Lotus

Brandon Ritom

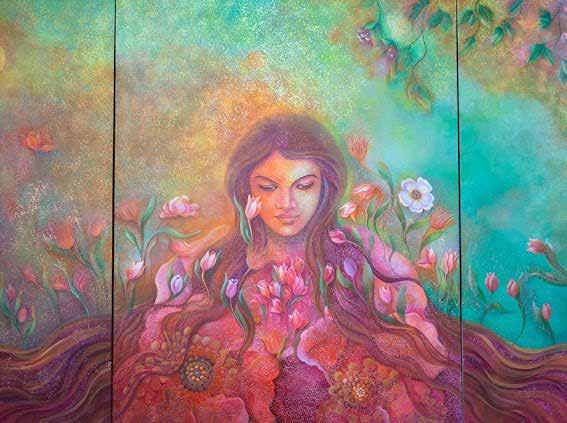

Vasanthi Naidu

Tamali Dasgupta

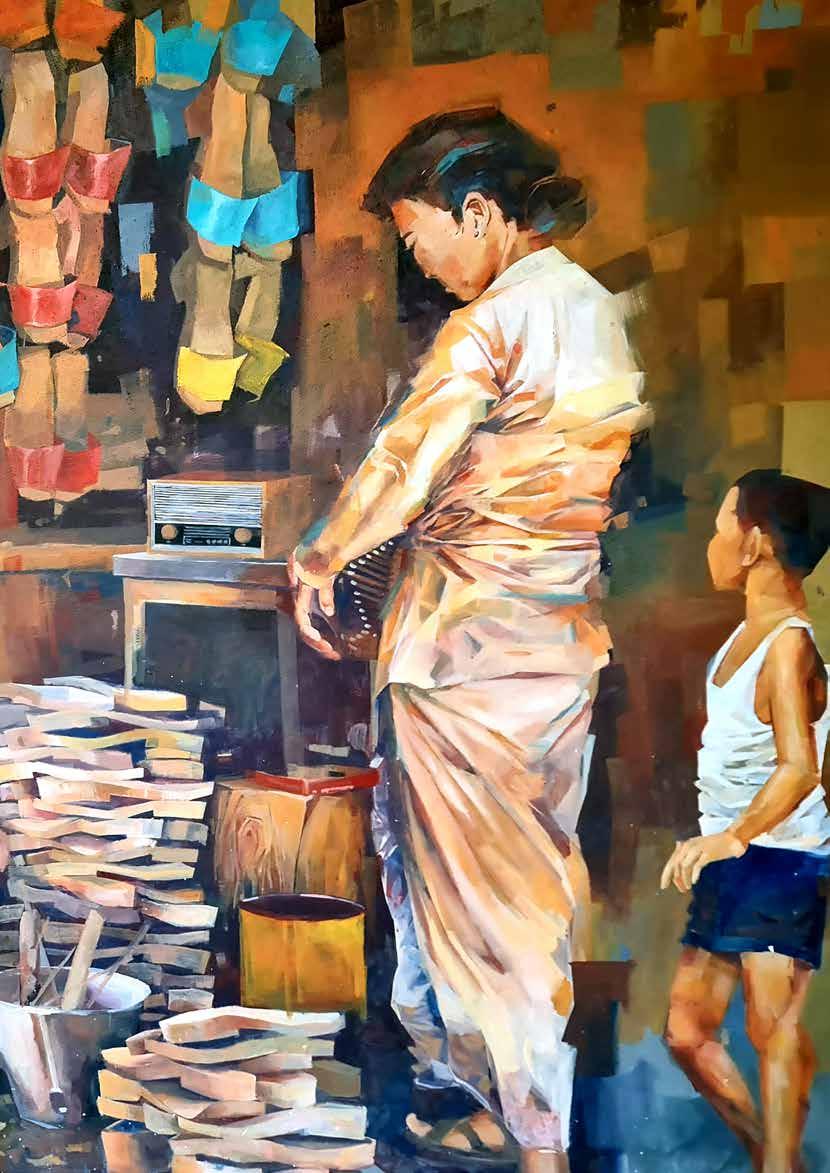

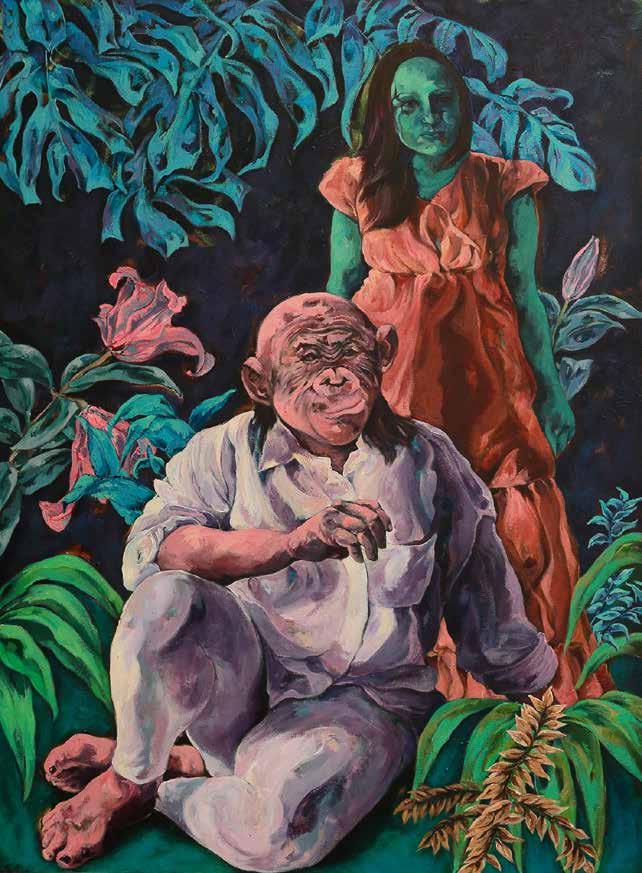

Tuan Vu

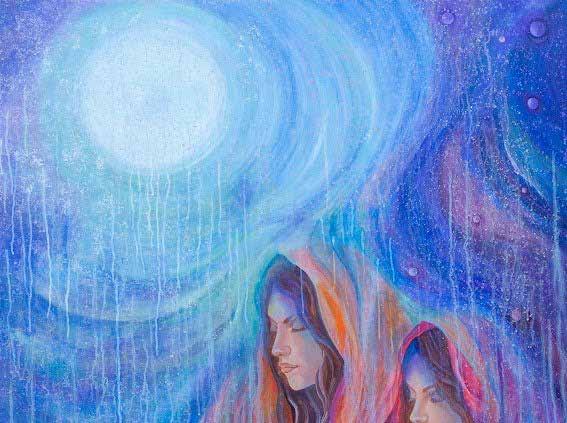

Farazeh Syed

Joy Ng Mei Lok

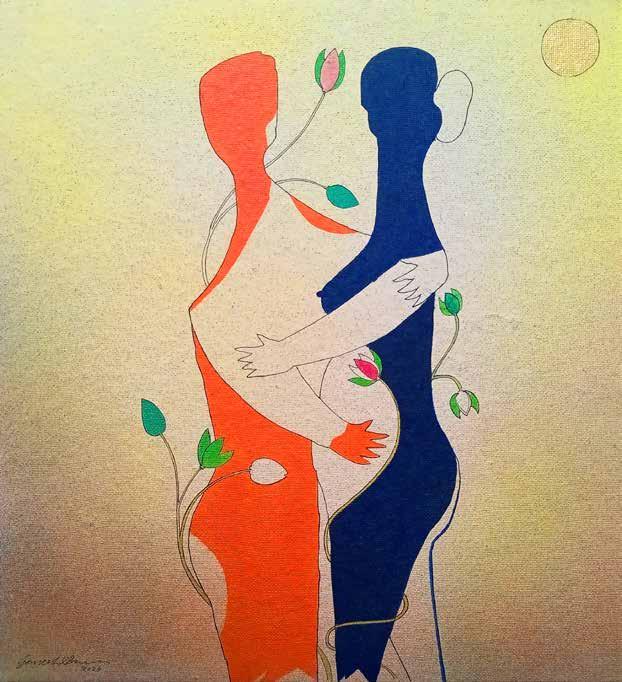

Francoise Issaly

Pilar Viviente

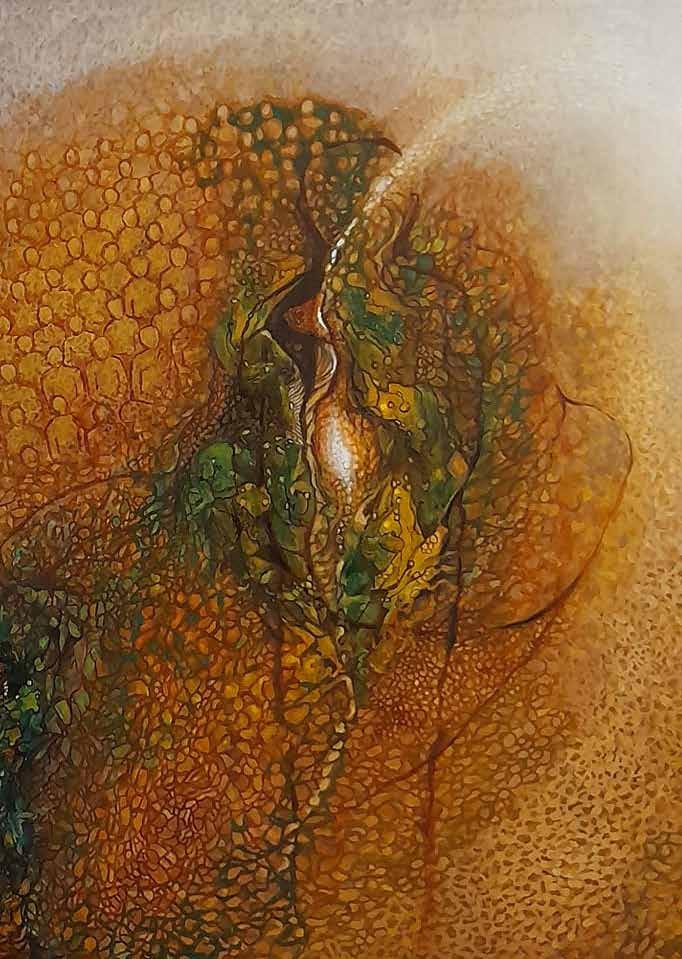

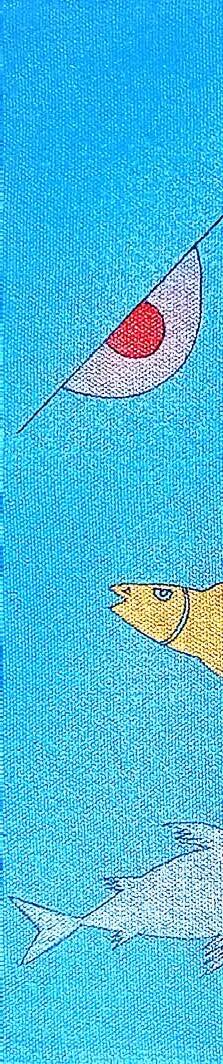

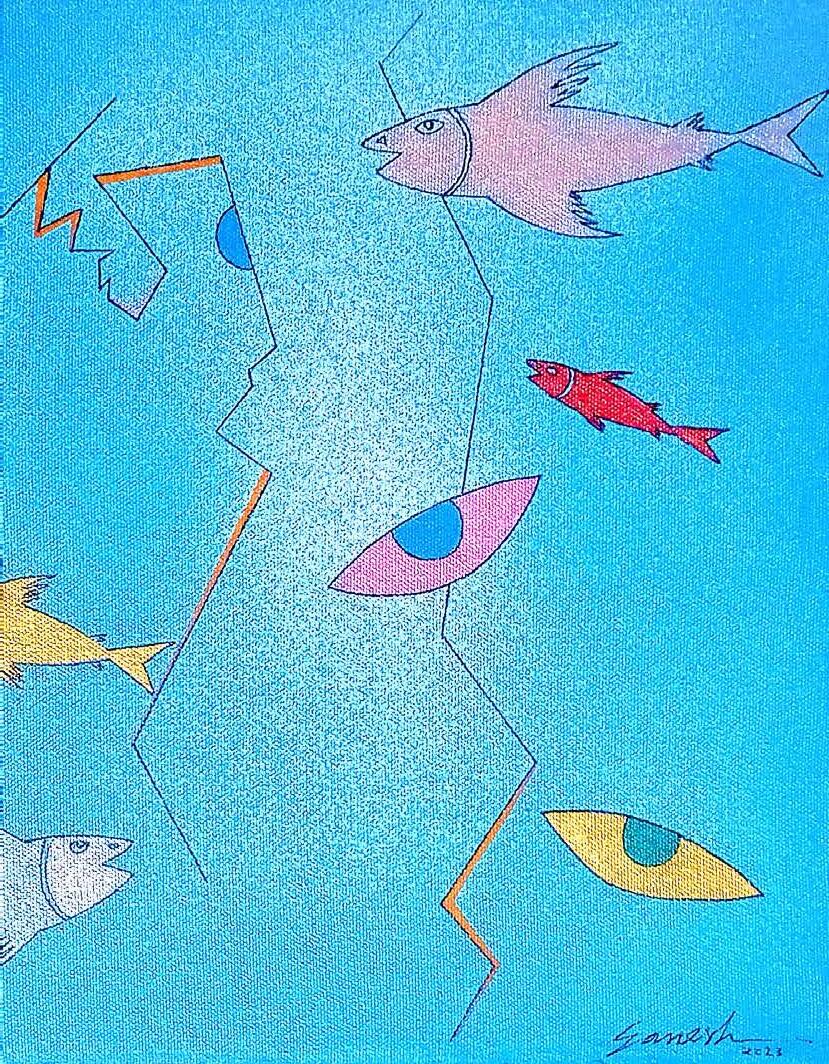

Ganesh Chandra Basu

Brandon Ritom

Vasanthi Naidu

Tamali Dasgupta

Tuan Vu

Farazeh Syed

Joy Ng Mei Lok

Francoise Issaly

Pilar Viviente

Ganesh Chandra Basu

Image © by Martin Bradley

Image © by Martin Bradley

A quick word Editor’s comments

p32

Brandon Ritom

Hand taping, Sarawak tattooing

p42

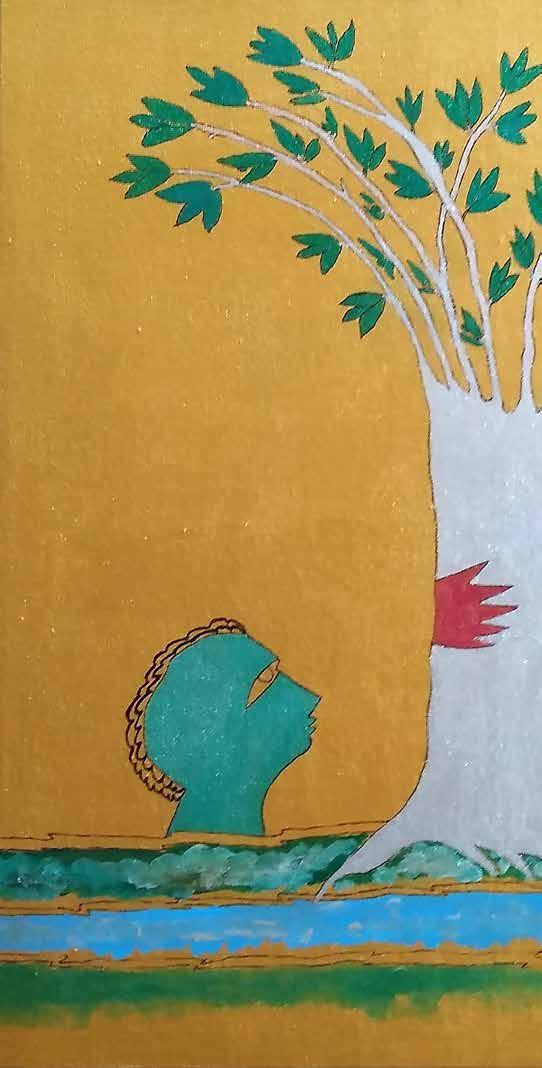

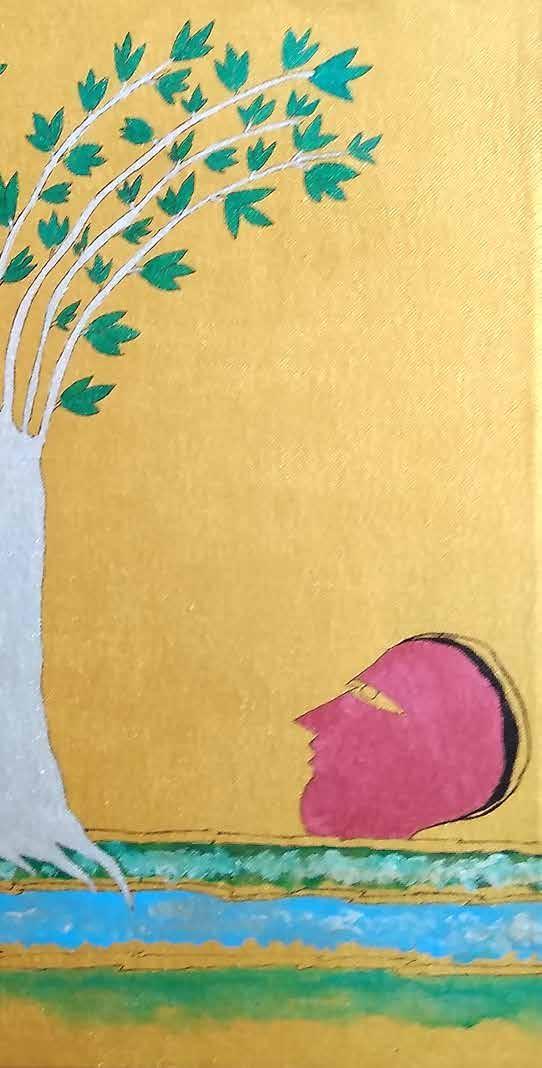

Vasanthi Naidu

Spiritual paintings

Kuching

Sarawak, Malaysia

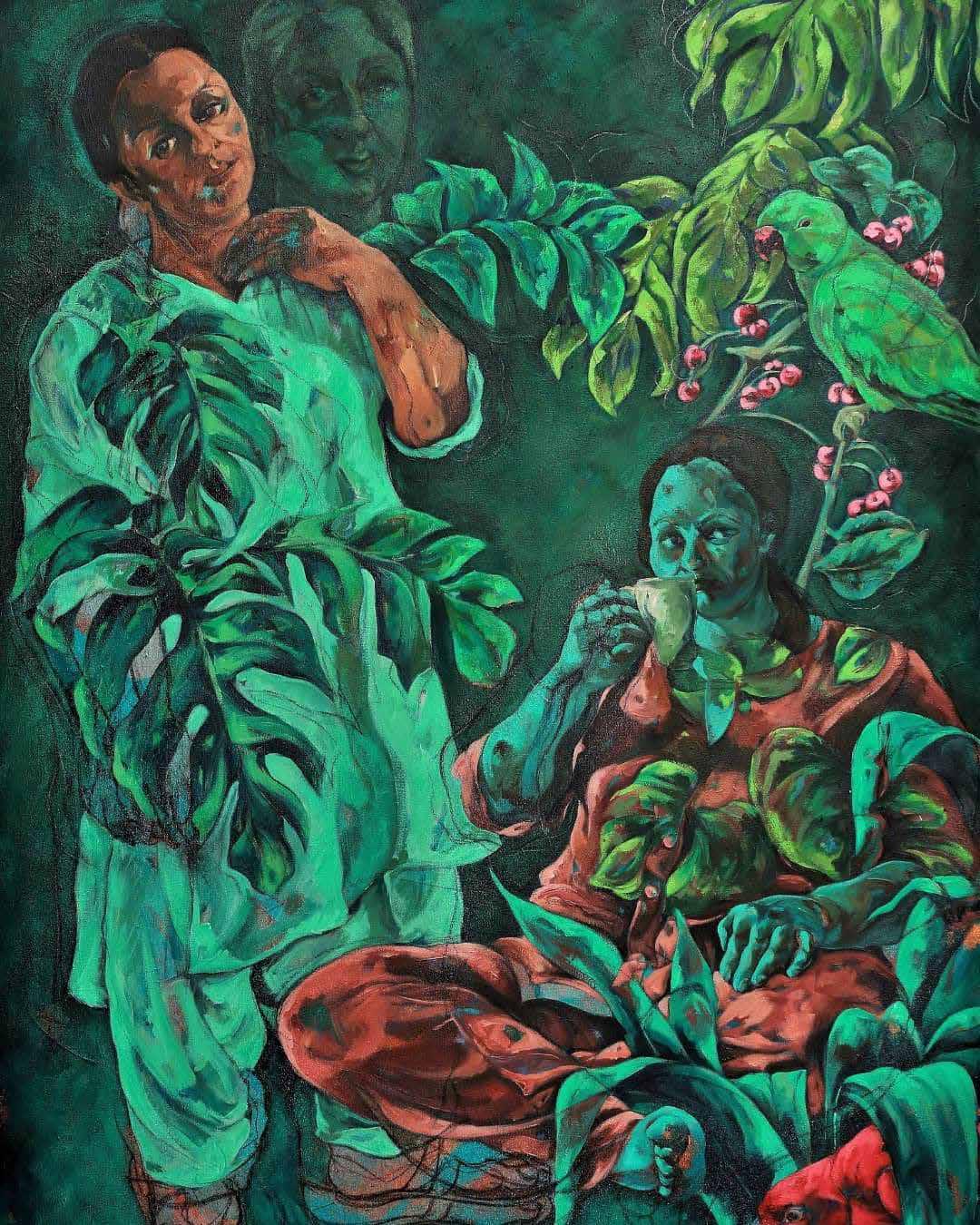

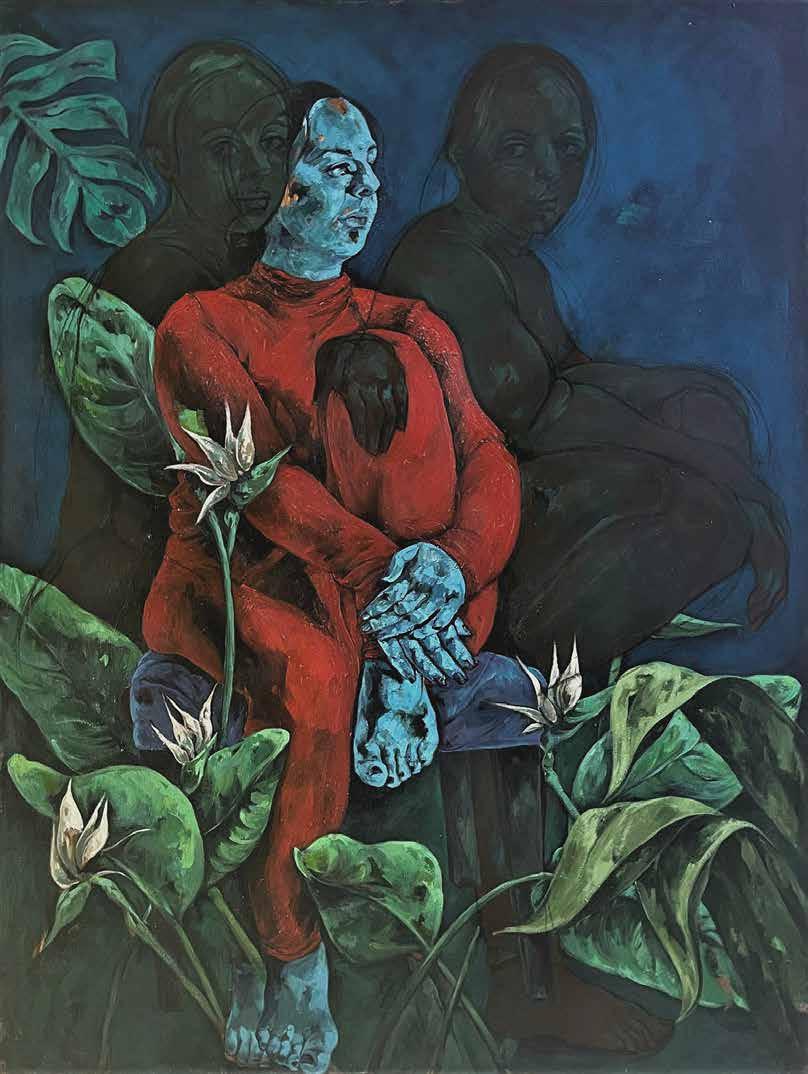

Tamali Dasgupta

Indian artist

The Borneo Cultures Museum

Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

Vietnamese paintings from Canada

From Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

A re-interpretation of Indian feminism in painting

p108

p122

Samphire Island

A short story by Martin Bradley

p134

Joy Ng Mei Lok

Malaysian artist

Francoise Issaly

Artist working in Canada, China and France

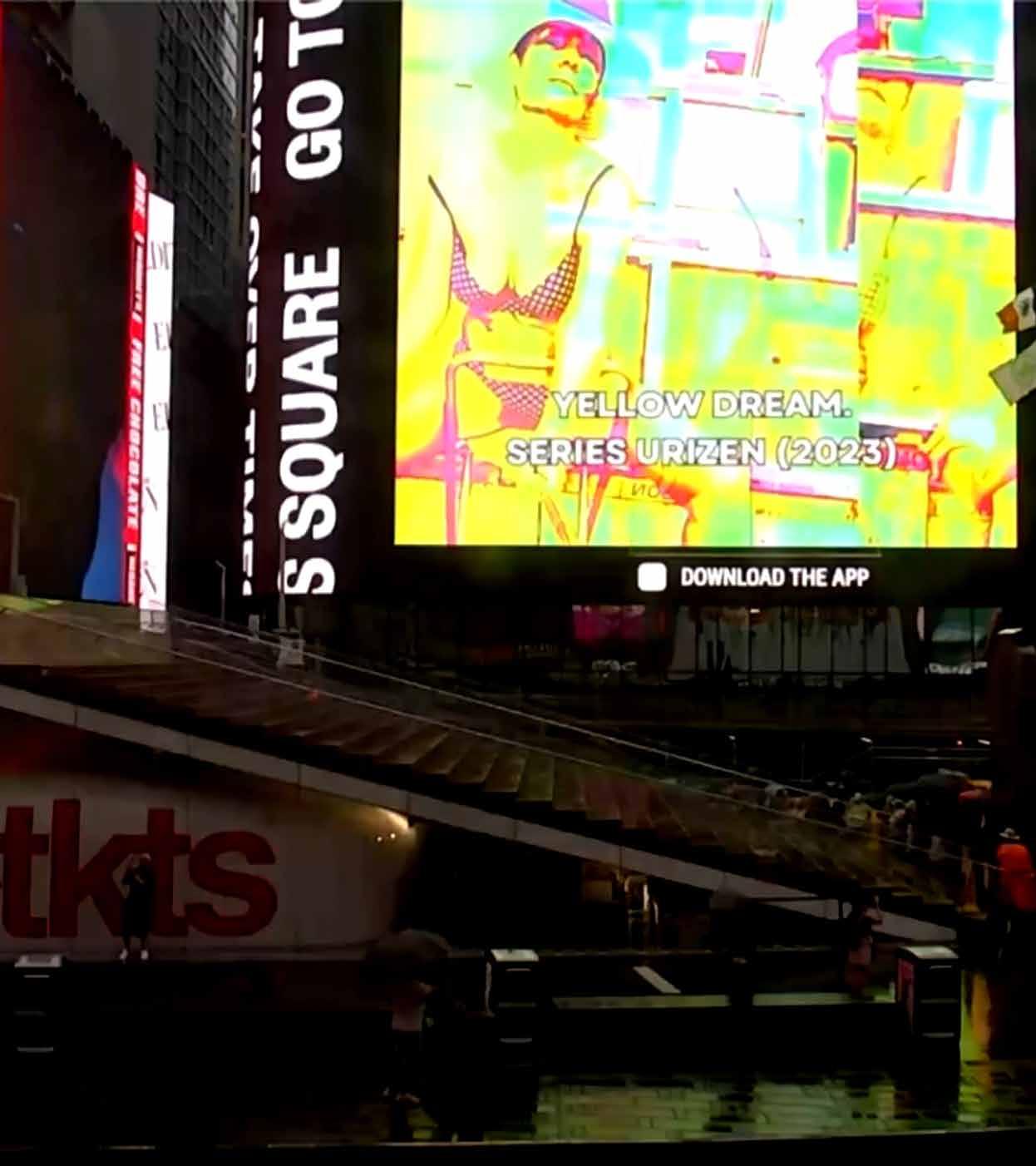

p140 URIZEN

Spanish artist Pilar Viviente

p148

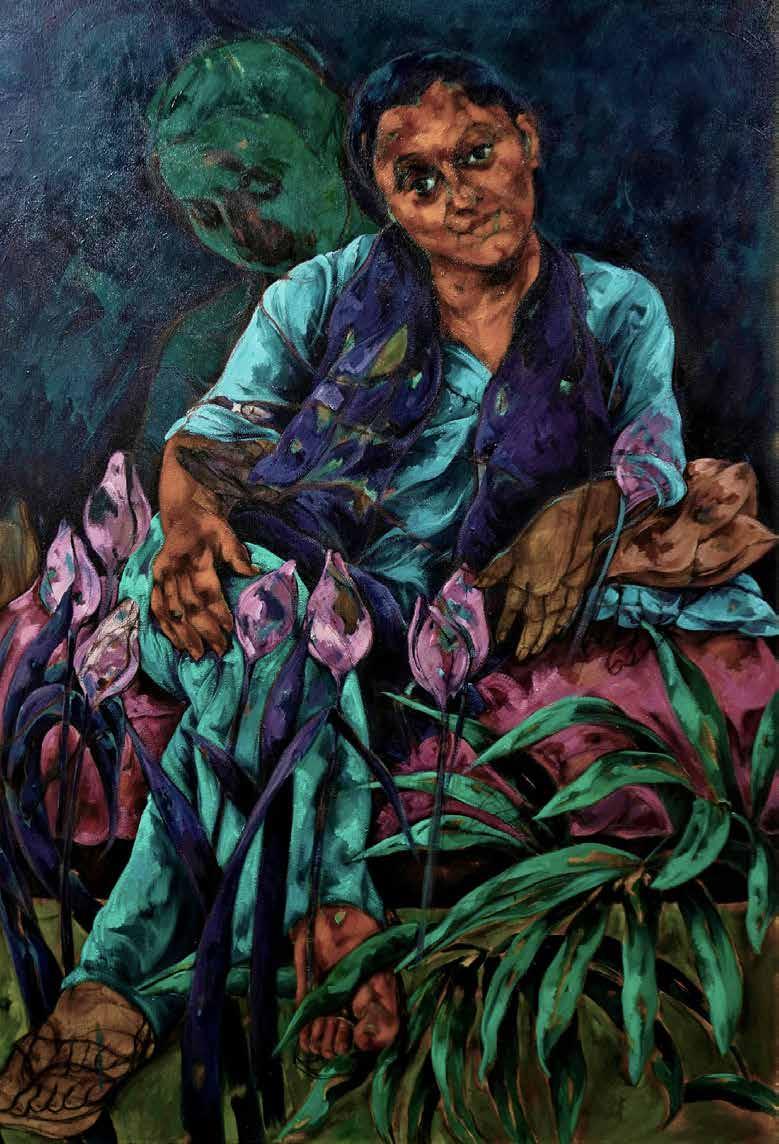

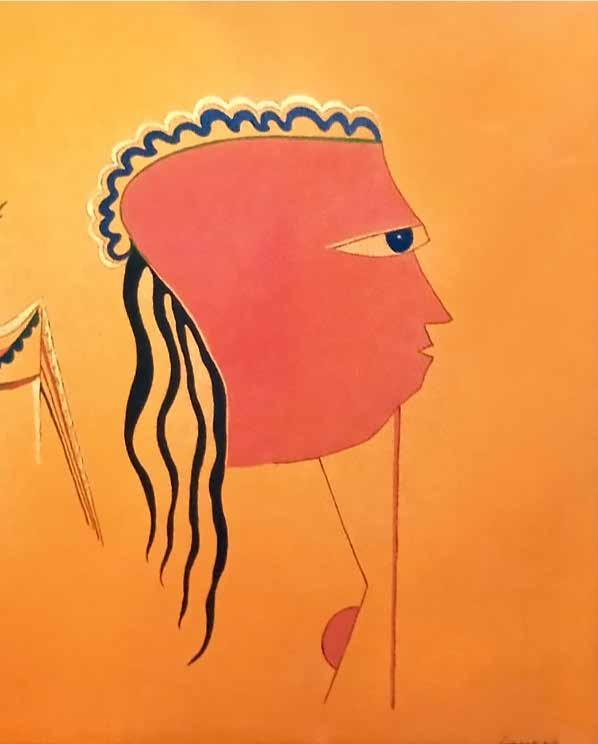

Ganesh Chandra Basu

Indian artist

p158

Kuching Cuisine

Ethnic tastes from Malaysia’s Sarawak

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/samphire_island

The Blue Lotus magazine is 13 this month. My how time flies.

Thank you, as always, for being here and reading this magazine. Do come back to future issues or take a look at past ones on ISSUU.

Submissions regarding Asian arts and cultures are encouraged to be sent to martinabradley@gmail.com for consideration

Take care and stay safe

Martin

(Martin A Bradley, Founding Editor) Image © by Martin Bradley

Image © by Martin Bradley

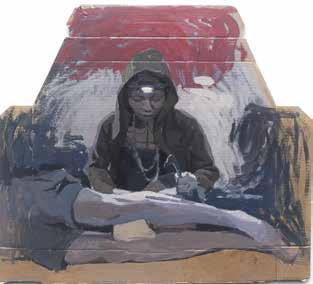

Making a Mark (Tipung Puyang).

Making a Mark 2

Handtapping refers to traditional tattooing techniques as practised by Austronesian peoples. In Borneo, this primarily refers to the handtapping techniques of indigenous Kalimantan, Sarawak and Sabahan ethnic groups. The vernacular terms are speculated to originate from onomatopoeic references to the percussive sound of handtap tools. These are a mallet (or tukul; tutuk), and a hafted handle axed with the tattoo needle.

