McGill’s leading ladies since 1911

Women’s History Month Special Issue

Published

The McGill Daily is located on unceded Kanien’kehá:ka territory

Statement about former SSMU President Darshan Daryanani on page 2

by The Daily Publications Society, a student society of McGill

Editorial 3

Women’s History Month

News 4

Women’s History Month and Ramadan

Battle of the Bands

Women’s History Month

Hunger Strikes

McGill Administration Salaries

Sci + Tech

Solar Eclipse Interview AI in Law

Culture 10

• Review of Hybird Condition

Review of Love Lies Bleeding

Review of Anatomy of a Fall

Review of The Meaning of Leaving

Statement about Former SSMU President Darshan Daryanani

In the Spring of 2023, the former President of the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU), Mr. Darshan Daryanani, initiated legal action against 19 defendants. According to the lawsuit, Daryanani is claiming damages for injury to his reputation, health, and earning potential, as a direct result of events that occurred during his presidency.

TheMcGillDaily and Abigail Popple have reached a settlement to the satisfaction of Daryanani. The parties agree that the settlement is to remain confidential and does not imply any admission of liability.

Daryanani believes that the resolution with The Daily is a positive step.

It is important that all actors in the student political process take into account fundamental principles of due process, procedural fairness and natural justice.

2 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily table of Contents

Table of ConTenTs

8

Sports 14 Queer Women and Climbing Commentary 15 Reflection on Womanhood Compendium! 16 •

By the Daily Publications Society

Darshan Daryanani’s Presidential Campaign Portrait

APRIL

ON

REGISTER ONLINE

30 5:30-8:30PM

ZOOM

3480 McTavish

107

phone 514.398.6790

fax 514.398.8318

mcgilldaily.com

The McGill Daily is located on unceded Kanien’kehá:ka territory coordinating editor

Olivia Shan managing editor

Catey Fifield news editors

Emma Bainbridge

Sena Ho

India Mosca commentary + compendium! editor

Gabriella Braia Gratton culture editor

Eliana Freelund features editor

Elaine Yang science + technology editor

Andrei Li sports editor

Vacant video editor

Magdalena Rebisz visuals editors

Eric Duivenvoorden

Genevieve Quinn copy editor

Vacant design + production editor

Vacant social media editor

Frida Morales Mora radio editor

Evelyn Logan cover design

Olivia Shan contributors

Emma Bainbridge, Jane Carli, Amelie Chiasson David, Catey Fifield, Arismita Ghosh, Sena Ho, Gemma Holland, Enid Kohler, Isabella Roberti, Parker Sherry, Elaine Yang

Across the world, the month of March has become synonymous with the progress of women’s rights. The US, UK, and Australia commemorate Women’s History Month in March (Canada celebrates it in October), and March 8 marks International Women’s Day, as designated by the United Nations. For its part, McGill University has utilized the month of March to showcase its accomplishments toward advancing women’s rights. This year, the university has taken the opportunity to celebrate its female deans, who lead ten of the institution’s 14 faculties. For three of these faculties, women are holding the position of dean for the first time ever.

This said, March is as much a celebration of women’s accomplishments as it is a time for reflection on the barriers, historical and present, that hinder efforts toward gender equality. While McGill focuses on celebrating its present accomplishments in women’s rights, the administration neglects to address its role in hindering gender equality efforts over the last two centuries, as well as the role McGill students and faculty have played in the victories of Canadian women.

Officially, McGill has minted itself a pioneer in championing gender equality in higher education. In the “About McGill” section of the university’s website, a featured article titled “Blazing trails: McGill’s women” recounts the history of female students at McGill. A bicentennial piece titled “Women admitted to McGill” touts McGill as the first Quebec university to admit women to its undergraduate body. On the “McGill Giving” page, the 2020 article “Did You Know? A timeline of women’s milestones at McGill” celebrates the fact that the university has “been shaped, challenged, and enriched by women through much of its history.”

It was in 1884, 63 years after the school was founded, that women were first allowed to study at McGill. The “Blazing trails” article frames 1884 as the inevitable result of the university’s liberal-minded administration and donors. Principal William Dawson, at a lecture for the Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association years prior, called the eventual admission of women “the dawn of a new education era.” It was thanks to a donation from businessman Donald Smith, later known as Lord Strathcona, that women would be allowed to attend the university, the first graduating class of whom were nicknamed the “Donaldas.”

of Smith’s endowment. Despite McGill’s supposed openness to gender equality, the Faculties of Law and Medicine were still barred to women. Furthermore, gender segregation fed into views among male students and faculty that women lacked the necessary mental fortitude to pursue higher education. This view was exemplified after Octavia Grace Ritchie, McGill’s first female valedictorian, delivered her graduation speech. Chancellor Richard Heneker of Bishop’s University asked her: “And are you not very tired?”

Some members of McGill’s faculty saw the university’s segregation policy as deeply harmful for women’s right to education. John Clark Murray, then-professor of philosophy and an advocate for co-education, publicly criticized McGill’s gender segregation policy and pushed for mixed-gender classrooms. Admission of women, to him, was just the first step toward achieving gender equality in higher education. For his comments, Murray was rebuked by Dawson, the supposed visionary in women’s rights, and “threatened with censure by McGill’s board of governors” who were afraid of jeopardizing Smith’s and other donors’ funding.

By 1889, women made up a third of McGill’s student body, and by 1917 outnumbered men in the Faculty of Arts. Nonetheless, the overturning of gender segregation would not be achieved for several decades. This decision came not as a moment of moral clarity from the McGill administration, but rather as a matter of practicality: the university did not have enough instructors to teach men and women separately. The outbreak of WWII and drafting of male students and faculty were what finally forced the university to establish a co-education system.

In the face of discrimination from McGill administration and government authorities, McGill students and faculty continued to push for women’s rights in Quebec and Canada. Octavia Grace Ritchie, previously mentioned as McGill’s first female valedictorian, was a notable suffragist and member of Montreal’s Local Council of Women. Idola St.-Jean, professor of French language at McGill, was one of the leaders of the Canadian Alliance for Women’s Vote in Quebec, and later, the first woman to run for federal office in Quebec. Women’s suffrage was achieved in Quebec on April 25, 1940, around the same time gender segregation at McGill was fully dissolved.

3480

All of these articles either omit or gloss over a crucial fact. Although female students were permitted admission, they were still segregated from men in their residences and classes. Royal Victoria College, which at that time included the Schulich School of Music, was constructed as a women’s residence and opened in 1899. The condition of women’s segregation, which McGill frames as an unfortunate but temporary circumstance, was actually a primary requirement

McGill, in only providing a partial account of its history with women’s rights, does a tremendous disservice to the struggles and sacrifices of previous generations of students and faculty who fought and continue to fight for gender equality. We, the editorial board of the Daily, believe it is crucial to learn about and preserve all facets of our history, to ensure that the injustices of yesterday do not repeat themselves tomorrow.

Volume 113 Issue 20

editorial board

St, Room

Montreal, QC, H3A 0E7

McTavish St, Room

Montreal, QC H3A 0E7 phone 514.398.690

107

& general manager Letty

ad layout & design

Coordinating NEWS COMMENTARY CULTURE FEATURES SCI+TECH coordinating@mcgilldaily.com news@mcgilldaily.com commentary@mcgilldaily.com culture@mcgilldaily.com features@mcgilldaily.com scitech@mcgilldaily.com CONTACT US Managing PHOTOs ILLUSTRATIONS radio COPY video + Social Media managing@mcgilldaily.com visuals@mcgilldaily.com visuals@mcgilldaily.com radio@dailypublication.org copy@mcgilldaily.com socialmedia@mcgilldaily.com The Origins of Women’s Rights at McGill All contents © 2024 Daily Publications Society. All rights reserved. The content of this newspaper is the responsibility of The McGill Daily and does not necessarily represent the views of McGill University. Products or companies advertised in this newspaper are not necessarily endorsed by Daily staff. Printed by Imprimerie Transcontinental Transmag. Anjou, Quebec. ISSN 1192-4608. EDITORIAL March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily Published by the Daily Publications Society, a student society of McGill University. The views and opinions expressed in the Daily are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of McGill University. The McGill Daily is not affiliated with McGill University. website Facebook Instagram twitter

us online! www.mcgilldaily.com

@mcgilldaily 3

fax 514.398.8318 advertising

Matteo

Alice Postovskiy

Read

www.facebook.com/themcgilldaily @mcgilldaily @themcgilldaily

Rethinking Ramadan

Exploring Women’s History Month amid tragedy in Palestine

Sena Ho News Editor

Muslims around the world are experiencing and witnessing a critical moment in history. March 10 to April 9 marks the month of Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, notably recognized for the practice of fasting. March also marks Women’s History Month, with International Women’s Day occurring on the 8th, offering a critical reflection about the impact of women’s voices and actions on the world. Ramadan represents a period of spiritual contemplation, exercised not only through fasting but through prayer and reflection. Each day Muslims are expected to fast from sunrise to sunset, culminating in iftar, otherwise known as the fast-breaking meal. Ramadan is a holiday designed to bring communities closer to one another, to embrace the joys in life, and keep negative thoughts at bay. However, amid global tensions, particularly with the worsening conditions in Gaza, many Muslims find it difficult to celebrate and embrace the holiday as they have in the past.

