The Coptic Margins of Egypt and Pilgrimage to Tanta

Martyn Smith

© Martyn Smith, 2023

Published in the United States

© Martyn Smith, 2023

Published in the United States

Power is an obvious shaper of human landscapes. We witness Power in the ability of a ruler to physically destroy persons or institutions standing in opposition, and so a militaristic landscape takes shape. But Power often operates in more subtle ways, as when it uses levers of authority in a bureacracy. In that case a faceless world, stifling to individual aspiration, takes shape. The flip side of Power is Faith, which relies on unenforced loyalty generated by charisma and belief. A popular religious leader compels action by means of an inspiring message or vision. Even the best-positioned ruler must grow anxious that sheer force won’t always work, and realizes that things would go much easier if everyone agreed that his commands reflected a divine order. So power perennially seeks to take over symbols of Faith. The representatives of Faith are likewise drawn to Power because they desire longevity and a permanent position in the landscape. Charismatic leaders might define themselves by rejecting the trappings of power (money, architecture, state support), but their followers come around to the value of prolonging their message through institutional structure.

This is a restatement of theory developed by sociologist Max Weber. This theory is clear enough, but we don’t spend enough time thinking about the concrete ways landscapes reflect this dynamic. Power must always be the builder, because it has the treasure. Faith is wary of being found, fearing something vital will be lost once it’s conducted into the halls of power. So Faith is often willing to inhabit marginal spaces. In the central visual essay of this book I show how Coptic Christians have cultivated marginal spaces long invisible and neglected by Egyptian leaders.

Since 641 AD (less than ten years after the death of the prophet Muhammad) Egypt has been ruled by Islamic dynasties. When Muslim forces arrived in Egypt, they encountered a Christian population. Slowly, over the course of several centuries, a majority of the population converted to Islam. For the Christian minority there were limitations on how publicly they could express their faith, so the Copts adapted to marginal spaces. If they could not build the towers that commanded the sightlines of Cairo, they could build towers that ruled the blank spaces of a garbage city or desert. This same faith-power dynamic is present in Islam. I end this essay with a look at the traditional pilgrimage to the tomb of Seyyid al-Badawi in Tanta, at the heart of the Nile Delta. This is an expression of popular Islam, but also a site that’s being pushed to the margins of the New Egypt arising in the desert outside Cairo.

Standing atop Bab Zuweilah, the southern gate for medieval Cairo, the messy rooftops and informally constructed brick buildings are a visual distraction. That disorder doesn’t completely obscure the repetition of minarets and domes through this old section of Cairo. The Mosque of al-Muayyad on the left was constructed by the Sultan of the same name in the 15th century. As visitors proceed straight ahead on the main pedestrian street, they come across many more historic buildings. Cairo was one of the largest population centers of the medieval world. It was majority Muslim, but it included a significant minority of Christians and Jews, yet the monumental expression of religious faith was limited to Islam. To a

large extent this relationship in Egypt between Islam and power lasts to this day. On one side of every Egyptian piece of currency is a medieval mosque, and on this side all the writing is in Arabic. (The reverse side is in English and features an object or site from ancient Egypt.) On this fifty pound note the 15th-century Mosque of Abu Hurayba is depicted. In truth this wasn’t just a mosque, but a multipurpose structure (not far from Bab Zuweilah), which included a sabil for distributing water, a domed mausoleum, a Quran school, and of course a place of worship. That diversity of functions is now gone, and the building is described on the currency simply as a mosque, and as such it can be deployed as a symbol for the

state of Egypt. The medieval city of Cairo couldn’t be located along the banks of the Nile because the river flooded every summer. As a result that earlier Cairo stood back from the Nile a couple of miles. Modern Egypt used the Aswan High Dam and its predecessors to regulate the flow of the Nile. Once the banks of the river were stabilized, it was possible to build high rises directly alongside the river. Modern Cairo wouldn’t be marked by a forest of minarets (though small mosques can be glimpsed along the river), but by palatial hotels (like the orange-hued Cairo Marriott on the left) and buildings for the state (like the white-crowned Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the right). The Nile became a landscape of

state and tourism. In 1517 the Ottomans had marched into Cairo and added Egypt to its growing Mediterranean empire. Previous to that time Mamluk sultans had one by one added imposing mosques to the thoroughfares of the old city, but after the Ottomans came, such building projects slowed. Governors were content to refurbish older mosques or build smaller structures. Then in 1805, after driving out the French invaders, Muhammad Ali came to power. He started out as an Ottoman governor, but soon became the actual ruler of Egypt. He built an imposing mosque in the imperial style of the Ottomans on the high Citadel. Those thin pencil-style minarets are a stylistic feature of Ottoman mosques. This

Mosque of Muhammad Ali remains a popular landmark for Cairo. Despite the numerous medieval mosques in Cairo, the Mosque of Muhammad Ali draws more visitors than any of them. On account of its perch on the Citadel it has taken on a general esteem, appearing often in Instagram feeds. I noticed it wasn’t just tourists at the mosque, but plenty of Egyptians were here holding up their smart phones to capture its vast domey interior. This ruler Muhammad Ali was buried in an ornate marble tomb in a room taking up a corner of the mosque. Visitors are asked to take off their shoes, as with any mosque, but there’s little here of truly religious character. The mosque isn’t associated with a great preacher

or movement. It was a political symbol from the start, and now it has shifted into a new role as tourist icon. On the porch outside the Mosque of Muhammad Ali is a grand overlook out onto Cairo. The Citadel is located atop a spur of the eastern Muqattam Hills, and from here the eye sees nothing but city all the way out to the Pyramids of Giza in the distant west. Between the Citadel and the pyramids (though invisible from here) is the Nile. On this afternoon the courtyard of the Mosque of Muhammad Ali had been prepared for a fancy wedding, and at the overlook a professional photographer took photos of bride and groom. Other members of the wedding party took their own informal photos. The grand view

and a popular wedding marks this as privileged civic space. Alabaster panels covered the lower courses of the Mosque of Muhammad Ali. There’s a reason one doesn’t encounter many structures with an alabaster exterior—it isn’t a durable material. Every mosque in Cairo has to reckon with a regular blasting of sand and wind, and so the alabaster here has a deeply weathered and aging appearance. Add to this the fact that even as Muhammad Ali had broken away from Ottoman rule and established an independent Egyptian state, he didn’t return to classic Egyptian mosque designs, but constructed his own version of an Ottoman imperial mosque. This ill-conceived mosque is now the one many visitors

think of when they recall Cairo. At the time of the ascent of Muhammad Ali to rule, this space was occupied by the ruins of the Great Iwan (or hall). This Great Iwan was built in the 1330s by one of the most powerful of Egypt’s medieval Sultans, al-Nasir Muhammad. It was a monumental space for the administration of justice, and it was meant to awe foreign delegates and contemporary Egyptians alike. The above image gives a sense of its ruined appearance around 1800 as the French invaded (and at the same time documented) Egypt. This is the structure that Muhammad Ali inherited, but preservation of some earlier monumental hall wasn’t his plan for this highly visible space. Its historical resonance

and ruined grandiosity were sacrificed to make way for an imperial mosque with his own name attached. Just outside the enclosure wall for the mosque is now a modest excavation that aims to reveal a portion of the site for the Great Iwan. There’s not much to see except a pit and a few red granite columns over against the wall. These columns give a small idea as to the grandeur of that former hall, but in truth the imagination has little to go on here. The only thing we really have are those old images from the Description de l’Egypte. We might be tempted to praise the French for their pictorial preservation, but they also put into play the process of modernization and state creation that made the presence of

those medieval ruins (on such a high-value civic site) untenable. Just down the way from the imposing Citadel mosque is Egypt’s National Military Museum. The grounds have become a dumping ground for old weapons and a display area for statues of military leaders. This museum especially represents the values of the military leaders who ruled Egypt after the 1952 Revolution. Ahead is a bronze statue of Anwar Sadat, and nearby was another of Gamal Abdel Nasser. The equestrian statue on the left is of Ibrahim Pasha, who modernized the Egyptian army and won some famous victories in the 19th century. I sensed no contrast between that nearby mosque and the values of this military museum. A bronze

plaque on the walkway up to the Citadel mosque illustrates how it has been emptied of any religious associations. The mosque is clear in the background, but the ruler Muhammad Ali, reclining on an old school couch, is given equal prominence.