Handtap needles used to be made from organic materials such as hardwood, bone, porcupine quills, bamboo or thorns, though contemporary tattooists use modern stainless needles for sanitary reasons. The mallet and handle are traditionally made from hardwood incorporating carved details invoking traditional oral and fauna motifs. Others are generations-old keepsakes from their respective communities, whilst others being antique acquisitions from shops.

Even the carrying cases and pouches range from simple wooden boxes to bamboo tubes, tarap bark rolling mats and one unique example made from python skin! Traditional pigments are derived from a mixture of kitchen soot and burnt sugarcane ash, although modern tattoo inks are used to reduce post-session infection.

Generally speaking, handtap tattoos are symbolic and signify various meanings from tribal kinship, social status, protective wards to commemoration of notable achievements. Usually monochrome, elaborate designs further incorporate ritual chanting, mantras, or an offering prior to commencement. Patterns and meanings are context dependent on the community, natural motifs or even the social status of the sitters.

As world religions were imposed upon indigenous communities, tattoos were seen as taboo, linked to criminal gangs, prison life or subcultures inviting discrimination from the public. Many tattooists also come from communities that suffer from systemic issues due to rural poverty, poor infrastructure, state-endorsed deforestation and land clearing. The realities of urban migration meant the lack of transmission (of handtapping skills) to an increasingly urbanised younger generation.

Additionally, ritualistic traditions (chants and certain mantras) complementary to the inking process are in danger of being forgotten. Designs traditionally associated with practices such as headhunting, or tied to tribal hierarchies for example, do not carry the same relevance today. The time-intensive technique often meant that handtap tattoos had to compete with faster machine, flash and handpoke commissions. Within their respective countries, stigmatisation against body modding culture and inking practices persist, with traditional designs having to adapt to modern dress codes.

Thankfully, handtap tattoos has made a comeback in the last few decades. One notable example is the recent Vogue magazine feature on Apo WhangOd, mambabatok master tattooist from the Butbut community (subset of the Kalingan ethnic group in the Philippines). Parallel to this is the revivalist trend of ancestral knowledge. Body modding culture is seen as more acceptable, with cultural taboos giving way to mainstream recognition.

