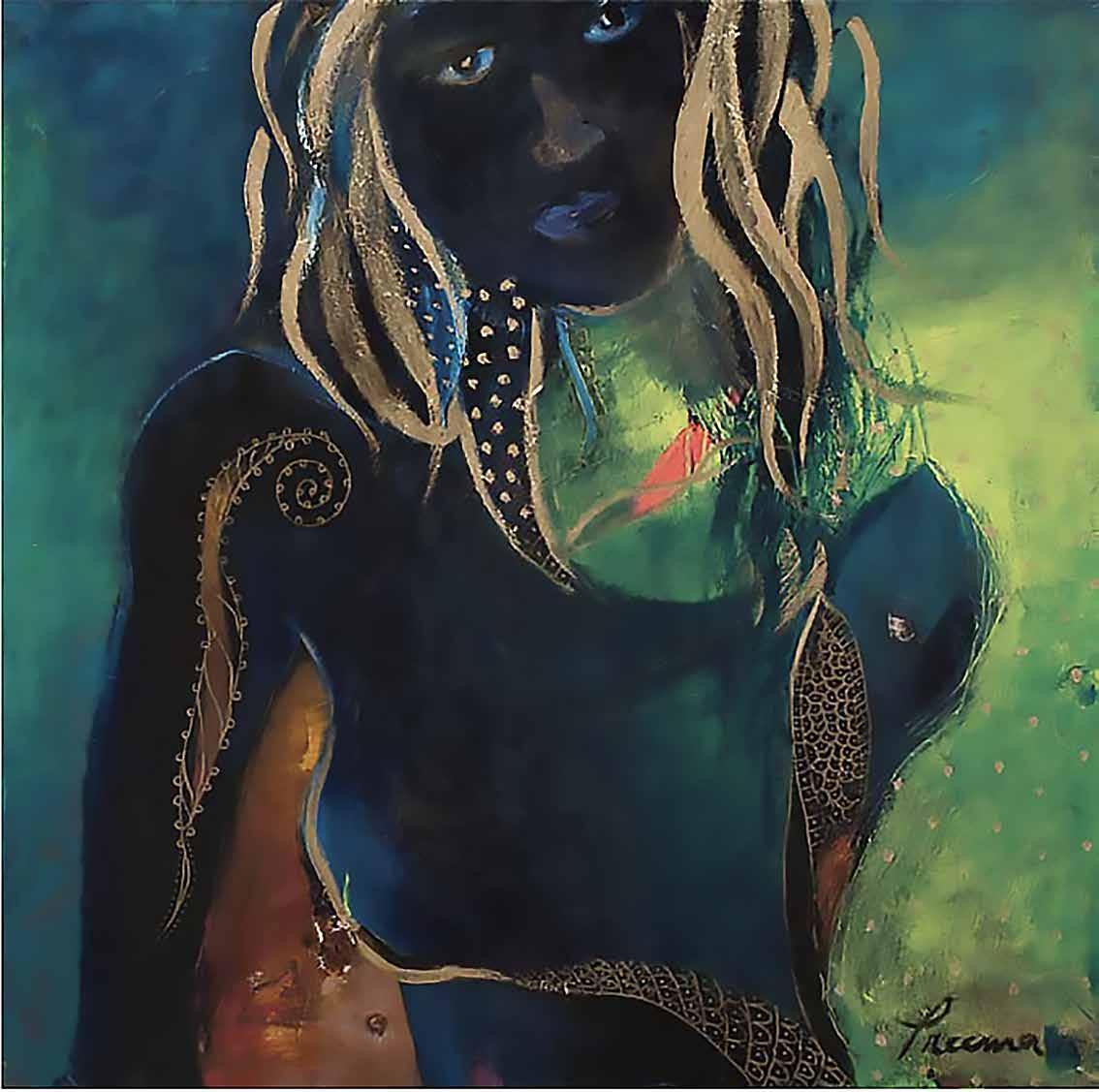

Preema Nazia Andaleeb

Rafiee Ghani

Rebecca Hague

Rajib Sikar

Stefano Morrone

Firdous Ismail

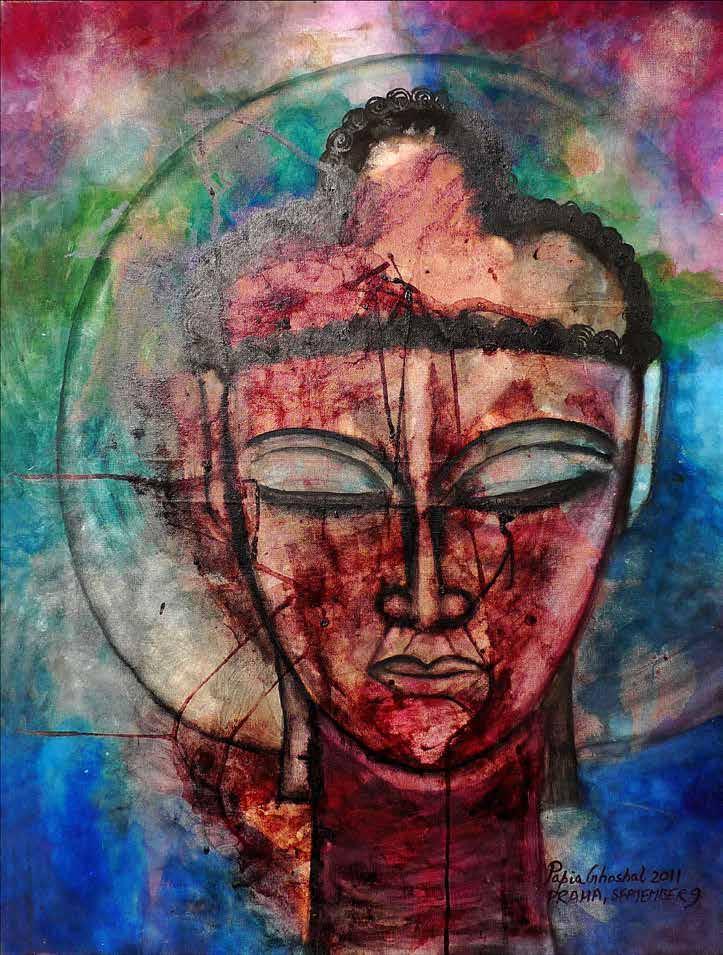

Papia Ghoshal

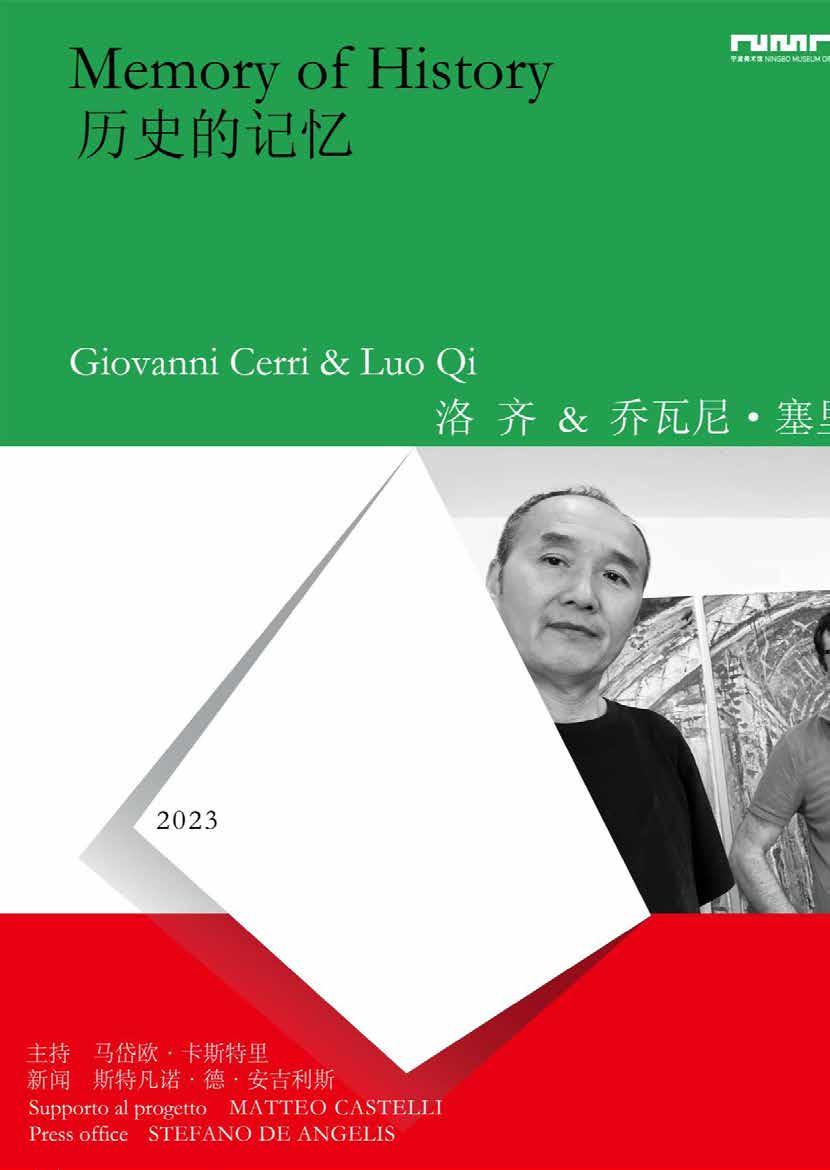

Luo Qi

Giovanni Cerri

Arjun Das

Rafael Serrano

Selima Quader Chowdhury

Preema Nazia Andaleeb

Rafiee Ghani

Rebecca Hague

Rajib Sikar

Stefano Morrone

Firdous Ismail

Papia Ghoshal

Luo Qi

Giovanni Cerri

Arjun Das

Rafael Serrano

Selima Quader Chowdhury

Image © by Martin Bradley

Image © by Martin Bradley

p32

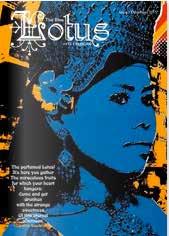

A quick word Editor’s comments

Preema Donna not a book review

Preema Nazia Andaleeb Bangladesh

Bumi Bertuah

Rafiee Ghani exhibition Malaysia

Mourning the Martyred Intellectuals

Rebecca Hague Bangladesh

p36

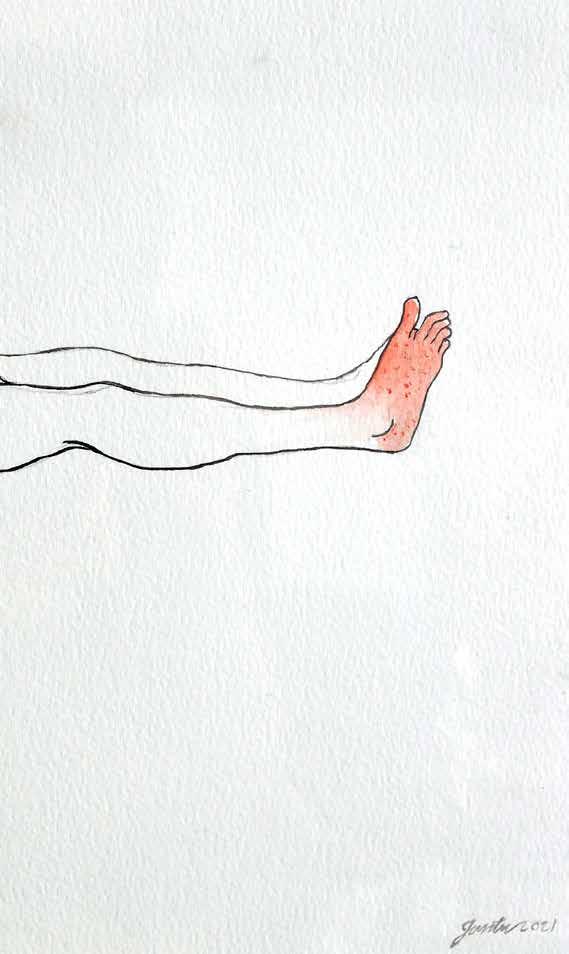

‘Hunger’ (Bhukh)

