Preface

This second visual essay on Dubai represents an exploration of Expo 2020 (delayed until 2021 because of the pandemic). As a rule I don’t have any desire to attend major international events like the Olympics or World Cup. But this World Expo was different: I needed to attend. In recent years, with actual disasters and forecasts of further disasters from climate change accumulating, I wondered how this would transform our concept of the nation state. It’s already clear that climate change will be a destabilizing event for the international system. Forced climate migration across borders will continue to rise and the scarcity of basic resources like fresh water will push nation states into conflict. In addition, steps taken by any individual nation to mitigate carbon emissions are insignificant, since what’s needed is a global framework. What evidence was out there that our system of nation states would prove malleable enough to meet these challenges?

If there was a fresh public perspective on the nation state I figured it could show up in the national pavilions of the Expo.

I’ll cut short any speculation and note that there didn’t appear to be any movement to re-imagine the nation state. Our system of nation states is an old and curmudgeonly institution, and it remains stuck defending itself as a stable, solidly bordered thing. Expo 2020 turned out not to be a clear

window into a future global system so much as a reflection of the current ideology of nationhood. I was surprised at the extent to which, after all the design cleverness thrown into these pavilions, they all came back to the same ideals. That made my job in this visual essay a little easier, since I didn’t need to cover a bewildering array of national visions, but rather walk cover a handful of key pavilions.

In the course of reflecting on the experience of Expo 2020 I began to research another Expo from the past: the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Thanks to material I browsed at the Newberry Library in Chicago, including guidebooks and image collections, I felt like I could imagine this grand event held along the shore of Lake Michigan. Although the Dubai and Chicago Expos were linked in the effort to put on an awe-inspiring event, and to present the global system in a physical and walkable form, the underlying view of the world had shifted dramatically between 1893 and 2021. The global order in 1893 was based on colonialism and industrial progress, and within that order nations justified themselves with constant reference to the past. Turning to 2021 the design sensibility was always modern, and interest in the past had been displaced by a focus on the future and technological transformation.

Physical

Map Handed Out to Visitors at Dubai Expo 2020

Israel

Al Wasl Plaza and Dome

USA Pavilion

Terra Sustainability Pavilion

Kazakhstan Pavilion

UK Pavilion

Russia Pavilion

UAE Pavilion

Saudi Arabia Pavilion

Pavilion

India Pavilion

China Pavilion

Switzerland Pavilion

Palestine Pavilion

Metro Station

Al Wasl Plaza and Dome

USA Pavilion

Terra Sustainability Pavilion

Kazakhstan Pavilion

UK Pavilion

Russia Pavilion

UAE Pavilion

Saudi Arabia Pavilion

Pavilion

India Pavilion

China Pavilion

Switzerland Pavilion

Palestine Pavilion

Metro Station

Arriving at Dubai Expo 2020 was a simple matter of taking the Metro. The Expo was the last stop on the line and then it was a straight walk from the station to the Expo entrance. The first stop for visitors was the massive Al Wasl Plaza (wasl means “connection” in Arabic). The pavilions and attractions fanned out from this central plaza. Past world expositions are famous for architectural wonders like the Crystal Palace or the Eiffel Tower, so Expo planners felt the need for a memorable centerpiece in Dubai. How could Dubai, a playground for wonder-structures, not have a marvel at its center? The Al Wasl Plaza Dome was the end result, setting into three dimensions the ring-like Expo 2020 logo. The dome was designed by a Chicago based architectural

firm in consultation with Emirati leaders. The abstract patterning of the circles and other geometric shapes reflects a basic inspiration from Islamic design. It would be possible to look at this dome and guess that the Expo was based in an Islamic country, although the exact country might not be clear. One design reference is more specific to Dubai and the United Arab Emirates. That central pairing of circles and diamond shapes was based on a gold ring said to have been discovered at an archaeological site in the desert of southern Dubai. This serves as an example of how elements dug up from the ancient past allow modern nation states to construct identities more specific than transnational religious identities. So the dome managed

to check the box for both a transnational religious identity and one more specific to the UAE. “The future” turned out to be a central word for the nations present at the Expo. Religions create stories about the future. But in the tech world of Silicon Valley the concept of the future has come to dominate all other concerns. The basic idea is that the past is a straitjacket of useless dogma, but grand possibilities open up if we leave all that behind and re-imagine every aspect of life. Dubai largely adopts this Silicon Valley ideology of the future, and this was written onto the walls that funneled visitors into the Al Wasl Plaza. If human beings harnessed their creativity, together we could create the future we want. A promotional video labeled the Al Wasl Dome

the “beating heart” of the Expo. In daytime the dome served as a welcome screen against the direct sunlight, but at night it was lit up with projections and became a living structure. The fine mesh within the geometric cells serve as a screen. Since this is Dubai the dome sets a world’s record for the “largest projection space.” On one promotional clip running horses were projected onto the dome, visible from far away. We didn’t see much in the way of projected horses or other animals on the dome, though it was beautiful at night with its ever shifting colors. On our final night at the Expo we came across a Nissan SUV on display at the center of the plaza. Corporate representatives were standing around talking up the car, and so converting this huge plaza

into an unavoidable Nissan advertisement. The vast dome had been transformed into a projection space for the corporate logo of Nissan. All across the firmament these logos blinked on and then faded out, like so many stars coming into existence. Of course the central Al Wasl Plaza wouldn’t remain a site for relaxation, but would host the most obvious advertising possible: selling cars. After our first morning arrival at the Al Wasl Plaza we headed to the left, I’m not sure why. We would have some days to explore the national pavilions that were the heart of a World Expo. The idea of coming to the Expo was to see how nation states presented themselves and their ideals in this era of planetary challenges (climate change, mass migration, inequality). I

hoped to find patterns in the way nations presented themselves as part of the global order. Would I be able to discern a workable vision for the future? The walkways between the pavilions were covered by various forms of shade-giving covers. This was December, so temperatures were mild, but the sunlight was direct and nonstop. We avoided the large weekend crowds by starting on Sunday, the first day of Dubai’s work week. (Less than a month after we left, Dubai decreed that it would adopt a standard Saturday/Sunday weekend.) The whole point of a World Expo is to give opportunity for nations to set up a pavilion representing their values and people. If we take away the nation state, there’d really be no point to an Expo. We first tried the

pavilion of the United Kingdom. On the outside it was a series of long planks seeming to extend from a central point. At the end of each plank was a small screen for the display of words. These words changed every few minutes, making it look like poetry was getting created on the spot. Poetry was the only way to understand a phrase like “a moment glazed by their brightness.”

It was nonsense in any literal reading. The pavilion was created by UK-based artist Es Devlin, who calls herself a creator of “large-scale performative sculptures.” All the large pavilions attempted to deliver a guided experience rather than be oldfashioned halls with objects kept pristinely behind glass cases. We walked up the switchbacking queue to arrive at the entrance

to the UK pavilion. There wasn’t much of a queue this early in the day, so we moved ahead quickly to the entrance. On the ground along the way were prompts to come up with a word about our mind. I took this to indicate a feeling word about internal experience: I’m empowered; I’m elated; I’m puzzled; I’m on edge; I’m imagining; I’m anxious. There wasn’t yet a place to enter words, but we were being prompted to think along lines that might prove useful fodder for the AI poetry creator that would produce the public poetry of this pavilion. The pavilion designers didn’t want us coming up to the prompt and just writing “pizza,” but words that could be part of a meaningful-sounding stream of words. The word above the entrance to the UK

pavilion was dream, though like all the words at the front, this one too changed periodically. If I had to guess one art form that will be the lasting contribution of the English nation to future civilization, it’d be poetry. The names come quickly to mind: Shakespeare, Milton, Keats, Tennyson. But while poetry is a good enough theme for the English pavilion, the notion that an AI would create poetry out of crowd-sourced words seemed to deconstruct the human accomplishment of all those poets. Upon entering the UK pavilion I was pointed to a tablet that asked for a word. I typed in “king” but that was rejected. I typed in “green” and after a moment I received this computer generated couplet incorporating my word. I took a photo so as to ponder my

personal poem at a future time. Poetry commonly expresses an individual’s perception or feelings, and the words match or expand a reader’s sense of the world. But what can we say about these AI generated words? What could it mean to be “in the garden”? And why “remember it”? Why does it matter that “the bird was still”? The particularity that could make this meaningul is absent, and these are just words linked together as if they reflected a context. Nothing in those words reflected my experience of Dubai, and the only thing remarkable about the words was how quickly they would’ve disappeared into the universe if I hadn’t taken a photo. Looking up from my tablet I was in the midst of this curving interior space. On the exterior the pavilion

was composed of long horizontal planks, but visitors entered an unexpectedly hollow space fully defined by curves. Other words chosen by visitors were displayed up ahead, and these were the rough material out of which the longer poems on the pavilion’s exterior were constructed. Surprising phrases and thought alignments were bound to appear from a big jumble of positive words, but the human work of meaning creation had been forfeited. Visitors weren’t prompted to create, but to enjoy unique phrases. Underneath this was an implication that poetry was a matter of processing excellence and passive enjoyment, not active reflection on the meaning of human experience. Leaving the UK pavilion we wondered if Expo 2020 would be a bust.