Renewed appreciation of ancestral practices meant more resources for the preservation of moribund traditions such as handtap tattooing. Many contemporary practitioners are young, having learnt the skill via commercial apprenticeships rather than established lines of succession. Others encountered the craft after decades long professional careers, through travels [bejalai (iban); merantau (bahasa indonesia)], research, or through their respective artistic practices.

Despite the challenges, still they persist. Sitting with mallets and needles, diligently tapping away, headlamps illuminating ink in a bamboo island. Their journeys across nations, borders, communities not merely written in books, but indelibly onto their very skins.

Brandon Ritom

My paintings are not different from what has touched my life. Being an artist is having a call to bring the message of beauty and universal wisdom

Leonard Siaw

Leonard Siaw

The ‘Grab’ (taxi) arrived before time.

The Air Asia flight was on time. And, before I knew it, I was standing, in time, waiting for another Grab. This time to take me to the Borneo Hotel, tucked away at the back of Kuching's old town, in the capital of Sarawak, North Borneo island.

FYI Kuching, in the Malay language, means ‘cat’. I am also led to believe that one origin of the name "Kuching" refers to the "old well" which had been at the Upper China Street, in Old Bazaar area. "Old Well" is pronounced "Kuching" in the Chinese Teowchew dialect. There’s even a curious cat museum in Kuching, at Petra Jaya, and roundabouts enthusiastically harbouring imposing cat sculptures.

Borneo shelters three countries on its large tropical island. Borneo is physically part of Indonesia, while the rainforest dominated states of Sarawak and Sabah, to the north of Borneo island, belong to Malaysia, and their neighbour, Brunei, is a smaller, independent, kingdom which, in antiquity, had included Sarawak and Sabah within its borders.

Sarawak has variously been called the ‘Land of Smiles’, and by its old Portuguese cartographer’s name of ‘Cerava’. You might remember Sarawak’s curious history as a country once ruled over by England’s Brooke family, who had ruled the Raj of Sarawak from 1841 until 1946, effectively becoming ‘White Rajahs’. After the Second World War, occupation by the Japanese, and later becoming a ‘British Crown Colony’ Sarawak gained independence but later, after the 1962 Cobbold Commission, Sarawak gave its independence away to join the newly forming Malaysia, in 1963.

An increasing modern urbanisation, replete with sky-scrapers and spreading suburban housing, seems to be wiping those smiles away, maybe because of all the stresses that modernisation brings.

Kuching, Sarawak’s state capital, is prone to traffic jam tangles at ‘rush hour’, just like its sister cities Kuala Lumpur and Penang, over on peninsula Malaysia. Kuching struggles to maintain a balance with

its modernisation and shopping malls, while also trying to retain the remains of antiquity and honouring Sarawak’s various ethnicities.

Unlike peninsular Malaysia, which turns increasingly blind eyes to the plight of its indigenous peoples, Sarawak increasingly embraces ethnic differences. This was, and is, witnessed in an impressive Borneo Cultural Museum (5 floors), revealing the various peoples of Sarawak, their ways of life and cultural heritages. There were also Kuching’s various eateries which promoted ethnic and divers foods, as well as its ‘Chinatown’, displaying replica indigenous fashion designs, as well as hand-crafted items, for the tourists.

I stayed in the sixty year old Borneo Hotel. Opposite of which was the merest hint of rainforest. With a great deal of imagination, the avid traveller, upon looking out their hotel window, might just have been able to discern distinct Jungle type movements, which

untethered minds might unwittingly mistake for mammalian and/or reptilian wildlife. In reality, it was a wasteland given over to a spinney replete with local tropical vegetation, and visiting birds.

Although it was entirely possible to walk from the hotel into the town centre, with its heartland of Chinatown and Indian Muslim areas (which I had done on the first day), the inconveniences of intermittent rain, and increasingly sundering heat, made travelling by ‘Grab’, overall, more practical.

In places, the city of Kuching had reminded me of the cleanliness of Singapore, the small town feel of Ipoh, the tourist orientation of Melaka and, outside the immediate centre, that of Kuala Lumpur (around its Pasar Seni and Chinatown areas). There was enough of the ‘old’ Kuching town to be endearing, especially adjacent to the meandering river, and enough of the relaxing feel of Malaysia’s Muar, in Johor, to be entirely comfortable. That was, especially, when encountering mature ladies selling fresh fish, large prawns and impressively sized mantis shrimps, roadside.

Although I am not a big fan of murals, or ‘street art’ as it has become known, Kuching did seem to have some fine examples of mural work illustrating crafts, and/or the country’s history. Especially those images on the long wall of ‘Kai Jo Street’, and those splendid works by Leonard Siaw

As well as ‘photo opportunity’ antique shops and restaurants, partially hidden down Ewe Hai Street (incidentally named after an early Chinese leader known as Kapitan Ong Ewe Hai) and Carpenter Street (aka Atap Street), there was enough of the old town to remind the curious visitor of those early days when Chinese immigrants had travelled along Sarawak River, through Santubong and had landed at the Old Bazaar area, during the early part of the 18th Century.

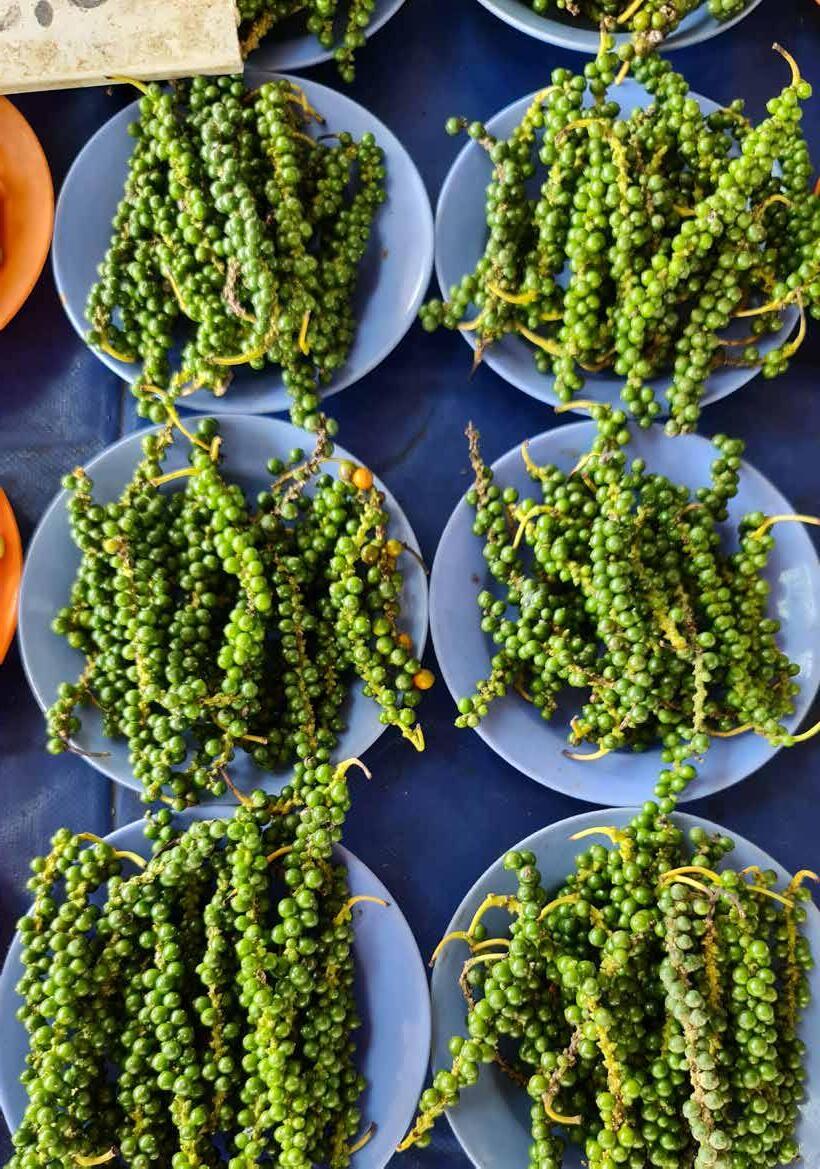

There were just enough genuine antique shops with authentic ethnic objects d’art, exciting shops selling local and imported coffees and real packets of the famed Sarawak peppercorns (white and black), to retain the heightened interest of visitors (and reminiscing locals), to keep the engrossment and the romance alive.

Within seven days I had fallen for Kuching’s numerous charms.

Tamali Dasgupta,was brought up in India’s Kolkata. In one interview she is quoted as saying...

“I always wanted to be an artist since the time I can remember. In my childhood, for me, every available surface was a drawing space and all discarded materials I would transform into some object of art. My study books used to turn into sketch books.

Margins of my text books and copies were full of scribbles and sketches. Art class was my favourite class and I was always the favourite student of my art teachers. I was always helping my classmates with their art projects. I graduated in visual art with a first class from the Rabindra Bharati University,Kolkata in 1992.

The teachers and the environment of the Jorasanko Thakurbari campus– the unused and neglected rooms of ‘andarmahal’ with their silent stories – which we loved to explore and which always used to awaken my imagination and curiosity shaped my into the artist I am today”

https://www.thebestaddress.co/tamali-dasgupta/

And the search goes on....

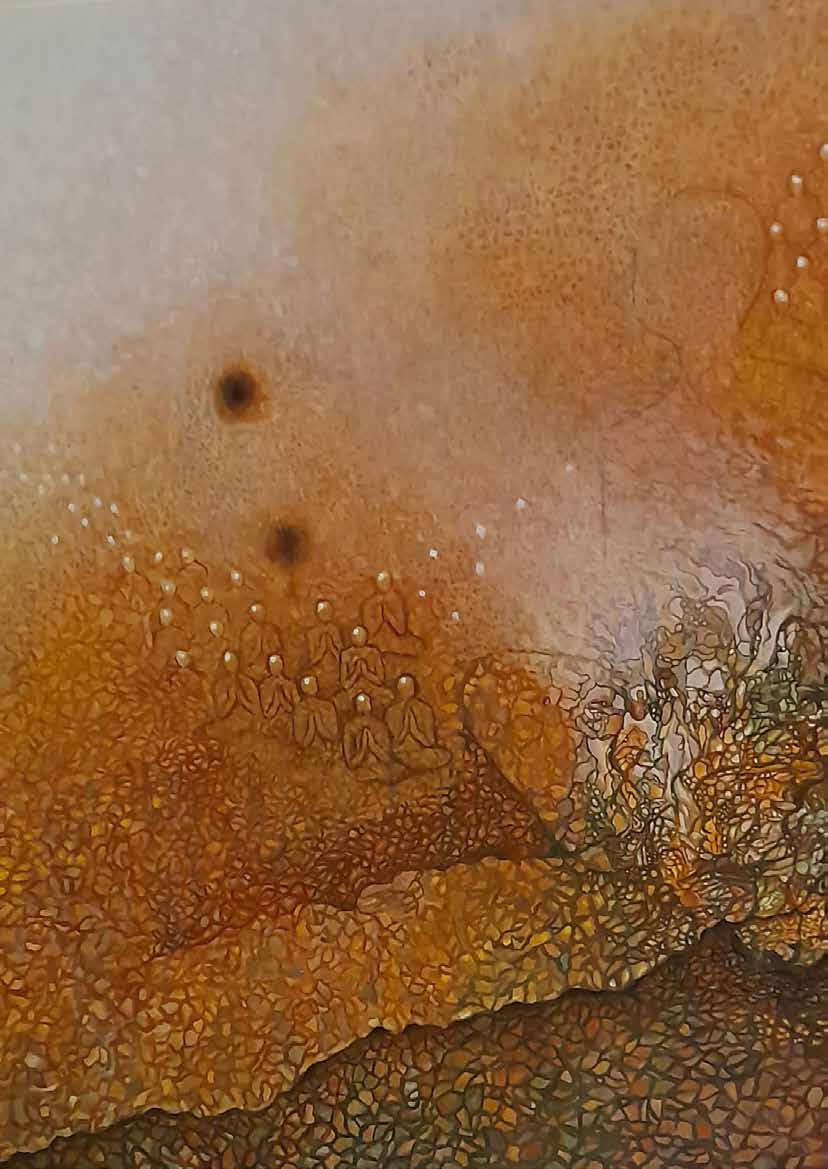

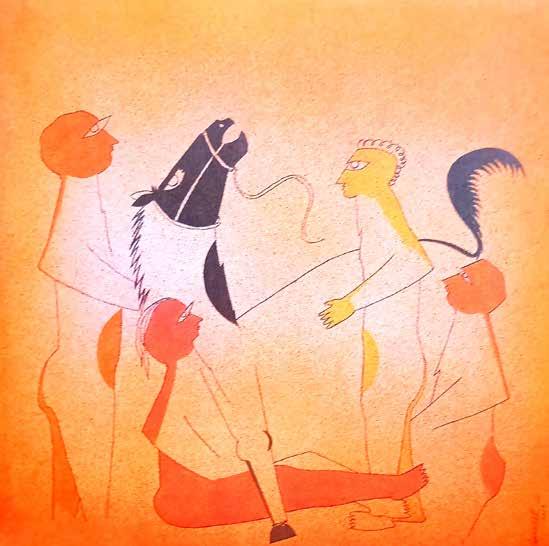

The congregation

While in Kuching, I couldn’t wait to visit the Borneo Cultures Museum, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia.

The Borneo Cultures Museum is the largest museum in Malaysia, and Southeast Asia's second largest museum. That museum opened its doors to the public in 2022 and sits adjacent to the Sarawak Museum (Old Building) in Kuching.

Its webpage mentions...

“The Borneo Cultures Museum is located in the centre of Kuching city next to Padang Merdeka. This five-storey building is designed in a modern style, with distinctive architectural features that reflects Sarawak’s unique traditional crafts and rich cultural heritage.

Each gallery within this five-storey building offers a different experience. The children’s gallery theme on the second floor is 'Love our Rivers’, the ‘In Harmony with Nature’ gallery is on the third floor, the ‘Time Changes’ gallery is on the fourth floor, and the ‘Objects of Desire’ gallery is on the fifth floor.”

Although I, initially, baulked at the entry price (RM50) I nevertheless was determined to visit. I was so very glad that I did. Luckily there were concessions (RM5 for older locals, and RM25 for older foreigners like me). While the first couple of floors were okay, but nothing too special, once I entered the third floor all that changed.

Mind blowing, exceptional, ****** fantastic were all terms which seeped into my consciousness. That is when it wasn’t full of the sights and sounds of astounding exhibits. To say that the museum it was ‘worth every penny’ is a gross understatement. Dear reader, if you get the opportunity, do visit this exception place. It really does help with understanding Sarawak, its peoples and its cultures..

Quite obviously it was a meal which needed several sittings, and could only be

The Borneo Cultures Museum

Jalan Tun Abang Haji Openg, 93400 Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

The Borneo Cultures Museum

Jalan Tun Abang Haji Openg, 93400 Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

