2023-24 EDITION SPECIAL EDITION 80 Years of U.S. Special Operations

Schedule Contract GS-07F-5916R ® www.blueskymast.com We build the world’s most advanced multi-purpose, portable mast platforms for military communications and surveillance. Tested. Proven. Made in the U.S.A.

ONE MAST. INFINITE CONFIGURATIONS.

SPEED

Designed to enable warfighters to quickly and easily deploy the mast in any environment.

PORTABILITY

Patented tripod based, sectional mast designed to be independent of vehicles and shelters.

VERSATILITY

Patented tool-less accessories reduce set up time and help simplify field deployments.

DEPENDABILITY

Precision engineered components to achieve maximum performance and durability.

www.icsg.us.com 703.294.5800 info@icsg.us.com Integrated Communications Systems Group Cyber Security | Management Consulting Cloud Computing | IT and Engineering PARTNER OF 877-DONYA90 www.donyaconsultinggroup.com

4 RANGERS IN WORLD WAR II By Mike Markowitz 14 THE OFFICE OF STRATEGIC SERVICES Donovan’s Glorious Amateurs By Charles Pinck 18 OPERATION RAINCOAT The First Special Service Force at La Difensa By Dwight Jon Zimmerman 28 ICONIC WEAPONS The Thompson SMG By Chuck Oldham 30 CARPETBAGGERS Air Arm of the OSS in Europe By Dwight Jon Zimmerman 38 THE MAKIN RAID By Dwight Jon Zimmerman 46 SILENCE, STEALTH, BOLDNESS, AND BRAVERY U.S. Navy Special Operations in World War II By Chuck Oldham CONTENTS spyderco.com 800 525 7770 EDITORIAL Editor in Chief: Chuck Oldham Senior Editor: Rhonda Carpenter Contributing Writers: Mike Markowitz, Chuck Oldham Charles Pinck, Dwight Jon Zimmerman DESIGN AND PRODUCTION Art Director: Robin K. McDowall FAIRCOUNT MEDIA GROUP Publisher and Chief Executive Officer: Robin Jobson Published by Faircount Media Group www.defensemedianetwork.com • www.faircount.com ©Copyright Faircount, LLC. All rights reserved. Editorial contents copyright The Black Angel Company, LLC. Reproduction of editorial content in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Faircount LLC does not assume responsibility for the advertisements, nor any representation made therein, nor the quality or deliverability of the products themselves. Reproduction of articles and photographs, in whole or in part, contained herein is prohibited without expressed written consent of the publisher and The Black Angel Company, with the exception of reprinting for news media use. Printed in the United States of America.

exercise in August 1942. NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Cover photo: Ranger Battalion soldiers training with British Commandos on an “opposed landing,”

RANGERS IN WORLD WAR II

BY MIKE MARKOWITZ

yIn the decades after the Civil War, the U.S. Army saw little need for specialist Rangers. “Small wars” were

left to the U.S. Marine Corps, while the Army prepared to fight the next “big war.” U.S. Army doctrine was largely

shaped by French influence. The next war would be won by the marksmanship of riflemen, the firepower of massed artillery, and the mobility of horse cavalry. There simply was no interest within the U.S. military for unconventional warfare from 1865 until the start of World War II. However, World War II would provide a fertile venue for unconventional soldiers with their own ways of fighting, especially the Rangers, who had performed exceptionally well in their first battles.

As Allied forces advanced from Algeria eastward into Tunisia, the Axis poured in reinforcements to protect Erwin

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

4 Special Operations Outlook

Rommel’s precarious supply line. The Rangers were pressed into frontline service, attached to the U.S. Army’s 1st Infantry Division (nicknamed “The Big Red One”). Using special operations forces as infantry is contrary to sound military doctrine, but for commanders there are never enough riflemen, and combat is always an emergency. In February 1943, inexperienced and poorly led American troops had been badly mauled in their first engagement against German panzer troops at Kasserine Pass, and the Rangers had been called upon to help hold the line. Early in March, Maj. Gen. George S. Patton took command of the American forces in Tunisia.

On March 18, 1943, Maj. William O. Darby’s 1st Ranger Battalion occupied the desert oasis of El Guettar. A few days later, they scaled a cliff to raid a dug-in enemy position, taking hundreds of demoralized Italians prisoner. In the early hours of March 23, the

veteran German 10th Panzer Division attacked with 50 tanks and two battalions of infantry in halftracks. In several days of bitter fighting, the Rangers held the heights, while some of their element joined U.S. Army infantry units on the plain below and helped to turn back the German attack.

After the success of the 1st Ranger Battalion, Army leadership became more convinced of the usefulness of special operations forces. Elements of the 1st were split off to form the cores of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Battalions. The 4th Ranger Battalion was activated May 29, 1943, in Tunisia, and the 3rd Ranger Battalion on June 19, 1943, in Morocco. Their training was tough and often dangerous, with 1st Battalion Rangers training the 3rd and 4th Battalions as they themselves had been trained. In the United States, the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions were formed at Camp Forrest, Tennessee, activated in September 1943, and soon after shipped to England.

ITALY

In Sicily and Italy, three Ranger battalions fought until the Anzio landings in January 1944 on the Italian coast south of Rome.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES 5

