68 minute read

รัฐพล ปัญญาทา

Advertisement

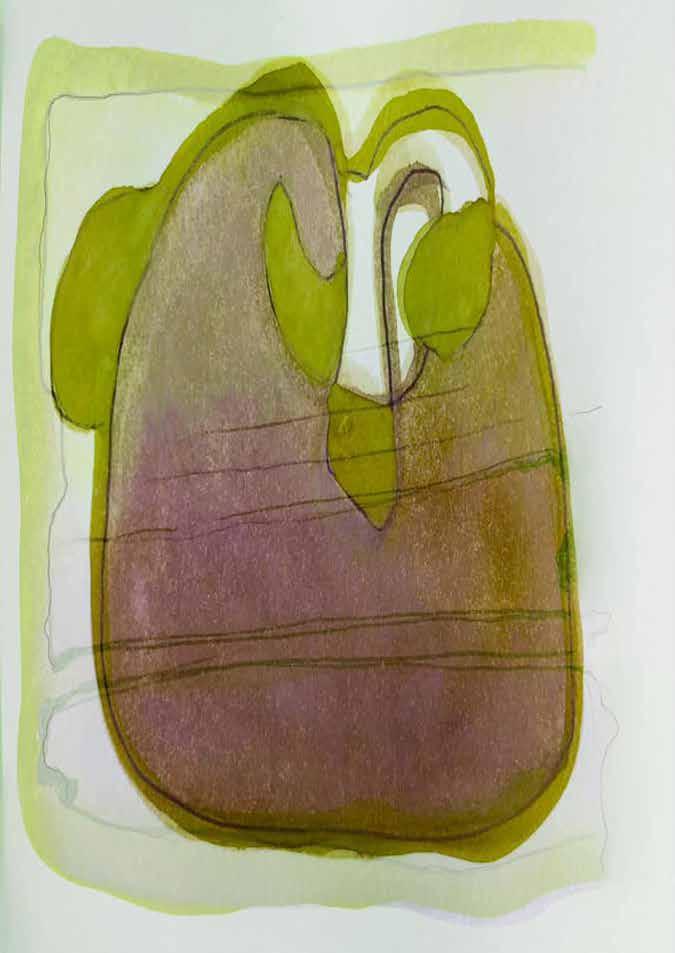

The rhythm of the fighting movements

I was inspired by the style and rhythm that move in the countryside. This creates an interesting dimension and the water is integrated between lines and shapes, such as the shape of a chicken and a gamecock. By using the technique of shading to express the feeling of movement in different styles to reflect the extraordinary and reflect on the strong. Inevitably plays a greater role than weak ones Therefore reflecting this movement in its own way

Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

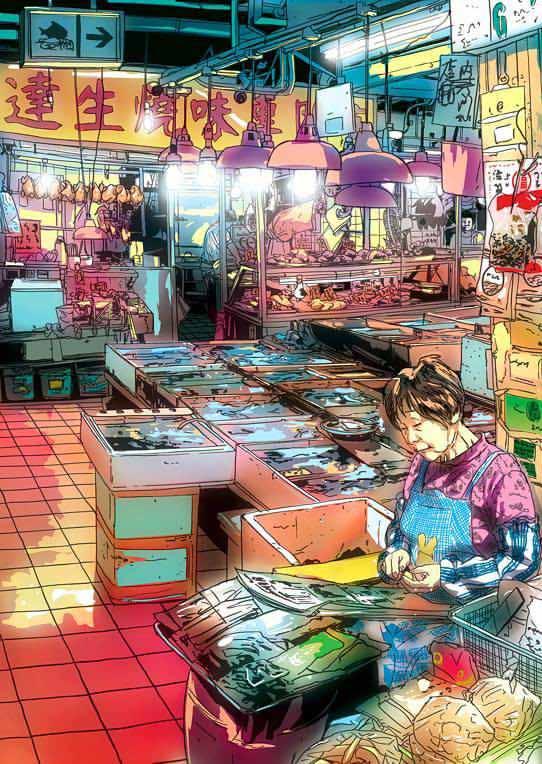

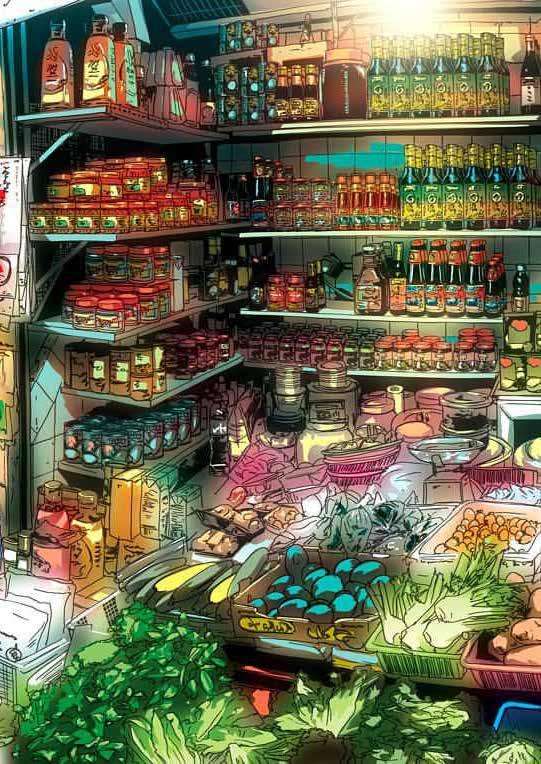

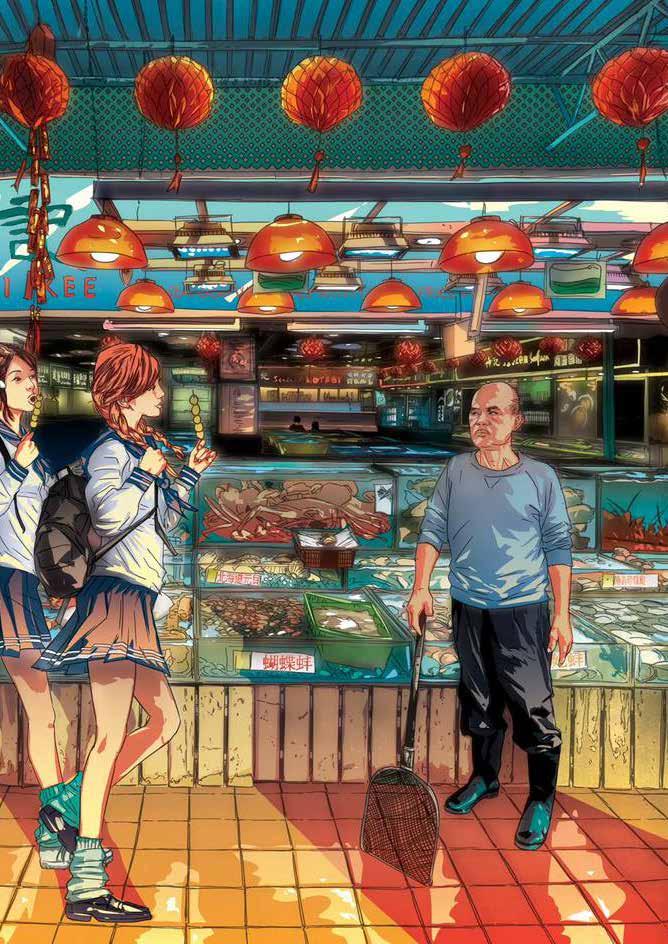

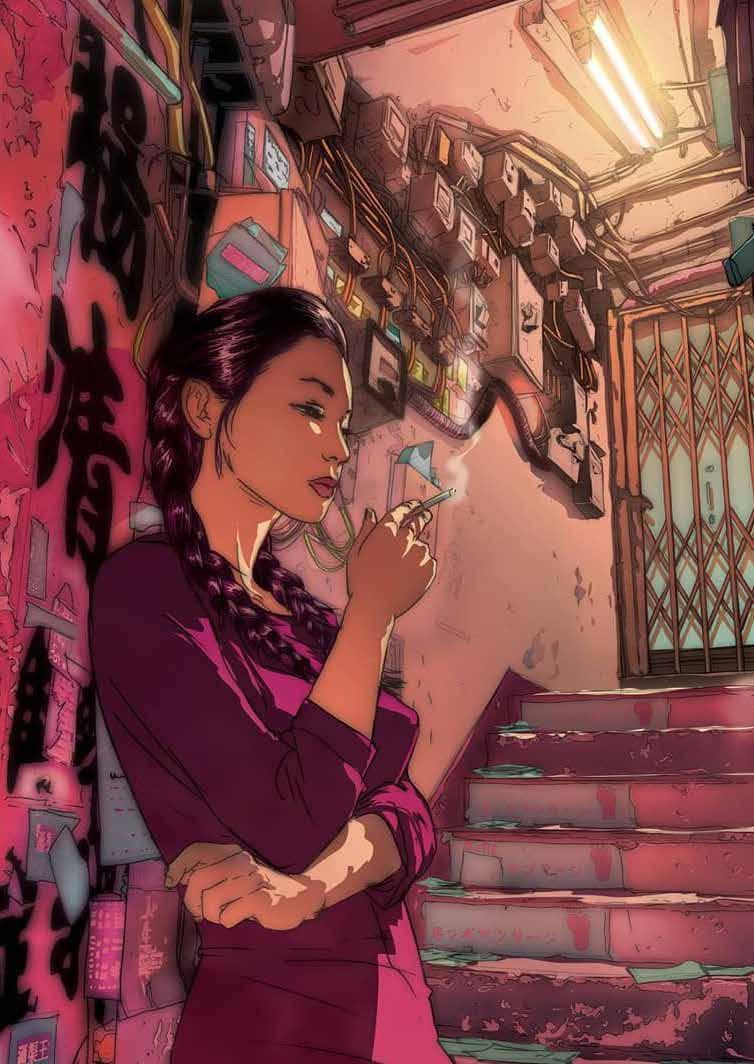

Based in Hong Kong, Taiwanese-American born Jonathan Jay Lee graduated with Departmental Honours in Illustration from Parsons School of Design. He is an award-winning illustrator whose clients have included Marvel Comics, Mercedes, San Miguel, Lamborghini, Lee Kum Kee, Urban Decay, Disney Plus, Ho Lee Fook, Asics Tiger and HSBC. He has been a speaker at Apple, Creative Mornings, Congreso Tad, School of Creative Media, and is named World’s Best 200 Illustrators in Lürzer’s Archive. A former Professor, Jonathan has also has designed and taught more than 20 different courses in Illustration and Sequential Art.

https://punjitrap.com/

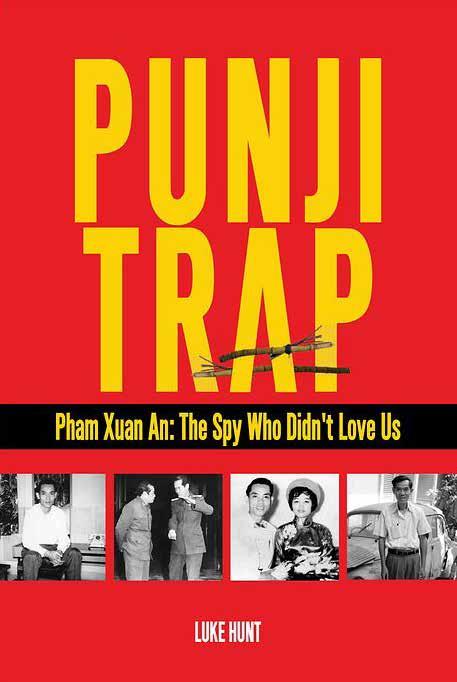

Punji Trap

A slight review by Martin Bradley

‘The technique was simple, the results excruciating’, mentions Luke Hunt in his book (p19). To be clear, a ‘Punji Trap’ is a trap made from ‘punji sticks’, originally named by British Indian Army troops in India’s Punjab. These sticks are fire hardened, sharpened pieces of bamboo with a length of about two feet. To increase their wound-potential, the points are often smeared with poison or animal excreta. A punji stick is low tech, and is easily cut by women and children for traps. These traps were utilised in the Vietnam War, to disable opposition military personnel.

In ‘Punji Trap’, Luke Hunt, a notable journalist and Southeast Asia specialist himself; a former bureau chief for Agence France-Presse in Cambodia reveals Pham Xuan An (pronounced Arn) to have been an (American educated) Vietnamese journalist with an alter ego.

An was a correspondent for Time, Reuters and the New York Herald Tribune who held American audiences in his sway. He was stationed in Saigon during the war in Vietnam and, as well as reporting for the American media, was simultaneously spying for the Viet Cong.

The book looks carefully into the character of the man also known as Colonel An, a national hero with friends in very high Communist places. Hunt methodically delves into An’s interactions during what has become known as the Vietnamese War, with Communist Viet Cong opposing the Viet Minh (ostensibly between 1954 and 1975).

Hunt’s ‘Punji Trap’ is somewhat of an exposé, though not salacious but an intriguing account filling various history gaps in protracted military operations in South East Asia.

