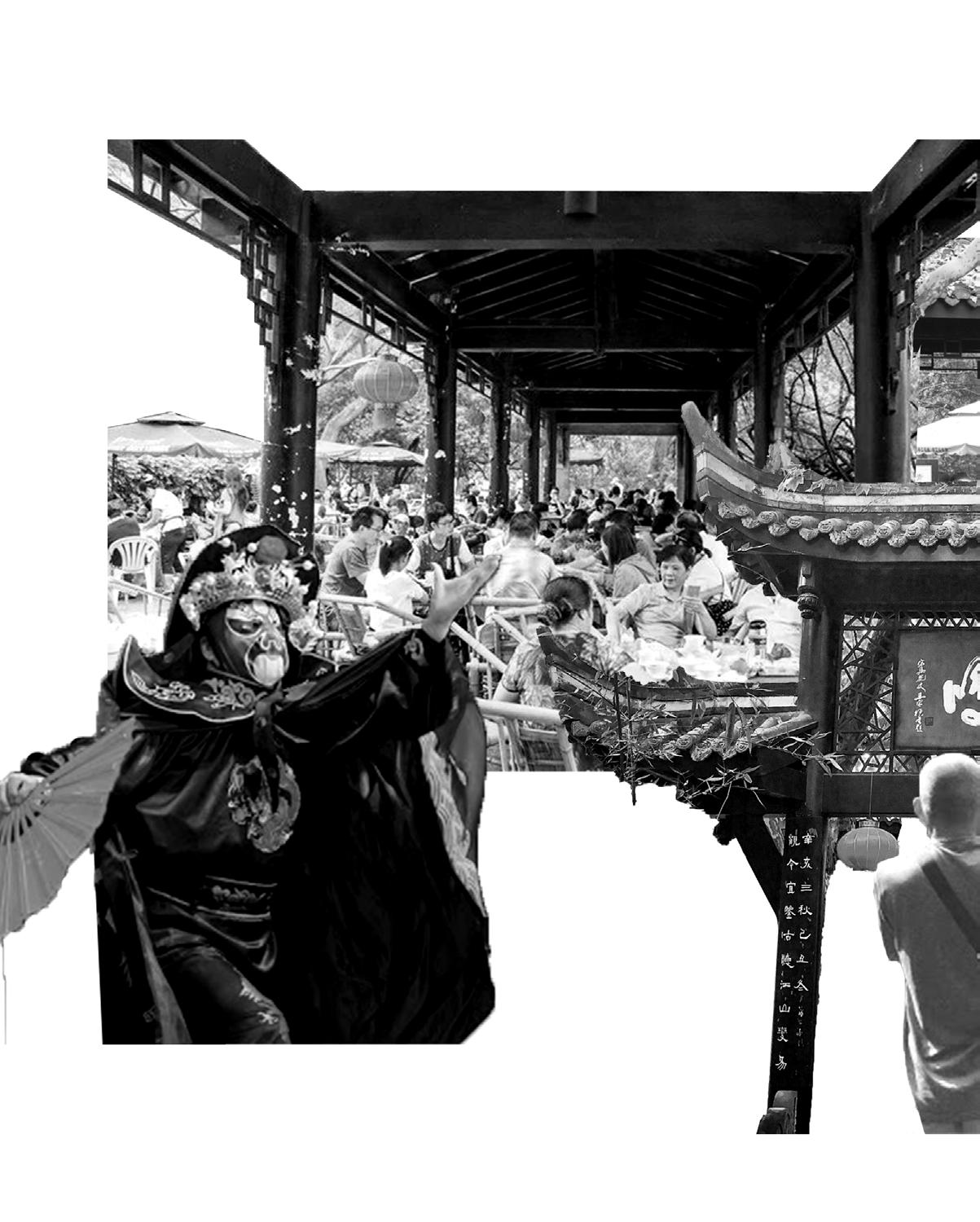

Serta Larung Gar Buddhist Academy Ying Xiu Town Reconstruction Heming Tea House

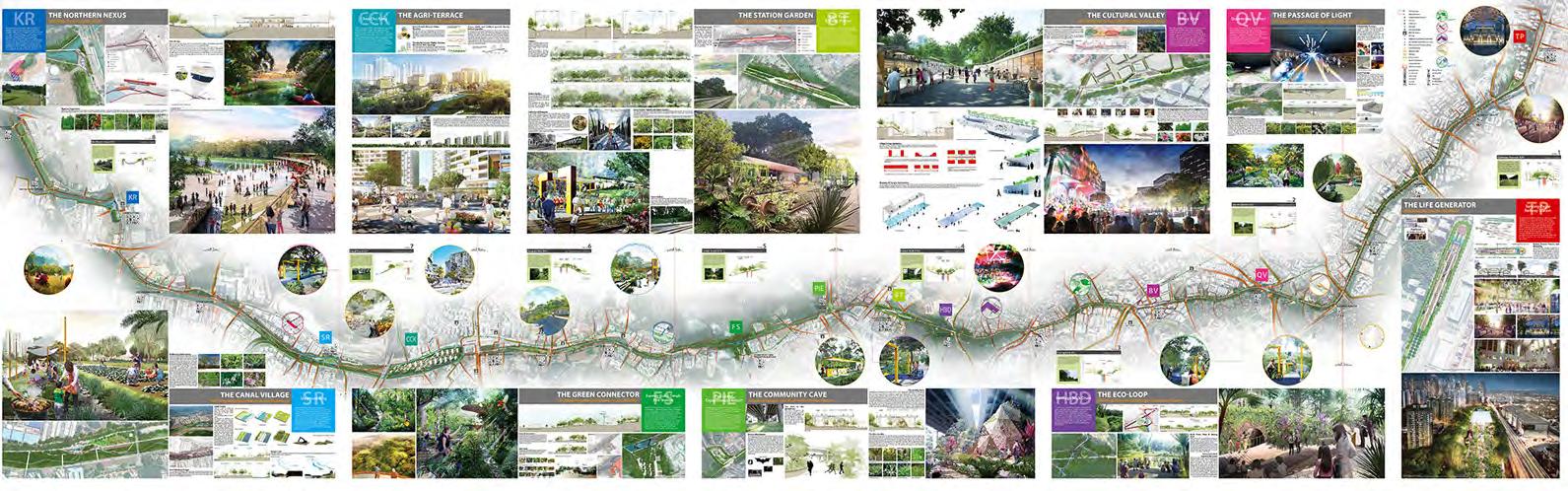

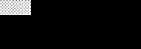

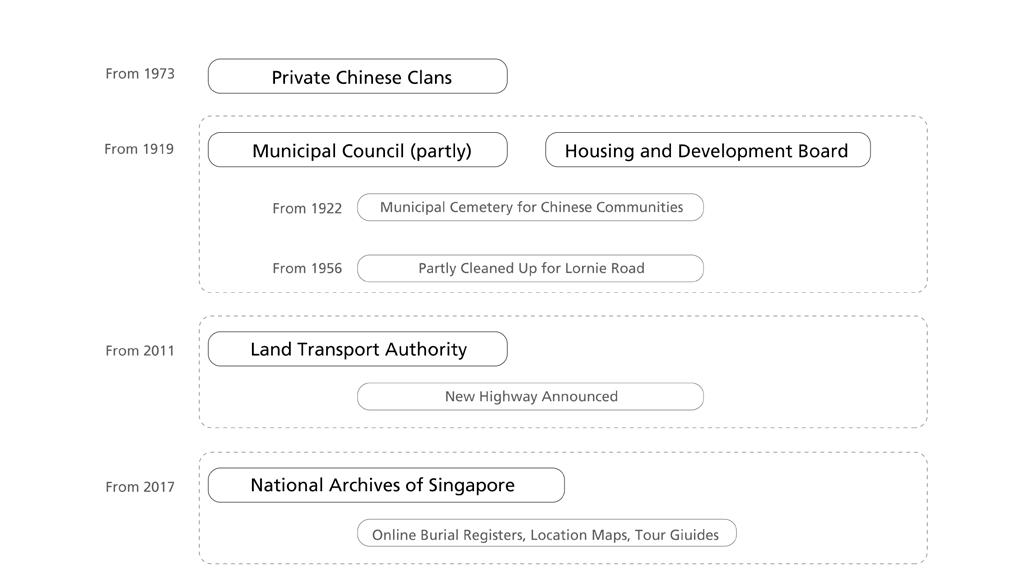

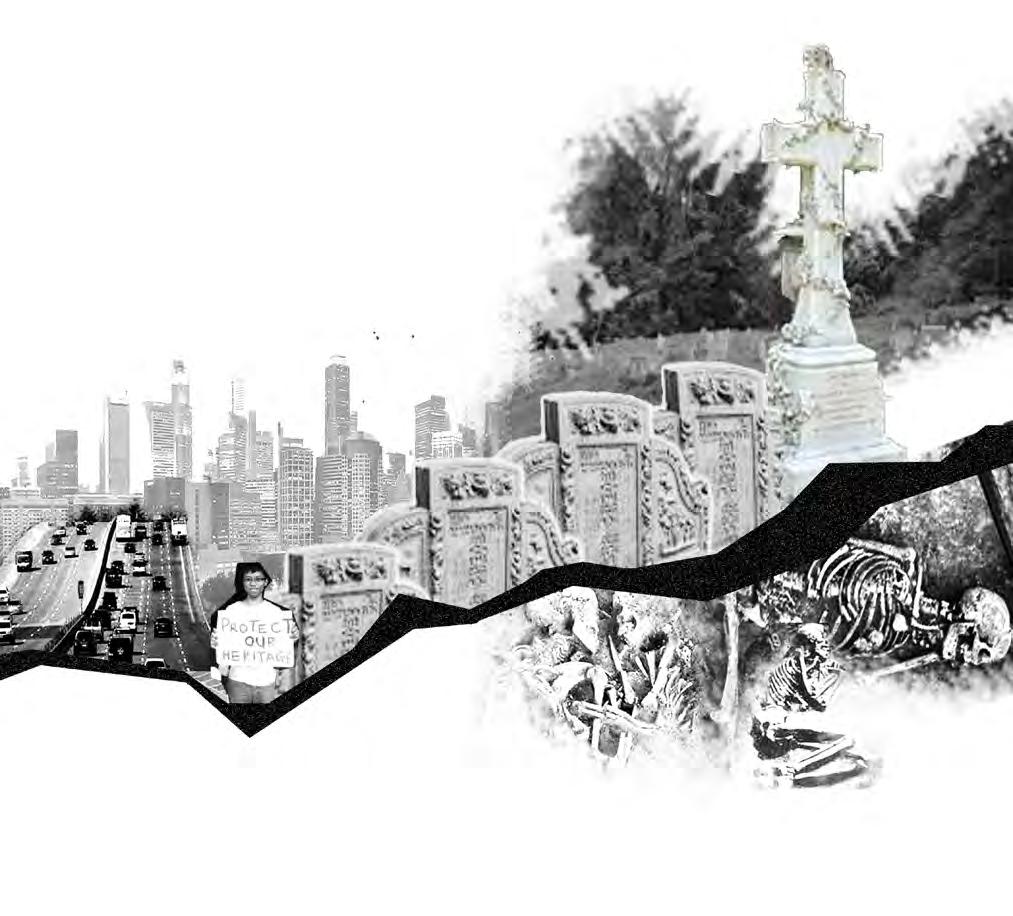

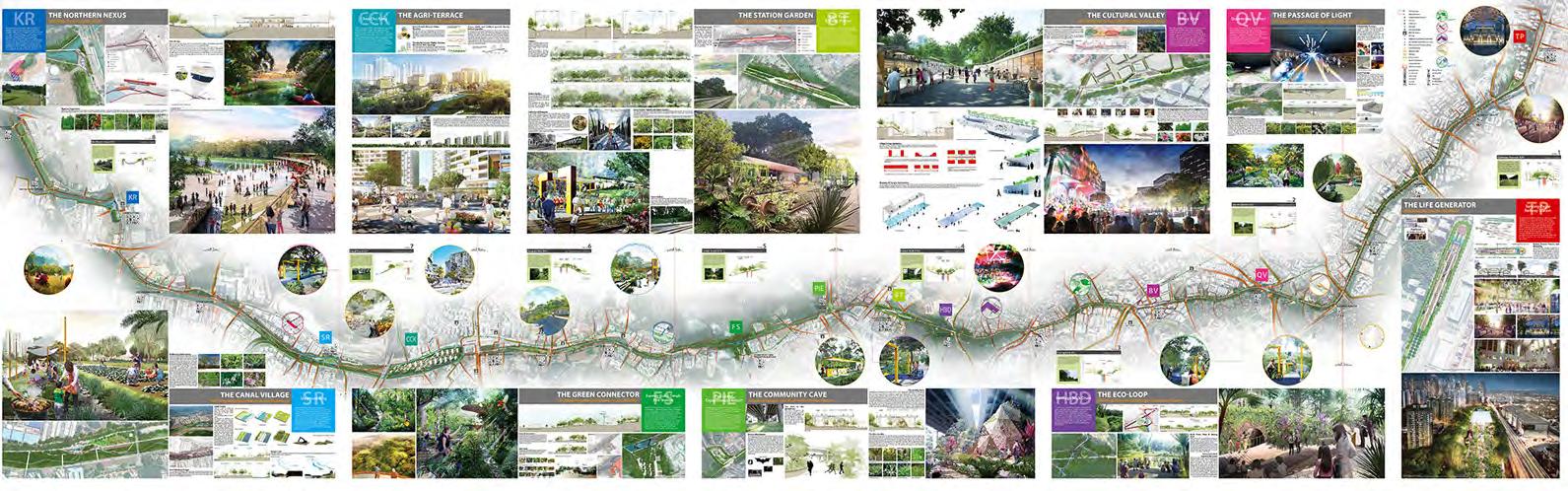

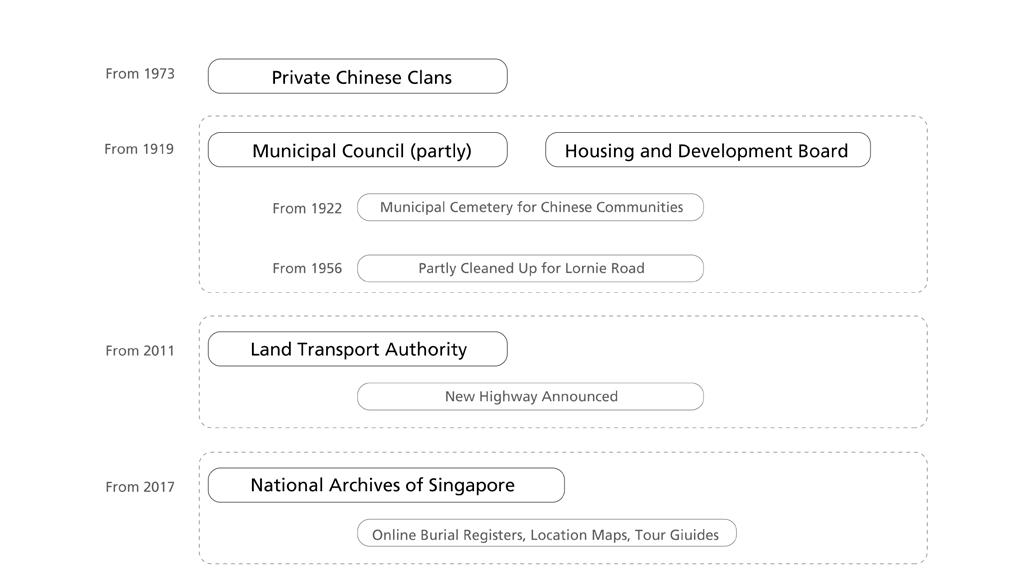

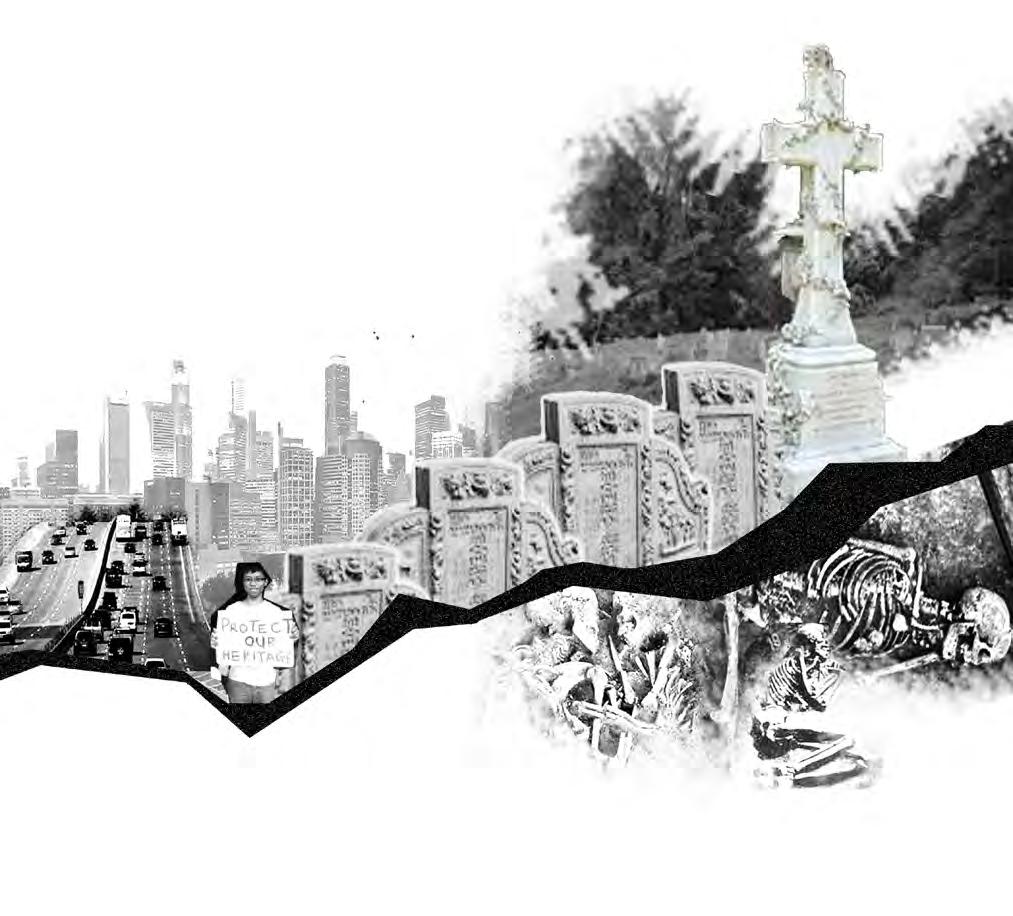

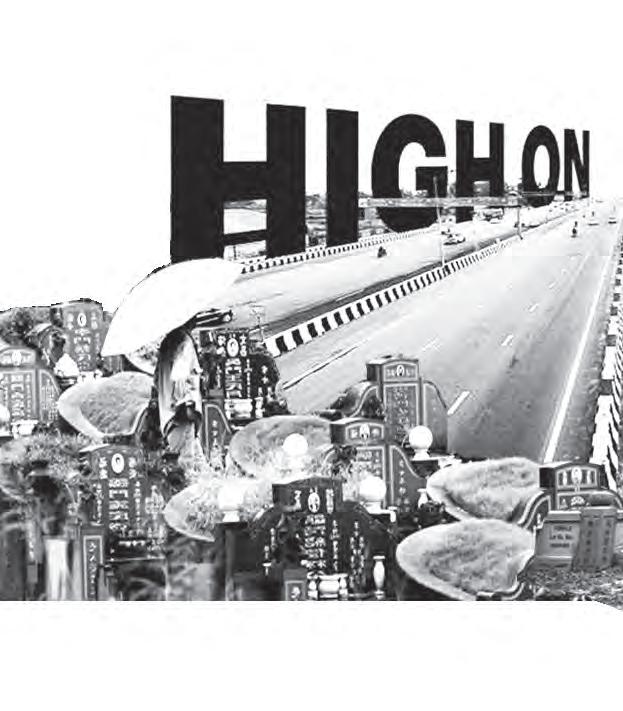

210 Singapore

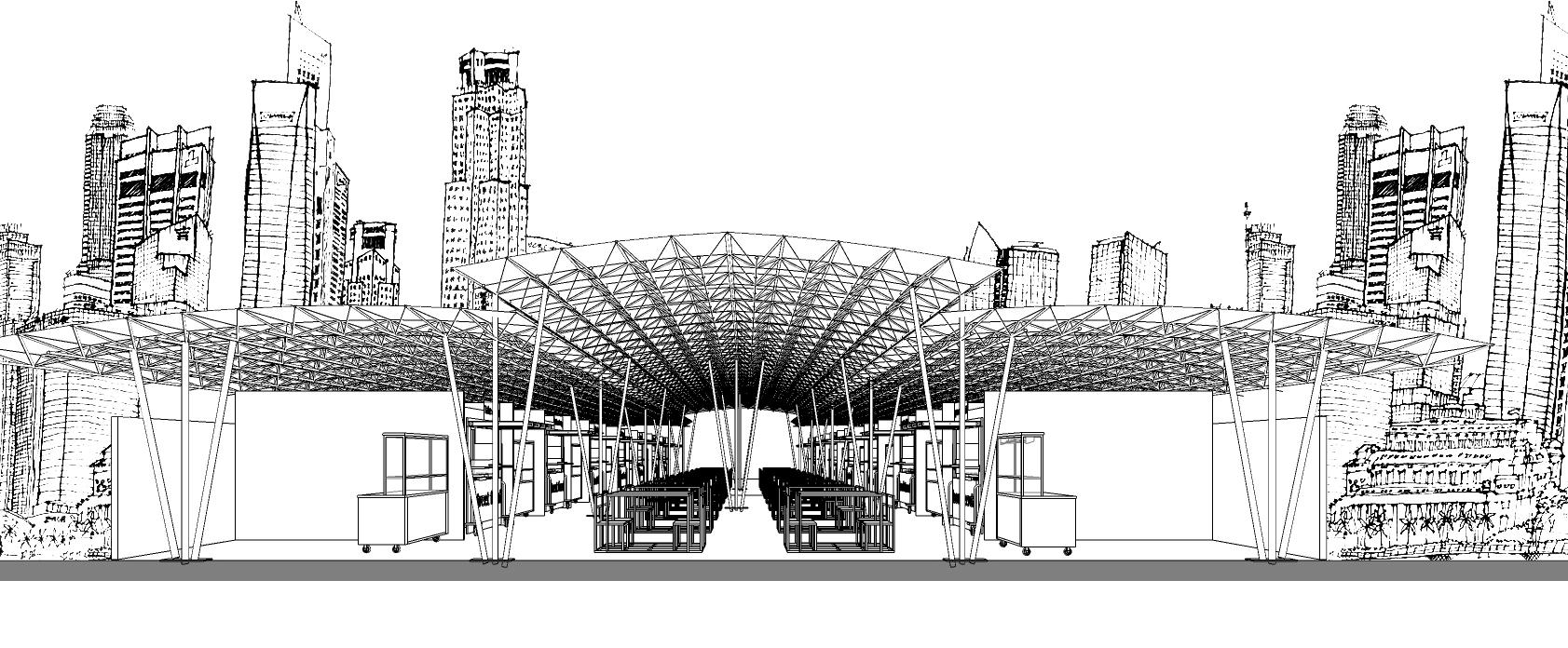

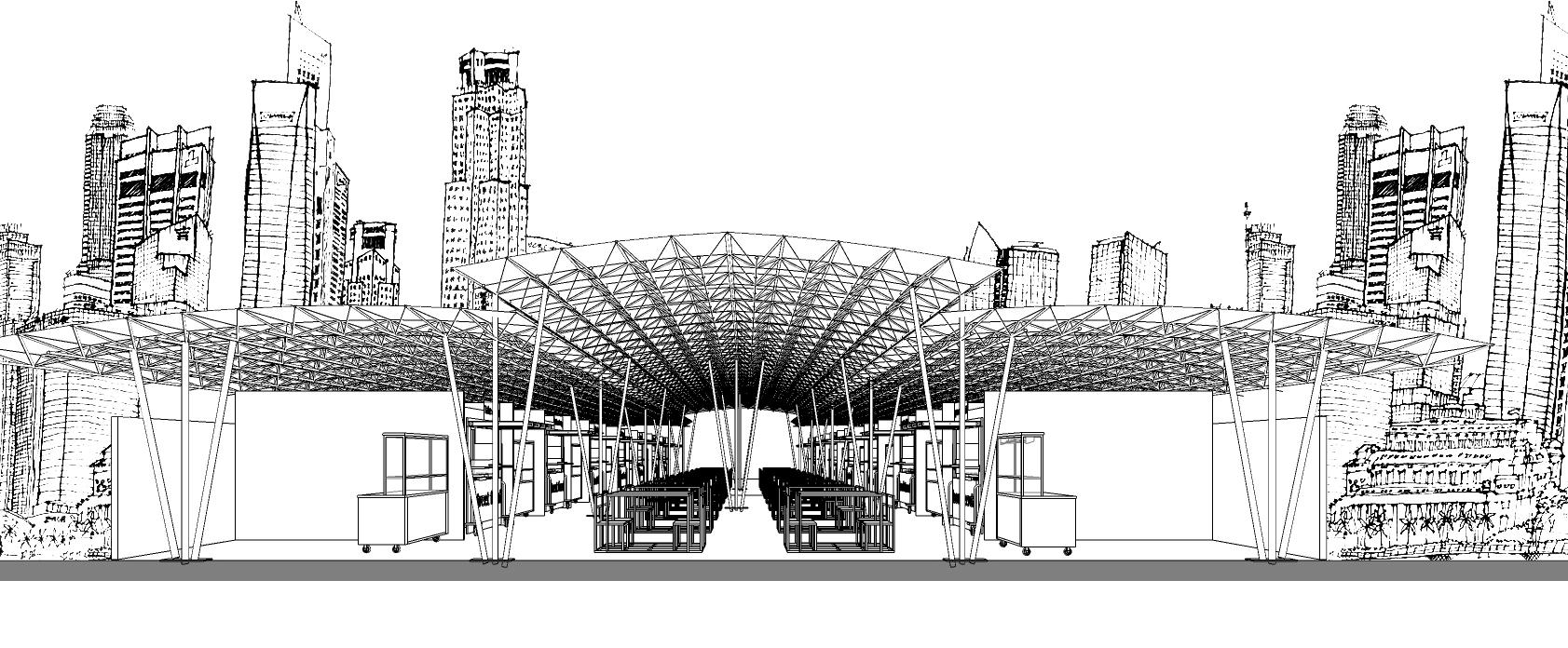

Rail Corridor Bukit Brown Hawker Center

322 Lake St Clair Watershed

Waterfronts Suburbia Food Justice and Water Right

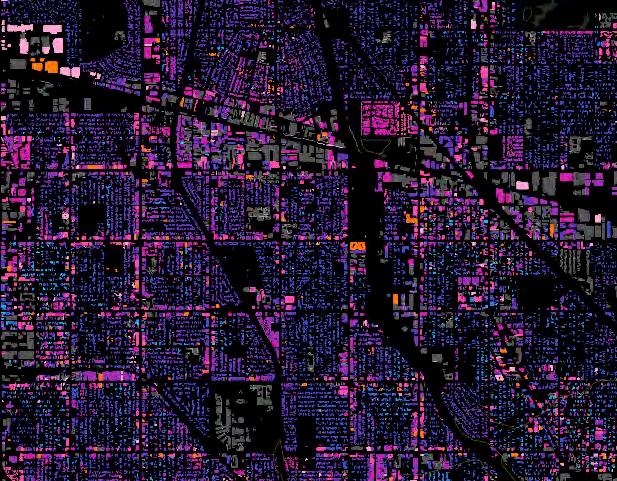

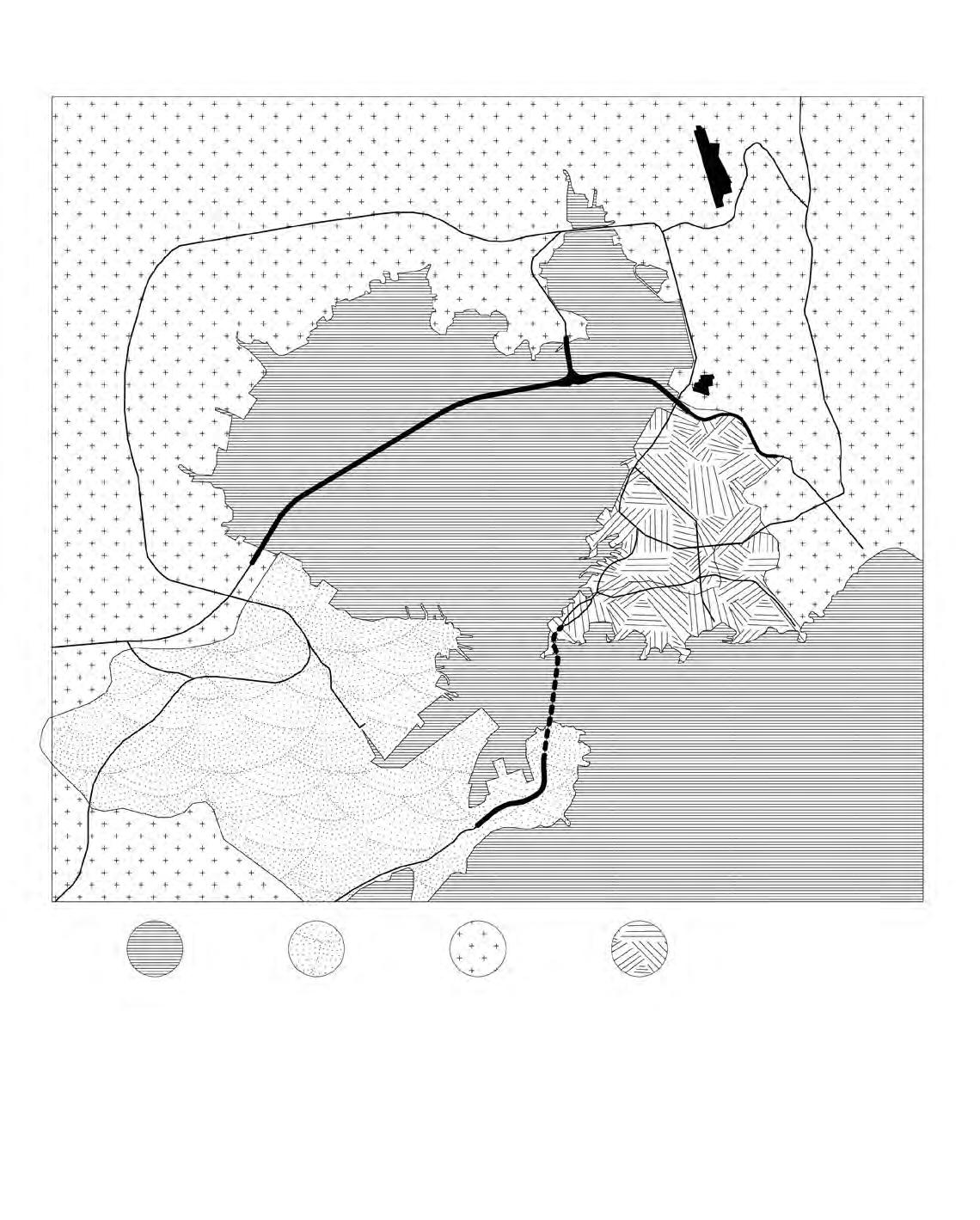

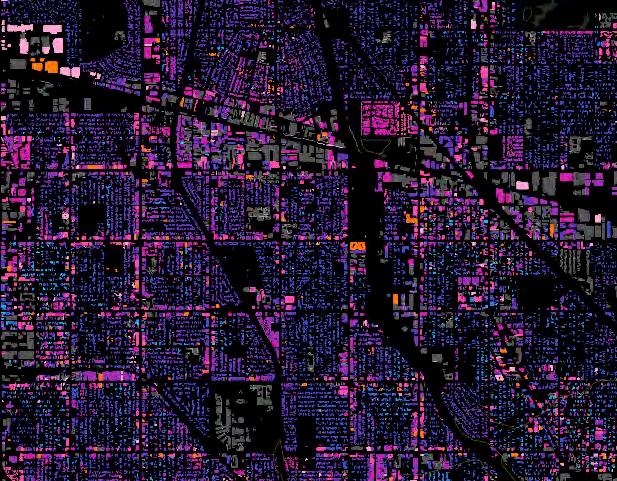

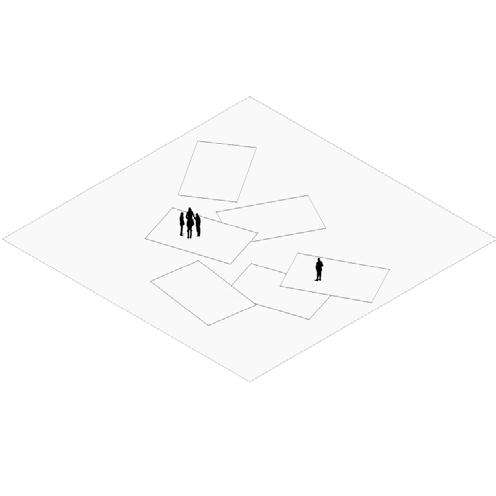

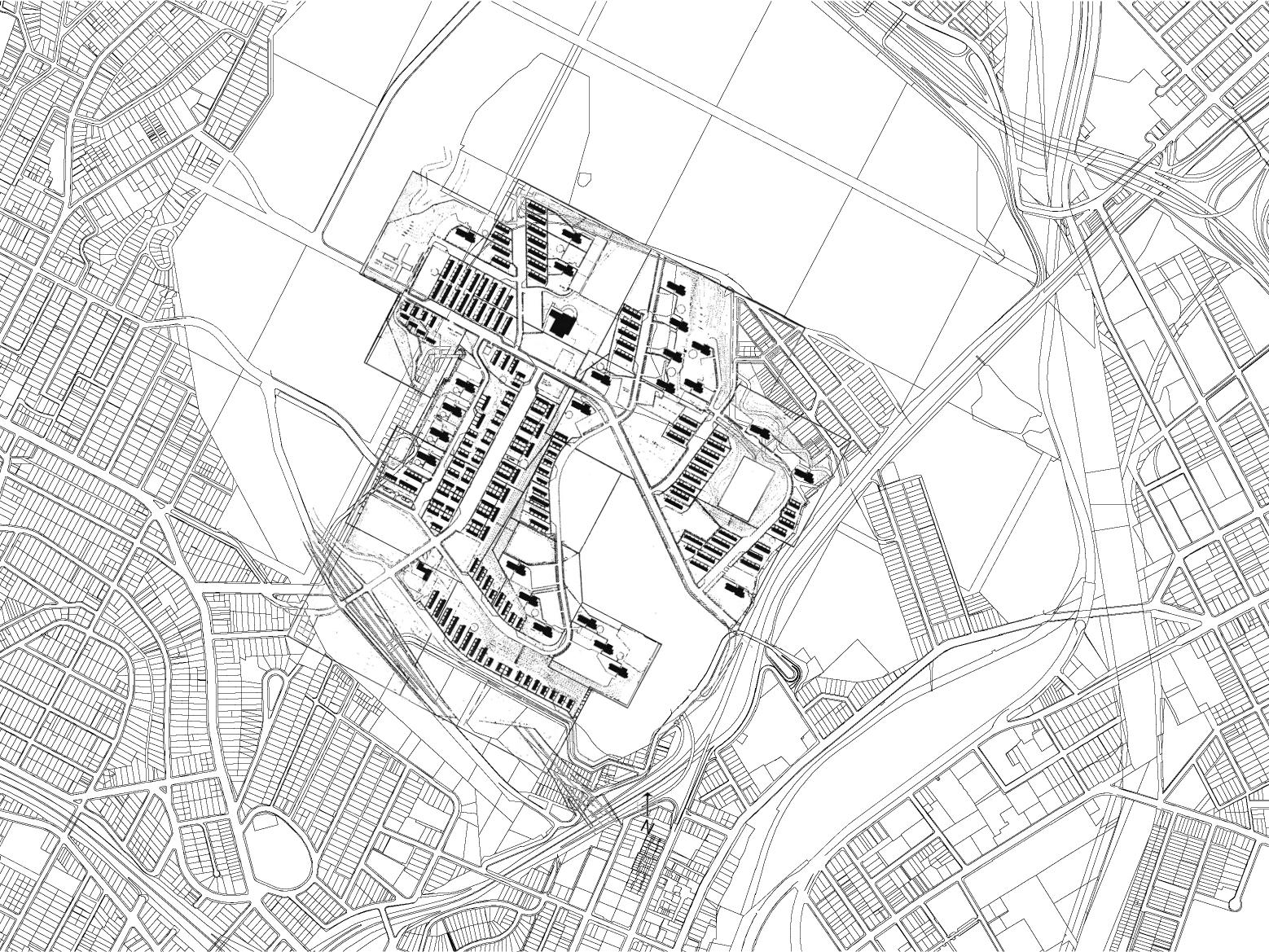

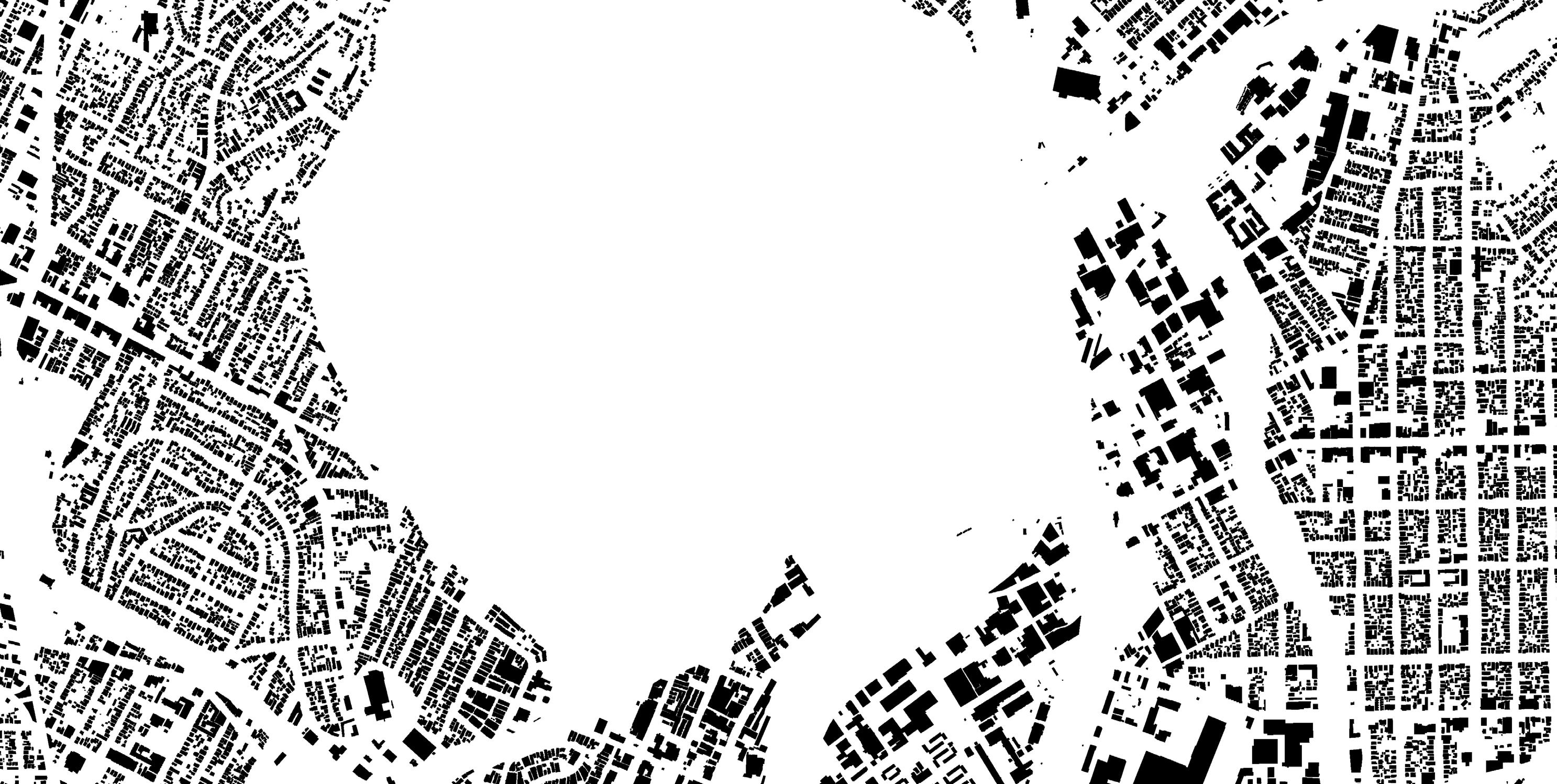

002 Collective Map

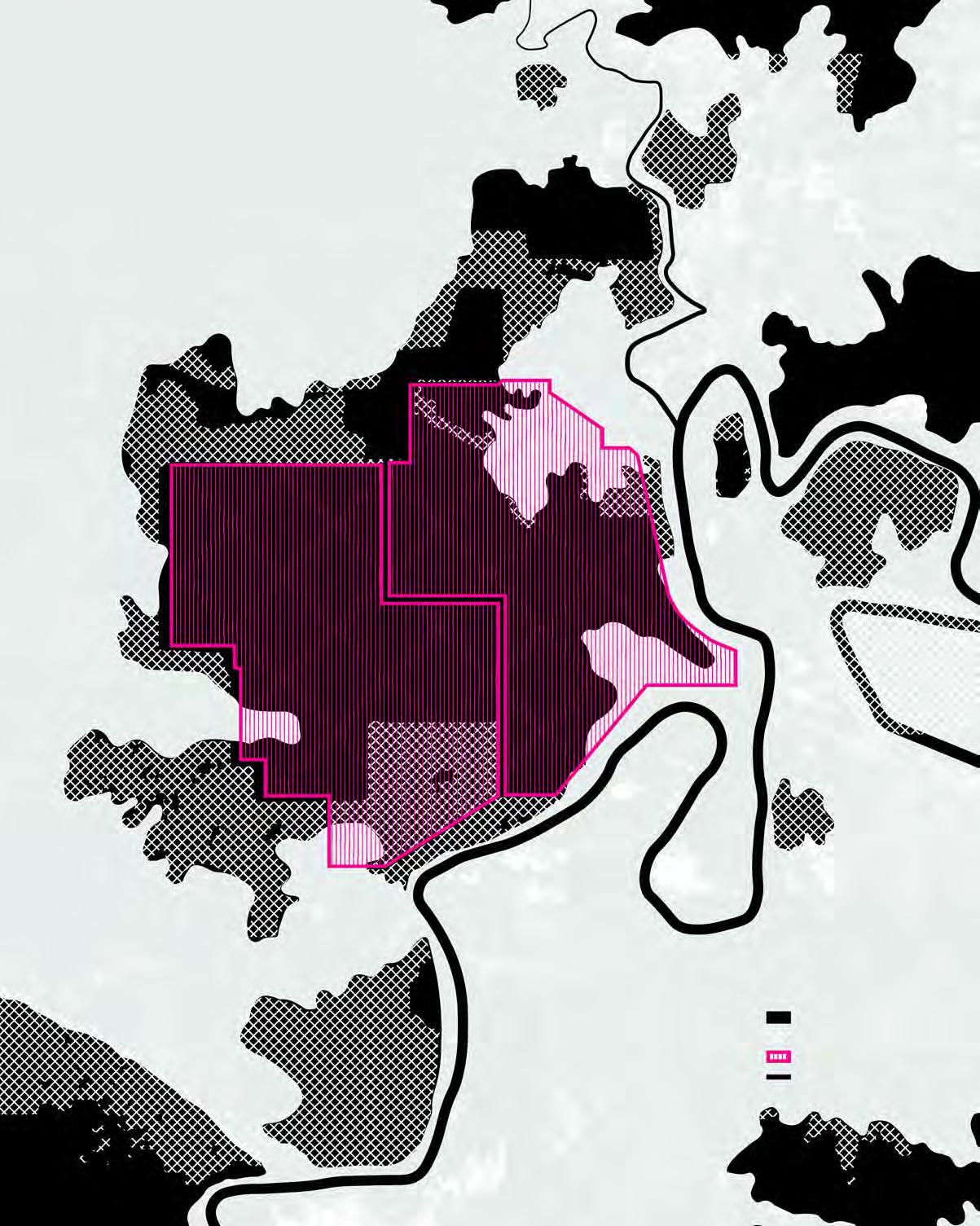

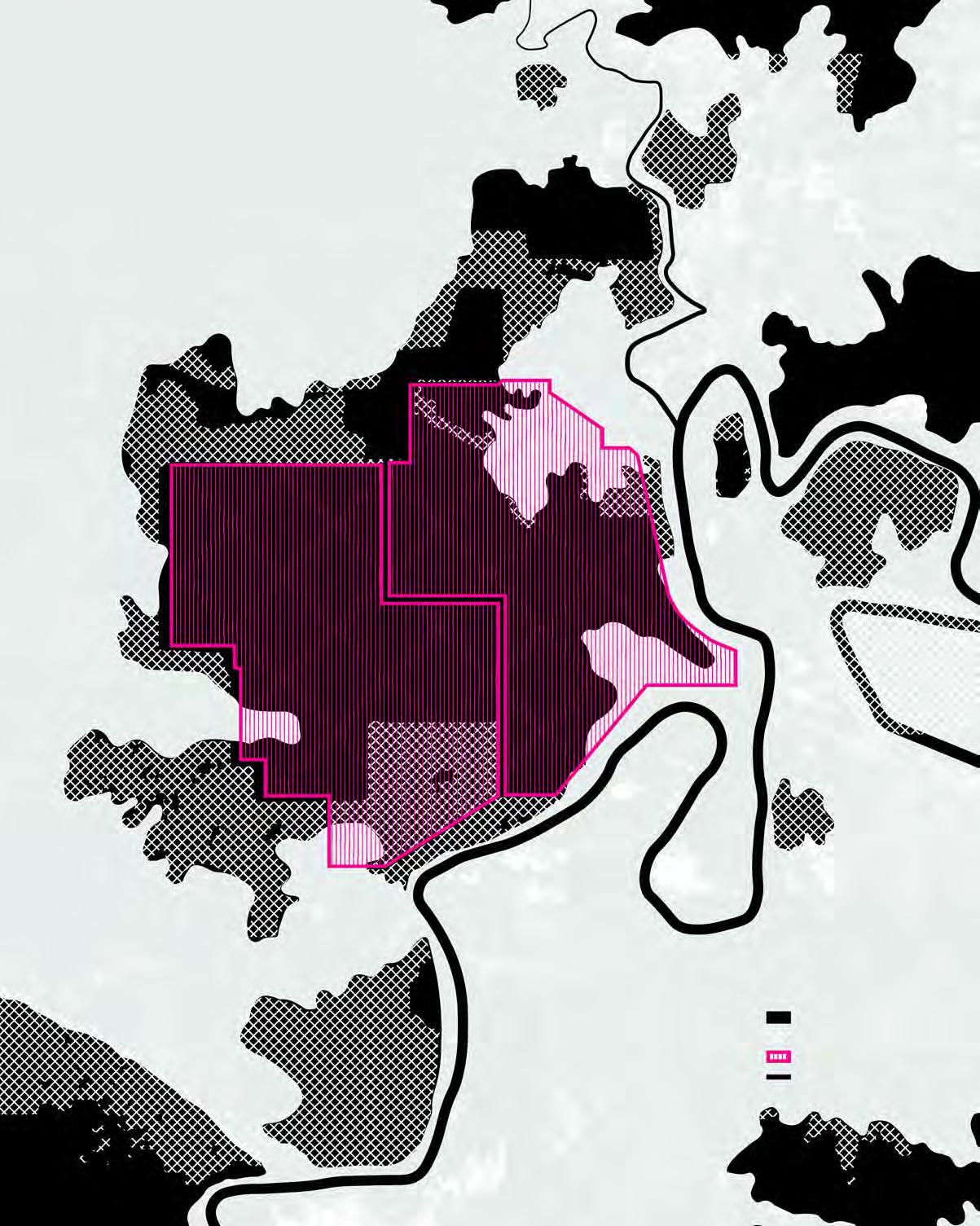

066 Southern Nigeria

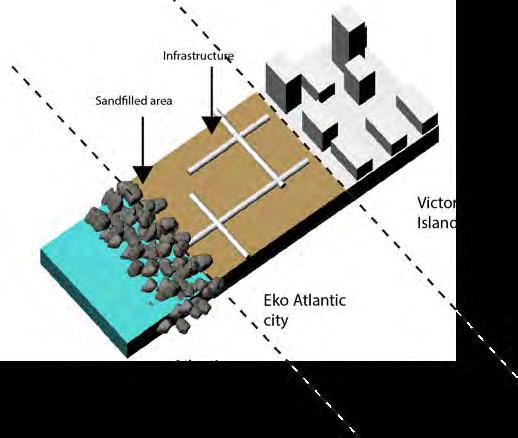