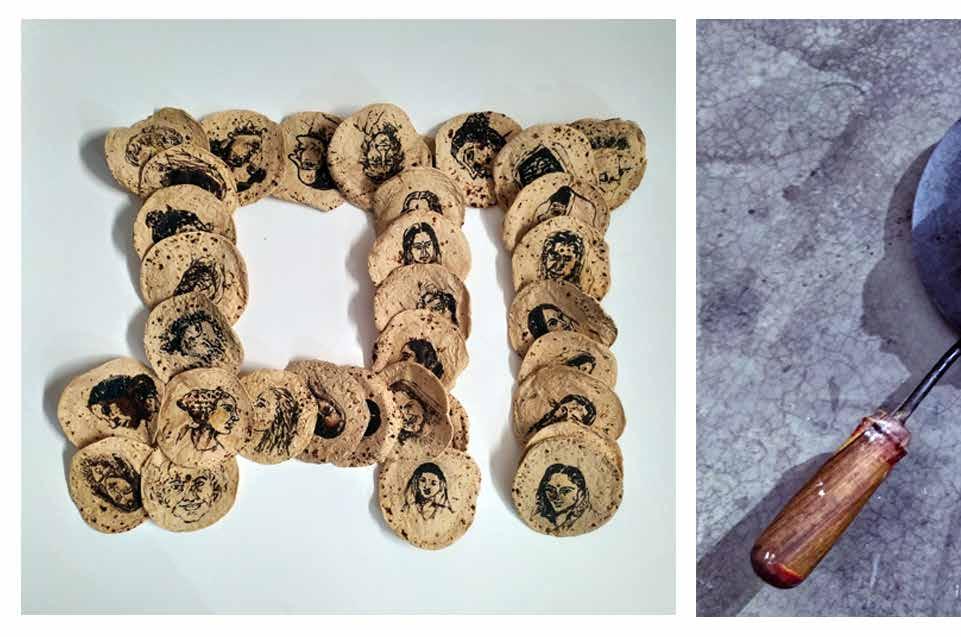

Rajib Sikar India

p48

Water Tales Cambodia

Stefano Morrone with SafeSpace BTB

p62

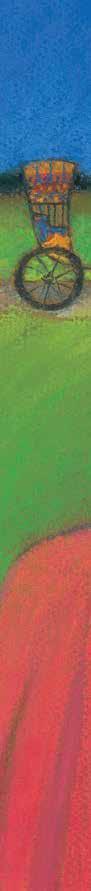

Rickshaw Girl

Film review India

p74

Astaka

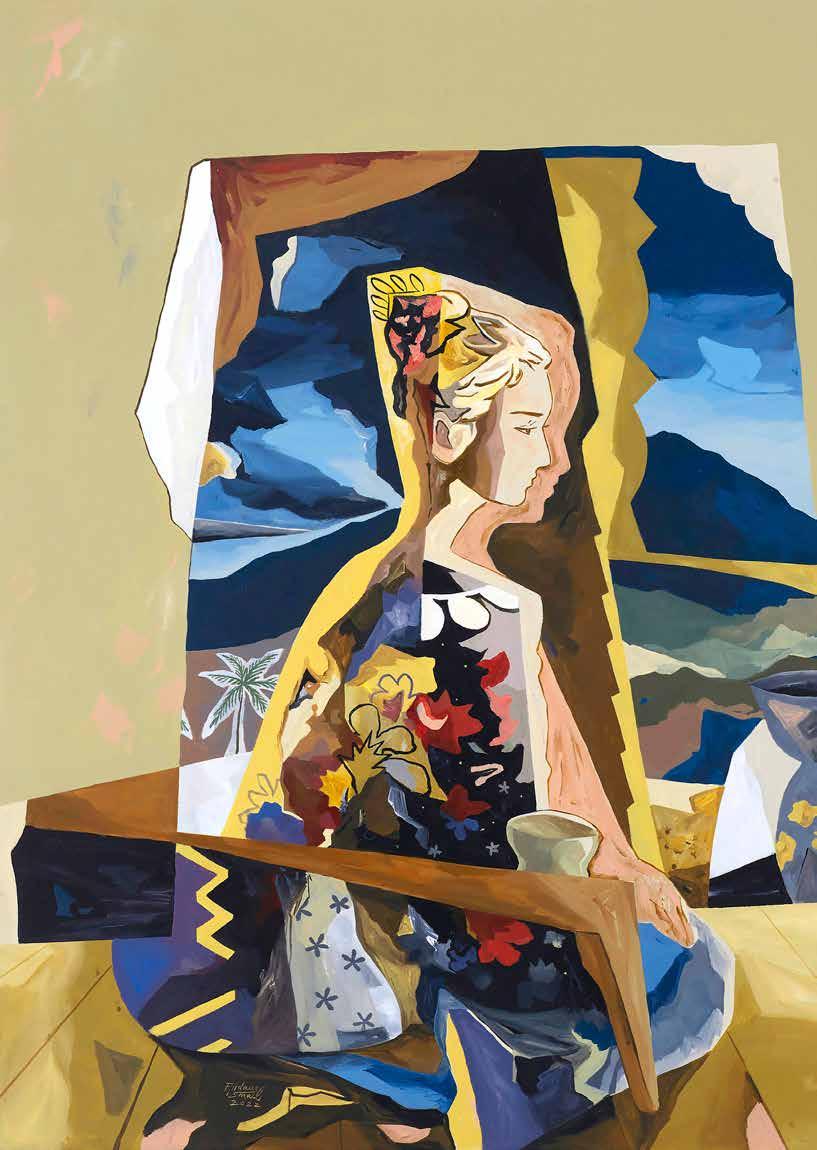

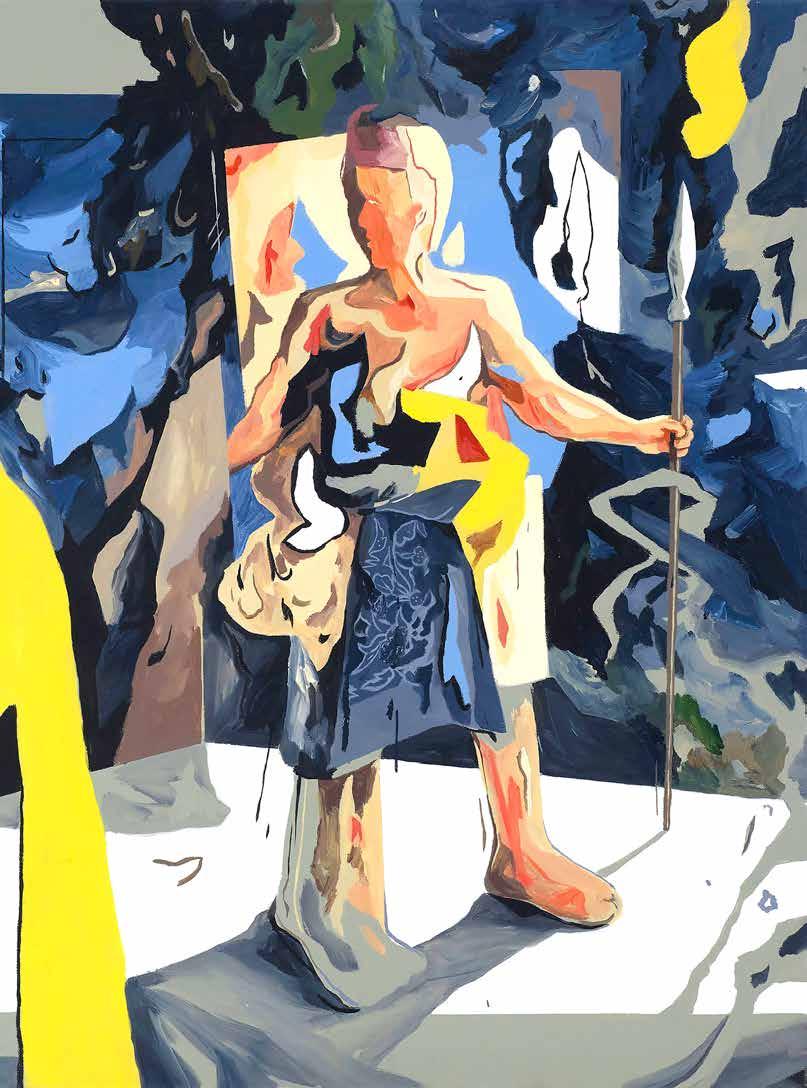

Firdaus Ismail Malaysia

p90

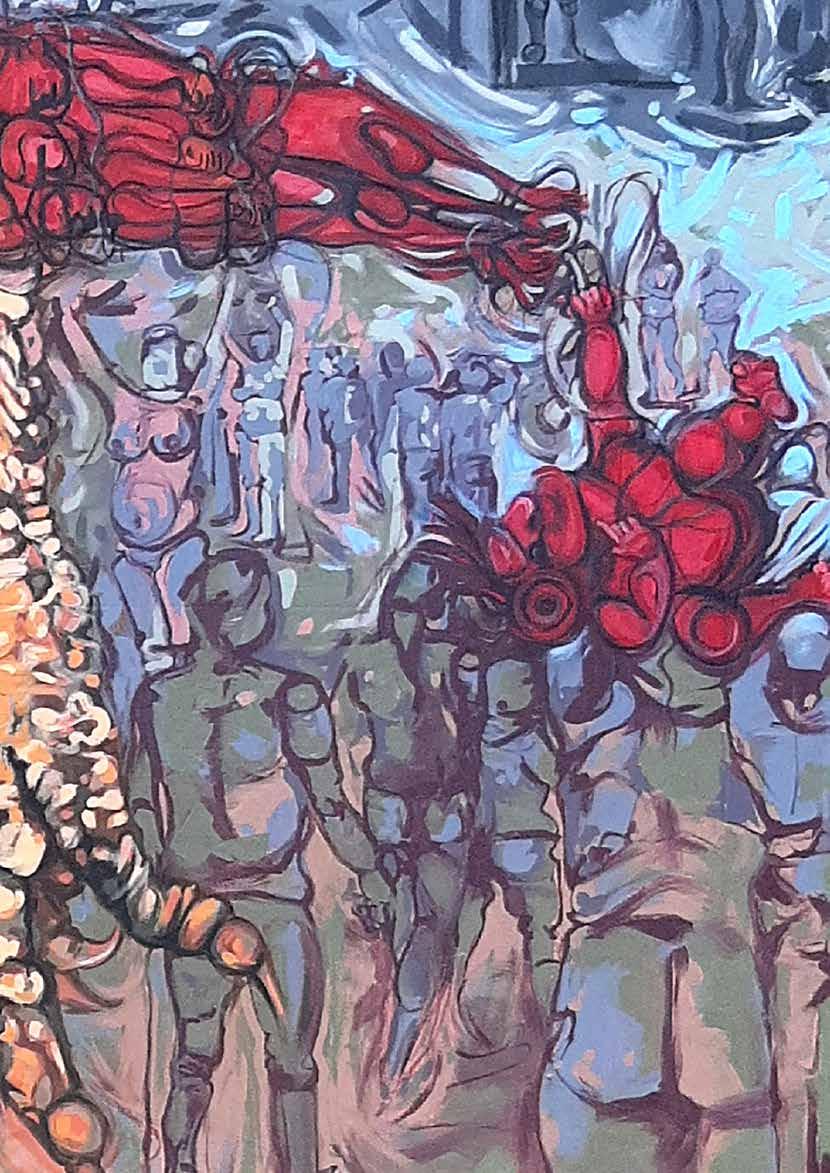

Tantra the Infinite

Papia Ghosal exhibition review UK

p102

Giovanni Cerri and Luo Qi exhibition China

p122

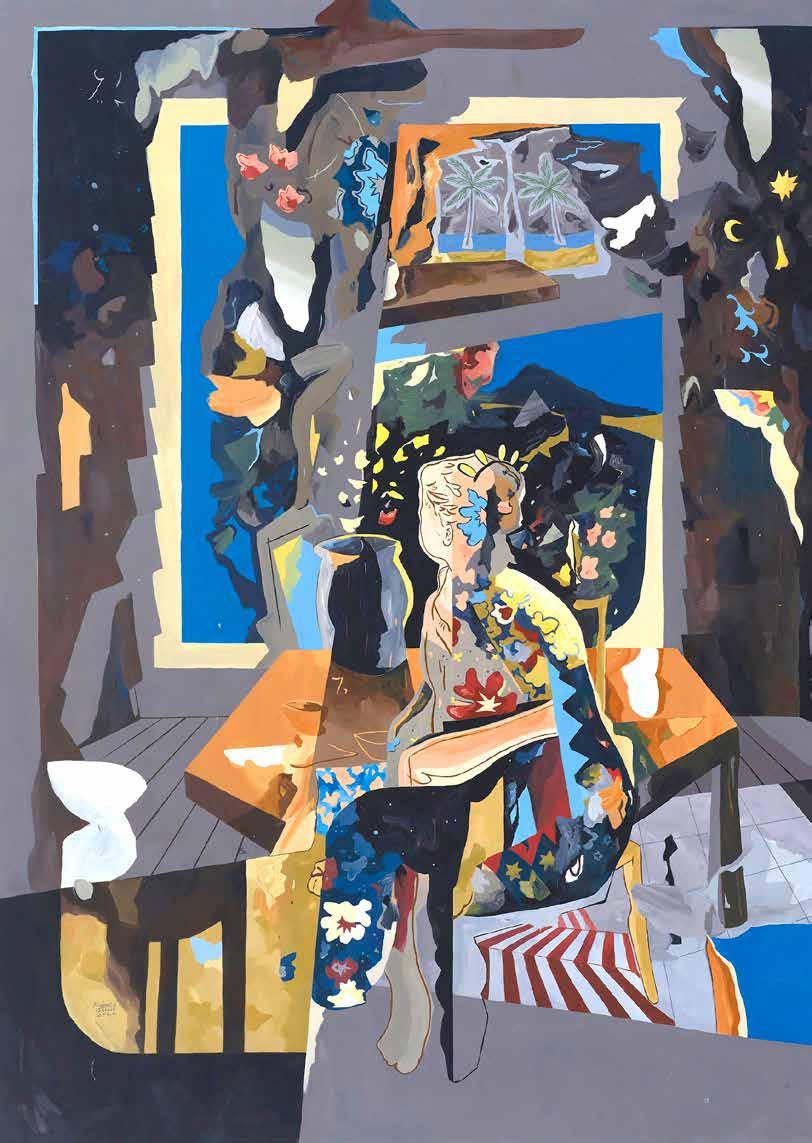

Serrano’s Neo-Surrealist Flora

Rafael Serrano Los Angeles

p136 Arjun Das

Carvings with discarded materials from India

p148

p162

Rickshaw GirlHere in Albion, the snowdrops, croci and daffodils are pushing through, heralding a new spring

The Blue Lotus magazine blossoms again in this new year from myriad points in Asia, and from Los Angeles in the US of A, to delight and intrigue the lovers of Arts and cultures.

Submissions are encouraged to be sent to martinabradley@gmail.com

Take care and stay safe for Covid 19 and its variants are still with us. Martin

(Martin A Bradley, Founding Editor)

Image © by Martin Bradley

Image © by Martin Bradley

Image © by Martin Bradley

Image © by Martin Bradley

“Every woman has known the torment of getting up to speak. Her heart racing, at times entirely lost for words, ground and language slipping away - that's how daring a feat, how great a transgression it is for a woman to speakeven just open her mouth - in public. A double distress, for even if she transgresses, her words fall almost always upon the deaf male ear, which hears in language only that which speaks in the masculine.”

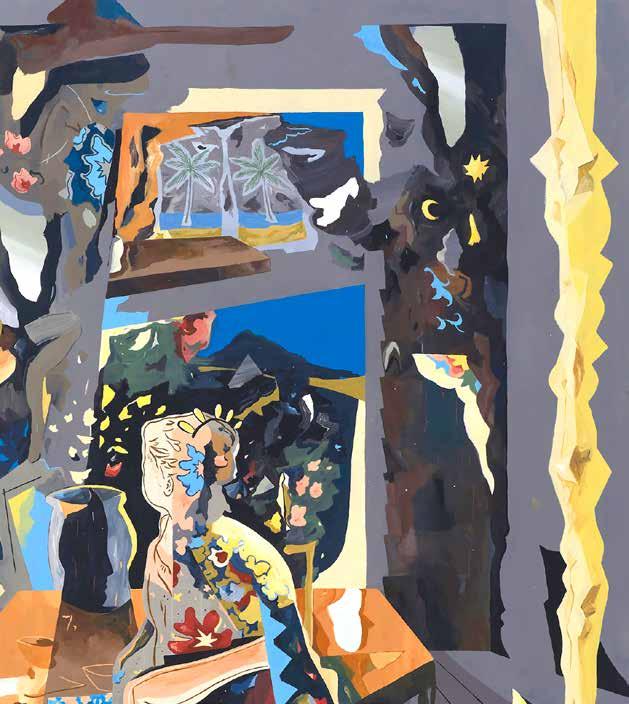

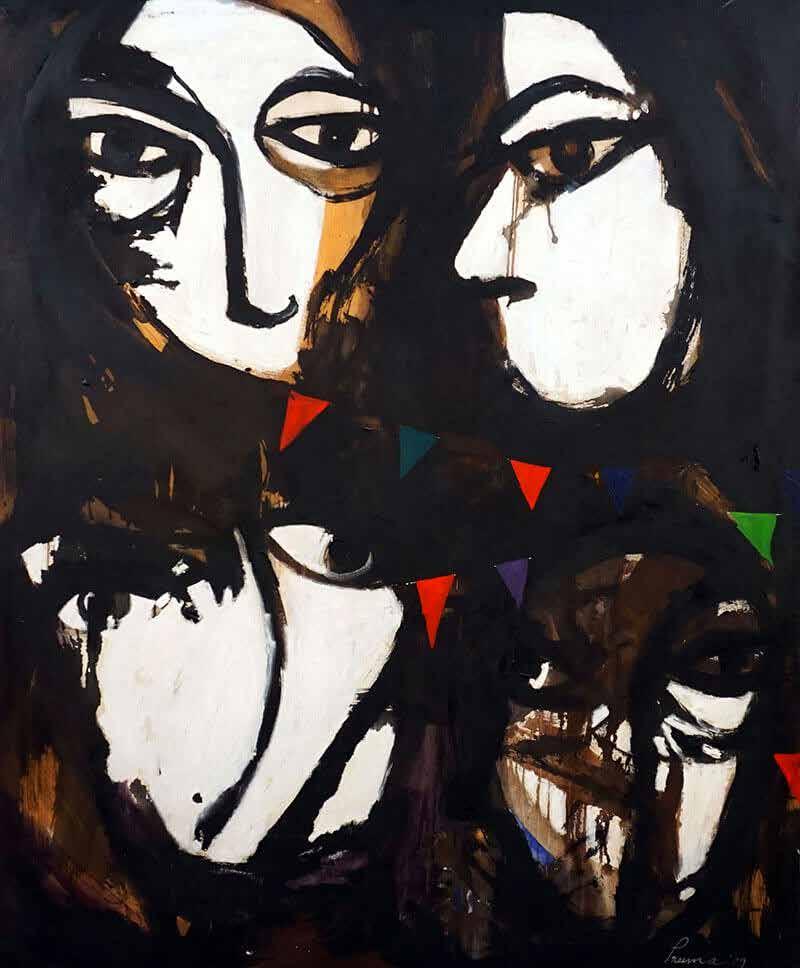

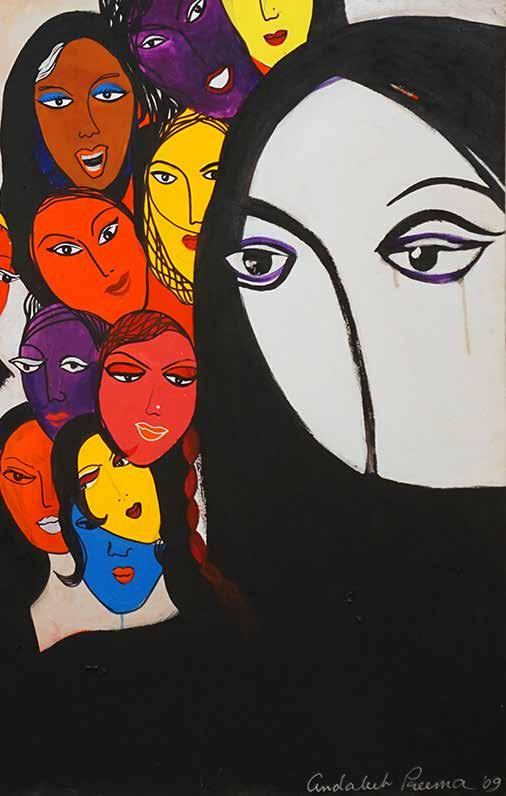

HélèneI met with the Bangladesh artist Preema Nazia Andaleeb (aka Nazia Andaleeb Preema) at Liverpool Street rail station, London, in the December of 2022. We walked and talked about life, philosophy and the breadth of her art making. We settled in a venue in Finsbury Square, near to the Liverpool Street rail station, to talk more.