Punji Trap (Pham Xuan An: The Spy who didn’t love us) By Luke Hunt is published by Pannasastra University of Cambodia 2018

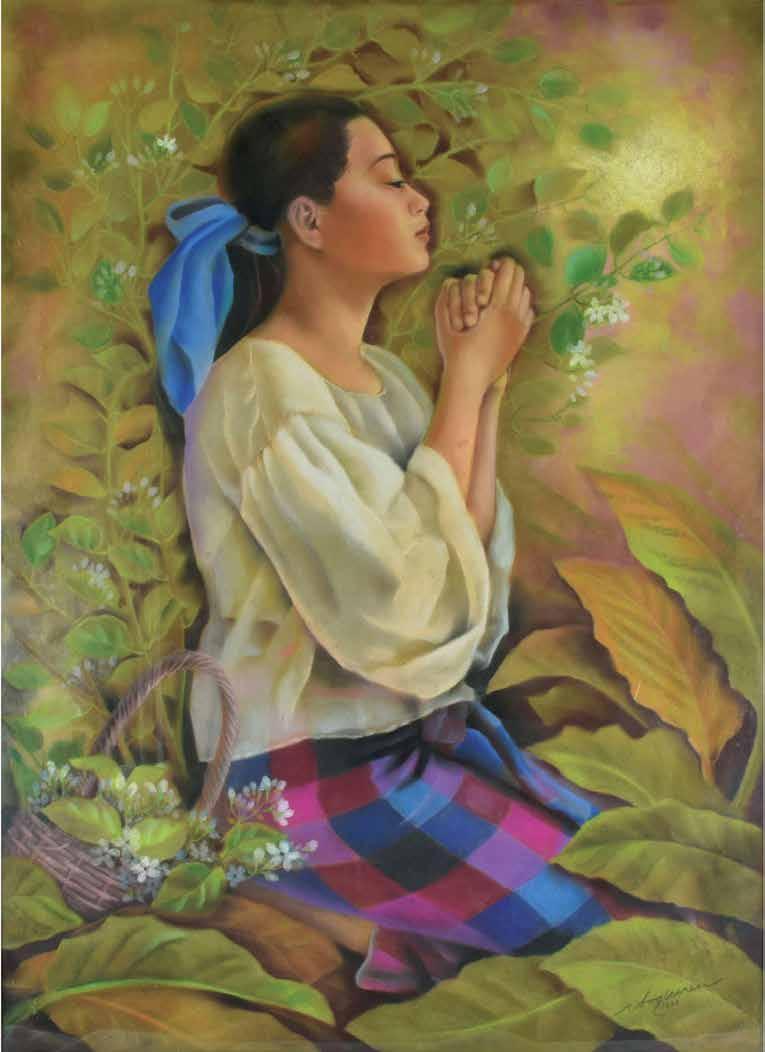

Remy Boquiren

Remy Boquiren

The women that are formed by Remy Boquiren’s elegant strokes have a beauty that is timeless. A beauty that is the stuff of romantic epics, humble yet potent, subtle yet fascinating and most importantly, imbibed with a special kind of strength that distinctly belongs to the Filipina. For Remy Boquiren, anything Filipino has been a point of obsession. Her home in Marikina, quiet and cosy, surrounded by beautiful plants and furnished with wooden and capiz pieces, display her patronage of local craftsmanship that exhibits her sincere love for her roots. Boquiren’s paintings are set apart by a special quality, one that demonstrates her mastery of art techniques. This is the ethereal glow in the figures that is characteristic of her style. “The light comes from the heart,” says Boquiren, “it radiates from within.” There is an inner glow in the Boquiren’s women as if a mysterious fire radiating from a gemstone has been placed at the heart of the figures, highly idealized and unabashedly romantic, as only a woman of the old school could render them. Boquiren calls it “that radiant luminous effect.” The hidden beam frames the benign, beatific demeanour of Boquiren’s women, allowing them to transcend their workaday world where they sell fruits or flowers, weave baskets and generally labour, and where their inner grace lifts them above the hurly- burly of life. They embody Hemingway’s “grace under pressure.” Remy Boquiren has held a strong place in the art world, with many solo art exhibitions under her belt and countless group shows. Not always keen on public appearances, she prefers the quiet of her own home. For now, Boquiren has settled into a comfortable routine, focusing on her art and is kept busy by active participation in her group, Art Wednesday, as well as her weekly Bible study, “that’s what I like, so my life is complete. There’s a balance, you have God, and you have your life and family.” In Remy Boquiren, we see a life made meaningful by faith, family and passion.

Filipina at Sampaguita

Sampaguita Maiden

Slow boat to Prek Toal

Wavelets lap the edge of our boat as we advance northward across the Tonle Sap, black exhaust and fizzing propeller wash trailing in our wake. Behind us dawn is breaking—shards of light, red and orange—staining the sky and piercing the horizon line, harbinger rays of a new day, the second of 2021. Forward of me Yann and Jessie share a word. The former is busy with his camera, clicking shots, filling his memory card as our craft navigates north. The couple—Yann is French, Jessie Chinese—came into my orbit when Yann reached out via email: he had read something I had written, and sensing a kindred spirit written a note of introduction. I am glad he did: I like them both. It is Yann who is responsible for this early morning excursion, my new friend having reached out a week prior about a planned journey to Prek Toal, a wetland reserve at the northern end of the Tonle Sap, the Great Lake: “Would I like to join?”

Prek Toal is home to numerous migratory wetland birds, up to 50,000 through the course of a year, including several that sit near the apex of the IUCN Red List, a register that no creature, concerned about its prospects, wishes to be high on. Personally, as a birding aficionado I felt it borderline criminal that, after fourteen years in the kingdom, I had yet to visit Prek Toal. Self-consciously I felt a ‘bird man’ incomplete: like a visitor to New York who fails to see the Empire State or a sightseer in London who neglects to set eyes on Big Ben. Moreover, having moved to Siem Reap, the town a mere sixty kilometres from the reserve as the stork flies, my laxness had been truly shorn of any excuses. Unsurprising, given these feelings of contrition my response to Yann’s offer had been unequivocal: “I’m in”. We are approaching the end of the open water and entering the mouth of the Sangkae River, a waterway that flows through the province and city of Battambang, home to some of the best rice in the kingdom, rock n roll singers of the country’s ‘golden era’ and, allegedly, some of the most beautiful women in Cambodia. Around us houses appear along the edge of the river—the first buildings of Prek Toal village—though the notion of ‘edge’ is hardly a ‘solid’ affair, the effects of the wet season still at play, water levels high, life river bound. Later, when the dry season enters June and the citizens of Cambodia pray for the arrival of the wet monsoon, the scene here will be different: dry ground and narrow channels. But on this early January morning water still holds swath over village life.

As we enter the village the new day is dawning. From my seat I can see children preparing for the day ahead, washing their faces and brushing their teeth; while on balconies and decks, perched on bended knees and solid ankles, women slice fish and dice vegetables, large pots of rice boiling close by. The bulk of village houses are floating on platforms comprised of plastic barrels and the hulls of old boats; the improvised structures bobbing, like ducks on a rippling pond, in the wake of our boat. From my seat I wave at a family gathered together on a wooden deck, the group sharing breakfast from a large rice bowl. One of their number waves back, as the others look on, muted expressions on their faces. The response is strange: in other parts of ‘Arcadia Cambodia’ a wave usually elicits several smiles and a like gesture in response. But not here, the atmosphere guarded. I think for a moment and then wonder about the ‘virus’: Covid-19 has cast

By Wayne McCallum

a dark shadow across the kingdom, making people suspicious, especially of foreigners, every ‘outsider’ a potential carrier. I put the matter to the side: henceforth I will keep my gestures to myself.

At the front of the boat Yann rises from his seat and starts to remove his jacket. January is the peak of the cool dry season, an interval of a few weeks when it is possible, in the evenings and early mornings especially, to feel that most un-Cambodia of sensations: cold. A few days before a 16°c morning sent locals in Siem Reap scurrying to their cupboards, searching for extra blankets and body layers, the unfamiliar sensation of goose bumps spreading across arms and legs. Temperature wise the thermometer always seems to drop a degree or two just before dawn, meaning that our trip—which started before sunrise, our boat departing from the village of Chong Kneas, north of Siem Reap—was a chilled affair, the three of us digging our hands into our pockets to keep warm. Halfway across the lake and deep pockets had proved insufficient for me, and drifting to the boat’s rear I had taken up a position over its clattering engine. It had proved a noisy and jarring spot, but the additional heat of the motor had proved fair compensation. But Yann’s wardrobe adjustment signals that things are changing: the day heating up, warmth returning to hands and feet. Still the day promises to be mild rather than hot: around 30 or so degrees under a clear sky - perfect conditions for bird-watching in Cambodia.

The motor winds down as we approach our first stop of the day—the local Ministry of Environment ranger station—our boat captain edging carefully towards the side of its jetty. The station is a sizeable affair, several floating buildings abutting the river’s edge with a large concrete block behind, the latter looking stately and official in the crisp morning air. On the wharf there is a hum of activity, with staff— clad in military-style uniforms—moving fuel and water. Next to them two men, perched over a small long-tail, are preparing to head off to an unspecified location. Our boatman shuts off the engine and the world goes quiet, a peaceful calm settling across the river. The moment gives me an opportunity to start a conversation with Lean, our appointed guide for the day. A young man of serious demeanour, Lean works for the Cambodia Bird Guide Association, a local NGO running the tour that has brought us to this end of the lake. His guiding career started in 2014, following several years employed in tourism retail, where he had spent his time selling crocodile wallets and other items to travellers. Born 60 kilometres from Siem Reap, birds had always been around the village where he lived, with Lean coming to realise that guiding people to see these creatures offered a more enticing career path than the selling of tourist trinkets. As the day unfolds he will guide us expertly, answering our questions and ensuring our time at Prek Toal is special: we feel blessed to be partnered with him.

But we are on a schedule and I only have time to exchange a couple of sentences before Lean beckons for us to follow him: he wants to show us something away from the jetty. Following him we walk pass the ranger staff and towards the village’s largest structure, the concrete building behind. Approaching its entrance Lean stops and beckons to one of the pillars anchoring the structure to the riverbed. The said column is festooned with painted numbers, figures depicting the high-water marks of the lake across previous years, the dates tracking back to the

century’s start. The marks are plain but revealing: the trend they show disturbing for the Tonle Sap and its future - for they show a lake in retreat. On the pillar things start promisingly, perhaps too promising, the water in 2000 achieving a level that almost broached the bottom floor of the building. The middle years of the last decade, 2015 and 2016, are the lowest on the concrete support. They were nadir years for the Tonle Sap, when drought and a low lake precipitated fires that turned swathes of forest and wildlife to ash. The year just past, 2020, appears to have been another ‘below average’ year, the water mark six metres below that of 2000 and only a metre above those of the two ‘burning years’.

We leave the pillar and navigate our way up a set of concrete steps toward the door of the building. Inside we follow Lean, passing through dark corridors on the hunt for the next flight of stairs. The building is a large and solid affair, numerous doors hinting at offices and storage areas behind. The entire edifice feels like a statement, of the Ministry of Environment’s role and power in this place. Yet while it looks imposing the interior has a ‘Potemkin’ air, its rooms locked and unoccupied, the hum of officialdom absent from its corridors and stairwells.

We continue to climb, panting from our midmorning excursion, scaling a final set of stairs to our destination: a sunbathed rooftop where something special awaits. That ‘something special’ is a view, an extensive one, a panorama vista of Prek Toal village and the flooded forest beyond. Before us we can see the main channel of the Sangkae River, 80 metres wide, its features unfolding like a road: an artery for boat traffic and home to the village’s 150-plus buildings. Lean lets us catch our breath, waiting a moment before commencing to speak: “You see the houses? Many of the floating ones move when the lake drops. They are towed by boat towards the lake, following the water.” I nod and ponder the quirks of a life lived on a shape-changing river. I can see the benefits: easy waste disposal, a plentiful supply of water for washing and cooking, the ability to travel by boat, the simplicity of a world not attached to solid ground.

The houses we can see are not palatial, a floating church is the closet thing to a mansion, most comprising two or so rooms, front and rear balconies subbing for kitchen, washrooms and communal space. Blue seems to be the most popular building colour—perhaps the village got a bulk deal from a supplier—with their condition falling along a scale: from tidy, to less tidy - more rustic, downward to ‘Titanic’ (in the sense that they appear to be sinking). Unlike a typical Cambodia rural village most buildings—save one-or-two, including the one we are standing on—have tin roofs, tiles judged heavy and impractical. Inside, during the height of the hot dry season, the heat must be stifling, the tin acting like a baking cover. The residents of the floating village do, however, enjoy one advantage over their terra firma cousins when it comes to the temperature: if one wishes to cool off they only have to step off the side.

As the conversation continues I raise a point with Lean, something that has mystified me since our village arrival: namely, why, despite any number of young and old children—sitting, walking and playing on the balconies and the boats drawn up by their sides—have I yet to see a single lifejacket? Such a situation, back in my home country, would have the water safety bods spinning in circles. Lean, in contrast, is sanguine about the situation: “It’s not a problem. Floating village children learn to swim before they can walk.” I gesture to show I have heard, but I remain unconvinced. However, whatever my opinion, the absence of the orange vests suggests that the local population does not consider drowning a noteworthy hazard. I put the matter to the side, happy to go with the flow, even if that flow could spell a youngster’s demise.

We leave the rooftop and turn back towards the wharf: we are on the clock, with one further passage to negotiate before we reach the day’s bird-watching location. At the jetty we change vessels, transferring to a long-tail, its slender frame better suited for the conditions beyond the village. Climbing aboard Yann and Jessie sit forward of me, with Lean at the front, the seats between filled with our bags and equipment. Our original boatman has disappeared— he has secreted away to another location and will wait there until we return—and in his place we have been teamed with a ranger from the station. He is young and enthusiastic—traits he expresses immediately—pulling away from the jetty in a cloud of exhaust, barely giving me time to settle as we get underway. As we move swiftly up the river I watch on as houses flash by, children and adults staring as we race past, the sight of Europeans unfamiliar after ten long ‘Covid months’. At the outskirts of the village the boatman pushes the throttle down further, accelerating us into a side-channel of the

Sangkae, Prek Toal village disappearing behind us in a rooster tail of trailing water. Above us the sky is still clear and blue, with just the occasional fleck of white to break the azure monotony. Down on the river, meanwhile, the day is warming nicely, pushing memories of the morning’s chilled start to the side.

