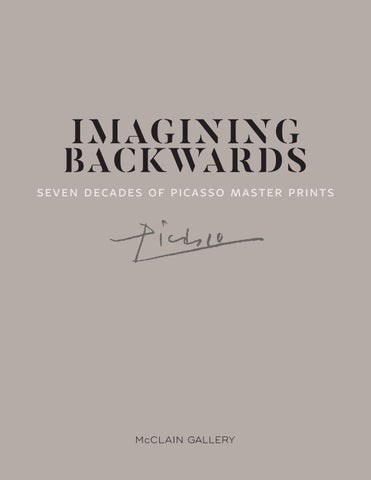

IMAGINING BACKWARDS seven decades of picasso master prints

Imaging Backwards: Seven Decades of Picasso Master Prints

Issuu converts static files into: digital portfolios, online yearbooks, online catalogs, digital photo albums and more. Sign up and create your flipbook.