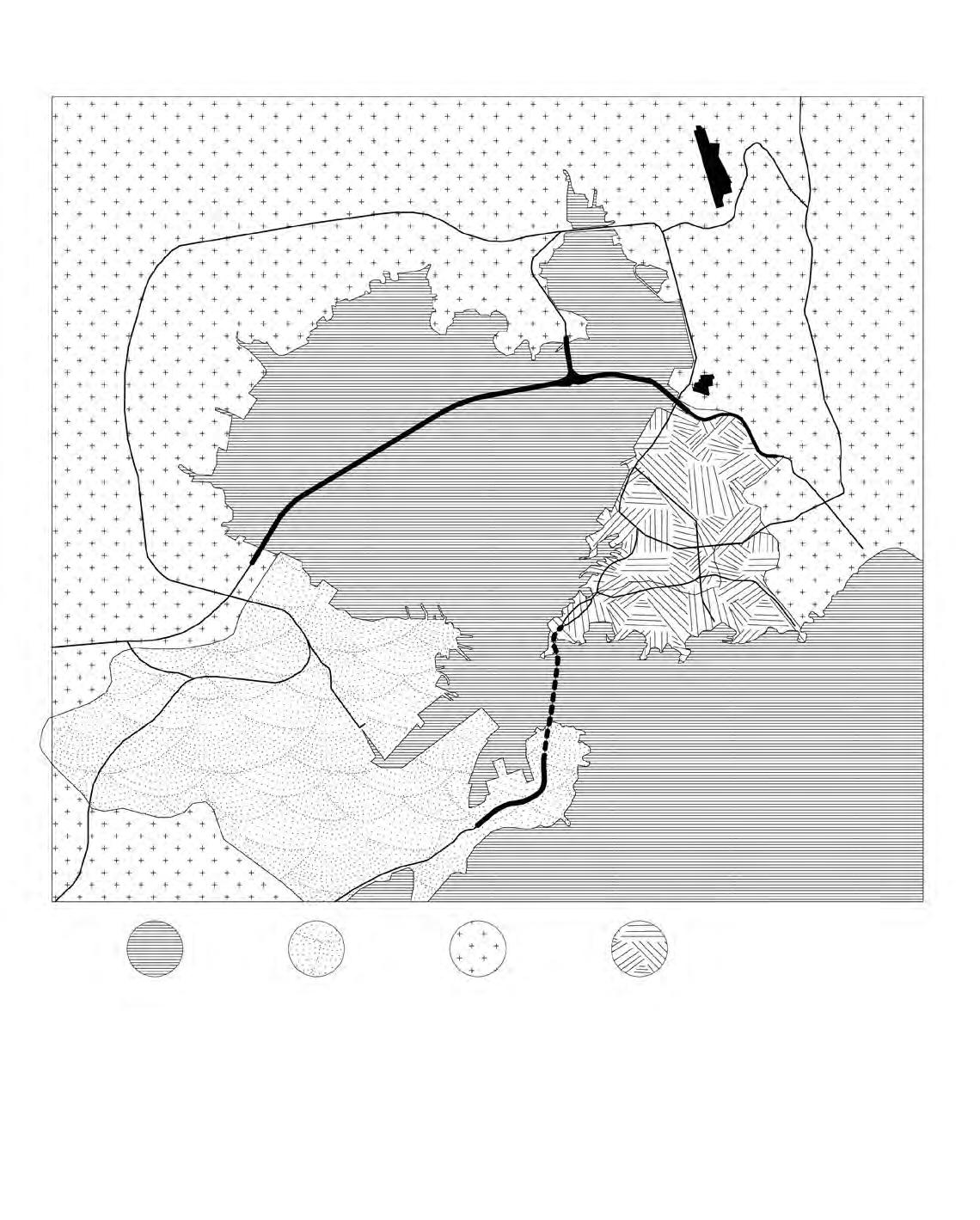

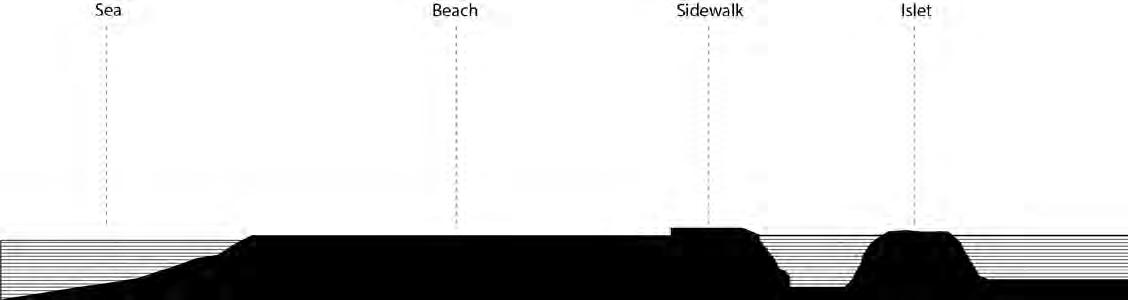

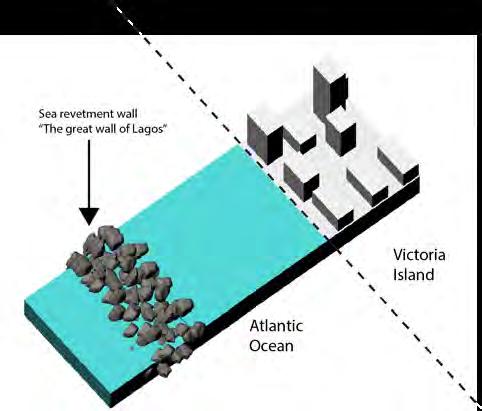

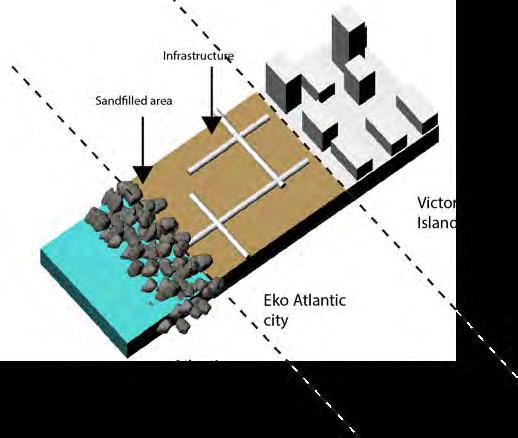

Okrika Water-front Community Eko Atlantic City Makoko Slums

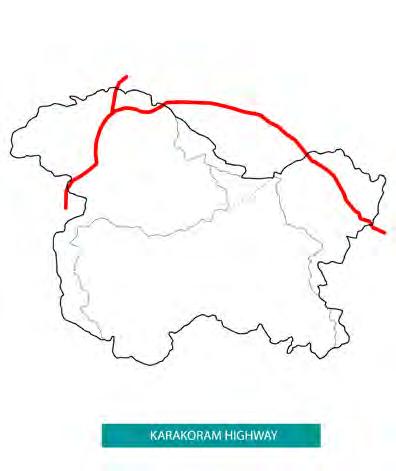

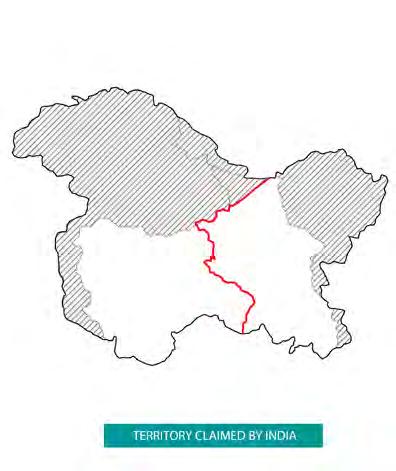

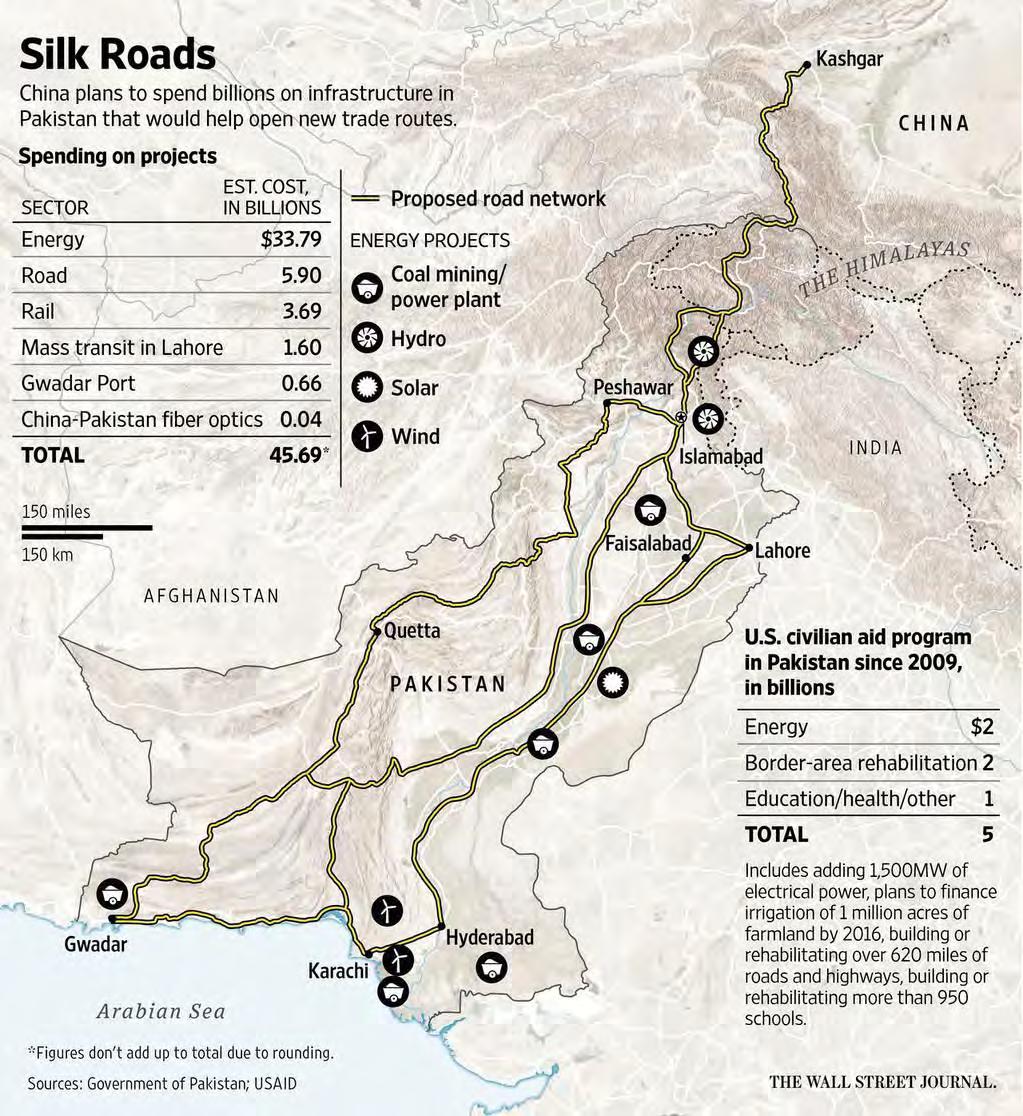

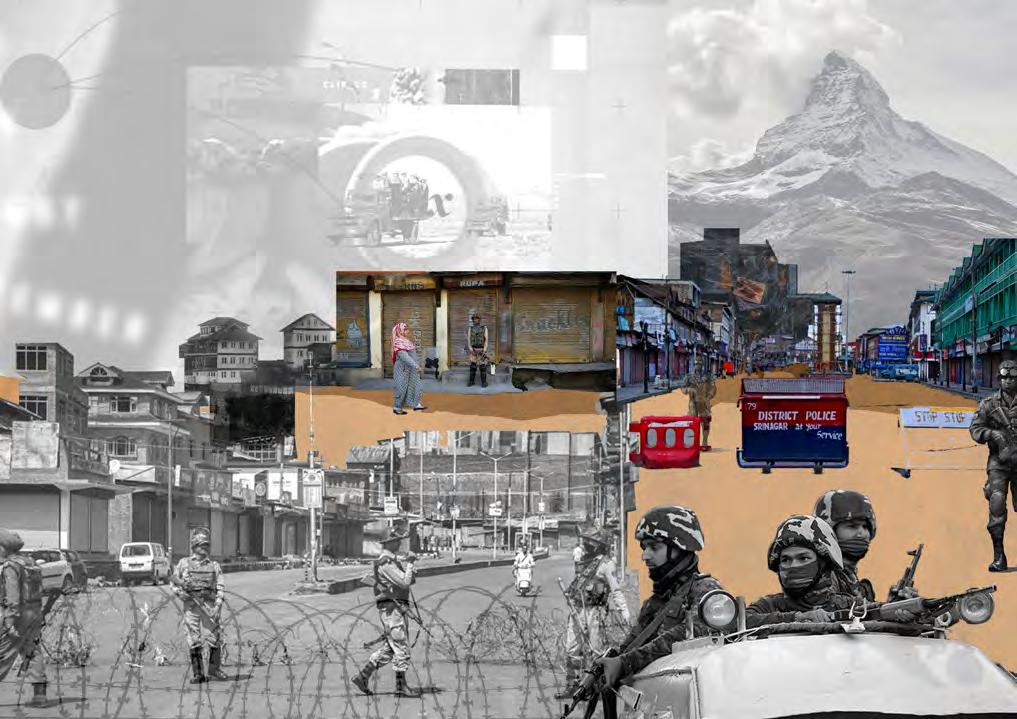

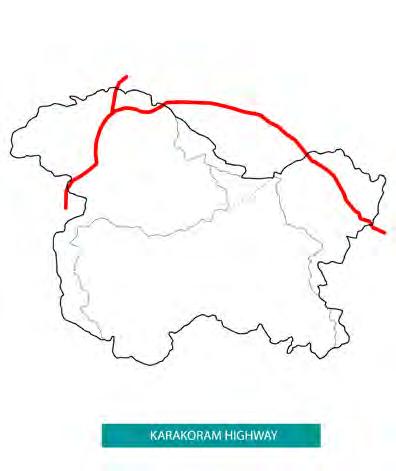

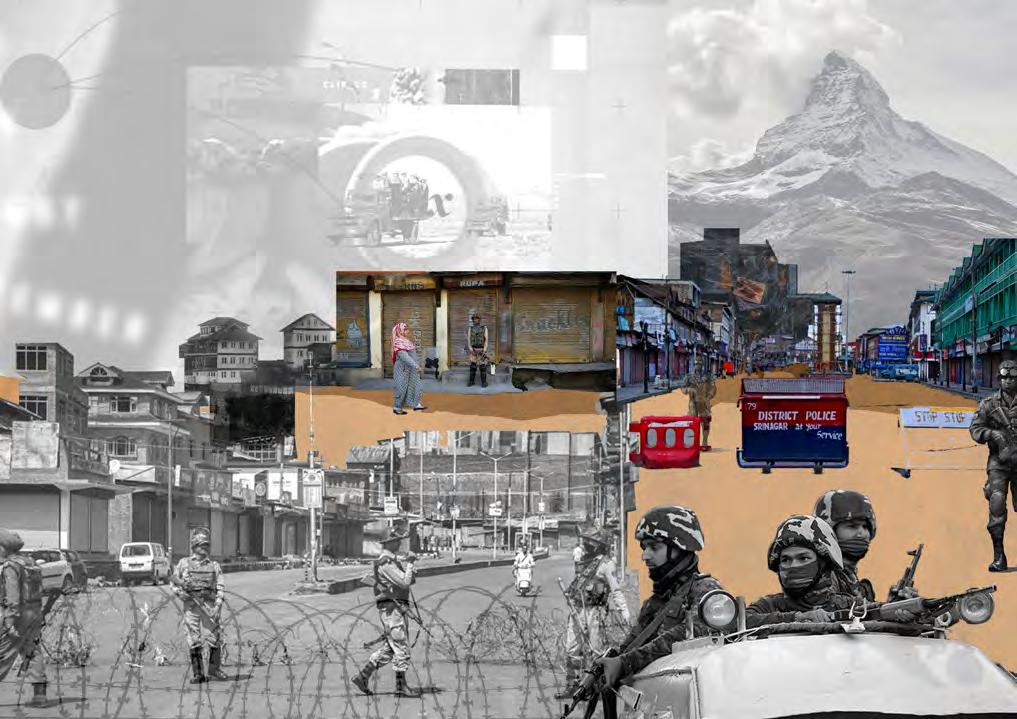

150 Kashmir Kashmir as a Passage Kashmir as a Host Kashmir as a Territory

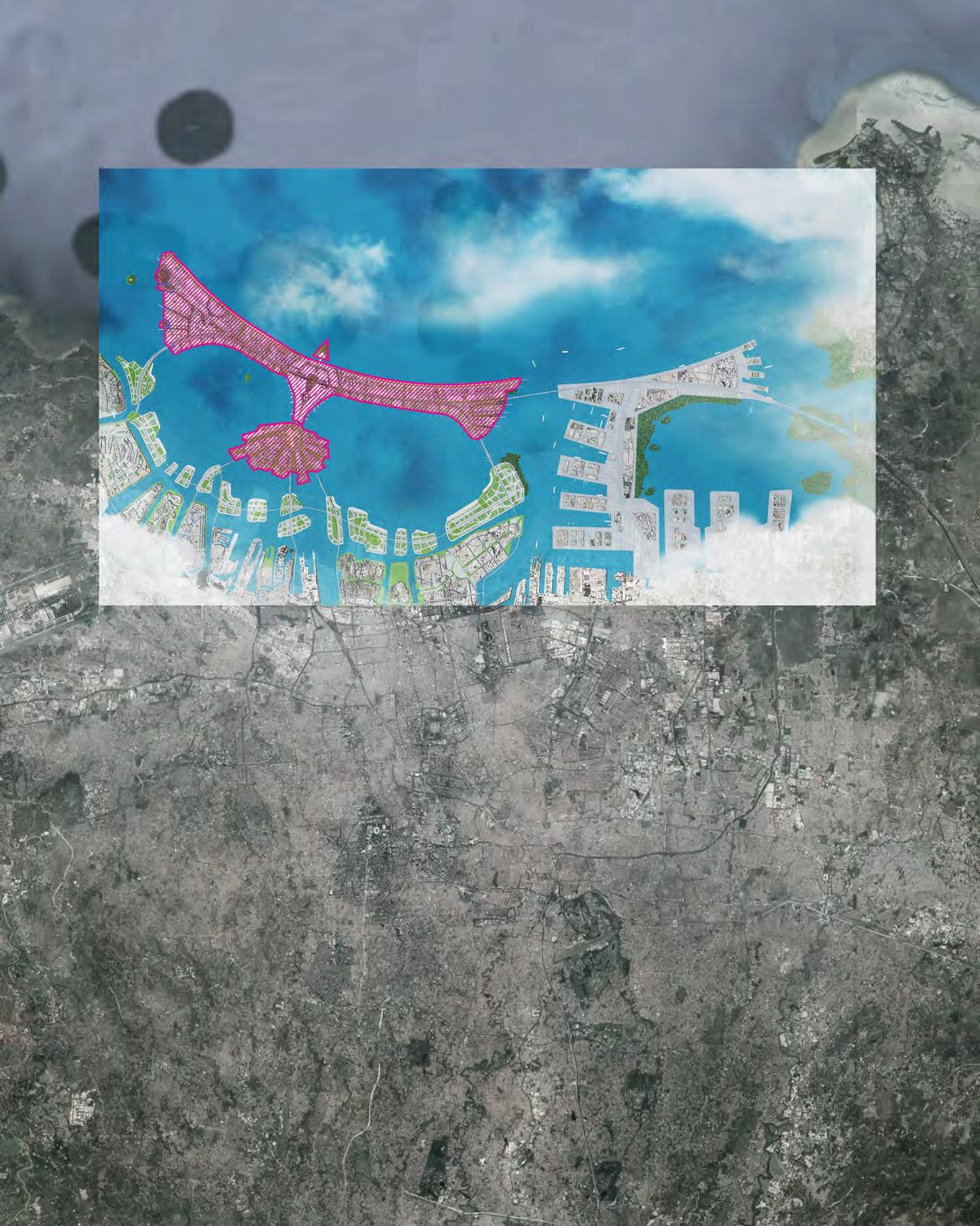

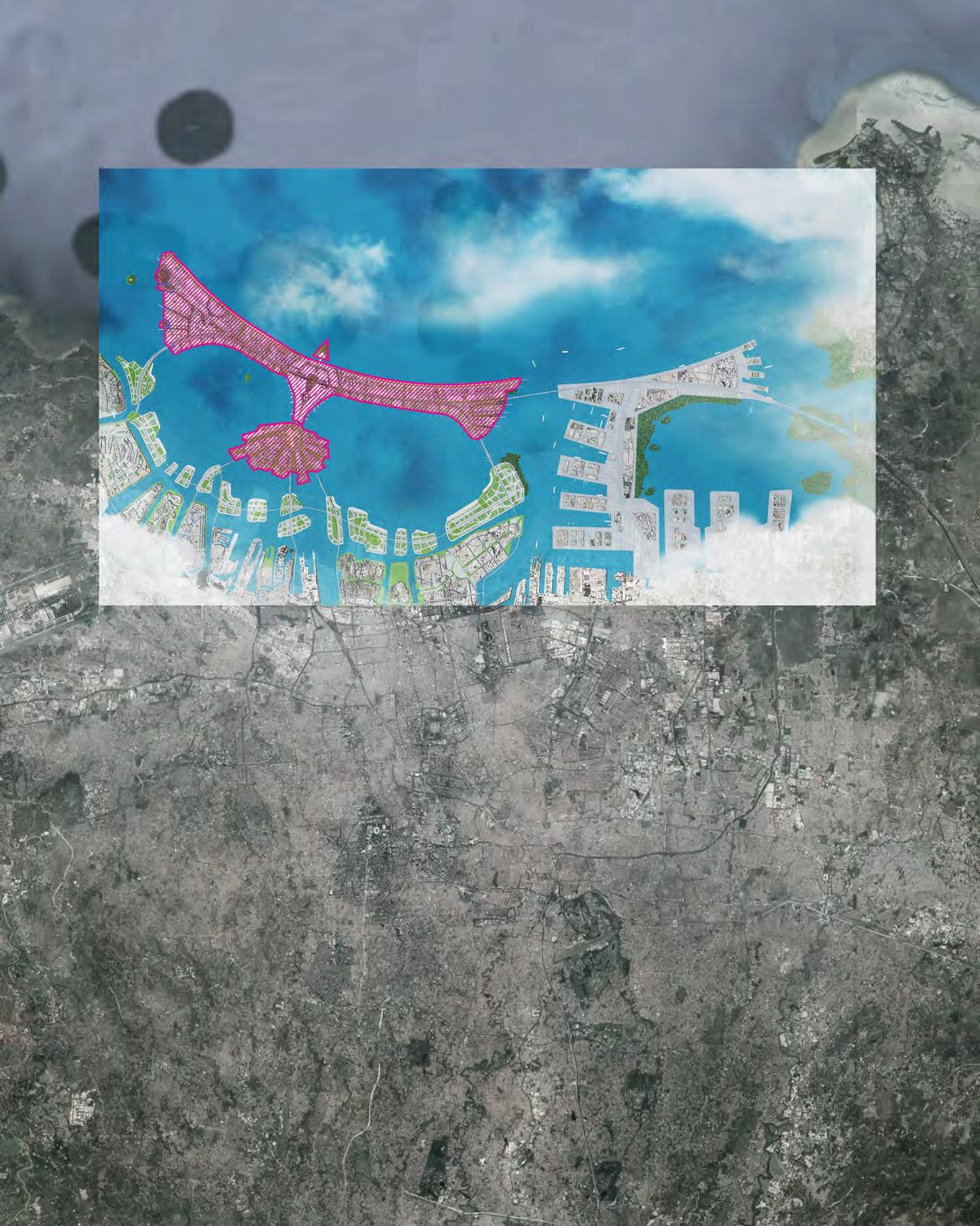

242 Indonesian Archipelago

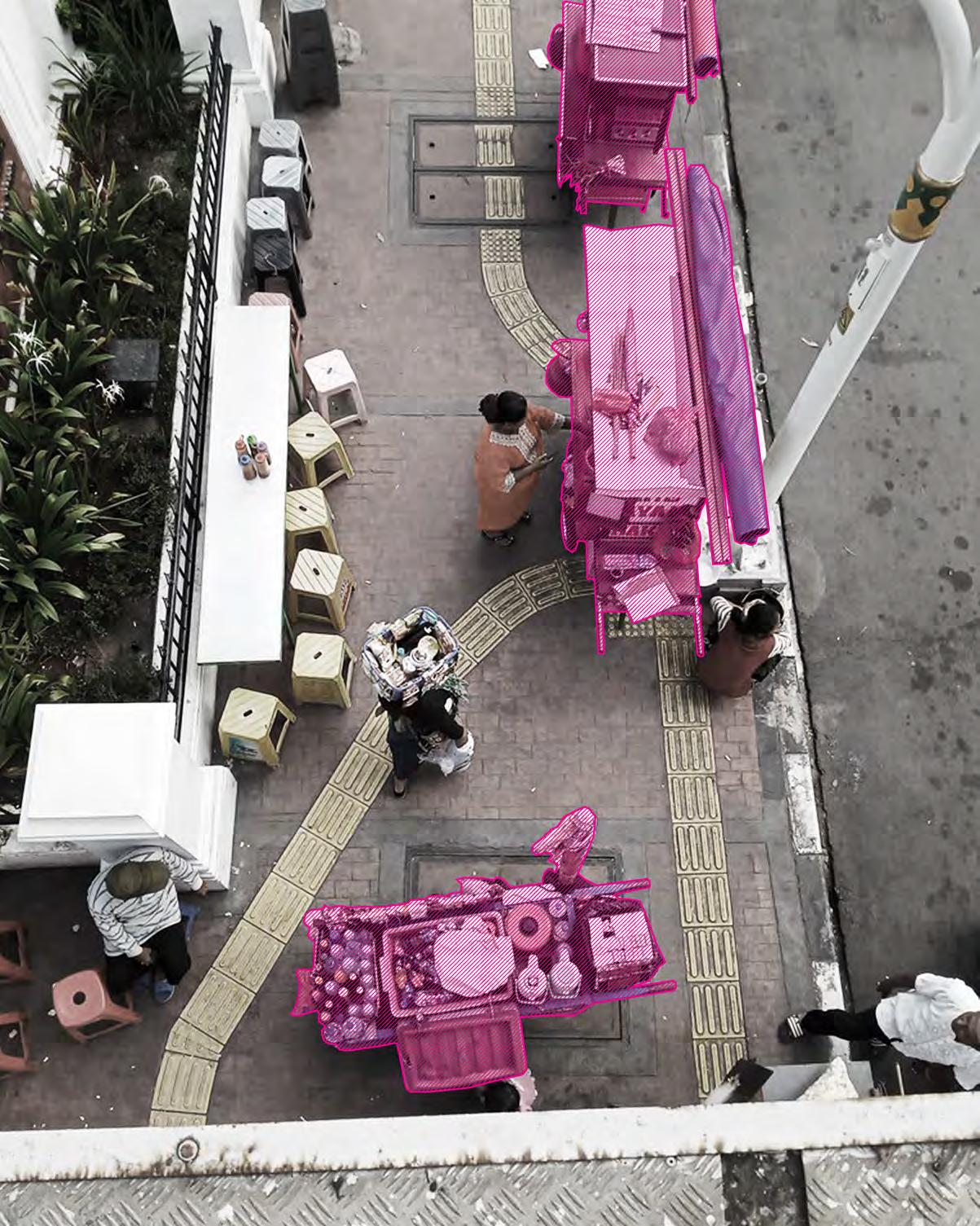

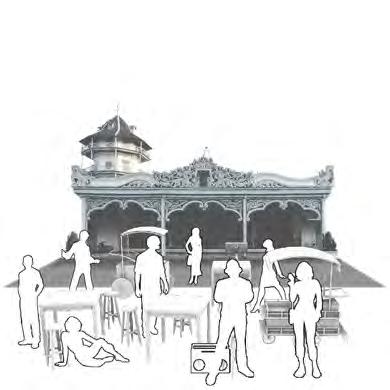

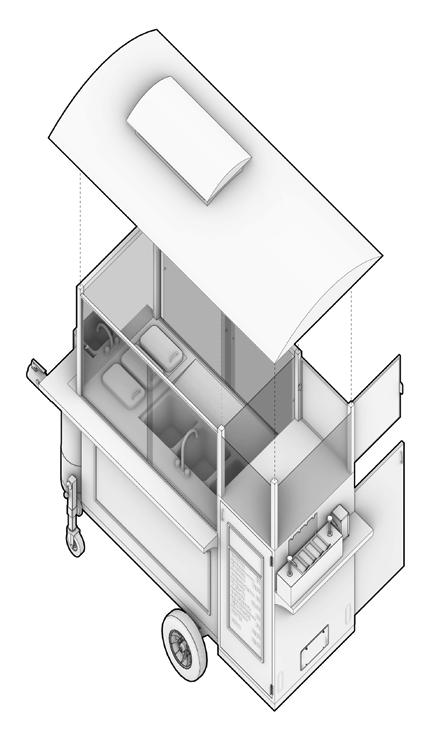

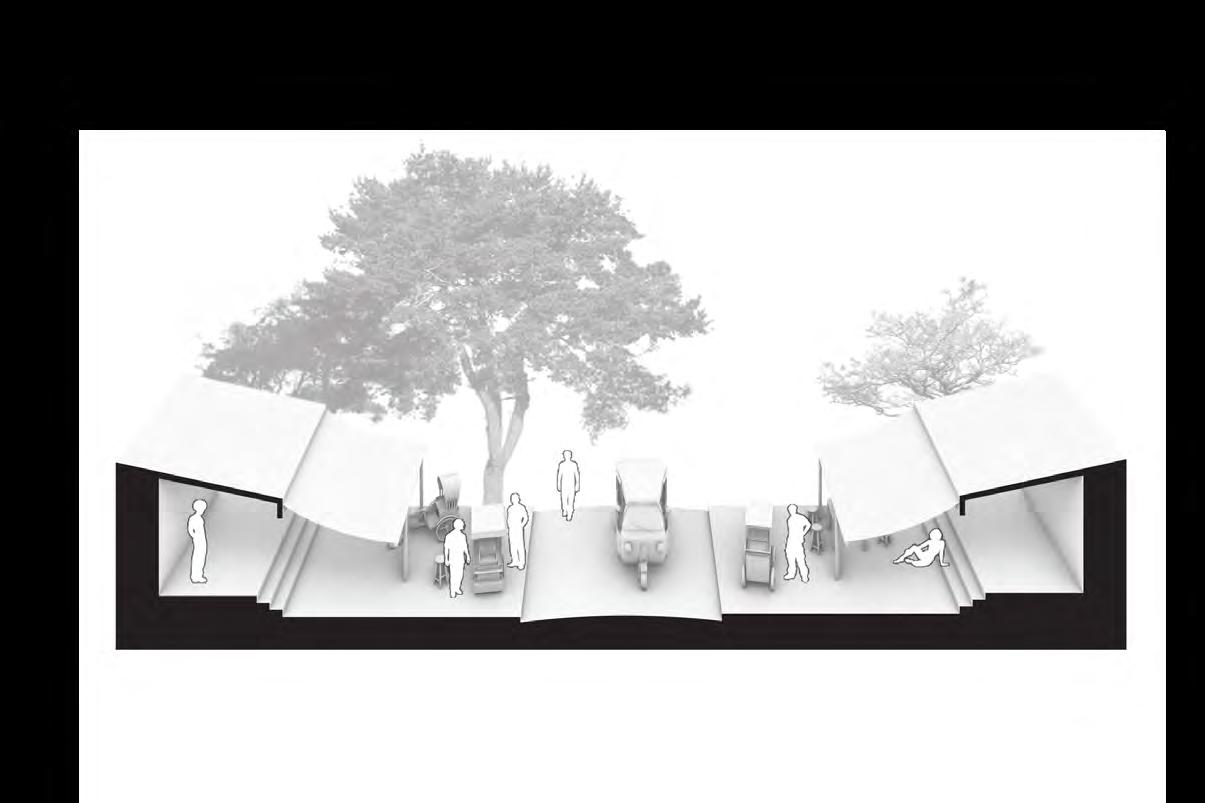

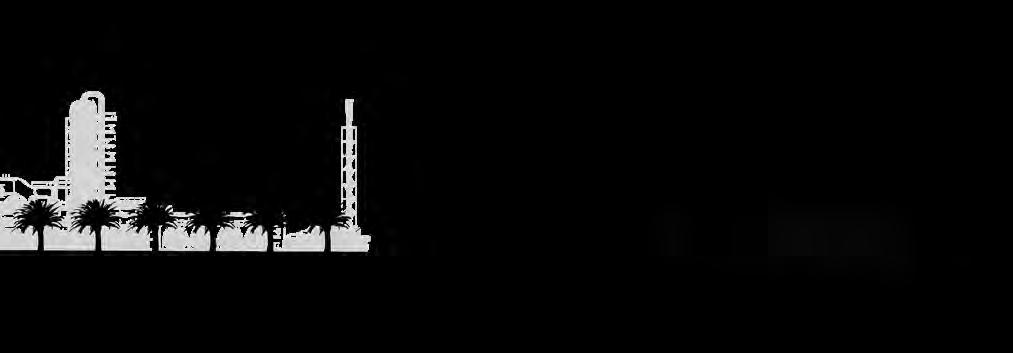

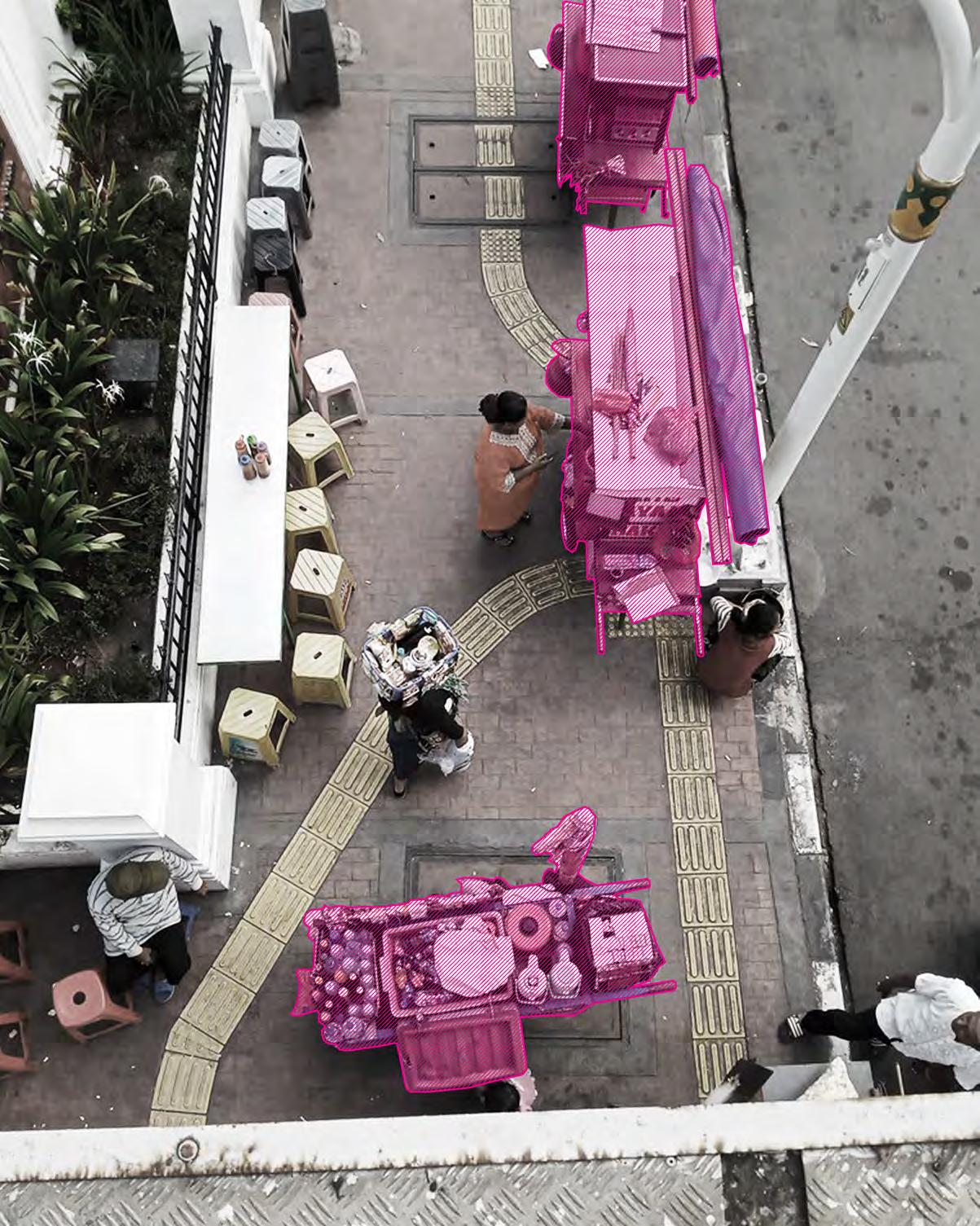

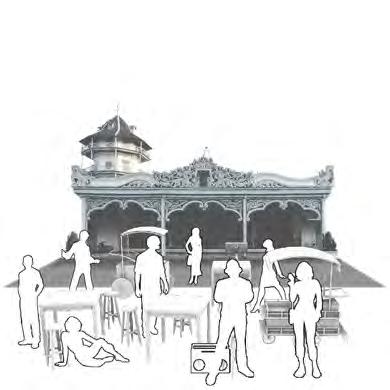

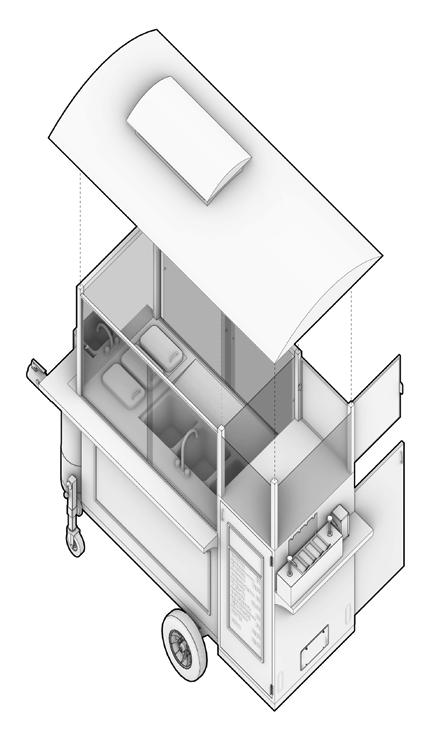

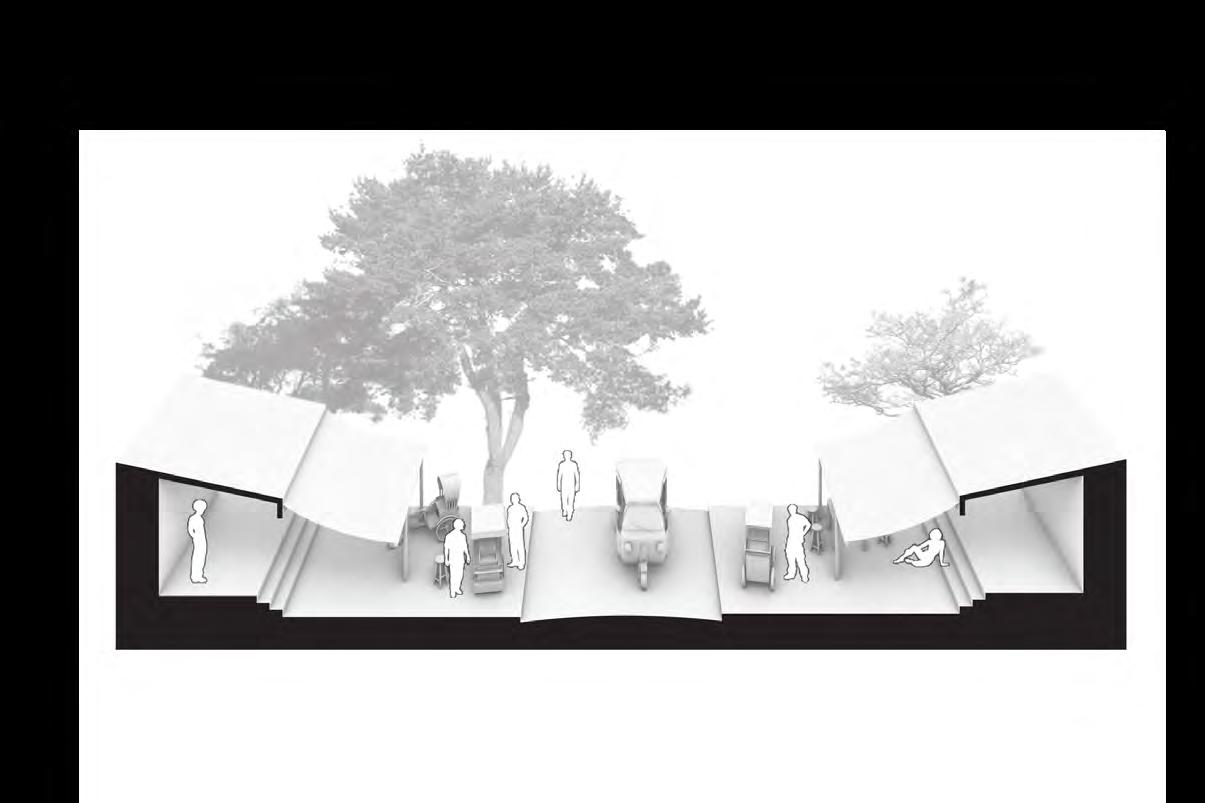