My son could see a humorous angle and imagined the pitch for the UK pavilion being made to Boris Johnson, who in his daffy way would’ve pronounced it “brilliant! genius! Poetry is as English as whiff-whaff! Approved! Now on you go...” But the country pavilions got more insightful after this low bar. We spent two full days walking around the Expo, ducking into this or that national pavilion. We had no plan, just a lot of curiosity and time. The pathways connecting the pavilions were covered with creative sun shades, and it felt like an international design call had gone out for “best shade ideas.” The variety of responses was on display throughout the Expo. In this visual essay I’ve been writing “we did this” and “we went there.” This is as good a point

as any to note that the “we” stands for my son and I. Although I love to travel, I’m not some digital nomad, picking up and moving from place to place. I have a home and life in Wisconsin and if we learned anything during the Covid-19 pandemic it’s that my profession of teaching doesn’t work well across digital channels. Effective teaching is about being in person and in place with other human beings. A relatively small percentage of my time is spent traveling, but I enjoy throwing myself into trying to understand a new place, reading books before and after my visit, trying to answer the questions that I ask myself by taking photos. Travel is great when shared with others, and on this trip my son was an ideal conversation partner. Our next

pavilion was the one for Kazakhstan. We were about to walk right by it, but a Kazakh worker assured us we’d love this pavilion. The exterior was formed out of curving sheets of synthetic material. The gold-colored interior wall borrowed design motifs from ancient Kazakh art. At the Expo we never saw structures reflecting anything like classical architecture, with its columns and defined orders. The designers of all these pavilions were in thrall to a modern style. There was no end to bending and curving materials and designs, and though the particularity of a nation was marked by surface level detail (like these Kazakh design motifs), an underlying modern design sensibility was obvious. The adoption of this aesthetic was the initial point where

a nation signaled commitment to shared global values. The opening experience inside the Kazakhstan pavilion involved a walk through the steppe. The total area of this space was multiplied by mirrors (so you can see me taking this photo across the way).

The lights coming up from the grassland evoked fireflies at dusk. Grand mountains rose behind us and were projected everywhere by mirrored columns. There was a sense we were moving through magical land. Many pavilions made an effort to create an opening experience that communicated some inner core of national experience. Often nations turned to the natural world for this defining trait that was all their own. Nation states are voracious identity definers, and anything unique within

their physical borders will get taken up as fodder for national identity. Like other pavilions, Kazakhstan told a story about itself as a nation. When possible these national stories were lodged within the grand narrative of human history as constructed by modern anthropology. At the start of the Kazakhstan pavilion a screen animated the waves of migration as humans moved out of Africa and into Europe and Asia. One of these waves ended at the Great Steppe, and so the implication was that we should see the Kazakh people (and the nation itself) as deeply rooted in the grand human story. Connections to modern world religions (and their stories about the past) were always played down at the Expo. It was more important to anchor the nation in

this first story of global dispersal. Some pavilions relied on the general pool of foreign workers in Dubai, but the better ones had tour guides representing their own country, and this was the case with Kazakhstan. One stop in this pavilion was for a replica of the ancient “Golden Man,” a skeleton buried with a spectacular golden outfit. The Golden Man (who might have been a Scythian noble) was discovered in 1969 within a pristine mound dating back to the 3rd century BC. This figure shot up quickly in symbolic value after this discovery, to the extent that the national monument for Kazakh independence features a likeness of him at the top. In the Expo pavilion we heard a glowing introduction to the Golden Man from our guide. Tulips sprout up in

front yards all around my Wisconsin neighborhood as spring arrives. I receive bulb catalogs that advertise the varieties that can be delivered to my doorstep. It has crossed my mind in the past to learn about the origin of tulips. They must’ve grown wild somewhere before being diversified into so many varieties by horticulturists. So where was that? Thoughts like this come and go for many things in modern life, but only rarely do I chase down the answer. The Kazakhstan pavilion put a little spotlight on tulips and noted that this was the land that gave them to the world. In other words, this is where they once grew wild. The designers put a similar spotlight on apple trees, which were claimed as another Kazakh gift to the world. Kazakhstan gained

independence at the breakup of the Soviet Union, and in 1997 its capital became Akmola, which was shortly after renamed Astana. In 2019 the capital was renamed (again) Nur-Sultan after an outgoing political leader. The name is confusing, but the city is a design marvel. Nur-Sultan was designed in the early 2000s by Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa, and his plan was largely realized. Architectural marvels continue to be added to the city, and a screen in the pavilion portrayed the capital city of the future. Something about the Expo being in the wonder city of Dubai made other nations want to show off their own modern city plans. The city was being transformed into a site for the projection of national identity. At the end of the Kazakhstan

pavilion we watched a live performance. A man in an athletic outfit walked on stage and began to interact with a computerized arm. The performer didn’t speak, but the changing scenes in the background and the voice of a narrator interpreted what we were seeing. At first it seemed as if the point was to demonstrate a mechanical arm mirroring the motions of a performer. But quickly the choreography got so complex that it became clear that the actions of the arm were entirely pre-programmed. The voice spoke in World Expo bromides: “How we imagine our future today is the key to creating a better tomorrow.” Again, the concept of the Future served as a powerful tool for organizing our view of the world. Eventually the performer was sitting on

the mechanical hand and soaring through the sky. We were treated to a vision of a city floating in the sky (cue memories of Cloud City from The Empire Strikes Back). The sunny message from the narrator was that humans will harness artificial intelligence to achieve a “harmonic symbiosis between mankind and planet Earth.” The path to the future will be to extend technology until we can build a sci-fi environment for humans. The natural world will run perfectly alongside this one. I could see no willingness to imagine that the fossil fuels being consumed in pursuit of this tech future could destroy civilization long before cloud cities were ever realized. This and other pavilions were sites for the projection of confidence in the global future,

nevermind the rumbles of this newly vocal planet Earth. Right next to the Kazakhstan pavilion was the one for the United States. Although the geographic and political position of Kazakhstan was light years from that of the US, their stories were in near alignment. I had a growing suspicion that there was one contemporary metanarrative shared by all nation states, but expressed in slightly different ways. Where the US diverged was the embarrassing (I write as a citizen) overload of national symbols. Nobody else had such a row of waving flags, and all visitors had to pass under the national seal. This uber-patriotic design was perhaps a remnant of the Trump administration, since presumably it was put together back in 2019. Just inside the

entrance to the US pavilion was this statement in English and Arabic: “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of the Future.” Those words riff on the opening of the Declaration of Independence, which sets a baseline for human rights: all men are created equal with unalienable rights, among which are “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” The switch of “Happiness” to “Future” doesn’t sit well with me. Pursuit of the Future is a marker for participation in the global economy, and a hallmark of the futureideology, but it’s not a human right. The switch makes the phrase into a mindset to be achieved. My own pursuit of happiness might well mean rejecting the official orientation to the future and success. It might well mean a stubborn attachment to the

past! Inside the US Pavilion we stood on a moving walkway that took us through a series of displays. The first display featured this replica of the torch for the Statue of Liberty. The screen in the background portrayed a changing landscape, and the narrator described the US as founded by people who left home to chart a course for a better life and future. This colonial landscape was quickly transformed into a peaceful scene from the Early Republic. In this version of American history (set out here for global consumption) the words “future” and “liberty” neatly explained the nation. There was no mention of the grand counter narrative formed out of the search for justice for all and the progressive recognition of the value of all lives. The job of a national

pavilion wasn’t just to tell the story of a nation, but when possible to link the nation to the host country, which this year was the UAE in the heart of the Islamic Middle East. This connection could be accomplished through photos of the respective leaders

meeting together, but the US went further and made the striking gesture of allowing the Quran that had been in the library of Thomas Jefferson to be put on display. It hadn’t traveled outside the US since it was added to Jefferson’s collection. It was behind glass, but the object’s point was made: the US has a history of being interested in this part of the world. US political discourse is by no means free of hostility to Islam, but this was still a nice touch. The US pavilion told a version of US history

that every tech entrepreneur in Silicon Valley would recognize. One by one pieces of the modern world that had their origin in the US were introduced on the screen. An old-fashioned rotary telephone was projected, and it was replaced by a map of the world with lines connecting distant places around the globe. This phone was accompanied by images of cars and airplanes and rockets. The US was positioning itself as the originator of globalization, and it’s true that many US inventions have amplified the ability of people to connect at a distance and contributed to the homogenization of global experience. The point of pride at the Expo was always the global, the links between human beings that had been made on the planet’s surface. The global was

visually marked by webs of lines spreading across the world. In 1893 Chicago hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition. This Expo marked the 400th anniversary of Columbus arriving in the New World (and just 100 years later few people were interested in celebrating Columbus). In the midst of this tech-heavy narration, the US pavilion displayed an image from the most famous Expo hosted within its borders. At first I couldn’t see how that past Expo fit into this national story, but it worked as a reminder that the US has always been a full participant in events of global connection. The expectation of being able to see and taste the world in one place was no doubt a contributor to the later imagining of the World Wide Web. It didn’t take long for the US

pavilion to come around to the tech story. A quotation from Steve Jobs led off. Now, Steve Jobs didn’t treat people well. There’s a substantial literature out there (films and books) about his abusiveness to workers and his own daughter. He had what an early employee described as a “reality distortion field” in which he bent the will and sense of possibility of those near him. What mattered was only the brilliant products—the Mac or iPhone. In 1997 he wrote the script for an ad celebrating “the crazy ones” who’d changed the world. Within this pavilion, the words of Steve Jobs were set on a wall and took on a scriptural quality: true Americans take up this future orientation and change the world. It is a hint of the new civil religion shaping our view of the