Above, a sun disk surrounds a seal of the state and the rays of the disk are shown as hands, copying the Amarna style from

the reign of the ancient Egyptian king Akhenaten. The mosque has here been fully incorporated into a vision of state power. Muhammad Ali built his mosque on the Citadel to set his imprint of power on the most prominent ground in historic Cairo. From its perch on the Muqattam Hills his mosque faced down onto the populous 19th century city. But behind the Citadel was a a wasteland, a desert zone without symbols. Back here there are no old mausoleums or mosques, just concrete traffic dividers and dusty microbus stops for the modern city. A wide road cuts today through that empty land. A few trees have been planted in the medians, adding some little greenery to the concrete and dirt.

Such symbol-free non-places are more typical settings for everyday life on our planet, as development far outstrips meaning. Al-Muqattam Street heads up to the top of these hills, and if we were to follow that main road we’d before long find ourselves in a sprawl of desert developments. But in this empty zone behind the Citadel there’s no sign of that development. There’s only this road, which serves as a convenient stopping point for taxis (anyone need used tires?).

This is also the access point for a large Christian community of garbage recyclers set invisibly within the folds of the low hills. That three-wheeled tuk-tuk offered transportation into that informal city. The question I’ll be asking is how a zone

well outside the interest of power becomes meaningful space. This area of Cairo is known as Manshiyat Nasir, or as the Christian District. Some 250,000 people live in five square kilometers. The district consists mostly of informal housing without running water or electricity. The cement and brick high rises with steel rebar sticking out at the ends of each support column are the infallible sign of a poor neighborhood. Such buildings are put up without permits and built as cheaply as possible, without care for aesthetic distinction. The trucks on these narrow streets carry bags of garbage, and that is the main industry in this “Garbage City.” Garbage from around Cairo is sorted here and recycled. There’s good

reason this “Garbage City” is isolated in the folds of the Muqattam Hills. It’s an unsightly place where the streets reek of trash. Bales of trash are piled up along the narrow roads. I was dropped off at the district’s base, where traffic constricted into narrow streets. As I walked up into the city I passed open doorways through which mounds of plastic bottles or jerry cans were visible. The area had become a huge filtration system, and enough money was squeezed from all this garbage and its re-use to support the community. But that didn’t mean the city would smell good (or that the work was healthy for the thousands of Christian garbage workers). I’d come to Garbage City not to gawk at trash but to visit the Monastery

of St. Simeon the Tanner. The residents of this area were engaged in the most menial work in all of Cairo, and their streets (and homes!) stunk to the heavens, but signs pointed visitors to a church and the famous monastery. This was not a district where power wished to invest. The neighborhood couldn’t be seen or visited without special effort (a quick turn off of that empty desert road), so the area was out of sight. What leader wants his name memorialized next to trash? The absence of interest from the powerful had cleared this space for expressions of faith, and within these streets a rich symbolism of faith was evident. Something about the absence of desirability deepened the spiritual potential of

the space. Life in these informal housing structures isn’t easy. I’ve already mentioned the lack of basic amenities. Some of the apartments have been improved by the addition of a window and a cooling unit. The windows function as a space for drying clothes. In poor areas around the world clothes lose their symbolic value. In many places it goes without saying that this or that t-shirt or hat isn’t being worn because someone has an actual interest in the UCLA Bruins or Sponge Bob, but because that item was available in some bin for cast-offs. Still the symbolic world finds positive assertion, and I couldn’t miss the images of Jesus, Mary, and Coptic saints (all present above). In 1969 the Zabbaleen (trash

collectors) of Cairo were relocated to this out-of-the-way area in the Muqattam Hills. Several thousand Christian garbage workers came to live here, and before long they desired to set up a place of worship. The result of their efforts from the mid-1970s on was this complex that includes a monastery and several rock-cut churches. That main church straight ahead is the Church of St. Simeon, whose seating extends down into a massive cleft in the rock. Sacred carvings and statues cover many surfaces, but those communication antennae atop the cliff remind that all this was created out of space that meant nothing to the powerful. This was meant as space given away to unsightly infrastructure, and that

became the opening for Faith. In the plaza across from the Church of St. Simeon a group of cement trees gave shade to Christians attending church here this Sunday morning. No hijabs were visible among the younger women, distinguishing this area from poor Muslim neighborhoods in Cairo, where hijabs are worn by almost all the young women. The young guy carrying cups of coffee for friends or family (and the whole vibe) made this feel like an Evangelical church, but instead of a large indoor meeting space, the socializing had spilled out of doors. Unlike many Evangelical churches in the US that function as enclaves for twenty-somethings, as a minority group in Egypt the Copts hang together as a genuine

community, with representatives from all age groups. The relief sculptures around the St. Simeon Monastery and Church are cut directly into stone or else they are concrete figures set onto the rock. The site is layered with art, representing an ongoing effort to turn these bare rocks into signifiers. Mostly the sculptures portrayed stories from the Gospels. Before long I thought I could detect the pattern governing the story choices: they were passages that emphasized the invitation of Jesus to the lowly. The above image is hard to miss since it faces the parking lot. It’s the invitation of Jesus to the weary and burdened. It was a striking message to encounter after having walked here through the smelly streets of the trash

collectors. The cliff wall that looms over the parking lot is covered with Gospel illustrations. Along the bottom are two scenes of Jesus’ help to those in need. On the left he sits with the outcast Samaritan woman at the well, and promises her water after which she will never thirst. To the right is a scene of Jesus walking on the Sea of Galilee, and Peter sinking with disbelief, calling for help. Above, surrounded by angels, is the triumphant Jesus, appearing as the Son of Man at the end of time, when power and glory switches to the downtrodden. By the presence of this art the hidden and useless space that city planners rejected is transformed into spiritual promise. The largest structure is this Cave Church named

after St. Simeon the Tanner from the 10th century. The supposed relics of St. Simeon are held in a display case down there on the stage. This is the largest church in the Middle East, and seats about 21,000 worshippers (though nowhere near that number actually attend an average service). According to a pamphlet given out to visitors, this church was begun in 1986 and completed in 1991. The image of Christ at the apex of the worship space includes an Arabic translation of Isaiah 53.5: “He was wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities...” That message speaks to people in need of healing, who feel the lashes of this world, and the suffering Christ offers them solace. I couldn’t stop admiring

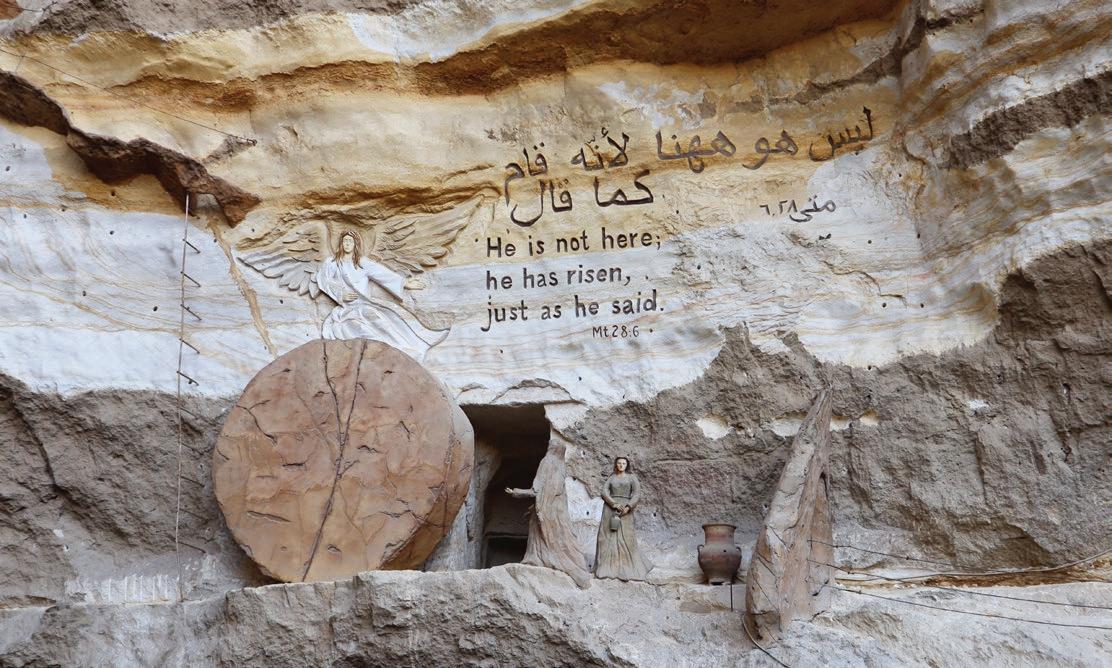

the choices for representation on the rock faces of this church. It wasn’t like some international artist had been hired to design this church, and the sculpture itself was more akin to outsider art than award winning modern design. In this three dimensional image of the Resurrection cave, the two women outside are presented with directness and simplicity. The angel seems to float out of the internationally shared visual imagination of angels (wings, white robe, long hair).