Mangroves & Palm Plantation The Great Garuda & Land Reclamation Street Vendor & Formalization

348

Medellin Metropolitan Area

The Metrocable Jardin Circunvalar de Medellín The River that is Not

004 Iceland

Runways to Greenways Vik Campsite Reykjavik Municipal Plan 2010-2030

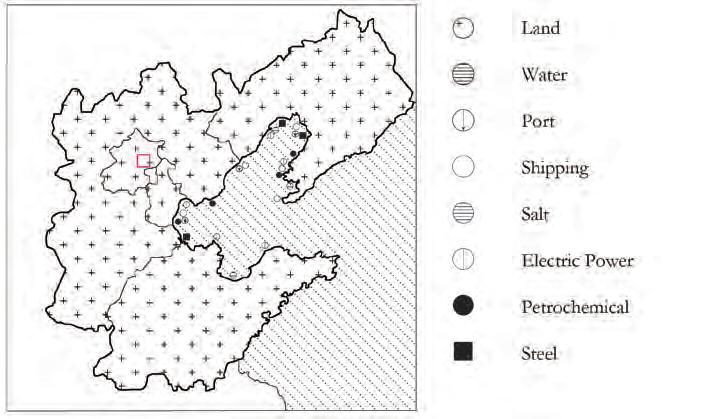

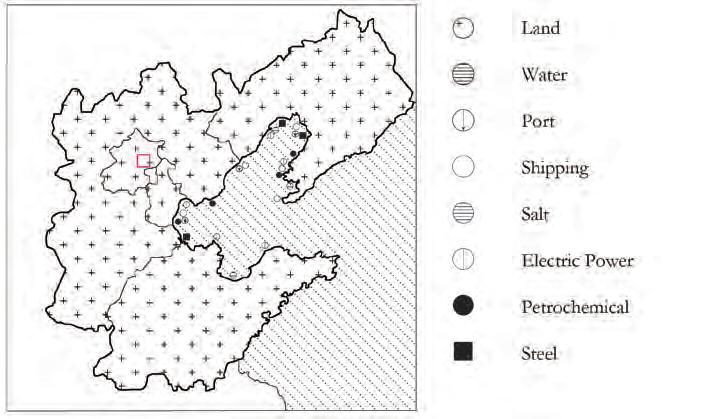

090 Bohai Economic Rim

Jiaozhou Bay Bridge and Tunnel Qinhuangdao Beach Restoration 798 Art District

178 Ganges Basin

Kumbh Mela Maidan Kashi Vishwanath Corridor

288

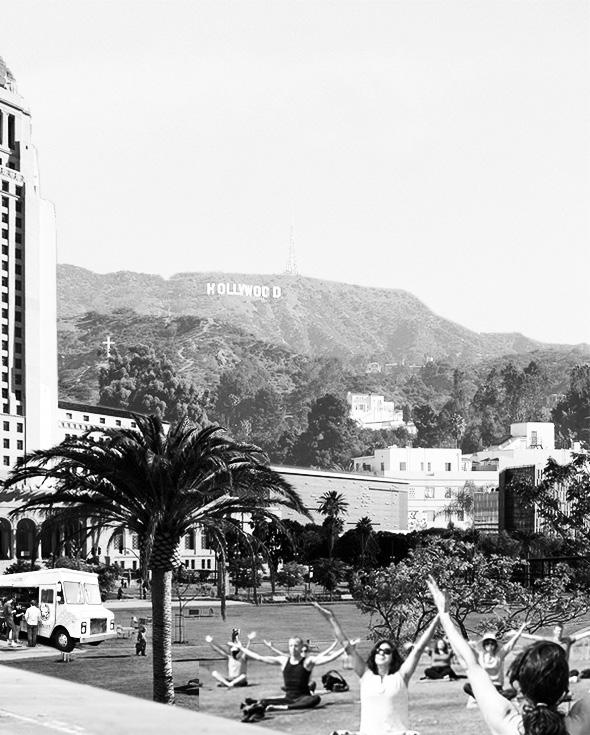

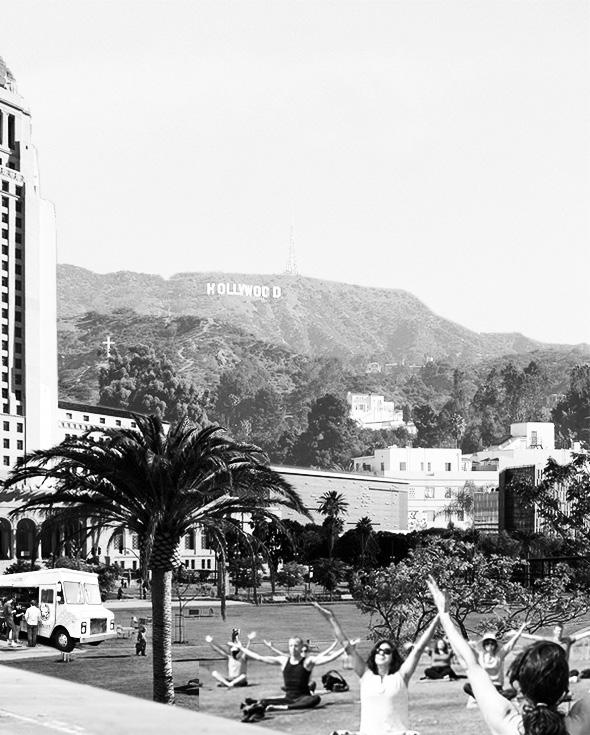

Metropolis Los Angeles

Fab Civic Center Park One Santa Fe Elysian Park Heights

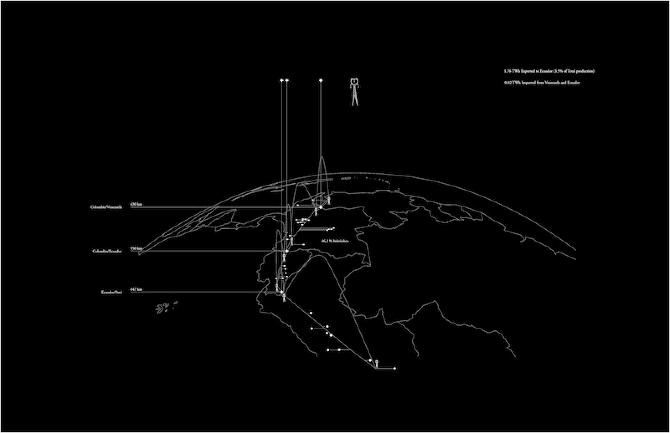

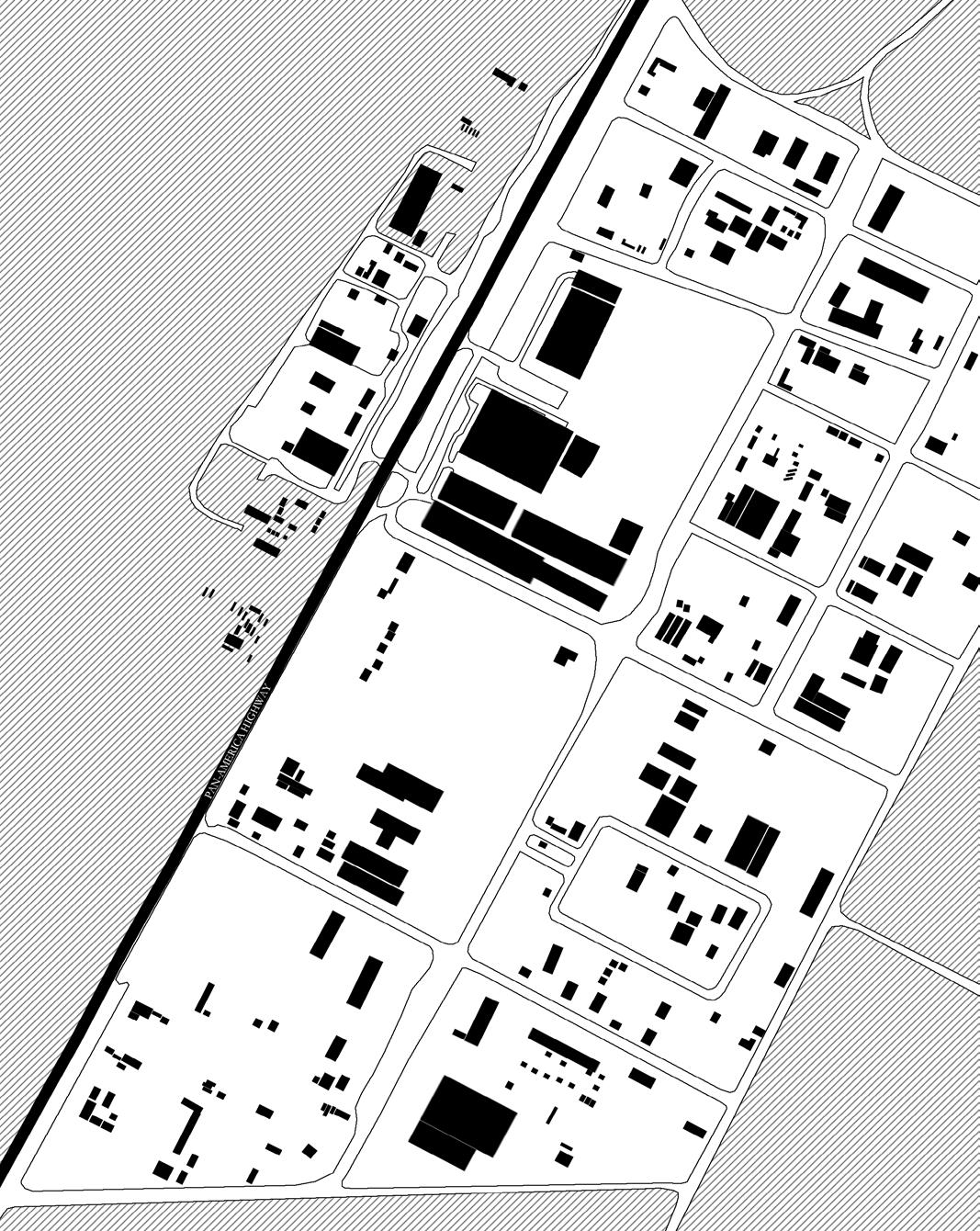

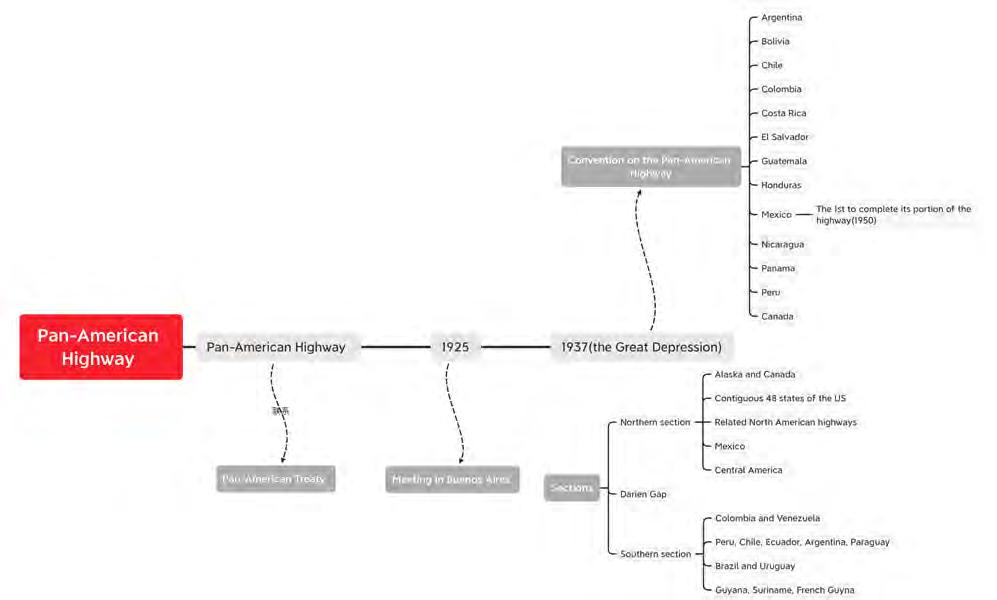

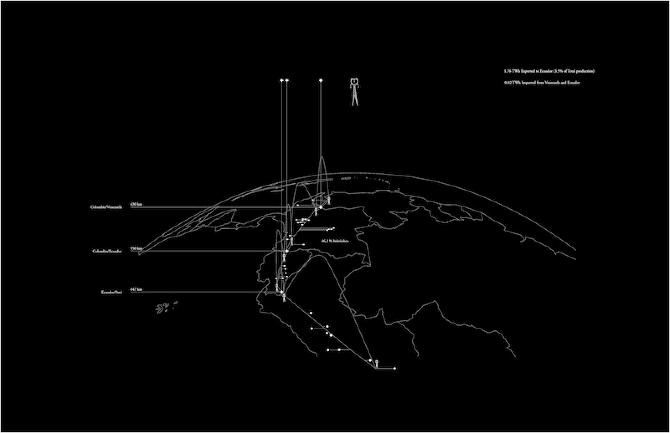

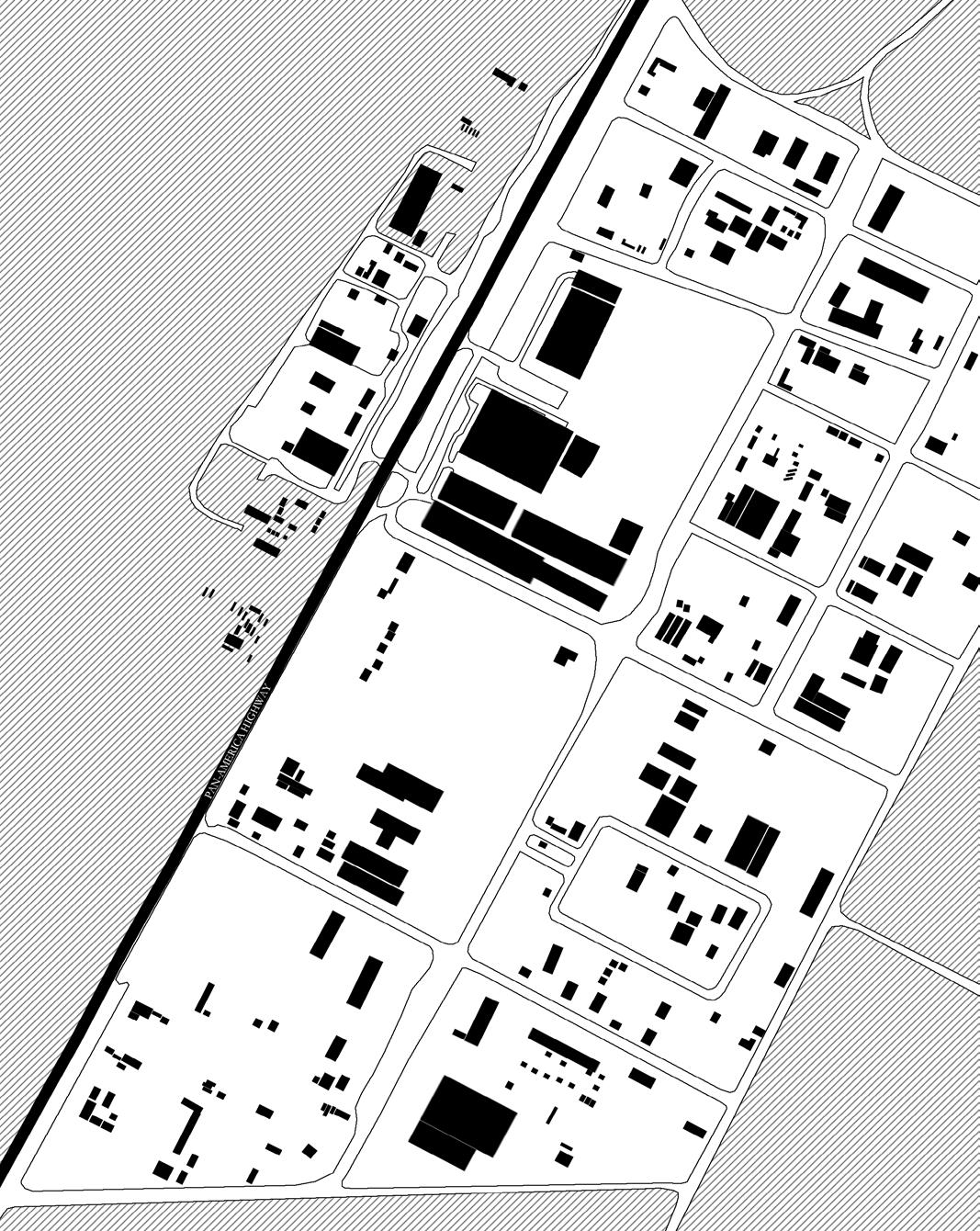

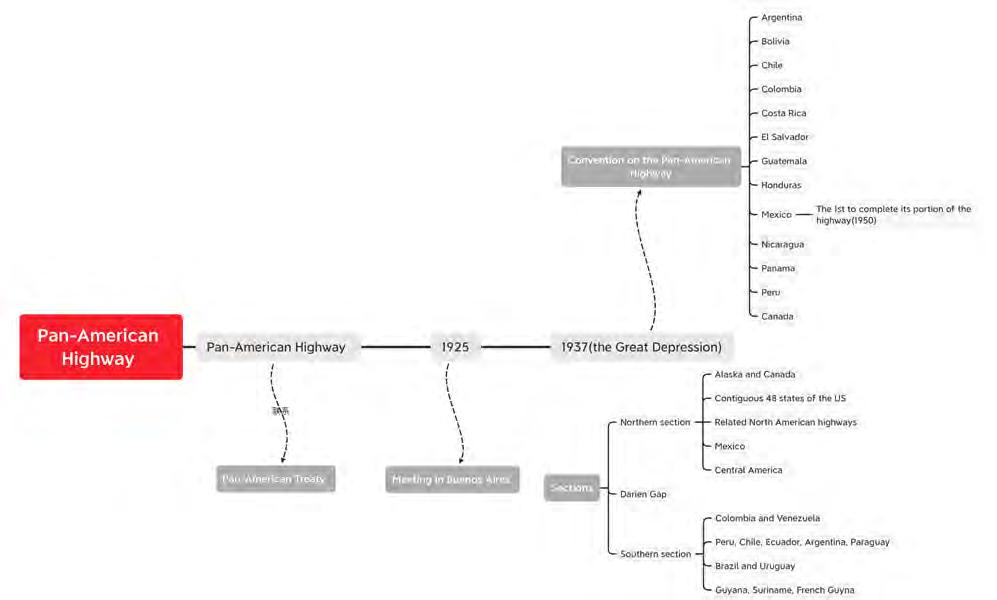

378 South American Infrastructural Integration

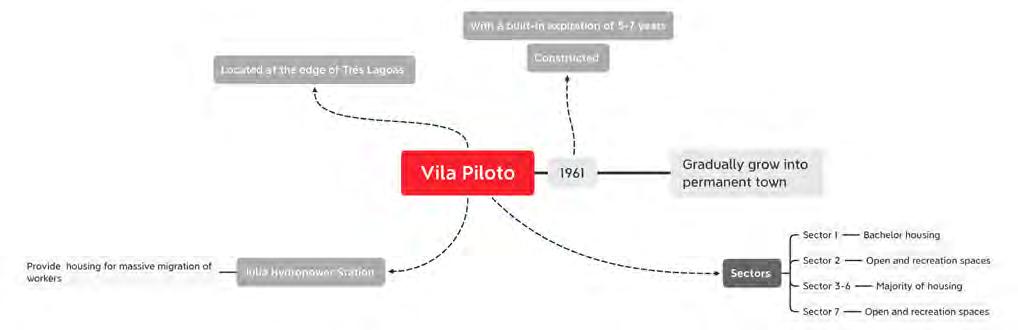

Pan-American Highway Maria Elena Vila Piloto

Contents A-1

CONTENTS