With regards to Islamic sentiment in the province of Quebec, there has been a history of discrimination from the government against citizens who display religious symbols through the implementation of Bill 21. This law prohibits people working in governmental positions such as lawyers, teachers, and police officers from wearing religious symbols, which has disproportionately affected Muslim women who wear hijabs. Although there have been countless challenges from civil liberty groups against this bill, it is still a governing piece of legislation within the province. Ramadan’s coinciding timeline with Women’s History Month more evidently displays the additional burden that Bill 21 places on many Muslim women. In Palestine, for example, the general lack of hygienic products available has made it increasingly difficult for women to access menstrual products. As a result, these women have resorted to other solutions such as creating their own pads or tampons from old clothing or taking pills to prevent their periods altogether. Thus, it is critical right now for women to have their voices amplified— discussing matters that not only apply to women generally but also about Muslim communities in Montreal and across the world.

In speaking with Muslim McGill students, they expressed their own

perspectives on the importance of allowing women’s voices to be particularly pertinent during this time. First year biochemistry major Lamija Mrndic found that, “it is important that Ramadan this year is happening during Women’s History Month, because I think that a lot of people have this perception about Islam that it is oppressive on women. But

I obviously completely disagree.”

Mrndic, who grew up in France, is accustomed to the aggression

Lena*, commented on the impact of Bill 21 directly: “I feel like Canada is a place where everyone comes together to accept each other’s differences, whether that be religion, values, family; and that bill is highly discriminatory. It is extremely disappointing to see a province in Canada conjure up something like that.” As a prospective political science major, her interest in this bill motivated her to conduct informal research on the implications of this law. She

“[I]t is very important to tell people that Islam is not an oppressive religion, that no one is forcing anyone to wear a hijab — actually people are forcing women to take them off.”

- Lamija Mrndic

presented towards Muslims.

Coming to Montreal, where tensions are still present, allowed her to reflect on what exactly Muslim women are being targeted for, saying that in the context of Women’s History Month, “it is very important to tell people that Islam is not an oppressive religion, that no one is forcing anyone to wear a hijab — actually people are forcing women to take them off.”

Another first year Arts student,

finds in the present moment that people need to be willing to speak up against Muslim discrimination, or injustices in general, that are happening both in the Montreal community and beyond.

“I’m glad we have people who are speaking up and out against this. You have a lot of people out there who are willing to make their voices heard and do something about wrongdoings in our [local] community,” she said,

Genevieve Quinn | Visuals Editor

reflecting on the importance of amplified Muslim voices in vital moments. “Now’s a very important time for maybe the university and governments to encourage Muslim voices to say more, speak more; and individuals should take the time to educate themselves on problems that are happening to fellow Muslims or Muslims around the world.”

While the month of Ramadan is meant to encourage reflection and prayer for its believers, the siege on Gaza and worsening conditions in Palestine also come at the forefront of many worries. With supplies continuing to diminish, Muslims fasting in Palestine, who have begun to undergo a mass starvation, are placed in even more dire circumstances. Those watching internationally have found a growing need to complete zakat, one of the five core pillars within Islam: shahada (profession of faith), salat (prayer), zakat (alms/charity), sawm (fasting), and hajj (pilgrimage). Muslims across the world are joining forces by donating to charities to bring relief and aid in any way they can. Ramadan, a holiday meant to be celebrated with loved ones, has now been weighed down by emotions of grief, anger, and dismay instead of joy. While Islamophobia has been present in Quebec long before to the October 7 attack, discrimination has only become amplified across higher education institutions in both the

U.S. and Canada, exemplified by the continued protests and freespeech infringements present at Columbia University and its sister school, Barnard College.

As Ramadan overlaps with this critical historical moment, many Muslims are reassessing their perspective on the importance of the holiday. Mrndic expressed a newfound epiphany, saying that what is happening in Palestine right now “strengthens the point of Ramadan even more.” While fasting calls for a restriction of all food and beverage from only dawn to sunset, Palestinians are forced into total starvation. “I’ve seen stories of Palestinians break fast with just grass. I can’t even begin to imagine what they must be going through,” says Mrndic. Self-reflection during these times proves more necessary than ever before.

Lena recounted what she has been doing during Ramadan to remain conscious of what is happening globally: “I take a few minutes in the morning to just reflect and be grateful for what I have and make dua for those who are not as fortunate, for those who have lost a lot. And I take this time to educate myself more on the issues that are going on. The only thing I think I can do is just make dua — make prayer.”

*Namehasbeenchangedtoprotect the individual’s identity.

News 4 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

Students Hunger Strike to Demand Divestment from Israeli Apartheid

Emma Bainbridge Coordinating News Editor

Since February 18, a group of McGill students have been on a hunger strike to protest the university’s investments in companies funding Israeli genocide and apartheid. Per their demands, they are refusing to eat until McGill divests from and boycotts companies complicit in the Israeli genocide against Palestinians, such as Lockheed Martin, RBC, Chevron, and Unilever. In addition to companies, strikers are demanding an academic boycott for McGill to cut ties with the Israeli state and Israeli universities and remove classes with ties to Israel. There are currently two strikers on indefinite hunger strikes, meaning they have not eaten since the strike began, and several other relay strikers who strike for a couple of days at a time. At the time of writing, one striker is on day 32, while the other is on day 21.

“The reason why we decided to do this is because we weren’t listened to, and McGill is obviously not going to listen to us unless we make them,” said Karim, a relay hunger striker and volunteer in an interview with the Daily. As a McGill student, he sees this as an opportunity for the

One striker has not eaten in over 30 days

university to take action that reflects the values of many students. He argued that many of their demands resonate with the student population, shown through the overwhelming support for SSMU’s Policy Against Genocide in Palestine, supported by 78.7 per cent of SSMU voters with record turnout. Additionally, an open letter to the McGill administration, in solidarity with the hunger strikers and their demands, has received over 1,200 signatures from alumni, faculty, staff, and others affiliated with the university.

At the time of writing, the death toll in Gaza exceeds 30,000, with many more still unaccounted for. The World Bank has also declared that half of Gaza’s population is at risk of imminent famine. Oxfam alleges that the Israeli state is responsible for this crisis by blocking relief from entering Gaza, leading to conditions of “manmade starvation.”

“We’re very lucky where we are right now as hunger strikers, even the ones who are striking indefinitely, [because] they get to do this by choice,” said Karim. He pointed out that Gazans don’t have the luxury of choosing whether they eat or not. He said that he and the other strikers cannot live with the fact that some of

their tuition money is being used to fund this genocide and famine in Gaza. “We’re simply asking for humane treatment [of Palestinians] and until Israel does this, we are under the obligation to vote with our money, and one way is through investments.”

So far, the hunger strikers have not received much of a response from the university administration. Karim explained that although the administration initially offered to meet with the hunger strikers, they proposed a private meeting, whereas the hunger strikers wanted to invite representatives from all pro-Palestinian groups on campus. McGill, despite eventually agreeing to the demand, only offered a 30-minute meeting, which the hunger strikers deemed insufficient time to communicate and discuss their demands. Eventually, the meeting was called off as the administration believed the meeting would be unproductive. While the administration expressed “concern” for their well-being in email exchanges, President Deep Saini has also stated that McGill will not participate in an academic boycott of Israel by severing ties with Israeli academic and research institutions.