It was there over a luncheon of selective ‘small plates’ (appetisers) that the artist presented me with a copy of her voluminous book titled ‘Preema Donna: an infinite journey’ (Cosmos Books, Dhaka, 2019).

NB a ‘prima donna’ (in Italian) is literally the ‘first lady’, prima - first, donna - lady. The term originates from Italian opera during the sixteen century and refers to an institution of strong women within opera’s culture. Donna can also mean queen. Preema Donna becomes a play on ‘Prima Donna’, Preema - woman - queen. The use of Italian for the title of her work is not simply a play on words, but an important link back into the Western history of art itself. Back to artists like Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino) and paintings such as ‘La Donna Velata’ (‘The woman with the veil’, 1515) That painting is one his most famous portraits, where he demonstrates his abilities in painting textures, using chiaroscuro, presenting us with the notion of the constantly sidelined, or ‘veiled’ woman, her mystery and beauty.

In the preface section ‘Limitless Journey of Possibility’ (p14) of her book ‘Preema Donna’ the artist mentions “Art is a question to me, not an answer. Hence, as an artist I am always alive, like art, travelling from soul to soul.”

For Preema Nazia Andaleeb there is no such notion as Leo Tolstoy’s ‘What is art’ (Russia 1897). All materials, and any material, may be conscripted to her purpose of art-making, including performance art, using her dancing and performance skills. For her, and art’s, purpose is to communicate the essence and urgency of communication, and in whichever way her intrinsic purpose demands. Notions of flatness vs dimensionality, width, height, length, breadth, time, material/medium become utilised in her works for, as Marshall McLuhan 2 and John Berger 3 intimated, often the medium becomes not just the conveyor of the message, but frequently the message itself.

Like many artists Preema Nazia Andaleeb does not limit herself to one singular mode of expression. Instead, she organises photographic elements, paints in oils and acrylics, creates with digital media, performs modern choreographic movements with intimations of the traditional Indian dances (such as the Tamil classical dance Bharatanatyam, she has studied), to illustrate body and gender politics and generally to aid greater knowledge of the plight of women in misogynistic relationships and cultures, utilising a vast array of mediums when and where she

Face of women

deems appropriate.

The Tate Gallery online reminds us

“The use of mixed media began around 1912 with the cubist collages and constructions of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and has become widespread as artists developed increasingly open attitudes to the media of art. Essentially art can be made of anything or any combination of things.”4

In Preema Nazia Andaleeb’s use of non-traditional modes of art making, she has commonalities with 20th century Western Modernist avantgarde artists such as the adherents of Cubism, Dada, Surrealism and Fluxus movements. Artists like Salvador Dali, Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso, whom she favours (along with the Georgia O’Keeffe, and her ‘performative processes’ photographed by Alfred Stieglitz).

Preema Nazia Andaleeb has similar knowledge of great Indian artists, like Jamini Roy (he who had developed a ‘modern’ Indian art by looking towards indigeneity in a ‘folk renaissance’); as well as the expressionistic boldness of the great polymath Rabindranath Tagore.

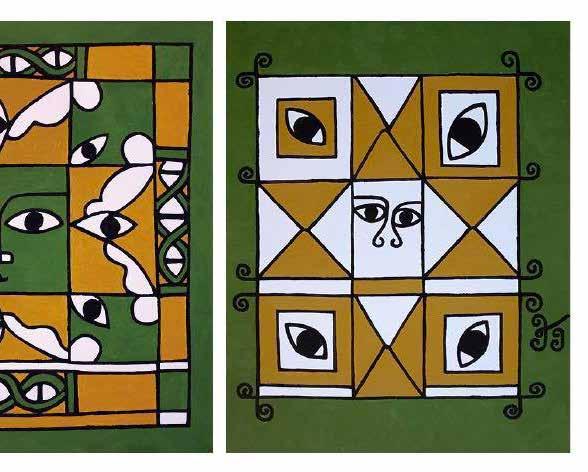

Within Preema Nazia Andaleeb’s book there are reminders of that indigeneity in Jamini Roy’s work in her paintings such as ‘Women of Abstraction 10’ (2018, p16), ‘Beyond Identity: The Sum of her Parts’ (2018, p27) and an earlier work ‘Haunted Existence’ (2014, p156). It’s the large almond shaped eyes. They are remnants of a Bengali folk tradition coupled with the darkened ferocity of Rabindranath Tagore’s paintings of women. Like Roy and Tagore (in her paintings of women) Preema Nazia Andaleeb situates herself within ‘Modern’ Indian, but more especially Bengali roots, and their modernist reinterpretation of folk art, rather than exhibiting any overt Western intimations.

Prima Donna she may be, but Preema Nazia Andaleeb does not (in the English vernacular) ’act out’. She ‘talks out’. She is a woman who firmly grasps the baton of female suppression and re-creates within the sphere of concepts

concerning the subordination of women. In Preema Nazia Andaleeb’s work there are hints of Antonio Gramsci 5 and Gayatri Spivak 6. Notions of the ‘subaltern’. Preema Nazia Andaleeb subverts the traditional muted role of the mythic Radha (beloved of Krishna), from the ancient Hindu Radha/Krishna story of the humble gopi (milkmaid) who became the beloved of the god Krishna. Preema Nazia Andaleeb brings Radha into modernity.

Spivak argues

“

...between patriarchy and imperialism, subjectconstitution and object-formation, the figure of the woman disappears, not into a pristine nothingness, but into a violent shuttling which is the displaced figuration of the ‘third-world woman’"7

In her series of work, titled ‘Concept of Modern Radha’ (pages 234 to 245 in the book), Preema Nazia Andaleeb de-veils Radha, de-mystifies and dis-entangles her from subaltern entrapment. Radha is seen as woman.

Jessica Frazier suggests

“

In the theological narrative poem the Gitagovinda, Radha is a passionate woman who both becomes divine, and incorporates her divine lover and audience into her divinity. The narrative form of her iconography manifests the emotional reason of an embodied religious agency, and through the affectivity of the poem she is able to share this fluid subjectivity, manifesting a pluralistic form of monism that is only one of Hinduism’s many variations on a supposedly “pantheistic” model. Patterns of subjection are traded for alternating dynamics of passionate commitment. In Indian culture Radha continues to serve as an exemplary model of female-neutral subjectivity for all persons—an active, non-substantial, shared, strong self that rationally embraces its (religious) passions.” 8

The next book chapter in ‘Preema Donna’ is, fittingly, ‘Cosmopolitan Women’, in which the artist makes good use of a variety of art-making techniques to present the diversity of women

within the Asian diaspora, as ‘women of the world’. The painting ‘Cosmopolitan Women’ (p256, 2014) is, poignantly, a mixed media piece used as the front cover of the artist’s book ‘Preema Donna’, and it’s slip cover. We see oblique references to the fashion magazine ‘Cosmopolitan’, its Western style and glamour, with photographic cut-out images. These become contrasted with images of women with hijab (hair covering), and some niqab (a veil that covers the face, but leave the eye area uncovered) while others wear the burqa (a female full body covering), none of which are technically compulsory in Bangladesh.

There is the bleak contrast between what one woman might wear irrespective of religious affiliations, and the raiment available to some choosing to wear for religious reasons, willingly or unwillingly.

Unspoken are the words ‘slave to fashion’ and the anomaly of being free and yet a slave to fashion trends. However, the very real enslavement continues in Bangladesh’s sweatshops, where workers are paid a pittance to produce garments for brand named companies, to sell to followers of fashion. As East Bengal, the link to Western fashion and the dye colour indigo runs deeper into issues of Colonialism, the Raj, and indigo farmers’ riots (Neel Bidroho, 1859).

While there differences of opinion as to whether ‘Performance Art’ is Art, Preema Nazia Andaleeb has continued to engage in aspects of ‘performance, since young. The Tate Modern reminds us that

“Jonah Westerman remarked ‘performance is not (and never was) a medium, not something that an artwork can be but rather a set of questions and concerns about how art relates to people and the wider social world”.9

Looking back into the history of Western Art, performance (in the visual arts) is often retrospectively connected to avant-garde affiliations such as the Italian ‘Futurist’ productions and various manifestations of

‘Dada’ cabarets of the 1910s. Later (1929) in the second Surrealist Manifesto, Andre Breton was, controversially, to write “The simplest surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.” 10

Preema Nazia Andaleeb, while provocative in her presentations and performances, shocks in ways that do not require the phallic presence of a gun. She uses presence of mind and the female body as seen from page 272 through to page 361 in her book, Preema Donna. There, she reveals that ‘woman’ does not now need to counter the “language only that which speaks in the masculine” to overcome notions of transgression and the fears of Hélène Cixous, and Gayatri Spivak’s concerns. Instead, she (Woman) becomes free.

Ed1. Cixous, Hélène’ Le Rire de la Méduse’ (The Laugh of the Medusa) 1975

2. McLuhan, Marshall, The Medium is the Message, 1964

3. Berger, John, Ways of Seeing, 1972

4. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/m/mixed-media

5. Mondal, Disha, The Forgotten Bengali Cubist Artist: Gaganendranath, Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 3 (2021)pp: ISSN37 (Online):23219467

6. Gramsci, Antonio, Notes on Italian History in Prison Notebooks 1929 -1935

7. (Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. Ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1988. 271-313).

8. Frazier, Jessica. (2010). Becoming the Goddess: Female Subjectivity and the Passion of the Goddess Radha. 10.1007/978-1-4020-6833-1_13.

9. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/performance-art.

10. Breton, Andre, Second Manifesto of Surrealism in Manifestoes of Surrealism, Ann Arbor Paperbacks, The University of Michigan Press, 1969, p125

Bumi Bertuah is a synthesis of all of Rafiee’s travels. This new series of paintings capture his experiences and his memories along his long travels across several continents, countries and places where he encountered all kinds of people from various ethnic groups and cultures, walked in the footsteps of famous European artists, and admired the uniqueness and greatness of the Creator.

In this series, Rafiee challenged himself to use acrylic, as opposed to oil paint, his favourite and usual medium, as can be seen in the previous series of paintings. Holding on to the principle that painters should be versatile, he does not want to restrict himself to just one technique or style. He wants to challenge his mind and his creative process.

G13 Gallery opens from Tuesday – Saturday, 11 am to 5 pm. Closed on Sunday, Monday & Public Holiday.

For enquiry, please contact us at: –

+6013 – 234 2126 (Wendy) or via WhatsApp

WWW.WASAP.MY/60132342126

+6019 – 211 4697 ( Kenny ) or via WhatsApp

HTTP://WWW.WASAP.MY/60192114697

+6011 – 1197 8679 (Yu Ting) or via WhatsApp

WWW.WASAP.MY/601111978679

Rebecca Haque

Rebecca Haque

Mourn a cold, dark, bloody day in distant December. Dawn, dusk, dew, and nightfall. Silent death squads knocking at the door, targeting noble names on the assassin’s hit-list.

Lament the loss. Weep the tears. Cry for the slaughter of the illustrious sons of the delta. Wail at the memory of the dead desecrated in the ditch.

Feel the agony of grief. Our teachers and our seers, taken from usto the sequestered pit. Freedom on the horizon and the marching Mukti Bahini carrying the flag of liberation could not save them from the savage ambush.

On the fourteenth of December, raise your arm to salute, to remember the martyred intellectuals. Murdered with such diabolical, secret strategy to

cripple the new nation. Dare to shout. Dare to accuse. Dare to punish the craven killers. Your Nation asks this of thee: do not flinch, seek justice.

In 1971, Anthony Mascarenhas was an eyewitness to the brutal acts of torture and unholy massacres of innocent civilians. This brave Pakistani journalist, hounded out of his own country for the truthful account published later in that year in London, ended his reportage from Dacca in October 1971. But the final lines of his book are ominous in the prescient knowledge of the horror that was to follow. He writes: “ Bangla Desh is too big, too explosive and has too many outcroppings to be either swept under the

carpet of international opinion or to be painlessly swallowed by all parties concerned. Each of its aspects—there refugees, famine, genocide, the total alienation of the millions of Bengalis, the shattering effects independence would have on West Pakistan – by themselves are major international problems. Together they constitute a greater disaster and a graver threat to peace than Biafra and Vietnam or anything this generation has known…. We are only just entering a new area of darkness. It will be a long time before the light begins to show at the end of the tunnel. ” ( Vikas Pub.: India, 1971, pp.145-6)

In the Preface, dated London, 1 October 1971, Mascaren has comments, “What I saw in East Bengal was to me more outrageous than anything I had read about the inhuman acts of Hitler and the Nazis. This was happening to my own people. I knew I had to tell the world about the agony of East Bengal or forever carry within myself the agonising guilt of acquiescence.”(p.v). The writer here is unequivocal about his political affiliation and equally firm in his moral judgment. However, it is a travesty of history that even after more than four decades since the atrocities were committed in 1971, after the gruesome carnage of the night of 25 March 1971, and the satanic ritual killing on 14 December 1971, so many perpetrators of evil have not been identified and prosecuted. In recent times, a few known collaborators have been tried and sentenced, but we have yet to see signs of guilt or true remorse in them. How can we offer forgiveness in the face of an absence of a moral conscience? It is unnatural for the perpetrator to expect clemency when there is no clear attempt at redemption through confession of participation in crimes against humanity.

The children of Bangladesh have this heavy burden of a legacy of a

holocaust. For us all, there can be no closure until there is full redress, until there is full disclosure about the events of 1971 to the people of Pakistan, until their government discards the cloak of denial and offers a formal apology for future generations to exist in mutual trust. It is not enough for scholars to enter into research and debate on Partition and Liberation War studies. Facts of recent history cannot, and should not, be confined within academia. History is for each of us to know in its authenticity from eyewitness accounts and scholarly documents. We may not know it whole at once, but we can weave the torn fragments into a tapestry of truth. This is necessary to guard against fabrication, or wilful ‘rewriting’ of history as has happened in fascist dictatorships in the past. Democracy, by its very definition, guarantees its citizens free access to information, to liberty of movement and speech, to justice and equal opportunity for work. These are the precious objectives and values for which millions of Bengali civilians, University students, young Mukti Bahini men and women, and visionary intellectuals, were martyred. They died for a noble cause; they shed their blood so that our children would be born in an independent nation. A supreme sacrifice for a supreme purpose.

