54 minute read

The ‘Holy Grail’ of Lap Chole

Achieving the ‘Holy Grail’ in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

By FREDERICK L. GREENE, MDBy

Rarely does a manuscript get published in our mainstream and peer-reviewed surgical literature that mandates reading by all general surgeons. In my view, the recent and simultaneous publication in Annals of Surgery (2020;272:3-23) and Surgical Endoscopy (2020;34:2827-2855) by the Bile Duct Injury (BDI) Task Force achieves this benchmark.

This monumental effort, launched in 2014 with the establishment of the Safe Cholecystectomy Task Force by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, led by Michael Brunt and his colleagues, reflects a multiorganizational Delphi approach to reduce the rate of BDI as a consequence of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. After working six years and poring over multiple studies, studying innumerable databases and hosting an in-person consensus conference in 2018, this group has brought its recommendations to the mainstream surgical community.

Since management of gallbladder disease is one of the most common surgical forays for both general surgical trainees and practicing general surgeons, the findings of this task force require study, reflection and embracing by all of us. With 750,000 to 1 million cholecystectomies performed yearly in the United States, the BDI rate, estimated to be between 0.15% and 0.3%, translates to 2,300 to 3,000 BDIs per year! Hopefully most of our readership have been fortunate to avoid any association with this demoralizing outcome. For others, the acute and longterm consequences for both patient and surgeon are devastating. The BDI task force has valiantly attempted to extrapolate administrative database information and literature reviews in making 18 recommendations for creating a safer environment for patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The authors are quick to point out that recommendations based solely on solid data may be ephemeral. This caution, however, does not diminish the import of well-thought-out recommendations from a cadre of experts.

One of the weaknesses in considering these strategies of data collection is the problem is always bigger than you think. We are constantly reminded of this phenomenon during the current COVID19 pandemic; there are always more infections than are extrapolated from existing testing data and hospital admissions. In considering BDI, many cases go unreported which leads to underreporting in global calculations. The task force authors share their own frustrations in that after 30 years of performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, there is still no national registry capturing BDI data. Unfortunately, there never will be.

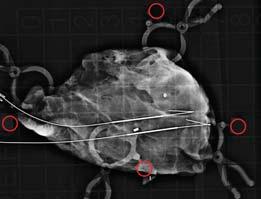

I was pleased that the task force embraced one of the strategies that I used beginning in 1990, and have been privileged to teach to surgical residents: intraoperative cholecystectomy (IOC). While

not guaranteeing a completely safe dissection and subsequent avoidance of injury, IOC is touted by the task force as being a vital strategy that will help mitigate injury. Unfortunately, I fear that in most surgical training programs, the will and the interest to teach IOC by a preponderance of clinical surgeons is waning. It is my fervent hope that our current leaders in academic training programs will embrace the concepts of both utilization of the “critical view of safety” and IOC as promoted by the task force.

As I began, this seminal report for the mitigation of BDI should be mandatory reading for every practicing surgeon and surgical trainee. We will never fully avoid the devastation of this consequence in the performance of modern cholecystectomy. However, it is our duty to our patients and ourselves to ponder critically the outcomes over the past 30 years as we pursue the “grail” in our endeavor to achieve optimal safety. ■

—Dr. Greene is a surgeon in Charlotte, N.C.

L

S

I

Behind the Tough Decisions on Meetings During COVID-19

continued from page 1

about 200 of them,” Dr. Dietz said. “We didn’t want people who worked so hard to lose the opportunity to present their research, much of which will be obsolete by next year.”

The ASBrS decided to freeze the meeting, including the board and presidency, until next year and to hold a virtual education series that started in May; members could tune in to the sessions in real time, or view them later on the society website. More than half of the content is eligible for continuing medical education (CME) credit.

Choosing Content

The ASBrS needed only a few weeks to determine what to include in the series. “I wouldn’t say it was a no-brainer, but a lot of our content was chosen in response to what our members need,” Dr. Dietz said.

Content falls into two categories: items that probably will not be relevant a year from now, such as scientific research, and guidance for patient care during the pandemic.

“For example, when we have to delay surgery, many surgeons put their breast cancer patients on endocrine therapy; so we held a virtual session on that topic,” Dr. Dietz said.

Dr. Dietz will not be doing her presidential address virtually, but plans to deliver it next year. She anticipates the theme she planned for the 2020 ‘We didn’t want to burden our members, many of whom are taking pay cuts, or our industry partners, who need the faceto-face interaction they get in the exhibit hall. So we tried to come up with some creative solutions.’ —Jill Dietz, MD

meeting—value and the patient experience—will continue to be relevant in 2021.

“I think we’ll still be reeling from the effects of COVID-19, but I also think this will remain a pertinent topic because the pandemic, in a weird way, has catapulted us toward efficiency of care.”

The technology aspect has been surprisingly easy, Dr. Dietz said. The society purchased a Zoom platform that allows up to 1,000 participants. The chat function has enabled moderators to respond quickly to comments and questions. “It’s almost seamless,” Dr. Dietz said. Glitches have been minor—a speaker forgets to unmute or a video doesn’t run.

The ASBrS was able to void its contract with the meeting site by invoking the force majeure clause, but the economic fallout has still been sizable. The society refunded all member registration fees and lost most if not all of their industry support.

“We didn’t want to burden our members, many of whom are taking pay cuts, or our industry partners, who need the face-to-face interaction they get in the exhibit hall. So we tried to come up with some creative solutions,” Dr. Dietz said.

They set up a virtual exhibit hall, promoted on the virtual meeting’s webpage, and hosted several industry-sponsored symposia. Like at the annual meeting, these sessions didn’t offer CME credit. “But so far they’ve had pretty high attendance,” Dr. Dietz said, in an interview at the time of the ASBrS virtual meeting.

She believes this experience will forever change the ASBrS, stepping up the use of virtual resources to meet member needs. “But we also hear loudly and clearly how much everyone loves the annual meeting. If there’s a way to do it safely in 2021, we will.”

When the Meeting Is a Moving Target

As early as late February, meeting directors for the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) began receiving cancellations,

continued from page 1

likely an example of an oral tradition. Ancient generations painstakingly transmitted historical and cultural elements through the heroic tales of gods and men. Thankfully, too, because between the blurred lines of fact and fiction we understand how they perceived life, love and loss. Thousands of years later, that emotional energy is still preserved.

By now, the newest surgery interns are on the wards and in operating rooms. To all of you, welcome. You probably feel overwhelmed and underappreciated, and if not now, then soon. The sheer number of tasks you need to complete in the course of a day will inevitably give you tunnel vision. To a degree, this is expected. But as you become more efficient, there will be opportunities to look up and observe your surroundings. The lesson, then, is to become efficient early so as not to miss anything—your patient’s nervous ent s nervous smile, the family’s concern, a kind ern, a kind gesture from an attentive nurse, the e nurse, the questioning looks of a new medical student. w medical student. These are some of the human connections that man connections that will help sustain you through residency. ugh residency.

