FREDDIE TIMMS NGARRMALINY

2 - 25 February 2023

Opening Reception 2:00 - 4:00 PM 4 February 2023

The exhibition will be officially opened by Professor Marcia Langton, AO Jack Thompson, AM will provide recollections of his time with Freddie Timms

Presented in association with the Estate of Freddie Timms

MAR TIN BROWNE C ONTEMPORAR Y

15 HAMPDEN STREE T PADDINGTON NSW 2021 TEL: 02 9331 7997 MOB: 0414 881 999 info@mar tinbrownecontemporary. c om www.mar tinbrownecontemporar y. co m GALLERY HOURS: TUESDAY SAT URDAY 10:30AM - 6PM SUNDAY MONDAY BY APPOINTMENT

Ngarrmaliny: visionary, artist, and Gija leader paints his Country and history

Ngarrmaliny, known in English as Freddie Timms (1946-2017), was a Gija artist of great renown. Gija Country lies in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia. Timms learnt about ritual art traditions in the company of Gija leaders, including his uncle, the great Bow River boss, Timmy Timms — his ‘father’ in Gija tradition, and a critical role model, ritually and socially — and Rover Thomas, whose paintings inspired the art movement of the East Kimberley.

The fifteen paintings presented in this exhibition provide a rare opportunity to see a large body of Timms’ artworks. Many reveal dark histories, recounting with elegant precision the invasion of Gija Country, and the murders and drama that followed. But they do much more also: they celebrate landscapes, both topographical and spiritual, and they tell the Ngarranggarni — sacred Gija narratives — that Timms learned from his elders.

Freddie’s Gija name was Ngarrmaliny and his skin or subsection name was Janama. He was born at Police Hole on Bedford Downs Station. In his childhood, he lived with his parents at Bow River and Lissadell Stations. Like his uncle/father Timmy Timms, he also worked as a stockman, handyman and fencer on stations. During his time working as a stockman for the white pastoralists, Freddie would tend to cattle herds, working in conditions that were little different from slavery.

In the 1980s, Freddie lived at Frog Hollow, south of Warmun (formerly known as Turkey Creek). The Waringarri Arts organisation in Kununurra brought canvases to the artists of Frog Hollow, who included Jack Britten, Rover Thomas, Hector Jandany and George Mung Mung. Freddie asked for canvases and developed his unique vision based on the Gurrir Gurrir style initiated by these ritual elders.

He painted expanses of colour lined with white dots, depicting the ‘bird’s eye’ view of Country where he had lived and worked. The paintings depicted the physical landscapes of his childhood, youth, and adulthood on the stations of the Kimberley, with their black and red soils, sand formations, rugged ranges and hills, creeks, and water holes, as well as the roads and