Mascarenhas has equated the horror of 1971 with Hitler’s regime, as have so many since then. It is a natural comparison between similar states of evil. We are today constantly comparing our War Crimes Tribunal with the Nuremberg Trials of postWorld War II. The German-Jewish philosopher, Hannah Arendt, chose to be present at the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, and in her book wrote the famous, now oft-quoted, words, “the main lesson to be gleaned from [Eichmann’s] life was one of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying

banality of evil.” Arendt’s argument about the relation of obedience to authority parallels the argument of the American social psychologist, Professor Stanley Milgram. After controversial experiments conducted at Yale beginning in July 1961, the year after the trial of Eichmann in Jerusalem, Milgram tried to answer the question “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?” He concluded that people obey through coercion, and obey either out of fear or out of a desire to appear cooperative – even when acting against their own better judgment and desires.

However, there is recent dispute about this theory. In The New Psychology of Leadership (2012), Alexander Haslam and Stephen Reicher extend their “BBC Prison Study” series of experiments and collaborate with a number of researchers to develop a social identity analysis of leadership. This work focuses on the role of perceived shared identity as a basis for mutual influence between leaders and followers. It argues that leaders’ success depends on their ability to create, represent, and advance a social identity that is shared with those they seek to motivate and inspire. Haslam and Reicher contest Milgram with regard to one crucial point. They argue that Eichmann, a committed Nazi, nonetheless ‘took on organisational challenges with fervour and imagination. If he thought orders were not sufficiently “on message”, he would likely disobey them, and where none had been given, as was often the case, he would still “work towards the Fuhrer” in a creative way. He was convinced that the cause he was advancing was right. The truly frightening thing about

Eichmann and his ilk is not that they didn’t know what they were doing, but that they knew full well what they were doing and believed their actions to be justified, worthy and noble.’ (New Scientist, 13 Sept. 2014, p.28)

Rational consideration of these new scientific studies by social psychologists, as well as research work undertaken by anthropologists in the last two decades on conflict studies in the“killing fields” of South Asia, make us posit significant political and ethical questions regarding the relationship between the occupying military army and the East Pakistani collaborators. Who provided the names on the hit-list to the local

goons on the eve of Bangladesh’s victory? Did the collaborators work for the military junta in a ‘creative’ way to advance their careers? Did they justify their actions on religious grounds? Surely, one point is clear to all of us who lived through the travail of those days: none of the collaborators were coerced.

The nation mourns the loss of the intellectuals on December 14.Memorials embody memory, and material objects of art and architecture memorialise both valour and losses of war. Around50 top intellectuals of the country – doctors, engineers, lawyers, litterateurs, academics, journalists, and also top bureaucrats and business elites, were killed in cold blood. The intellectuals were both Hindus and Muslims. Their bodies were found in a brick kiln in Rayarbajar, in Dhaka, lying face down, blindfolded, hands tied behind their backs with red pieces of cloth.

There are two Martyred Intellectual Memorials in Dhaka, the one in Mirpur, built in 2002, is the site of all official commemorations on Intellectual Killing Day, Shaheed Dibosh. The Rayarbajar Memorial was built from 1996 to 1999 after the prize-winning design submitted jointly by architects Fariduddin Ahmed and Jami-ulShafi. In an interview with a research scholar in 2005, Fariduddin explained the symbolism of the architectural and spatial dimensions of the Memorial: “Rather than seeing this memorial as a war memorial, the architect defined it as asritishoudho –a monument to memory. Unlike the Taj Mahal, which is a mausoleum, tinged with the pathos of romantic love,Ahmed clarified that this was different. This was a tomb that upheld tradition while also announcing the demise of empire and imperialism and the deaths caused by it. This makes the Martyred Intellectuals Memorial both a memorial and a shrine, drawing its inspirations from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial,Ahmed emphasised.” (Space and Culture, May 2007)

The writer is a Professor in the Department of English, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Martyred Intellectuals Memorial

Martyred Intellectuals Memorial

Meditation for hunger (roti)

Mother and Childhood (roti)

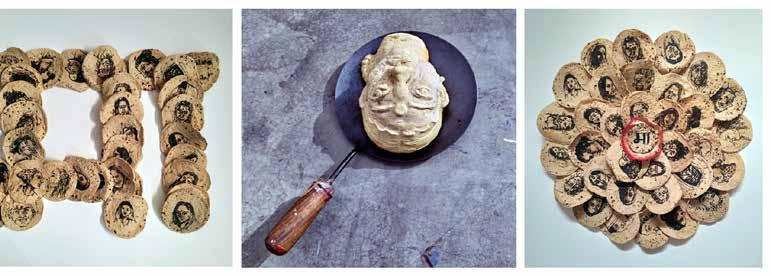

Throughout the history of human civilisation and beyond the geographical landscape or manmade borders, bread/roti is the most intent and vibrant part of our life. The material itself has lots of potentials to evoke several questions, sometimes incite very personal experience or sometimes it transverses the personal realm and reaches to a collective sphere. As Roti is subjected to our basic needs, it continuously comes in different forms of artistic expressions, sometimes with different metaphor or sometimes just as a harsh reality. Here, my attempt is to go beyond to this dilemma of metaphor and reality and unfolds the associated empirical experiences around this intent part of human life through a discursive method.

Initially, I start collecting the waste rotis from a roadside restaurant, near to my place and expressing my childhood memories, relationship between roti and motherhood. Eventually, the idea transforms into in different directions, addressing the relationship between woman and roti or unequal distribution of foods, spillage of foods, food scam etc..

During this pandemic and worldwide lockdown situation, the series opens up several different aspects of our society. The roti makers who used to make numerous numbers of rotis every day in different roadside restaurants, are now facing a severe crisis of food. Now, it is the time to rethink how our basic needs are forced to be alienated from our realm through different socio-political mechanisms.

Anupam Roy (Artist and Writer) New Delhi, IndiaRajib Sikdar

Recipient of all India awards from AIFACS, New Delhi (twice) and from Camel Foundation Camlin Ltd. Mumbai, Rajib Sikdar was born in Nadia, West Bengal in 1979. He obtained his BFA degree in painting from Bengal Fine Arts College, West Bengal and masters from Agra University. He is a freelance artist and working in New Delhi. Apart from having many group and solo shows at Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi, Visual Arts Gallery, New Delhi, Birla Academy of Art & Culture, Kolkata, Lalit Kala Akademi, Lucknow, AIFACS, New Delhi, Jawahar Kala Kendra, Jaipur, National Academy of art (Regional Centre), Lucknow, LKA (Srimanta Sankaradeva Kalakshetra), Guwahati, State Art Gallery, Hyderabad, Academy of Fine Arts, Kolkata, Shrimati Art

Gallery, Kolkata, Jehangir Art Gallery, Mumbai, Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath, Bengaluru, India Habitat Centre, New Delhi, Kala Srot, Lucknow, Noti Binodini Memorial Art Gallery, Kolkata etc.. he has also participated in several state and all India art exhibitions & camps across the country including the 57th national art exhibition, LKA, New Delhi and fetched many more awards to his credit. His works are in the collections of many art galleries (including LKA, New Delhi) several corporate/ private collectors of art in India and abroad. Studio: New Delhi, India.

Phone: +91 9368689730

Email: artfamily000@gmail.com , rajib.sikdar.art@gmail.com

Mountain of Nightmares (roti)

Hungry when hungry (roti)

Water Tales is a visual romance by Stefano Morrone with SafeSpaceBTB.

It is art storytelling that drowns into the desires, fears, and memories of nine people belonging to the LGBTQIA+ community of Battambang, Cambodia.

Water is used as a theme in the portraits, as it is connected to the natural landscape. Battambang is known for its flooding during the rainy season, when the city seems to float due to the huge quantity of water present. Water also represents a transparent veil which society places on the LGBTQIA+ people to mute their voices.

In Battambang, before SafeSpaceBTB was born in 2018, there were no spaces for LGBTQIA+ people. The context is particularly traditional, and rural. Most LGBTQIA+ Cambodians try to escape to the capital city or other countries, where it is easier to integrate into the local community. This project was born from the necessity to learn more about aspects of this specific context in Cambodia, a society still in need of change and where the family is the heart and center of all decisions. This limits LGBTQIA+ Cambodians getting their rights, and stops them from being themselves.

Since I was a kid, I used to love to wear make up and dress up. Everyone, including my family, told me that was wrong, that was not a good thing to do, but the more they told me, the more I tried to find the way to get to feel beautiful. And with time I got to find my own self. This is what I'm, a very beautiful person.

Rapech is a student of traditional Khmer dance in Phare Ponleu Selpak Performing Arts School. She is collaborating with youth groups for human rights, mostly LGBTQIA+ rights.

When I start a new relationship, it's just finished after a while. Men tell me that I'm too sweet, that I need to be more masculine. I don't want to change, I'm sweet like the smell of Khmer flowers.

Chamroeun is a business owner; he sells everyday in his family’s convenience store.

I got bullied by friends for being gay, then I took art as a friend Now I realize that art is my best friend and that makes me change so much, from an introverted person to a happy person.

Karona is a student at Phare Ponleu Selpak Visual Arts and Applied School in Battambang He is also a very talented freelance artist.

Rapech

Chamroeun

Karona

Rapech

Chamroeun

Karona

“The rickshaws with its decorations and paintings create such a pervasive and emblematic feature of urban life in Dhaka City that it has given birth to social practices, rituals, and festive events. New rickshaws are always a blaze of colours and paintings in Dhaka City, which is rightly called the Rickshaw Capital of the World”1

In most of the literature studies and theses a rickshaw puller (Rikaśācālaka in Bangla) is assumed to be male. However, in the Sleeperwave Films/Half Stop Down’s presentation ‘Rickshaw Girl’ (2020), the rickshaw puller is female. The film’s director Amitabh Reza Chowdhury reveals

“This is a personal story, shot in quasi-documentary style, using the kinetic energy of the rickshaw trade as the engine that drives the visual storytelling.”

The film’s narrative uses various visual and script devices which neatly foreshadow Naima’s journey into rickshaw pulling. By the time she begins her new life, we have already understood why.

It is interesting to note that Eric J. Adams’ film production of Rickshaw Girl is an adaptation of the 2007 young people’s short novel authored by Mitali Perkins. The narrative concerns the young Naima, (played in the film by Novera Rahman in the lead role). Naima is a Bangladeshi girl who loves to paint traditional ‘alpana’2 decorations, but her family is poor and her rickshaw-pulling father is ailing. Naima goes in search of a job and money in Dhaka. After some misadventures Naima becomes involved with the male world of rickshaws and is initially rejected. She questions why.

“Then what do you need to be a rickshaw puller” Naima asks the rickshaw boss.

“Need to be a man first” is his answer.

As you can see, the film takes on that issue of appropriate gender jobs, and the general misconception that a puller/cycler of rickshaws must be male. Later in the film, Naima, disguised as a boy called Naim, is told by a female rickshaw boss who has given her shelter for the night…

“Be what you are. There’s no pride in being a man”.

Chowdhury’s film ‘Rickshaw Girl’ is a beautifully shot film. At the onset we, the audience, are impressed with an appropriately shot painted illustration sequence of a giant peacock, with birds entwined in its feathers. Gradually, we are led to a young girl (Naima), who is painting beautiful indigenous folk art ‘alpana’ (or Rangoli) pieces for a forthcoming wedding.

After an incident which brings us and Naima rudely back to earth, we are led into the dazzling title sequence. This is when Naima has arrived home and told, by her mother, to take a shower in the village ‘pond’. A celebratory festival of colours ease from her clothing and form the background to the film’s title ‘Rickshaw Girl’, which appears in a ‘brush’ typeface (font).

In this cleverly written and directed film, it is impressive how easily animation is intertwined with live action to add, not subtract, from the general narrative quality. The animation is very much part of the storytelling and keeps it grounded in the art loving Naima, enhancing our understanding both of her youth and her predilection for folk art which, like language (Bangla) is Bangladesh intangible cultural

heritage, or cultural identity, and very dear to the hearts of the Bangladeshi people.

Towards the end of the film, in an effective segue into an intoxicating daydream animation, the audience is led back into the world of Naima’s art, then uplifted to soar into illustrated skies. These scenes remind the audience of Naima’s connection to her youth, her love of art, as well as demonstrating the values of personal choice, freedom as well as the importance of preserving notions of personal and national culture.

These days, despite various curbs to their use, rickshaws continue to be eye-striking, convenient and plentiful on the streets of Dhaka, Bangladesh. So much so that Dhaka has been dubbed the ‘rickshaw capital of the world’, with up to 400,000 rickshaws in that city.

The ‘jinrikisha’ (human-pulled vehicle), was invented in Japan, in 1869 and, with pneumatic tires, was introduced into India (Simla) in 1880. East Bengal (Bangladesh) received rickshaws from Calcutta (Kolkata) sometime in the 1930s, but they didn’t take off as public transport until 1941. Rickshaws (but strictly speaking these bicycle pulled vehicles could be called cycle-rickshaw, rintaku, or trishaw) have become part and parcel of life in Bangladesh, encouraging notable Bangladesh fine artists to feature them in their paintings, including Farida Zaman - ‘Couple in a rickshaw’ and Rokeya Sultana - ‘Madonna on the rickshaw’.

It is interesting to note that elsewhere, and in real life, one internet ‘stock photo’ tells us that “Amena Begum from Comilla district is the first female rickshaw puller in Dhaka city Bangladesh 1994”, while in 2017 there

was a short documentary film ‘Sumi, Pulling Rickshaw in a Man’s World’ (Urban Tales, part of China Daily Asia Pacific), by Director / Producer / Camera / Editor: Claudia Hinterseer. It is where Sumi Begum is revealed as a real-life female rickshaw puller in Dhaka, and slightly inaccurately promoted as ‘Dhaka’s only female rickshaw driver’. Sumi Begum is shown pulling passengers through the streets of Dhaka in the very same year that an article in ‘The Hindu’ points towards Mosammat Jasmine as the only female rickshaw puller in Chittagong.

Furthermore, in a story not unlike Eric J. Adams’ 2020 film production ‘Rickshaw Girl’, an Eid telefilm Rtv Drama, called ‘Rickshaw Girl’ (2022) Directed by Rafat Mozumder Rinku, further posits the notion of female rickshaw drivers in a dramatisation with Tanjin Tisha playing the role of a female rickshaw-puller named Shikha.

Amitabh Reza Chowdhury’s film ‘Rickshaw Girl’, produced by Eric J. Adams, is a poignant and endearing film, suitable for all ages and sensibilities.

Ed1. Bangla Academy submission to the 2018 UNESCO representative list.

2. Alpana: Girls and women paint these geometrical or floral patterns on the floor during celebrations and holidays. They use crushed rice powder to outline the design, and decorate with coloured chalk, vermilion, flower petals, wheat, or lentil powder. Some designs are passed down from generation to generation for hundreds of years. Page 7, Rickshaw Girl, Mitali Perkins, Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc., 2007

Pendakian tun mamat dari astaka ke puncak mahligai

Pendakian tun mamat dari astaka ke puncak mahligai

Seated woman by the rear window

Seated woman by the rear window

Recognising a piece of art done by an artist of a particular technique almost always falls under how distinct it looks to one’s eye. To the non-casual observer, it speaks of a highly curious scrutinisation for a painting to inspire a precipitate interest. For how it was visually arresting, it must also contain noteworthy subjects to exchange reasoning and opinions with.

Firdaus Ismail has this exact quality as an artist. Appraised as a young practitioner, his works relayed a form of art that informs contemporaneity, steering spectators to contemplate what they are seeing in order to comprehend. His methodology since his graduation with a BA (Hons) in Fine Art, Majoring in Printmaking at UiTM Shah Alam in 2012 progressed exponentially, with works ranging from figurative, to surrealism, to semi- abstract, or a combination of all three. Firdaus has exhibited extensively from 2009 until 2022, showcasing different approaches that expanded his artistic instincts to an admirable level. From printmaking to painting, it is, without a doubt, his exchanging practices that contributed to his current mode of making.