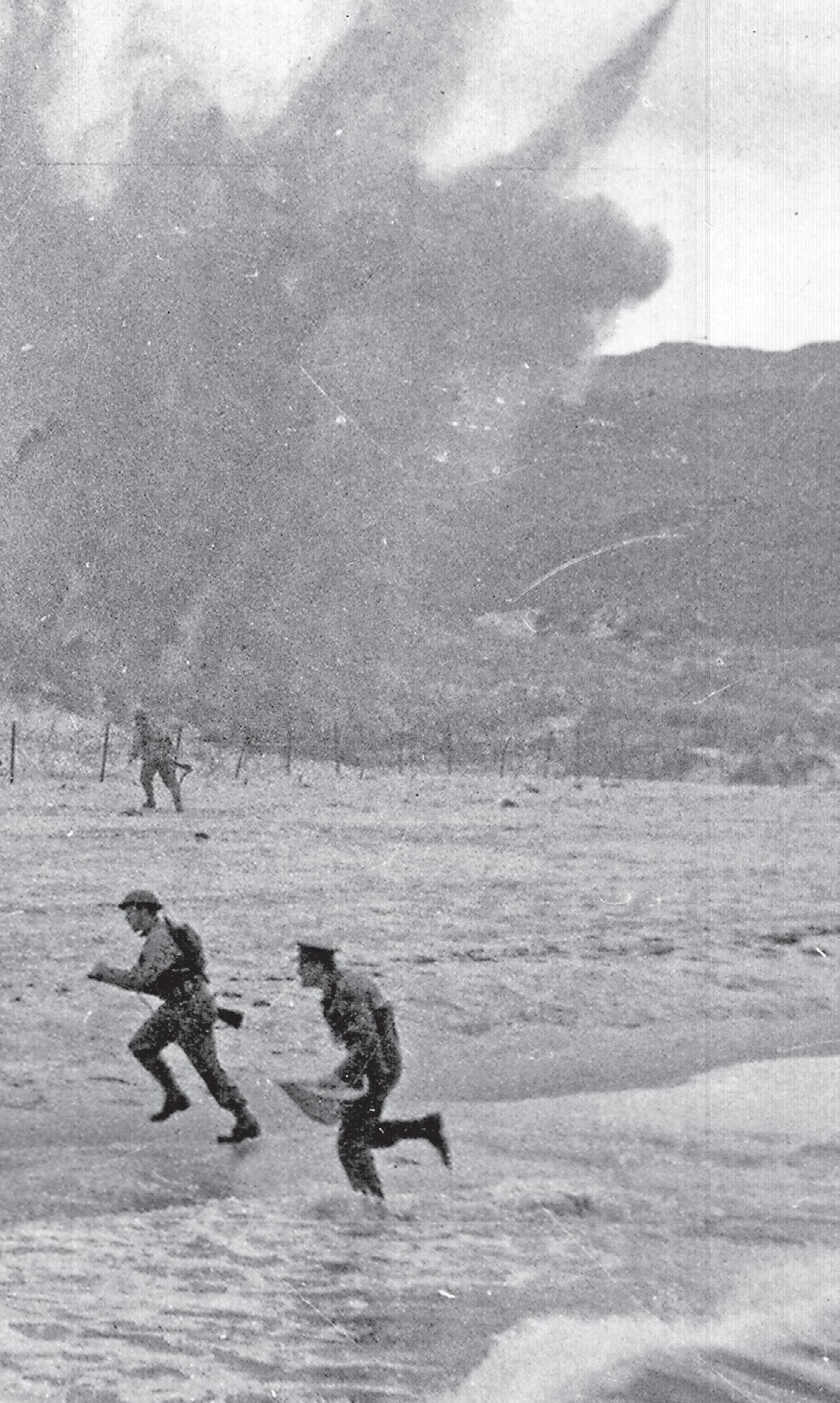

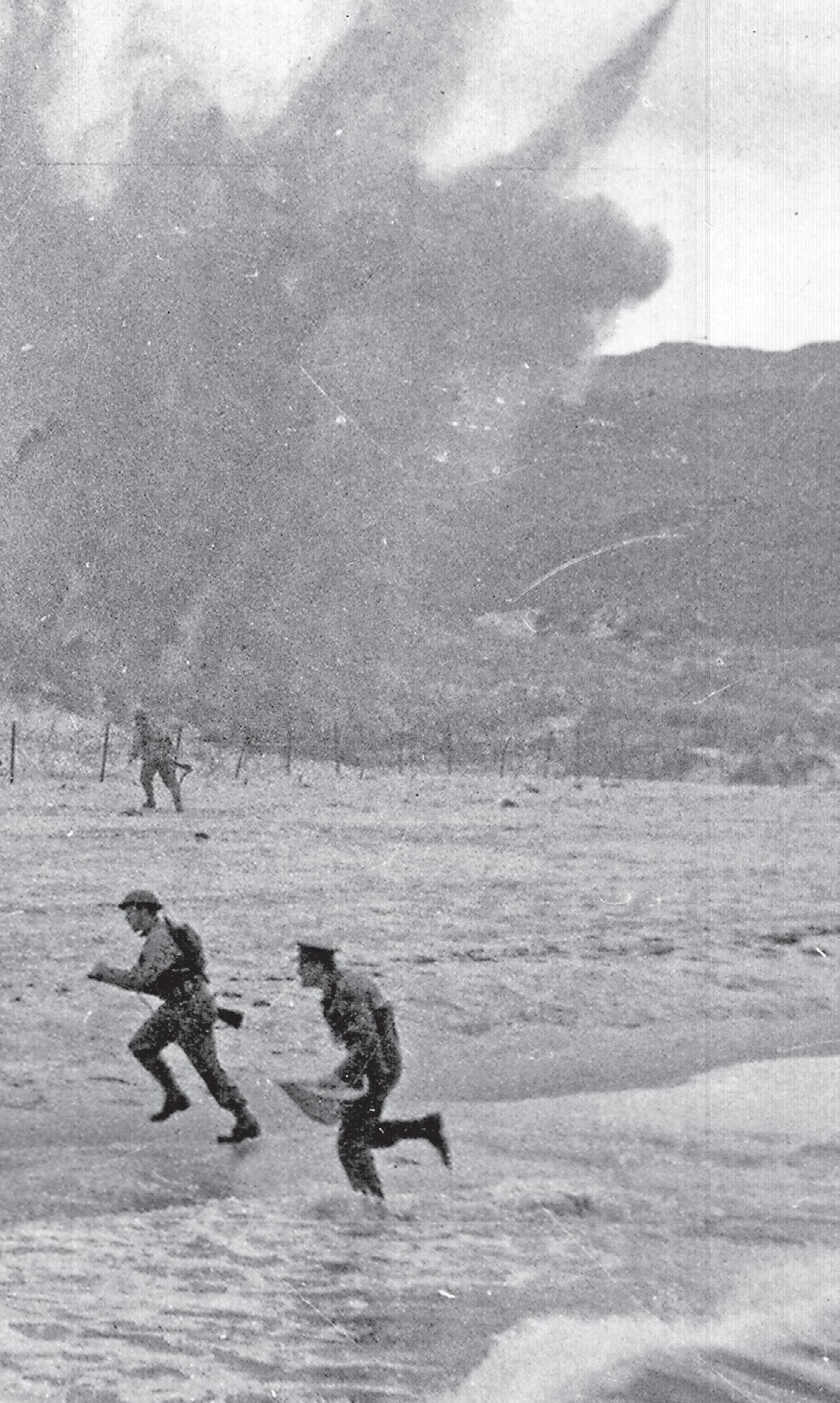

Left: Ranger Battalion troops under “enemy” fire as they attack beach defenses while training with British Commandos, August 1942. Right: Ranger Battalion troops training on an “opposed landing” exercise in which live ammunition and hand grenades were used to simulate actual war conditions, August 1942.

RANGERS IN WWII

6 Special Operations Outlook

NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Above left: Rangers training on the hills around Arzew, Algeria. Their first major action was to successfully capture two coastal artillery batteries at Arzew during Operation Torch. Left: The Rangers remained in Arzew for two months, training hard but also running the town. 1st Ranger Battalion Commander Maj. William O. Darby was the town “mayor,” and used a motorcycle as his usual transportation around the battalion when the Rangers were not in combat. Above: Soldiers of the 3rd Ranger Battalion board LCUs that will deliver them to Sicily.

The 1st and 4th Ranger Battalions hit the beach at Gela in Sicily, captured the town and coastal artillery batteries, and then held during two days of counterattacks. The 3rd Ranger Battalion captured Porto Empedocle, and took more than 700 prisoners. As Allied forces drove toward Palermo and Messina, the three Ranger battalions protected the flanks of the advancing forces.

On Sept. 9, 1943, Rangers hit the beach at Salerno, and quickly took the high ground on the Sorrentino peninsula. But they were forced once again to hold objectives taken early in their amphibious assault, in this case for almost three weeks. Much too lightly armed for such a defense, and too few in number to hold a continuous line, the Rangers were forced to adopt a series of mutually supporting strongpoints, depending on naval gunfire, as they had at Gela, to hold off a series of fierce German counterattacks. Elements of Gen. Mark W. Clark’s Fifth Army finally broke through to the beleaguered Rangers on Sept. 30.

By November 1943, Clark was stuck, his forces facing the Germans across the “Winter Line,” actually a series of three lines of entrenchments and fortifications taking advantage of the ideal defensive terrain of Italy’s mountains. Here, Clark threw the Rangers into the fight once again, attaching the battalions to existing divisions in the hope of making a breakthrough. Instead,

the Rangers suffered heavy casualties in bitter fighting between November and December.

The solution the Allies came up with to get past the Germans’ Winter Line was an amphibious assault on Anzio, which lay north of the German defensive lines and south of the ultimate goal of Rome.

The landing was virtually unopposed, but Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, commander of VI Corps, failed to aggressively move inland, and the Germans soon contained the beachhead. Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, 3rd Infantry Division commander, hoped to drive a wedge in the German lines by having the 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions infiltrate 4 miles through the lines to the town of Cisterna. The plan was for the Rangers to take the town in a surprise attack, following which the 3rd Division, along with the 4th Ranger Battalion, would launch a frontal assault to link up with the Rangers in Cisterna. On the night of Jan. 31, 1944, the Rangers jumped off. Unknown to them, while Allied intelligence believed the main German line was behind Cisterna, in fact the town was an assembly point for German reinforcements. Instead of light forces, the Rangers were met short of the town by elements of the 715th Infantry Division and the Herman Goering Panzer Division, including at least 17 tanks. After a seven-hour battle, what was left of the two battalions finally surrendered to the Germans.

7 RANGERS IN WWII

U.S. ARMY PHOTO

Only six Rangers of the 767 who had begun the mission made it back to Allied lines.

Historians argue over whether the disaster was simply the result of faulty intelligence, or whether the presence of many inexperienced replacements in the ranks of Ranger units who had been kept in frontline combat for too long also contributed to the disaster. The surrender at Cisterna was the darkest day in Ranger history. The remnants of the three battalions were rotated home or became part of the 1st Special Service Force, providing a pool of combathardened veterans to the elite outfit.

NORMANDY

The Normandy invasion (Operation Overlord on June 6, 1944) was the most carefully planned assault in history. Planners were particularly concerned about a cliff-top German artillery battery

at Pointe du Hoc, where six 155 mm guns in concrete revetments were positioned to pour devastating fire onto two of the invasion beaches. The point was pounded from the air by heavy and medium bombers, leaving a cratered landscape, but reconnaissance could not confirm that the guns were knocked out. The 2nd Ranger Battalion drew the assignment of making sure that the guns were spiked.

Dog, Easy, and Fox companies of the 2nd Ranger Battalion were to scale Pointe du Hoc. On June 6, 1984, the 40th anniversary of Operation Overlord, President Ronald Reagan spoke at the site, retelling the epic story:

“The Rangers looked up and saw the enemy soldiers at the edge of the cliffs, shooting down at them with machine guns and throwing grenades. And the American Rangers began to climb. They shot rope ladders over the face of these cliffs and began to pull themselves up. When one Ranger fell, another would take his place. When one rope was cut, a Ranger would grab another and begin his climb again. They climbed, shot back, and held their footing. Soon, one by one, the Rangers pulled themselves over the top, and in seizing the firm land at the top of these cliffs, they began to seize back the continent of Europe. Two hundred and twenty-five came here. After two days of fighting, only 90 could still bear arms.

8 Special Operations Outlook RANGERS IN WWII

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Above: U.S. Army Rangers rest atop the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc, which they stormed in support of Omaha Beach landings on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

“Behind me is a memorial that symbolizes the Ranger daggers that were thrust into the top of these cliffs. And before me are the men who put them there.

“These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped end a war.”

In fact, the German guns had been pulled back inland and hidden under camouflage netting, where they were soon found by the Rangers and destroyed. In addition to their actions at Pointe du Hoc, Rangers were key in getting U.S. forces off of the killing ground of Omaha Beach. Able, Baker, and Charlie Companies of the 2nd Ranger Battalion and the entire 5th Ranger Battalion landed on Omaha Beach, along with the 1st Infantry Division and the 116th Infantry of the 29th Division. On Omaha Beach, surviving soldiers were pinned down on the shingle under machine gun, artillery, and mortar fire. It was on the eastern end of Omaha, where 29th Division soldiers were fighting for their lives, that the Rangers earned their motto. Here, Brig. Gen. Norman Cota, second in command of the 29th Division, called out, “Rangers, lead the way!” as he organized an attack. Rangers led the way off the beach and found the way inland. Rangers later fought at Brest, the Huertgen Forest, and the Battle of the Bulge. Sadly, William O. Darby did not live to see final victory. On April 30, 1945, just a week before the Nazi surrender, he was killed in action by an enemy shell while leading the pursuit of retreating German forces in northern Italy. He was 34 years old. But the European theater was hardly the only place in World War II where Rangers served.

9 RANGERS IN WWII NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Above: U.S. Army Rangers in a landing craft, prior to leaving England for the invasion of France, early June 1944. Left: Rangers in Rurberg, Germany, March 3, 1945, prepare for a patrol.

MERRILL’S MARAUDERS

Early in the Pacific War, the Japanese invaded Burma, driving the British back into India and cutting the Burma Road, a tenuous supply line that kept China – just barely – in the war. The rugged mountains and thick jungle of northern Burma were exceptionally difficult terrain for conventional warfare.

Late in 1943, a secret Ranger unit was formed and began training in India for operations against the Japanese in Burma. The regiment-sized “5307th Composite Unit (Provisional)” was soon nicknamed Merrill’s Marauders, after its commander, Maj. Gen. Frank Merrill (19031955). A 1929 West Point graduate, Merrill earned an engineering degree from MIT and learned Japanese, serving as a military attaché in Tokyo and later as an intelligence officer.

In February 1944, 2,750 Marauders, in three battalions, arrived in Burma and began an epic five-month, 1,000-mile trek behind Japanese lines. The unit included a transport company equipped with mules.

The Marauders, usually outnumbered, always inflicted many more casualties than they suffered as they harassed Japanese lines of supply and communication and raided their rear areas.

