9 minute read

a lotus booms

a lotus blooms

a lotus blooms

Advertisement

by Martin Bradley

In 2011, I was living in the very green Kinta Valley, in the old tin mining State of Perak, Malaysia. In my folly I had designed and built a 5 bedroom house overlooking a fish filled lake, and owned a small durian orchard. That year, after various conversations and visits to Ipoh (bougainvillea city), I had begun a project which developed into 'Northern Writers', based upon Sharon Bakar's 'Readings' idea in Bangsar, Kuala Lumpur. Bakar's 'Readings' is a monthly gathering of like minded individuals who promote literacy and literature through writers reading their work to appreciative audiences. At that time northern Malaysia had no such thing, and I was encouraged to make that happen in Ipoh, Perak.

I was, simultaneously, writing articles about art (plus the occasional short story) and articles about Malaysia for various magazines and newspapers. I was having a small success in having my written work being published. However, I was also having a poor response to my first online blog (which still thrives, and had later become 'Correspondances'). It was that idea, of gaining a wider audience for my writing, and being aware that Malaysia had few, and no digital, art and literature magazines at that time, that prompted some thoughts about digitally publishing a small magazine. In Malaysia, at that time people, with the very best of intentions, would endeavour to start poetry or literary magazines, but would just as quickly lose interest for their own reasons. Poems and short stories sent ended up drifting on and on in the cosmic ether.

I was lucky. In the UK I had been entertained by three years of vocational graphic design at the local art school, wherein I learned about layout, various aspects of graphic design, typography and printing as well as

Sarah Joan Mokhtar from the first issue

photography, illustration etc. After art school, I had picked up magazine and newsletter experience with my university’s in-house magazine, while also studying philosophy. I went on to study Art History and Theory (with one course in Latin American Studies), and a year later Gallery (museum) Studies. At that time there were no convenient courses on Asian/South Asian or South East Asian art, only those run by SOAS, in London. In the world outside of academia, and in various design jobs I was encouraged to write and design magazine and newsletter layouts, for in-house publishing. These experiences were to be invaluable to me (later) as a potential editor and publisher. I remember being offered a post as ‘editor’ of a local (and not to be named) Malaysian magazine, but it fell through when the owner’s young son doubted my InDesign abilities, no doubt because of my age. Of course I was bound to prove him wrong, with 10 years of using InDesign to produce ‘Dusun’ and the ‘The Blue Lotus magazine’.

In the romantic idyll of Perak, watched over by 'Pregnant Lady Mountain' and its flora and fauna, I cautiously began to put together the first 50 page issue of my experimental digital pdf arts magazine. Why digital? Because of the cost that would be involved in the printing and the distribution of a physical magazine. It was at that crucial time that I became determined that the magazine should be free to the end user and, as I couldn't afford to pay anyone to help me, or conscientiously ask anyone to help for free, I took on all the roles needed to produce that magazine, and have continued to do so over the last decade.

But what to name this free arts and literature e-magazine? I was living in Malaysia, so I wanted a name which reflected the country I was in. It had to be

a meaningful name. Thinking about my small durian orchard, and the garden where I was desperately trying to collect and grow the herbs and spices of Malaysia, I wanted a name which would reflect the notion of nurturing, as the magazine was also intended for Malaysian art school students, as a primer for Malaysian art. I looked up the word garden, then orchard in the Malay language, and the word ‘Dusun’ grabbed my attention.

The first few issues of Dusun were intended to be thematic, a quick glance into various Malaysian arts subjects for the uninitiated. Issue one was an all 'girl's issue. It briefly charted the inclusion of women within the various creative arts in Malaysia. That first issue included material by the outstanding Malaysian poet and author Siti Zainon Ismail, as well as the writer Chua Guat Eng, and information about Malaya/ Singapore's première woman artist Georgette Chen, and Malaysia's no 1 female Contemporary Artist Yee i-Lann, and others. The second issue concerned ‘Surrealism’ in its various forms in Malaysia, while the third took a look at ‘Batik’ as an art form, and the fourth ‘Photography’ in Malaysia. Incidentally these issues continue to be available online on Issuu, and that’s the beauty of using a digital platform. Please bear in mind that those first issues were very rough.