Investigating the origin of Firdaus Ismail’s interest in Malay folklore, classical, and mythical characters dated back to 2019, when his then paintings — having refined in terms of style — developed a consistency in contextualisation. A few examples can be seen in The Duel I and II; two pieces that are evident with subjects centred around Malay warriors that which was deconstructed and reformed into a western setting. Both paintings were inspired by Orazio Gentileschi, a renowned Italian female painter of the baroque era in the 17th century.

Following this progress in identifying and placing the Malays within contexts in a parallel, yet intriguing setting seemed to be his direction after that. Lebai Malang —

After Ibrahim Hussein (2020), The King of Cock Fighters (2020), The Dreamer (2020) and The Dreamer with Starry Night (2020) all alluded to bardic tales, epics, and fairy tales, amongst other genres in Malay folklores. His persistence in unearthing these legends into a contemporary visual is essentially explored in his very first solo exhibition, ASTAKA. Engaging symbolic tradition in oral lores and written works of literature fused with today’s point of view again highlights how ‘contemporaneous’ storytelling in-between eras can be.

Even when all of these stories are orally delivered, and subsequently recorded

in written format, their transmission reached and instigated a period of time that examined itself with intimate moral values. Varied interpretations are still very much in discussion to this day regarding Malay legends, regardless of format. The book Malay Annals, or Sulalatus Salatin, is being studied academically and extensively, at one time listed under UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme in 2001. This particular piece of literature that was composed between the 15th and 16th centuries speaks volumes about recording the common practice of oral tradition — a time when a civilised nation is culturally entrenched with different forms of glorified entertainment.

The oral forms of this lore are transmitted primarily through nursery rhymes, folksongs, theatrical exhibitions, and stories that are commonly told from parent to child. Nomadic storytellers that would roam the temples, marketplaces and palace courts also play a large part in the insemination of the oral traditions throughout the populace, often accompanied by music as well through forms of composed poetry and prose. The oral traditions are often integrated with moral values and some may also include stories of talking animals. [1]

One of the significant stories in the many Malay folklore is Puteri Gunung Ledang (Princess of Mount Ledang), reaching the modern audience when it was popularised in a film in 2004, resulting in a musical theatre — despite both directions were composed as new storylines — due to the immense attention it had garnered. Originally, the story is categorised as a fairytale as it revolved around a metaphysical character/s, Puteri Gunung Ledang/ Dayang Raya Rani herself. The mysticism in this story is retold throughout centuries, describing the Princess as a Bunian or “hidden people” (referred to as ‘makhluk halus’ in Malay), who came from a race with exceptional beauty and grace.

When it comes to this celebrated lore, it is insensible to neglect its metaphysical aspect. Malay storytelling is often inclusive of such things that it is difficult to reject a mystical phenomenon (said, experienced or learned) that grew within the culture at the time. Firdaus further commented that he believes we still reside in a world with parallel existence, which is unseen and unimaginable. His works which predominantly entailed various Malay lore emphasised his genuine curiosity about such a world’s existence.

In the excerpt of Sulalatus Salatin regarding Puteri Gunung Ledang, it is clear that the storyline concluded with morals that define the 15th-century monarchy of the Malay Muslims then. The Princess was rumoured to have an ethereal beauty that rivalled ordinary women, which came to Sultan Melaka’s knowledge who had just lost his Raja Permaisuri Agung. Yearning for a new spouse, he commanded his underlings, Laksamana Tun Mamad and Sang Setia in delivering his wish to marry the Princess. His command was absolute and his underlings were loyal in carrying out the mandate, enduring the adversities and difficulties along their journey to Mount Ledang. Once there, they were met with Dayang Raya Rani, the professed guardian of the Princess — where in truth, it was the princess herself that was under mystic disguise (some interpretations differ, but we shall take into account this metaphysical probability as it was uniformly agreed upon). The infamous seven impossible demands of the Puteri

Seated-woman-by-the-mountain-

Seated-woman-by-the-mountain-

Gunung Ledang expressed by Dayang Raya Rani to Tun Mamad were a subtle way of rejecting the Sultan’s proposal — although the moral values did not end there by how six of the demands could be fulfilled sans one, which was a bowl of Raja Ahmad’s blood, the son/prince of the Sultan.

Puteri Gunung Ledang as a classic fairytale does not stop being interpreted in just literature, film or theatrical form, but also art. Syed Ahmad Jamal was well renowned for his research into Malay traditions and cultures. His works Semangat Ledang (2003) and Tun Mamat Mendaki Himalaya (1984) are exemplified as the pinnacle of Malay modern contemporary art in acknowledging the richness of the Malays’ ‘rupa & jiwa’*, encompassing the aesthetics and Islamic connotations that accompanied it.

“Semangat Ledang” (2003), adalah berasaskan kepada siri karya ‘Gunung Ledang‘ yang menjadi lagenda dan simbol dari aspek alam semula jadi dan alam sekitar. Ia merupakan titik rujukan kepada kegemilangan pensejarahan empayar Melayu Melaka yang masyhur dengan watak Hang Tuah, Puteri Gunung Ledang dan Tun Mamat. “Semangat Ledang” menurut Siti Zainon Ismail (2012) bukan hanya berdiri sebagai mitos sejarah Melayu tetapi juga jauh di belakang telah wujud semangat dunia Melayu dengan simbol gunungan dan pucuk rebung sebagai motif yang memperlihatkan jati diri dan kewujudan kesenian warisan (Muhamad Hanif Hafiz dan Fiqah Qari, 2012). Kebanyakan pengkritik menjelaskan bahawa karya Syed Ahmad Jamal adalah kontemporari yang kaya dan ampuh dengan jiwa Melayu dan Islam. [2]

Borrowing Syed Ahmad Jamal’s concept of Malay and Islamic aesthetics in his paintings added to the point of reference for Firdaus. Synonymously, Firdaus created a version of his own, all the while paying homage to the late famous artist. His work Pendakian Tun Mamat: Dari Astaka ke Puncak Mahligai (2022) sparks immediate recognition with the painting Tun Mamat Mendaki Himalaya (1984) by Syed Ahmad Jamal. Firdaus’s portrayal of Malay legends however clings to a version of storytelling that denotes a theatrical and fantastical sense of style. In this painting, the sequence between scenes can be discerned — from the interior of a Malay house, the Sultan’s palace, the journey to the mountain, and the depiction of multiple characters that are central to the story. The triangle shape — indicating motif tumpal/pucuk rebung — is very much evident, incorporated into the upper portion of the painting, grouping the characters as a symbolical event leading to its climax. Seven smaller triangles are seen on top of it in its designated composition, with Mount Ledang as the background. Floral motifs akin to the concept of Malay batik textiles are also included to emphasise the cultural richness of this legendary story.

In the first few discussions with the artist, the topic of Malay and Islamic values was put at the forefront. There were several dilemmas faced by the artist — questioning the lack of representation of it in contemporary art forms, followed by the need to revitalise an understanding of Malay cultures and traditions. Firdaus’s starting point by referring to past masters is within reason; figures like Syed Ahmad Jamal, Redza Piyadasa, Ismail Zain, Hossein Enas and Mazli Mat Som to name a few were key factors in the widespread art research on Malay cultural identity.

Most notable in Firdaus’s works is how assimilative his subjects are with the contemporary audience. Paintings displaying women seated as a focal point were contextually explained as the ‘anak dara’ in one of the Princess’s seven demands of filling an urn of virgins’ tears*. The portrayal of the women was ambiguously painted in a semi- abstract style, although with further scrutiny, the audience is able to see the urns that are placed beside them. Their expression and position bear resemblance to Redza Piyadasa’s work Seated Malay Girl (1991), as with Mazli Mat Som’s Menanti Nelayan (1965).

“Astaka, menurut kamus dewan (edisi keempat) ianya didefinisikan sebagai pentas khas yang dibina untuk sesuatu tujuan. Sementelah saya, dalam cubaan meletakkan/ mewujudkan diri ke kancah seni rupa Malaysia, sering kali saya membayangkan bagaimana keadaan/rupa andai diri saya menjadi pancaran cahaya (spotlight) di atas pentas (ruang pameran). Di dalam ruangan astaka itu, saya mungkin juga boleh menafsirkan diri saya sebagai pengarah drama/teater atau boleh juga berperanan sebagai aktornya dengan memainkan watak-watak tertentu. Oleh demikian, sebahagian dari watak-watak ini, saya bagaikan meletakkan diri sendiri sebagai proses mengenal jati diri bagi menghidupkan karekter di dalam persembahan”. [3]

His statement about the stage, or astaka, was viewed as an attempt on imitating and implementing a stage-like body of works. His processes are centred on himself as the ‘character’ who assumed all of these roles that are present in the paintings — even becoming the ‘actor’ and the ‘director’. With this thought in mind, he placed himself in the story to identify a sense of self as a modern Malay. Characters like Tun Mamat and Sang Setia in Two Heads (2022) assumed a position of characters with unwavering loyalty, as with the depictions of two warriors fighting in Pertarungan Bersenjata: Keris & Tekpi (2021) and Pertarungan Bersenjata: Keris & Keris (2021) that recounted fierceness and nobleness. According to Firdaus, the fights represent a fight of internal conflicts against the betrayal of self. It is a direct reimagining of prefighting in the paintings The Duel I and II, which was visualised as the end of the fight.

For the most part, his paintings translated into an expansion of Malay folklore, deriving its moral values and re-evaluating old traditions/practices that seemed to characterise the Malay society at large. Firdaus’s style in introducing folklore feels almost like pure spectacle — his paintings illustrate a phenomenon in a film called ‘breaking the fourth wall’, described below:

The fourth wall is a conceptual barrier between those presenting some kind of communication and those receiving it. The term originated in the theatre, where it refers to the imaginary wall at the front of the stage separating the audience from the performers. [4]

According to Windmill Theatre Co., there are 10 elements of theatre: role and character, relationships, situation, voice, movement, focus, tension, space, time,

Still life with seven conditions

language, symbol, audience, mood and atmosphere[5]. Firdaus’s works fulfilled these elements to a tee; his paintings depicting Malay warriors, traditional women, and cultural attributes adorned and amplified certain qualities present in a theatre presentation. In the few portrayals of Malay traditional house interiors in his works, he embeds and arranged modern items which clashed vividly against the traditional, as exampled in Interior with Standing Female Figure (2022) and Seated Woman by The Rear Window (2022). Accordingly, Firdaus becomes the ‘property designer’ for these interiors; especially when such ‘designs’ are observable and appear in all of his paintings.

Despite the main theme for ASTAKA being Puteri Gunung Ledang from Sulalatus Salatin, Firdaus retained his interest in also subtly including renditions that have close relations to it. Uji Senjata (2021) and The Watchers I and II (2020) are instances from the film Puteri Gunung Ledang (1961) that ascend Hang Tuah’s character for its Malay warrior qualities; the fight scenes were made to describe a Malay warrior’s unmatched bravery and the readiness to defend their honours — be it for a loyal cause or simply for one’s peace of mind. Seeing the potential of these principled traits follows a need to set a precedent of thorough consideration by ‘structuring’ his paintings.

In a way, we are seeing the paintings of the much-revered story, Puteri Gunung Ledang, as a fantastical story rekindled through the lens of a contemporary Malay artist. At some point in absorbing the details of this abstracted world that Firdaus had concocted, we feel the pulse of its characters manipulated into breaking the wall of this imagined fairytale and into our perception. An alternative form of vision presenting a world that is separated by centuries of venerated oral tradition brought a sense of national pride to Firdaus who deemed such an appreciation should be elevated and celebrated, keeping in mind it is an art form in and of itself.

ASTAKA, from here onwards, is a venture into conceivable, yet unconventional impossibilities.

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malay_folklore

[2] Mohamad Kamal bin Abd. Aziz, Dr. Rahmah Bujang (2016). Kritikan Seni: Suatu

Tinjauan Terhadap Karya- Karya Mohamad Hoessein Enas Dan Syed Ahmad Jamal

Sebagai Seni Warisan Bangsa Dan Budaya Melayu. https://ir.uitm.edu.my/id/ eprint/53876/1/53876.pdf

[3] Artist’s statement.

[4] https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/fourth-wall

[5] Windmill Theatre Co. (2018). https://windmill.org.au/wp-content/ uploads/2018/09/Elements-of-Drama.pdf

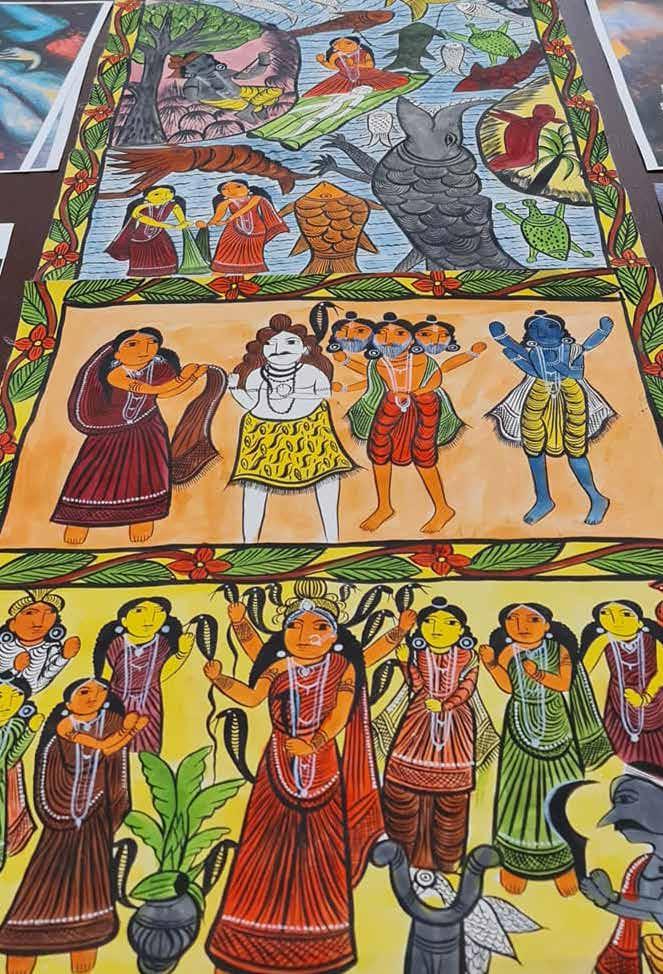

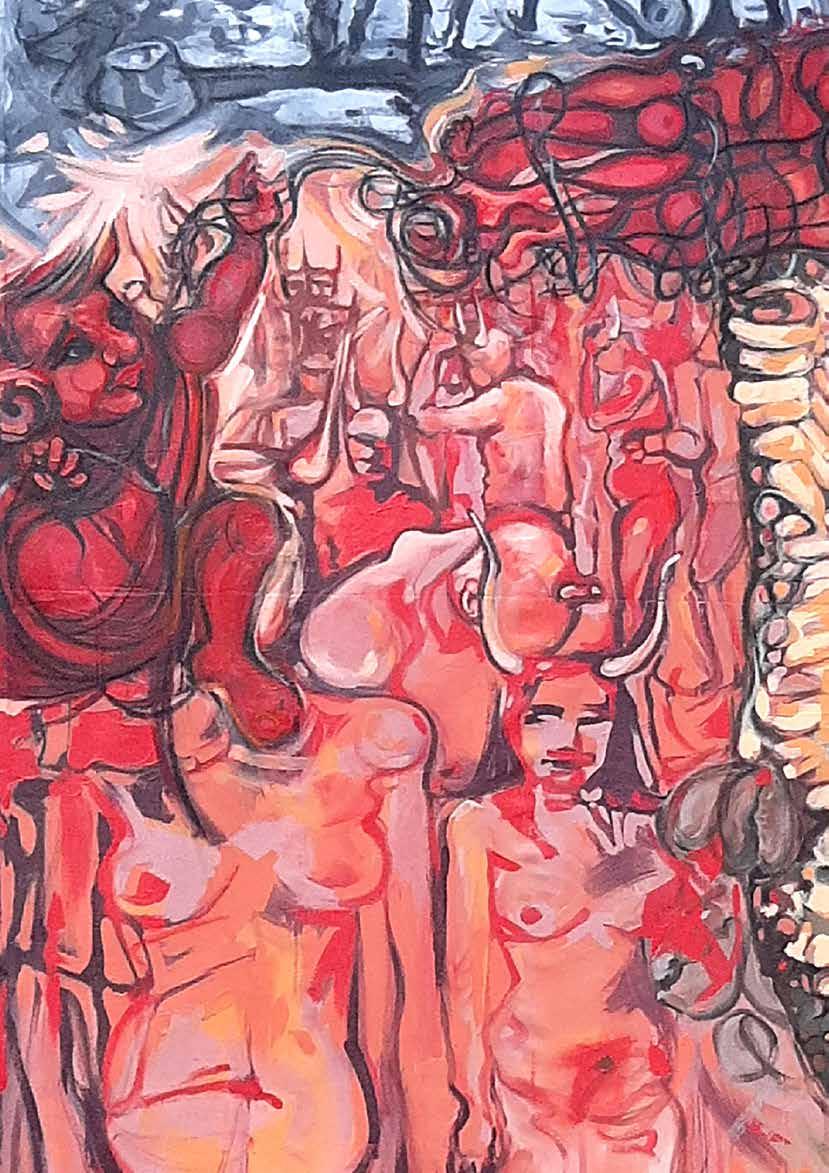

In November (2022), the Kolkata artist Papia Ghoshal held her solo Tantra exhibition ‘Tantra, the infinite,' in the gallery of the Nehru Centre. That centre is part and parcel of The High Commission of India, in London, and operates in accordance with the Indian Council for Cultural Relations [ICCR], established in 1950.