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-2 Iceland Iceland Medellin Metropolitan Area Colombia

Economic Rim

St Clair Watershed United States & Canada South American Infrastructural Integration South America

Los Angeles United States

Bohai

China Lake

Metropolis

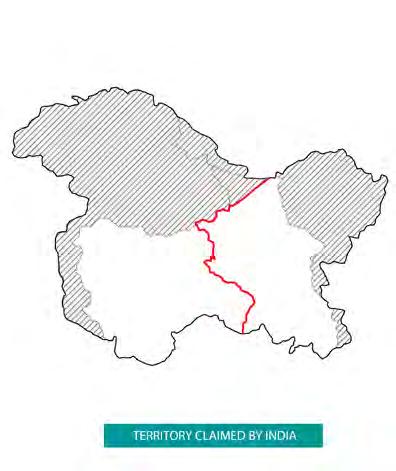

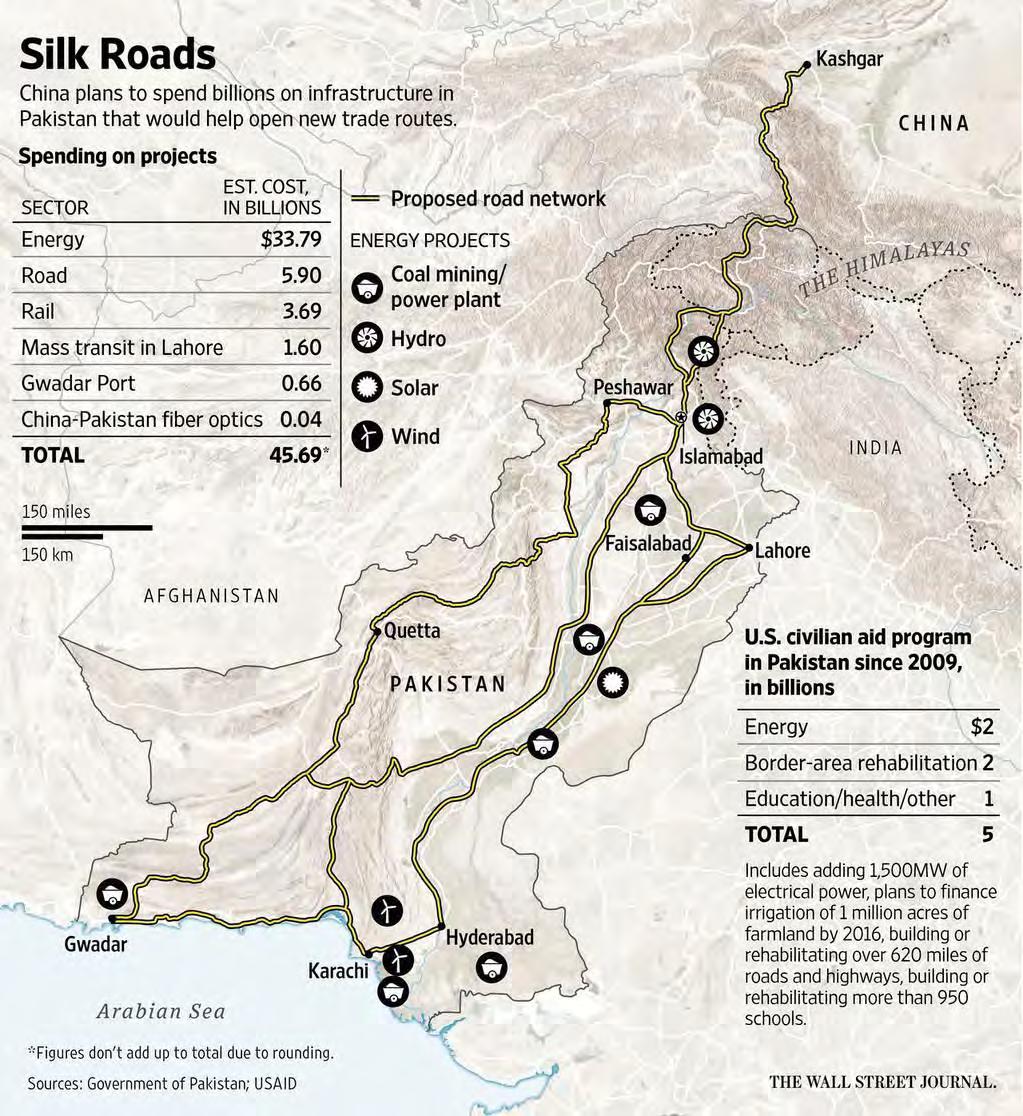

Kashmir

Enclaves within India, Pakistan and China

Sichuan China

Ganges Basin India

Singapore Singapore

Indonesian Archipelago Republic of Indonesia

Papua New Guinea

Est Timor

Ruhr Valley Germany

Southern Nigeria Nigeria

Collective Map A-3

01 IDENTIFICATION OF THE TERRITORY AND LOCATION

Iceland is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic, with a density of 0.3 km2 per citizen, making it the most sparsely populated country in Europe1. Although Iceland was isolated for centuries from the rest of the world, today it is a trade-transit station between the American and European continents. Iceland joined the European Economic Area and became a Schengen country, but is not part of the European Union.