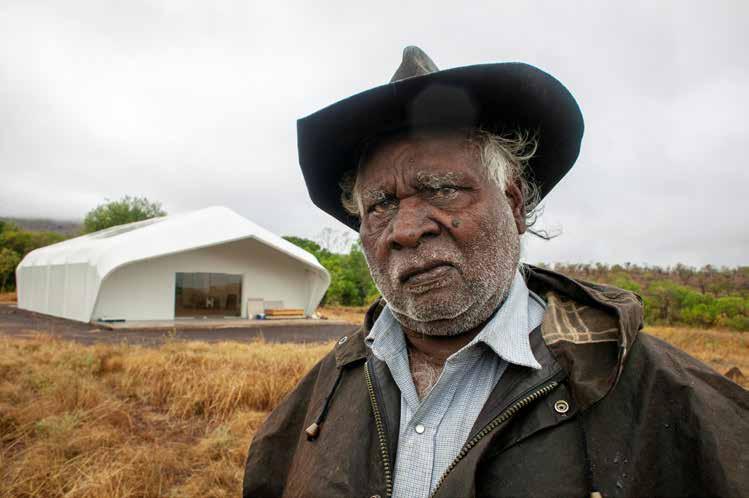

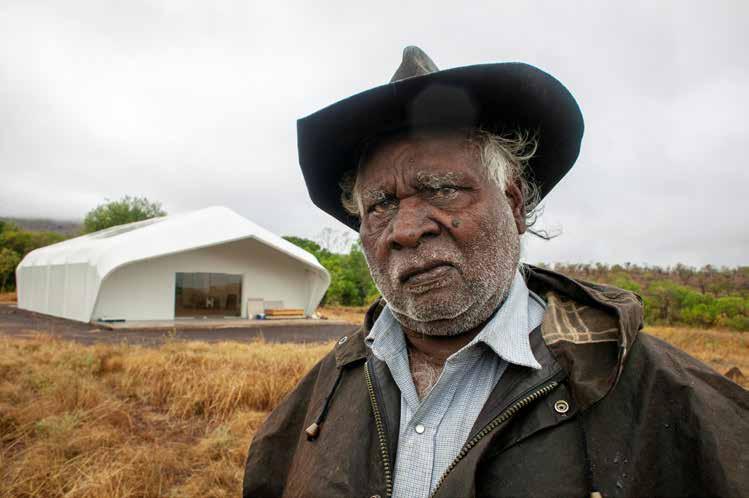

Freddie Timms as Ned Kelly, 2004

Photograph: © Peter Eve

stockyards of the pastoral leases. But equally importantly, his images depict the Gija spiritual and historical landscapes of the East Kimberley.1

Rover Thomas was the first artist from the East Kimberley to achieve widespread fame. However, Thomas was not born on Gija Country, he was from much further south in Kukatja Country. Thomas spent his last thirty years living in Warmun Community on Gija Country, hence the telling of so many art histories hinge on his encounter with the ceremonial life of the Gija. Shortly after moving to Warmun early in 1975, Rover Thomas ‘found’ or ‘was given’ the ceremony of the Gurrir Gurrir. His relationship with the Gija was as a full traditionally adopted son and one who earned his status by learning their songs, dances, ceremonies and sacred designs.

The Gurrir Gurrir ceremony provided the stimulus for art works. Plywood boards were painted with sacred ancestral designs and held on the shoulders of the male dancers during ceremony to complement specific verses of the Gurrir Gurrir song cycle. This ceremony was first performed in Warmun in the late 1970s with boards which had been painted by Rover Thomas and his classificatory uncle Paddy Jaminji. Freddie Timms worked with Rover Thomas at both Bow River Station and Texas Downs, and helped Thomas paint the boards for Gurrir Gurrir ceremonies.

west of the homestead, that the Station Manager, Paddy Quilty led a group of vigilantes to murder Gija people and their families using strychnine poison. Paddy Bedford, known as Goowoomji, was also born there, and it was Paddy Bedford’s dream of a joonba ceremony that recalled this terrible massacre. The bodies of the murdered Indigenous people, most of them Gija, were piled up by the white men who had poisoned them, and burnt in large pyres.

The survivors were forcibly removed to the government station at Violet Valley and later returned to work at Bedford Downs. Timmy Timms, Paddy Bedford and Freddie painted these massacre sites to remember their ancestral spirits and the terrible deaths of their forebears. There were at least eleven massacres of this nature in this area alone.

In 1996 Freddie Timms met gallerist Tony Oliver in Melbourne and invited him to come to Kununurra and work with him. They collaborated for the next twelve years. In at least one important respect, Freddie’s legacy is even more legendary than Rover Thomas’ among his people in the East Kimberley region. Freddie had a vision for the Gija people as a self-determined and self-organised community, and he was resolute throughout his life in striving for a strong Gija community, able to continue their rich traditions.

These ceremonial boards were seen by many, including Mary Macha, the Manager of Aboriginal Traditional Arts, Perth, who first began to market Thomas’ and Jaminiji’s work. A few years later Thomas began to paint for Waringarri Aboriginal Arts in Kununurra and within a decade Thomas became a household name as the first Aboriginal artist to represent Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1990. These works, initiated by ceremony, were the first from the region to attract the attention of curators and collectors in the global market. Although Thomas was given the ceremony of the Gurrir Gurrir, Freddie Timms was the direct heir to this sacred design patrimony.

Freddie’s uncle/father, Timmy Timms, was born at Bedford Downs, and it was here, in retaliation for the killing of one milking cow near Mount King, an Emu dreaming place to the

1 Freddie Timms. Kate Owen Gallery. https://www.kateowengallery.com/artists/Fre164/Freddie-Timms.htm. Accessed: 5 January 2023.

In 1998 Freddie collaborated with his fellow Gija artists Paddy Bedford, Rusty Peters, Hector Jandany, Rammey Ramsey, Phyllis Thomas, Peggy Patrick and Goody Barrett, along with Tony Oliver, to establish Jirrawun Arts. Jirrawun means ‘one’ and represented the unity of the artists in their purpose of achieving cultural maintenance and regeneration in a context of economic independence. This vision was articulated by Timmy Timms as the Warlpawun Vision.