The Nehru Centre is within walking distance from the deeply spiritual London retreat of Hyde Park, originally bought by King Henry VIII from the Benedictine monks of Westminster Abbey. Across from that park, and down the road from the 18th century Grosvenor Chapel (church), the16th century building situated at West London’s South Audley Street, number eight (acquired by the Government of India in1946) is the de facto Indian cultural wing of the Nehru Centre, engendering displays, performances and screenings of Indian arts and cultures, established in 1992.

It comes as no surprise then that, amidst the innate spirituality of the area, the Indian artist/ poet/singer/actress/performer Papia Ghoshal (based in Prague [Czech Republic], London [UK], and Kolkata [India/Bengal]) should frequently choose to have her works, like ‘Gandhi the Practitioner’ which ultimately celebrates the spiritual in humanity, shown at the Nehru Centre, and in that area of London steeped in spirituality.

Over time, Ms Ghoshal has created a fresh ‘language’ with her works, some harness more figurative aspects, like ‘Tantric Practitioners’, some are reflective and enhance our understanding of rural and tribal Indian art, such as ‘Shavia Shaktis’, while Ms Ghoshal constantly

edges towards a deeper understanding of ‘the spiritual’ with ‘Tantra the Infinite’, ‘Shuya’ and Cosmic Energies’ all the time bringing her fascinated audience so much closer to the ecstatic with her insightful intimations of the ancient, the mystical, and eventually with Tantric abstraction reaching out to touch, and reflect, ours souls with mystic spiritual love with intimations and allusions of a Sufic/Baul tradition.

Within that aforementioned esteemed gallery, under the watchful eyes of exquisite busts representing Rabindranath Tagore and Sri Aurobindo, Papia Ghoshal’s artworks, such as her series ‘Tantra Trees’, dig deep into the sacred earth while simultaneously stretching into spiritual heavens fairly scintillated within the enraptured atmosphere of that cultural centre. There to witness her solo exhibition of vibrant, highly personal, yet significantly esoteric Tantric works of art were gathered a coterie of collectors, supporters, friends and art enthusiasts, close friends and art lovers, who were understandably present to be spellbound, intrigued and delighted by Ms Ghoshal’s Tantric works on show. The stage (literally) had been set to welcome artist Papia Ghoshal (aka Papia Das Baul, and a regular at the Centre) to present her solo exhibition of spiritual Tantric paintings, significances and symbology.

Ms Ghoshal, in her artworks, shuns Western nomenclatures such as ‘Modern’ or Contemporary’ art in favour of reaching out past both and forging ahead with Baul inspired sufic Tantra-based visualisations, seen in this solo exhibition as part of the Nehru Centre’s Tantra Festival.

Later, in that Nehru Centre Tantra Festival, there was a second exhibition of artworks held within the two glorious white-coloured (Bharaiv and the Sarang) exhibition halls, which is where Papia Ghoshal curated the group exhibition, titled ‘De-constructing Tantra’.

This fresh exhibition included works by Papia Ghoshal herself, as well as art works by Richard Bagulley; Martin A Bradley; Bijon Chowdhury; Jatin Das; Milada Ditrichova; Lee Johnson; ‘Radha Khrishna’ by Prokash Karmakar; Pablo Khaled; Robin Hydar Khanr; Melvyn King; Robert Lassenius; Jan Mayer; Millie Basu Roy; Assem Al Sabban; Sudeep Ranjan Sarkar; Jan Strup and last but not least one glorious ‘Tubist’ work by Helmut Thoma (1977).

The wall works, in the first white hall, were accompanied by long antique banquet tables (fulfilling the role of display cases within that ‘safe’ and exclusive atmosphere). Those rich, polished, brown, tables displayed a variety of artworks, including delicately coloured Indian scroll works.

In the second hall, other scrolls hung from the walls and were accompanied by a bronze ‘Dancing Shiva’, wall hanging paintings and window aggregations of

Floating dreams

smaller artworks. The whole, respectful of the antiquity of the building itself, was reminiscent of those intriguing private collections, or the small museums which London is famous for, in the intimacy of collection brought about by the juxtapositions and placings of the very varied works of art connected to Tantra, in it’s broadest sense.

During the Tantra Festival there were also performances of Papia Ghoshal’s Baul music, and one fascinating Tantra documentary ‘The Story of Tantra’ from The Czech Republic’s director Viliam Poltikovič, featuring the artist Papia Ghoshal.

Ed

Ed

“Perhaps it might be said rightly that there are three times: a time present of things past; a time present of things present; and a time present of things future. For these three do coexist somehow in the soul, for otherwise I could not see them. The time present of things past is memory; the time present of things present is direct experience; the time present of things future is expectation.

Confessions, St. Augustine, Book 11, Chapter 20 ,

The stunning beauty of history is not that it is fixed, but that it is fugitive.

Herodotus, (a Greek from what is now Turkey), wrote ‘Histories’ to explain the Greek/Persian wars and was known, by Cicero, as the “father of history”. The much later ‘historian’ Plutarch, however, with his “On the Malice of Herodotus” in ‘Moralia’, named Herodotus the “father of lies”, for distorting history.

Histories are collections of perceptions which alter dependant on a host of reasons, culture, religious/political

belief systems, social perceptions etc. etc. etc.. In one view of history the fixed fact which defined an age becomes dislodged when fresh information is introduced. Time frames shift. New findings adjust accepted knowledge. Every ‘confirmed fact’ is nuanced, tentative, a temporary sign rather than a concrete actuality where classifications become misleading, as demonstrated in the notions of memory and time in Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time’.

Henri Bergson (in ‘Matter and Memory’ 1991) on the other hand, suggested

“There is no perception which is not full of memories. With the immediate and present data of our senses, we mingle a thousand details out of our past experience. In most cases these memories supplant our natural perceptions of which we then retain only a few hints, thus using them merely as ‘signs’ that recall to us former images.”

In the exhibition ‘Memories of History’, two prominent artists, Milan (Italy) born Giovanni Cerri and Hangshou

(China) born Luo Qi, work within the twin fugitive notions of ‘history’ and ‘memory’. One, Luo Qi, works in such a way that he references the past to (re)create imagery which has much in common with asemic (that is faux) writing. The other, Giovanni Cerri, imagines images of a proposed past, projected into what appears to be a dystopian future. The joint exhibition becomes a testament to the malleability of the notion of history.

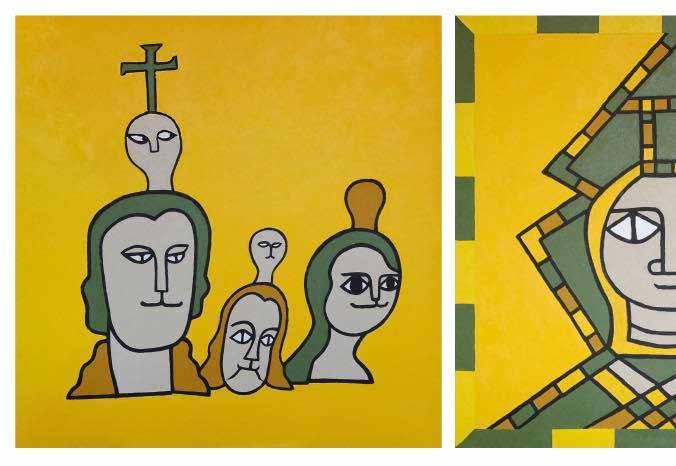

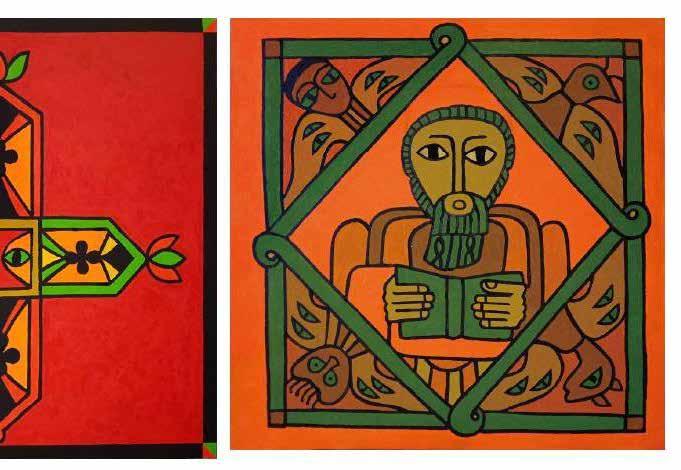

Luo Qi takes his visual clues from the minutiae of European Medieval manuscripts. He delights in those frequently overlooked, but nevertheless fascinating, marginalia and illustrations.

It seems only natural that Luo Qi should begin to look at Medieval manuscripts and begin to see the possibilities of making them his own, with his ‘Notes’ series. To do with, and for, them what he has been doing with Chinese calligraphy (writing) to produce Calligraphyism, which is an extension of the notion of asemic writing, or marks which appears to be writing, but are not. With his new quest Luo Qi has turned his attention to Medieval images. They are taken out of context, enlarged, re-coloured and reinterpreted in his customary flatness.

Visually, this new enterprise has commonalities with Luo Qi’s earlier ‘Calligraphyism’, and his fresh look at Pop Art. Now, the subject is not the reinterpreted Chinese character/logogram, but a fresh look at Medieval manuscript imagery with images like ‘Note 7’ (2023), which resembles tapestries such as the French ‘Bayeux Tapestry’(discovered in 1476).

This fresh look, like his ‘Calligraphyism’, makes us see again the original material, this time with unfettered eyes. It is the recognition of the surreal\Dadaist act which had informed Pop Art. It is Méret Oppenheim’s ‘Object (Le Déjeuner en fourrure’, 1936) fur cup and saucer, and Man Ray’s ‘Cadeau’ (1921), the flatiron embedded with sharp nails. Neither object is suitable for its original purpose, and in that negation makes us recall their historical utility value.

Luo Qi’s canvas ‘Note 9’ is a play on green and red. In a bottom right square a monk in red is painted on a green background. An accumulation of symbols ties that painting with its partner canvas ‘Note 8’, presenting an unwavering ‘modern’ painting (across two canvases) which reminds the viewer of medieval imagery. Another series, Note 10,11,12 (2023), projecting Kandinsky yellow, shows a human figure with a head appendage reminiscent of Medieval pictures of bishops. Other canvases which bring to mind ‘The Lindisfarne Gospels’ (c. 700, found at Lindisfarne Priory on Lindisfarne, Holy Island).

Milanese artist Giovanni Cerri gives us dramatic urban and seemingly dystopian canvases of not just an end of empire, but an end of the world scenario. In his largest works, we could imagine that they are backdrops to some chthonian opera, played out by sombrely dressed opera singers mournfully decrying the rapture.

We can further imagine Tomaso Albionai’s Adagio en sol menor, in G minor playing as we observe the mournful colouration, bold expressive brush strokes and the necessary drips of paint running down bold canvases which all add to the careful creation of grim warnings of the future climate change events which Giovanni Cerri’s canvases appear to herald.

For instance, in ‘Climate change, Roma (Colosseo)’ Giovanni Cerri renders an image of the Rome Colosseum. That structure was built nearly two thousand years ago and has remained a symbol of Rome and its empire. In Cerri’s vision, the Colosseum is flooded. ‘Climate change, Roma (Colosseo)’ is at once a reminder of the faded splendour of the ancient world, its longevity, but also a bleak image of an ‘end of times, and a caution for future generations as the ruins are all that is seen in a barren landscape. In Cerri’s more recent work such as ‘Paesaggio sommerso’ (submerged landscape), the larger canvas, with its image of swans (Zeus?), which may be seen as new growth or the beginning of a new golden age, we see man’s centuries-old

urban landscapes becoming reclaimed by nature as our planet heals from the wound which was man.

What at first glance appears to be doom ridden and dystopian, may be a rejuvenation as the planet heals itself. Like the Tao’s ‘Yin Yang’, where there is a speck of black in the white, and a speck of white in the black, Cerri observes that what has ruined man has ultimately uplifted nature to its rightful place, not back to idealisation of Thomas Moore’s 16th century satire ‘Utopia’ (which is a man-made social ideal), but to a (tropical) earthly paradise (with flamingoes symbolising balance and harmony) which begins the new ‘Garden of Eden’ as seen within Cerri’s ’Paesaggio sommerso’, the smaller canvas.

At first glance Giovanni Cerri and Luo Qi’s paintings could not be more different. The presented images are, however, tied together by notions of history, or historicity. Cerri looks forward to what initially appears to be ideas of destroyed JG Ballard (Drowned World) dystopias, while Luo Qi looks back to Medieval times and reimagines the imagery there. In choice of subject matter, in method of execution and style chosen there are no similarities, however both artists are referencing notions of time, and creating or invoking notions of the past through memory, its quirks and its misinterpretations.

EdClimate change, Roma (Colosseo)

Where my poems are painted

“Taking your palette, its wing holds a bullet-hole, you summon the light that revives the olive-tree. Broad light of Minerva, builder of scaffolding, with no room for dream and its inexact flower.”

“

Neo-surrealism, perhaps, should not be called a movement per se, simply because the movement usually has a group of like-minded individuals united by common objectives. Some of them even have originators. Neo-surrealism is instead a stream. It has no founder or a philosophical platform. Some artists joined it earlier, others later even without apparent awareness of their affiliation. Although different groups of artists from diverse countries sometimes form collectives.”

2George Grie, 2009In Iberian lands lays richly poetic Spain. Lands where the ‘sur-real’ had once danced hand in hand with the ‘Nouveau’. Parental lands delighting in Aztec chocolate and where family cathedrals have outgrown their meticulous ‘New’ designers. They are serendipitous lands where poetic flowers grow and flamboyant visionary creators weave their visions spontaneously into new realities.