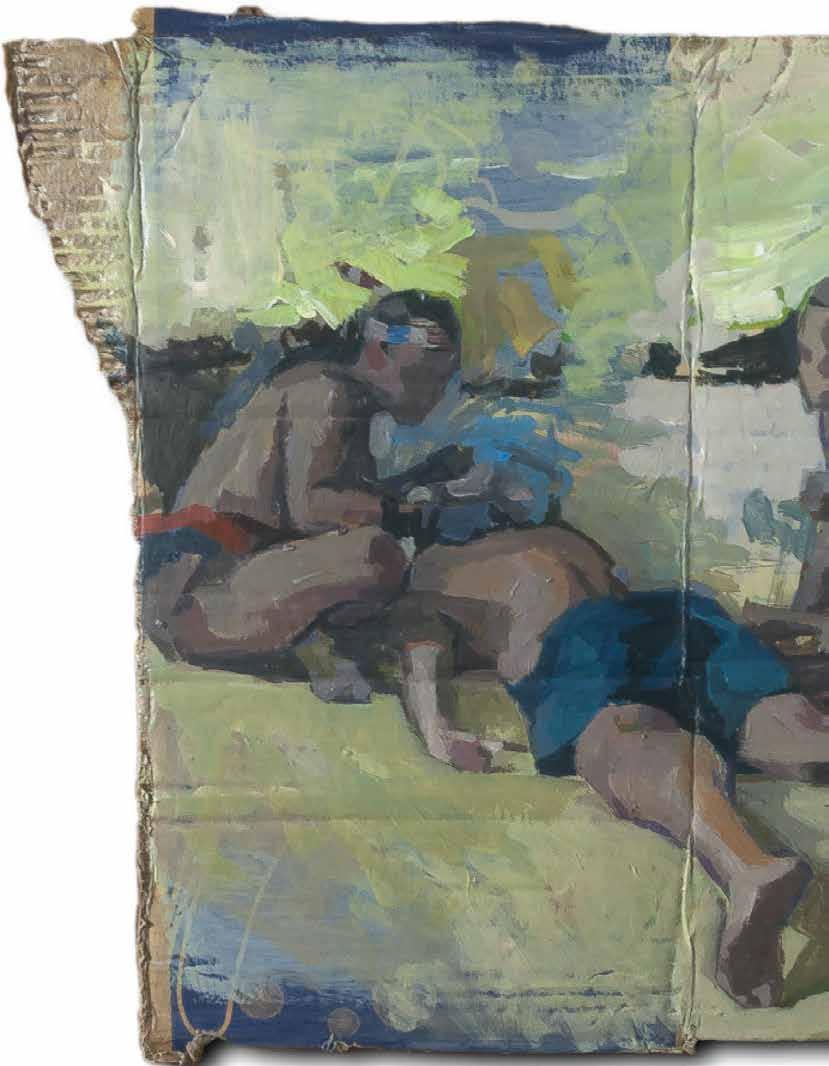

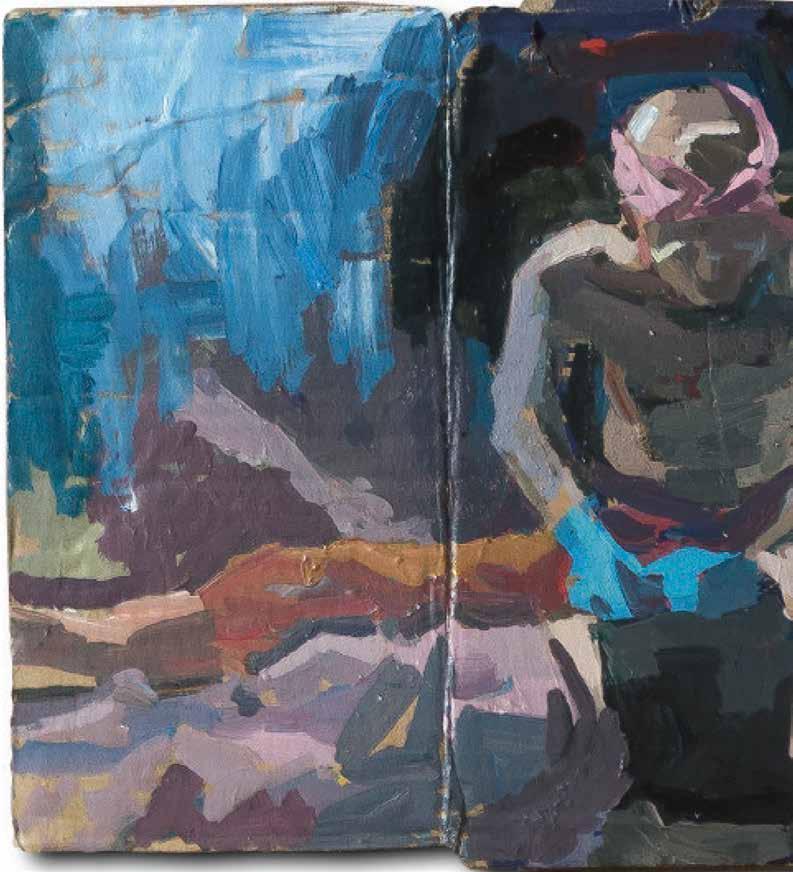

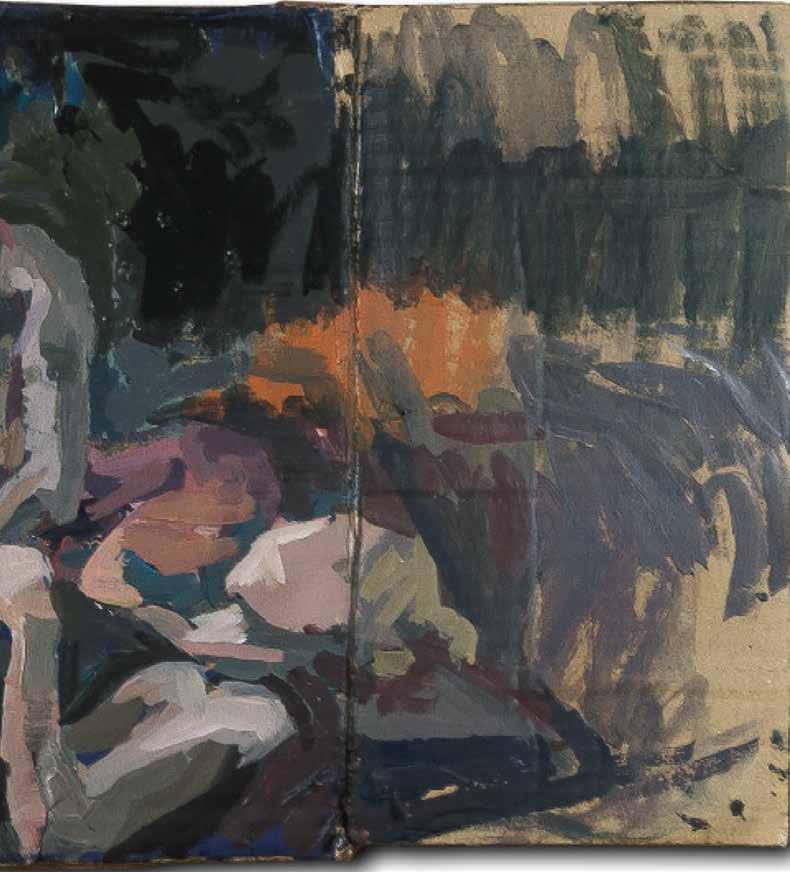

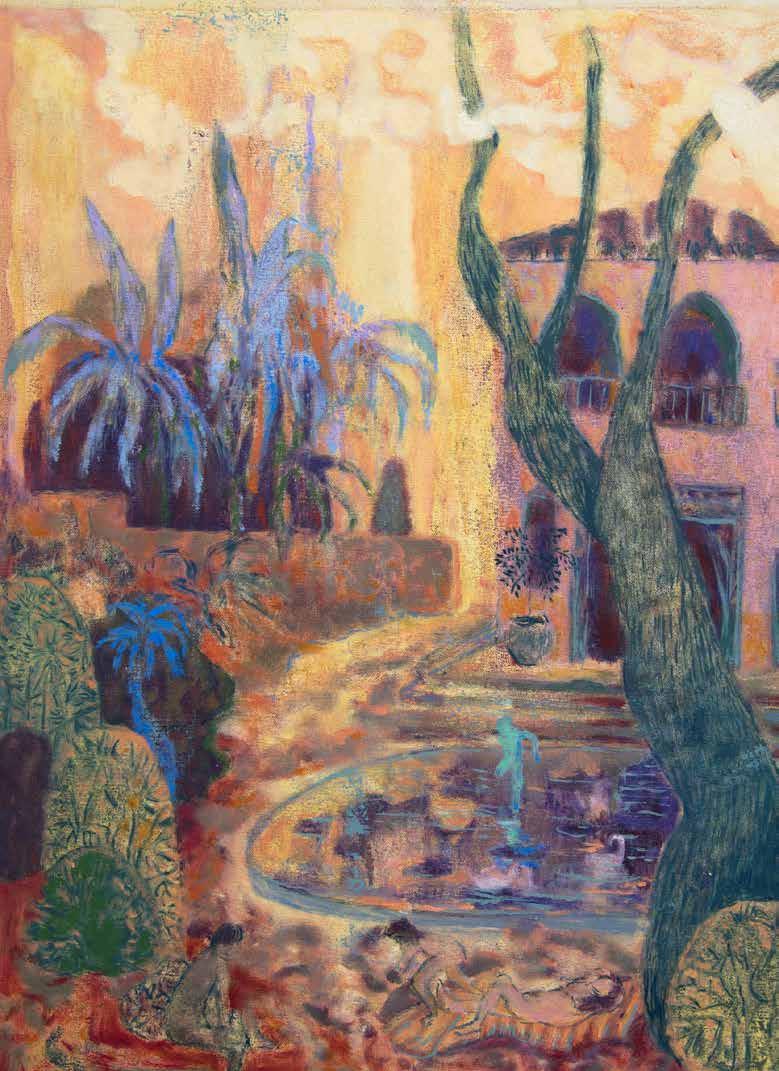

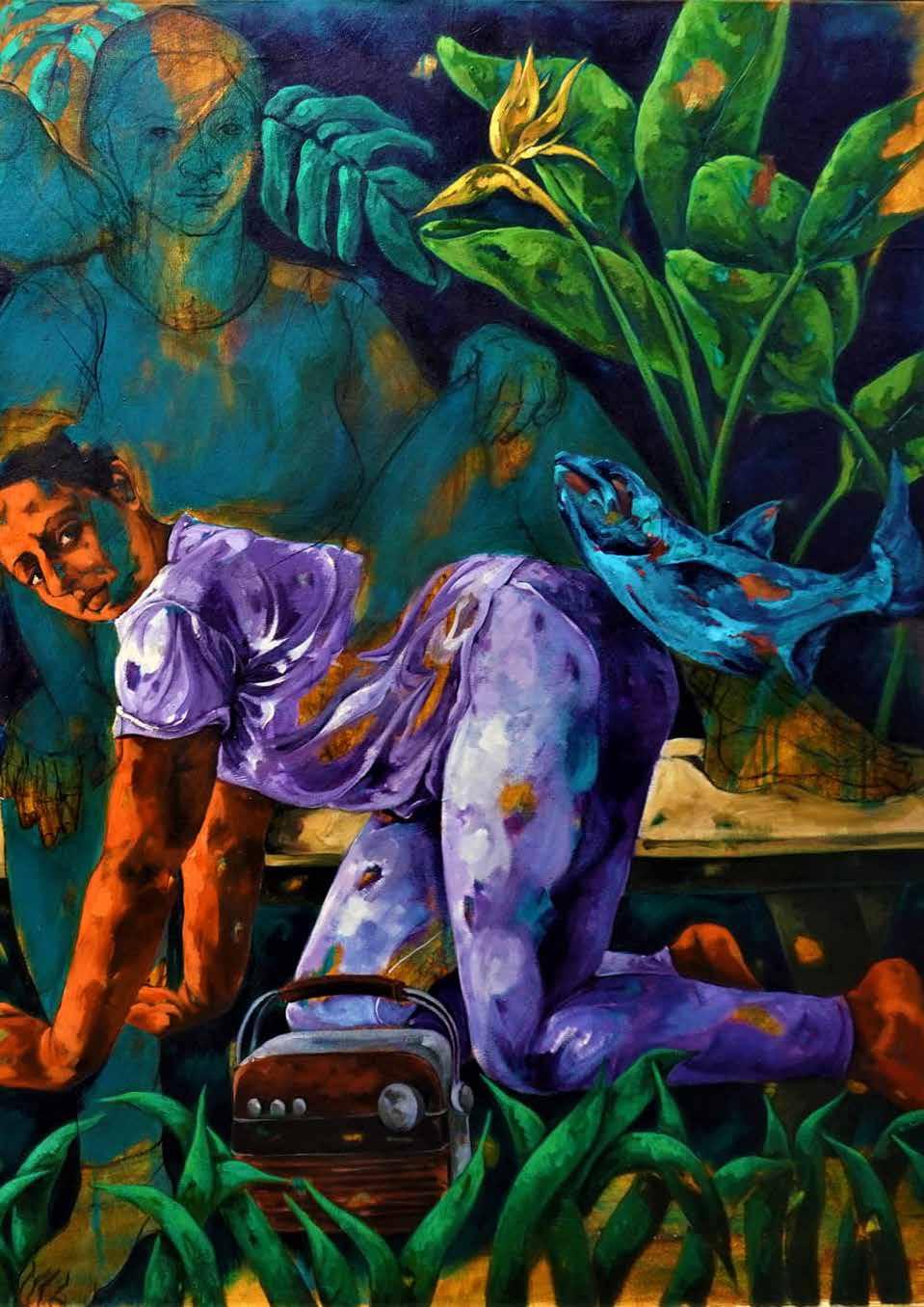

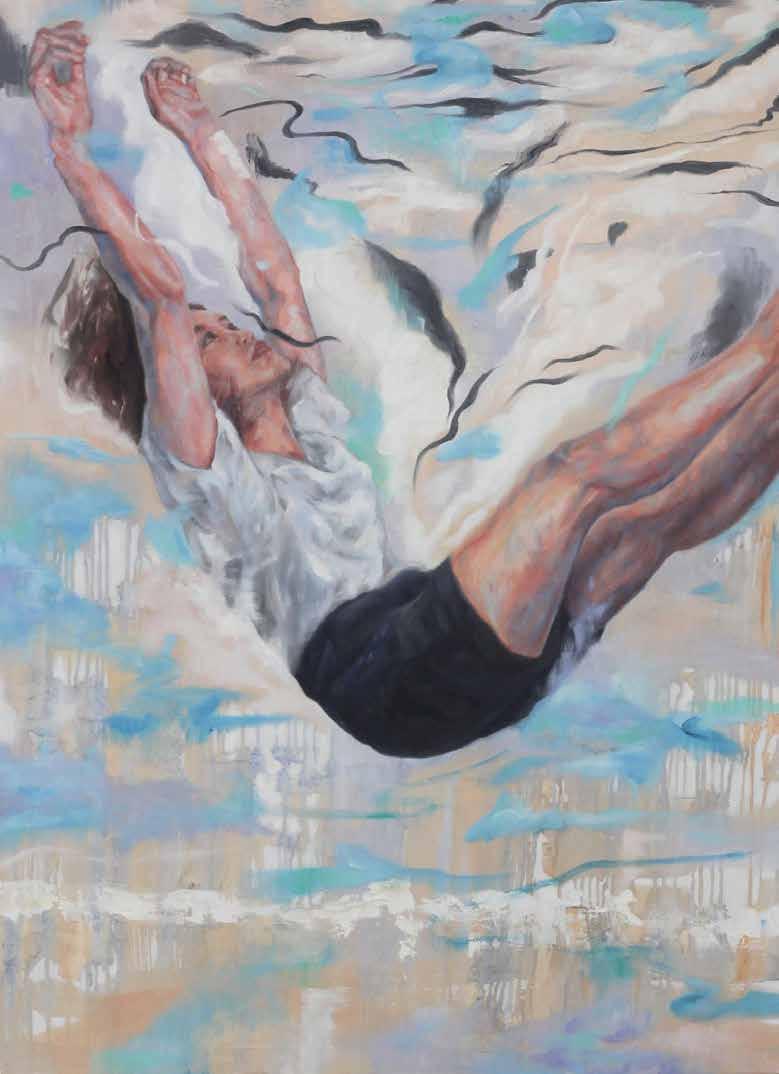

Tuan Vu, who lives and works in Montreal, Canada had his artworks on show at the ‘Art Singapore Fair’, by the Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, Singapore, 2024.

According to Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery’s blurb...

Tuan Vu was born in Saigon, Vietnam. His preferred mediums are drawing, painting, and photography, which does not prevent him from touching also on design and architecture. Although he has attended several drawing, painting, and photography workshops at the University of Montreal over the years, he remains essentially a self-taught artist. His pieces were first seen at an auction he organized in 2010 to help people in Haiti hit by a devastating earthquake.

Les arômes d'un après-midi

Raphael Scott Ahbeng, Silent Afternoon

Raphael Scott Ahbeng, Silent Afternoon

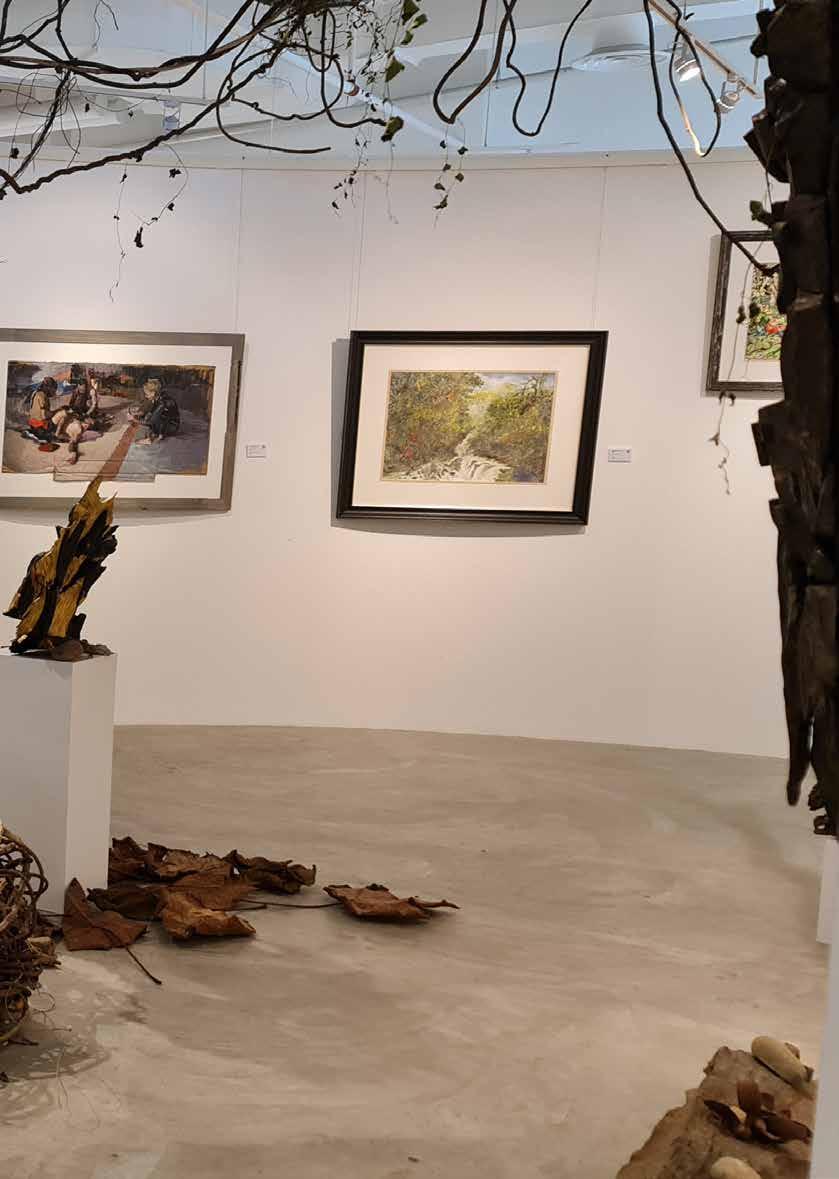

That curious beast known (by some) as ‘Fine Art’ was on display in the Hoan Gallery (tucked away in Kuching’s HSL Tower, Lorong La Promenade 2) and in The Borneo Hotel (where I just happened to be staying and which specifically displayed the works of Sarawakian artist Melton Kais). My appetite for Sarawakian art grew, as did the need to share this short article.

A quick history-of-art search for Sarawak revealed the paper ‘Post-War Art Activities In Sarawak [1946-1963]’ by Rahah Haji Hasan and Anna Durin who, in 2009, which made the point that …

“Before the Brooke period (sic the White Rajahsa hereditary monarchy of the Brooke family, who founded and ruled the Raj of Sarawak as a sovereign state, located on the north west coast of the island of Borneo in maritime Southeast Asia, from 1841 to 1946), there was never any exposure to Western art such as oil paintings on canvas or watercolour among the natives of Sarawak. There were however, paintings done by the Kenyah people to decorate the wall of their leader’s room to symbolise status within the community.”

