10 minute read

chapter two

erasure.

fig. 2.1

Advertisement

'Ostalgie' Goodbye Lenin, 2003

“One may say that Berlin has always been a self-destructive place in which successive regimes have attempted to wipe out the built symbols of past regimes” - Claire Colomb

In Wolfgang Becker’s 2003 film, Goodbye Lenin the story is recounted of Alex, a young East Berliner striving to protect his frail mother from the news that the Wall had fallen whilst she had been in a coma for the entirety of the Wende. As the West rapidly creeps in over the East, we view Alex taking ever more drastic steps to recreate a fictitious version of the DDR to save his mother from knowing the true fate of the country she had adored. By doing so the film explores the rose-tinted nostalgia that many East Germans held onto for their lost socialist Heimat - homeland. As such we see Alex struggling to revive icons of Eastern culture against a tide of Western consumerism. When his mother at last ventures out onto the streets of a reunified Germany, she is met by an unfamiliar built environment dominated by the visual sensations of the new capitalist order. We watch as she takes in the sights of Wessis moving their exotic furniture into her apartment block whilst on the street, Trabant cars are being traded-in for their superior Western counterparts- all to the backdrop of a landscape of billboards promoting new brands and lifestyles. As the scene reaches its crescendo, the mother locks eyes with the statue of Lenin being removed from the city by helicopter [fig.2.1]. [29] Although exaggerated for cinematic effect, the moment is telling of the level of cultural erasure that the East experienced through its physical environments, and the often traumatic personal loss this entailed for the Ossis. In a wider sense, the film can be identified as being emblematic of the wave of Ostalgie: nostalgia for the former

DDR that grew throughout the Post-Wende period. [30] The emergence of this phenomenon has been identified as reaction to the agressive manner in which critical reconstructionists, of a largely western dominated city administration embarked on removing all legacy of the symbols of the DDR.