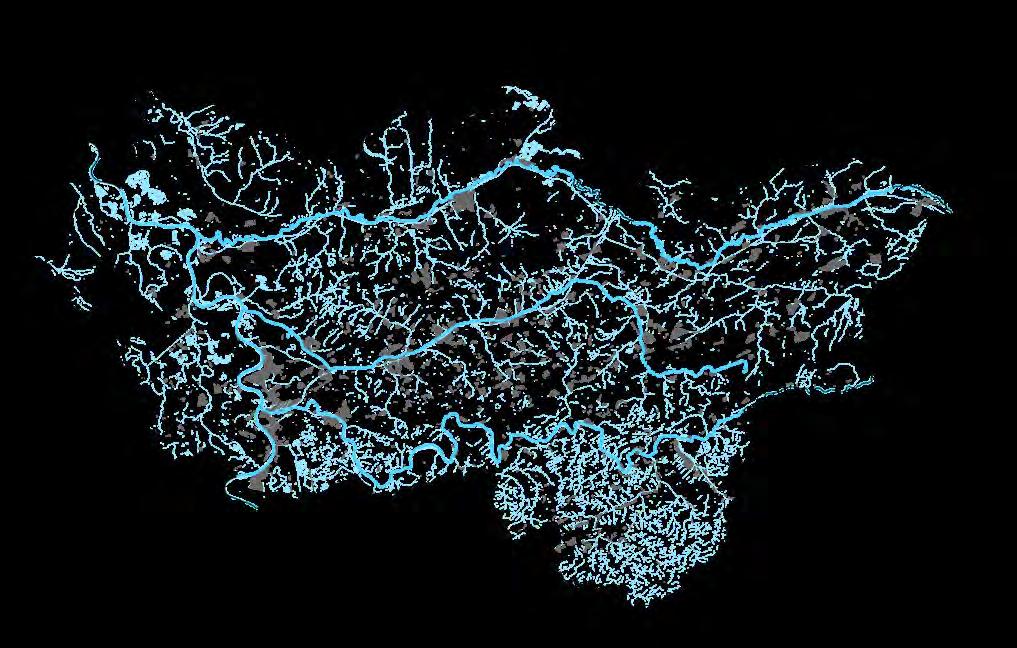

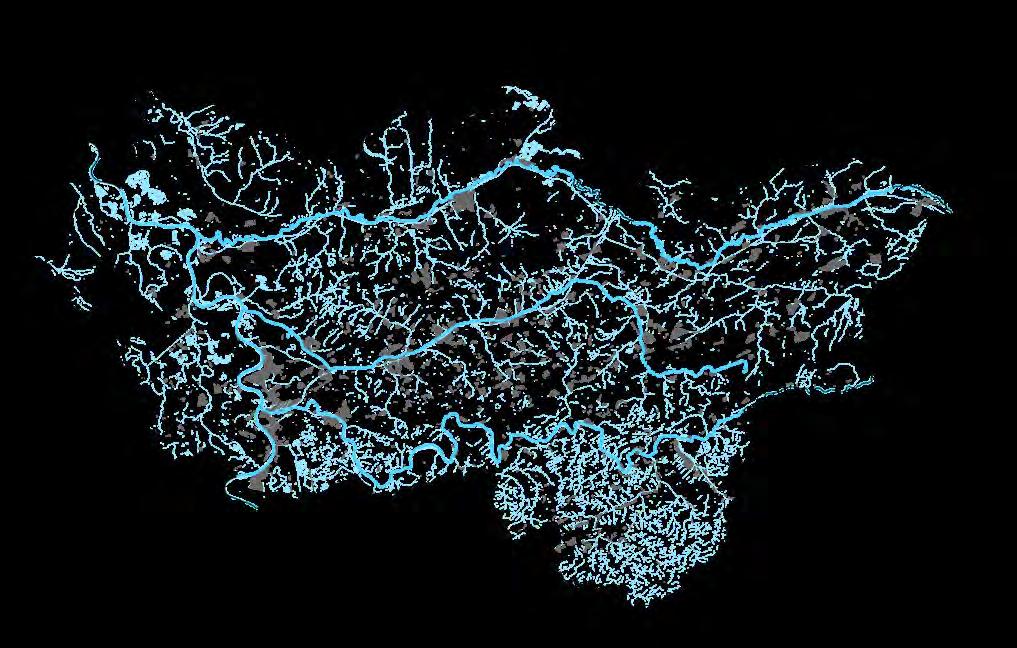

Iceland is a bowl-shaped highland, surrounded by coastal mountains and a plateau in the middle. More than 100 volcanoes punctuate the island and the Öræfajökull is the tallest peak in the country, with an altitude of 2110 meters2. This country is built on volcanic rocks, and most of the land cannot be reclaimed, which has not been conducive to agricultural development in the past. Thus, most of the population is concentrated along the southwest coast, supported by fishing. The volcanoes provide abundant geothermal energy and the natural scenery attracts tourists3. The river flows outward from the central plateau in a radial pattern, and there still exist modern glaciers, covering 11.5% of the island. Iceland has Vatnajokull, the third largest glacier in the world. However, the country is facing the grave issue of melting ice due to global warming4

1. “Population, Total - Iceland.” Data. Accessed March 26, 2020. https:// data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP. TOTL?locations=IS&view=chart.

2. Reynarsson, Bjarni. “The planning of Reykjavik, Iceland: three ideological waves-a historical overview.” Planning Perspectives 14, no. 1 (1999): 49-67.

3. Edda. “The Biggest Volcanoes in Iceland.” Perlan, July 19, 2019. https://perlan.is/thebiggest-volcanoes-in-iceland/.

02 RELEVANCE FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF URBAN DESIGN THEORY AND PRAXIS

Iceland has a short history of urban development as the island only industrialized in the late nineteenth century due to its isolation, colonial status, and self-supporting economy. Influenced by Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow, Guðmundur Hannesson, the Professor of Medicine, at the University of Iceland, published ‘On Town Planning’, in 1916. It remains a relevant book in Iceland’s urban planning history5 .

Iceland is near the Arctic Circle, with many hot springs, fumaroles, and

4. Halldórsdóttir, Katrín. “Densification as an Objective Towards Sustainable Planning in Reykjavik. Case Study: A Redevelopment Plan for the Ellidaarvogur Area.” PhD diss.

5. Reynarsson, Bjarni. “The planning of Reykjavik, Iceland: three ideological waves-a historical overview.” Planning Perspectives 14, no. 1 (1999): 49-67.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-4

ICELAND

[Critical DATA]

Geographical Delimitation

Iceland is at the juncture of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. The country lies between latitudes 63 and 68°N, and longitudes 25 and 13°W.

Area 103,000 km²

Population

353,574 [as of 2018]6

Social Indicators

Iceland is almost entirely urban with half of the population located in and around the capital Reykjavik. The educational system is very developed, with about 100,000 students nationwide, 1 /3 of the population. Iceland is the most gender-equality practiced country in the world7.

Economic Indicators

The second half of the 20th century saw substantial economic growth driven primarily by the fishing industry. The economy diversified greatly after the country joined the European Economic Area in 1994, but Iceland was especially hard hit by the global financial crisis in the years following 2008. The economy is now on an upward trajectory, fueled primarily by a tourism and construction boom. Literacy, longevity, and social cohesion are first rate by world standards7.

Environmental Indicators

Iceland is situated on top of a hotspot, which provides geothermal energy for sustainable development. And hydropower produces electric power with efforts in developing public transportation. And Iceland has been using its resources for green power generation and has built many geothermal power stations and dams for hydropower stations to mitigate the risk of climate change7

6. “Population, Total - Iceland.” Data. Accessed March 26, 2020. https:// data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP. TOTL?locations=IS&view=chart.

7. “The World Factbook: Iceland.” Central Intelligence Agency. Central Intelligence Agency, February 1, 2018. https://www.cia. gov/library/publications/resources/the-worldfactbook/geos/ic.html.

Iceland A-5

ICELAND

Figure 01. World Map

8. “Climate Change.” Go to frontpage. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://www.government. is/topics/environment-climate-and-natureprotection/climate-change/.

9. Welling, Johannes, Rannveig Ólafsdóttir, Þorvarður Árnason, and Snævarr Guðmundsson. “Participatory Planning Under Scenarios of Glacier Retreat and Tourism Growth in Southeast Iceland.” Mountain Research and Development 39, no. 2 (2019).

10. Green, Jared. “Iceland Blends Renewable Energy into the Landscape.” THE DIRT, August 8, 2019. https://dirt.asla. org/2018/10/23/icelands-landscape-policyminimizes-the-visual-impact-of-renewablepower/.

11. Lenhart, Maria, Skift, Andrew Sheivachman, Raini Hamdi, and Skift. “The Rise and Fall of Iceland’s Tourism Miracle.” Skift, September 11, 2019. https://skift.com/2019/09/11/the-riseand-fall-of-icelands-tourism-miracle/.

12. “The Country That Tourism Has Taken by Surprise.” BBC Future. BBC, February 22, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/future/ article/20170222-the-country-that-tourism-hastaken-by-surprise.

13. Liang-Pholsena, Xinyi, Rosie Spinks, and Skift. “Why Iceland’s Tourism Boom May Finally Be Over.” Skift, January 17, 2019. https://skift.com/2019/01/16/why-icelandstourism-boom-may-finally-be-over/.

volcanoes. At the same time, Iceland is facing grave threats of increased carbon emissions. Almost all of Iceland’s glaciers are receding, and scientists predict that they may largely vanish in the next 100-200 years8. For example, since the start of this millennium, the southeast outlet glaciers of Vatnajökull have retreated rapidly; according to Hannesdóttir and Baldursson (2017), their mass loss per unit area is among the highest in the world9. Working toward preparedness for climate change, Icelanders relay on the geothermal heating systems in many cities, which can be considered as a massive infrastructure project in the state protecting the environment through diminished carbon dependency. The capital city Reykjavik, for example, has 370 miles of hot water pipes. Hot water from ten districts of the capital comes from four geothermal zones, and ten automated hot water stations provide hot water and heating for urban dwellers. These energy sources save billions of dollars each year, and play an essential role in mitigating the risk of climate change.

However, Iceland’s geothermal systems are expanding with intense public protests that claim the systems are destroying the stunning landscape. In 2016, landscape architect and urban planner Björk Guðmundsdóttir proposed a new landscape policy designed to create a more harmonious relationship between land and energy10. Eventually, she settled on a series of design guidelines, simple but with a positive impact on new projects, and created new roles for landscape architects and urban designers to focus on land issues brought by the energy.

Tourism is a significant pillar of the Icelandic economy. Tourism revenue now accounts for 42 percent of Iceland’s economy in 2019, an increase from around 27 percent in 2013, according to Statistics Iceland11. Iceland has lacked major construction since the end of World War II. The sudden influx of tourists has also increased the demand for public transport and infrastructure construction. In recent years, new hotels, restaurants, roads, and supporting infrastructure are rapidly developing12. But for Iceland, which has a total population of 3.5 million, faced 2.3 million tourists in 201813. That’s why so many campsites for tourism appeared in rural areas along the coastline with perfect natural scenery recently.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-6

Figure 02. Hot Springs and Cultural Spots in Iceland

2020 2010

Reducing 12% CO2 emissions under global warming.

Iceland is the first country to sign a free trade agreement with China.

Grímsvötn eruption interrupted airlines in whole Europe for one week.

Icelandic financial crisis boomed due to influence from all over the world. Iceland’s systemic banking collapse was the most extensive experienced by any country in economic history.

Iceland joins the European Economic Area.

Third Cod War with British for 200 nautical miles.

Second Cod War with British for 50 nautical miles.

Iceland joins Nordic Council.

First Cod War with British for 12 nautical miles.

The immediate post-war period(World War II) was followed by substantial economic growth, driven by industrialization of the fishing industry and the US Marshall Plan program.

Iceland formally became a republic country. And the first president is Sveinn Björnsson.

The Althing replaced the King with a regent and declared that the Icelandic government would take control of its own defense and foreign affairs during World War II.

Iceland became a fully sovereign and independent state in a personal union with Denmark.

Denmark granted Iceland a constitution and limited home rule. Moreover, Hannes Hafstein served as the first Minister for Iceland in the Danish cabinet.

Icelandic Commonwealth belonged to Denmark after the Napoleonic Wars.

Icelandic Commonwealth belonged to Denmark–Norway.

People built their homesteads in present-day Reykjavík and established Icelandic Commonwealth, Norwegian-Norse chieftain Ingólfr Arnarson.

Iceland was be found by Swedish Viking explorer Garðar Svavarsson.

Iceland A-7

1900 1940 1950 870 1970 2000

HISTORY, ACTORS

1990 1940 1918 1971 1975 1994 2008 2011 2014 2030 874 1262 1814

TIMELINE :

AND EVENTS

1874

1944 1945

1958

1200 1800

Figure 03. Nautical Area of Three Cod Wars

Figure 04. Norsemen landing in Iceland in 872

Right now, the disappearance of glaciers is developing large-scale glacier tourism. In the town of Húsafell, about 90 minutes from Reykjavik, a sustainable and hospitable campsite attracts both international tourists and Icelandic families to glacier and lava cave tours. Environment and tourism experts from University of Iceland are using participatory scenario planning (PSP) to explore adaptation planning for recreational sites near melting glacier areas. Their study demonstrated that PSP can be a valuable tool to support recreational land-use planning in glacial landscapes, and to improve anticipatory adaptation to potentially undesirable future changes14

03 METHODS TO CONDUCT YOUR INVESTIGATION

The database from The World Bank, The Central Intelligence Agency and other articles provide insights on the environment, economy, policy, and history of Iceland with objective and rational recolonization. Specifically, the data of CO2 emissions presented that Iceland’s carbon emissions have been decreasing year by year, indicating that sustainable construction has been practical. I will research ecological projects to explore how Iceland adapts to climate change.

Google Earth and photographs will provide a lens to three-dimensional Iceland. For technique, I will use OpenStreetMap and GIS for mapping and continue my study on Iceland’s topography.

Online news and social media illustrates that tourism development has played a decisive role in recreational land-use planning. Researching critiques will help me analyse Iceland’s campsites.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-8

14. Welling, Johannes, Rannveig Ólafsdóttir, Þorvarður Árnason, and Snævarr Guðmundsson. “Participatory Planning Under Scenarios of Glacier Retreat and Tourism Growth in Southeast Iceland.” Mountain Research and Development 39, no. 2 (2019).

Figure 05. Community in Reykjavik

05 ANTICIPATED FINDINGS

Three case studies will illustrate the importance of sustainable development in Iceland under the crises of the climate change--runways to greenways, Vik campsite, and ReykjavIk Municipal Plan 2010-2030.

Three cases illustrate different ways under the crises of global warming. The first case, which is related to ecological urbanism, introduces environmental strategies in renovating abandoned areas and supporting services for the nearby community. The second case illustrates ephemeral urbanism, an approach of protecting the environment against tourism development. And for the third one, I will attempt to discuss climate change mitigation.

Iceland A-9

Figure 06. Landscape in Iceland

0 1 mile

SITE

Figure 07. Aerial view of the Runways to Greenways

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-10

Location Year(s) Status Footprint Designer

Additional Agents

Key Project Components Program(s)

Key Project Components Program(s)

Funding Streams

RUNWAYS TO GREENWAYS [ECOLOGICAL URBANISM]

A 2007 international competition organized by capital Reykjavik invited architects, urban designers, and planners to discuss the future of an abandoned World War II airfield and its surrounding 150 hectares, located Vatnsmyri15. The Runways won the first prize and proposed a city, self-sufficient with respect to energy, agriculture, water, while addressing the development potentials of technological enterprises for the region.

[Reykjavik, ICELAND]

[2007]

[Unbuilt]

[N/A]

[Lateral Office]

[The site is a defunct World War II runway established by the Americans.]

[The three large greenways are programmed as: ecology, recreation, and production.]

[This area is mainly divided into four quadrants, which correspond to 4 primary urban block typologies: permeable perimeter block, porous folded block, stacked campus and pixelated residences. ]

[Public]

0 1 mile Administration Area Road River Iceland A-11

15. WHITE, MASON, and LOLA SHEPPARD. “Productive Urbanisms.”

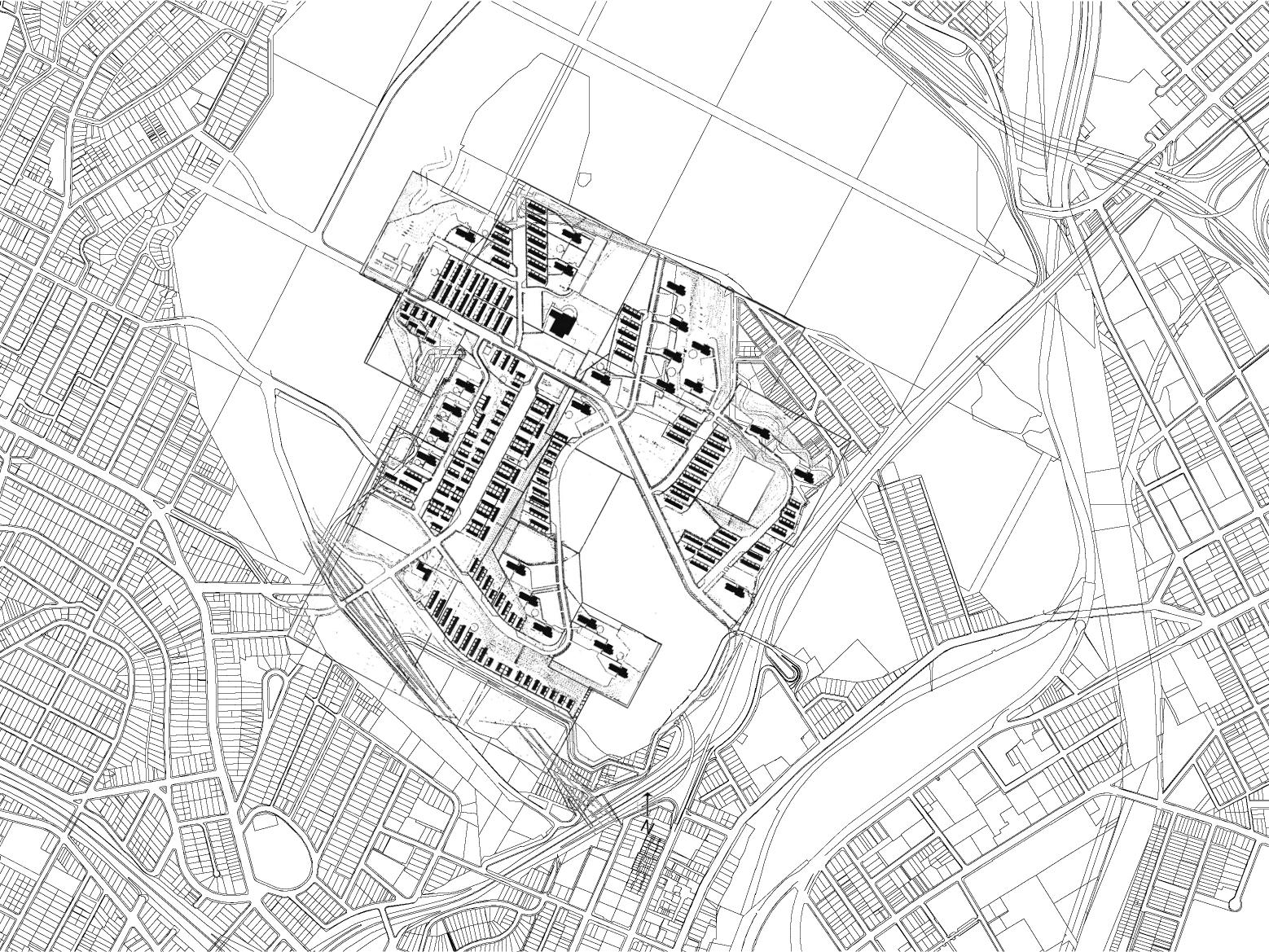

Figure 08. Cartography of the Runways to Greenways

THE RUNWAYS TO GREENWAYS AND THE ECOLOGICAL URBANISM

Runways to Greenways, an urban design proposal for the Vatnsmýri area of Reykjavik, aims at reusing three defunct World War II runways and looks forward to new public space and ecological regeneration strategies. The project establishes “no-build” zones and public landscapes. The figure of the runway is used to identify three primary axes. Three former runways are converted into a “greenway” programmed as: ecology, recreation, and production16.

Matthew Gandy mentions, “ecological urbanism deals with urban design in terms of methodology”17and this project depends on a strategy that considers energy use, ecology and land use when integrating public amenities. The premise of the project is to use ecology as a catalyst for urban development. This proposal identifies exterior space as equally charged with activity, use, and event as built or interior spaces. The objective of this project is to propose a city that is selfsufficient in terms of energy, agriculture and water for ecological urbanism in Vatnsmyri area18. The integrated infrastructure calls for a symbiotic relationship between ecological urbanism and nature, and between energy consumption and production in an effort to pair infrastructure, landscape, public amenities and architecture in a culturally, economically and environmentally productive urban realm. For example, production greenway is a program centered on economies of food and energy production. It capitalizes on the benefits of abundant energy and a tradition of high-tech agriculture, to propose a productive landscape within the center of the city, both eliminating local transport and putting people in direct contact with food and energy production19

While form and program are carefully considered, unfortunately, this project lacks a more in-depth exploration of ecological urbanism in terms of economy and social strategies for connecting with the city.

16. ATERAL OFFICE. Accessed March 27, 2020. http://lateraloffice.com/filter/Energy/ RUNWAYS-GREENWAYS-2007-08.

17. Gandy, Matthew. “From urban ecology to ecological urbanism: an ambiguous trajectory.” Area 47, no. 2 (2015): 150-154.

18. Waldheim, Charles. Landscape as urbanism: A general theory. Princeton University Press, 2016.

19. WHITE, MASON, and LOLA SHEPPARD. “Productive Urbanisms.”

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-12

Figure 09. Rendering of Runways to Greenways

0

Ecology

Figure 10. Figure Ground Plan of the Runways to Greenways

1/4 mile

Production Recreation Corridor Iceland A-13

Theories

and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-14

Figure 12. Taxonomy of the Runways to Greenways

Runways figure

Greenways figure

Figures superimposed

Figure 11. Transect of the Runways to Greenways

Runway New Block Iceland A-15

Source Intended User Winner Policy Propose Phase Vatnsmyri Masterplan Design

City Vatnsmyri Area Government Phase I (selected); Phase II Lateral Office Citizen

Figure 13. Actors of the Runways to Greenways

Initiator Fund

Competition

Theories

and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-16

Figure 14. Collage of the Runways to Greenways

Iceland A-17

0 1/2 mile SITE

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020

A-18

Figure 15. Aerial view of the Vik Campsite

20. “Www.vikcamping.is.” www.vikcamping. is. Accessed March 27, 2020. http://www. vikcamping.is/.

VIK CAMPSITE [EPHEMERAL URBANISM]

Camping is cheap, but is also a good way to experience nature and has a lower impact on the environment. The high tourist season in Iceland is from late May to August and campsites will be extremely crowded during this time with both vans and tent campers. However, some campsites are only open from spring to early fall20.

Location Year(s) Status

Footprint Designer

Additional Agents

Key Project Components Program(s)

Funding Streams

[Vík í Mýrdal, ICELAND]

[2018]

[Ephemeral]

[N/A]

[Vik Camping]

[The campsite has a capacity of 250 people and there is always a space for one more tent or car.]

[Vik campsite offers accomodation in 4 cottages at the camping ground.]

[N/A]

[Private]

0 50 mile Administration Area Road River Compsite Iceland A-19

Figure 16. Cartography of the Vik Campsite

THE VIK CAMPSITE AND THE EPHEMERAL URBANISM

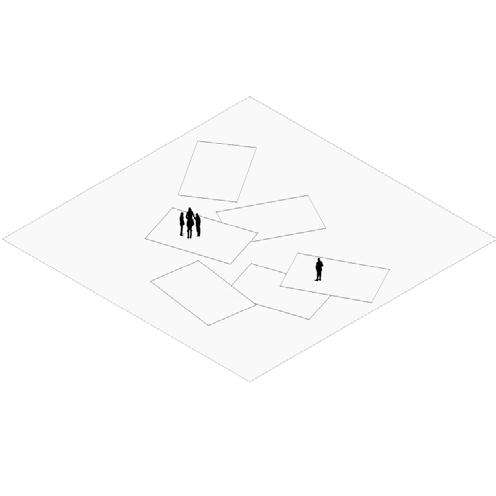

Campsites can be considered as ephemeral urbanism since this kind of construction is more like a quick response to tourism’s requisition and climatic conditions in specific seasons. Ephemeral urbanism for this project is not only about deployment and disassembly different from the characteristic of stability of the permanent hotels or Airbnbs. it is more related to the negotiation between tourists, designers, and institutions or companies for managing users’ requisitions21.It means that enough flexibility and affordability satisfying every party will make the maximum profits.

There are over 170 campgrounds in Iceland for citizens and tourists. Every village has its campground and people can camp at a specific time. Increasing numbers of tourists who damaged the environment, prompted the government to enact new laws responding to negative influence of tourism. In November 2015, new conservation legislation came into effect making changes to where it is permissible to camp22. Moreover, for protecting the environment, some campsites are only open during the hot season. For example, the Vik Campsite is an ephemeral housing region, opening from spring to early fall. Vik Campsite is located 1 km from Vik, the southernmost village in Iceland. The cottages in the site can accommodate up to 250 people in tents, cabins, cars and caravans. On the campsite, the service buildings offer most of the services required by campers, electricity, toilets, warm and cold running water, shower, WiFi and dining facilities23.

The issue is that these campgrounds are vacant without any activities or urban development during slow periods and the shoulder season. What’s worse, single land-use structure is lack of economic resilience. For example, a little decline in tourism shows how the slowdown affected the ephemeral campsites. Hotel stays were flat year-over-year, while Airbnb stays dropped 11 percent. However, campsites declined a massive 30 percent24. Under these issues, urban designers and planners should activate the vitality of campgrounds during slow periods for more flexibility and affordability.

21. Mehrotra, Rahul, and Felipe Vera. “Ephemeral urbanism: Looking at extreme temporalities.” In In The Post-Urban World, pp. 44-55. Routledge, 2017.

22. “May I Camp Anywhere?” Umhverfisstofnun. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://www.ust.is/2016/06/30/May-I-campanywhere-/umhverfisstofnun/frettir/stokfrett/.

23. “Www.vikcamping.is.” www.vikcamping. is. Accessed March 27, 2020. http://www. vikcamping.is/.