American past. There were a smattering of authentic objects within the US pavilion. As with all the pavilions at the Expo, the designers had little desire to build a museum of things, and more interest in presenting grand vistas via massive screens and voice narration. When actual objects were present, it was usually to make a specific point (the Quran from the library of Thomas Jefferson). So here in the section where Steve Jobs was canonized as a great American, we find a sacred object: the original iPhone. It’s set behind protective glass, and this small device with rounded corners is transformed into a symbol for the global connections created by this future-oriented nation. Still standing on the moving walkway that took us past images of American

innovation, and past the Steve Jobs display, we came to a section that put the spotlight on diversity. The screens were filled with a young woman of uncertain ethnic identity. She turned out to be Gitanjali Rao, an American of Indian descent. She was only 16, but a quotation from her was on the wall: “Anyone even remotely interested in creating social impact can be an innovator.” The designers liked that word “anyone” since it pointed away from the previous white men. The future of “the future” is (as presented here) that the role of innovator will be taken over by people from all backgrounds. Diverse people take their place in the US as they step forward as value-creating innovators. It felt then and now like a narrowing of the American vision. As has

been explored in books of environmental history, the United States constructed its national identity out of natural scenery. In a landscape devoid of Europe’s stone castles and scenic ruins, nature itself became the touchstone for identity. For anyone who didn’t think that the automobile and the iPhone quite summed up the American experience, it was refreshing to come across this display of natural scenes in the US pavilion, introduced by a sample gateway. But this concept of the national park was fully contained by the global system. Nature was a signifier for a particular nation, even as climate change is forcing us to think more intently on the scale of the planetary. We can no longer imagine the work of preserving nature as being a matter of setting aside

plots of land. Throughout the Expo I was surprised by the role of space exploration in these national pavilions. Any nation that could credibly claim space accomplishment made sure to do so. Nothing could be a greater cause for national pride than satellites and rockets. The US—as the leader in this general endeavor—added lots of reminders in its pavilion. The final room featured a Mars Exploration Rover set up on a mockup of the Martian landscape. This was the ultimate proof of national greatness: touching another planet. It was a nod toward some multiplanetary future. As the anticipation of climate catastrophe grows, odd hopes get pinned onto such inhospitable places. Just outside the US pavilion was a replica of the Falcon 9 rocket

made by SpaceX. These rockets are capable of lifting a satellite into orbit and then safely landing for re-use. That’s a big step for normalizing space flights. Elon Musk is the entrepreneur founder of SpaceX. Just two weeks before our visit to the Expo Musk responded to the criticism of a sitting senator with this Tweet: “I keep forgetting that you’re still alive.” Odd that the US would put

such a notable disrespecter of its system at the heart of its national pavilion. One of the best things about the Expo was the international food. Many national pavilions had a restaurant attached, and whole buildings featured multiple vendors from a single global region. The US pavilion went with a diner! The offerings centered on the old-fashioned cheeseburger or hot dog, with french fries on the side. When it came to drinks there was a fast-food dispenser giving a choice between Pepsi, Diet Pepsi, 7UP, and Mountain Dew. Could the US really not be more creative? Sure, fast food and these flavored soft drinks were an innovation, but is it really the best foot forward for American food? It’s the most widely known but also least interesting part of

food in America. Once visitors had bought their cheeseburger and fries, they could take a seat directly under the exhausts of the Falcon 9. Unfortunately, a rocket isn’t highly effective at giving shade. Even early in the day those red and white seats were overexposed in direct sunlight. Why seat people right under the exhausts of a rocket? Maybe someone thought it’d be humorous? Maybe it seemed like a way to impress visitors with American power? The one consolation I took was that this all had a peculiarly Trumpy feel (fast food, rockets, power). My guess was that the pavilion had been designed under Trump and then swerved a little to incorporate a video statement from new president Joe Biden. The pavilion might well look quite different if designed

under another administration. This “Pursuit of the Future” notebook from the giftshop of the US pavilion would’ve been a useful holder for my ongoing notes and observations on the Expo. My view of these Expos is that they are bad at giving a window for the future, but good at encapsulating the conceptual framework of the present. As country after country lined up to tell the same story about innovation and the future, they reported on a global consensus. But all this design work had taken place before the Covid-19 pandemic. Expo 2020 had been pushed back to 2021, but no nation that I knew of had re-designed their pavilion. The Expo as a whole was like a time capsule back to 2018, but now the concerns of the planet were swamping the

easy adulation of global connections. The China pavilion was fittingly ambitious, reflecting its role as a global power. The pavilion took up the look of the red lanterns hung on festive occasions in China, symbolizing prosperity. It acknowledged the contemporary design trends visible in all the pavilions, but at the same time avoided any hint of the playful or frivolous. The exterior of the pavilion gave the first impression for visitors. The first test for a national pavilion is whether it achieves an innovative design that both decisively leaves behind traditional architecture and yet through its creative design still calls to mind some typical feature bearing on national identity. In this respect the China pavilion succeeded. Upon walking through

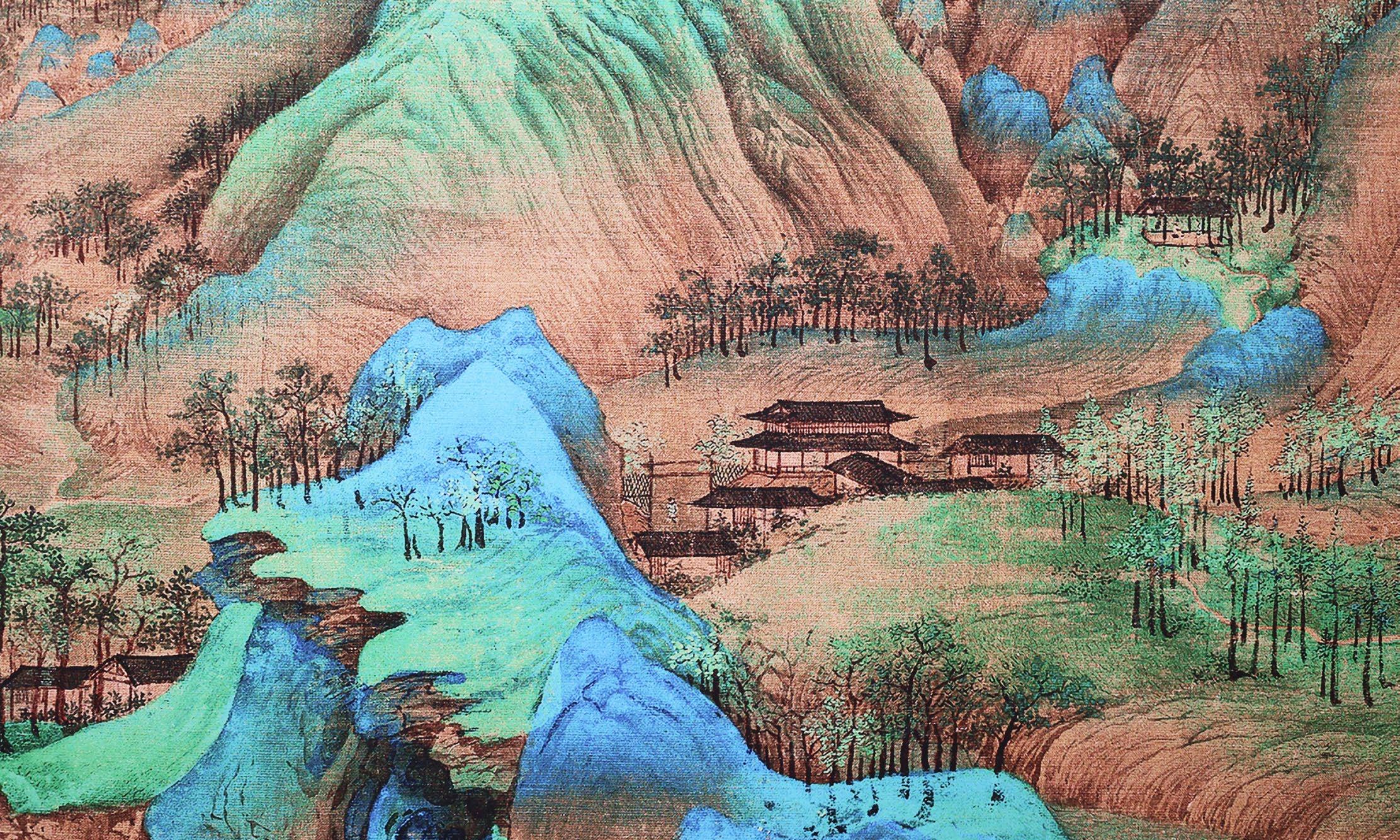

the wide entrance of the pavilion, visitors came to a large screen that projected an address by Chinese president Xi Jinping. One of his first statements was to congratulate Dubai on this first Expo in the Middle East. On a nearby wall was a portrait of the Chinese president meeting with Sheikh Mohammed al-Maktoum. China’s theme for the Expo was “Build a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind – Innovation & Opportunity.” That wasn’t elegant, but it was crowded with ideas. China was laser focused (beginning with this speech) on promoting its hopes for partnerships with other nations and for “win-win” global outcomes. But the true theme of the pavilion was China’s modernity. As visitors moved further into the pavilion an argument