By 2004 Jirrawun Arts had become incorporated as a company and Freddie Timms was the inaugural President. The first board meeting took place on 25 May 2004 with Patron Sir William Deane giving the welcoming address. CEO Tony Oliver and Board members Freddie Timms, Rusty Peters, Paddy Bedford, Helene Teichmann, Brendan Hammond, Ian Smith together with Secretary Frances Kofod were present in person; Michael Naphtali and I were present by telephone link-up.

In his discussion of the work of Ngarrmaliny, Tony Oliver observes that he rarely revealed Ngarranggarni in his paintings because of his deep respect for Aboriginal law:

“… the majority of his work … depicts the Country that he worked as a stockman mustering cattle, and shows the topography by way of hills and creeks. Paintings become a mapping of memory, and the artist often speaks nostalgically about friends and events in the landscapes depicted. Ngarrmaliny’s paintings exist in temporal dimensions. European time imprints its historical clock on Gija land — roads, homesteads and murder sites — with the older time dimension and its subject matter remaining unseen.”2

This strict observance of traditional laws is common among that generation, and Freddie, like Timmy Timms and Paddy Bedford, similarly observant, worked in abbreviated signs and codes that referred obliquely to sacred narratives and hidden histories.

Freddie was more than insulted when Keith Windschuttle published his book, The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, in which he effectively denied that there had been massacres in the Kimberley region. Sir William Deane, famously on the High Court bench in the Mabo case, had become the Patron of Jirrawun and said to the Gija people that he was sorry that their forebears had been victims of these massacres. Windschuttle attacked him in the media. Freddie was directly descended from the survivors of the massacre of the Aboriginal people living at Mistake Creek at the hands of white vigilantes. He had heard his uncle’s stories and he discussed with his Jirrawun fellow artists and Tony Oliver a method for countering the lies of Windschuttle.

In 2002, the Blood on the Spinifex exhibition at the Ian Potter Museum of Art was their answer. Ten Jirrawun artists presented twelve paintings depicting their history. Timmy Timms had told Tony Oliver about the Mistake Creek massacre and this account was retold to the journalist Debra Jopson of The Sydney Morning Herald in her article about the exhibition, aptly titled, ‘Landscapes in blood’:

“Timms’ massacre account is very similar to the story found in 1915 police records. Timms spoke of a group of Aborigines camped in a gorge near Mistake Creek homestead. The group ate a cow after their dog had attacked it. As punishment, two white men, Bob Beattie and Mick Rhattighan, shot the Aborigines in the gorge. They were helped by an Aboriginal station hand from Darwin, Joe Winn. A fleeing Aboriginal survivor told the Turkey Creek police, who couldn’t find their horses straight away and took a while to move out. Meanwhile, the remaining Aborigines in the gorge were chained up and moved to Mistake Creek. The police arrived just as the last shot was fired in their massacre. “White people call it Mistake Creek. We call it Gurtbelayin the place where many were killed at one time,” said Timms. In notes to his painting, Chinaman’s Garden Massacre, Rusty Peters has said how his uncle, a survivor, “went down afterwards to look for them. `Where are my people? Where are my people? Where?’ The white men had killed them all, poor things.” Timmy Timms’s bold black and brown painting Bedford Downs Massacre has a white dotted circle in one corner, which he once explained represented the place where a group of Aboriginal people were poisoned and burned by white men. Timms’s sister Peggy Patrick was instrumental in taking a corroboree about this massacre to the Melbourne stage recently in the production Fire Fire Burning Bright. Timms’s [nephew] Freddie, chairman of the artists’ co-operative, said of Windschuttle: “He don’t know nothing about killing black people. It’s what white people have done.”

Authors like Windschuttle will have their rebuttals cut out for them in years to come. Gija people giving cross-cultural training to Argyle Diamond Mine workers in their region gave them “chilling accounts” of 11 massacres there, the Aboriginal academic Professor Marcia Langton said in her catalogue notes for the exhibition. “We are finding more and more massacres now they are finding the confidence to speak,” says Oliver. Freddie Timms this week issued an open invitation to Windschuttle to visit the massacre sites with the Gija people and to hear their stories. “He wants to come; he can come and look if he reckons no blackfellas got shot. Let him come and have a look. We’ll show him around.”3

2 Tony Oliver, Blood on the Spinifex (Parkville, Vic.: Ian Potter Museum of Art, 2002) p.10.

3 Debra Jopson, ‘Landscapes in blood’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 December 2002.

An account of this is retold by Quentin Sprague whose book, The Stranger Artist, on the Jirrawun Arts collective and the meteoric rise to artistic fame of its members, is a fascinating narrative.