Whatever the naivete of the relief sculpture, the decision to highlight this most famous biblical cave inside this cave church shows a spiritual expertise. A cave church must call to mind that sacred cave, and the resurrection promised to

all. Signs of Covid were still visible. Stone pews were checkered with pieces of cloth on which was spray painted a bright red “X,” meaning, “No one sit here.” Some safe separation was thus gained for worshippers. The cloths that looked worn (as if people were actively moving around them) were in the section nearest the front. Size was clearly the goal of this church, even if it’s only on Easter Sunday that anywhere near all these seats are filled. The empty church allows visitors to imagine the full community of local garbage collectors, which coincidentally are estimated at about 20,000 people, just about exactly the number who can be seated in this church. The church is thus an aid for imagining the entirety of

this community. This poster hangs on the utility office near the front of the Cave Church. It shows the Earth, with Africa at the forefront, and some words from the prophet Isaiah: “Blessed be Egypt my people... a blessing in the midst of the Earth.” This is a highly edited and misleading version of these verses, creating the illusion that God has put Egypt at the center of his plans. A similarly acrobatic handling of the Bible allows one mention of the Holy Family’s sojourn in Egypt to get blown up into a long itinerary through the Nile valley. Why are these passages in English when few around here speak it? Feeling under threat, the Copts strive to make their faith understood to all visitors, especially global Christians.

The front of the Church of St. Simeon the Tanner (the Cave Church) is decorated with an unfamiliar scene. The story goes that toward the end of the 10th century the Fatimid Caliph al-Muizz held a debate with religious leaders. A Jewish leader challenged the Coptic Pope Abraam to demonstrate the Gospel promise that with a mustard seed of faith a believer could move a mountain. The pope prayed about this promise, and Mary appeared, telling him to locate a certain oneeyed tanner, who would be carrying a water jar in the market (lower section of the image). This was Simeon, and with his help a section of the Muqattam Hills was lifted from the earth, and the Caliph was present and believed (shown in

upper section). This story could sound familiar since it is repeated in The Travels of Marco Polo, where the Christian story is transposed into Mesopotamia. Once you start looking around this site, the story of St. Simeon and the lifting of the Muqattam Hills is everywhere. This story long predates the Cave Church complex, which was only founded as the stigmatized garbage collectors were moved here in 1969. But this miracle offered a way to sacralize these hills. It provides some misdirection as the miracle vanquishes a skeptical Jewish leader, and even the Caliph al-Muizz is part of the heretical Fatimids, so he doesn’t represent mainstream Egyptian Islam. But for a person just looking at this image, what’s

most evident on the surface is that Christians are vanquishing their Muslim opponents. In 1991 the remains of St. Simeon the Tanner were miraculously located in a church in Old Cairo. In 1992 those remains were transferred to the Cave Church, and they have become a site of Coptic visitation and prayer. Whatever the unlikelihood of positively identifying the body of an individual who lived more than 1000 years ago, the value of these relics to Coptic believers is clear from all the folded papers containing prayers. Why had there been an effort to locate St. Simeon’s body beginning in 1989? It seems that the miracle story alone wasn’t enough to make the Cave Church a sacred site, and the bodily relics

of a saint offered a way to complete that job, anchoring this space in the sacred. I wasn’t alone walking around the Cave Church; there were many Coptic visitors who’d come to pray and venerate the sacred relics. These relics acted as a point of focus. If there were only that story, visitors could conceivably have sat anywhere and meditated on it. Relics meant there was a place to stand and a shrine on which to leave prayer requests. I watched this Coptic family stopping in front of images and shrines, taking it all in. They touched images and took selfies in front of the shrines. I asked if I could take a photo, and they happily gathered. Their easy smiles are an example of how Copts respond to foreign visitors with

friendly trust. Within the Cave Church I sat for a while and watched people interact with the space at the front. The reliquary for St. Simeon is near the center, marked by a doubled arch and covered with prayer requests. On the right is the family I’d soon photograph. They were arranging themselves in various configurations for smart phone portraits. Along the back wall were other visitors, some prayed at the iconostasis screens that gave access to the sanctuary where the liturgy takes place, others approached the icons and held out a hand to reverently touch the images. It’s a visitor friendly set up that allows for touching, writing down prayers, and photo backdrops. Effective sacred spaces don’t bask

in a concept, but construct opportunities for active use. The buildings around the Cave Church aren’t sophisticated in terms of architecture. They are the same informal brick, cement, and steel-girded structures that appear everywhere in the poorer districts of Cairo, though the central building shows design flare with Coptic crosses on its face. At the edge of the parking lot is a Christian fish symbol. The fish was an ancient symbol (due to an acronym formed from its Greek letters), but this exact “Jesus Fish” design stems from Evangelicalism in the 1970s. In this setting the fish calls attention to the alignment of the Coptic church with global Evangelicalism, and at the same time gives recognition to the popularity

of social media. Young people took turns getting a photo inside the fish. The large Cave Church was by no means the only church. This walkway, surrounded by stuccoed designs, leads to St. Mark’s Church. With these multiple churches, a monastery, and stand-alone statues (not to mention a gift shop and office buildings) the site as a whole had an ad hoc feel. One thing had been added to another, and it seemed obvious that no central plan had led to this spatial outcome.

This is another way in which the site is similar to an assemblage of outsider art. Take this walkway as an example. It feels like entering a green space, and the palm fronds call Palm Sunday to mind, but it wasn’t the creation of some European

design team. If we look for a space in direct contrast to the St. Simeon complex, we could well land on the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, opened in 2021 within sight of the Muqattam Hills. It’s an expression of a unified design and expresses the ideology of the Egyptian state. It makes use of pyramids and contemporary materials in service of creating a thoroughly controlled (and unimaginative) space. There are relics housed here too, since the mummies from the older Egyptian Museum were moved here. The cost isn’t known, but the money expended here no doubt dwarfs what has been spent on the monastery complex built by the community of garbage workers. This museum will draw

more international visitors, but it is empty of genuine vision. According to the website for the “Saint Samaan the Tanner Monastery,” the garbage collectors began to worship in a simple tin building after being relocated here in 1969. These caves were developed as actual churches in the 1980s. This St. Mark’s Church is large, but it doesn’t hold close to the 20,000 worshipers of the main church. This smaller church isn’t a statement about community, but a place of religious fervor. The carvings along the back wall featured moralizing scenes like Joseph fleeing adultery, or St. Simeon tempted by a woman on whose foot he’s fitting a shoe, and readying to gouge out his eye in obedience to the strict words of Jesus.

