T

Editor-in-Chief Madison McLauchlan editor@mcgilltribune.com

Creative Director Anoushka Oke aoke@mcgilltribune.com

Managing Editors Matthew Molinaro mmolinaro@mcgilltribune.com Madison Edward-Wright medwardwright@mcgilltribune.com

News Editors Lily Cason, Juliet Morrison & Ghazal Azizi news@mcgilltribune.com

Opinion Editors Kareem Abuali & Chloé Kichenane opinion@mcgilltribune.com

Science & Technology Editors Ella Paulin & Russel Ismael scitech@mcgilltribune.com

Student Life Editors Abby McCormick & Mahnoor Chaudhry studentlife@mcgilltribune.com

Features Editor Wendy Zhao features@mcgilltribune.com

Arts & Entertainment Editors Arian Kamel & Michelle Siegel arts@mcgilltribune.com

Sports Editors Tillie Burlock & Sarah Farnand sports@mcgilltribune.com

Design Editors Drea Garcia & Shireen Aamir design@mcgilltribune.com

Multimedia Editors Noor Saeed & Alyssa Razavi Mastali multimedia@mcgilltribune.com

Web Developers Jiajia Li & Oliver Warne webdev@mcgilltribune.com

Copy Editor Sarina Macleod copy@mcgilltribune.com

Social Media Editor Taneeshaa Pradhan socialmedia@mcgilltribune.com

Business Manager Joseph Abounohra business@mcgilltribune.com

Joseph Abounohra, Kareem Abuali, Ella Gomes, Shani Laskin, Kennedy McKee-Braide, Madison McLauchlan, Michelle Siegel, Sophie Smith

As The McGill Tribune moves into a new era as The Tribune, we would like to thank every single person who has contributed their time, effort, writing, creativity, and passion to our paper. Without the dedication, curiosity, and fervour for learning that each writer and creative has brought to our community, The Tribune’s mission of holding truth to power would be impossible. To our readers—thank you for trusting us with your stories. Here’s to a bold and brilliant future.

Ali Baghirov, Margo Berthier, Ella Buckingham, Melissa Carter, Roberto Concepcion, Ella Deacon, Julie Ferreyra, Adeline Fisher, Suzanna Graham, Jasjot Grewal, Charlotte Hayes, Jasmine Jing, Monique Kasonga, Shani Laskin, Eliza Lee, Oscar Macquet, Zoé Mineret, Harry North, Simi Ogunsola, Atticus O’Rourke Rusin, Ella Paulin, Dana Prather, Maeve Reilly, Maia Salhofer, Sofia Stankovic, Caroline Sun, Harrison Yamada, Yash Zodgekar

Sophia Micomonaco, Alex Sher, Owen Barnert, Charlotte Bawol, K. Coco Zhang, Theodore Yohalem Shouse, Kellie Elrick

Shatner University Centre, 3480 McTavish, Suite 110

The Tribune is an editorially autonomous newspaper published by the Société de Publication de la Tribune, a student society of McGill University. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of The Tribune and the Société de Publication de la Tribune, and does not necessarily represent the views of McGill University.

James McGill’s violent subordination of Indigenous children and Black people, such as Jack, Sarah, MarieLouise, and Marie Potamiane, and one enslaved person whose name has not been uncovered. McGill frames its founder as a philanthropist, but hardly acknowledges that the donated fortune, the gift that ensured he would be our namesake, was amassed through the exploitation of enslaved people in Canada, the Caribbean, and the slave trade more broadly. His legacy persists, and Black and Indigenous faculty and students are still dramatically underrepresented in number and in the curricula of most academic programs, which fail to reflect demographic, methodological, and epistemological diversity.

We are divorcing McGill from The McGill Tribune . And it’s about time our university changes its name, too.

As McGill entered its third century in 2021, it launched a $2 billion fundraising campaign celebrating its history and legacy as an institution. This campaign, however, illustrated the university’s continued indifference toward its violent, colonial, and racist origins. In June 2020, former McGill art history professor Charmaine Nelson, along with some of her students, released a 98-page research document entitled “Slavery and McGill University: Bicentenary Recommendations,” investigating James McGill’s history as a brutal enslaver and profiteer of the transatlantic slave trade. The document also issued recommendations for the university to begin confronting its violent origins and its ongoing systemic racism both at the student and faculty levels today.

As we have seen at Toronto Metropolitan University, which changed its name in response to widespread student activism urging the institution to stop celebrating colonial figures, it is possible for large universities to take steps to untangle themselves from their violent

histories. Yet, we also recognize that name changes are not the be-all and end-all of social justice and redress. For example, McGill’s varsity sports team renamed itself the ‘Redbirds’ in 2019, dropping a name that caricatured Indigenous people. But this did not stop the university from engaging in a legal battle with the Mohawk Mothers, a group that is demanding there be an investigation into potential unmarked graves under the New Vic site.

Name changes are one small step, necessary but not sufficient in and of themselves. The Tribune will accompany its name change by continuing to hold ourselves accountable through our own journalism, creating more avenues for community engagement and diverse perspectives, and engaging with more student groups on campus.

As a newspaper, we have editorialized countless times on McGill’s persistent failure to create a safe and welcoming environment for Black, Indigenous, and racialized students and faculty, both in the lecture halls and on campus. We must supplement the progress made on the Action Plan to Address Anti-Black Racism set forth by the Office of the Provost and Vice-President Academic to rid McGill of its systemic racism. In its official land acknowledgement, the university fails to mention

The Tribune has in the past been guilty of institutional racism, and as we continue working towards redress and strive to eliminate all forms of institutionalized oppression, our Editorial Board feels it can no longer bear the name that so unapologetically upholds and honours these systems. Our Editorial Board’s hiring process had discriminatory barriers to entry that did not open doors to all, and our channels for ensuring equity and a safe working environment were not made adequately available. We have acknowledged The Tribune ’s history of exclusion toward Black

students, Indigenous students, and students of colour––voices needed for any paper to thrive. Since then, we have revised our Workplace Conduct Policy and application process, and aimed to remedy institutional underrepresentation across all levels. The work does not stop there, and only through continual steps toward redress can we call ourselves a newspaper of record.

Our mandate urges us to be vocal and critical about the systems of oppression persisting on our campus and around the world, centring our perspectives on the voices that journalism has silenced. In order to uplift these narratives, we must also recognize the privilege that allows us to comment at a distance, from a predominantly white and privileged anglophone university in North America. McGill, in its billiondollar marketing campaigns, may be primarily interested in upholding the prestigious veneer of its namesake on an international stage, but as an independent student-led publication, we choose to reject the social capital that associating with McGill and its legacies may yield. If we cannot reject this name, we cannot in good faith stand behind any of the changes we have advocated for. As journalists, we choose to keep speaking truth to power instead of fearing it.

In a plebiscite during the Winter 2023 Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) referendum, students voted overwhelmingly in favour of investing their student fees in Co-op Bar Milton-Parc—a community-led cooperative that aims to create a space for students and local groups to gather.

The café-pub, located at the corner of Parc and des Pins, will be a multifunctional co-working space and meeting place for community events and projects by day, with a lively community bar by night. Bar Milton-Parc has gradually begun opening to the public since July 2022 by hosting occasional events and launching “Co-work Wednesdays”, where the coworking space is open from 4 p.m. to 10 p.m. for members. It hopes to fully open as early as Fall 2023.

The Société de Développement Communautaire Milton Parc (SDC)—a non-profit organization that owns multiple businesses and offices along Parc Avenue—purchased the former Bar des Pins in early 2021. The SDC extended a vote to the Milton Parc community to decide what should be done with the commercial space. The community decided on the creation of Bar Milton-Parc, which aims to become a hub for live events, speaker panels, and community forums. For a one-time fee of $20, members can buy into the cooperative, giving them access to the co-working space and reduced prices on food and beverages.

Malcolm McClintock, a leader of the Bar Milton-Parc project and former Engineering representative to SSMU, has several hopes for the future of the initiative.

“We want to make this a transformative space that is welcoming to all folks,” McClintock said in an interview with The Tribune. “Our main purpose is to provide a space for groups who are animating for the direct community around us.”