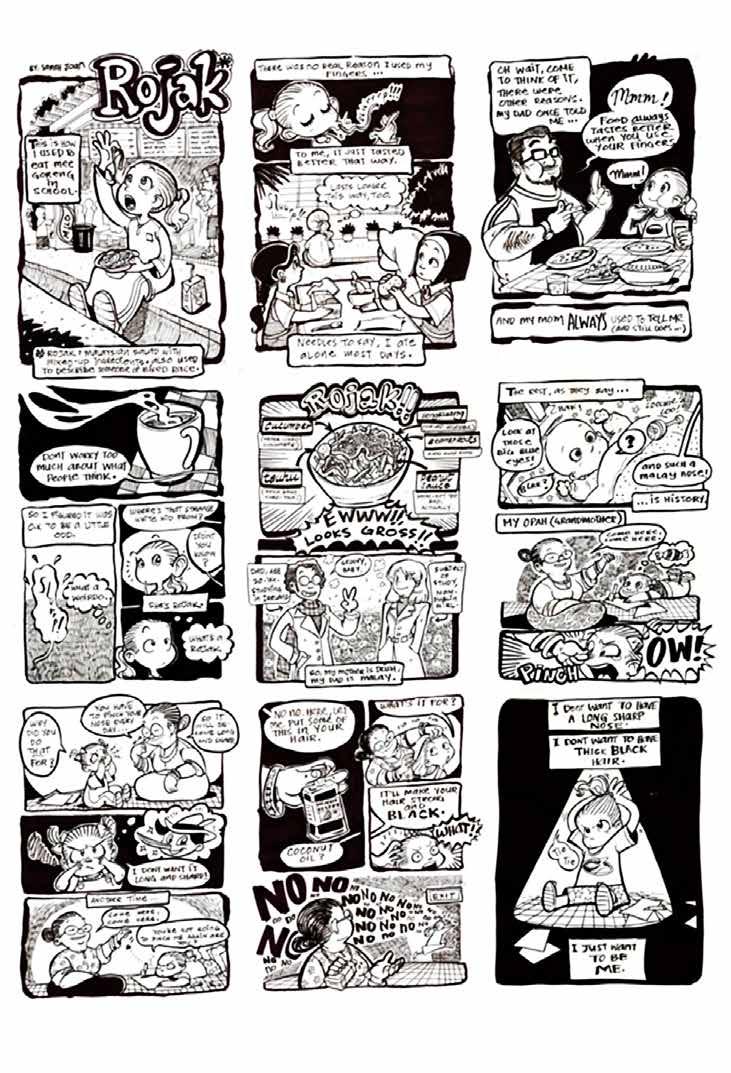

From the start, Dusun was to be, primarily, a visual magazine, with less text and more images than many, more serious, art magazines that I had seen. I didn't want too much discursion or discussion. Those could be found in more academic magazines and journals, which cater to those seeking knowledge regarding Asian arts or cultures . Dusun was to be informative, but for everyone, and not tightly academic.