That story last story deserves more explanation. In this sculpture a woman in a fine cloak stretches out her foot to Simeon (who as a tanner was also a shoemaker). The woman exposes a portion of her leg, and so Simeon holds up an awl in response to this temptation. Directly above this are the verses from the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus says:

“If your right eye causes you to sin, gouge it out and throw it away. For it is better to lose one part of your body than for your body to be thrown into hell.” St. Simeon had one eye because he had literally followed this verse. His spiritual power to move a mountain was founded on such personal morality. The art along the back of this church took up themes

of morality and power. On the right is the story of Samson, whose eyes were gouged out after falling for Delilah, and now he was chained to pillars in the temple of a foreign god. God gave him superhuman strength one last time to bring down the temple on the heads of his oppressors. On the left a painting adds some color to the rock sculptures. This is the story of men who came to this deserted place in the Muqattam Hills back in 1974, and while they were praying a piece of paper was blown into the hand of one man. It was a fragment from the Bible telling them not to be afraid, God is with them, and no one will be able to harm them. This painting brought the experience of divine aid into the present. The rock

ceiling of St. Mark’s Church contained this short line. Christians might recognize it as the last statement in the book of Revelation. After those visions and a final promise that Jesus will indeed come soon, the biblical writer adds, “Amen. Come, Lord Jesus.” This line bestows an apocalyptic feel on this church enclosed in a cave. Why was the line in English, not in Arabic? Apocalyptic modes are the vernacular expressions of groups fearful of their position, so we might expect them to be in the language people here actually speak (Arabic). This choice of English marks a bifurcation of their fear and hope. They are a minority fearful of their place in Egypt, but confident and hopeful with regards to their connection

to global Christianity. The Coptic church has for centuries claimed marginal spaces and wastelands—and made them sacred. Within Cairo we’ve now seen this pattern play out in the Muqattam Hills with the cave churches, but historically Copts have occupied niches of the desert far outside the fertile Nile valley. This desert use predates the arrival of Islam, since Egypt was the early center of Christian monasticism. St. Anthony was a 3rd/4th century monk who left the early monastic settlements and went to live by himself in a cave in Egypt’s eastern desert. After his death other monks came to his spot to take up a similar life, and the Monastery of St. Anthony came into existence. Today it’s a sprawling complex,

and a popular place of visitation for Copts. Having grown up in Southern California, and gained there an affinity for the desert, I’ve long understood desert landscapes as delicate ecosystems. Disruptions caused by mechanized power won’t quickly be eroded away. My assumption is that hardy life always exists in such arid spaces, and ought to be conserved. But Egypt takes seriously the “waste” part of “wasteland.” Its leaders show a disregard of desert landscapes. Deserts are treated as a play area where plans are begun and quickly ended, where piles of rock can just be left. The desert holds no sacred value for those making grand plans, it’s empty space without meaning. The drive from Cairo to the Monastery of

St. Anthony now takes three hours. I remember how it used to take a good deal longer since it required traveling on smaller roads, but the Egyptian government has invested in a multi-lane highway that makes for a fast ride. This highway wasn’t designed to make visitation to the monastery any easier, but to get people to new resort developments along the Red Sea. What is being referred to by this “Soon” billboard along the way isn’t clear, but no doubt it has nothing to do with the the book of Revelation and the quick return of Jesus Christ! It is pointing travelers to the arrival of some luxury development in the desert or on the coast of the Red Sea. All the construction to the side of the new highway seemed

out of proportion to the use of the road. We passed small signs reminding drivers of the grand goal: “High Speed Electric Train.” The portrait of president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi reminds drivers of the ultimate source for this construction. These artificial ridges will be a section of the train line that will connect Alexandria in the northwest with central Cairo, then the new capital in the east, and finally Ain Sokhna on the Red Sea. That line will run 400+ miles and cost at least $4.5 billion. It’s hard to imagine a majority of Egyptians, with average per capita income hovering at $4000, voting to spend so much on a train through the desert. And the cost of the electric train is small compared to the desert development it’s meant

to support. The clean new highway from Cairo to the Red Sea requires American-style highway stops. This type of gas station is omnipresent in the US (and elsewhere), and once outside crowded Cairo the administration builds to meet this global preference. Infrastructure like this caters to those with the means to get out of Cairo. This isn’t Egypt for all Egyptians, and it’s no surprise that the signs are now in English. “Chillout” is a subsidiary (no doubt profitable) of the state-owned road company. To “chill” in contemporary parlance means to temporarily pull out of the anxiety producing modern world, only to re-enter once sufficiently calmed. Needless to say, ancient monastic life was not at all about

“chilling” in this contemporary sense. I grew up with Circle Ks everywhere in Southern California. They were the most common stand alone convenience store (even more common than 7-Elevens). So it was surprising to encounter a Circle K in Egypt, but with a little Googling I see that the company I knew as Circle K was bought by a Canadian corporation in 2003, and then in 2015 that corporation took the brand international, which has come to include gas-up convenience stores like this one in Egypt. It was strange how unsurprising the contents of this store were. Many signs are in English. The drinks (Coke, Fanta) and snacks (Skittles, Ruffles) are well known. It delivered exactly what I would have guessed.

Right next to the Circle K was this open space. I would’ve preferred shade, but the goal instead was to provide small tables and plastic chairs where travelers could take a break. A shallow blue pool was surrounded by this thin green turf. Rocks and even plastic turtles and a starfish ensured desert winds didn’t pick up and blow the turf off its marks. The water and sea creatures served as a foretaste of the destination to which the majority of people were likely heading: those Red Sea resorts. It requires time to transit through this void of the desert, and the pit stops were intent on making us forget about the experience of being in the desert: “The desert might be void of interest, but take a break along our

artificial sea coast!” Across from the artificial lagoon, and near the Circle K, was this curious structure. Its design draws on ancient Egypt, with those colorful papyrus columns and a pyramidal shape on top. The Arabic writing on the side identifies the structure as a mosque, a place of worship for Muslims. People traveling to or from the Red Sea can pull off the highway and complete their prayers. Such roadside mosques are common, and while I’m sure there are travelers who make use of these wayside mosques, their greatest value is in the realm of symbol. The Egyptian state uses such mosques—even here in the desert—to remind travelers of Islam’s primacy and its commitment to support the faith.

Ultimately deserts are transit zones. Human built structures aim to get people, goods, or energy through this zone with some level of safety. In this mountain pass a lot of effort was expended to shave down the mountain and make it passable. A pass like this isn’t a lasting structure so much as a smoother-of-the-way for transportation. Since the desert isn’t conceptualized as a place of interest in itself, states and their corporate arms show little care for the landscape. If it could all be cut down and made straight, they would do exactly that. Egypt dreams of building New Cairo in the desert, but this itself is a denial of the desert as an actual thing with physical properties (the absence of water). The Desert

Fathers were a movement of early Christians out into what were understood then too as wastelands. They felt the need to escape the world and live strictly according to the command of Jesus: “Go, sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven...” So the desert was for them something like a transit zone (just replace Red Sea resorts with Heaven). Some men went to the desert to live by themselves. Soon communal orders came into existence at those sites. Unlike the new developments of Cairo going up in the desert, the monastery wasn’t meant as a denial of the desert, but constructed in a manner appropriate for its setting. Palm trees and a small garden claim an unexpected

spiritual life in the emptiness. Monastic life has always had security threats. Old monasteries often took on a resemblance to walled forts in their effort to fend off Bedouin raids. The initial line of defense was to do without valuable objects (what could you steal from St. Anthony in his cave?). As monasteries took shape they acquired manuscripts and fine liturgical objects, and so got themselves on the radar of plunderers. Today the threat is different. The highway makes it easier to get here, but it also makes the site more vulnerable to terrorist attack (something that has plagued the Coptic community in Egypt). These military vehicles at the entrance show the state’s concern about this threat. Before stopping

at the monastery proper I went straight to the trail leading up to St. Anthony’s Cave. Truthfully it’s more of a stairway than a trail. The cave at the end is a homestead relic for the person of St. Anthony, and most who come to the monastery (those who are able) make their way up the lengthy path. This morning I happened to be the only person on the trail, and a solitary hike up seemed fitting since I was in pursuit of a man famous across the Christian world for his solitary life. It was very hot (no cloud in the sky, just a con trail), and that Arabic sign warns visitors for their safety to stay on the stairway going up and coming back down. Along the stairway to the cave of St. Anthony were rusting metal signs that

delivered in Arabic either a verse from the Bible or a saying from an ancient church father. The movement up was tiring, and the sun took its toll, but the signs never let me forget that this desert was no vacuum, but spiritually meaningful. The rocks and dryness echoed and responded to these words. The sign on the right contains words labelled as being from St. Anthony: “Don’t speak all your thoughts to all people, rather only to those who have the power to save your soul.” In just those words we glimpse a rationale for leaving the corroding world and enter this desert setting: “why be around people who don’t sympathize with your spiritual longing? Get yourself into a space of faithful community.” Putting up those