unfolded that China was reaching a level of smart urban infrastructure beyond what any other nation has accomplished. High speed trains run through the landscape; resources are seemlessly distributed. But at the entrance we encountered this grand tapestry pointing us back to a traditional Chinese landscape. It was a moment of stillness that reminded visitors of China’s history and prepared them for the gleaming vision of the future to be entered shortly. The United States called on its National Parks, and China similarly grounded itself within a vision of a harmonious natural past. Both portrayals of the natural world were anchored in the past, and appeared to offer little help for the environmental challenges of the present. In 2021 China had

reached Mars with an orbiter and landed its rover “Zhurong.” This marked the beginning of its interplanetary exploration, and the China pavilion began with this widescreen demonstration of its accomplishments in space. The global powers felt the need to showcase their space programs. Ignoring space meant a nation fell short of being a true global power, and was perhaps just another place trying to entice tourists to visit and spend money. Images of satelites and this (cute!) Mars rover made China a part of the Global+Space club of nations. The narrowness and predictability of all these national stories came as a surprise to me, but it shouldn’t have. The United States wanted to talk about inventions like the telephone, automobile, and iPhone, but

China was all about infrastructure. Visitors could step into the control room for a high speed train, and gaze at the hi-tech dashboard. Displays like this one showed seamless connections between petroleum sources and refineries, and the forward movement of energy to large manufacturing centers. The traditional Chinese landscape might be notionally present in those mountains on the left, but everything else has become productive. The screen right behind this display touted the tight integration of policy, infrastructure, trade, and finances. The good life was summed up by the phrase “smart life.” Smart technology would keep track of things and makes our connections easier. But this concept has been taken to another level in

China’s version, where every need is anticipated and watched. A nearby screen showed the case of a person walking out of an apartment and falling down the stairs. Outdoor sensors see this emergency and notify paramedics, who show up right away. The deeper message is that life will be convenient but always closely monitored. Like so many national pavilions, China presented an

image of a modern city. The skyscrapers appeared as impossibly sleek structures of twisting metal and glass. It would all be complex, but technology would get people around and make life work. This kind of shining city represented the end result of all that infrastructure and production. The US had connected its global products to the work of individuals, as if modernization was thanks to genius inventor-artists. China never mentioned an individual in its portrayal of this coming world. Its infrastructure, trains, and this city wouldn’t be the inventions of individuals like Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, but the results of a superior system. National pavilions told the same basic story, but in this focus or lack-of-focus on individuals I discerned a real

difference in national systems. Switzerland provided a short-form version of the standard national story. It began with the pavilion design, which should feature a modern design sensibility, making little (if any!) reference to tradition. The Switzerland pavilion was a grand mirrored rectangle. “Switzerland” and its white cross were reflected off the ground onto the indented front. No fancy sunscreen shaded visitors, instead everyone was given an unbrella. The sight of these red umbrellas and red turf made for a surreal visual effect. Pavilions were meant to make visitors stop in their tracks and say: “Wow, that’s cool.” Inside visitors entered a thick fog. We could at first dimly make out people ahead of us, but before long we were just following the dim

light of a switchbacking mountain trail. The coolness of the fog came as a relief after the focused sun in front of the mirrored cube. The sensory deprivation reminded us of a disorienting experience designed by Olafur Eliasson for the Tate Modern in London. The Swiss were embedding their national story within the most avant garde design sensibility of our time. It’s not a framed painting that many contemporary artists work to present to museum-goers, but a total sensory experience. The pavilion incorporated that aesthetic and after the overload of the Expo grounds asked visitors to place themselves within a chamber of sensory deprivation. We were hiking through a cool mountain forest. Before long we had climbed out of the fog and looked out

on a spectacular landscape. Mountains upon mountains extended to the horizon. So far it was only this experience on offer, but it represented a successful nudge to imagine ourselves in another place. With the exception of some national pavilions that had no ambition other than to present themselves as tourist destinations, the national script called for saying something more. This experience of arriving at a mountaintop couldn’t be left alone, but had to be followed up with a lesson about globalization, and that move turned out to be the conceptual straitjacket for the pavilions. After the mountaintop we headed down, and had an easy escalator. What was the meaning of the fog and that view? We got the answer right there on the smooth wall of the

escalator: “the most innovative nation in the world.” The design work of the pavilion carried this implicit claim, but it was now stated explicitly. Every nation wanted to connect themselves to the abstract power of innovation (though no other made the claim of being “most innovative”). No alternative language exists for speaking about national aspirations than “innovation.”

No nation used their pavilion to speak about justice, faith, or even Democratic principles. National success came from plugging into the global institutions that unlock individual (or systemic) creativity. The Swiss landscape had raised our sights, and the claim about being the most innovative country in the world had raised our expectations, so it was a disappointment to arrive

on the ground floor and find small exhibits about recycling. Creative design in this pavilion had reached a peak, and it was easy to imagine the young designers having fun as they worked on this pavilion. But they had no “so what” to deliver at the end. They presented no overarching good toward which we were all working. The only large goal is “Hey, we’ll do better recycling and making sure our design concepts are carbon neutral.” This was the conceptual hollowness in all the pavilions when it came to the final “so what” point. If the end goal for all this design is better recycling, then why build anything at all? Why not just refuse to build a pavilion or skip the trip to Dubai? We needed something besides “less waste” as the reason for all this construction.

Leaving the pavilion we came to a straightforward advertisement for Switzerland. The ad presented tennis star Roger Federer (a Swiss national) standing contentedly in an alpine forest. We imagined Federer in his normal life on the tour beset with competition and other demands on his time, and Switzerland represented a place of natural peace, “without drama.” The global economy at the Expo appeared to be composed of nodes (Dubai) and edges (Switzerland). Nodes presented bold maps with lines radiating out to form connections, while edges strove to be an escape from that global drama. In this ad a global celebrity enacts the privileged movement from node to edge. If the national pavilions converged on a single story, the same can

be said about the Expo as a whole. The Expo included three themed pavilions, and here on the left is the Sustainability Pavilion, also known as Terra. The online guide for the Expo describes the theme of this pavilion: “The future of Earth hangs in the balance and there’s no planet B.” Every amazing thing visitors see in the UAE was built with massive profits from fossil fuels and vigorous participation in globalization (container shipping, air traffic). Would I discover a shade of difference between the national stories and the larger story of the Expo? The answer turned out to be a solid “No.” As with many of the national pavilions, the Terra Pavilion was designed by a European design firm. The UK based Grimshaw specializes in projects with

environmental themes, and the locations of their projects range from Doha, Qatar to Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. The various project names give a sense of the ethos: Earthpark, The Eden Project, Watershed, etc. The Terra Pavilion gets the highest possible LEED certification for sustainable design. The nearby Energy Trees and the main structure carry at their top arrays of solar panels, and they shift through the day to follow the sun. This solar energy covers a large percentage of the pavilion’s energy needs. The winding path that served as an entrance to the Terra pavilion was surrounded by thriving desert plants, and along the way we passed a series of concrete statues of fauna that once inhabited the Arabian desert. It was hard to imagine

elephants here in Arabia, but with a Google search for “elephants Arabian peninsula” I came immediately to an article about a 2012 discovery at a site in the UAE of fossil footprints for a herd of extinct four-tusked elephant that had once tramped through here. These elephants were joined by similar statues of an ostrich, cheetah, and camel, and together these evoked an ancient un-global past for the region. In other words, the UAE had once been home to a specific and remarkable environmental niche.

Most of the Expo worked to connect the UAE to global storylines, but here there was a hint of a local story. But with the prospect of soaring temperatures throughout the Gulf region in coming decades, all this past life can only exist in the imagination. Along

the glass wall of the entrance upward trending lines charted global human development. The five lines traced growth in agriculture, energy usage, carbon emissions, population, and global GDP. The point is that after a long period of slow increase, these measurements take off with exponential growth before 1900. This is what has transformed the world and makes many believe we’ve entered a new geological era, the Anthropocene. The point of the Terra pavilion was supposedly to point out ways to live that are more friendly to the environment. That’s a tough message to deliver at a World Expo, since Expos are themselves tied to that rise of the Anthropocene. The first World Expo was held in London in 1851, and so Expos are directly associated

with the exponential growth in production that led to climate change. The genre of the World Expo is—to say the least—a poor vehicle for criticism of the global system. The Terra pavilion did manage to leave national stories behind and speak for nature.