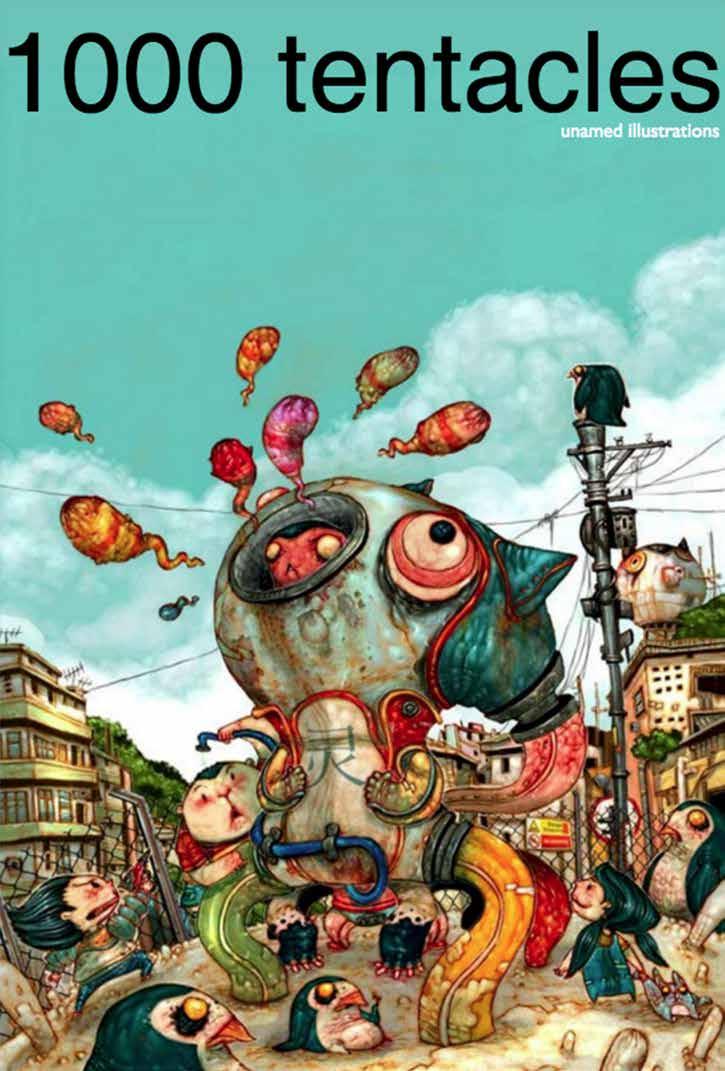

Ismail Hashim from the fourth issue

It was a good start, but being bi-monthly proved to be too much work for one person. Gradually I changed Dusun to Dusun Quarterly, which reflected the difference between being bi-monthly and moving to being published four times a year. The page count also changed, and finally settled at 180 pages every three months. During this time the idea of continuing to be thematic was dropped to allow the magazine to be more flexible in its approach.

On the journey from Dusun to Dusun Quarterly, the premise for the magazine also changed. It was no longer to be a simple Malaysian art magazine, reflecting only Malaysian art, but was re-imagined to encompass the arts and cultures of the whole of Asia, instead of only one country. The idea being to assist and encourage up and coming artists and other creative's, and to bring them to the attention of the world, to promote Asian diaspora in their artistic or literary endeavours.