Central to the Bar Milton-Parc project is a solidarity meal program, through which the bar hopes to provide affordable meals to the Milton Parc community. The co-op will take a local approach to combat rising food insecurity in Montreal and offer relief to community members and students in need.

“In the near future, we want to be able to offer [a pay-what-you-can system] at least every day of the week for lunch,” McClintock said. “Unfortunately, the infrastructure to support something like that requires a lot of upfront money, something that we currently don’t have. We want to be a transformative space, but that requires renovations, and renovations cost money.”

SSMU vice-president (VP) Finance

Marco Pizarro says there is a possibility of investing five per cent of SSMU’s Capi-

tal Investment Fund into Bar Milton-Parc, but stressed that the recent vote was non-binding.

“Future funding for Bar Milton-Parc ultimately needs to be voted upon by the Board of Directors,” Pizarro wrote to The Tribune via email. “Following interest by the student body, there needs to be consultation with the SSMU finance committee, [the] community engagement committee, and the Legislative Council.”

Five per cent of SSMU’s Capital Investment Fund would represent approximately $150,000, which would greatly accelerate Bar Milton-Parc’s renovation plans and allow it to expand both its opening hours and its services.

“The Co-op Bar Milton-Parc is built on the history of the Milton Parc neighbourhood,” McClintock said. “It is only made possible by the longer standing history of the housing network of cooperatives that have come together with the desire to create a space where the community can gather, and meet the general needs that people have, both socially and physically.”

Delineated by University Street, Avenue des Pins, Saint-Laurent Boulevard, and Sherbrooke Street, the Milton Parc neighbourhood is considered one of Montreal’s historical residential areas. Over 600 buildings in the area, including Bar Milton-Parc, are owned by the Milton Parc Community (CMP), a community-led cooperative that offers affordable housing and various social provisions.

By 1968, Concordia Estates Ltd had bought 96 per cent of the properties in Milton Parc, and planned to demolish the neighbourhood to construct a massive real-estate development project. The residents of Milton Parc came together to oppose the urban renewal project and formed the Milton Parc Citizen’s Committee (CCMP/MPCC) in an effort to preserve the area’ architectural diversity and heritage. After nearly two decades of struggle, only the first phase of the project, the construction of the La Cité Complex, was completed.

Dimitri Roussopoulos, a founding member of the CCMP, recounted the community’s struggle to preserve the neighbourhood during an interview with The Tribune

“We undertook to save this whole six-block area from complete destruction by a company of speculators that wanted to build high-rises, condominiums, and apartment buildings,” Roussopoulos said. “It involved a lot of demonstrations, petitioning, and public information meetings. We created a city-wide coalition to support the struggle [...] and managed to convince the federal and provincial government to give us the money to buy the whole area and renovate it.”

With the aid of Héritage Montréal and the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Cor-

poration (CMHC), the Milton Parc community repurchased the remaining properties between 1979 and 1982, creating the largest cooperative housing project in North America. At this point, the characteristic Victorian architecture of Milton Parc, which dates back to the 19th century, was falling into disrepair.

Phyllis Lambert, director and founder of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, played a pivotal role in the renovations and in securing CMHC’s approval of the project.

“You have to follow your dreams. When we started Heritage Montreal to save buildings from demolition, we had no idea how you could ever occupy these buildings again,” Lambert said. “But we didn’t worry about that. And then, as you work through what the possibilities are, you find solutions.”

In 1987, the National Assembly of Quebec passed a private bill to allow the co-ops and non-profit organizations of Milton Parc to jointly own the land under a syndicate: the Milton Parc Community. The CMP is governed by a panel of representatives from each of the 24 non-profit organizations and cooperatives that coown the land trust.

Unlike a regular land trust, which identifies a legal entity and the assets it has authority over, the CMP is characterized by its unique “Declaration of Co-ownership.” The Declaration includes socio-economic clauses which mandate signatory organizations to uphold social responsibilities and limit real estate speculation in order to maintain low rents in the area.

Milton Parc is home to many community initiatives, including a library on Parc Avenue, which the CCMP runs and that serves as a hub to promote events within the community. Every Friday, the CCMP works with the Saint John’s food bank and distributes 80 to 100 meals to Montrealers in need.

Since the 2000s, the community has actively fought to preserve green spaces in

the neighbourhood. Under Lucia Kowaluk’s leadership, the CCMP thwarted the construction of a high-rise in 2019 in favour of the construction of a park through a successful petition that amassed thousands of signatures. The park, located at the junction of Parc and des Pins, will be named in honour of the late Kowaluk.

Since 2010, McGill’s Office of the Dean of Students, SSMU, and the CCMP have coordinated their efforts through the Community Actions and Relations Endeavour in order to facilitate the coexistence of students and permanent residents of Milton Parc. Tensions have stemmed from the turbulent nightlife of student tenants, as well as the accumulation of trash in the streets during the months of May and June, when many are moving.

“We’re constantly interested in working towards better relations with the McGill faculty and the bigger student body. That’s our sincere hope. But it’s a work in progress,” Roussopoulos said.

SSMU’s endorsement of the Bar Milton-Parc project would not only expedite the bar’s opening, but also result in SSMU being eligible for support-member status at the bar, giving McGill students privileged booking opportunities to host events. SSMU’s investment in the bar rests on the conditions that McGill students be eligible for the co-op’s solidarity meal program and that student groups get priority booking.

Daniel Tamblyn-Watts, 4L, told The Tribune that he regularly frequents the bar because of its ties to Milton Parc and McGill.

“I love that it’s run by a very community-oriented crowd, they give off the vibe they aren’t just trying to turn a profit on you,” Tamblyn-Watts said. “It’s amazing, you can listen to different conversations where people are talking about really interesting things they’re doing in the community, and at the same time, it’s a really low-cost and friendly environment to have a beer with some friends.”

Café-pub-working

Bar Milton-Parc gradually opens to public

McGill’s eighteenth Principal and Vice-Chancellor H. Deep Saini began his five-year term on April 1. Saini hosted a round-table discussion with McGill student media outlets on April 5, during which he answered questions about his plans to work alongside students, Indigenous groups such as the Mohawk Mothers, and unions to strengthen community ties. Saini also outlined his strategies for creating accessible channels for student communication and touched on concerns students may have about his previous tenure at Dalhousie University.

In response to reporters’ questions regarding McGill’s relationships with Indigenous communities, Saini acknowledged that McGill sits on Indigenous lands and vowed to go beyond simple words when it comes to justice for Indigenous communities.

“Respect [towards Indigenous groups] is not simply paid in terms of words, it is paid through actions,” Saini said. “I think we start by building a culture where [inclusion is a] part of the natural ethos of the university rather than part of just simply our policies and legislations.”

He said that while he is aware of the Mohawk Mothers’ legal case against McGill, he has yet to inform himself enough to offer his own opinion.

Saini shared that during his term at Dalhousie, which is located on Mi’kmaq territory, he launched the Indigenous Student Access Pathway (ISAP). The program helps Indigenous students who would not otherwise be eligible for admissions under Dalhousie’s high school prerequisites transition to the university.

When asked about his previous term at Dalhousie, during which the Dalhousie Gazette reported that tuition fees for international students increased substantially, Saini responded that he has no intention of raising McGill’s tuition. He stated that the Dalhousie tuition fee increase stemmed from the university having the lowest fees of all Nova Scotian universities, with some Dalhousie programs charging 50 per cent less than competing institutions. According to Saini, Dalhousie raised tuition in a way that did not impact existing students’ fees whilst simultaneously maintaining a high quality of education.

“I see absolutely no reason to do anything like that because McGill’s tuition is very much in line with the tuition in comparable universities,” Saini said. “I’m not a tuitionincrease happy principal or president. That’s not what drives me.”

In a written statement to The Tribune, Law Senator Josh Werber stressed that while student senators are aware of the tuition hikes

at Dalhousie, as well as Saini’s reputation of tense relations with unions, students should not dismiss creating a working relationship with Saini.

“Undeniably, reports of union opposition and tuition hikes are concerning,” Werber wrote. “The Principal at times has limited direct influence on such decisions, so I hesitate to assign responsibility to him personally without more information. Instead, [the Students’ Society of McGill University] will focus on working constructively with Mr. Saini going forward.”