In August 1944, on their final mission against Myitkyina, the only all-weather airfield in the region, the Marauders suffered 272 killed, 955 wounded, and 980 evacuated for sickness. Merrill refused evacuation after a heart attack before falling ill with malaria. By the time Myitkyina was secured, fewer than 200 Marauders were left out of the original 2,750 who had marched into Burma six months before.

CABANATUAN RESCUE

As the war in the Pacific drew to a close, U.S. officials began receiving reports that the Japanese were massacring Allied prisoners of war (POWs) whenever Allied invasions were pending. On Dec. 14, 1944, at Puerto Princesa on the island of Palawan, the Japanese herded 139 prisoners into trenches, poured gasoline over them, and burned them alive. Eleven survivors managed to escape.

Intelligence sources reported that more than 500 starving POWs, including

10 Special Operations Outlook RANGERS IN WWII NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Top: Merrill’s Marauders rest during a break along a jungle trail near Nhpum Ga. Above: The first American troops to enter Burma were Merrill’s Marauders. This picture was taken as they crossed from Assam, India, into Burma at Borderville, or Paqusace Pass.

survivors of the Bataan death march, were facing death at a prison camp near Cabanatuan on the Philippine island of Luzon.

On Jan. 28, 1945, 121 picked troops of the 6th Ranger Battalion, led by Lt. Col. Henry Mucci, infiltrated 30 miles behind Japanese lines guided by about 80 Philippine guerrillas and Alamo Scouts. The most dangerous phase of the attack would be the final phase of the approach. The Japanese had cleared the land around the camp, and the Rangers would have to low crawl over a flat field during the only hour of full darkness before the moon rose.

An Army P-61 Black Widow night fighter repeatedly buzzed the camp at very low altitude in order to distract the Japanese guards during the Rangers’ critical final approach over the open ground. The distraction succeeded beyond all expectations, and the Rangers surrounded the camp without being detected. The Rangers lost two killed and four wounded in taking the camp and defeating strong counterattacks. Japanese losses are uncertain;

one estimate is 530 killed. Predictably, no Japanese prisoners were taken. It was that kind of war.

Most of the 512 liberated prisoners (489 POWs and 33 civilians) were too sick and weak to march, so the Rangers hired dozens of native carts pulled by carabao (water buffalo) from local farmers. Hostile and suspicious communist guerrillas tried to interfere with the rescue, but Mucci, using diplomacy, bluff, and threats, managed to negotiate safe passage back to friendly lines. It was, at the time, the largest hostage rescue operation in history.

“No incident of the campaign in the Philippines has given me such satisfaction as the release of the POWs at Cabanatuan,” said Gen. Douglas MacArthur. “The mission was brilliantly successful.” Mucci was promoted to colonel and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

The site of the raid, on land donated by the Philippine government, is today a memorial to the 2,656 Americans who died in the camp, maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Despite their record of success, the Rangers suffered the same fate as much of the U.S. military following World War II. Faced with radical postwar downsizing, the Army was not keen to keep its Ranger units because they had suffered such high casualty rates, losing excellent soldiers that generals would have preferred to keep as small-unit leaders for regular units. The Army continued training individual soldiers at the Ranger School, established in 1950 at Fort Benning, Georgia, who then returned to their original units to provide leadership and subject-matter expertise.

11 NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Above: Men of C and E Companies, 6th Ranger Battalion, are shown advancing toward the Japanese prisoner of war camp at Cabanatuan, Luzon, the Philippines. Left: In column formations, U.S. Rangers cross a shallow stream as they escort released prisoners of war from the Cabanatuan prison camp on Luzon, Philippine Islands, to an American evacuation hospital, January 1945.

THE FUTURE OF COMBAT DIVER PROPULSION

BY CHARLES L. FUQUA, PATRIOT3, CEO

BY CHARLES L. FUQUA, PATRIOT3, CEO

Patriot3 announces the release of the world’s first fully modular, submersible propulsion vehicle for global maritime special operations.

Patriot3 introduces the fully autonomous Hammerhead subsurface multi-mission vehicle (SMV). The Hammerhead SMV was designed as a next-generation, autonomous-operating propulsion vehicle providing for infinite additions and upgrades for use in manned and unmanned operations. The Hammerhead SMV’s patented modular design allows for rapid exchange of modules for maintenance, replacement, or expandability. This modularity also allows for the addition of standard and specialized modules for mission-specific configurations. For instance, battery modules can be added to provide extended range, longer operation under high speeds, and to provide excess power for ancillary equipment such as heated diver suits, specialized electronics, etc. Modularity also allows the Hammerhead SMV to be upgraded as new technologies for navigation, power and propulsion are available. With its modularity and autonomous operation, the Hammerhead provides a single platform for both manned and unmanned missions by using similar features, service, and parts.

The Hammerhead SMV navigates through its environment via customized integration with the Shark Marine Dive Log navigation system. This navigation system provides for auto-depth control using the most advanced DNS, obstacle avoidance through forward-looking sonar, diver-to-vehicle communications, and GPS/ satellite positioning. The Hammerhead SMV can integrate with the Shark Marine Navigator, Tablet 2, or E-Tach for its navigation and autonomous operation. The navigation system can also be removed from the Hammerhead SMV for use outside the vehicle.

The Hammerhead SMV provides the most thrust of any DPV on the market. Through its four powerful direct-magnetic motors, the Hammerhead SMV can deliver a peak thrust of 400 pounds. This superb thrust allows the Hammerhead SMV to navigate heavy currents or deliver heavy loads. The Hammerhead SMV’s servodriven, forward bow-plane thrusters (BPT) provide for constant, automated depth control with no diver input. The BPTs also allows the Hammerhead SMV to station-keep without the need to loiter to maintain its depth. The rear thrusters provide additional thrust, thrust redundancy, and the ability to station-keep on target. When station-keeping is requested, the BPTs rotate vertically to control the depth while the rear thrusters steer the vehicle. The Hammerhead SMV uses differential thrust for superb and precise maneuverability.

Expandable power, customizable configuration through modularity, and redundant thrust makes the Hammerhead SMV the manned or unmanned delivery vehicle of choice for decades to come. The Hammerhead SMV has U.S. and international patents and patents pending.

For more information on the Hammerhead SMV or to inquire about a demonstration, please contact Patriot3 at info@patriot3.com or visit www.patriot3.com.

SUB-SURFACE MULTI-MISSION VEHICLE

THE OFFICE OF STRATEGIC SERVICES

DONOVAN’S GLORIOUS AMATEURS

BY CHARLES PINCK

yOn June 13, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a military order establishing the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the World War II predecessor to the CIA, the U.S. Special Operations Command, and the Department of State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR). The brevity of this 224-word executive order would reflect the outsized influence that OSS, which had only 13,000 personnel at its peak, would have on U.S. national security during and after World War II. He appointed the legendary William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, a World War I Medal of Honor recipient, as its director.

Donovan was the perfect choice for America’s first intelligence chief. Allen Dulles, who served under Donovan in OSS, said that “Donovan knew the world, having traveled widely. He understood people. He had a flair for the unusual and for the dangerous, tempered with judgment. In short, he had the qualities to be desired in an intelligence officer.” Roosevelt described Donovan as his “secret legs.”

No one other than Roosevelt and Donovan wanted the OSS. Not the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Not the State Department. Most certainly not its greatest foe: FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. The reason for this fierce opposition was best expressed by William Casey, who served in the OSS and would become director of Central Intelligence under President Ronald Reagan: “You didn’t wait six months for a feasibility study to prove that an idea could work. You gambled that it might work … you took the initiative and the responsibility. You went around end, you went over somebody’s head if you had to. But you acted. That’s what drove the regular military and the State Department chairwarmers crazy about the OSS.”

Despite vicious political opposition – Donovan said that he had greater enemies in Washington than Hitler had in Europe – Roosevelt created the OSS because he understood that the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor exposed one of America’s greatest national security vulnerabilities: its lack of an effective intelligence-gathering and unconventional warfare capability.

Donovan’s courageous spirit infused the OSS. He said he would “rather have a young lieutenant with enough guts to

disobey a direct order than a colonel too regimented to think and act for himself.” He frequently told OSS personnel that they “could not succeed without taking chances” or engaging in “calculated recklessness.” Donovan led from the front, going behind enemy lines and participating in major invasions – including D-Day – against the orders of Navy Secretary James Forrestal.

But you needed more than guts to be in the OSS. You needed brains, too. An ideal OSS candidate was described as a “Ph.D. who could handle himself in a barfight.” OSS recruited its

U.S. ARMY PHOTO 14 Special Operations Outlook

OSS

Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan, founder of the OSS, shown during World War II.

personnel from all segments of American society. Its members were drawn from Wall Street, academia, journalism, the arts, high society (earning OSS the sobriquet “Oh So Social”), the military – even prison. Donovan arranged for two of the world’s greatest forgers to be released from prison so they could work for OSS. Women comprised one-third of its work force.

Donovan called them his “glorious amateurs” and described the OSS as an “unusual experiment.”

He was a visionary leader. Fisher Howe, who served as an assistant to Donovan, said that “if you define leadership as having a vision for an organization, and the ability to attract, motivate and guide followers to fulfill that vision, you have Bill Donovan in spades.” So powerful were his

leadership skills that an OSS captain said that “he talked to me for half an hour and I walked out of his office convinced that I could do the impossible.”

OSS personnel were often asked to do the impossible, volunteering for the war’s most hazardous missions behind enemy

U.S. ARMY PHOTO NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO CIA IMAGE, ARTWORK DONATED BY RICHARD J. GUGGENHIME 15 OSS

Top: Jedburghs undergo physical training outside Milton Hall, England, a country estate north of London. Left: Les Marguerites Fleuriront ce Soir, a painting by Jeffrey W. Bass, depicts Virginia Hall as an SOE agent. After fleeing France one step ahead of the Germans, Hall joined the OSS and returned to the occupied country as an agent. Right: An OSS demolitions class underway in Milton Hall, 1944.