In his interview with Jopson, Oliver explained Freddie’s approach to the lies that Windschuttle had peddled:

“The whole thing is about an oral history versus a written history and that’s what this show is partly discussing,” says Oliver. “When you can’t read and write, your main history is through oral history, the passing down of stories.”…He has heard the oral history of the north-eastern Kimberley killing fields by night around their campfires. Oliver believes it took great courage to divulge the stories to him and then to other whites. Many had not been told before for fear that it would lead to a bullet through the head of the teller. “Who can the oral historian trust to tell of murder against his people other than his own people? Retribution from the white man amongst Indigenous Australians is not an abstraction it is part of our shared history,” Oliver writes in the exhibition catalogue. The weight to be given to oral history is at the heart of the debate which flared recently between Windschuttle and Deane over whether white people killed Aborigines at Mistake Creek in the Kimberley in 1915. Windschuttle said Deane had got it wrong when he apologised to Kimberley Aborigines over the massacre. Police records showed it was “a killing of Aborigines by Aborigines”. Deane wrote in reply that “one simply cannot ignore the Indigenous oral history” and that police throughout Australia were reluctant to file adverse reports against white settlers. When news of the academic debate filtered to the Kimberley, the old people who had been handed down stories from three eyewitnesses about their forebears being killed at Mistake Creek by whites were frustrated over their inability to reply. They could not read or write. But over the past few years, they have been finding new ways to tell their stories to city audiences. The exhibition is part of their answer. “How is somebody who has an oral history meant to be involved in this debate? It’s basically a European-dominated paradigm that these people haven’t been able to enter,” says Oliver. “So they entered this debate through their own culture, through painting.” Linguist Frances Kofod has written down in English the stories she took from them in Gija and Kimberley Kriol. They are painful.

The late Timmy Timms painted a boab tree near Mistake Creek, where he said his mother’s family had been murdered. It was at this site that Deane said “sorry”.“4

Despite Windschuttle and the ‘culture wars’ of that period, historians and others have unearthed the evidence of a violent frontier, and evidence, both oral and documentary, has been presented in native title claims throughout the area. The invaders arrived between 1885 and 1894 and set up cattle stations. The first town in this area was the port of Wyndham. From 1886 it provided sea access for ships to transport cattle. There was a gold rush to the west and hundreds of miners rushed to Halls Creek, near the borders of the Gija and Jaru homelands. Indigenous people were massacred or removed from their lands, usually in chains, but survivors stayed in their country working, often in conditions of slavery, as ‘station hands.’ It was a ‘rolling frontier’, to use Henry Reynolds’ expression, and for more than a century, the peoples in the Kimberley encountered invading pastoralists, police, vigilantes, missionaries and, eventually, settlers, and mining companies.