Saini says that working with unions begins with a good-faith relationship between employees and university officials. To further improve the student experience and union relationships with the administration, Saini feels that he needs to understand the campus atmosphere, which he intends to do by introducing new communication channels so that students feel comfortable approaching McGill administrators.

“Nobody should be intimidated about approaching anybody in the university,” Saini said. “We should have open dialogue for everything. That doesn’t mean we’ll always agree, that doesn’t mean we will always find solutions to everything, but that means that we will talk openly and frankly.”

About to begin a new chapter of its history under a new name, The Tribune delves into the paper’s history and explains the inner workings of the writing, editing, and publishing process.

The Tribune was founded in 1981 as a student-run newspaper that became editorially independent in 2011, when the Société de Publication de la Tribune (SPT) was formed, separating the publication from the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU). It has seven written sections—News, Opinion, Arts and Entertainment, Features, Student Life, Sports, and Science and Technology— and publishes roughly 25 articles per week. The Tribune currently has 29 paid employees, including Section Editors, Design Editors, a Copy Editor, a Social Media Editor, a Creative Director, Managing Editors, and the Editorin-Chief (EIC). Each semester, The Tribune also hires Staff Writers and Creatives, which are unpaid volunteer positions.

The Board of Directors (BoD) governs

the SPT and is responsible for hiring the EIC, approving the annual budget, and convening Annual General Meetings in the winter semester, among other things. Excluding those in the School of Continuing Studies and those at Macdonald campus, all undergraduate students are automatically members of the SPT and may attend any open BoD meetings.

Editions of the paper are distributed in 65 locations across campus, the most popular being the front entrance of the McLennan Library.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, The Tribune distributed 5,000 physical copies on campus per week, while online readership boasted an average of 70,000 views. In 2023, circulation was lowered to 2,000, and its online readership dipped, with an average of 60,000 hits per week.

Twice a year at the end of each semester, The Tribune releases a special, themed issue. These are typically 24 pages—compared to the usual 16—and may include additional creative content, as well as a highlights section with shout-outs to some of the most significant pieces published throughout the semester.

What does a typical week look like for writers and editors?

The process begins on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday evenings, when editors, staff, and contributors meet in suite 110 of the SSMU University Centre or over Zoom to discuss and pitch ideas for the upcoming issue. By mid-week, editors submit photo, illustration, and multimedia requests to the design team, who is responsible for ensuring that pieces have accompanying photographs or illustrations.

The Editorial Board meets every Friday evening to discuss various pitches presented by the Opinion Editors. After voting on which topic to editorialize on, editors engage in an open discussion for about two hours, which Opinion Editors then use to write an editorial that is published on Tuesday in the upcoming issue.

Articles by Staff Writers and contributors are due Friday night and undergo three rounds of edits over the weekend. On Sunday night and Monday morning, two editors from outside sections review the articles, a process called “set one.” The Managing Editor of each section then addresses set one edits, before the piece gets to the Copy Editor and

SSMU vice-president University Affairs

Kerry Yang was on the selection committee to hire Saini. Though his own term is coming to an end, Yang looks forward to creating a strong and productive relationship between Saini and SSMU.

“What we learned this year was that a strong collaborative relationship between McGill administration and students has allowed us to move forward on many different projects at speeds much quicker than usual,” Yang wrote to the Tribune. “I hope to be able to work with Principal Saini in a collaborative and diplomatic manner built upon mutual understanding and the commitment towards bettering the educational experience for all students.”

EIC by mid-morning on Monday. By the end of the night, Managing Editors and the EIC have done a final read-through of all of the articles, articles are scheduled to publish on the website, and the design team has created the final layout for the physical newspaper. A PDF is then sent to the publisher, Hebdo Litho, to be printed and distributed to newsstands across campus on Tuesday morning.

Where does The Tribune get its funding?

The Tribune is funded entirely by student fees via the SSMU and Post-Graduate Students’ Society (PGSS). Every semester, undergraduate students pay $4 in non-optoutable fees to support The Tribune, and this year, the sum paid by post-graduate students was increased from $0.87 to $1.50 per semester.

Today, the business team rarely receives requests for print advertisements in The Tribune In past decades, however, a substantial portion of the newspaper’s revenue was generated by ad placements. It was around 2010—when readership moved largely online—that ads began disappearing from the pages of the Tribune

Ghazal Azizi News Editor

Ghazal Azizi News Editor

Content Warning: Descriptions of medical abuse, physical abuse, andpsychological torture

Charles Tanny visited the Allan Memorial Institute, a research and psychiatric centre operated by McGill’s Royal Victoria Hospital, in August 1957. He was referred to the Allan after experiencing pain in his face, a condition his family doctor believed was psychosomatic—Charles suffered from trigeminal neuralgia, a neuropathic condition—rather than a psychological one.

Nearly seven decades later, Charles’s daughter, Julie Tanny, is now the lead plaintiff in a class action lawsuit against McGill, the Royal Victoria Hospital, the Canadian government, and the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Tanny, along with hundreds of other plaintiffs, alleges that the Allan conducted psychological experimentation on unconsenting patients between 1943 and 1964.

From 1957 to 1964, the CIA funded 89 institutions that researched mind control and brainwashing techniques in a project known as MK ULTRA. Subproject 68, one of 144, took place at the Allan under the supervision of psychiatry professor Donald Ewen Cameron. Tanny’s lawsuit alleges that the experiments started in 1943 when McGill hired Cameron as the founding director of the Allan, years before the CIA’s involvement.

Cameron, whose research focused on the causes of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, believed that mentally ill patients could be “depatterned” through prolonged comas, large doses of psychedelic drugs such as LSD, and extreme electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). After “depatterning”—which resulted in memory erasure, acute confusion, and/or losing bladder and bowel control—Cameron be-

lieved patients could be re-taught healthy behaviour through “psychic driving,” a process during which patients were sedated and subjected to tape recordings of a single sentence on repeat. Tanny, who obtained her father’s medical records in 1977, says her dad was put into an insulin coma and kept asleep for 23 out of 24 hours every day, while a background audio recording played endlessly. The content of the recording was not disclosed in his medical records.

“After the first months, he asked to see my mother, so they wrote in his file that he still had connections to his former life [...] so they put him back into treatment for another month,” Tanny told The Tribune. “After the second month, they said that it looked like this was as far as they could take him.”

Charles, Tanny’s father, was also subject to extreme ECT shocks, allegedly administered two to three times per day at 20 to 40 times the normal voltage at the Allan. Tanny says that when Charles returned from the Allan after two and half months of experiments, he had no recollection of his three children.

“My father was a very devoted father [....] Every weekend, he took us to Belmont Park, we went fishing, he built us a skating rink, very attached. And after the experiments, there was zero relationship. He was extremely detached, and that never changed,” Tanny said. “There’s one common thread with a lot of people who were depatterned: They came home quite physically violent and angry. And in my father’s case, he went from a very loving and gentle man to someone who used to hit me regularly.”

Lana Jean Ponting spent a month at the Allan in April 1958. She was admitted because of a court order her parents received after running away from her house at 15 years old. Now 81, she remembers her time at the Allan vividly.

“When I got to the Allan, it was a scary-looking building,” Ponting said in an interview with The Tribune. “When I went in there, I noticed a strange chemical smell. Dr. Cameron assured my parents that he would take care of me. I remember going to sit in Dr. Cameron’s office, he took me to a room where I had one pillow, a mattress, and a blanket. He told me to stay in the room. The nurse came in with a pole and a bag with something in it. She told me to lie down and she put a needle in my arm. I felt funny. And so it began.”

Ponting, who has been on medication since the experiments to offset the side effects, suffers from flashbacks and never spoke of her time at the Allan with

anyone, not even her husband. She only recently uncovered that she was a victim of the experiments after her brother noticed an ad about the class action lawsuit in The Montreal Gazette

Since piecing together her memories of the Allan with her newfound knowledge of the experiments, Ponting has testified in the Kanien’kehà:ka Kahnistensera (Mohawk Mothers)’s ongoing lawsuit against McGill. The Mothers suspect the university’s New Vic site, formerly the Royal Victoria Hospital, holds unmarked Indigenous graves. In an affidavit that was enclosed with a note from her doctor attesting that she is of sound mind and body, Ponting says she saw digging at night as a patient.