There is another piece of a surgical intern’s of a surgical intern’s education that too often goes unnoticed: the oes unnoticed: the stories. Beginning in your first academic r first academic conference, you will hear stories, dripping stories, dripping in nostalgia and embellished with time, hed with time, offered up and passed around around like feats of war. Try to clear ear the noise and listen to this coordinated performance as it crescendos in victory, decrescendos in disappointment, now with layers of harmony and dissonance from around the room—stories of surgery.

By this point, I have heard ard all of my attending’s stories at es at least three or four times. I I can nearly predict the story y based on the discussion:

Being a chief and walking g the junior through the first half of a Whipple … Working two and three days straight … Standing on thick rubber mats in OR while using cyclopropane as an anesthetic … Evacuating a hematoma bedside after thyroid surgery … Extinguishing an OR fire during a tracheostomy … Putting a patient on cardiopulmonary bypass to repair a tracheal laceration …

I can even retell stories that were told by my mentor’s mentor. The care given to preserve these multigenerational stories is almost reverent. Be a part of that ceremony. Let yourself be transported back to that OR in 1981, where a newly minted chief struggles through a laparotomy in the middle of the night, or where a young surgeon is forced to make hard choices out of a tent in Afghanistan. The stories—big and small—are full of triumphs and failures,

The stories—big The st and small—are full andsma of triumphs and failures, of triumphs an humor, wisdom and humor, w creativity. But they creativity are not fantastic fables. are not fantas The stories have a first and The stories have last name, and for the senior last name, and for attendings, these are the attendings, the events that shaped events th their careers. the

humor, wisdom and creativity. But they are not fantastic fables. The stories have a first and last name, and for the senior attendings, these are the events that shaped their careers.

To the July interns, you may be surprised to hear that surgeons are storytellers. We learn how to do it from day 1. Even more surprising is that a good portion of your first year will be consumed with how well you tell a story at the podium (think history and physical). To this end, every part of the story will be under a microscope. Each morning you will be corrected on the length, vocabulary, syntax, order and conclusion of your story, but I would argue that it is as much a skill as learning to throw a perfect square knot. Dedicate time to this skill and it will serve you well.

Even though surgery is and always will be an oral tradition, we strive to elevate surgical decision making above the level of anecdotal experience. Modern surgery exists as both an art and a science. The adoption of evidence-based medicine does not render the stories obsolete; rather, every question answered by statistics originally began as a story and they have been the impetus for change, not data. And the surgical texts that interns will pore over in just a few weeks—are they not reminiscent of Homer, seamlessly jumping between fact (evidence-based) and fiction (dogma)? Despite having undisputed authorship, each chapter is the accumulation of our collective experience, reproduced and passed down from surgeon to surgeon. And so to the new interns: Listen to the stories. After all, they are for you, to internalize and learn from.

They are your history.

“It is Surgery that, long after it has passed into obsolescence, will be remembered as the glory of Medicine. Then men shall gather in mead halls and sing of that ancient time when surgeons, like gods, walked among the human race.”

—Richard Selzer, “Letters to a Young Doctor” (1982)

—Dr. Halgas is a surgical resident in El Paso, Texas. His column on surgical residency appears every other month.

Meetings

continued from the previous page

mostly from international attendees and exhibitors but also some domestic ones. By the first week of March, it was clear the society could not hold the meeting in early April as planned, and postponed it until August.

“So much of the value of SAGES is in the networking and fellowship. We had little interest in conducting the meeting online and no interest in canceling it,” said Sallie Matthews, the executive director of SAGES.

“Based on what we knew about COVID-19 at the time, we thought August would be safe and responsible.”

Industry sponsors proved good partners, collaborating on numerous statements and webinars related to the pandemic. Cleveland’s convention center and hotels were very cooperative and eager to rebook the meeting for August. “They were the best partners we could have hoped for.”

At the end of May, however, Ms. Matthews and her colleagues revised their stance on a virtual meeting, and shifted to an online platform. “It became clear that we could not safely or responsibly hold the in-person meeting in August.”

The virtual meeting will contain much of the same content as the originally scheduled—and rescheduled—meeting, with the presidential address, keynote speakers and other popular SAGES features. “We’ve made our hands-on courses virtual in a unique and exciting way that could be useful in the future, even after COVID.”

When the Show Just Can’t Go On

A combination of timing, travel bans and COVID-19 demands drove directors of the Surgical Infection Society’s (SIS) meeting to cancel their event.

“Our meeting was very early in the pandemic, and there was no precedent for any society in terms of finding an alternative,” said Philip S. Barie, MD, MBA, the executive director of the SIS Foundation for Education and Research.

Furthermore, many SIS members are acute care surgeons, managing trauma, emergency general surgery and ICUs. The society anticipated, correctly, that its members would be fully occupied dealing with COVID-19 patients.

“Honestly, no one had the bandwidth to pivot to a virtual meeting at that point,” said Dr. Barie, a professor of surgery and public health in medicine and an attending surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, in New York City.

The society is hopeful that it will be able to hold its traditional meeting next year, scheduled for June. But the society has the technology in place to conduct a virtual meeting, if need be.

In the meantime, SIS has invested in webinar technology and redoubled guideline-writing activities to continue to serve its membership.

“The work goes on apace,” Dr. Barie said. “We have some strong work by committees stepping up to increase our output so we can maintain the value proposition for our membership.” ■

EXTENDED HERNIA COVERAGE 2020

August 2020

Our Health Care Tragedy of the Commons

Americas Hernia Society Presidential Message

Most Incisional Hernia Readmissions Occur After 30-Day Benchmark

Scale of Untracked Complications Potentially Enormous; Investigators Recommend Extension of Tracking Period

By CHRISTINA FRANGOU

One of every five patients who underwent an incisional hernia repair in the United States was readmitted to the hospital within a year, with most readmissions occurring after the 30-day benchmark commonly used to track health care utilization, according to a new study of hospital admissions between 2010 and 2014.

Additionally, one-fourth of readmitted patients did not return to the same hospital where they were operated on, making their complications and readmissions even harder to track in most databases.

The analysis, published in the Journal of Surgical Research, indicates many patients who are readmitted

continued on page 15

More Than 30 Years of Inguinal Hernia Surgery: Have We Moved the Needle?

By GUY VOELLER, MD

Having been in the practice of general surgery in the same location for more than 30 years allows one a perspective on hernia surgery that may or may not be noteworthy. When I was asked by Dr. Benjamin Poulose, the president of the Americas Hernia Society, to scribble a few thoughts, I felt it might be interesting to see how things have changed (if at all) in inguinal hernia surgery over these 30 years. It also gives me a chance to talk about the history of hernia repair, which is one of my favorite topics since we surgeons owe everything to those who went before us.

When I was training as a resident in the early 1980s, the most common autogenous repair was the McVay, or Cooper’s ligament repair. This procedure was based on the superb work of surgeon Chester McVay and anatomist Barry Anson. I encourage surgeons to read about this repair. While originally described by Narath in Holland and Lotheissen, it was the paper in 1960, based on the dissection of 500 cadavers by Anson and McVay, that popularized this repair (Surg Gynecol Obstet 1960;111:707-725). Since there was tension on the repair, a relaxing incision was done in the rectus sheath to relieve it.