We speed onward into the heart of the Prek Toal reserve, our journey taking us through alternating patches of open and confined water. The tighter spots are dominated by water hyacinth, a native of South America that, since its arrival, has expanded quickly across the kingdom, forming dense mats that have overwhelmed many of the country’s lakes and trapeangs. The plant’s invasive strategy—driven in part by copious seed production, up to 3000 seeds per plant—causes life-changing alterations to local ecosystems, depriving submerged plants of sunlight, and fish and other aquatic life of oxygen. For those depending on waterways for navigation, meanwhile, the thick mates quickly limit boat passage; the maintenance of routes—including the one we are now on—requiring continuous human toil. Frustratingly, one is unable to feed the plant to livestock, its predilection of bio-accumulating harmful toxins making it dangerous, even fatal, to domestic animals. Behind us, in Prek Toal village, steps have been made to create something positive from the troublesome interloper; a local NGO, Osmose, collaborating with villagers to turn the plant’s fibrous stems into weaved hammocks, mats, and bags. As we push on a wetland immigrant from South America is not the only hazard we face. In other places branches of another invasive, mimosa, stoop across our path, whipping at our faces and scratching our checks. The danger posed by the plant does not deter our boatman though, the man impervious to our well-being, the long-tail streaking through the tightest of draped channels with barely a change in speed.

Above, when it is safe to look, the sky is transforming, its blue canvas filling with feathered life. Some of the birds we can see are easy to identify. Most common are Asian open-bills, a stork of medium size that owes its name to a peculiarity of its strong beck: a visible space between its upper and lower mandibles. This adaptation allows the bird to readily crack and devour snails, the alien golden apple snail being a particular favourite. The proliferation of the snail, following its introduction to Cambodia in the early 1980s, might account for the rise in the country’s open-bill numbers, a change at odds with the trend for the majority of the country’s other wetland birds. Between the storks I can distinguished others: adjutants, spot-billed pelicans, oriental darter, painted storks and blackheaded ibis. The sky above has transformed into an avian airport, with birds stacked along flight paths— taking off and landing—feathers and bills subbing for aluminium and carbon. Remarkably, as we press on, the numbers seem to increase further, the heavens saturated with a mass of flying bodies, the diversity and scale astonishing. Below, crouched in our boats, our presence is peripheral: we are mortals relegated to the role of spectators, an audience to a panorama that underscores the magnificence and fecundity of Cambodia’s ‘Great Lake’.

Tonle Sap, Southeast Asia’s largest freshwater lake, is a waterbody that has anchored civilisations, ecosystems and cultures, and which remains— today—a crucial part of a Mekong system that maintains life and prosperity across the region. To gauge how essential the lake is to Khmer culture one only has to journey to the walls of the Bayon Temple, inside the Angkor Archaeological Park. Here the temple’s stunning relieves include the depiction of an epic over-lake battle between Cham warriors and soldiers of the nascent Khmer empire. Etched into the sandstone are boats loaded with upright male figures, colliding and fighting, fallen bodies being devoured by crocodiles below. Beside its defensive qualities the founders of the Angkor Empire saw numerous other advantages in siting the hub of their civilisation close to the Great Lake. Its copious resources—fish, water herbs and vegetables, shellfish and, of course, plentiful numbers of birds— offering up opportunities that other locations could not, a bounty compensating for the area’s infertile soils.

From a physical perspective the lake plays a crucial role in the seasonal flow patterns of the lower Mekong system, a catchment body that 150-million plus people, as well as countless millions of fish and other species, rely on for their health and survival (it is calculated that 70 percent of the protein consumed by Cambodians originates from the Great Lake). Anchoring the system is the annual waxing and waning of the lake’s surface, a process intimately linked to the seasonal passage of the monsoon. In May, as the rains of the wet season approach, the lake is at its lowest, villagers taking the opportunity

to cultivate exposed mudflats, caging a crop from its fertile soils before the moist monsoon arrives. Onward, from late June to mid-November the Tonle Sap slowly fills, advancing across its floodplain, reclaiming ground surrendered over the dry months, flooding the forests of Prek Toal and drawing close to the edges of Siem Reap city. As the wet monsoon comes to a close the final weeks are ones of anxiety for the stilt-house inhabitants living around the lake, the occupier’s ever-conscious of the water level, and how close it is to their raised floors.

Crucial to the annual cycle of the lake’s rise and fall is an event that occurs at the confluence of the river that drains the lake—confusingly also known as the Tonle Sap—and the Mekong River, into which the former flows (at Phnom Penh, the nation’s capital). Here, usually in August, the lake’s outlet river reverses flow, the more substantial waters of the Mekong pushing the tributary’s waters back towards its source, the Great Lake. This flow reversal accelerates the expansion of the Tonle Sap, kindling an explosion of fertility—a medley of water, plants, insects, fungi and other life combining in a hot-pot of productivity—yielding copious food for a host of species, including the lake’s rich fish and bird populations. The rising water also carries nutrients and minerals into the lake, washed from the kingdom’s plains and mountains, adding a further injection of productivity into the Tonle Sap and the lower Mekong system. This combination of elements, bracketed by copious amounts of sunlight, energises the ecosystems of the Tonle Sap, turning them into turbo-charged motors of life, absorbing, producing, consuming and reproducing, creating productive pockets of water and forests such as found at Prek Toal. Unsurprising, given its numerous environmental and social qualities, the international body—UNESCO—formally recognised the values of the Tonle Sap in 1997, when it designated the lake a biosphere reserve.

Today, predictably for the Anthropocene age, all is not well in the depths and across the riparian margins of the Great Lake. Most concerning, given its pivotal role in the state and function of the Tonle Sap, is the year-on-year fall in the lake’s wet season highs, the annual zone of inundated trending downward as the century unfolds (as shown on the Prek Toal village pillar). As these levels retreat the seasonal explosion of productivity that anchors the lake’s biodiversity has been placed at risk, reducing the resilience and scale of its unique aquatic and riparian ecosystems. This downward trend has had flow-on consequences for the life-cycles of the lake’s inhabitants, including certain species of fish, which time their spawning to the inundation of favoured freshwater zones.

Climate change, propelled by global warming, and developments in the wider Mekong catchment are considered key drivers of these changes. Climate change has resulted in the alteration of rainfall patterns; wet seasons arriving later and ending sooner, the rainfall less intense, from the cycles of the past, with flow-on consequences for annual lake levels. Beyond the Tonle Sap the construction of dams has intensified issues for the water hungry lake, with the retention of flows behind impoundments in the upper and middle Mekong reducing levels in the river’s lower reaches. This has duly impacted on the extent and length that the Great Lake’s outlet—the Tonle Sap River—reverses flow, with upstream consequences for the annual cycle of floodplain inundation.

Also concerning has been the progressive reduction in the extent and richness of riparian forest around the edges of the Tonle Sap. A 2020 National Geographic report highlighted the main drivers of this deforestation: removal of trees by land developers, fires—some deliberate, others caused by parched drought conditions—and the ‘death by a 1000 cuts’ of trees cut to stoke village cooking fires. It was a culmination of these factors that contributed to the tragic forest losses of 2015 and 2016, when large swathes of tinder-dry woodland disappeared in clouds of ash and smoke.

Yet amongst the trees and shrubs of the flooded forest, staring up at the canvas of the sky, the air alive, vibrate and humming, it is hard to imagine that the lake’s future is in doubt: the vista fragile and endangered. We move on, our boat drawing us closer to the heart of the reserve.

We have arrived: behind me the engine dies as the boatman glides our long-tail through a flotilla of branches and past a moored long-tail, our vessel coming to rest with a gentle ‘bump’ against a large and solid tree. Beyond the boat a couple of ranger staff are talking quietly, their voices amplified in the stillness, the pair engaged in repairs to the steps of a ladder: a set of rungs that we will have to climb to reach the bird-watching platform above.

The platform sits above our heads, spanning the branches of the tree that our boat now rests against, the structure a rudimentary affair of wood and nails. ‘Will it hold our weight?’ I wonder as I gaze upward. As I consider the possibilities a sound drifts past my ears: faint but discernible. It is the hum of wings and bird chatter—cries, remonstrations and avian small talk—storks, egrets, adjutants and others engaged in gossip along the Prek Toal bird wire. The sound is inspiring. I want to climb to the top of the platform now! And bugger matters of structural integrity.

As if reading my thoughts Lean points to the ladder and speaks: “Okay, follow me.” First, though, we must wait a moment, a ranger hammering a last nail into a rung. “Please”, our guide adds as the sound of the final blow fades, “be careful, the steps are not strong.” In front Yann steps tentatively onto the first rung, checking its strength with the weight of his shoe. Jessie follows, gripping a rail as she commences to climbs. I follow, a few metres behind, ascending each step with a cautious tread. Amongst us, loaded with cameras and other electronics, no one wants to fall; the water beneath is two-metres deep, making any accident an expensive and perilous affair.

As I climb more of Prek Toal is revealed: an expanse of flooded forest and water unfurling with each step. Half way up I pause to take in the view, using the moment to catch my breath as I take in the surrounds. Above, Yann and Jessie have already reached the platform’s top, Lean following behind. I can hear them talking from my position below, the trio preparing their equipment for the day ahead. I continue to climb—one step, two, three, four— ascending above the tree-line of the flooded forest. I ascend two more rungs and I am there: the base of the wooden deck. Carefully I stretch out my arms and climb through the platform’s man-hole; its not easy, the space narrow and awkward for a gangly and back-pack laden European. Below, the waters of the reserve lap gently against our long-tail, the surface rippling in a mid-morning breeze. On the platform Jessie and Yann are already at work, binoculars glued to their faces, the pair scanning the trees and sky close by.

Jessie: “What is that? A large white bird with a red stain on its tail.”

Lean does not need to see the bird to know the answer: “Painted stork.” Lean, peering through his binoculars now: “You mean the one on the left? Open-bill. Actually the one to the right is one as well.”

I join them, putting a set of binoculars to my eyes, searching the surrounds where my friends are looking. The spot is a large tree blossoming with birds: a wetland bird metropolis. I scan the tree unable to home in on Yann and Jessie’s birds, but it is of no concern, for a multitude of others: storks, pelicans and the occasional adjutant fill the space, the tree’s branches visibly bending under the weight of their plumage. I have never seen anything like it.

Below, the rangers who greeted us when we arrived are talking quietly. I wonder what they make of our intrusion; for it seems that our viewing platform also subs as their home and office, with batteries, walkie talkies and bedding filling its corners. Lean, seeing my glances, guesses what I am thinking, and fills in the details: “The rangers spend fourteen days here each shift, sleeping and eating on the platform. In the day they paddle out on patrols and to count birds.” He stops, pondering what else to add: “It’s a hard life. Young people don’t like it, the older rangers seem to have less problem.”

I glance around the platform with renewed appreciation. It’s a very basic affair, like the ladder below, fashioned from fallen branches and bamboo collected from nearby trees, nay a dressed piece of timber in sight. Its roof—at least it has one—consists of thatch, with a plastic sheet in place to ward off the worse of the rain. Behind where we stand is a single wall, a place to rest your head, but the other sides are open and exposed. Personally I see little that would entice me to pass fourteen days here. In the midst of the wet monsoon—when squalls sweep across the Great Lake—one would be exposed to the elements. Transported to the hot months of the dry season, when temperatures rise above 38°c, life on the platform would be sweaty and stifling, the absence of electricity making the breeze from a fan the thing of piped dreams.

As I meditate on the whims of platform life there is action in the trees, a cloud of plumage, egrets, storks and others ascending into the air; overhead a greyheaded fish eagle glides by, its raptor eye looking for opportunities, its appearance injecting a bout

of nervous energy through the forest. To my right Yann is trying to capture the action with his zoom lense, but things are not going to plan: “It’s hard. I thought we might be closer. The lense is not strong enough.” Behind us Jessie is trying to improvise a solution, doubling a spotting scope—set-up earlier by Lean—with the camera lense of her smart phone. She delicately manoeuvres it over the scope’s eyepiece. It is a challenge, working the angles, but then Jessie sees something and presses the screen: once, twice, more. Excited to see what she has captured Jessie moves away from the scope and sits beside me, scrolling through her phone’s gallery as she does so. The first pictures do not impress, they are dark and out of focus, but then she sees something that pleases. Jessie passes the phone across to me so I can see: it is a painted stork and two pelicans, the image way better than anything I have managed to photograph.

“Not bad”, I offer, “ . . . actually bloody good!”

Jessie smiles as she hands her phone across for Yann to see.

With the scope free I rise and move across to where it is standing: I want to see if I can master the ‘Jessie method’. Behind the scope I take out my Huawei and balance it over the eyepiece, moving my phone carefully from side-to-side, trying to capture something through the phone’s lense. At first there is nothing, the screen blank. I move the lense a millimetre to the right and a shaft of light appears and then is gone. ‘Close’ I think, moving the phone minutely to the right. Suddenly an egret and two storks fill the screen. They are close, very close, their wings, beak and stick-like legs clear to see. I press the camera button. Next, to my left, I see a painted stork on an exposed branch. The bird looks regal with its white plumage and stately demeanour: perfect for a photo. I move the scope carefully to where the stork is perched. Again my screen goes blank. ‘Damn!’ It takes surgical precision to coordinate between the eye-piece and the lense of my phone. I keep trying, making minute adjustments as I seek to compensate for the unevenness of the platform. Suddenly there it is! The stork is on my screen, upright and clear. I press the screen once and then again, shots filling my gallery. In front of me the stork is being agreeably cooperative, upright and still. I keep shooting, filling my phone’s memory. Behind me someone moves, shaking the platform and jarring the scope: my phone screen goes blank I move away from the scope and search for a discrete spot to review the results of my improvisation. In a corner I lean against a rolled mattress and start scrolling through my phone. The first few images are blurred, difficult to see. But then I find it, the painted stork in all its glory. The image is stunningly clear, not of print quality but sufficient for a post or a share. Shooting through the scope of the lense has added a vignette effect to my images; it’s a nice effect, like that from a filter. Inside I feel satisfied, my inner MacGyver satiated. But my phone’s battery is draining rapidly, and there is still a lot of day in front of us. It’s time to let my phone rest. I close the gallery and place it on stand-by.