24. Lenhart, Maria, Skift, Andrew Sheivachman, Raini Hamdi, and Skift. “The Rise and Fall of Iceland’s Tourism Miracle.” Skift, September 11, 2019. https://skift.com/2019/09/11/the-riseand-fall-of-icelands-tourism-miracle/.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-20

Figure 17. Vik Campsite

0 1/4 mile 0 1/4 mile Iceland

Park Sea Forest Water Building Non-tourist Season High Tourist Season Tent RV

A-21

Figure 18. Figure Ground Plan of the Vik Campsite

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter

A-22

2020

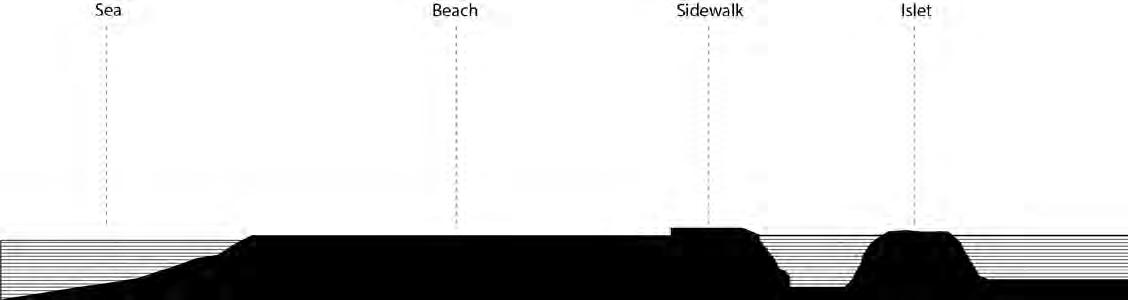

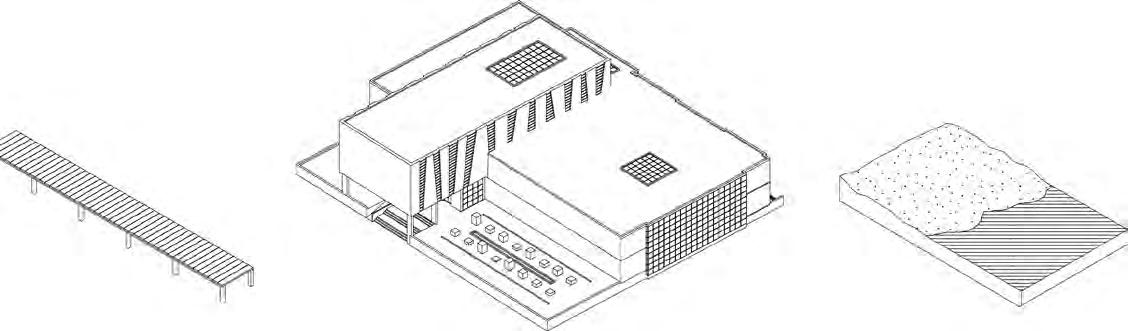

Figure 19. Transect of Vik Campsite

Cottage Service RV Tent

Figure 20. Taxonomy of Vik Campsite

Cottage

Owner Fund Source Tool Intended User Policy Private Private Property Vik Government Tourist and Citizen Private tent and RV Iceland A-23 Tent Service

Figure 21. Actors of Vik Campsite

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-24

Figure 22. Collage of Vik Campsite

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-24

Figure 22. Collage of Vik Campsite

Iceland A-25

0 1 mile SITE

Figure 23. Aerial view of Reykjavik

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-26

25. Daniels, Andrew. “Iceland’s Radical Plan to Slow Climate Change.” Popular Mechanics. Popular Mechanics, May 9, 2019. https://www. popularmechanics.com/science/green-tech/ a27410266/iceland-fighting-climate-changecarbon-storage/.

26. Halldórsdóttir, Katrín. “Densification as an Objective Towards Sustainable Planning in Reykjavik. Case Study: A Redevelopment Plan for the Ellidaarvogur Area.” PhD diss.

REYKJAVIK MUNICIPAL PLAN 2010-2030 [CRISIS URBANISM]

Iceland is experiencing climate change caused by carbon emissions, with great transformations in melting glaciers and dramatic changes in weather patterns. Iceland decided to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030. However, its carbon emissions actually rose by 2.2 percent from 2016 to 201725. To decline carbon emissions in Reykjavik, urban planners proposed the Municipal Plan for Reykjavik between 2010 and 203026.

Location Year(s) Status Footprint Designer

Key Project Components Program(s)

Funding Streams

[Reykjavik, ICELAND]

[2010-2030]

[In Progress]

[whole Reykjavík]

[Gísli Marteinn Baldursson and his colleages]

[Traffic plan for public transportation] [Spot On] [Public ]

0 2 mile Administration

Road

Iceland A-27

Area

River

Figure 24. Cartography of Reykjavik

THE REYKJAVIK MUNICIPAL PLAN 2010-2030 AND THE CRISIS URBANISM

There are two proposals for reducing carbon emissions in Reykjavík. The first one proposes radical changes in earlier policy on the development and evolution of transport in order to deal with the issue of climate change27. Only 17.8 percent of Icelanders used public transport regularly in 2014, according to figures from Statistics Iceland. This plan for public transportation development will reduce 12% CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita). Compared to the traditional approach of increasing the road capacity, the proposal minimised traffic delays during peak periods. The main emphasis is placed on encouraging other means of transportation than the private car and thus minimise motor traffic and the pressure it puts on the street system28. For the transportation caused by tourism, the main criterion is to hold back the increase of traffic by encouraging change in tourists’ travel habits. This proposal should result in only an insignificant increase in car traffic during the planning period despite the increase in population and jobs.

Moreover, the Municipal Plan also proposes sustainable neighbourhoods, creating more green space and ecological community for absorbing carbon emissions29. Moreover, It seems that the crisis of climate change can then provide dramatic urban recoveries. This proposal will strengthen the nature, landscape and recreational areas of the city as part of a better quality of life and improved public health for residents. For example, foresting the island with native birch trees in Geldingane simultaneously preserved the area as a green space and provided a carbon sink for the city.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-28

Figure 25. Diagrams of Reykjavik Municipal Plan 2010-2030

27. Hokoda, Emma. “Three Land Use Proposals for Geldinganes Framed by the City of Reykjavik’s Municipal Plan and Climate Neutrality Goals.” (2018).

28. Eboli, Carolina Cardoso Pera. “Urbanisation control lab: Icelandic perspective on urban planning for rapid urbanisation.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers–Urban Design and Planning 171, no. 2 (2018): 77-86.

29. Eboli, Carolina Cardoso Pera. “Urbanisation control lab: Icelandic perspective on urban planning for rapid urbanisation.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers–Urban Design and Planning 171, no. 2 (2018): 77-86.

sustainable neighbourhoods 0 1mile 0 1mile Iceland A-29 Water Water Walking Zone Riding Zone Road Road Administration Area Administration Area Public Transportation New Green Space

26.

Ground

Figure

Figure

Plan of Reykjavik

Theories and Methods of Urban

A-30

Design Winter 2020

Figure 27. Transect of Reykjavik

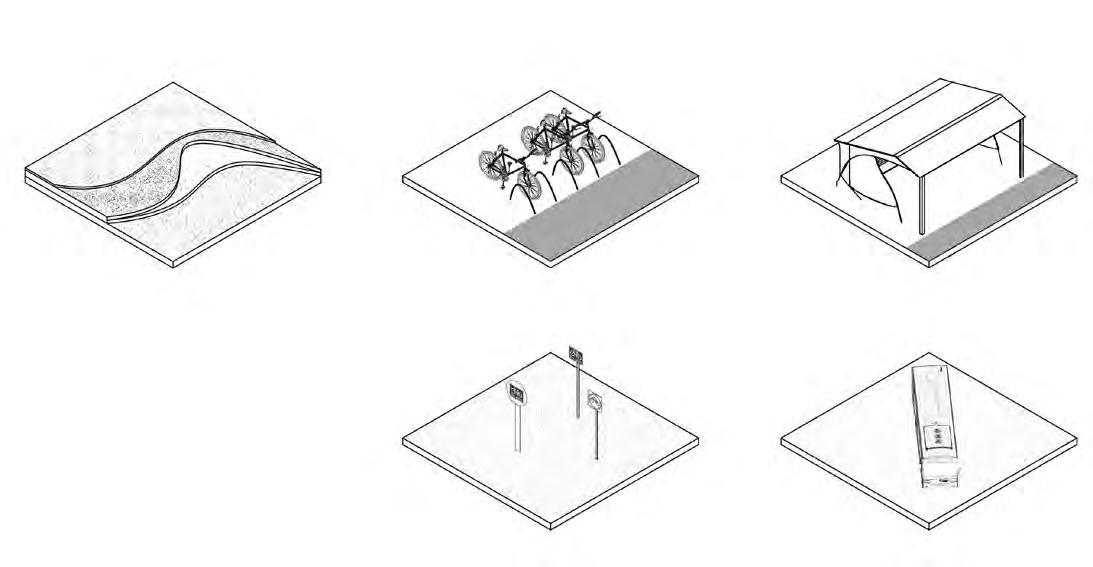

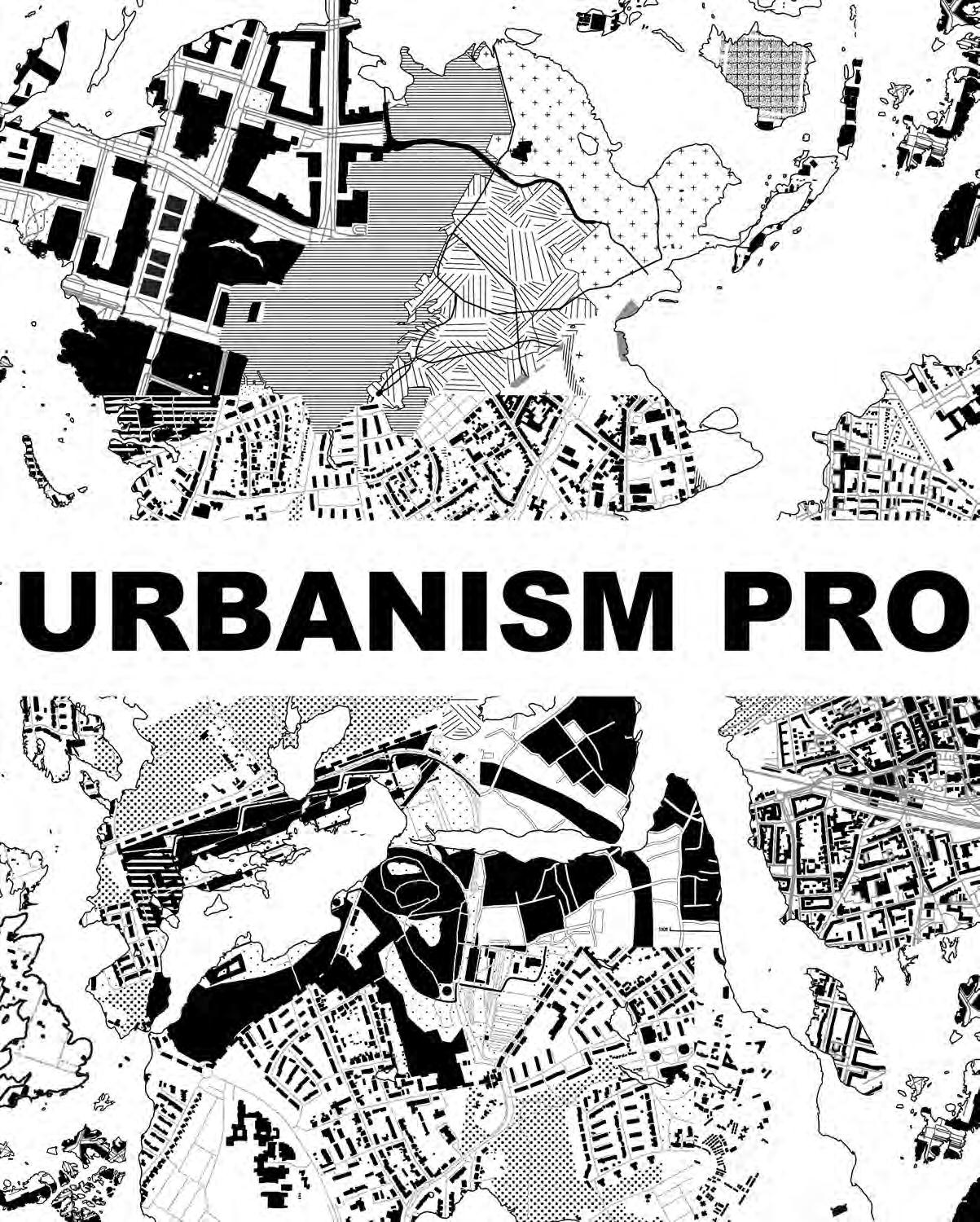

Figure 28. Taxonomy of ReykjavIk Municipal Plan 2010-2030

Green Space

Sharebike

Bike Sign

Public Bus

Bike Route

Bus Station

New Green Space

Initiator Publication Comment Fund Source Cooperation Intended User Policy Designer Environment and Planning Committee Guðjón Ó Printing Office National Planning Agency City City of Reykjavík Department of Planning and Environment 9 reports from public Citizen transportation system and landscape system Iceland A-31 Route New Green Space

Figure 29. Actors of ReykjavIk Municipal Plan 2010-2030

Theories

and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-32

Figure 30. Collage of Reykjavik

Iceland A-33

Iceland A-33

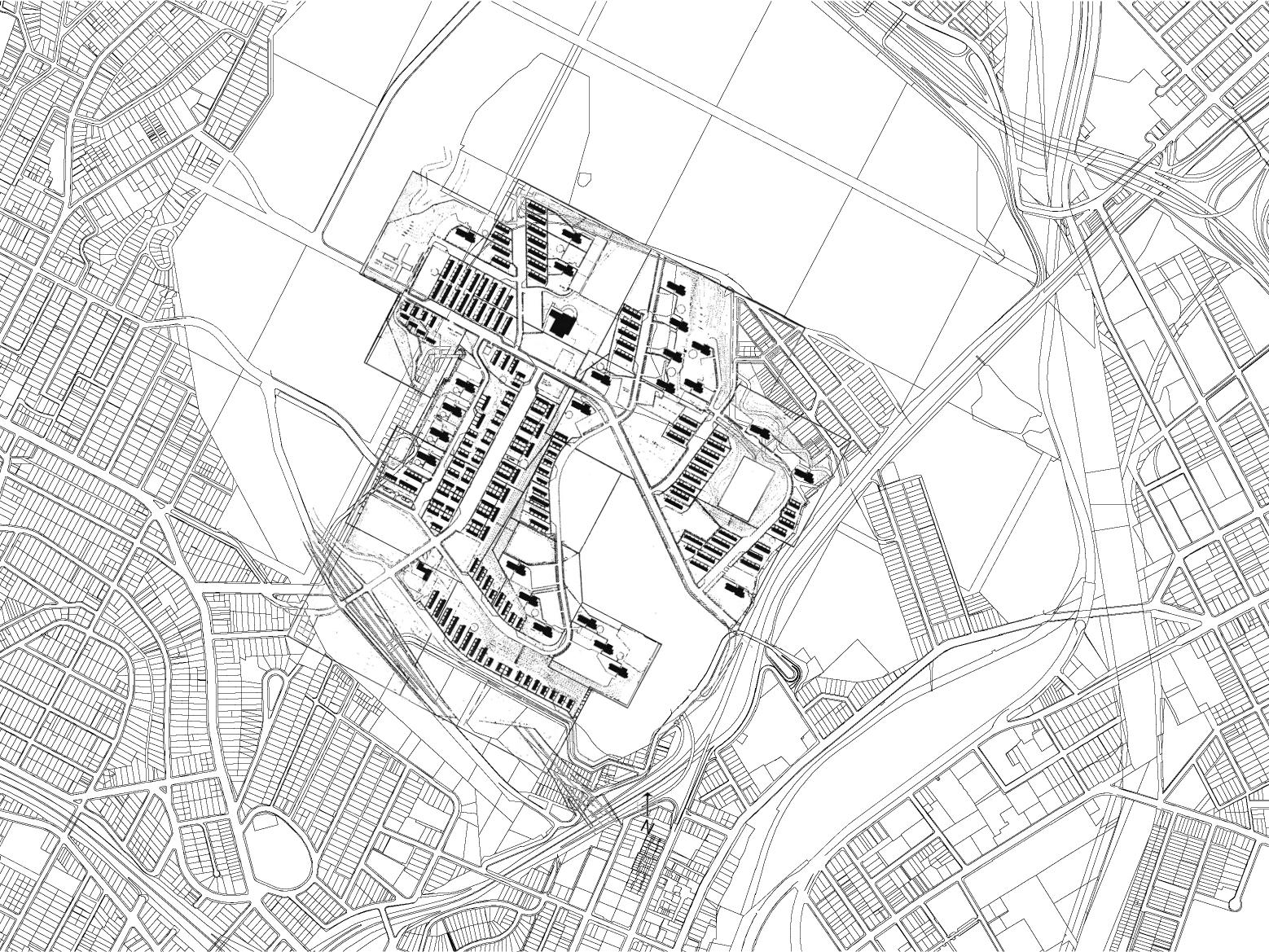

RUHR VALLEY GERMANY

01 IDENTIFICATION OF THE TERRITORY AND LOCATION

The Ruhr Valley, also known as the Ruhr Region, consists of over 53 towns and municipalities organised into a polycentric structure. With a population of over five million, the region is one of the largest metropolitan areas in Europe.1 The region lies along the course of the Ruhr River, Lippe River, and Emscher River that are the main tributaries of the Lower Rhine. The Ruhr Valley stretches 116 kilometers across from east to west and over 67 kilometers from north to south. 2

Transformed into one of the greenest areas in Germany nowadays, the Ruhr Valley has more than half of the land cover being either agriculture or green space. However, back in the mid-twentieth century, it was mining and the steel industry that dominated the Ruhr region because the natural landscape of the valley gave birth to the smaller scale mining in the first place. The industrial facilities in the area covered 200 hectares between the coal mines, the production facilities, and factories of steel and the assembly and transportation network of rails.3 The decline of the industry in the second half of the 20th century left behind a large number of areas underutilized and with high levels of pollution in both soil and water. As a result, the area was once characterized by environmental damage and low life quality.4 With the ongoing regional revitalizations, the green industry meets traditional industry heritage in the Ruhr Valley.5

1. Metropole “METROPOLIS RUHR CITY OF CITIES.” Accessed Jan. 2020. https://www. metropole.ruhr/en/

2. Hospers, Gert-Jan & Wetterau, Burkhard. Small Atlas Metropole Ruhr: The Ruhr region in transformation. 2018.

3. JOSÉ JUAN BARBA, ANDREA PORTILLO, METALOCUS, “THE EMSCHER LANDSCAPE PARK”. Accessed Jan. 2020. https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/ emscher-landscape-park

4. Gruehn, Dietwald. “Regional planning and projects in the Ruhr region (Germany).” In Sustainable landscape planning in selected urban regions, p. 216. Springer, Tokyo, 2017.

5. Hospers, Gert-Jan & Wetterau, Burkhard. Small Atlas Metropole Ruhr: The Ruhr region in transformation. 2018.

02 RELEVANCE FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF URBAN DESIGN THEORY AND PRAXIS

During the last few decades, the Ruhr Region has managed structural change towards a climate-friendly future. The actions are recognized while the coal and steel industries have been shrinking to “death” since the short peak after world war two. The changes have impacted the political structure, culture, and environment. Since the 1960s, higher education, such as universities and colleges, are invested and so do business innovation initiatives. In order to reverse the poor environmental condition and unhealthy image associated with the area, the Ruhr Valley planned the International Building Exhibition (IBA) Emscher Landscape Park, a regional greenway, to mitigate the pollution and provide recreational opportunities. The industrial remains have been reprogrammed into cultural and art incubators to accommodate the diverse cultures.6 In addition, there has been a shift from the fuel industry to renewable energy as the new focus on solar and wind power installations in populated areas. 367,400 green jobs have been created by 2010. 7

This regional case serves as a prototype from where other cities and regions that are facing similar problems can learn. The research highlights the regional scale and municipal cooperation, the role of design in providing a new imaginary for the region, and particularly, the role of the landscape and ecology in addressing transformation.

6. Keil, Andreas, and Burkhard Wetterau. Metropolis Ruhr: A regional study of the new Ruhr. Regionalverband Ruhr, 2014.

7. Gruehn, Dietwald. “Germany Goes GreenInnovations towards a Sustainable Regional Development.” World Technopolis Review 1, no. 4 (2013): 236.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-34

[Critical DATA]

Geographical Delimitation

In North Rhine-Westphalia province, Western Germany. The triangle of Duisburg-Recklinghausen-Dortmund is the heart of the region.

Area

4,439 km²

200 hectares of industrial land

39% Agricultural land, 18.3% Woodland8

Population

5 million [as of 2020] estimate to shrink to 4.8 million by 2030

Social Indicators

Major cities such as Dortmund, Essen and Duisburg have more than 500,000 inhabitants. The rest of the region remian suburb feeling density.

13 % foreigners in the region comes from nearby countries as guest workers. Refugees from Near East increase the diversity in large cities to 19% lately.9

Economic Indicators

Transform from steel-coal industry to a diverse share of education, health system, public services, retail tourism, green tech and renewable energy. Redevelopment of urban openspaces increases land values in cities. 10 Seek oppotunity as shrinking with focus on senior service.

Environmental Indicators

Ruhr River, Lippe River and Emscher River as main waterways.

18.3 % of the land is woodland which is previous to ecosystem. Retoration of Emscher River that use to be a polluted water drain.

8. Keil, Andreas, and Burkhard Wetterau. “Metropolis Ruhr.” A Regional Study of the New Ruhr. Regionalverband Ruhr, Essen 2013.

9. Hospers, Gert-Jan & Wetterau, Burkhard. Small Atlas Metropole Ruhr: The Ruhr region in transformation. 2018.

10. Gruehn, Dietwald. “Germany Goes GreenInnovations towards a Sustainable Regional Development.” World Technopolis Review 1, no. 4 (2013): 236.

Ruhr Valley A-35

Ruhr

GERMANY

Valley

Figure 01. The map of Ruhr Valley location.

Urbanisms often emerge as a response to the drastic change in society. The cases in the Ruhr Valley reflect those urbanisms such as post-industrial urbanism, landscape urbanism and ecological urbanism. The revitalization started at a postindustrial era tackling shrinkage issues. Many of the solutions use landscape as the medium to naturalize, soften, and activate the space for a more open and relaxing atmosphere. In response to pollution and degradation, restorations in all scales offer an opportunity for a culturally, economically, and environmentally sustainable future.

Back to the origin of urbanisms, it denotes a comprehensive study towards the cities, including social, environmental, and political aspects. Predecessors study the cities through observations, synthesis, and even criticisms. German sociologist Georg Simmel’s study in The metropolis and mental life 11 differentiates the meaning of city and urbanism by pointing out the social aspects related to urban life in the cities. According to the book Urbanism as a Way of Life 12, Louis Wirth tries to define characteristics of urban life and identify a framework like a sociologist. Historian Françoise Choay concludes the history of urban studies that started from industrial time and introduces urbanism as the modern stage of the studies evolved from “Regularization”, “Pre-urbanism”.13 The research not only informs urbanists on facts, relations of the phenomenons, but also the methodology of the study of the cities.

03 METHODS TO CONDUCT YOUR INVESTIGATION

The author views the Emscher River, the natural symbol of the area, to be a thread that connects all the cases on multiple levels. Land-based strategies are the main focus of the study. To have a broad understanding of the region as a whole, the author started the research on the background information. The investigation includes the master plans about the transformation of the area and its consequences. Regional planning reports introduce the natural system and social characteristics and history of the area. Based on the understanding of the region as a whole with natural, social, and development history, the author conducted a timeline with the critical events that reveal catalysts and milestones.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-36

Figure 02. Aerial view of Emscher river, Rhine-Herne Canal, Emscherkunst.

11. Simmel, Georg. “(1903)‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’.” The Sociology of Georg Simmel (1950): 409-424.

12. Wirth, Louis. “Urbanism as a Way of Life.” American journal of sociology 44, no. 1 (1938): 1-24.

13. Choay, Françoise. “The modern city: planning in the 19th century.” 1969.

TIMELINE : HISTORY, ACTORS AND EVENTS

Figure 04. Ruhr Industry.

2000

“Handlungsprogramm zur räumlichen Entwicklung der Metropole Ruhr(Action programme for the spatial development of the Ruhr metropolis)” released by RVR in German

Regionalverband Ruhr (RVR) took over the Kommunalverband Ruhrgebiet (KVR) with expanded rights.

1800 1990

After 10 years’ programme, the The International Building Exhibition (IBA) Emscher Park began into work.

1959 1956 1952 1929 1913 1899

1850 1900 1851 1849 1847 1837 1893 2018 2004 2001

1995 1985 1982 1965 1999 2020 2010 1598

North Rhine-Westphalia at this time had the highest levels of smog in Germany.

Area wide protests by steelworkers against closures and lay-offs in the Ruhr. The last blast-furnace between Duisburg and Dortmund is closed down in Gelsenkirchen.

The Ruhr university which is the first university in the Ruhr area opened in Bochum.

The Zechensterben (death of the mines) began with the protest against the import of cheap American coal in Bonn.

The International Ruhr Authority ceased their work and was taken over by the European Coal and Steel Community which is the seed of the later European Union.

The world economic crisis caused the export-oriented production of the coal and steel industry to collapse.

The Ruhrreinhaltungsgesetz (law concerned with cleaning up the Ruhr) introduced laws that contributed in regulating the dam and ensuring the water supply of the growing conurbation.

The Emscher Cooperative is founded, primarily to deal with drainage and flooding measures in the Ruhr generally.

Formation of the Rhenish-Westphalian Coal Syndicate with its head office in Essen, as an association of a large number of Ruhr mines.

Zollverein Coal Mine begins operating.

Ruhr made smelting iron ore with coke for the first time.

The first steam locomotive to travel along the Ruhr valley, on the SteeleVohwinkler Railway.

The Kronprinz Mine reached the important deep-lying coking-coal seams of the Emscher Basin

In Holzwickede the development of mining is mentioned in document

Ruhr Valley A-37

Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex becomes a UNESCO World Heritage Site. 1600 1950

Ruhr iron industry reached the peak on demand for coal and the number of workers in the area at 124,6 million tonnes per year and 494,000 people.

The Ruhr becomes a part of the newly defined European metropolitan area Rhine-Ruhr.

Figure 03. Emscher River before and after its renaturation in the city of Dortmund.

Figure 05. Aerial view of shaft xii in Zollverein.

Design reports, including the description for different projects from regional to local scales, state the details of the process of the transformation. The examination on spatial characteristics of a series of real cases includes visualizations of the projects’ cartographic inventory, critical design elements, and collage that reflects the dynamics. The author focused on the landscape aspect with an assembled representation of aerial photos, geoinformation data such as land use, and 3d models. Diagrams depict the relationship among all actors and reveal the social dynamics of the process. Moreover, literature done by scholars asserts critical perspectives and investigation towards the planning and design of the region. Similar to the study of urbanism, this research integrates the data, analysis and author’s reflection of related urbanisms based on practices in the Ruhr Valley.

04 ANTICIPATED FINDINGS

The research provides a unique perspective that builds on the understanding of environmental features and the landscape of the Ruhr Valley. On the regional scale, the IBA Emscher Landscape Park, the Emscher Conversion and the Duisberg master plan set the top-level structures and backbones that take measures regarding the urban, social, cultural, and ecological development of the area. Those plans and initiatives are realized with local projects, among which the author chose three of them that are representative of the area.

Those three cases represent the region on diverse scales under similar situations, which is the shrinkage of the industry and the urban area as well. Even though three projects have diverse focuses and outcomes, the thread of the research can be found as the landscape as the toolkit and waterways as the main topics.

Acknowledging the role of this area back in the industrial epoch, the Zollverein Park is hard to be ignored since this site is created as the park. It serves as the natural connection between two post-industrial developments in the Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex. 14 Lake Phoenix project is part of the large-scale Emscher river restoration project with surrounding development. Since the Emscher renaturation and water management are considered the main approaches of the regional plan,

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-38

IBA Emscher Park

Figure 06. IBA Emscher Park and project location.

14. Planergruppe Oberhausen , Zollverein Park- A park evolves, Avda.vademarin,68;28023 Madrid, 2018. Accessed Mar. 2020. https:// www.planergruppe-oberhausen.de/zollvereinpark/

15. Peet, R. “A greener tomorrow: Water management in urban redevelopment.” Dortmund, Germany, ICLEI Case Study (2016).

16. Agence Ter, Averdung Platz, 2011, Accessed Jan. 2020. http://landezine.com/index. php/2011/11/duisburg-agence-ter-landscapearchitecture/

10 mile

Averdung Plaza

Zollverein Park

Lake Phoenix

Ecological Development Center

Ecological Corridor

Emscher River

Other Waterway

Emscher Landscape Park

Preserved Area

Lake Phoenix project showcases the potential of comprehensive urban sustainable development to facilitate the ecological and economic wellness of the area with a collaborative process.15 Averdung Plaza, a smaller scale project which is a civic plaza would call out the unique perspective from landscape architects featuring the urban social space by greenness. 16

Together, those real cases with landscape components and ecological focus may reveal the truth. It is that landscapes that serve as the base and usually forgotten in the urban analysis can play an essential role in the environment-based transformation and regional urban developments. The way it works in the Ruhr Valley is through the consistency of a well-engaged top-down planning system, the interdisciplinary collaborations, and, most importantly, the human nature of love for “green”.