(Rahah Haji Hasan. 2010. Post-War Art Activities In Sarawak (1946-1963); Gendang Alam; Journal of Arts, 91-107, (VOL 1, 2010, ISSN 2180-1738). School of Arts, University Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu. Sabah)

And from the period 1946 to 1950….

“Artists, in and outside of Kuching, were encouraged to exhibit their works which were then viewed not only by Chinese but by other races as well. There were also a few local Chinese who did some Chinese paintings themselves. Painters, such as Tsai Hong Chung, held a one-man exhibition in Kuching at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, a building owned by the Chinese Community that supported art activities not only in fine art but also in music and theatre. The Chinese also organised some major cultural exhibitions, which not only generated good income but also helped in promoting Chinese art and culture in Kuching.”

Rahah Haji Hasan and Anna Durin, op cit

I discovered that the ‘Kuching Art Club’ had been established in 1946, by Susi Heines, an art educator, and Lucy Morrison a government officer working during the colonial era). In 1947 the ‘Batu Lintang Teacher’s Training College’ had introduced art into its curriculum and, during the late 1950s, the Sarawak Museum (established in 1886), had started its collection of paintings.

Text from Hoan Gallery’s recent exhibition ‘Rebirth’ (2024) informs the visitor….

“The Club’s (sic ‘Kuching Art Club’) goal was to organise alongside other groups - like the Music

Societies and Floricultural Improvement Society (both formed in 1947) - in the optimistic air post World War Two.

Newspapers reported of weekly classes, biannual art exhibitions and even published reviews of solo shows.

Within months of the club's founding, it had gathered 80 "very active" painter members, reported The Sarawak Tribune.

A year later, the Club had enough art to hold an “all member exhibition" on the weekend of February 11, 1950, at the Maderasah Melayu (present day Islamic Heritage Museum).”

I was informed by Kuching’s Hoan Gallery (in their amazing exhibition ‘Rebirth’), that in 1975 Chong Liew Syn (born in China 1949) who was an artist and graduate of Hong Kong’s Fine Arts School had “...established the Sarawak Fine Art School - the first certified arts institution in the state.”

Ten years later (1985), saw the birthing of the Sarawak Artists Society (SAS) which is ”…a prestige art society established on. There are currently 50 SAS artists of different races from all over Sarawak, mostly from Kuching.”

“SAS is a platform for local artistic talents to engage and exchange ideas, nurturing them to shine. It actively organises art related activities and events, such as art shows both locally and abroad, conferences, workshops, and so forth. Some of the SAS artists have been invited to international art camps, exhibitions, residencies, and etc. Governmental bodies such as the National Visual Art Gallery, Sarawak State Library and the Sarawak Museum, as well as private art galleries have worked closely with SAS to promote its artists and their creations.

SAS main objective is to promote the interest in art and exchange of ideas and experiences with its members and other societies of similar pursuits. It also aim to increase art appreciation in Sarawak. It serves to create awareness among the public on the importance of art. SAS is also determined to raise the standard of art in Sarawak to be on a par with the rest of the country in terms of skills, knowledge and mindset by providing opportunities for exposure and interaction with foreign artists.

SAS serves as a ‘Cultural Ambassador’ to bring

Sarawak to the rest of the world; it strives to work with the state government in its effort to preserve and promote the local cultures, arts and crafts.”

Jumping ahead the, now late, Sarawakian artist Raphael Scott Ahbeng (commonly known as RSA) had been born in Bau, outside the capital Kuching, in 1939. With thanks to the British Council, RSA studied art in England, at the Bath Academy of Art from 1964 to 1967, and later studied drama in London, in 1973. He had sadly died near his birth place, in 2019, before I could visit with him in his rural Sarawakian home.

I did, however have the good fortune to chat with him, in 2015, at a joint exhibition ‘From Sea to Summit’, of RSA’s artworks and those of the late Joseph Tan, Yeong Seak Ling and Avis Mohamad, at Malaysia’s ‘Muzium Dan Galeri Seni’ (Museum and Art Gallery) at Kuala Lumpur’s Bank Negara. There had been, at the time, some talk between us about me writing a book about RSA, but, sadly, that publication has never reached fruition.

Continuing good fortune enabled me to visit the ‘Rebirth’ exhibition (Jan 8 to 14th May 2024), at the Hoan Gallery (HSL Tower, Lorong La Promenade 2) on its final day, to catch up with Sarawak’s art history, as well as its contemporary and contemporaneous art making.

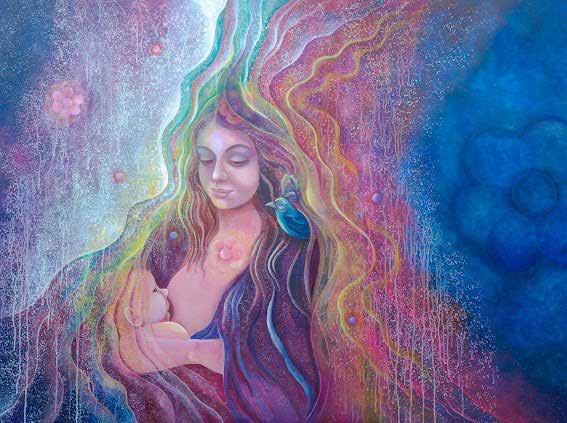

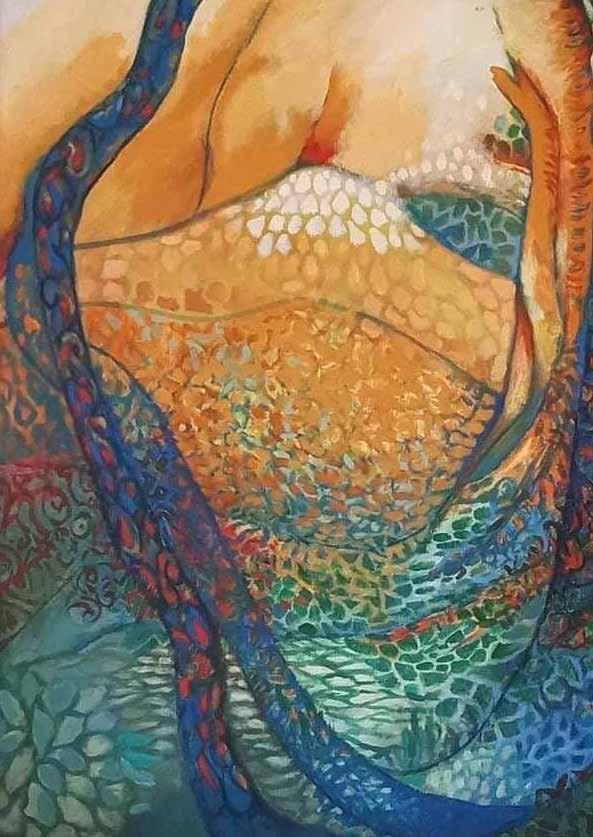

Memories of the Happily Ever After I

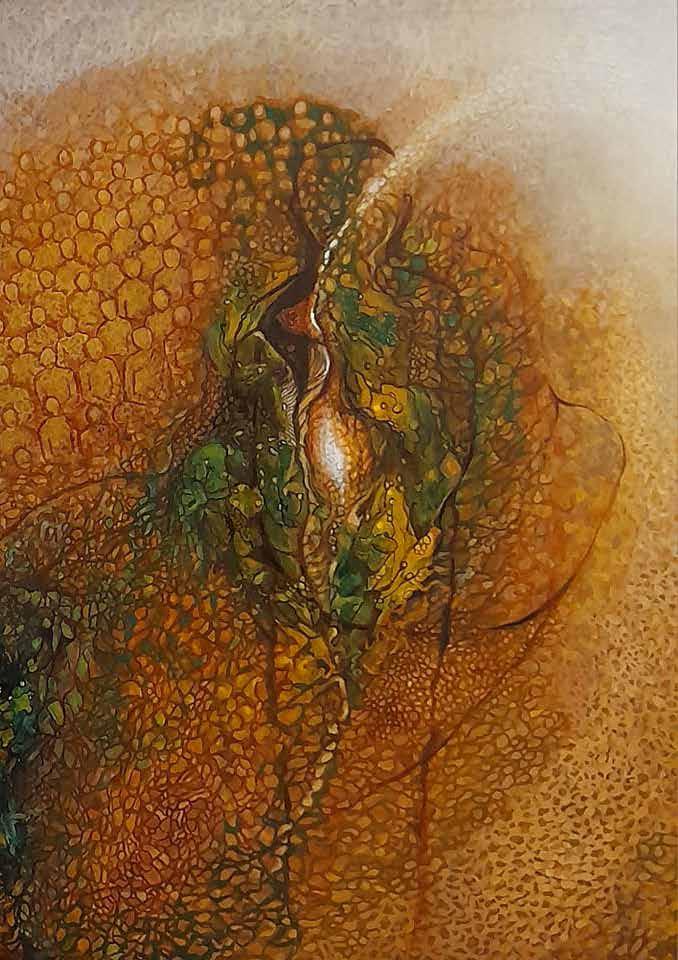

BleedingStemming from my contextual interest in art historical representation of the 'Feminine', my work is a reinterpretation of stereo typical aesthetic and cultural notions about ‘woman’, the female body and beauty. Woman has historically been ‘imagined’, objectified, and stereo typed in art as passive and submissive. She is present but always as a visual/symbolic metaphor for sensuality and eroticism; a powerless, available object; and the narrative, the vision is always that of the dominant male. Such imagery serves not only to represent but reinforce the ideology of power and dominance in the gender context.

My work, therefore, is an attempt at raising questions about identity, gender roles and power dynamics.

It is very much subjective—a self portrait, based on personal experiences and perception of self as a woman, constantly negotiating and recreating my identity and space in personal and social life.

I intend to create autonomous female spectator-ship independent of patriarchal values, where women identify and relate with the subject, and, are intellectually inspired to reinterpret their reality and identity.

Using paint and mix media, I use both semi-translucent and opaque layering to create the illusion of depth and a rich visual and perceptual experience. The making/process of my work is instinctive and impulse and inner vision take the lead and evolve meaning, freeing the subject matter from concerns of genre, content and its original context.

Taken from https://www.saatchiart.com/farazehsyed

My Body Remembers

Five miles long and two miles wide, the island, there since time immemorial, had housed humanity since before the coming of the Bronze Age; before the making of the trackway; before the coming of the Celtiberians familiar with fishing and farming, migrating from Iberia; before the Romans favouring the island’s native oysters, bringing grapes; before the later seafarers, the sail lovers, the sand and wave fanciers, the Royal Academician creatives painting, printing and photographing the island’s natural beauty.

Onthe pre-summer island the sun had kissed growing samphire. It had caressed oysters on their half-shells where squeezed lemon droplets glistened.

There’d been blue skies, diving seagulls, the soft chiming sound of docked yacht-masts in the sea breeze, and scents of sharp ozone, sea-salt brine and of cloying mud.

Eventually grey clouds had clustered, chasing the sun from pebbled beaches, from seaward facing beach huts and coastal flora. Only sporadic cobalt skies had given hope, briefly illuminating black framed, antique, white cottages.

J had arrived on that isle late in the April of that year. He’d travelled on the lower deck of a local dual-red, double-decker Scania omnibus listening to the bus’s tyres talk of terrain, potholes, and crunching loose gravel. J had experienced the feel of that bus’s passage, its motion, swaying as if tumbling, caught in forward progress, falling headlong down the claustrophobic, darkened patches of the old road, brushing hedgerow branches and tree limbs, throwing itself around uncomfortable corners then finally approaching the open of the causeway, as if in triumph.

As far as J’s eyes could see, across the estuary causeway, the land had been characteristically East Anglian flat. To one side, and in the distance, a church towered over practically idyllically sculptured trees and farmhouses. The other side of the estuary had drawn his eyes to distant, blooming, borage fields, effectively carpeting the landscape purple-blue, watched over by an azurite sky and hazy sun.

The diurnal tide had been ebbing as the vehicle

moved onto the causeway. J, intrigued by rivulet channels carved from glistening salt-marsh mud, had observed that altogether surreal landscape which, appearing temptingly solid, was watereroded topography and known to be deceptively insubstantial, deadly even.

At that time, the bus had easily carried its half dozen passengers across the causeway. However, later in that same day, that same construction had flooded due to the tidal force phenomenon (the sea-water’s natural flowing preventing the island’s ingress and egress for more than one hour and a half). At full (or new) moon the briny was apt to become more robust in its incursions, and the isle reverts to its natural status, divorced from the mainland.

That double-decker vehicle had victoriously veered left, up a slight incline. J had encountered fields of snuggly blanketed horses, reclusive houses peeping through lively trees, and farm shops proffering locally made wines from the island’s vineyards. Squat glass jars of fresh, island, comb-honey had sat, adjacent, offered at four British pounds a jar (the money to be placed in an ‘honesty box’ adjacent to fresh local vegetables and other seasonal island produce). Those had quickly disappeared as the vehicle sped onward.

Turning right, the bus had squeezed through a narrow lane which, in another year, would have been bordered by fields of bright, yellow, rapeseed flowers; but then cut, and the field lain fallow. That earnest bus had entered the village’s outskirts, bypassing The Fox Inn and the Island bakery. It had eased past Mohammed’s minimart and Sally’s antique shop then, at journey’s end, came to rest by the Island Cafe and Cock’s butcher’s (opposite the struggling village library, with the Art Cafe in easy sight).

Thanking the driver, J had alighted at the stop opposite that library, and beside the village’s 7th-century church, dedicated to Roman martyr saints (Peter and Paul). J had then had begun a shorter journey (one mile), tramping with his slight baggage through elder blessed paths, equally bordered by deadly wild arum red berries, the ever-present ivy and Roman (stinging) nettle. J had passed an abandoned boat nested amongst freshly erupted bluebells, in a small woodland. With no sense of hurry but, rather, an enjoyment of both the moment and of keen anticipation, J had sauntered down an incline leading towards his freshly rented Tudor (16th-century) house. It had nestled within the historic remnants of that island’s ‘Old City’.

Standing outside the antique white cottage, and before entering what in summer would be a hollyhock and rose country cottage paradise, straight ahead (and within eighty yards) J had witnessed an aged harbour. That harbour had been apt to overflow, flooding the lower section of the coastal road, leaving swathes of black, glistening, bladderwrack as a parting gift. Before he’d opened the white picket gate and walked into his latest adventure, J had gazed left, witnessing drunkenly leaning boats, masts chiming salty tunes in a slight breeze along The Fleet.

J had sensed a homecoming.

Across multiple seas, and for two decades, J had sought solace in the impalpable spiritualities of the East. He’d visited Indonesian Borobudur (seen from a mynah’s eyes as a substantial mandala; he’d walked the vastness of Cambodian Angkor, its glorious templed city of Hindu and Buddhist carvings of demigods, devas, and apsaras.

J had been overshadowed by imposingly broad faces of Asia kings with benevolent eyes, cooled by waterfalls of the Golden Chersonese revealed in jungles megaannum old. He had encountered imposing India, with its ancient Muslim mosques, Hindu and Buddhist temples and churches. Elsewhere, J had been in awe of the lotus filled Xi Hu (West Lake) of China’s poetic Qiantang; its soothing islands, temples, pavilions, gardens and functionally splendid arched bridges spread appealingly before him. Then there had been the magic of Thailand’s Chiang Mai,

the beauteous islands of the Philippines, Dhaka’s older city and the quiet majesty of Chandpur (and its antediluvian fishery).

A raging pandemic had returned J to Albion’s shores.

A conviction for mindful meditation, encouraged by a previous flirting with Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism had followed him. He’d eased himself back into the land of Boadicea, back to where he had, prior to his travels, existed for over half a century.

A hastily-made arrangement had J uncomfortably quarantined (for an official and obligatory ten days), in the house of a friend of a friend, and on that Samphire Island. It hadn’t be an altogether satisfactory arrangement. J had been washed up, alone, on what should have been familiar shores, needing sanctuary.

J had spent the obligatory ten pandemic days on that wild-fowling, duck, goose and curlew island. Despite character clashes, he had extended that sojourn to one month. The ensuing year had been spent, disastrously, in a nearby town, clinging to an urge to return and seek solace on that island for a year of rest and recuperation.

That 1500s rental cottage had boasted low, undulating, white ceilings graced with prominent, blackened, beams and space enough (but not too much space) for a solo occupant. Likewise, J had displayed his own ravages; those of lengthy travels etched into his three-scoreyears-and-eleven. His age, witnessed by silvery locks, salt and pepper streaked beard, could also have been observed in the distinctness of his seemingly tired eyes. They were those of a life well-lived, and a mind increasingly more comfortable in his past than in the lessening years before him.

J’s landlord, merely an insubstantial whitewashed wall away, was a tall, slim, man, possibly ten years older than he. The neighbour had been a dealer of antiques, a elder man of seeming taste and refinement, and one who’d dabbled in antiques long before returning to the country of his birth to string antique tennis rackets, engage in endless pottering in his remarked upon floral

gardens, and the scraping of stubborn barnacles from his yacht (his second home).

On that moving-in day, and to explain the height of the doors, the landlord had mentioned ... “Most people are taller in the 21st century than they had been in the 15th and 16th centuries.” He had continued... “The smallness of the doorways, coupled with floor level variation through time, had meant that there was an adequate history behind J’s constant awareness of living in a Grade II ‘listed’ building.” Eventually, J had learned, through trial and error, to duck his head appropriately and hunch his back while learning to exist in that challenging new environment.

April in the year of J’s island sojourn had slipped into May.

One comfortable, ozone scented, morning, J had partially traversed that gravelly incline, heading up and out on his one mile journey to buy bacon and eggs for the next day’s breakfast, when, about half way up that upward slope, he’d come to a halt.

In the road ahead had been one of the island’s female muntjac deer, unmoving.

That symbol of the Celtic princess Sadhbh had gazed as J had stood, also afraid to move, concerned about startling her. Then, all of a sudden, with a flash of white tail, the vision of the deer disappeared. It was as if she had never been there. J had been left, once more, alone on his breakfast quest.

The season of damson had soon arrived.

Ripe, purple, damson plums had threatened the house’s back garden’s postage stamp astroturf garden with additional, rudely enforced, colouration.

The turf, in its turn, had been disturbed in places by mauve clover, pushing through where strips of turf had almost, but not quite, abutted.