signs on the path took planning (likely by the monastery). Just as important were informal signs of devotion on the path to the cave. There were many crosses, sometimes on a graffitied outcrop, but other times they were formed out of loose rocks on the trailside. Here the meaningless scatter of desert rocks come together to make the dry ground repeat a spiritual message. These crosses testify to the urge to become an active participant in a sacred experience. Money can buy grand churches and national museums, but it can’t create the feeling of the sacred that impells visitors to stop along a trail and create a tangible message to be read by those who come after. For pilgrims there’s no spiritual penalty in

looking back. Pilgrims aren’t analogous to Lot’s wife fleeing Sodom. Reassurance could be found in measuring out my steady progress up the mountain. The true extent of the monastery below came into view, and I could note the existence of a large rest house and two arrays of solar panels. St Anthony’s Monastery wasn’t a curiosity for antiquarians, but part of the living Coptic faith. Even more spectacular, was the desert opening up beyond the monastery. That larger view made clear the extent to which the monastery was like an island refuge. No spectacular scene out there distracts the pilgrim from looking inward for spiritual fulfillment, just an unappealing flatness. It’s easy to get tired along the trail up,

and to concentrate on the effort being expended in this ascent. It could be tempting to feel spiritual pride in all this effort to get up here (never mind the long trip just to arrive at the monastery). There’s a quotation from St. Anthony for pilgrims starting to feel this way: “If we remember our steps, God will forget them, but if we forget about them, God will remember them for us.” It’s a reminder to be on guard against spiritual pride, but more than that it’s an encouragement to nurture a joyful spirituality that’s so caught up in God that effort is entirely forgotten. That’s the promise of this upward path to the cave. I could now see up against the cliff edge the platform that had been built around the ancient

cave of St. Anthony. The end was in sight. This small chapel had been constructed as a stopping point for pilgrims before reaching the end. Its white plastered gate and walls were covered with graffiti (“Remember, Lord, your servant Majdi Rashad”). As was evident from the signs along the way, this path wasn’t built with the simple goal of getting people from point A to point B. This trail was no transit zone. Pilgrimage isn’t about eliminating the journey. This was an experience meant to be drawn out with stops, which meant the trail would provide the occasions to stretch out the journey. The end could be contemplated at this chapel, but for many this wasn’t a call to hurry up, but to slow down with a time for prayer.

As the trail wound through its final stretch I wondered why a hermit would choose a cave so far up the slope. He would constantly be in need of going back down to the valley for spring water (the site of the eventual monastery). Among the ancient sayings of the Desert Fathers I found an anecdote about a monk living in the desert twelve miles from any water source. On his way to get water one day he felt tired and decided he’d move closer to the water. Then an angel appeared and explained that he counted the monks steps for his future reward. So the monk decided to move even farther from the water. This distance from water was part of the hermit life, part of their spiritual heroism. The actual cave of St.

Anthony was smaller than I’d imagined. It was basically a slit in the cliff face. After this the hole only got narrower, and I found myself ducking and squeezing to get all the way in. Many visitors had penned or scratched their name on the outer rocks at the cave entrance, and I imagined regular effort to erase these markings. Many ancient sites are a matter of pious guesswork. For example, all the sites on today’s Mt. Sinai related to Moses and the Exodus story were a grand work of geographic fiction written on that landscape by early Christians. St. Anthony attracted followers during his lifetime, and since the monastery has existed here since that time, there’s little doubt those monks have passed down the correct

location of the cave. This was the view back toward the entrance to the cave. The cave sides had been smoothed down by countless visitors running sweaty hands along the walls, making the cave smell like an old sneaker. Still it was possible to imagine the constricted life of St. Anthony. The coolness of a cave was what made escape into the desert possible. The cave functioned like a womb for this austere spirituality. One ancient Desert Father advised a monk: “Go and sit down, and entrust your body to your cell, as a man puts a precious possession into a safe, and do not go out of it.” This wasn’t so much a desert based spirituality as the spirituality of the enclosed cell. The sayings of the Desert Fathers contain

almost nothing about the actual landscape around them, but lots about these cells. Inside the cave I saw no attempt to imagine how the cave might’ve looked during the life of St. Anthony. No attempt at historical preservation such as I once witnessed at the cramped jail cell of Nelson Mandela on Robben Island in South Africa. This cave of St. Anthony existed outside of history. It was a sacred relic that pilgrims could get inside, and once there they responded as they would for any relic. I found a small table with a box for prayers and four small images. Most striking was the reproduction of Christ Pantocrator (“Ruler of the Universe”) from St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai, dated to the 6th century. This icon,

along with other images, was offered as a point of meditation for pilgrims. At the center of the small table was a red box, which served as a place to desposit prayer requests. Dozens of folded pieces of paper lay in the box, testifying to steady visitation. Outside the cave I saw smaller pieces of paper stuck into cracks in the cliff face. The presence of such popular devotion is part of creating sacred space (as we noted in the Cave Church back in Cairo). The image on the right is St. Paul the hermit, who preceded St. Anthony to the desert (his monastery is on the other side of these desert mountains). On the left is St. Anthony himself, with beard and wooden cross. He’s shown (anachronistically) in the habit worn now by

Coptic monks. Back outside the cave I stepped up to the edge of the platform. A central cross framed the flat desert landscape. Command of a vista is a natural symbol of power. But here it seemed an inversion of power, a reminder of the words of Jesus: “My Kingdom is not of this world.” This vista should be understood within the context of Egypt. The sight lines in Cairo, remember, are dominated by Islam and state power. Since the arrival of the Arabs in the 7th century state power has been aligned with the religion of Islam. Copts are a significant minority in Egypt, but their monumental presence is limited to spaces no one wants, whether that means the neighborhood of garbage collectors or this empty

desert. Some old posters had been attached to the side of the cliff platform. This one had faded from exposure to sunlight (plentiful here!). Half of the Arabic lines were nearly invisible, but the blue lines were still clear. The two lines at top were all one needed to know to understand the Desert Fathers. The lines were the words of Jesus: “If you want to be perfect, go and sell all your possessions, and give them to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.” This and other sayings from the Gospels served as their deepest inspiration. The faded image of St. Anthony appeared to symbolize the faded vitality of these lines when it comes to our contemporary world order. I was surprised

to discover I had good connection up here at the entrance to St. Anthony’s cave. I was standing in front of a symbol of disconnection from the world, yet from this place I had access to the entire globe through the internet. I opened Instagram and an image came up from Dubai of the tallest building in the world and the luxury development at its base. If I were searching for a global opposite to St. Anthony’s cave, this might be the image I’d choose. But it’d be wrong to say that this cave was ever anything but global. The story of St. Anthony and this cave retreat spread far and wide in the ancient world, even playing a role in the conversion of St. Augustine in Milan, Italy. The story of St. Anthony was a kind

of ancient meme that sent other monks out into the desolate regions of their world. Not far from the cave platform was an area where lots of plastic water bottles had been discarded. These were the same water brands for sale everywhere in Egypt, and obviously pilgrims had made their ascent in the hot sun and tossed aside their bottles. If we imagine St. Anthony during his life here in the 4th century, it’s difficult to imagine any trash whatsoever resulting from that lifeway.

Many saints, with their simple life choices, could be contemporary avatars in the struggle against climate change, but these eco-friendly lives are ignored as the sites have become sacred relics. Nothing about the presentation of this

ancient cave asked visitors to make different life choices. I should mention that this wasn’t my first visit here. In 2002 I’d visited the Monastery of St. Anthony and followed those steps upward to his cave. Then we traveled to the other side of the desert mountains to visit the Monastery of St. Paul the Hermit. We spent the night at that monastery, and I took photos of our simple dorm-style lodgings. St. Paul on the right is always portrayed with a rustic look, and the two lions that helped dig his grave are always at his side. St. Anthony in his Coptic habit is on the left. It was an interesting friendship between hermits, as they supposedly met for just one day and one night. During my previous visit to the

Monastery of St. Anthony, a friend was taken aside by a monk and asked about whether he could get a specific laptop battery and have it mailed to the monastery. There was quite a lot of technical information exchanged. My friend was happy to help, but we later laughed at the idea that a monk here was worried about a laptop and his internet connection. The

monks today participate fully in social media. As I sat in a waiting room, expecting the monastery guide to show up, I examined the images. Coptic icons now require expertise in Photoshop. Along the bottom of this image is an actual photograph of the monastery, which blended into the traditional-style (though still modern) image of St. Anthony.