Although Karim has been hunger striking for two to three days at a time, he said that it significantly drained both his physical and mental abilities. He imagines this must be much worse for the indefinite hunger strikers, one of whom hasn’t eaten for over 30 days, only consuming a nutritional broth and electrolytes. Although medical teams are monitoring the strikers, Karim argues that the best way to ensure their wellbeing is for McGill to divest from

companies funding Israeli apartheid and boycott Israeli institutions.

As stated through their email to the administration, the hunger strikers warn that “the future of this strike and the inevitable deterioration of the health of the hunger strikers lies in the hands of the McGill administration and the board of governors. Only these individuals have the power to put an end to this, and that is to start taking our demands seriously.”

Music for a Cause: Jam for Justice’s Battle of the Bands

Nonprofit music organization at McGill raises money for charity

Enid Kohler News Staff Writer

Jam for Justice is busy preparing for its largest event of the year: Battle of the Bands. Jam for Justice uses music to support local charities and non-profit organizations, working to create a sense of community amongst local artists, charities, and students.

Battle of the Bands embodies this mission. On April 4 from 7:30 to 11:00 p.m., the organization will

welcome McGill students and local bands to La Sala Rossa to raise funds for The Open Door, a local charity that provides social services to unhoused and low-income people in downtown Montreal.

The Daily spoke with Holly, FirstYear Representative for Jam for Justice, about the details of the event. She explained that Jam for Justice is extremely excited to be working with The Open Door: “we have been wanting to collaborate [with them] for

Courtesy of Jam for Justice

a long time.” The Open Door describes itself as “a beacon of light and hope to many of its visitors,” and Jam for Justice hopes to replicate this sense of warmth and inclusivity through its events. As Holly stated, “music is meant to be shared with others, and Jam for Justice fosters a welcoming and inclusive environment.” She added, “whether you are a musician or you simply like to listen to music –all are welcome!”

Battle of the Bands is a unique event. Unlike Jam for Justice’s previous coffee house and open mic night events, Battle of the Bands is an opportunity to vote on your music preferences, buy in-house designed T-shirts, and watch student bands perform live. Holly told the Daily that audience members can expect “a line up of five different bands, all of whom are students at McGill,” with music ranging from “pop, punk, rock, funk, and jazz.”

The bands include: The Longest Year, Nautical Twilight, The Peterman Experience, Something at the Bottom of the Lake, and Merekat. After every band performs, audience members will have the opportunity to vote for their favourite performance. Holly encourages McGill students to “stay to the end” to participate in the voting

process, which adds a lighthearted competitive edge to the event. Not only does Jam for Justice support local charities, it also uplifts musicians with smaller platforms. In an age of an overwhelming breadth of online music streaming, Holly emphasized the importance of seeing live music performances. When musicians perform live, “it is the most raw version of that music. Getting to share [their music] faceto-face with their audience instead of through a screen” is special, she told the Daily

Courtesy of Jam for Justice

Holly said that “at the heart of music is a sense of community; community and music go hand in hand.” Battle of the Bands is the perfect opportunity to experience and support this community.

To find out more about the event, visit Jam for Justice’s Instagram page, @jam_for_justice. To learn about the bands who will be performing, visit their Instagram pages: @the.peterman.experience; @somethingatthebottomofthelake; @longest.year; @natuticaltwilight_ music; and @merekat.tv.

News 5 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

Courtesty of the Hunger Strikers

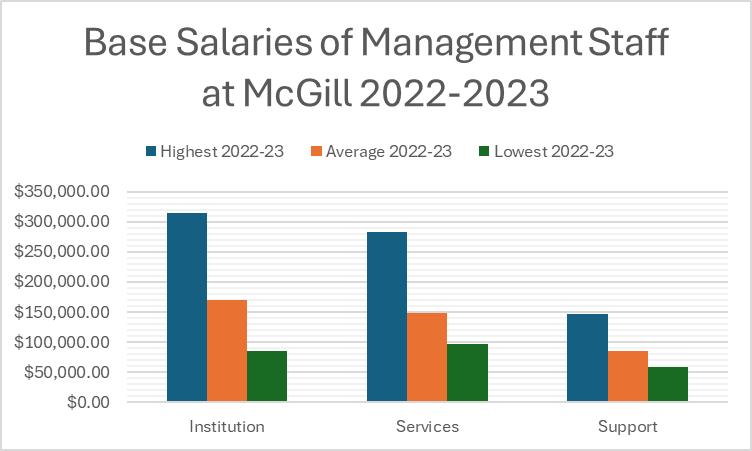

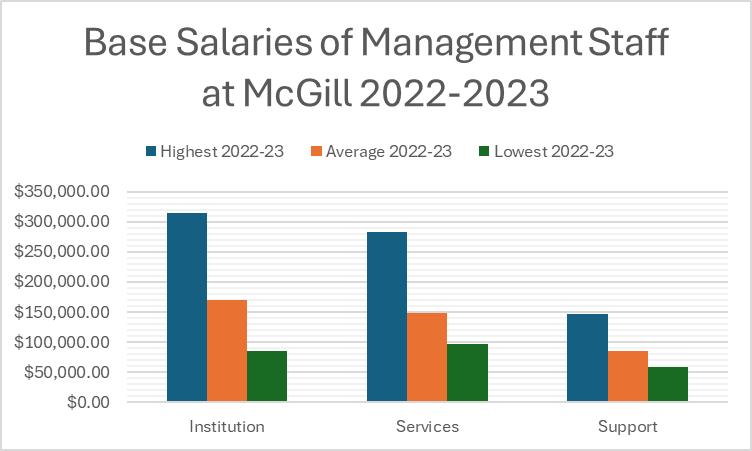

Average Salary of McGill’s Senior Administration Increased by 9.6 per cent in 2022-2023

What McGill’s annual audit shows us about admin salaries

Emma Bainbridge Coordinating News Editor

Every year, McGill submits an audit to the Quebec government which includes, among other information, the salaries of the university’s senior administration. The report for the 2022-2023 academic year was released in November and is publicly available on the National Assembly’s website. 42 members of the McGill Senior Administration, including deans, vice-principals, the president and vice-chancellor, and the secretary general, have their salaries published in this audit. In addition to salaries, the audit contains information

about the university’s financial status, performance, and plans for future development.

Those who were at McGill last year may remember that between Suzanne Fortier’s departure in August 2022 and Deep Saini’s arrival in April, Christopher Manfredi assumed the role of Principal during the interim period. Taking this position in addition to his regular position as Provost and Executive VicePresident (Academic) gave him the highest salary last year. With the salaries from both positions combined, he earned $851,612 in total, an increase of 131.85 per cent compared to the previous year. The other top five total earners at McGill that year were Suzanne Fortier (former

Principal and Vice-Chancellor), David Eidelman (Dean of the Faculty of Medicine), Marc Weinstein (Vice-President, University Affairs), and Deep Saini (current President).

In addition to senior administration, the audit also gives a summary of the salaries paid to management personnel in three categories: institutions (such as faculties, schools, departments, etc), services, and support workers. While not listing individual names, the audit displays the highest, lowest, and average salary for each category. On average, staff managing components of the institution are paid the most, while those managing support staff are paid the least.

When comparing the salaries with those of the previous audit (2021-2022), there are striking differences. For members of the senior administration, the average base salary increased by 9.6 per cent, although this decreased to 5.8 per cent when removing Manfredi. In comparison, institution management staff had an average increase of 2.8 per cent while services management staff had an increase of just 0.44 per cent. Staff managing support workers on the other hand saw a slight decrease in their average salary of 0.31 per cent. For context, the Bank of Canada estimates that the average annual rate of inflation between 2021 and 2023 is 5.53 per cent.

This year, the President Saini admitted that McGill is likely to experience significant negative financial impacts if the Quebec government’s plan to increase tuition for out-ofprovince and international students goes ahead. This has resulted in a hiring freeze and many job reductions and layoffs. Additionally, in order to offer the Canada Award to cancel out the increases, Saini has warned that the university will have to make “financial sacrifices.” Future audits will show whether these financial sacrifices will extend to the salaries of the senior administration.