In that rear garden, the (next-door) owner had laid two large paving stones. On them, a squat, collapsible, majorelle-blue painted metal table had sat, accompanied by a solitary chair. A

second chair had reclined against the tall garden gate leading to the adjoining property, to the right of the house, That gate had been wired shut to prevent egress and ingress, as had a similar gate to the left of the property. These bound gates had emphasised the property’s privacy and secluded nature. In J it induced a tightness, an uncomfortable feeling of restriction.

In his new island reality, J seldom visited that attached garden, unless to attend to washing, or to reluctantly weed yellowing vegetation (past its grow-by-date) or to collect those fallen, overripe, damson (turf threatening) fruits. At times, a distinctive cuckoo had thrown out a daily challenge, then remained silent.

Occasionally, seated in the small lounge with its leather furniture, J had recalled times of his youth. He’d remembered the mansion house where he was a surrogate grandchild while his mother worked at housekeeping, for the gentry.

There had been tea-times of earl grey. Interestingly decorated cream cakes, bought especially for him and resting on a delicate, bone china threetier cake stand, on the grand wooden kitchen table, near the ancient Agar baking dinner for 10 spaniels.

As the seasons had worn on, there had been towering summer flowers, magenta hued sweet pea plants, wind sown with rambling entwined tendrils displaying their tender beauty as gulls cried overhead and stock doves (Columba oenas) had daintily stepped and ate in that rear garden. On another morning, J had become alerted by a sound of yelping. It had evidently emanated from the revelation of one russet fox, in all its country elegance, following closely on the heels of another. Mesmerised, and with his mind a little sharper from his morning meditation, J had remained seated on that upstairs rattan chair (with the light-blue embroidered Chinoiserie cushions) and, for a few seconds, had sat rapt, gazing at those beauteous passers-by.

Another memory had emerged, from suburban living some decades earlier. It was of his small two bedroom house and its den of foxes living in the back garden. The kits had gambolled near

to, but away from, the hardy cox’s apple tree which, annually, had blessed the garden with roseate apples. J, and his then family, had looked out in the moonlight at that idyllic and transient scene, repeated infrequently and ultimately lost in time.

For a while, a little lost in retrospection, J had remained looking through that window with its blue paint peeling window frame. As the foxes had passed, his line of sight had adjusted to the white-walled cottages, opposite, catching the early sun. Black framed windows had starkly contrasted with the blanched white walls while, all around J, multi-layered bird songs had started up.

The sounds of booming pigeons, perched on the telephone line just outside J’s wood-framed bedroom window (the one graced by delicate soft yellow curtains), had echoed, crows had cawed, and sea-gulls had mewed chokingly cut off to mew again. A little later, the less distinctive calls of smaller birds had been barely heard as the day dawned, but had added to the general sound mélange.

In time, a robin (with its distinctive red breast) had hopped near the dying heads of roses once blush, but then umber in decay, and along the white picket -fence bordering the front garden, .

Still seated, J had continued to look inquisitively outside of the window, his old eyes espying an early-bird cyclist bouncing, earnestly, past and headed for the Old City Victory Dock and a surrendering morning tide.

In that month, fuchsia-hued hollyhocks took pride of place by the cobbled roadside fence, with other colours soon following. Most days, back then, J’s breakfast had been of two slices of wholemeal buttered toast, chunkily topped by partially mashed Cavendish banana. That fruit had been the best banana he could buy, given the circumstances. It not at all like the succulent, indigenous, bananas of all sizes found in his beloved Asia, but had to suffice in his new surroundings.

J had showered and dressed. He had wrangled his ‘Stormgrip’ boots on, and had remembered to slide the house keys into one trouser pocket, his smart phone and leather wallet into the

other. He’d donned his (by then much battered) dark blue trilby. J had gently opened the front door, ducked through the doorway, instinctively double-checking his pockets, and had closed the slightly reluctant (blue painted), wooden door. J had walked, with some arthritic effort, past a clump of large towering daisies, and had exited the property via the white-picket gate, closing it, carefully, behind him.

J had taken his strides up the lane, easing the ache from his body and had respectfully nodded to the blue-shirted septuagenarian female twins, as they passed him at about Ten a.m. The May sun had been pleasant.

A slight breeze had teased what clouds there had been, while a blue sky had spread from over the horse-chestnut and monkey-puzzle trees towards the estuary’s ebb-tide.

J had trod the partially gravelled lane, striding up the slight incline, which had been not long enough, or steep enough, to be called a hill, but nevertheless challenged his ageing bones.

He’d passed Hazel hedgerows, imperial horsechestnut and ancient oak trees, while at the lane’s top, and directly opposite, he had taken the ‘scenic route’, through a rural, slightly overgrown, footpath.

Surprised by rambling bramble bushes (laden with ripe and ripening blackberry drupelets), he’d recalled how, in other places and other times, blackberries would so quickly disappear into the hands of earnest pickers, young and old. But evidently not there, and not then, on that island of plenty.

Back in his 1950’s youth, and in that season, the brambles would have been striped bare of fruit by eager children and planning mothers. Family pies and jams with pectin would have been made with blackberry and the sourish Bramley apple. In that season, blackberry pickers’ hands would have been stained crimson from berry juice, so too their mouths, shirts and blouses marked with bluish lavender with slow-to-disappear yet happy stains. Along that footpath, compacted earth had been lightly covered with fallen yellow leaves. J had slowly traversed that path, weaving around the back of suburban residences and, on one side,

separated from them by an ageing closeboard panel fence. He had been bordered on the other side by hedgerow tangles of ivy, elder, oak and other trees.

Still extant stinging nettles (Urtica dioica), (brought to Britain by the Romans for their irritant properties on arms and legs, warming soldiers in the cold climate) had the potential to make J’s track impassable. However, some kind soul had been through, beating back that potential impediment, allowing J to take pleasure in the sheltered ambiance of that country pathway.

An intermittent sun and shadow had been most welcome as J had ambled through the pathway, and its natural quiet. Quiet except, that is, for the occasional low boom of distant wood pigeons. On his ambling, J had noticed that the scents had been largely of green with, perhaps, a vague acrid hint of far-off farmers’ bonfires then dying, but still lingering in the air.

Before long, the hedgerow had given way to an elderly metal ring-fence. To his left, J had seen the faux wildness of the greenfield burial site, and on his right the headstones which marked a more traditional cemetery. Bypassing Weavers, Stokers, Larks, and myriad names on myriad tombstones J had exited, via a small cedar avenue, into a mixed public housing area.

From the beginning of that footpath, to its end at the cemetery, it was as if J had travelled through time, from the Elizabethan golden era of the 16th century Old City to the 21st century town, with its varying dated houses; the footpath acting as a conduit, bridging time, bringing back childhood memories and thoughts of an Asia which had never been far from his thoughts.

In his recent past, J had taken Spring walks by Xi Hu, that lake of poets and artists, over its three causeways, where numerous temples, pagodas, gardens, with natural and artificial islands, abounded. There had been the aroma of ‘Beggar’s Chicken’ mixing with ‘Nero’s’ coffee drifting across one bridge in particular. A weak sun had glanced off myriad lotus flowers overseen by the poet Huang Binhong’s statue. They had been times when love was strong.

Saturday. It had been the second day of the

town’s annual Regatta (held since July 1838, and originally accompanied by rowing matches and the hunting of ducks). It had been a warming day. Wispy cirrostratus clouds had graced Celtic blue skies. J had walked out of the Old City, with the island’s small harbour before him.

The ebb tide had stranded various craft. In the distance, smaller vessels had been slightly bobbing in their watery lane, and moved with an offshore breeze. J had turned left, out of The Lane, skirting a large, predominantly white, building titled ‘The Old Victory’. Those joined houses had once been the original public house (‘The Leather Bottle’) on that coastal road. That was before the Battle of Trafalgar, and a subsequent name change. A newer pub, further along the coastal road, in 1907 had taken the name ‘Victory Inn’ .

J had ambled past purveyors of ‘Native’ oysters on the estuary side of the road. Piles of shucked oyster discards had attested to the buildings’ trade, and to the great popularity of those establishments.

Back in the November of 1665, and while in London, the diarist Samuel Pepys had written about the barrels of oysters he had acquired from that island’s area. Those eagerly sought after ‘barrels’ were not the size of barrels used for ale, but much smaller, more like tins, or cans, used for that island’s oyster trade and known since before Roman times.

Boatyards and their captive craft, reminiscent of watercolours J had seen of nearby salt marshes and beaches painted by the British artist Eric Ravilious, had sterns facing Besom Fleet. That was where ancient Anglo Saxons had once constructed a fish weir.

Boat names had varied from ‘Timpulla’, ]CK 91], ]CK 935[ (the CK designation being local), to ‘Cheryl Sara’ and ‘Jenny Dee’ and had spoken of loves and lives departed. ‘Jenny Dee’ was a smart, black and white houseboat. Other houseboats had been dotted along that coastal road including crafts titled ‘Spray’, ‘Albacore’, ‘Mulroy’ and ‘Hotspur’ (built in 1874, and landed at the island in 1914). Then there were ‘Gypsy Rose’, ‘Salt Wind’, ‘Anna Maria’, ‘Mojo’ and the intriguing Zeldenrust’ (1903), moored in estuary mud and occasionally floating.

Other vessels, like the houseboat ‘L’Esperance’ (built in 1891) had been the home of a celebrated pianist during the 1960’s and 70s. That boat had still graced that island coastal walk, and observed by J, on his perambulations. ‘L’Esperance’ was rumoured to have been once given to Prince Henry of Prussia, as a gift from his Aunt, Queen Victoria, before being permanently docked on Samphire island.

As he had promenaded the coast Road, the first hint J had of human-tide were maritime enthusiasts (and visiting vendors) setting up their wares in the larger carpark, readying themselves for eager visitors. Safe in their knowledge of sun, heat and a slight estuary breeze.

Further around, younger static craft were hauled up, anchored and had been awaiting for the turn of the tide. An untroubled azure sky and pleasant air had allowed J a clear view of other craft waiting in the perspectival distance. A rising sun had cast its shadows forth like so many mackerel lines. Some waiting boats were red sailed, green and pink hulled, some were blue tarpaulin covered. Larger fishing boats were of darker blue and pink, resting on their trolleys and awaiting the turn the tide, later in the day.

By ‘Monkey Beach’ steps, and in an Elder tree overlooking the estuary, an unconcerned, plump grey, pink and blue pigeon had feasted happily, amongst clusters of joyous elder berries. That bird had nestled itself into the tree, eating as it went, unperturbed by J’s observance. In one nearby, oyster shed, young bronzed male employees had begun shucking the flesh from the shells, with the shed doors open, while eternally hopeful Herring-gulls had performed complex weaving and hopeful dances, above them.

Avoiding other’s merriment, J had assiduously evaded the maritime furore and had taken himself down wooden steps towards the beach. He’d ambled along the still-damp sand, looking out at mud flats, at momentarily stranded craft, glisteningly moist mud and the green algae of a morning coast in the sun.

Occasionally in his promenading, and instead of continuing along that coastal road to its conclusion at Hove hill and eventually the

High Street, J had taken a footpath to a partially damaged board-walk. There he’d forded a small stream (at the salt marsh), and intruded into the conservation area near to St. Peter’s Well. From there he had turn left, and onto the beginnings of the shingle and white sand beach with its jaunty, colourful, beach-huts barely seen in the distance.

In time, August had arrived. Halcyon days had worn on and intruded into that month. J had begun yearning more for his beloved Asia. The British heat, which in the days of his youth had hardly given material for a rosy retrospection, had began to climb into the early 30s Centigrade (80s Fahrenheit) and, being bereft of air conditioning or heat-shifting fan J had begun closing all curtains against the sun’s intrusion.

That UK summer had endured temperatures seldom seen in the British Isles. Some nights it was hot like Asia, with J opening bedroom widows which, unhelpfully, had only allowed hot air in. Alternatively, closing those windows had allowed already stuffy rooms to be even more so.

Later, there had been a false Autumn. A time when deciduous trees dropped leaves too early, vying with the emergence of early crocuses and primroses, which were normally arbiters of an early Spring. Early morning pigeons had been convinced Spring had arrived, judging by the noisy behaviour of two birds, their wings fluttering outside J’s open bedroom window, which had awakened him from a particularly dreamless sleep.

The ominous threat of drought made the gardens, back and front, more resemble a wasteland. J had been finally glad of the ever-green astroturf, although the dearth of flowers had starkly contrasted with the same garden’s profuse flora but a few weeks previously.

Suddenly, the island weather had changed from ferocious Mediterranean days of heat, to dull, British, leaden cloud, and a half-hearted rain’s drizzle. It had not been wet enough to refill the water stocks laid barren by the previous heat, but irritating non-the-less.

Then, it was over.

The accoutrements of his British living had been disposed of. Light, warm-weather clothes had been selected. J had retreated back down the lanes, back down the alleyways, and back down the roads toward the city.

From there, ten thousand miles and thirteen hours had lain before him until, in a humid night, an Asian taxi had deposited him in familiar territory.

Still solitary. J was away from the luscious samphire laced island, the salty mast-made music and the brine scent which had succoured him for a twelve month.

Now, from his metal-grilled, post-colonial, lounge window, J witnesses proud pots of ‘Birds-of-paradise’ flowers, dishevelled ‘Lemongrass’ and an array of Asian green potted herbs and spices, standing on his tiled forecourt.

A most welcome Eastern sun gradually seeps over the terraced house, leaving most of the plants in comfortable shadow for the rest of the equatorial day.

At rest, J leans back into his woven ‘Kerusi rattan’ chair. His feet resting on the ‘Tikar Sarawak’ mat.

Looking out, J remembers his exile, the salty island of samphire and the journey back from there to here. Home.

J smiles an introspective smile, briefly.

He sips from a small glass containing an infusion of local coffee (kopi), evaporated milk and condensed milk (to take the bitterness from the coffee’s robusta beans).

Before J lay new stories/new adventures, in his beloved Asia.