It told the story of forests in a way that closely resembled the ideas of Suzanne Simard, whose book Finding the Mother Tree had come out this same year. Most likely pavillion designers knew her earlier TED talk “How Trees Talk to Each Other.” She had argued that old growth forests don’t rely on competition but cooperation: “...underground there is this other world, a world of infinite biological pathways that connect trees and allow them to communicate and allow the forest to behave as though it’s a

single organism.” The Terra pavilion explained this by likening forests to our internet—the “wood wide web.” Like the national pavilions, the Terra pavilion couldn’t do without screens. The obvious design move was to animate on long screens the roots of trees linking up with fungal mycorrhizae. As I look back at my images from the Expo, I’m always surprised at how difficult it was to take a photo without someone being in the image taking a photo on their own personal screen. There was this endless dynamic of screens capturing images on screens. But the knowledge about forests gained by Suzanne Simard came from intimate and long presence in the forests of British Columbia. We don’t need better animations, but more willingness to just let

things be. At the heart of the Terra pavilion was this phantasmagorical “Hall of Consumption.” It was filled with bright signs and hands-on exhibits for kids. The stated idea was to challenge visitors, young and old, to reconsider their habits of consumption. This might have made sense wherever the exhibits were designed, but we experienced the hall with a feeling of irony regarding its location in Dubai. The name “Hall of Consumption” could well be applied to the entire city, which has staked its entire future on global consumer desire in the form of malls, tourism, and shipping. But any city with the global reach to be the setting of a World Expo will be a poor messenger for a Green gospel. One of the exhibits in the Hall of Consumption was this large

walk-in closet that contained a long line of men’s and women’s outfits. The floor was littered with boxes of fancy shoes. A nearby sign explained that 2,700 liters of water are used to produce cotton for just one t-shirt. A raging video image of a waterfall helped visitors imagine the fresh water that went into producing the clothes in this closet. The take-away was that we should buy less clothing and be content with a smaller closet. But how can that message be credibly preached in Dubai? If we were to name the sites that most forcefully presented consumption as a global good, we’d set Dubai high on that list. Every Expo visitor has already or will soon visit the Dubai Mall, since that’s just part of what one does in Dubai. It would be a toilsome task to go

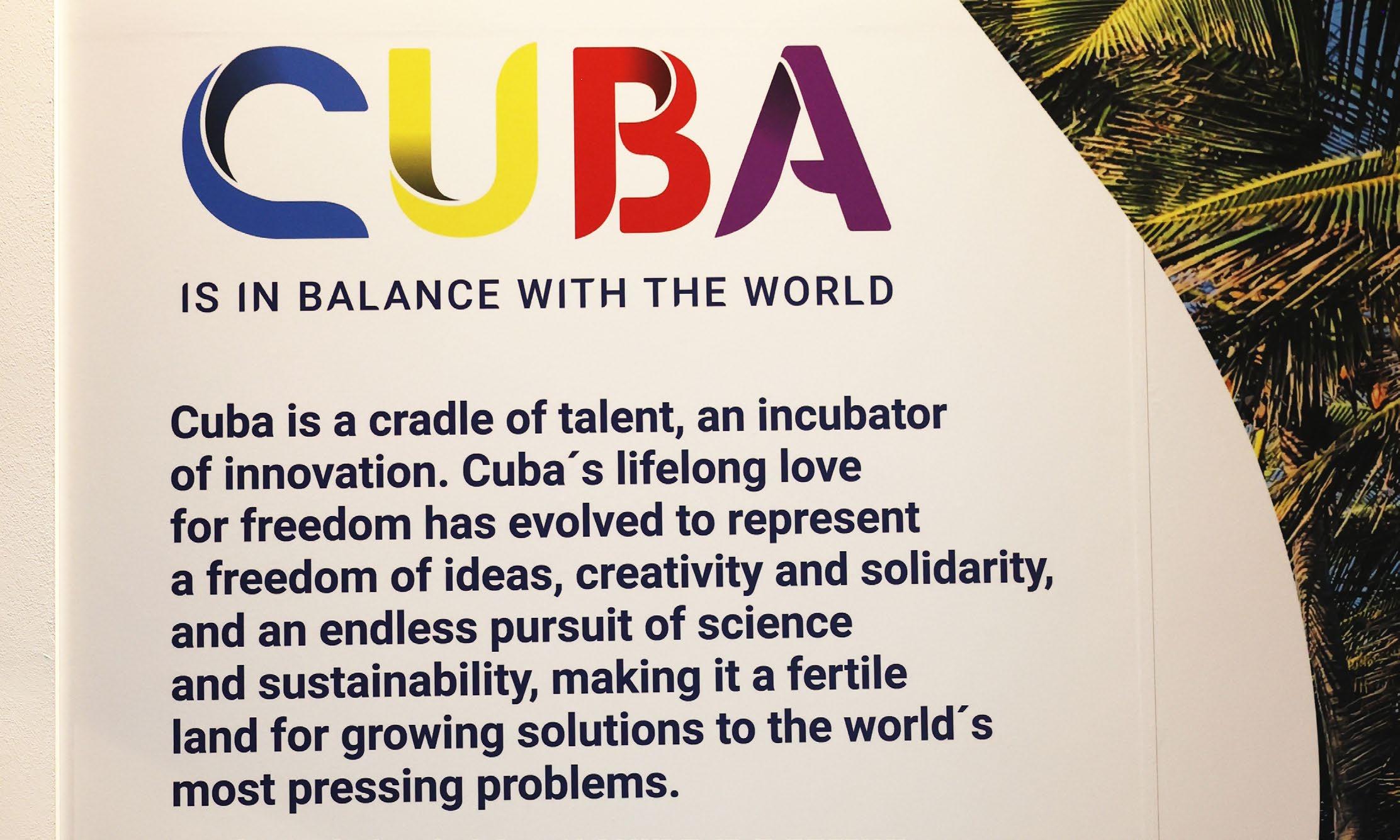

through every national pavilion, not just because it’d take a long time, but because they quickly started to repeat themselves. Each national story was filtered through the cultural sensibility and values of its people, but the main points converged. We made an effort to visit the pavilions of countries that might possibly have a counter story—Cuba, for example. Maybe we’d find here an alternative story of the nation and globalization. Cuba had a modest pavilion, but the language was exactly what we’d expect if Silicon Valley cast-offs had colonized the island. Cuba had now become an “incubator of innovation” taking advantage of freedom and creativity. Dubai had underwritten the expenses for smaller and poorer countries like Sierra Leone, which

might not otherwise have had the resources for a pavilion. Such nations were grouped together in subdivided buildings. The options for creative presentation were limited. We wondered how a small nation would relate to the dominant themes of the Expo. Sierra Leone presented itself as a place for investment. A display read: “Low operating costs and streamlined effective administrative process makes Sierra Leone an attractive destination for Foreign Direct Investment.” Investment was the appeal of left behind nations who were striving to build connections to the dominant global nodes. These countries worked to convince visitors that they were working hard to engage with the global economy, and if you invest now, you’ll possibly see great

dividends! It was clear from all the Saudi billboards in Dubai that the large kingdom to the south was fascinated by Dubai and its Expo. This first Expo in the Middle East offered the Saudis a chance to present themselves to a global public. Three Saudi flags waved above their pavilion entrance. Where the flag of the UAE features the Pan Arab colors white, green, red, and black (making it similar to the flags of Palestine and Jordan), the Saudi flag acknowledges no ethnicity. It’s green stands for Islam alone and the white Arabic lettering proclaims the central Muslim creed: “No God but God and Muhammad is the Prophet of God.” An old-fashioned sword rests under those words. The Saudi pavilion represented movement toward a new national

identity, one not so completely defined by religion. The best known image from Saudi Arabia is without question the Kaaba in Mecca, a stable and solid black cube of religious devotion. At the Expo the Saudis presented a pavilion structure which was notable for its apparent instability. It was an alien shard angled into the landscape. This pavilion was designed by yet another European design studio (Boris Micka Associates in Seville, Spain). If its flag represents an identity defined by Islam, the Saudi pavilion represents another totalizing identity, now one of placeless modernity. The Saudi pavilion included a series of text crawls. One side was in English, the other in Arabic. The phrases (the same on both sides, just different languages) were as

anodyne as possible, though perhaps the global orientation caught many visitors by surprise. “make a change” visitors were urged, or “explore new wonders.” Most of the phrases made claims as to what the Saudis were up to these days: “working towards a better tomorrow,” or “preserving the future.” Some phrases presented a disembodied ideal: “sustainable cities.” These sentiments were hard to square with the reality of a kingdom based on and supported by global fossil fuel consumption, but the Saudis had sensed an opening for themselves in discourse about Innovation and the Future. The ease with which this fundamentalist kingdom can embrace this discourse makes me suspect a parallel fundamentalism at the heart

of modernity. At the entrance to the Saudi pavilion a circle marked out a dry space to stand and take a selfie. A thin screen of water encircled visitors without splashing them at all. The falling water hit a spongy material that simply soaked it up. It was easy to imagine the marching orders for the design studio: “We’d like our pavilion to be cutting edge and modern, but still fun.”