Another common autogenous repair at this time was what I call the North American “modification” of the Bassini repair. Modern hernia surgery was ushered in by Dr. Edoardo Bassini with his “radical cure of inguinal hernia,” a technique on which he published in 1887. This elegant operation, on which the Shouldice repair is based, reconstructs

By BENJAMIN K. POULOSE, MD, MPH

Originally, this message was going to highlight the accomplishments of the Americas Hernia Society. These successes have been achieved through programs such as the newly christened Abdominal Core Health Quality Collaborative (achqc.org), “Stop the Bulge” campaign, Safe Hernia Steps, and the new WiSE (Web information, Social media, and Education) initiative that aim to make americasherniasociety.org the leading educational resource on hernia and abdominal wall disease. We look to shape the future identity of our field, breaking down traditional ways of thinking with the concept of Abdominal Core Health (abdominalcorehealth.org).

But this all changed with COVID-19.

Our practices were upended by the pandemic, and we retooled to accommodate the influx of COVID-19 patients and limit the spread of the disease. While resuming elective operations, the pandemic continues to rage with much uncertainty. As with many upheavals, the “return to normal” may never happen, yet positive meaning can emerge that leads to a better society.

With my practice on hold, I read “Proofiness: The Dark Art of Mathematical Deception,” by Charles Seife. One particular story resonated with the COVID-19 situation and health care: the “Tragedy of the Commons.” Originally described by British economist William Forester Lloyd in 1883, the “Tragedy of the Commons” describes a hypothetical situation that assumes individuals (i.e., people, corporations, health care systems) generally behave according to their own self-interest, contrary to the common good. This occurs when we are numb to the costs or negative consequences of the choice. Lloyd describes the unregulated grazing of cattle on shared land, “the commons.” Initially, the cattle owners have great benefit—large amounts of grazing land at seemingly no cost. This is sustainable for a while, until the commons can no longer

continued on page 24

IN THIS ISSUE

14 Update on the AHS Quality Collaborative

16 Surgical Subspecialty Societies: Expanding Knowledge, Staying Connected

16 Quantity Over Quality: It’s Time to Up Our Game

Recent Top Hernia Stories in General Surgery News: A Recap

Randomized Trial Pits Laparoscopy Against Robot-Assisted for Ventral Hernia

Short-Term Results Suggest No Advantage With Robotic Approach, Including Length of Stay

Geriatric Patients See Similar Outcomes After Lap Hernia Repair

By CHRISTINA FRANGOU

In the first randomized controlled trial to compare robotic ventral hernia repair and laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, no benefit was found for the robotic approach. On several key indicators, robotic ventral hernia repair failed to match outcomes associated with the laparoscopic procedure.

Compared with laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, robotic ventral hernia repair did not decrease postoperative length of stay. It doubled OR time, increased estimated costs, and did not improve short-term patient-centered outcomes.

The findings come from a trial of 124 patients randomly assigned to RVHR or LVHR at the time of the procedure.

“There does not appear to be a benefit across multiple important outcomes for ventral hernias repaired robotically,” said co-author Oscar Olavarria, MD, a surgery resident with McGovern Medical School at UTHealth, in Houston.

Over the past decade, more and more general surgeons have started using the robot, but the robot’s popularity has outpaced the scientific literature. Prior to this study, no randomized controlled trials compared RVHR with LVHR.

The trial was conducted at two hospitals in Houston between April 2018 and February 2019. In that time, 65 patients underwent RVHR and 59 had LVHR. Patients were followed for a median of 6.4 months after surgery.

The three surgeons participating in the trial perform more than 100 hernia repairs annually.

Analysis showed the following: • Median LOS in both groups was zero days. • Operating times for RVHR were nearly twice as long, at 141 versus 77 minutes (P<0.01). • RVHR was associated with more enterotomies (3% vs. 0%; P=0.996). • At one-month follow-up, patients who underwent LVHR had a greater improvement in median abdominal wall quality of life (AW

QOL) scores (15 vs. 3; P=0.060). • Health care costs were higher for RVHR, at $15,864, compared with $12,954 (P=0.004) without accounting for acquisition and service contracts of the robotic platform. • A Bayesian analysis showed RVHR had a 78% probability of being associated with more enterotomies, and LVHR had a 66% probability of having greater improvement in early postoperative quality of life.

Dr. Olavarria said investigators believe robotic platforms will eventually replace traditional laparoscopic and open surgery.

“The key message is that it is important to rigorously evaluate innovations in surgery, including the use of robotic platforms, given that the perceived benefits may not be borne out,” he said.

[Originally published in the December 2019 issue.]

By MONICA J. SMITH

Geriatric patients who undergo laparoscopic ventral hernia repair tend to have more comorbidities and larger hernias than younger patients, but their outcomes and quality of life may be similar to those of younger patients, research indicates.

“Laparoscopy has been shown to improve morbidity and postoperative recovery in many patient populations. Furthermore, laparoscopic ventral hernia repair has been shown to decrease wound complications and shorten length of stay. But there’s minimal data for LVHR in the geriatric population,” said Sharbel Elhage, MD, a general surgery resident physician at Atrium Health’s Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C.

To evaluate postoperative outcomes and QOL after LVHR in geriatric patients, Dr. Elhage and his colleagues queried their institution’s prospectively enrolled database for all patients undergoing LVHR and divided them into three groups: patients under 40 years of age, patients between 40 and 64, and patients 65 and older. They used the Carolinas Comfort Scale to measure QOL, choosing a score of 2 (mild but bothersome) as indicative of nonideal QOL.

Nearly 1,200 patients met the inclusion criteria. “As expected, the geriatric group had higher rates of nearly all comorbidities, including pulmonary, cardiac and diabetes; body mass index was higher in the younger population,” Dr. Elhage said. The older population also had larger defects, but their number of prior recurrences was similar to that of the younger cohorts.

The hernia-specific outcomes were similar among the three cohorts, with the exception of seroma requiring intervention, which was slightly higher in the geriatric group. Recurrence, too, was similar among all groups, at 5.7% with a mean followup of 44 months.

The team assessed pain, mesh sensation, activity limitation and overall QOL at two weeks, one month, six months and 12 months. They found mesh sensation similar among the three groups. [Originally published in the May 2020 issue.]

Primary Fascial Closure With Lap Hernia Repair Supported by Study

By CHRISTINA FRANGOU

Patients who have a primary fascial closure before mesh placement during laparoscopic ventral hernia repair enjoy better long-term quality of life than those who undergo a standard bridged repair, according to results from a multicenter, randomized controlled trial.

“This study provides the high-quality evidence that primary fascial closure significantly improves patients’ quality of life and function,” said lead author Karla Bernardi, MD, a researcher with McGovern Medical School at UTHealth, in Houston.

The investigators now recommend patients with hernia defects greater than 3 cm do not have a bridged repair.

