7 minute read

UP, UP AND AWAY

As a city with no shortage of them, we are still captivated by the uplifting sight of a ballooned-filled sky. Catherine Pittinvestigates the history of hot air ballooning in Bath, taking us back to the very beginning...

Soaring gracefully above the rooftops, the countryside stretching for what appears like forever, what thrill and what terror the first balloonists must have felt when first ascending into the ‘great unknown’?

Advertisement

The first unmanned demonstration of ballooning was in Portugal in 1709, but it is the Montgolfier brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etienne, who are remembered as the innovators. The brothers launch ed their first b alloon in Paris in September 1783, but it was two months later on 21 November 1783, in front of a vast crowd, that a Montgolfier-built balloon first ascended with pilots. Jean-François Pilatre de Rozier and François Laurent le Vieux d'Arlandes became the first humans to travel untethered in a hot air balloon.

In the UK, the first manned balloon flight was by Scottish aeronaut James Tytler in August 1784, but this achievement was q uickly overshadowed by the flamboyant Vincenzo Lunardi’s success in London a month later. Lunardi’s ascent was well promoted and witnessed by thousands. The craze for ballooning had begun.

Bath and flight were no strangers. According to the legend of King Bladud – the alleged founder of the city – it was he who flew from Bath to London wearing a pair of wings that he had built himself. However, t he first attempts at ballooning in Bath began a few months after de Rozier and Laurent’s success in Paris.

At midday on 10 January 1784, Caleb Hiller-Parry, local doctor and the son of Arctic explorer Admiral Sir Edward Parry, launched a small hydrogen-filled balloon from Crescent Park – now Royal Victoria Park. A few hours later, James Dinwiddie launched his own balloon from Mrs Scarce’s Riding School on Julian Road – or The Museum of Bath at Work as we know it today.

H illier-Parry’s attempt was to be a one-off experiment, but Dinwiddie persevered and 10 days later he launched another unmanned balloon from Bath. On descent into Dorset, his balloon caused a sensation. Landing in a field of cows, local farmers attacked the ‘strange creature’, thinking it was a monster.

The first manned balloon flight in the city w as made in Sydney Gardens on 8 September 1802, piloted by the Frenchman André Jacques Garnerin (1769–1825). In his memoirs, Garnerin recalled the throngs of people in the garden, streets, and even clambering onto rooftops. It was described in a local paper as ‘the most sublime spectacle ever exhibited here’.

Hot air balloons fill the skies of Bath

Aeronauts without deep pockets or a wealthy patron had to rely on the good will o f the public to fund their ballooning. Before Dinwiddie’s launch in 1784, he had exhibited the balloon in the Lower Assembly Rooms charging two shillings per person. The aeronaut Joseph Deeter’s balloon cost him an estimated £200 – £18,000 today – and en route to the launch in Bristol he tried to cover its costs through exhibitions. At the Upper Assembly Rooms, Deeter charged one shilling admittance.

I t would take several hours to inflate the balloon’s envelope and crowds would gather to witness this as part of the ‘show’. While

this was happening, the pilot would talk to the enthralled public. Ticketed green spaces such as Sydney Gardens were perfect for launches as both park owner and aviator benefitted from the gate fees. In addition, Sydney Gardens had great facilities – food, drink, mu sic and amusements – which would d raw in a crowd.

The cost of witnessing these spectacles varied. Garnerin’s 1802 ascent was advertised at five shillings with another five shillings for seating on a specially built viewing platform. A few weeks later, Garnerin launched a Night Balloon Gala at a cost of three shillings per ticket that included illuminations, a concert, and a balloon that “would rise majesti cally (like)…a luminous m eteor”. By the mid-19th century ticket prices had reduced. An ascent by Mr Green in Sydney Gardens in July 1846 was advertised for onee shilling per person.

At the height of the obsession with ballooning, ‘Balloon Coaches’ ran between London, Bristol and Bath bringing in enthusiastic spectators. Alongside the launches came songs, books, and souvenirs. Trinkets such as snuff boxes we re adorned w ith ballooning images, and even clothing was embellished with aeronautical prints.

ABOVE: The evolution of hot air balloons over a century, starting with the Montgolfier brothers’ original design in 1783

Not all launches were a success. In October 1823, George Graham twice failed to inflate his balloon in Sydney Gardens, forcing him to postpone. It was discovered that the gas pipes opposite in Pulteney Street were clogged with dirt. An additional site was sought and found on Upper Bristol Road in an empty field next to and owned by the B ath Gas Wo rks Company.