Every year, McGill submits an audit to the Quebec government which includes, among other information, the salaries of the university’s senior administration.

NEWS 6 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

This year, President Saini admitted that McGill is likely to experience significant negative financial impacts if the Quebec government’s plan to increase tuition for out-of-province and international students goes ahead. This has resulted in a hiring freeze and many job reductions and layoffs.

Future audits will show whether these financial sacrifices will extend to the salaries of the senior administration.

Check out the Daily’s upcoming event:

NEWS 7 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

Montreal in the Shadow of the Moon

The science of eclipses, and how to view them at McGill

Parker Sherry Amelie Chiasson David Sci+Tech Contributors

On April 8, a total solar eclipse will be visible from most of Southern Quebec, beginning at 2:14 p.m. and ending at 4:36 p.m. It will be the first total eclipse visible in Montreal since 1932 and will be the only total eclipse in the Greater Montreal Area for the next 180 years. To celebrate, the Trottier Space Institute will be holding a public Eclipse Fair and Viewing Party at McGill’s Downtown Campus and the Gault Nature Reserve.

What we experience as solar eclipses are largely a cosmic accident. An eclipse occurs when observers on Earth perceive the Moon’s angular size to be roughly the same as the Sun’s, allowing the Moon to fully obscure the Sun from view. A total eclipse extinguishes daylight and can drop the ambient temperature by as much as 10°C.

If the Moon’s path about the Earth were contained in the orbital plane of the Sun – known as the ecliptic – we would expect to see a solar eclipse once every 28 days. The Moon’s orbit, however, does not stay in the ecliptic: a 5° offset between the two orbital planes guarantees that, more often than not, prospective eclipses wind up becoming disappointing nearmisses. Because of this, total solar eclipses are incredibly rare, passing over any spot on the Earth only once every few centuries.

Because of their rarity, people have been fascinated by solar eclipses since the faintest beginnings of civilization. The word “eclipse” comes from the Greek ékleipsis, meaning “to abandon,” but the first recorded eclipses may have occurred much earlier, possibly as early as 3340 B.C.E.

It is dangerous to look directly at the Sun before totality – the moment at which the Moon completely obscures the Sun. Modern eclipse observers use special protective lenses, or solar filters, to block out the Sun’s rays. The filters are coated with materials that decrease the intensity of incoming light or, in some cases, block out all but a certain wavelength of light. With this equipment, even casual observers can stare safely at the Sun for extended periods of time and discern a variety of interesting phenomena. Often, coronal mass ejections, streaks of plasma cast from the surface of the Sun, can be faintly seen behind the shadow of the Moon.

It will be the first total eclipse visible in Montreal since 1932 and will be the only total eclipse in the Greater Montreal Area for the next 180 years.

During eclipses, scientists are allowed glimpses of astronomical phenomena that the brightness of our star would normally keep hidden. The 1919 total solar eclipse, for example, was used by Arthur Eddington and other astronomers to verify Einstein’s theory of general relativity: light from distant stars was slightly bent by the Sun’s enormous gravity, in line with Einstein’s predictions. Nowadays, astronomical research tends to focus on transit events occurring at other, more distant stars, rather than local eclipses. Here at McGill, researchers use eclipses in distant star systems to analyze the atmospheric composition of exoplanets, in order to determine whether they may be candidates for life outside the Solar System.

“When a planet passes in front of a star,” says Dr. Nicolas Cowan, Professor of Astrobiology at

During eclipses, scientists are allowed glimpses of astronomical phenomena that the brightness of our star would normally keep hidden.

McGill, “its atmosphere appears bigger when viewed at different wavelengths of light, which can tell you what molecules are present in that atmosphere. Through this technique, we’ve already discovered lots of greenhouse gases in different atmospheres.

Once we detect an atmosphere with, say, water vapour in it, then we can start to try really hard to see if we can detect other gases, like ozone or methane.”

This method, known as transit spectroscopy, will be applied to much of the data collected by the James Webb Space Telescope, but eclipses remain a unique opportunity for the public to make interesting observations much closer to Earth using simple equipment. As of March 18, municipal libraries across Montreal have begun distributing eclipse glasses, and the English Montreal School Board and LBPSB have announced that April 8 will be a pedagogical day, which means amateur astronomers of all ages will have ample time to watch the rare transit as it occurs. As part of the Eclipse Fair, several telescopes outfitted with solar filters will be set up at the downtown campus.

There will also be a handful of smaller solar scopes, which reflect the light of the sun into a small viewing box and allow the Moon’s shadow to be viewed without risk.

Much of the equipment will be managed by graduate and undergraduate volunteers from the Trottier Space Institute and the Anna McPherson Observatory. “Students are heavily involved in the eclipse fair,” says Carolina CruzVinaccia, Program Administrator at the Trottier Space Institute (TSI). “We couldn’t do anywhere near the amount of outreach that we currently do without them. They’re really passionate about communicating their work, and they want to make sure people know what’s going on at the university.”

Cruz-Vinaccia heads the Eclipse Task Force organizing events for the upcoming eclipse. Activities at the Fair will include a makeyour-own pinhole camera station, a photo booth, and a Solar System Walk, where the planets will be arranged to scale from Roddick Gates to the McCall-McBain Arts Building. The Redpath Society, in collaboration with TSI, will be organizing a program on the cultural significance of eclipses throughout history and their effect on wildlife, while the Rare Books and Special Collections section of the McLennan Library will be displaying records of eclipses from antiquity. In the wider Montreal community, Space Explorers, a McGill student-led physics outreach program, will be holding

workshops to teach elementary school students about what eclipses are and how they work in preparation for April 8.

“The idea is to give not only the McGill community, but the surrounding community the opportunity to experience this once-in-a-lifetime event together,” Cruz-Vinaccia says. “Anecdotally, people who’ve seen total eclipses before say that it’s quite a moving experience, and we feel that it would be something that’s better viewed together.”

“Anecdotally, people who’ve seen total eclipses before say that it’s quite a moving experience, and we feel that it would be something that’s better viewed together.”

- Carolina Cruz-Vinaccia

Sci+Tech 8 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

Amelie Chiasson David | Visuals Contributor

Vancouver Lawyer’s Use of AI in Legal Proceedings Sparks Ethics Debate

How does AI fit into the legal profession?

Gemma Holland Sci+Tech Contributor

Vancouver lawyer Chong Ke has recently found herself at the centre of a case concerning the ethics of using artificial intelligence (AI) in legal proceedings. The controversy unfolded when it was revealed that while representing businessman Wei Chen in a child custody case, Chong Ke filed an application containing fabricated cases generated by ChatGPT. This represents the first instance of AIgenerated material making its way into a Canadian courtroom.

Ke had filed an application to allow Chen to travel with his children to China. The application included two cases as precedent: one in which a mother took her 7-year-old child to India for six weeks, and another where a mother’s application to travel with her 9-year-old child to China was approved. However it was soon discovered that these cases did not actually exist, and instead they had been fabricated by ChatGPT.

Allegedly, Ke asked ChatGPT to find relevant cases that could apply to her client’s circumstances. OpenAI’s chatbot generated three results, two of which Ke then used in the application. When lawyers of Nina Zhang, Chen’s ex-wife, were unable to locate the referenced cases, Ke realized her mistake. She attempted to withdraw the two cases and quietly provide a new list of real cases without informing the opposition. Zhang’s lawyers then demanded copies of the two original cases, leaving Ke no choice but to inform them expressly of her mistake. She wrote a letter acknowledging her actions, calling the error “serious” and expressing her regret. In an affidavit, Ke later admitted her “lack of knowledge” on the risks associated with using AI, saying it greatly embarrassed her to “[discover] that the cases were fictions.”

Justice David Masuhara, who presided over the case of Ke’s client, wrote in his ruling that “citing fake cases in court filings… is an abuse of process and is tantamount to making a false statement to the court,” going on to say that the improper use of AI could ultimately beget the miscarriage of justice. Masuhara

mandated Ke to review her files and disclose if AI had been involved in any other materials she had submitted to the court.