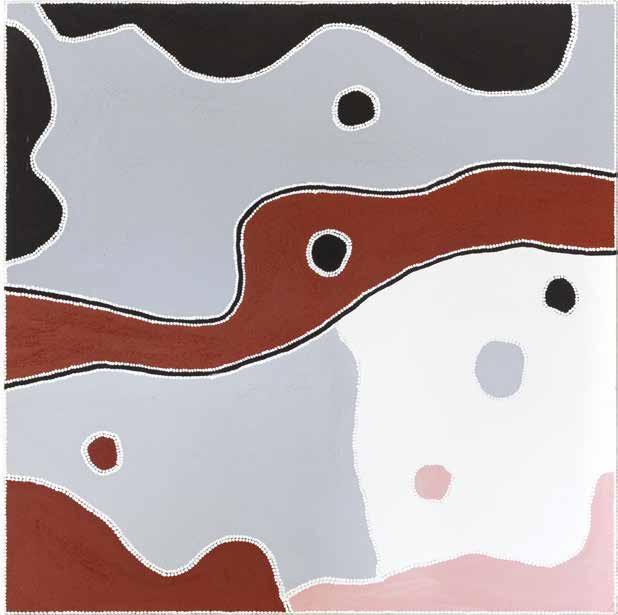

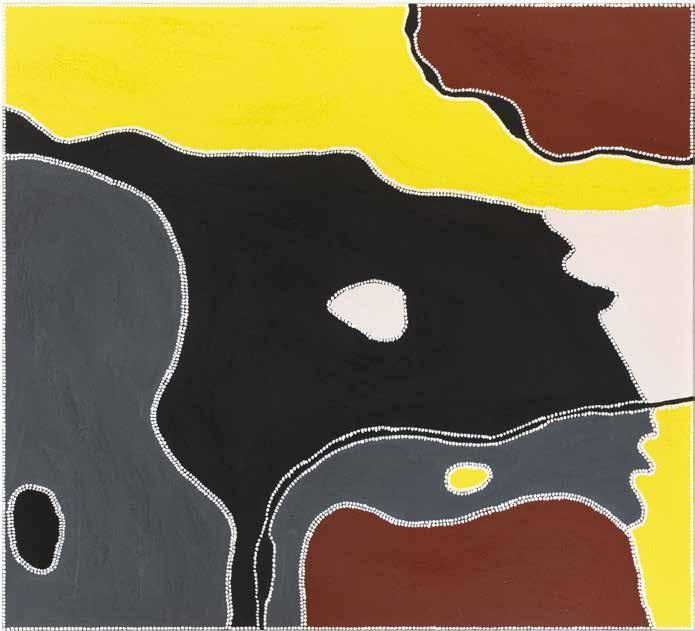

To see how Ngarrmaliny combined his vast knowledge of his country and history with his zen-like artistic vision, look more closely at his work, Wilson River. The headwaters are in the Durack Ranges below Kangaroo Hill and near Bedford Downs, and it flows to the northeast, past Nellie Range, through Devil’s Elbow, Gordon’s Gorge and the O’Donnell Range. His depiction shows more than a map. How did he arrive at this ‘bird’s eye’ view, this aerial view, of this expanse of river, valleys and hills? The black, grey and white presents a stark vision that gives a sense of the harsh history and the spiritual past, its visual style reminiscent of a photograph or lithograph to deepen the sense of looking into the past of that place. Was this where his people camped, on the banks of the Wilson River, when Paddy Quilty and his men came to kill them? Each of the paintings in this exhibition require this kind of inquiry, as each tells a story about a place, its people, and their ancestral spirits.

Professor Marcia Langton AO

December 2022

4 ibid.

LIST OF WORKS

1. Untitled, 2008, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 120 x 120 cm

2. Brushback, 1998, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 120 x 160 cm

3. Untitled, 2013, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Beligan linen, 150 x 150 cm

4. Clarace Spring, 1998, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 122 x 135 cm

5. Sally Bight, 2008, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 122 x 135 cm

6. Waterfall, 2004, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 80 x 100 cm

7. Untitled, 2008, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 90 x 120 cm

8. Wilson River, 2007, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 95 x 180 cm

9. Clara Spring, 2009, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 90 x 120 cm

10. Untitled, 2008, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 90 x 120 cm

11. Fish Hole Creek, 2003, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 80 x 100 cm

12. Cockwood Springs, 2003, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 80 x 100 cm

13. Loomoogool, 2003, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 122 x 135 cm

14. Lazy Polly, 2009, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 80 x 100 cm

15. Untitled, 2009, natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen, 140 x 150 cm

Freddie Timms and the Jirrawun Studio, Wyndham, Western Australia, 2007.