“Among patients undergoing elective LVHR, the fascial defect should be closed,” Dr. Bernardi said.

Between 2015 and 2017, 129 patients were randomized to undergo PFC or a bridged repair during an elective LVHR at four institutions in the United States. All patients had hernia defects between 3 and 12 cm on CT; most were obese, had one or more comorbid conditions, and had prior abdominal surgery.

Before surgery, all patients completed the modified Activity Assessment Scale (mAAS), a validated hernia-specific, QOL survey that measures pain, function, cosmesis and satisfaction. Scores range between 1 (very poor) and 100 (perfect).

During each operation, just before mesh placement, the surgeon called the randomization office to determine the next step of the procedure, based on a computer-generated variable block randomization.

For patients in the PFC arm, the fascia was closed using a percutaneous technique. Small stab incisions were made along the long axis of the hernia defect, and 0-polydioxanone sutures were placed every 1 cm. For both groups, the mesh was then secured with four 0-polydioxanone positioning sutures and tacked with a double crown of permanent tacks.

Of the 129 patients enrolled in the trial, 107 (83%) completed a QOL survey two years after surgery.

Results showed the following: • Patients in both arms reported significantly improved

QOL after repair, but the PFC group experienced a 12-point greater improvement (41.3±31.5 vs. 29.7±28.7; P=0.047). • Patients who had PFC experienced greater improvements in their ability to carry out physical activities than those in the bridged repair arm, based on subsets of the mAAS scores. • There was no significant difference in chronic pain or pain scores after treatment based on mAAS scores. • There was no difference in clinical outcomes with

PFC compared with bridged repair. • Operations with PFC took, on average, 13 minutes longer.

Disclosures: Dr. Bernardi’s co-authors Dr. J.S. Roth received associate research funding from Davol Inc. and Intuitive Surgical, and Dr. S. Tsuda received compensation from Allergan. This funding was not used for this project.

Transforming Care for Hernia Patients Through Collaboration

An Update on the AHS Quality Collaborative

By MICHAEL J. ROSEN, MD

On behalf of the entire Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative, I’d like to share with you some of our key accomplishments and updates on how we are transforming our knowledge of hernia repair and improving patients’ outcomes through the principles of collaborative learning. All of our stakeholders, including our patients, surgeons, FDA colleagues and Foundation partners share our vision and continue to invest their time and resources in support of this national effort to advance the quality of hernia repair. What we have accomplished since 2013 is truly inspiring, and I hope many others will join this effort as we are really just getting started.

The quality collaborative, or AHSQC, continues to grow, with increasing numbers of surgeon participants and procedures captured. Through collaboration among our stakeholders, the AHSQC uses continuous quality improvement methods and a systematic, userfriendly, patient-centric approach to streamline realworld data collection from hernia and abdominal wall procedures. Our process allows for systematic collection of clinically relevant information, including pre-, intra- and postoperative details during the routine care of patients that can be critically analyzed to identify areas where patient outcomes may be enhanced. We share this information widely via multiple avenues and across a range of platforms to maximize our direct impact on hernia patient care.

We have expanded our focus to represent the complexity of diseases of the abdominal wall and treatment of abdominal core health and now track outcomes of primary, incisional, parastomal, inguinal and rectus diastasis repairs, management of chronic groin pain, and abdominal wall oncology. These operations include routine hernia repairs up to some of the most complex reconstructive challenges surgeons face. Recognizing the magnitude of approaches to hernia repair, we collect granular information on key surgical techniques, and approaches including open, laparoscopic and robotic repairs. These data will enable us to understand the specific merits of all of these options and use them in the most appropriate patients to optimize results. Our ranks now include over 400 surgeons across the United States who collectively donate thousands of hours to the AHSQC each year. These surgeons represent a diverse practice group that includes solo private practice surgeons to large group practices in academic institutions. With a nearly even representation of private practice and academic surgeons, we continue to obtain real-world outcomes that are relevant to all stakeholders. Thanks to these dedicated surgeons, the AHSQC registry surpassed 60,000 patients this year and we have seen linear growth since our inception.

With patients at the core of the AHSQC’s mission, we continually strive to understand and improve their experiences—before, during and after surgery. This year the AHSQC took several opportunities to team up with health care providers in other disciplines, extending our collaborative reach focusing on abdominal core health. Surgeons with the AHSQC forged dynamic interrelationships with colleagues specializing in pain management, anesthesiology, physical therapy, occupational therapy, nursing and rehabilitation services, and jointly created several interactive and engaging tools for patients and their care providers. These innovations include our AHSQC mobile app, Abdominal Core Surgery Patient and Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Guides, and informational handouts to educate patients on the risk of opioids and offer alternative pain management options following hernia surgery. All of these resources are available for free download on our website (www.ahsqc.org). We recently launched our free AHSQC app, which is available in iOS and Android formats. The app is designed to improve the outcomes of patients undergoing abdominal and hernia surgery, offering recommendations for self-directed prehabilitation efforts and physical therapy guidance during their postoperative stay and at subsequent two-week intervals. These efforts focus on core strength and early activity aimed at reducing complications and improving outcomes.

With the opioid epidemic continuing to plague the United States, the AHSQC is committed to using our collaborative network to identify actionable measures to confront this national crisis. Under the guidance of our opioid reduction task force lead, Dr. Micki Reinhorn, we have created a patient-friendly document with guidelines and alternative approaches to treating early postoperative pain after hernia surgery (www.ahsqc.org/patients/opioid-reduction-initiative). Two key aspects of this initiative involve surgeons limiting their postoperative opioid prescription to no or up to 10 tablets following inguinal and umbilical hernia surgery, and incorporating a multimodal, nonopioid pain management strategy as a firstline approach with opioids used as a “rescue” medication. As a collaborative, we have already seen substantial reductions in narcotic prescriptions. We know that providing these tools to patients can help play a tremendous role in enhancing surgical outcomes. Patients who are engaged and educated ultimately become more informed decision makers, who we hope feel more empowered to talk with their care providers and take a more active role in the management of their individual care.

The AHSQC continues to be a preeminent source of high-quality, comprehensive and clinically relevant information on hernia surgery. We continue to relentlessly search for data-driven answers to questions about our treatment of hernia patients in order to optimize outcomes. The bibliography of peer-reviewed publications using AHSQC data analyses has now reached 45, with 19 new articles published in high-impact journals over the past 18 months. A highlight of these works includes our first utilization of the registry to perform postmarketing surveillance by engaging all stakeholders. Additionally, our collaborative has successfully advanced high-quality research in the field of hernia surgery by focusing our efforts on conducting embedded randomized studies within the AHSQC. These efforts will likely reshape the practice of hernia surgery through evidence-based medicine.

Many registries focus solely on data collection, but at the AHSQC, we are actively engaged in the operational arm of quality improvement and improving outcomes through collaborative learning. Building on the success of 2018’s inaugural Quality Improvement Summit, we closed 2019 by hosting our second QI Summit, “A Collaborative Approach to Improving the Hernia Patient Experience—Spotlight on Optimizing Umbilical Hernia Repair,” in December. The meeting facilitated networking with peers and collaborative learning during interactive sessions. Attendees discussed approaches to continually improve techniques with high-performing colleagues and considered best practice suggestions to implement upon returning home. I’m excited to share that plans for the next QI Summit are already underway.