Fraser MacLean, the lead counsel of Ke’s opposition, also emphasized the serious dangers of using AI-generated content: “what’s scary about these AI hallucinations is they’re not creating citations and summaries that are ambiguous, they look 100 per cent real.” He adds that it is important to be “vigilant” in verifying the validity of a legal citation.

Despite Masuhara finding Ke’s apology to be sincere, she will be held liable for the costs incurred by Zhang’s lawyers in remedying the confusion. The judge also acknowledged that she was suffering the effects of “significant negative publicity” following her misconduct. The Law Society of BC has also issued a warning to Ke affirming the ethical obligation for lawyers to ensure accuracy with the growing use of AI tools. In addition to incurring the debt of her opposition, Ke will also be facing an investigation from the Law Society of BC.

While Ke’s AI-generated content was removed before it could have any significant impact on court proceedings, this case underscores the ethical risks surrounding the use of AI in the legal field. Discussions are already being held around the importance of lawyers’ diligence when it comes to navigating AI tools in their work and the need for clear guidelines to prevent potential abuses of the process. Thompson Rivers University law librarian Michelle Terriss commented that this ruling sets a new precedent, indicating that “[these] issues are front and centre in the minds of the judiciary and that lawyers really can’t be making these mistakes.”

Lawyers have an ethical duty to acknowledge the risks and benefits that arise from the use of AI tools. But as the use of AI grows, new questions around its implementation in the legal field are beginning to emerge, including whether or not a lawyer can ethically bill a client for work that an AI tool performed or if using AI to handle court materials is a breach of confidentiality. The latter is especially concerning

as most AI tools, including ChatGPT, do not guarantee the confidentiality of user inputs – in fact, OpenAI’s terms of service state that a user’s exchange with the program “may be reviewed” by OpenAI employees in order to improve the system, and that the responsibility of maintaining confidentiality lies with the users themselves.

While AI can provide significant improvements to tasks including electronic discovery, litigation analysis, and

Eric Duivenvoorden | Visuals Editor

legal research, concerns persist about biases and prejudices in the system in addition to the potential for legal fabrication. Bias in AI technology is common and results from the training process of AI tools. For instance, Microsoft’s AI tool for text-based conversations with individuals was found to mirror discriminatory viewpoints that had been inputted in training conversations. These biases have already made it into the legal field, with a prominent example being the Correctional Offender

While AI can provide significant improvements to tasks including electronic discovery, litigation analysis, and legal research, concerns persist about biases and prejudices in the system in addition to the potential for legal fabrication.

Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) system, an AI algorithm many US judges used in making decisions regarding bail and sentencing. Investigations revealed that the system, in assessing whether or not a past offender would re-offend, was found to generate “false positives” for people of colour and “false negatives” for white people. The issue lies in the training of AI, as many are programmed to “quantify the world as it is right now, or as it has been in the past, and [to] continue to repeat that, because it’s more efficient,” says AI and robotics expert Professor Kristen Thomasen of UBC.

While the future of AI in the legal field and its ethical implications remain ambiguous, many legal and AI experts, including Professor Thomasen and Justice Masuhara, have weighed in, expressing their beliefs that an AI system could never “truly replace the work of a lawyer,” and that “generative AI is still no substitute for the professional expertise that the justice system requires of lawyers.”

SCI+Tech 9 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

A Look into Tam Khoa Vu’s Hybrid Condition

MAI’s newest exhibition explores the diasporic experience of Vietnamese Canadians

Enid Kohler Staff Writer

On March 13, it was raining lightly and slush slapped against my sneakers as I walked down Jeanne Mance street toward Montreal, arts interculturels (MAI). When I opened the door of the large brick building, I was met with a gust of warm air, and immediately followed the signs toward Hybrid Condition. A small sign post outside of two velvet curtains told me to remove my shoes. I did, before pulling back the curtains and stepping inside the installation.

The room was dark, yet the four projection sheets standing in a square-like formation in the center of the room formed a bright light, impossible to overlook. Changing images and video clips flashed on the screen and commanded my gaze – an athlete in a basketball jersey dancing in a gymnasium, men laughing around a small table, a person in a navy blue suit and red tie speaking directly to the camera. A pulsing, quick beat accompanied the images, propelling them forward and adding an exciting energy to the footage.

Vietnamese-Canadian artist Tam Khoa Vu first drew inspiration for his immersive installation by talking to a group of Vietnamese diaspora who were living in Vietnam at the time. In an interview with the Daily, Vu said that “we were talking a little bit about this dual identity of belonging and also not belonging in Vietnam, and belonging maybe to whatever Western parts of the world we had originated from.” He explained that the term “condition” appealed to him because of its connotation of a “sickness.” He said, “It’s almost a little bit tongue and cheek, you know? There’s a little bit of this melancholia or sadness that can occur when reflecting on identity … but it’s not entirely just trauma and pain … it can be joy, also.”

Vu explained that at the surface level, “hybrid condition” is “a cool sounding phrase that comes from different aesthetic backgrounds,” and that when you peel back

the layers, “you can find deeper meaning to it.” This idea reflects the nature of Vu’s installation. At first glance, the viewer is attracted to the video installation and its fast moving images “like a moth to the light,” Vu said. “But once you sit with the work and experience the work, you realize all of the layers and what it does [on a deeper level].”

At first, Vu began creating Hybrid Condition to represent the Vietnamese diaspora within the world of fine and contemporary arts. Vu told the Daily that his name is “so front and center” to “show other Vietnamese people [and] other Asian people the possibilities within the contemporary arts world.” In developing his installation, Vu also imagined his 12-year-old self viewing his work. He said, “when I was 12 years old, I didn’t have role models to look up to. I had Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee…and they’re not even Vietnamese.” Vu explained that there is nothing wrong with appreciating such figures, but that it “felt very limiting.” He added, “I like Kung Fu, sure, but I also like fashion, I also like shoes, you know?” Because Vu did not know other Asian or Vietnamese designers when he was a child, he wishes to be such a role model for youth today.

Vu is open to criticism. In fact, he encourages it from young people of colour as an avenue to create “space for the diaspora” in the arts world. He told the Daily, “If some 12-year-old looks at my project and is like, ‘wow, that is so whack, I can do that better,’ for me, that’s also incredible. It’s like, ‘go on, go do something that you want.’”

Vu’s installation does not only speak to diasporic populations or people of colour. Vu said, “I realized that I don’t need to tell a Vietnamese-Canadian, or a Vietnamese-American, or an Asian-American, or a BlackAmerican, what it means to be othered…because we know what feeling othered feels like.” Vu gives “110 per cent” of himself into his installation, and he wants “white people to feel 10 per cent of what it feels like to be othered.” If white

There’s a little bit of this melancholia or sadness that can occur when reflecting on identity…but it’s not entirely just trauma and pain…it can be joy, also.”

- Tam Khoa Vu

people can feel even five per cent, Vu told the Daily, “I would feel like this installation has succeeded.”

To draw in a wide breadth of audiences, Vu works to create an inclusive gallery space. “I want to create a space that my mom can go to and understand, but also that is equally fresh, that your Mile-Ender can also appreciate.”

One way in which Vu approaches this is through using modern digital platforms that can appeal to numerous demographics. His installation includes video extracts projected on four different screens, playing in a loop and at differing times, so that each visitor will have a unique experience.

When asked where he sourced the video footage, Vu told the Daily that much of his footage comes from memes online. He said that he “conducted a lot of that research the way a lot of people conduct their research – first thing in the morning, when you wake up and crack open Instagram.” He started saving numerous memes, and soon, individuals began sending Vu memes as well. Vu also shot a large part of the footage himself; one

screen of footage is entirely shot by Vu in Vietnam.

Vu also uses social media as an “artistic vision” and as a “marketing tool” for his work. In addition to his visual artwork and his current installation, Vu is the founder of an import business, TKV Fine Arts & Financial Arts. The business subtly challenges perceptions of Vietnamese culture by giving new meaning to apparel and objects commonly found in Vietnam, such as grocery bags, sandals, and blue-collar workwear.

Vu told the Daily that he uses his e-commerce business “as a vehicle for storytelling” to explain to his audiences why these common garments are important. Through his social media usage, Vu can market both his art installation and his business. He said, “When I have marketing and hype for the business, it channels into the artwork, and the artworks also feed into my art practice.”