The National Museum of Intelligence and Special Operations will honor Americans who have served and fallen at the “tip of the spear.” It will educate the public

vation of freedom. It will inspire future generations to serve their country. Its groundbreaking exhibits will offer visitors an unparalleled experience. It wil l be built in Northern Virginia close to Dulles International Airport in the Dulles Technology Corridor. The museum’s award-winning design was inspired by the spearhead, a symbol associated with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II and used today by its successor organizations. The spearhead points the way forward.

a b o u t t h e i m p o r t a n c e o f s t r a t e g i c i n t e l l i g e n c e a n d s p e c i a l o p e r a t i o n s t o t h e p r e s e

nmiso.org SOCIETY ®

r

lines despite knowing that their capture meant torture and certain death. In a speech to OSS personnel a few days before its dissolution on Oct. 1, 1945, OSS Deputy Director Edward Buxton said that, “thousands of devoted people took the uneven odds. People of all ages lived or died as duty demanded or circumstances permitted. They killed or were killed alone or in groups, in jungles, in cities, by air or sea. They organized resistance where there was no resistance. They helped it grow where it was weak. They assaulted the enemy’s mind as well as its body. They helped confuse its will and disrupt its plans.”

The legacy of the OSS endures today. The OSS Society is planning to build the

National Museum of Intelligence and Special Operations to honor Americans who have served at the “tip of the spear” –the symbol chosen by Donovan for the OSS that is used today by the CIA and U.S Special Operations Command to acknowledge their shared OSS roots.

The museum will educate the American public about the importance of strategic intelligence and special operations to the preservation of freedom. We hope it will inspire future generations to serve. The spearhead points the way forward.

Charles Pinck is president of The OSS Society.

17 OSS

Clockwise from top left: OSS founder Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan with members of the OSS Operational Groups, forerunners of today’s U.S. special operations forces, at the Congressional Country Club in Besthesda, Maryland, which served as an OSS training facility. Photo courtesy of OSS Society; An OSS agent suited up and prepared to be dropped into occupied Europe. National Archives photo; The OSS also operated extensively in the Pacific theater. OSS Deer Team in 1945. Pictured are Lt. Réne Défourneaux (standing, second from left), Viet Minh leader Ho Chi Minh (standing, third from left), team leader Maj. Allison Thomas (center), Vo Nguyen Giap (in suit), Henry Prunier, and Paul Hoagland, far right. Kneeling at left are Lawrence Vogt and Aaron Squires. U.S. Army Center of Military History via Wikimedia Commons; Aaron Bank, an OSS Operational Group leader who went on to become a founder of U.S. Army Special Forces. National Archives photo.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO 18 Special Operations Outlook

Five men of a machine gun squad from the 2nd Regiment, First Special Service Force (FSSF), prepare their “10-in-1” ration supper in the extreme cold of the Apennine Mountains near Radicosa, Italy. The men’s fur-lined parkas were among the unique items of gear the unit used.

OPERATION RAINCOAT

THE FIRST SPECIAL SERVICE FORCE AT LA DIFENSA

BY DWIGHT JON ZIMMERMAN

yBritish Prime Minister Winston Churchill called it “the soft underbelly of Europe.” War correspondent Ernie Pyle called it that “tough old gut.” “It” was Italy. The twoyear Italian campaign of World War II was heartbreakingly brutal. Fighting in rugged terrain that gave all advantage to the German defenders, Allied gains were too often measured in yards and high casualty rates – at one point the price paid was an average of one casualty for every two yards. In November 1943, the Allied advance had stalled at the formidable Winter Line, located about 70 miles south of Rome. These fortifications that stretched from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic Coast included the main Gustav Line, supported by the Bernhardt and Hitler lines. American 5th Army Commander Lt. Gen. Mark Clark was determined to breach the German defenses and reach the Liri Valley, the “gateway to Rome,” before the onset of winter. He code-named his plan Operation Raincoat; as it turned out, an appropriate name, because it rained for days before and during the attack.

Strategically, Clark recognized that Italian topography granted him few options. He later wrote, “There was only one sector on which we could move in strength; that was on either side of Mount Camino, beyond which lay the Liri River Valley leading to the Italian capital. To reach the Liri Valley, we first had to drive the Germans off the Camino hill mass, which included Mount Lungo, Mount la Difensa, Mount la Remetanea, Mount Maggiore, and a little town called San Pietro Infine. … We had little choice but to blast our way through the narrow Mignano Gap adjacent to Mount Camino, and [German theater commander Field Marshal Albert] Kesselring knew it despite our feints along the coast and elsewhere.”

Operation Raincoat’s success depended on the early conquest of the German fortifications on Hill 960, Monte la Difensa. The mission to capture la Difensa went to a recently arrived unit as tough as the Italian terrain. The unit was originally assigned to conduct large-scale guerrilla operations in occupied Norway. Following the cancellation of that, it participated in what proved to be bloodless landings on the Aleutian Island of Kiska that had been held, and then abandoned, by the Japanese. Now, and for the first time, the unit with the misleading name of the First Special Service Force (FSSF) was going to see combat.

U.S. ARMY PHOTO BY SGT. KACIE BENAK

19

FIRST SPECIAL SERVICE FORCE

Even among the special operations units formed in World War II, the FSSF was unique. A bi-national Canadian-American unit, its leader, Col. Robert T. Frederick (West Point, 1928), who had given the unit its innocuous name in order to disguise its purpose, requested that volunteers be “single men between ages of 21 and 35 who had completed three years or more grammar school within the occupational range of Lumberjacks, Forest Rangers, Hunters, North Woodsmen, Game Wardens, Prospectors, and Explorers.”

Frederick was also willing – even eager – to accept troublemakers from other units. It became a perverse point of pride for some “Forcemen,” as they called themselves, to state, “I got into the Force without a criminal record!”