One o’clock finds our party munching on snacks, the food brought from Siem Reap, catering decidedly lacking on the platform. Between us the conversation turns to the activity that has drawn us to a tree and a platform: bird-watching. On the surface bird-watching seems a straightforward affair, the subject and activity laid out in its title: ‘bird’ and ‘watching’. But as you dig further things become more complicated, the way they usually do when simple matters collide with human passion, status, and the wheels of commerce. For I have known people who have sacrificed weekend rest, midnight dreams, comfort and warmth on a stormy day, shade on a sweltering afternoon, as well as family holidays and financial security, all in the pursuit of something generally less than 30 cm in height, weighing 500 grams or less, the entire ensemble covered, mostly, with feathers. Moreover it is a creature whose preferred residence might be an inaccessible tree, a soggy ditch, a putrid swamp or a sun-scorched plain. Birds and bird watching, let’s be clear, can breed dedication, passion and financial ruin—it might even kill you—but then again, how else are you going to spend your free time?

For the uninitiated, those free from the ‘cult of the feather’, the question of what rouses such devotion is a reasonable one, with different folk having sought to explain. Mark Cocker, author of Birders Tales of a Tribe, ascribes it to the very nature of birds themselves - the freedom they exhibit and their capacity to escape (Cocker even suggests that there is a ‘erotic’ dimension, although what this is he fails to explain, leaving us only to imagine). Personally I prefer Simon Barnes’s take on the subject, his thesis set forward in the opening chapter of his excellent

book: How to be a Bad Bird Watcher: “Just because looking at birds is one of life’s greatest pleasures. Looking at birds is a key: it opens doors, and if you choose to go through them you find you enjoy life more and understand life better.”

For me Barnes’s words lie down the essence of why birding—and a myriad of other activities that require us to take measure of the world around us: surfing, mountain climbing, sailing, fly-fishing etc.— are special. For bird-watching immerses us into the natural world, requiring us to take heed of the ground, the sky, trees, shrubs and grass, the direction of the wind, the fruits and seeds in season, the month and season, the temperature and the light. Via this process our consciousness is energised, our attention and awareness focused; we are transported—as if we have wings—beyond the world of ‘self’ and outward to the natural world of the ‘other’. It is a world that is tactile and physical, a place that reaffirms our wild side, available to all at an entry level that is low – a simple look out of a window will suffice. Plus birds can fly, and amongst all the people that I know, well, no one can do that.

Speaking for my colleagues on the platform, with the exception of Lean, I imagine that done of us would match Cocker’s notion of birding worth: we are strictly at a Barnes-level of admiration. Yet here we are, perched in a tree in the middle of a flooded forest, the four of us engrossed by what is occurring around us. And it is the feathered inhabitants of Prek Toal that have drawn us here, creatures as magnificent as they are fragile and vulnerable. And on this January day, scanning he trees and sky around us, I cannot think of a better place to be.

The conversation moves on to the people that Lean has guided and what they have been seeking from their excursion to Prek Toal. Lean: “Most of them are keen to tick a bird off their list; to see something they haven’t seen before.”

Bird lists: The ‘list’ holds a special place amongst those for whom the feather burns bright. And like mastering a surf-break, conquering a peak, or catching a ’10-pounder’ (trout), too true bird afficiardos their merit and status is bound by the depth and quality of their list. Accordingly, meeting for the first time, the sharing of lists is what serious birders get down too when the warmth of the handshakes has cooled. Of the lists themselves, whether a person can ever see the 10,000 or so species of birds that inhabit the world is a mute point, for what is considered key is the rarity or difficult of the birds seen and catalogued: the harder to see and more rare the better.

Lean again: “The lists are important. We want our clients to see the birds that are special for Prek Toal, the greater adjutant and the milky stork.”

I can appreciate why seeing these two birds would be special. But all the same, while they are being ticked, I hope the seasoned birder is able to appreciate the others that give Prek Toal its diversity and richness: the black-headed ibis, the open-billed and painted stocks, the cattle egrets and others. True, these may be birds that they have seen hundreds, perhaps thousands, of times before, but what makes this place magical is not just two birds: it is the wider number that make it a community of feathered delight.

Next to me Yann raises a new topic: the question of who is the ‘expert’, the birdwatcher or the guide: “On your website it says your team has guided some of the best bird-watchers in the world. But if it’s the guide who does all the work—takes them to the place and points to the tree where the bird is—can the bird-watcher really ‘great’, shouldn’t it be the guide?”

It’s a fair point. After all if you paid for a meal cooked by the world’s greatest chef could you claim the status of a globetrotting gourmet? For this, in a round about way is what Lean and his colleagues do: serving up the birds for the bird-watcher to consume, albeit in a bifocal and non-calorific way. In such a relationship isn’t the guide the ‘expert’?

Returning to the topic of bird-watching and my personal place on the scale of endeavour, like Mr. Barnes I do not desire to be numerically complete or too see the rarest and most difficult, for it is not these things that inspire my love of birds. Rather, I am inspired by the wonder that comes with each bird I am able to see and hear, and inside I am as happy to see my one-hundred painted stork and fiftieth spot-billed pelican as I am any other: each bird its own touchstone to the natural world. That said I was happy to look down the bird scope, under Lean’s tutelage, and see the first and only milky stork of the day.

I enthralled by the flight-life around us, our guide answering questions and offering the occasional word as the sun drifts round. For the three of us each hour on the platform is a boon. Usually, Lean informed us earlier, customer time is restricted to thirty to sixty minutes, a regular client stream limiting the time available on the platform for each party. But in the new Covid-world paying birders are now as rare as the elusive milky stork, leaving us with extra hours to enjoy the sights and sounds of Prek Toal: lemonade from Covid lemons - we consider ourselves fortunate.

On those occasions when random tour groups do appear, we descend the steps and let the new arrivals enjoy the scenery. These visits never feel like an intrusion, for we know we are fortunate to enjoy so much time on the platform; and resting on the seats of our long-tail—where we retreat when the visitors arrive—we use the time to scroll through our images and rest our eyes. But soon enough, for they never stay long, when the group’s depart, we make the long climb to the top of the platform once again, our legs stretched and souls re-energised, our souls excited by the opportunity to see Prek Toal’s ‘bird world’ once again.

With the clock nearing 3:30 PM Lean tells us that we must soon depart. Lunch, now an early dinner, has been arranged for us back at the village, and we do not want to disappoint the women who have prepared it (we might be their only customers this year). After our meal we face a two hour return trip to Chong Kneas, a route that needs to be completed before dark, before navigation becomes a hazardous pursuit on the Great Lake.

I ready to go, caging a glance of the sky while I organise my pack, the air above cool and clear. Overhead I can see, rotating in a wide circle, a helix of birds—storks, pelicans, adjutants, others— circling round and around, a world of blood and feathers layered in the firmament—some closer, others higher—the spiral ascending high into the sky, everything held aloft by a mid-afternoon thermal. It’s a remarkable sight. “Amazing”, whispers Jessie. Beside her Yann and Lean are staring heavenward too, the four of us hypnotised at what is unfurling above our heads. No one else speaks: Jessie’s word has captured the mood perfectly. We gaze on, spellbound, all the uncertainties of the terrestrial world surrendered to the majesty above. Twilight is giving way to dusk as our boat approaches Chong Kneas, human life settling down for the evening, meals being prepared as the working day closes. The four of us are tired, hardly speaking, the early start and the long day taking its toll. The return trip across the Great Lake was a meditative affair: an opportunity to reflect on what we had seen and the conversations shared. And as our boat pushed into the monsoon wind, the breeze cool after the heat of the afternoon, there was time to think about the day and what it has meant for our souls. True there are many thoughts, many ideas, but if asked to put them all into a sentence or statement I could think of nothing better than the word uttered by Jessie a few hours prior: “amazing”.

The year before me promises more uncertainty and loss—the Covid shadow ever-present, an existential threat as much as a personal one—and inside I wonder what the world will look like in twelve months hence. It seems clichéd to write that the last year has underlined the necessity of taking nothing for granted: of appreciating, no matter how small, miracles and wonder when they appear. But clichés are what they are because they are true, so as our boat docks, the boatman throttling down the engine as we approach the gangway, my mind is back at Prek Toal, my face staring skyward at a circle of feathered delight: a soaring spiral of wonderment. And now, as I leave the boat and make my way toward the shore, an often quoted declaration from the pen of Emily Dickinson comes to mind. They are words that, in this moment, have never seemed so true: “hope is the thing with feathers.”

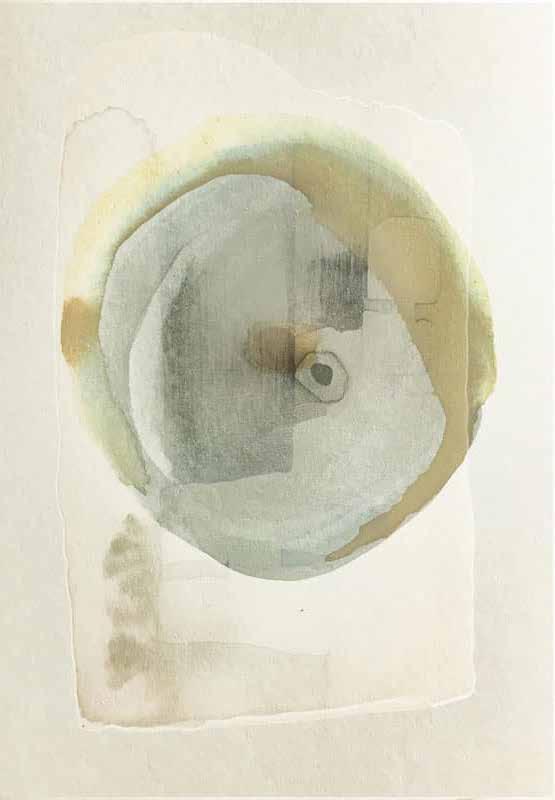

Hildrun Rolff

Miniatures

MINIATURES

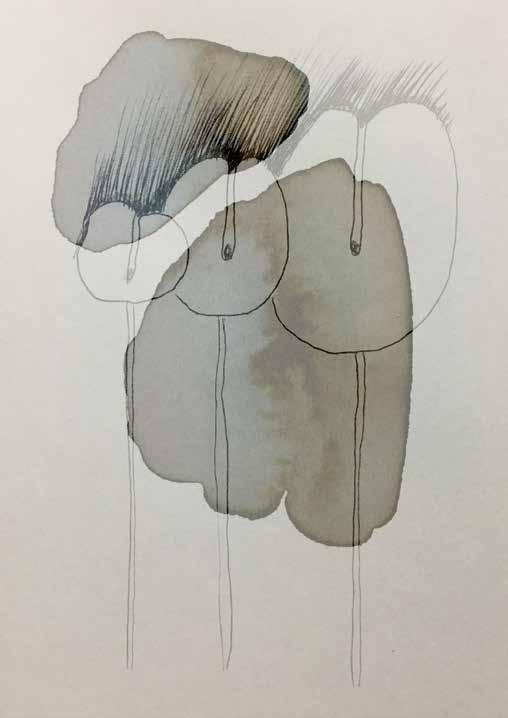

The small iconographic notations shown here were created in the context of research questions in the field of art therapy. This more pictorial examination of therapeutic themes, forms the basis for findings and new contextualization. E.g. in the area of imaginations, which can be used as lasting condensations of positive effects experienced in art therapy, important deepening of the theory arose through ideas found in annotating.

WAITING

Working with interactions. We look in the "outside" for the questions living in us, and "outside" asks back for us "inside" . Physiology of asking for kinship. Looking for weight to become strong inside (bone-stonecell life).

SYMBOL - NOTATIONS

Inside outside themes in the work with imaginations

SYMBOL - NOTATIONS

Everything is always already there. The future is in childhood and in it the past is aging. Early and late selections.

HILDRUN ROLFF

Alanus University of Arts and Social Sciences Faculty of Art Therapies and Therapy Sciences Institute for Art Therapy Head oft BA Art Therapy/Social Art and the Artistic/Scientific Further Education Art Therapy interdisciplinary Medicine and Psychology.

Rolff was born in Hanover in 1956. She studied sculpture, painting and art therapy at the University of the Arts in Social Ottersberg near Bremen in the 1970s, and worked as an artist in her own studio in Hanover, Munich, Hamburg and, together with her artist colleague Eckart Wirz, founded the Kunsthaus Kochel am See near Murnau, an exhibition house for contemporary art, a studio house and a producer's gallery. Prints, large-format oil and acrylic paintings were created in her own studio in Munich. Today the artist limits herself mainly to materials that can easily be recycled, to photography and, since 2008, to digital art - mixed media art. She works as a professor for art therapy at the Alanus University for Art and Society near Bonn.

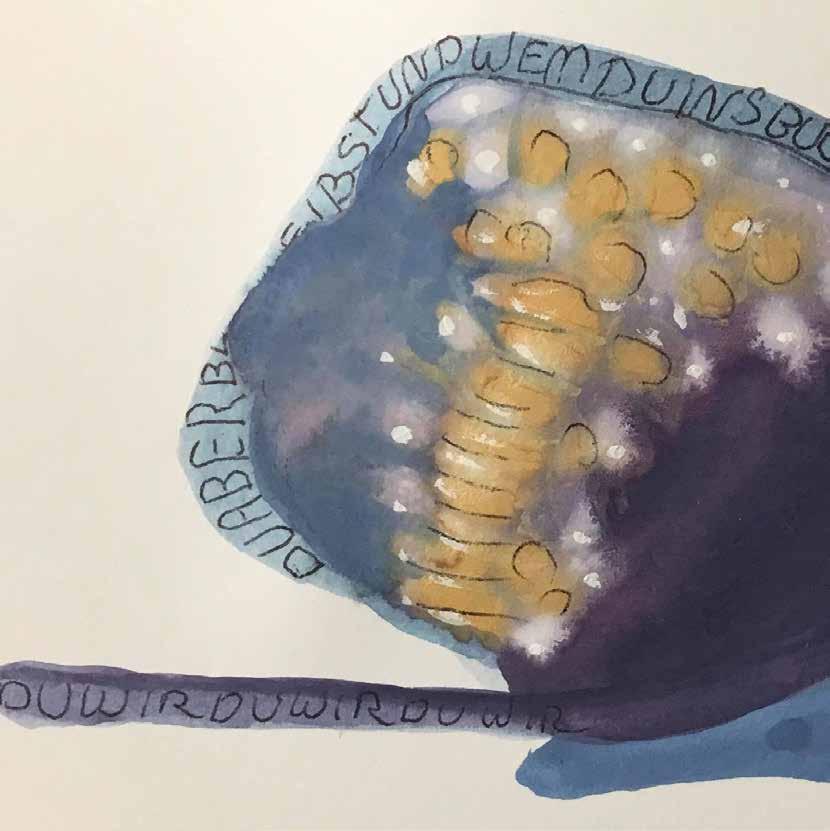

NERVE WORK

Packed in cells - wrapped times - associations to the intermediation of form and substance as basic principles.