In an interview with The Creative Independent, Vu said, “I don’t want to go to bed on Sunday just being afraid of Monday. Life can pass you by in that way.” Vu

Courtesy of Tam Khoa Vu

told the Daily that this mentality still informs his work today. Vu stated that he is “unabashedly” himself, and that his sincerity and upfrontness inform his work. He said that “a lot of Asian-Canadian people are typically seen as ‘timid,’ and ‘meek,’ and ‘model-minorities,’ and then when you have someone like me ‘qui peut changer de langue facilement,’” – Vu speaks English, French and Vietnamese fluently – “does that make people scared, or worried, or does it challenge their notions of what an Asian person is?” Vu predicts that his installation will encourage visitors to confront the question “am I racist?” and hopes that his work will overturn prejudices.

Vu strongly encourages McGill students to visit HybridCondition Entry to the exhibition is free and runs until March 30 from Tuesday to Saturday between 12:00 and 6:00 PM. For more information on the exhibition, visit m-a-i.qc.ca/en/ event/hybrid-condition. To learn more about Vu and his upcoming artistic pursuits, check out his Instagram page @tamvu.biz

culture 10 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

A Return to Murderous Lesbians

A review of Love Lies Bleeding

Jane Carli Culture Contributor

Spoiler warning

Upcoming films featuring same-sex desire are frequently met with feverish excitement and anticipation from members of the queer community. The buzz is usually followed by polarizing commentary that attempts to decide the film’s place in the queer film catalogue, regardless of how recently the film came out. Since its release on March 14, Rose Glass’s lesbian thriller Love Lies Bleeding has been similarly received through this model.

Despite receiving praise for subverting the “male gaze,” the film seems to do just the opposite, falling into the same fetishistic trap that plagues so many other WLW films.

The internet’s sapphic community has cast Love Lies Bleeding in a largely positive light, entranced by the film’s adrenaline-inducing body horror and eroticism. As a proponent of all things lesbian, I wanted to love the film as much as the internet was telling me to. I wanted to fall head first into the Kristen Stewart fandom and to deep dive into Glass’s euphoric use of 1980s pop culture. But I just couldn’t: not for the full film at least.

Love Lies Bleeding ’s cinematic landscape and cast performances create a compelling direction for the story. As an A24 film, the arthouse aesthetic is undoubtedly alluring. The film takes place in the liminal setting of a New Mexican desert town filled with criminals, psychopaths, and gym buffs.

Lou (Kristen Stewart) works as a gym manager and falls for Jackie (Katy M. O’Brian), a bodybuilder passing through town on her way to pursue her dreams in Las Vegas. The characters themselves are equally compelling, with mysterious, largely covert backstories and hot-headed temperaments, ramming through any obstacle or challenge in their way.

The first third of Love Lies Bleeding has high potential. However, I found the latter two thirds to be too reliant on genre conventions that only distract from any concrete plot or meaning. After Jackie temporarily moves in with Lou, the film strays from their relationship to Lou’s family lore – a complex web of crime and deceit held together by her ringleader father. As a result of this narrative shift, the women’s budding character development is flattened, and any explanation for their actions or inner motivations is lost. It seems that all we will ever find out about Jackie is that she’s an avid bodybuilder. Furthermore, Lou and Jackie’s relationship gets sidelined and commandeered by men until the film’s confusing final moments, when Jackie turns into a giant to pin down Lou’s father once and for all.

Despite receiving praise for subverting the “male gaze,” the film seems to do just the opposite, falling into the same fetishistic trap that plagues so many other WLW films. The six single men who sat in front of me at the Cineplex Forum’s Friday night screening only reinforced my initial impression: this film may have been written about queer women, but it was not a film made for them.

Love Lies Bleeding displays women’s bodies without establishing necessary empathy between the characters and the viewer. A quick search on the voyeuristic qualities of the film led me to find numerous news articles about men who had been arrested in the last week for lewd behaviour while viewing Love Lies Bleeding in theatres. Remarkably, these articles haven’t really been acknowledged on TikTok or other social media platforms.

The behaviour of these male viewers, and how quickly it

Eric Duivenvoorden | Visuals Editor

the couple spent the majority of the film either trying to kill

The six single men who sat in front of me at the Cineplex Forum’s Friday night screening only reinforced my initial impression: this film may have been written about queer women, but it was not a film made for them.

has been ignored, says a lot about the politics of lesbian representation and moviegoing. While this doesn’t seem like any fault of the film inherently, I was surprised by how quick people were to praise its representation and to remark upon how amazing Lou and Jackie’s relationship was when

each other or having sex. It felt almost performative, like the sex scenes were only put in to appease the viewer and substitute an actual foundation for the characters’ relationship.

The release of this film was an unfortunate reminder that lesbian films have not been able to escape objectification

and fetishization by men unless they explicitly critique patriarchal and heteronormative expectations (I would argue the recent queer film Bottoms was more effective at achieving this). But of course, not every lesbian film should be expected to offer some sort of critique in order to be taken seriously. While it’s important that both characters survive and presumably stay together, to emphasize such an ending feels like commending the bare minimum of a film that leaves other elements of queer representation unexplored. All this to say, Love Lies Bleeding is an entertaining experience from an intriguing filmmaker with an obvious body-horror speciality. I am curious to see more of these elements in whatever Rose Glass decides to create next.

culture 11 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

The Anatomy of Anatomy of a Fall

Justine Triet’s courtroom throws convention out the window

Isabella Roberti Culture Staff Writer

Content warning: domestic violence

Spoiler warning

“ P.I.M.P” by 50 Cent is having an unprecedented resurgence in pop culture. An immensely talented and adorable dog won an award at Cannes, has his own Wikipedia page, and attended the Oscars. A dreamy, French, silver fox lawyer has taken the internet by storm. These unforeseen events can be attributed to Justine Triet’s Anatomy of a Fall , which has arguably been the film that has kept the most momentum post awards season (albeit largely thanks to North America always being late to the hype of international films). It also did not walk away empty handed, winning the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, and deservedly so – the film offers a completely fresh take on the legal drama that only a female director could conceive.

Anatomy of a Fall is the story of Sandra (Sandra Hüller), an author living in a secluded town in the French Alps, whose husband Samuel (Samuel Theis) mysteriously falls to his death from the attic and is found by their visually-impaired son Daniel (Milo Machado-Graner). Sandra is suspected for her husband’s murder, for which she undergoes a tense and emotional trial. What makes the film so different from the standard courtroom drama, however, is that Sandra’s legal interrogation reflects the kind of suspicion and blame that women (especially bisexual women, like Sandra), are met

Fall comes right at the end; Sandra is acquitted, but we never find out exactly how Samuel died. This perplexing conclusion, though, is not the first time the film withholds information or disguises the fact that the audience, who is usually granted more omniscience than characters, knows just about as much as they do. In a pivotal scene, an argument between the couple the day before Samuel’s death – recorded by her husband without her knowledge or consent – is used against Sandra in court. As it begins playing in the court, and we see it transcribed on the screen, the scene transitions into a flashback of the row itself, presumably from Sandra’s point of view. Just before the climax of the fight, Triet throws the viewer back into the courtroom, where sounds of glass breaking and other aural indications of violence fill the silence. Although Sandra provides the court with an explanation of violence, we never actually see it. The only character one could argue knows more than us is Sandra herself; we never actually see her actions the day of Samuel’s death on screen – we only have her verbal testimony. Despite being a defendant under scrutiny from just about everyone else in the film, she has the most agency over what both the characters and the audience know. The fact that a woman has agency over what the truth of the scenario is, and that it never comes out, shows Triet’s brilliant message that objective truth and patriarchy go hand in hand. “It’s not reality, it’s our voices. That’s true, but it’s not who we are,” argues Sandra. Women are constantly having their voices used against them by men in the search for objective right or

Women are constantly having their voices used against them by men in the search for objective right or wrong, true or false, innocence or guilt. Having a woman control the entire scope of the narrative obstructs the audience and the other characters from seeing the truth “objectively.”

with every single day. Through flashbacks and domestic scenes outside the courtroom where we see Sandra in her most intimate moments, the film explores how trust is something bisexual women are hardly ever afforded under any circumstances.