Ancestral blood of surreally creative España swims in the artist Rafael Serrano‘s poetic veins. His Spanish parents arrived on shores of the ‘New World’ from French/Spanish/African infused

Cuba. Since the age of twelve Serrano has lived in the ‘City of Angels’ (El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula, or "The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels of Porciúncula) aka Los Angeles but, more poignantly, the City of Flowers (Ciudad de las Flores). Los Angeles. Its official flower being the ‘Bird of Paradise’ which is, coincidently, also grown in the parks of Catalonia’s Barcelona.

The poet/artist Serrano is, by his own admission, a neo-surrealist. Neo Surrealism has grown from the shock and awe of the early twentieth century ’Dada’’ and its far reaching offspring, Andre Breton’s Surrealism. In his first ‘Manifesto of Surrealism’ (1924) Breton explains...

“Surrealism is the "invisible ray" which will one day enable us to win out over our opponents. "You are no longer trembling, carcass." This summer the roses are blue; the wood is of glass. The earth, draped in its verdant cloak, makes as little impression upon me as a ghost. It is living and ceasing to live which are imaginary solutions. Existence is elsewhere.”

3André Breton Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)

Rafael Serrano’s works perfectly engender that Bretonian Surrealist sense, not of shock but with intrigue. With Serrano, Breton’s “This summer the roses are blue; the wood is of glass” becomes a visual reality.

Let summer wipe our tears

To quote Breton again

“Modern poetry does not use the unconscious for its own sake. It is a real advance toward self-knowledge and the knowledge of everything within us that differs from the self-image we once felt was justified.”

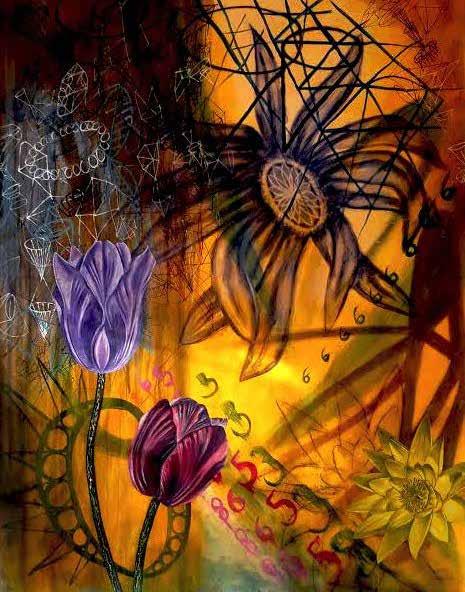

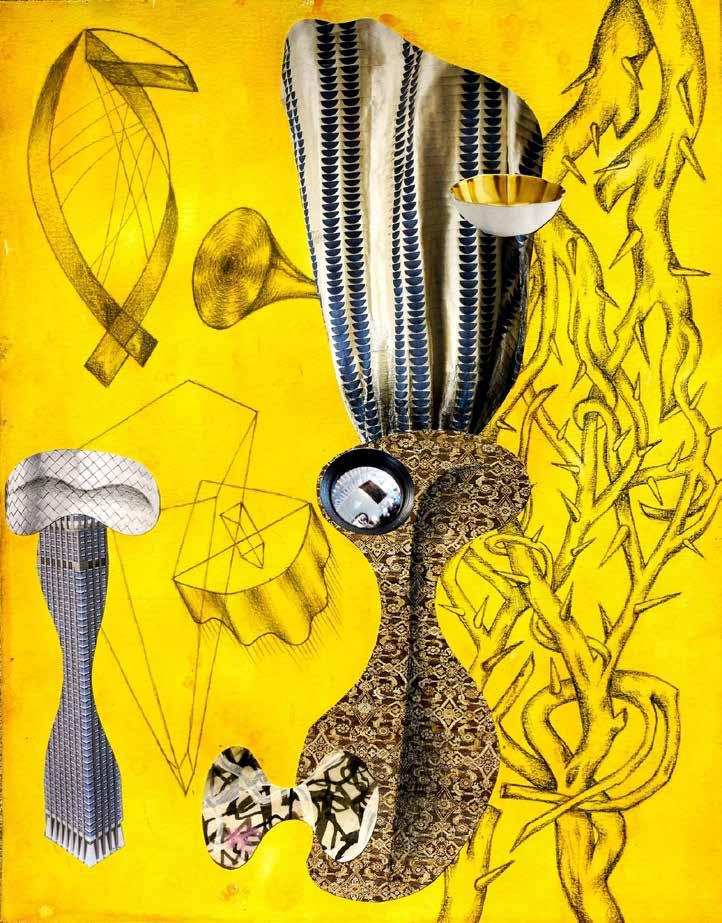

4André Breton Œuvres 421).Serrano is an individual who has become impassioned to epitomise seemingly organically surreal images. Using a mixture of paint, collage, photography and photographic manipulation he presents his subconscious to an intrigued audience. This can be witnessed in one of his more floral series. These are works including ‘Exile from paradise’ (a graphic portrait of a dark flower, on the right of the image, potentially from the ‘liliaceae’ family, its petals sharp as if drenched in blood). Then there is ’Midnight dance of erotic fantasies’ (the same lily flower, on the left side on the image, dark in tone surrounded with ethereal blooms and organic, surreal, vegetation) and ‘Let Summer wipe our tears’ (with the flower image back on the right, with a predominate air of yellow and blue, as if it were summer, but a dark, David Lynch, murderous, summer.

Serrano mesmerises. He draws his audience into his dream-like alternate reality. He portrays a subconscious ‘City of Flowers’ enwrapped in symbolisms, for he is, after all, a poet, a man of metaphorical symbols as well as an artist. The French philosopher Georges Bataille, an early Surrealist, had mentioned

“…if one says that flowers are beautiful, it is because they seem to conform to what must be, in other words they represent, as flowers, the human ideal.”

5Georges Bataille ,Visions of Excess Selected WritingsAs a contemporary creator, Serrano proffers vibrantly heady and evocative organically surreal images. His work is lyrically poetic and reminiscent of Spanish modernity, a time

which had brewed Grenadian Spanish poet Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca (Federico García Lorca) epitomising ‘Modernismo’. One glance at Rafael Serrano’s work yields the fantasy which is not fantasy of Joan Miró, the depths of Pablo Picasso, the eroticism of Salvador Dali and minutiae of Anton Gaudi. And, at times, Serrano’s works portray a deliciously Buñuel noir. Having said that, Serrano’s surrealist homage paintings are effectively ‘angeleño’ dreams. They are a product of the artist’s fascination with surrealism, his heritage and the land he has grown in (Los Angeles).

Los Angeles is a land primed by Surrealism. In 1934 Lorser Feitelson and Helen Lundeberg began what became know as ‘Post-Surrealism’. Later we are informed (by Berit Potter Assistant Professor in the Department of Art at Humboldt State University) That

“The first survey exhibition of surrealism shown in the Bay Area, Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, appeared at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, or SFMOMA (then the San Francisco Museum of Art), in August 1937.”

6 Berit PotterThree years later, in 1940, Los Angeles gave shelter to the surreal photographer Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky in American Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1890). He moved to Paris (France) in 1921. Like many artists, Ray escaped Nazi occupied Paris and sojourned in Los Angeles from 1940 to 1951. In 2016, the artist Max Maslansky organised the exhibition ‘Tinseltown in the Rain: The Surrealist Diaspora in Los Angeles 1935–69’, at the Los Angeles gallery Richard Telles Fine Art, reminding us of the importance of surrealism to Los Angeles and, ultimately, to our subject Rafael Serrano.

Freudian dreams and their landscapes are frequent subjects in Surrealist works. The

projection of interior workings of the mind, its connections to mysticism and magic have continued to interest proponents of Surrealism. André Breton had mentioned that

“We are still living under the reign of logic... Under the pretence of civilisation and progress, we have managed to banish from the mind everything that may rightly or wrongly be termed superstition, or fancy; forbidden is any kind of search for truth which is not in conformance with accepted practices… A part of our mental world has been brought back to light. ... Freud very rightly brought his critical faculties to bear upon the dream.”

7 André Breton Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)Dream is where we find Serrano’s imagery. His waking dreams hold echoes of the enigmatic Cuban artist Wifredo Óscar de la Concepción Lam y Castilla (aka Wifredo Lam, 1902, - 1978), who, like Serrano, had a Spanish mother and had lived in Cuba. Where Lam fused surrealism with the natural Cuban landscape and disparate ancestral spiritual beliefs, Serrano has created his very own angeleño dreamscapes. He presents his dream entanglements to us, organic based and absorbing, beguiling us, drawing us into his magic-tinged world with creations such as ‘Lagoon of unrepentant memories plus other living things’ (a truly surreal textural admixture of photographed three-dimensional, drawn and painted fantasy shapes which, to this writer, are reminiscent both of Bruno Bozzetto’s. 1976 animation ‘Allegro non troppo, and Joan Miró’s dream-like creations).

When Serrano gives us flowers to pontificate on, his works are not the subtly erotic floralscapes of Georgia O’Keeffe, or the ‘Vodou spirit’ infused images of a Lam canvas, but other, intriguing, worlds entirely. Serrano’s are worlds like ‘Lagoon of unrepentant memories plus other living things’, ‘The pre-existence of the gods’ and ‘Apotheosis’ which subsume us into curious oceans we must navigate, but also must

heed not to collide with semi-solid objectified symbolic images which the artist, challengingly projects towards us. Serrano is a modern day Homer telling tales of his own ‘Odysseus’, or maybe Serrano is in the guise of André (Paul Guillaume) Gide telling stories of ‘Urien’, braving uncharted waters of the mind/soul.

In his images Rafael Serrano becomes the ‘Sorcerer Supreme’. He conjures, manipulates dream-like subconscious and vividly magical worlds. We, his audience, are invited to delve into his works through a Cocteau-like liquid mirror which whisks us not to Orphée’s ‘Underworld’, but away onto visually metaphysical voyages. In more modern parlance, when confronted with Serrano’s work, we feel as though we are immersed into a peyote induced 1960s Steve Ditko ‘Dr Strange’ comic-book fantasy where, beyond the laws of physics and in alternate dimensions, lives Dormammu et al. Such are the acute mysticisms and ‘magics’ pervading Serrano’s work, floral or otherwise.

Surrealist, Post-Surrealist or Neo-Surrealist; the Los Angeles artist Rafael Serrano delights his audiences with his unique Hispanic Los Angeleno take on the world. He presents worlds in which we willingly suspend disbelief. He is a poetic tale-teller of phantasms and fantasies, but also one who carries forward DNA entrapped in surrealisms of place. That place is a place of the angels, Los Angeles, steeped in surrealism. Ed

1Federico García Lorca

‘Ode to Salvador Dali’ (extract)

“Al coger tu paleta, con un tiro en un ala, pides la luz que anima la copa del olivo. Ancha luz de Minerva, constructora de andamios, donde no cabe el seuño ni su flora inexacta.”

2 George Grie. May 14, 2009 (Rus) - ‘Манифест Нео-сюрреалиста’ (What is Neo surrealism), http://neosurrealismart.com/archive-works/ What-is-Neosurrealism-the-Neo-Surrealist-Manifesto.htm

3André Breton ‘Manifestoes of Surrealism’ (1924).Trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1969. Print

4 André Breton ‘Œuvres complètes’. 4 vols. Paris: Gallimard, 1988–99. Print. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

“La poésie moderne ne pratique pas l’inconscient pour l’inconscient. Elle est une véritable marche vers la connaissance de soi, à la connaissance de tout ce qui en nous diffère de l’idée que nous nous croyions fondés à entretenir de nous-mêmes […]”

5 Georges Bataille ,’Visions of Excess Selected Writings, 1927-1939’, Edited and with an Introduction by Allan Stoekl Translated by Allan Stoekl, with Carl R. Lovitt and Donald M. Leslie, Jr.

6 Berit Potter,“Gathered Another Way”: Early Surrealist Exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, in Vol. 14, 2018, Dada and Surrealism: Transatlantic Aliens on American shores 1914 - 1945 (17/26)

7 André Breton ‘Manifesto of Surrealism’ (1924) Op Cit

Indian artist Arjun Das is from the Giridih district of Jharkhand, and now a resident of Kolkata. He works with thrown-away materials he has collected from the city’s streets . For example, a discarded wooden board from a lorry is transformed into one busy street of Kolkata known as Bara Bazar. As well as wood sculptures, he also uses metal, stone, coal, terracotta roof tiles, and asphalt in his works, bringing to mind the everyday reality of the city’s workers, whom he is keen to represent in that way.

It was quite amazing, or should I say surreal.

The bus started late. It was delayed getting into town by traffic snarled up at roadworks. I missed my train.

Now Colchester has two rail stations. Where the bus deposited me in town, was at what suffices as a bus station (by the side of the road with copious bus stops). The bus behind was going to the second rail (main) station. I hoped on. Long story short, I arrived at the second rail station in time to catch a train which had been delayed by problems on the track. So, good news for me.

I arrived in London on time.

London was experiencing yet more mayhem on the 'Tube' (underground system). I ended up going to my destination (High Street Kensington) via a circuitous route which enabled me to use the new Elizabeth Line, and what a sheer joy that was.

My curious app, which supposedly leads me to wherever I ask it too, bluffed me. I asked it to guide to from the High Street Kensington tube station (which just happens to be in the High Street Kensington) to the Design Museum. Having walked some distance along that High Street, I stopped and checked the app. It said that I had another 5 minutes walking time to reach my destination. I sighed, then looked around me. Across the road was a large billboard proclaiming 'Objects of Desire' The Design Museum and, lo and behold, it was there, opposite from where I stood. My app was still telling me that I had five minutes yet to walk. I closed the app and walked across the road. So all's well that ends well.

Ps I saw Nick Cave (minus Bad Seeds) brush past as he popped into a shop on Kensington High Street. How surreal is that!