Working with “functions of single cells in connection with their form” and the effect of forms of art on functions in the living interaction of body and soul.

THE ARTIST’S PLAY WITH WORDS

Wisdom in the conceptualizations. Iconic dedications.

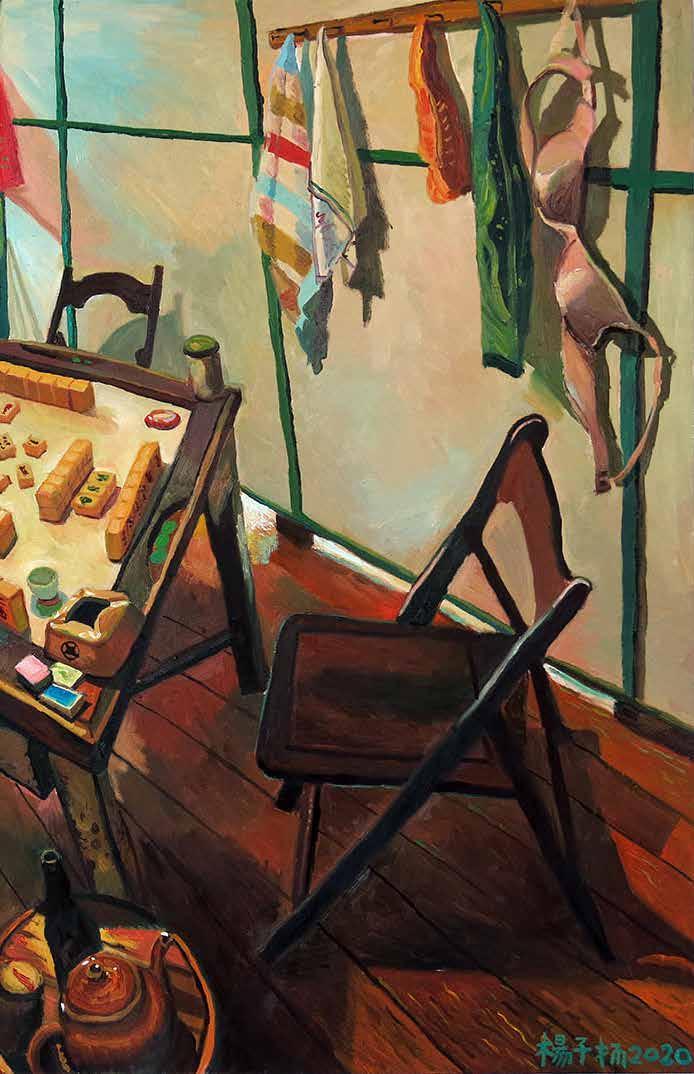

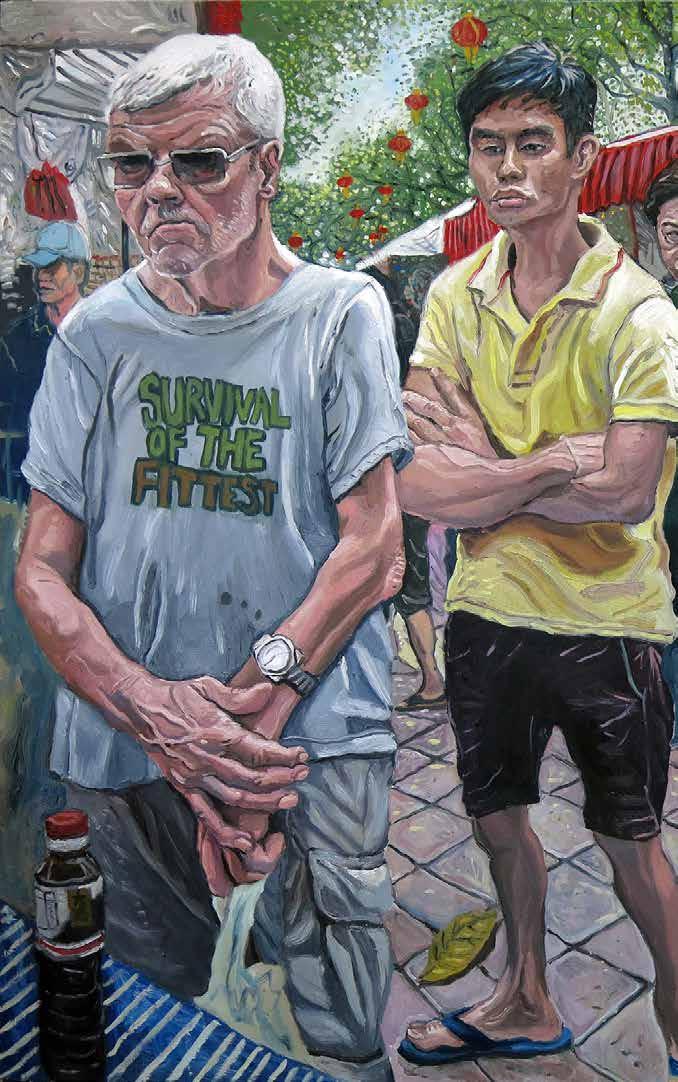

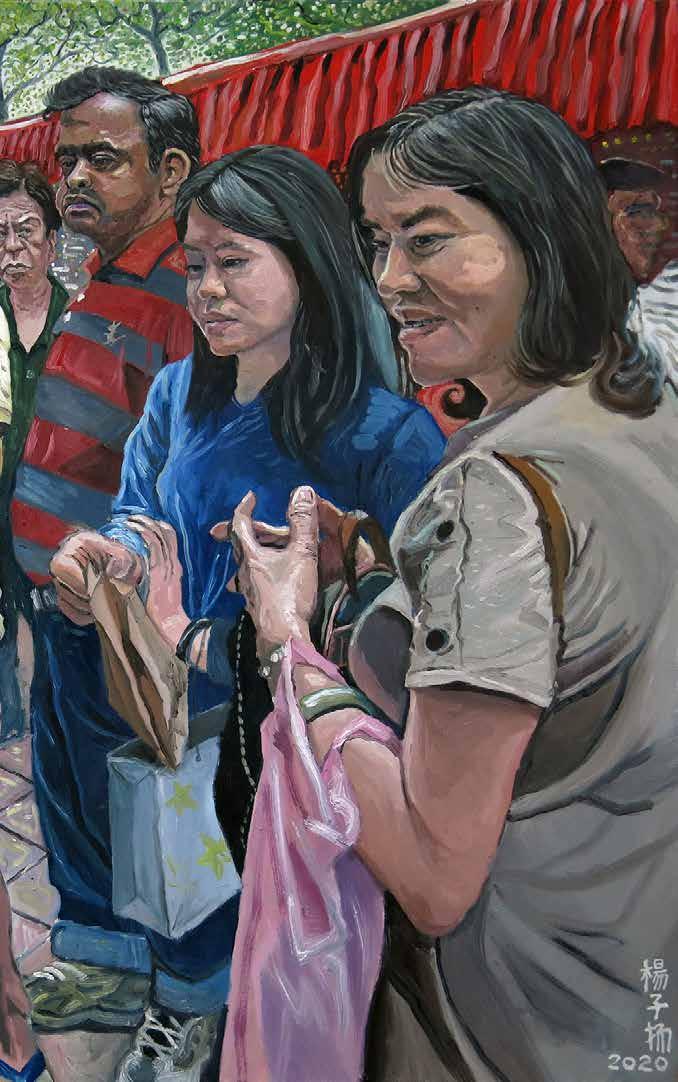

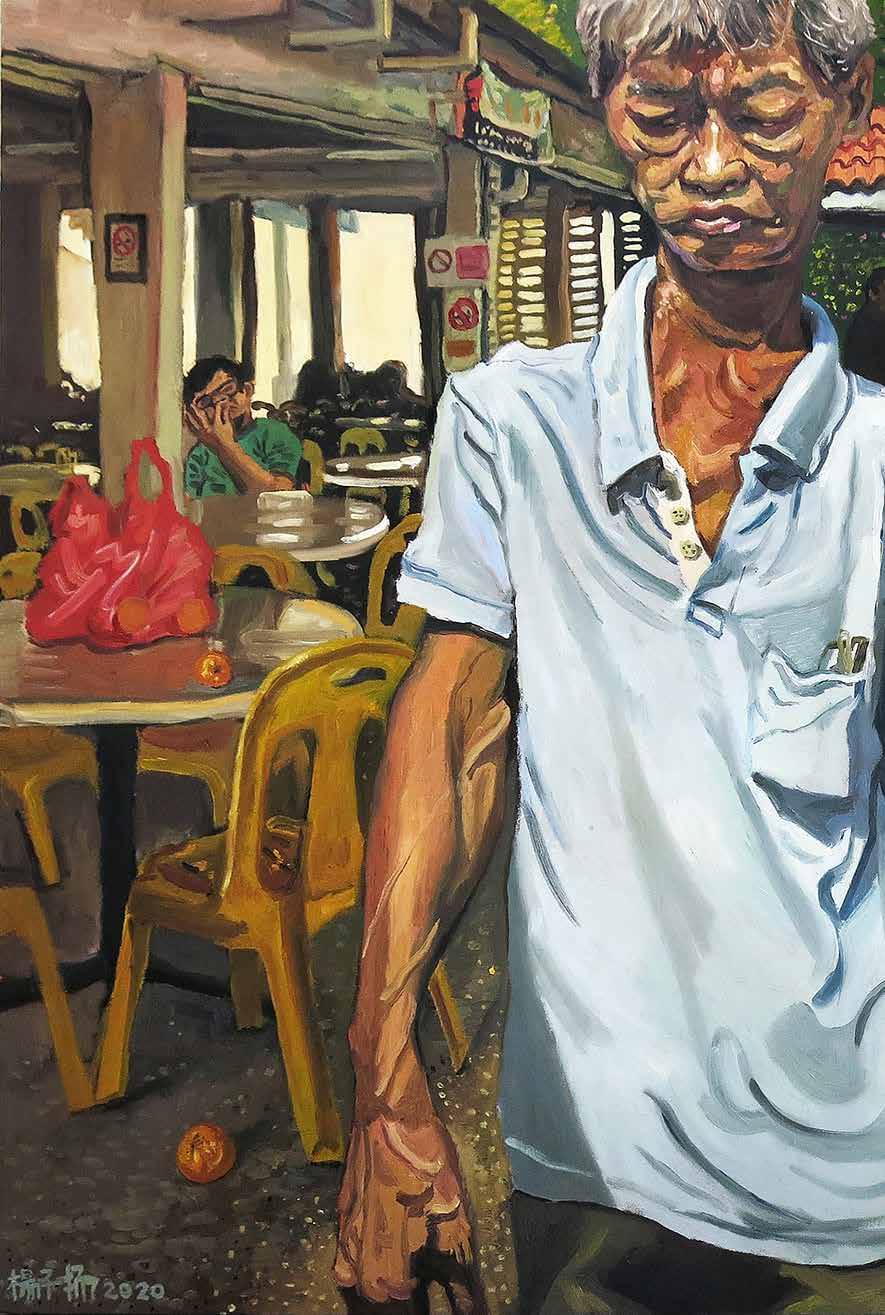

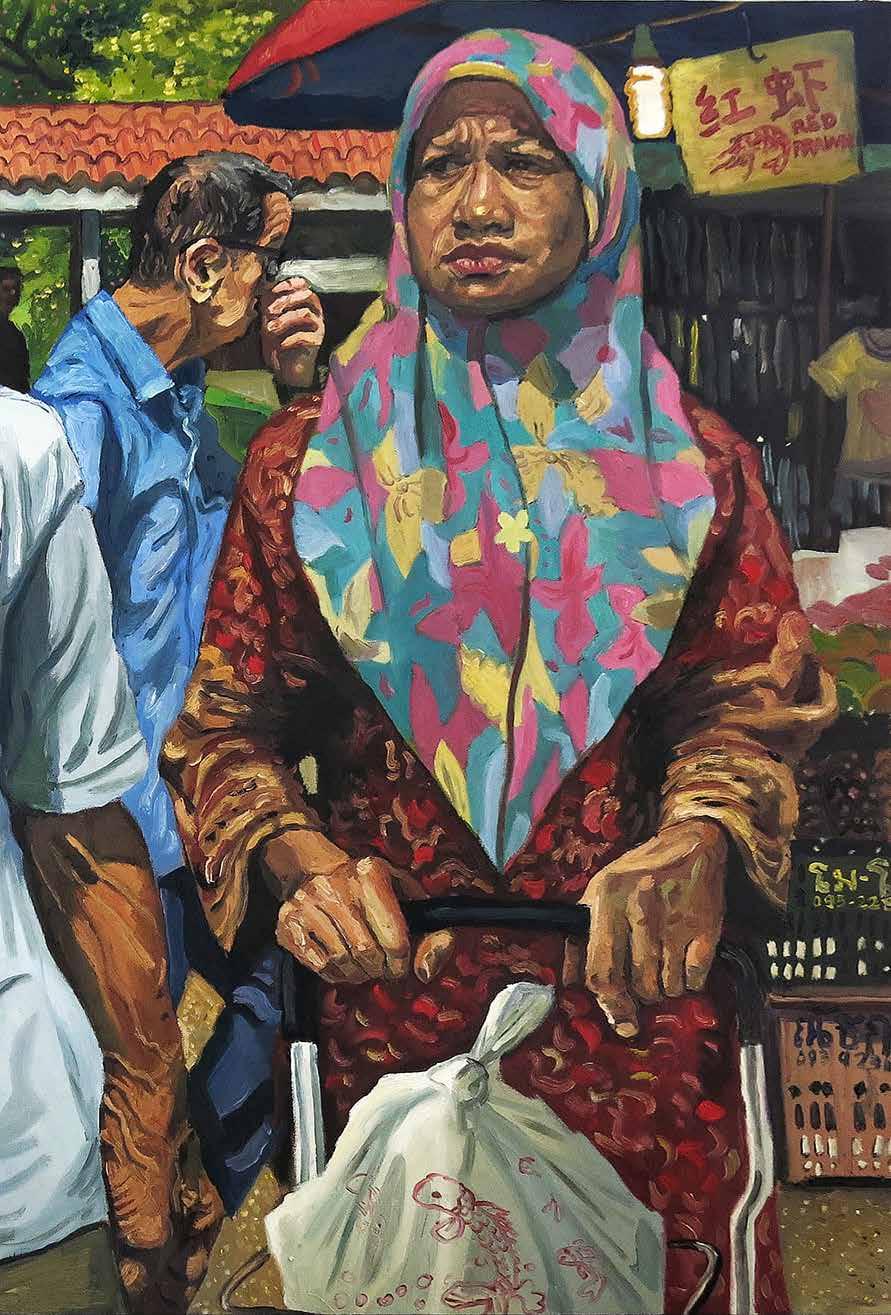

Yeo Tze Yang

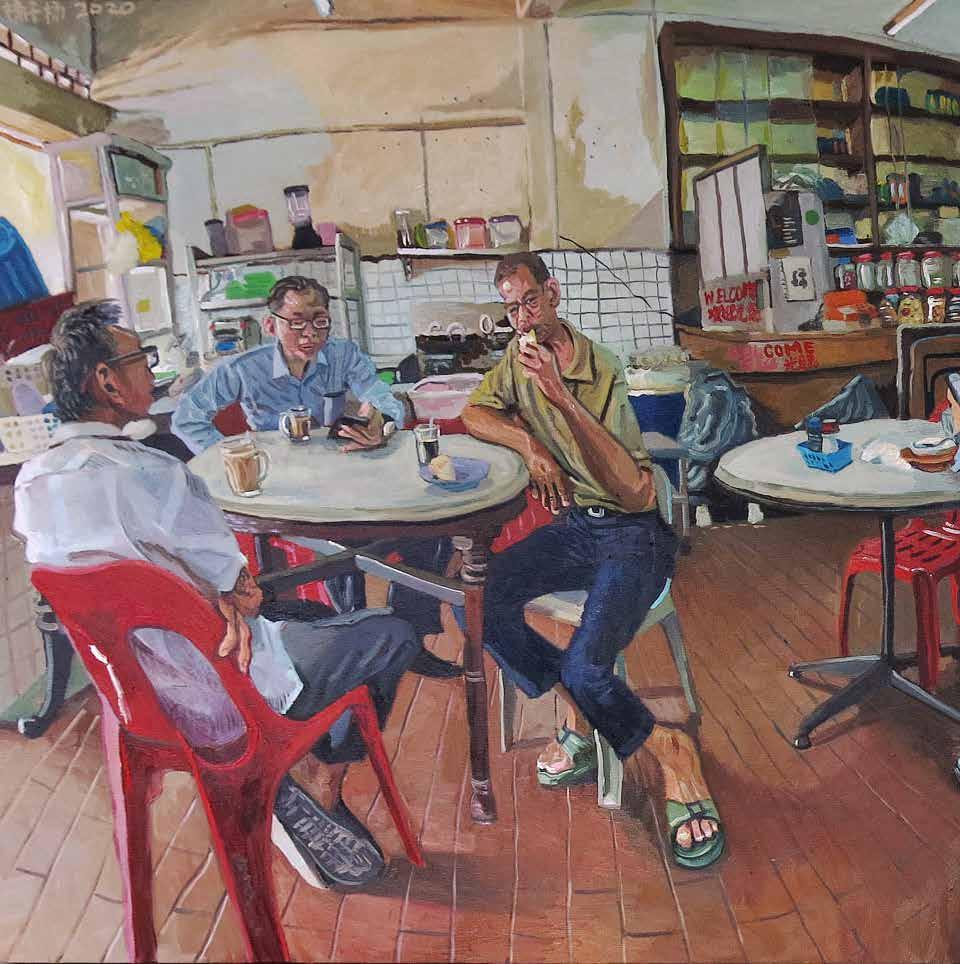

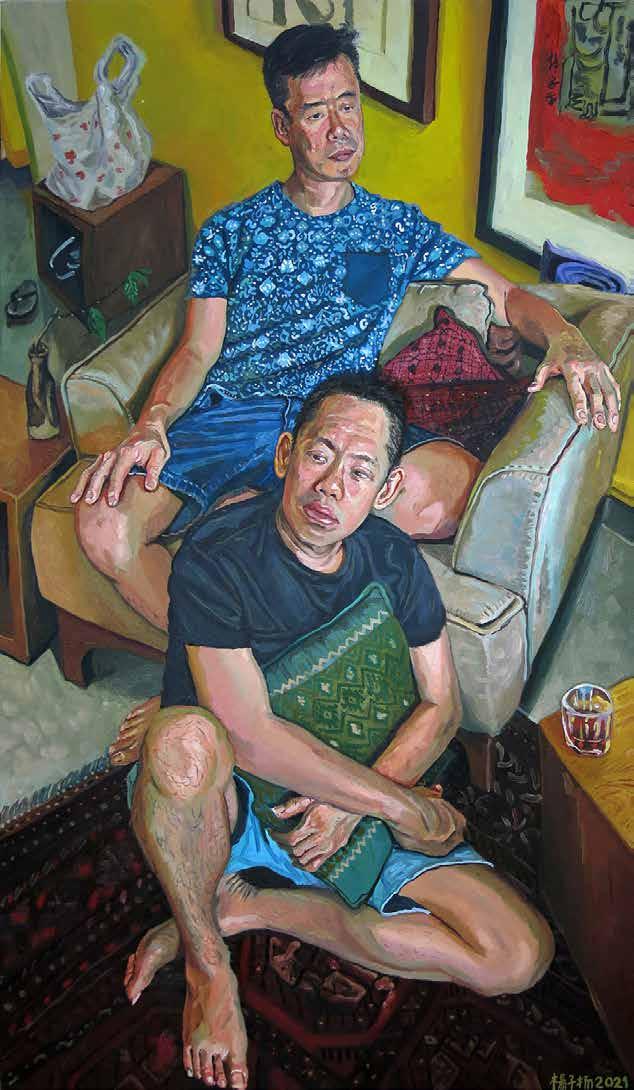

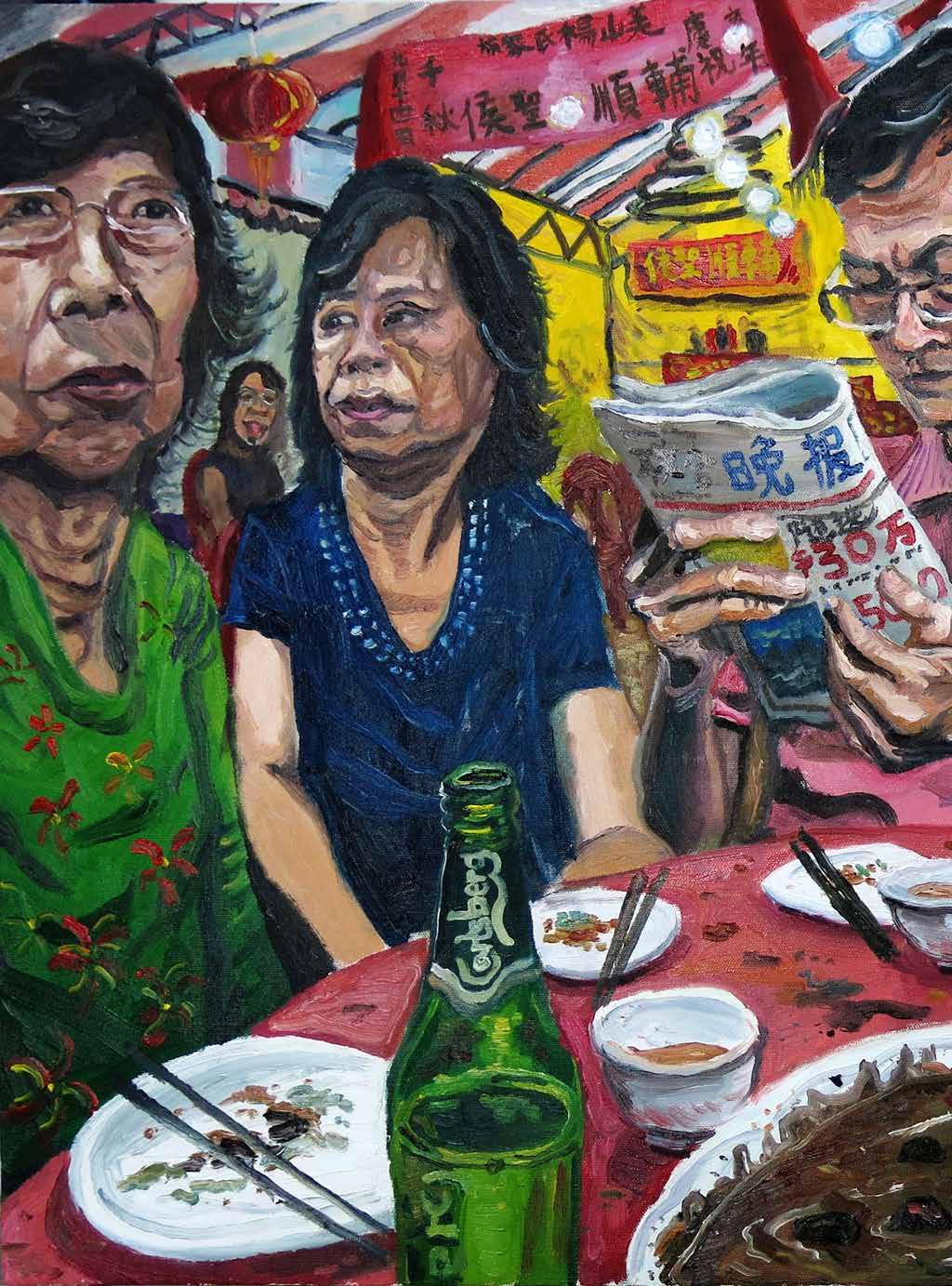

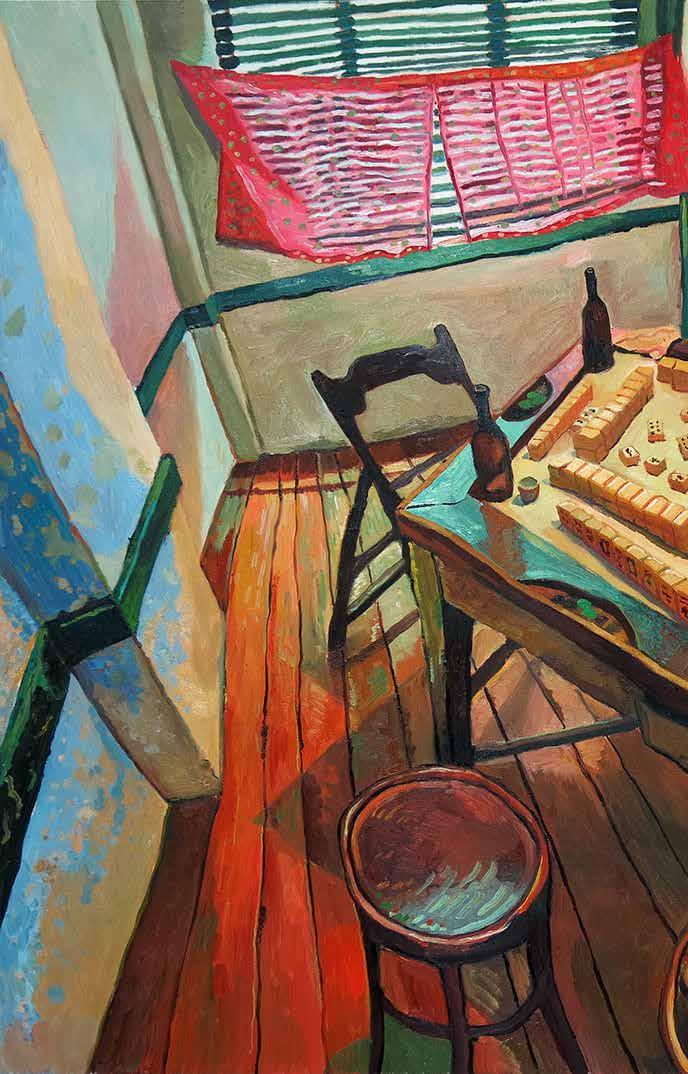

Kopitiam (Heap Seng Leong)

Yeo Tze Yang (born 1994, Singapore) is a visual artist with a primary interest in painting everyday life. He has been conferred the Silver Award of UOB Painting of the Year in 2016, and held his third solo exhibition, A Lack of Significance, in 2019 at iPreciation, Singapore. A self taught painter, his paintings often depict the unnoticed and bypassed people, places and objects of his immediate surroundings. Avoiding contemporary conceptual approaches to art, he instead reverts back to a more direct and emotive approach to painting.

Having graduated from the National University of Singapore as a Southeast Asian Studies major, Yeo is deeply interested in issues pertaining to the region and the subject matter of his artworks are derived from across the region. His interest in Southeast Asian studies includes issues of race, nationalism and difference, especially in Malaysia and Singapore. Parallel to his artistic practice, Yeo is deeply interested in the intersection points between politics and the everyday lives of ordinary people.

The result of such a process is an accumulation of images, thoughts, emotions, stories and memories, that in turn become allegories of both the artist’s life and the stories that his audiences weave into his works. Yeo’s works are collected in Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States and in the UOB collection.

be silk my friend :Connecting Asia and Europe through the Silk Road

Prof. Pilar Viviente

https://about.me/pilarviviente

The Blue Lotus Magazine, an online art magazine dedicated to Asian arts and cultures, is now ten years old. I am grateful to have been invited by its director, historian and art critic Martin Bradley, to write on the occasion of the tenth anniversary. I will talk about the Silk Road that unifies East and West, bringing its people, art and culture closer.

