9 minute read

Bariatric Surgery Complications

Welcome to the August issue of The Surgeons’ Lounge. In this issue, Matyas Fehervari, MD, PhD, MRCS, a general and bariatric surgery resident at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College, in London, interviews Haris Khwaja, MD, DPhil (Oxon), FRCS, a consultant bariatric surgeon, also at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital and Imperial College, about two patient scenarios regarding inflammation and infarction of fat and its implications in bariatric surgery.

We look forward to our readers’ questions, comments and interesting cases to present.

Sincerely, Samuel Szomstein, MD, FACS CS Editor, The Surgeons’ Lounge ge

Clinical Scenarios in Bariatric Surgery: Lesser-Known Complications

Case 1: Omental Abscess After Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

This case involved a 41-year-old woman with an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification score of III and a complex medical history, including severe asthma with prednisolone requiring, on average, two to three hospital admissions per year and dilated cardiomyopathy due to New York Heart Association class III cardiac failure diagnosed when she was 39 years of age. Her left ventricular function improved (ejection fraction, 48%) once a bi-ventricular pacing device and an intracardiac defibrillator were fitted in 2017. Further relevant medical history included obstructive sleep apnea on continuous positive airway pressure ventilation overnight, steroid-induced borderline diabetes mellitus and severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

This patient’s case was discussed at the bariatric multidisciplinary team meetings, assessed in the high-risk anesthetic clinic, and cleared for bariatric surgery by the anesthetic, surgical, dietetic, and psychology teams. In view of her brittle asthma, her prednisolone dosage was increased to 20 mg per day for one week before surgery. She underwent an elective laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) in 2019 by Dr. Khwaja.

Intraoperative findings included the presence of hepatomegaly due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and a very thick greater omentum. The greater omentum was split using the LigaSure device (Medtronic) perpendicular to Szomsts@ccf.org

the transverse colon. A triple-stapled jejunojejunostomy was created followed by the creation of an 8-cm–long lesser curve–based gastric pouch. A circular-stapled gastrojejunal anastomosis was created with the Orvil device (25 mm) (Medtronic), using a 3.8-mm staple height. Both Petersen’s and jejunojejunostomy mesenteric defects were closed with a 15-cm permanent V-lock suture.

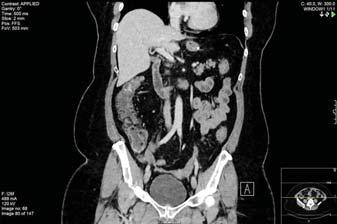

The immediate postoperative course was unremarkable, with the patient spending one night in the highdependency unit, as planned, and then discharged to home from the surgical floor on postoperative day 3. She attended clinic one week later for assessment and was clinically well. At three weeks postoperatively, she attended clinic again, at her request, complaining of epigastric pain; a CT scan done that day showed omental infarction of approximately 10×8 cm (Figure 1). In view of the abdominal pain, she was admitted for analgesia and antibiotics, and she remained on 20 mg of prednisolone for

Case 2: Mesenteric Panniculitis and Bariatric Surgery

This case involved a 56-year-old woman with a BMI of 41 kg/m 2 and medical history of mild asthma, impaired glucose tolerance, sciatica, depression and three cesarean deliveries. She also had non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and a history of excess alcohol consumption. She had been extensively investigated by the hepatology team, and it was believed that she had no significant liver disease. The patient was scheduled for an elective LRYGB.

During surgery, it was noted that she had evidence of extensive mesenteric panniculitis, and the proximal small bowel was adherent to adjacent small-bowel loops as well as to the transverse mesocolon. After a trial dissection, it was determined that there was significant mesenteric panniculitis and jejunitis, and a sleeve gastrectomy was performed, as the patient had been consented for both procedures. She made an uneventful recovery from surgery and was discharged on postoperative day 2.

In view of the surgical findings, a CT scan was performed six weeks after surgery that showed evidence of enterocolitis and mesenteric panniculitis with a well-formed sleeve (Figure 3). The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist for further management. She had no acid reflux and has been enrolled in a five-year endoscopic surveillance program in view of the recent reports of an increased incidence of Barrett’s esophagus in patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy.

Figure 1. CT scan showing an area of omental infarction of approximately 10×8 cm.

Figure 2. CT scan demonstrating some liquefactive necrosis of the infarcted omentum.

her asthma. Her white blood cell count and inflammatory markers failed to improve, and 10 days after this admission, she developed fevers and shivers as well as worsening abdominal pain. A CT scan demonstrated some liquefactive necrosis of the infarcted omentum (Figure 2). This was not amenable to radiological percutaneous drainage, and, in view of her sepsis, the decision was made to perform diagnostic laparoscopy, during which an omental abscess was drained. One hundred milliliters of pus was drained, after which the patient made an

uneventful recovery.

Dr. Fehervari: What made you choose these particular cases for the purpose of this interview?