“I would sneak out of the Allan at night when I could. I actually saw people with shovels. I could see them because their lights were so bright. And I noticed that [the shovels] had red handles, I will never forget the red handles,” Ponting said.

While most of the plaintiffs are the relatives of victims, Ponting is one of the few living child survivors.

“I’m hoping this lawsuit can bring to the attention of the Canadian people what we suffered,” Ponting said. “I consider what all of us went through as a journey into madness [....] I’m not doing this for myself. I’m doing this for all of the people that have suffered without knowing through the Allan.”

While the class action was filed in 2019, it has yet to be certified—the process through which a lawsuit is approved by a court before proceeding to trial. In March 2021, the United States Attorney General filed a motion to be dismissed as a defendant, claiming it had immunity from lawsuits in Canada at the time of the alleged experiments. The motion was heard and later won in 2022. The plaintiffs have since filed an appeal, which was heard at the Quebec Court of Appeals on March 30, 2023.

Jeff Orenstein, the plaintiffs’ lawyer, says the State Immunity Act, which determines how foreign states can be sued in Canada, is retrospective and can apply to cases before the Act was passed. Orenstein argues that when Canada drafted the Act, it took direction from similar documents in Europe, the U.K., and the U.S. While the British and European documents clearly indicate that their immunity acts are

not retroactive, both the American and Canadian immunity acts do not establish whether they apply to instances prior to the policies’ adoptions. Orenstein sees the lack of a specific retrospectivity clause in the Act as an intentional choice.

“Anyone who was a Canadian who was injured on Canadian soil for personal injury has jurisdiction in Canada, without a doubt. And so, if the Act applies, there’s not much else to decide. Clearly, we have jurisdiction in Quebec,” Orenstein told the Tribune. “If Canada didn’t recopy [the retrospectivity clause], they obviously intended it to apply to things that happened in the past.”

As Tanny and Orenstein await an appeals decision from the judges, they are optimistic that they will win based on the questions the judges asked during the March 30 hearing.

“The judges seemed to be quite interested in the retrospectivity debate,” Orenstein said. “It is a serious question that I think will take them some time to work through [....] They’re going to want to take their time to really write a very serious, reasoned judgement, knowing that it might end up in front of nine judges in Ottawa [at the Supreme Court].”

After the U.S.’s status as a defendant is decided, the remaining defendants, including McGill, will have to present their defences for the class action to be certified, a process that Orenstein estimates could take years.

In a statement to Global News in 2019, the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC), which was born from the merger of the Royal Victoria Hospital with four other hospitals in the city, recognized Cameron’s experiments but denied responsibility, claiming that Cameron acted independently and was not an official MUHC employee. The plaintiffs amended their application to list McGill as a defendant instead of the MUHC. The Tribune contacted McGill in light of its involvement in the lawsuit, but was referred to the MUHC, who declined to comment, citing the ongoing nature of the suit.

McGill is known for its efforts to ensure accessibility, but one key component, and arguably the most important, is being overlooked: Car accessibility on campus. While being in the heart of Montreal might not be conducive to such an intricate road system, it’s positively too much to ask students to walk all the way from Otto Maass to Leacock.

Budapest, Paris, and Munich, while beautiful, lack one important thing: Motorways everywhere. For this exact reason, McGill should follow the likes of Kansas City and Dallas in their emphasis on motorways per capita. McGill must create more roadways on campus for faster access to buildings and increased efficiency—students would be able to get their work done much faster if they didn’t have to walk everywhere.

Montreal is known for not being car-friendly, whether that be because the roads are, to say the least, subpar, or because of

the interconnected nature of the city. Yet, a car not only gives you more personal space than public transportation, but it is also much quicker than walking from place to place, especially during peak hours. Everyone should have the ability to drive through the cobblestone streets of Old Port as opposed to walking through it. There’s no need to admire the picturesque buildings of the surrounding area or to window-shop and peruse their merchandise. Instead, you need to focus on getting to your destination as quickly as possible.

Parking garages are beautiful. Anyone who opposes them simply cannot appreciate the brutalist architectural style. The Old Port is without a doubt a nice part of Montreal, but a five-story parking garage would only bring a modern flair to such an outdated area. Any opportunity for a garage would increase tourism—bringing much-needed traffic to the streets and creating a festive atmosphere.

Why, then, should McGill adopt roadways? Simply for increased maneuverability across campus. The Redpath Museum

might be architecturally aesthetic, but it feels incomplete without a parking lot. Traditionalists will ask where the parking lot will go. My response? It should be built on Lower Field. All that space is not being used optimally, especially when taken up with an ice rink during the winter. But a parking lot could finally put all that green space to use and considerably boost the attractiveness of the university, in turn increasing McGill’s revenue.Instead of a skating rink, the McGill community could rejoice in slipping and sliding across a parking lot and avoiding near death.

Oftentimes, students have back-to-back classes, requiring quick transportation in a gas-guzzling machine. Having a roadway cutting directly through campus would remedy this. Purists will point to the inconvenience of having to wait to cross a street in the middle of campus, but this would, in fact, help students reflect on the simple moments in life and appreciate the time they have at their drivable university.

McTavish, in particular,

should be open to vehicular transportation. McGill students are tired of walking up the hill from Sherbrooke to Stewart Bio, and allowing vehicles would ultimately make students more productive, and boost their GPAs. And to ensure that no student is hit by a car, pedestrians would obviously be forbidden from McTavish. If this causes an unjustified uproar among conservative students, establishing one crosswalk on McTavish to cross at their own risk should suffice.

It’s time for Montreal and

I don’t know how it started. I have often wondered to what extent my gravitation toward men’s clothing was simply a case of internalized misogyny. I must have seen the bright pink colour my parents had naively painted my childhood bedroom, soaked in the gender narratives my grandparents, my cartoons, and my toys produced. I took one look and said “nope.”

You can see the shift in my family photos: Sitting peacefully in a white dress in a mall-photo-studio seashell at age two transformed to shorts and a polo at age three, tuxedo and Converse at age five.

At some level, there were a couple of happy years spent in that tux, where I didn’t worry about my body or my hair, about the complexities of gender expression in modern America, or what people must have thought of me when I wore that clip-on necktie to kindergarten.

front: For the rest of the year, I could play Minecraft and try not to think about it too deeply, but on shopping days, I confronted the gendered adult world head-on. And so I chose the most nondescript pants I could find. I shopped in the school uniform section of the store, going plain and simple and sticking to the default—of course, meaning male.

Gradually, patterned clothes disappeared from my closet, swimsuits were off the table, and by middle school, only the black pants and button-downs remained.

Somehow, I had transformed my gender confusion into a presentation of stubbornness and rigidity. Classmates, teachers, and friends asked me how I could cope with the tedium of wearing the same thing every day. I said that it just worked for me. I did not tell them that it was too stressful to imagine doing anything else.

McGill to stop reinforcing archaic notions of tradition such as pedestrians and public transit. The age of progress is here, and we must allow cars to have immediate access everywhere. If McGill doesn’t sanction this modernization, then students are likely to tire themselves out before they even get to lectures, and this will lead UofT to finally dominate the rankings. When Montreal starts banning pedestrians in areas such as Old Port, McGill could follow and look less like a university and more like a highway.

At the beginning of the fall semester, I went thrifting. Alone.

I spent a couple of hours walking through aisles, paging through shirts and sweaters before deciding on three button-down shirts: One plaid, one polka-dot, one gingham. They were the first patterned shirts that I’ve owned since the first grade.

But as I got older, instances of gendered expectation began to intrude into my childhood mind. The pink underwear. The American flag bikini offered to me one Fourth of July. Even the suggestion of a heart-shaped sticker on the cover of my English notebook.

Shopping was always the moment which brought this conflict to the fore-

Gym class began to unravel this precarious system of dressing. While the clothing policy was flexibly enforced, I quickly discovered that you got 20 per cent off of your grade for wearing a button-down during volleyball. I sheepishly approached my mom after school: We needed to go to the store and buy a T-shirt.

So, standing there, last pick for the

dodgeball team, I showed my arms in public for the very first time.

And yet, after my 45 minutes of dodgeball were over, I realized I had stumbled upon an opportunity. I left my button-down unbuttoned on top of that gym T-shirt on my way to geometry class. I didn’t die. I felt ashamed of how small a step this was, and how big of a step it felt like.