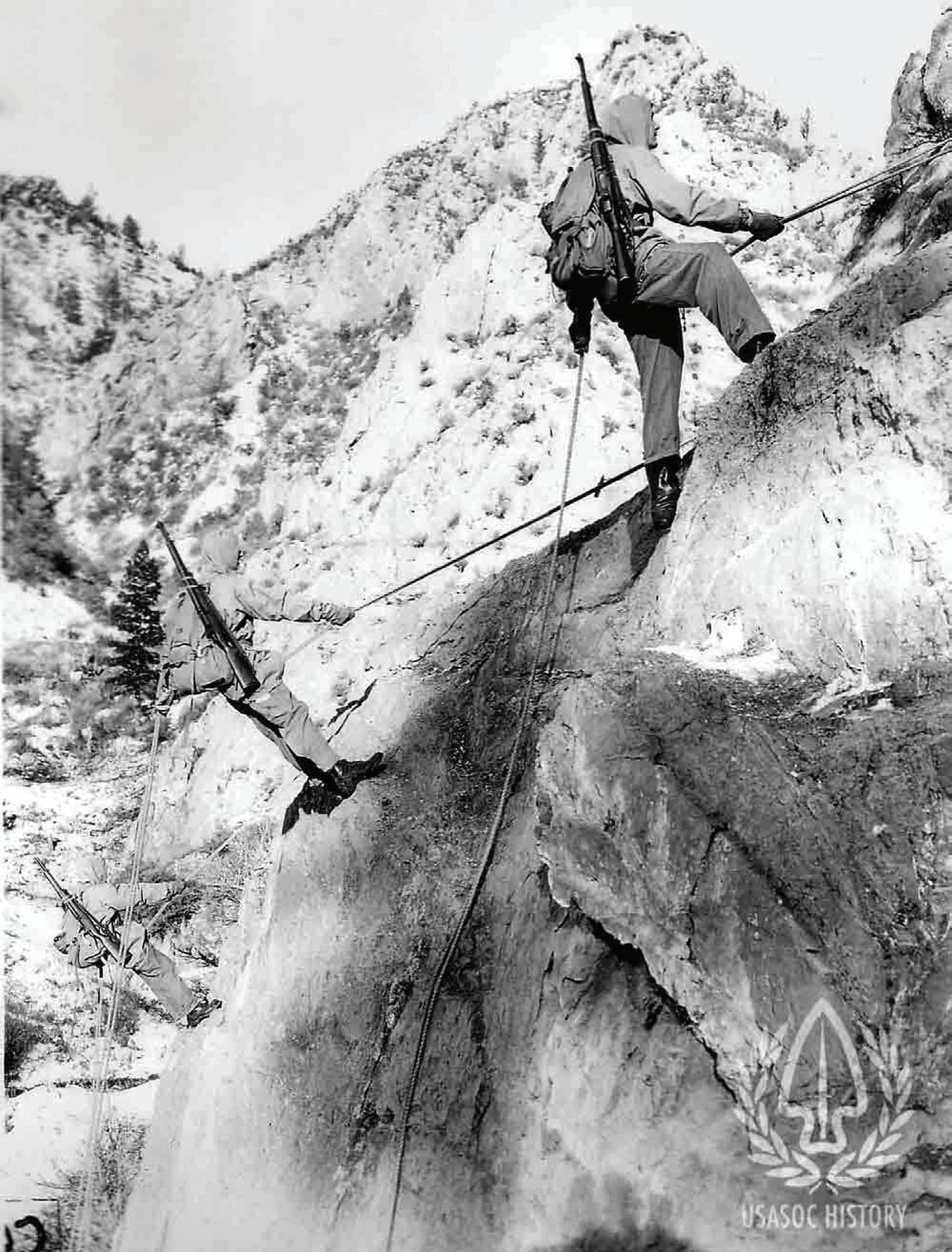

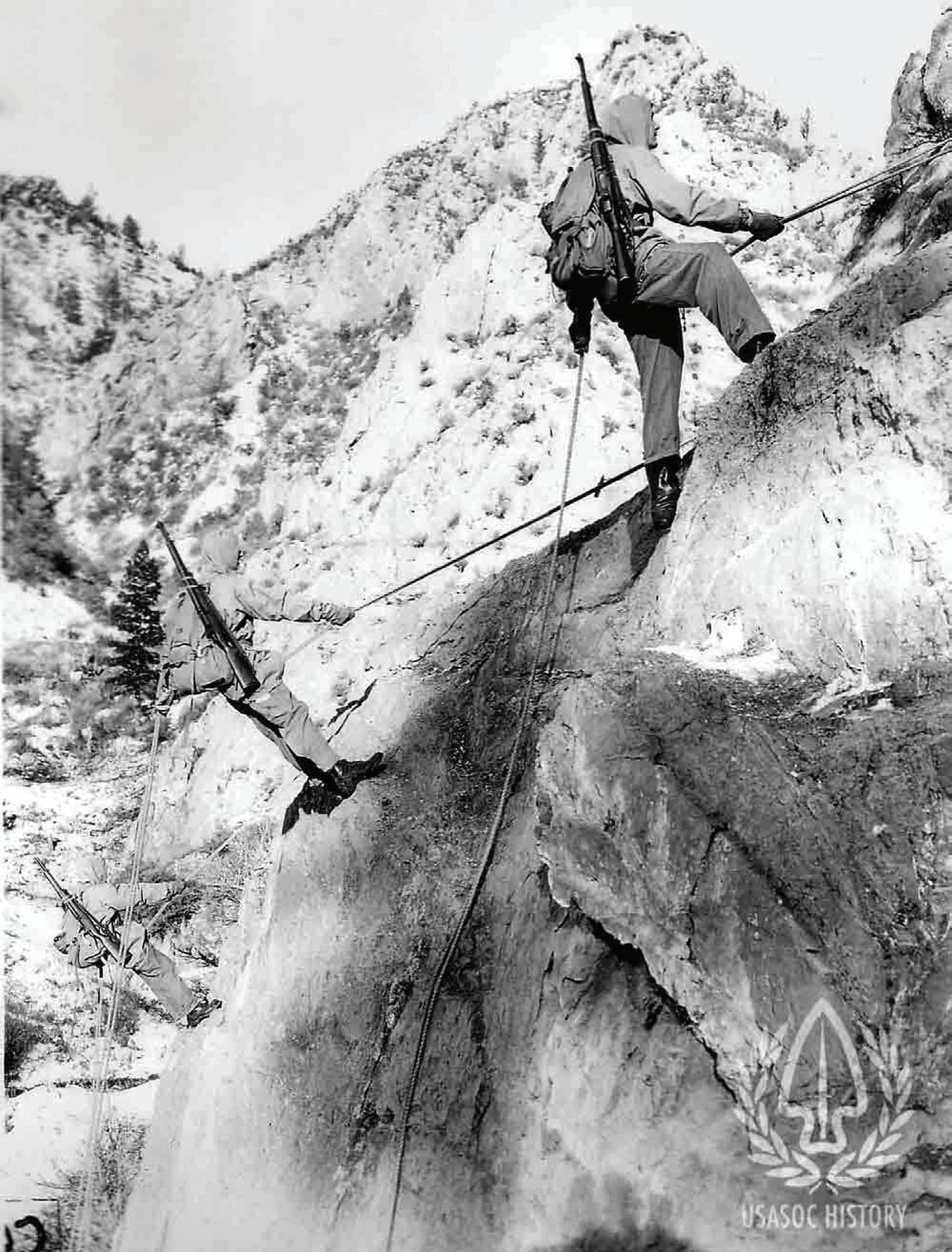

The Force’s training was designed to prepare the men for operations in cold weather and mountainous regions. To say that the training was physically rigorous was an understatement. An official Canadian report noted, “The programme of physical training was designed to produce a standard of general fitness and stamina capable of meeting the severest demands made upon it by fatigue of combat, unfavorable terrain, or adverse weather. This physical

21 FIRST SPECIAL SERVICE FORCE U.S. ARMY PHOTO U.S. ARMY PHOTO NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Top: FSSF personnel undergoing mountain training at Fort William Henry Harrison, Montana. The training served them well in the mountainous terrain of the Italian campaign. Above:

FSSF Commander Brig. Gen. Robert T. Frederick with Lt. Col. Robert W. Moore, commander of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment, during combat near Ceretto Alto, Anzio, Italy, where the FSSF were sent after the Monte la Difensa battle. Note the red arrowhead of the FSSF insignia on Moore’s shoulder. Right: Men of 3rd Regiment, First Special Service Force, take a break in the cold on the way up into the mountains.

Top: A Forceman of the First Special Service Force (FSSF) fires his Johnson light machine gun (LMG) in Italy, an example of some of the non-standard equipment employed by FSSF. The Johnson LMG was used only by FSSF, Marine Raiders, and Paramarines during World War II. While it was preferred over the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), it never achieved wide use. Left: A Forceman fieldstripping his Johnson LMG. Weighing less than 14 pounds fully loaded, it was much lighter than the BAR, had a barrel that could be changed, and could not only vary its cyclic rate from 300 to 900 rounds per minute, but could fire semi-automatic.

training has been built up to such a pitch that an ordinary person would drop from sheer exhaustion in its early stages.” The Forcemen learned how to ski, climb steep slopes, and travel long distances over rugged terrain while carrying a rucksack and weapons with a total weight of more than 70 pounds.

The “Force,” as it was informally called, was classified as light infantry. It contained a total of 2,400 men. The combat echelon included the Force Headquarters and three regiments of two battalions each. Each battalion was divided into three companies, each company into three platoons, and each platoon into two sections of 12 to 16 men each. Officer and non-commissioned officer appointments were integrated, without regard to nationality, on a proportionate basis to personnel of both countries. The only exception to this integrated arrangement was that the service echelon was composed entirely of U.S. personnel. This was because the unit would be supplied through the U.S. Army G-4 system. Thanks to the unit’s unique administrative position as part of the general staff (which meant Frederick reported directly to Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Marshall), Frederick was able to requisition for his men weapons, vehicles, and supplies that other, less well-connected units could only envy. It may have been light infantry, but it was heavily armed light infantry.

22 Special Operations Outlook NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

23 FIRST SPECIAL SERVICE FORCE NATIONAL ARCHIVES

The First Special Service Force’s command post in the mountains near Radicosa, Italy, January 1944.

Above: Men of the FSSF 2nd Regiment carry supplies in support of the 1st Regiment’s assault on Monte la Difensa. The steep terrain meant everything had to be hauled by mules or men. Right: Forcemen fighting in the mountains of Italy. At times it was impossible to dig in, and rock sangars had to be constructed instead to provide cover.

The First Special Service Force’s administrative classification placed it outside the control of Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair’s Army Ground Force (AGF), a fact that did not sit well with McNair. Before the Force could be deployed, McNair insisted that it prove it was up to AGF standards.

On June 15, 1943, an AGF inspection team arrived to certify the Force was qualified for commitment overseas. The inspection included road marching, physical fitness, and individual tests on military subjects. Minimum passing grade was 75 percent. The Forcemen’s scores were literally off the charts – the average score for the unit itself was 125 percent. On some tests, like those that measured strength and speed, individuals scored as high as 200 percent. Frederick had so thoroughly trained his men that tests designed to assess night operations proficiency proved to be child’s play; the Forcemen were so skilled in the use of map and compass that they never got lost, no matter how dark the night or unfamiliar the terrain,

and regardless of weather conditions. In its report to AGF Headquarters, the inspectors stated that the First Special Service Force “was ready for combat.” Additionally, they informed Frederick that the Force demonstrated the coordination and teamwork of a championship professional ball club.

Their extraordinary physical condition, and their many technical and combat skills, would be put to the test in the capture of la Difensa.

La Difensa was part of a 6-mile long, 4-mile wide complex of steep peaks and ridgelines averaging about 3,000 feet in height and known as the Camino hill mass. La Difensa formed the “forward position” facing Clark’s troops, and as its name suggests, seemed designed for defense. The northeast face was particularly imposing. Near the top was a cliff 200 feet high with a 70-degree slope, and above that was a series of six ledges, each averaging about 30 feet in height. Only after all that was overcome was the summit reached.

24 Special Operations Outlook FIRST SPECIAL SERVICE FORCE

U.S. ARMY PHOTO

Defending the mountain were about 400 men, including the veteran 3rd Battalion, 104th Panzergrenadier Regiment and elements of the 3rd Battalion, 129th Panzergrenadier Regiment. The 115th Reconnaissance Battalion was held in reserve. The German defenses were formidable. Interlocking machine gun and mortar positions were dug into the rock, making them impervious to artillery fire. Narrow trails and natural approaches were mined and covered by well-camouflaged snipers. German forward observers could call down accurate artillery fire, and forces on one hill could count on support from other units stationed on nearby summits and ridges. The only weakness in la Difensa’s defenses was on the northeast side. Deemed impassable even by locals, this part was lightly guarded.

The FSSF arrived in Naples on Nov. 19 and was quickly transported to the staging area. Frederick was told the Force would be assigned to II Corps and attached to the 36th Division. Its mission was to take la Difensa on Dec. 3 and then press forward and take Monte la Remetanea. Simultaneous attacks by X Corps and the 36th Division would be conducted against Monte Camino and Monte Maggiore respectively. The attacks would be preceded by combined air raids and artillery barrages.

While his men got ready for their first battle, Frederick conducted reconnaissance. He then devised an audacious plan of his own, one that called for speed, surprise, and shock to swiftly

overcome the enemy. He decided to attack at night and directly up the steep northeast slope. If things went as he believed they would, his men would conquer la Difensa before the Germans realized what had happened.

The artillery and air attacks began on Dec. 2. About 900 guns delivered high-explosive, white phosphorous, and smoke shells in what was the largest artillery barrage at the time. During one hour alone, 22,000 rounds blanketed la Difensa. Though participants later said that it appeared as if “the whole mountain was on fire,” the results would prove mixed. Some areas suffered heavy casualties, while other, more well-protected emplacements experienced no greater discomfort than a loss of sleep.

At approximately 1800, the FSSF began its assault. Scaling rope ladders and groping for hand and footholds in the rain-slick rock wall while carrying a pack and weapon load that “would have forced lesser men to the ground,” the 600-man force silently made its way to the summit. By 0430, three companies had reached the summit undetected. As they were preparing an assault line, some men tripped over loose stones placed there by the Germans to provide a warning.

Suddenly, the night sky was illuminated by red and green flares. As one participant later said, “All hell broke loose.” The German defenders frantically worked to reposition their emplaced weapons to address attack from the unexpected quarter. Though the

25 FIRST SPECIAL SERVICE FORCE U.S. ARMY PHOTO

Forcemen came under heavy fire, it was uncoordinated; surprise was on the Force’s side. The Forcemen advanced, breaking into smaller units to conduct fire and maneuver assaults against one German strongpoint after another. By 0700, the Force was in possession of the summit.

