11 minute read

What I did on my holidays – 34th FAI World Gliding Championships

from SoaringNZ Issue 48

by mccawmedia

BY KAREN MORGAN

The 34th FAI World Gliding Championships were held in Benalla, Victoria, Australia last month. There were three official practice days from 5 to 7 January and an opening ceremony on 8 January. The competition ran from 9 January to 21 January 2017.

Advertisement

New Zealand sent a full team of pilots and supporters. The Open Class was flown by Brett Hunter and Mark Tingey, both in their 21 metre JS1s which are normally based in Tauranga. John Coutts flew in the 18 metre class in a new, factory supplied, Ventus 3, joined by Tim Bromhead in a rented ASG29. The pilots in the 15 metre class were Steve Wallace in a rented Ventus 2 and Alan Belworthy in Lindsay Stephens’ ASW27, which was shipped from New Zealand for the event. Julian Elder was team captain, and the supporters included the families (wives, children, parents, in-laws, siblings) of the seven listed above and a few non-family crews. These were: Robert Smits (for Tim), Lindsay Stephens (for John) and Terry Jones (for Alan). We also had specialised meteorological support from David Hirst. All up, we made a crowd of over 25 people. All manner of other Kiwis dropped in a for day or so over the period and a few came to take part in the concurrent OSTIV conference.

Most of the team had flown one, two or three competitions in Australia in the past few months. Mark Tingey was the most successful, coming second in the Australian Grand Prix qualifying round at Horsham, Victoria.

Pilots and crew/family arrived over the period after Christmas, with the last arrivals being Brett and Mark who, as they had their own gliders in Australia, needed less ‘fettling’

WHAT I DID ON MY HOLIDAYS

Kiwis at the opening ceremony

Tow pilots scrambling for duty

Photo Gerard

Winners 18m

time. Some of the rented gliders had technical issues that took up a lot of time pre-competition, such as getting the FLARMs working, water ballast issues, tyre issues, cleaning, loading trackers, screens and sundry equipment – all necessary but time consuming.

Terry and I arrived on 2 January, and set up ‘Kiwi Base’ in a house that I had booked a year ago. It was air-conditioned, sizeable and had pool and barbeque area access from the neighbouring motel. The radios were set up here; a large aerial was erected and Julian was based here to track our gliders and keep the team informed of happenings. We held team meetings here each morning, after the official morning briefing, to discuss the weather and how to tackle the tasks and team flying.

As team captain, Julian had to go to lots of meetings, receive the tasks, then the new tasks, the changes to the new tasks and the general advice from the organisation. He took an Australian phone package that included unlimited texts, which was handy as block-texting us all had him receiving a text from the provider checking on his usage as he passed 3,000 texts… in the first week. All the interactions between the organisers and pilots are made through the team captains, as many pilots spoke only limited English and this process probably avoided a great many arguments too.

GNZ organised a series of promotional videos to be made

Tim Bromhead Photo

Tim Bromhead Photo

Alan Belworthy (R) with Neil Dunn from the Kingaroy Gliding Club

in the first week and Craig Walsh, of Kor Creative in Auckland, joined us to make these. After a week, Craig went back to work and David Hirst developed his own videoing skills for the second week. If you did not see them at the time on GNZ’s Facebook page, you can watch them through the GNZ website without having to join Facebook. David Hirst, together with a stuffed Kiwi, starred in the videos which outlined the weather, showed lots of people and gliders, a bit about flying tasks and how the days went, and showcased some good New Zealand music. These videos were shared numerous times and watched by many thousands of people around the world. Whether this leads to increased gliding activity remains to be seen; we will let time decide that. If you want to watch videos with the day winners and various other exalted people, many of these are available on the Australian Facebook page.

The opening was entertaining, trying to get the countries in the correct alphabetical order, but otherwise rather hot. The team uniform of black shirts looked great but we dispersed quite quickly because of the 38 degree heat.

So, to the weather, which was variable between 20 and 42 degrees, wet or dry, windy or not. No snow or hail was experienced but we had one rather good thunderstorm. It was usually warm enough to use the pool. Ice cream was needed. “Blue and low with weak thermals,” was a common comment. Some days were lost to rain and one to mud when the grass runway was too sticky to use.

The flying – lots was done. The biggest task was 747 km for the open class, north to abeam Sydney and back; they also had a 600 km task. You can see the details on Soaring Spot. Most tasks were regular racing tasks (to fixed points) and a few AAT (assigned area tasks) were set, for one class at a time. Long tasks and AATs were used as an attempt to stop pilots from flying in mega-gaggles.

