8 minute read

chapter three

autonomy.

fig. 3.1

Advertisement

The Love Parade 1989-2003

While the city fathers of the Post-Wende period busied themselves with the curation of Berlin’s image as a burgeoning European hub, simultaneously there existed a thriving scene of autonomous sub-cultures that arguably exerted equal effect onto the place identity of the city. Perhaps arrogantly, the notion carried by members of the city’s administration was that architecture and urban design had total power to perform a therapeutic role in reviving the city’s image. In general, discussions surrounding the Post-Wende redevelopment of Berlin dwell largely on the actions of state and private interests whilst neglecting the role of those outside the halls of governance. Throughout the turbulence of the Wende and the following decade of reunification, it is evident that the general public played an intrinsic role in the definition of the new society and its collective identity, at home and abroad. The Mauerfall, by nature was an act of public participation after the events were set in motion by citizens taking to the streets en masse and subsequently removing the wall by the individual chiselling of the Mauersprechte. As Ulrike Zitzlsperger suggests, the sensation of participating with history and the ‘feeling of having played a part in events’ is a defining feature of the memories of reunification, that in a wider sense go beyond political convulsions to describe the experience on an individual level [41] . This chapter charts, autonomous, grassroots movements equally sought to claim urban space in the reunified city; who by doing so, would in turn attract the attention of authorities seeking to manage and profit from their activities.

In the idealogical vacuum of the 1990 reunification, Berlin’s multitude of voids and transitory spaces represented a playground of opportunity for those attempting to piece together alternative urban realities. The city had long been known internationally for its music and arts scene, which owed much of its strength to the specificities of geography. As an island, the West had developed a distinct peripheral place identity permissive to liberal expression and particularly a highly innovative and avant-garde electronic music scene that would form the foundations for German Techno. The Wende would ultimately alter the city’s cultural landscape beyond recognition as what had previously been a largely Western phenomenon swept through the reunified capital capturing the spirit of a hedonistic youth in revolt. The new freedoms being experienced by the Wende generation were aided in a large part by the the peculiarities of Berlin’s urban landscape. As the DDR unravelled so too did the entirety of its state owned industries, leaving in its wake, mass unemployment in the East and a rapidly de-industrialising inner city. The landscape of vacant buildings produced by this turmoil drew the migration of young and creative individuals to the East, looking to form autonomous cultural and living spaces free from the reach of state control [42] . Accordingly whilst the city experienced its building boom, so too it underwent an explosion of club culture and squatting that was intrinsically tied to the spatial reverberations of the fall of the Wall. As those in control of the city’s marketing campaigns sought to tightly curate a normalising image of global prosperity, subculture movements were organising themselves in their fight to claim spaces of free expression and hedonism that would eventually come to dominate the image of the reunified capital.

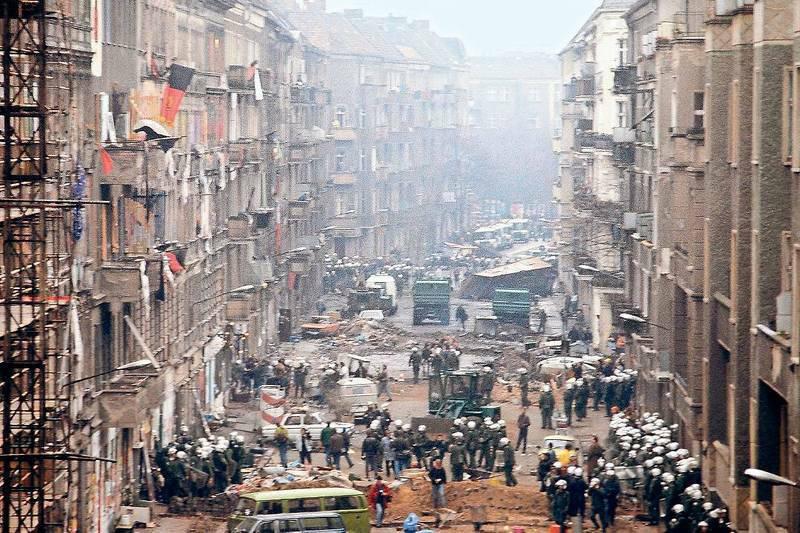

The successes of the city’s subcultures were thus bound to holding a presence in urban space as a means to claim a ‘right to the city’. 1989 to 1990 marked one of the last major waves of squatting in Berlin as hundreds of vacant buildings in the East were occupied by dissenting groups. The was seen as an inherently political act that challenged the hegemonic forces of critical reconstruction that were privatising the properties of the former East. Municipal authorities often took a combative approach in response [fig.3.2], opting for eviction by force or the negotiated settlement of its residents that typically led to properties being subsumed into a neighbourhood’s wider gentrification. In turn however, as many commentators have argued, squats came to be used for gain by the city’s numerous marketing campaigns of the late 1990s that had begun to acknowledge the city’s ‘poor but sexy’ spirit and wider creative scene [43] . Thus the transgressive act of occupation was largely reduced to a branding asset of the wider market orientated redevelopments in the city

[42]__Bader I. and Scharenberg, A. (2010). The Sound of Berlin: Subculture and the Global Music Industry. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(1), pp.76–91.

fig. 3.2

Mainzer Strasse, 1990 Police remove squatters from occupied buildings.