Perhaps the most subversive and surprising element of Anatomy of a

wrong, true or false, innocence or guilt. Having a woman control the entire scope of the narrative obstructs the audience and the other characters from seeing the truth “objectively,” and the patriarchal satisfaction of finding a woman guilty, as is typical of the legal system, is thrown out the window.

It isn’t a coincidence then that the prosecutor is a man while the defendant, the primary witness (her son), her son’s court monitor Marge, and the judge are all either women or, in the case of Daniel, a disabled boy. As someone who does not embody the perfect patriarchal ideal of masculinity, Daniel is aligned with the women in the courtroom against the infuriating prosecutor. The women have control over the information and the outcome, yet it is a man who delivers the final argument for what he believes to be the truth. The prosecutor attempts to incite, provoke and goad Sandra through chastising and frankly sexist interrogation tactics. But Sandra remains resolute, having likely experienced similar accusations from her husband Samuel, and from countless other men for as long as she can remember.

An eye-roll-worthy but salient moment of the trial comes when the prosecutor spotlights Sandra’s infidelity with women and her identity as bisexual, implying that her sexual orientation makes her inherently promiscuous and untrustworthy. Sandra is unbelievably calm and collected in the face of this preposterous claim, but her sexuality as a point of contention for men is a very important aspect of the film. These kinds of accusations are all too familiar to bisexual women, both demeaning them and propping up the straight white man as the epitome of the healthy partner. This part of the trial shows the depressing truth that

even the emotional fragility and instability of men will be taken more seriously than a calm and composed woman. If anything,

towards or against Sandra to be purely emotional because we don’t know the truth – an approach seemingly contradictory to the

Its discursive elements shine through their subtlety, and all the details of the case become a means through which Sandra’s husband’s life, not just his death, are easily blamed on her for being a bisexual woman.

Sandra’s coolness during the trial is completely in line with her character, because as a bisexual woman, she’s been on trial her entire life.

So how did a film with such strong queer themes, a woman who is morally ambiguous, no shocking reveal, and very few adult male characters become an awards season darling? For lack of a better term, Justine Triet has played high-brow cinema’s game, but by her rules. The Academy is no stranger to the courtroom drama, but usually deals with them in a very conventional way. Acclaimed courtroom dramas are usually male-dominated, where the hero is either a defendant who has been wrongly convicted, or a conflicted lawyer trying to do the right thing. None of these tropes appear in Anatomy of a Fall . The film instead allows our biases

genre itself. Its discursive elements shine through their subtlety, and all the details of the case become a means through which Sandra’s husband’s life, not just his death, are easily blamed on her for being a bisexual woman.

There were so many films by women this year pertinent to feminist issues that were neglected by major awards ceremonies; Priscilla was absent from the Oscars, and of course all hope was shattered for Barbie . And although queer representation was fantastic in the indie/comedy genres, there wasn’t a ton that had the level of prestige (or pretentiousness) demanded by the Academy. But thanks to its unprecedented approach to the courtroom drama and perfect amount of subtle criticism, Anatomy of a Fall triumphed, and gave us a bisexual, feminine masterpiece in a legal drama’s clothing.

culture 12 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

Genevieve Quinn | Visuals Editor

The Meaning of Leaving: Womanhood from Toronto to Hong Kong

A review of Kate Rogers’ latest poetry collection

Arismita Ghosh Culture Contributor

Content warning: domestic violence, sexual violence, political violence

Iwas lucky enough to read Kate Rogers’ The Meaning of Leaving while on a train leaving Toronto, which I think is the most aptly ironic location to experience this bittersweet poetry collection. A Canadian poet who lived in Hong Kong and China for more than two decades, Rogers recently moved back to eastern Ontario in 2019. This is where The Meaning of Leaving takes off, leading the reader on a journey that is constantly on the move from one city to another. Each poem blurs the line between departure and arrival, navigating the intersections of female loneliness, domestic violence, and the search for identity. Published in February 2024 by the Montrealbased publishing house Ace of Swords Publishing, this beautiful collection enters the literary fray right in time for Women’s History Month.

Each poem blurs the line between departure and arrival, navigating the intersections of female loneliness, domestic violence, and the search for identity.

The book opens with the poem “Unreal City,” a sort of anti-ode to Toronto that brings to light all the violence simmering underneath the surface of the city. By mentioning specific locations by name, Rogers makes the setting of this “unreal” poem feel all the more “real” –allowing the words to occupy a tangible space in real life. Even as someone not from Toronto, I was able to relate to the scenes exactly as she laid them out, largely in part due to her straightforwardly familiar tone. “Unreal City” sets the scene for the rest of the poems in this collection, which are divided into five untitled sections that continue moving chronologically through different periods in the poet’s life.

Rogers uses the first section to invite the reader into her childhood home,

revealing the abuse she faces at the hands of her father, and establishing a link between this early violence and the violence she goes on to experience in her romantic relationships with men. She wastes no words, shying away from subtlety in favour of boldly laying out the events as they happened.

While I appreciate the lack of restraint and the trust she places in her reader, at times the shrewdness of Rogers’ poetry leaves little room for interpretation. In “Derrick’s Fist,” Rogers’ emphasis on elaborate descriptions of bruises leave a striking first impression on the reader, but her bluntness simultaneously results in an opaqueness that I felt lacked a more personal connection with the speaker. “Albino Sword Swallower at a Carnival, 1970” is an example of another graphic poem I felt was executed better. Here, Rogers is able to show her love for meta-textual references through her masterful association of the violence from her early sexual encounters to the violence experienced by a circus sword-swallower.

Section Two moves forward into Rogers’ time spent in China and Hong Kong, bringing these settings to life with the same attention to detail as she expressed for Toronto. In “On My Way to Cantonese Class” and “Lamma Island Tofu-fa,” Rogers crafts a loving relationship between herself and the city, pointing out the colourful characters that inhabit its every corner. Something as simple as tofu-fa from a roadside hut is likened to salvation. These images of home reach a turning point in the titular poem “The Meaning of Leaving,” in which she recreates her life story so far by moving from the lakes of Ontario to the Hong Kong coastline. The poem takes its title from a translation of “Requiem” by Bei Dao; each line of Dao’s work sandwiches Rogers’ stanzas, giving the words an entirely new meaning. She succinctly communicates the feeling of being lost in one land, before finding peace in another.

Rogers moves further into the realm of politics with Section Three, drawing the reader’s attention to pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong. Like in her earlier poems, she conflates real-life conflict and trauma with fantastical images: the authoritarian government becomes a Gate of Hell, the young protesters become the nation’s saviours.

Rogers emphasises how the personal and the political interact with each other in times of crisis, and to me, her poetry seems to suggest that love and resistance are inextricable from one another. In “The Jizo Shrine,” we see the importance of holding on to close female friendships. This love letter to the long-lasting bond between two women stands in as an ode to letting go of grief, whether it be private or collective.

Though The Meaning of Leaving complicates the ideas of home and homeland in a nuanced, self-aware manner, I found myself growing wary of certain poems that seemed cast in an orientalist light. The implications of the line “Yet I long to uncover more layers / of Hong Kong’s midden heap” in “Cantonese Class” make me uncomfortable, especially as I recall the long colonial history of white travelers wishing to “uncover” the secrets of the East. “Sei Gweipo” in Section Four is a candid retelling of Rogers’ experience as a white woman in Hong Kong, highlighting her struggle in reintegrating with Canadian society by comparing herself to a “white ghost.” It’s almost overly self-aware in its execution, leaning towards feelings of white guilt, which makes it all the more difficult to

Courtesy of Ace of Swords Publishing

read from a non-white perspective.

The book is ultimately redeemed through its meditations on womanhood and anger, which I found embodied primarily in “The Nose-Ring Girl.” Rogers plays with the idea of female vulnerability as she wonders about this stranger’s backstory, before connecting it back to her own college days. The titular nose-ring girl personifies strength and tenacity, as she continues to stand by her principles even when she does not need to. As we enter the fifth and final section, the reader is introduced to even more figures of feminine resilience. Rogers brings back her love for meta-textual references as she imagines an encounter with a victim of the Spanish Flu, and reimagines the tale of the Don Jail ghost. In both cases, she reclaims a story told largely by male voices to instead shed

light on a female perspective.