Photograph: © Peter Eve

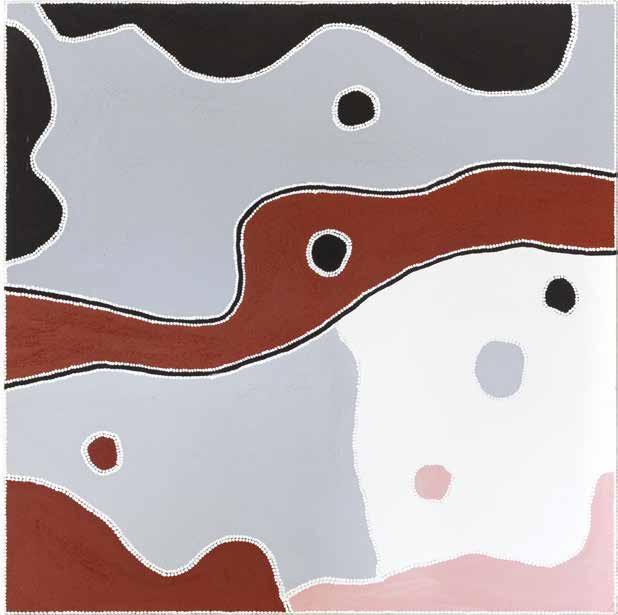

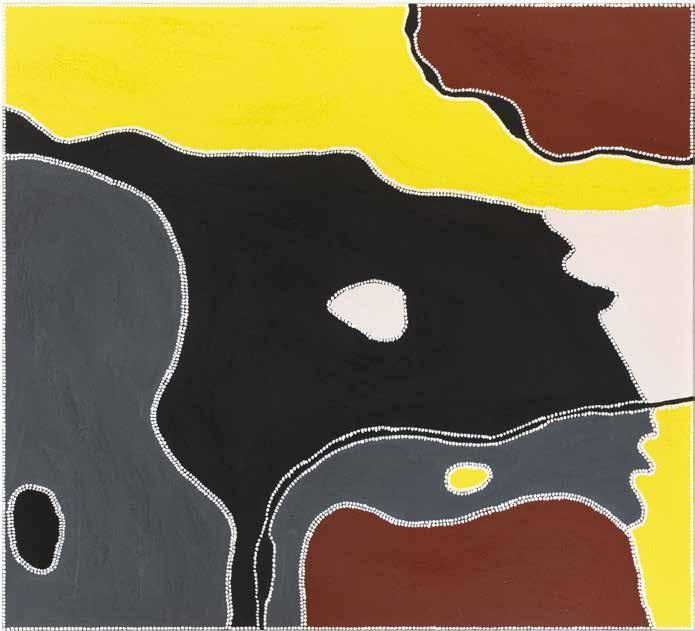

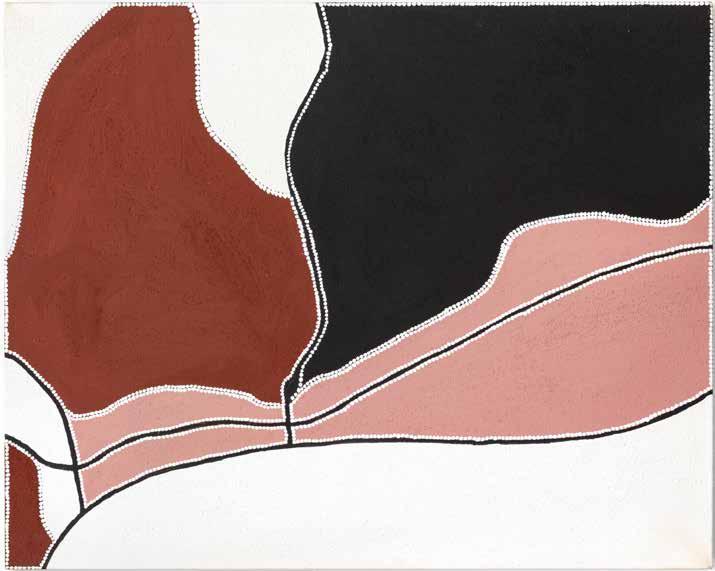

Untitled

120 x 120 cm

, 2008 Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

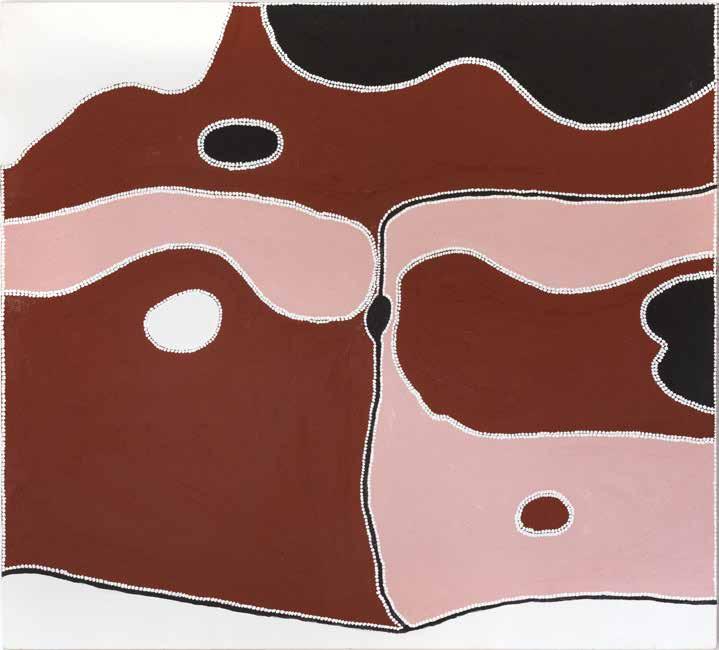

Brushback, 1998 Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

120 x 160 cm

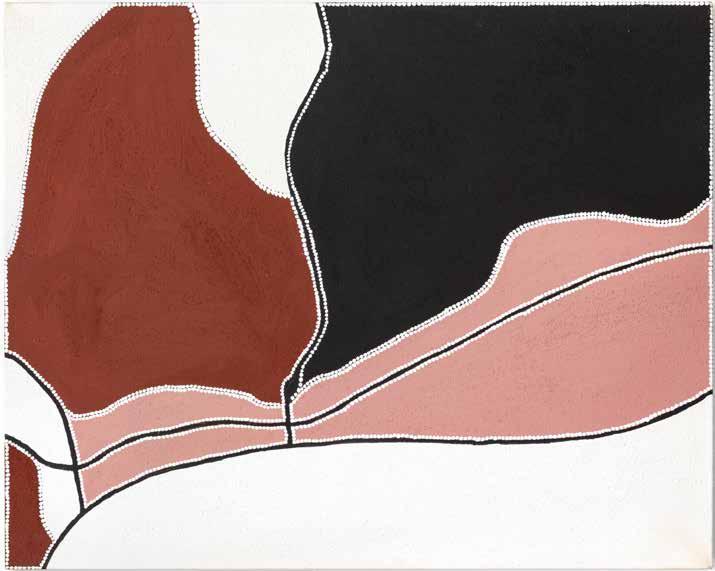

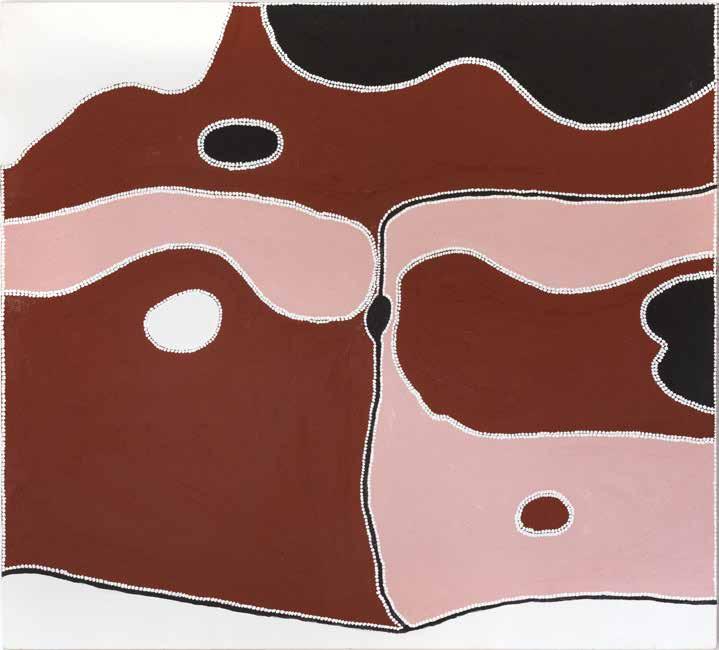

Untitled, 2013

150 x 150 cm

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Beligian linen

Clarace Spring, 1998 Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

122 x 135 cm

Sally Bight, 2008

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

122

135 cm

x

Waterfall, 2004

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen 80 x 100 cm

Untitled, 2008

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen 90 x 120 cm

95 x 180 cm

Wilson River, 2007 Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

Clara Spring, 2009

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen 90 x 120 cm

Untitled, 2008

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen 90 x 120 cm

Fish Hole Creek, 2003

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

80 x 100 cm

Cockwood Springs, 2003

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen 80 x 100 cm

Loomoogool, 2003 Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

122 x 135 cm

Lazy Polly, 2009

Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

80 x 100 cm

Untitled, 2009 Natural pigments and acrylic binder on Belgian linen

140

150

x

cm

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2023 Ngarrmaliny, Martin Browne Contemporary, Sydney