As the Post-Wende decade would show, this was to be a fate suffered by numerous other urban movements, most notably: the Love Parade, a techno music event that attracted millions of revellers at its peak. Arguably the most visible sub-cultural presence within urban space during the 1990s and 00s, the Love Parade had its origins in political protest yet over the years morphed into a commercialised mass festival that ultimately was used to promote the image of the ‘New Berlin’ as a ‘party capital’ [44] . The parade first spilled out of the underground techno scene and onto the city’s streets in 1989 when a group of around 150 politically motivated participants sought to use hedonism as a means of uniting the city. The medium of parade allowed the group to produce a transient public party space whilst parodying traditional militaristic notions of parading that had dominated the city’s streets for so much its history. For the first several years this chosen backdrop was the grandeur of West Berlin’s Kufurstendamm, however as techno became ever more tied to a reunified Germany, the Love Parade outgrew this setting and moved to arguably the most contested geography in all of Germany, the Straße des 17. Juni [45] .

The history of this one street perhaps speaks of the changing faces of the German psyche like no other. By origin, it had been conceived as the site for Prussian military parading and subsequently been widened by the Nazis to improve its visual impact and capacity for hosting state pageantry. As division followed defeat in WWII, the street came to be a symbolic axis of a divided Europe with even its renaming being a marker of the contestation. The current

[44]__Perry, J. (2019). Love Parade 1996: Techno Playworlds and the Neoliberalization of Post-Wall Berlin. German Studies Review, 42(3), pp.561–579.

name, literally translating as the ‘the Street of the 17th June’ was motivated by a Western desire to memorialise the East German victims of an attempted uprising against communist rule on this date in 1953. Thus the selection of this highly politicised landscape for the new location of the Love Parade in 1997 marked a turning point as the event’s drug-charged pleasure-seeking was forced to confront the past violence and volatility of Berlin’s streetscapes. By this point the event consisted of 39 moving techno-sound systems and around a million participants engaging in a mass euphoric experience. As has been argued, organisers utilised the pseudo-political underpinnings of the parade as a counter to the symbols of a problematic statehood present on this location [46] . As Elizabeth Bridges describes in her analysis of the mass event, the Love Parade’s slogans such as: ‘Friede, Freude, Eierkuchen - Peace, Fun and Pancakes’, 'We are One Family’, and ’The Future is Ours’, espoused an amorphous politics of non-affiliation through its vague statements of change made possible by a transcendent, global rave culture [47] .

Despite the questionable politics of the event, the Love Parade maintained an official status as a political demonstration until 2001, largely in a bid by its organisers to avoid the costs of the clear-up and policing that this status exempted it from. [48] A political demonstration by definition speaks of an oppositional gathering acting within the law, yet as mentioned, the Love Parade purposely had little in the way of a clear political message or affiliation. Even more paradoxically, as the event grew bigger it became a magnet for advertising and commercial interests which countered the

[46]__Terkessidis, M. (1998). Life after history. How pop and politics are changing places in the Berlin Republic. Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe, 6(2), pp.173–190.

fig. 3.3

[left]

Strasse des 17. Juni 1996 - Love Parade

fig 3.4 [right]

Commercialisation Parade Advertising - 1999

underground and anti-authoritarian nature of its origins. The irony of a highly commercialised, apolitical mass event being endorsed by the city municipality as a form of political demonstration describes ‘the festivalisation of politics’ undertaken during this time in the pursuit of the image of the ‘new city’ [49] .

In this way, city authorities were willing to overlook the considerable costs that were forced onto them by the parade’s protest status in order to nurture the image of a liberal and youth-orientated city, projected to a global audience by the event. The Love Parade and wider use of the megaevent in Post-Wende Berlin are indicative of the economy of symbols that had come to dominate the redevelopment of the city. Symbols, meaning and cultural attributes could be quickly placed onto urban sites in the city through the medium of festival, the aim being the formation of experiencedriven place identity paired with the attraction of global attention. However what the Love Parade shows within its partnership between city boosters and global brands is the risk of homogeneity such symbols could produce. In its final years, the parade bore no resemblance to the grassroots partyprotest of 1989, instead appearing as the manifestation of the total branding of public space as advertisers and organisers alike attempted to use the once subversive event for profit [fig.3.4]. In a fitting way, the fate of the Love Parade speaks to the victory of neo-liberal forces in controlling the city streets.