Rogers chooses to end this poetry collection by returning to the bird motif sprinkled throughout the book, taking on its themes of flight and motion. “Ode to the Ode to the Yellow Bird” is yet another retelling of a tale from the male poetic tradition. Rogers counteracts the pessimism of Pablo Neruda’s “Ode to the Yellow Bird” by making this poem an affirmation of joy. Her yellow bird is the very ethos of the kind of womanhood she writes about in The Meaning of Leaving: she is the Don Jail ghost, the girl in the pink tutu and Nikes, the lady with a bruised face at the fruit market. She is a symbol of resilience and ambition. And despite everything she has been through, the book grants her one ecstatic cry of hope in its very last sentence: “You live!”

Culture 13 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

Calluses and Carabiners

How queer women have rocked the climbing world

Catey Fifield Managing Editor

If you’re a queer woman who’s been living in Montreal for a while, you probably know the spots. Walk into Champs on a Monday, L’Escogriffe on a Friday, or Aréna Saint-Louis on the day of a roller derby, and you’re sure to encounter an impressive display of mullets, nose rings, denim vests, and insect tattoos. There’s another place where, in recent years, Montreal’s queer women have been gathering in strength: the climbing gym.

Some of the most popular climbing gyms in Montreal include: Café Bloc, in Ville-Marie; Shakti Rock Gym, in the Mile End; Allez-Up, with locations in the Mile End, Pointe-Saint-Charles, and Verdun; and Bloc Shop, with locations in Chabanel, Hochelaga, and Mile-Ex. Almost all of Montreal’s climbing gyms are lined with bouldering walls, which don’t require the use of a harness or ropes, but some also offer top rope climbing. The gyms welcome new and experienced climbers, offering day-long or week-long passes as well as monthly memberships.

An increased interest in climbing and a growing demand for climbing gyms are not phenomena unique to Montreal. The sport has been gaining in popularity since the mid-2010s, and its introduction as an Olympic sport in the 2020 Tokyo Games has only accelerated the trend. Montreal is also not the only city where queer climbers are bonding over their love of coloured plastic rocks. The emergence of organizations and community groups like Van Queer Climbers (Vancouver, BC), Queer Climbers London (London, UK), and ClimbingQTs (Australia) attest to the prevalence of queer climbing across the world.

In an article on “How climbing became a favorite hobby among queer women in China,” Nathan Wei suggests that the sport’s openness and relative newness

Most climbers will “gladly accept new climbers into their spaces regardless of ability, skill level, gender, or sexual orientation,” Stephenson added.

have encouraged its popularity among WLW. A bisexual woman referred to by the pseudonym HS told Wei that “climbing is more gender-friendly than many other sports,” while another woman climber remarked that the community “has not been dominated by men yet.”

Toronto-based climber Jill Stephenson, who has been climbing recreationally for about two years, echoed these sentiments in an interview with the Daily. Not only is there “less of an established gender hierarchy” in climbing, she said, but it is also a “highly social sport” with a “very supportive community.”

Most climbers will “gladly accept new climbers into their spaces regardless of ability, skill level, gender, or sexual orientation,” Stephenson added.

Isabelle Mills, a Montrealbased climber who boulders at Café Bloc, noted that the looser restrictions at climbing gyms compared to other gyms and sports facilities can help (queer) women to feel more comfortable there. The lack of a dress code –not to mention the expectation that women wear form-fitting clothing to accentuate their breasts and butts for the viewing pleasure of male gym-goers – is especially freeing: “there’s no idea of what you’re supposed to look like as a climber,” Mills said.

Although outdoor climbing trips and equipment can be expensive, indoor climbing tends not to be as financially prohibitive as other sports. Simon Rouillard, one of the co-founders of Queer Bloc, a community group that organizes monthly climbing events for

Montreal’s LGBTQ+ community, highlighted the accessibility of climbing in an interview with the Daily: all you need is “yourself, some shoes, and some chalk,” he said. “You don’t need that much more equipment, nor does it have to be fancy.”

Another reason climbing gyms have become such magnets for queer people, Rouillard says, is that climbing “allows us to become one with our bodies.” While he

Magdalena Rebisz | Video Editor

“Anybody and any type of body can be a good climber,” Rouillard told the Daily The climbing communities of Montreal and other places have certainly done a lot of work to create inclusive and supportive environments, but there is still more to be done to make queer people – and others traditionally underrepresented in sport – feel welcome on the wall. Stephenson noted that “even though the

Rouillard cites the fear of intimidation and bullying, body image issues, and lack of confidence as factors that may deter queer people from climbing and other sports.

acknowledges that body awareness and body image are things we all have to deal with, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, queer folks “have had to confront and be aware of our bodies from an early age. We’ve had to be accepting of them.”

Climbing is unique among sports in that success does not depend on a particular body type. While many “problems,” or bouldering routes, may seem to favour taller climbers, there’s always more than one way to get to the top of a wall, and shorter climbers will quickly develop a knack for troubleshooting their way from rock to rock. It’s not all about brute strength, either: flexibility, stamina, and mental reasoning (there’s a reason they’re called “problems”!) are equally integral to the art of climbing.

climbing community is safe and supportive, it can be intimidating to enter a new space and engage with new groups.”

Rouillard cites the fear of intimidation and bullying, body image issues, and lack of confidence as factors that may deter queer people from climbing and other sports. “We have to remember that for a lot of our LGBTQIA+ community, sports haven’t always been available to us,” they say.

Both Stephenson and Mills remarked that organizing events that target specific groups can be a great way for climbing gyms to promote diversity and inclusivity. Queer Bloc is an excellent example of a group that’s doing just that for the queer community in

Montreal. Co-founded by Rouillard and a friend, Daniel Baylis, the organization hopes to facilitate discussions and create connections through its monthly meet-ups.

“Our events are typically low-key but can be a bit fun with DJ sets, happy hours, and even flash tattoo sessions,” Rouillard told the Daily Climbers of colour are also carving out spaces for themselves in a community that has historically been dominated by white athletes. New Jersey-based Tiffany Blount launched Black Girls Boulder in 2020, and Climbers of Color has been active in Washington since 2018. Organizations like ParaCliffHangers and the Canadian Adaptive Climbing Society have also been working to make the sport accessible to people with disabilities.

In addition to holding inclusive climbing events, Stephenson said, it’s important that climbing gyms diversify their hiring practices: “having diverse administration and staff visually indicates that diverse climbers are welcome in the space.”

Rouillard suggested a few other steps climbing gyms can take to make queer climbers feel safe and supported, including: ensuring that any music played is not misogynistic, homophobic, or transphobic; ensuring that washrooms and changing rooms are non-gendered; and including a non-binary option on waivers and membership forms.

If you’re interested in attending queer climbing events and connecting with other queer climbers in Montreal, follow @ queer_bloc on Instagram.

sports 14 March 25, 2024 mcgilldaily.com | The McGill Daily

My Womanhood Is a Work in Progress

We need to stop applying cookie-cutter definitions to the identities we hold so close to heart

Iris O. Ryan Commentary Contributor

Content warning: transphobia

My womanhood is a work in progress. By that, I don’t mean that I am not yet a woman, or that I am waiting to become a woman. Rather, with every day that goes by, my womanhood is molded into shape and given new life in varying and unexpected ways. It’s an ongoing mission that takes a slightly different shape with every day that goes by.

Too often, people try to apply absolute definitions to things like “womanhood,” or “lesbianism,” or even “queerness.” In reality, I don’t think there is such a thing. Our identities aren’t mathematical equations, after all, and it’s only natural that the ways in which we define ourselves in regards to them will change as we grow.

As a trans girl, my journey to accepting myself as a woman was not a straightforward one. Being a woman wasn’t something that came all that naturally to me, especially toward the beginning of my transition. It felt weird to go from thinking that I was a man to being a woman all of a sudden. People expect a lot out of women and I was never sure how much I wanted to, or did, fit into those expectations. Internalized transphobia and misogyny also obviously played a trick on me, but none of that is what being a woman is truly about, is it?