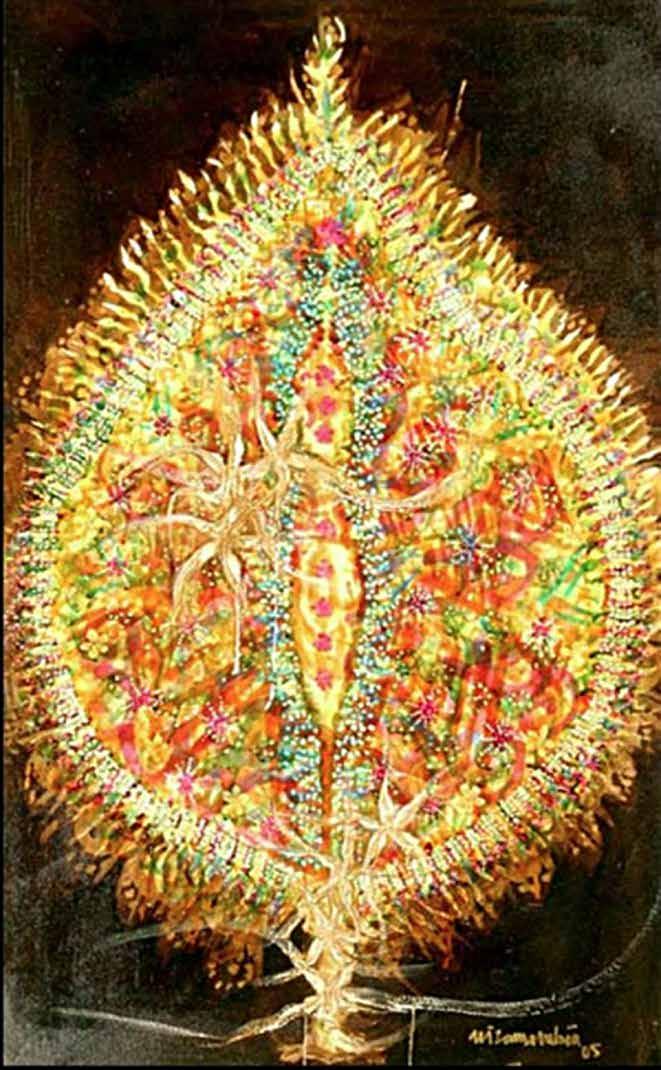

The name for the magazine being 'Dusun' was questioned so many times, by so many people, that I felt a new name was needed to better reflect the change in direction. The Blue Lotus magazine sprang into being.

History records that the blue lotus (N. caerulea) has been the dominant lotus in Egyptian art, and was well known in Mayan, Syrian, Thai and other ancient cultures as a sacred bloom, and with, some claim, mind expanding properties. The lotus flower is also representative of many Asian countries, Cambodia, Bangladesh and India included.

I have been very fortunate to be able to include so much amazing creativity from Asia and Asians in the fifty plus issues of that magazine. It has been, and still

is, a great honour to work with many prominent artists and professionals in the sphere of creativity.

After my change of operations from rural to urban Malaysia (the State of Selangor), I was able to become more personally involved with artists and galleries there, and in Kuala Lumpur. Another, unexpected, change brought me to a lengthier than planned sojourn in Cambodia, from where this issue is currently being published.

I had come to accomplish four days of volunteer teaching of art history to student teachers at a local charity, in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Covid 19 prevented my return to Malaysia, and I have been here, away from my office/studio for over one year.

I have been trying to adapt the Blue Lotus magazine to my new circumstances. These (Special) issues from Cambodia have involved a redesign, as none of my previous files are with me here. Time marches on, and all the back issues of The Blue Lotus magazine, Dusun and Dusun Quarterly, as well as many digital side projects, remain available free on Issuu. Do take a look.

Here's to another ten years then, cheers!

“While Chinese society and art collectors strongly prefer traditional ink paintings, Western gallerists and sympathisers of contemporary Chinese art focus on other styles, most notably Political Pop or Cynical realism. Therefore, economic survival is one of the main reasons why Chinese painters neglect pure abstraction or maintain several very different styles in their work.”

Abstract

Breaking the Ink – Abstract Ink Art in Mainland China

Chinese ink art and calligraphy has heavily influenced Western abstract painting.

Chinese art is mostly presented at foreign exhibitions from a different perspective and abstraction is represented modestly or completely absent. However, abstract art, which to a greater or lesser extent based on the roots of Chinese semi-abstract tradition, finds its firm place in the works of Chinese artists in different countries or regions.

After giving a fundamental analysis of the possible inspiration for abstract ink painting from Chinese art history, and modernist art movements in Taiwan and Hong Kong during the 1960s, which had a significant influence on the formation of modernism in mainland China, and the historical overview of Chinese avantgarde, such as the New Wave 85, the author focusses on abstract ink art in mainland China. As far as the situation in abstract painting is concerned, all important movements, exhibitions are preceded chronologically. Artists' opinions on abstract painting, their contradictions and the questions that this work raises, are observed, too.

Abstract ink painting began to develop with the influx of ideas of modernism in the 1980s, and it was in important factor during the movement of Experimental ink and wash movement in the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century. This movement has organised exhibitions, conferences, publishes catalogues dedicated to the work of its representatives. Then the attention turns to other movements and individual artists devoted to abstract ink art. Some of the artists come to a greater extent from tradition; others try to escape the limitations of ink painting, more or less adhere to traditional Chinese art or calligraphic strokes and techniques. Some of them are more influenced by Western techniques or are attempting to synthesise. What is essential is that they create works that are often of a high standard and in their search, open new ways for Chinese ink painting in general. Special attention deserves the artists standing at the birth of the movement and to those who have so far significantly influenced the whole atmosphere in Chinese art world.