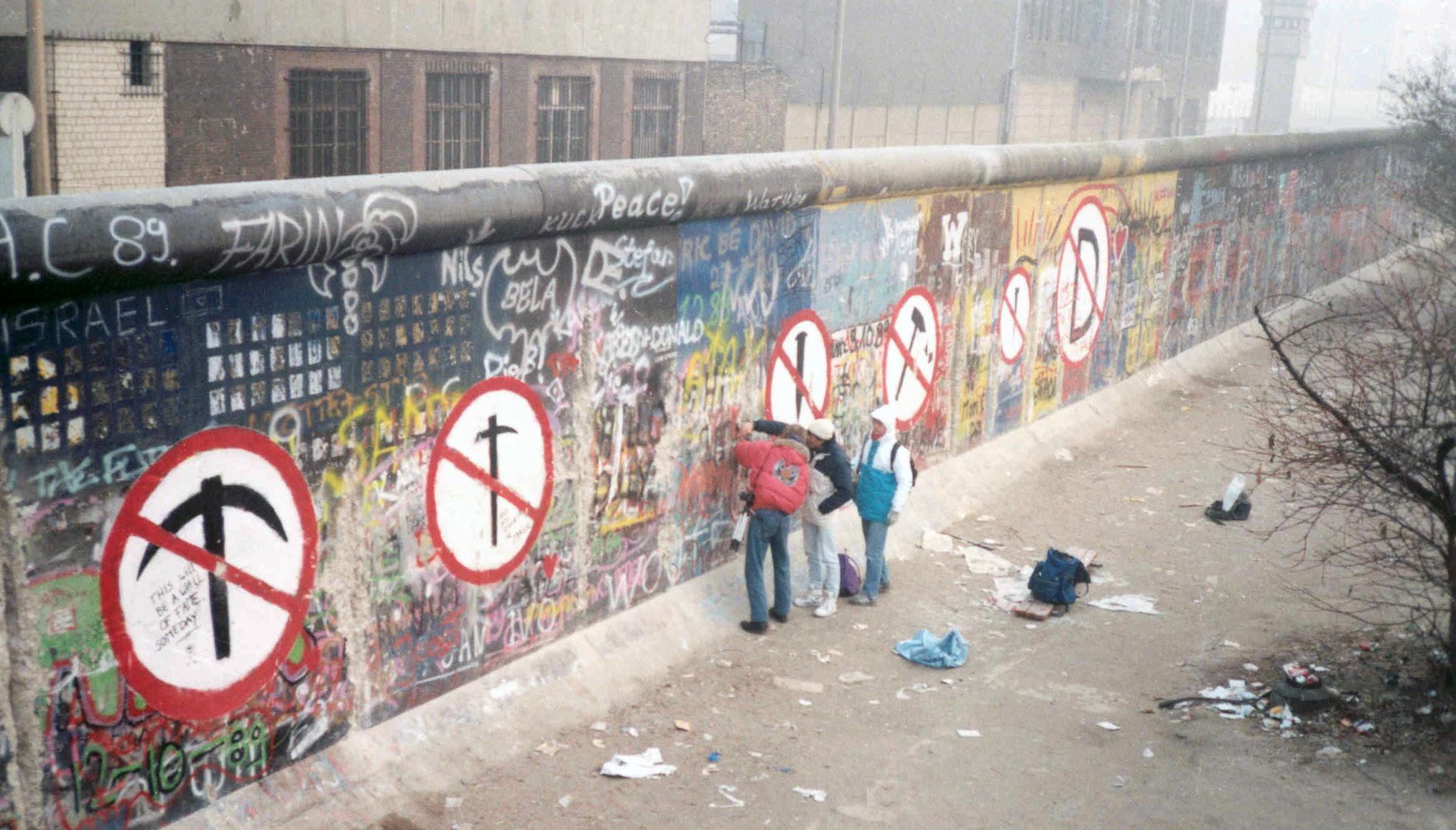

Erasure of the East began the very night the Wall fell. Within hours of the opening of the border, the physical infrastructure of the divide had begun to be metabolised by Berliners from both sides. The Mauerspechte - ‘wallwoodpecker’ came to describe the legions of people who engaged in a frenzy of ritualistic chiselling at Wall's symbolic concrete for weeks following the event [fig.2.2]. As Ladd comments it was in this ‘carnival atmosphere that the concrete was divested of its murderous aura’ [31] . As a final act of triumphalism, pieces of the wall became a highly sought after commodity amongst locals and tourists alike. Symbolistically portraying communism’s loss to western capitalism, the structure defining the twentieth century’s largest confrontation, turned ornament for the mantel-pieces of the West.

[Monuments]

In the sense that the Wall carries a weight of historic and symbolic meaning for the story of Berlin, it must be viewed as a monument albeit an unintentional one, that speaks of a period of violence, terror and division. Understandably for most Berliners, the destruction of the Wall acted as a form of catharsis to the past forty years and its total eradication served as a means to heal their collective identity. Voices campaigning to memorialise sections of the wall often faced strong objections and by 1991 most of the physical

fig 2.2

Mauersprechte 1990

presence of the structure had been removed, dumped on the edge of the city and ground to rubble [32] . Ladd’s discourse on the nature of public memory in Berlin speaks of the highly politicised nature of the physical landscape, and how like many monuments in the city, the Wall acted as a source of contention amongst a public grappling to make sense of what to remember and what to forget [33] . In the years following reunification, like the Wall, monuments of the East became the target for eradication due to their lingering effect on the collective memory of the urban space that hosted their presence.

For the DDR, monuments played an enormous role in the functionings of daily urban life. Unlike the West, it was not constrained by an aversion to symbols of statehood and national pride owing to its asserted allegiance to the cause of anti-fascism. Whereas the Federal Republic definitively ceased the practice of monument construction after the terror of Nazi nationalism, the DDR followed Soviet Russia and Eastern Bloc states in its adorning of the built environment with sites of celebratory remembrance. Leading one observer to describe the condition as ‘West Germany was a land of victims,’ and ‘East Germany a land of Heroes’ [34] . East Berlin was therefore scattered with hundreds of memorials, plagues, statues and street names in commemoration to those individuals and events that embodied the aspired principles of socialism. Naturally the differences between East and Western attitudes to memorialisation proved to be a focus of post-unification disagreement and invoked mass public debate over their future.

One of the most contentious GDR monuments proved to be the twenty metre tall statue of Lenin in the square of Leninplatz [fig.2.3]. Having been designed by Soviet sculptors, employed the aesthetic of socialist realism on monumental proportions. The proposed removal of both these monuments came to be a source of extreme conflict along the former East-West lines and highlighted a faction of former Ossis who clung onto the monuments more for their symbolic representation of DDR history, as opposed to their personal admiration of the individuals. Consequentially the dismantling of the Lenin statue and renaming of the square to Platz der Vereinten Nationen- United Nations Square in 1991 invoked anger and protests at the site [fig.2.4]. The behaviour here embodied a mood shift as the initial euphoria of the Wende was beginning to be replaced by feelings of loss amongst those from the former East. This backlash against eradication led the critical reconstructionist city government to adopt a more sensitive review of the handling of DDR monuments, as shown by the eventual sparing of many of the relics marked for removal.