The original plan called for the Force to promptly exploit the success with an attack on la Remetanea. But exhaustion, a lack of ammunition, and the fact that it would take at least 6 hours to get sufficiently resupplied caused Frederick, who had accompanied the battalion, to suspend that part of the assault until Dec. 5. The Force reorganized and consolidated its position on la Difensa in anticipation of the German response. Because the British X Corps’ 56th Division had failed to take nearby Monte Camino and would not succeed in doing so until Dec. 6, the Forcemen on la Difensa were subjected to punishing mortar, long-range machine gun, Nebelwerfer six-barrel rocket artillery, and sniper fire from both Camino and la Remetanea. Adding to the Force’s plight was the constant rain and sleet and brutal cold.

Supplying the men on the summit became a supreme test. Because mules could not handle the steep grade or treacherous footing, everything had to be hand carried. At one point, Frederick sent down a special request for medical supplies: six cases of bourbon and six gross of condoms. When this request reached II Corps, the outraged quartermaster demanded to know what exactly the Force had discovered on the top of la Difensa

that called for prophylactics and liquor. As Geoffrey Perret wrote in There’s a War to be Won, “Alas, what the Forcemen had found wasn’t party-loving, free-spirited women but coldness so intense it froze the sweat under a man’s clothing the moment he stopped moving. A shot of bourbon would help warm him up. The condoms were for protection against the incessant sleet that the howling wind blew down rifle barrels.”

The next two days became a chaotic, seesaw battle under some of the worst weather conditions imaginable, in which each side attempted to gain the advantage over the other. Finally, on Dec. 5, the Force launched an attack on la Remetanea with two reinforced battalions. The attack was stopped at the mid-way point by a desperate German defense. But that defense proved to be a thin – though hard – crust. A follow-up attack early the next morning encountered light opposition. By noon the next day, the Forcemen had captured Remetanea. During the next two days, they conducted mopping up operations.

On Monday, Dec. 6, in tidy, precise penmanship and punctuation, Frederick wrote a dispatch to his command post. The only hint of his exhaustion was the fact that he erroneously dated the message “November 6”: “We have passed the crest of 907 [la Remetanea]. We are receiving much machine gun and mortar fire from several directions … Men are getting in bad shape … I have stopped burying the dead … German snipers are giving us hell and it is extremely difficult to catch them.” He concluded by writing, “I am OK, just uncomfortable and tired.”

The Fifth Army’s left flank was secure, but it was a costly victory. The Force had sustained more than 30 percent

26 Special Operations Outlook FIRST SPECIAL SERVICE FORCE U.S. ARMY PHOTO

Then-Col. Robert T. Frederick leads the FSSF command section out of the village of Radicosa after it was taken.

casualties, with 73 killed, nine missing, 313 wounded or injured, and 116 incapacitated from exhaustion and exposure.

The official history of the Italian campaign noted, “The mission against la Difensa was fully suited to the First Special Service Force. It took advantage of the Force’s special training in night fighting, mountain climbing, cold weather, and lightning assault. No conventional unit, without special training, could have accomplished the mission.”

Clark and the rest of the Fifth Army were in awe over the unit’s accomplishment. He and his planners estimated that the FSSF would take la Difensa in three

days. It was captured in 2 hours. In its first real battle, the First Special Service Force’s reputation as an extremely capable and hard-hitting raiding force for mountain operations was made.

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who knew Frederick from their general staff days and who was the person who ordered Frederick to organize and command the unit, paid a visit to the area shortly after the capture of Monte Camino. In his book, Crusade in

Europe, he wrote, “I was taken to a spot where, in order to outflank on these mountain strongpoints, a small detachment had put on a remarkable exhibition of mountain climbing. With the aid of ropes, a few of them climbed steep cliffs of great height. I have never understood how, encumbered by their equipment, they were able to do it. In fact, I think that any Alpine climber would have examined the place doubtfully before attempting to scale it. Nevertheless, the detachment reached the top and ferreted out the German Company Headquarters. They entered and seized the captain, who exclaimed, ‘You can’t be here. It is impossible to come up those rocks.’”

27 FIRST SPECIAL SERVICE FORCE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

Presentation of Silver Stars to three men of the FSSF in March 1944 at their headquarters in Nettuno, Italy.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES 28 Special Operations Outlook THE THOMPSON SMG

ICONIC WEAPONS THE THOMPSON SMG

BY CHUCK OLDHAM

yDespite being possibly the most famous and recognizable submachine gun of all time, the iconic Thompson SMG was something of a late bloomer, developed for one war and saved by the next. Envisioned by retired U.S. Army Col. John T. Thompson (who coined the term submachine gun) as a handy, pistol-caliber automatic weapon to sweep enemy trenches during World War I, the Thompson SMG was developed too late to enter service in the war for which it was designed. Thompson had formed the Auto-Ordnance Corporation in 1916 to design, manufacture and sell his submachine gun, and despite the end of the war, he was determined to manufacture it. Lacking its own factory, Auto-Ordnance contracted Colt to build 15,000 Thompsons. Unfortunately, when it appeared in 1921, there were few takers among the military and law enforcement customers to which it was marketed. While it found notoriety as the “Tommy Gun,” “Chicago Piano,” “Chicago Typewriter,” and “Chopper,” beloved by the gangsters and bootleggers of the Prohibition era, they actually constituted a very small percentage of the company’s customer base. The U.S. Postal Inspection Service bought some, the Marine Corps bought several hundred, Chinese warlords bought some, the Irish Republic more than 600, union-busting corporations and local friendly state police several dozen more. Law enforcement agencies, banks, and security firms were bigger customers, but even so, only a few thousand Thompsons were sold by 1928. The weapon had earned a name for itself, but very little else.

The U.S. Navy finally bought 500 that year, demanding a few modifications,

Opposite page: A Marine Raider takes a break, M1928 or M1928A1 Thompson in his lap, between attacks on Edson’s Ridge, Guadalcanal. Note the 50-round drum magazine in the weapon and the fivepocket magazine pouch holding 20-round magazines to the Marine’s right.

including a reduction in the rate of fire. Auto Ordnance selected 500 of the thousands of M1921 Thompsons still sitting in its warehouse, made the modifications, stamped an 8 over the 1 in “M1921” on the receiver, and everyone was happy. Or at least temporarily solvent. Thompson himself was replaced as president of his own company with thousands of Thompsons still gathering dust, and Auto-Ordnance changed ownership, operating on a shoestring for the next decade. On the eve of World War II the company was on the verge of being broken up for its assets. The war saved it. Paying the equivalent of $3,000 for a Thompson was difficult to justify in peacetime. In war, it was the price of survival. In 1938, as war loomed, the U.S. military made its first large purchases of Thompsons. The French ordered several thousand, the British more than 100,000. Auto-Ordnance, which owned all the tooling, contracted with Savage to quickly restart production.

The price, still hovering around $200, remained too expensive, and production still too lengthy, and the Thompson was simplified to shrink both.

The Thompson’s “delayed blowback” action was based on the “Blish Lock,” an inclined wedge of phosphor bronze dropped into the bolt assembly that was supposed to slow the cyclic rate by the principle of static friction between two different metals. The truth was, it was needlessly complex and it was unnecessary. It was dropped, and the Thompson became a simple blowback action. The checkered bolt handle at the top of the gun was simplified and moved to the right side of the receiver. The “Cutts Compensator” at the end of the barrel that was supposed to help keep the muzzle down during automatic fire likewise was judged unnecessary and removed. The finely engineered cooling fins on the barrel weren’t needed. The vertical foregrip was replaced with a horizontal forestock. The complex rear

sight was replaced by a simple steel L with a notch at the top and a hole drilled through below it. The M1921 through M1928A1 models could use 50- and 100-round drum magazines, but combat use had shown them to be complex to load (and wind up), fragile, loud, with the loose rounds clacking back and forth, and difficult to mount to the weapon (slid in sideways, with the bolt held back during the entire operation). Provision for their use was dispensed with in favor of 20- and 30-round stick magazines. All these changes, and a few more, resulted in the M1 Thompson. A few more changes, such as adding protective ears to the rear sight, which was prone to catching on things, machining the firing pin to the face of the bolt, and strengthening the rear stock, led to the M1A1. These changes cut manufacturing time in half, and the price fell, first to about $70 a copy, then all the way down to less than $45 by 1944. More importantly to those who carried them in battle, they cut almost a pound off its weight.

The Thompson was used first and foremost by special operators. When the famous photo of Winston Churchill holding a Thompson was trumpeted by German propagandists as proof of the Allies being headed by gangsters, there were only a few dozen in the entire kingdom, but British Commandos soon scooped all of them up. Marine Raiders, Rangers, OSS, paratroopers, and other special operations forces outfits received Thompsons when low production numbers still made them an exclusive weapon, and they remained symbols of elite status even when production ramped up. More than 1.7 million were made during the course of World War II.

The Thompson was a more reliable and accurate submachine gun than most, tended to be less fussy about being kept perfectly clean, and had unrivaled stopping power because of its .45-caliber cartridge, but it had its detractors. Weight remained one of the chief complaints – as much as an M1 Garand. Another complaint, in the Pacific, was that its slow, heavy .45-caliber rounds, while great man-stoppers, failed to penetrate jungle foliage. Nevertheless, most who depended on the SMG swore by it, and when the lighter, cheaper M3 and M3A1 “grease gun” began to replace it, many refused to give up their Thompsons. The last one was officially retired from U.S. service in 1971.

29

THE THOMPSON SMG

CARPETBAGGERS AIR ARM OF THE OSS IN EUROPE

BY DWIGHT JON ZIMMERMAN

BY DWIGHT JON ZIMMERMAN

yCharged with conducting espionage activities behind enemy lines in World War II, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) relied on dedicated U.S. Army Air Forces special operations air groups to provide aerial support for its missions. In the China-Burma-India theater of operations, those missions were the responsibility of the 1st Air Commando Group, whose motto was “Any Place, Any Time, Anywhere.” In the European theater of operations, the OSS had the 801st/492nd Bombardment Group – the “Carpetbaggers,” a nickname taken from the first codename for its missions.

Originally formed as the 801st Bombardment Group (Provisional), it was stationed in Harrington, a former Royal Air Force base in Northamptonshire, about 50 miles north of London, and initially composed of Army Air Force anti-submarine warfare (ASW) squadrons relieved of that duty when the U.S. Navy received delivery of its own ASW aircraft. Upon receiving additional squadrons in August 1944, it was redesignated the 492nd Bombardment Group, taking on as cover the former designation of a daylight bomber group that had taken so many casualties it had to be disbanded.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO 30 Special Operations Outlook

A Carpetbagger crew prepares to drop agents into occupied Europe under cover of darkness.