As an urbanist and a future landscape architect who focuses on urban ecology, the author would like to expand the understanding of urban development and green redevelopment through a broad investigation of urban dynamics in the area and cases with related urbanisms. This research tends to explore the Ruhr Valley with its history, development and especially design projects to learn the process as reference for transformation plans all over the world. Similar regions include the Detroit metropolitan area that is part of the Rust Belt in the USA, Kansai in Japan and Northeast Industrial Region in China.

Ruhr Valley A-39

Natural System of The Ruhr Valley

Industries are usually developed along the waterways due to the geological nature and transportation need.

Water

Industrial Development

20 mile

Broad “greenland” can be “the future of Ruhr”

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020

Water

Green Open Space

Preserved Area

20 mile

A-40

Figure 07 : Natural system of the Ruhr Valley.

Urban Development Change of The Ruhr Valley

20 mile

Development

Area

Valley A-41

1840

Sprawl” significantly change the land.

1930

Water Urban

Paved

Ruhr

In

“Urban

In

1970 Nowadays

In

08

development

Figure

:Urban

change of the Ruhr Valley.

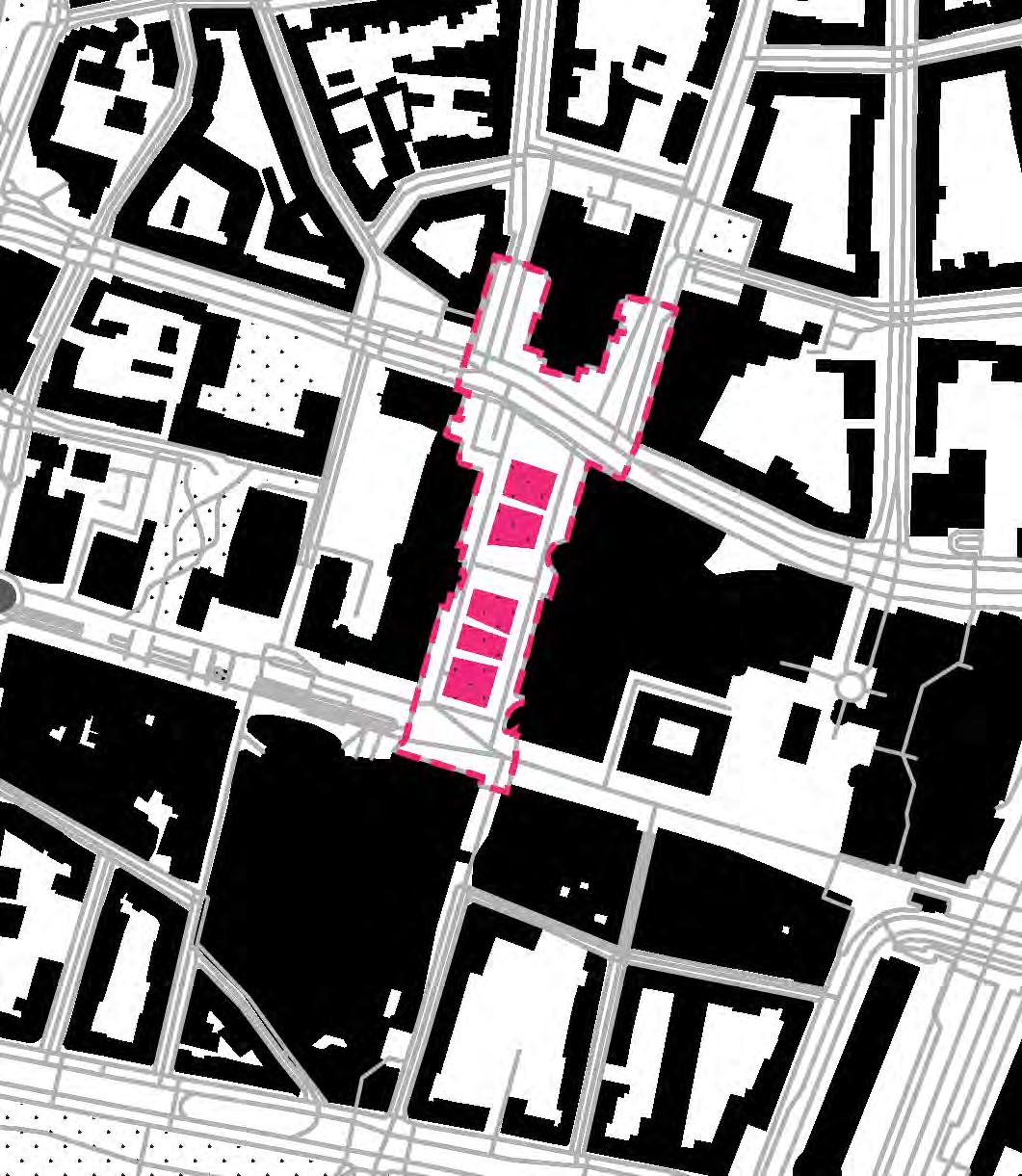

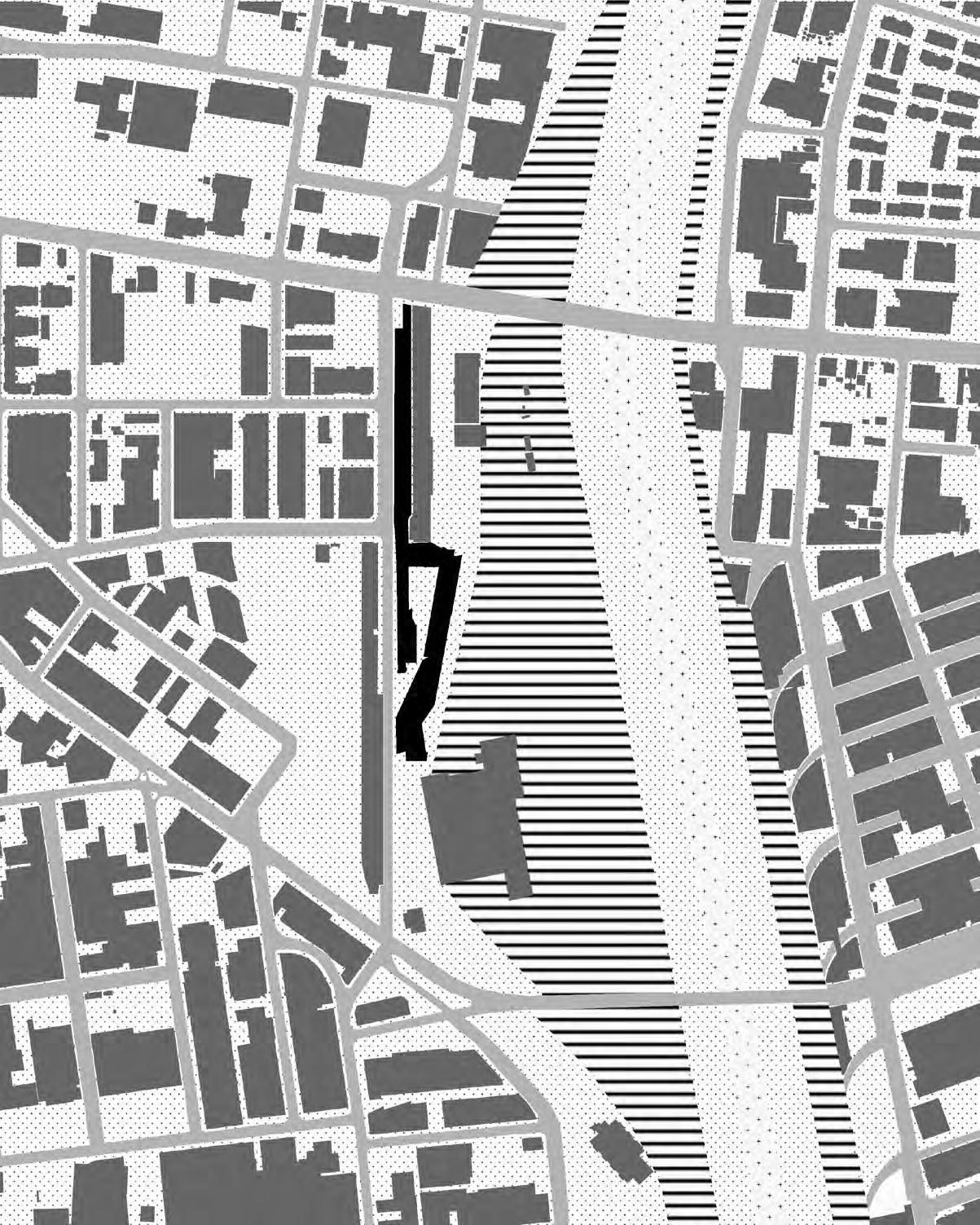

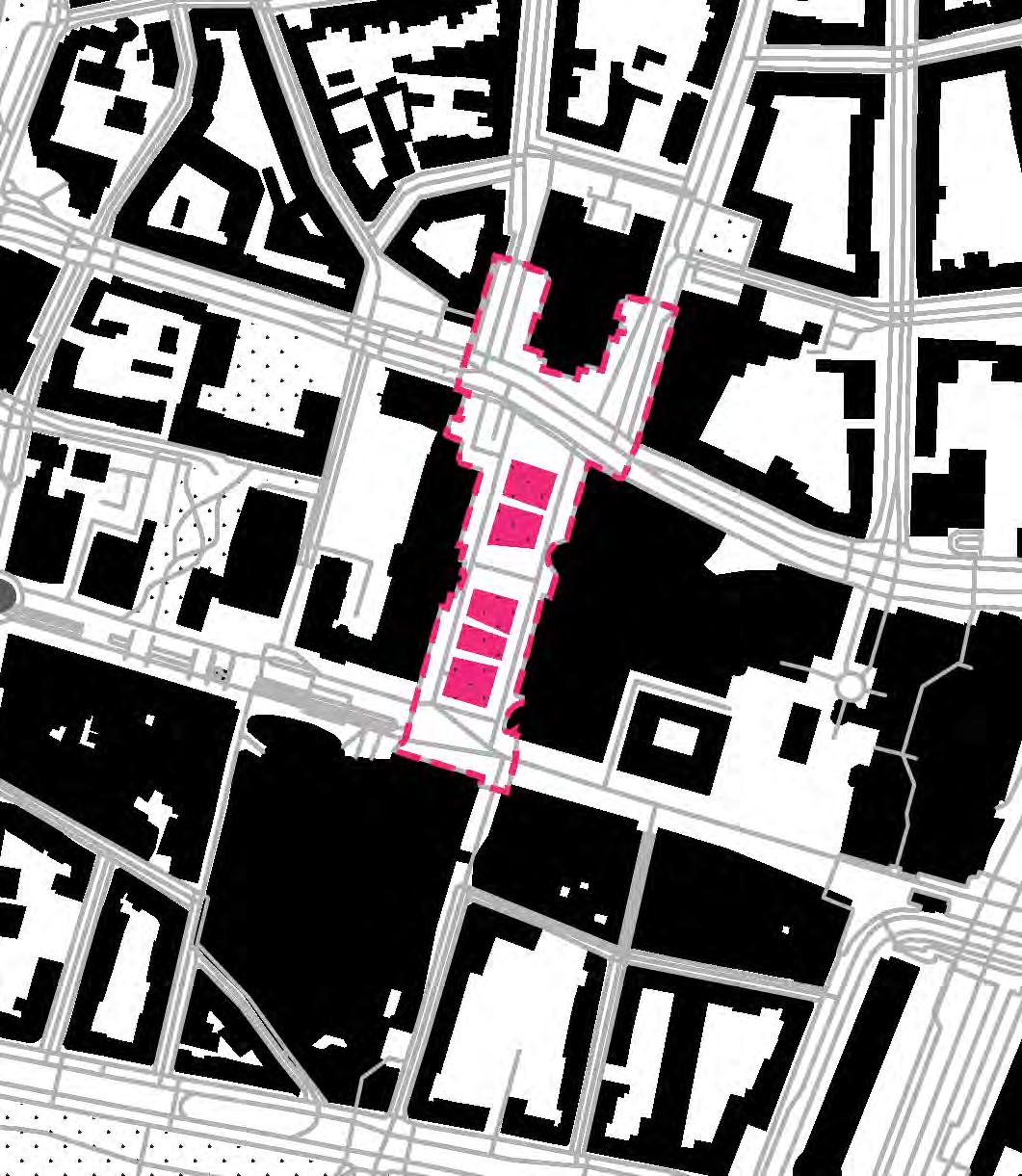

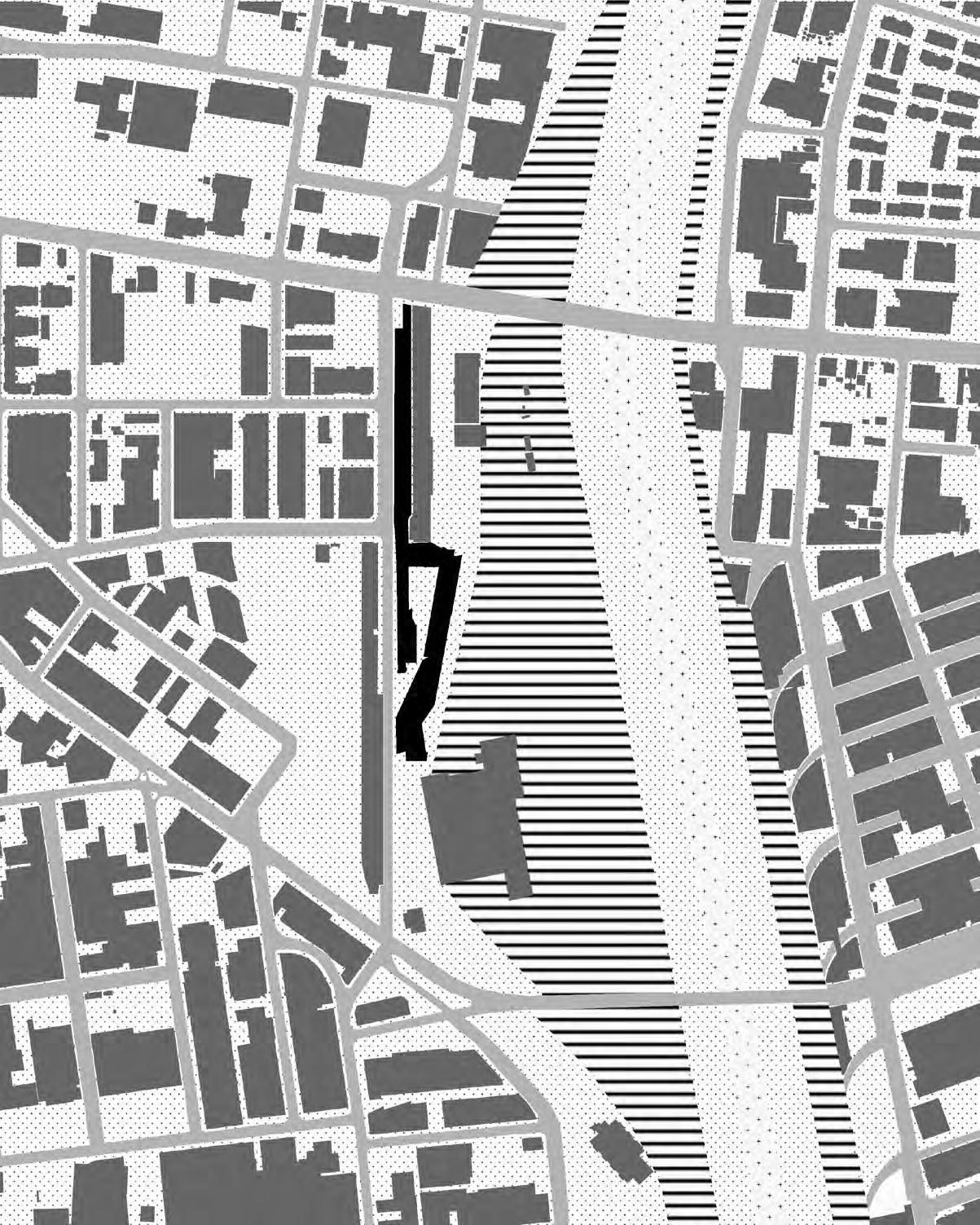

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-42 0 2 mile Essen Zollverein Park Emscher River Legend Stream River Green Space Site Industrial Commercial Landmark

Figure 09. Context of Zollverein Park

17.Ruhr, Regionalverband, ed. Unter freiem Himmel/Under the Open Sky: Emscher Landschaftspark/Emscher Landscape Park. Walter de Gruyter, 2013.

18. OMA, Zollverein Masterplan, Accessed Mar. 2020. https://oma.eu/projects/zollvereinmasterplan

ZOLLVEREIN PARK [POST INDUSTRIAL URBANISM]

Being part of the IBA Emscher Landscape Park “multifunctional blue-green network.” 17, Zollverein Park is the green open space in the industrial complex that sits outside of the city center of Essen. Done by OMA, the masterplan of the complex transforms the factory remains successfully through the idea of “walled city” and the “conservation by conversation” that reuse the structure remains as the introduction of Art and Culture as the new core of life.18

Implemented in 2018, the Zollverein Park serves as the natural connection between two post-industrial developments in the Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex. The designs also help build the natural and cultural connections with the industrial history that is meaningful to the area. This case shows the possibility of a former industrial campus to be turned into a landmark that respects the land and artfully recalls the history.

Location Year(s) Status

Footprint Designer

Additional Agents

Key Project Components Program(s)

Funding Streams

[Essen, GERMANY]

[2005-2018]

[Built]

[Consider both landscape and built...] [Planergruppe Oberhausen]

[Obervatorium, Rotterdam– arts; F1stdesign, Cologne – orientation system; Licht Kunst Licht, Bonn – light design [Green space, Industry plants, Industrial complex ]

[Preserved structure, Open space, Enclosures, Trails, Mixed-use development ]

[Public]

Ruhr

A-43

Valley

Zollverein Park

Lippe River

Emscher River Ruhr River

Essen

Rhein River

Figure 10. Location of Zollverein Park.

ZOLLVEREIN PARK AND POST INDUSTRIAL URBANISM

As a case illustrating the tenets of Post-industrial Urbanism, this project deploys a series of landscape practices regenerating formerly industrial sites. The death of mines and the drastic decline of the coal and steel industry made Ruhr’s 1980s. In response to the need for post-industrial solutions, the International Building Exhibition Emscher Park (IBA) became a workshop to propose the future of the industrial region with a conceptual structural change. This regional project involved 17 cities and 117 projects, and included landscape planning and urban development projects for ecological, economic, and cultural renewal.19 The 10-year long Emscher Landschaftspark (Emscher Landscape Park) was created as an experimental approach to land management strategies and included numerous collaborations, mainly in the public sector.

Planergruppe Oberhausen, the landscape team, proposed the “track boulevard and the ring promenade” as a key feature and a linkage to all the urban development. The landscape is reintroduced into the site accompanied by park scrapes making available necessary new, multifaceted, and robust infrastructure for new activities at Zollverein. 20

Zollverein becomes a park with urban forests, lush shrubs, and open spaces, revealing the view of the post-industrial Art and Cultural center from the treeshaded paths.21 Beyond the typical cleaning-up and repairment, these projects provide the opportunity to preserve the industrial memory and post-industrial identity of the area.22 Despite the achievements of the projects so far, Egberts has criticisms on whether the focus on Industrial culture will remain when facing the shortage of funding.23 This addresses the fact that the establishment of the projects required fundings from major public resource.

19. Internationale Bauausstellung Emscher Park (Hrsg.): Katalog der Projekte 1999, Gelsenkirchen 1999. Accessed Mar. 2020. https://www.internationale-bauausstellungen. de/en/history/1989-1999-iba-emscher-park-afuture-for-an-industrial-region/

20. Planergruppe Oberhausen , Zollverein Park- A park evolves, Avda.vademarin,68;28023 Madrid, 2018, Accessed Mar. 2020. https:// www.planergruppe-oberhausen.de/zollvereinpark/

21. JOSÉ JUAN BARBA, ANDREA PORTILLO, METALOCUS, “THE EMSCHER LANDSCAPE PARK” Accessed Jan. 2020. https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/ emscher-landscape-park

22.Regionalverband, ed. Unter freiem Himmel/Under the Open Sky: Emscher Landschaftspark/Emscher Landscape Park. Walter de Gruyter, 2013.

23. Egberts, Linde. Chosen legacies: heritage in regional identity. Taylor & Francis, 2017.

24. Internationale Bauausstellung Emscher Park (Hrsg.): Katalog der Projekte 1999, Gelsenkirchen 1999. Accessed Mar. 2020. https://www.internationale-bauausstellungen. de/en/history/1989-1999-iba-emscher-park-afuture-for-an-industrial-region/

25. Planergruppe Oberhausen , Zollverein Park- A park evolves, Avda.vademarin,68;28023 Madrid, 2018, Accessed Mar. 2020. https:// www.planergruppe-oberhausen.de/zollvereinpark/

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-44

Figure 11. Simple and robust furnishing in Zollverein Park.

Ruhr

Ring Promenade Green

Industrial Area Boundary 0.5

Valley A-45

Space Forest Water

mile

Figure 12. Plan of Zollverein Park.

Regional Corporation

Regional Association of Ruhr

EU, Federal, State

State of North Rhine-Westphalia, 17 cities

Policy

Moderater Regional Plan Local Project

Emscher Landscape Park

Emscher Conversion

Duisburg Master Plan

Funding Expertise

Zollverein Park

Lake Phoenix

Averdung Plaza

Urban Designer, Architect, Landscape Architect, Engineer

Local Government

City of Essen

ZOLLVEREIN PARK DESIGN Transect

The IBA plan has three stages start with an overall strategy, the framework with six topics that focus on regional interventions, and realization by numerous local projects.24 It is the large scale, comprehensive engagement, and cooperation among stakeholders that make the plan a success model.

Featured former trails transform into paths for walkers, joggers, and cyclists. Industrial wastelands were declared nature reserves, leftover industrial land was taken as an opportunity to create a new landscape, and heaps became landmarks. 25

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-46

IBA Emscher Park

Figure 13. Diagram of actors of Zollverein Park.

Figure 15. Transect of Zollverein Park during the industrial era and now.

Ruhr

A-47

Valley

Industrial time heaps Taxonomy

Urban Forest

Industrial Wetland

The Ring Promenade

The Track Boulevard

Figure 14. Taxonomy of Zollverein Park.

Theories

and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-48

Figure 16. Collage of Zollverein Park.

Ruhr Valley A-49

Ruhr Valley A-49

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-50 0 2 mile Legend Stream River Green Space Boundary Site Industrial Open Space Commercial Mixed-use Landmarks Residential Dortmund Lake Phoenix

Figure 17. Context of Lake Phoenix.

26. WIKUE. “Emscher 3.0: from grey to blue or, how the blue sky over the Ruhr region fell into the Emscher, by Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie GmbH.” (2013) : 15-35.

27. Gruehn, Dietwald. “Germany Goes GreenInnovationstowards a Sustainable Regional Development.” World Technopolis Review 1, no. 4 (2013): 235.

28. Emscher conversion, Accessed Mar. 2020. https://www.eglv.de/en/ emschergenossenschaft/emscher-conversion/

LAKE PHOENIX (PHOENIX SEE)

[ECOLOGICAL URBANISM]

Situated in the city of Dortmund, Lake Phoenix project is part of the Emscher River restoration and includes surrounding new real estate development. According to the regional guidebook Emscher 3.0, the Emscher master plan of the riverside emerges from its specific industrial and settlement history, proposes waterways engineering and renaturalization into a new, innovative meaning that aims at bringing back a blue Emscher river with technology, ecology, and quality.26 The Emscher renaturation leads to the establishment of Emscher Landscape Park.27 The Wastewater Emschergenossenschaft and Lippeverband are two public sector management companies and operators.

The conversion includes engineering and renaturalization that channels wastewater into underground canals and neutralizes the surface waterway with natural habitats and stormwater management. The Emscher Conversion project aims to decisively enhance the value of the Emscher region through projects that extend far beyond the waterways, sustainably changing the living and working environment of the population. 28

Location Year(s) Status Footprint Agents

Key Project Components Program(s)

Funding Streams

[Dortmund, GERMANY] [2010]

[ Built ] [200 hectares]

[Thyssen-Krupp AG , local government and the management consultancy McKinsey & Co] [Lake, Sustainable development]

[Recreation, Residential housing and Office-services, Commerce facilities,Public infrastructure]

[Public and Private]

Ruhr

A-51 Phoenix Lake (Phoenix-See)

Valley

Lippe River

Emscher River

Ruhr River

Dortmund

Rhein River

Figure 18. Location of Lake Phoenix.

LAKE PHOENIX AND ECOLOGICAL URBANISM

Learning from the scientific fields of Ecology and Urban Ecology, Ecological Urbanism focuses on a systematic approach toward environmental urgency, the dynamics of the elements, and movement in the cities.29 Broad interdisciplinary collaborations at all levels, such as political, planning, design and implementation, can bring the theory into practice. While there is still debate going on whether the urban social fabrics are well intervened in this topic 30, the practices of the theory tend to bring not only environmental benefits but also social benefits to humans and cities. The Lake Phoenix project would be a pilot project showcasing those benefits.

The Phoenix Lake project meets all criteria in terms of design intents. The lake itself becomes the local recreation area and improves the environment by daylighting the original stream creating the human-made lake that prevents the flood and enhances wildlife habitats.31 The surrounding area is developed with modern residential buildings, commercials, and retails that economically and socially bring back life.

Besides, since the project has been put to the ground so that it can be evaluated on environmental performance and the ecosystem services it provides. Researchers examine the ecosystem services the plan provides and conclude that there is a significant improvement in the reduction of pollutants, biodiversity, and flood prevention, which all lead to environmental benefits. There is a growing amount of economic value driven by the development of the project and the improvement of environmental quality. 32

The project starts with the major lake, recreation plans, and mixeduse development, which work collectively to serve as a center of residential, technological, and touristic life contributing to ecological, social, and economic sustainability and therefore enhancing life quality. On the other hand, there have been criticisms about the gentrification issue emerging from the development due to not diverse housing developments targeting mix-income affordability.33

29. Mostafavi, Mohsen, and Gareth Doherty, eds. Ecological urbanism. Lars Müller Publishers, 2010.

30. Hagan, Susannah. “Ecological Urbanism”, 2015. Accessed Mar. 2020. https://www. architectural-review.com/essays/ecologicalurbanism/8679977.article

31. Peet, R. “A greener tomorrow: Water management in urban redevelopment.” Dortmund, Germany, ICLEI Case Study (2016).

32. Gerner, Nadine V., Issa Nafo, Caroline Winking, Kristina Wencki, Clemens Strehl, Timo Wortberg, André Niemann, Gerardo Anzaldua, Manuel Lago, and Sebastian Birk. “Large-scale river restoration pays off: A case study of ecosystem service valuation for the Emscher restoration generation project.” Ecosystem Services 30 (2018): 327-338.

33. Davy, Benjamin. Land policy: Planning and the spatial consequences of property. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2012.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-52

Figure19. Phoenix Lake view, by Dumitru Brinzan, 2013

Boundary 0.5

Ruhr Valley A-53 River Green Space Forest Road Lake

mile

Figure 20. Plan of Lake Phoenix.

Regional Corporation

Regional Association of Ruhr, Emscher Cooperative, Development Corporation of the State of NRW ltd.

Funding

EU, Federal, State

Policy

State of North Rhine-Westphalia

Moderater

IBA Emscher Park

The Project Ruhr GmbH Department of Planning of the City of Dortmund

Regional Plan

Local Project

Emscher Landscape Park Zollverein Park

Emscher Conversion

Lake Phoenix

Duisburg Master Plan Averdung Plaza

Expertise

Urban Designer, Architect, Landscape Architect, Engineer

Local Corporation

the Wirtschafts- und Beschäftigungsförderung ( Business and Employment Promotion ) of the City of Dortmund the Phoenix See Entwicklungsgesellschaft mbH ( Phoenix Lake Development Corporation ltd.

LAKE PHOENIX DESIGN

The restoration intervention includes upgrading sewer systems that deal with stormwater management, renaturalization of the river bank and the creation of the lake to bring back wildlife.

The design also creates open spaces such as plazas, overlooks, playgrounds and fields by the lake to provide recreation use for surrounding residents.

Transect

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-54

Figure 21. Diagram of actors of Lake Phoenix.

Figure 23. Transect of Lake Phoenix during the industrial era and now.

Taxonomy

Ruhr Valley A-55

Industrial Site

Lake Phoenix

Playground

Re-naturalization of River Bank Lake

Figure 22. Taxonomy of Lake Phoenix.

