2 minute read

Advancing scientific frontiers through undergraduate research

Inquisitive McGill students present the highlights of their curiosity

Russel Ismael Science & Technology Editor

Advertisement

Continued from page 1.

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulators (CFTR) from patients with CF are currently being sequenced to deduce the exact genes that cause CF. As opposed to a panel test, which screens against a common set of mutations, CFTR sequencing has fewer false positives.

“We’re able to now discharge all these people we can identify as healthy carriers of cystic fibrosis,” Parish explained in an interview with the Tribune “ You need two cystic-fibrosiscausing alleles to have cystic fibrosis, [but] they have one allele that’s cystic-fibrosis-causing, and one that’s normal.”

Despite fewer false positives, CFTR sequencing can still produce inconclusive tests, leading to over-medicalization— when your health is harmed because of undue treatment— which has unknown long-term side effects. But this is balanced by how versatile CFTR is, as it isn’t limited to CF.

“[CFTR sequencing] can be applied to any kind of genetic disease. In some cases, that already is being applied,” Parish said. “Identifying [CF] mutations and new mutations would be useful.”

Poetry as a mathematical language

Eve-Marie Marceau, a recent graduate from McGill’s Département des littératures de langue française, de traduction et de création, is researching how words can be translated into a mathematical context to devise a way of evoking the “sublime” in poetry.

“Edmund Burke said that the sublime was, and I quote, ‘the strongest emotion that the mind could feel,’” Marceau told the Tribune Marceau almost experienced the sublime after having an inexplicable emotion when reading a poem.

“I was like [...] ‘what is this kind of emotion I cannot explain?’ So, I went to ask my friend who is doing his PhD in mathematical logic if he could define what I was feeling—the infinity of discovery,” Marceau said.

Marceau and her friend then combined mathematics and poetry to construct a model for the sublime. They used both mathematical and linguistic approaches, including category theory and semantics, but this proved to be challenging.

“The more and more we try to find a model, the less we can really grasp the sublime,” Marceau said. “We realized that poetry was really similar to mathematics in a way that [it] was going toward the sublime, but never reaching it.”

She asserted that the sublime was “the best way to describe the experience of infinity, but in a qualitative way,” and that the sublime is about “hazard and imperfection,” not beauty.

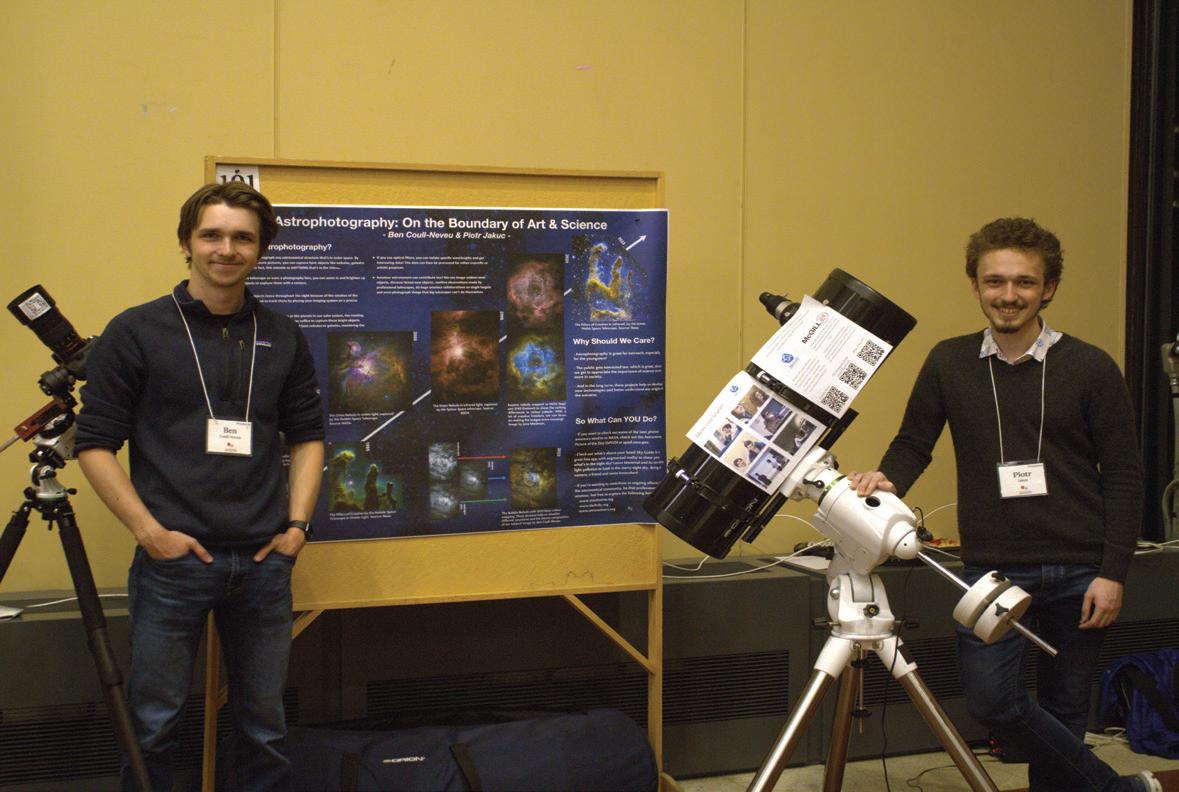

Astrophotography: Intersecting art and science

U1 Science students Ben Coull-Neveu and Piotr Jakuc transformed their astronomy hobby into art. As astrophotographers, both Coull-Neveu and Jakuc carefully control the colour and focus of their photo - graphs for artistic flair.

“A lot of [astrophotography] kind of comes back to the person who processes it to find what they wanted to get out of the image,” Coull-Neveu explained to the Tribune . “Even if they’re using the exact same initial data, the final image will pretty much always come out completely different because it’s their choice as to [...] what colours they really want to bring out on the image.”

When it comes to space photographs, this artistic freedom is also found in the James Webb Space Telescope’s photograph of the Pillars of Creation, which Jakuc states is colour-saturated to give a sense of awe.

“And that’s kind of like the artistic side of things because no one’s supposed to really tell you how to present your pictures if the final goal is to just impress the public,” Jakuc told the Tribune . “At that point, [astrophotography is] just what’s prettiest to you and what’s prettiest to most people.”