Recognizing the critical role of regulating medical devices in the hernia space, we continue to forge relationships at the federal level. The AHSQC helps direct the FDA’s MDEpiNet Abdominal Core Health Coordinated Registry Network, which has made significant progress in developing unique methods to enhance postmarketing surveillance. MDEpiNet is a global public‒private partnership that brings together leadership, expertise and resources from health care professionals, industry, patient groups, payors, academia and government to advance a national patient-centered medical device evaluation and surveillance system. Through these efforts, we are confident we will be able to build a better system to offer our patients the best possible outcomes in a safe and innovative environment. The AHSQC continues to be recognized by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as a merit-based incentive payment system (or MIPS) qualified clinical data registry and by the American Board of Surgery to fulfill Part 4 of the Maintenance of Certification program.

The AHSQC has seen tremendous growth in service to our community of patients, surgeons, care teams and partners. While celebrating our past successes and overcoming challenges, we recognize that our future depends on new ways of thinking about focusing on health and not dwelling on disease. The concept of abdominal core health leads this innovation by exploring the relationships between the abdominal wall, diaphragm, pelvic floor and lower back. Critical to this effort will be gathering high-quality data in hernia disease and beyond. To this end, the AHSQC has evolved into a more comprehensive organization incorporating the multidisciplinary teamwork that is inherent to caring for patients with abdominal core problems, and has renamed itself the Abdominal Core Health Quality Collaborative— ACHQC. With this new distinction, we believe we will increase our collaborative network and improve outcomes further. We enter the new decade energized and fully committed to our mission as an exciting, refreshed “QC.” We welcome you to join us! ■

—Dr. Rosen is the medical director of the ACHQC and director of the Cleveland Clinic Center for Abdominal Core Health, Cleveland, Ohio.

Disclosure: Dr. Rosen reported salary support for his role as the medical director of the ACHQC. His institution has received grant support for principal investigator roles in trials with Intuitive and Pacira.

Incisional Hernia Readmission continued from page 11 Estimated Costs of Readmission For Incisional Hernia Reoperations were performed in 35% of readmitted patients and 5% had revisions to their repair. with complications following incisionComplications were the leading Annual cost of unplanned readmissions: The results highlight the need for al hernia repair are overlooked, leadcause of readmission, accounting for $90+ million per year national policies that require physiing to consistent underreporting of 50%, with half of them due to infeccians to follow patients and collect data complications. tious complications. Of all patients Predicted mean difference beyond 30 days, the investigators said. “Patients, and some clinicians, may not be aware of how prevalent readmissions are after incisional hernia repair and that most readmissions are related to postopreadmitted for infection, 91.8% were initially discharged within a record to indicate infection. Readmission for bowel obstruction was found in in cumulative costs: $12,189.70 higher for patients readmitted within one year Most data on health care utilization after incisional hernia repair are only carried out to 30 days after surgery and are not nationally representative. erative complications,” said study author 5% of patients, which is higher than Predicted mean difference in length of stay: Dr. Rios-Diaz and his colleagues Arturo J. Rios-Diaz, a fourth-year genpreviously reported rates and may be 6.1 days longer for patients believe the readmission benchmark eral surgery resident at Thomas Jefferson explained by the broad definition used readmitted within one year for incisional hernia repair should be University, in Philadelphia. by investigators. continued on page 23

Many of the readmitted patients required substantial treatment. Onethird of them underwent a subsequent major procedure during their return stay and 4.1% experienced a recurrence requiring an inpatient revision of their repair.

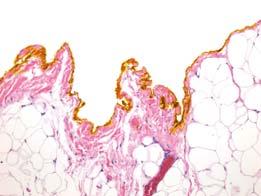

The study confirmed what some surgeons and patients have long suspected: Many complications and events related to quality of care in hernia, especialIn complex hernia repair, patient risk ly ventral hernia, occur well beyond the factors and postoperative wound 30-day postoperative time point, said complications can contribute to the Benjamin Poulose, MD, a professor of peril of hernia recurrence surgery at the Ohio State University, in Columbus. This is especially important given that surgeons implant meshes in patients, expecting them to stay in place for years.

“This should be another wake-up call—not only to hernia surgeons, but also to hospitals, payors and those funding quality improvement and research efforts,” Dr. Poulose said. S T R A T T I C E™ R T M, A 100% BIOLOGIC MESH, In a recent retrospective evaluation of biologic meshes, 91.7 % With more than 350,000 incisional hernia repairs performed in the United States annually, the scale of overlooked complications is potentially enormous, for abdominal wall reconstruction based on the long-term outcomes of low hernia recurrence rates IS A DURABLE SOLUTION post-op 1, * 7 YEARS of patients were RECURRENCE-FREE AT with tens of thousands of patients requiracross multiple published clinical studies 1-5 *Includes porcine and bovine acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) (n = 157). ing readmission for infections more than Bridged repair and human ADM were excluded from the study group. 30 days after surgery.