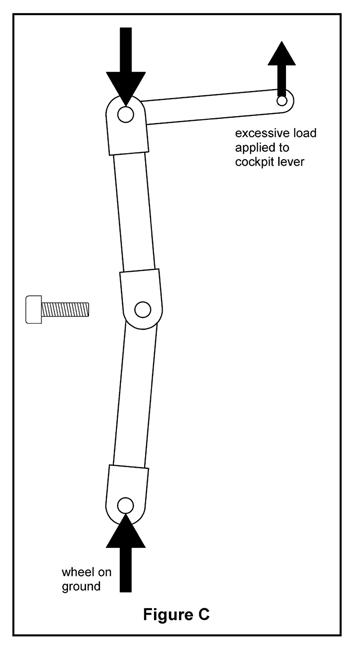

The gaggles were ferocious. The classes were large with 37 in 15m, 43 in 18m and 35 in Open, so up to 115 gliders were flying. The organisers used different drop zones and start points, and spread the tasks as far as possible to avoid the classes meeting. A comment was made that having two or more classes of gliders in a gaggle made it more difficult, as the shorter wing gliders did smaller circles and the mix of circle sizes was tricky to safely accomplish. There were numerous reports of unsafe and aggressive flying, and two mid-air collisions. The first was in the 18m class in a small gaggle, with only six gliders. The touch of wing tips led to no damage, although the pilots

Craig Walsh, of Cor Creative producing one of NZ’s viral videos

followed the rules and landed quickly. No pilot was found to be at fault but it was noted that both were concerned with a primary collision threat which was a third glider between them and therefore overlooked each other.

The second mid-air, in the 15m class, was more serious, with neither glider seeing each other before the impact. One pilot left a thermal and descended on another glider which was skirting (too) close to the thermal. It was a very high speed impact, with the tail broken on one and a wing lost from the other. The gliders were immediately unflyable and both were spinning. Luckily the pilots parachuted out safely however both gliders were destroyed. Lessons on parachutes are noted separately. The organisers did some analysis of tracks flown by all of the pilots in the competition, which showed that the 15m gliders generally flew closer to other gliders than the bigger wings in this event. Lessons were given at morning briefings on how to join a thermal, how to behave in it, how to leave, and general airmanship – including waving at other pilots to confirm that you have seen them. This is all part of the New Zealand syllabus so it was interesting to see it reinforced by the organisers because it appeared ‘the best pilots in the world’ were too keen to win to always display good manners.

Other than these safety messages, much flying was accomplished and much scenery was seen. The social side was pretty successful, especially the International Night. Each country (27 in all) individually or in a group for the smaller teams, provided food or drink from their nations. New Zealand, led by Lisa Wallace and Janet Elder, made individual pavlovas with kiwifruit and passionfruit, and served these with Marlborough sauvignon blanc. The South African team kept it simple, having shipped dozens of wine bottles with their gliders. We enjoyed German sausages, Japanese sake, English steak and kidney pies, Australian lamb, Finnish cinnamon buns, Canadian sockeye salmon, American margaritas, and Russian caviar and European beer. It was great.

The closing ceremony was brief and to the point, as we all had to rush away to catch flights or ship gliders, but there was a nice aerial display by a glider pilot in an Air Force display plane. Great Britain won the team trophy.

The highlights from our team performances were: ›› Steve’s 5th on the last day and his ability to complete all the tasks with no landouts for the whole competition ›› Brett’s consistency, and ability to finish tasks, again with no landouts

Tim Bromhead Photo

15m winners

›› Mark flew further than he ever had before (over 600km) and then did it again the next day ›› John had a couple of very good results with two 4th places, flying an unfamiliar glider ›› Tim showed tenacity, but had a couple of landouts, one sadly at the furthest distance from Benalla on the last day ›› Alan flew consistently and professionally and recovered well from witnessing the bailouts.

It has been really interesting to be part of the New Zealand team for this event and great to watch our pilots developing. While the results might not be all that the pilots anticipated, they have all displayed good airmanship and their flying skills have been practised and enhanced.

Close study of the results show the benefits of team flying, which is not allowed in our competitions and therefore not practised by us or most of the smaller countries. There is also a lot of debate about the tasks and scoring system, which was seen to reward gaggle flying and punish independent flying on the many blue days.

The team would like to thank all their families, crews, supporters, sponsors, employers and the GNZ Umbrella Trust.