The Coptic lettering up top (based on Greek) is complemented by the Arabic (which Copts actually speak) for the Gospel verse in his hand. As I began to walk around the monastery (with a guide who highly resembled all these images of St. Anthony), my eye wandered to that tallest palm tree. I realized it wasn’t a palm tree at all, but a cell phone tower serving the monastery grounds. And it clicked: this is the reason I got such great reception up at the cave of St. Anthony! But although visitors expect to encounter here a site for the ancient spiritual drama in individual souls, it’s better to remember that this is a site for modern Egyptian Christians, who use sacred wastelands to set out their place within the nation. That

being the case, anything that makes the journey more convenient for modern Copts is welcomed. At the heart of the monastic enterprise—past and present—is water, so I kept an eye out for the water source, which was at the back of the walled monastery. Early accounts of the desert fathers mostly obfuscate their total dependence on water, but it comes out at points, such as this account of a monk searching for a cell: “The eagle flew off to the right... the monk went in that direction and saw three palm-trees, a spring, and a little cave. He said, ‘Here is the place God has made ready for me.’” The narrator wanted to get to God as quickly as possible, but water is at the heart of his anecdote. There are plenty of

caves in the desert, but water is the necessary element. After driving for some time through bare desert to reach the monastery, it felt miraculous to find a stream of fresh water flowing out of the rock. Today this water is all put to use by the monastery and its 100+ monks, so it’s controlled (and displayed) within this narrow channel. The view of water flowing out of rock is surprising, so I was amazed that none of the icons in the church or for sale in the gift shop made visual reference to it. The austere life of St. Antony was the miracle, in the eyes of believers, not the actual material support for his desert existence. It’s a human-centered vision, and the water just showed up as divine aid for this saintly

life. The old monastery church featured spectacular 13th century paintings. The walls of the central section of the church, into which visitors first enter, is covered with a series of riders on horseback. These are ancient Christian warriormartyrs, presented as triumphant and powerful, but who in life all met a grisly death at the hands of the persecuting Romans. Above is Theodore the General from the early 4th century, not well known now, but whose story includes an occasion where he entered a city and was entreated by a woman to save her children from a dragon. He valiantly slew the dragon, but his valor didn’t save him from being tortured and crucified for his faith. The walls of this church had been

restored in the late 1990s. For centuries the imagery had been obscured by a dense cover of smoky grime, so that only the outlines of this ambitious 13th century project could be seen. The restorers left a small rectangle of uncleaned space so that visitors could see the former state of the walls. The tail of that dragon was visible, but all sense of color and detail had been lost. It’s a miracle (and pleasure!) of living in this time that so much of the past (archeological and textual) has been restored. Expert preservationists make sure that alert visitors can gauge the work that’s been done, and even begin to imagine the early appearance of this church. It’s not hard to see why martyr-warriors made attractive subjects. They

had the gallantry of warriors in life, yet they had endured gory deaths. And they could be re-imagined as victorious warriors in heaven. On this church wall they’ve been granted a kind of idealized or heavenly form. St. Victor is on the left, and underneath we see him being burned in a bathhouse and his body bloodied upon a millstone. On the right is St. Menas, who had refused to serve as a Roman soldier because he wanted to be a soldier in heaven. Both saints met their end around Alexandria, so medieval monks and visitors would’ve recognized them as Egyptian saints. Moving into the second section of the church, the wall is covered with a line of standing men, each with a dense white beard. These

turned out to be the Desert Fathers, whose words and deeds were passed down in a widely read volume. The programmatic message seems clear: these self-deniers were worthy successors to the famous early martyrs. The men here include Saints Pishoy, John the Little, Arsenius, and Pachomius. All are known for this or that anecdote in stories about the Desert Fathers. The painted images include names and visual tells (sometimes subtle) that point to their identity. On the left, at the entrance to the next section of the church, is St. Anthony himself, the symbolic head of this whole illustrious line of desert monks. From this angle the later monks appear like mutations from that first source. In

the above image I’m looking forward from the nave into the sanctuary itself. A service was ongoing (though no one was in attendance). A decorated wooden screen allowed just a glimpse of the wall paintings that continued further back. The modern restorers had made sure to preserve graffiti from historic visitors, so there in large letters, right on that screen before the sanctuary proper, was the name of a Western visitor from 1626. Quite a choice for graffiti, right where everyone would have to see your name! The Franciscan Bernardus Siculus thus staked out a place in the memory of the monastery (he wrote his name elsewhere too), without so much as a pious tag asking for prayer. The walls of the church

were covered with graffiti and symbols left by medieval and later visitors. Most inscriptions are in Arabic (the living language of later Copts), but others are in Syriac, Ethiopic, Armenian, and Latin. If the program of the wall paintings testifies to a vibrant and creative Coptic identity, the graffiti speak of a global Chistianity. The above graffito looks to me to be written in Syriac script, with some Arabic writing mixed in. Perhaps it’s an example of Garshuni, or Arabic written in Syriac. Much of this has yet to be deciphered, so this and other wall texts serve as mute witnesses to a medieval Christianity where faith felt itself as a unity existing above the unreal borders established by kingdoms and regional

languages. In 356, the year of St. Anthony’s death, Egypt was part of the Greek speaking Byzantine Empire. That changed in 641 as Arab Muslims conquered Egypt. From then on Egyptian Christians would live under Muslim rule. This monastery church reflects an earlier political sensibility. Byzantine churches preserve mystery by their complex layout. Some sections are sacred and closed off, and side chapels offer themselves for pious visitation. In the entrance to the small side chapel visitors look up into an archway and can see the oldest art to survive in this monastery church. This image of the risen Christ has been dated to the 6th century, and so its maker saw himself as part of a linked (though troubled)

Mediterranean Christianity. Most of the other paintings in this church were completed in the 13th century. The halfdome of this chapel was decorated with another painting of the risen Christ. On the left the Virgin Mary leans toward Christ, and on the right John the Baptist (barely visible) does the same. Christ sits enthroned over all, and so it appears to be exactly the same subject as the much earlier painting nearby. Yet the political context has changed completely. In this case the painter is presenting a view of cosmic power that in no way conformed to the reality in Egypt, but represented a hopeful vision for an invisible reality that will someday be established. We sense a community pushing forward a claim

to continued vitality within the now fully Islamic Middle East. The monk giving me a tour was named Father Ruwais, which I can recall now because he gave me an actual business card. He appeared to have gotten this position as guide on account of his skill in spoken English. As I looked around at the paintings in the old church, he was notified that another group had arrived. So we retraced our steps back to the refectory, and started over with the tour. This group turned out to be visiting from the Czech Republic. They were staying at a Red Sea resort (an inexpensive vacation destination for Europeans), and they had this opportunity to visit a Christian site. The woman nearest Father Ruwais provided a running

translation into Czech from his English. Father Ruwais looked almost exactly like St. Anthony in contemporary icons. There was the long white beard, of course, but since St. Anthony is now portrayed in the habit of a Coptic monk, the clothes and hat were also a match. Near the end of the tour Father Ruwais stopped to ask if he could say a prayer for Ukraine, since Russia had brutally invaded that country just a few weeks earlier. This story was dominant in international news, and Father Ruwais rightly judged that this Eastern European group would appreciate this prayer. Several fervently nodded at this suggestion, and for a moment everyone grew serious. I bowed my head too, but I was happy to get a quick