Dr. Khwaja: Discussions around complications of weight loss surgery are usually focused on bleeding, anastomotic/staple leaks and internal hernias. There is very little in the published literature on omental infarction/abscess after LRYGB or the implications of mesenteric panniculitis in bariatric surgery. Indeed, one of the most obvious problems of patients undergoing bariatric surgery is the extreme amount of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue. This may seem surgically less important, but these cases illustrate that the large amount of fatty tissue itself can lead to significant problems and have implications on the outcome or choice of operation. The first patient had very severe cardiac and respiratory disease, preferred LRYGB over laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), and yet she suffered from a complication perhaps best described as a “disease of the fat.” The second patient had to be converted intraoperatively to LSG due to extensive mesenteric panniculitis.

Dr. Fehervari: In the first case, why did you initially decide on a watchful waiting approach for the omental infarction, and why did you opt for surgery rather than radiological drainage of the omental abscess? Dr. Khwaja: There are multiple ways of dealing with surgical complications. Once the diagnosis of omental infarction was made, a period of conservative treatment with analgesia and antibiotics was instituted based on the few cases in the published literature of omental infarction after gastric bypass. I also consulted my colleagues and used the online platform, the International Bariatric Club, to seek advice from bariatric surgeons globally. According to the sparse publications on this complication in the published literature, most patients responded to conservative treatment. That is why I initially opted for this approach for 10 days. Given that the patient was not responding to conservative treatment and then became septic, and given her history of cardiac failure, I felt intervention was imperative. Initially, I requested interventional radiology to consider draining the abscess, but they felt it would not be effective. As a result, I made the decision to do a diagnostic laparoscopy and drainage of the omental abscess, which was effective and resulted in resolution of the sepsis. I also felt that, in a patient who is immunosuppressed on steroids and with dilated cardiomyopathy, a thorough drainage of the omental abscess was of paramount importance and why I chose the laparoscopic approach.

Dr. Fehervari: You must have appreciated doing an LRYGB on such a patient was a very high-risk surgical option, when many surgeons would have opted for a gastric sleeve, or even a band, especially when the patient was never weaned off prednisolone.

Dr. Khwaja: Indeed, it was a high-risk surgical option, but her case had been discussed on multiple occasions in the bariatric multidisciplinary team, and it was believed that LRYGB would give her the best chance of significant weight loss and improvement in her obesity-related comorbidities, including her GERD. She was also aware of the concerns of Barrett’s esophagus after LSG and did not want that procedure. She was very motivated, adherent to the preoperative liver shrinkage diet, and fully aware of the complications of LRYGB, including bleeding, anastomotic/staple line leak, dumping syndrome, marginal ulcer, gastrojejunal stricture, internal hernia, venous thromboembolism, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, port site hernia/abscess, weight regain, and a mortality rate of 0.3%.

These cases illustrate that the he large amount of fatty tissue e itself can lead to significant problems and have implications on the outcome e or choice of operation. —Haris Khwaja, MD

Dr. Fehervari: Why did you elect to do a fully stapled LRYGB?

Dr. Khwaja: I have performed LRYGB using many different techniques over the past 10 years, including the circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy, linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy, hand-sewn gastrojejunostomy, and a unidirectional-stapled jejunojejunostomy. After having performed all of these different techniques, I found the circular-stapled technique using the 25-mm Orvil device gives a reproducible anastomosis, is quick to perform, and, in my hands, since changing to this technique, I have not had a gastrojejunal stricture in eight years. The triple-stapled jejunojejunostomy gives a wide anastomosis and is quick and easy to perform, even in patients with a very high BMI. There are concerns of a higher incidence of intussusception of the jejunojejunostomy anastomosis with this technique, but to date I have not seen this in my practice. The important issue is the surgeon should be comfortable in his or her technique of performing the anastomoses.

Dr. Fehervari: In the second case, you changed your surgical plan. I am sure it is also something that is difficult for some patients to accept. How do you prepare your patients for something like this?

Dr. Khwaja: I always obtain informed consent from my patients before LRYGB, as well as for LSG. For the two patients discussed in this interview, I explained and cited in my preoperative clinic letter that if we cannot perform a gastric bypass, one option would be to do a sleeve gastrectomy, after explaining in detail the benefits in terms of treating morbid obesity, effects on obesity-related comorbidities, and quality of life and possible complications.

Dr. Fehervari: How about the intraoperative decision making? At what point should a bariatric surgeon consider converting LRYGB to LSG?

Dr. Khwaja: In my opinion, if the small bowel is enveloped by adhesions after a trial dissection and if no significant progress is made to separate the small bowel, I would consider LSG. In most cases, the surgeon is aware that the patient may have a hostile abdomen by the presence of scars from previous surgeries, but in the second case, the patient had no such history except for a cesarean delivery through a Pfannenstiel incision. Of note, the abdominal CT done on the second patient showed colitis, and she is being investigated by a gastroenterologist to exclude inflammatory bowel disease. ■

A Surgeon and His Art

“Busy London Thoroughfare,” a watercolor by Gerald Marks, MD.

A joyful visit to London a decade ago found us walking the streets to visit the sites. Visual treats were everywhere and this no-named intersection with its typical London bustle was an eye-catcher. This watercolor painted from a photo many years later captures the spirit of the moment.