I began to push the boundaries in ways that felt too feeble to admit to people at the time. The next summer, I bought a pair of jeans. This year, a patterned shirt.

I realize now that the problem was not that I was stubborn, or inflexible, or any of the things I thought I was during that gym class. It was that I was unhappy. I don’t know if I’ll ever get to a place where I feel comfortable enough to wear a dress, but I don’t know if I care, either.

What I do know is that walking around in my polka-dotted shirt, a pair of Converse, and the occasional hoodie, I feel more at peace than I did as that kid in that uniform.

I still put off shopping for as long as I can. But I did go thrifting again last Saturday, and I added a pink sweater to the rotation.

Montreal has the second highest levels of traffic across all Canadian cities, in terms of hours lost. (iHeartRadio)

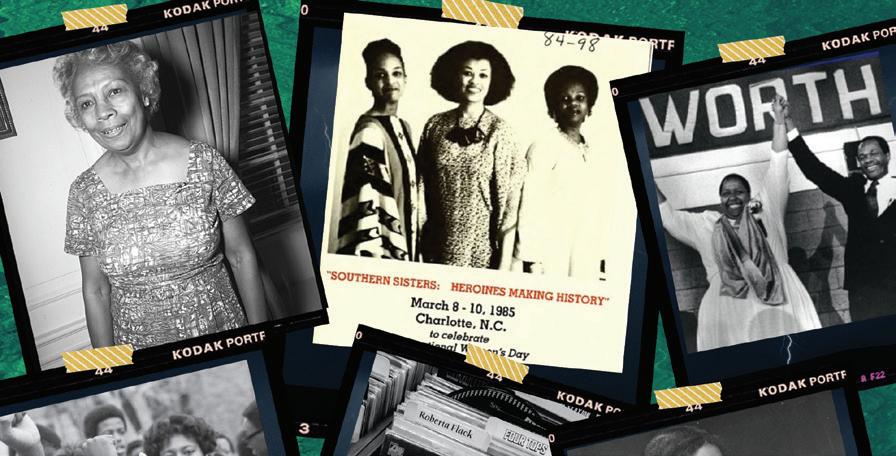

Last semester, I started working in the Black Students’ Network (BSN) archive as part of my elected responsibilities in our political portfolio. In our small office nestled in the University Centre, I sat in front of hundreds of books, an aging MacBook on my lap, going through each page one by one. With the sweetness of future critical consciousness hanging over my brain, my tongue tickled with the words we must find. Immersed in this library, lingering with the tender notes, the writings bristling with weapons, the pulses and rhythms of the collective my predecessors remembered to keep close would be the only way forward.

The dust speckled off of a collection of Alice Walker’s poetry dedicated to her mentor Muriel Rukeyser. To be at Sarah Lawrence with them. How do we make legible our collaboration? The spines of Dudley Randall and Henry Dumas’ collected works winced under my categorizing caress. We never speak of the informal methods of canonization. I read lines from each aloud, militancy and beauty rustle together in this melody. Archival weight hangs on the Black writer–– we will forget you ––as the Black reader wanders for recuperation, crouching below legacies that loom, tangled at the roots to be rhizomatic.

My work goes abroad. Countless tomes, past and present, devoted to the ruthless destruction of apartheid in South Africa, sociological excavations, multilingual prose-poems for freedom, memoirs that documented the violence, stared back at me as I parsed through them. Eyes that bite. The hairs on the back of my neck stand as moments of both being and radical remembering haunt this government building—freeze the air. Sitting in the cold nothingness of quiet, I ask myself: Who do I institutionalize? What forms can liberation take for us all?

The list grows on a desultory Google Sheet. Stories turn into numbers, columns make containers for our meaning-making. After a few days’ work, I read back the riches. The ledger, the possessions, the objects at my disposal. Black life, Black livelihood, Black livingness rendered into a familiarly brutal mathematics whose hold grips the nimble, wayward poetics of new creative and collective worlds. I struggle to speak the language of this archival practice. This translation transforms an ethics. The lives we save can’t reproduce, the technologies that justified the lives we’ve lost. But, in being in the archive, extraction seen for its exploitative guise, we can propel libraries for us, writing fruitfully the future we must work toward together.

At the age of 11, a Facebook account became the portal into the rest of my young life. Somewhere between the mourning cries of MySpace and the over-filtered Instagram era, I uploaded my first photo and thus began my personal, digital archive. A profile, a full name (naïvely), some likes, and a network: A person, created.

No digital trace of me exists before this age—I was coddled, grandfathered in by a generation so attached to physical mementos. VHS tapes, CDROMs, polaroids faded into obsolescence. Looking back now, I can’t pinpoint when the prospect of an online presence stopped being the riveting unknown and morphed into an extension of myself. High school dances, memes, birthday posts, acne and awkwardness, a political consciousness, all preserved on a timeline scroll, under the deceptive, out of a “Delete” button.

The insidiousness of the digital archive reveals itself as we age. At a certain point, you decide to lean in or lean out. I ask the perennial question: When does surveillance stop being a privilege? When employers crawl Instagram tagged photos to find a drop of liquor? Or when the government rejects a passport application because of a reposted political statement? In the metaverse, digital borders are just as violent.

Of course, a digital archive holds so much good, too: The kind that our tired, melting brains cannot recall. People we loved, pets we adored, songs we had on repeat, and articles we authored combine to form the breadcrumb trail of a life. But it’s a double-edged sword: Playlists become elegies, laughter becomes screenshots, and frozen, photographed smiles haunt you forever. Some things you can never take back.

If we have children someday, their archive will begin in the womb. How do we reject cyborg motherhood from within the matrix? I’ll put the ultrasound on my close friends story, but not on my main. Or nowhere at all. Life’s accomplishments deserve to be recorded, but the question of where has serious ramifications. Like it or not, digital archives are digital legacies—pixellated and permanent.

The more of ourselves we stamp into the digital ether, the clearer the truth becomes: Originality still exists, but privacy is dead.

My new favourite study spot is the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ). It’s nice to get off campus and be immersed in the city. Spending time at BAnQ has made me think, as we reach the end of the semester, that it’s worth looking back on the year and considering how we’d like to spend the next one.

Our brief time at McGill is precious: It’s a time of learning, development, and the creation of our character. The people we meet and the things we do here will have a significant impact on our lives to come. All the choices we make here—to study biology, to learn a new language, to live with friends— will affect everything that comes after. These few university years are crucial; our memories of them will inform the rest of our lives.

This is why I fear that too many of us will finish our degrees simply as McGill students and not as Montrealers. There’s an entire city around us—a city of culture, beauty, and wonder—yet many of us remain in the McGill bubble because it’s socially convenient. It’s much easier to make friends with others in our classes and residences, but it is much more difficult to branch out into the unknown. And as busy students, we often reserve our non-studying hours for sleeping and partying, making it difficult to dedicate time to exploring Montreal. But if we want our few years here to expose us to new lives and opportunities, then we must step beyond Roddick Gates. Take the metro far away, strike up conversation at the farmers market, café, or bookstore. Make that extra scary step to meet someone new. What’s the worst that could happen?

This brings me back to BAnQ. The impressive library is found in the Quartier des Spectacles, near UQÀM. It’s worth a visit simply for its architecture: Sleek glass panels and wooden walls lend the interior a striking yet peaceful ambience. People study quietly, write, and read at desks flooded in light by the immense windows. From high up on the fourth floor balcony, there’s a view of the entire library. It’s an impressive space that puts McLennan and Redpath to shame.

So, here’s an easy way to step out of the McGill bubble: Spice up your routine, and make a short trip to the Grande Bibliothèque to study, not as a McGillian, but as a Montrealer. Maybe you’ll meet someone at the café on the ground floor of the library and make a new friend; maybe you’ll chat quietly with someone reading a favourite book of yours; maybe you’ll get the cute librarian’s number. It’s worth joining the larger Montreal community that McGill is only a small part of.

Over 800,000 Quebecers are currently looking for a new primary care physician in their area. Wait times to find one can extend to more than two years in Montreal, where the population faces one of the worst health-care accessibility crises in the country. This issue directly results from Quebec’s poor commitment to creating a safe, inclusive, and anti-oppressive workplace in the health sector. The province needs to address the institutional racism plaguing its healthcare sector and foster a space where health professionals can focus on their work without being exploited or oppressed.