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/samphire_island

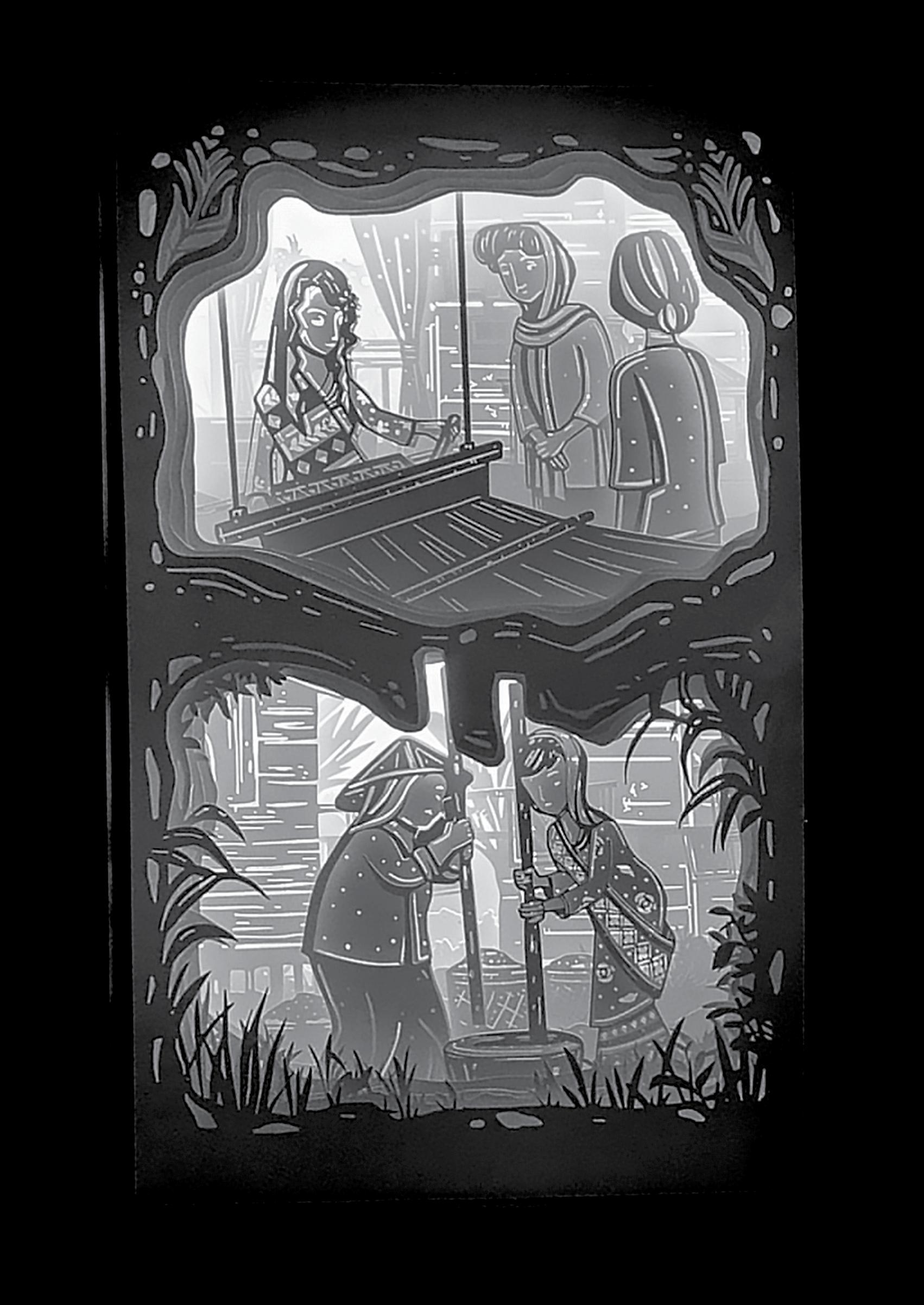

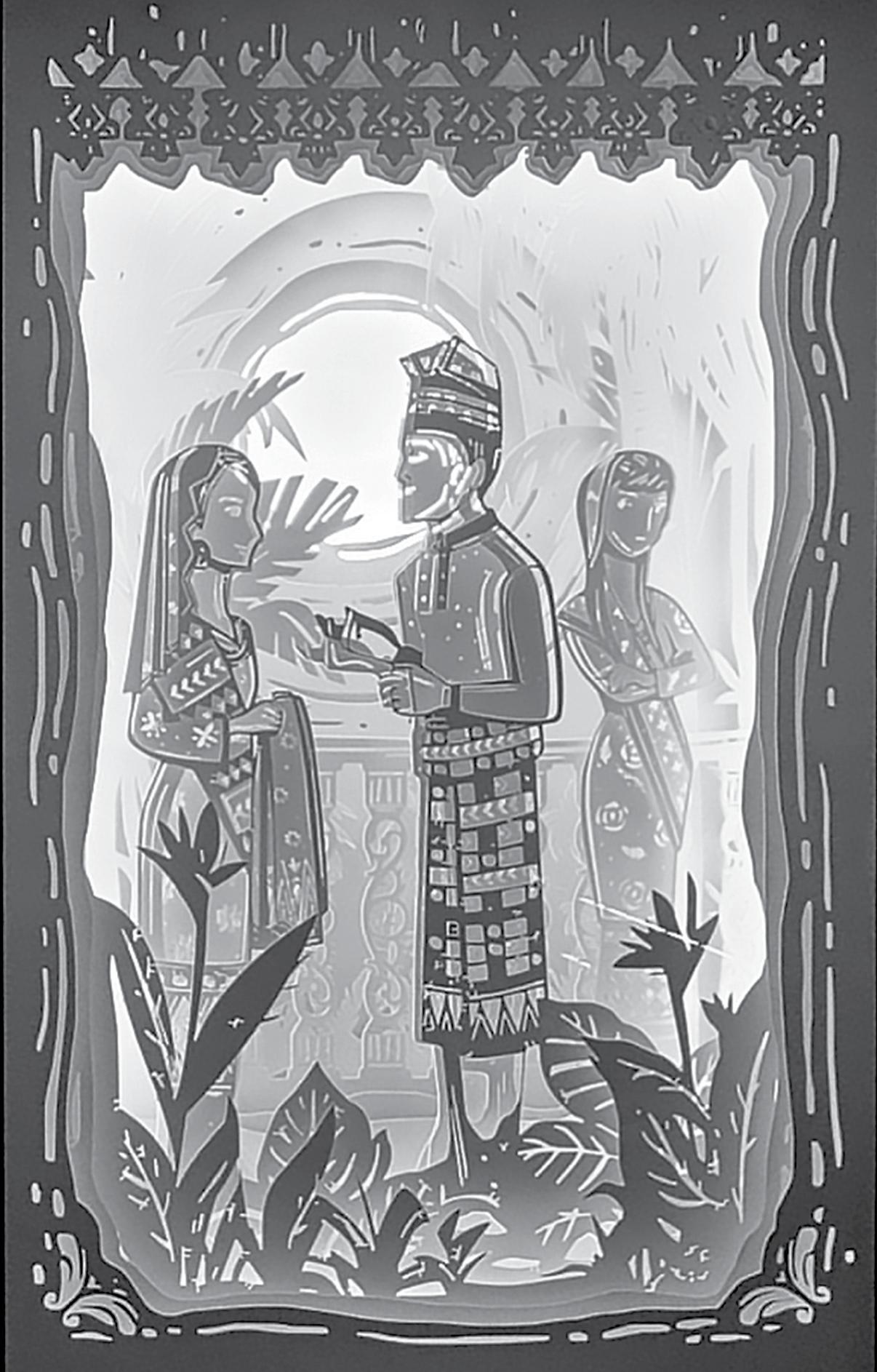

Joy Ng Mei Lok was born in 1996 in Kuala Lumpur. She works as an art teacher whilst pursuing her artistic career since graduating from Dasein Academy of Art in 2016. She has won the People’s Choice Award in 2019 Young Contemporaries. She also took part in an artist residency programme at HOM Art Trans in 2018 and has won 3rd prize in Mixed Media category in Tanjong Heritage National Art Competition. She was also the finalist for several art competitions including 2019 Young Contemporaries and UOB Bank Painting of the Year. To date, she has exhibited her works in 20 exhibitions since 2015 such as in HOM Art Trans with exhibitions such as Wish Me Luck, Young & New, Women Unbounded and Transit 2X2. Aside from that she also exhibited her works in Projek Siang at K5 Gallery, JARI at Bank Negara Malaysia, RRRWARR!!!! at Balai Seni Maybank and Womanhood at ChinaHouse, Penang.

Extracted from AwH22catalogue PDF (rhbfoundation.rhbgroup.com)

To come undone

Time keeper

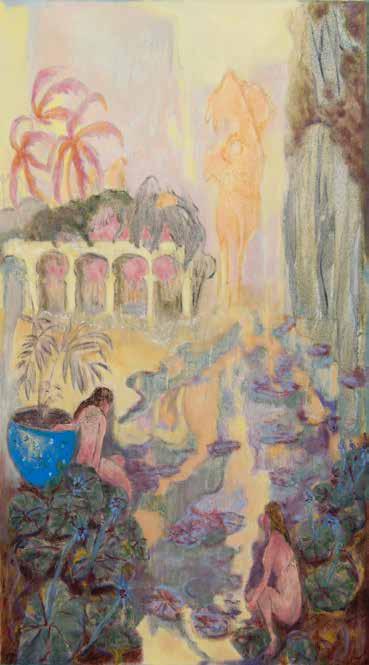

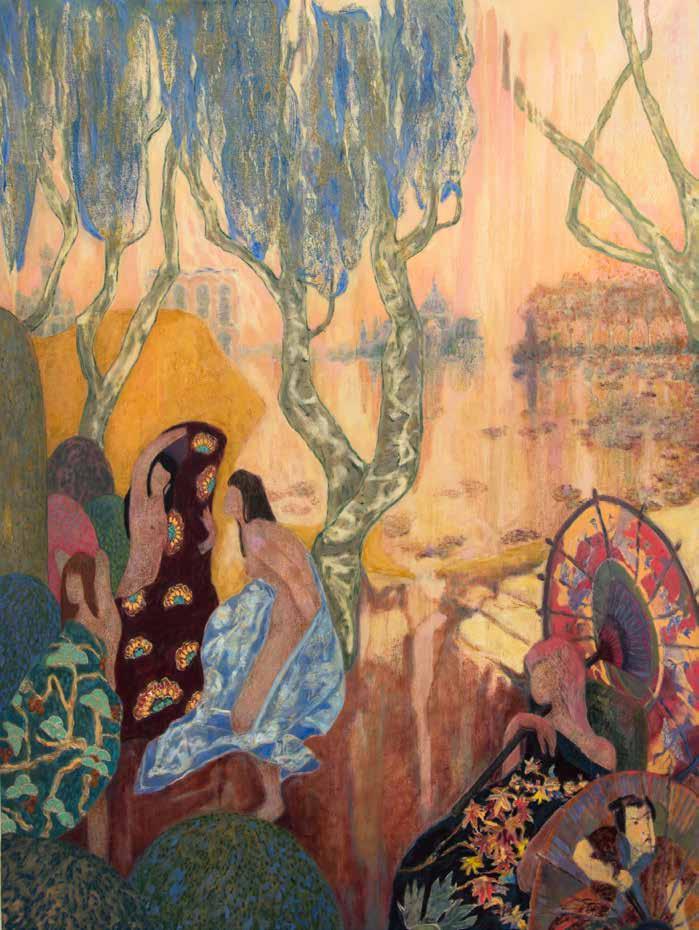

Under my wish fulfilling tree(La couleur des brumes)

Under my wish fulfilling tree(La couleur des brumes)

Statement

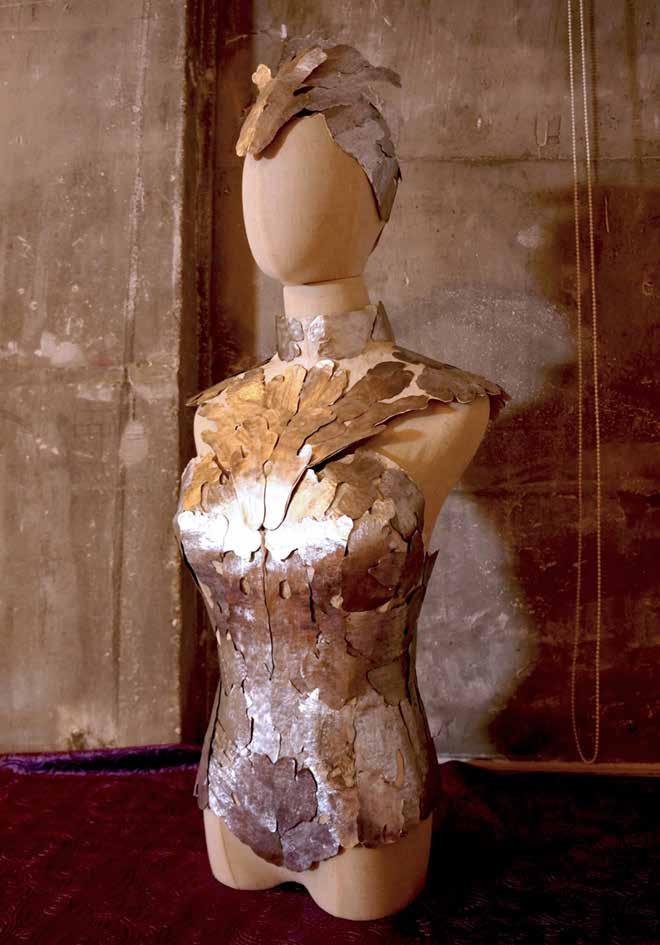

Identifying primarily as a painter, I also explore installations, sculpture, video and photographic works. I work in series, each of which is revolving around one unique pattern.

My artistic practice is informed by a range of personal experiences, including my own sense of belonging across various countries and cultures, as well as my neurodivergent identity. Having spent significant periods of time living and working in France, Canada and China, my creative output reflects my deep engagement with the cultural and social dynamics of these different contexts. Indeed, much of my work explores the interplay between different cultural traditions and their attendant modes of artistic expression, an interest that is born of my own mobile and heterogeneous identity.

My practice is also marked by a sensitivity to the embodied experience of making and viewing art. My exploration of patterns and repetition, for instance, can be read as an attempt to capture the dynamic interplay between the abstract formal qualities of art and their felt, sensory aspects. Likewise, my use of colour and texture is often linked to the emotional and affective reactions that these qualities inspire in viewers.

Overall, my artistic practice is characterized by a nuanced engagement with issues of identity, belonging, and diversity. Through my use of diverse media and techniques, I seek to illuminate the complex interplay between cultural contexts, individual subjects, and the embodied experience of artmaking and viewing. Ultimately, my work serves as a testament to the richness and diversity of the human experience, both in terms of my own complex identity and the larger social, cultural, and aesthetic contexts in which it is situated.

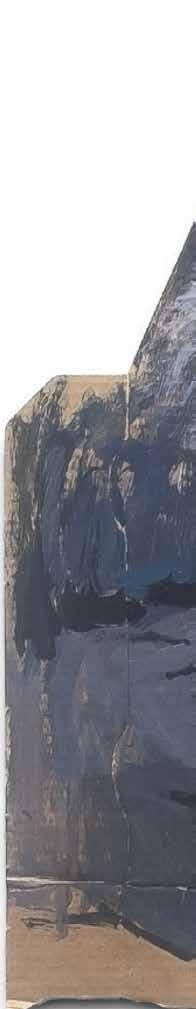

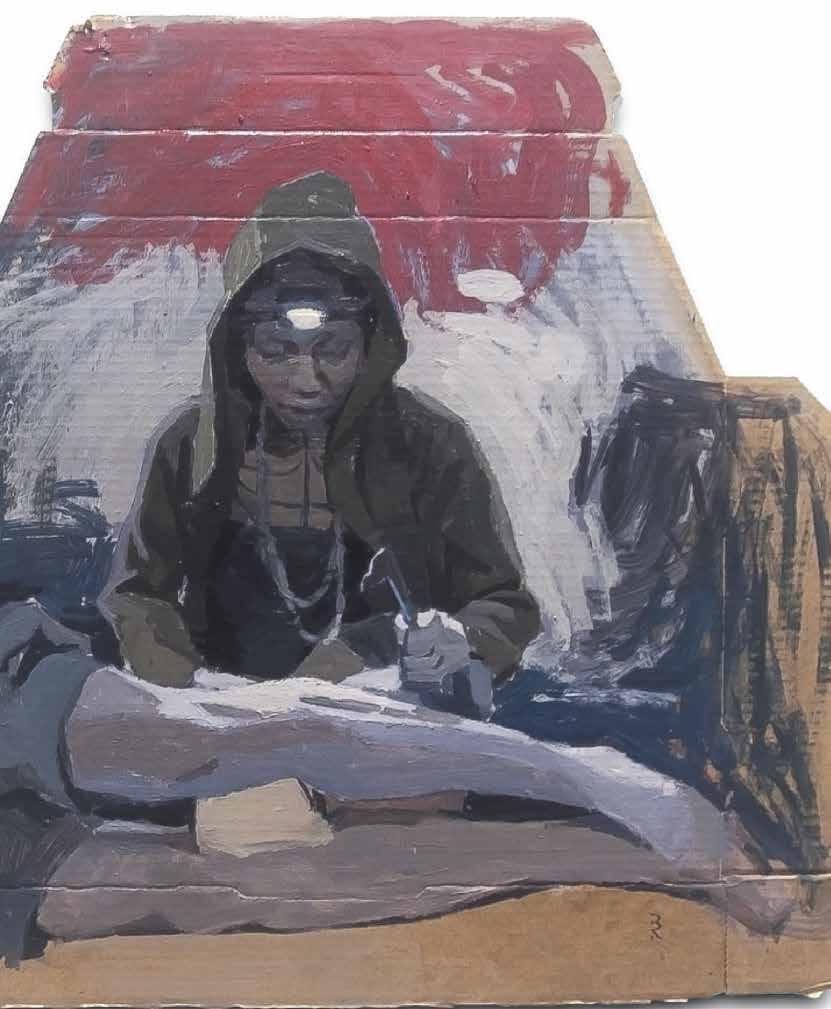

Artist Statement

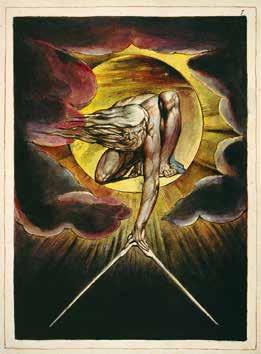

The title "Urizen" comes from The Book of Urizen (1794) by the English writer William Blake (1757-1827), and is illustrated by his own plates. Urizen, in Blake's mythology, represents alienated reason as the source of oppression. The book describes Urizen as the "primeval priest" and narrates how he became separated from other “Eternals” to create his own alienated and enslaving realm of religious dogma.

There are two possible derivations of the name Urizen. It comes either from ‘Your Reason’, meaning ‘accepted wisdom’ – commonly accepted, although not by Blake, or from the Greek verb ‘horizein’, meaning ‘to limit’.

Blake's invented mythology describes Urizen as “Creator of Men”, a god of immense power who invented a repressive web of laws and religion based on reason. Urizen is always represented as a bearded old man, who sometimes carries books of divine law and measuring instruments to create and constrain the universe, architect's tools with which to create but also limit the universe.

Viviente's Urizen (2023) is represented as a

female painter. This personification of Urizen as a woman explores the forgotten balance between history and gender, a main topic in Viviente's artistic research.

The Urizen woman is sitting and has a tool or instrument in her hand on a background of canvases and paintings. As in the compass of Blake's Urizen, according to the explanations, "is more than an instrument of wisdom and measurement, coming to be a kind of symbol of a lightning bolt capable of illuminating a world plunged into a state of night dark and stormy". The colours of the Urizen woman are those of lightning, red, lilac, yellow, green, fuchsia, orange, pink, vivid colours, full of strength and dynamism. Like Pop art is characterized by vibrant, bright colours.

The focus on Urizen emphasizes the chains of reason that are imposed on the mind. Urizen, like mankind, is bound by these chains. But the focus on Urizen also reminds us of the necessity and benefits of imagination. For Blake, Urizen's laws limited energy and crushed the imagination. He believed in the power of the imagination, he also believed in the spirit of revolution and freedom. The Urizen woman too. She embodies these concepts in a sort of contemporary allegory.

Viviente, P. URIZEN. Artist Statement. Published in the online Exhibition Art & Photography 2023 11th Edition, Art Web Gallery, June 26-October 7, 2023.

Critical texts

Pilar Viviente

“If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” (William Blake)

Pilar Viviente, Spanish visual artist, presents her latest series "Urizen" inspired by the mythology of William Blake, at the CAOS exhibition by M.A.D.S. Art Gallery. In this new body of work, Pilar Viviente explores gender themes using evocative symbolism and fluorescent colours that blend to create a unique visual experience. Blake's mythology depicts Urizen as the "Creator of Men", a powerful deity who imposed repressive laws based on reason. He is consistently portrayed as an elderly bearded figure wielding books of divine law and measuring instruments to create and constrain the universe. Pilar Viviente chooses to delve into Blake's legacy, contributing to the investigation of crucial themes. Her "Urizen" series sheds light on the interconnectedness between men and women, examining the history of gender and the frequent neglect or denial of the feminine universe. Furthermore, the focus on Urizen highlights how the chains of reason can stifle the human mind. The artist aims to remind us of the fundamental necessity and benefits of imagination. Just as Blake suggested, Urizen's

laws limit creative energy and suppress imagination. Nonetheless, Pilar Viviente believes in the transformative power of imagination as a means to break free from the chains imposed by reason and to explore new possibilities and perspectives. Viviente's artwork incorporates complex symbolism, emphasizing the duality between light and darkness, masculine and feminine, history and imagination. The female figure of Urizen becomes the centrepiece of a contemporary representation, where fluorescent colours resulting from post-production photography merge to convey vitality and dynamism. This distinctive visual style, influenced by Pop Art, accentuates the vibrancy of the messages. Through the "Urizen" series, Pilar Viviente invites the audience to contemplate the importance of rebalancing gender power dynamics in society and to explore imagination as a tool for personal and collective liberation. The contemporary allegory represented by the female version of Urizen proves to be a powerful symbol of hope and transformation, underscoring the significance of sustaining the revolution and the struggle for freedom.

Art Curator Francesca Brunello

Brunello, F., ed. "Pilar Viviente". In: CAOS International Art Exhibition, P. 25-28. Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized by and presented at Milan, Fuerteventura and Times Square, August 10-16, 2023.