Because ASW B-24s were designed for low-level flight, they did not have the equipment necessary for high-altitude bombing missions. Though useless for high-altitude strategic bombing, the ASW Liberators were the right planes at the right time for the type of nap-of-the-Earth missions the OSS planned. After swearing everyone to secrecy, OSS officers interviewed the squadron officers and crews

for volunteers. Those declining were reassigned without prejudice. The B-24s were modified for their new missions, the most distinctive feature being the removal of the ball turret and modifying the hole it left behind with a hatch called the “Joe hole.” (Men dropped behind enemy lines were called Joes and women were called Janes or Josephines.) The Joe hole was a smooth metal shroud 44 inches in diameter at its

NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO 31 CARPETBAGGERS

Top: Carpetbagger B-24H “Miss Fitts” takes off from Harrington in daylight. Note that the nose and ball turrets have been removed, and the Liberator is wearing its gloss black anti-searchlight paint. Above: A Joe preparing to drop through the “Joe hole” aboard a Carpetbaggers B-24. The Joe hole usually conveniently employed the hole left behind by the deleted ball turret, with edges smoothed by a sheetmetal lining and a hinged piece of plywood covering it. Right: An aerial view of hardstands, runways, and facilities at Area T at Harrington.

H-type supply containers being loaded aboard the bomb bay of a Carpetbaggers B-24. The H-type containers could be separated into five separate segments so that a single segment could be carried by one man.

base and 48 inches at its exit. A hinged plywood door covered it during flight. On either side were strongpoints that could each anchor eight static lines that would pull open agents’ parachutes once they dropped a sufficient distance from the aircraft. When the aircraft reached its drop-off site, a green light would flash and the agent, a static line attached to his parachute, would slide down the Joe hole and parachute into the darkness.

Col. Clifford J. Heflin, commander of the 22nd Anti-submarine Squadron, was named commander of the 801st Bombardment Group (Provisional) and would remain the Carpetbaggers’ commander through most of the war. The Carpetbaggers began operations, dropping agents and supplies into occupied Europe, in January 1944.

Such missions were harrowing and demanded a high degree of skill and nerve from the crews. They quickly became

adept at identifying landmarks and reached a skill level that made them able to conduct missions in adverse weather conditions that otherwise grounded conventional squadrons.

By mid-September 1944, the Allied armies’ rapid advances across northern France in the wake of Operation Cobra and up from the South of France with the Dragoon amphibious landings closed the chapter of Carpetbagger missions supporting the French Resistance and opened a new, multitasking one that started with the ferrying of fuel. The liberation of France had precipitated a crisis: an acute gasoline shortage that threatened to stop the Allied armies in their tracks. The Carpetbaggers were assigned to airlift gasoline to Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s Third Army. In less than a week after the cessation of Resistance missions, modified Carpetbagger B-24s were ferrying gasoline to the front.

Every space on the aircraft that could carry fuel did. The bomb bay contained four 500-gallon fuel bladders. An additional 1,000 gallons were contained in P-51 drop tanks installed in the fuselage behind the bomb bay and over the Joe hole. Finally, the auxiliary fuel tanks were sealed off to prevent contamination of the higher-octane aviation fuel and filled with 80-octane gasoline for the tanks. Though the additional tanks were vented to the outside, the crews were never entirely comfortable with the flights. Landings were particularly challenging as the planes’ destination fields were either dirt landing strips hastily prepared by Army engineers, or recently liberated Luftwaffe fighter bases with short runways that were being cleared of mines even as the Liberators were landing.

Fuel-hauling operations ended on Sept. 30, with the Carpetbaggers delivering 822,791 gallons of gasoline. Instead of removing and replacing the contaminated gas tanks in the modified Liberators, B-24 production had increased to such a pace that the squadrons were simply issued new B-24s.

CARPETBAGGERS 32 Special Operations Outlook

NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

Above: A B-24 dropping containers at low level in daylight. While most missions took place at night and at low level, personnel were usually dropped at 600 feet, and containers and supplies at 300 to 400 feet. The parachute of the container can be seen just opening below the Liberator. Right: B-24 Carpetbaggers Liberator, tailcode “K”, on a hardstand at Harrington. The gloss black paint was found to be more effective against searchlights than a matte black finish.

The clearing of the French-Swiss border by the end of September 1944 made it possible for the repatriation of interned American aircrews that had been forced to land or parachute into neutral Switzerland. A processing center was established at the Hôtel Beau Rivage at Lake Annecy, about 15 miles south of Geneva. From October 1944 to mid-February 1945, when new arrangements made the Lake Annecy mission unnecessary, the Carpetbaggers processed 783 airmen.

Meanwhile, up north at Leuchars Field in Scotland, near Aberdeen, Carpetbaggers were conducting a variety of missions to Scandinavia. The first and largest of these was Project Sonnie, or Operation Sonnie, which began on March 31, 1944. In addition to dropping agents and supplies to the Norwegian Resistance, Sonnie operated a clandestine airline. Unmarked, unarmed B-24s modified to carry passengers and flown by aircrews wearing civilian clothes transported from Stockholm to Scotland 2,000 Norwegian aircrew trainees as well as American airmen interned in Sweden. As Sweden conducted commercial relations with Germany, American aircrews had the unsettling experience of parking their aircraft within spitting distance of the Germans’. During its 15 months of operation, the “Carpetbagger airline” carried about 4,300 passengers out of Sweden.

Project Sonnie had the distinction of pulling off one of the great intelligence coups of the war. On June 13, 1944, at Peenemünde on the Baltic coast, Nazi rocket scientists launched A4 flight No. V89, a test flight of the ballistic missile later known as the V-2. The ground controller lost sight and control of the V89, which crashed about 200 miles away near Kalmar, in southeast Sweden. Swedish authorities gathered the debris and, following secret negotiations between the British and Swedish governments, Lt. Col. Keith Allen flew a Carpetbagger C-47 to Stockholm, where he picked up the wreckage and carried it back for study in England.

33 CARPETBAGGERS NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

No Federal endorsement of sponsor intended. As the premier digital integrator for DOD, Booz Allen brings trailblazing technology to the forefront of the mission. We deliver advanced solutions for the digital battlespace. Visit boozallen.com/defense to learn more. Know, act and win faster with the digital integrator. www.defensemedianetwork.com

The history of the Carpetbaggers also includes a remarkable rescue that occurred on the night of June 27, 1944, near West Eaton, roughly 20 miles east of Harrington. Lt. William E. Huenekens and his crew were flying at about 1,800 feet and returning to Harrington after completing a training mission.

Suddenly tail gunner Sgt. Randall “Randy” Sadler saw the approaching silhouette of a Junkers JU-88 nightfighter. Sadler shouted a warning just as the JU-88 intruder opened fire. Cannon shells ripped through the Liberator, killing two and starting a fire in the bomb bay. Huenekens ordered the survivors to bail out. Navigator 2nd Lt. Bob Callahan and bombardier 2nd Lt. Bob Sanders were in the nose. Sanders tried to grab his parachute that was hanging by the bomb bay, only to discover it was on fire. He returned to find Callahan, wearing his chest-mounted parachute, preparing to exit the aircraft. Sanders shouted the news about his chute to Callahan, who quickly told Sanders to climb onto his back, cross his arms through the back straps of the parachute, and hold tight. Sanders did and Callahan then slid them out of the burning bomber.

Once clear, Callahan pulled the ripcord. The shock of the parachute’s opening almost caused Sanders to lose his grip. Callahan then told Sanders to work his way around to Callahan’s front so that they could better hold onto each other, which Sanders did. They landed in a wheat field, with Callahan suffering a broken

A “Carpetbagger” crew with their modified B-24 Liberator behind them, easily recognizable by its high-gloss black paint and the missing nose turret. The earliest Carpetbagger aircraft were B-24Ds, which had glazed noses without turrets, but when later model B-24s with nose turrets were received, the turrets were replaced with clear Perspex nose glazing at the U.S. Army Air Forces Servicing Center at Burtonwood.

ankle and Sanders spraining one of his and suffering some bruises and scratches. As they began limping toward a nearby road, they heard Sadler calling out. Though badly burned on the head and arms, he had managed to bail out. They were the only survivors.

Callahan was awarded the Silver Star for his role in rescuing Sanders, and the crew all received Purple Hearts. After he heard the story of the rescue, Heflin asked Callahan and Sanders to recreate it. A parachute was rigged to a crane and photographers recorded their recreation. The complete story of the rescue and accompanying photos are posted in the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum section of the Harrington Aviation Museum website.

With Allied armies crossing the German border in January 1945, intelligence about what was happening inside Germany became a priority – particularly when senior commanders received rumors of a last-stand “National Redoubt” in the

35 CARPETBAGGERS NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

Bavarian Alps. Missions inserting agents into Germany were given the codename Joan-Eleanor Project (or JE Project), sometimes also referred to as Operation Red Stocking.

As the missions included drops near Berlin and other deep penetration targets, the Liberators were judged too slow and vulnerable. JE Project missions were assigned to the smaller, faster, newly introduced twin-engine Douglas A-26 Invader. Modified Invaders were stripped of all nonessential equipment. The Joe, wearing an American parachute fitted with a British quick-release harness, was ordered to lie down during the flight on a hinged plywood floor in a special compartment constructed in the bomb bay. When the aircraft neared its drop site, the Joe hooked up his static line and assumed a crouching position. Upon reaching the drop site, the release lever located in the cockpit was pulled, the wood floor dropped open, and the Joe was released bomb-drop fashion (reportedly something none of them liked).

Communications between the agent on the ground and a Mosquito fighter-bomber flying above at 30,000 to 40,000 feet was made possible through the Joan-Eleanor voice/ recorder radio system developed by radio technicians Lt. Cmdr. Stephen Simpson, RCA’s Dewitt R. Goddard, and radio pioneer Alfred J. Gross. The name reportedly was the combination of the first names of Goddard’s wife and Simpson’s girlfriend. The agent was equipped with the Joan voice radio that had a range of about 20 miles. According to a prearranged schedule, the agent would broadcast his messages. Modified de Havilland Mosquitoes equipped with Eleanor recorder sets were judged ideal for the dangerous duty of flying alone over German airspace for the necessary extended time required for communication.