Ed

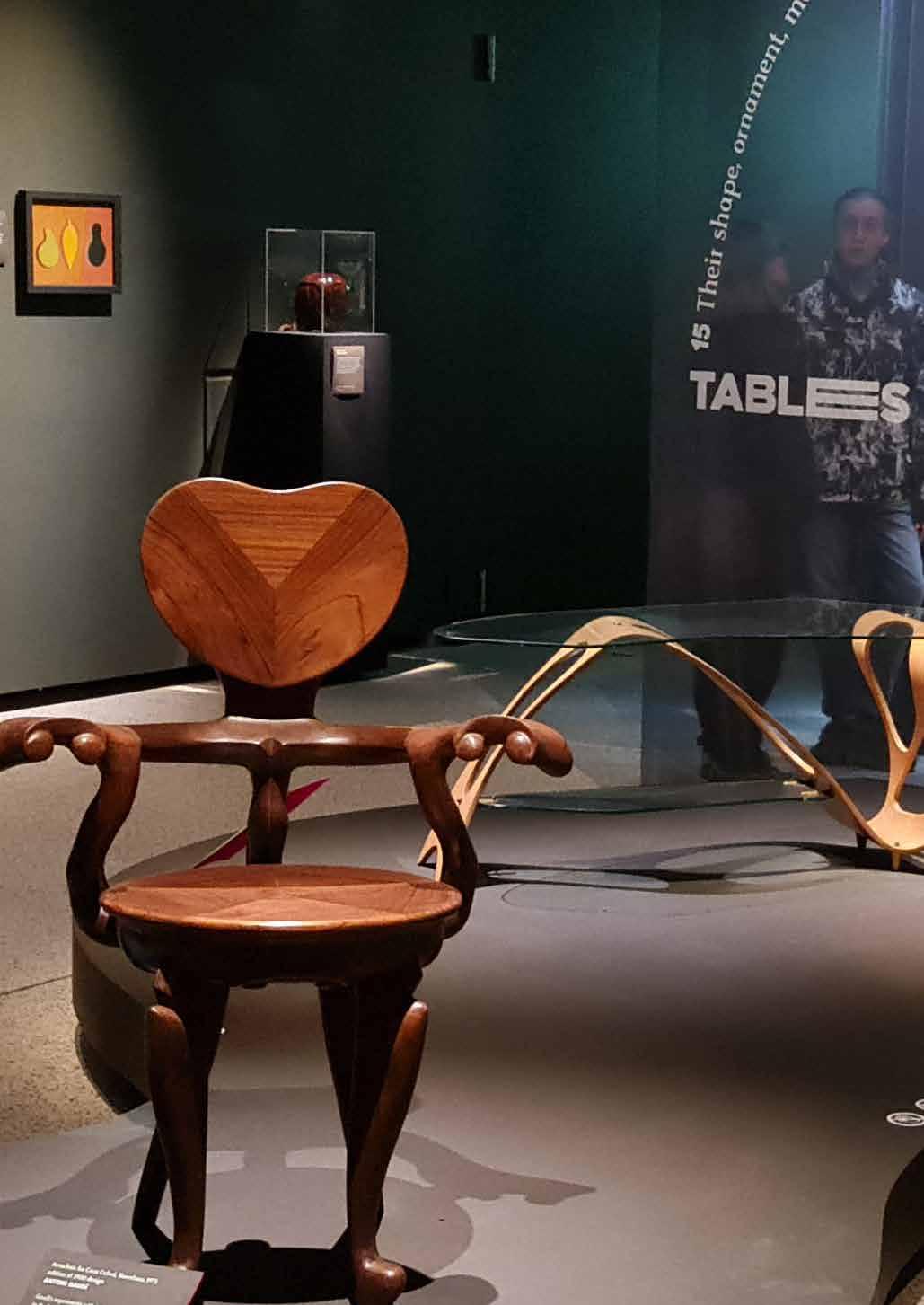

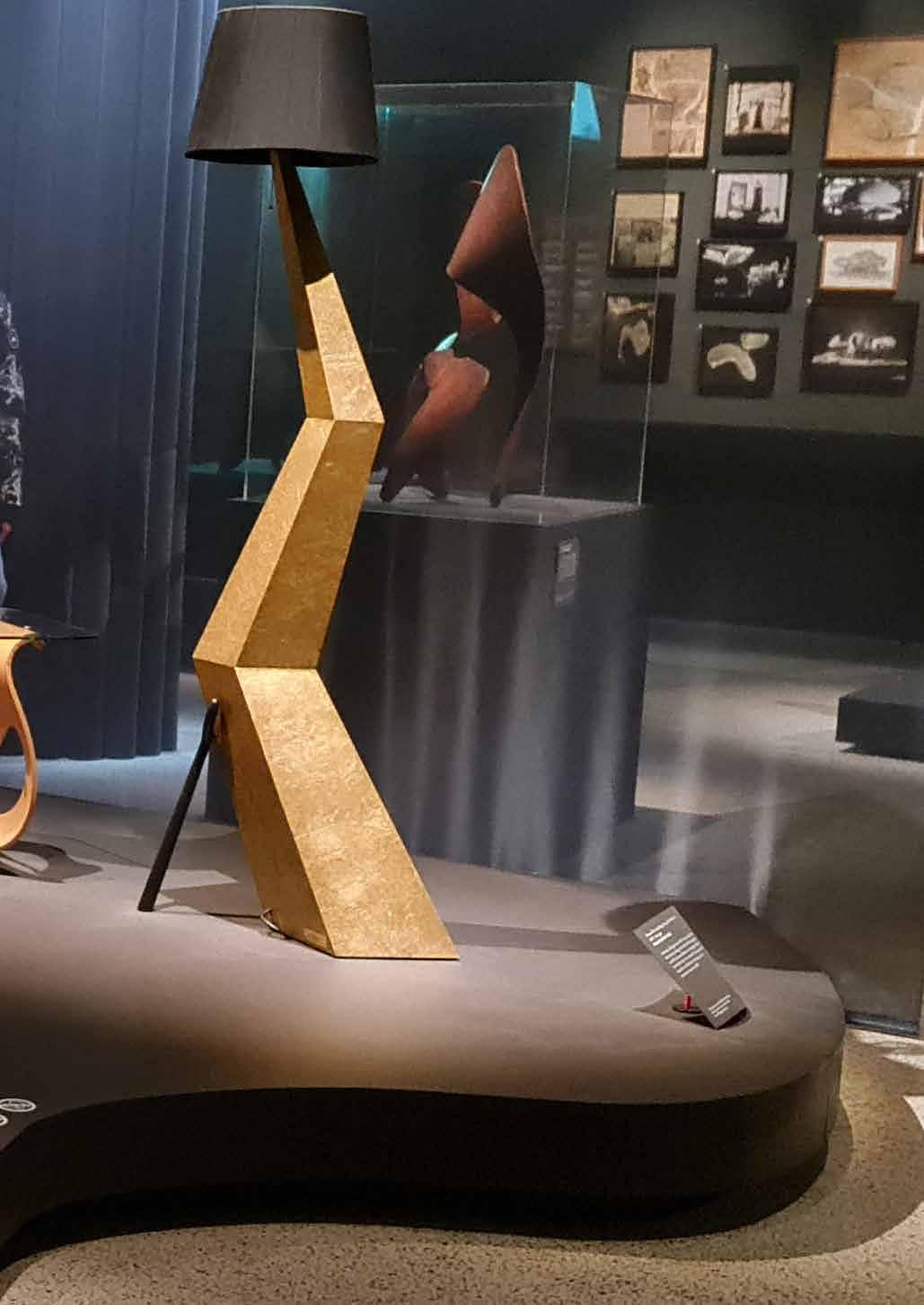

Head of Invention by Eduardo Paolozzi, Design Museum, London

Head of Invention by Eduardo Paolozzi, Design Museum, London

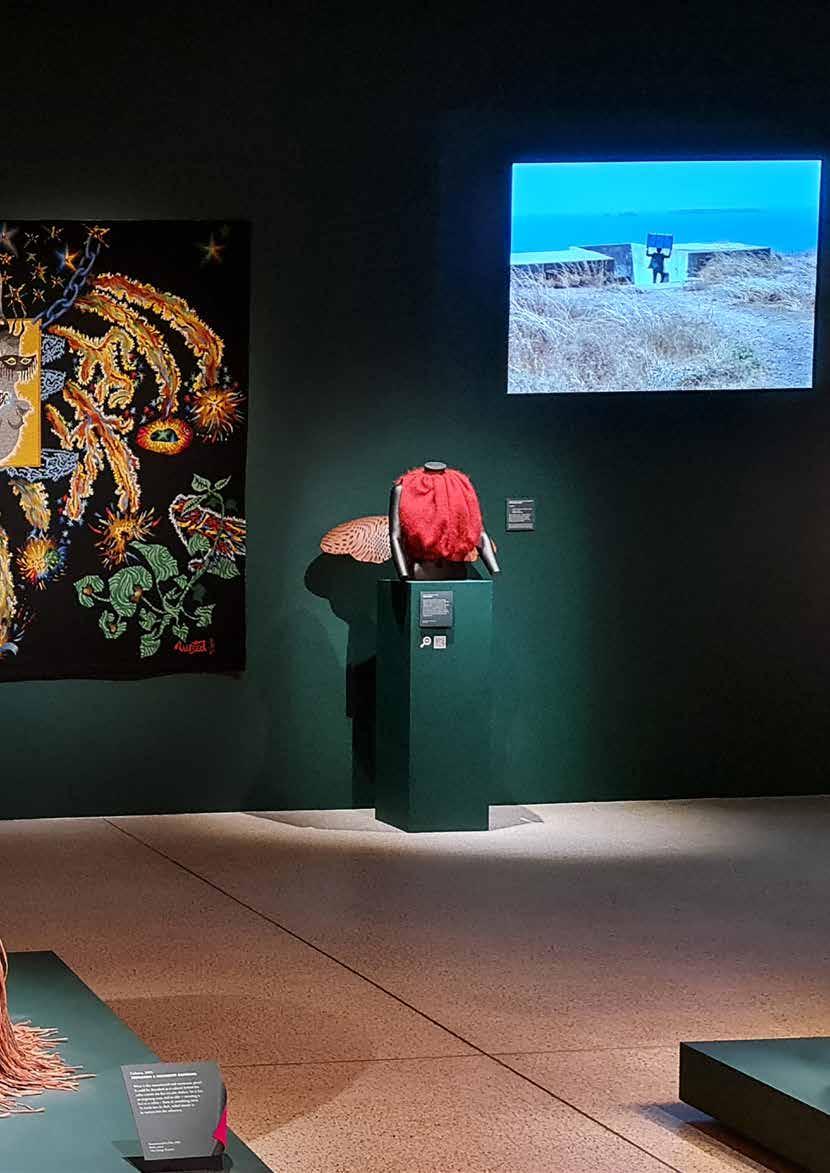

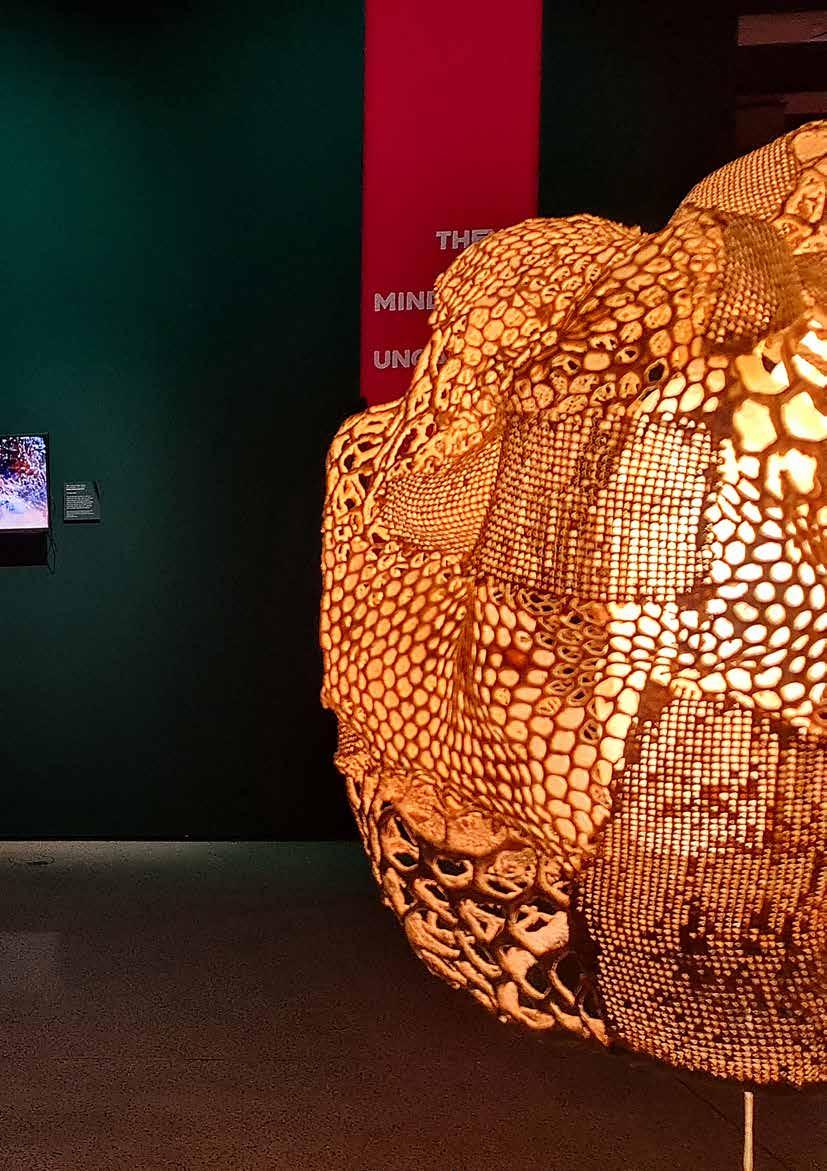

Installation view of ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 , The Design Museum, London

Installation view of ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 , The Design Museum, London

Installation view of ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 , The Design Museum, London

Installation view of ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 , The Design Museum, London

Installation view of ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 , The Design Museum, London

Installation view of ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 , The Design Museum, London

Installation view of ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 , The Design Museum, London

Installation view of ‘Objects of Desire: Surrealism and Design 1924 , The Design Museum, London

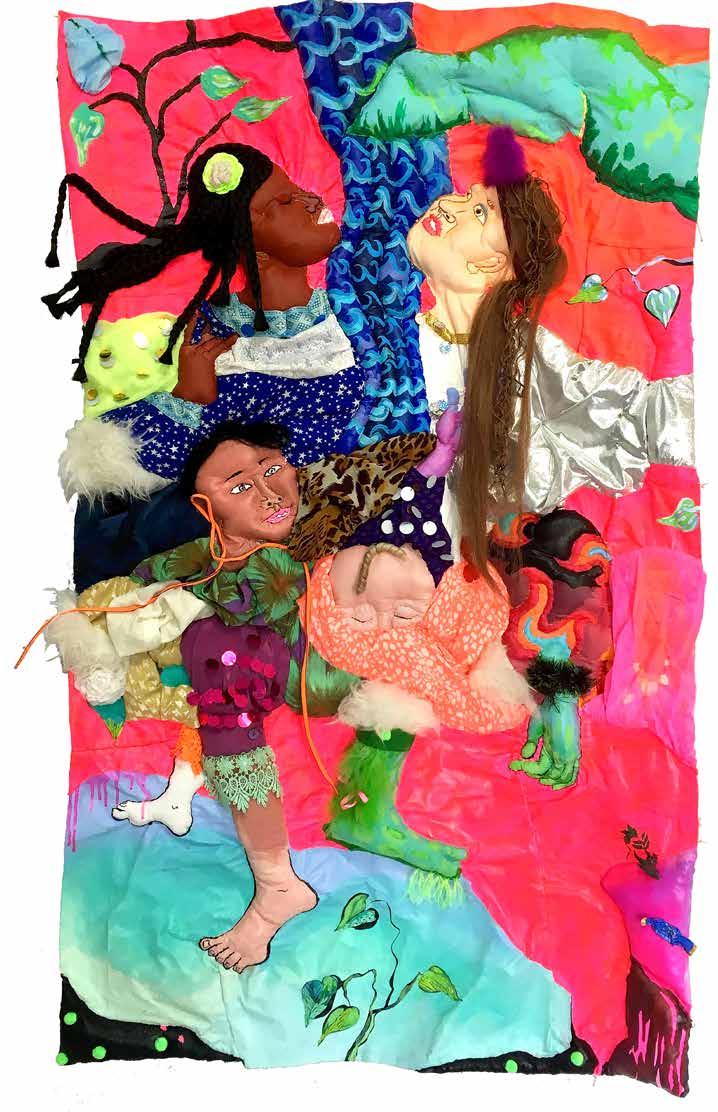

Avilla Damar , Quarantine Diaries–Volition

Avilla Damar , Quarantine Diaries–Volition

Selima Quader Chowdhury

Selima Quader Chowdhury

The 19th Asian Art Biennale was held in Dhaka, Bangladesh, between the 8th of December 2022 and the 13th of January 2023. The event featured paintings, prints, photographs, sculptures, installations, new media and performance art. On display were 649 artworks by 493 artists from 114 countries, including Bangladesh. Art from different cultures helps foster a sense of connectedness and cultural diffusion, and through the Asian Art Biennale many foreign influences have found their way into the contemporary art scene of Bangladesh, while artists from abroad have gained exposure to Bangladesh’s own cultural traditions. The theme of this year’s exhibition was Home and Displacement. Some migrants move from one place to another for a better life, for better economic opportunities, to join family members or to study, while others are forced to migrate to escape conflict, persecution or human rights violations, the adverse effects of climate change, natural disasters or other environmental factors. The 19th Asian Art Biennale sheds light on how artists respond to the trauma and agony of the displacement of migrants.