In “Augural Ritual” (2022) Pilar Viviente refers us to key works of the s. 20th, such as ‘Nu descendant un escalier’ (1912) by Marcel Duchamp or ‘SelfPortrait as a Fountain’ (1966) by Bruce Nauman. We find ourselves before a self-portrait in the artist’s studio, in which she appears seated with photographic utensils in her hands and wearing her mother’s shoes in a vindication of her status as a woman and as an artist, as a miracle worker, augur and priestess who controls the creation process. The serialisation of the image creates a kinetic effect highlighted by the use of colour fracturing it. Her enthronement, the weapons in her hand, the exaltation of her divine lineage and the colours of the lightning bolt make up an iconography that could link the artist’s own representation with that of the female divinities. However, the artist recreates the figure of Urizen, created by the poet and visionary William Blake, who conceived him as the creator of humanity and a legislator guided by reason that gave rise,

however, to oppressive laws. The feminisation of the character constitutes a call for imagination beyond the rational and the overturning of the patriarchal order.

Miquel Bardagil Art criticism

Bardagil, M. El sagrat i el profa. Elche: Universidad Miguel Hernández, 2024. Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized by and presented at the Roman Temple of Vic, December 1, 2023-14 January, 2024.

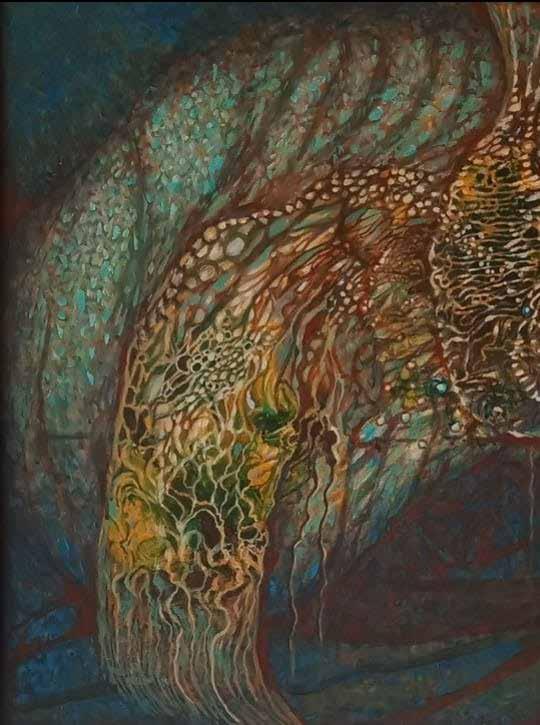

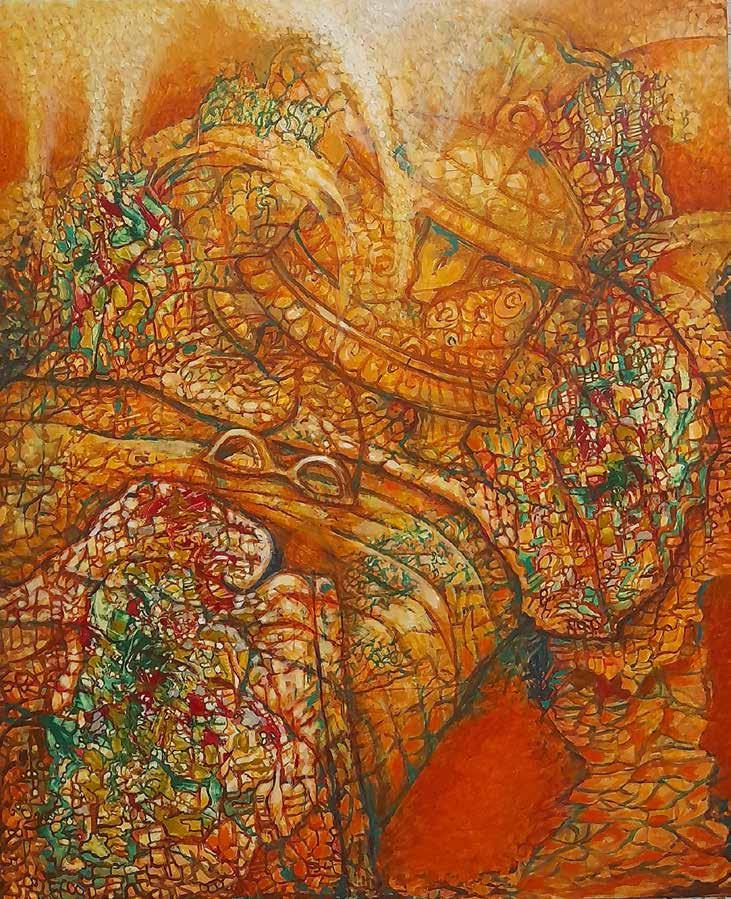

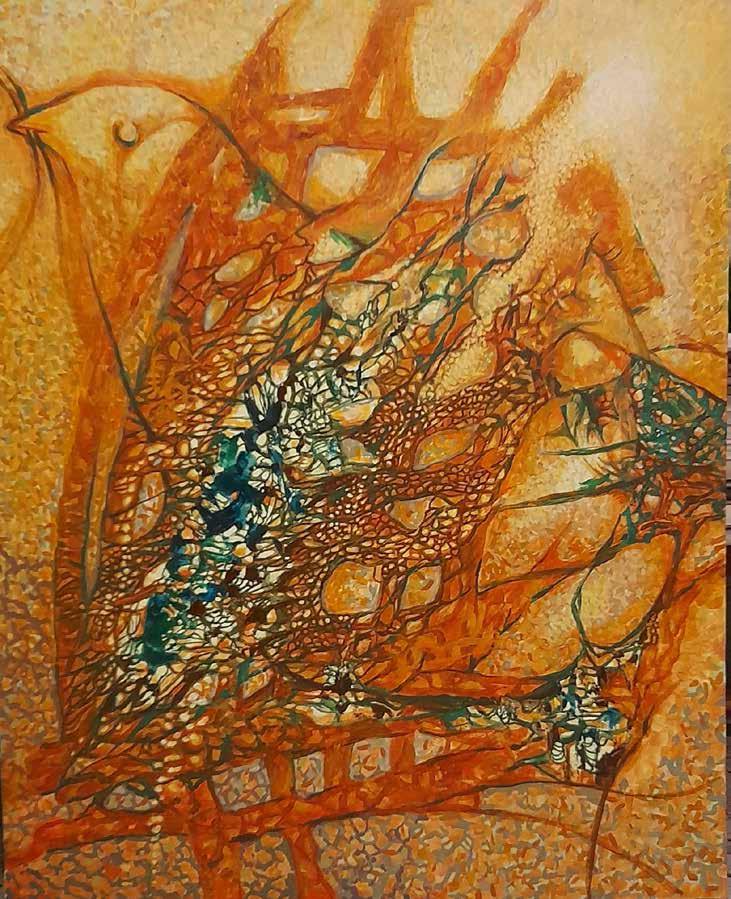

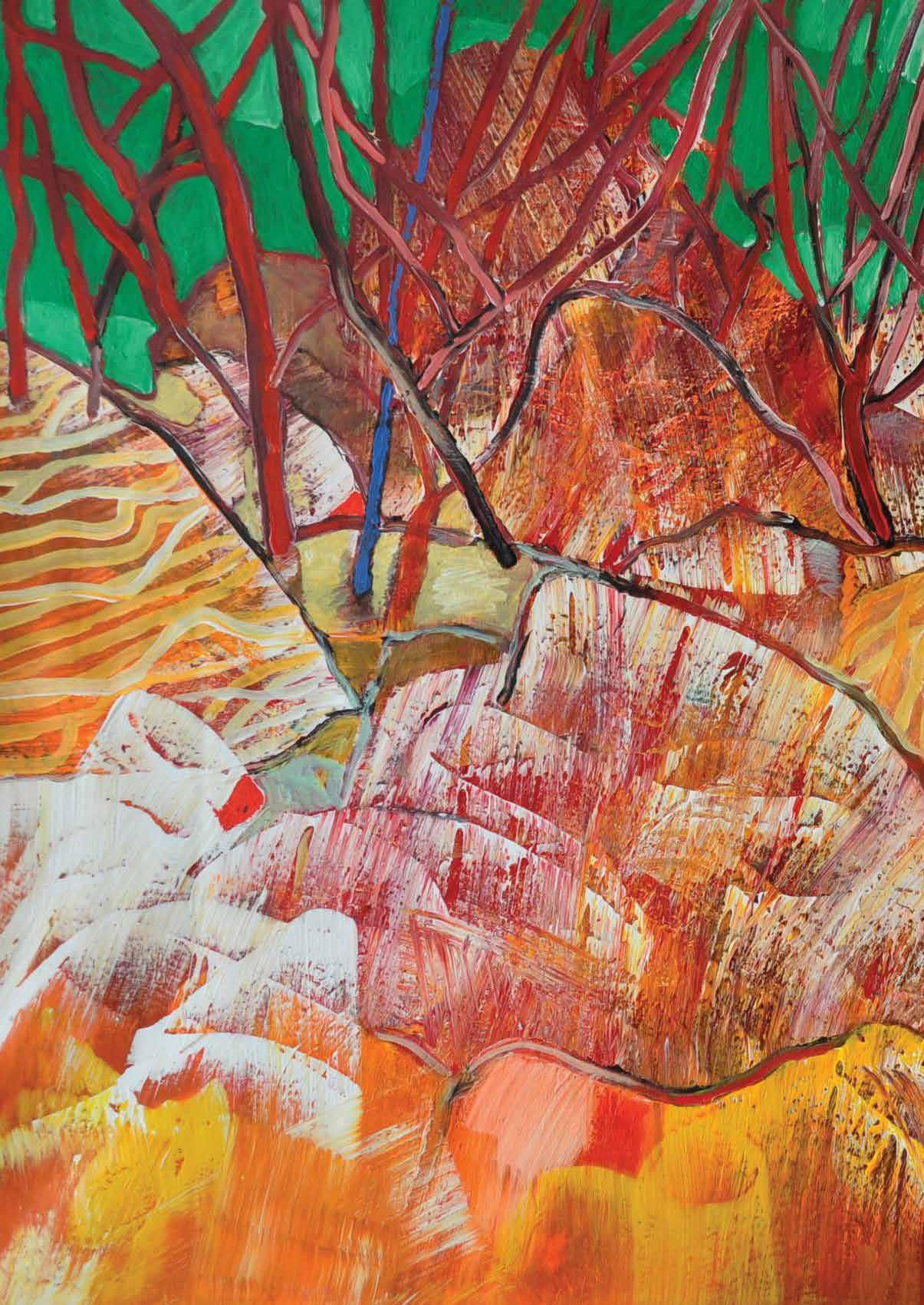

I search for my self identity and self distinguished motive in order to make a something else. The Earth moves around the sun as usual from the times beyond our reach, simultaneously nature and harsh reality go hand in hand and touches the strings of mind as if I am standing alone by the side of various thoughts...........

So I travel. Travel and travel, explore the central Indian rock, cave, prehistoric art and culture. I travel noticing exotic auras around tribal (Santhal, Birhor, Chenchu, Kanikkar, Urali, Riang, Nicobaress and Onge) Folkart. Which remains at the aesthetic and philosophical levels. Then the matrix of experience exploration of my internal and external environment excavates the living moment in search of long forgotten ancient life and culture. Travelling I keep paintings in my heart and mind. The process will then go on my canvas. Ancient life and culture expresses a passionate empathy between man and animal at the visible level. Man and his own humanity is at the invisible level.

Agricultural practices and socio-economic (reality) and material conditions influence the choice (in the Vedas for instance, the horse, the vehicle of the Aryans, is the pre-eminent sacrificial animal. Birds should be sacrificed for different reasons and occasions). From today’s perspective we can deplore the barbarity of animal sacrifice. Yet if we see the practice from the viewpoint of Neolithic times the sacrifice assumes an awesome significance. At the more ordinary level it is nothing but an offering made to a superior being, either as a giving of thanks or to placation. This custom continues in our social relations even today. However, there is a basic difference between giving gifts as practised, and the

sacrifice off living beings. The difference points no doubt to the cruelty of the practice.....

Deep and strong realisations of human, animal and nature’s, communication make the impact of all human religious impediments in our contemporary society. I see My World is animistic, and that world see things with life………!

I try to find, and create, my own world (in relation to Europe, Latin America, Africa and Central Asia) mainly as a foundation of inspiration. My creations come from Indian cave and rock paintings, and also folk and primitive terminologies. My paintings are eccentric patterns of interlocking lines, and musical gesture.

I think through my aesthetic essence, through colours like red, green, yellow, orange, lemon yellow, sap green, vermilion tint, burnt umber, blue, stone black etc.

My compositions are unlimited. They infuse power from ancient life and ancient culture. Hence my experimental series - “Ancient Love”, and others ……………… !

Sambal Blachan prawns

Sambal Blachan prawns

Fruits and vegetables on offer from local markets

Fruits and vegetables on offer from local markets

As it turned out, Kuching was simply the best place to find a great number of restaurants, and cafés, serving reasonably authentic Dayak cuisine, both to curious newbies like me, and to the gastronomic cognoscenti. Here are three that I sampled.

That first day, more than ready for lunch, I had struck lucky. By chance, I’d discovered a local cafe called ‘Pinggai’ (‘plate’ in the Dayak-Iban languages). It was conveniently down Kuching’s Carpenter Street, and close to Hotel Borneo (where I was staying). That Dayak cafe has been run by two Iban sisters, Cynthia Rendong Banda, and Ellis Sebai, who had mentioned (in an interview with Dayak Daily) that…

“Our signature dishes are influenced by traditional Dayak flavour, which comes from Iban and Bidayuh culinary style of cooking. Dayak food is very subtle and honestly, very hard to cook, thus it is a challenge

to acquire the exact taste,”

My Bidayuh companion and Kuching guide (who knew about these things), suggested that I try the ‘Fragrant Red Rice’ (Beras Merah in Malay) planted mainly by the Bidayuh community in Sarawak), the Dayak ethnic chicken ‘Ayam pansuh’ (chicken and tapioca leaves cooked in a bamboo tube), Midin (local edible ‘fiddlehead’ fern) salad and ‘Daun Empasak Goreng’ (fried Tapioca leaves) as an overall introduction to Sarawak’s ethnic cuisine. From the very first forkfull of these exciting new tastes, I was hooked.

Obviously, I wanted more.

As it turned out, Kuching proffered some other places revealing ethnic Sarawakian cuisine. After an extensive Google search, one name had shot forward. It was that of the restaurant ‘Lepau’ (meaning ’farm hut’ in the ethnic Kayan language). Why? Because, in 2018, that restaurant had won the ‘Best innovative ethnic restaurant award’ at the 20th Malaysian Tourism Awards, and the ‘Sarawak culinary excellence award’ at the Nyamai Sarawak Gastronomy Awards ceremony, in 2023. I really did have to go and sample their food myself. The Lepau restaurant, incidentally, is run by Livan Lah, and can be found along Ban Hock Road, Kuching.

Over a couple of visits to that exquisite restaurant, I was very happy to taste, firstly, Baby Pink (the pink syrup drink known in Indonesia as Ayer Bandong) with Longan; Deep Fried Sago Grubs (a delicacy); Kantan (Torch Ginger) Mixed Chillies, and Tampoyak (salted, fermented durian flesh) with Fish soup.

On the second visit we dined on Terung Asam

Salai Soup (or soup made with a yellow, sour, eggplant, combined with dried, salted fish); Cangkuk (an indigenous sweet leafy vegetable) cooked with Egg; Fish Umai (sliced raw fish with a mixture of onions, chillies, vinegar, salt and lime juice); Jungle Tree bark drink (aka bakas); Pandan (leaf) and Lemongrass (stalk) drink, the Dayak red Bario rice wrapped in a Itun Sip leaf, and Tapai (mixed local yeast with glutinous rice, fermented) served with Ice-Cream.

Down Kuching’s Wayang Street, there was ‘The JollyPit Bar and Grill’, conveniently close to the Borneo Hotel. I had gorged on large Bar B Qued prawns, which were fairly stuffed with the pungent and pleasantly spicy Sambal Blachan. That dish was at once tangy, sour and spicy. On the second occasion I tried, and was pleasantly surprised by, the ‘Jellyfish Umai’.

According to Wikipedia….

“Umai is a popular traditional native dish of the

Melanau people in Sarawak, Malaysia, which is usually eaten by fishermen. Umai is a dish of sliced raw fish with a mixture of onions, chillies, vinegar, salt and lime juice.” In my case, the dish was actual jellyfish, instead of regular fish.

In its blurb, JollyPit asked us to…

“Explore the rich flavours of Dayak cuisine and dive into the unique tastes of Borneo with our new menu items. From the smoky aromas of Manuk Pansuh to the zesty freshness of Umai, every dish tells a story of tradition and flavour.”

Sambal Blachan prawns

Jellyfish Umai

Sambal Blachan prawns

Jellyfish Umai

Fresh (green) pepper

Blimbing

Fresh (green) pepper

Blimbing

Midin ‘Fiddlehead”fern

Midin ‘Fiddlehead”fern

Chillies and tomatoes

Chillies and tomatoes

Mangoes

Mangoes

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/samphire_island

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/being_here_now_

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/love_s_texture

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/malim_nawar_morning

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/on_the_island

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/cambodia_chill_re-issue

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/lotus

https://issuu.com/martinabradley/docs/remembering_whiteness_booklet

Martin Bradley is the author of a collection of poetryRemembering Whiteness and Other Poems (2012, Bougainvillea Press); a charity travelogue - A Story of Colours of Cambodia, which he also designed (2012, EverDay and Educare); a collection of his writings for various magazines called Buffalo and Breadfruit (2012, Monsoon Book)s; an art book for the Philippine artist Toro, called Uniquely Toro (2013), which he also designed, also has written a history of pharmacy for Malaysia, The Journey and Beyond (2014, Caring Pharmacy).

Martin has written two books about Modern Chinese Art with Chinese artist Luo Qi, Luo Qi and Calligraphyism and Commentary by Humanists Canada and China (2017 and 2022), and has had his book about Bangladesh artist Farida Zaman For the Love of Country published in Dhaka in December 2019.

Canada 2022