36 Special Operations Outlook CARPETBAGGERS NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

Jedburghs parachute from a Carpetbaggers B-24 Liberator.

The first mission was launched on the night of March 16-17, 1945, and ended tragically, with the low-flying A-26 crashing, killing all aboard. Fortunately, it was the only such mission to do so. Most of the Joan-Eleanor Project missions were conducted from a forward base near Dijon, France, and the inserted agents were able to provide invaluable intelligence.

One mission that wound up having a seriocomic aspect occurred late in the war and involved Project Doctor, composed of two Belgian OSS agents inserted into the Kufstein region of Austria to organize Belgian workers for intelligence purposes and observe military traffic in the area.

The pair successfully parachuted on March 23, 1945, landing in 5 feet of snow. Two days later they reported that they had been rescued by three Wehrmacht deserters seeking to create a local resistance group. On March 22, the three soldiers had spread a large Austrian flag on top of a nearby mountain, hoping to catch the eye of Allied flyers and receive assistance for their movement. The Doctor team’s arrival the following night astonished the deserters, who were impressed with the speed of the Allies’ response. The team did nothing to discourage their belief. Together with the deserters and the addition of another two-man OSS team, Doctor created a network of agents that sent to headquarters 66 messages containing valuable information, including the locations of a jet base near Munich, a trainload of gasoline, and an oil depot near Halle.

When the 492nd Bombardment Group was disbanded in July 1945, it was second only to Britain’s Special Operations

Executive’s air arm in conducting the widest range, both in distance and tasks, of aerial missions imaginable. From Norway to Yugoslavia, Carpetbaggers did everything asked of them, earning numerous individual decorations for valor, helping lay the foundation for future special operations air operations, and receiving a well-deserved Distinguished Unit Citation.

37 CARPETBAGGERS NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

Above: Carpetbagger A-26 Invader “Queen of Spades” at Harrington in 1945, used for Red Stocking missions. Right: A “Joe” and a “Josephine” share a farewell kiss for good luck before departing for Occupied Europe aboard a Carpetbagger aircraft.

THE MAKIN RAID

BY DWIGHT JON ZIMMERMAN

y The Makin Raid in August 1942 by the 2nd Marine Raiders Battalion — “Carlson’s Raiders” — was one of the most famous special operations missions of World War II. Twenty-three men were awarded the Navy Cross — five posthumously — and one Marine, Sgt. Clyde Thomason, would be the first enlisted man to receive (posthumously) the Medal of Honor. It boosted home front morale and inspired the successful 1943

movie Gung Ho (taken from the 2nd Raiders’ motto, Chinese for “work together”) starring Randolph Scott as the 2nd Raiders’ commander, Col. Evans Carlson.

The decision for the Makin Raid came in the wake of the U.S. Navy’s victory at Midway in June 1942, and as an adjunct to the first American offensive in the war, Operation Cactus — the invasion of the Japanese-held island of Guadalcanal in

NATIONAL ARCHIVES 38 Special Operations Outlook

August 1942. Though Carlson wanted his unit to be included in Operation Cactus, Adm. Chester Nimitz, CINCPAC/ CINCPAO (Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet/Commander in Chief Pacific Ocean Area), and his staff decided that Carlson’s Raiders would be more usefully employed as a diversionary force in a small-scale, submarine-launched amphibious operation. Striking deep in Japanese-held territory at or near the same time as the landing on Guadalcanal, it was hoped that the raid would divert and/or delay the movement of Japanese reinforcements and supplies to the island. The challenge was to find the right target.

This was no easy feat, as Nimitz and his staff had a wealth of targets available. They included Wake Island and Attu Island — even the Japanese home island of Hokkaido was considered. Despite the strong emotional appeal of avenging the gallant Marine defenders captured when Wake fell to a Japanese invasion at the end of December 1941, Wake was crossed off as being too strongly garrisoned. Attu and Hokkaido were also rejected as being both too remote and too strongly defended. In mid-July, Makin Atoll in the Gilbert archipelago was selected. The raid was scheduled for Aug. 17, 1942, only 10 days after the start of Operation Cactus.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO 39 THE MAKIN RAID

Above: Makin Island seen through the periscope of the submarine Nautilus (SS168) before the raid. Top right: Sgt. Walter Carroll and Pfc. Dean Winters of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion – “Carlson’s Raiders” – prepare to debark from the Nautilus before the Makin Raid. The strike was designed to divert Japanese attention from the U.S. landings on Guadalcanal and boost American morale. Above right: U.S. Marine Raiders exercise on the deck of Nautilus while en route to raid Makin, in the Gilbert Islands, on Aug. 11, 1942. One of the submarine’s two 6-inch deck guns and an ammunition hoist are in the center of the image

The challenges facing Carlson’s Raiders were daunting. It was believed that Makin was lightly defended, but in truth, intelligence of the atoll and the Japanese garrison there was thin to non-existent. Estimates of the Japanese garrison ranged from that of a token force to as high as 350 on the atoll’s main island of Butaritari. After being told by Nimitz, “We’re short of men, short of ships, and short of planes,” Carlson was informed he would only have two submarines, the Argonaut and the Nautilus, assigned to the mission. Carlson faced significant mission-training challenges as well. His Raiders would have less than a month to train, and the submarines would not be available for training until a day or two before the launch of their mission. Most troubling of all, though they were the largest in the Navy’s fleet at that time, the submarines did not have sufficient space for the battalion and its

gear and supplies. The Argonaut could accommodate 134 passengers and gear. The Nautilus was even more restricted, capable of accommodating only 85 extra men and equipment. This meant that 55 Raiders would have to remain behind at their base at Pearl Harbor.

One of the few things definitely known about Makin was the existence of rough surf. Training in the standard, 11-man

inflatable rafts was done off Barber’s Point, where the conditions were reckoned to match what the Raiders would encounter at Makin. One of the most difficult decisions Carlson had to make at this stage was deciding who would go and who would remain behind. Carlson’s dilemma was complicated by the one Raider who steadfastly refused to stay at Pearl Harbor, Maj. James “Jimmy”

THE MAKIN RAID 40 Special Operations Outlook

Above: Smoke from burning gasoline tanks on Makin Island, seen from Nautilus while she was waiting to remove Marine Raiders from the island. Right: A sailor painting a Japanese flag and hash marks on the deck gun of Nautilus. This denotes the two Japanese ships sunk in the raid on Makin Atoll.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Roosevelt, his executive officer and son of President Franklin Roosevelt. Because of the high risk, Nimitz and Carlson had agreed not to include Maj. Roosevelt on the mission. Roosevelt vigorously protested, arguing that his place was with his men. When his protest was rebuffed, he did something that he rarely ever did in the war – he phoned his father. It was later reported that President Roosevelt called Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Ernest J. King and told him, “Look, my son’s an officer in that battalion. If he doesn’t go, no one goes.” Maj. Roosevelt would lead the group of Raiders assigned to the Argonaut Butaritari, which forms the southern base of Makin, is the largest island in the atoll. Carlson’s mission was to stage a one-day raid on Butaritari lasting 13 hours, starting just before dawn. They were to kill any Japanese troops encountered, destroy Japanese buildings and facilities, and gather anything of intelligence value.

On Aug. 8, the Argonaut and Nautilus departed Pearl Harbor on independent, zigzag courses designed to confuse the enemy if they were spotted. They would meet again at the rendezvous site the morning of the raid.

41 THE MAKIN RAID NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES PHOTO

Above left: Marines of the 2nd Raider Battalion aboard Nautilus after returning from Makin Island. The Marine in the foreground holds a Japanese rifle and web gear. According to the original photo caption, he used it to shoot and kill a Japanese soldier after he captured it. Above: Two U.S. Marine Raiders pose with a pistol and a captured Japanese rifle aboard Nautilus after returning from Makin Island. The Marines are Cpl. Edward R. Wygal (left), who used a hand grenade to wipe out an enemy machine gun, and 1st Sgt. C.L. Golasewski. Left: Lt. Col. Evans F. Carlson, commander of the U.S. Marine 2nd Raider Battalion, still in his field gear aboard Nautilus just after returning from Makin Island, Aug. 18, 1942. He is armed with an M1911 .45 caliber pistol in a cross-draw holster.

The trip to Makin was cramped and stifling, but uneventful. Not so, however, was the amphibious assault. When the submarines surfaced at about 3:30 a.m. on Aug. 17, the men discovered a gale blowing in full force. In swells reaching 15 feet, the Raiders clambered out into the stormy, tropical night and onto the slick, heaving decks of the submarines, struggling to pull boats from their storage berths, inflate them, and drag them to the debarkation stations. It was only with great difficulty that the Marines were able to launch and board their boats, timing their leaps when the boat was at the peak of a swell. Because of a faulty design that left the sparkplugs of the boats’ outboard motors unprotected (a situation the Raiders were unable to correct even after jury-rigging a shield), almost all the outboard motors shorted out, forcing the Marines to employ what they wryly called the boat’s “auxiliary power source” — the paddles.

At about 4:30 a.m., with the storm beginning to abate, 32 rubber boats headed toward the beach. The original plan called for the two companies, A and B, to reach separate beaches on the southern shore of Butaritari in a coordinated landing. But because of the chaos of the launch and the

culty in reaching the beach, Carlson changed the plan so everyone would land together at one site. There were some

hair-raising moments caused by the heavy surf flipping over some boats upon landing. But as dawn was breaking, Carlson was able to radio back to the submarines that all the Marines were safely on the beach. Because of the chaos of the landing, he was unaware until much later that three boats had become separated. These crews would only much later be reunited with the main force.

42 Special Operations Outlook THE MAKIN RAID NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES

diffi -

Above: Marines and sailors aboard Nautilus as she entered Pearl Harbor after the Makin Raid, Aug. 25, 1942. One of the men, in second row, left center, is holding a Japanese rifle captured on Makin. Some of the Raiders are still wearing the uniforms they dyed black for the raid. Right: Lt. Col. Evans F. Carlson, USMCR, (left), and Maj. James Roosevelt, USMCR, receive the congratulations of Brig. Gen. H.K. Pickett, USMC, (right), upon their return from the successful Makin Island Raid.