The winners and our team results were: OPEN CLASS 1 Russell Cheetham GBR 2 Michael Sommer GER 3 Andrew Davis GBR 20 B rett Hunter N ZL 30 Mark Tingey NZL 18M CLASS 1 Killian Walbrou FRA 2 Mario Kiessling GER 3 Mike Young GBR 33 John Coutts NZL 34 Tim Bromhead NZL 15M CLASS 1 Sebastian Kawa POL 2 Makoto Ichikawa JPN 3 Lukasz Grabowski POL 18 Steve Wallace NZL 29 Alan Belworthy NZL

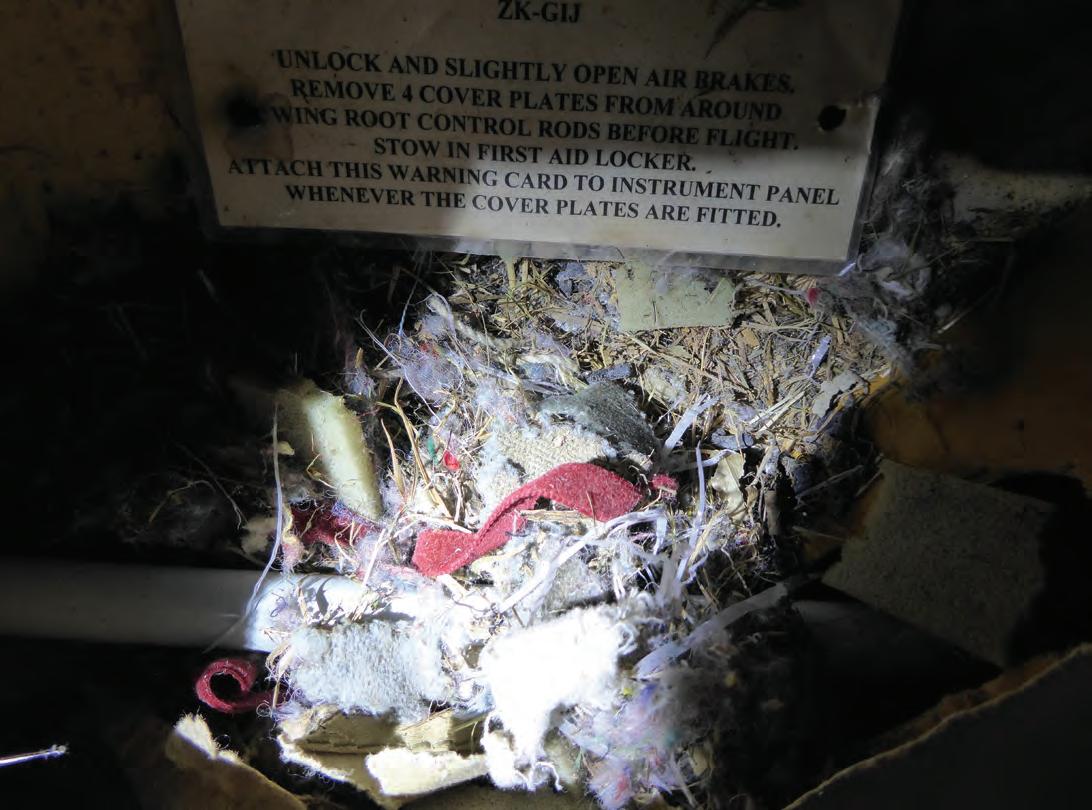

PRACTICAL PARACHUTING At morning briefing on Thursday 19 January, Steve O’Donnell of Australia spoke about the 15m mid-air incident and more specifically about his efforts to survive. He raised several key points about parachutes. 1. Size of the canopy. Do you know how big yours is? Steve said, “I’m 95 kilos, and when I looked up, it looked like a beach umbrella.” Make sure that the canopy is big enough to work safely for you (and for others who fly the glider). 2. Q uick release. The most painful injuries Steve sustained were from being dragged along the ground in the estimated 20 knot winds. Although knowing how to collapse the parachute would be good, having a quick release system is important. See your parachute rigger to discuss putting a quick release system in place. 3. E xiting the glider. Steve said it took from 5,000 feet to 1,700 feet to actually get out of the spinning glider. He was quick to release the canopy and straps but it was a real struggle to actually get out of the glider. It was not possible for him to exit using the usual method of levering himself out using his arms as is done on the ground. He had to put a leg out first to get that caught in the wind which pulled his body out of the cockpit to under the wing, (tearing his ligaments and hamstrings). Have a plan, and have a practice too.

SOME OTHER CONSIDERATIONS: Some gliding clubs have particularly good parachute training, including learning to land safely, to minimise broken legs and back injuries. Your local skydive school can help with this training too.

Make sure the harness fits pilots well. It is not one size fits all; a big harness is not safe for a small pilot. Clubs need to have a range to cover their club members. Do the straps up firmly.

Store the parachute in dry conditions, somewhere like your hot water cupboard, rather than leaving them in gliders, hangars or cars.

Lastly, don’t overlook the requirement to get the parachutes inspected and repacked annually at the start of the soaring season (although six monthly would be better). If they get damp, have them opened, dried and repacked before using them again.