Instead of dedicating themselves to mitigating high patient demand, doctors in Quebec are required to spend around 40 per cent of their time working shifts in short-staffed hospitals and nursing homes. The requirement was introduced in 1990 amid considerable nursing staff shortages in the public sector. Over the past 30 years, this staffing crisis has only

worsened and hit a fever pitch during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the public sector saw roughly 4,000 nurses step away due to burnout and inadequate pay.

Beyond this, physicians spend between 15 and 20 per cent of their time on unnecessary paperwork to reconfirm the statuses of already injured or disabled patients. Cutting this number by any margin would dramatically increase the time doctors have to see patients.

The government must support nurses with better compensation and management. Without this essential step, dissatisfied physicians in the public sector will keep quitting and moving to private practices, a shift that the provincial and federal governments have implicitly and explicitly encouraged.

Past policy decisions in Quebec also played a part in fostering the current health-care crisis. Caps on medical school enrollment in the 1990s due to low population growth and cost-cutting efforts by former Premier Lucien Bouchard resulted in upwards of 500 doctors taking buyouts or retiring, many of whom would still be in practice

Alex

SherContributor

Originally conceived out of its founders’ struggles to pay their exorbitant San Francisco rent, Airbnb has become the very thing it had hoped to rectify. Driving rent increases and housing displacement, Airbnb exports risk, shirks responsibility, and generates massive profit.

On March 16, a fire in a historic building in Montreal’s Old Port claimed the lives of seven people. In the weeks following the fire, reports revealed that six out of the seven people who died

today.

The false austerity outlined above is only compounded by the institutional racism within the health-care sector. In 2022, a McGill University Health Centre study on racism found that both employees and patients of colour have been subject to shared experiences such as racist verbal harassment and microaggressions.

The first of its kind in Canada, the report also offered an empirical argument against Premier Legault’s false assertions that there is no systemic racism in Quebec.

Health care is not a safe space, especially for Black and Indigenous health-care workers and women of colour in particular. Black nurses in Quebec are regularly turned away by patients while also experiencing considerable difficulties finding employment in the first place. Racist and sexist discrimination is explicitly manifested, as evidenced by a 2021 job posting from the Saint-Eustache Hospital requesting that only white women apply.

The treatment of Indigenous patients also fosters a dangerous and oppressive environment,

Based on Public Health Data from 2000-2020, only 33 to 39 per cent of general practitioners in Quebec claim the bulk of their billings from family medicine. (Graham Hughes / The Canadian Press)

turning away any possible Indigenous nurses, especially those trained in traditional wellness and healing that the province does not consider scientifically sound. The story of Joyce Echaquan, an Atikamekw woman who livestreamed her nurses insulting and degrading her as she died, reflects how hateful cultures of exclusion in the health-care system determine who deserves to be “saved.” In response, the province announced in 2021 a $15 million plan to implement diversity training for employees. But the National Assembly has failed to advance motions toward equitable access to health care such as Joyce’s Principle, a document demanding

were staying in illegal Airbnbs.

The owner of the building, Emile Benamor, told the CBC that the building was up to code. Yet, multiple reviews left on the nowdeleted Airbnb listings reference the absence of windows, amongst other safety concerns. Airbnb property owners don’t need to show proof that they have functioning smoke and carbon monoxide detectors for their listings to be approved by the host company. Unlike hotels, fire exits, smoke detectors, and sprinkler systems are not mandatory. Instead, Airbnb simply urges owners to install and maintain these safety necessities,

knowing some will cut corners— but is perfectly willing to accept that reality as it translates to more overall units and fewer funds dedicated to oversight. The human cost of unregulated Airbnbs is immeasurable.Quebecois photographer and filmmaker Camille Maheux was among those killed in the fire. She had lived in the apartment for over 30 years and survived multiple attempts at illegal eviction. Throughout her career, the 76-year-old photographed the women’s movement and LGBTQIA+ communities—but the archive of her life’s work perished alongside her. Friends from France, Spain, Italy, and Brazil are trying to reassemble the bits and pieces of Maheux’s work the fire didn’t claim. Google her photographs now—they prove quite difficult to find.

In Montreal, over 90 per cent of Airbnbs are unauthorized, rendering fire regulations a nuisance rather than a necessity for landlords. Current Montreal laws stipulate that Airbnb and other short-term rentals (STRs) can

only be located on selected strips of the city and must register with the provincial government. However, regulation and enforcement of these policies have been both absent and ineffectual.

An Airbnb spokesperson said that the company will launch a registration field requiring all new listings to provide a permit number. Yet, the lives lost in the Old Port fire illustrate that this introduction of laws is too little, too late. And this has been a staple of Airbnb regulation, which only banned open-invite party listings after a fatal shooting in Pittsburgh. This reactive response to known risks has allowed Airbnb to profit and only address safety concerns after a tragedy forces them to.

While the impact of Airbnb and other short-term rentals has been felt globally, Montreal has experienced particularly devastating effects on its housing market, where the search for affordable housing has become increasingly difficult. Airbnb and other STRs can be far more profitable than long-term rentals, which, in the absence of regulation, creates an economic incentive for

that Indigenous people gain access to all health-care and social services free of discrimination.

By listening to nurses on the ground such as Yvonne Sam, the province must sanction the racist barriers of access to health care and invest in anti-oppressive medical school education. In order to address the systemic racism that pervades Quebec’s health-care system, the government must first recognize it. If the government cannot offer solutions to a health-care system as racist, overworked, and fundamentally flawed as Quebec’s, the road to care and recovery for workers and patients alike will be paved with peril.

landlords to turn units into STRs. Oftentimes, this transition leads to harassment at the hands of landlords and the forcing out of long-term tenants, as was the case with Benamor.

A study conducted in 2017 estimated that 14,000 additional homes would be available for long-term residence across Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver if they weren’t currently rented as Airbnbs. STRs raise the price of the long-term units that do stay on the market, as people are increasingly willing to buy properties with the intention of renting them out at a profit. Those not personally interested in renting a part of their home are in direct competition with those who are. The existence of a robust STR industry thus takes houses off the market and raises the price of those houses that remain.

It’s time for Airbnb to put the safety and life of its tenants before profits. The Old Port tragedy is a lesson for both the company and the city of Montreal, which must immediately increase and enforce the regulations for short-term rentals.

ABSTRACT

Scientific publishing has become a ruthless game. The infamous aphorism of “publish or perish” describes the pressure academics feel to publish their research extensively and stay relevant within their field. This problem manifests and is tied to a host of other disparities of accessibility within the science research field. Because of this culture, academics may be inspired to cut corners in their research to keep up with the increasing demand of being a scientist. So how can science be restructured from the decades of problems that plague it so that it can achieve equity and address systemic issues? How can one enter the system when it is stricken with socioeconomic barriers and structural racism? Scientists today are saying that science has become too unwieldy, and yet despite seeing the treacherous track of this road, many academics can do nothing but traipse along the same path.

The term philosophy can be linked back to Ancient Greece as the combination of the words philein and sophia, meaning “lover of knowledge.” Instead of the Lyceum, however, the lovers of knowledge of today now instead present their findings to a myriad of journals, like Nature or PLOS

Like ancient philosophers, I have also fallen in love with knowledge and the process of building upon my predecessors’ works. But conducting research as an undergraduate student can come with its own costs. Undergraduate student researchers hold a special place inside a lab. Compared to their graduate counterparts, undergraduates are rarely doing this work to further their own research inquiries. More often, they are seeking to become a competitive applicant for graduate school or to obtain a recommendation letter from the lab’s principal investigator (PI).

Q*, U2 Science and student researcher, says that undergraduates’ position in a lab can make them susceptible to exploitation from lead researchers. “So a lot of students, just to gain some level of experience, start to reach out to labs and are desperate for any kind of experience in lab work at all,” Q told me. “And that allows for some very exploitable undergraduates because they are not looking for pay [...] they’re just looking for some level of experience.”

Q believes that “publish or perish” culture can distill students’ passion for scientific research early on. The lack of research opportunities available for undergraduates pushes them to get involved not out of genuine interest, but to become more marketable to future recruiters.