This selfie circle partially fulfilled the “fun” part. And it worked, there was a gaggle of young people in the middle of the water screen, smiling and holding up their phones. This was more about image than reality, as these teenage girls could never dress like this in publc inside the borders of conservative Saudi Arabia. Going up an escalator into the pavilion we passed an

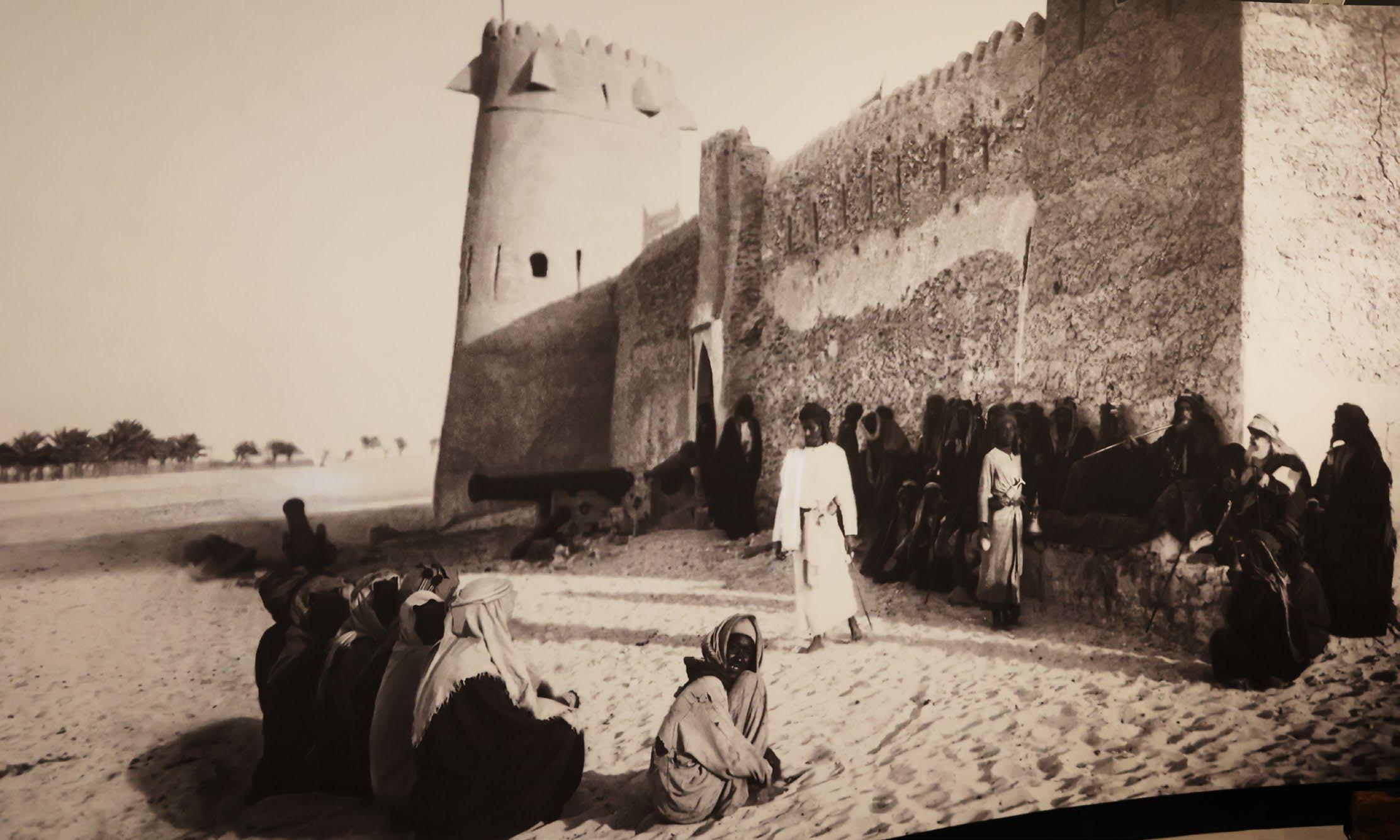

assemblage of architectural landmarks from old Arabia. That tall house with the green window screens is the Noorwali House from Jeddah along the Red Sea. The lighter tan building to the left evokes a later palace in Najran, four hundred miles to the southeast of Jeddah. It was an assemblage that conveys the broad idea that Saudi Arabia has a past. Although there’s a rough mosque among these re-creations, the purpose in all this is to play down the religious side of Saudi Arabia, making the point that like every other nation there’s an actual culture here—even UNESCO World Heritage Sites! In the official guide to the Expo the Saudi pavilion is described as a “reflection of the Kingdom’s past, present and shared future.” The pavilion led off with the

past as we escalated through Saudi historical sites. Inert walls were animated by laser projections, giving some sense of life and movement. The first was a Bedouin man in front of a fire, a camel nearby. Another projection showed a group of Saudi men in traditional white thobes, with a man beating on a colorful drum over to the left. It was a silent projection, but the men moved in unison and raise their swords together. These structures and images moved the Saudi past decisively into the category of ethnicity. Travelers are comfortable with the notion that different places bring unique expressions of clothing, architecture, and music. Seeing such difference is the attraction of tourism, and Saudi Arabia now appears ready to step forward as one more

global culture to be visited. One of the most impressive sights in the whole Expo was this landscape screen. We walked out onto what felt like a bridge, and straight ahead were slowly shifting high resolution vistas. A map of Saudi Arabia off to the side marked the location of each scene. On the interior side of the bridge we looked straight down onto the same site. This all represented the “present” of the nation, and it was spectacular, as you can tell from all the people using their cell phones to take photos or videos of the projected scenes. The pavilion was pervaded by a sense of a nation “coming out” to the global tourist crowd. Since Saudi Arabia has been impossible to visit, these scenes did feel like a revelation. Watching the landscapes shift, I

was surprised to see Mecca come up on the screen. If all those grand natural landscapes came as a surprise to visitors, everyone was surely familiar with Mecca. This sacred site is the reason Saudi Arabia isn’t open for common tourism. One of the primary duties of the state is to oversee the Hajj, which draws over two million pilgrims. The legitimacy of the Saudi state has long been based on its overseeing of the Hajj. But now Mecca was being transformed into one out of many amazing scenes in Saudi Arabia. It was no longer the sacred landscape that defined the nation, but one more interesting site. Mecca is relegated here to the “present,” and so not clearly part of the future that the Kingdom is claiming. The city of the future was on their minds of the

Saudis, starting with the billboards for their new out-of-nothing city of NEOM that were plastering Dubai. The pavilion delivered this animated scene of a social gathering in their future city. The gathering was still sprinkled with men in white thobes and women in black abayas, but now there were many others. A boy seemed to gain mobility through leg braces and an older woman interacted with others from an advanced wheel chair. A black family in western clothes mixes easily here. In the back we see a robot holding forth with humans. The message was that Saudi Arabia would build the most progressive of modern societies—even down to the free robot. The future civilization would be built in Saudi Arabia. The final room of the Saudi

pavilion included this huge sphere onto which kaleidoscopic images were projected. The images shifted from undersea corals to roses to geometric shapes, but what caught my eye was this restless moment of city streets transformed into a pulsing pattern. I thought: what better symbol for the “globe” of globalization than this sphere knotted with human patterns? As an extracter of fossil fuels Saudi Arabia is at the center of global connection, but this globalization is the thinnest possible skin, and our environmental challenge is to better imagine the disruptive power of the planet on this surface patterning of human accomplishment. There’s excitement in a globe pulsing with energy, and the Expo catches some of that, but the deep planet is

largely erased from sight. The Palestine pavilion stood right next to the Saudi one. Crawling phrases like preserving the future on the Saudi exterior made for a strange juxtaposition with the Palestine pavilion, which made few concessions to the show-off aesthetic of the Expo. The exterior served as a curving canvas for an evocative line drawing of the Dome of the Rock and its Jerusalem environs. Even in its exterior design a signal was given that Palestine was not going to represent an escape from place, rather it would underline, highlight, and make bold its reality as an actual place. I’m not sure it was planned, but the Palestine pavilion offered a real contrast to the placeless future presented by the Saudi pavilion. Palestine didn’t turn to a

high-end European design company for the design of its pavilion. On its website Al Nasher describes itself as “a full-service advertising, public relations and marketing agency with offices in Ramallah, Amman and Dubai.” The pavilion exterior is rather plain, but conspicuous at its front is a double arched gateway. This looks like it could be any ancient arch, but the diamondshaped sun dial at its center proves that it’s meant to evoke a specific arched entrance to the platform of the Dome of the Rock.