There is too little understanding in the TO LEARN MORE ABOUT STRATTICE™ RTM, field about why, how and in whom comSPEAK TO YOUR ALLERGAN REPRESENTATIVE plications are occurring long term, and these uncertainties are driving massive legal actions in hernia repair, Dr. Poulose INDICATIONS STRATTICE™ Reconstructive Tissue Matrix (RTM), STRATTICE™ RTM Perforated, STRATTICE™ RTM Extra Thick, This increases risk of patient-to-patient contamination and subsequent infection. contamination levels at the surgical site, including, but not limited to, appropriate drainage, debridement, negative said. “We, as surgeons, can no longer just accept the status quo.” Surgeons should follow their patients long term and develop targeted strategies to reduce complications, including appropriate patient selection, prehabilitation when needed, and good surgical judgment during the performance of the procedure, he said. The researchers used the Nationwide Readmissions Database to study readmission rates of patients who underwent elective incisional hernia repair between 2010 and 2014. In that period, 15,935 patients underwent incisional hernia repair and 19.35% were readmitand STRATTICE™ RTM Laparoscopic are intended for use as soft tissue patches to reinforce soft tissue where weakness exists and for the surgical repair of damaged or ruptured soft tissue membranes. Indications for use of these products include the repair of hernias and/or body wall defects which require the use of reinforcing or bridging material to obtain the desired surgical outcome. STRATTICE™ RTM Laparoscopic is indicated for such uses in open or laparoscopic procedures. These products are supplied sterile and are intended for single patient one-time use only. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION CONTRAINDICATIONS These products should not be used in patients with a known sensitivity to porcine ma terial and/or Polysorbate 20. WARNINGS Do not resterilize. Discard all open and unused portions of these devices. Do not use if the package is opened or damaged. Do not use if seal is broken or compromised. After use, handle and dispose of all unused product and packaging in accordance with accepted medical practice and applicable local, state, and federal laws and regulations. Do not reuse once the surgical mesh has been removed from the packaging and/or is in contact with a patient. F or STRATTICE™ RTM Extra Thick, do not use if the temperature monitoring device does not display “OK.” PRECAUTIONS Discard these products if mishandling has caused possible dama ge or contamination, or the products are past their expiration date. Ensure these products are placed in a sterile basin and covered with room temperature sterile saline or room temperature sterile lactated Ringer’s solution for a minimum of 2 minutes prior to implantation in the body. Place these products in maximum possible contact with healthy, well-vascularized tissue to promote cell ingrowth and tissue remodeling. These products should be hydrated and moist when the package is opened. If the surgical mesh is dry, do not use. Certain considerations should be used when performing surgical procedures using a surgical mesh product. Consider the risk/ benefit balance of use in patients with significant co-morbidities; including but not limited to, obesity, smoking, diabetes, immunosuppression, malnourishment, poor tissue oxygenation (such as COPD), and pre- or post-operative radiation. Bioburden-reducing techniques should be utilized in significantly contaminated or infected cases to minimize pressure therapy, and/or antimicrobial therapy prior and in addition to implantation of the surgical mesh. In large abdominal wall defect cases where midline fascial closure cannot be obtained, with or without separation of components techniques, utilization of the surgical mesh in a bridged fashion is associated with a higher risk of hernia recurrence than when used to reinforce fascial closure. For STRATTICE™ RTM Perforated, if a tissue punch-out piece is visible, remove using aseptic technique before implantation. For STRATTICE™ RTM Laparoscopic, refrain from using excessive force if inserting the mesh through the trocar. STRATTICE™ RTM, STRATTICE™ RTM Perforated, STRATTICE™ RTM Extra Thick, and STRATTICE™ RTM Laparoscopic are available by prescription only. For more information, please see the Instructions for Use (IFU) for all STRATTICE™ RTM products available at www .allergan.com/StratticeIFU or call 1.800.678.1605. To report an adverse reaction, please call Allergan at 1.800.367.5737. For more information, please call Allergan Customer Service at 1.800.367.5737, or visit www.StratticeTissueMatrix.com/hcp. ted within one year. Only 39.3% of readReferences: 1. Garvey PB, Giordano SA, Baumann DP, Liu J, Butler CE. Long-term outcomes after abdominal wall reconstruction with acellular dermal matrix. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(3):341-350. 2. Golla D, Russo CC. Outcomes missions happened in the first 30 days following placement of non-cross-linked porcine-derived acellular dermal matrix in complex ventral hernia repair. Int Surg. 2014;99(3):235-240. 3. Liang MK, Berger RL, Nguyen MT, Hicks SC, Li LT, Leong M. Outcomes with porcine acellular dermal matrix versus synthetic mesh and suture in complicated open ventral hernia repair. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014;15(5):506-512. 4. Booth JH, Garvey PB, Baumann DP, et al. Primary fascial closure with mesh after surgery. reinforcement is superior to bridged mesh repair for abdominal wall reconstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(6):999-1009. 5. Richmond B, Ubert A, Judhan R, et al. Component separation with porcine acellular dermal reinforcement is superior to traditional bridged mesh repairs in the open repair of significant midline ventral hernia defects. Am Surg. 2014;80(8):725-731.

By REBECCA PETERSEN, MD, MSc

This issue of General Surgery News is dedicated to a condition in which the chief responsibility for diagnosis and management rests squarely with the general surgeon, namely hernias. Yet, in the broader discipline of general surgery, several highly functioning and productive subspecialty professional societies have developed: the European Hernia Society, Americas Hernia Society (AHS), Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative, and American Foregut Society (AFS). These societies coexist with another society that many might also consider a subspecialty society, the Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES), which also coexists with larger professional societies such as the American College of Surgeons, Society of University Surgeons, and American Surgical Association.

For a surgeon in a busy practice, the temptations may be to ask: 1) are there too many societies, and 2) how am I to keep up with the information generated By AJITA S. PRABHU, MD A current search of the term “hernia” in the PubMed database reveals 94,144 articles, the first of which was published in 1785. Yet curiously, operations for hernia repair across the United States— and, indeed, around the world—remain woefully inconsistent not only in their technical approach, but also in expected outcomes. In an environment where reducing variability in the delivery of care is the linchpin to securing reproducible and quality health care outcomes, our vast literature has yet to produce the answers we seek. How is it that we have published so much and at the same time learned so little about this ever-present and common disease? Without question, hernia disease is complicated by its own inherent variability, which is further compounded by the specific clinical scenario of each patient. Remarkably, the first challenge occurs here, from the utterance of the word “hernia,” with our failure to have standardized even the classification of the disease. Beyond that, our collective bibliography is rife with case series and by these societies? In turn, the societies must ponder the financial realities of maintaining membership to support their missions, while realizing that an inherent competition exists for funding resources and membership among practicing surgeons.

This is not a new problem, but rather it represents the natural progression of the development of knowledge, technical expertise and need for specialized communication. The evolution of surgical societies reflects these advancements over time (Figure). There was an era in which there was no such thing as a general surgeon; there was only a surgeon who did every and any procedure ranging from leg amputations to craniotomies. Over time, the existing specialties of general, neuro, trauma, orthopedic, urologic, oncologic, cardiothoracic, vascular and plastic surgery have evolved out of advances in knowledge and technology, and the recognition that focusing practice leads to improvement in outcomes. Within our own specialty of general surgery, hernia subspecialization simply reflects the inevitability of progress.

So, back to the future. How do we continue growth in an era when surgeons are retrospective reviews of varying quality, establishing our academic prominence and also singularly unable to answer the questions we need answered the most. To be clear, there is plenty of value to publications at all levels of evidence. Many studies do contribute to our overall knowledge base. Still, it is high time that we address the elephant in the room: There is an urgent need to establish high levels of evidence in hernia surgery in order to best serve our patients. If we are honest about it, for the most part, we have gamely celebrated the metaphorical side dishes while casually overlooking the conspicuous absence of the entrée. Where are the randomized controlled trials (RCTs)?

To better put the discussion in context, we could compare hernia disease to oncologic disease. We would never simply throw our hands in the air and say cancer is too complicated, so we will just settle for what little knowledge we have. Furthermore, we would likely avoid treating surgical oncologic disease based on the hearty recommendations of a social media group. Why are we so quick to be complacent in hernia surgery? While some would argue that hernias are benign disease and do not merit such being asked to do more with less resources and the overall health care system has hit its financial limits? The answers lie with the technological advances in communications in our times. The fundamental concept of a professional society is to foster communication. In an era when the only means of communication was mail or telephone, national meetings were the only way to allow for focused, inclusive discussion and construction of collaborative knowledge in medical specialties. Over time, this evolved into a platform for networking and socializing, and based on the locations of the meetings, recreation as well. Equally importantly, larger societies have come to rely on national meetings as a critical source of revenue. However, the rubric of a large national meeting as the chief means of communication has been fading for some time.