photo of a monk in spiritual action. The monastery included this small garden with palm trees, and I sat here for a time. Gardens were important for monastic life, providing communal work and food. But we should resist the idea that these monasteries were self-sufficient islands of civilization. They depended on visitors from the outside for food and supplies. The cave of St. Anthony and the later monastery were only symbolically isolated. It took great effort to reach the monastery from a well-traveled road to the Red Sea, but the place wasn’t ever out of touch with the cities of the Nile basin. This garden could never have fed the monks all on its own, but in this desert it functioned as a sign of ongoing

divine care for a small community. Across from the garden was a more recent structure for a museum. A museum isn’t a traditional part of a monastery, but with the restoration of the paintings and other parts of the monastery, it provided a place to display surviving elements of an older monastic life. For unclear reasons the museum was closed when I visited, but I found that it could be virtually toured on Google’s Arts & Culture site. So I did get a chance to see these displays. The cooking implements showed an uncompromisingly communal manner of eating. The monks shared their food on that large copper tray, dished out common portions from the same pots. There was no hint here of individualized

choice. In the heyday of desert monasticism, this communal form of practicing Christianity had a suprising appeal. It was noted that the desert became a city (so crowded parts became with monks). On the drive from St. Anthony’s Monastery back to Cairo we passed the developments of the new Egyptian capital. The desert is now truly becoming a city, though it’s unclear how this will ever be environmentally sustainable. The desert monastery once allowed for a counterpoint to the everyday life of the Nile Valley. It assured Christians of a deeper spiritual life that was possible. These new housing developments ask residents to forget the spiritual symbolism of the desert and enjoy a flat modernity. St. Anthony’s

Monastery presented a garden as a symbol of the abundant life that’s possible in the desert of the world. The garden remained humble, and it wasn’t hard to imagine the small spring providing all the water necessary for the garden.

Through the centuries the monks lived a simplified life, a match for their desert environment. In contrast the billboards advertising new residential developments in the desert are a work of deep fantasy. There appears to be a superabundance of water for these dwellings, as if the desert has been liberated from supply considerations. The lifestyle on offer in this and other developments is one of individual plenty. The desert has been overcome! Returning to Cairo we passed these

men waiting on the side of the road for a bus to take them home at the end of a day. Coming from the monastery, I wondered what such spiritual communities could now offer to the millions struggling to find their place in the world (in Cairo, but the whole world too). The institution of the monastery once thrived, but could it still offer hope in the modern world? Behind the men is yet another billboard for a well-watered residential development (“Green River Villas”). Such billboards aren’t there for the men waiting to get on a bus, but for those driving their own vehicles. On account of its environmental realism, call for community, and voluntary simplicity, monasteries could yet become sites for hope. Back

in Cairo after my visit to the Monastery of St. Anthony, I looked down from my hotel room onto a crowded road into central Cairo. This was in the days leading up to Ramadan, so everyone, it seemed, was out making preparations for the month-long holiday. The 6th of October Bridge across Zamalek and the Nile was at a total standstill. It was landscape whiplash to move from the desert scenes of a sparsely inhabited monastery to the river-based city of Cairo. And of course a large majority of Cairo is Muslim, so they were hardly thinking about Coptic monasteries as Ramadan approached, yet the challenge of monastic life still applies: consume less, do less, find peace. The lotus-inspired tower on Gezira

Island is one of Cairo’s notable structures. It was completed in 1961 and attempts to fill the role of civic tower like the Space Needle or the CN Tower. Then president Gamal Abdel Nasser had it built as a show of state independence from Western meddling. It gives an expansive view of Cairo, but visitors never forget that it’s a state symbol. At the tower’s base is the

eagle that appears on the Egyptian flag, itself inspired by an eagle inset into a wall of the Citadel. From the Cairo Tower a road moves north along the island’s edge into the wealthy district of Zamalek. We see (again) that Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Well-lit billboards speak of pizza, corporate office space, and delivery services. In the modern city deeply felt religion sits in parenthetical spaces. We might apply the words of Jesus from the Sermon on the Mount: “Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” The implication is that interior values become visible in real world investments. With that in mind, we understand that the heart of modern Cairo is the tight intertwining of state and corporate power.

It’s not only Coptic sites that thrive in the margins of Egyptian state power, the same can be said for popular Islamic sites. Take the city of Tanta, for example. Few tourists are drawn to this city of 650,000 since it has no large museums or archaeological sites. It sits in the heart of the Nile Delta, a vast triangle of green agricultural land pocked by towns and cities. The main attraction in Tanta is the tomb-shrine of 13th century Sufi Seyyid Ahmad al-Badawi. On the annual “mulid” or festival day of al-Badawi some three million people come to Tanta on pilgrimage. This makes Tanta the host of one of the largest religious events in Africa, and it takes place far from the structures of state power in and around

Cairo. Like many sacred sites, Tanta is readable from above—at least that’s true of its center. The mosque of Seyyid alBadawi is that large rectangular structure inside an urban ring road. In the 19th century Tanta became an important center for cotton export, and so it was linked to Cairo and Alexandria by that rail line. From the train station a double wide avenue proceeds straight to the mosque. A smaller mosque had stood in that space many years, but the larger mosque was built with an eye to its relationship to the train station. The plan is easy enough to see: pilgrims would arrive by train, and the straight avenue would frame the mosque for them. Then shops for jewelry or sweets crowded the

narrow streets to the side of the straight avenue. Here’s a view on the ground. The cream-colored mosque seems to float out ahead of the crowded street and its shops. One difference between this site and other places of pilgrimage (here I’m thinking of Touba in Senegal) is that it didn’t feel like it was under construction. There’s no sign of regular expansion or renovation on account of generous gifts from Egyptians here or abroad. The cityscape itself wasn’t dotted with subsidiary pilgrimage structures, such as sites associated with the life of the saint. That single mosque and the open space around it accommodated all the needs of pilgrims. Infrastructure like hotels and food stand nearby, of course, but Tanta doesn’t

appear to be a site with massive investment by the powerful. That’s not to say there aren’t changes. For my visit in 2009 getting from the train station to the mosque was a matter of navigating a busy street, filled with Egypt’s standard car horn background. Pretty much nothing in Egypt was then designed with pedestrians in mind! But on Instagram I see that the pilgrim experience has now been enhanced by the addition of a gated pedestrian walkway. These changes took place during the Covid years, and though there’s little discussion of this new construction online (the Wikipedia page for the mosque has just two lines of text), the changes are fully registered on Instagram. The sense that pilgrims might have to

constantly dodge cars to get to the mosque has abated, and some peaceful seeming photos are enabled. Kiosks with the goods that mark popular Islam lined the street to the mosque. Those metallic blue eyes promise to ward off the destructive glances of envy known as the “evil eye.” The related Hand of Fatima brings the same apotropaic power. Small red scrolls hold pious words from the Quran. These inexpensive goods give a sense of the pilgrim audience here in Tanta.

This mosque and its annual celebration aren’t part of formal contemporary Islam, but survivals from a deeper tide of popular Islam. This version of Islam was marked by veneration for the burial places of Sufi saints. This isn’t the Islam of

the modern residential developments in the desert outside Cairo, but the Islam within the beating heart of the populous Nile Valley. When I visit a site I try to identify visual hallmarks. What are the unique elements of this site that will cling to the memory of the pilgrim? On the exterior that ornate colonnade marks this sacred site. It directly faces every visitor coming up that straight avenue from the railway station. It provides shade for small groups of people (especially women who can’t so easily hang out inside). A plaque here records that the colonnade was added by president Anwar Sadat in the mid-1970s. Egyptian state patronage will be part of any religious structure in Egypt. It would be impossible for the

state to ignore a site that draws hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of visitors. I searched Instagram to see what visitors had found visually memorable about the Mosque of Seyyid al-Badawi. It’s an important mosque for Egyptians and visitors from Southeast Asia, and these mark their presence with a photo (posted to social media). The question must arise: what to choose as backdrop? By and large it was that exterior colonnade, with that dome over the tomb shrine of al-Badawi often rising behind. That colonnade became the “iconic” part of the mosque that identified the location to others. I’m not arguing that this is some world-class architectural gem, but to be effective buildings need an

architectural fingerprint communicating that visitors are truly somewhere. In the vocabulary of Egypt’s traditional Islamic architecture a dome is always a marker for a tomb. In this case that tomb is for Seyyid al-Badawi, and pilgrims can know from afar that the tomb will be directly under that dome. This Sufi saint has been memorialized here in Tanta since his death in the 13th century, but there’s no way to reconstruct all the stages of the site. In this photo an older stone wall supports a more recent dome, as can be seen from the subtle but clear variation in the color and age of the stone. The first monumental mosque here was constructed in the 18th century. Since then, rulers of Egypt, including president