It also wasn’t uncommon for pilots’ families to accompany them on their escapades, leading to successful generations of aeronauts. One famous female aeronaut was Margaret Graham (c.1804–1880). She was born and lived in Walcot, Bath and

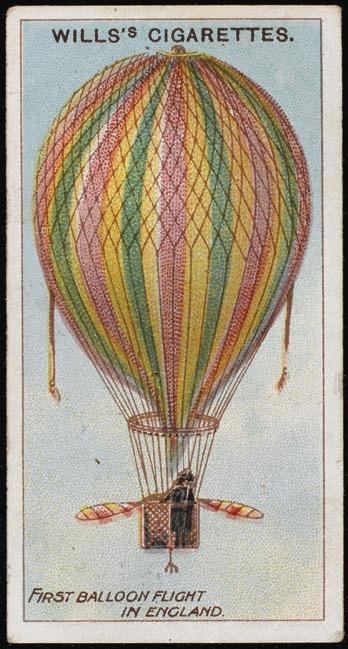

Below: A cigarette box after Vincenzo Lunardi ‘s first balloon ascent in London

became the first British woman to make a solo balloon flight on 28 June 1826. She was also the first woman to make a night flight in 1850. Her husban d was the a eronaut George Graham and their daughters later followed in their parents’ footsteps and took to the skies.

Another renowned Bath balloonist was Patrick Young Alexander (1867–1943), who moved to the city in the 1890s. His family were flying enthusiasts and his father helped found the Aeronautical Society in 1866. Initially, Alexander lived in Combe Down and built a small factory to construct hi s b alloons on Midford Road. This building still stands today and is now used to house the Cross Manufacturing Company’s museum. In 1900, Alexander moved to The Mount in Batheaston where he built a workshop in his garden and installed a direct gas supply.

In 1902, Alexander re-created Garnerin’s 1802 balloon launch in Sydney Gardens, joined by some of his aviator friends, including the American Samuel Cody , C harles Rolls (of Rolls Royce) and Major Frank Trollope (of the Royal Engineers Balloon Factory at Aldershot, Hampshire).

Some Bath residents considered ballooning to be a nuisance rather than a thrill. It wasn’t unknown for unmanned balloons to occasionally drop onto rooftops and start fires. In a newspaper report in July 1913, Bathford resident, Mr W. T. Humphries complained of significant financial lo sses a fter his pony became spooked by a lowflying hot air balloon and ran off, dragging and destroying the cart it was attached to, and killing the poultry that were caged on the cart.

In the experimental days of ballooning, aeronauts were considered daredevils. Manned balloons were launched in all weathers, some reaching speeds upwards of 90mph, which in an era before motorised vehicles must have seemed equally e xhilarating and terrifying. Some aeronauts even tried parachuting from their balloons and although precautions were taken, tragedies did occur.

One such catastrophe was that of Saladin, a hot-air balloon launched from Bath in December 1881. It carried Captain James Templer, Walter Powell – MP for Marlborough in Wiltshire – and Lieutenant James Agg-Gardener. The trio found themselves heading towards the Devon coast, b ut realised it would be too dark to attempt a Channel crossing. Templer jumped out by the cliffs to secure the balloon, but couldn’t find an anchor. Agg-Gardener jumped from the basket to assist but broke his leg upon landing. The struggling Templer still had grasp of the valve line and shouted to Powell, still in the basket, to slide down it. However a gust of wind caught the balloon and Te mpler lost his grip and the balloon with Powell still on-board headed out to sea. Despite searches and reported sightings, only Powell’s hat was recovered from the waters. It wasn’t until 1888 that the remains of Saladin were discovered, at the foot of the Pyrenees. No human remains were ever located.

The passion for air balloons began to wane by the early 20th century with the success and subsequent dev elopment of a eroplanes as a form of transport. Balloons continued to be used for meteorological purposes, and during the First World War for military observations. The era of modern ballooning began in the 1960s. New recordbreaking attempts were made, including by local aeronaut Sir David HemplemanAdams.

By the 1970s, hot air balloons began to grace Bath’s skies once more. Today recreational trips oft en launch from Royal Vi ctoria Park, where you can feel the same thrill, but hopefully not the terror, that the 18th and 19th century pioneers once did.

Human flight still continues to captivate us – there is a compulsion to stop and look to the sky when we hear a balloon burner or see the shadow of a balloon silently gliding overhead. n