Well before 2020, the availability of information on the internet and the subspecialization in all areas of medicine have led to declining attendance at traditional national meetings. Surveys of younger physicians demonstrate that most would prefer to receive their continuing medical education on their own terms via electronic means, rather than attending conferences. 1 consideration as cancer, our hernia recurrence rates remain unacceptably high and mesh-related complications can deliver a devastating blow to our patients, resulting in additional surgery approximately 5% of the time (JAMA 2016;316[15]:1575-1582). Perhaps “benign” is a poor descriptor. Why are we so reluctant to accept that enlightenment will only come one difficult step at a time?

The relative scarcity of well-designed RCTs in hernia surgery is likely multifactorial. Commonly cited impediments to execution include cost, burden of execution and surgeon time commitment. Despite these obstacles, there are certainly avenues to overcome them, including registry-based trials (J Surg Res 2020;255:428-435). Such studies leverage observational registries by thoughtful design of pragmatic studies, tailored to fit into the standard workflow of participating surgeons and minimizing excessive burdens in terms of time and effort. Additionally, detractors are often critical of RCTs due to their well-known limitations: The response has been to try to repurpose the meetings to attract a broad base of attendees, but in many cases the ability to provide a forum for highly specialized discussion has been lost. The counterresponse has been the rise of subspecialty societies such as the AHS and the AFS.

Enter the coronavirus. Insert whatever metaphor you want about lemons and lemonade or silver linings, the changes in communication generated by the COVID-19 pandemic will echo for years to come. Live internet-based communication is here to stay and it needs to be embraced instead of shunned. Dissemination of information will be delivered virtually at this year’s SAGES Scientific Sessions despite the largest public health disaster in over 100 years, largely through the willingness of the societies’ leadership to embrace an internet-based strategy for communication. This is only the beginning and the opportunities are vast.

Cross-collaboration should be established and encouraged between varying societies. Whereas highly specialized societies such as the AHS and AFS can provide the thought leadership for specific topics, larger societies have the

resources to produce content and the They are narrow in their inclusion criteria and can fail to provide generalizable conclusions, and they are not usually powered to detect low-frequency, catastrophic complications. Often, these limitations are used as justification for rejecting these studies while attempting to establish a moral high ground. Through our impetuous and myopic lens, we have surrendered our academic vigor in favor of comfortable routine. In reality, a well-designed RCT is meant to definitively answer one focused question and to contribute one piece of useful evidence, in this case to our overall understanding of hernia disease. Why are we so reluctant to accept that enlightenment will only come one difficult step at a time, and with a sustained campaign to build on our existing knowledge?

It would be misleading to imply that RCTs are the sole remedy or that most surgeons, regardless of their setting, should (or could) conduct RCTs. Community-based and private practice surgeons often lack the resources (including infrastructure, time and/or desire) to participate in or run these types of trials. Still, observational registries can augment our understanding by providing the granular detail missing from retrospective chart reviews, and additionally by facilitating surveillance of the devices

ability to disseminate knowledge to a broader audience. Moreover, the logistics of meeting in person are moot, and there is a clear appetite for internet-based content that can be stored and viewed on demand, and the ability to generate and share revenue from internet content is well established. The time has come for the various professional societies to truly coexist.

This is not a requiem for the traditional scientific session meeting. There will always be value in genuine face-toface interaction. However, it is possible that the agenda and purpose of an annual meeting may change, hopefully for the better. So, to answer the dilemma facing the practicing general surgeon regarding the various professional societies: 1) yes, subspecialized societies are necessary and reflect the inevitable expansion of knowledge, and 2) if done correctly, keeping up with the information will be easier in the future rather than harder. ■

Reference

1. Acad Med. 2017;92(9):1335-1345. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001624

—Dr. Petersen is an associate professor of surgery at the University of Washington Medical Center, in Seattle.

upon which the field of hernia surgery has come to heavily depend. Arguably, we should reasonably expect that some part of our great responsibility includes registry participation at a minimum, regardless of our practice setting.

We need to begin by acknowledging that we truly know very little about the treatment of hernias. Furthermore, we need to acknowledge the legitimacy of peer-reviewed publication, and to critically appraise the idea that crowdsourcing anecdotes through social media groups can result in meaningful change or reasonable surgical care of patients. Beyond that, we need to hold ourselves accountable for contributing to our profession. This is particularly important given that we benefit (indeed, make our livelihood) from the suffering of others. Finally, our contributions should be meaningful. RCTs can and should be the cornerstone of our understanding of hernia disease, bolstered by registry-based prospective and retrospective studies. Lower evidence studies should assume their rightful place as contributors, not dogma. We can, and should, do better. Our patients expect it. ■

1880 American Surgical Association 1887 American Orthopedic Association 1902 American Urological Association 1912 American College of Surgeons 1947 Society for Vascular Surgery 1957 Society of Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 1917 American Association for Thoracic Surgery 1931 American Society for Plastic Surgeons 1938 Society of University Surgeons 1940 Society of Surgical Oncology 1931 American Association of Neurologic Surgeons 1938 American Association for the Surgery of Trauma 1981 Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 1997 American Hernia Society 2013 American Hernia Society Quality Collaborative 2018 American Foregut Association

1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 2020 Figure. Timeline of founding dates for selected surgical societies.

1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 1880 American Surgical Ass 1887 American Orthopedi 1902 American Urologi 1912 American Colle 1947 Societ 1957 Soci Trac 1 1917 American Ass Surgery 198 1931 American So 1938 Society o 1940 Society 1931 American A Surgeons 1938 American of Traum The Americas Hernia Society is excited to announce that it is shifting to a virtual platform for the 2020 Annual Meeting. Dates: September 25-26, 2020 The meeting promises to be an innovative leap forward in education and networking. Live portions of the meeting will be held Sept. 25-26. In addition, asynchronous sessions will be offered to tailor your meeting experience at your convenience.

Details regarding this exciting format will be forthcoming.

The Role of Robotics in Hernia Repair

By JEREMY WARREN, MD, FACSBy

Perhaps no surgical technology generates as much fervent support or vehement criticism as the robot. While few would dispute the technical advantages of articulating instruments and 3D visualization, many have questioned the widespread adoption without clear evidence supporting its use, particularly in the face of significant initial cost. Adoption of robotic ventral and inguinal hernia repair (rVHR and rIHR) should be evaluated critically in four major areas: • Is it beneficial to the patient? • Are there advantages to the surgeon regarding learning curve or ergonomics? • What is the cost? • How do we train surgeons on new technology and novel techniques?

This brief overview will examine the benefits, limitations and controversies surrounding robotics in hernia repair.

Clinical Outcomes in rIHR

Current literature on rIHR is limited, but indicates comparable risk for complications, recurrence and patient satisfaction to laparoscopic IHR (LIHR). There is a robust body of literature supporting LIHR, demonstrating reduced acute postoperative pain and incidence of chronic postoperative inguinal pain, and similar rates of complications and recurrence to traditional open repair (Hernia 2018;22[1]:1-165). Robotic IHR emulates LIHR with some minor variations in technique, notably a transition to predominantly transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair from a predominantly totally extraperitoneal (TEP) approach for LIHR. Additionally, few surgeons performing rIHR use tack or staple fixation and use sutures to close the peritoneal flap, which may reduce postoperative pain.