My first visit to a silk carpet factory was in Turkey at the InSEA on Bridge 2004, 7th European Regional Congress, July 1st to 6th 2004, Istanbul & Cappadocia, Turkey, in partnership with 'Görsel Sanatlar Eğitimi Derneği'. See https:// www.insea.org/events/insea-congresses The congress theme, International Understanding Through Arts: Living on a Bridge, refers to how we will deal with and create the appropriate learning atmosphere, building bridges between East and West. Since then I have been interested in this topic, and I was back to Turkey invited to the 2nd International Art Research Symposium, 11 - 14 April 2018, Çukurova Üniversitesi, Adana, Turkey, as keynote speaker and artist for my Installation Piano Performance, https:// sanatarastirmalari.com/Yedek/2ND/mariapilar.html

On the InSEA Cappadocia trip, we visited a silk carpet factory. We got to see women craftmaking and the whole stages of production, from how silk cocoons are formed and how silk is reeled from the cocoons to make silk threads through to the entire weaving process. I’ve never seen before how silk is produced, including its tincture with natural colours. In the next room we saw some women sitting on the floor, weaving their carpet, from the early stage of carpet weaving. The explanation included the difference between wool and silk carpet weaving. Then we went to the familiar showroom where ranges of carpets were brought out for display and sale. I bought two carpets. This Cappadocia carpet factory is a cooperative located on the ancient Silk Road route and the prices are supposed to be cheaper.

The Silk Road was an ancient network of trade routes, formally established during the Han Dynasty of China, which linked the regions of the ancient world in commerce between 130 BCE-1453 CE. As the Silk Road was not a single thoroughfare from East to West, the term 'Silk Routes’ has become increasingly favoured by historians, though 'Silk Road’ is the more common and recognized name.

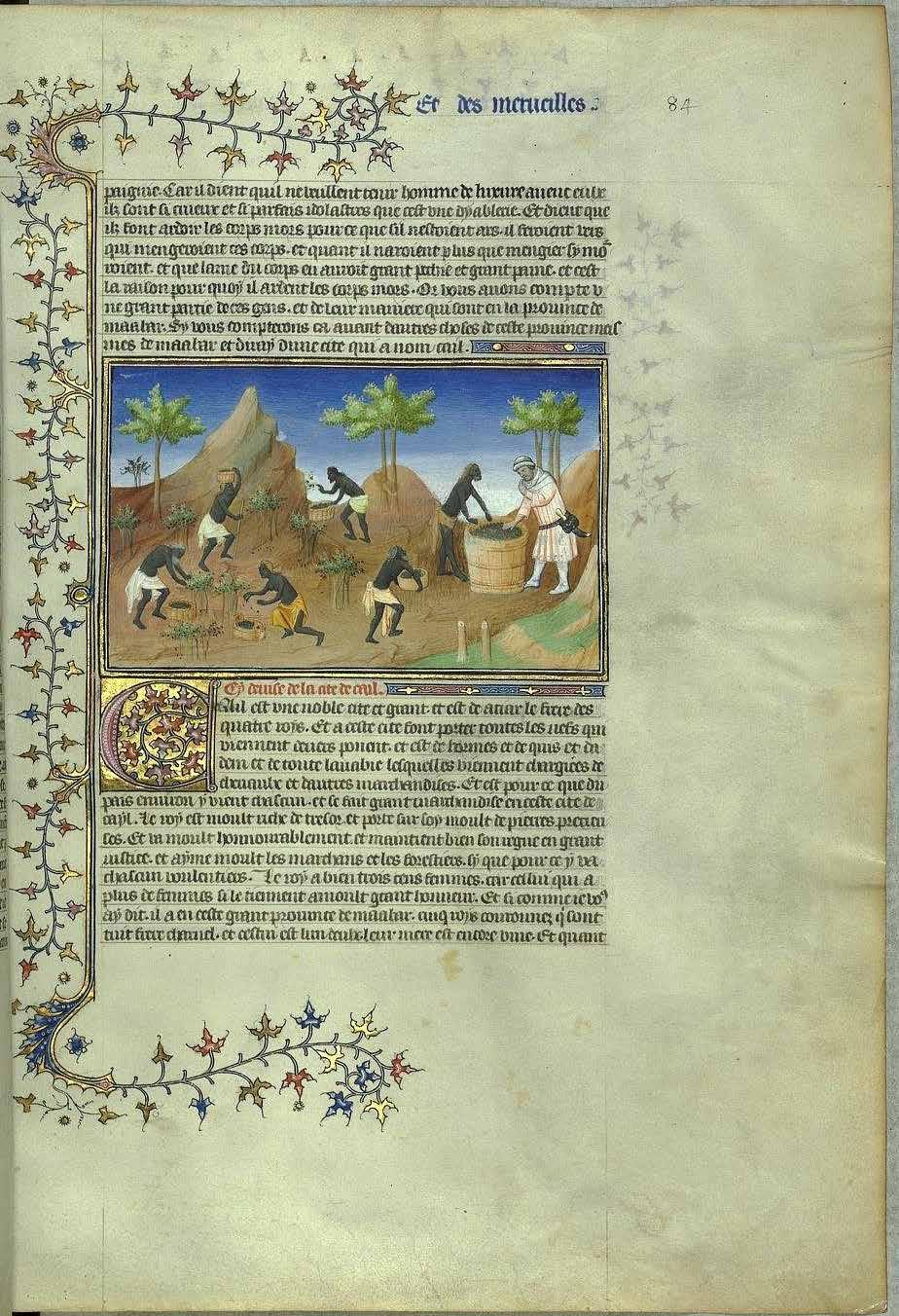

The European explorer, merchant and writer Marco Polo (1254-1324 CE) travelled on these routes and described them in depth in his famous work, “Livres des merveilles du monde” (Book of the world’s marvels), published around the year 1300. In English, this book is also known as The Travels of Marco Polo. It describes – among other things – Polo’s travels along the Silk Road and the various Asian regions and cities that he traverses, including China. Polo, and later von Richthofen, make mention of the goods which were transported back and forth on the Silk Road.

The real interest of this historic commercial route lies not only in the exchange of goods, but most of all in the first great peaceful contact between civilizations. The connection between religions, art, culture and knowledge led to great enrichment for the first time at the global level.

21st C Silk Road

One Belt One Road (OBOR), the brainchild of Chinese President Xi Jinping, is an ambitious project that focuses on improving connectivity and cooperation among multiple countries spread across the continents of Asia, Africa and

Europe. Dubbed as the 'Project of the Century' by the Chinese authorities, OBOR spans about 78 countries. Initially announced in the year 2013 with a purpose of restoring the ancient Silk Route that connected Asia and Europe, the project's scope has been expanded over the years to include new territories and development initiatives.

Also called the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the project involves building a big network of roadways, railways, maritime ports, power grids, oil and gas pipelines and associated infrastructure projects. The project covers two parts. First is called the 'Silk Road Economic Belt’, which is primarily land-based and is expected to connect China with Central Asia, Eastern Europe and Western Europe. The second is called the '21st Century Maritime Silk Road' which is seabased and is expected to link China’s southern coast to the Mediterranean, Africa, South-East Asia and Central Asia.

Spain plays a role in the New Silk Road. On November 20, 2018, the University Institute of European Studies presented the book 'The role of Spain in the New Silk Road' at the University CEU San Pablo, Madrid. The book analyses the role that Spain can have in the New Silk Road. It includes economic, commercial, historical, political and strategic perspectives that allow the reader to understand in depth the opportunities and challenges that this route may entail. It also provides practical recommendations that can be useful for politicians and companies. This work is part of a larger project called 'Spain and the New Silk Road: opportunities, challenges, recommendations', developed by the University Institute of European Studies of the CEU San Pablo University, Madrid, with the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, and which has had the collaboration of experts, academics and businessmen.

International Network of UNESCO Silk Road Online Platform

UNESCO has launched a new Silk Road project. According to UNESCO website, "In order to ensure the full participation of various partners in Member States in the project, an International Network of focal points was established for the UNESCO Silk Road Online Platform. Major countries along the historical Silk Roads and beyond have designated Focal Points to participate actively in and to follow up on the project’s activities. The Focal Points are in charge of: - To collect, analysis and transmit information and data on the Silk Roads heritage and activities in their respective countries to be integrated in the UNESCO Silk Roads Online Platform; - To inform national stakeholders about the activities related to Silk Roads undertaken by UNESCO and its partners; - To encourage and advise national authorities and stakeholders in initiating, implementing and promoting activities related to Silk Roads; - To exchange experience and expertise with other members of the Network and facilitate cooperation and partnership; - To contribute to the promotion of mutual understanding, inter-cultural dialogue, reconciliation and cooperation among nations and people sharing the Silk Roads common heritage". From https://en.unesco.org/ silkroad/international-network-silk-roadonline-platform

International Focal Points have representatives in Afghanistan, China, Egypt, Georgia, India, Iraq, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Oman, Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, Spain, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.

According to UNESCO website: "The Fourth Meeting of the UNESCO Silk Roads Online Platform International Network was held in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, from 28 - 31 October 2018. Approximately twenty Focal Points from participating Member States attended, representing their respective countries, along with academics and experts. They exchanged experiences and good practices in promoting and implementing activities related to the Silk Roads. The main objective of this meeting was to discuss the implementation of the 2016-2018 Action Plan of the International Network that was adopted during the second meeting of the Network in Valencia in June 2016, and to define

the 2019-2020 Action Plan."

The event took place in conjunction with a few activities highlighted continued dialogue as well as the initiatives implemented to overcome challenges in various contexts. For instance, the “Exhibition of Chinese Silk, Porcelain and Tea", which was officially inaugurated with the People’s Republic of China serving as the Guest of Honour. Also mention the opening of the “Youth Eyes on the Silk Roads Photo Contest” travelling photo exhibition on October 28, 2020. The Award Ceremony of the "Youth Eyes on the Silk Roads Photo Contest 2018" took place in Beijing, China, on the occasion of International Peace Day (September 21), and in partnership with the China World Peace Foundation. Gallery of Winners is available at the UNESCO website: https://unescosilkroadphotocontest.org/en/ node/6627

Besides, a Public Conference entitled, "Contributions of the Maritime Silk Roads to the Development of a Shared Cultural Heritage”, also took place on 30 October 2020.

According to UNESCO website: "In addition to its dynamic location, Muscat served as a symbolic bridge between North and South, East and West. Its history as a crossroads of people and cultures from Europe and Islam continues to serves as a reminder of the two civilizations’ shared values and the path that has been forged towards peace."

Here to see the "Top 10 Silk Road Cultural Events Released during the 2020 Silk Road Week": https://www.chinasilkmuseum.com/ info_180.aspx?itemid=27899

Silk Museums International Conference Valencia 2018

Focal Point UNESCO Silk Road Program has included Valencia. Valencia has been named, 'City of Silk 2016-2020', corresponding to its position as a UNESCO Silk Roads Online Platform Focal Point.

The Silk Museum of Valencia has organized the Silk Museums International Conference (Congreso internacional de museos de la seda) in Valencia, Spain, from 15 - 17 November 2018, with the support of the Agència Valenciana del Turisme, and in collaboration with the UNESCO Silk Roads Online Platform that has a link at its website: https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/ events-festivals/silk-museums-internationalconference-valencia-spain

It is the first time that an initiative of this nature has been undertaken. International experts representing the most renowned Silk Museums have participated, including Mr. José Maria Chiquillo Barber (Spain), President of the UNESCO Silk Roads Online Platform International Network. Mr. Chiquillo Barber became the Focal Point of Spain for the International Network of the UNESCO Silk Roads Online Platform in April 2015, and was elected to be its President shortly thereafter. In October 2018, he was re-elected President for the period 2018-2020. Here for an interview in 2020: https://247valencia.com/the-silk-roadunesco-exclusive-interview-with-internationalpresident-jose-maria-chiquillo-barber/

Prestigious cultural institutions such as UNESCO Silk Roads Online Platform, International Council of Museums (ICOM) or the International Society of Education through Art (InSEA) supported this conference. These are the Collaborating Institutions: UNESCO Silk Roads Online Platform; Silk Museums International Conference; Universitat de València; ICOM International Council of Museums (UNESCO); InSEA International Society of Education through Art; AVALEM Associació Valenciana d’Educadors de Museus; CREARI Grup d’Investigació en Pedagogies Culturals (GIUV 2013-103).

The goal of the conference is to educate, as well as to compare, the history and characteristics of international Silk Museums from a trans disciplinary perspective. According to the Silk Museum of Valencia, Spain: "The Silk Museum of Valencia organizes this International Conference with the support of 'Agència Valenciana del Turisme' (Valencian Tourism Agency) for knowing and comparing the history and the characteristics of the Silk Museums in the world from a trans disciplinary perspective: costumes and technological-scientific museums mainly". And "The ultimate goal of the event is to create

an International Network of Silk Museums in order to build common long-term projects and exchange experiences".

Conference Convenors are Dr. Germán Navarro Espinach -Coordinator of the scientific committee of the Museum of the College of the Greater Art of the Silk of Valencia, professor of Medieval History of the University of Zaragoza, and Dr. Ricard Huerta -Member of the scientific committee of the Museum of the Art College of the Silk of Valencia, artist and professor of Artistic Education at the University of Valencia and president of AVALEM Associació Valenciana d'Educadors de Museus. Conference took place at the MUVIM Museu Valencià de la Il·lustració i la Modernitat.

Professor Germán Navarro Espinach highlighted the multicultural aspect of silk in his lecture at the Silk Museums International Conference in Valencia, Spain: "Silk is a multicultural vehicle since it has been in the hands of different religions and cultures". Therefore, we can say that silk is essentially a symbol of cultural and religious diversity, as I said in my previous article published a month after this congress: Viviente, P. (2018, December). Spain and Valencia On the Silk Road. Socialist Factor, 32-35.