“Many undergrads are just forced into these situations where they are working on a project that they have no interest in, where their only goal is to get a publication [...] before they can apply for grad school, ” Q said. The pressure to publish makes it difficult for academics to balance their personal life with their work. For Q, this endless chase of achievement often feels pointless.

“It’s not even like having a publication really guarantees you anything given how competitive academia is and how much importance is placed on grades [...] even if you’re an excellent researcher, you might get cut off for having a lower GPA,” Q said. “In this context, why research a subject that you want [or] is useful if there’s no return on your time investment?”

“Publish or perish” favours not only quantity, but novelty. Journals’ biases toward new and exciting findings has contributed to the decades-long “reproducibility crisis” that looms over many branches of scientific research. The crisis was first brought into the limelight in 2005, when John Ioannidis, a professor of medicine at Stanford University, published a paper arguing that most published research findings are false.

Eduardo Franco, a McGill professor in the Departments of Oncology and Epidemiology & Biostatistics, introduced me to Ioannidis’ findings and explained that there is a severe dearth of corroboration for old scientific findings—there is no “second place” in scientific discovery, after all. But if there is no one to check previous research, then science is founded on unsteady ground.

“So, let’s say I’m the editor of a journal and that someone submits a ‘me too’ kind of paper—a ‘me too’ kind of paper in the sense that they’re just replicating something that’s not particularly novel,” Franco said. “It’s a minor gain in knowledge, just a confirmation of something that has already been published. As an editor, sorry, I’m more interested in publishing things that are major gains in knowledge—big, new discoveries.”

Franco explained that the public can act as whistleblowers to keep academics accountable. Pubpeer, for instance, is a website that allows users to fact-check and highlight shortcomings in scientific publications. But peer reviewers ultimately bear the most responsibility for keeping papers accurate.

“Who’s the best judge of what I do? Someone like me, who’s sitting in a different institution, who doesn’t have a conflict of interest, and who’s an expert in the things that I do,” Franco said. “The peer reviewer, who understands what I do and would judge my work, sends anonymous feedback to me via a journal, and then I’ll be able [to say], ‘Hey, that’s right, I missed that thing. I should do that better.’”

Since the peer review process can feel never-ending, some scientists are tempted to take shortcuts to claim their first-place prize. Preprint archives, which are scientific manuscripts posted on a public server prior to formal peer review, allow academics to speed up the “publication” process. Franco explained that this is how many scientific discoveries regarding COVID-19 came about. Circumventing the traditional publishing system accelerated mRNA vaccine research, but when scientific findings are not subject to peer revision, it can also lead to disastrous consequences.

“All those [anti-vaccine people] out there who have a bone to pick about vaccines, they start [falsifying data] and putting them in preprints,” Franco told me. “Archives of preprints are a great idea because they prevent the distortion that the world of science was doing with journals, but at the same time, they open up an outlet for people who have a crazy thing to say about anything.”

Though the reproducibility crisis is alarming, Shashika Bandara, a PhD student in global health policy at McGill, warned against simplifying this complex topic into a dichotomy where publishing a lot is framed as bad and publishing less as good. From another perspective, a high annual rate of publications is a sign of increasing innovative scientific discovery. It only becomes an issue when scientists forsake the rigour that should be involved in the research process to publish for publication’s sake.

“I don’t think the fact that we are publishing more is a problem because I think science, as we go on, we need to do more research—we need to generate knowledge, and that knowledge may not be used right away,” Bandara said. “A paper that you wrote about something, even a model of equity or even how a protein works in the cells, can be used years later to develop a vaccine, perhaps, so there is use to doing research.”

The systemic issues plaguing scientific advancement took root long before “publish or perish” was conceived. Bandara told me that the plague of science’s colonial roots still persists.

“[Scientific research] used to focus on what diseases are in the colonized countries that would affect the colonizer,” Bandara explained. “And to an extent, it’s still moving forward and a lot of the medical research is being built on a colonial model.”

The knowledge that is considered important and funded by academia is dictated by the agendas and priorities of high-income countries, symptomatic of the “foreign gaze” that dominates academic settings: Authors from high-income countries form the principal authority on the problems of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

“So, we have neglected tropical diseases. We have to ask the question, who is neglecting these tropical diseases? Why are these tropical diseases neglected? Why is there so little research that we have to call them ‘neglected,’ right?” Bandara asked. “All of the time, these neglected diseases exist in [LMICs], and they do not affect high-income countries [....] If you take COVID-19, there is a push to find vaccines, there’s a push to do more research. There’s an influx of funding and publishing and so on and so forth.”

The disparity between these countries manifests in the nascent stages of the research process. LMICs have limited academic resources, resulting in delayed experiments and prolonged research periods, which impacts the quality of their research output. For instance, a reagent that can be delivered within a couple of days in Canada could take weeks to arrive at a lab in Bangladesh.

“The institutions, the universities do not have the funding, like McGill does, to subscribe to all these journals for everybody to access. So we don’t have this institutional access to journals that are mostly behind paywalls,” Bandara explained. “So a lot of the time, especially young researchers and even more advanced researchers, do not have the capacity or the ability to access these journals—the journal papers about their own country, even.”

To address access issues, Bandara suggested that journals should introduce open-access publishing to circumvent article processing charges (APCs), which are fees charged to authors for the publication of their work.

“So on the one hand, [LMIC] researchers cannot access journals because they don’t have the capacity [...] to pay these journals exorbitant amounts of money,” Bandara said. “On the other hand, they also don’t have the money to publish their pieces in these journals.”

But open-access publishing is not an antidote to LMICs funding limitations—only an anodyne. The “foreign gaze” extends to Nature’s open-access publishing, as they will charge researchers nearly $11,400 USD to read the academic papers they have for free, which can be greater than an LMIC researcher’s yearly salary. This is not unique to Nature, as many high-impact journals like The Lancet also require thousands of dollars just to access their articles for “free” under an open-access model. Because of this, LMIC scholars still often rely on resources such as SciHub, which provides free, unrestricted access to scientific works, to conduct their research. But even these platforms have their limitations—science’s colonial structures also mean that its institutions primarily operate in English, barring non-English speaking scientists from many scientific discussions.

To overcome these structural issues of access in academia, Bandara believes that those involved in scientific research must confront the colonial

system behind it.

“So some of these things providing waivers, also the open access articles, it’s going the right way, although it’s not the complete solution,” Bandara said. “It’s important to recognize the problem first, and then recognize how the foundation of science research and publishing in the first place is built on this model that sort of benefits high-income countries.”

The class barrier to involvement in academic research is apparent in our own university. Q told me that undergraduate researchers without access to financial support are denied many opportunities.

“[Student research] kind of raises this problem of equality because the only students that are actually able to do this kind of volunteer work are those that are rather well-off and who don’t really have to sacrifice some aspect of studies, or personal life, or financial security, and whatnot,” Q said. Of course, this lack of available funding opportunities disproportionately affects those of lower socioeconomic status, especially Black, Indigenous, and students of colour (BIPOC). If a student has to prioritize a second job or family care over research, they are already at a disadvantage compared to other students.

For Q, McGill’s BIPOC research awards are an example of how the lack of sufficient research funding in academia can adversely affect marginalized students. Although the award is intended to embolden racialized groups to go into research with a $7000+ summer stipend, Q argues otherwise.

“[The BIPOC award] does the exact opposite of what it’s trying to do, which is to encourage people of colour to do research,” Q explained.

“Yeah, well, it does encourage them, except we know full well that because people are always fighting for more awards and more money, a lot of the time, these people of colour are relegated to the BIPOC award, even though they are perfectly good to receive the NSERC or the SURA award.” Q believes that inequitable hiring decisions happen when PIs use BIPOC students to strategically optimize their finances. When faced with scholarship prospects, Q felt that he was sidelined compared to some of his peers. “Faculty members talk to one another, and they want to maximize the amount of funding they receive,” Q said. “So they say, ‘Well, this is a person of colour applying to the BIPOC award. Well, guess what? We’re going to give them the BIPOC award and reserve the NSERC for a white student that might not be as strong, but who at least has a chance of getting [an award], but has no chance of getting the BIPOC Award.’ So, that basically doubles the amount of money that they’re getting.”