At the Expo the arches are a reminder that Palestine isn’t composed of generic spaces (ancient ruins) but particular places (Dome of the Rock). The Palestine pavilion started us off with a darkened room. We didn’t face screens, rather a series of

glowing images, seemingly back-lit. A Palestinian guide interpreted the scenes, describing the religious diversity of Jerusalem’s old city. What caught me by surprise was her point that the floor on which we were standing was created out of the same stone as the street we were looking at in the old city. This wasn’t an appeal to the antiquity of the street or the stones, just an invitation to feel like participants as we visited the Palestine pavilion. The paving stone of the pavilion floor merged into the still image, and we had a sense of presence but also a counter sense of the limitation of our imagination. The actual Old City of Jerusalem is a kind of metaverse avant la lettre. A pilgrim enters it and starts to live in a parallel time. The Jerusalem that Jesus knew and

which witnessed his passion was obliterated by the Romans in 70 AD, but the city was wholly re-imagined by Christians in succeeding centuries. The Via Dolorosa was not in place in Jerusalem until the 15th century, but visitors who come to Jerusalem and follow the path of the suffering Christ can become overwhelmed with a sense of “being in the very place.” At various points there are cutouts on walls or along streets where visitors to Jerusalem are invited to see into the past, or even to touch the past.

This raises a question about designing a pavilion for the Expo: how could this tactile spiritual world ever be represented to visitors? The designers for the Palestine pavilion made the startling choice of connecting to history and the human senses. We

saw no images of future cities, but rather relics of the real Palestine. A label underneath this scrap of metal read: “An original aluminum piece from the old structure of the Dome of the Rock. Now you can touch a real part of the Dome.” This metal was attached to a stand by a thin wire (so visitors wouldn’t walk away with it). Underneath was a certificate of authenticity. The France pavilion gave visitors a “Notre Dame Experience,” featuring huge photos of the ongoing restoration process. But for Palestine the piece of metal was more important than any virtual tour of the Dome of the Rock. The Palestine pavilion gave no evidence of being entranced by the great city of the future. They shared no imagined hi-tech city with skyscrapers. The land and

its produce was a major theme, which set up another sensory display: a pot that gave off a wispy puff of scent when a visitor leaned over it. For example, the man on the right wearing a keffiyeh holds guava in his hand, and the small pot in front of him delivered the smell of guava. It was a display that was innovative in its own way, but which delivered a message quite at odds with other pavilions (like the Saudi one): Palestine isn’t a nation attempting to transcend place, but one striving to remain an actual place. Things produced by the land are one proof of being a real place. The project of presenting place through the five senses broke down when it came to taste. It wasn’t possible to present visitors with a delicious mezze platter of olives, hummus,

cheese, figs, and fresh fruit, but a large photo reminded us of the role of food in constructing regional identity. There was no claim here to the presence of anything innovative. This was no new style of hummus or olive or orange juice. It wouldn’t require an accomplished chef to create a spread like this. This was a vision of a common table with common foods. Like all other aspects of human life (clothing, music, art) food easily becomes a signifier for identity, and this photo delivered a clear message about the placed reality of the nation of Palestine. At the conclusion of the Palestine pavilion we entered a room in the clouds (at least with clouds painted on the walls). Five white stations had a VR headset, and we stepped up to the nearest one. Arthur

put on the headset and started looking around. I took a turn after him, not sure what to expect. Was this the point where we would be taken to the future city? The headsets instead took me to a quiet, peaceful scene, looking out on a small body of water, desert hills in the background. A bird was chirping, I remember too. Other headsets delivered immersive scenes from the streets of Jerusalem, or religious sites, but ours delivered the image of a quiet, non-techy future. Palestine was asking for nothing more than to be itself in its own place. I’m not saying there were no screens in the Palestine pavilion—there were. But in ways markedly different from other pavilions, Palestine turned away from science fiction and asked to be seen and touched and

tasted. At the end we came to this physical map, headed by the Arabic for “I am from here.” It invited Palestinian visitors to mark their homes on the map. It made no attempt to separate Palestinian land from Israel. The message was that this land as a whole is home, with no virtual alternatives possible. The primary mode for conveying information at the Expo was the screen.

Broad, flat walls and three dimensional objects were made to pulse with moving images. Books were almost entirely absent. One exception was the gift shop of the Palestine pavilion, where we came across a selection of bilingual books by the poet Mahmoud Darwish, who is something like the national poet of Palestine. His poems take up themes of exile and loss. The pavilions kept well clear of politics, but with these books it was possible to add a deeper note to the pavilion experience. The value of books as holders for private thoughts difficult to express on public screens became clear. No public screen could represent a personal perspective and voice in the way that could be realized by these small books (though few people picked

them up). The Palestine pavilion had an attached cafe offering falafel wraps. The cook fulfilled his orders, but at the same time tried to catch the eyes of people exiting the pavilion. He smiled and motioned for us to approach, then handed us each a piece of warm falafel. Seeing my camera he made it clear I should snap a photo, and gave a friendly thumbs up. It’s long seemed to me that there’s a central Palestinian faith in the idea that if people could meet them and hear their voices, they’d think differently about their political tragedy. I fear there aren’t many places now where personal outreach manages to break through the dense onslaught of mass media representations. In 2020 the UAE and Israel had normalized relations with each other. This was the

first such political agreement between Israel and an Arab nation. Israel was present at the Expo with a small but thoughtful pavilion. The exterior was in the form of an open box. The colored panels on each side were LED screens that allowed any number of displays from within the box. Visitors could walk up the sandy trail, and along the way they passed the flags of Israel and the UAE, standing together. At the top were places to sit and relax, as if it was some desert resting place after a long hike. At the center—and visible to all who walked by the pavilion—was a nine-branched Hanukkah menorah, a religious symbol reminding visitors of the centrality of Judaism to the nation of Israel. At the back of the Israel pavilion was this glowing sign in

Israeli blue. I first guessed it was some sort of paleo-Semitic script pointing toward common Arab-Jewish roots. That turned out to be wrong—but on the right track. It was an example of the “Aravrit” script, a hybrid of modern Hebrew and Arabic. Knowing that, I could see that Arabic ran along the top, with Hebrew filling in the lower half. The Arabic read nahu al-ghad or “toward tomorrow.” The Hebrew ha-machar repeats “tomorrow.” This served as still another example of the dominant future orientation of the Expo, and as usual it stands—in contrast to the past—as the path toward some sort of peace. The script embodied hope that Israeli and Arab hopes for the future could be harmoniously combined, but friendship among nation states would be cold

comfort for Palestinians. From the Israel pavilion we looked back on a corner of the Expo. The SpaceX rocket stood on the left, and next to it was the pavilion for the global shipping corporation DP World. The linked screens within the Israel pavilion had now changed to highlight areas in which Israel was contributing to the global economy. Israeli researchers were applying Artificial Intelligence to diagnosis, so health outcomes would improve. It was a tableau of globalization and its promises, but it was also tired: more containers, more space, more AI, more promises about the future. We had entered a tomorrow trap in which the past was left behind as a matter of concern, and the present too barely registered. As we waited to enter the theater

on the lower level of the Israel pavilion, we were stuck watching a faux game show where a tuxedoed host asked the captive audience a series of questions about Israel. The idea was to convince us that Israel was different than expected. One question was about the number of Israeli companies considered “unicorns.” A unicorn is a tech startup valued at over $1 billion. We were shown two possible answers, and of course the correct one turned out to be the higher (though 95 seemed impossibly high). This kicked off a longer attempt to present Israel not as an exclusive nation state, but as a Silicon Valley-style innovation region. Once we had entered the small theater (no seats, everyone standing), the lights went dark and a woman stepped

forward (on screen). She began by explaining that her father’s family was Arab and her mother’s family Jewish; and her name is Lucy. So from the start we knew she was presented as an emobodiment of the cultural mixing and creative flow that marks an innovation region. She snapped her fingers and said, “At this very moment somewhere around the world a new idea was born.” She snapped her fingers again, “And another one, on the other side of the world.” These ideas will take us into the future, and they will form the content of the future as they gain form and reality. The screens dissolved into scenes showing the openness and diversity of life in Israel. The theater had one live actor, though he had no elaborate dance routine. He played the

part of a DJ behind a console of screens. The on-screen Lucy had asked the audience at the start: “Can’t find the right tone?” Her appeal was to young people who lacked a firm identity, who felt out of place. Lucy came round to another idea, “Forget about the right tone, people, follow the beat.” At that moment the DJ acted like he’d let loose a torrent of electronic dance beats, and we were in some club (though actually this was all just part of a choreographed show). These beats weren’t the property of any nation, but of young people everywhere, and the beats represented a kind of ethos of the future that anyone could join. By the end of the video presentation we were surrounded by young people on the screen adding their unique voice or instrument

to the music. We got it: Israel is a place where creative young people can express themselves and so create the future. The presentation represented an open hand reached out to other creatives in the region. The sociologist Richard Florida has written about the rise of an educated “creative class” in the United States, which has taken up residence in prosperous cities. This pavilion posited a global version of this creative class, living in nations that nurture their presence (if not providing actual citizenship). The trick is to be able to forget the past and merge with the placeless global beat of modernity. There are financial and personal rewards for commiting oneself to the future, but there is also a cost. The Israeli flag took up the entire surround

screen briefly at the end of the program. It was a reminder that this was the pavilion of a nation state. But all this content was hard to distinguish from what we’d seen in the Saudi pavilion. This program had been set on a smaller scale, but it reached for the same keywords (innovation, diversity), and it was oriented around the concept of the Future. The Israeli national project was clearly coming into alignment with other states in the region. The point wasn’t democracy or citizenship, but rather in creating the conditions that allowed for the prospering and at least temporary residence of young people who knew themselves to be the creative class, and who would in turn find and refine the ideas on which the Future would be built. The Expo wasn’t

an occasion for staking out a unique national ideologies, rather it was a chance to plug into the global consensus, to show you were on board. This was evident in the embrace of what I’ve called the Future Ideology, orienting value in the Self and what is to come. The ideology can be expressed in a graph:

At the Wisconsin college where I teach I found an oversized photo book about the 1893 World Exposition in Chicago. The book contains photos of that Expo’s pavilions and landscapes, but focuses on the public art and architecture. It was published in 1894, and inscribed on its opening page to “Barbara” from “Grandpa” (who no doubt had visited the expo). The 1893 exposition attracted over 25 millions visitors, and by most accounts was a truly successful example of this signature type of global event.

I’ve used this book to imagine what it would’ve been like to walk around another expo 130 years ago, and as an aid to ponder shifts in concepts like Self, Nation, and Global. Visitors who arrived at the Expo by steamer entered behind this peristyle, which

had at its center a grand arch that vied in size with the Arc de Triomphe of Paris. With that massive Statue of the Republic in the foreground, this became an iconic scene for the Expo (and one often reproduced). There’s no better place than here to start thinking about shifts in meaning between this 1893 World Expo and the one in our own time in Dubai. We could begin with the fact that the architecture in 1893 represented an effort to perfect past classical styles. There was nothing “modern” about the design efforts. Another point is that while the statues reached for abstract meaning, they never ventured away from a realistic style. That statue group on top of the arch portrayed Christopher Columbus in triumph. Today the reputation of Columbus is

in tatters and he’d couldn’t headline a building (let alone a global event!). At the other end of this main basin, facing the Statue of the Republic, was this Columbian Fountain. The group was an allegory of the New World figuratively opened up by Columbus. The design of the underlying ship was drawn from the Spanish caravels on which Columbus arrived in the Americas in 1492. Father Time steers the ship at the rear, while Fame stands in the bow publishing far and wide this accomplishment. Sitting at the top, on a kind of uneasy pedestal, is the maiden Columbia. She generically represents the advancing and triumphant spirit of the New World, and those maidens with oars represent propulsion by the arts and sciences. The Midway Plaisance was the

long corridor that ended with the world’s first Ferris Wheel. The wheel was designed by an engineer with the last name of Ferris, who from Pittsburgh answered a call to develop a novel structure that could equal in the public imagination the Eiffel Tower of the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. The Dubai Eye wasn’t constructed on the Expo grounds, but it clearly evoked expos of the past. This idea of designing a novel structure that could stand as a symbol for a place continues to our time. We could even say that over the past 130 years this special goal of the World Expo to find a unique and iconic structure has been generalized until it is the goal of all cities. The global city has become an ongoing World Expo, though somehow the format of

the World Expo continues! The World Expo had come to the United States to celebrate the quadricentennial of the arrival of Columbus in the Americas. Statues on the grounds took up this theme, but there were other ways Columbus was made vivid to the imagination of visitors. Replicas of the authentic caravels were built in Spain and transported to Chicago over the Atlantic and through the Great Lakes (towed by US Navy ships). Above is the Pinta and the Niña, moored to the agricultural building.

The ships drew crowds, who must’ve marveled at how a momentous cultural encounter was driven by these small wooden ships. The boats remained in Chicago after the Expo, but deteriorated over time. One peculiar structure was tucked away on the

grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition, facing Lake Michigan. It was a replica of La Rábida in southern Spain, the monastery to which Christopher Columbus made a retreat after being turned down by the Spanish crown for his proposed voyage. The structure had an austerity that made it distinct from the wonderland of architecture at this Expo. The souvenir book noted that Columbus came to La Rábida in his “hour of darkest trouble.” The structure’s austerity thus functioned as the backstory for the wealth and design exuberance of the Expo: an austere faith had engendered the success of the New World. The structures and pavilions of the Expo in Dubai rejected traditional design elements, but moving back 130 years a wholly

different design philosophy reigned. Walking in this colonnade, for example, a visitor was surrounded by motifs adapted straight out of the Classical past, including fluted columns with Corinthian capitals and a coffered ceiling with rosettes. Photos like this give a permanent appearance to the temporary and destructible white staff out of which all these Expo structures were made. This classical design didn’t reflect the actual past of Chicago or the United States (or the Spain of Columbus), it’s the past that had become the standard symbol for “civilization.” It is evident that in 1893 the Future had not yet wholly banished the Past. The central Expo structures gave expression to Neoclassical or Beaux Arts design values, but the national pavilions drew

from older regional styles. The German pavilion was designed by a German architect and mixed together a variety of styles to create a dream vision of a traditional German town hall, or rathaus. The statue beside it (with lamp held aloft) portrays Venus rising from the ocean. It’s here to show off German metal work, which was of course expressed in the shared language of

classicism. The Expo in Dubai had 191 national pavilions (an almost exact match for the 193 nation states in the UN). Moving back to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, we find ourselves in a global world with a quite different organizing principle.

The central international buildings were built by European nations with colonial holdings, and these were supplemented by nations (like the Ottoman Empire in this case) striving to be seen as peers. The Turkish building was a recreation in wood of a Fountain near the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. On the interior it featured a sixteen foot long torpedo, demonstrating industry and military power at one and the same time. Guidebooks to the World’s Columbian Exposition explained that the the Turkish

building was a re-creation of the fountain of Ahmed III in Istanbul. This 18th century fountain stands at the entrance to the Topkapi Palace, and looks like an inset jewel with its marble details and tiling. It’s a “fountain” in the sense that it served as a dispensary of drinking water. The Turkish building at the 1893 expo, with its wooden sides and Arabic banners, was a very loose replica of this original fountain. This path of representing the nation through the reproduction of traditional architecture had been wholly dropped 130 years later in Dubai, where nations presented themselves in traditionless but innovative designs. It was no longer a virtue to mimic the past. The India building was crowded with goods from India. In 1893 India was ruled by the

British, but in 1885 the Indian National Congress had been formed, so there was a growing view that the subcontinent was a nation in its own right. A group of Indian merchants funded this building. The one sign I can read (on the left) labels a “Budhist Idol,” so there was a religious statue on display there. Small frames appear to present images of temples and religious structures. The interior is crowded with textiles and other goods (likely for sale). Visitors wandering into this space from Chicago or smaller cities in the Midwest must’ve felt a thrill to walk into this crowded foreign space. It’s impossible for me to look at photos of the 1893 Chicago Expo and not think back to our experience at Expo 2020. The India pavilion in Dubai (after an opening about

space exploration, naturally) focused on ancient religious structures. Religion sits at the heart of the national identity of modern India, something that isn’t true for other great powers. This self-conception was present even in 1893, but in 2020 that ancient past is displayed by means of cutting edge digital technology. Screens do most of the work and signal modernity. Walls are illumined (and then multiplied by mirrors). In the photo it’s possible to make out a model of an ancient temple behind a glass display box. An informational tablet stands ready for visitors to swipe with their fingers and get facts about the temple. The screens and tablets have entirely replaced the framed prints and sample manufactured goods that dominated in 1893. Along

the horizon the great White City of the 1893 Chicago Expo stretches out. Its domes and massive exposition halls take on a dreamlike grandiosity. That was the place for the leading nations and industrial exhibits. On the way to that White City many visitors walked down the Midway Plaisance, a wide street that contained some of the most popular parts of the Expo. On the right we glimpse the Turkish Exhibit, which included a model mosque. Beyond that is the drum of the Alps Panorama. On the left is the German Village and the Javanese Village. At the end was a “Beauty Show” where a large sign enticed visitors with the promise of “40 Ladies from 40 Nations.” These attractions from the Midway Plaisance haven’t aged well, and are as impossible

to imagine today as a glorious statue in praise of Columbus. The previous photo of the Midway Plaisance was taken from the Ferris Wheel. This one is a look back at the Ferris Wheel from the wide Plaisance. From the street level we easily feel its popular appeal, offering a faux experience of global cultures. Disney’s Epcot could be seen as a cleaned up (no sex, no religion) version of this experience. Culture, people were learning, could be a show. The following is a description from the photo book: “In one and the same minute the visitor meets the fair-haired Laplander or Scandinavian from the north and the black-eyed and swarthy-faced descendant of Latin stock or native of South Africa.” On this street it wasn’t nations on display, but cultures. The