[Street Names]

As the debate over the urban legacy of the DDR moved to the fate of street names it became clear that former Ossis were split between those in favour of assimilation with the West and those who wanted to keep the memory of the DDR alive. The naming of streets, as in most global metropolises was for Berlin a highly politicised act that has served to bolster urban identity throughout the city’s metamorphoses [35] . During the most turbulent periods of the twentieth century, Berlin’s street names have been intrinsically tied to the political hegemonies of their conceivers- owing to their innate ability to demonstrate political influence upon the lived experience of the individual. Re-naming streets has thus typified the key exchanges of power in 20th century German History, being a quick and easy method to exert one’s claim to the built environment. Arguably the most co-ordinated effort to revise street names took place during the twelve years of National Socialist rule. Here an aggressive Arisierung - aryanyzing of urban space was employed through the adoption of names commemorating prominent Nazis (notable examples being the Adolf-Hitler Platz, Herman Göring-Strasse) and the removal of names associated with democratic political traditions or disapproved cultures [36] .

Following the defeat of the Third Reich, administrations of the East and West set about purging these reminders of fascism from the streets by embarking on a strategy of mass re-naming [fig.2.5]. For the FRG these efforts were focused on restoring the pre-1933 street names and, for new housing

[35]__Verheyen, D. (1997). What’s in a Name? Street Name Politics and Urban Identity in Berlin. No.3 ed. German Politics & Society, pp.44–72.

fig. 2.3

[left]

Leninplatz aka: Platz de der Vereinten Nationen

fig. 2.4 [right]

Leninplatz Protest - 1991 Translation: " You FRG occupiers! Do you not fear a Lenin made of stone?"

fig. 2.5

developments, inventing names perceived to be innocent and apolitical. The DDR meanwhile saw an opportunity to use the purging of Nazi street legacies as a means to strongly affirm the identity of the socialist state. The replacement names, and in a wider sense the renaming of schools, hospitals and even entire towns, honoured a variety of figures including anti-fascist martyrs, revolutionaries, third-world Marxists and leaders of the DDR and USSR. Thus when the Wall fell, there began the next wave of revisions to the city as

hundreds of streets and plazas were ridded of their communist associations.

The Politics of Street Naming Berliner Alle 1991 name change

The debates surrounding these actions, like those of the disregarded monuments of the DDR were emblematic of the divisive political landscape existent during the Post Wende period. Supporters of the re-naming campaign spoke of a desire to forget the painful memories of an oppressive regime brought into continuous consciousness by the likes of Leninalle and Stalinalle. For many Ossis however the renaming of their streets stood as a needless example of an administration that was seeking to deny them of their own identity and collective memory in the pursuit of symbolic acts of triumph over the East [37] . Moreover many of the pre-war names that were being reinstated had equally problematic connotations with the militaristic imperialism of the Prussian era monarchy, as well as territories formerly occupied by the German Empire. Therefore the re-naming of streets brought about similar questions to that of the critical reconstruction of the city centre, namely what history was deemed to be acceptable and who was to make this decision? As it became clear that the city administration’s answer to the question of

public memory omitted any mention of the DDR, there began a backlash from former Ossis. The term Trotzidentität - came to describe a defiant identity of former East Berliners unnerved by the widespread attempts to cleanse the city streets of their collective identity [38] . Protests, petitions and mass complaints thus came to be the defining feature of convulsions over the city streets in the early nineties. Ultimately the Trotzidentität sentiments would be channeled into the rise of the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) which served as the successor to the DDR’s dominant party, the SED (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands). The gains made by the PDS in the 1994 city elections were due on a large part to the party appealing to the sensation of loss and disillusionment that those on the East were experiencing as the built environment was changed beyond recognition.

Through its local election success, the PDS managed to hinder many of the planned removals of DDR monuments thus marking a turning point in the backlash against the paradigm of critical reconstruction. However the perceived capitalist ‘colonisation’ of the East continued nonetheless to claim high profile monuments. Most notably the parliament of the DDR: the ’Plast Der Republik’ was demolished in 2008 to much furore [fig.2.3], to allow the reconstruction of the baroque-era Berliner Stadtschloss, which had once stood on this site before its ideological demolishement by the SED in 1950. This architectural tit-for-tat and the wider disputes over the future of street names and monuments in Berlin expose the interaction between politics and history. The erasure and replication pursued by certain urban actors after the Wende iterates the artificiality of collective consciousness as physical elements of the city were handpicked according to their value to a new German identity [39] .

[38]__Taberner, S. and Finlay, F. (2002). Recasting German identity: culture, politics, and literature in the Berlin Republic. Rochester, Ny: Camden House.

fig. 2.5

Plast der Republik Facade missing emblems of the DDR

fig. 2.6

"The DDR never existed" Graffiti on the demolished remnants of the Past der Republik - 2008