Early results of a multicenter prospective trial of more than 500 patients comparing open IHR, LIHR and rIHR favor LIHR and rIHR over open IHR, with similar outcomes between the two. Fewer patients reported taking opioid analgesia in the rIHR group compared with LIHR, although the mean number of pills was no different (Hernia 2020;362:1561-1565). In the RIVAL trial, a prospective randomized multicenter trial of laparoscopic versus robotic TAPP IHR, no difference was seen in complications, readmissions, pain, physical activity or cosmesis (JAMA Surg 2020;155[5]:380-387). The excellent clinical outcomes of LIHR will make it difficult to prove the superiority of rIHR, and these should be considered equivalent at this point.

Clinical Outcomes of rVHR

There are several variations of rVHR that must be considered.

Robotic Intraperitoneal Only of Mesh

Robotic IPOM is a modification of standard laparoscopic VHR, utilizing a transabdominal approach to bridge or reinforce the hernia with intraperitoneal mesh. This technique is the simplest and the most commonly performed rVHR, and has the distinct advantage of reliable closure of the hernia defect. Reinforcement of a closed defect rather than bridging has mechanical advantages, particularly for larger defects, that reduce the risk for mesh eventration and recurrence, and may decrease the rate of seroma (Hernia 2017;20:893-895; Surg Endosc 2019;33[10]:3069-3139). Additionally, most surgeons performing rIPOM fixate the mesh with intracorporeal sutures rather than tacks or transfascial sutures. Advocates report less postoperative pain with this approach, although this has not been clearly demonstrated in the literature.

Robotic TAPP Repair

While relatively uncommon, complications of intraperitoneal mesh can be devastating. Further, intraperitoneal mesh may complicate subsequent abdominal operations, which are required in as many as 25% of patients after hernia repair (J Am Coll Surg 2011;212[4]:496- 502). This has led many to prefer extraperitoneal mesh placement. Robotic TAPP utilizes the preperitoneal space for mesh reinforcement, mitigating these risks associated with IPOM. Reports of rTAPP compare favorably to LVHR and rIPOM (Hernia 2020 May 5. Epub ahead of print]; Hernia 2019;23[5]:957- 967). There is little risk for damage to the abdominal wall with this procedure, and if the peritoneal flap integrity cannot be maintained, conversion to IPOM is straightforward.

Robotic Retromuscular Repair

Probably the most innovative application of rVHR is the reconstruction of the abdominal wall. Widely considered the gold standard for open repair, retromuscular (RM) VHR provides rectus abdominis myofascial release to allow defect closure and creates an extraperitoneal plane for mesh placement. The addition of a transversus abdominis release (TAR) further mobilizes the abdominal wall for closure of larger hernia defects and wider mesh reinforcement.

A transabdominal approach can be used to access the RM space, most often with the addition of TAR. This approach reduces the length of stay compared with open and laparoscopic IPOM, and may reduce surgical site infections (Ann Surg 2018;267:210-217; Surg Endosc 2017;31[1]:324-332). However, its application should be limited to patients with larger defects that would require TAR, if performed open, to avoid unnecessary myofascial release.

Recently, the extended-view totally extraperitoneal (eTEP) repair has garnered significant attention, and is our preferred approach for most rVHR. This technique allows a more tailored approach by first releasing the rectus sheath alone, with additional rTAR only if needed. eTEP has allowed us to convert from traditional open RM VHR or LVHR with an inpatient stay of one to three days to an outpatient procedure in most cases, a finding reported by other authors as well (Hernia 2018;22[5]:837- 847; Surg Endosc 2020;23:957-1007).

Surgeon Advantages of rIHR

Proponents often cite ergonomic benefits of the robot. Musculoskeletal injury is a known hazard of laparoscopic surgery (J Am Coll Surg 2010;210[3]:306-313). The ability to sit down and adjust the robotic console components is appealing. However, there remains a risk for injury. In the RIVAL trial, surgeon ergonomics were not significantly different between LIHR and rIHR, both demonstrating a high risk for musculoskeletal injury (JAMA Surg 2020;155[5]:380-387). A study of ergonomics in robotic gynecologic surgery reported similar findings (J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013;20[5]:648 -655). Greater awareness and education are needed to mitigate this risk and take advantage of the potential ergonomic benefits of the robotic platform.

The learning curve of complex laparoscopy is significant, requiring up to 200 laparoscopic IHRs to reach proficiency, which contributes to its relatively limited adoption (Hernia 2018;22[1]:1- 165). The robot may shorten the learning curve of minimally invasive IHR (Surg Endosc 2018;32[12]:4850-4859). Robotic simulation very closely approximates the reality of operating on the system. Additionally, through novel training and mentorship paradigms, most notably the International Hernia Collaboration (IHC) and Robotic Surgery Collaboration (RSC), there is a wealth of videobased technical instruction and almost real-time peer review available to new surgeons adopting rIHR or rVHR. It remains to be seen whether this will lead more surgeons to transition from open to minimally invasive IHR.

Cost of Robotic Hernia Repair

Disparate data exist on the costs associated with robotic compared with open or laparoscopic repairs (JAMA Surg 2020;155[5]:380-387; J Robot Surg 2016;10[3]:239-244). The initial expense of the robot and associated maintenance contracts are significant. Patient charges are likely higher after robotic repair (J Am Coll Surg 2020;231[1]:61-72). However, these results are not necessarily generalizable. Direct hospital costs can vary depending on vendor contracts and individual surgeon supply utilization. Indirect costs vary according to billing structure and payor contracts. Potential cost savings of shorter length of stay should offset the cost for rVHR. Finally, quantifying the potential benefit of earlier return to work is challenging. At this point, robotic surgery cannot be judged solely on the basis of cost.

Training

Residency or fellowship programs are the best model for training in novel surgical techniques, but this excludes practicing surgeons. For these surgeons, training is done primarily through industry-sponsored programs, postgraduate courses in conjunction with society meetings, live proctoring, selfguided learning, and virtual mentorship via groups such as the IHC or RSC. While this is adequate for many surgeons, it may not be for all, and there is no way to accurately assess proficiency of the learner. There are legitimate concerns from high-volume hernia referral centers, including our own, that some adopting these techniques may not appreciate the subtleties of the RM and TAR anatomy, resulting in disruption of the semilunar line and complex lateral hernias (Hernia 2020;24[2]:333-340). It is imperative that we continue to explore innovative options for mentoring surgeons in novel techniques.

Interest in robotic hernia repair will undoubtedly continue, and adoption almost certainly will increase. While there will continue to be critics of robotic hernia repair, the ideal application of this innovative and enabling technology will become clearer as data emerge from ongoing clinical trials. ■

—Dr. Warren is an associate professor of surgery at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine in Greenville.