A large book on this International Congress with Exhibition and Conference Cycle has recently been published. See: MUSEOS DE LA SEDA / SILK MUSEUMS. Germán Navarro Espinach & Ricard Huerta (coords.), https:// www.museodelasedavalencia.com/visor/ museos-de-la-seda/

If you ever travel to Spain I recommend visiting the Silk Museum of Valencia. Website available here: https://www.museodelasedavalencia. com/en/

China National Silk Museum events to celebrate ancient Silk Road 2020

China National Silk Museum hosted events to celebrate the ancient Silk Road. With the support of UNESCO, the China National Silk Museum launched the Digital Archive of the Silk Roads Project on june 2020 with a webinar held to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the UNESCO Silk Roads Programme. The silk museum in Hangzhou, east China's Zhejiang Province, also hosted a special exhibition titled "The Silk Roads: Before and After Richthofen". It showcases precious national treasures excavated along the ancient Silk Road, telling stories about the cultural exchanges between China and countries along the ancient Silk Road. “2020 Silk Road Week” was the first edition of this annual event, and was hosted by the National Cultural Heritage Administration and the People’s Government of Zhejiang, with the theme of “The Silk Roads: Mutual Learning for future Collaborations” in Hangzhou, China. The event featured museum led activities such as exhibitions, performances, reports, and seminars, celebrating the anniversary of the successful inscription, in June 2014, of the Silk Road – from Chang’an to the Tianshan Corridor, onto UNESCO’s list of World Heritage. See "2020 Silk Road Week" website: https://es.unesco. org/silkroad/node/11075 "The history of the Silk Road tells us that the Silk Road is spontaneous and common knowledge for humanity. The East and the West also communicate with each other through it", said Zhao Feng, curator of the China National Silk Museum. Also, he says "What we are doing now, especially building the Belt and Road, has a clear historic and cultural background." It has, indeed. We remember now the first paragraphs of this article.

The New Silk Road has created a conjunction of favourable political, economic and cultural circumstances, even in 2020, despite the negative impact of Covid-19 Coronavirus on the Belt And Road Initiative (BRI). Now that the exchanges between China and the countries along the Belt and Road of both people and goods has been dealt a blow, it is more relevant than ever to provide cultural and educational activities aimed at the development of the Belt and Road Initiative, building bridges between East and West.

2021 Silk Roads Youth Research Grant

Recently, the Silk Roads Program has launched the call for proposals for the ‘Silk Roads Youth

Research Grant’. This new initiative aims to mobilize young researchers for further study related to the shared heritage of the Silk Roads, as well as its potential in contemporary societies for creativity, inter-cultural dialogue, social cohesion, regional and international cooperation, and ultimately sustainable peace and development. It is addressed to young researchers whose work focuses on the Silk Roads, passionate about the shared heritages and cultural interactions along these historic trade routes. The call for the 2021 Silk Roads Youth Research Grant awards 12 grants to research that furthers our understanding of the mutual influences, rich cultural exchange, and interactions facilitated by the Silk Roads. See UNESCO calls for proposals for the 2021 Silk Roads Youth Research Grant: https://on.unesco. org/2Y2BMJQ#UNESCOSilkRoads

It is this unique history of mutual exchange and dialogue that the Silk Road Online Platform seeks to promote, in line with the 2013-2022 International Decade for the Rapprochement of Cultures and as part of UNESCO’s commitment to creating a culture of peace. In the words of UNESCO’s Director General, Irina Bokova, “promoting cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue is a most powerful way to build bridges and lay the ground for peace”.

Because silk is essentially a symbol of cultural and religious diversity it represents understanding and communication between people, cultures and countries. Therefore, it promotes reciprocal influences rather than polarities, cooperation rather than hostility, actively enhances inclusion and interculturality, and helps us overcome the fear of the unknown, the other. be silk my friend!

Meat Soup at Master Suki Soup Siem Reap is the Cambodian jumping off spot for the ancient Kingdom of Angkor, and its Wats. That old city is under siege. Not, as usual, by multi ethnicities of tourists Tuk Tuking their hot and sweaty way under the punishing sun, but by the current Covid 19 pandemic.

Like towns and cities across the world, Siem Reap has seen a drastic falling off of tourism. Shops have been hard hit, foot nibbling fish remain hungry, all kinds of eateries and the more up market tourist oriented restaurants are endangered more than others.

Shutters remain down for many foreign owned restaurants, waiting out the crisis, while others, offering unique dining experiences such as one, offering craft rum making, have closed forever. In the main, it is those eateries catering to Khmer tastes, or those which are thoroughly embedded in the expatriate lifestyle, which remain.

Breakfast Beef Soup with baguette at Urban Tree Hut

Local Khmers like to take French baguettes, Thai, Vietnamese or the local version of noodle soup for breakfast, and sometimes those crusty baguettes accompany the soups. Those eateries thrive in these mask wearing, one metre distant, times out of mass demand. This is borne out by the large number of small engined motorcycles parked outside. Breakfast noodles may come with pigs blood, pig’s liver, intestines, duck, chicken, diced pork or even chunks of boiled beef to add body to the thin soup, the variety of noodles on offer, and the various indigenous vegetables tumbled in with caramelised garlic and chives as garnish. Khmer noodle soups vary from ‘Khoy Teil, to Keive Teave and the interesting Hu Tieu Nam Vong.

Beef Soup at Family Rice Noodle & Chives cake

Pork Innards Soup at Mikeav

On the Wat Bo side of the Siem Reap river, Mikeav is very popular early in the morning. Just look for the plethora of motorcycles and Scoopy scooters. There again, the Family Rice Noodle and Chives Cake eatery has an added bonus of selling Chinese style bamboo steamed Dim Sum, as well as soups, fried noodles and the street fare known as ‘Chives Cake’ or ‘Num Kachay’, which basically chives pan fried inside a ‘cake’ of rice flour. Originally derived from the Chinese turnip cakes..

Down Siem Reap side streets you might see baskets of small fish, either whole or filleted, drying in the sun for family use.

Elsewhere there still is the occasional hawker stall, though many have packed up and gone. Opposite is one stalwart woman making something of a living by grilling baby bananas (Chek) kebab style with a wooden skewer, grilling chives cakes and sweet corn hobs.

Behind her is the ubiquitous drink stand. A must in the baking heat of Cambodia which, as I write, sores to 37°C.

Hai Nan Chicken at Wisely Coffee & Bakery

I had been frequenting Wisely Coffee and Bakery for some weeks before I discovered they had yet another menu. ‘Hai Nam Chicken’ was on this new menu. Elsewhere this dish is known as ‘Hainanese Chicken Rice’. I had to give it a try. It had been one of my all time favourites when I was living in Malaysia. It’s a simple sounding dish, but it takes a lot of preparation. It’s not impossible to make it at home, but time consuming. Elsewhere the dish is presented separately, normally with breast chicken cut into slices and laid on top of the rice. At Wisely’s (above) the chicken is drumstick and there are extras, such as the cut hard-boiled egg and the Choy Sum. Though different from what I had been used to, I found this dish to be excellent. There’s a question mark as to it’s origin. The exact dish as it exists in Malaysia and Singapore does not exist in Hainan, China. Both Malaysia and Singapore claim that their Chinese immigrants originated the dish.

Also of Chinese origin in Siem Reap are the ‘Egg Tarts’ from the obviously named ‘Egg Tart Factory. I had first had ‘Chinese Egg Tarts’ in Chinatown, London. And they were nice, but it wasn’t until I journeyed to Macau that the fullness, and the richness of what are sometimes called ‘Portuguese Egg Tarts’ hit me.

Originally from Portugal, where they are known as ‘pasteis de nata’, the tarts found their way to Macau and then into Hong Kong and across the world. I was surprised to find these in Siem Reap. Although not as rich as the Macau variety, these tarts from the Egg Tart Factory were far superior to those of London’s Chinatown.

Egg tarts from the Egg Tart Factory Siem Reap

Kamon Japanese Dining and Cafe is at the top of Hup Guan Street, in the area aimed to be up and coming - Kandal market, Siem Reap, and is opposite Mammashop the Italian Restaurant. Due to the pandemic, Kandal Market area is somewhat of a ghost town, with those places which remain open, are only open on limited days. Kamon is open Tuesday to Saturday, closed Sunday and Monday.

When my friend of fifty-five years arrived in Malaysia, we took a rail trip to Ipoh, towards the north of the country. My friend had spent many years in Japan and was addicted to Katsu Curry. Nearby our Ipoh hotel was a small mall. Inside that mall, yes you guessed it, was a Japanese restaurant. My friend insisted that I try the Katsu Curry. Having had curries from various places in India, from Thailand and from Malaysia, I was a tad apprehensive but tried nevertheless. It was not to my taste.

When Kamon, which is managed by the Japanese chef, opened last year beside Le Water Villa (previously the Kandal Village Inn), and in what had been The ArtCoffee, it was is a breath of Japanese air had wafted through the dusty Cambodian Hup Guan Street.

When faced with the menu I remembered my old friend, the Japanese restaurant in Ipoh, and ordered the Chicken Katsu Curry. I held my breath. I was presented with something bearing only a slight resemblance to the meal I had previously. This one was easy on the eye, and pleasurable on the palate. I was hooked and have been back a few times since over this year of my Siem Reap sojourn.

Japanese Chicken Katsu Curry at Kamon Japanese Dining and Cafe

Some issues ago I had written about Eggs Benedict and where to find this light dish in and around the city centre of Siem Reap. At that time Common Grounds Cafe at Mondul 1 Village, and the opposite end of Hup Guan Street from Kamon, were not serving Eggs Benedict. But now they are. Along with the air conditioning, the very friendly staff and the free ice cool water Eggs Benedict is now on their menu. And it tastes great.

The New Zealand owned Jungle Burger Sports Bar & Bistro, is not in the jungle and nor is it just a burger bar. Jungle burger has become famous for its authentic New Zealand meat pies too. That is not to mention some of the best fish and chips (Fush & Chups) in town, and one of the heartiest, if not healthiest all day Full English Breakfasts in town. This start to the day challenge consists of 2 sausages, 2 slices of back bacon, a couple of rounds of black pudding, 2 eggs, beans, tomatoes, mushrooms and 2 rounds of toast with butter. I’ve not seen anything so beautiful since I was in Dublin, marvelling at the Full Irish Breakfast, which resembles the English, but has added white sausage too.

The opposite image is of the ‘Anzac Classic Mince & Onion ’ in other words a New Zealand pie, which appears with mushy peas, a superb gravy and mashed potatoes almost as good as my own. Now that is high praise indeed.

Jungle Burger Sports Bar & Bistro has earned its high praise and has become a stalwart of Siem Reap.

Anzac Classic Mince & Onion at Jungle Burger

Craft Rum at Georges Rhumerie - French Restaurant Georges Rhumerie, French Restaurant Siem Reap has closed. The lack of tourism has killed one of the best higher end restaurants in Siem Reap. Not only was it becoming famed for its cuisine (French Creole mixed with adventures in Cambodian cooking) but also for its craft rum.

The exotic ingredients used for Georges’ craft rum has made it a go to liquor for many families, and even me and I never like rum until I tasted those from this greatly missed gourmet haven.

Last but certainly not least comes dessert. Siem Reap’s very own Gelato and Coffee Lab has led the way in gelato (frozen dessert of Italian origin, generally made with a base of 3.25% milk and sugar) and sorbet, sourcing local, made fresh daily with all natural ingredients.

Coffee, imported from Thailand and Sumatra, is custom-blended and brewed by trained baristas. There is also a variety of coffee cocktails to blend with some of the best coffee Siem reap has to offer.

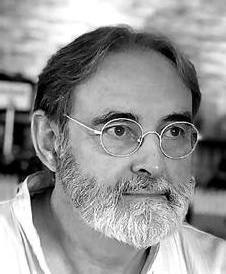

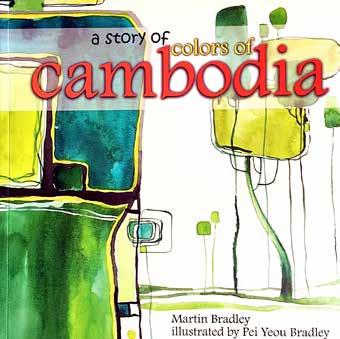

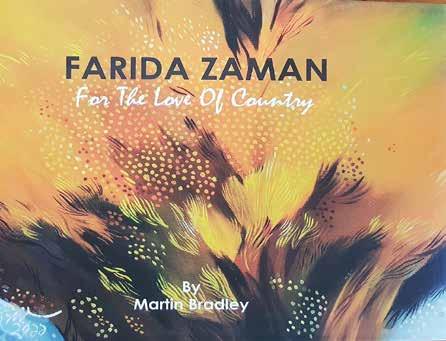

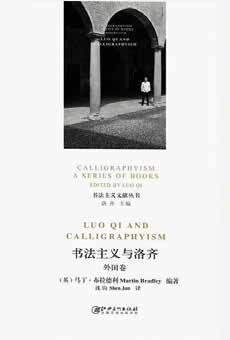

martin bradley

Martin Bradley is the author of a collection of poetry - Remembering Whiteness and Other Poems (2012) Bougainvillea Press; a charity travelogue - A Story of Colors of Cambodia, which he also designed (2012) EverDay and Educare; a collection of his writings for various magazines called Buffalo and Breadfruit (2012) Monsoon Books; an art book for the Philippine artist Toro, called Uniquely Toro (2013), which he also designed, also has written a history of pharmacy for Malaysia, The Journey and Beyond (2014). Martin wrote a book about Modern Chinese Art with Chinese artist Luo Qi, Luo Qi and Calligraphyism from the China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China, and has had his book about Bangladesh artist Farida Zaman For the Love of Country published in Dhaka in December 2019.

He is the founder-editor of The Blue Lotus formerly Dusun an e-magazine dedicated to Asian art and writing, founded in 2011.

singapore 2012 malaysia 2012

bangladesh 2019 china 2017

philippines 2013 malaysia 2014

THE BLUE LOTUS CHAP BOOKS 2011 - 2021

THE BLUE LOTUS CHAP BOOKS 2011 - 2021