Sadat in the 1970s, have expanded and renewed the mosque and shrine. This postcard captures the approach to the mosque in the early 1900s. That ornate colonnade didn’t separate the street from the mosque proper, and cars didn’t yet overrun the straight avenue (which was then narrower). The bases of the domes have the same design, but the striped masonry is gone, and the upper dome has been rebuilt in stone. That lone minaret on the right is Ottoman in design, with the distinctive pencil-like style. When this mosque gained monumental form in the 18th century, it reflected Ottoman state power. In the 20th century that minaret disappeared and a neo-Mamluk minaret was built in its place,

and much later two even taller minarets were added on both sides of the new colonnade. Architectural changes represent revisions in the message of state power. The interior of a mosque in the heart of a populous area functions more like a city park than a pristine cathedral. In the earlier Google Earth image of central Tanta no parks or open green spaces are visible. Most cities in the US as a matter of course provide green spaces for relaxation and exercise. Within an Egyptian city the mosques are always open and on a hot afternoon men enter and hang around inside for lots of reasons. Some men are doing prayers outside the regular times. Others are just looking for a quiet place to take a nap or read a

newspaper. Still others are there for the same reason as me: to look around the interior of this well-known mosque and take photos. Most historic mosques in Egypt have an open-air court in the center. That court is typically surrounded by columned halls giving space for worshippers. In the latter part of the Mamluk era that open court was replaced by a closed but highly decorated interior court. The Mosque of Seyyid al-Badawi was of this style. The ceiling here was flat (remember, this wasn’t space that would be properly covered by a dome), but the roof was slightly raised so as to let light stream in through windows. This was the most impressive part of the mosque interior, though of relatively recent

construction. The reason Tanta is at the center of a major pilgrimage is this tomb shrine of Seyyid al-Badawi. Sufi spirituality, from Turkey to Egypt to Morocco, is dominated by the visitation of sites where the baraka (blessing, spiritual energy) of holy men is available to pilgrims. Visitors enter this room and pray standing at the shrine or sitting along the wall.

This spirituality based on the intercession of Sufi saints is frowned upon by modern fundamentalists. On this trip I came across a postcard of Egypt’s ten major Islamic shrines. Each shrine functions as the center for a popular festival and is housed in a mosque or mausoleum. I added a yellow box above to highlight the shrine of Seyyid al-Badawi. The shrine on its left is that of Seyyid Ibrahim al-Dasuqi, a 13th century contemporary of al-Badawi, also from the Delta. The other eight shrines are in the heart of Cairo. Taken together the shrines represent a national version of Islam. The Egyptian state has largely been responsible for maintaining the settings for these shrines, but as major investment moves out of

Cairo popular forms of Islam will no doubt be weakened. The shrine at Tanta reflects practices that have long defined Egyptian Islam. The greatest shrine in Egypt is at the heart of Cairo, and it’s said to contain the head of Husayn, martyred grandson of the prophet Muhammad. Cairo proper was founded in 969 AD by the Fatimid Dynasty, who were Shi’a and claimed spiritual authority based on descent from the prophet. They were eager to display relics of this sacred lineage, and when they “discovered” the head of Husayn it was brought to Cairo. Even as the Fatimids were overthrown in 1171 AD, their spiritual legacy continued in the shrines they had established. Sufi shrines were a later addition to those

practices. Some days before I traveled to Tanta I had visited the shrine for Husayn. Even at an off hour the highly decorated sacred shrine was crowded with visitors. Many stood at the outer barrier and prayed for aid in some aspect of their personal or professional lives. Some set flowers into the window grills of the shrine. Other men sat against the wall and read from the Quran or prayed. Some men entered and took flip-phone photos of the shrine (this was 2009), which perhaps they’d never visited. Such photos were so common that I felt comfortable taking out my own small camera. It was the shrine for Husayn’s sacred head, but it was the true heart of the older spirituality. These men were the drivers,

store owners, and accountants of central Cairo. In the Egypt of 2022, president al-Sisi invested in desert developments, and so the need arose to supply all these new neighborhoods with mosques. Whereever I went in these developments

I saw impressive mosques under construction. The mosques look half-built, as do the residential streets nearby. These areas aren’t fully inhabited, and it’s easy to wonder if these new mosques won’t just remain grand shells. But they raise

a question: what will be the claim to the sacred for a new mosque like this? In older sections of Egypt near the Nile there are shrines and spaces that for centuries have been woven into traditional practices. This space above began as blank

space, and now there’s a mosque sitting atop that empty space. The Al-Fattah Al-Alim Mosque at the New Administrative Capital of Egypt will accommodate 17,000 worshippers. There are rumors of an even more ambitious mosque that could hold over 100,000 worshippers, but we’ll stick for now with this one that is coming into existence. It is designated as the official venue for state services, but it’s not clear where the 17,000 people to fill this mosque would come from. Someday perhaps they’ll arrive by droves on the monorail rapid transit line that will pass by here (for which those supports are being built). Or perhaps the new capital will become a functioning city, with residents, and they’ll drive here. For now

this mosque operates purely as a symbol of state power. Returning now to my experience in Tanta over a decade earlier, I recall exiting the Mosque of Seyyid al-Badawi. I looked back to watch the stream of people exiting the tomb-shrine. It seemed a true mixture of ages, but in terms of class they appeared similar. These were mostly middle or lower class Egyptians. Tanta is a sh‘abi, or popular, religious site. My guess is that the more Egyptians engage with global culture, the less likely they are to participate in this traditional pilgrimage. I wondered about these people and their lives, and at this point an anthropologist would sketch a research proposal. A traveler like me works differently, happy to notice small

things, collect the ephemeral, and keep moving. After my visit to the shrine I returned to the hotel where I was staying. The hotel (that tall tan building) was located along the straight avenue leading to the mosque. It was the New Arafa Hotel. I see now that on Trip Advisor it gets only 2½ stars, which is to say it was no Hilton. But it was the best option in Tanta and its

market was pilgrim visitors. The name itself “Arafa” would remind visitors of the Mount Arafat, which has an essential role in the Hajj at Mecca. Thus the smaller pilgrimage opened a vista onto the larger one. My room in the New Arafa Hotel left no doubt as to the character of the expected guests. A small sign taped to the mirror noted in Arabic the “direction of the qiblah” (that is, for facing Mecca in prayer). The chair beside the bed had a neatly folded prayer rug, ready for use. The pilgrims that come here to make visitation at the tomb shrine of al-Badawi were first and foremost Muslims. The sign and the prayer rug (with its image of the Kaaba) would remind the pilgrim of Mecca. In the climate of

global Islam, Sufi shrines are suspect, and the fact that a visit has to be surrounded by reminders of global orthodoxy doesn’t bode well for the future of these practices. Walking around the small streets near my hotel it continued to be clear that Tanta was not positioned as an end in itself. This shrine expressed a traditional spirituality, but the memory of the actual Seyyid al-Badawi is vague. I saw no displays of books on his life and teachings. But there were lots of visual cues pointing onward to Mecca. Travel agency signs like this one above proclaimed in Arabic “Mecca and Medina,” and images of Mecca’s Kaaba were displayed in taxis and stores, making it clear that Tanta is the lesser stop. This isn’t always

the case, for example at the Great Mosque in Touba, Senegal pilgrims could never forget that this is the sacred site of their saint Amadou Bamba. My room in the New Arafa Hotel included this painting of an English cottage. With those rounded hills in the background, this couldn’t be anywhere in Egypt. Few Egyptians live in standalone houses (certainly not ones that look like this!), so it seemed natural for there to be conceptual gaps in the pictured world. Is that a driveway for cars? Why is the picket fence hard up against the house? Is that some sort of electrical box on the right near that out-of-the-way lamppost? For me the painting symbolized just how difficult it is to grasp the inner logic of a distant