2022 Freddie Timms, Martin Browne Contemporary, Sydney

2018 Mr Timms, RAFT Artspace, Sydney

2004 Freddie Timms, Melbourne Art Fair (Gould Galleries)

2003 Freddie Timms, Gould Galleries, Sydney

2002 Freddie Timms, Gould Galleries, Melbourne

2000 Freddie Timms, Recent Paintings, Gow Langford Gallery, Auckland

1999 Freddie Timms, Recent Paintings, Watters Gallery, Sydney

1999 My Country, William Mora Gallery, Melbourne

1997 Recent Paintings, Watters Gallery, Sydney

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2021 Voyage across Aboriginal Australia - Founders’ Favourites, Fondation Burkhardt-Felder Arts et Culture, Moitiers, Switzerland

2019 Earthworks, JGM Gallery, London

2017 JGM Gallery, London

2008 Jirrawun Colour: Rammey Ramsey & Freddie Timms, RAFT Artspace, Darwin

2008 Last Tango at Wyndham, RAFT Artspace, Darwin

2007 New Legend: Recent works from the Kimberley, William Mora Galleries, Melbourne

2006 Prism: Contemporary Australian Art, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan

2006 Great Masters, Aboriginal Art Museum, Utrecht, The Netherlands

2005 Interesting Times, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney

2005 Jirrawun in the House: a contemporary vision of the East Kimberley, Parliament House, Canberra

2005 Beyond the Frontier, Sherman Galleries, Sydney

2004 Terra Alterius: Land of Another, Ivan Dougherty Gallery, College of Fine Arts, University of NSW, Sydney

2003 True Stories: Art of the East Kimberley, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney

2003 Kelly Culture: Reconstructing Ned Kelly, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne

2003 Jirrawun Jazz, RAFT Artspace, Darwin

2002 Blood on the Spinifex, The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne

2002 Rhapsodies in Country, GrantPirrie at Art Miami, FL, USA

2002 Jirrawun Artists, William Mora Galleries, Melbourne

2002 My Country, William Mora Galleries, Melbourne

2001 Four Men, Four Paintings, RAFT Space, Darwin

2001 A Century of Collecting 1901-2001, Ivan Dougherty Gallery, College of Fine Arts, University of NSW, Sydney

2000 Landmark: Mirror Mark, Mal Nairn Auditorium, Northern Territory University, Darwin; Columbus State University, Georgia, USA; The Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA ANU Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra

2000 Opening 2000, William Mora Galleries, Melbourne

1999 Painting Country, William Mora Galleries, Melbourne

1999 My Country, Northern Territory University Gallery, Darwin

1998 Thousand Journeys: Aboriginal Art from North WA, touring galleries in Tamworth, Newcastle, Albury, Mornington Peninsula, Ballarat, Mildura

1998 The Laverty Collection, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney

1998 Freddie Timms, Ken Whisson, Watters Gallery, Sydney

1998 Jirrawun Aboriginal Artists, Martin Browne Fine Art, Sydney

1998 Jirrawun Artists from Crocodile Hole, Jemma Stowe, Perth

1998 Summer Exhibitions No 13, Watters Gallery, Sydney

1997 Summer Exhibition, Watters Gallery, Sydney

1997 Pallingjang-Saltwater, Wollogong City Gallery, Wollongong

1996 Art Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

1996 Galerie Baudoin Lebon, Paris FIAC, Paris, France

1996 Utopia Art, Sydney

1995 Turkey Creek Artists, William Mora Galleries, Melbourne

1993 Images of Power: Aboriginal Art of the Kimberley, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

1993 ARATJARRA: Art of the first Australians, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Koeln-Duesseldorf, Germany; Hayward Gallery, London, UK; Louisiana Museum; Humlebaek, Denmark

1991 Hogarth Galleries, Sydney

1991 Lindsay Street Gallery, Darwin

1990 Dreamtime Gallery, Perth

1990 The Seventh National Aboriginal Art Award Exhibition, Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, Darwin 1989 Turkey Creek Recent Work, Deutscher, Melbourne

COLLECTIONS

Aboriginal Art Museum, Utrecht, The Netherlands Artbank, Sydney

Art Gallery Of New South Wales, Sydney

Art Gallery Of South Australia, Adelaide

Art Gallery Of Western Australia, Perth

Holmes A Court Collection, Perth

Laverty Collection, Sydney

National Gallery Of Australia, Canberra

Private Australian and International collections

FREDDIE TIMMS (1946 - 2017)