Ruhr Valley A-55

Industrial Site

Lake Phoenix

Playground

Re-naturalization of River Bank Lake

Figure 22. Taxonomy of Lake Phoenix.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-56

Figure 24. Collage of Lake Phoenix.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-56

Figure 24. Collage of Lake Phoenix.

Ruhr Valley A-57

Ruhr Valley A-57

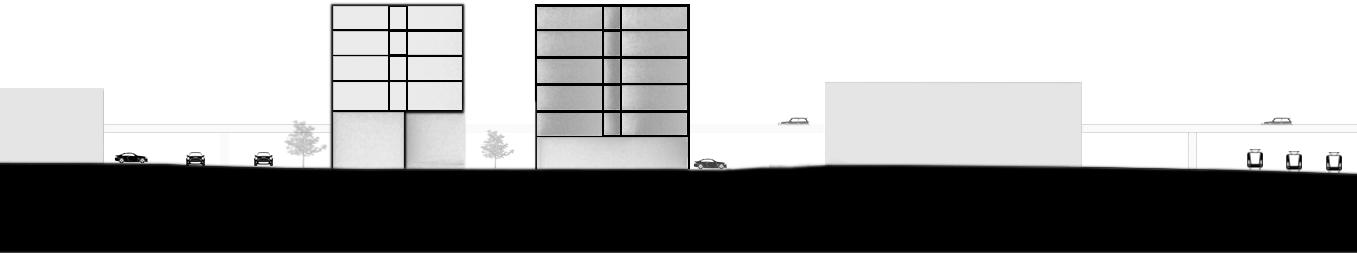

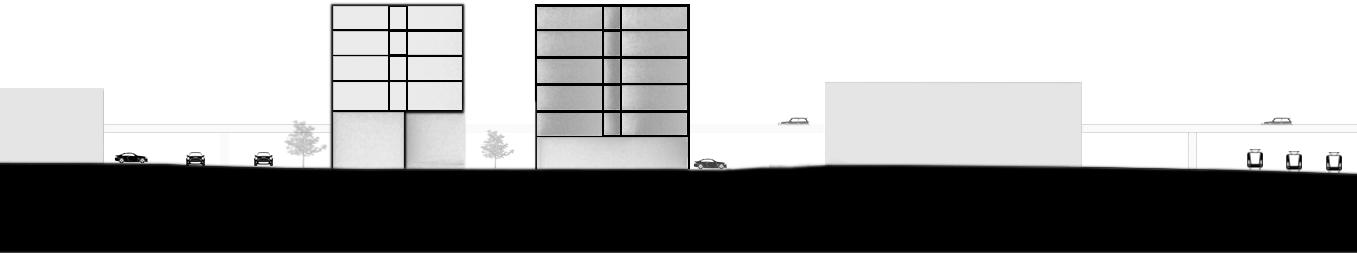

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-58 0 300 ft 0 2 mile Legend Stream River Green Space Site Industrial Commercial Landmarks Ruhr River Rhine River Averdung Plaza

Figure 25. Context of Averdung Plaza.

PLAZA

Averdung Plaza is located in the center of Duisburg. It is designed based on people’s social life and gathering needs by utilizing a variety of urban amenities with details at human scale. The tool that designers use is the landscape, which is the center green plaza.

This project may set a tone for the master plan of the larger area of the city for regeneration. Planned by Foster and Partners, the master plan developed the strategy for the city of Duisburg towards “a vibrant, green and sustainable city”. The vision focuses on strengthening existing links between public transport infrastructures and the reintroduction of the inner city as a central focus within this urban fabric. Complex culturally sustainable developments, including the open spaces, are proposed to make the city attractive and welcoming again.34

Ruhr Valley A-59

Averdung Plaza (Platz Averdung)

(KÖNIG-HEINRICH

[LANDSCAPE

[Duisburg, GERMANY] [2004] [Built] [1.6 hectare] [Agence Ter] [City of Duisberg]

Space, City Center Redevelopment] [Plaza, Green Space] [Public]

Year(s) Status Footprint Designer Additional Agents

Project Components Program(s)

Streams

AVERDUNG

PLATZ AVERDUNG)

URBANISM]

[Open

Location

Key

Funding

34. Foster and Partners, Duisburg Masterplan, 2007, Accessed Jan. 2020. https://www. fosterandpartners.com/projects/duisburgmasterplan/

Lippe River

Emscher River

Ruhr River

Duisburg

Rhein River

Figure 26. Location of Averdung Plaza.

AVERDUNG PLAZA AND LANDSCAPE URBANISM

The idea of Landscape Urbanism treats “landscape as the medium” 35 to tackle problems in urban areas such as cities. The theory is raised by landscape architects addressing that the tool, knowledge, and creativity of this discipline can have positive impacts on the urban environment and offer solutions through intervention on the timely horizontal surfaces, which is the landscape.36 In design practices, the surface can be in urban infrastructure, public open spaces, and urban natural areas. Inspired by the existing landscape on the site, landscape architects brought the lawn into the center of the popular area. Natural open space was not common in such a dense post-industrial city that is transforming into the green future city. This simple, elegant design with fine-textured urban furniture builds a wide expanse of grass on which people can relax. The project consists of a game between the mineral, vegetation and water play that animate the central space.37

This design also provides an elegant example of creating civic space with experience and observations on landscapes. As stated in the intent, “the city envisioned re-arranging this precinct to make it more urban and representative,” designers create this public space to invite people to the social life in the center of the city.38 This project implies the importance of the observation and perception of the trait about human life. Inspired by the “Social Life of Small Urban Space” 39 that focuses on the behavior of people in public areas and the relationship between human and physical space, the study finds the practice reflecting that importance.

35. Samuel Medina, Charles Waldheim: Landscape Urbanism All Grown Up, July, 2016, Accessed Mar. 2020. https://www. metropolismag.com/ideas/charles-waldheimlandscape-urbanism-all-grown-up/

36. Corner, James. The landscape imagination [electronic resource]: collected essays of James Corner, 1990-2010. Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2014.

37. Land 8, König-Heinrich Platz Averdung Shows us All That Keeping it Simple is the Best Policy, Accessed Mar. 2020. https://land8.com/ konig-heinrich-platz-averdung-shows-us-allthat-keeping-it-simple-is-the-best-policy/

38. Agence Ter, Averdung Platz, 2011, Accessed Jan. 2020. http://landezine.com/index. php/2011/11/duisburg-agence-ter-landscapearchitecture/

39. Whyte, William H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Washington, D.C.: Conservation Foundation, 1980.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-60

Figure 27. View of the plaza during event, by Agence Ter

Ruhr Valley A-61 0.1 mile

Building

Road Boundary

Figure28: Plan of Averdung Plaza

Green Space Water

Regional Association of Ruhr

Funding

EU, Federal, State

Policy

State of North Rhine-Westphalia

Moderater Regional Plan Local Project

IBA Emscher Park

AVERDUNG PLAZA DESIGN

Cooperation Local Corporation

Emscher Landscape Park Zollverein Park

Emscher Conversion

Lake Phoenix

Duisburg Master Plan Averdung Plaza

Expertise

Urbanists, Urban Designers, Landscape Architects

City of Duisburg

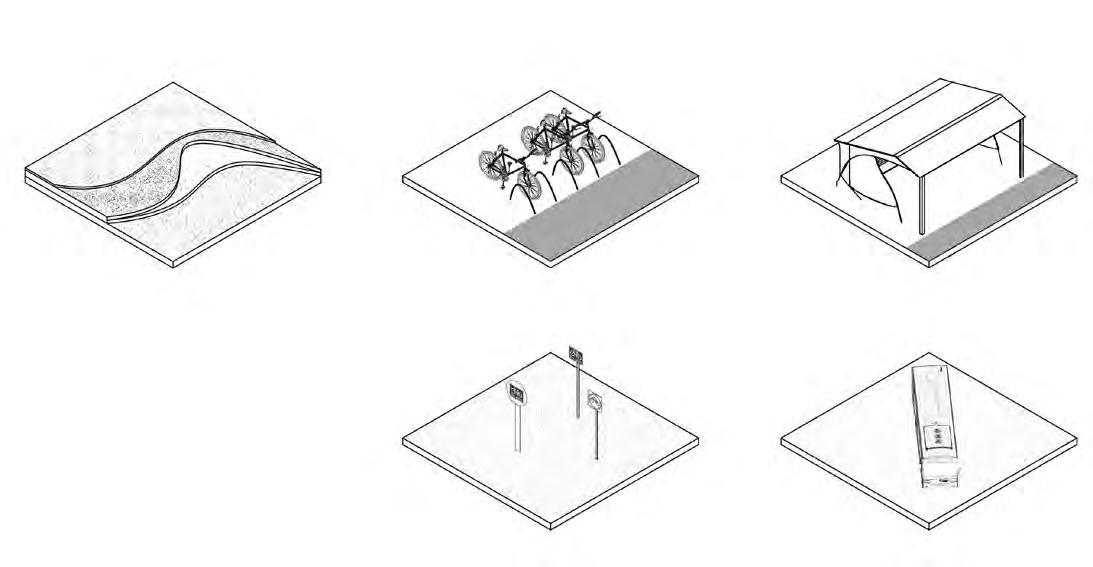

Sitting in the busy center of the city surrounded by urban landmarks, the plaza design utilizes fine scale designs such as planting, urban furnitures, fountain, sculptures and the events programming to activate the space.

Transect

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-62

Figure 29. Diagram of actors of Averdung Plaza.

Figure 31. Transect of Averdung Plaza during events.

Taxonomy

Ruhr Valley A-63

Events Amenity

Sculpture

Fountain

Figure 30. Taxonomy of Averdung Plaza.

Ruhr Valley A-63

Events Amenity

Sculpture

Fountain

Figure 30. Taxonomy of Averdung Plaza.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-64

Figure 32. Collage of Averdung Plaza.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-64

Figure 32. Collage of Averdung Plaza.

Ruhr Valley A-65

Ruhr Valley A-65

SOUTHERN NIGERIA NIGERIA

01 IDENTIFICATION OF THE TERRITORY AND LOCATION

Nigeria is a country in the Western part of the African continent. It is bordered by the Republic of Benin and Niger to the West and North respectively. It shares its Eastern border down to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean with the Republic of Cameroon. Modern Nigeria was established in 1914 when the British protectorate of Northern and Southern Nigeria were joined. The country gained independence in 1960.

Nigeria has six-geopolitical zones carved out from Northern and Southern Nigeria a way to effectively distribute resources by grouping the country based on similar categories among the hyper-diverse 400 ethnic groups and 250 languages. Today, notable differences exist between the North and the South not only in physical landscape, climate and vegetation but also in social organization, religion, literacy and agricultural practices. This study focuses on the Southern part of Nigeria which has three geopolitical zones- South-South (Bayelsa, Cross-River, Rivers, Delta, Akwa-Ibom), South-West (Ogun, Oyo, Lagos, Ondo, Ekiti, Osun) and the South-East, (Abia, Anambra, Enugu, Ebonyi, Imo). The total population of this territory is about 76,000,000 people.6

02 RELEVANCE FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF URBAN DESIGN THEORY AND PRAXIS

This research examines the recent urban transformation in Southern Nigeria, with a focus on the interrelationships between socio-economic inequality and environmental vulnerabilities under the lenses of social, informal/insurgent and new urbanisms. To understand the evolution of urban planning and design in the region, it is critical to acknowledge the legacy of colonial British rule and the different eras of leadership and their impact.

Pre-colonial settlements in the south were simply built for convenience and pragmatic programs for community, livelihood and thermal comfort. However, under the administration of the Colonial era, the issues of trade and transportation started to change the socio-spatial geography of the territory

1. Statistics. In Worldometers. Accessed May 21, 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/worldpopulation/nigeria-population/.

2. Statistics. In the World Data Atlas. Accessed May 21, 2020. https://knoema.com/atlas/ Nigeria/topics/Education/Literacy/Adultliteracy-rate.

3. Ade Ajayi, J.F, Anthony Hamilton, and Reuben Kenrick. Essay. In Encyclopaedia Britannica, edited by Toyin O Falola. Accessed May 21, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/ place/Nigeria.

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-66

[Critical DATA]

Geographical Delimitation

Nigeria is bordered to the north by Niger, to the east by Chad and Cameroon, to the south by the Gulf of Guinea of the Atlantic Ocean, and to the west by Benin.

Population

National: 205,532,461;1about 2.64 percent of the total world population and Africa’s most populous country.

Focus: Southern Region- 76 million

Social Indicators

The major ethnic groups are; Yoruba and Igbo while some of the minor ethnic groups are Urhobo. The major religions practices are Roman Catholicism, Christianity, and Islam. Nigeria adult literacy rate was at level of 62 % in 2018, up from 51.1 % in 2008.2 Infant mortality rate is 77.8 out of every 1000 births. Only 28% of Nigerians have access to improved sanitation facilities while 64% have access to potable drinking water.

Economic Indicators

The major occupations are in the agrarian, manufacturing, and extraction/mining of natural resources especially crude oil. Over the past years, the construction sector, education, and tourism have also experienced growth. It is the country with the highest number of extremely poor people in the world. By May 2020, 1 US dollar is worth 390 Nigerian Naira. 100 million Nigerians are said to live below 2 dollars per day. GDP per capita is $2,222 (nominal, 2019 est.) Debt-to-GDP ratio is 16.075 percent as of 2019, inflation rate is The unemployment rate is 6.11% Average life expectancy is 54 years 50% of Nigerian live in slums, while 2 out of every 3 urban dwellers live in informal areas.

Environmental Indicators

Nigeria has a tropical climate with variable rainy and dry seasons, depending on location. It is hot and wet most of the year in the southeast but dry in the southwest and farther inland. A savanna climate, with marked wet and dry seasons, prevails in the north and west.3

Nigeria has the highest burden of fatalities from air pollution in Africa and 4th globally, producing more than 3 million tons of waste annually. According to the HEI chart, there were 150 deaths per age-standardized deaths per 100,000 people attributable to air pollution in Nigeria in 2016.4 In Lagos, an estimated seven million people died from diseases related to indoor and outdoor air pollution in 2012 according to the WHO.

Nigeria’s climate has been changing, evident in: increases in temperature; variable rainfall; rise in sea level and flooding; drought and desertification; land degradation; more frequent extreme weather events; affected fresh water resources and loss of biodiversity.5

4. Ogundipe, Shola. “Essay.” In Nigeria: Air Pollution - Nigeria Ranks 4th Deadliest Globally. Accessed May 21, 2020. https:// allafrica.com/stories/201809010001.html.

5. Haider, Huma. “Essay.” Climate Change in Nigeria: Impacts and Responses, 2. Accessed May 21, 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/5dcd7a1aed915d0719bf4542/675_ Climate_Change_in_Nigeria.pdf.

6. Essay. In The Violent Road: Nigeria’s South West. Accessed May 21, 2020. https://aoav.org. uk/2013/the-violent-road-nigeria-south-west/.

Southern Nigeria A-67 Nigeria Africa

in ways that the British colonial masters did not anticipate. This situation was exacerbated by the laissez-faire attitude that the colonial masters had towards urban planning; their interests were solely in rural administration and rural export and the segregation of their colonies from the rest of the cities. During the colonial period, the Southern part of Nigeria was a British protectorate and in 1915. After the amalgamation of Northern and Southern Nigeria for economic reasons; the surplus from the South was redistributed for the development of the North.

Employment opportunities available in the cities brought rapid urbanization between 1914 and 1970 accompanied by housing shortage, unsanitary conditions, air and water pollution, waste management problems and inadequate transportation.7 The Nigerian Town and Country Planning Ordinance Act of 1946 regulated urban growth and it was modelled after the British Town and Country planning Acts of 1932.8 Three agencies were in charge to advance government plans: the Planning Authority, the Urban Council, and the Health Authority. These agencies did not work in harmony; and in fact, inhibited each other’s work.9

Nigeria was granted independence on October 1, 1960 and it became a republic in 1963. After a brief period of political and economic bliss, Nigeria’s long-standing regional differences based on ethnic competitiveness, educational inequality, and economic imbalance, again came to the foreground in one of the bloodiest conflicts in the continent, the Biafran War. The discovery of oil reserves and the control on production and profit also did their part in the conflict. This situation birthed environmental justice movements and insurgent responses from residents and environmental activists.

Over the past decades (1960 to 2010’s), urban transformation in Southern Nigeria has been plagued with challenges stemming from pitfalls in policies, an unstable economy, and lack of public infrastructure for transportation, electricity, and sanitation.10 To showcase the implications of these socio-economic and political conditions in city making and public life, this investigation takes a deeper look

Theories and Methods of Urban Design Winter 2020 A-68

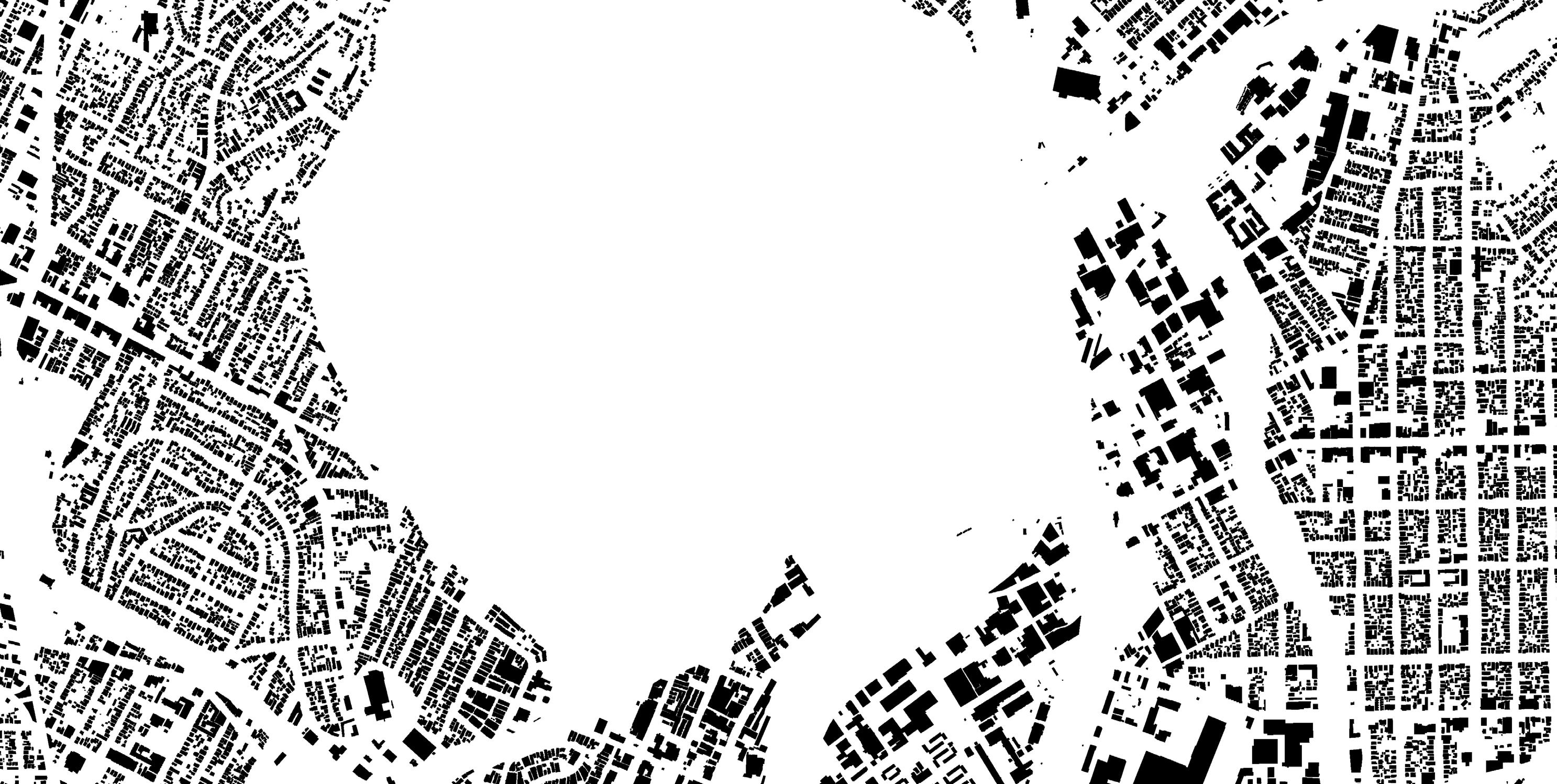

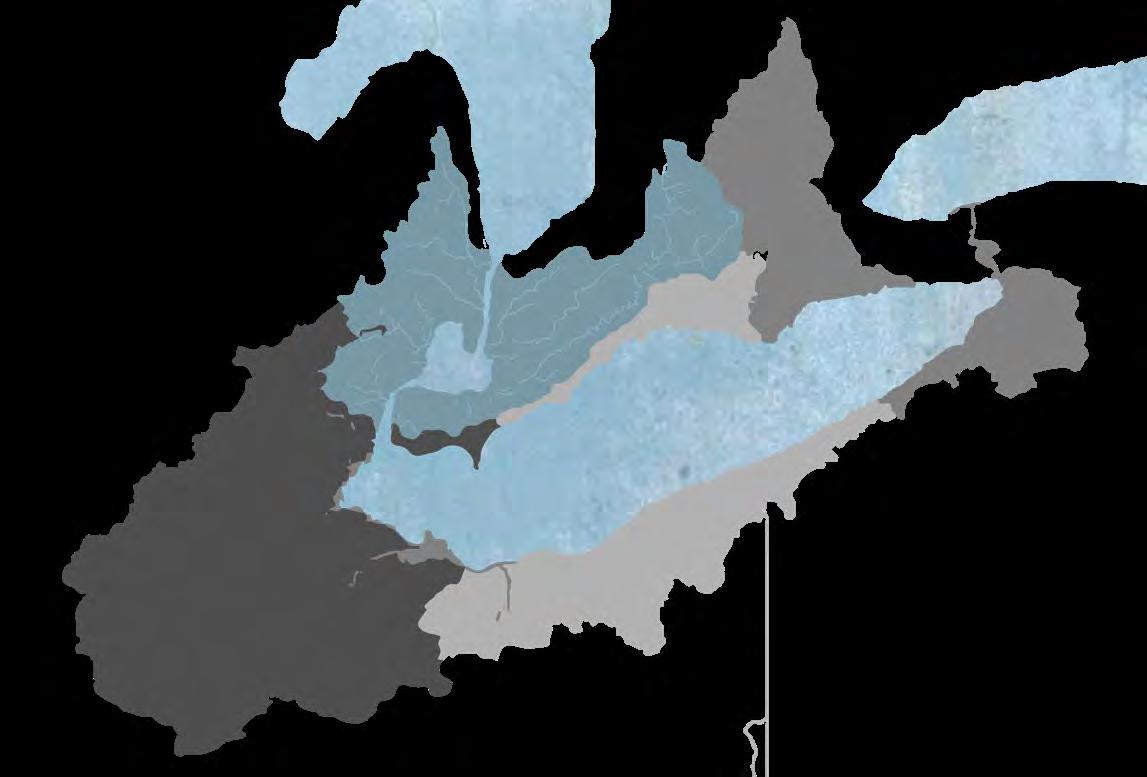

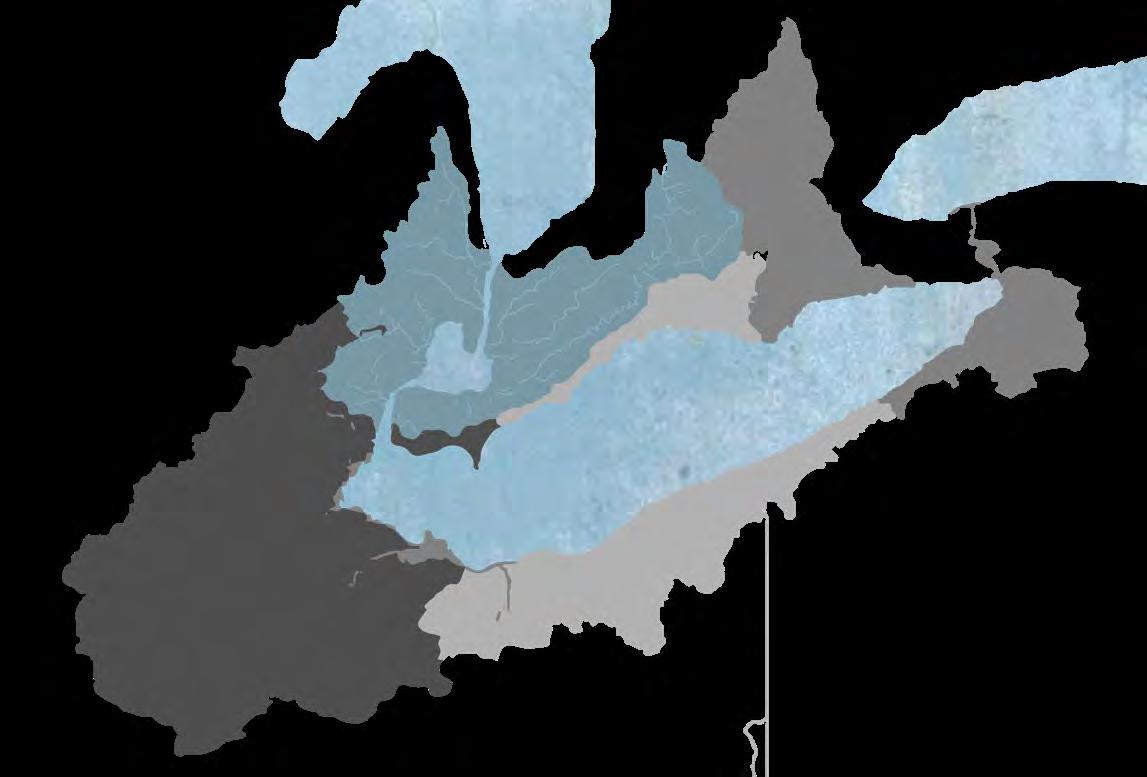

Figure 1-Map showing the Southern region of Nigeria

Figure 2-Population density map

7. Obinna, V. & Owei, Opuenebo & Mark, E. (2010). Informal Settlements of Port Harcourt and Potentials for Planned City Expansion. Environmental Research Journal. 4. 222-228. 10.3923/erj.2010.222.228.

8. Taylor, Robert W. “Urban Development Policies in Nigeria: Planning, Housing, and Land Policy.” Essay. In Urban Development Policies in Nigeria: Planning, Housing, and Land Policy, 3–9, 2000. https://msuweb.montclair. edu/~lebelp/CERAFRM002Taylor1988.pdf.

9. Uyanga Joseph, Urban planning in Nigeria: Historical and administrative perspectives and a discussion of the city of Calabar (Habitat International Volume 13, Issue 1, 1989, Pages 127-142)

TIMELINE : HISTORY, ACTORS AND EVENTS

500 In Nigeria evidence of urbanization at the Yoruba city of Ife dated back to about this time

1884 The British took an interest in Nigeria because of its resources and they colonized Nigeria in 1884. The three largest ethnic groups upon the arrival of the British were the Igbo, the majority in the southeast; the Hausa-Fulani of the Sokoto Caliphate, the majority in the north; and the majority in the southwest.

1900 The British Government established the Southern protectorate assumed control of the Southern and Northern Protectorates.

1914 British colonial amalgamation of Northern protectorate, Lagos Colony and Southern Nigeria protectorate Lagos becomes the capital of Nigeria

1946 The Nigerian Town and Country Planning Ordinance Act of 1946 regulated urban growth following the model of the British Town and Country planning Acts of 1932

1956- Shell-BP expedition makes first discoveries of major petroleum deposits in the Eastern Region, at Olobiri and Afam, in Port Harcourt, transforming the city’s economy to petroleum.

1960 Nigeria gained independence from the United Kingdom, but remained in the Commonwealth of Nations.

1965 Refineries completed in Port Harcourt, owned 60% by Federal Government, 40% by Shell BP

1967 The Biafran War started, resulting from political, economic, ethnic, cultural and religious tensions; and control over the oil production in the Niger Delta. War ended in 1970.

1971 Nigeria joins the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)

1975 Relocation of the capital from Lagos to Abuja for reasons of congestion and ethnic neutrality.

1975 The Third National Development Plan creates the Federal Ministry of Planning for more effective urban policy.

1979 Nigeria outlawed gas flaring, to be phased out over 5 years. The law was not enforced and in 2008 some 20 billion cubic meters of gas was flared, out of a global total of 150 billion.

1993 Shell Oil stopped pumping oil in the Ogoni Province, but continued to use pipelines that pass through it. The Ogonis are a 500,000-strong community in southwestern Nigeria. They maintain that oil production has polluted their land, destroying their livelihoods of fishing and farming. Shell canceled several community development projects budgeted at $29 million.

1995 Execution of activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, and eight other members of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni for leading protests against oil activities and pollution in the Ogoniland region.