Passion for scientific discovery is often cultivated when one’s eye is staring down a microscope or telescope, but perhaps our tools of observation should also scrutinize the problems within academia itself.

Scientific academia’s culture has become increasingly toxic, requiring contributors, especially young, low-income, and BIPOC researchers, to sacrifice a crucial part of themselves—the magic of science that drew them into the field in the first place. Scientific discovery has become a race, pushing many contestants to forgo key principles of accuracy and integrity. The utopian vision of science as an objective agent of the world has shown its foibles.

But that does not mean scientists should resign themselves to this fate. Four hundred years ago, everyone believed the Sun revolved around the Earth. There are still years ahead of us that will allow us to make scientific knowledge and research more accessible. Only then can scientific discovery truly flourish. Already, many within the field are critically examining its inequitable structures, such as the Decolonizing Global Health movement

Since the time of Isaac Newton and René Descartes, many scientists have said that science is too unwieldy. But the lovers of knowledge centuries, decades, and years ago, along with the ones reading this now, had and still have a hold on it.

*Name changed to preserve their anonymity.

In 1974, the first Black woman Random House editor gathered photographs, sheet music, advertisements, obituaries, patent applications, materials, art, and ephemera in a collection entitled The Black Book. These archives, anthologies, collages, and scrapbooks celebrated, bore witness to, and captured the spectacular and the quotidian of Black life in all its forms since the so-called United States founding, all in one. Of, by, and for us––two scripts run parallel, knowing their touch, their fraught point of intersection is tender, causing blood and ink to spill. How could this publishing house make legible histories, performances, and comings-into-being of Blackness without minstrelizing, over-disclosing, running foul of the secrets we’ve kept for ourselves across generations––shared in the quiet moments of collective grace?

I (once again) heard about Toni Morrison’s editorial pursuits in this endeavour in the Leacock Building, for a public talk. As one of few Black attendants, other than the speaker, my walk to the building passed the Arts Building’s steps. A gateway to the humanities that stands in front of the violent memorial to our namesake who slumbers peacefully, with no regard for his enslavement of Indigenous children and Black people. The haunt of our ancestors hangs in his wake, Black life, labour, aliveness, solidarity, at the place where margin erupts into the centre; for to be advertised is to be remembered. By work all things increase and grow.

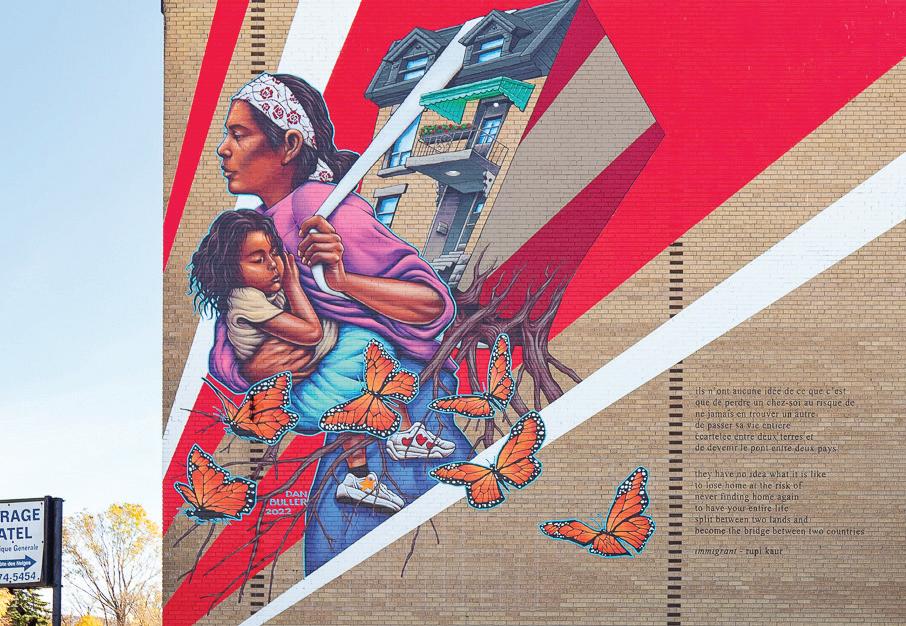

How do we commemorate lives and ourselves outside of the popular modes of redress, commissions, public

declarations; the plans, lists, records, books, numbers, and names made available? The Tribune sat down to articulate practices of counter-archives, archives that feel, that glint with golden futurity, that hold the muck and mess of the past and acknowledge the inaccessible dimensions of what we consider to be the standard archive.

Forging the ephemeral

When we think of archives, or extracting from archives, the image we construct are thick stacks, sign-up sheets manned by an agent with extraordinary discretionary power, silence, clubs that not all of us can join (they scattered the ashes and went). What would it be to say the informal archive might be loud, clamoured by voices chanting, singing, screaming, guiding, fostering, choking, or not always tied to the institution? Your memories matter because you studied at an international institution, shielded from the fall, and actively manufactured death.

Think about the amorous, nebulous glance from a potential lover, the nod from a comrade, the modes of social organizing and policing that attempt to strip Black and Indigenous people, women and queer and trans people of colour from spreading the unspeakable for revolution, the contact points that touch softly in times of peace and war. The photos, the laughs, the stillness of wandering in a time outside of the clock.

The art of losing’s not too hard to master. Write it! Scribble on the peripheries. Avoid the malconstructed public demands that impede your privacy. Our lives depend on the extraordinary within the ordinary practices of remembering, seeing, thinking, and living with each other differently.

Finding a meal simpler than a hot dog is a hard sell. It was The New York Times sports cartoonist Tad Dorgan who coined the term in the early 1900s. Now it’s a North American street food staple, with Nathan’s World Hot Dog Eating Contest taking place at Coney Island every July.

At McGill, the downtown hot dog stand is one of Montreal’s only street food vendors. The stand is also McGill’s unofficial weatherman.

Indeed, when temperatures rise above zero, and there’s no rain, a flimsy shade and fiery grill, accompanied by a wobbly table lined with dozens of ketchup and mustard

bottles, emerges at McGill’s Y-intersection— the telltale sign that summer is on the way. The middle-aged, lightly-stubbled, baseballcapped men running the stand are perhaps the most fair-weathered folks in Canada.

So, with the snow melting, the hot dog stand has returned, and last week, one of The Tribune’s Managing Editors, Mady, and I stopped by for lunch. The usual throngs of student droolers, thankfully, weren’t snaking the line—we went straight to the front.

Watching on, the stand felt like it had been taken from a 1980s postcard. The 40-something man under the shade ran a strict ship on the barbie, while the 60-something shorter man took payments. The idyllic simplicity twisted the arm of nostalgia and even made the tree-hugging hippies and the self-obsessed finance bros forget their identities.

The private is ripe with offerings to transform our public accounts of memory practice. Activist-author-organizer-researcher-librarian-abolitionist Mariame Kaba reminds us to move beyond carcerality and policing in the blooms only a library could gift us. We must navigate the violence that asks us to remember when our media circulates photographs of Black death and suffering, violence against refugees, Indigenous peoples, women, girls, and Two-Spirit people missing in the favour of white sentimental global uplift. No apologies without structural transformation should be accepted.

The question endures––what can the library, the more formal archive, build from this? Our communication, cryptic and coded, must work to a critical consciousness. Radical library practice means opening up doors, placing value on the democratic need to sit, to recover, to evade the seemingly insuperable burdens of in the cracks of underfunded social institutions. Sharing what we have, the books, the zines, the newspapers of eras gone by, the films, the music, and the tapes, in and outside national, provincial, and local libraries fuels what a better world could be. What it must start with, however, is reimagining the archive and its exclusive practices informally and otherwise.

Menu

Original - $5.50

Vegan - $5.50

Polish - $8.00

McGill’s hot dog cart has been around since 2012 and enjoys a lack of nearby competition, with Montreal’s strict rules restricting the number of street vendors to near nilch and McGill’s Food and Dining Services’ uninspiring mantra ruling with an iron fist.

The stand had three hot dog options, sufficient for a hot dog stand—this isn’t some European sausage delicacy house. They normally serve soft drinks, but on this occasion, they didn’t have any, and this included—to my utter apoplectic, incandescent rage—Diet Coke.